User login

Is colonoscopy indicated if only one of 3 stool samples is positive for occult blood?

Yes. Any occult blood on a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) should be investigated further because colorectal cancer mortality decreases when positive FOBT screenings are evaluated (strength of recommendation: A, systematic review, evidence-based guidelines).

Follow-up of positive screening results lowers colorectal cancer mortality

No studies directly compare the need for colonoscopy when various numbers of stool samples are positive for occult blood on an FOBT. However, a Cochrane review of 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with more than 300,000 patients examined the effectiveness of the FOBT for colorectal cancer screening.1 Each study varied in its follow-up approach to a positive FOBT.

Two RCTs offered screening with FOBT or standard care (no screening) and immediately followed up any positive results with a colonoscopy. The screened group had lower colorectal cancer mortality (N=46,551; risk ratio [RR]=0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62-0.91) than the unscreened group (N=61,933; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.96).

Another trial screened with FOBT or standard care and offered colonoscopy if 5 or more samples were positive on initial testing or one or more were positive on repeat testing. The screened group showed reduced colorectal cancer mortality (N=152,850; RR=0.87; 95% CI, 0.78-0.97).

The final trial examined screening with FOBT compared with standard care and inconsistently offered repeat FOBT or sigmoidoscopy with double-contrast barium enema if any samples were positive on initial testing, which resulted in decreased colorectal cancer mortality for the screened group (N=68,308; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.99).

Evidence-based guidelines recommend follow-up colonoscopy

Evidence-based guidelines from the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the European Commission, and the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care state that FOBT should be used for colorectal cancer screening and that any positive screening test should be followed up with colonoscopy to further evaluate for neoplasm.2-4

An evidence- and expert opinion-based guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology clarifies the issue further by emphasizing that any positive FOBT necessitates a colonoscopy and stating that repeat FOBT or other test is inappropriate as follow-up.5

1. Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1541-1549.

2. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627-638.

3. vonKarsa L, Patnick J, Segnan N, eds. European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2010.

4. McLeod RS; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Screening strategies for colorectal cancer: a systematic review of the evidence. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:647-660.

5. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-1595.

Yes. Any occult blood on a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) should be investigated further because colorectal cancer mortality decreases when positive FOBT screenings are evaluated (strength of recommendation: A, systematic review, evidence-based guidelines).

Follow-up of positive screening results lowers colorectal cancer mortality

No studies directly compare the need for colonoscopy when various numbers of stool samples are positive for occult blood on an FOBT. However, a Cochrane review of 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with more than 300,000 patients examined the effectiveness of the FOBT for colorectal cancer screening.1 Each study varied in its follow-up approach to a positive FOBT.

Two RCTs offered screening with FOBT or standard care (no screening) and immediately followed up any positive results with a colonoscopy. The screened group had lower colorectal cancer mortality (N=46,551; risk ratio [RR]=0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62-0.91) than the unscreened group (N=61,933; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.96).

Another trial screened with FOBT or standard care and offered colonoscopy if 5 or more samples were positive on initial testing or one or more were positive on repeat testing. The screened group showed reduced colorectal cancer mortality (N=152,850; RR=0.87; 95% CI, 0.78-0.97).

The final trial examined screening with FOBT compared with standard care and inconsistently offered repeat FOBT or sigmoidoscopy with double-contrast barium enema if any samples were positive on initial testing, which resulted in decreased colorectal cancer mortality for the screened group (N=68,308; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.99).

Evidence-based guidelines recommend follow-up colonoscopy

Evidence-based guidelines from the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the European Commission, and the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care state that FOBT should be used for colorectal cancer screening and that any positive screening test should be followed up with colonoscopy to further evaluate for neoplasm.2-4

An evidence- and expert opinion-based guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology clarifies the issue further by emphasizing that any positive FOBT necessitates a colonoscopy and stating that repeat FOBT or other test is inappropriate as follow-up.5

Yes. Any occult blood on a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) should be investigated further because colorectal cancer mortality decreases when positive FOBT screenings are evaluated (strength of recommendation: A, systematic review, evidence-based guidelines).

Follow-up of positive screening results lowers colorectal cancer mortality

No studies directly compare the need for colonoscopy when various numbers of stool samples are positive for occult blood on an FOBT. However, a Cochrane review of 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with more than 300,000 patients examined the effectiveness of the FOBT for colorectal cancer screening.1 Each study varied in its follow-up approach to a positive FOBT.

Two RCTs offered screening with FOBT or standard care (no screening) and immediately followed up any positive results with a colonoscopy. The screened group had lower colorectal cancer mortality (N=46,551; risk ratio [RR]=0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62-0.91) than the unscreened group (N=61,933; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.96).

Another trial screened with FOBT or standard care and offered colonoscopy if 5 or more samples were positive on initial testing or one or more were positive on repeat testing. The screened group showed reduced colorectal cancer mortality (N=152,850; RR=0.87; 95% CI, 0.78-0.97).

The final trial examined screening with FOBT compared with standard care and inconsistently offered repeat FOBT or sigmoidoscopy with double-contrast barium enema if any samples were positive on initial testing, which resulted in decreased colorectal cancer mortality for the screened group (N=68,308; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.99).

Evidence-based guidelines recommend follow-up colonoscopy

Evidence-based guidelines from the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the European Commission, and the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care state that FOBT should be used for colorectal cancer screening and that any positive screening test should be followed up with colonoscopy to further evaluate for neoplasm.2-4

An evidence- and expert opinion-based guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology clarifies the issue further by emphasizing that any positive FOBT necessitates a colonoscopy and stating that repeat FOBT or other test is inappropriate as follow-up.5

1. Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1541-1549.

2. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627-638.

3. vonKarsa L, Patnick J, Segnan N, eds. European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2010.

4. McLeod RS; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Screening strategies for colorectal cancer: a systematic review of the evidence. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:647-660.

5. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-1595.

1. Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1541-1549.

2. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627-638.

3. vonKarsa L, Patnick J, Segnan N, eds. European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2010.

4. McLeod RS; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Screening strategies for colorectal cancer: a systematic review of the evidence. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:647-660.

5. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-1595.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Do hormonal contraceptives lead to weight gain?

It depends. Weight doesn’t appear to increase with combined oral contraception (OC) compared with nonhormonal contraception, but percent body fat may increase slightly. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (DMPA) users experience weight gain compared with OC and nonhormonal contraception (NH) users (strength of recommendation: B, cohort studies).

DMPA users gain more weight and body fat than OC users

A 2008 prospective, nonrandomized, controlled study of 703 women compared changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio in 245 women using OC, 240 using DMPA, and 218 using NH methods of birth control.1 Over the 36-month follow-up period, 257 women were lost to follow-up, 137 discontinued participation because they wanted a different contraceptive method, and 123 didn’t complete the study for other reasons.

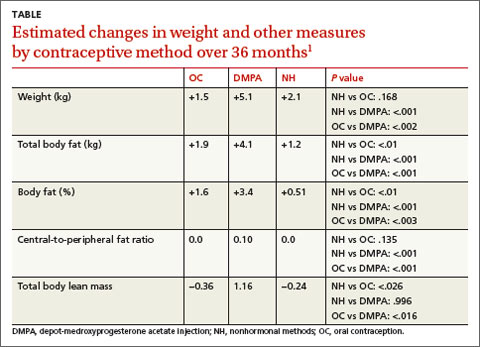

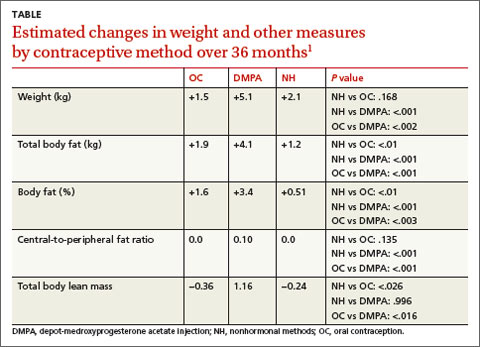

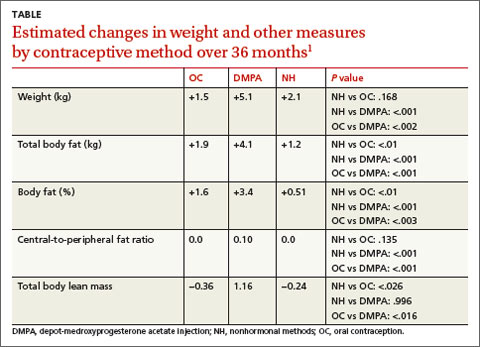

Compared to OC and NH users, DMPA users gained more actual weight (+5.1 kg) and body fat (+4.1 kg) and increased their percent body fat (+3.4%) and central-to-peripheral fat ratio (+0.1; P<.01 in all models). OC use wasn’t associated with weight gain compared with the NH group but did increase OC users’ percent body fat by 1.6% (P<.01) and decrease their total lean body mass by 0.36 (P<.026) (TABLE1).

DMPA users gain more weight in specific populations

For 18 months, researchers conducting a large prospective, nonrandomized study followed American adolescents ages 12 to 18 years who used DMPA and were classified as obese (defined as a baseline body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) to determine how their weight gain compared with obese combined OC users and obese controls.2

Obese DMPA users gained significantly more weight (9.4 kg) than obese combined OC users (0.2 kg; P<.001) and obese controls (3.1 kg; P<.001). Of the 450 patients, 280 (62%) identified themselves as black and 170 (38%) identified themselves as nonblack.

In another retrospective cohort study of 379 adult women from a Brazilian public family planning clinic, current or past DMPA users were matched with copper T 30A intrauterine device users for age and baseline BMI and categorized into 3 groups: G1 (BMI <25 kg/m2), G2 (25-29.9 kg/m2), or G3 (≥30 kg/m2).3

At the end of the third year of use, the mean increase in weight for the normal weight group (G1) and the overweight group (G2) was greater in DMPA users than in DMPA nonusers (4.5 kg vs 1.2 kg in G1; P<.0107; 3.4 kg vs 0.2 kg in G2; P<.0001). In the obese group (G3), the difference in weight gain between DMPA users and DMPA nonusers was minimal (1.9 kg vs 0.6 kg; P=not significant).

One limitation of these 2 studies could be that the women under investigation were from defined populations—black urban adolescents and a public family planning service.

1. Berenson AB, Rahman M. Changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio associated with injectable and oral contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:329.e1-8.

2. Bonny AE, Ziegler J, Harvey R, et al. Weight gain in obese and nonobese adolescent girls initiating depot medroxyprogesterone, oral contraceptive pills, or no hormonal contraceptive method. Arch PediatrAdolesc Med. 2006;160:40-45.

3. Pantoja M, Medeiros T, Baccarin MC, et al. Variations in body mass index of users of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 2010;81:107-111.

It depends. Weight doesn’t appear to increase with combined oral contraception (OC) compared with nonhormonal contraception, but percent body fat may increase slightly. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (DMPA) users experience weight gain compared with OC and nonhormonal contraception (NH) users (strength of recommendation: B, cohort studies).

DMPA users gain more weight and body fat than OC users

A 2008 prospective, nonrandomized, controlled study of 703 women compared changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio in 245 women using OC, 240 using DMPA, and 218 using NH methods of birth control.1 Over the 36-month follow-up period, 257 women were lost to follow-up, 137 discontinued participation because they wanted a different contraceptive method, and 123 didn’t complete the study for other reasons.

