User login

Abdominal distention and pain

Given the patient's symptomatology, laboratory studies, and the histopathology and immunophenotyping of the polypoid lesions in the transverse colon, this patient is diagnosed with advanced mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). The gastroenterologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team forms to guide the patient through potential next steps and treatment options.

MCL is a type of B-cell neoplasm that, with advancements in the understanding of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the past 30 years, has been defined as its own clinicopathologic entity by the Revised European-American Lymphoma and World Health Organization classifications. Up to 10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas are MCL. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. One of the most frequent areas for extra-nodal MCL presentation is the gastrointestinal tract. Men are more likely to present with MCL than are women by a ratio of 3:1. Median age at presentation is 67 years.

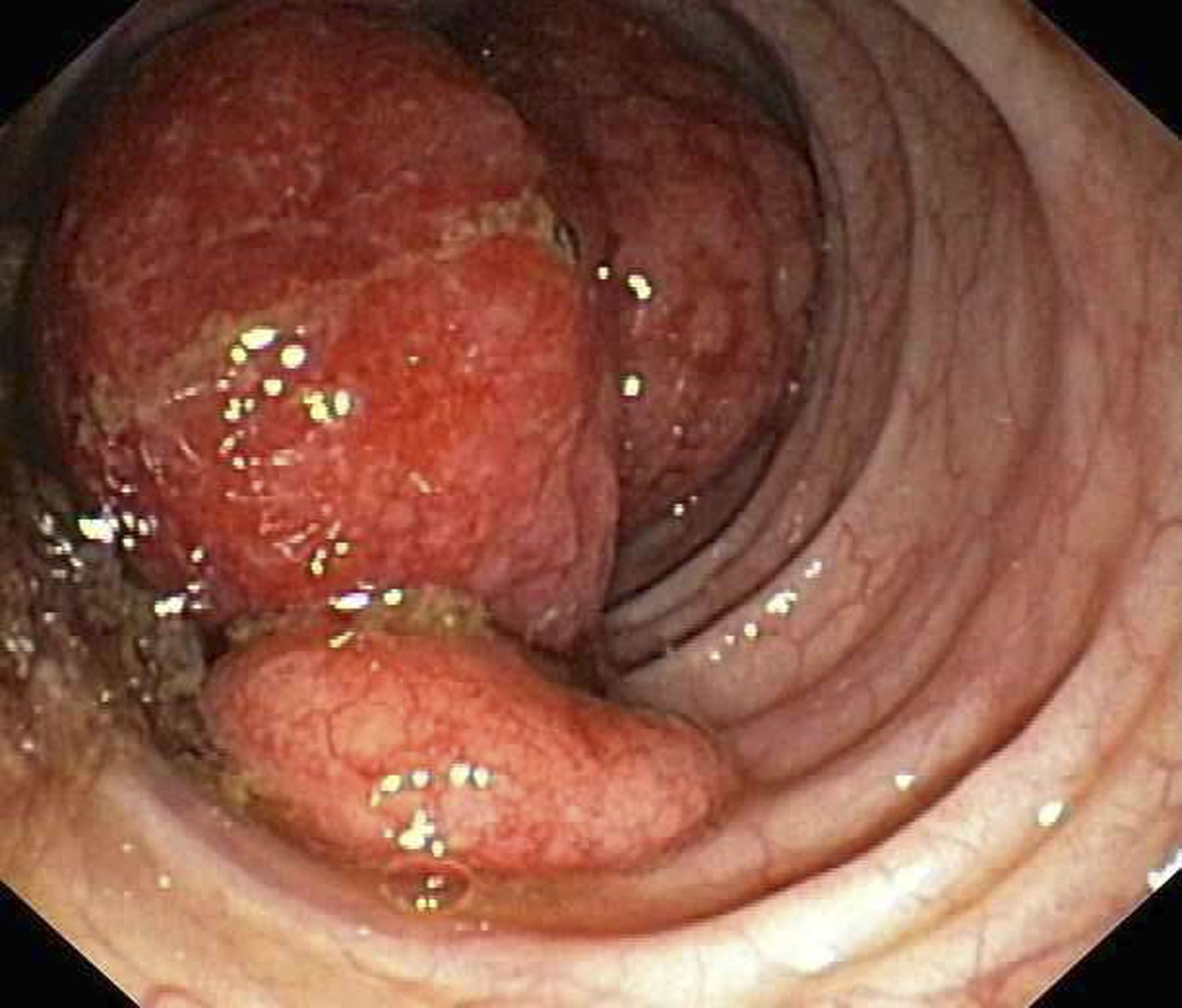

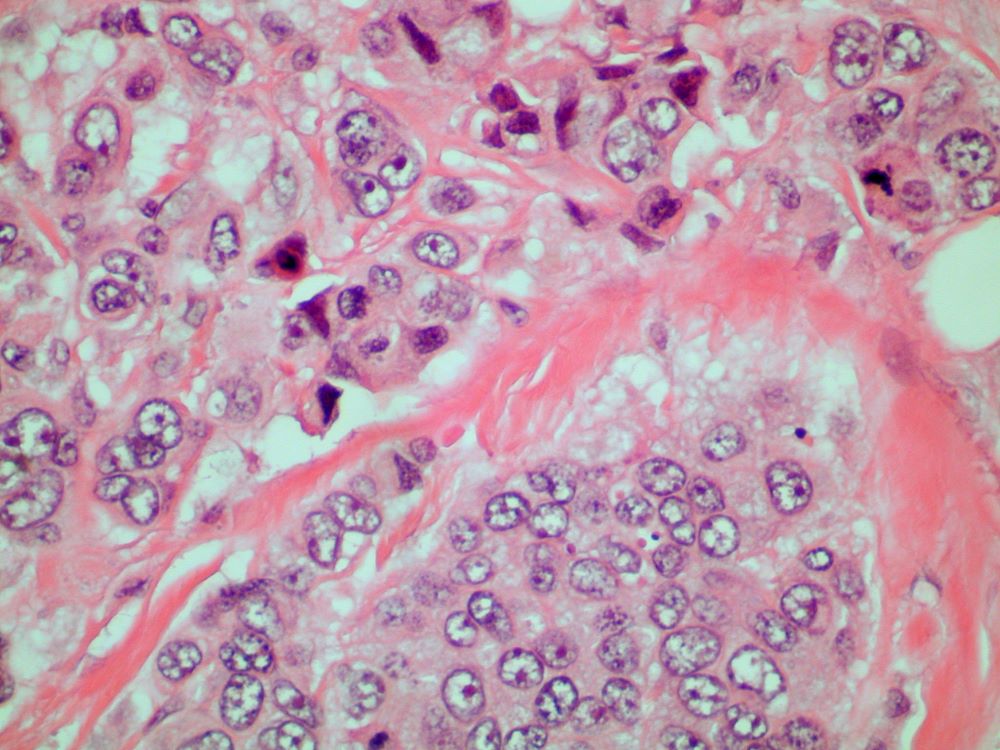

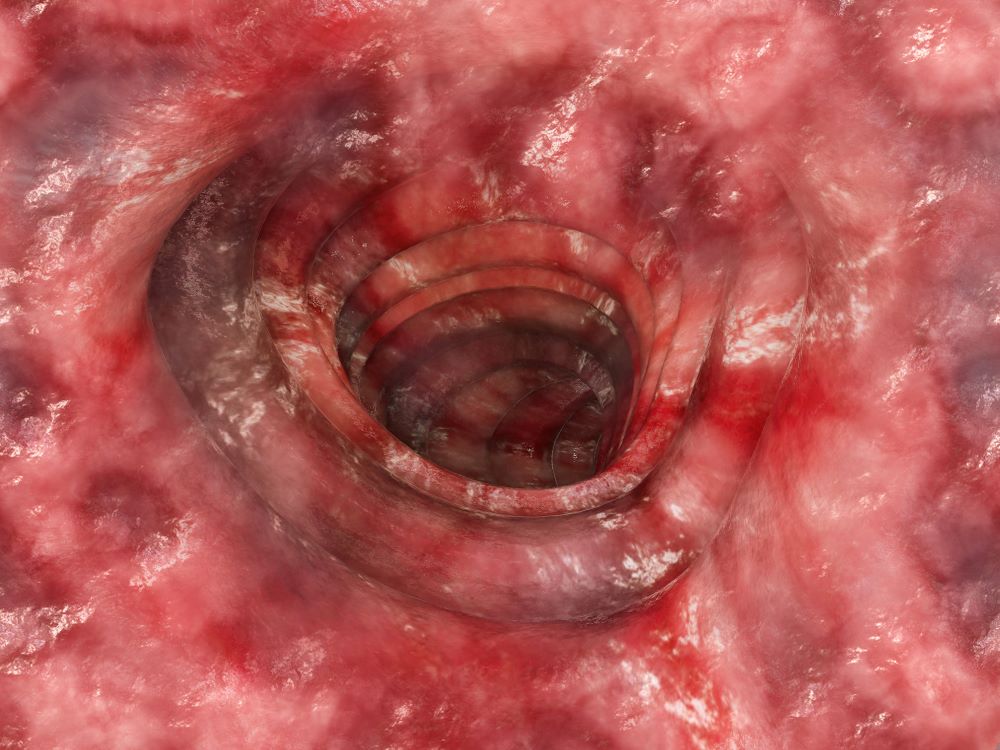

Diagnosing MCL is a multipronged approach. Physical examination may reveal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveals monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin (Ig), IgM, or IgD, which are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen–positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate/biopsy are used more for staging than for diagnosis. Blood studies, including anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with up to 40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and a negative Coombs test, also help diagnose MCL. Gastrointestinal involvement of MCL typically presents as lymphoid polyposis on colonoscopy imaging and can appear in the colon, ileum, stomach, and duodenum.

