User login

A Faux Fungal Affliction

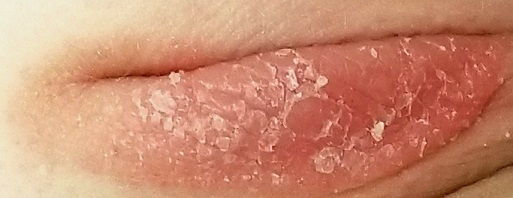

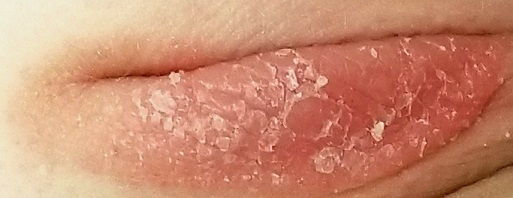

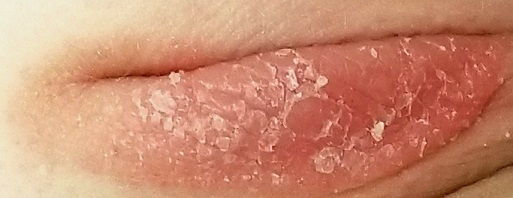

A 45-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for a “fungal infection” that has failed to respond to the following treatments: topical clotrimazole cream, topical miconazole cream, a 30-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), and a 2-month course of oral griseofulvin (unknown dose). The lesions are completely asymptomatic but quite worrisome to the patient since they manifested 6 months ago.

She has consulted at least 6 different providers—none of whom was a dermatologist but all of whom were certain of the diagnosis and thus felt no need to refer the patient. However, the passage of time and trail of ineffective treatments finally prompts the (albeit reluctant) decision to send the patient to dermatology.

On questioning, she denies any serious health problems, such as diabetes or immunosuppression. She has had no contact with any animals or children.

EXAMINATION

The lesions in question total 6; all are uniformly purplish brown, round, and macular, and they range from 5 mm to more than 3 cm. Most are located on the bilateral popliteal areas. The lesions have sharp, well-defined margins. Several have faintly raised papular margins that give the centers a slightly concave appearance.

Palpation reveals the complete absence of any surface disturbance, such as scaling or erosion. Thus, no KOH prep can be performed to check for fungal elements. Instead, a shave biopsy is performed, the results of which show a sawtooth-patterned lymphocytic infiltrate obliterating the normally smooth undulating dermoepidermal junction.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case effectively demonstrates the principle that, when confronted with round or annular lesions, some providers will rely on the diagnosis of “fungal” even when evidence (eg, failed treatment attempts) suggests otherwise. What that nonresponse should do is signal the need for an expanded differential—that is, a consideration of other diagnostic possibilities. This is a bedrock principle in every medical specialty, not just in dermatology.

In this case, the biopsy results clearly pointed to the correct diagnosis of lichen planus (LP), a common dermatosis well known to present in annular morphology. LP is a benign process, albeit one that is occasionally quite bothersome (eg, itching) and, rarely, widespread. LP’s more typical distribution is on volar wrists, in the sacral areas, and occasionally on genitals, so the inability to make a visual diagnosis in this case is forgivable.

Although LP’s etiology is unfortunately unknown, what is known is how to treat it: with topical steroids when necessary or “tincture of time,” as in this patient’s asymptomatic case. LP typically resolves on its own, and it has no worrisome import or connections to more serious disease.

But as always, the first step to correct diagnosis is to consider letting go of the old diagnosis—fungal infection—which was clearly incorrect given the lack of response to numerous antifungals. The second step is to consider other possibilities, which would include lichen planus, psoriasis, granuloma annulare, tinea versicolor, and necrobiosis. The third step is to perform a biopsy, which would establish the correct diagnosis with certainty and in turn, dictate correct treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- There is an extensive differential for round or annular skin lesions that includes many nonfungal causes.

- When antifungals fail to help, consider other diagnostic possibilities.

- Perform a biopsy when a visual diagnosis is not possible.

- Lichen planus (LP) is a common benign inflammatory skin condition that can present with annular lesions.

A 45-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for a “fungal infection” that has failed to respond to the following treatments: topical clotrimazole cream, topical miconazole cream, a 30-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), and a 2-month course of oral griseofulvin (unknown dose). The lesions are completely asymptomatic but quite worrisome to the patient since they manifested 6 months ago.

She has consulted at least 6 different providers—none of whom was a dermatologist but all of whom were certain of the diagnosis and thus felt no need to refer the patient. However, the passage of time and trail of ineffective treatments finally prompts the (albeit reluctant) decision to send the patient to dermatology.

On questioning, she denies any serious health problems, such as diabetes or immunosuppression. She has had no contact with any animals or children.

EXAMINATION

The lesions in question total 6; all are uniformly purplish brown, round, and macular, and they range from 5 mm to more than 3 cm. Most are located on the bilateral popliteal areas. The lesions have sharp, well-defined margins. Several have faintly raised papular margins that give the centers a slightly concave appearance.

Palpation reveals the complete absence of any surface disturbance, such as scaling or erosion. Thus, no KOH prep can be performed to check for fungal elements. Instead, a shave biopsy is performed, the results of which show a sawtooth-patterned lymphocytic infiltrate obliterating the normally smooth undulating dermoepidermal junction.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case effectively demonstrates the principle that, when confronted with round or annular lesions, some providers will rely on the diagnosis of “fungal” even when evidence (eg, failed treatment attempts) suggests otherwise. What that nonresponse should do is signal the need for an expanded differential—that is, a consideration of other diagnostic possibilities. This is a bedrock principle in every medical specialty, not just in dermatology.

In this case, the biopsy results clearly pointed to the correct diagnosis of lichen planus (LP), a common dermatosis well known to present in annular morphology. LP is a benign process, albeit one that is occasionally quite bothersome (eg, itching) and, rarely, widespread. LP’s more typical distribution is on volar wrists, in the sacral areas, and occasionally on genitals, so the inability to make a visual diagnosis in this case is forgivable.

Although LP’s etiology is unfortunately unknown, what is known is how to treat it: with topical steroids when necessary or “tincture of time,” as in this patient’s asymptomatic case. LP typically resolves on its own, and it has no worrisome import or connections to more serious disease.

But as always, the first step to correct diagnosis is to consider letting go of the old diagnosis—fungal infection—which was clearly incorrect given the lack of response to numerous antifungals. The second step is to consider other possibilities, which would include lichen planus, psoriasis, granuloma annulare, tinea versicolor, and necrobiosis. The third step is to perform a biopsy, which would establish the correct diagnosis with certainty and in turn, dictate correct treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- There is an extensive differential for round or annular skin lesions that includes many nonfungal causes.