Compared to OC and NH users, DMPA users gained more actual weight (+5.1 kg) and body fat (+4.1 kg) and increased their percent body fat (+3.4%) and central-to-peripheral fat ratio (+0.1; P<.01 in all models). OC use wasn’t associated with weight gain compared with the NH group but did increase OC users’ percent body fat by 1.6% (P<.01) and decrease their total lean body mass by 0.36 (P<.026) (TABLE1).

DMPA users gain more weight in specific populations

For 18 months, researchers conducting a large prospective, nonrandomized study followed American adolescents ages 12 to 18 years who used DMPA and were classified as obese (defined as a baseline body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) to determine how their weight gain compared with obese combined OC users and obese controls.2

Obese DMPA users gained significantly more weight (9.4 kg) than obese combined OC users (0.2 kg; P<.001) and obese controls (3.1 kg; P<.001). Of the 450 patients, 280 (62%) identified themselves as black and 170 (38%) identified themselves as nonblack.

In another retrospective cohort study of 379 adult women from a Brazilian public family planning clinic, current or past DMPA users were matched with copper T 30A intrauterine device users for age and baseline BMI and categorized into 3 groups: G1 (BMI <25 kg/m2), G2 (25-29.9 kg/m2), or G3 (≥30 kg/m2).3

At the end of the third year of use, the mean increase in weight for the normal weight group (G1) and the overweight group (G2) was greater in DMPA users than in DMPA nonusers (4.5 kg vs 1.2 kg in G1; P<.0107; 3.4 kg vs 0.2 kg in G2; P<.0001). In the obese group (G3), the difference in weight gain between DMPA users and DMPA nonusers was minimal (1.9 kg vs 0.6 kg; P=not significant).

One limitation of these 2 studies could be that the women under investigation were from defined populations—black urban adolescents and a public family planning service.

It depends. Weight doesn’t appear to increase with combined oral contraception (OC) compared with nonhormonal contraception, but percent body fat may increase slightly. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (DMPA) users experience weight gain compared with OC and nonhormonal contraception (NH) users (strength of recommendation: B, cohort studies).

DMPA users gain more weight and body fat than OC users

A 2008 prospective, nonrandomized, controlled study of 703 women compared changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio in 245 women using OC, 240 using DMPA, and 218 using NH methods of birth control.1 Over the 36-month follow-up period, 257 women were lost to follow-up, 137 discontinued participation because they wanted a different contraceptive method, and 123 didn’t complete the study for other reasons.

Compared to OC and NH users, DMPA users gained more actual weight (+5.1 kg) and body fat (+4.1 kg) and increased their percent body fat (+3.4%) and central-to-peripheral fat ratio (+0.1; P<.01 in all models). OC use wasn’t associated with weight gain compared with the NH group but did increase OC users’ percent body fat by 1.6% (P<.01) and decrease their total lean body mass by 0.36 (P<.026) (TABLE1).

DMPA users gain more weight in specific populations

For 18 months, researchers conducting a large prospective, nonrandomized study followed American adolescents ages 12 to 18 years who used DMPA and were classified as obese (defined as a baseline body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) to determine how their weight gain compared with obese combined OC users and obese controls.2

Obese DMPA users gained significantly more weight (9.4 kg) than obese combined OC users (0.2 kg; P<.001) and obese controls (3.1 kg; P<.001). Of the 450 patients, 280 (62%) identified themselves as black and 170 (38%) identified themselves as nonblack.

In another retrospective cohort study of 379 adult women from a Brazilian public family planning clinic, current or past DMPA users were matched with copper T 30A intrauterine device users for age and baseline BMI and categorized into 3 groups: G1 (BMI <25 kg/m2), G2 (25-29.9 kg/m2), or G3 (≥30 kg/m2).3

At the end of the third year of use, the mean increase in weight for the normal weight group (G1) and the overweight group (G2) was greater in DMPA users than in DMPA nonusers (4.5 kg vs 1.2 kg in G1; P<.0107; 3.4 kg vs 0.2 kg in G2; P<.0001). In the obese group (G3), the difference in weight gain between DMPA users and DMPA nonusers was minimal (1.9 kg vs 0.6 kg; P=not significant).

One limitation of these 2 studies could be that the women under investigation were from defined populations—black urban adolescents and a public family planning service.

1. Berenson AB, Rahman M. Changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio associated with injectable and oral contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:329.e1-8.

2. Bonny AE, Ziegler J, Harvey R, et al. Weight gain in obese and nonobese adolescent girls initiating depot medroxyprogesterone, oral contraceptive pills, or no hormonal contraceptive method. Arch PediatrAdolesc Med. 2006;160:40-45.

3. Pantoja M, Medeiros T, Baccarin MC, et al. Variations in body mass index of users of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 2010;81:107-111.

1. Berenson AB, Rahman M. Changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio associated with injectable and oral contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:329.e1-8.

2. Bonny AE, Ziegler J, Harvey R, et al. Weight gain in obese and nonobese adolescent girls initiating depot medroxyprogesterone, oral contraceptive pills, or no hormonal contraceptive method. Arch PediatrAdolesc Med. 2006;160:40-45.

3. Pantoja M, Medeiros T, Baccarin MC, et al. Variations in body mass index of users of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 2010;81:107-111.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Is it safe to add long-acting β-2 agonists to inhaled corticosteroids in patients with persistent asthma?

Possibly. Long-acting β-2 agonists (LABAs) used in combination with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) don’t appear to increase all-cause mortality or serious adverse events in patients with persistent asthma compared with ICS alone. Studies showing an increase in catastrophic events had serious methodologic issues. A large surveillance study is ongoing (strength of recommendation: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

No significant difference in combination therapy vs ICS alone

In 2013, a Cochrane review analyzed the risk of mortality and nonfatal serious adverse events in patients treated with the LABA salmeterol in combination with ICS, compared with patients receiving the same dose of ICS alone.1 The review included 35 RCTs of moderate quality with 13,447 adolescents and adults and 5 RCTs with 1862 children. Patients had all stages of asthma; mean study duration was 34 weeks in adult trials and 15 weeks in trials of children.