Pathogenesis of MCL involves disordered lymphoproliferation in a subset of naive pregerminal center cells in primary follicles or in the mantle region of secondary follicles. Most cases are linked with translocation of chromosome 14 and 11, which induces overexpression of protein cyclin D1. Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, human herpes virus 6), environmental factors, and primary and secondary immunodeficiency are also associated with the development of NHL.

Patient education should include detailed information about clinical trials, available treatment options and associated adverse events, as well as psychosocial and nutrition counseling.

Chemoimmunotherapy is standard initial treatment for MCL, but relapse is expected. Chemotherapy-free regimens with biologic targets, when used in second-line treatment, have increasingly become an important first-line treatment given their efficacy in the relapsed/refractory setting. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is also a second-line treatment option. In patients with MCL and a TP53 mutation, clinical trial participation is encouraged because of poor prognosis.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's symptomatology, laboratory studies, and the histopathology and immunophenotyping of the polypoid lesions in the transverse colon, this patient is diagnosed with advanced mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). The gastroenterologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team forms to guide the patient through potential next steps and treatment options.

MCL is a type of B-cell neoplasm that, with advancements in the understanding of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the past 30 years, has been defined as its own clinicopathologic entity by the Revised European-American Lymphoma and World Health Organization classifications. Up to 10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas are MCL. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. One of the most frequent areas for extra-nodal MCL presentation is the gastrointestinal tract. Men are more likely to present with MCL than are women by a ratio of 3:1. Median age at presentation is 67 years.

Diagnosing MCL is a multipronged approach. Physical examination may reveal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveals monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin (Ig), IgM, or IgD, which are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen–positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate/biopsy are used more for staging than for diagnosis. Blood studies, including anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with up to 40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and a negative Coombs test, also help diagnose MCL. Gastrointestinal involvement of MCL typically presents as lymphoid polyposis on colonoscopy imaging and can appear in the colon, ileum, stomach, and duodenum.

Pathogenesis of MCL involves disordered lymphoproliferation in a subset of naive pregerminal center cells in primary follicles or in the mantle region of secondary follicles. Most cases are linked with translocation of chromosome 14 and 11, which induces overexpression of protein cyclin D1. Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, human herpes virus 6), environmental factors, and primary and secondary immunodeficiency are also associated with the development of NHL.

Patient education should include detailed information about clinical trials, available treatment options and associated adverse events, as well as psychosocial and nutrition counseling.

Chemoimmunotherapy is standard initial treatment for MCL, but relapse is expected. Chemotherapy-free regimens with biologic targets, when used in second-line treatment, have increasingly become an important first-line treatment given their efficacy in the relapsed/refractory setting. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is also a second-line treatment option. In patients with MCL and a TP53 mutation, clinical trial participation is encouraged because of poor prognosis.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's symptomatology, laboratory studies, and the histopathology and immunophenotyping of the polypoid lesions in the transverse colon, this patient is diagnosed with advanced mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). The gastroenterologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team forms to guide the patient through potential next steps and treatment options.

MCL is a type of B-cell neoplasm that, with advancements in the understanding of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the past 30 years, has been defined as its own clinicopathologic entity by the Revised European-American Lymphoma and World Health Organization classifications. Up to 10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas are MCL. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. One of the most frequent areas for extra-nodal MCL presentation is the gastrointestinal tract. Men are more likely to present with MCL than are women by a ratio of 3:1. Median age at presentation is 67 years.

Diagnosing MCL is a multipronged approach. Physical examination may reveal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveals monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin (Ig), IgM, or IgD, which are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen–positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate/biopsy are used more for staging than for diagnosis. Blood studies, including anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with up to 40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and a negative Coombs test, also help diagnose MCL. Gastrointestinal involvement of MCL typically presents as lymphoid polyposis on colonoscopy imaging and can appear in the colon, ileum, stomach, and duodenum.

Pathogenesis of MCL involves disordered lymphoproliferation in a subset of naive pregerminal center cells in primary follicles or in the mantle region of secondary follicles. Most cases are linked with translocation of chromosome 14 and 11, which induces overexpression of protein cyclin D1. Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, human herpes virus 6), environmental factors, and primary and secondary immunodeficiency are also associated with the development of NHL.

Patient education should include detailed information about clinical trials, available treatment options and associated adverse events, as well as psychosocial and nutrition counseling.

Chemoimmunotherapy is standard initial treatment for MCL, but relapse is expected. Chemotherapy-free regimens with biologic targets, when used in second-line treatment, have increasingly become an important first-line treatment given their efficacy in the relapsed/refractory setting. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is also a second-line treatment option. In patients with MCL and a TP53 mutation, clinical trial participation is encouraged because of poor prognosis.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 60-year-old man presents to his primary care physician with weight loss, constipation, and abdominal distention and pain as well as fatigue and night sweats that have lasted for several months. The physician orders a complete blood count with differential and an ultrasound of the abdomen. Lab studies reveal anemia and cytopenias; ultrasound reveals hepatosplenomegaly and abdominal lymphadenopathy. The physician refers the patient to gastroenterology; he undergoes a colonoscopy. Multiple polypoid lesions are found throughout the transverse colon. Immunophenotyping shows CD5 and CD20 expression but a lack of CD23 and CD10 expression; cyclin D1 is overexpressed. Additional blood studies show lymphocytosis > 4000/μL, elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, abnormal liver function tests, and a negative result on Coombs test.

Blurred vision and shortness of breath

Given her symptomatology, imaging, and laboratory study results, this patient is diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and brain metastases. The pulmonologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team, which includes oncology and radiology, forms to guide the patient through staging and treatment options.

SCLC is a neuroendocrine carcinoma, which is an aggressive form of lung cancer associated with rapid growth and early spread to distant sites and frequent association with distinct paraneoplastic syndromes. Approximately 13% of newly diagnosed lung cancers are SCLC. Clinical presentation is often advanced stage and includes shortness of breath, cough, bone pain, weight loss, fatigue, and neurologic dysfunction, including blurred vision, dizziness, and headaches that disturb sleep. Typically, symptom onset is quick, with the duration of symptoms lasting between 8 and 12 weeks before presentation.

According to CHEST guidelines, when clinical and radiographic findings suggest SCLC, diagnosis should be confirmed using the least invasive technique possible on the basis of presentation. Fine-needle aspiration or biopsy is recommended to assess a suspicious singular extrathoracic site for metastasis. If that approach is not feasible, guidelines recommend diagnosing the primary lung lesion. If there is an accessible pleural effusion, ultrasound-guided thoracentesis is recommended for diagnosis. If the result of pleural fluid cytology is negative, pleural biopsy using image-guided pleural biopsy, medical, or surgical thoracoscopy is recommended next. Common mutations associated with SCLC include RB1 and TP53 gene mutations.

Nearly all patients with SCLC (98%) have a history of tobacco use. Uranium or radon exposure has also been linked to SCLC. Pathogenesis occurs in the peribronchial region of the respiratory system and moves into the bronchial submucosa. Widespread metastases can appear early during SCLC and generally affect mediastinal lymph nodes, bones, brain, liver, and adrenal glands.

Patient education should include information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events. Smoking cessation is encouraged for current smokers with SCLC.

For patients with extensive-stage metastatic SCLC, the new standard of care combines the immunotherapy atezolizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, with chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide). When used in the first-line setting, this combination has been shown to improve survival outcomes. Of course, clinical trials are ongoing; other treatments in development include additional classes of immunotherapies (programmed cell death protein1 [PD-1] inhibitor antibody, anti-PD1 antibody, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor antibody) and targeted therapies (delta-like protein 3 antibody-drug conjugate).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given her symptomatology, imaging, and laboratory study results, this patient is diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and brain metastases. The pulmonologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team, which includes oncology and radiology, forms to guide the patient through staging and treatment options.

