User login

Plummer‐Vinson (Patterson‐Kelly) Syndrome

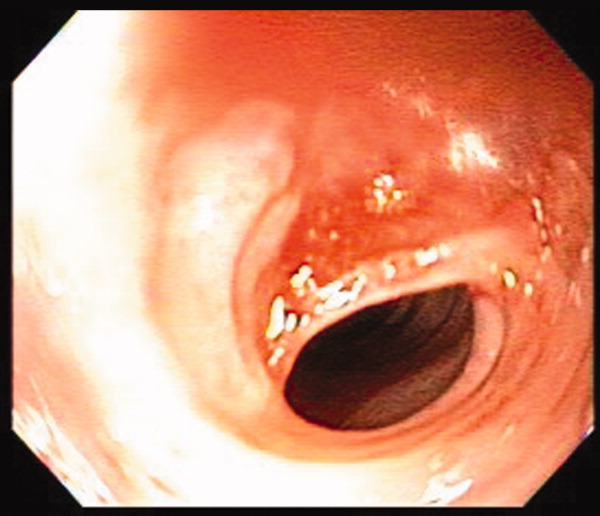

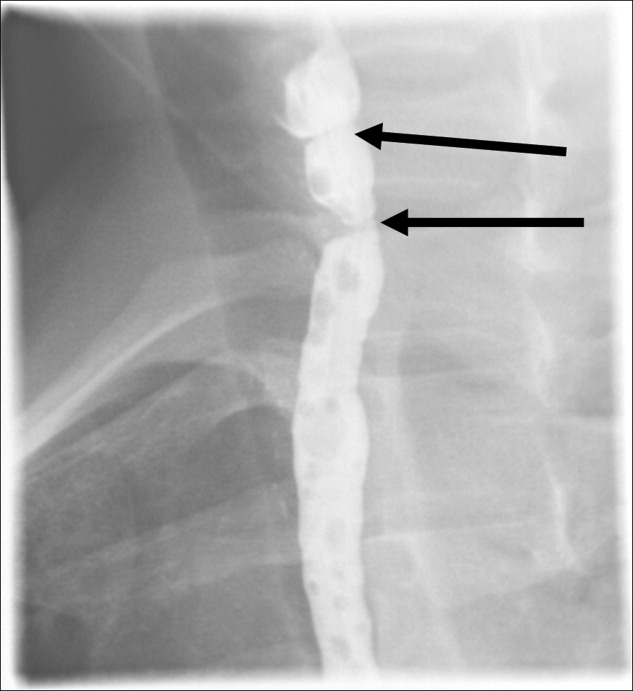

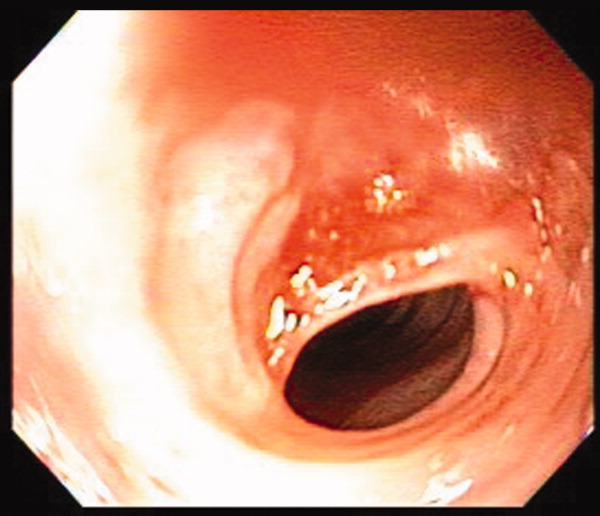

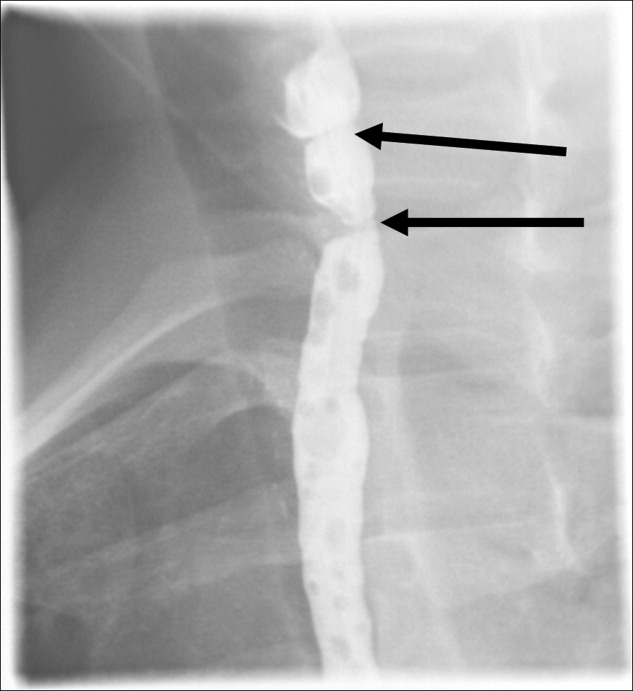

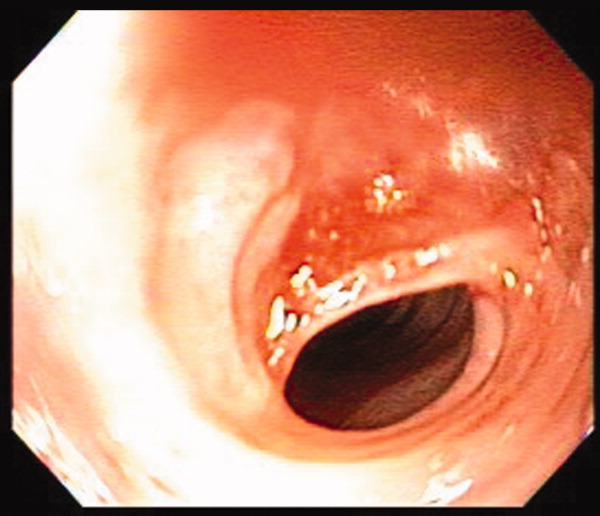

A 41‐year‐old woman with menorrhagia presented with dysphagia and fatigue. An examination revealed koilonychia (Figure 1), cheilosis, atrophic glossitis, and conjunctival pallor. The hemoglobin level was 4.3 g/dL, the mean corpuscular volume was 48.3, the iron level was 6 g/dL, and the ferritin level was undetectable (1 ng/mL). A barium esophagram demonstrated probable esophageal webs (Figure 2). Esophageal webs were confirmed by upper endoscopy (Figure 3) and successfully dilated with a balloon dilator sequentially at 8, 9, and 10 mm. She was transfused, treated for menorrhagia, and given ferrous sulfate and ascorbic acid (to improve iron absorption).

Koilonychia (or spoon nails) is derived from the Greek word for hollow nails. Spoon nails are associated with iron deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, trauma, chronic solvent exposure, and nail‐patella syndrome, but they can be normal in infants.1 Patterson and Kelly independently described the triad of iron‐deficiency anemia, dysphagia, and upper esophageal webs in 1919 following Plummer's (1912) and Vinson's (1919) similar but less comprehensive descriptions of hysterical dysphagia.2 Plummer‐Vinson syndrome is rare, but precise prevalence data are unavailable.2 Whether iron deficiency truly causes esophageal webs is debated, but iron deficiency is thought to weaken esophageal musculature and cause epithelial cell atrophy.2 Autoimmunity and genetic predisposition are other putative causes. Dilation of esophageal webs is usually curative, although their association with an increased risk of upper alimentary cancers may justify surveillance endoscopy.3

- ,.Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, Surgery.3rd ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Saunders;2005.

- .Plummer‐Vinson syndrome.Orphanet J Rare Dis.2006;1:36–39.

- .Squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus.Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol.2001;15(2):249–265.

A 41‐year‐old woman with menorrhagia presented with dysphagia and fatigue. An examination revealed koilonychia (Figure 1), cheilosis, atrophic glossitis, and conjunctival pallor. The hemoglobin level was 4.3 g/dL, the mean corpuscular volume was 48.3, the iron level was 6 g/dL, and the ferritin level was undetectable (1 ng/mL). A barium esophagram demonstrated probable esophageal webs (Figure 2). Esophageal webs were confirmed by upper endoscopy (Figure 3) and successfully dilated with a balloon dilator sequentially at 8, 9, and 10 mm. She was transfused, treated for menorrhagia, and given ferrous sulfate and ascorbic acid (to improve iron absorption).

Koilonychia (or spoon nails) is derived from the Greek word for hollow nails. Spoon nails are associated with iron deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, trauma, chronic solvent exposure, and nail‐patella syndrome, but they can be normal in infants.1 Patterson and Kelly independently described the triad of iron‐deficiency anemia, dysphagia, and upper esophageal webs in 1919 following Plummer's (1912) and Vinson's (1919) similar but less comprehensive descriptions of hysterical dysphagia.2 Plummer‐Vinson syndrome is rare, but precise prevalence data are unavailable.2 Whether iron deficiency truly causes esophageal webs is debated, but iron deficiency is thought to weaken esophageal musculature and cause epithelial cell atrophy.2 Autoimmunity and genetic predisposition are other putative causes. Dilation of esophageal webs is usually curative, although their association with an increased risk of upper alimentary cancers may justify surveillance endoscopy.3

A 41‐year‐old woman with menorrhagia presented with dysphagia and fatigue. An examination revealed koilonychia (Figure 1), cheilosis, atrophic glossitis, and conjunctival pallor. The hemoglobin level was 4.3 g/dL, the mean corpuscular volume was 48.3, the iron level was 6 g/dL, and the ferritin level was undetectable (1 ng/mL). A barium esophagram demonstrated probable esophageal webs (Figure 2). Esophageal webs were confirmed by upper endoscopy (Figure 3) and successfully dilated with a balloon dilator sequentially at 8, 9, and 10 mm. She was transfused, treated for menorrhagia, and given ferrous sulfate and ascorbic acid (to improve iron absorption).

Koilonychia (or spoon nails) is derived from the Greek word for hollow nails. Spoon nails are associated with iron deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, trauma, chronic solvent exposure, and nail‐patella syndrome, but they can be normal in infants.1 Patterson and Kelly independently described the triad of iron‐deficiency anemia, dysphagia, and upper esophageal webs in 1919 following Plummer's (1912) and Vinson's (1919) similar but less comprehensive descriptions of hysterical dysphagia.2 Plummer‐Vinson syndrome is rare, but precise prevalence data are unavailable.2 Whether iron deficiency truly causes esophageal webs is debated, but iron deficiency is thought to weaken esophageal musculature and cause epithelial cell atrophy.2 Autoimmunity and genetic predisposition are other putative causes. Dilation of esophageal webs is usually curative, although their association with an increased risk of upper alimentary cancers may justify surveillance endoscopy.3

- ,.Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, Surgery.3rd ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Saunders;2005.

- .Plummer‐Vinson syndrome.Orphanet J Rare Dis.2006;1:36–39.

- .Squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus.Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol.2001;15(2):249–265.

- ,.Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, Surgery.3rd ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Saunders;2005.

- .Plummer‐Vinson syndrome.Orphanet J Rare Dis.2006;1:36–39.

- .Squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus.Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol.2001;15(2):249–265.