Seven deaths from all causes occurred in both the salmeterol-plus-ICS group and the ICS-alone group (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto odds ratio [OR]=0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31-2.6). No deaths in children and no asthma-related deaths occurred in any study participants (40 trials, N=15,309).

Adults treated with ICS alone showed no significant difference from adults receiving combination therapy in the frequency of serious adverse events (defined as life threatening, requiring hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, or resulting in persistent or significant disability or incapacity). Adults on ICS had 21 events per 1000 compared with 24 per 1000 in adults on combination treatment (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto OR=1.2; 95% CI, 0.91-1.4).

Asthma-related serious adverse events were reported in 29 of 6986 adults in the combination group and 23 of 6461 in the ICS-alone group, a nonsignificant difference (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto OR=1.1; 95% CI, 0.65-1.9).

Only one serious asthma-related adverse event occurred in each group of children (ICS- and combination-treated); (5 trials, N=1862; Peto OR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.6-16). Because the number of events was so small and the results were so imprecise, a relative increase in all-cause mortality or nonfatal adverse events can’t be completely ruled out.

Inconsistent dosages mar trials that show more catastrophic events

A systematic review of 7 RCTs with 7253 asthmatic patients compared LABA plus ICS or ICS alone at various doses. All of the trials included at least one catastrophic event, defined as an asthma-related intubation or death.2 The mean ages of the patients varied from 11 to 48 years, and the length of the studies from 12 to 52 weeks. The risk of catastrophic events was greater in the LABA plus ICS groups than ICS alone (OR=3.7; 95% CI, 1.4-9.6).

Only one of the 7 trials was included in the 2013 Cochrane review. The others were excluded because the control groups used different doses of ICS than the LABA-plus-ICS groups. In one trial, for example, the ICS group used 4 times the dose of budesonide used in the LABA-plus-ICS group. The difference in outcomes may therefore reflect the variation in ICS dose rather than the presence or absence of LABA.

Because of these conflicting results, the US Food and Drug Administration has mandated continued evaluation of LABAs by manufacturers.3 Five clinical trials that are multinational, randomized, double-blind, and lasting at least 6 months will evaluate the safety of LABAs plus fixed-dose ICS compared with fixed-dose ICS alone. A total of 6200 children and 46,800 adults will be enrolled in the studies, whose results should be available in 2017.

1. Cates CJ, Jaeschke R, Schmidt S, et al. Regular treatment with salmeterol and inhaled steroids for chronic asthma: serious adverse events. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD006922.

2. Salpeter SR, Wall AJ, Buckley NS. Long-acting beta-agonists with and without inhaled corticosteroids and catastrophic asthma events. Am J Med. 2010;123:322-328.

3. Chowdhury BA, Seymour SM, Levenson MS. Assessing the safety of adding LABAs to inhaled corticosteroids for treating asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2473-2475.

Possibly. Long-acting β-2 agonists (LABAs) used in combination with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) don’t appear to increase all-cause mortality or serious adverse events in patients with persistent asthma compared with ICS alone. Studies showing an increase in catastrophic events had serious methodologic issues. A large surveillance study is ongoing (strength of recommendation: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

No significant difference in combination therapy vs ICS alone

In 2013, a Cochrane review analyzed the risk of mortality and nonfatal serious adverse events in patients treated with the LABA salmeterol in combination with ICS, compared with patients receiving the same dose of ICS alone.1 The review included 35 RCTs of moderate quality with 13,447 adolescents and adults and 5 RCTs with 1862 children. Patients had all stages of asthma; mean study duration was 34 weeks in adult trials and 15 weeks in trials of children.

Seven deaths from all causes occurred in both the salmeterol-plus-ICS group and the ICS-alone group (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto odds ratio [OR]=0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31-2.6). No deaths in children and no asthma-related deaths occurred in any study participants (40 trials, N=15,309).

Adults treated with ICS alone showed no significant difference from adults receiving combination therapy in the frequency of serious adverse events (defined as life threatening, requiring hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, or resulting in persistent or significant disability or incapacity). Adults on ICS had 21 events per 1000 compared with 24 per 1000 in adults on combination treatment (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto OR=1.2; 95% CI, 0.91-1.4).

Asthma-related serious adverse events were reported in 29 of 6986 adults in the combination group and 23 of 6461 in the ICS-alone group, a nonsignificant difference (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto OR=1.1; 95% CI, 0.65-1.9).

Only one serious asthma-related adverse event occurred in each group of children (ICS- and combination-treated); (5 trials, N=1862; Peto OR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.6-16). Because the number of events was so small and the results were so imprecise, a relative increase in all-cause mortality or nonfatal adverse events can’t be completely ruled out.

Inconsistent dosages mar trials that show more catastrophic events

A systematic review of 7 RCTs with 7253 asthmatic patients compared LABA plus ICS or ICS alone at various doses. All of the trials included at least one catastrophic event, defined as an asthma-related intubation or death.2 The mean ages of the patients varied from 11 to 48 years, and the length of the studies from 12 to 52 weeks. The risk of catastrophic events was greater in the LABA plus ICS groups than ICS alone (OR=3.7; 95% CI, 1.4-9.6).

Only one of the 7 trials was included in the 2013 Cochrane review. The others were excluded because the control groups used different doses of ICS than the LABA-plus-ICS groups. In one trial, for example, the ICS group used 4 times the dose of budesonide used in the LABA-plus-ICS group. The difference in outcomes may therefore reflect the variation in ICS dose rather than the presence or absence of LABA.

Because of these conflicting results, the US Food and Drug Administration has mandated continued evaluation of LABAs by manufacturers.3 Five clinical trials that are multinational, randomized, double-blind, and lasting at least 6 months will evaluate the safety of LABAs plus fixed-dose ICS compared with fixed-dose ICS alone. A total of 6200 children and 46,800 adults will be enrolled in the studies, whose results should be available in 2017.