SCLC is a neuroendocrine carcinoma, which is an aggressive form of lung cancer associated with rapid growth and early spread to distant sites and frequent association with distinct paraneoplastic syndromes. Approximately 13% of newly diagnosed lung cancers are SCLC. Clinical presentation is often advanced stage and includes shortness of breath, cough, bone pain, weight loss, fatigue, and neurologic dysfunction, including blurred vision, dizziness, and headaches that disturb sleep. Typically, symptom onset is quick, with the duration of symptoms lasting between 8 and 12 weeks before presentation.

According to CHEST guidelines, when clinical and radiographic findings suggest SCLC, diagnosis should be confirmed using the least invasive technique possible on the basis of presentation. Fine-needle aspiration or biopsy is recommended to assess a suspicious singular extrathoracic site for metastasis. If that approach is not feasible, guidelines recommend diagnosing the primary lung lesion. If there is an accessible pleural effusion, ultrasound-guided thoracentesis is recommended for diagnosis. If the result of pleural fluid cytology is negative, pleural biopsy using image-guided pleural biopsy, medical, or surgical thoracoscopy is recommended next. Common mutations associated with SCLC include RB1 and TP53 gene mutations.

Nearly all patients with SCLC (98%) have a history of tobacco use. Uranium or radon exposure has also been linked to SCLC. Pathogenesis occurs in the peribronchial region of the respiratory system and moves into the bronchial submucosa. Widespread metastases can appear early during SCLC and generally affect mediastinal lymph nodes, bones, brain, liver, and adrenal glands.

Patient education should include information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events. Smoking cessation is encouraged for current smokers with SCLC.

For patients with extensive-stage metastatic SCLC, the new standard of care combines the immunotherapy atezolizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, with chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide). When used in the first-line setting, this combination has been shown to improve survival outcomes. Of course, clinical trials are ongoing; other treatments in development include additional classes of immunotherapies (programmed cell death protein1 [PD-1] inhibitor antibody, anti-PD1 antibody, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor antibody) and targeted therapies (delta-like protein 3 antibody-drug conjugate).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given her symptomatology, imaging, and laboratory study results, this patient is diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and brain metastases. The pulmonologist shares the findings with the patient, and over the next several days, a multidisciplinary team, which includes oncology and radiology, forms to guide the patient through staging and treatment options.

SCLC is a neuroendocrine carcinoma, which is an aggressive form of lung cancer associated with rapid growth and early spread to distant sites and frequent association with distinct paraneoplastic syndromes. Approximately 13% of newly diagnosed lung cancers are SCLC. Clinical presentation is often advanced stage and includes shortness of breath, cough, bone pain, weight loss, fatigue, and neurologic dysfunction, including blurred vision, dizziness, and headaches that disturb sleep. Typically, symptom onset is quick, with the duration of symptoms lasting between 8 and 12 weeks before presentation.

According to CHEST guidelines, when clinical and radiographic findings suggest SCLC, diagnosis should be confirmed using the least invasive technique possible on the basis of presentation. Fine-needle aspiration or biopsy is recommended to assess a suspicious singular extrathoracic site for metastasis. If that approach is not feasible, guidelines recommend diagnosing the primary lung lesion. If there is an accessible pleural effusion, ultrasound-guided thoracentesis is recommended for diagnosis. If the result of pleural fluid cytology is negative, pleural biopsy using image-guided pleural biopsy, medical, or surgical thoracoscopy is recommended next. Common mutations associated with SCLC include RB1 and TP53 gene mutations.

Nearly all patients with SCLC (98%) have a history of tobacco use. Uranium or radon exposure has also been linked to SCLC. Pathogenesis occurs in the peribronchial region of the respiratory system and moves into the bronchial submucosa. Widespread metastases can appear early during SCLC and generally affect mediastinal lymph nodes, bones, brain, liver, and adrenal glands.

Patient education should include information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events. Smoking cessation is encouraged for current smokers with SCLC.

For patients with extensive-stage metastatic SCLC, the new standard of care combines the immunotherapy atezolizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, with chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide). When used in the first-line setting, this combination has been shown to improve survival outcomes. Of course, clinical trials are ongoing; other treatments in development include additional classes of immunotherapies (programmed cell death protein1 [PD-1] inhibitor antibody, anti-PD1 antibody, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor antibody) and targeted therapies (delta-like protein 3 antibody-drug conjugate).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 66-year-old woman who is a former smoker presents to her primary care physician with a recent history of dizziness, blurred vision, shortness of breath, and headaches that wake her up in the morning. The patient reports significant weight loss, persistent cough, and fatigue over the past 2 months. The patient owns and runs a local French bakery and reports difficulty keeping up with routine productivity. In addition, she has had to skip several days of work lately and rely more on her staff, which increases business costs, because of the severity of her symptoms. Her height is 5 ft 6 in and weight is 176 lb; her BMI is 28.4.

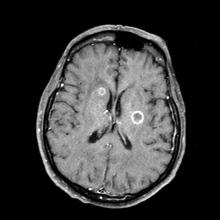

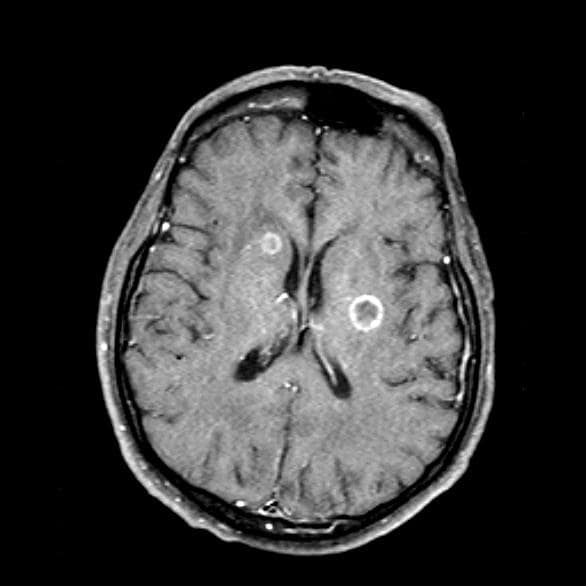

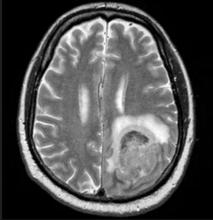

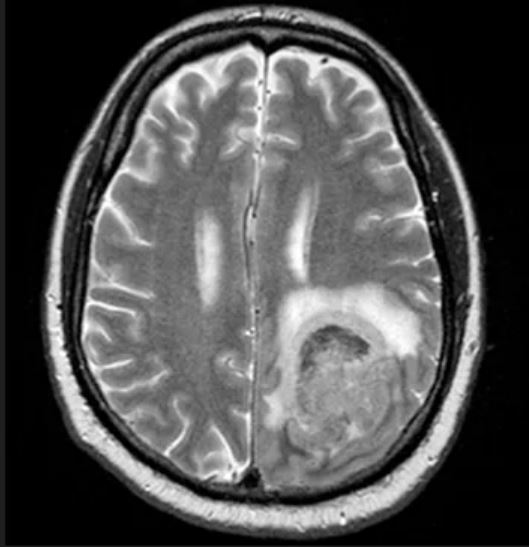

On physical examination, her physician detects enlarged axillary lymph nodes and dullness to percussion and decreased breath sounds in the central right lung. Fundoscopy reveals increased intracranial pressure, and a neurologic exam shows abnormalities in cerebellar function. The physician orders a CT from the base of the skull to mid-thigh as well as a brain MRI. Results show tumors in the right ipsilateral hemithorax and contralateral lung and metastases in the brain. The patient is referred to pulmonology, where she undergoes a fine needle aspiration of the suspected axillary lymph nodes; cytology reveals metastatic cancer. Thereafter, the patient undergoes a bronchoscopy and transbronchial biopsy. Comprehensive genomic profiling of the tumor sample reveals TP53 and RB1 gene mutations.

Forgetfulness and mood fluctuations

This patient's symptoms go beyond just memory problems: She has difficulty with daily tasks, shows behavioral changes, and has significant communication difficulties — symptoms not found in mild cognitive impairment. While the patient has some behavioral changes, she does not exhibit the pronounced personality changes typical of frontotemporal dementia. Finally, the patient's cognitive decline is gradual and consistent without the stepwise progression typical of vascular dementia. Given the comprehensive presentation of the patient's symptoms and the results of her clinical investigations, middle-stage Alzheimer's disease is the most fitting diagnosis.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that affects memory, behavior, and cognitive skills. This condition causes the degeneration and death of brain cells, leading to various cognitive issues. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and accounts for 60%-80% of dementia cases. Although the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to result from genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Alzheimer's disease progresses through stages — mild (early stage), moderate (middle stage), and severe (late stage) — and each stage has different signs and symptoms.