Severe babesiosis

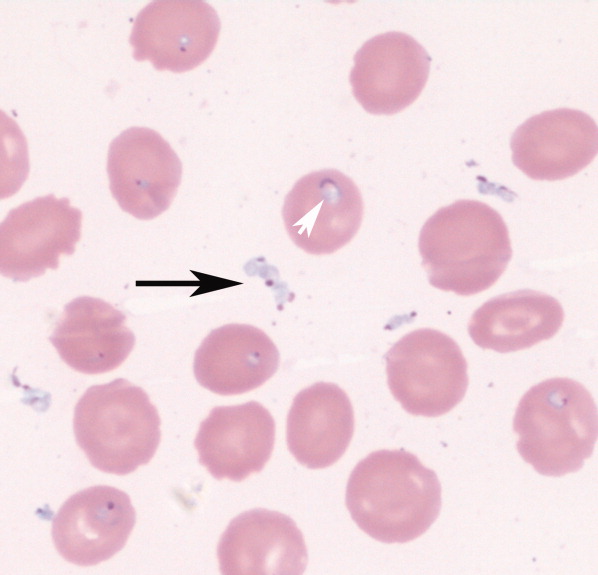

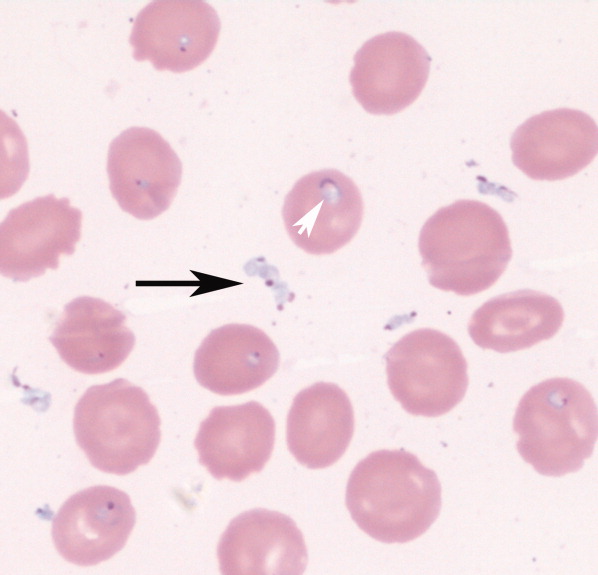

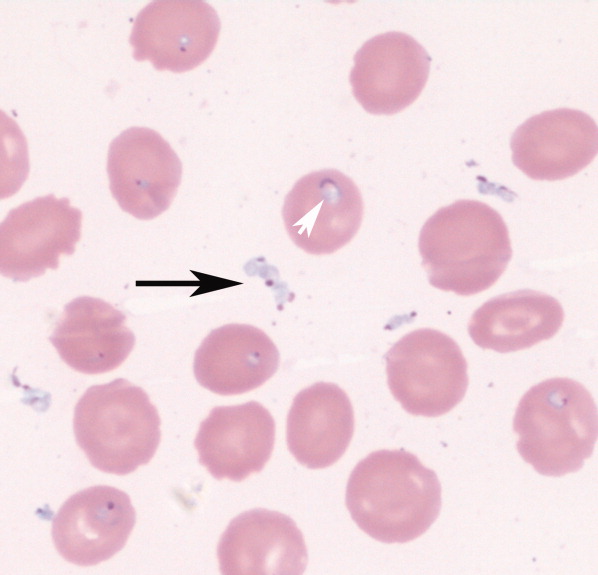

An 85‐year‐old male from rural southern New Jersey with history of innumerable tick bites over many years was admitted for fever of unknown origin. On hospital day 2, his hemoglobin dropped from 11.3 g/dL to 7.5 g/dL, with an associated elevated indirect bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase. Blood smear showed numerous intracellular and extracellular trophozoites, with approximately 10% to 30% of red cells infected, consistent with severe babesiosis. Given his high parasitemia, new hypoxia, lethargy, and advanced age, treatment was initiated with intravenous antibiotics and red cell exchange transfusion.

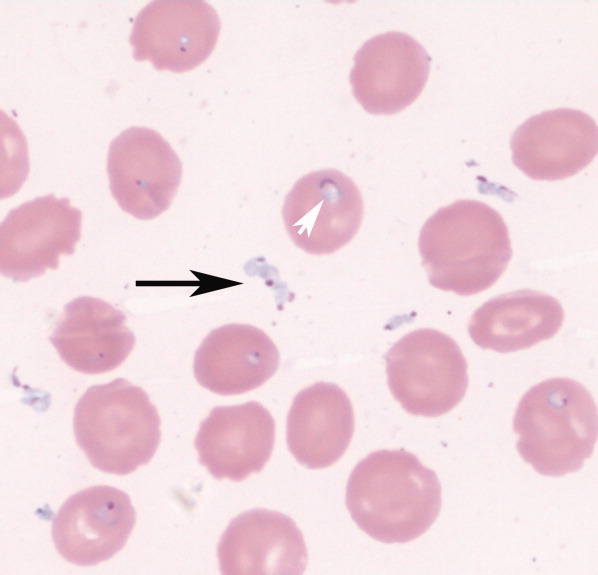

Babesiosis should be considered on the differential diagnosis of hemolytic anemia in patients that live in or have traveled to endemic areas, especially with history of tick bites. The most common appearance on blood smear is round to oval rings with pale blue cytoplasm and a red‐staining nucleus (Fig. 1). Exoerythrocytic parasites or the pathognomonic Maltese Cross tetrad forms (not present in our patient's smear) help to differentiate from falciparum malaria.

The patient's parasite burden and clinical status markedly improved with treatment and he was discharged home. 0

An 85‐year‐old male from rural southern New Jersey with history of innumerable tick bites over many years was admitted for fever of unknown origin. On hospital day 2, his hemoglobin dropped from 11.3 g/dL to 7.5 g/dL, with an associated elevated indirect bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase. Blood smear showed numerous intracellular and extracellular trophozoites, with approximately 10% to 30% of red cells infected, consistent with severe babesiosis. Given his high parasitemia, new hypoxia, lethargy, and advanced age, treatment was initiated with intravenous antibiotics and red cell exchange transfusion.

Babesiosis should be considered on the differential diagnosis of hemolytic anemia in patients that live in or have traveled to endemic areas, especially with history of tick bites. The most common appearance on blood smear is round to oval rings with pale blue cytoplasm and a red‐staining nucleus (Fig. 1). Exoerythrocytic parasites or the pathognomonic Maltese Cross tetrad forms (not present in our patient's smear) help to differentiate from falciparum malaria.

The patient's parasite burden and clinical status markedly improved with treatment and he was discharged home. 0

An 85‐year‐old male from rural southern New Jersey with history of innumerable tick bites over many years was admitted for fever of unknown origin. On hospital day 2, his hemoglobin dropped from 11.3 g/dL to 7.5 g/dL, with an associated elevated indirect bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase. Blood smear showed numerous intracellular and extracellular trophozoites, with approximately 10% to 30% of red cells infected, consistent with severe babesiosis. Given his high parasitemia, new hypoxia, lethargy, and advanced age, treatment was initiated with intravenous antibiotics and red cell exchange transfusion.

Babesiosis should be considered on the differential diagnosis of hemolytic anemia in patients that live in or have traveled to endemic areas, especially with history of tick bites. The most common appearance on blood smear is round to oval rings with pale blue cytoplasm and a red‐staining nucleus (Fig. 1). Exoerythrocytic parasites or the pathognomonic Maltese Cross tetrad forms (not present in our patient's smear) help to differentiate from falciparum malaria.

The patient's parasite burden and clinical status markedly improved with treatment and he was discharged home. 0

