User login

Electrical Alternans and Pulsus Paradoxus

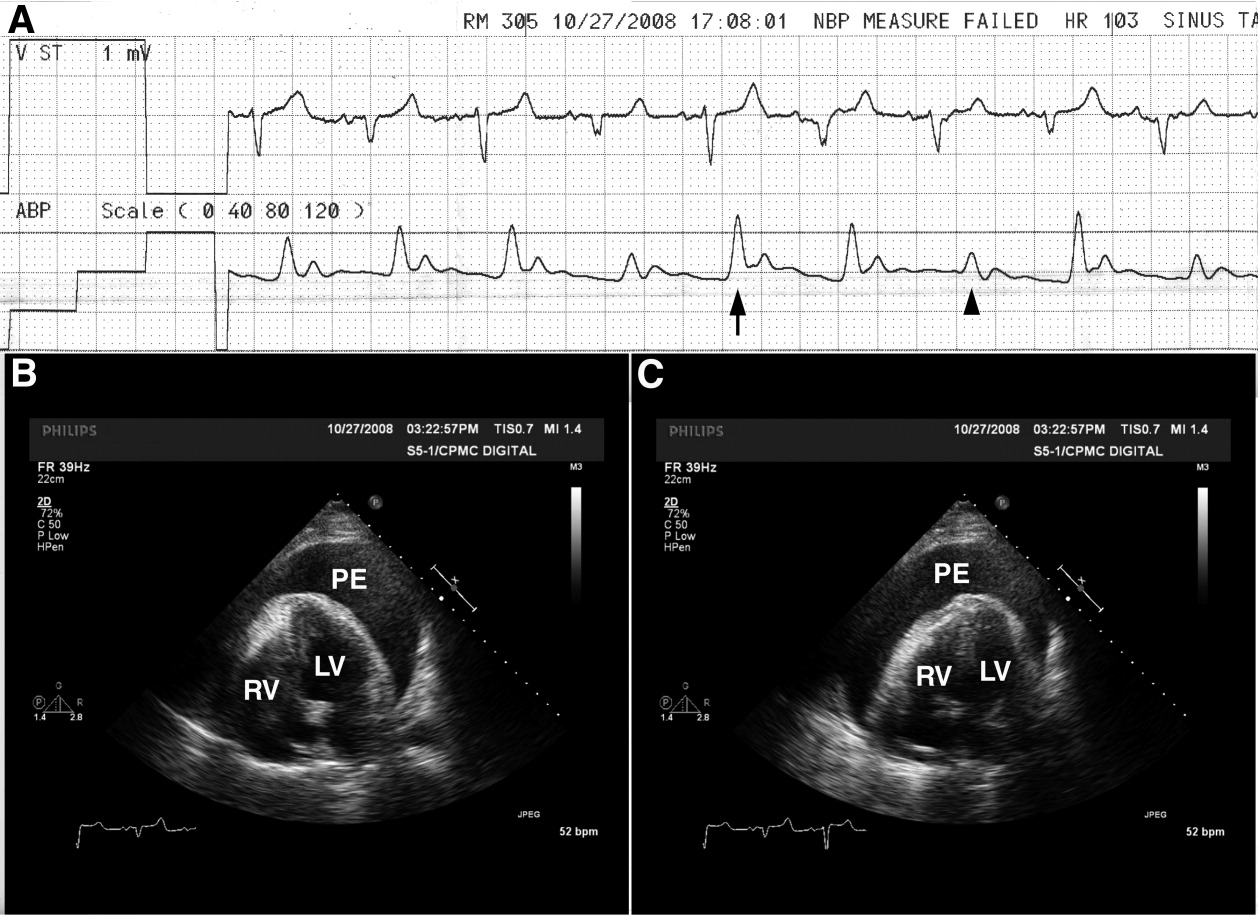

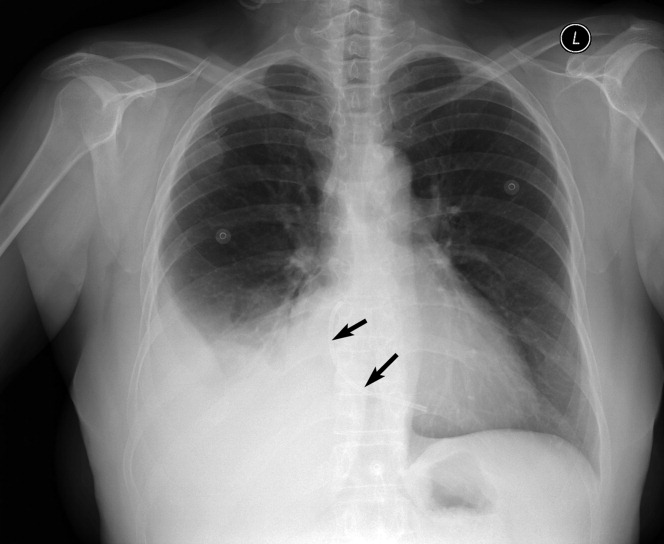

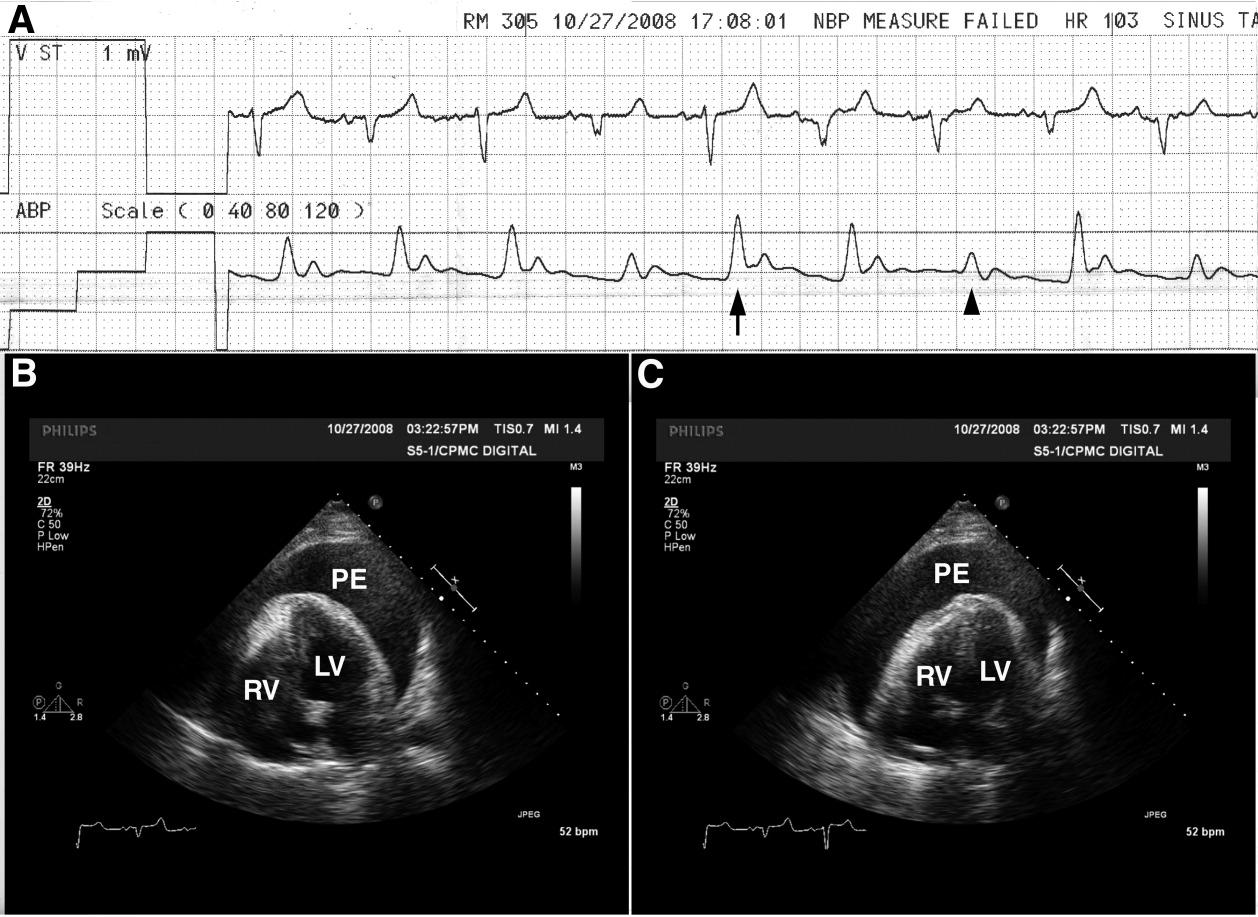

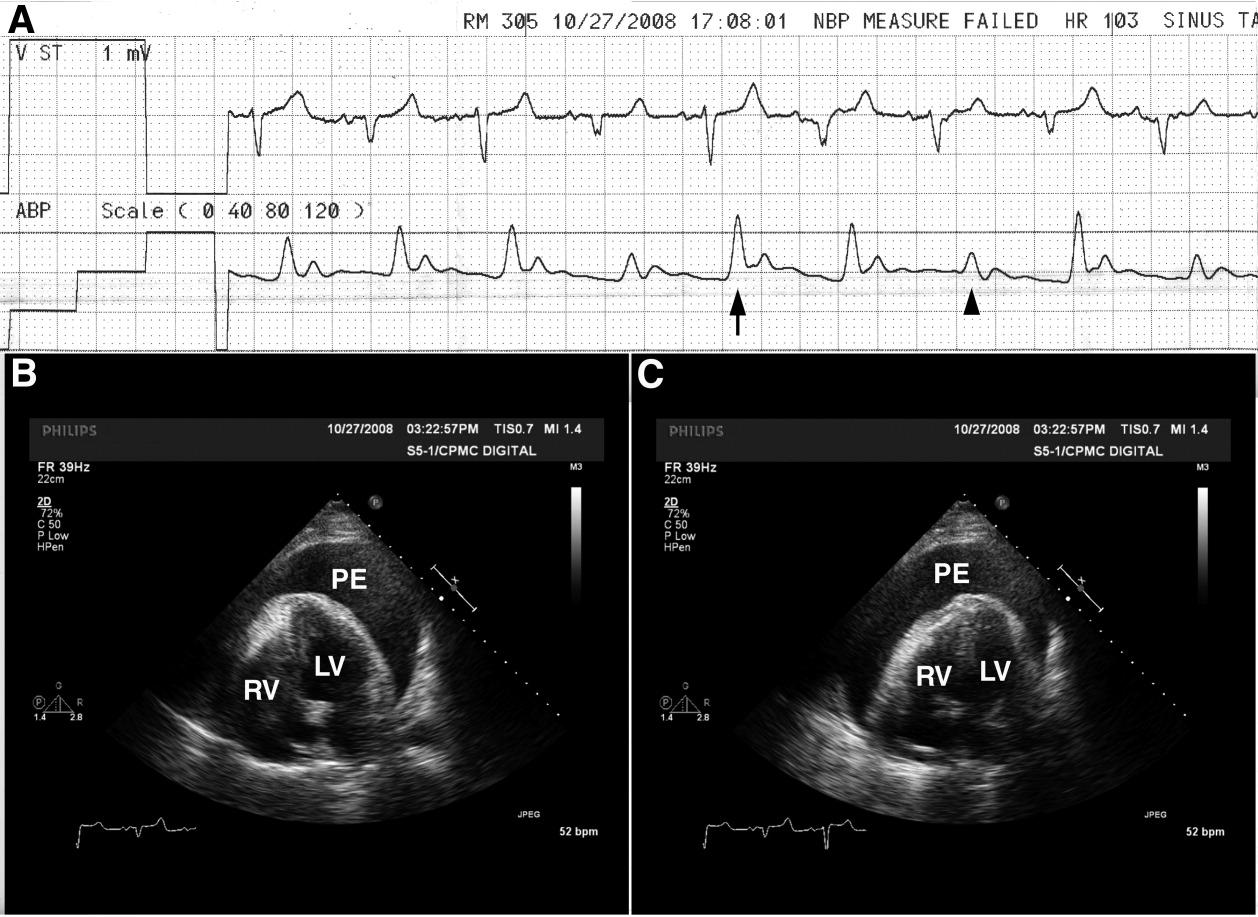

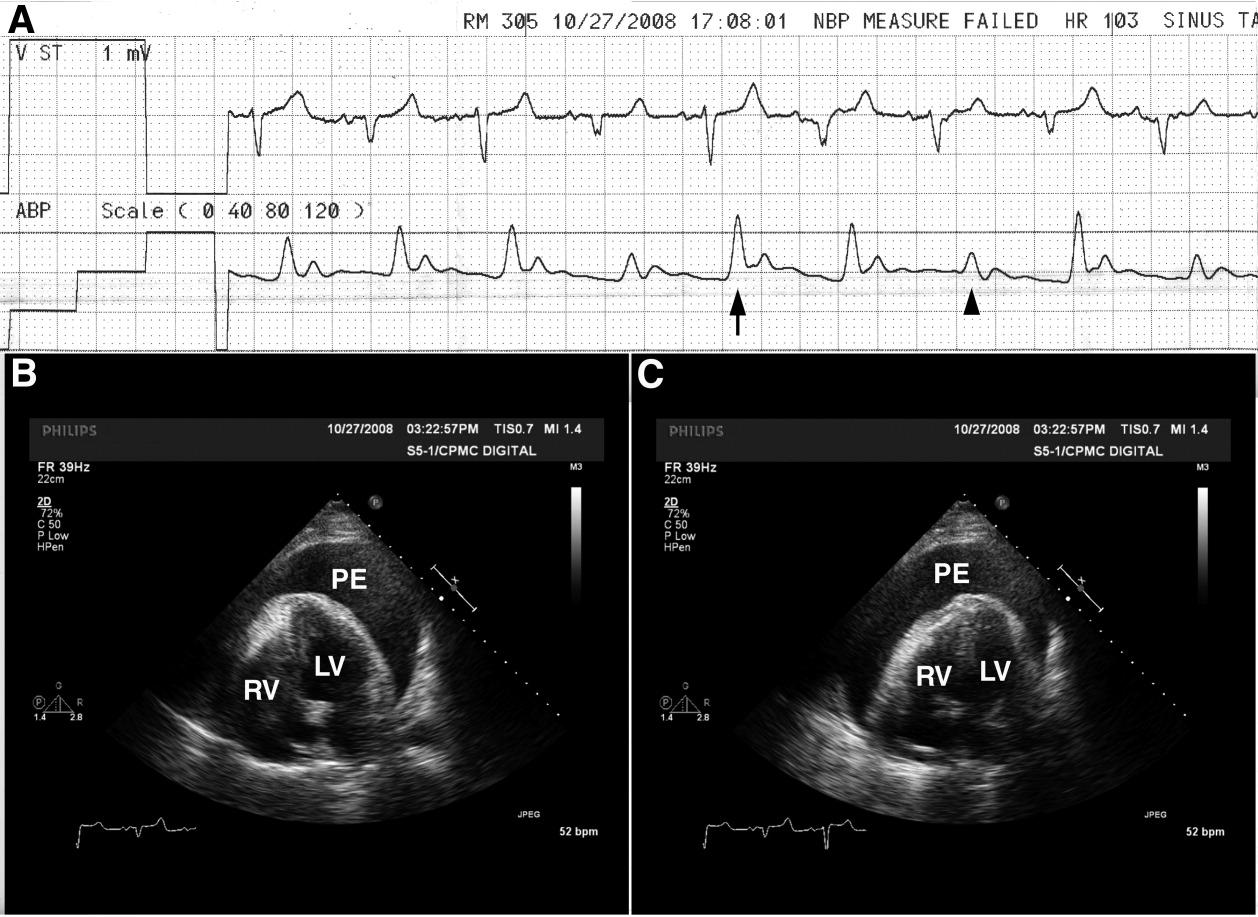

A 65‐year‐old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and right lung nodule presented with dyspnea. Physical examination revealed a pulse of 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 28 times per minute, blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg, estimated jugular venous pressure of greater than 15 cm above the right atrium at a 45‐degree semirecumbent position, and distant heart sounds. He subsequently developed hypotension and an arterial line was placed. A single‐channel electrocardiogram (Figure 1A; upper tracing) demonstrated electrical alternans. Simultaneous arterial line (Figure 1A; lower tracing) showed decreased systolic blood pressure from 136 mm Hg (Figure 1A; arrow) to 96 mm Hg (Figure 1A; arrowhead) with inspiration, consistent with exaggerated pulsus paradoxus. A transthoracic echocardiogram confirmed a large pericardial effusion with the heart oscillating from side (Figure 1B) to side (Figure 1C) within the pericardial sac. Pericardiocentesis was performed and 1100 mL of bloody pericardial fluid was removed with prompt resolution of hypotension, tachycardia, electrical alternans, and abnormal pulsus paradoxus. Pericardial effusion (PE), right ventricle (RV), and left ventricle (LV) are depicted in Figure 1B, C.

The etiology of this patient's pericardial effusion was felt to be due to metastatic pericardial disease from lung cancer. The mechanism of electrical alternans is felt to be due to motion as the heart oscillates back and forth within the pericardial sac.1 The exaggerated pulsus paradoxus reflects decreased LV filling during inspiration as RV filling increases and compresses the LV, referred to as ventricular interdependence.