Possibly. Long-acting β-2 agonists (LABAs) used in combination with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) don’t appear to increase all-cause mortality or serious adverse events in patients with persistent asthma compared with ICS alone. Studies showing an increase in catastrophic events had serious methodologic issues. A large surveillance study is ongoing (strength of recommendation: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

No significant difference in combination therapy vs ICS alone

In 2013, a Cochrane review analyzed the risk of mortality and nonfatal serious adverse events in patients treated with the LABA salmeterol in combination with ICS, compared with patients receiving the same dose of ICS alone.1 The review included 35 RCTs of moderate quality with 13,447 adolescents and adults and 5 RCTs with 1862 children. Patients had all stages of asthma; mean study duration was 34 weeks in adult trials and 15 weeks in trials of children.

Seven deaths from all causes occurred in both the salmeterol-plus-ICS group and the ICS-alone group (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto odds ratio [OR]=0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31-2.6). No deaths in children and no asthma-related deaths occurred in any study participants (40 trials, N=15,309).

Adults treated with ICS alone showed no significant difference from adults receiving combination therapy in the frequency of serious adverse events (defined as life threatening, requiring hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, or resulting in persistent or significant disability or incapacity). Adults on ICS had 21 events per 1000 compared with 24 per 1000 in adults on combination treatment (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto OR=1.2; 95% CI, 0.91-1.4).

Asthma-related serious adverse events were reported in 29 of 6986 adults in the combination group and 23 of 6461 in the ICS-alone group, a nonsignificant difference (35 trials, N=13,447; Peto OR=1.1; 95% CI, 0.65-1.9).

Only one serious asthma-related adverse event occurred in each group of children (ICS- and combination-treated); (5 trials, N=1862; Peto OR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.6-16). Because the number of events was so small and the results were so imprecise, a relative increase in all-cause mortality or nonfatal adverse events can’t be completely ruled out.

Inconsistent dosages mar trials that show more catastrophic events

A systematic review of 7 RCTs with 7253 asthmatic patients compared LABA plus ICS or ICS alone at various doses. All of the trials included at least one catastrophic event, defined as an asthma-related intubation or death.2 The mean ages of the patients varied from 11 to 48 years, and the length of the studies from 12 to 52 weeks. The risk of catastrophic events was greater in the LABA plus ICS groups than ICS alone (OR=3.7; 95% CI, 1.4-9.6).

Only one of the 7 trials was included in the 2013 Cochrane review. The others were excluded because the control groups used different doses of ICS than the LABA-plus-ICS groups. In one trial, for example, the ICS group used 4 times the dose of budesonide used in the LABA-plus-ICS group. The difference in outcomes may therefore reflect the variation in ICS dose rather than the presence or absence of LABA.

Because of these conflicting results, the US Food and Drug Administration has mandated continued evaluation of LABAs by manufacturers.3 Five clinical trials that are multinational, randomized, double-blind, and lasting at least 6 months will evaluate the safety of LABAs plus fixed-dose ICS compared with fixed-dose ICS alone. A total of 6200 children and 46,800 adults will be enrolled in the studies, whose results should be available in 2017.

1. Cates CJ, Jaeschke R, Schmidt S, et al. Regular treatment with salmeterol and inhaled steroids for chronic asthma: serious adverse events. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD006922.

2. Salpeter SR, Wall AJ, Buckley NS. Long-acting beta-agonists with and without inhaled corticosteroids and catastrophic asthma events. Am J Med. 2010;123:322-328.

3. Chowdhury BA, Seymour SM, Levenson MS. Assessing the safety of adding LABAs to inhaled corticosteroids for treating asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2473-2475.

1. Cates CJ, Jaeschke R, Schmidt S, et al. Regular treatment with salmeterol and inhaled steroids for chronic asthma: serious adverse events. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD006922.

2. Salpeter SR, Wall AJ, Buckley NS. Long-acting beta-agonists with and without inhaled corticosteroids and catastrophic asthma events. Am J Med. 2010;123:322-328.

3. Chowdhury BA, Seymour SM, Levenson MS. Assessing the safety of adding LABAs to inhaled corticosteroids for treating asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2473-2475.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the most effective topical treatment for allergic conjunctivitis?

Topical antihistamines and topical mast cell stabilizers appear to reduce conjunctival injection and itching effectively. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also effective, but may sting on application (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both of these treatments relieve redness and itching

A 2004 systematic review of 40 RCTs (total N not provided) assessed the efficacy of topical treatment with mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines, comparing each with the other and placebo.1 Eleven trials that included 899 children and adults compared mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil, and lodoxamide tromethamine) with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 9 weeks.

Because of study heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used and showed that topical mast cell stabilizers relieved symptoms (ocular itching, burning, and lacrimation) 4.9 times more effectively than placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5-9.6). Possible publication bias was cited as a limitation.

In the same systematic review, 9 RCTs with 313 patients compared topical antihistamines (levocabastine, azelastine hydrochloride, emedastine, and antazoline phosphate) with placebo. Signs and symptoms (itching, redness, burning, and swelling) were graded using symptom severity scales. Follow-up ranged from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with these scores. Most individual studies, however, showed improvement in the cardinal symptom of itchiness.

Finally, 8 RCTs compared topical mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, lodoxamide, and nedocromil sodium) with levocabastine, a topical antihistamine. Two RCTs with 74 patients had follow-up periods of 15 minutes to 4 hours; the remaining 6 RCTs with 473 patients had follow-up periods of 14 days to 4 months. Subjective scoring of symptoms was done in 7 of the 8 studies.

Scores between treatment groups were reported as not statistically significant in the 6 longer-term studies. Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with measures. The 2 short-term studies reported a statistically significant reduction in itching and redness (P<.05) in patients treated with the antihistamine (data not provided).