“Patchy” pneumonia

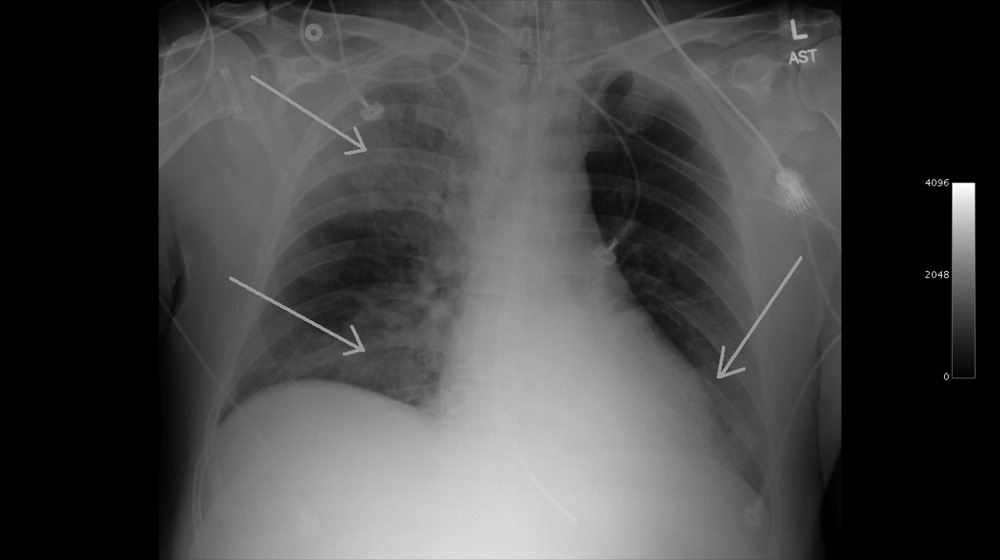

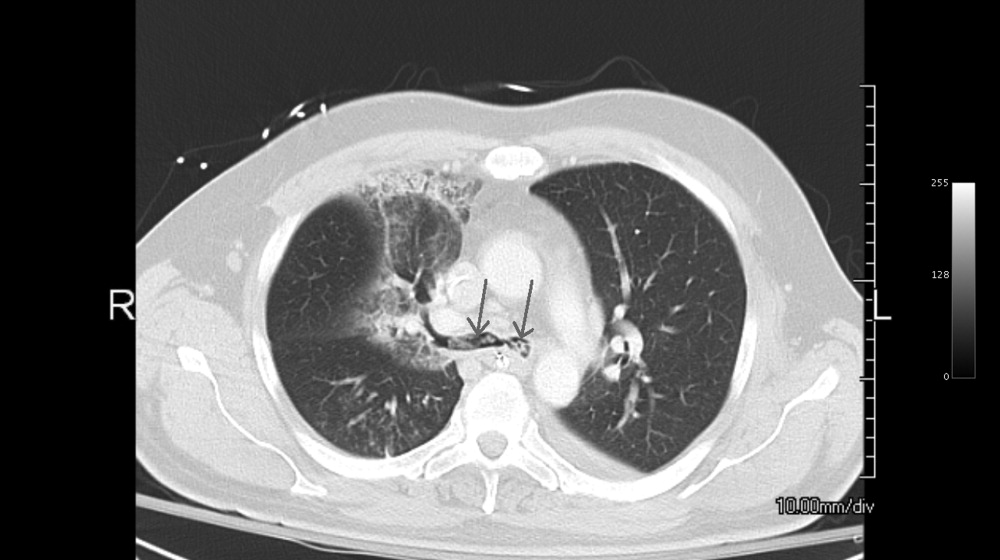

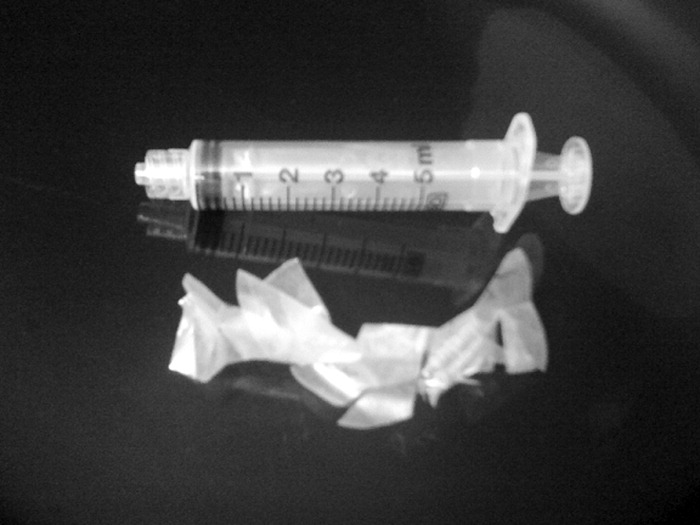

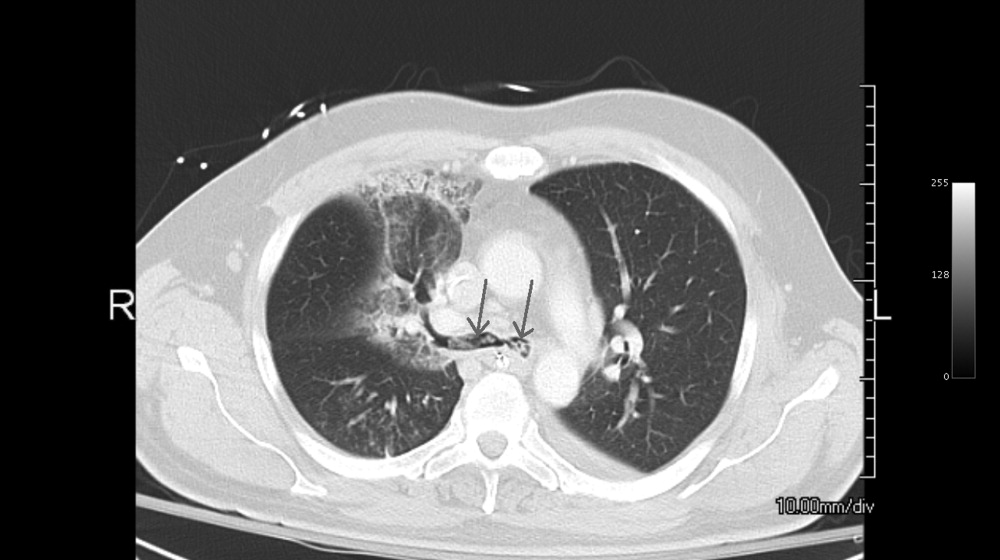

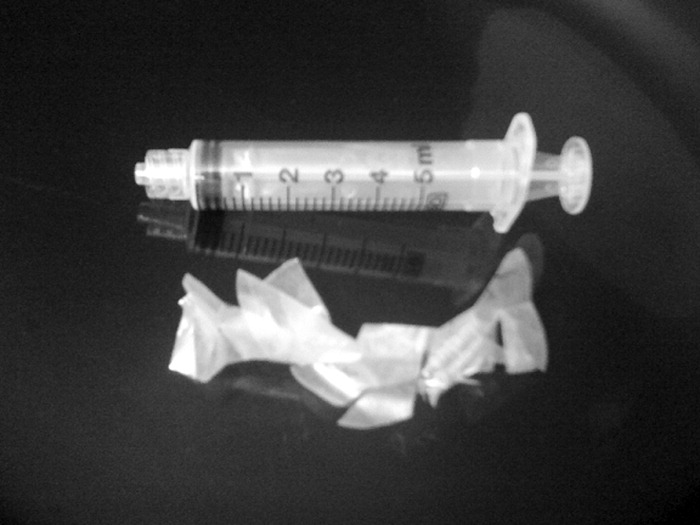

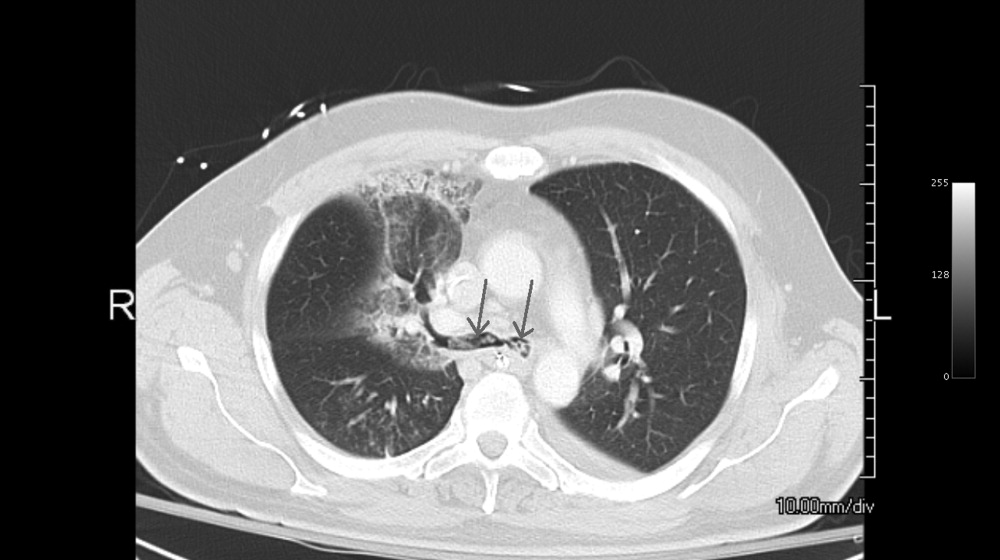

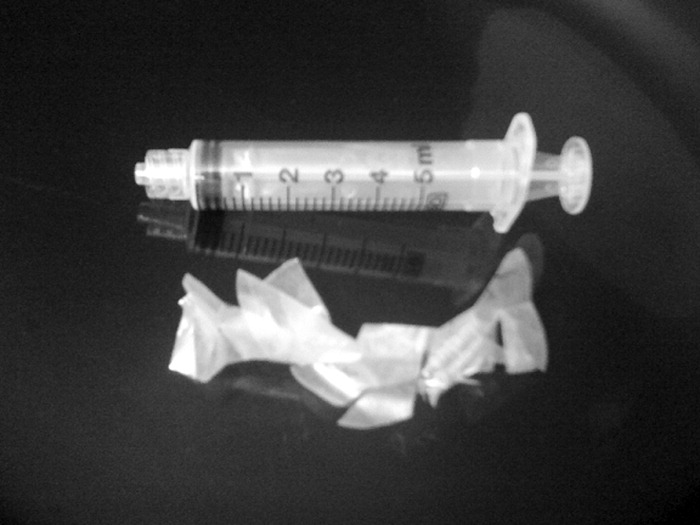

A 49‐year‐old retired air‐force officer presented with productive cough lasting 1 week. He was in good health except for back pain after a motor vehicle accident, 2 years ago, for which he took unspecified pain medications. His condition rapidly deteriorated necessitating mechanical ventilation. Chest x‐ray showed multilobar pneumonia (Figure 1). Blood and sputum cultures grew Serratia marcescens. Chest computed tomography (CT)‐scan showed multilobar involvement with debris in his airways that was thought to be respiratory secretions (Figure 2, arrows). He remained intubated for 2 weeks before his clinical status improved enough to permit extubation. Immediately following extubation, he coughed up a ball of crumpled, plastic material. His condition subsequently improved dramatically with complete radiological resolution of his pneumonia. On analyzing the foreign body, it turned out to be a fenestrated fentanyl patch (Figure 3). The patient then reported that he often cut‐up used fentanyl patches and sucked on them for an extra high. In retrospect, the endobronchial debris was actually the patch straddling the carina and had prevented rapid recovery. Aspiration of unusual foreign bodies have been reported in the literature. This foreign body masqueraded as respiratory secretions on imaging preventing early detection. This clinical encounter brings to light yet another innovative, but potentially deadly, form of drug abuse. It also emphasizes the importance of early bronchoscopy in nonresolving pneumonias.

A 49‐year‐old retired air‐force officer presented with productive cough lasting 1 week. He was in good health except for back pain after a motor vehicle accident, 2 years ago, for which he took unspecified pain medications. His condition rapidly deteriorated necessitating mechanical ventilation. Chest x‐ray showed multilobar pneumonia (Figure 1). Blood and sputum cultures grew Serratia marcescens. Chest computed tomography (CT)‐scan showed multilobar involvement with debris in his airways that was thought to be respiratory secretions (Figure 2, arrows). He remained intubated for 2 weeks before his clinical status improved enough to permit extubation. Immediately following extubation, he coughed up a ball of crumpled, plastic material. His condition subsequently improved dramatically with complete radiological resolution of his pneumonia. On analyzing the foreign body, it turned out to be a fenestrated fentanyl patch (Figure 3). The patient then reported that he often cut‐up used fentanyl patches and sucked on them for an extra high. In retrospect, the endobronchial debris was actually the patch straddling the carina and had prevented rapid recovery. Aspiration of unusual foreign bodies have been reported in the literature. This foreign body masqueraded as respiratory secretions on imaging preventing early detection. This clinical encounter brings to light yet another innovative, but potentially deadly, form of drug abuse. It also emphasizes the importance of early bronchoscopy in nonresolving pneumonias.

A 49‐year‐old retired air‐force officer presented with productive cough lasting 1 week. He was in good health except for back pain after a motor vehicle accident, 2 years ago, for which he took unspecified pain medications. His condition rapidly deteriorated necessitating mechanical ventilation. Chest x‐ray showed multilobar pneumonia (Figure 1). Blood and sputum cultures grew Serratia marcescens. Chest computed tomography (CT)‐scan showed multilobar involvement with debris in his airways that was thought to be respiratory secretions (Figure 2, arrows). He remained intubated for 2 weeks before his clinical status improved enough to permit extubation. Immediately following extubation, he coughed up a ball of crumpled, plastic material. His condition subsequently improved dramatically with complete radiological resolution of his pneumonia. On analyzing the foreign body, it turned out to be a fenestrated fentanyl patch (Figure 3). The patient then reported that he often cut‐up used fentanyl patches and sucked on them for an extra high. In retrospect, the endobronchial debris was actually the patch straddling the carina and had prevented rapid recovery. Aspiration of unusual foreign bodies have been reported in the literature. This foreign body masqueraded as respiratory secretions on imaging preventing early detection. This clinical encounter brings to light yet another innovative, but potentially deadly, form of drug abuse. It also emphasizes the importance of early bronchoscopy in nonresolving pneumonias.

Wegener's Granulomatosis

A previously healthy 21‐year‐old man presented with 6 weeks of low‐grade fever, sore throat, red eyes, and hematuria. Physical examination revealed episcleral injection consistent with episcleritis (Figure 1), oral ulcers (Figure 2, black arrows), diffuse fine crackles on chest auscultation and testicular tenderness. Laboratory workup was significant for leukocytosis (14,000 cell/mL), hematuria with red blood cell (RBC) casts and serum creatinine level of 2.1 mg/dL, which subsequently rose rapidly to 4.1 mg/dL. Test for cytoplasmic‐stainingantineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (C‐ANCA) was positive. Antiproteinase 3 (PR3) antibodies were also positive. Chest x‐ray showed bilateral pulmonary opacities and sinus computed tomography (CT) scan showed mucosal thickening of the sinuses consistent with sinusitis (Figure 3). Renal biopsy revealed segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis that was pauci‐immune on immunofluorescence staining. The patient was diagnosed with Wegener's granulomatosis with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. He was treated with intravenous corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. The patient's symptoms and acute renal failure resolved with this medical regimen.

A previously healthy 21‐year‐old man presented with 6 weeks of low‐grade fever, sore throat, red eyes, and hematuria. Physical examination revealed episcleral injection consistent with episcleritis (Figure 1), oral ulcers (Figure 2, black arrows), diffuse fine crackles on chest auscultation and testicular tenderness. Laboratory workup was significant for leukocytosis (14,000 cell/mL), hematuria with red blood cell (RBC) casts and serum creatinine level of 2.1 mg/dL, which subsequently rose rapidly to 4.1 mg/dL. Test for cytoplasmic‐stainingantineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (C‐ANCA) was positive. Antiproteinase 3 (PR3) antibodies were also positive. Chest x‐ray showed bilateral pulmonary opacities and sinus computed tomography (CT) scan showed mucosal thickening of the sinuses consistent with sinusitis (Figure 3). Renal biopsy revealed segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis that was pauci‐immune on immunofluorescence staining. The patient was diagnosed with Wegener's granulomatosis with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. He was treated with intravenous corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. The patient's symptoms and acute renal failure resolved with this medical regimen.

A previously healthy 21‐year‐old man presented with 6 weeks of low‐grade fever, sore throat, red eyes, and hematuria. Physical examination revealed episcleral injection consistent with episcleritis (Figure 1), oral ulcers (Figure 2, black arrows), diffuse fine crackles on chest auscultation and testicular tenderness. Laboratory workup was significant for leukocytosis (14,000 cell/mL), hematuria with red blood cell (RBC) casts and serum creatinine level of 2.1 mg/dL, which subsequently rose rapidly to 4.1 mg/dL. Test for cytoplasmic‐stainingantineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (C‐ANCA) was positive. Antiproteinase 3 (PR3) antibodies were also positive. Chest x‐ray showed bilateral pulmonary opacities and sinus computed tomography (CT) scan showed mucosal thickening of the sinuses consistent with sinusitis (Figure 3). Renal biopsy revealed segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis that was pauci‐immune on immunofluorescence staining. The patient was diagnosed with Wegener's granulomatosis with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. He was treated with intravenous corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. The patient's symptoms and acute renal failure resolved with this medical regimen.

Sigmoid Volvulus

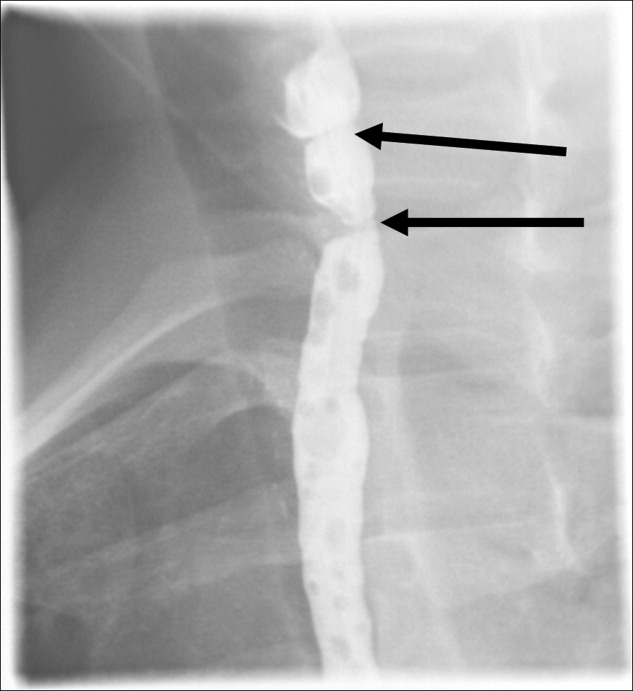

A 63‐year‐old man with multiple medical problems was transferred from a nursing home to the emergency room with progressively worsening diffuse abdominal pain of 3 days' duration. His vital signs were significant for heart rate of 94 beats per minute, blood pressure of 126/84 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Abdominal examination showed diffuse tenderness in all quadrants. Active bowel sounds were heard; guarding or rigidity was absent. Examination of respiratory and cardiovascular system was unremarkable. His laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with left shift. Topogram done for planning computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen (Figure 1) showed the following findings:

-

The dilated sigmoid loops (outlined by linear black arrows) have closely apposed medial walls (arrowheads), giving the appearance of a coffee bean. In addition, the apex of the loop is seen under the left hemidiaphragm.