- When antifungals fail to help, consider other diagnostic possibilities.

- Perform a biopsy when a visual diagnosis is not possible.

- Lichen planus (LP) is a common benign inflammatory skin condition that can present with annular lesions.

A 45-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for a “fungal infection” that has failed to respond to the following treatments: topical clotrimazole cream, topical miconazole cream, a 30-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), and a 2-month course of oral griseofulvin (unknown dose). The lesions are completely asymptomatic but quite worrisome to the patient since they manifested 6 months ago.

She has consulted at least 6 different providers—none of whom was a dermatologist but all of whom were certain of the diagnosis and thus felt no need to refer the patient. However, the passage of time and trail of ineffective treatments finally prompts the (albeit reluctant) decision to send the patient to dermatology.

On questioning, she denies any serious health problems, such as diabetes or immunosuppression. She has had no contact with any animals or children.

EXAMINATION

The lesions in question total 6; all are uniformly purplish brown, round, and macular, and they range from 5 mm to more than 3 cm. Most are located on the bilateral popliteal areas. The lesions have sharp, well-defined margins. Several have faintly raised papular margins that give the centers a slightly concave appearance.

Palpation reveals the complete absence of any surface disturbance, such as scaling or erosion. Thus, no KOH prep can be performed to check for fungal elements. Instead, a shave biopsy is performed, the results of which show a sawtooth-patterned lymphocytic infiltrate obliterating the normally smooth undulating dermoepidermal junction.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case effectively demonstrates the principle that, when confronted with round or annular lesions, some providers will rely on the diagnosis of “fungal” even when evidence (eg, failed treatment attempts) suggests otherwise. What that nonresponse should do is signal the need for an expanded differential—that is, a consideration of other diagnostic possibilities. This is a bedrock principle in every medical specialty, not just in dermatology.

In this case, the biopsy results clearly pointed to the correct diagnosis of lichen planus (LP), a common dermatosis well known to present in annular morphology. LP is a benign process, albeit one that is occasionally quite bothersome (eg, itching) and, rarely, widespread. LP’s more typical distribution is on volar wrists, in the sacral areas, and occasionally on genitals, so the inability to make a visual diagnosis in this case is forgivable.

Although LP’s etiology is unfortunately unknown, what is known is how to treat it: with topical steroids when necessary or “tincture of time,” as in this patient’s asymptomatic case. LP typically resolves on its own, and it has no worrisome import or connections to more serious disease.

But as always, the first step to correct diagnosis is to consider letting go of the old diagnosis—fungal infection—which was clearly incorrect given the lack of response to numerous antifungals. The second step is to consider other possibilities, which would include lichen planus, psoriasis, granuloma annulare, tinea versicolor, and necrobiosis. The third step is to perform a biopsy, which would establish the correct diagnosis with certainty and in turn, dictate correct treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- There is an extensive differential for round or annular skin lesions that includes many nonfungal causes.

- When antifungals fail to help, consider other diagnostic possibilities.

- Perform a biopsy when a visual diagnosis is not possible.

- Lichen planus (LP) is a common benign inflammatory skin condition that can present with annular lesions.

A Lesion Hits Its Growth Spurt

When she was 3 years old, a lesion appeared on this child’s face. It was small and caused little to no concern for several years. The child is now 9, and about a year ago, the lesion began to enlarge, ultimately reaching its present size.

First thought to be a pimple, the lesion was later deemed to be “cystic in nature” by another provider. By that point, however, the lesion was quite prominent—to the extent that it intrudes into the patient’s visual field. Perhaps more significantly for someone her age, it has prompted looks and comments that make her uncomfortable.

Fortunately, the lesion causes no pain or physical discomfort, and no other lesions have manifested. The child’s health is generally excellent.

EXAMINATION

A firm nodule, measuring 1.0 by 0.8 cm, is located on the patient’s left upper nasal sidewall. It stands out on an otherwise pristine face free of other blemishes. The lesion is predominantly red, with faint epidermal disturbance in the center. No punctum is appreciated. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with just a hint of fluctuance but no tenderness or increased warmth.

Excision is clearly indicated; however, the wait for an appointment with a plastic surgeon is currently weeks to months. So an attempt is made to reduce the prominence of the lesion through incision and drainage, which also offers an opportunity to visualize its contents and possibly confirm a diagnosis. The lesion is opened with a #11 blade, and copious amounts of whitish, grainy material is digitally extruded.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The contents are consistent with those of a somewhat unusual lesion, commonly called pilomatricoma. It is also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe and pilomatrixoma.

This type of cyst is derived from the hair matrix and is commonly seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults. This patient’s lesion was atypical in its prominence and erythema, at odds with the firm bluish intradermal papule or nodule usually seen in these cases. But the unique contents established the diagnosis with considerable certainty.

All that remained was the excision—which, given the patient’s age and the cosmetic concerns, would require above-average surgical skills. Once removed, the sample will be sent for pathologic examination, which should show anucleate squamous cells (“ghost cells”), benign viable squamous cells with a lining consisting of basaloid cells. Calcifications with foreign body giant cells account for the pathognomic white flecks seen in the extruded material.

Pilomatricoma’s cause is debatable, but it appears to involve increased levels of beta catenin caused by mutations of the APC gene. This effectively inhibits apoptosis, leading to focal increases in cell growth.

The differential for this type of lesion includes simple acne cyst (unlikely in such a young child), carbuncle (which would have been quite painful and full of pus), or even squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Pilomatricomas are benign cysts usually seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults.

- The typical pilomatricoma (sometimes called calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an intradermal papule or nodule, often displaying a faintly bluish color, that is relatively firm on palpation.

- The contents of a pilomatricoma usually consist of whitish curds or flecks of material that represent calcified tissue mixed with foreign body giant cells.

- Pilomatricoma has little or no malignant potential but is often cosmetically significant.

When she was 3 years old, a lesion appeared on this child’s face. It was small and caused little to no concern for several years. The child is now 9, and about a year ago, the lesion began to enlarge, ultimately reaching its present size.

First thought to be a pimple, the lesion was later deemed to be “cystic in nature” by another provider. By that point, however, the lesion was quite prominent—to the extent that it intrudes into the patient’s visual field. Perhaps more significantly for someone her age, it has prompted looks and comments that make her uncomfortable.