Alzheimer's disease is commonly observed in individuals 65 years or older, as age is the most significant risk factor. Another risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is family history; individuals who have parents or siblings with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to develop the disease. The risk increases with the number of family members diagnosed with the disease. Genetics also contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease. Genes for developing Alzheimer's disease have been classified as deterministic and risk genes, which imply that they can cause the disease or increase the risk of developing it; however, the deterministic gene, which almost guarantees the occurrence of Alzheimer's, is rare and is found in less than 1% of cases. Experiencing a head injury is also a possible risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.

Accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease requires a thorough history and physical examination. Gathering information from the patient's family and caregivers is important because some patients may not be aware of their condition. It is common for Alzheimer's disease patients to experience "sundowning," which causes confusion, agitation, and behavioral issues in the evening. A comprehensive physical examination, including a detailed neurologic and mental status exam, is necessary to determine the stage of the disease and rule out other conditions. Typically, the neurologic exam of Alzheimer's disease patients is normal.

Volumetric MRI is a recent technique that allows precise measurement of changes in brain volume. In Alzheimer's disease, shrinkage in the medial temporal lobe is visible through volumetric MRI. However, hippocampal atrophy is also a normal part of age-related memory decline, which raises doubts about the appropriateness of using volumetric MRI for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. The full potential of volumetric MRI in aiding the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is yet to be fully established.

Alzheimer's disease has no known cure, and treatment options are limited to addressing symptoms. Currently, three types of drugs are approved for treating the moderate or severe stages of the disease: cholinesterase inhibitors, partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, and amyloid-directed antibodies. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase acetylcholine levels, a chemical crucial for cognitive functions such as memory and learning. NMDA antagonists (memantine) blocks NMDA receptors whose overactivation is implicated in Alzheimer's disease and related to synaptic dysfunction. Antiamyloid monoclonal antibodies bind to and promote the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides, thereby reducing amyloid plaques in the brain, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms go beyond just memory problems: She has difficulty with daily tasks, shows behavioral changes, and has significant communication difficulties — symptoms not found in mild cognitive impairment. While the patient has some behavioral changes, she does not exhibit the pronounced personality changes typical of frontotemporal dementia. Finally, the patient's cognitive decline is gradual and consistent without the stepwise progression typical of vascular dementia. Given the comprehensive presentation of the patient's symptoms and the results of her clinical investigations, middle-stage Alzheimer's disease is the most fitting diagnosis.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that affects memory, behavior, and cognitive skills. This condition causes the degeneration and death of brain cells, leading to various cognitive issues. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and accounts for 60%-80% of dementia cases. Although the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to result from genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Alzheimer's disease progresses through stages — mild (early stage), moderate (middle stage), and severe (late stage) — and each stage has different signs and symptoms.

Alzheimer's disease is commonly observed in individuals 65 years or older, as age is the most significant risk factor. Another risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is family history; individuals who have parents or siblings with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to develop the disease. The risk increases with the number of family members diagnosed with the disease. Genetics also contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease. Genes for developing Alzheimer's disease have been classified as deterministic and risk genes, which imply that they can cause the disease or increase the risk of developing it; however, the deterministic gene, which almost guarantees the occurrence of Alzheimer's, is rare and is found in less than 1% of cases. Experiencing a head injury is also a possible risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.

Accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease requires a thorough history and physical examination. Gathering information from the patient's family and caregivers is important because some patients may not be aware of their condition. It is common for Alzheimer's disease patients to experience "sundowning," which causes confusion, agitation, and behavioral issues in the evening. A comprehensive physical examination, including a detailed neurologic and mental status exam, is necessary to determine the stage of the disease and rule out other conditions. Typically, the neurologic exam of Alzheimer's disease patients is normal.

Volumetric MRI is a recent technique that allows precise measurement of changes in brain volume. In Alzheimer's disease, shrinkage in the medial temporal lobe is visible through volumetric MRI. However, hippocampal atrophy is also a normal part of age-related memory decline, which raises doubts about the appropriateness of using volumetric MRI for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. The full potential of volumetric MRI in aiding the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is yet to be fully established.

Alzheimer's disease has no known cure, and treatment options are limited to addressing symptoms. Currently, three types of drugs are approved for treating the moderate or severe stages of the disease: cholinesterase inhibitors, partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, and amyloid-directed antibodies. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase acetylcholine levels, a chemical crucial for cognitive functions such as memory and learning. NMDA antagonists (memantine) blocks NMDA receptors whose overactivation is implicated in Alzheimer's disease and related to synaptic dysfunction. Antiamyloid monoclonal antibodies bind to and promote the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides, thereby reducing amyloid plaques in the brain, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms go beyond just memory problems: She has difficulty with daily tasks, shows behavioral changes, and has significant communication difficulties — symptoms not found in mild cognitive impairment. While the patient has some behavioral changes, she does not exhibit the pronounced personality changes typical of frontotemporal dementia. Finally, the patient's cognitive decline is gradual and consistent without the stepwise progression typical of vascular dementia. Given the comprehensive presentation of the patient's symptoms and the results of her clinical investigations, middle-stage Alzheimer's disease is the most fitting diagnosis.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that affects memory, behavior, and cognitive skills. This condition causes the degeneration and death of brain cells, leading to various cognitive issues. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and accounts for 60%-80% of dementia cases. Although the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to result from genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Alzheimer's disease progresses through stages — mild (early stage), moderate (middle stage), and severe (late stage) — and each stage has different signs and symptoms.

Alzheimer's disease is commonly observed in individuals 65 years or older, as age is the most significant risk factor. Another risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is family history; individuals who have parents or siblings with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to develop the disease. The risk increases with the number of family members diagnosed with the disease. Genetics also contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease. Genes for developing Alzheimer's disease have been classified as deterministic and risk genes, which imply that they can cause the disease or increase the risk of developing it; however, the deterministic gene, which almost guarantees the occurrence of Alzheimer's, is rare and is found in less than 1% of cases. Experiencing a head injury is also a possible risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.

Accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease requires a thorough history and physical examination. Gathering information from the patient's family and caregivers is important because some patients may not be aware of their condition. It is common for Alzheimer's disease patients to experience "sundowning," which causes confusion, agitation, and behavioral issues in the evening. A comprehensive physical examination, including a detailed neurologic and mental status exam, is necessary to determine the stage of the disease and rule out other conditions. Typically, the neurologic exam of Alzheimer's disease patients is normal.

Volumetric MRI is a recent technique that allows precise measurement of changes in brain volume. In Alzheimer's disease, shrinkage in the medial temporal lobe is visible through volumetric MRI. However, hippocampal atrophy is also a normal part of age-related memory decline, which raises doubts about the appropriateness of using volumetric MRI for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. The full potential of volumetric MRI in aiding the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is yet to be fully established.

Alzheimer's disease has no known cure, and treatment options are limited to addressing symptoms. Currently, three types of drugs are approved for treating the moderate or severe stages of the disease: cholinesterase inhibitors, partial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, and amyloid-directed antibodies. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase acetylcholine levels, a chemical crucial for cognitive functions such as memory and learning. NMDA antagonists (memantine) blocks NMDA receptors whose overactivation is implicated in Alzheimer's disease and related to synaptic dysfunction. Antiamyloid monoclonal antibodies bind to and promote the clearance of amyloid-beta peptides, thereby reducing amyloid plaques in the brain, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is a 72-year-old retired schoolteacher accompanied by her daughter. Over the past year, her family has become increasingly concerned about her forgetfulness, mood fluctuations, and challenges in performing daily activities. The patient often forgets her grandchildren's names and struggles to recall significant recent events. She frequently misplaces household items and has missed several appointments. During her consultation, she has difficulty finding the right words, often repeats herself, and seems to lose track of the conversation. Her daughter shared concerning incidents, such as the patient wearing heavy sweaters during hot summer days and falling victim to a phone scam, which was uncharacteristic of her previous discerning nature. Additionally, the patient has become more reclusive, avoiding the social gatherings she once loved. She occasionally exhibits signs of agitation, especially in the evening. She has also stopped cooking as a result of instances of forgetting to turn off the stove and has had challenges managing her finances, leading to unpaid bills. A thorough neurologic exam is performed and is normal. Coronal T1-weighted MRI reveals hippocampal atrophy, particularly on the right side.

Discomfort in right breast

Breast cancer is the most common tumor type and second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in women. Nearly 300,000 women (and 2800 men) will receive a new diagnosis of breast cancer in the United States in 2023. Despite improvements in treatment options, breast cancer still will lead to 43,700 deaths among women this year.