-

The dilated sigmoid loop is seen to overlap the descending colon (the left flank overlap sign). The lateral margin of descending colon is shown with bold white arrows.

-

The level of convergence of the 2 limbs of the loop is seen to lie below the lumbosacral junction and to the left of the midline (inferior convergence sign, shown by the bold black arrow).

-

The small bowel and large bowel loops are dilated due to distal obstruction and are seen overlapping with the distended sigmoid colon.

-

The rectal gas is not visualized.

These features were suggestive of sigmoid volvulus.

Patients with sigmoid volvulus are often in the sixth to eighth decades of life and frequently have concomitant chronic illnesses, such as cardiac, pulmonary, and renal disease, that significantly influence their outcome.14 Males develop sigmoid volvulus more commonly than do females. In a large series of patients with sigmoid volvulus, 30% had a history of psychiatric disease and 13% were institutionalized at the time of diagnosis.4 Abdominal tenderness is present in less than one‐third of patients with volvulus, and severe pain or signs of peritonitis suggest impending or actual colonic necrosis and perforation.

Plain radiograph of the abdomen is usually diagnostic and reveals a dilated ahaustral sigmoid colon with features of closed‐loop obstruction (bent inner‐tube appearance). The apex of the loop usually extends above the T10 vertebra. The various signs described for sigmoid volvulus on plain radiograph and the sensitivity and specificity for these are given in Table 1.5 A diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus can be made with abdominal radiographs alone in as many as 85% of instances.3 A CT scan helps detect the changes of bowel ischemia and can confirm or provide an alternate diagnosis. A single contrast barium enema examination may be done if signs of bowel ischemia or perforation are absent. This may reveal a mucosal spiral pattern or bird's beak appearance (due to abrupt termination of the barium column) at the site of twist.

| Sign | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Distended ahaustral loop | 94 | 20 |

| Apex under left hemidiaphragm | 88 | 100 |

| Apex of loop above T10 vertebra | 71 | 80 |

| Inferior convergence on the left | 53 | 100 |

| Fulcrum below lumbosacral angle | 65 | 80 |

| Approximation of the medial walls of the sigmoid loop | 88 | 80 |

| Left flank overlap sign | 59 | 100 |

In patients with abdominal films most consistent with a sigmoid volvulus, initial rigid or flexible proctosigmoidoscopy may allow prompt decompression of the volvulus. Early recognition and treatment are necessary to prevent mortality. Placement of a rectal tube for 48 hours may minimize the possibility of early recurrence. Successful reduction of sigmoid volvulus also has been reported with colonoscopy; however, the procedure must be performed carefully with minimal insufflation of air (or preferably carbon dioxide) to minimize the risk of perforation of the distended, inflamed bowel. Endoscopic reduction of sigmoid volvulus alone is associated with a recurrence rate of 25% to 50%.1, 2, 6, 7 Hence, elective sigmoid resection and coloproctostomy, or in medically compromised patients, end colostomy, should follow proctoscopic decompression and mechanical preparation of the bowel. Recurrence rates with this approach are 3% to 6%.1, 2, 7 Patients requiring emergent laparotomy for strangulated sigmoid volvulus require sigmoid resection with end colostomy and a Hartmann pouch. The patient's volvulus was successfully decompressed with colonoscopy. He was offered elective sigmoid resection and coloproctostomy as a definitive therapy, which he declined.

- ,,, et al.Sigmoid volvulus in Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers.Dis Colon Rectum.2000;43:414–418.

- .Review of sigmoid volvulus: history and results of treatment.Dis Colon Rectum.1982;25:494–501.

- ,,, et al.Volvulus of the colon: incidence and mortality.Ann Surg.1985;202:83–92.

- .Review of sigmoid volvulus: clinical patterns and pathogenesis.Dis Colon Rectum.1982;25:823–830.

- ,,,.Significant plain film findings in sigmoid volvulus.Clin Radiol.1994;49:317–319.

- ,.Volvulus of the sigmoid colon.Ann Surg.1973;177:527–537.

- ,,.Endoscopy in colonic volvulus.Ann Surg.1987;206:1–7.

A 63‐year‐old man with multiple medical problems was transferred from a nursing home to the emergency room with progressively worsening diffuse abdominal pain of 3 days' duration. His vital signs were significant for heart rate of 94 beats per minute, blood pressure of 126/84 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Abdominal examination showed diffuse tenderness in all quadrants. Active bowel sounds were heard; guarding or rigidity was absent. Examination of respiratory and cardiovascular system was unremarkable. His laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with left shift. Topogram done for planning computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen (Figure 1) showed the following findings:

-

The dilated sigmoid loops (outlined by linear black arrows) have closely apposed medial walls (arrowheads), giving the appearance of a coffee bean. In addition, the apex of the loop is seen under the left hemidiaphragm.

-

The dilated sigmoid loop is seen to overlap the descending colon (the left flank overlap sign). The lateral margin of descending colon is shown with bold white arrows.

-

The level of convergence of the 2 limbs of the loop is seen to lie below the lumbosacral junction and to the left of the midline (inferior convergence sign, shown by the bold black arrow).

-

The small bowel and large bowel loops are dilated due to distal obstruction and are seen overlapping with the distended sigmoid colon.

-

The rectal gas is not visualized.

These features were suggestive of sigmoid volvulus.

Patients with sigmoid volvulus are often in the sixth to eighth decades of life and frequently have concomitant chronic illnesses, such as cardiac, pulmonary, and renal disease, that significantly influence their outcome.14 Males develop sigmoid volvulus more commonly than do females. In a large series of patients with sigmoid volvulus, 30% had a history of psychiatric disease and 13% were institutionalized at the time of diagnosis.4 Abdominal tenderness is present in less than one‐third of patients with volvulus, and severe pain or signs of peritonitis suggest impending or actual colonic necrosis and perforation.

Plain radiograph of the abdomen is usually diagnostic and reveals a dilated ahaustral sigmoid colon with features of closed‐loop obstruction (bent inner‐tube appearance). The apex of the loop usually extends above the T10 vertebra. The various signs described for sigmoid volvulus on plain radiograph and the sensitivity and specificity for these are given in Table 1.5 A diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus can be made with abdominal radiographs alone in as many as 85% of instances.3 A CT scan helps detect the changes of bowel ischemia and can confirm or provide an alternate diagnosis. A single contrast barium enema examination may be done if signs of bowel ischemia or perforation are absent. This may reveal a mucosal spiral pattern or bird's beak appearance (due to abrupt termination of the barium column) at the site of twist.

| Sign | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Distended ahaustral loop | 94 | 20 |

| Apex under left hemidiaphragm | 88 | 100 |

| Apex of loop above T10 vertebra | 71 | 80 |

| Inferior convergence on the left | 53 | 100 |

| Fulcrum below lumbosacral angle | 65 | 80 |

| Approximation of the medial walls of the sigmoid loop | 88 | 80 |

| Left flank overlap sign | 59 | 100 |

In patients with abdominal films most consistent with a sigmoid volvulus, initial rigid or flexible proctosigmoidoscopy may allow prompt decompression of the volvulus. Early recognition and treatment are necessary to prevent mortality. Placement of a rectal tube for 48 hours may minimize the possibility of early recurrence. Successful reduction of sigmoid volvulus also has been reported with colonoscopy; however, the procedure must be performed carefully with minimal insufflation of air (or preferably carbon dioxide) to minimize the risk of perforation of the distended, inflamed bowel. Endoscopic reduction of sigmoid volvulus alone is associated with a recurrence rate of 25% to 50%.1, 2, 6, 7 Hence, elective sigmoid resection and coloproctostomy, or in medically compromised patients, end colostomy, should follow proctoscopic decompression and mechanical preparation of the bowel. Recurrence rates with this approach are 3% to 6%.1, 2, 7 Patients requiring emergent laparotomy for strangulated sigmoid volvulus require sigmoid resection with end colostomy and a Hartmann pouch. The patient's volvulus was successfully decompressed with colonoscopy. He was offered elective sigmoid resection and coloproctostomy as a definitive therapy, which he declined.

A 63‐year‐old man with multiple medical problems was transferred from a nursing home to the emergency room with progressively worsening diffuse abdominal pain of 3 days' duration. His vital signs were significant for heart rate of 94 beats per minute, blood pressure of 126/84 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Abdominal examination showed diffuse tenderness in all quadrants. Active bowel sounds were heard; guarding or rigidity was absent. Examination of respiratory and cardiovascular system was unremarkable. His laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with left shift. Topogram done for planning computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen (Figure 1) showed the following findings:

-

The dilated sigmoid loops (outlined by linear black arrows) have closely apposed medial walls (arrowheads), giving the appearance of a coffee bean. In addition, the apex of the loop is seen under the left hemidiaphragm.

-

The dilated sigmoid loop is seen to overlap the descending colon (the left flank overlap sign). The lateral margin of descending colon is shown with bold white arrows.

-

The level of convergence of the 2 limbs of the loop is seen to lie below the lumbosacral junction and to the left of the midline (inferior convergence sign, shown by the bold black arrow).

-

The small bowel and large bowel loops are dilated due to distal obstruction and are seen overlapping with the distended sigmoid colon.

-

The rectal gas is not visualized.

These features were suggestive of sigmoid volvulus.

Patients with sigmoid volvulus are often in the sixth to eighth decades of life and frequently have concomitant chronic illnesses, such as cardiac, pulmonary, and renal disease, that significantly influence their outcome.14 Males develop sigmoid volvulus more commonly than do females. In a large series of patients with sigmoid volvulus, 30% had a history of psychiatric disease and 13% were institutionalized at the time of diagnosis.4 Abdominal tenderness is present in less than one‐third of patients with volvulus, and severe pain or signs of peritonitis suggest impending or actual colonic necrosis and perforation.

Plain radiograph of the abdomen is usually diagnostic and reveals a dilated ahaustral sigmoid colon with features of closed‐loop obstruction (bent inner‐tube appearance). The apex of the loop usually extends above the T10 vertebra. The various signs described for sigmoid volvulus on plain radiograph and the sensitivity and specificity for these are given in Table 1.5 A diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus can be made with abdominal radiographs alone in as many as 85% of instances.3 A CT scan helps detect the changes of bowel ischemia and can confirm or provide an alternate diagnosis. A single contrast barium enema examination may be done if signs of bowel ischemia or perforation are absent. This may reveal a mucosal spiral pattern or bird's beak appearance (due to abrupt termination of the barium column) at the site of twist.

| Sign | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Distended ahaustral loop | 94 | 20 |

| Apex under left hemidiaphragm | 88 | 100 |

| Apex of loop above T10 vertebra | 71 | 80 |

| Inferior convergence on the left | 53 | 100 |

| Fulcrum below lumbosacral angle | 65 | 80 |

| Approximation of the medial walls of the sigmoid loop | 88 | 80 |

| Left flank overlap sign | 59 | 100 |

In patients with abdominal films most consistent with a sigmoid volvulus, initial rigid or flexible proctosigmoidoscopy may allow prompt decompression of the volvulus. Early recognition and treatment are necessary to prevent mortality. Placement of a rectal tube for 48 hours may minimize the possibility of early recurrence. Successful reduction of sigmoid volvulus also has been reported with colonoscopy; however, the procedure must be performed carefully with minimal insufflation of air (or preferably carbon dioxide) to minimize the risk of perforation of the distended, inflamed bowel. Endoscopic reduction of sigmoid volvulus alone is associated with a recurrence rate of 25% to 50%.1, 2, 6, 7 Hence, elective sigmoid resection and coloproctostomy, or in medically compromised patients, end colostomy, should follow proctoscopic decompression and mechanical preparation of the bowel. Recurrence rates with this approach are 3% to 6%.1, 2, 7 Patients requiring emergent laparotomy for strangulated sigmoid volvulus require sigmoid resection with end colostomy and a Hartmann pouch. The patient's volvulus was successfully decompressed with colonoscopy. He was offered elective sigmoid resection and coloproctostomy as a definitive therapy, which he declined.