Fortunately, the lesion causes no pain or physical discomfort, and no other lesions have manifested. The child’s health is generally excellent.

EXAMINATION

A firm nodule, measuring 1.0 by 0.8 cm, is located on the patient’s left upper nasal sidewall. It stands out on an otherwise pristine face free of other blemishes. The lesion is predominantly red, with faint epidermal disturbance in the center. No punctum is appreciated. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with just a hint of fluctuance but no tenderness or increased warmth.

Excision is clearly indicated; however, the wait for an appointment with a plastic surgeon is currently weeks to months. So an attempt is made to reduce the prominence of the lesion through incision and drainage, which also offers an opportunity to visualize its contents and possibly confirm a diagnosis. The lesion is opened with a #11 blade, and copious amounts of whitish, grainy material is digitally extruded.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The contents are consistent with those of a somewhat unusual lesion, commonly called pilomatricoma. It is also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe and pilomatrixoma.

This type of cyst is derived from the hair matrix and is commonly seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults. This patient’s lesion was atypical in its prominence and erythema, at odds with the firm bluish intradermal papule or nodule usually seen in these cases. But the unique contents established the diagnosis with considerable certainty.

All that remained was the excision—which, given the patient’s age and the cosmetic concerns, would require above-average surgical skills. Once removed, the sample will be sent for pathologic examination, which should show anucleate squamous cells (“ghost cells”), benign viable squamous cells with a lining consisting of basaloid cells. Calcifications with foreign body giant cells account for the pathognomic white flecks seen in the extruded material.

Pilomatricoma’s cause is debatable, but it appears to involve increased levels of beta catenin caused by mutations of the APC gene. This effectively inhibits apoptosis, leading to focal increases in cell growth.

The differential for this type of lesion includes simple acne cyst (unlikely in such a young child), carbuncle (which would have been quite painful and full of pus), or even squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Pilomatricomas are benign cysts usually seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults.

- The typical pilomatricoma (sometimes called calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an intradermal papule or nodule, often displaying a faintly bluish color, that is relatively firm on palpation.

- The contents of a pilomatricoma usually consist of whitish curds or flecks of material that represent calcified tissue mixed with foreign body giant cells.

- Pilomatricoma has little or no malignant potential but is often cosmetically significant.

When she was 3 years old, a lesion appeared on this child’s face. It was small and caused little to no concern for several years. The child is now 9, and about a year ago, the lesion began to enlarge, ultimately reaching its present size.

First thought to be a pimple, the lesion was later deemed to be “cystic in nature” by another provider. By that point, however, the lesion was quite prominent—to the extent that it intrudes into the patient’s visual field. Perhaps more significantly for someone her age, it has prompted looks and comments that make her uncomfortable.

Fortunately, the lesion causes no pain or physical discomfort, and no other lesions have manifested. The child’s health is generally excellent.

EXAMINATION

A firm nodule, measuring 1.0 by 0.8 cm, is located on the patient’s left upper nasal sidewall. It stands out on an otherwise pristine face free of other blemishes. The lesion is predominantly red, with faint epidermal disturbance in the center. No punctum is appreciated. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with just a hint of fluctuance but no tenderness or increased warmth.

Excision is clearly indicated; however, the wait for an appointment with a plastic surgeon is currently weeks to months. So an attempt is made to reduce the prominence of the lesion through incision and drainage, which also offers an opportunity to visualize its contents and possibly confirm a diagnosis. The lesion is opened with a #11 blade, and copious amounts of whitish, grainy material is digitally extruded.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The contents are consistent with those of a somewhat unusual lesion, commonly called pilomatricoma. It is also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe and pilomatrixoma.

This type of cyst is derived from the hair matrix and is commonly seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults. This patient’s lesion was atypical in its prominence and erythema, at odds with the firm bluish intradermal papule or nodule usually seen in these cases. But the unique contents established the diagnosis with considerable certainty.

All that remained was the excision—which, given the patient’s age and the cosmetic concerns, would require above-average surgical skills. Once removed, the sample will be sent for pathologic examination, which should show anucleate squamous cells (“ghost cells”), benign viable squamous cells with a lining consisting of basaloid cells. Calcifications with foreign body giant cells account for the pathognomic white flecks seen in the extruded material.

Pilomatricoma’s cause is debatable, but it appears to involve increased levels of beta catenin caused by mutations of the APC gene. This effectively inhibits apoptosis, leading to focal increases in cell growth.

The differential for this type of lesion includes simple acne cyst (unlikely in such a young child), carbuncle (which would have been quite painful and full of pus), or even squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Pilomatricomas are benign cysts usually seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults.

- The typical pilomatricoma (sometimes called calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an intradermal papule or nodule, often displaying a faintly bluish color, that is relatively firm on palpation.

- The contents of a pilomatricoma usually consist of whitish curds or flecks of material that represent calcified tissue mixed with foreign body giant cells.

- Pilomatricoma has little or no malignant potential but is often cosmetically significant.

Biopsy? What Biopsy?

This 80-year-old man has been complaining to health care providers about the asymptomatic lesion on his right forearm for at least 5 years—“maybe more,” he says. During that time, he has been given a variety of diagnoses, mostly “infection” of some sort, along with prescriptions for oral antibiotics (cephalexin, trimethoprim/sulfa), topical antibiotics (mupirocin, triple-antibiotic cream), and germicidal washes (povidone and others). None of these treatment attempts has achieved results.

Prior to now, there has been no referral to dermatology, nor has any provider suggested biopsy of the lesion. The patient has a history of skin cancer (basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas) on his face, back, and arms. These followed a lifetime of sun exposure due to his work in construction and roofing.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is located on the dorsal aspect of his mid right forearm. Measuring almost 4 cm in aggregate, the lesion is composed of 2 adjacent bright red half-moon friable nodules in a circular configuration. There is almost no erythema or edema in or around the lesion, which is neither warm nor tender to touch.

There are no palpable nodes in the adjacent epitrochlear or axillary nodal locations.

The surrounding skin of this arm, as well as that of the opposite arm, is quite thin, discolored, and scaly and is covered with stellate scars. Examination of all other sun-exposed areas reveals similar changes but no other notable lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be obvious to most readers that a biopsy is in order, given the likelihood that this lesion is either a basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma—an impression bolstered by the contextual findings of advanced sun damage and the history of skin cancer. And yet, this patient finds himself with a nonhealing friable lesion that is at least 5 years old.

Repeated misdiagnosis as infection is actually a common occurrence. One suspects that at least some of the providers making this mistake followed the patient’s lead: Many affected patients assume such lesions represent infection and therefore demand treatment appropriate for that diagnosis.