NSAIDs relieve itching but may sting when applied

A 2007 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs compared topical NSAIDs (ketorolac, diclofenac, aspirin, or steroid) with placebo for treating isolated allergic conjunctivitis in 712 children and adults.2 Primary outcomes were measured as subjective reductions in conjunctival injection and itching measured at 2 to 6 weeks using a 0-to-3 severity scale.

Topical NSAIDs produced significantly greater relief of conjunctival itching (4 trials, N=231; mean difference [MD]=-0.54; 95% CI, -0.84 to -0.24) and conjunctival injection (4 trials, N=208; MD=-0.51; 95% CI, -0.97 to -0.05). NSAIDs weren’t superior to placebo in treating other ocular symptoms of eyelid swelling, ocular burning, photophobia, or foreign body sensation, and they had a higher rate of stinging on application (odds ratio=4.0; 95% CI, 2.7-5.9).

Guideline recommends topical antihistamines or mast cell stabilizers

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2012 evidence-based guideline recommends treating allergic conjunctivitis with topical antihistamines (Level A-1 evidence, defined as important evidence supported by at least one RCT or a meta-analysis) and using topical mast cell stabilizers if the condition is recurrent.3

1. Owen CG, Shah A, Henshaw K, et al. Topical treatments for seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:451-456.

2. Swamy BN, Chilov M, McClellan K, et al. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in allergic conjunctivitis: meta-analysis of randomized trial data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:311–319.

3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Conjunctivitis Summary Benchmarks for Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. Available at: http://one.aao.org/summary-benchmark-detail/conjunctivitis-summary-benchmark--october-2012. Accessed October 18, 2013.

Topical antihistamines and topical mast cell stabilizers appear to reduce conjunctival injection and itching effectively. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also effective, but may sting on application (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both of these treatments relieve redness and itching

A 2004 systematic review of 40 RCTs (total N not provided) assessed the efficacy of topical treatment with mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines, comparing each with the other and placebo.1 Eleven trials that included 899 children and adults compared mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil, and lodoxamide tromethamine) with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 9 weeks.

Because of study heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used and showed that topical mast cell stabilizers relieved symptoms (ocular itching, burning, and lacrimation) 4.9 times more effectively than placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5-9.6). Possible publication bias was cited as a limitation.

In the same systematic review, 9 RCTs with 313 patients compared topical antihistamines (levocabastine, azelastine hydrochloride, emedastine, and antazoline phosphate) with placebo. Signs and symptoms (itching, redness, burning, and swelling) were graded using symptom severity scales. Follow-up ranged from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with these scores. Most individual studies, however, showed improvement in the cardinal symptom of itchiness.

Finally, 8 RCTs compared topical mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, lodoxamide, and nedocromil sodium) with levocabastine, a topical antihistamine. Two RCTs with 74 patients had follow-up periods of 15 minutes to 4 hours; the remaining 6 RCTs with 473 patients had follow-up periods of 14 days to 4 months. Subjective scoring of symptoms was done in 7 of the 8 studies.

Scores between treatment groups were reported as not statistically significant in the 6 longer-term studies. Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with measures. The 2 short-term studies reported a statistically significant reduction in itching and redness (P<.05) in patients treated with the antihistamine (data not provided).

NSAIDs relieve itching but may sting when applied

A 2007 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs compared topical NSAIDs (ketorolac, diclofenac, aspirin, or steroid) with placebo for treating isolated allergic conjunctivitis in 712 children and adults.2 Primary outcomes were measured as subjective reductions in conjunctival injection and itching measured at 2 to 6 weeks using a 0-to-3 severity scale.

Topical NSAIDs produced significantly greater relief of conjunctival itching (4 trials, N=231; mean difference [MD]=-0.54; 95% CI, -0.84 to -0.24) and conjunctival injection (4 trials, N=208; MD=-0.51; 95% CI, -0.97 to -0.05). NSAIDs weren’t superior to placebo in treating other ocular symptoms of eyelid swelling, ocular burning, photophobia, or foreign body sensation, and they had a higher rate of stinging on application (odds ratio=4.0; 95% CI, 2.7-5.9).

Guideline recommends topical antihistamines or mast cell stabilizers

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2012 evidence-based guideline recommends treating allergic conjunctivitis with topical antihistamines (Level A-1 evidence, defined as important evidence supported by at least one RCT or a meta-analysis) and using topical mast cell stabilizers if the condition is recurrent.3

Topical antihistamines and topical mast cell stabilizers appear to reduce conjunctival injection and itching effectively. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also effective, but may sting on application (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both of these treatments relieve redness and itching

A 2004 systematic review of 40 RCTs (total N not provided) assessed the efficacy of topical treatment with mast cell stabilizers and antihistamines, comparing each with the other and placebo.1 Eleven trials that included 899 children and adults compared mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil, and lodoxamide tromethamine) with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 9 weeks.

Because of study heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used and showed that topical mast cell stabilizers relieved symptoms (ocular itching, burning, and lacrimation) 4.9 times more effectively than placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5-9.6). Possible publication bias was cited as a limitation.

In the same systematic review, 9 RCTs with 313 patients compared topical antihistamines (levocabastine, azelastine hydrochloride, emedastine, and antazoline phosphate) with placebo. Signs and symptoms (itching, redness, burning, and swelling) were graded using symptom severity scales. Follow-up ranged from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with these scores. Most individual studies, however, showed improvement in the cardinal symptom of itchiness.

Finally, 8 RCTs compared topical mast cell stabilizers (sodium cromoglycate, lodoxamide, and nedocromil sodium) with levocabastine, a topical antihistamine. Two RCTs with 74 patients had follow-up periods of 15 minutes to 4 hours; the remaining 6 RCTs with 473 patients had follow-up periods of 14 days to 4 months. Subjective scoring of symptoms was done in 7 of the 8 studies.