- ,,, et al.Sigmoid volvulus in Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers.Dis Colon Rectum.2000;43:414–418.

- .Review of sigmoid volvulus: history and results of treatment.Dis Colon Rectum.1982;25:494–501.

- ,,, et al.Volvulus of the colon: incidence and mortality.Ann Surg.1985;202:83–92.

- .Review of sigmoid volvulus: clinical patterns and pathogenesis.Dis Colon Rectum.1982;25:823–830.

- ,,,.Significant plain film findings in sigmoid volvulus.Clin Radiol.1994;49:317–319.

- ,.Volvulus of the sigmoid colon.Ann Surg.1973;177:527–537.

- ,,.Endoscopy in colonic volvulus.Ann Surg.1987;206:1–7.

- ,,, et al.Sigmoid volvulus in Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers.Dis Colon Rectum.2000;43:414–418.

- .Review of sigmoid volvulus: history and results of treatment.Dis Colon Rectum.1982;25:494–501.

- ,,, et al.Volvulus of the colon: incidence and mortality.Ann Surg.1985;202:83–92.

- .Review of sigmoid volvulus: clinical patterns and pathogenesis.Dis Colon Rectum.1982;25:823–830.

- ,,,.Significant plain film findings in sigmoid volvulus.Clin Radiol.1994;49:317–319.

- ,.Volvulus of the sigmoid colon.Ann Surg.1973;177:527–537.

- ,,.Endoscopy in colonic volvulus.Ann Surg.1987;206:1–7.

More Than a Plantar Wart

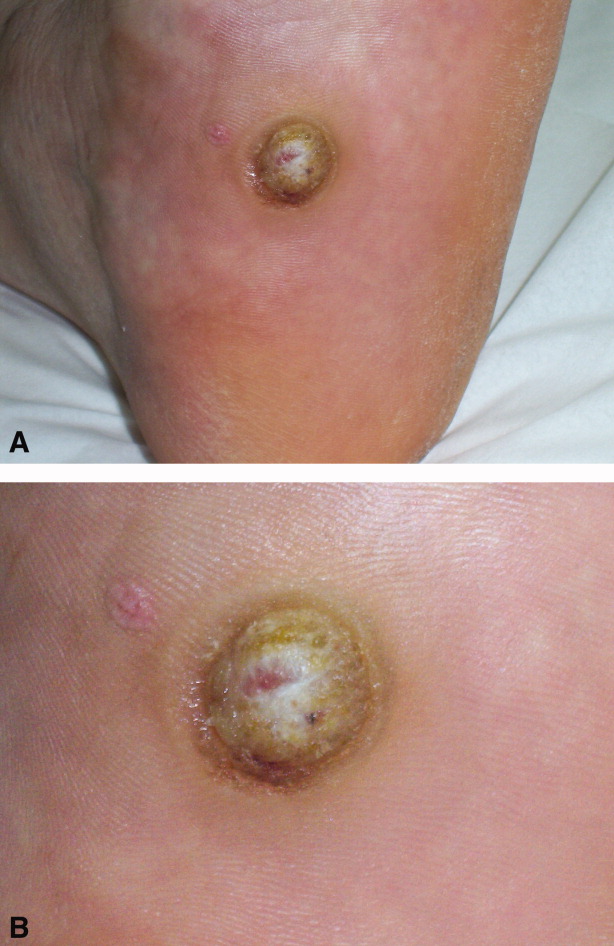

A 56‐year‐old man with a 1‐year history of a verrucous nodule on his left foot presented to our department due to the unexpected growth. He was previously diagnosed with a plantar wart so underwent salicylic ointment application, liquid‐nitrogen cryotherapy and electrocoagulation, with no improvement of the condition.

Clinical examination revealed a 22‐mm flesh‐colored, centrally hypopigmented and ulcerated, exophytic nodule, with an adjacent 5 4 mm pink papule with telangiectasia (Figure 1A and B).

Histological examination established the diagnosis of ulcerated amelanotic malignant melanoma (Clark's level IV, Breslow's thickness of 3 mm) with a satellite nodule. Radical inguinal lymph node dissection yielded a negative result. Total‐body computed tomographic scan was unremarkable. One‐year follow‐up revealed no metastatic disease.

Melanoma of the foot accounts for 3% to 15% of all cutaneous melanoma. In acral skin, melanomas tend to have unusual clinical appearances. Amelanotic variants may masquerade as several benign hyperkeratotic dermatoses (warts, calluses, fungal disorders, foreign bodies, moles, keratoacanthomas, hematomas) increasing misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment rates, with a poorer patient outcome.1 Pedal lesions require close observation and biopsy when diagnostic uncertainty exists or when therapeutic interventions fail.

- ,,,,,.Acral lentiginous melanoma mimicking benign disease: the Emory experience.J Am Acad Dermatol.2003;48:183–188.

A 56‐year‐old man with a 1‐year history of a verrucous nodule on his left foot presented to our department due to the unexpected growth. He was previously diagnosed with a plantar wart so underwent salicylic ointment application, liquid‐nitrogen cryotherapy and electrocoagulation, with no improvement of the condition.

Clinical examination revealed a 22‐mm flesh‐colored, centrally hypopigmented and ulcerated, exophytic nodule, with an adjacent 5 4 mm pink papule with telangiectasia (Figure 1A and B).

Histological examination established the diagnosis of ulcerated amelanotic malignant melanoma (Clark's level IV, Breslow's thickness of 3 mm) with a satellite nodule. Radical inguinal lymph node dissection yielded a negative result. Total‐body computed tomographic scan was unremarkable. One‐year follow‐up revealed no metastatic disease.

Melanoma of the foot accounts for 3% to 15% of all cutaneous melanoma. In acral skin, melanomas tend to have unusual clinical appearances. Amelanotic variants may masquerade as several benign hyperkeratotic dermatoses (warts, calluses, fungal disorders, foreign bodies, moles, keratoacanthomas, hematomas) increasing misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment rates, with a poorer patient outcome.1 Pedal lesions require close observation and biopsy when diagnostic uncertainty exists or when therapeutic interventions fail.

A 56‐year‐old man with a 1‐year history of a verrucous nodule on his left foot presented to our department due to the unexpected growth. He was previously diagnosed with a plantar wart so underwent salicylic ointment application, liquid‐nitrogen cryotherapy and electrocoagulation, with no improvement of the condition.

Clinical examination revealed a 22‐mm flesh‐colored, centrally hypopigmented and ulcerated, exophytic nodule, with an adjacent 5 4 mm pink papule with telangiectasia (Figure 1A and B).

Histological examination established the diagnosis of ulcerated amelanotic malignant melanoma (Clark's level IV, Breslow's thickness of 3 mm) with a satellite nodule. Radical inguinal lymph node dissection yielded a negative result. Total‐body computed tomographic scan was unremarkable. One‐year follow‐up revealed no metastatic disease.

Melanoma of the foot accounts for 3% to 15% of all cutaneous melanoma. In acral skin, melanomas tend to have unusual clinical appearances. Amelanotic variants may masquerade as several benign hyperkeratotic dermatoses (warts, calluses, fungal disorders, foreign bodies, moles, keratoacanthomas, hematomas) increasing misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment rates, with a poorer patient outcome.1 Pedal lesions require close observation and biopsy when diagnostic uncertainty exists or when therapeutic interventions fail.

- ,,,,,.Acral lentiginous melanoma mimicking benign disease: the Emory experience.J Am Acad Dermatol.2003;48:183–188.

- ,,,,,.Acral lentiginous melanoma mimicking benign disease: the Emory experience.J Am Acad Dermatol.2003;48:183–188.