- ,,.Quantitative echocardiographic assessment in pericardial disease.Echocardiography.1997;14:207–214.

A 65‐year‐old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and right lung nodule presented with dyspnea. Physical examination revealed a pulse of 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 28 times per minute, blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg, estimated jugular venous pressure of greater than 15 cm above the right atrium at a 45‐degree semirecumbent position, and distant heart sounds. He subsequently developed hypotension and an arterial line was placed. A single‐channel electrocardiogram (Figure 1A; upper tracing) demonstrated electrical alternans. Simultaneous arterial line (Figure 1A; lower tracing) showed decreased systolic blood pressure from 136 mm Hg (Figure 1A; arrow) to 96 mm Hg (Figure 1A; arrowhead) with inspiration, consistent with exaggerated pulsus paradoxus. A transthoracic echocardiogram confirmed a large pericardial effusion with the heart oscillating from side (Figure 1B) to side (Figure 1C) within the pericardial sac. Pericardiocentesis was performed and 1100 mL of bloody pericardial fluid was removed with prompt resolution of hypotension, tachycardia, electrical alternans, and abnormal pulsus paradoxus. Pericardial effusion (PE), right ventricle (RV), and left ventricle (LV) are depicted in Figure 1B, C.

The etiology of this patient's pericardial effusion was felt to be due to metastatic pericardial disease from lung cancer. The mechanism of electrical alternans is felt to be due to motion as the heart oscillates back and forth within the pericardial sac.1 The exaggerated pulsus paradoxus reflects decreased LV filling during inspiration as RV filling increases and compresses the LV, referred to as ventricular interdependence.