Scores between treatment groups were reported as not statistically significant in the 6 longer-term studies. Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because most studies didn’t tabulate the mean scores and error associated with measures. The 2 short-term studies reported a statistically significant reduction in itching and redness (P<.05) in patients treated with the antihistamine (data not provided).

NSAIDs relieve itching but may sting when applied

A 2007 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs compared topical NSAIDs (ketorolac, diclofenac, aspirin, or steroid) with placebo for treating isolated allergic conjunctivitis in 712 children and adults.2 Primary outcomes were measured as subjective reductions in conjunctival injection and itching measured at 2 to 6 weeks using a 0-to-3 severity scale.

Topical NSAIDs produced significantly greater relief of conjunctival itching (4 trials, N=231; mean difference [MD]=-0.54; 95% CI, -0.84 to -0.24) and conjunctival injection (4 trials, N=208; MD=-0.51; 95% CI, -0.97 to -0.05). NSAIDs weren’t superior to placebo in treating other ocular symptoms of eyelid swelling, ocular burning, photophobia, or foreign body sensation, and they had a higher rate of stinging on application (odds ratio=4.0; 95% CI, 2.7-5.9).

Guideline recommends topical antihistamines or mast cell stabilizers

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2012 evidence-based guideline recommends treating allergic conjunctivitis with topical antihistamines (Level A-1 evidence, defined as important evidence supported by at least one RCT or a meta-analysis) and using topical mast cell stabilizers if the condition is recurrent.3

1. Owen CG, Shah A, Henshaw K, et al. Topical treatments for seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:451-456.

2. Swamy BN, Chilov M, McClellan K, et al. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in allergic conjunctivitis: meta-analysis of randomized trial data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:311–319.

3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Conjunctivitis Summary Benchmarks for Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. Available at: http://one.aao.org/summary-benchmark-detail/conjunctivitis-summary-benchmark--october-2012. Accessed October 18, 2013.

1. Owen CG, Shah A, Henshaw K, et al. Topical treatments for seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:451-456.

2. Swamy BN, Chilov M, McClellan K, et al. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in allergic conjunctivitis: meta-analysis of randomized trial data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:311–319.

3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Conjunctivitis Summary Benchmarks for Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. Available at: http://one.aao.org/summary-benchmark-detail/conjunctivitis-summary-benchmark--october-2012. Accessed October 18, 2013.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Is nonoperative therapy as effective as surgery for meniscal injuries?

Yes. There is no significant difference in symptom or functional improvement between adult patients with symptomatic meniscal injury who are treated with operative vs nonoperative therapy (strength of recommendation: A, consistent randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both approaches resulted in function and pain improvement

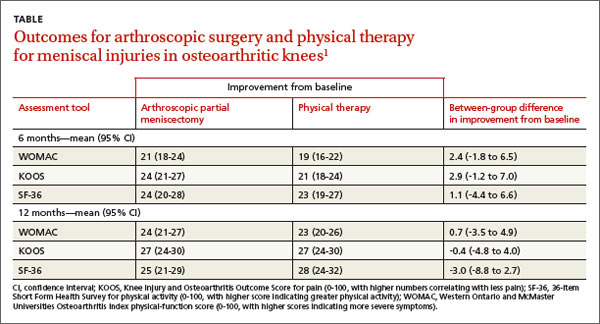

A 2013 multicenter RCT evaluated 351 adults, 45 years and older, with a meniscal tear and mild to moderate osteoarthritis confirmed by imaging, for functional improvement by physical therapy alone compared with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and physical therapy.1

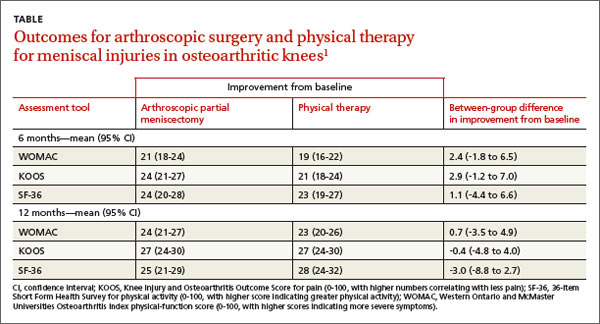

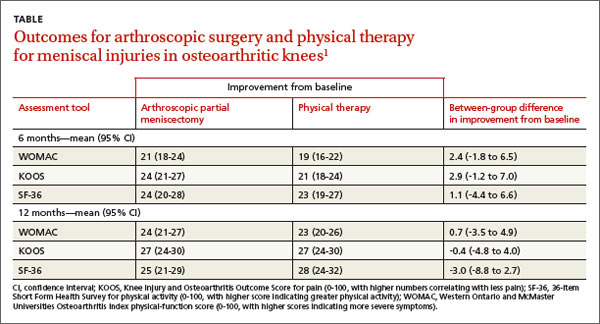

At the beginning of the study and 6 and 12 months after treatment, researchers assessed symptoms using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index physical-function score (0-100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) for pain (0-100, with higher numbers correlating with less pain), and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) for physical activity (0-100, with higher scores indicating greater physical activity).

Modified intention to treat analysis showed no significant difference in function and pain improvement at 6 and 12 months between patients with meniscal injury who underwent arthroscopic repair and physical therapy and patients who underwent physical therapy alone (TABLE1). A limitation of the study was the crossover of 30% of patients from the nonoperative group to the operative group.

No differences found in Tx outcomes for nontraumatic tears

A 2007 prospective RCT evaluated 90 adults ages 45 to 64 with nontraumatic meniscal tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging for improvement in knee pain and function with arthroscopic treatment and supervised exercise (AE) or supervised exercise (E) alone.2 Knee pain and function were assessed before intervention, after 8 weeks, and after 6 months of treatment using 3 surveys: the KOOS, the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale (LKSS; 0-100, with higher scores correlating with good knee function), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for knee pain (0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating maximum pain).