As a rule, however, bacterial infections don’t last years, especially in the absence of pain and swelling. Yes, there are nonbacterial infections (eg, those caused by acid-fast bacilli) that can be just as, if not more, indolent, but they too are apt to be painful and swollen.

Biopsy, the obvious missing step in this entire saga, would rule out any of these odd things (including melanoma, which has been known to present in this atypical morphologic manner). Other items in the differential include pyogenic granuloma and metastatic cancer (eg, breast, colon, lung).

In this case, biopsy confirmed the lesion was (as expected) a basal cell carcinoma. The lesion was excised in 2 stages over a 2.5-month period. And the patient was reminded that he will remain at extremely high risk for additional sun-caused skin cancers for the rest of his life.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Nonhealing lesions should be assumed to be skin cancer until proven otherwise, especially in sun-damaged individuals.

- Correct treatment is dictated by correct diagnosis; in this case, a biopsy was clearly indicated.

- Besides the more common cancers (eg, basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma), there were numerous other items in the differential, including melanoma and even metastatic cancer.

- Only rarely do skin infections smolder for years without pain or surrounding erythema.

This 80-year-old man has been complaining to health care providers about the asymptomatic lesion on his right forearm for at least 5 years—“maybe more,” he says. During that time, he has been given a variety of diagnoses, mostly “infection” of some sort, along with prescriptions for oral antibiotics (cephalexin, trimethoprim/sulfa), topical antibiotics (mupirocin, triple-antibiotic cream), and germicidal washes (povidone and others). None of these treatment attempts has achieved results.

Prior to now, there has been no referral to dermatology, nor has any provider suggested biopsy of the lesion. The patient has a history of skin cancer (basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas) on his face, back, and arms. These followed a lifetime of sun exposure due to his work in construction and roofing.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is located on the dorsal aspect of his mid right forearm. Measuring almost 4 cm in aggregate, the lesion is composed of 2 adjacent bright red half-moon friable nodules in a circular configuration. There is almost no erythema or edema in or around the lesion, which is neither warm nor tender to touch.

There are no palpable nodes in the adjacent epitrochlear or axillary nodal locations.

The surrounding skin of this arm, as well as that of the opposite arm, is quite thin, discolored, and scaly and is covered with stellate scars. Examination of all other sun-exposed areas reveals similar changes but no other notable lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be obvious to most readers that a biopsy is in order, given the likelihood that this lesion is either a basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma—an impression bolstered by the contextual findings of advanced sun damage and the history of skin cancer. And yet, this patient finds himself with a nonhealing friable lesion that is at least 5 years old.

Repeated misdiagnosis as infection is actually a common occurrence. One suspects that at least some of the providers making this mistake followed the patient’s lead: Many affected patients assume such lesions represent infection and therefore demand treatment appropriate for that diagnosis.

As a rule, however, bacterial infections don’t last years, especially in the absence of pain and swelling. Yes, there are nonbacterial infections (eg, those caused by acid-fast bacilli) that can be just as, if not more, indolent, but they too are apt to be painful and swollen.

Biopsy, the obvious missing step in this entire saga, would rule out any of these odd things (including melanoma, which has been known to present in this atypical morphologic manner). Other items in the differential include pyogenic granuloma and metastatic cancer (eg, breast, colon, lung).

In this case, biopsy confirmed the lesion was (as expected) a basal cell carcinoma. The lesion was excised in 2 stages over a 2.5-month period. And the patient was reminded that he will remain at extremely high risk for additional sun-caused skin cancers for the rest of his life.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Nonhealing lesions should be assumed to be skin cancer until proven otherwise, especially in sun-damaged individuals.

- Correct treatment is dictated by correct diagnosis; in this case, a biopsy was clearly indicated.

- Besides the more common cancers (eg, basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma), there were numerous other items in the differential, including melanoma and even metastatic cancer.

- Only rarely do skin infections smolder for years without pain or surrounding erythema.

This 80-year-old man has been complaining to health care providers about the asymptomatic lesion on his right forearm for at least 5 years—“maybe more,” he says. During that time, he has been given a variety of diagnoses, mostly “infection” of some sort, along with prescriptions for oral antibiotics (cephalexin, trimethoprim/sulfa), topical antibiotics (mupirocin, triple-antibiotic cream), and germicidal washes (povidone and others). None of these treatment attempts has achieved results.

Prior to now, there has been no referral to dermatology, nor has any provider suggested biopsy of the lesion. The patient has a history of skin cancer (basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas) on his face, back, and arms. These followed a lifetime of sun exposure due to his work in construction and roofing.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is located on the dorsal aspect of his mid right forearm. Measuring almost 4 cm in aggregate, the lesion is composed of 2 adjacent bright red half-moon friable nodules in a circular configuration. There is almost no erythema or edema in or around the lesion, which is neither warm nor tender to touch.

There are no palpable nodes in the adjacent epitrochlear or axillary nodal locations.

The surrounding skin of this arm, as well as that of the opposite arm, is quite thin, discolored, and scaly and is covered with stellate scars. Examination of all other sun-exposed areas reveals similar changes but no other notable lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be obvious to most readers that a biopsy is in order, given the likelihood that this lesion is either a basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma—an impression bolstered by the contextual findings of advanced sun damage and the history of skin cancer. And yet, this patient finds himself with a nonhealing friable lesion that is at least 5 years old.

Repeated misdiagnosis as infection is actually a common occurrence. One suspects that at least some of the providers making this mistake followed the patient’s lead: Many affected patients assume such lesions represent infection and therefore demand treatment appropriate for that diagnosis.

As a rule, however, bacterial infections don’t last years, especially in the absence of pain and swelling. Yes, there are nonbacterial infections (eg, those caused by acid-fast bacilli) that can be just as, if not more, indolent, but they too are apt to be painful and swollen.

Biopsy, the obvious missing step in this entire saga, would rule out any of these odd things (including melanoma, which has been known to present in this atypical morphologic manner). Other items in the differential include pyogenic granuloma and metastatic cancer (eg, breast, colon, lung).

In this case, biopsy confirmed the lesion was (as expected) a basal cell carcinoma. The lesion was excised in 2 stages over a 2.5-month period. And the patient was reminded that he will remain at extremely high risk for additional sun-caused skin cancers for the rest of his life.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Nonhealing lesions should be assumed to be skin cancer until proven otherwise, especially in sun-damaged individuals.

- Correct treatment is dictated by correct diagnosis; in this case, a biopsy was clearly indicated.