A 65‐year‐old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and right lung nodule presented with dyspnea. Physical examination revealed a pulse of 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 28 times per minute, blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg, estimated jugular venous pressure of greater than 15 cm above the right atrium at a 45‐degree semirecumbent position, and distant heart sounds. He subsequently developed hypotension and an arterial line was placed. A single‐channel electrocardiogram (Figure 1A; upper tracing) demonstrated electrical alternans. Simultaneous arterial line (Figure 1A; lower tracing) showed decreased systolic blood pressure from 136 mm Hg (Figure 1A; arrow) to 96 mm Hg (Figure 1A; arrowhead) with inspiration, consistent with exaggerated pulsus paradoxus. A transthoracic echocardiogram confirmed a large pericardial effusion with the heart oscillating from side (Figure 1B) to side (Figure 1C) within the pericardial sac. Pericardiocentesis was performed and 1100 mL of bloody pericardial fluid was removed with prompt resolution of hypotension, tachycardia, electrical alternans, and abnormal pulsus paradoxus. Pericardial effusion (PE), right ventricle (RV), and left ventricle (LV) are depicted in Figure 1B, C.

The etiology of this patient's pericardial effusion was felt to be due to metastatic pericardial disease from lung cancer. The mechanism of electrical alternans is felt to be due to motion as the heart oscillates back and forth within the pericardial sac.1 The exaggerated pulsus paradoxus reflects decreased LV filling during inspiration as RV filling increases and compresses the LV, referred to as ventricular interdependence.

- ,,.Quantitative echocardiographic assessment in pericardial disease.Echocardiography.1997;14:207–214.

- ,,.Quantitative echocardiographic assessment in pericardial disease.Echocardiography.1997;14:207–214.

Short Title

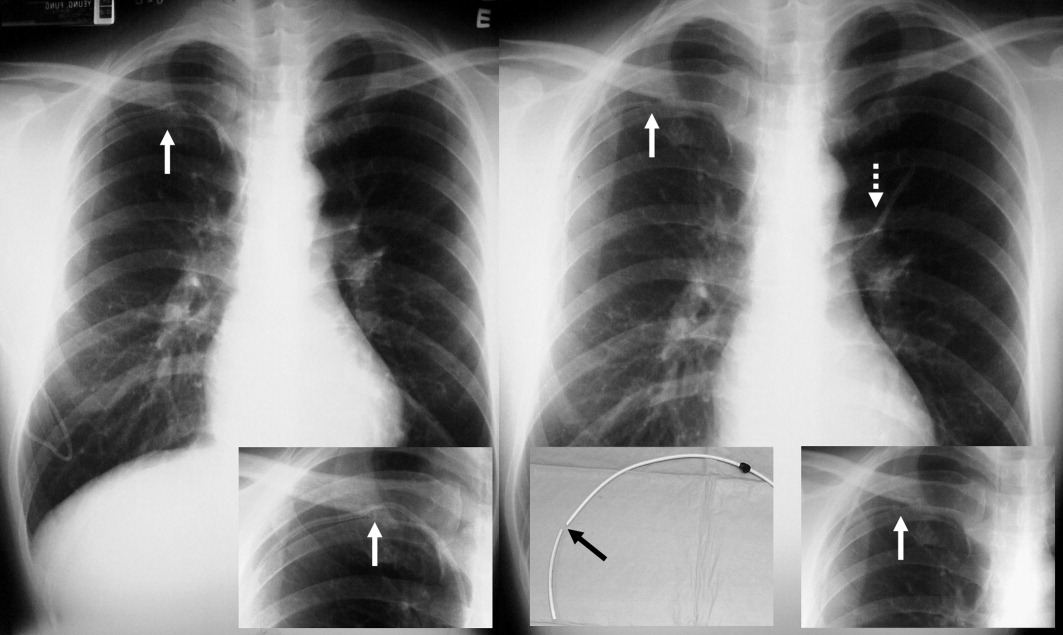

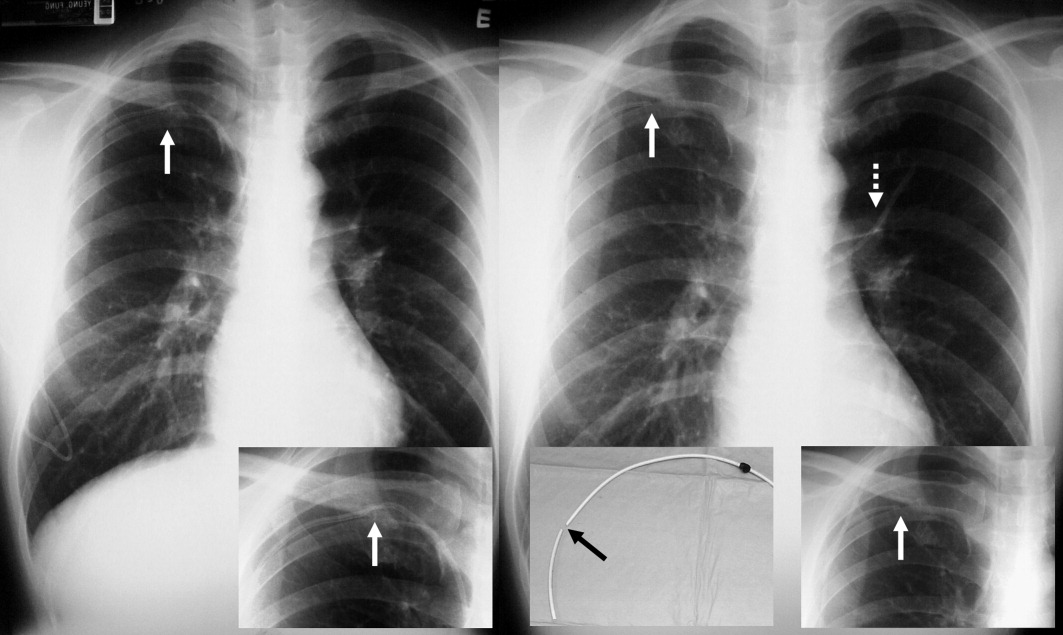

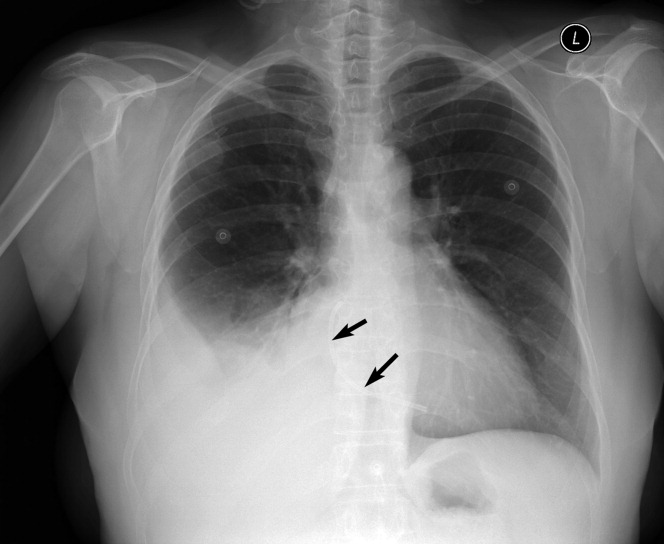

A long‐term tunneled subclavian venous catheter of a 32‐year‐old leukaemia patient blocked. Chest x‐ray (CXR) showed a fracture, with the proximal end underneath the first rib and clavicle (Figure 1, arrow, right panel), and distal fragment at the left hila (broken arrow). A CXR 3 months ago showed catheter kinking and narrowing at the same site, constituting the pinch‐off sign (arrow, left panel).1 The broken fragment was retrieved from the left pulmonary artery by cardiac catheterization. Fractured ends were smooth (central insert).

Spontaneous central venous catheter fracture occurs in 0.1% to 1% of cases.2 The catheter fracture is postulated to be related to compression between the clavicle and first rib due to vigorous movement or heavy object lifting,3 activities that should be avoided. Fractures at other sites are exceptional. The pinch‐off sign may precede fracture; if detected, catheter removal is warranted,4 a fact both clinicians and radiologists should be aware of.

- ,.The “pinch‐off sign”: a warning of impending problems with permanent subclavian catheters.Am J Surg.1984;148:633–636.

- ,,,.Spontaneous leak and transection of permanent subclavian catheters.J Surg Oncol.1998;68:166–168.

- ,,.Pinch‐off syndrome: case report and collective review of the literature.Am Surg.2004;70:635–644.

- ,.Prevention of complications in permanent central venous catheters.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1988;167:6–11.

A long‐term tunneled subclavian venous catheter of a 32‐year‐old leukaemia patient blocked. Chest x‐ray (CXR) showed a fracture, with the proximal end underneath the first rib and clavicle (Figure 1, arrow, right panel), and distal fragment at the left hila (broken arrow). A CXR 3 months ago showed catheter kinking and narrowing at the same site, constituting the pinch‐off sign (arrow, left panel).1 The broken fragment was retrieved from the left pulmonary artery by cardiac catheterization. Fractured ends were smooth (central insert).

Spontaneous central venous catheter fracture occurs in 0.1% to 1% of cases.2 The catheter fracture is postulated to be related to compression between the clavicle and first rib due to vigorous movement or heavy object lifting,3 activities that should be avoided. Fractures at other sites are exceptional. The pinch‐off sign may precede fracture; if detected, catheter removal is warranted,4 a fact both clinicians and radiologists should be aware of.