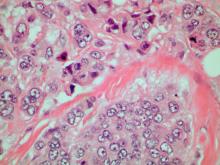

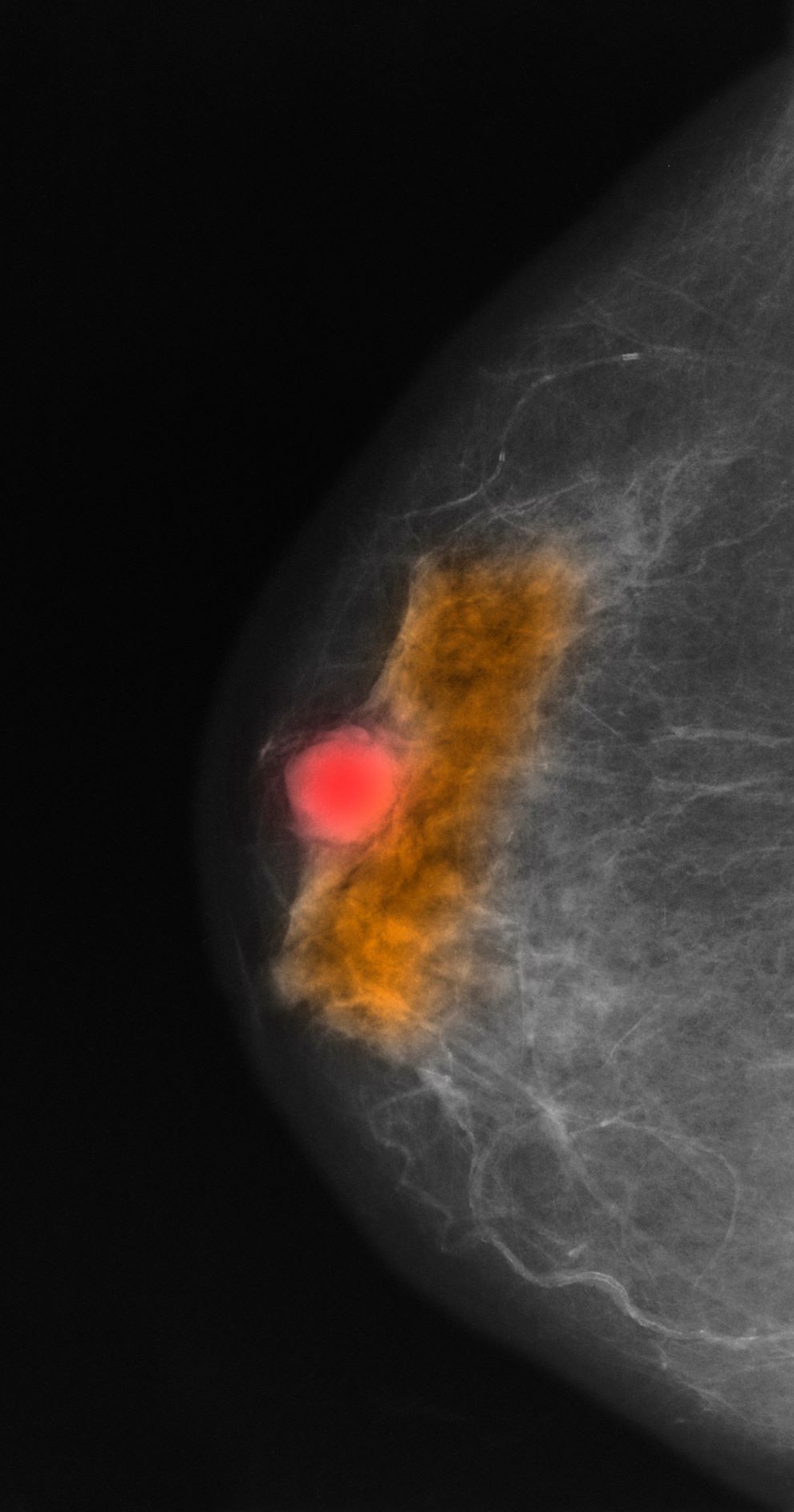

Breast tumors generally are either ductal or lobular in origin. Ductal carcinomas arise in the lining of the milk ducts and are the most commonly found tumor type in breast cancer. Almost 3 in 4 diagnosed breast cancers histologically are invasive ductal carcinomas, which have spread from the source into surrounding structures. It has no specific histologic indicators and is differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ by its having spread outside the duct. The presence of lymph node involvement in this patient also confirms invasive ductal carcinoma without metastatic spread. Invasive lobular carcinomas occur much less frequently and have a different histologic appearance of smaller cells that appear to be arranged in linear groups.

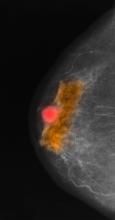

Mammography involves low-dose radiation and is used in diagnosis and is the most widely used screening technique for breast cancer. As a screening tool, mammography may detect lesions 1-2 years before they become palpable on breast self-examination. While the incidence of breast cancer in women has slowly increased over the past 20 years, mortality has decreased largely as a result of improved awareness and uptake of screening mammography. Current American Cancer Society guidelines recommend continued mammography screenings at least every other year after age 55 and continued for as long as a woman has a life expectancy > 10 years. Screening or diagnosis using MRI is usually reserved for individuals at high risk for breast cancer or a history of breast cancer before age 50.

For all newly diagnosed primary invasive breast cancers, biomarker testing for estrogen and progesterone receptor expression and HER2 expression are part of the standard workup recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to help guide treatment decisions. Biomarker testing showed that her tumor was ER+ and HER2-negative, the most common finding in breast cancer. The patient's history did not suggest a risk for BRCA or other familial cancer mutations, but molecular testing was done and was negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2. In postmenopausal women, ASCO and NCCN also recommend use of risk assessment tools, such as Oncotype DX, to determine whether chemotherapy will add benefit to systemic endocrine therapy. Postmenopausal patients with ER+/HER2-negative breast cancer, one to three positive nodes, and a score < 26 on the 21-gene Oncotype DX can safely forego cytotoxic chemotherapy and derive maximum survival benefit from hormonal therapy alone.

This patient was diagnosed with a primary tumor of approximately 25 mm, metastasis to two ipsilateral nodes, and no distant metastasis, or stage IIIA. Her risk recurrence score was 20, indicating that she could safely forego the rigors of cytotoxic chemotherapy. She underwent localized breast-conserving surgery and began adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (x 2 years) to be followed with an aromatase inhibitor (x 3 years).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Breast cancer is the most common tumor type and second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in women. Nearly 300,000 women (and 2800 men) will receive a new diagnosis of breast cancer in the United States in 2023. Despite improvements in treatment options, breast cancer still will lead to 43,700 deaths among women this year.

Breast tumors generally are either ductal or lobular in origin. Ductal carcinomas arise in the lining of the milk ducts and are the most commonly found tumor type in breast cancer. Almost 3 in 4 diagnosed breast cancers histologically are invasive ductal carcinomas, which have spread from the source into surrounding structures. It has no specific histologic indicators and is differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ by its having spread outside the duct. The presence of lymph node involvement in this patient also confirms invasive ductal carcinoma without metastatic spread. Invasive lobular carcinomas occur much less frequently and have a different histologic appearance of smaller cells that appear to be arranged in linear groups.

Mammography involves low-dose radiation and is used in diagnosis and is the most widely used screening technique for breast cancer. As a screening tool, mammography may detect lesions 1-2 years before they become palpable on breast self-examination. While the incidence of breast cancer in women has slowly increased over the past 20 years, mortality has decreased largely as a result of improved awareness and uptake of screening mammography. Current American Cancer Society guidelines recommend continued mammography screenings at least every other year after age 55 and continued for as long as a woman has a life expectancy > 10 years. Screening or diagnosis using MRI is usually reserved for individuals at high risk for breast cancer or a history of breast cancer before age 50.

For all newly diagnosed primary invasive breast cancers, biomarker testing for estrogen and progesterone receptor expression and HER2 expression are part of the standard workup recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to help guide treatment decisions. Biomarker testing showed that her tumor was ER+ and HER2-negative, the most common finding in breast cancer. The patient's history did not suggest a risk for BRCA or other familial cancer mutations, but molecular testing was done and was negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2. In postmenopausal women, ASCO and NCCN also recommend use of risk assessment tools, such as Oncotype DX, to determine whether chemotherapy will add benefit to systemic endocrine therapy. Postmenopausal patients with ER+/HER2-negative breast cancer, one to three positive nodes, and a score < 26 on the 21-gene Oncotype DX can safely forego cytotoxic chemotherapy and derive maximum survival benefit from hormonal therapy alone.