- Besides the more common cancers (eg, basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma), there were numerous other items in the differential, including melanoma and even metastatic cancer.

- Only rarely do skin infections smolder for years without pain or surrounding erythema.

All the Little Lesions in a Row

A 10-year-old boy has had a lesion on his left foot for almost a year. It has not responded to either topical antifungal cream (econazole, applied twice daily for weeks) or, subsequently, topical corticosteroid cream (mometazone, also applied twice daily). Frustrated by the lack of resolution, his mother brings him for evaluation.

The condition began with faint linear scaling, the area of which became gradually wider and longer. The child reports no associated symptoms, and the mother denies seeing her son manipulate, rub, or scratch the affected skin.

Aside from mild atopy—in the form of seasonal allergies and asthma—the boy is healthy.

EXAMINATION

The child is well developed, well nourished, and in no distress. He gladly permits examination of the lesion, which is located on the dorsum of the left foot, running from the lower leg to just proximal to the toes. The linear strip of skin measures 2 cm at its widest point. The lesion is tan and uniformly scaly; it exhibits no overt signs of inflammation or increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

Examination reveals no other such lesions, or indeed any abnormalities. The adjacent toenails do not appear to be involved.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This child has a common condition called lichen striatus in modern times, but also known as linear lichenoid dermatitis, or (in older texts) Blaschko linear acquired inflammatory skin eruption. It has nothing to do with fungal infection.

This case illustrates a fairly typical presentation, but—as with most dermatologic conditions—there are many variants. For example, lichen striatus can present as a linear collection of scaly skin running the entire length of the leg (often beginning on the buttocks) and can even affect the toenails at its distal terminus. Although the line is usually solitary, lichen striatus can affect multiple locations simultaneously. Likewise, the lesions can run in an uninterrupted line, or stop and start at various points.

Skin type can affect the appearance of the lesions: on children with darker skin, lichen striatus usually appears lighter and on fair-skinned children, darker. The condition is more common in girls than boys (3:1) and occurs most often in those ages 5 to 15. The arms are another typical location, but it can even affect the face in rare instances. There is some support for atopy as a predisposing factor—but since almost 20% of all children are atopic, this is debatable.

Lichen striatus received its historical name because it follows Blaschko’s lines—named for Alfred Blaschko, a German dermatologist who first described the condition in 1901. These bizarre curving lines are now known to follow recognized patterns of embryonic cell migration that have nothing to do with neural, lymphatic, or vascular patterns as one might otherwise imagine. Several other skin conditions involve so-called blaschkoid features, including inflammatory linear verruciform nevi and some forms of epidermal nevi.

LS is not dangerous in any way, though it does cause considerable consternation among parents of affected children. Luckily, it causes few if any symptoms and is self-limited. A few children will complain of mild itching, for which class 4 or 5 topical steroids can be used. Within a year or two at most, the condition will resolve—albeit with occasional postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in those with darker skin.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen striatus is a common condition affecting children ages 5 to 15 who develop a linear, papulosquamous eruption that favors arms and leg (but can rarely involve the face).

- Not infrequently, the condition can cause dystrophy of the nails at the terminus of the lesions.

- The lesions follow Blaschko’s lines, which are thought to represent patterns of embryonic cell migration.

- The condition is seldom symptomatic, is self-limited, and rarely leaves permanent signs of damage.

A 10-year-old boy has had a lesion on his left foot for almost a year. It has not responded to either topical antifungal cream (econazole, applied twice daily for weeks) or, subsequently, topical corticosteroid cream (mometazone, also applied twice daily). Frustrated by the lack of resolution, his mother brings him for evaluation.

The condition began with faint linear scaling, the area of which became gradually wider and longer. The child reports no associated symptoms, and the mother denies seeing her son manipulate, rub, or scratch the affected skin.

Aside from mild atopy—in the form of seasonal allergies and asthma—the boy is healthy.

EXAMINATION

The child is well developed, well nourished, and in no distress. He gladly permits examination of the lesion, which is located on the dorsum of the left foot, running from the lower leg to just proximal to the toes. The linear strip of skin measures 2 cm at its widest point. The lesion is tan and uniformly scaly; it exhibits no overt signs of inflammation or increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

Examination reveals no other such lesions, or indeed any abnormalities. The adjacent toenails do not appear to be involved.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This child has a common condition called lichen striatus in modern times, but also known as linear lichenoid dermatitis, or (in older texts) Blaschko linear acquired inflammatory skin eruption. It has nothing to do with fungal infection.

This case illustrates a fairly typical presentation, but—as with most dermatologic conditions—there are many variants. For example, lichen striatus can present as a linear collection of scaly skin running the entire length of the leg (often beginning on the buttocks) and can even affect the toenails at its distal terminus. Although the line is usually solitary, lichen striatus can affect multiple locations simultaneously. Likewise, the lesions can run in an uninterrupted line, or stop and start at various points.

Skin type can affect the appearance of the lesions: on children with darker skin, lichen striatus usually appears lighter and on fair-skinned children, darker. The condition is more common in girls than boys (3:1) and occurs most often in those ages 5 to 15. The arms are another typical location, but it can even affect the face in rare instances. There is some support for atopy as a predisposing factor—but since almost 20% of all children are atopic, this is debatable.

Lichen striatus received its historical name because it follows Blaschko’s lines—named for Alfred Blaschko, a German dermatologist who first described the condition in 1901. These bizarre curving lines are now known to follow recognized patterns of embryonic cell migration that have nothing to do with neural, lymphatic, or vascular patterns as one might otherwise imagine. Several other skin conditions involve so-called blaschkoid features, including inflammatory linear verruciform nevi and some forms of epidermal nevi.

LS is not dangerous in any way, though it does cause considerable consternation among parents of affected children. Luckily, it causes few if any symptoms and is self-limited. A few children will complain of mild itching, for which class 4 or 5 topical steroids can be used. Within a year or two at most, the condition will resolve—albeit with occasional postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in those with darker skin.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen striatus is a common condition affecting children ages 5 to 15 who develop a linear, papulosquamous eruption that favors arms and leg (but can rarely involve the face).

- Not infrequently, the condition can cause dystrophy of the nails at the terminus of the lesions.

- The lesions follow Blaschko’s lines, which are thought to represent patterns of embryonic cell migration.

- The condition is seldom symptomatic, is self-limited, and rarely leaves permanent signs of damage.