Pneumothorax in a Patient With COPD

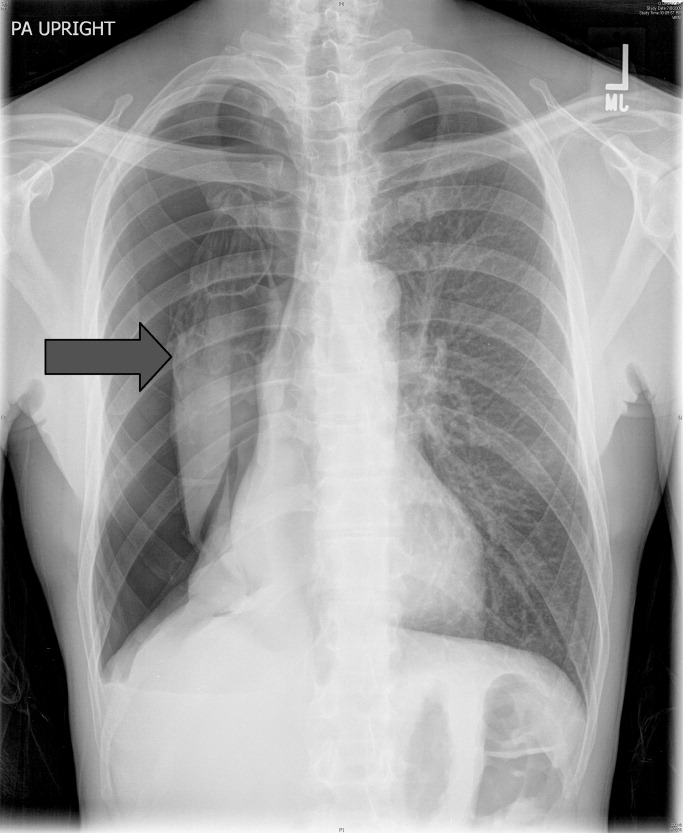

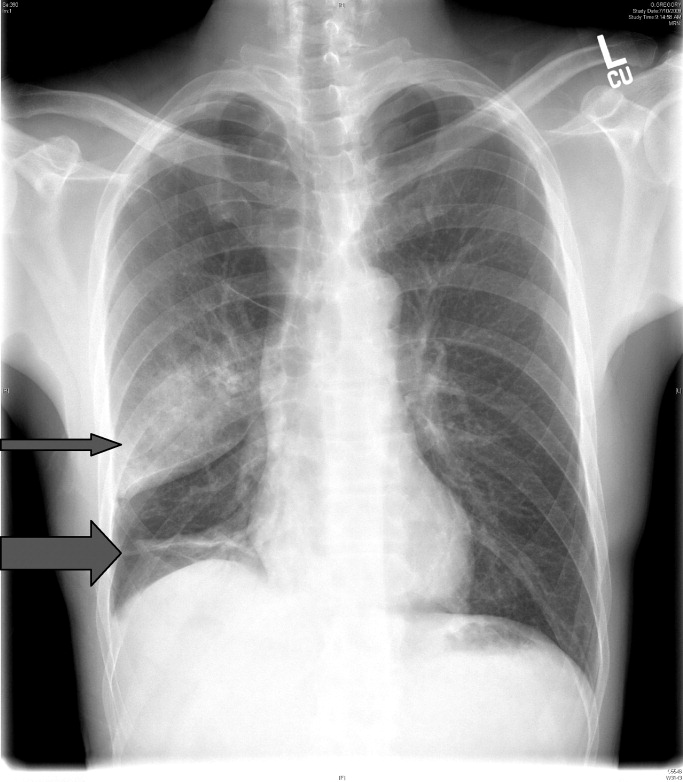

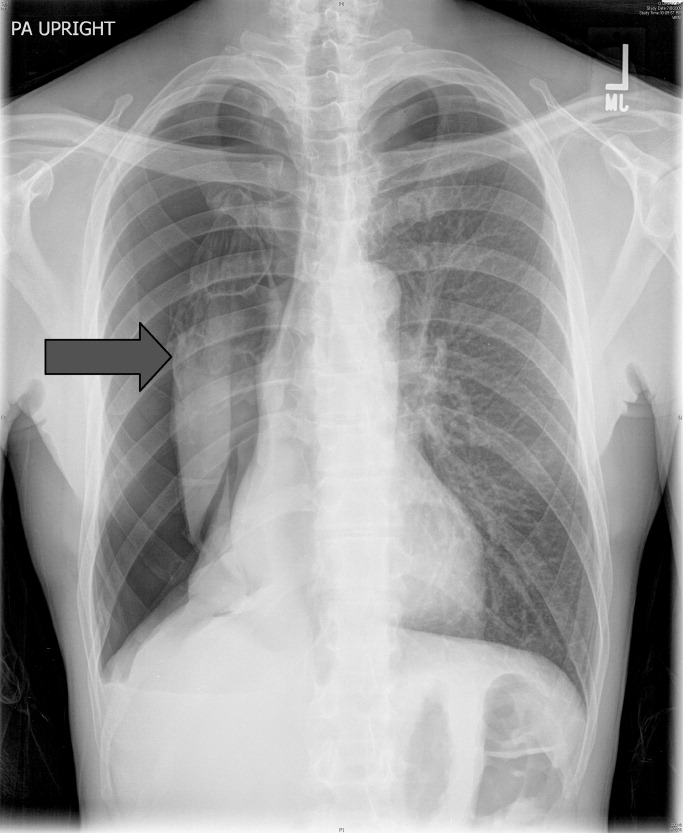

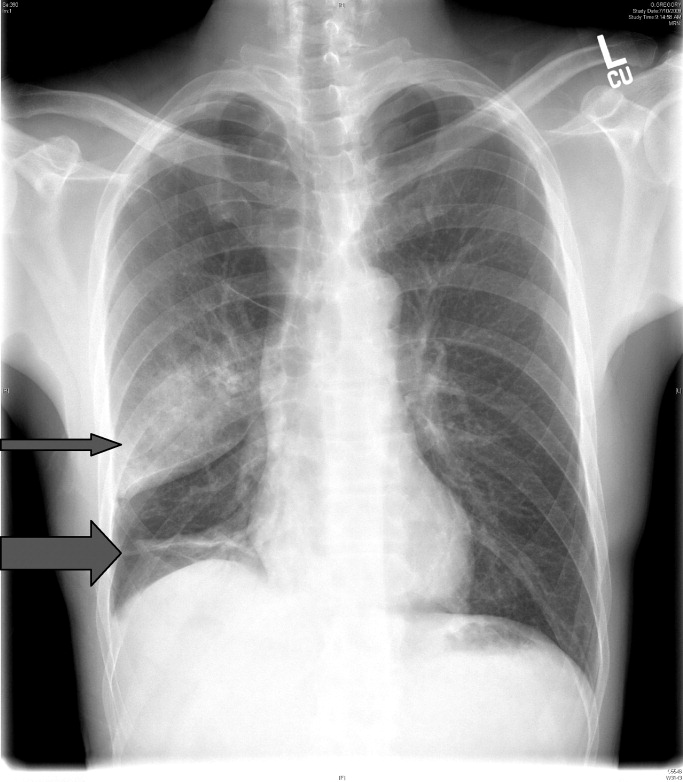

A 53‐year‐old man with a history of heavy tobacco use presented with shortness of breath. Eight days prior to his presentation he was diagnosed with multiple rib fractures after suffering an assault. Since then he had developed dyspnea and a nonproductive cough. A chest x‐ray revealed a large pneumothorax on the right with approximately 80% volume loss (arrow, Figure 1).

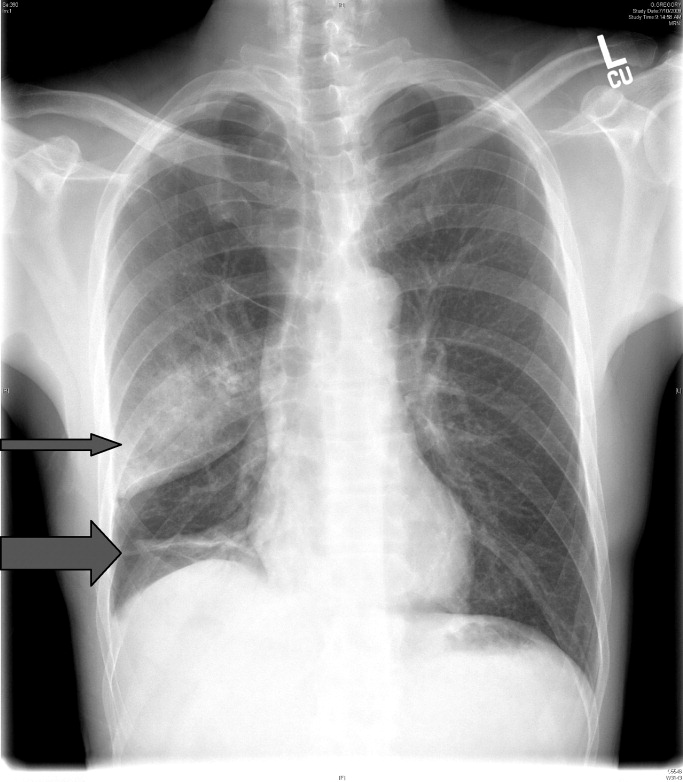

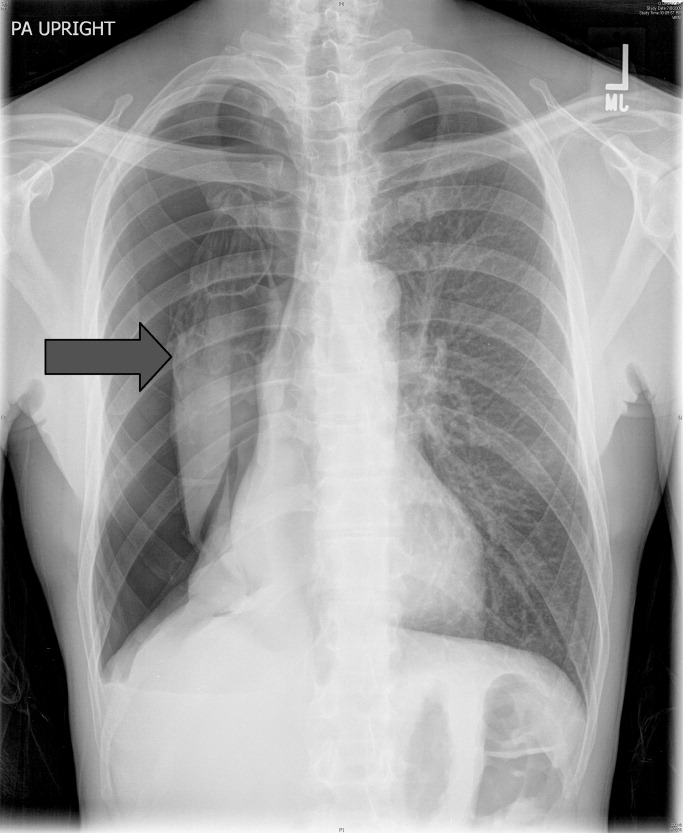

Tube thoracostomy was performed. Repeat chest x‐ray showed that the pneumothorax had resolved, revealing a consolidation likely caused by either reexpansion pulmonary edema1, 2 or, given its location in the superior segment of the right lower lobe, aspiration pneumonia (thin arrow, Figure 2). Also seen in the x‐ray is an old scar (thick arrow, Figure 2) and apical bullous changes with hyperinflated lungs suggestive of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

DISCUSSION

Pneumothorax is a common complication of blunt trauma and rib fractures.3 While the patient did not have a preceding diagnosis of COPD, his extensive smoking history and his radiographic changes are consistent with COPD, which is a risk factor for pneumothroax. Secondary pneumothorax is defined as pneumothorax that occurs as a complication of underlying lung disease and is most commonly associated with COPD,4 with rupturing of apical blebs as the proposed mechanism. This patient suffered a pneumothorax due to trauma, but given his COPD he is at increased risk for developing spontaneous pneumothorax in the future.

- .Reexpansion pulmonary edema.Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.2008;14(4):205–209.

- ,.Images in clinical medicine. Reexpansion pulmonary edema after treatment of pneumothorax.N Engl J Med.2006;354(19):2046.

- ,,.Profile of chest trauma in a level I trauma center.J Trauma.2004;57(3):576–581.

- ,,,.Factors related to recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax.Respirology.2005;10(3):378–384.

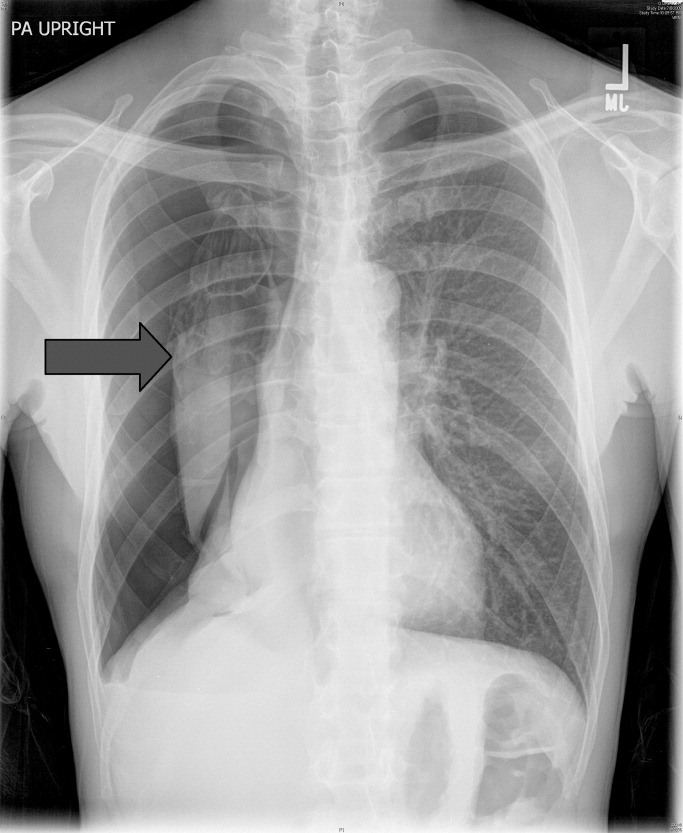

A 53‐year‐old man with a history of heavy tobacco use presented with shortness of breath. Eight days prior to his presentation he was diagnosed with multiple rib fractures after suffering an assault. Since then he had developed dyspnea and a nonproductive cough. A chest x‐ray revealed a large pneumothorax on the right with approximately 80% volume loss (arrow, Figure 1).

Tube thoracostomy was performed. Repeat chest x‐ray showed that the pneumothorax had resolved, revealing a consolidation likely caused by either reexpansion pulmonary edema1, 2 or, given its location in the superior segment of the right lower lobe, aspiration pneumonia (thin arrow, Figure 2). Also seen in the x‐ray is an old scar (thick arrow, Figure 2) and apical bullous changes with hyperinflated lungs suggestive of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

DISCUSSION

Pneumothorax is a common complication of blunt trauma and rib fractures.3 While the patient did not have a preceding diagnosis of COPD, his extensive smoking history and his radiographic changes are consistent with COPD, which is a risk factor for pneumothroax. Secondary pneumothorax is defined as pneumothorax that occurs as a complication of underlying lung disease and is most commonly associated with COPD,4 with rupturing of apical blebs as the proposed mechanism. This patient suffered a pneumothorax due to trauma, but given his COPD he is at increased risk for developing spontaneous pneumothorax in the future.

A 53‐year‐old man with a history of heavy tobacco use presented with shortness of breath. Eight days prior to his presentation he was diagnosed with multiple rib fractures after suffering an assault. Since then he had developed dyspnea and a nonproductive cough. A chest x‐ray revealed a large pneumothorax on the right with approximately 80% volume loss (arrow, Figure 1).

Tube thoracostomy was performed. Repeat chest x‐ray showed that the pneumothorax had resolved, revealing a consolidation likely caused by either reexpansion pulmonary edema1, 2 or, given its location in the superior segment of the right lower lobe, aspiration pneumonia (thin arrow, Figure 2). Also seen in the x‐ray is an old scar (thick arrow, Figure 2) and apical bullous changes with hyperinflated lungs suggestive of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

DISCUSSION

Pneumothorax is a common complication of blunt trauma and rib fractures.3 While the patient did not have a preceding diagnosis of COPD, his extensive smoking history and his radiographic changes are consistent with COPD, which is a risk factor for pneumothroax. Secondary pneumothorax is defined as pneumothorax that occurs as a complication of underlying lung disease and is most commonly associated with COPD,4 with rupturing of apical blebs as the proposed mechanism. This patient suffered a pneumothorax due to trauma, but given his COPD he is at increased risk for developing spontaneous pneumothorax in the future.

- .Reexpansion pulmonary edema.Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.2008;14(4):205–209.

- ,.Images in clinical medicine. Reexpansion pulmonary edema after treatment of pneumothorax.N Engl J Med.2006;354(19):2046.

- ,,.Profile of chest trauma in a level I trauma center.J Trauma.2004;57(3):576–581.

- ,,,.Factors related to recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax.Respirology.2005;10(3):378–384.

- .Reexpansion pulmonary edema.Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.2008;14(4):205–209.

- ,.Images in clinical medicine. Reexpansion pulmonary edema after treatment of pneumothorax.N Engl J Med.2006;354(19):2046.

- ,,.Profile of chest trauma in a level I trauma center.J Trauma.2004;57(3):576–581.

- ,,,.Factors related to recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax.Respirology.2005;10(3):378–384.