A long‐term tunneled subclavian venous catheter of a 32‐year‐old leukaemia patient blocked. Chest x‐ray (CXR) showed a fracture, with the proximal end underneath the first rib and clavicle (Figure 1, arrow, right panel), and distal fragment at the left hila (broken arrow). A CXR 3 months ago showed catheter kinking and narrowing at the same site, constituting the pinch‐off sign (arrow, left panel).1 The broken fragment was retrieved from the left pulmonary artery by cardiac catheterization. Fractured ends were smooth (central insert).

Spontaneous central venous catheter fracture occurs in 0.1% to 1% of cases.2 The catheter fracture is postulated to be related to compression between the clavicle and first rib due to vigorous movement or heavy object lifting,3 activities that should be avoided. Fractures at other sites are exceptional. The pinch‐off sign may precede fracture; if detected, catheter removal is warranted,4 a fact both clinicians and radiologists should be aware of.

- ,.The “pinch‐off sign”: a warning of impending problems with permanent subclavian catheters.Am J Surg.1984;148:633–636.

- ,,,.Spontaneous leak and transection of permanent subclavian catheters.J Surg Oncol.1998;68:166–168.

- ,,.Pinch‐off syndrome: case report and collective review of the literature.Am Surg.2004;70:635–644.

- ,.Prevention of complications in permanent central venous catheters.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1988;167:6–11.

- ,.The “pinch‐off sign”: a warning of impending problems with permanent subclavian catheters.Am J Surg.1984;148:633–636.

- ,,,.Spontaneous leak and transection of permanent subclavian catheters.J Surg Oncol.1998;68:166–168.

- ,,.Pinch‐off syndrome: case report and collective review of the literature.Am Surg.2004;70:635–644.

- ,.Prevention of complications in permanent central venous catheters.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1988;167:6–11.

Acute Renal Infarction

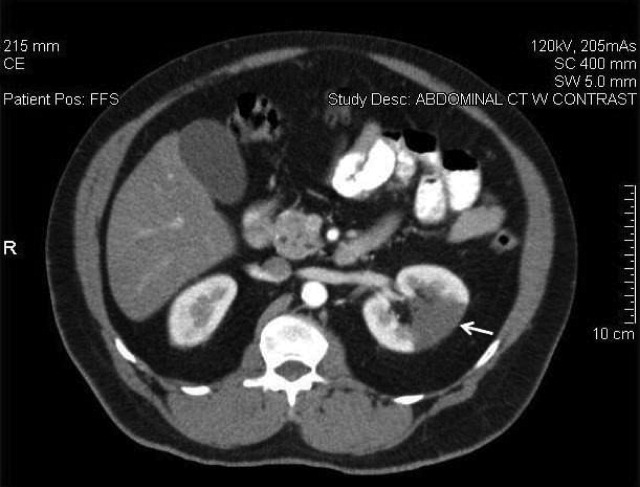

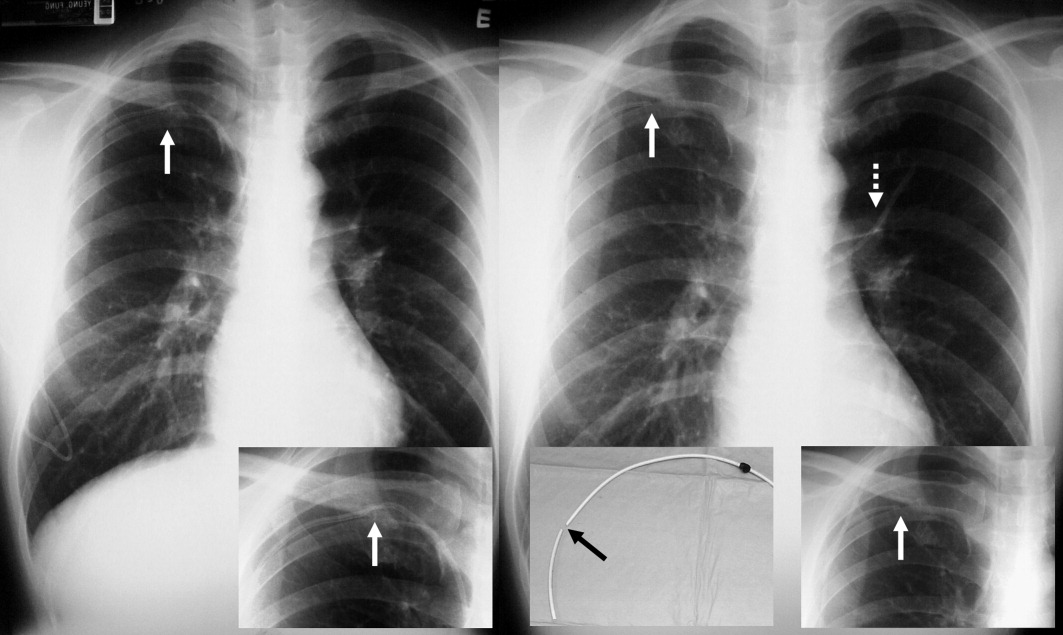

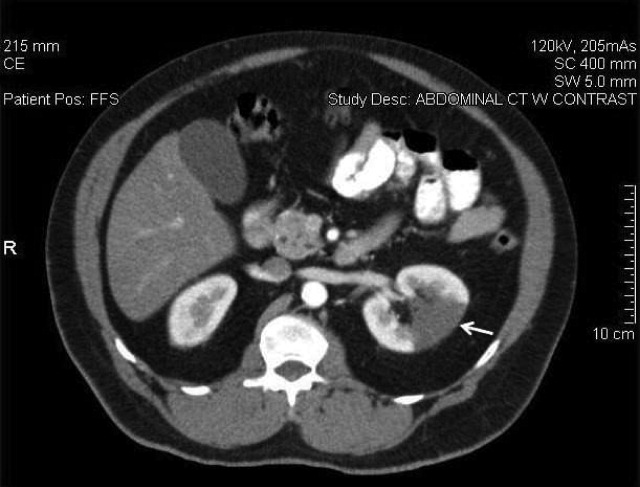

A 58‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain. He had a history of remote tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. His white cell count was 18,500/mm,3 and urinalysis revealed hematuria. Contrast‐enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed decreased perfusion of a large section of the lower pole of the left kidney (Figure 1). On day 3, his flank pain persisted, despite hydration, analgesics, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated and renal infarction was suspected. Heparin was started and the patient was later discharged on warfarin. One month later, repeat contrast‐enhanced abdominal CT showed a less extensive wedge defect with scarring of the left kidney.

The diagnosis of acute renal infarction is often missed due to its nonspecific symptoms and the fact that it is an uncommon disease. It should be suspected in patients with acute flank pain and risk factors for thromboembolism including: valvular or ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and previous thromboembolic events.1, 2 Hypertension, which our patient had, is also a risk factor. In the appropriate setting hematuria and elevated LDH strongly suggest the diagnosis.3 Angiography remains the gold‐standard for diagnosis, but contrast‐enhanced CT is an acceptable alternative.3 In the setting of gross hematuria, we recommend that acute renal infarction should be suspected in all patients with the triad of persistent flank pain, high thromboembolic risk, and an increased LDH.

- ,,, et al.ED presentations of acute renal infarction.Am J Emerg Med.2007;25:164–169.

- ,,,.Renal artery embolism: clinical features and long‐term follow‐up of 17 cases.Ann Intern Med.1978;89:477–482.

- ,,, et al.Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients.Medicine (Baltimore).1999;78:386–394.

A 58‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain. He had a history of remote tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. His white cell count was 18,500/mm,3 and urinalysis revealed hematuria. Contrast‐enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed decreased perfusion of a large section of the lower pole of the left kidney (Figure 1). On day 3, his flank pain persisted, despite hydration, analgesics, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated and renal infarction was suspected. Heparin was started and the patient was later discharged on warfarin. One month later, repeat contrast‐enhanced abdominal CT showed a less extensive wedge defect with scarring of the left kidney.

The diagnosis of acute renal infarction is often missed due to its nonspecific symptoms and the fact that it is an uncommon disease. It should be suspected in patients with acute flank pain and risk factors for thromboembolism including: valvular or ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and previous thromboembolic events.1, 2 Hypertension, which our patient had, is also a risk factor. In the appropriate setting hematuria and elevated LDH strongly suggest the diagnosis.3 Angiography remains the gold‐standard for diagnosis, but contrast‐enhanced CT is an acceptable alternative.3 In the setting of gross hematuria, we recommend that acute renal infarction should be suspected in all patients with the triad of persistent flank pain, high thromboembolic risk, and an increased LDH.

A 58‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain. He had a history of remote tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. His white cell count was 18,500/mm,3 and urinalysis revealed hematuria. Contrast‐enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed decreased perfusion of a large section of the lower pole of the left kidney (Figure 1). On day 3, his flank pain persisted, despite hydration, analgesics, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated and renal infarction was suspected. Heparin was started and the patient was later discharged on warfarin. One month later, repeat contrast‐enhanced abdominal CT showed a less extensive wedge defect with scarring of the left kidney.