This patient was diagnosed with a primary tumor of approximately 25 mm, metastasis to two ipsilateral nodes, and no distant metastasis, or stage IIIA. Her risk recurrence score was 20, indicating that she could safely forego the rigors of cytotoxic chemotherapy. She underwent localized breast-conserving surgery and began adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (x 2 years) to be followed with an aromatase inhibitor (x 3 years).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Breast cancer is the most common tumor type and second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in women. Nearly 300,000 women (and 2800 men) will receive a new diagnosis of breast cancer in the United States in 2023. Despite improvements in treatment options, breast cancer still will lead to 43,700 deaths among women this year.

Breast tumors generally are either ductal or lobular in origin. Ductal carcinomas arise in the lining of the milk ducts and are the most commonly found tumor type in breast cancer. Almost 3 in 4 diagnosed breast cancers histologically are invasive ductal carcinomas, which have spread from the source into surrounding structures. It has no specific histologic indicators and is differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ by its having spread outside the duct. The presence of lymph node involvement in this patient also confirms invasive ductal carcinoma without metastatic spread. Invasive lobular carcinomas occur much less frequently and have a different histologic appearance of smaller cells that appear to be arranged in linear groups.

Mammography involves low-dose radiation and is used in diagnosis and is the most widely used screening technique for breast cancer. As a screening tool, mammography may detect lesions 1-2 years before they become palpable on breast self-examination. While the incidence of breast cancer in women has slowly increased over the past 20 years, mortality has decreased largely as a result of improved awareness and uptake of screening mammography. Current American Cancer Society guidelines recommend continued mammography screenings at least every other year after age 55 and continued for as long as a woman has a life expectancy > 10 years. Screening or diagnosis using MRI is usually reserved for individuals at high risk for breast cancer or a history of breast cancer before age 50.

For all newly diagnosed primary invasive breast cancers, biomarker testing for estrogen and progesterone receptor expression and HER2 expression are part of the standard workup recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to help guide treatment decisions. Biomarker testing showed that her tumor was ER+ and HER2-negative, the most common finding in breast cancer. The patient's history did not suggest a risk for BRCA or other familial cancer mutations, but molecular testing was done and was negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2. In postmenopausal women, ASCO and NCCN also recommend use of risk assessment tools, such as Oncotype DX, to determine whether chemotherapy will add benefit to systemic endocrine therapy. Postmenopausal patients with ER+/HER2-negative breast cancer, one to three positive nodes, and a score < 26 on the 21-gene Oncotype DX can safely forego cytotoxic chemotherapy and derive maximum survival benefit from hormonal therapy alone.

This patient was diagnosed with a primary tumor of approximately 25 mm, metastasis to two ipsilateral nodes, and no distant metastasis, or stage IIIA. Her risk recurrence score was 20, indicating that she could safely forego the rigors of cytotoxic chemotherapy. She underwent localized breast-conserving surgery and began adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (x 2 years) to be followed with an aromatase inhibitor (x 3 years).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 70-year-old woman presents for an annual exam and reports development of a firm lump in her right breast. She remarks that she has had discomfort in the same area for "at least a year," but the lump has become noticeable with even a cursory self-exam over the past 2 months. She has no previous history of breast cancer, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or other cardiometabolic disease. She had no previous abnormal findings on mammograms through age 65 but has not had one since. Her family history includes a grandmother who died of breast cancer at age 64 and her father who lived with prostate cancer for 20 years after diagnosis at age 60. The physical exam reveals a firm, palpable lump in the upper right quadrant of her right breast. The exam is otherwise normal for the patient's age, with minor osteoarthritis that she remarks has worsened over the past year. Mammography, image-guided biopsy, and biomarker and molecular testing are ordered. Lymph node testing reveals two involved nodes, and histology reveals the following (see image).

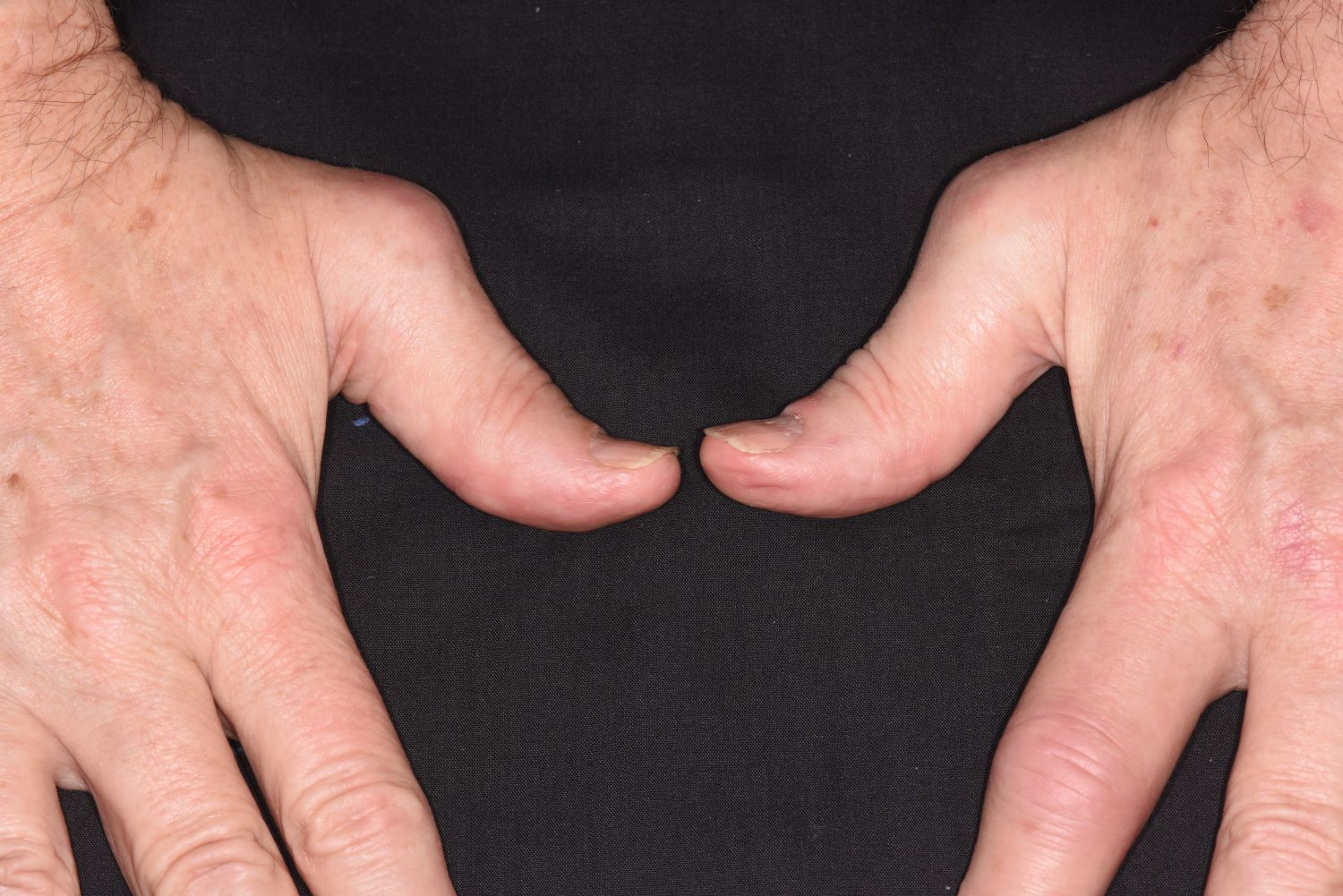

Pain in fingers for several months

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an immune-mediated arthritis that is almost always associated with plaque psoriasis. PsA is diagnosed in about 20% of patients with plaque psoriasis, and, in most patients, a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis precedes PsA development. However, in this patient, PsA appears to have become symptomatic at about the same time as the skin symptoms behind his ears, which is consistent with studies showing that PsA co-occurs with plaque psoriasis in 15% of patients and precedes plaque psoriasis diagnosis in 17% of patients. Environmental risk factors for PsA in genetically susceptible patients with plaque psoriasis include joint trauma, streptococcal infection, and certain antibiotics. Smoking appears to have a protective effect in PsA. PsA is more highly associated with severe plaque psoriasis than with mild plaque psoriasis.

PsA has a heterogeneous presentation, which may challenge diagnosis. It is classified by the degree of joint involvement as oligoarticular (four or fewer joints) or polyarticular (five or more joints). Radiographically, there are five main types of PsA, one of which is predominant involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) joints — the form seen in this patient. The other four types of PsA are symmetrical peripheral polyarthritis, asymmetrical mono- or oligoarthritis, axial spondyloarthropathy, and arthritis mutilans. DIP joint involvement with proliferative bone changes suggests a diagnosis of PsA over rheumatoid arthritis.