Positional Atrial Flutter?

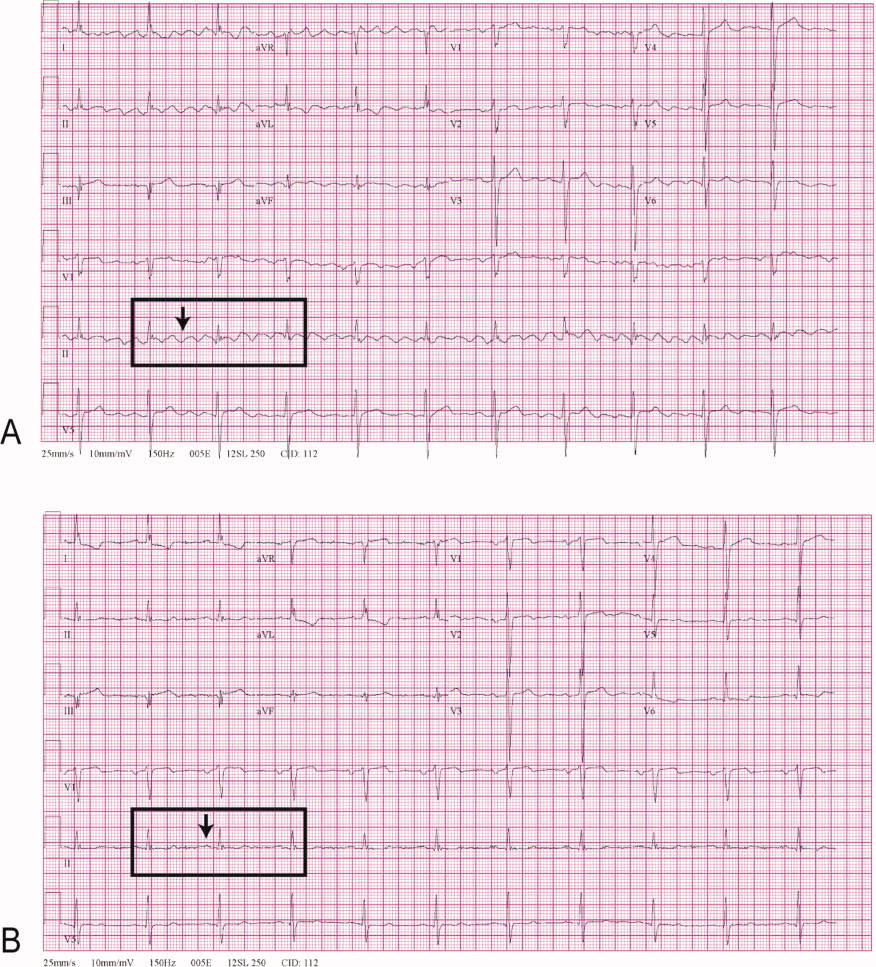

A 68‐year‐old man with a history of congestive heart failure and hypertension presented to the emergency department with fatigue and dyspnea of 3 weeks duration. Physical examination was consistent with heart failure. In addition, a right upper extremity resting tremor was noticed. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed an atrial flutter with a conduction ratio of 4:1 (Figure 1A). He denied palpitations or a previous history of atrial flutter/fibrillation. Unlike typical atrial flutter, these flutter like waves were distinctly absent in lead III, the only limb lead not connected to the right arm.

While holding the patient's right arm to control the tremor, a second ECG tracing was obtained. As expected the flutter like waves disappeared (Figure 1B). These ECG findings were attributed to the patient's tremor. A neurological consultation established a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. His congestive heart failure (CHF) was treated with increasing diuretics and appropriate treatment for Parkinson's disease was initiated.

A 68‐year‐old man with a history of congestive heart failure and hypertension presented to the emergency department with fatigue and dyspnea of 3 weeks duration. Physical examination was consistent with heart failure. In addition, a right upper extremity resting tremor was noticed. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed an atrial flutter with a conduction ratio of 4:1 (Figure 1A). He denied palpitations or a previous history of atrial flutter/fibrillation. Unlike typical atrial flutter, these flutter like waves were distinctly absent in lead III, the only limb lead not connected to the right arm.

While holding the patient's right arm to control the tremor, a second ECG tracing was obtained. As expected the flutter like waves disappeared (Figure 1B). These ECG findings were attributed to the patient's tremor. A neurological consultation established a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. His congestive heart failure (CHF) was treated with increasing diuretics and appropriate treatment for Parkinson's disease was initiated.

A 68‐year‐old man with a history of congestive heart failure and hypertension presented to the emergency department with fatigue and dyspnea of 3 weeks duration. Physical examination was consistent with heart failure. In addition, a right upper extremity resting tremor was noticed. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed an atrial flutter with a conduction ratio of 4:1 (Figure 1A). He denied palpitations or a previous history of atrial flutter/fibrillation. Unlike typical atrial flutter, these flutter like waves were distinctly absent in lead III, the only limb lead not connected to the right arm.

While holding the patient's right arm to control the tremor, a second ECG tracing was obtained. As expected the flutter like waves disappeared (Figure 1B). These ECG findings were attributed to the patient's tremor. A neurological consultation established a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. His congestive heart failure (CHF) was treated with increasing diuretics and appropriate treatment for Parkinson's disease was initiated.

Self‐Medication and Intractable Cough

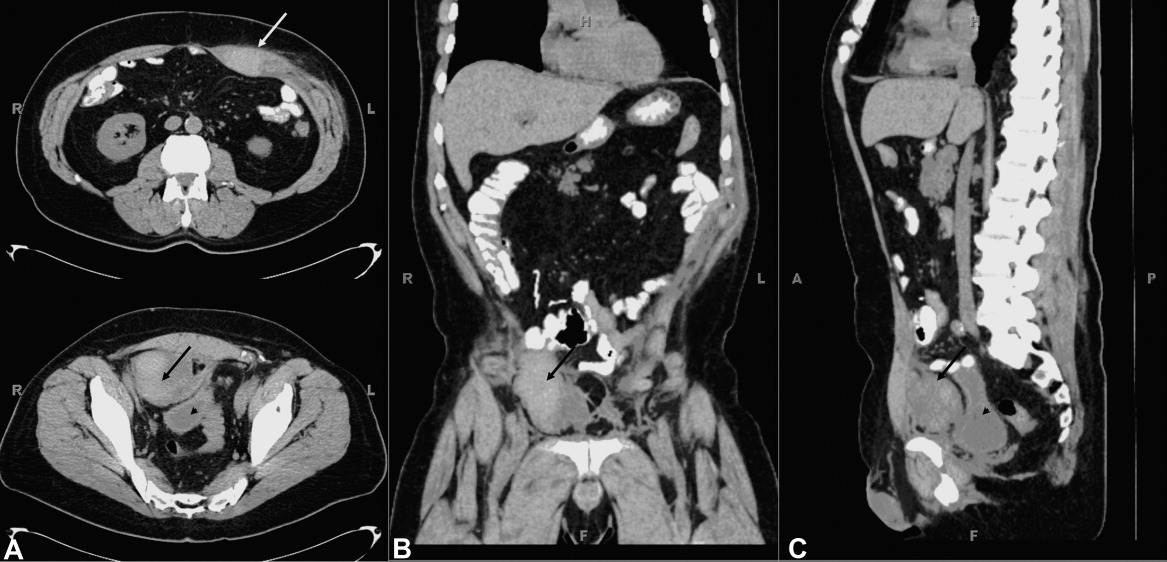

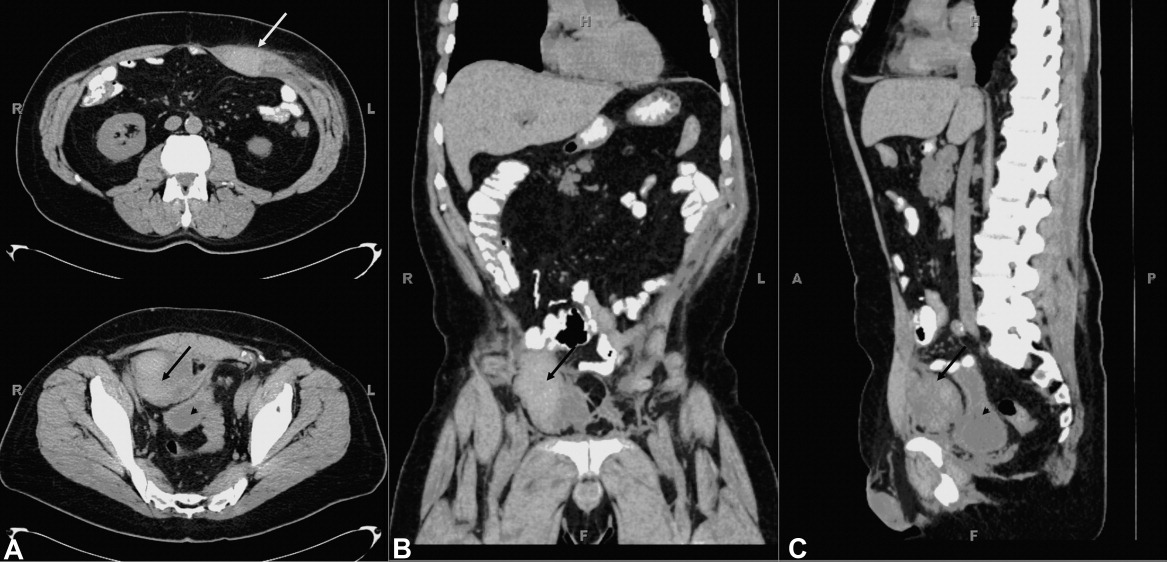

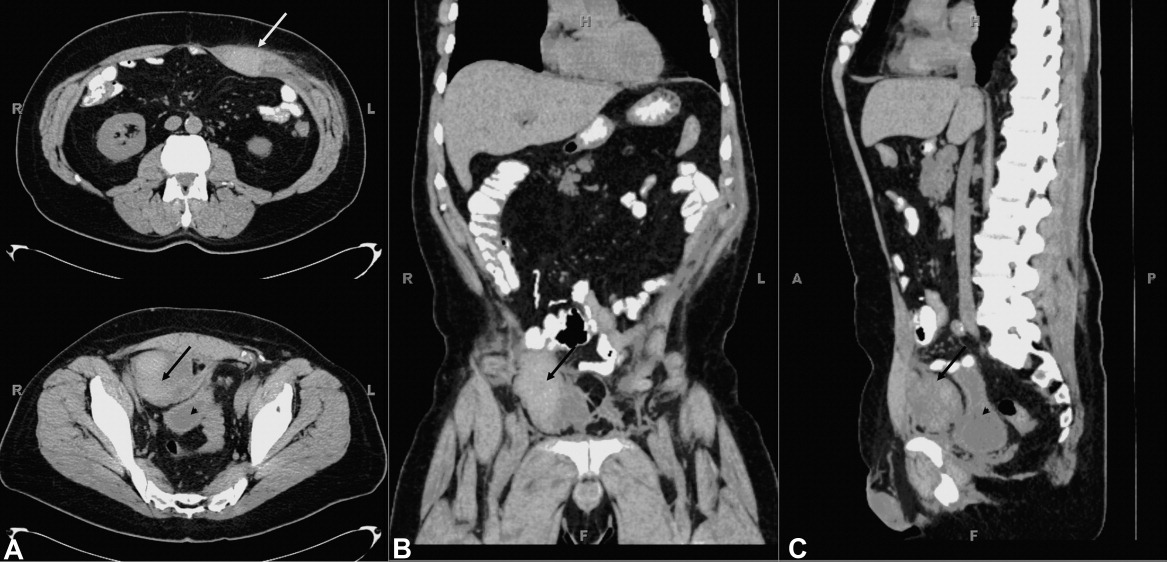

A 60 year old man presented with a 1‐month history of severe, dry cough. His medical history is significant for lymphoma (4 years), bone marrow transplant (8 months), stable graft‐vs.‐host disease, with a negative bleeding history. He self‐medicated his cough with 6 to 8 tablets daily of an analgesic containing 250 mg acetaminophen, 65 mg caffeine, and 250 mg aspirin. He developed severe stabbing pain in his right lower quadrant exacerbated by coughing. Several days later he developed severe pain of his left upper abdomen. The abdominal wall was tender. Laboratory tests revealed a hematocrit of 31%, platelet count of 246,000, international normalized prothrombin ratio of 1.0, and activated partial thromboplastin ratio of 0.8. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) without contrast revealed 2 rectus sheath hematomas. A 4‐cm 2‐cm 2‐cm collection consistent with hematoma was contained within the left rectus abdominis muscle sheath above the level of the umbilicus (white arrow, Figure 1A, top). An additional collection measuring 6 cm 6 cm 4 cm was present below the umbilicus and between the posterior aspect of the right rectus abdominus muscle (black arrows, Figure 1A bottom; B and C) and the anterior surface of the bladder (arrowhead, Figure 1A and C). Aspirin was stopped and he was started on moxifloxacin for pneumonia. He was discharged 3 days later with improved cough resulting in improved pain control.