A 10-year-old boy has had a lesion on his left foot for almost a year. It has not responded to either topical antifungal cream (econazole, applied twice daily for weeks) or, subsequently, topical corticosteroid cream (mometazone, also applied twice daily). Frustrated by the lack of resolution, his mother brings him for evaluation.

The condition began with faint linear scaling, the area of which became gradually wider and longer. The child reports no associated symptoms, and the mother denies seeing her son manipulate, rub, or scratch the affected skin.

Aside from mild atopy—in the form of seasonal allergies and asthma—the boy is healthy.

EXAMINATION

The child is well developed, well nourished, and in no distress. He gladly permits examination of the lesion, which is located on the dorsum of the left foot, running from the lower leg to just proximal to the toes. The linear strip of skin measures 2 cm at its widest point. The lesion is tan and uniformly scaly; it exhibits no overt signs of inflammation or increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

Examination reveals no other such lesions, or indeed any abnormalities. The adjacent toenails do not appear to be involved.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This child has a common condition called lichen striatus in modern times, but also known as linear lichenoid dermatitis, or (in older texts) Blaschko linear acquired inflammatory skin eruption. It has nothing to do with fungal infection.

This case illustrates a fairly typical presentation, but—as with most dermatologic conditions—there are many variants. For example, lichen striatus can present as a linear collection of scaly skin running the entire length of the leg (often beginning on the buttocks) and can even affect the toenails at its distal terminus. Although the line is usually solitary, lichen striatus can affect multiple locations simultaneously. Likewise, the lesions can run in an uninterrupted line, or stop and start at various points.

Skin type can affect the appearance of the lesions: on children with darker skin, lichen striatus usually appears lighter and on fair-skinned children, darker. The condition is more common in girls than boys (3:1) and occurs most often in those ages 5 to 15. The arms are another typical location, but it can even affect the face in rare instances. There is some support for atopy as a predisposing factor—but since almost 20% of all children are atopic, this is debatable.

Lichen striatus received its historical name because it follows Blaschko’s lines—named for Alfred Blaschko, a German dermatologist who first described the condition in 1901. These bizarre curving lines are now known to follow recognized patterns of embryonic cell migration that have nothing to do with neural, lymphatic, or vascular patterns as one might otherwise imagine. Several other skin conditions involve so-called blaschkoid features, including inflammatory linear verruciform nevi and some forms of epidermal nevi.

LS is not dangerous in any way, though it does cause considerable consternation among parents of affected children. Luckily, it causes few if any symptoms and is self-limited. A few children will complain of mild itching, for which class 4 or 5 topical steroids can be used. Within a year or two at most, the condition will resolve—albeit with occasional postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in those with darker skin.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen striatus is a common condition affecting children ages 5 to 15 who develop a linear, papulosquamous eruption that favors arms and leg (but can rarely involve the face).

- Not infrequently, the condition can cause dystrophy of the nails at the terminus of the lesions.

- The lesions follow Blaschko’s lines, which are thought to represent patterns of embryonic cell migration.

- The condition is seldom symptomatic, is self-limited, and rarely leaves permanent signs of damage.

When Skin Damage Takes Sides

A 61-year-old man is sent to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of several facial lesions. Although they have been present for years, the patient says they have never caused any symptoms.

The patient’s work history includes extensive outdoor activity, as well as more than 20 years of driving a truck. He is now retired and spends most of his days fishing.

He has a history of at least two unspecified skin cancers but denies receiving facial radiation treatment. He has been a smoker since age 12 and admits to heavy drinking.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s face is uneven in appearance, with deep wrinkles and multiple areas of discoloration. His skin is type III.

Multiple open and closed comedones are seen around the left malar and brow areas, where the underlying skin has a whitish look to it. The comedones are not inflamed, and no pustules are observed. Some of the comedones extend into the infra-orbital area on the left side of his face. Almost no such changes are seen on the right side.

There is no increase in hair in the affected areas and no skin changes observed on his hands or arms, other than moderately severe sun damage.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the 1930s, two French dermatologists, Favre and Racouchot, began to see several cases like this one. Following a review of available literature, they published their findings, calling the condition “nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones.” This quickly became known as Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS), the name it still bears today.

FRS is quite common, especially on the faces of white men older than 50. More men than woman are affected, and smoking almost certainly contributes to the problem.

The connection between FRS and sun exposure is well established: the basophilic degeneration of the dermis (solar elastosis) seen in FRS is identical to that seen from overexposure to the sun. Another clue to the cause is exemplified in cases involving truck drivers, since the side of the face nearest the window is usually affected more than the other side. In most countries, the left side of the face sustains the most damage; in countries with right-hand drive, the right side of the face is affected.

Significant focal nodular solar elastosis, along with open and closed comedones, notably worse on the more sun-exposed side, is unique to FRS. The lack of increase in facial hair in the affected area is significant, in that it effectively rules out the only other major item in the differential: porphyria cutanea tarda.

Treatment is problematic at best. Except in younger patients, sunscreens are largely a waste. The comedones can be manually extracted, but recurrence is certain. For the truly motivated patient, laser resurfacing and peels can help. To slow the progression of the disease, smoking cessation is necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is most commonly seen in older men with a history of excessive chronic sun exposure. Most are smokers.

- FRS primarily affects the malar and lateral brow areas with nodular elastosis, in which are embedded multiple cysts and comedones.

- In the United States, FRS is usually more pronounced on the left side of the face.

- Other signs of chronic sun damage (actinic weathering, also known as dermatoheliosis) are almost always seen over the entire face of FRS patients.

A 61-year-old man is sent to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of several facial lesions. Although they have been present for years, the patient says they have never caused any symptoms.

The patient’s work history includes extensive outdoor activity, as well as more than 20 years of driving a truck. He is now retired and spends most of his days fishing.

He has a history of at least two unspecified skin cancers but denies receiving facial radiation treatment. He has been a smoker since age 12 and admits to heavy drinking.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s face is uneven in appearance, with deep wrinkles and multiple areas of discoloration. His skin is type III.

Multiple open and closed comedones are seen around the left malar and brow areas, where the underlying skin has a whitish look to it. The comedones are not inflamed, and no pustules are observed. Some of the comedones extend into the infra-orbital area on the left side of his face. Almost no such changes are seen on the right side.

There is no increase in hair in the affected areas and no skin changes observed on his hands or arms, other than moderately severe sun damage.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the 1930s, two French dermatologists, Favre and Racouchot, began to see several cases like this one. Following a review of available literature, they published their findings, calling the condition “nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones.” This quickly became known as Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS), the name it still bears today.

FRS is quite common, especially on the faces of white men older than 50. More men than woman are affected, and smoking almost certainly contributes to the problem.