PsA is diagnosed using radiography, skin biopsy of affected skin areas, and complete blood and metabolic assessments. With advanced PsA, radiographs typically reveal bone destruction and disease-related bone formation (juxta-articular bone formation), resulting in erosions, joint destruction, and joint-space narrowing. Juxta-articular bone formation (presenting poorly defined ossification adjacent to the joint margin) is often the earliest radiographic clue before erosions may occur. Enthesitis in multiple entheses is typical of PsA vs osteoarthritis or mechanical injury. There are no specific tests to confirm PsA. Patients with PsA usually are rheumatoid factor negative. Inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are elevated in about 40% of patients with PsA.

In addition to plaques, extra-articular manifestations of PsA may include nail changes and chronic bilateral ocular disease. PsA is an articular manifestation of psoriasis but is still a systemic disease with deleterious effects on cardiometabolic factors; increased mortality with myocardial infarction; and possible involvement of other immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, that share a common pathway of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha overexpression.

Early treatment with disease-modifying drugs plus nonpharmacologic interventions is crucial to minimizing disability progression and optimizing patients' quality of life. Nonpharmacologic interventions include physical and occupational therapy and exercise. Symptomatic therapies (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids) can be used to relieve mild symptoms. Assessment for cardiometabolic, renal, and other systemic impacts of PsA is essential.

Biologic therapies are key to preventing disease progression. The most broadly targeted are the TNF-alpha inhibitors, which are commonly recommended as first-line therapy in moderate to severe PsA or in patients with radiographic damage. The interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors ixekizumab and secukinumab and the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab have targets downstream of TNF-alpha. Treatment options also include oral small molecule inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (apremilast) or Janus kinase (tofacitinib, upadacitinib). Recognition of the role of IL-23 as a key cytokine in PsA development through promotion of Th17 differentiation has led to availability of drugs specifically targeting IL-23(p19) (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab). All have been studied, but only guselkumab and risankizumab currently are approved for treatment of PsA. Each class of drugs has specific benefits and risks, which should be discussed with patients before treatment initiation. Patient comorbidities should also be considered in choosing treatment.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an immune-mediated arthritis that is almost always associated with plaque psoriasis. PsA is diagnosed in about 20% of patients with plaque psoriasis, and, in most patients, a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis precedes PsA development. However, in this patient, PsA appears to have become symptomatic at about the same time as the skin symptoms behind his ears, which is consistent with studies showing that PsA co-occurs with plaque psoriasis in 15% of patients and precedes plaque psoriasis diagnosis in 17% of patients. Environmental risk factors for PsA in genetically susceptible patients with plaque psoriasis include joint trauma, streptococcal infection, and certain antibiotics. Smoking appears to have a protective effect in PsA. PsA is more highly associated with severe plaque psoriasis than with mild plaque psoriasis.

PsA has a heterogeneous presentation, which may challenge diagnosis. It is classified by the degree of joint involvement as oligoarticular (four or fewer joints) or polyarticular (five or more joints). Radiographically, there are five main types of PsA, one of which is predominant involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) joints — the form seen in this patient. The other four types of PsA are symmetrical peripheral polyarthritis, asymmetrical mono- or oligoarthritis, axial spondyloarthropathy, and arthritis mutilans. DIP joint involvement with proliferative bone changes suggests a diagnosis of PsA over rheumatoid arthritis.

PsA is diagnosed using radiography, skin biopsy of affected skin areas, and complete blood and metabolic assessments. With advanced PsA, radiographs typically reveal bone destruction and disease-related bone formation (juxta-articular bone formation), resulting in erosions, joint destruction, and joint-space narrowing. Juxta-articular bone formation (presenting poorly defined ossification adjacent to the joint margin) is often the earliest radiographic clue before erosions may occur. Enthesitis in multiple entheses is typical of PsA vs osteoarthritis or mechanical injury. There are no specific tests to confirm PsA. Patients with PsA usually are rheumatoid factor negative. Inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are elevated in about 40% of patients with PsA.

In addition to plaques, extra-articular manifestations of PsA may include nail changes and chronic bilateral ocular disease. PsA is an articular manifestation of psoriasis but is still a systemic disease with deleterious effects on cardiometabolic factors; increased mortality with myocardial infarction; and possible involvement of other immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, that share a common pathway of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha overexpression.

Early treatment with disease-modifying drugs plus nonpharmacologic interventions is crucial to minimizing disability progression and optimizing patients' quality of life. Nonpharmacologic interventions include physical and occupational therapy and exercise. Symptomatic therapies (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids) can be used to relieve mild symptoms. Assessment for cardiometabolic, renal, and other systemic impacts of PsA is essential.

Biologic therapies are key to preventing disease progression. The most broadly targeted are the TNF-alpha inhibitors, which are commonly recommended as first-line therapy in moderate to severe PsA or in patients with radiographic damage. The interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors ixekizumab and secukinumab and the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab have targets downstream of TNF-alpha. Treatment options also include oral small molecule inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (apremilast) or Janus kinase (tofacitinib, upadacitinib). Recognition of the role of IL-23 as a key cytokine in PsA development through promotion of Th17 differentiation has led to availability of drugs specifically targeting IL-23(p19) (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab). All have been studied, but only guselkumab and risankizumab currently are approved for treatment of PsA. Each class of drugs has specific benefits and risks, which should be discussed with patients before treatment initiation. Patient comorbidities should also be considered in choosing treatment.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an immune-mediated arthritis that is almost always associated with plaque psoriasis. PsA is diagnosed in about 20% of patients with plaque psoriasis, and, in most patients, a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis precedes PsA development. However, in this patient, PsA appears to have become symptomatic at about the same time as the skin symptoms behind his ears, which is consistent with studies showing that PsA co-occurs with plaque psoriasis in 15% of patients and precedes plaque psoriasis diagnosis in 17% of patients. Environmental risk factors for PsA in genetically susceptible patients with plaque psoriasis include joint trauma, streptococcal infection, and certain antibiotics. Smoking appears to have a protective effect in PsA. PsA is more highly associated with severe plaque psoriasis than with mild plaque psoriasis.

PsA has a heterogeneous presentation, which may challenge diagnosis. It is classified by the degree of joint involvement as oligoarticular (four or fewer joints) or polyarticular (five or more joints). Radiographically, there are five main types of PsA, one of which is predominant involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) joints — the form seen in this patient. The other four types of PsA are symmetrical peripheral polyarthritis, asymmetrical mono- or oligoarthritis, axial spondyloarthropathy, and arthritis mutilans. DIP joint involvement with proliferative bone changes suggests a diagnosis of PsA over rheumatoid arthritis.

PsA is diagnosed using radiography, skin biopsy of affected skin areas, and complete blood and metabolic assessments. With advanced PsA, radiographs typically reveal bone destruction and disease-related bone formation (juxta-articular bone formation), resulting in erosions, joint destruction, and joint-space narrowing. Juxta-articular bone formation (presenting poorly defined ossification adjacent to the joint margin) is often the earliest radiographic clue before erosions may occur. Enthesitis in multiple entheses is typical of PsA vs osteoarthritis or mechanical injury. There are no specific tests to confirm PsA. Patients with PsA usually are rheumatoid factor negative. Inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are elevated in about 40% of patients with PsA.

In addition to plaques, extra-articular manifestations of PsA may include nail changes and chronic bilateral ocular disease. PsA is an articular manifestation of psoriasis but is still a systemic disease with deleterious effects on cardiometabolic factors; increased mortality with myocardial infarction; and possible involvement of other immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, that share a common pathway of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha overexpression.

Early treatment with disease-modifying drugs plus nonpharmacologic interventions is crucial to minimizing disability progression and optimizing patients' quality of life. Nonpharmacologic interventions include physical and occupational therapy and exercise. Symptomatic therapies (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids) can be used to relieve mild symptoms. Assessment for cardiometabolic, renal, and other systemic impacts of PsA is essential.

Biologic therapies are key to preventing disease progression. The most broadly targeted are the TNF-alpha inhibitors, which are commonly recommended as first-line therapy in moderate to severe PsA or in patients with radiographic damage. The interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitors ixekizumab and secukinumab and the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab have targets downstream of TNF-alpha. Treatment options also include oral small molecule inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (apremilast) or Janus kinase (tofacitinib, upadacitinib). Recognition of the role of IL-23 as a key cytokine in PsA development through promotion of Th17 differentiation has led to availability of drugs specifically targeting IL-23(p19) (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab). All have been studied, but only guselkumab and risankizumab currently are approved for treatment of PsA. Each class of drugs has specific benefits and risks, which should be discussed with patients before treatment initiation. Patient comorbidities should also be considered in choosing treatment.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 58-year-old man presents with pain in fingers of several months' duration, which is moderately relieved with over-the-counter naproxen. He is concerned about "crooked" fingers and is worried that his work will be affected. He is overweight (BMI, 28.8), hypertensive, hypercholesterolemic, and a nonsmoker. The patient also reports a 6-month history of itchy "scalp" behind the ears, not relieved with dandruff shampoos. Physical exam reveals advanced deformity in index and middle fingers of both hands and no evident deformity in the wrists or metacarpophalangeal joints. Nails are pitted and discolored. Scalp behind ears shows well-demarcated, scaly patches. Lab work, radiography, and biopsy of the retroauricular area are ordered.