The diagnosis of acute renal infarction is often missed due to its nonspecific symptoms and the fact that it is an uncommon disease. It should be suspected in patients with acute flank pain and risk factors for thromboembolism including: valvular or ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and previous thromboembolic events.1, 2 Hypertension, which our patient had, is also a risk factor. In the appropriate setting hematuria and elevated LDH strongly suggest the diagnosis.3 Angiography remains the gold‐standard for diagnosis, but contrast‐enhanced CT is an acceptable alternative.3 In the setting of gross hematuria, we recommend that acute renal infarction should be suspected in all patients with the triad of persistent flank pain, high thromboembolic risk, and an increased LDH.

- ,,, et al.ED presentations of acute renal infarction.Am J Emerg Med.2007;25:164–169.

- ,,,.Renal artery embolism: clinical features and long‐term follow‐up of 17 cases.Ann Intern Med.1978;89:477–482.

- ,,, et al.Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients.Medicine (Baltimore).1999;78:386–394.

- ,,, et al.ED presentations of acute renal infarction.Am J Emerg Med.2007;25:164–169.

- ,,,.Renal artery embolism: clinical features and long‐term follow‐up of 17 cases.Ann Intern Med.1978;89:477–482.

- ,,, et al.Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients.Medicine (Baltimore).1999;78:386–394.

Erythema with Leukemia and Bacteremia

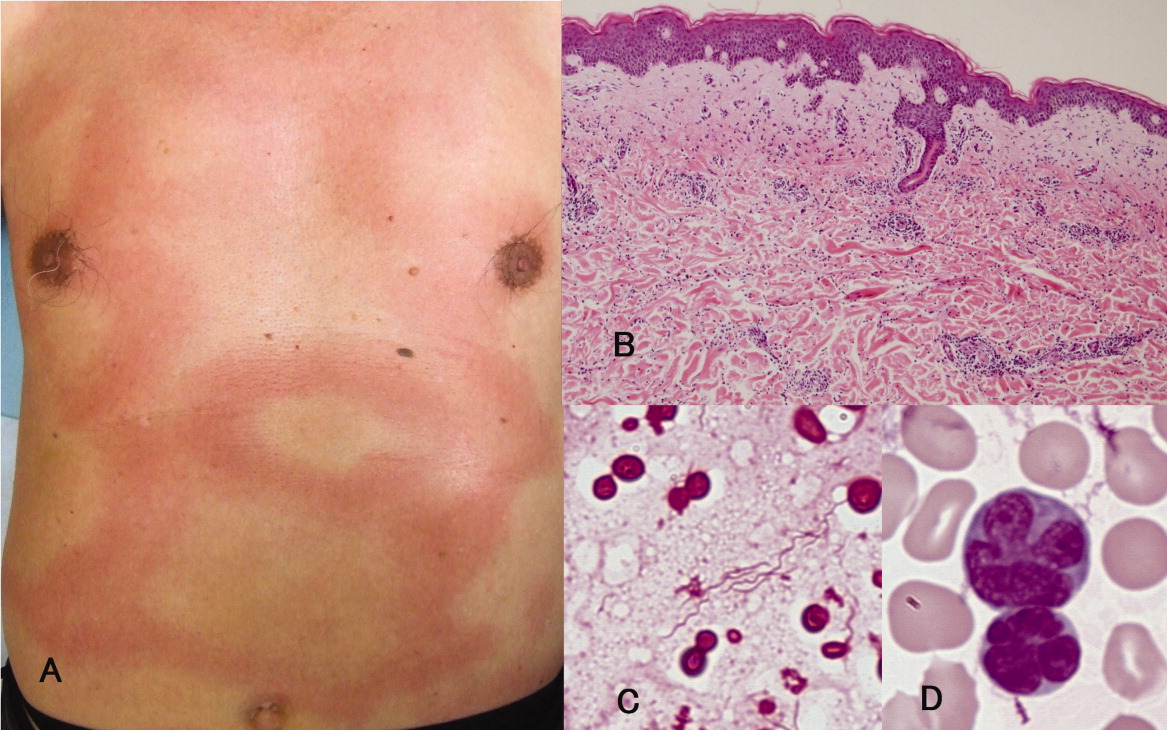

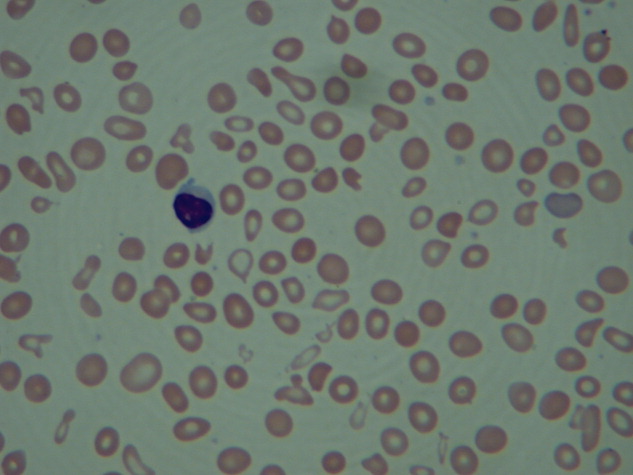

A previously healthy 66‐year‐old man was admitted with a 4‐day history of high fever and an extensive, nonpruritic, nonmigratory, erythematous rash with areas of induration over his torso (Figure 1A). Biopsy of the rash, which spontaneously subsided within 8 days, revealed only nonspecific superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, without vasculitis, granulomas, or immunohistochemical evidence of malignant cells (Figure 1B). Blood cultures grew spiral‐shaped Gram‐negative rods (Figure 1C), which were identified as Helicobacter cinaedi by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). H. cinaedi is a rare pathogen that is reported to cause bacteremia in immunocompromised hosts. Peripheral blood showed more than 2000/L of lymphocytes with prominent hyperlobulated flower‐like nuclei (Figure 1D), which were CD4+/CD8 and CD25+ by flow cytometry. Human T‐lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV‐1) antibody was positive, highlighting the fact that the patient's mother was from southern Kyushu, Japan, where HTLV‐1 is endemic. Diagnosis of adult T‐cell leukemia was confirmed by southern blot hybridization analysis. We believe that this case makes an important addition to the library of annular or gyrate erythemas, which can be secondary to bacteremia, leukemia, or both.

A previously healthy 66‐year‐old man was admitted with a 4‐day history of high fever and an extensive, nonpruritic, nonmigratory, erythematous rash with areas of induration over his torso (Figure 1A). Biopsy of the rash, which spontaneously subsided within 8 days, revealed only nonspecific superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, without vasculitis, granulomas, or immunohistochemical evidence of malignant cells (Figure 1B). Blood cultures grew spiral‐shaped Gram‐negative rods (Figure 1C), which were identified as Helicobacter cinaedi by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). H. cinaedi is a rare pathogen that is reported to cause bacteremia in immunocompromised hosts. Peripheral blood showed more than 2000/L of lymphocytes with prominent hyperlobulated flower‐like nuclei (Figure 1D), which were CD4+/CD8 and CD25+ by flow cytometry. Human T‐lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV‐1) antibody was positive, highlighting the fact that the patient's mother was from southern Kyushu, Japan, where HTLV‐1 is endemic. Diagnosis of adult T‐cell leukemia was confirmed by southern blot hybridization analysis. We believe that this case makes an important addition to the library of annular or gyrate erythemas, which can be secondary to bacteremia, leukemia, or both.

A previously healthy 66‐year‐old man was admitted with a 4‐day history of high fever and an extensive, nonpruritic, nonmigratory, erythematous rash with areas of induration over his torso (Figure 1A). Biopsy of the rash, which spontaneously subsided within 8 days, revealed only nonspecific superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, without vasculitis, granulomas, or immunohistochemical evidence of malignant cells (Figure 1B). Blood cultures grew spiral‐shaped Gram‐negative rods (Figure 1C), which were identified as Helicobacter cinaedi by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). H. cinaedi is a rare pathogen that is reported to cause bacteremia in immunocompromised hosts. Peripheral blood showed more than 2000/L of lymphocytes with prominent hyperlobulated flower‐like nuclei (Figure 1D), which were CD4+/CD8 and CD25+ by flow cytometry. Human T‐lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV‐1) antibody was positive, highlighting the fact that the patient's mother was from southern Kyushu, Japan, where HTLV‐1 is endemic. Diagnosis of adult T‐cell leukemia was confirmed by southern blot hybridization analysis. We believe that this case makes an important addition to the library of annular or gyrate erythemas, which can be secondary to bacteremia, leukemia, or both.