The connection between FRS and sun exposure is well established: the basophilic degeneration of the dermis (solar elastosis) seen in FRS is identical to that seen from overexposure to the sun. Another clue to the cause is exemplified in cases involving truck drivers, since the side of the face nearest the window is usually affected more than the other side. In most countries, the left side of the face sustains the most damage; in countries with right-hand drive, the right side of the face is affected.

Significant focal nodular solar elastosis, along with open and closed comedones, notably worse on the more sun-exposed side, is unique to FRS. The lack of increase in facial hair in the affected area is significant, in that it effectively rules out the only other major item in the differential: porphyria cutanea tarda.

Treatment is problematic at best. Except in younger patients, sunscreens are largely a waste. The comedones can be manually extracted, but recurrence is certain. For the truly motivated patient, laser resurfacing and peels can help. To slow the progression of the disease, smoking cessation is necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is most commonly seen in older men with a history of excessive chronic sun exposure. Most are smokers.

- FRS primarily affects the malar and lateral brow areas with nodular elastosis, in which are embedded multiple cysts and comedones.

- In the United States, FRS is usually more pronounced on the left side of the face.

- Other signs of chronic sun damage (actinic weathering, also known as dermatoheliosis) are almost always seen over the entire face of FRS patients.

A 61-year-old man is sent to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of several facial lesions. Although they have been present for years, the patient says they have never caused any symptoms.

The patient’s work history includes extensive outdoor activity, as well as more than 20 years of driving a truck. He is now retired and spends most of his days fishing.

He has a history of at least two unspecified skin cancers but denies receiving facial radiation treatment. He has been a smoker since age 12 and admits to heavy drinking.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s face is uneven in appearance, with deep wrinkles and multiple areas of discoloration. His skin is type III.

Multiple open and closed comedones are seen around the left malar and brow areas, where the underlying skin has a whitish look to it. The comedones are not inflamed, and no pustules are observed. Some of the comedones extend into the infra-orbital area on the left side of his face. Almost no such changes are seen on the right side.

There is no increase in hair in the affected areas and no skin changes observed on his hands or arms, other than moderately severe sun damage.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the 1930s, two French dermatologists, Favre and Racouchot, began to see several cases like this one. Following a review of available literature, they published their findings, calling the condition “nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones.” This quickly became known as Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS), the name it still bears today.

FRS is quite common, especially on the faces of white men older than 50. More men than woman are affected, and smoking almost certainly contributes to the problem.

The connection between FRS and sun exposure is well established: the basophilic degeneration of the dermis (solar elastosis) seen in FRS is identical to that seen from overexposure to the sun. Another clue to the cause is exemplified in cases involving truck drivers, since the side of the face nearest the window is usually affected more than the other side. In most countries, the left side of the face sustains the most damage; in countries with right-hand drive, the right side of the face is affected.

Significant focal nodular solar elastosis, along with open and closed comedones, notably worse on the more sun-exposed side, is unique to FRS. The lack of increase in facial hair in the affected area is significant, in that it effectively rules out the only other major item in the differential: porphyria cutanea tarda.

Treatment is problematic at best. Except in younger patients, sunscreens are largely a waste. The comedones can be manually extracted, but recurrence is certain. For the truly motivated patient, laser resurfacing and peels can help. To slow the progression of the disease, smoking cessation is necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is most commonly seen in older men with a history of excessive chronic sun exposure. Most are smokers.

- FRS primarily affects the malar and lateral brow areas with nodular elastosis, in which are embedded multiple cysts and comedones.

- In the United States, FRS is usually more pronounced on the left side of the face.

- Other signs of chronic sun damage (actinic weathering, also known as dermatoheliosis) are almost always seen over the entire face of FRS patients.

A Nuisance for the Newlyweds

Prompted by his new bride, who is concerned she might “catch something” from him, a 53-year-old man self-refers for evaluation of a slightly itchy intergluteal rash. He’s had it for years; it waxes and wanes but never fully resolves.

It has been previously diagnosed as a yeast infection, fungal infection, and even herpes. But none of the respective treatments have helped.

More history-taking reveals a family history of psoriasis (maternal grandmother), but the patient denies other areas of involvement or other skin changes. He also denies having arthritis.

EXAMINATION

A salmon-pink, 7-cm, roughly round dry patch covered by white tenacious scale is located in the upper intergluteal/sacral interface. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

A similar process is noted in the periumbilical area (a difficult area for this patient to see, due to his weight). Inspection of his fingernails reveals 3/10 with definite tiny pits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The urge to call any and every rash occurring near the genitals a yeast infection is universally compelling among primary care providers. It is often so reflexive that even when anti-yeast medications fail, the provider hangs onto the diagnosis. This happens for one simple reason: Their differential is lacking.

This patient has psoriasis, albeit a somewhat unusual form, which demonstrates an important learning point: Psoriasis can present in any number of ways, not just in the standard “extensor surfaces of elbows and knees” distribution. It’s not unusual for psoriasis to zero in on one or two areas. I’ve seen it confined to the groin, the genitals, and the scalp. It can even involve the oral mucosa.

In these somewhat obscure cases, additional findings can be helpful to establish the diagnosis. The two areas of involvement in this case—the upper intergluteal area and the periumbilical region—may not fit the classic “knees and elbows” picture of psoriasis, but they are not atypical for the disease. Add the nail pits, the fixed nature of the problem, and the family history, and you’ve nailed the diagnosis.

Don’t forget that, occasionally, psoriatic arthropathy can precede the appearance of psoriasis, and that the severity of one does not predict the severity of the other.

Finally, in a fair number of cases, the diagnosis of psoriasis must be made by biopsy, which shows characteristic changes such as parakeratosis, epidermal thickening, and fusing of rete ridges. These “psoriasiform” changes seen microscopically must be corroborated by clinical findings, though, since many other papulosquamous diseases can exhibit similar changes.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is one of the more common dermatoses in this country, which means you will see it with some frequency.

- Psoriasis can affect limited or atypical areas, but corroboration of the diagnosis can be sought in classic areas (nails, scalp, upper intergluteal and periumbilical areas).

- Strive to develop alternative diagnoses for similar rashes—in other words, build your differential for “yeast infection.”

Prompted by his new bride, who is concerned she might “catch something” from him, a 53-year-old man self-refers for evaluation of a slightly itchy intergluteal rash. He’s had it for years; it waxes and wanes but never fully resolves.

It has been previously diagnosed as a yeast infection, fungal infection, and even herpes. But none of the respective treatments have helped.