The KOOS revealed that at 8 weeks and 6 months both groups had significant improvement from the initial evaluation in all subscale scores. In the AE group, the 8-week pain score increased from a baseline of 56 to 89 (P<.001) and remained at 89 at 6 months (P<.001). For the E group, the 8-week pain score improved from a baseline of 62 to 86 (P<.001) and continued at 86 after 6 months (P<.001).

The LKSS score for both groups showed significant improvement from baseline at 8 weeks: 34% of the AE group and 42% of the E group scored higher than 91 (P<.001).

VAS scores showed a significant decrease in pain at 8 weeks for both the AE and E groups: beginning median value for both groups was 5.5 and decreased to 1.0 at 8 weeks and 6 months (P<.001).

The authors concluded that both groups improved significantly from initial evaluation regardless of treatment method and that no statistically significant difference existed between treatment results.

1. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1675-1684.

2. Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, et al. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:393-401.

Yes. There is no significant difference in symptom or functional improvement between adult patients with symptomatic meniscal injury who are treated with operative vs nonoperative therapy (strength of recommendation: A, consistent randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both approaches resulted in function and pain improvement

A 2013 multicenter RCT evaluated 351 adults, 45 years and older, with a meniscal tear and mild to moderate osteoarthritis confirmed by imaging, for functional improvement by physical therapy alone compared with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and physical therapy.1

At the beginning of the study and 6 and 12 months after treatment, researchers assessed symptoms using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index physical-function score (0-100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) for pain (0-100, with higher numbers correlating with less pain), and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) for physical activity (0-100, with higher scores indicating greater physical activity).

Modified intention to treat analysis showed no significant difference in function and pain improvement at 6 and 12 months between patients with meniscal injury who underwent arthroscopic repair and physical therapy and patients who underwent physical therapy alone (TABLE1). A limitation of the study was the crossover of 30% of patients from the nonoperative group to the operative group.

No differences found in Tx outcomes for nontraumatic tears

A 2007 prospective RCT evaluated 90 adults ages 45 to 64 with nontraumatic meniscal tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging for improvement in knee pain and function with arthroscopic treatment and supervised exercise (AE) or supervised exercise (E) alone.2 Knee pain and function were assessed before intervention, after 8 weeks, and after 6 months of treatment using 3 surveys: the KOOS, the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale (LKSS; 0-100, with higher scores correlating with good knee function), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for knee pain (0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating maximum pain).

The KOOS revealed that at 8 weeks and 6 months both groups had significant improvement from the initial evaluation in all subscale scores. In the AE group, the 8-week pain score increased from a baseline of 56 to 89 (P<.001) and remained at 89 at 6 months (P<.001). For the E group, the 8-week pain score improved from a baseline of 62 to 86 (P<.001) and continued at 86 after 6 months (P<.001).

The LKSS score for both groups showed significant improvement from baseline at 8 weeks: 34% of the AE group and 42% of the E group scored higher than 91 (P<.001).

VAS scores showed a significant decrease in pain at 8 weeks for both the AE and E groups: beginning median value for both groups was 5.5 and decreased to 1.0 at 8 weeks and 6 months (P<.001).

The authors concluded that both groups improved significantly from initial evaluation regardless of treatment method and that no statistically significant difference existed between treatment results.

Yes. There is no significant difference in symptom or functional improvement between adult patients with symptomatic meniscal injury who are treated with operative vs nonoperative therapy (strength of recommendation: A, consistent randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Both approaches resulted in function and pain improvement

A 2013 multicenter RCT evaluated 351 adults, 45 years and older, with a meniscal tear and mild to moderate osteoarthritis confirmed by imaging, for functional improvement by physical therapy alone compared with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and physical therapy.1

At the beginning of the study and 6 and 12 months after treatment, researchers assessed symptoms using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index physical-function score (0-100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) for pain (0-100, with higher numbers correlating with less pain), and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) for physical activity (0-100, with higher scores indicating greater physical activity).

Modified intention to treat analysis showed no significant difference in function and pain improvement at 6 and 12 months between patients with meniscal injury who underwent arthroscopic repair and physical therapy and patients who underwent physical therapy alone (TABLE1). A limitation of the study was the crossover of 30% of patients from the nonoperative group to the operative group.

No differences found in Tx outcomes for nontraumatic tears

A 2007 prospective RCT evaluated 90 adults ages 45 to 64 with nontraumatic meniscal tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging for improvement in knee pain and function with arthroscopic treatment and supervised exercise (AE) or supervised exercise (E) alone.2 Knee pain and function were assessed before intervention, after 8 weeks, and after 6 months of treatment using 3 surveys: the KOOS, the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale (LKSS; 0-100, with higher scores correlating with good knee function), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for knee pain (0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating maximum pain).

The KOOS revealed that at 8 weeks and 6 months both groups had significant improvement from the initial evaluation in all subscale scores. In the AE group, the 8-week pain score increased from a baseline of 56 to 89 (P<.001) and remained at 89 at 6 months (P<.001). For the E group, the 8-week pain score improved from a baseline of 62 to 86 (P<.001) and continued at 86 after 6 months (P<.001).

The LKSS score for both groups showed significant improvement from baseline at 8 weeks: 34% of the AE group and 42% of the E group scored higher than 91 (P<.001).

VAS scores showed a significant decrease in pain at 8 weeks for both the AE and E groups: beginning median value for both groups was 5.5 and decreased to 1.0 at 8 weeks and 6 months (P<.001).

The authors concluded that both groups improved significantly from initial evaluation regardless of treatment method and that no statistically significant difference existed between treatment results.

1. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1675-1684.

2. Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, et al. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:393-401.

1. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1675-1684.

2. Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, et al. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:393-401.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network