Lower Extremity Ulcers

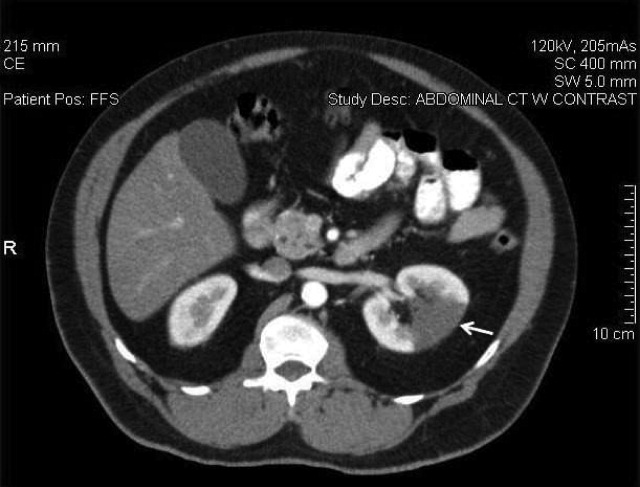

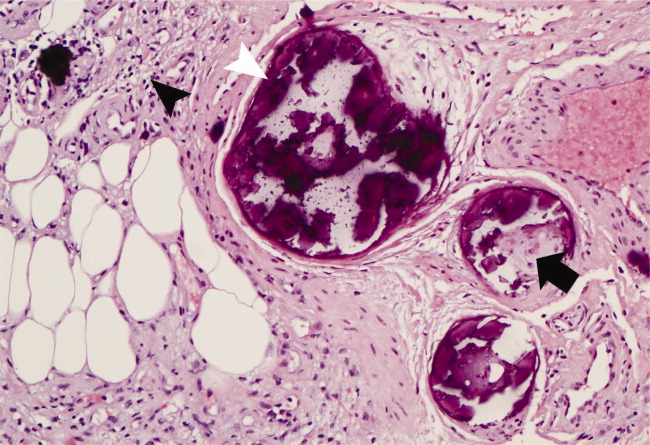

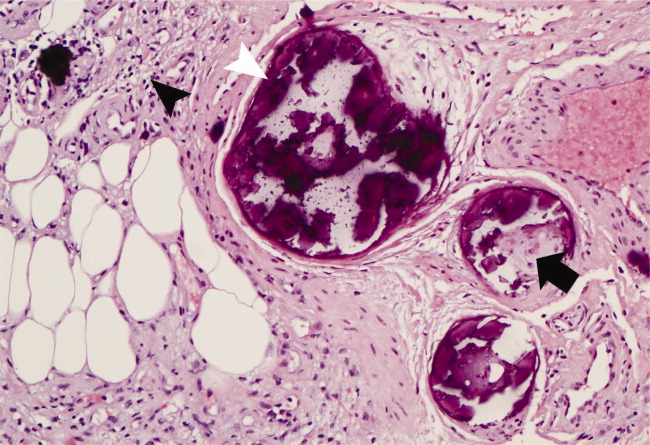

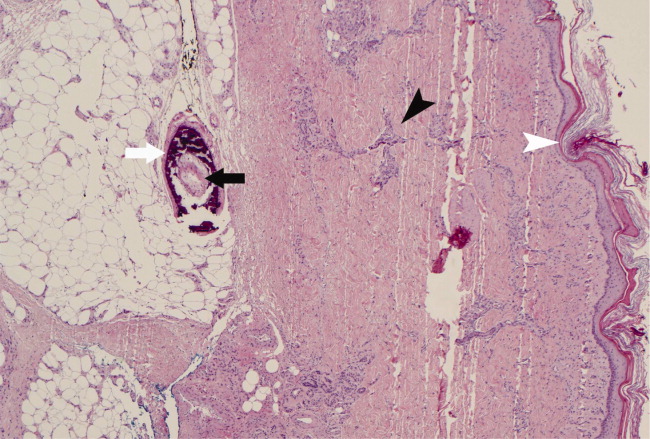

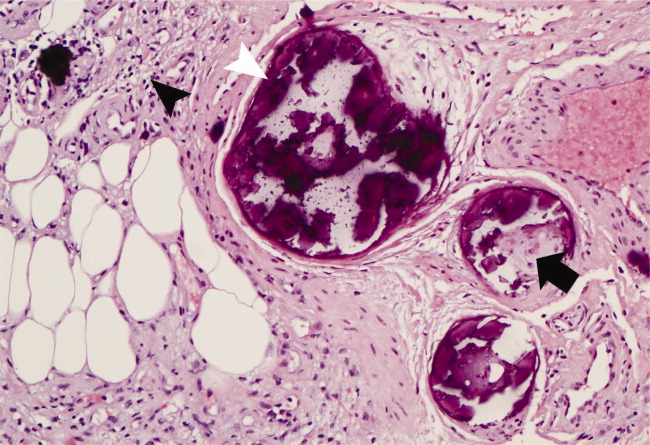

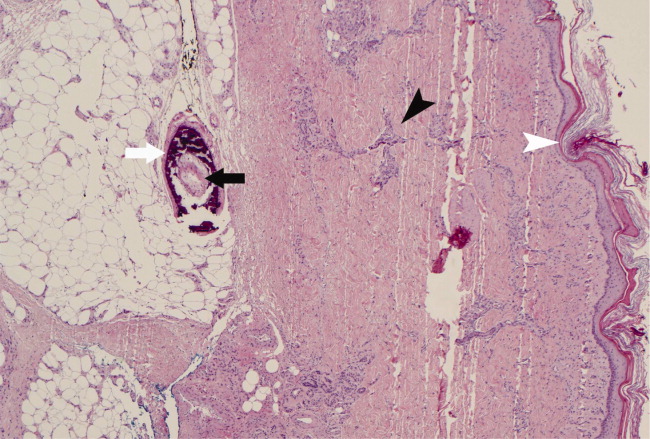

A 62‐year‐old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease (CAD), on peritoneal dialysis, presented with a nonhealing left lower extremity ulcer (Figure 1). Treatment with empiric antibiotics showed no improvement and cultures remained persistently negative. A surgical specimen revealed pathological changes consistent with calciphylaxis (Figures 2 and 3).

With a mortality between 30% and 80% and a 5‐year survival of 40%,1‐3 calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is devastating. Dialysis and a calcium‐phosphate product above 60 mg2/dL2 increased the index of suspicion (our patient = 70).4 As visual findings may resemble vasculitis or atherosclerotic vascular lesions, biopsy remains the mainstay of diagnosis. Findings include intimal fibrosis, medial calcification, panniculitis, and fat necrosis.5

Management involves aggressive phosphate binding, preventing superinfection, and surgical debridement.6 The evidence for newer therapies (sodium thiosulfate, cinacalcet) appears promising,7‐10 while the benefit of parathyroidectomy is equivocal.11 Despite therapy, our patient developed new lesions (right lower extremity, penis) and opted for hospice services.

- ,,,.Cecil Essentials of Medicine.6th ed.New York:W.B. Saunders;2003.

- .Calciphylaxis: pathogenesis and therapy.J Cutan Med Surg.1998;2(4):245‐248.

- ,.Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and treatment.Adv Skin Wound Care.2001;14(6):309‐312.

- ,,.Calciphylaxis.Postgrad Med J.2001;77(911):557‐561.

- Silverberg SG, DeLellis RA, Frable WJ, LiVolsi VA, Wick MR, eds.Silverberg's Principles and Practice of Surgical Pathology and Cytopathology. Vol.1‐2.4th ed.Philadelphia:Elsevier Churchill Livingstone;2006.

- ,,,.Calciphylaxis: medical and surgical management of chronic extensive wounds in a renal dialysis population.Plast Reconstr Surg.2004;113(1):304‐312.

- ,,, et al.Cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis.N Engl J Med.2004;350(15):1516‐1525.

- ,,.Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: case report.Nephrol Dial Transplant.2005;20(6):1260‐1262.

- ,,,.Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate.Am J Kidney Dis.2004;43(6):1104‐1108.

- ,.Intraperitoneal sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of calciphylaxis.Ren Fail.2006;28(4):361‐363.

- ,,,,.Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis.Surgery.2003;134(6):941‐944; discussion 944‐945.

A 62‐year‐old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease (CAD), on peritoneal dialysis, presented with a nonhealing left lower extremity ulcer (Figure 1). Treatment with empiric antibiotics showed no improvement and cultures remained persistently negative. A surgical specimen revealed pathological changes consistent with calciphylaxis (Figures 2 and 3).

With a mortality between 30% and 80% and a 5‐year survival of 40%,1‐3 calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is devastating. Dialysis and a calcium‐phosphate product above 60 mg2/dL2 increased the index of suspicion (our patient = 70).4 As visual findings may resemble vasculitis or atherosclerotic vascular lesions, biopsy remains the mainstay of diagnosis. Findings include intimal fibrosis, medial calcification, panniculitis, and fat necrosis.5

Management involves aggressive phosphate binding, preventing superinfection, and surgical debridement.6 The evidence for newer therapies (sodium thiosulfate, cinacalcet) appears promising,7‐10 while the benefit of parathyroidectomy is equivocal.11 Despite therapy, our patient developed new lesions (right lower extremity, penis) and opted for hospice services.

A 62‐year‐old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease (CAD), on peritoneal dialysis, presented with a nonhealing left lower extremity ulcer (Figure 1). Treatment with empiric antibiotics showed no improvement and cultures remained persistently negative. A surgical specimen revealed pathological changes consistent with calciphylaxis (Figures 2 and 3).

With a mortality between 30% and 80% and a 5‐year survival of 40%,1‐3 calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is devastating. Dialysis and a calcium‐phosphate product above 60 mg2/dL2 increased the index of suspicion (our patient = 70).4 As visual findings may resemble vasculitis or atherosclerotic vascular lesions, biopsy remains the mainstay of diagnosis. Findings include intimal fibrosis, medial calcification, panniculitis, and fat necrosis.5

Management involves aggressive phosphate binding, preventing superinfection, and surgical debridement.6 The evidence for newer therapies (sodium thiosulfate, cinacalcet) appears promising,7‐10 while the benefit of parathyroidectomy is equivocal.11 Despite therapy, our patient developed new lesions (right lower extremity, penis) and opted for hospice services.

- ,,,.Cecil Essentials of Medicine.6th ed.New York:W.B. Saunders;2003.

- .Calciphylaxis: pathogenesis and therapy.J Cutan Med Surg.1998;2(4):245‐248.