More history-taking reveals a family history of psoriasis (maternal grandmother), but the patient denies other areas of involvement or other skin changes. He also denies having arthritis.

EXAMINATION

A salmon-pink, 7-cm, roughly round dry patch covered by white tenacious scale is located in the upper intergluteal/sacral interface. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

A similar process is noted in the periumbilical area (a difficult area for this patient to see, due to his weight). Inspection of his fingernails reveals 3/10 with definite tiny pits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The urge to call any and every rash occurring near the genitals a yeast infection is universally compelling among primary care providers. It is often so reflexive that even when anti-yeast medications fail, the provider hangs onto the diagnosis. This happens for one simple reason: Their differential is lacking.

This patient has psoriasis, albeit a somewhat unusual form, which demonstrates an important learning point: Psoriasis can present in any number of ways, not just in the standard “extensor surfaces of elbows and knees” distribution. It’s not unusual for psoriasis to zero in on one or two areas. I’ve seen it confined to the groin, the genitals, and the scalp. It can even involve the oral mucosa.

In these somewhat obscure cases, additional findings can be helpful to establish the diagnosis. The two areas of involvement in this case—the upper intergluteal area and the periumbilical region—may not fit the classic “knees and elbows” picture of psoriasis, but they are not atypical for the disease. Add the nail pits, the fixed nature of the problem, and the family history, and you’ve nailed the diagnosis.

Don’t forget that, occasionally, psoriatic arthropathy can precede the appearance of psoriasis, and that the severity of one does not predict the severity of the other.

Finally, in a fair number of cases, the diagnosis of psoriasis must be made by biopsy, which shows characteristic changes such as parakeratosis, epidermal thickening, and fusing of rete ridges. These “psoriasiform” changes seen microscopically must be corroborated by clinical findings, though, since many other papulosquamous diseases can exhibit similar changes.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is one of the more common dermatoses in this country, which means you will see it with some frequency.

- Psoriasis can affect limited or atypical areas, but corroboration of the diagnosis can be sought in classic areas (nails, scalp, upper intergluteal and periumbilical areas).

- Strive to develop alternative diagnoses for similar rashes—in other words, build your differential for “yeast infection.”

Prompted by his new bride, who is concerned she might “catch something” from him, a 53-year-old man self-refers for evaluation of a slightly itchy intergluteal rash. He’s had it for years; it waxes and wanes but never fully resolves.

It has been previously diagnosed as a yeast infection, fungal infection, and even herpes. But none of the respective treatments have helped.

More history-taking reveals a family history of psoriasis (maternal grandmother), but the patient denies other areas of involvement or other skin changes. He also denies having arthritis.

EXAMINATION

A salmon-pink, 7-cm, roughly round dry patch covered by white tenacious scale is located in the upper intergluteal/sacral interface. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

A similar process is noted in the periumbilical area (a difficult area for this patient to see, due to his weight). Inspection of his fingernails reveals 3/10 with definite tiny pits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The urge to call any and every rash occurring near the genitals a yeast infection is universally compelling among primary care providers. It is often so reflexive that even when anti-yeast medications fail, the provider hangs onto the diagnosis. This happens for one simple reason: Their differential is lacking.

This patient has psoriasis, albeit a somewhat unusual form, which demonstrates an important learning point: Psoriasis can present in any number of ways, not just in the standard “extensor surfaces of elbows and knees” distribution. It’s not unusual for psoriasis to zero in on one or two areas. I’ve seen it confined to the groin, the genitals, and the scalp. It can even involve the oral mucosa.

In these somewhat obscure cases, additional findings can be helpful to establish the diagnosis. The two areas of involvement in this case—the upper intergluteal area and the periumbilical region—may not fit the classic “knees and elbows” picture of psoriasis, but they are not atypical for the disease. Add the nail pits, the fixed nature of the problem, and the family history, and you’ve nailed the diagnosis.

Don’t forget that, occasionally, psoriatic arthropathy can precede the appearance of psoriasis, and that the severity of one does not predict the severity of the other.

Finally, in a fair number of cases, the diagnosis of psoriasis must be made by biopsy, which shows characteristic changes such as parakeratosis, epidermal thickening, and fusing of rete ridges. These “psoriasiform” changes seen microscopically must be corroborated by clinical findings, though, since many other papulosquamous diseases can exhibit similar changes.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is one of the more common dermatoses in this country, which means you will see it with some frequency.

- Psoriasis can affect limited or atypical areas, but corroboration of the diagnosis can be sought in classic areas (nails, scalp, upper intergluteal and periumbilical areas).

- Strive to develop alternative diagnoses for similar rashes—in other words, build your differential for “yeast infection.”

“It Gets Better With Age”

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Location Does Not Matter

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

No similar changes are seen on the elbows, knees, scalp, trunk, or nails.

A biopsy of the lesion is performed. The pathology report shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The morphology of this lesion is a perfect fit for psoriasis, a very common disease affecting about 3% of the white population in this country. Mentally repositioning this lesion to the elbow, trunk, or knee would have made the diagnosis obvious; these are the most commonly affected areas, while the genitals are among the least common. But a white-feathered bird with an orange bill and feet who greets you with a quack is probably a duck, even if it’s sitting on your dining room table.

Even for an experienced dermatology provider (35 years in the field), seeing this lesion in this location was a momentary shock. After all, there’s an 18-item differential for genital rashes—but very few look like this.

Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus is commonly seen on young girls in this area, but it is atrophic with almost no scale. Lichen simplex chronicus can be scaly and plaquish, but it rarely appears this organized.

In most primary care settings, this would be (and was) called a “yeast infection.” Not only do yeast infections not look a thing like this, there also needs to be an underlying reason for that diagnosis (eg, use of antibiotics, history of diabetes).

Biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, to give the family some peace of mind and guide appropriate therapy.

We discussed the diagnosis thoroughly with the parents, including the etiology, potential treatments, and prognosis. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. If it proves necessary, we could increase the potency of the steroid, inject the lesion with steroid, or even start her on methotrexate.

She’ll also be closely followed for signs of worsening disease and for psoriatic arthropathy, which affects almost 25% of patients with psoriasis. She’ll be fortunate if this is the extent of her disease.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Salmon-pink, scaly plaques are psoriatic until proven otherwise.

- Psoriasis is common, affecting almost 3% of the white population.

- Though most often seen on extensor surfaces of arms, legs, and trunk, psoriasis can appear virtually anywhere.

- Mentally transpositioning a lesion to another location can be helpful in sorting through this differential.

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.