Fatigue and night sweats

Given the patient's presentation of generalized lymphadenopathy, B symptoms, fatigue (probably from anemia), hepatosplenomegaly, immunophenotyping results of flow cell cytometry, and central nervous system (CNS) involvement, blastoid mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is the most likely diagnosis. Although small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) most often occur in men 60-70 years old with similar clinical findings, an initial presentation with a stage IV involvement is rare; moreover, SLL/CLL and DLBCL are typically CD23 positive. Pleomorphic MCL displays larger and more pleomorphic cells with irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and pale cytoplasm, resembling DLBCL.

MCL is a rare type of mature B-cell lymphoma that was first described in 1992 and was recognized by World Health Organization in 2001. MCL represents 3%-10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases, with an incidence between 0.50 and 1.0 per 100,000 population. Men are more likely than women to present with MCL by a ratio of 3:1, with a median age at presentation of 67 years. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. MCL usually affects the lymph nodes, with the spleen and bone marrow being significant sites of the disease. Stage IV disease is present in 70% of patients; the gastrointestinal tract, lung, pleura, and CNS are also frequently affected.

Besides classic MCL, several variants have been described that exhibit specific morphologic features, including small cell variant mimicking SLL marginal zone-like MCL (resembling marginal zone lymphoma), in situ mantle cell neoplasia (associated with indolent course), and two aggressive variants, including blastoid and pleomorphic MCL. These blastoid and pleomorphic variants are defined by cytomorphologic features; the criteria are somewhat subjective, but both are characterized by highly aggressive features and a dismal clinical course. In clinical cohorts, the frequency of these subsets varies widely but probably represents ∼10% of all cases.

Diagnosing MCL requires a multipronged approach. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveal monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D that are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are used more for staging than diagnosis. Blood studies commonly reveal anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with 20%-40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000 cells/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase when tumor burden is high. The term "blastoid mantle cell lymphoma" describes a morphologic subgroup of lymphomas with blastic features that morphologically resemble the lymphoblasts found in lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (roundish nuclei, a narrow rim of cytoplasm, and finely dispersed chromatin).

MCL is associated with a poor prognosis; patients generally experience disease progression after chemotherapy, even with initial treatment response rates ranging from 50% to 70%. The 5-year survival rate is about 50% in the overall population, 75% in persons younger than 50 years, and 36% in those aged 75 years or older. A poorer prognosis is also associated with the presence of the blastoid variant, commonly associated with TP53 mutations. Median survival can vary by as much as 5 years, depending on the expression of cyclin D1 and other proliferation signature genes.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's presentation of generalized lymphadenopathy, B symptoms, fatigue (probably from anemia), hepatosplenomegaly, immunophenotyping results of flow cell cytometry, and central nervous system (CNS) involvement, blastoid mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is the most likely diagnosis. Although small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) most often occur in men 60-70 years old with similar clinical findings, an initial presentation with a stage IV involvement is rare; moreover, SLL/CLL and DLBCL are typically CD23 positive. Pleomorphic MCL displays larger and more pleomorphic cells with irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and pale cytoplasm, resembling DLBCL.

MCL is a rare type of mature B-cell lymphoma that was first described in 1992 and was recognized by World Health Organization in 2001. MCL represents 3%-10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases, with an incidence between 0.50 and 1.0 per 100,000 population. Men are more likely than women to present with MCL by a ratio of 3:1, with a median age at presentation of 67 years. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. MCL usually affects the lymph nodes, with the spleen and bone marrow being significant sites of the disease. Stage IV disease is present in 70% of patients; the gastrointestinal tract, lung, pleura, and CNS are also frequently affected.

Besides classic MCL, several variants have been described that exhibit specific morphologic features, including small cell variant mimicking SLL marginal zone-like MCL (resembling marginal zone lymphoma), in situ mantle cell neoplasia (associated with indolent course), and two aggressive variants, including blastoid and pleomorphic MCL. These blastoid and pleomorphic variants are defined by cytomorphologic features; the criteria are somewhat subjective, but both are characterized by highly aggressive features and a dismal clinical course. In clinical cohorts, the frequency of these subsets varies widely but probably represents ∼10% of all cases.

Diagnosing MCL requires a multipronged approach. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveal monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D that are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are used more for staging than diagnosis. Blood studies commonly reveal anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with 20%-40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000 cells/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase when tumor burden is high. The term "blastoid mantle cell lymphoma" describes a morphologic subgroup of lymphomas with blastic features that morphologically resemble the lymphoblasts found in lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (roundish nuclei, a narrow rim of cytoplasm, and finely dispersed chromatin).

MCL is associated with a poor prognosis; patients generally experience disease progression after chemotherapy, even with initial treatment response rates ranging from 50% to 70%. The 5-year survival rate is about 50% in the overall population, 75% in persons younger than 50 years, and 36% in those aged 75 years or older. A poorer prognosis is also associated with the presence of the blastoid variant, commonly associated with TP53 mutations. Median survival can vary by as much as 5 years, depending on the expression of cyclin D1 and other proliferation signature genes.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's presentation of generalized lymphadenopathy, B symptoms, fatigue (probably from anemia), hepatosplenomegaly, immunophenotyping results of flow cell cytometry, and central nervous system (CNS) involvement, blastoid mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is the most likely diagnosis. Although small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) most often occur in men 60-70 years old with similar clinical findings, an initial presentation with a stage IV involvement is rare; moreover, SLL/CLL and DLBCL are typically CD23 positive. Pleomorphic MCL displays larger and more pleomorphic cells with irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and pale cytoplasm, resembling DLBCL.

MCL is a rare type of mature B-cell lymphoma that was first described in 1992 and was recognized by World Health Organization in 2001. MCL represents 3%-10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases, with an incidence between 0.50 and 1.0 per 100,000 population. Men are more likely than women to present with MCL by a ratio of 3:1, with a median age at presentation of 67 years. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. MCL usually affects the lymph nodes, with the spleen and bone marrow being significant sites of the disease. Stage IV disease is present in 70% of patients; the gastrointestinal tract, lung, pleura, and CNS are also frequently affected.

Besides classic MCL, several variants have been described that exhibit specific morphologic features, including small cell variant mimicking SLL marginal zone-like MCL (resembling marginal zone lymphoma), in situ mantle cell neoplasia (associated with indolent course), and two aggressive variants, including blastoid and pleomorphic MCL. These blastoid and pleomorphic variants are defined by cytomorphologic features; the criteria are somewhat subjective, but both are characterized by highly aggressive features and a dismal clinical course. In clinical cohorts, the frequency of these subsets varies widely but probably represents ∼10% of all cases.

Diagnosing MCL requires a multipronged approach. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveal monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D that are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are used more for staging than diagnosis. Blood studies commonly reveal anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with 20%-40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000 cells/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase when tumor burden is high. The term "blastoid mantle cell lymphoma" describes a morphologic subgroup of lymphomas with blastic features that morphologically resemble the lymphoblasts found in lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (roundish nuclei, a narrow rim of cytoplasm, and finely dispersed chromatin).

MCL is associated with a poor prognosis; patients generally experience disease progression after chemotherapy, even with initial treatment response rates ranging from 50% to 70%. The 5-year survival rate is about 50% in the overall population, 75% in persons younger than 50 years, and 36% in those aged 75 years or older. A poorer prognosis is also associated with the presence of the blastoid variant, commonly associated with TP53 mutations. Median survival can vary by as much as 5 years, depending on the expression of cyclin D1 and other proliferation signature genes.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 65-year-old man presents to the oncology clinic with a 6-week history of fatigue, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss of 15 lb. He reports occasional fevers and generalized discomfort in his abdomen and has recently been experiencing painful headaches that are not relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. His medical history is otherwise unremarkable except for mild hypertension, for which he takes medication. His family history is unremarkable.

Physical examination reveals palpable lymph nodes in the neck, axilla, and inguinal regions; the spleen is palpable 3 cm below the left costal margin. A complete blood count shows anemia (hemoglobin level, 9.1g/dL) thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 90,000 cells/μL), and lymphocytosis (total leukocyte count, 5000 cells/μL); peripheral blood smear shows small, monomorphic lymphoid cells with oval-shaped nuclei and high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. Flow cytometry of lymph node biopsy is CD5-positive and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, and CD22) but lacks expression of CD10 and CD23. A T2-weighted MRI is ordered.

Pallor and weight loss