- ,.Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and treatment.Adv Skin Wound Care.2001;14(6):309‐312.

- ,,.Calciphylaxis.Postgrad Med J.2001;77(911):557‐561.

- Silverberg SG, DeLellis RA, Frable WJ, LiVolsi VA, Wick MR, eds.Silverberg's Principles and Practice of Surgical Pathology and Cytopathology. Vol.1‐2.4th ed.Philadelphia:Elsevier Churchill Livingstone;2006.

- ,,,.Calciphylaxis: medical and surgical management of chronic extensive wounds in a renal dialysis population.Plast Reconstr Surg.2004;113(1):304‐312.

- ,,, et al.Cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis.N Engl J Med.2004;350(15):1516‐1525.

- ,,.Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: case report.Nephrol Dial Transplant.2005;20(6):1260‐1262.

- ,,,.Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate.Am J Kidney Dis.2004;43(6):1104‐1108.

- ,.Intraperitoneal sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of calciphylaxis.Ren Fail.2006;28(4):361‐363.

- ,,,,.Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis.Surgery.2003;134(6):941‐944; discussion 944‐945.

- ,,,.Cecil Essentials of Medicine.6th ed.New York:W.B. Saunders;2003.

- .Calciphylaxis: pathogenesis and therapy.J Cutan Med Surg.1998;2(4):245‐248.

- ,.Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and treatment.Adv Skin Wound Care.2001;14(6):309‐312.

- ,,.Calciphylaxis.Postgrad Med J.2001;77(911):557‐561.

- Silverberg SG, DeLellis RA, Frable WJ, LiVolsi VA, Wick MR, eds.Silverberg's Principles and Practice of Surgical Pathology and Cytopathology. Vol.1‐2.4th ed.Philadelphia:Elsevier Churchill Livingstone;2006.

- ,,,.Calciphylaxis: medical and surgical management of chronic extensive wounds in a renal dialysis population.Plast Reconstr Surg.2004;113(1):304‐312.

- ,,, et al.Cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis.N Engl J Med.2004;350(15):1516‐1525.

- ,,.Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: case report.Nephrol Dial Transplant.2005;20(6):1260‐1262.

- ,,,.Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate.Am J Kidney Dis.2004;43(6):1104‐1108.

- ,.Intraperitoneal sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of calciphylaxis.Ren Fail.2006;28(4):361‐363.

- ,,,,.Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis.Surgery.2003;134(6):941‐944; discussion 944‐945.

A Painful Rash

A 40‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with a 5‐day history of fever, productive cough, and a painful rash. The rash was composed of grouped, raised, fluid‐filled vesicles with an erythematous base and honey‐colored crusting (Figure 1). The patient had a history of prior tuberculosis infection, illicit drug use, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). On initial physical examination, oral temperature was 98.5F, pulse was 110 beats/minute, respiratory rate was 22 breaths/minute, blood pressure was 151/79 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 94%. Laboratory test results at admission were as follows: hemoglobin 10.6 g/dL; platelets 364,000 cells/L; white blood cell count 8,300 cells/L; CD4 count 132 cells/L; total serum protein 9.1 g/dL; albumin 2.0 g/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 158 IU/L. Chest radiograph showed diffuse pulmonary infiltrates bilaterally (Figure 2). Sputum cultures showed regular respiratory flora and no acid fast bacilli. Viral cultures of the vesicular lesions were positive for varicella zoster virus (VZV). The patient was started on acyclovir for VZV. After 2 days the patient's symptoms improved and he was subsequently discharged.

Herpes zoster is caused by the reactivation of a latent VZV infection in the dorsal root ganglion or cranial nerve ganglion. Zoster is characterized by an erythematous, vesicular, pustular rash in a unilateral dermatomal distribution. Immunosuppression is a risk factor for zoster; however, 92% of cases are in immunocompetent patients.1 Further, immunocompromised patients are more likely to develop disseminated zoster infection, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis. These patients are also more likely to have secondary bacterial superinfections of cutaneous lesions and respiratory tracts.2 While zoster is often self‐limiting, it can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Intravenous acyclovir should be considered in patients with disseminated disease or visceral involvement, with advanced HIV, and in transplant patients being treated for rejection.2 Unilateral erythematous, vesicular rashes in a dermatomal distribution should yield a high clinical suspicion for herpes zoster, especially in immunocompromised patients.

- .A population‐based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction.Mayo Clin Proc.2007;82(11):1341–1349.

- . Herpes zoster. http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/TOPIC823. HTM. Accessed May2009.

A 40‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with a 5‐day history of fever, productive cough, and a painful rash. The rash was composed of grouped, raised, fluid‐filled vesicles with an erythematous base and honey‐colored crusting (Figure 1). The patient had a history of prior tuberculosis infection, illicit drug use, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). On initial physical examination, oral temperature was 98.5F, pulse was 110 beats/minute, respiratory rate was 22 breaths/minute, blood pressure was 151/79 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 94%. Laboratory test results at admission were as follows: hemoglobin 10.6 g/dL; platelets 364,000 cells/L; white blood cell count 8,300 cells/L; CD4 count 132 cells/L; total serum protein 9.1 g/dL; albumin 2.0 g/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 158 IU/L. Chest radiograph showed diffuse pulmonary infiltrates bilaterally (Figure 2). Sputum cultures showed regular respiratory flora and no acid fast bacilli. Viral cultures of the vesicular lesions were positive for varicella zoster virus (VZV). The patient was started on acyclovir for VZV. After 2 days the patient's symptoms improved and he was subsequently discharged.

Herpes zoster is caused by the reactivation of a latent VZV infection in the dorsal root ganglion or cranial nerve ganglion. Zoster is characterized by an erythematous, vesicular, pustular rash in a unilateral dermatomal distribution. Immunosuppression is a risk factor for zoster; however, 92% of cases are in immunocompetent patients.1 Further, immunocompromised patients are more likely to develop disseminated zoster infection, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis. These patients are also more likely to have secondary bacterial superinfections of cutaneous lesions and respiratory tracts.2 While zoster is often self‐limiting, it can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Intravenous acyclovir should be considered in patients with disseminated disease or visceral involvement, with advanced HIV, and in transplant patients being treated for rejection.2 Unilateral erythematous, vesicular rashes in a dermatomal distribution should yield a high clinical suspicion for herpes zoster, especially in immunocompromised patients.

A 40‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with a 5‐day history of fever, productive cough, and a painful rash. The rash was composed of grouped, raised, fluid‐filled vesicles with an erythematous base and honey‐colored crusting (Figure 1). The patient had a history of prior tuberculosis infection, illicit drug use, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). On initial physical examination, oral temperature was 98.5F, pulse was 110 beats/minute, respiratory rate was 22 breaths/minute, blood pressure was 151/79 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 94%. Laboratory test results at admission were as follows: hemoglobin 10.6 g/dL; platelets 364,000 cells/L; white blood cell count 8,300 cells/L; CD4 count 132 cells/L; total serum protein 9.1 g/dL; albumin 2.0 g/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 158 IU/L. Chest radiograph showed diffuse pulmonary infiltrates bilaterally (Figure 2). Sputum cultures showed regular respiratory flora and no acid fast bacilli. Viral cultures of the vesicular lesions were positive for varicella zoster virus (VZV). The patient was started on acyclovir for VZV. After 2 days the patient's symptoms improved and he was subsequently discharged.

Herpes zoster is caused by the reactivation of a latent VZV infection in the dorsal root ganglion or cranial nerve ganglion. Zoster is characterized by an erythematous, vesicular, pustular rash in a unilateral dermatomal distribution. Immunosuppression is a risk factor for zoster; however, 92% of cases are in immunocompetent patients.1 Further, immunocompromised patients are more likely to develop disseminated zoster infection, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis. These patients are also more likely to have secondary bacterial superinfections of cutaneous lesions and respiratory tracts.2 While zoster is often self‐limiting, it can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Intravenous acyclovir should be considered in patients with disseminated disease or visceral involvement, with advanced HIV, and in transplant patients being treated for rejection.2 Unilateral erythematous, vesicular rashes in a dermatomal distribution should yield a high clinical suspicion for herpes zoster, especially in immunocompromised patients.

- .A population‐based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction.Mayo Clin Proc.2007;82(11):1341–1349.

- . Herpes zoster. http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/TOPIC823. HTM. Accessed May2009.

- .A population‐based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction.Mayo Clin Proc.2007;82(11):1341–1349.

- . Herpes zoster. http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/TOPIC823. HTM. Accessed May2009.

Drumstick Digits

A 42‐year‐old man with chronic kidney disease and a history of childhood repair of Tetralogy of Fallot was admitted with pneumonia. Examination of his extremities revealed clubbing of his fingers (Figure 1) and toes (Figure 2).

Clubbing may be primary, known as pachydermoperiostosis, or secondary, due to a variety of neoplastic, pulmonary, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and infectious diseases.1 Examination reveals softening of the nail bed with loss of the normal angle between the nail and the proximal nail fold, an increase in the nail fold convexity, and thickening of the distal phalange with eventual hyperextensibility of the distal interphalangeal joint. Diagnosis is based on various criteria, such as the profile angle (Lovibond's angle) or distal phalangeal to interphalangeal depth ratio. The loss of the normal diamond‐shaped window created by placing the back surfaces of terminal phalanges of similar fingers together, also known as Schamroth's sign, was noted by Dr. Leo Schamroth when he developed endocarditis and is one of the few eponyms named after both a physician and the patient in whom it was found (Figure 3).2 Recent literature suggests that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a platelet‐derived factor induced by hypoxia, may play a role in digital clubbing.3 Processes that alter normal pulmonary circulation disrupt fragmentation of megakaryocytes in the lung into platelets. Consequently, whole megakaryocytes enter the systemic circulation and become impacted in the peripheral capillaries, where they cause stromal hypoxia and release of platelet‐derived growth factor and VEGF, leading to the vascular hyperplasia that underlies clubbing.