Rectus sheath hematoma may be contained with the fascia when above the arcuate line, located about 5 cm below the umbilicus. Below the arcuate line a rectus sheath hematoma may dissect posteriorly into the prevesicular space of Retzius. Both are seen in this case. Rectus sheath hematoma are usually associated with cough in the setting of coagulopathy, and may require transfusion or surgical evacuation. High dose aspirin, in this case up to 2000 mg per day, may lead to hemorrhage associated with intractable coughing.

A 60 year old man presented with a 1‐month history of severe, dry cough. His medical history is significant for lymphoma (4 years), bone marrow transplant (8 months), stable graft‐vs.‐host disease, with a negative bleeding history. He self‐medicated his cough with 6 to 8 tablets daily of an analgesic containing 250 mg acetaminophen, 65 mg caffeine, and 250 mg aspirin. He developed severe stabbing pain in his right lower quadrant exacerbated by coughing. Several days later he developed severe pain of his left upper abdomen. The abdominal wall was tender. Laboratory tests revealed a hematocrit of 31%, platelet count of 246,000, international normalized prothrombin ratio of 1.0, and activated partial thromboplastin ratio of 0.8. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) without contrast revealed 2 rectus sheath hematomas. A 4‐cm 2‐cm 2‐cm collection consistent with hematoma was contained within the left rectus abdominis muscle sheath above the level of the umbilicus (white arrow, Figure 1A, top). An additional collection measuring 6 cm 6 cm 4 cm was present below the umbilicus and between the posterior aspect of the right rectus abdominus muscle (black arrows, Figure 1A bottom; B and C) and the anterior surface of the bladder (arrowhead, Figure 1A and C). Aspirin was stopped and he was started on moxifloxacin for pneumonia. He was discharged 3 days later with improved cough resulting in improved pain control.

Rectus sheath hematoma may be contained with the fascia when above the arcuate line, located about 5 cm below the umbilicus. Below the arcuate line a rectus sheath hematoma may dissect posteriorly into the prevesicular space of Retzius. Both are seen in this case. Rectus sheath hematoma are usually associated with cough in the setting of coagulopathy, and may require transfusion or surgical evacuation. High dose aspirin, in this case up to 2000 mg per day, may lead to hemorrhage associated with intractable coughing.

A 60 year old man presented with a 1‐month history of severe, dry cough. His medical history is significant for lymphoma (4 years), bone marrow transplant (8 months), stable graft‐vs.‐host disease, with a negative bleeding history. He self‐medicated his cough with 6 to 8 tablets daily of an analgesic containing 250 mg acetaminophen, 65 mg caffeine, and 250 mg aspirin. He developed severe stabbing pain in his right lower quadrant exacerbated by coughing. Several days later he developed severe pain of his left upper abdomen. The abdominal wall was tender. Laboratory tests revealed a hematocrit of 31%, platelet count of 246,000, international normalized prothrombin ratio of 1.0, and activated partial thromboplastin ratio of 0.8. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) without contrast revealed 2 rectus sheath hematomas. A 4‐cm 2‐cm 2‐cm collection consistent with hematoma was contained within the left rectus abdominis muscle sheath above the level of the umbilicus (white arrow, Figure 1A, top). An additional collection measuring 6 cm 6 cm 4 cm was present below the umbilicus and between the posterior aspect of the right rectus abdominus muscle (black arrows, Figure 1A bottom; B and C) and the anterior surface of the bladder (arrowhead, Figure 1A and C). Aspirin was stopped and he was started on moxifloxacin for pneumonia. He was discharged 3 days later with improved cough resulting in improved pain control.

Rectus sheath hematoma may be contained with the fascia when above the arcuate line, located about 5 cm below the umbilicus. Below the arcuate line a rectus sheath hematoma may dissect posteriorly into the prevesicular space of Retzius. Both are seen in this case. Rectus sheath hematoma are usually associated with cough in the setting of coagulopathy, and may require transfusion or surgical evacuation. High dose aspirin, in this case up to 2000 mg per day, may lead to hemorrhage associated with intractable coughing.

Incisional Iliac Hernia

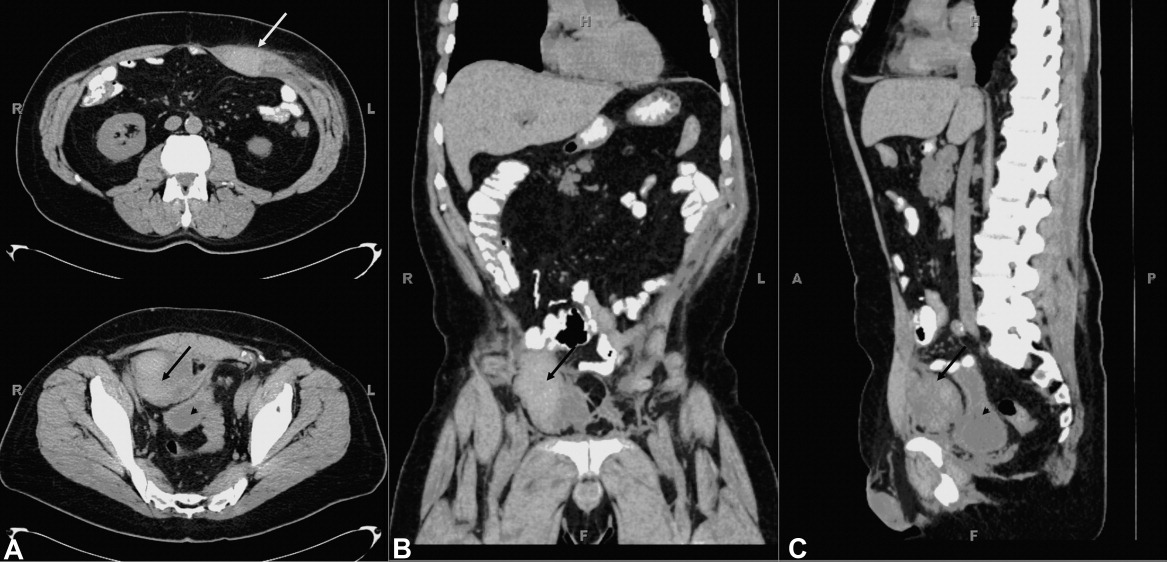

A 61‐year‐old woman presented with 1 month of abdominal pain and bowel irregularity. Physical examination was normal. Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a nonincarcerated hernia of the ascending colon through a 25‐mm bony defect in the superior aspect of the right iliac crest (Figure 1)a defect created 16 years prior when iliac crest bone graft harvest was performed during subtalar fusion. An open surgical approach was employed to reduce the hernia and close the defect with mesh. Her postoperative course was unremarkable. Her symptoms resolved entirely.

The iliac crest is the site utilized most frequently in orthopedic surgery for bone graft harvest. The literature suggests that up to 5% of these procedures may be complicated by symptomatic herniation of abdominal contents.1 Other procedural complications include: donor site pain, nerve injury (commonly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, manifesting as meralgia paresthetica), vascular disruption (including superior gluteal and lumbar arteries), hematoma, visible deformity, abnormal gait, and stress fracture.2, 3 Advanced age, obesity, muscular weakness, larger defect size, and full‐thickness harvest have been identified as risk factors.4 The hernia often presents as a soft‐tissue mass originating at the defect site, which may become more pronounced with cough. Auscultation over the area may reveal bowel sounds. The spectrum of associated abdominal symptoms ranges from mild discomfort to colicky pain and distention;3 up to 16% of patients present with acute signs of intestinal obstruction.1 Iliac herniation may be prevented by harvest of a partial thickness graft, whenever possible. Selective removal of bone from the anterior or posterior crest, rather than the middle, may also decrease the risk.4 Clinicians caring for patients with a history of iliac crest bone graft harvest should be familiar with this complication and consider prompt radiologic imaging when investigating new or unexplained abdominal symptoms.

- ,,,.Hernia through iliac crest defects.Int Orthop.1995;19:367–369.

- ,,.Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: a review of complications and techniques.Spine.1989;14:1324–1331.

- ,,,.Hernia through an iliac crest bone graft site: report of a case and review of the literature.Bull Hosp Jt Dis.2006;63:166–168.

- ,.Incisional hernia through iliac crest defects.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.1989;108:383–385.

A 61‐year‐old woman presented with 1 month of abdominal pain and bowel irregularity. Physical examination was normal. Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a nonincarcerated hernia of the ascending colon through a 25‐mm bony defect in the superior aspect of the right iliac crest (Figure 1)a defect created 16 years prior when iliac crest bone graft harvest was performed during subtalar fusion. An open surgical approach was employed to reduce the hernia and close the defect with mesh. Her postoperative course was unremarkable. Her symptoms resolved entirely.

The iliac crest is the site utilized most frequently in orthopedic surgery for bone graft harvest. The literature suggests that up to 5% of these procedures may be complicated by symptomatic herniation of abdominal contents.1 Other procedural complications include: donor site pain, nerve injury (commonly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, manifesting as meralgia paresthetica), vascular disruption (including superior gluteal and lumbar arteries), hematoma, visible deformity, abnormal gait, and stress fracture.2, 3 Advanced age, obesity, muscular weakness, larger defect size, and full‐thickness harvest have been identified as risk factors.4 The hernia often presents as a soft‐tissue mass originating at the defect site, which may become more pronounced with cough. Auscultation over the area may reveal bowel sounds. The spectrum of associated abdominal symptoms ranges from mild discomfort to colicky pain and distention;3 up to 16% of patients present with acute signs of intestinal obstruction.1 Iliac herniation may be prevented by harvest of a partial thickness graft, whenever possible. Selective removal of bone from the anterior or posterior crest, rather than the middle, may also decrease the risk.4 Clinicians caring for patients with a history of iliac crest bone graft harvest should be familiar with this complication and consider prompt radiologic imaging when investigating new or unexplained abdominal symptoms.

A 61‐year‐old woman presented with 1 month of abdominal pain and bowel irregularity. Physical examination was normal. Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a nonincarcerated hernia of the ascending colon through a 25‐mm bony defect in the superior aspect of the right iliac crest (Figure 1)a defect created 16 years prior when iliac crest bone graft harvest was performed during subtalar fusion. An open surgical approach was employed to reduce the hernia and close the defect with mesh. Her postoperative course was unremarkable. Her symptoms resolved entirely.

The iliac crest is the site utilized most frequently in orthopedic surgery for bone graft harvest. The literature suggests that up to 5% of these procedures may be complicated by symptomatic herniation of abdominal contents.1 Other procedural complications include: donor site pain, nerve injury (commonly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, manifesting as meralgia paresthetica), vascular disruption (including superior gluteal and lumbar arteries), hematoma, visible deformity, abnormal gait, and stress fracture.2, 3 Advanced age, obesity, muscular weakness, larger defect size, and full‐thickness harvest have been identified as risk factors.4 The hernia often presents as a soft‐tissue mass originating at the defect site, which may become more pronounced with cough. Auscultation over the area may reveal bowel sounds. The spectrum of associated abdominal symptoms ranges from mild discomfort to colicky pain and distention;3 up to 16% of patients present with acute signs of intestinal obstruction.1 Iliac herniation may be prevented by harvest of a partial thickness graft, whenever possible. Selective removal of bone from the anterior or posterior crest, rather than the middle, may also decrease the risk.4 Clinicians caring for patients with a history of iliac crest bone graft harvest should be familiar with this complication and consider prompt radiologic imaging when investigating new or unexplained abdominal symptoms.

- ,,,.Hernia through iliac crest defects.Int Orthop.1995;19:367–369.

- ,,.Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: a review of complications and techniques.Spine.1989;14:1324–1331.

- ,,,.Hernia through an iliac crest bone graft site: report of a case and review of the literature.Bull Hosp Jt Dis.2006;63:166–168.

- ,.Incisional hernia through iliac crest defects.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.1989;108:383–385.

- ,,,.Hernia through iliac crest defects.Int Orthop.1995;19:367–369.

- ,,.Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: a review of complications and techniques.Spine.1989;14:1324–1331.

- ,,,.Hernia through an iliac crest bone graft site: report of a case and review of the literature.Bull Hosp Jt Dis.2006;63:166–168.

- ,.Incisional hernia through iliac crest defects.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.1989;108:383–385.