- ,,.Clubbing: an update on diagnosis, differential diagnosis, pathophysiology, and clinical relevance.J Am Acad Dermatol.2005;52:1020–1028.

- .A unique eponymous sign of finger clubbing (Schamroth sign) that is named not only after a physician who described it but also after the patient who happened to be the physician himself.Am J Cardiol.2005;96:1614–1615.

- .Exploring the cause of the most ancient clinical sign of medicine: finger clubbing.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2007;36:380–385.

A 42‐year‐old man with chronic kidney disease and a history of childhood repair of Tetralogy of Fallot was admitted with pneumonia. Examination of his extremities revealed clubbing of his fingers (Figure 1) and toes (Figure 2).

Clubbing may be primary, known as pachydermoperiostosis, or secondary, due to a variety of neoplastic, pulmonary, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and infectious diseases.1 Examination reveals softening of the nail bed with loss of the normal angle between the nail and the proximal nail fold, an increase in the nail fold convexity, and thickening of the distal phalange with eventual hyperextensibility of the distal interphalangeal joint. Diagnosis is based on various criteria, such as the profile angle (Lovibond's angle) or distal phalangeal to interphalangeal depth ratio. The loss of the normal diamond‐shaped window created by placing the back surfaces of terminal phalanges of similar fingers together, also known as Schamroth's sign, was noted by Dr. Leo Schamroth when he developed endocarditis and is one of the few eponyms named after both a physician and the patient in whom it was found (Figure 3).2 Recent literature suggests that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a platelet‐derived factor induced by hypoxia, may play a role in digital clubbing.3 Processes that alter normal pulmonary circulation disrupt fragmentation of megakaryocytes in the lung into platelets. Consequently, whole megakaryocytes enter the systemic circulation and become impacted in the peripheral capillaries, where they cause stromal hypoxia and release of platelet‐derived growth factor and VEGF, leading to the vascular hyperplasia that underlies clubbing.

A 42‐year‐old man with chronic kidney disease and a history of childhood repair of Tetralogy of Fallot was admitted with pneumonia. Examination of his extremities revealed clubbing of his fingers (Figure 1) and toes (Figure 2).

Clubbing may be primary, known as pachydermoperiostosis, or secondary, due to a variety of neoplastic, pulmonary, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and infectious diseases.1 Examination reveals softening of the nail bed with loss of the normal angle between the nail and the proximal nail fold, an increase in the nail fold convexity, and thickening of the distal phalange with eventual hyperextensibility of the distal interphalangeal joint. Diagnosis is based on various criteria, such as the profile angle (Lovibond's angle) or distal phalangeal to interphalangeal depth ratio. The loss of the normal diamond‐shaped window created by placing the back surfaces of terminal phalanges of similar fingers together, also known as Schamroth's sign, was noted by Dr. Leo Schamroth when he developed endocarditis and is one of the few eponyms named after both a physician and the patient in whom it was found (Figure 3).2 Recent literature suggests that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a platelet‐derived factor induced by hypoxia, may play a role in digital clubbing.3 Processes that alter normal pulmonary circulation disrupt fragmentation of megakaryocytes in the lung into platelets. Consequently, whole megakaryocytes enter the systemic circulation and become impacted in the peripheral capillaries, where they cause stromal hypoxia and release of platelet‐derived growth factor and VEGF, leading to the vascular hyperplasia that underlies clubbing.

- ,,.Clubbing: an update on diagnosis, differential diagnosis, pathophysiology, and clinical relevance.J Am Acad Dermatol.2005;52:1020–1028.

- .A unique eponymous sign of finger clubbing (Schamroth sign) that is named not only after a physician who described it but also after the patient who happened to be the physician himself.Am J Cardiol.2005;96:1614–1615.

- .Exploring the cause of the most ancient clinical sign of medicine: finger clubbing.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2007;36:380–385.

- ,,.Clubbing: an update on diagnosis, differential diagnosis, pathophysiology, and clinical relevance.J Am Acad Dermatol.2005;52:1020–1028.

- .A unique eponymous sign of finger clubbing (Schamroth sign) that is named not only after a physician who described it but also after the patient who happened to be the physician himself.Am J Cardiol.2005;96:1614–1615.

- .Exploring the cause of the most ancient clinical sign of medicine: finger clubbing.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2007;36:380–385.

Myelofibrosis with Hepatosplenomegaly

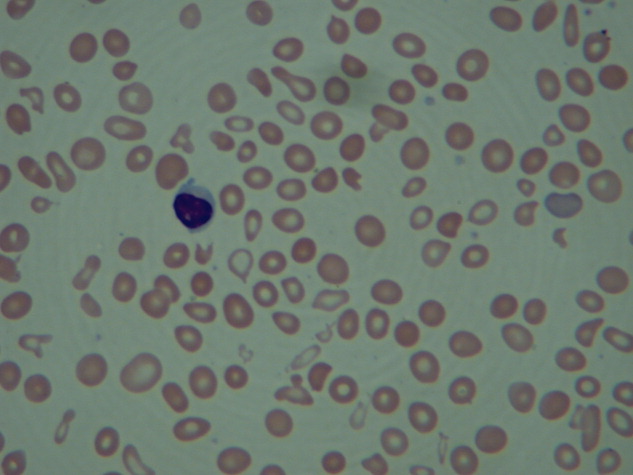

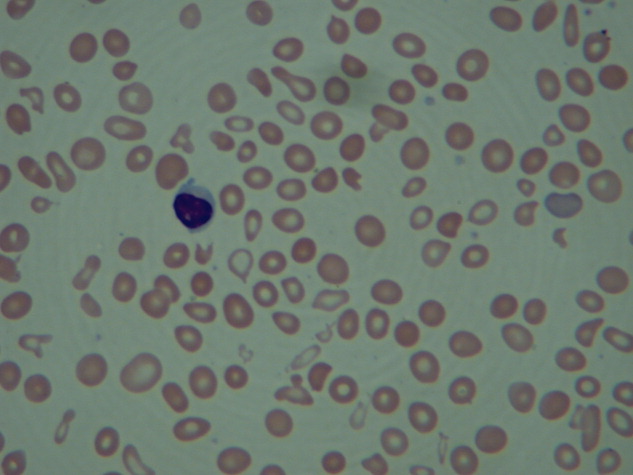

An 83‐year‐old man with a 7‐year history of myelofibrosis presented to the hospital with progressive weakness and fatigue, which resulted in him tripping and falling onto his left hand and arm 1 day prior to admission. His past medical history was significant for transfusion‐dependent anemia and hypertension. His current treatment regimen for myelofibrosis included thalidomide and darbopoetin alfa.

Physical examination revealed a pale and edematous man who was holding his injured arm to his chest, but in no distress. He had massive hepatosplenomegaly (Figure 1) and pitting edema of the lower extremities that extended to his abdomen.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood count of 5000, hematocrit of 29%, and platelets of 218,000. The peripheral blood smear (Figure 2) showed marked anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, and teardrop cells (Figure 2; arrow).

Imaging of the left arm and hand was significant for a third metacarpal fracture and first phalanx fracture. Of note, these x‐rays also revealed numerous round lucencies within the osseous structures of the left hand, wrist, and forearm (Figure 3; arrow).

The patient's hospital course was uncomplicated and included casting of the left arm, treatment of his lower extremity edema, and transfusion for a slowly declining hematocrit. He was discharged home after several days but died 1 month later.

Primary myelofibrosis is a myeloproliferative disease that consists of 2 phases. The first phase is the growth and proliferation of abnormal bone marrow stem cells, which leads to ineffective erythropoiesis. This is followed by reactive myelofibrosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis.1 These 2 phases of the disease can lead to a constellation of findings, as illustrated in these images. The median length of survival from diagnosis is 3 to 5 years, with the main causes of death being infection, hemorrhage, cardiac failure, and leukemic transformation.1 Presenting signs, symptoms, and laboratory results may include cachexia, splenomegaly, anemia, an increased or decreased white blood cell count and/or platelet count, and an increase in lactate dehydrogenase. Radiographically, the most common findings are marked splenomegaly and osteosclerosis.2

Osteosclerotic lesions are found in 30% to 70% of patients with myelofibrosis and are a result of marrow fibrosis, which leads to the appearance of diffuse, patchy increases in bone density.2 Osteolytic lesions, as seen in this case, are much less common. They appear in the literature in case reports, but are not considered to be a typical finding. They are usually painful and have been reported as a poor prognostic indicator.3, 4

- Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia.N Engl J Med.2000;342(17):1255‒1265.

- ,,,,.Imaging findings in patients with myelofibrosis.Eur Radiol.1999;9:1366‒1375.

- ,,, et al.Unusual radiological findings in a case of myelofibrosis secondary to polycythemia vera.Ann Hematol.2006;85:555‒556.

- ,,.Osteolytic bone lesions in a patient with idiopathic myelofibrosis and bronchial carcinoma.J Clin Pathol.1995;48:867‒868.

An 83‐year‐old man with a 7‐year history of myelofibrosis presented to the hospital with progressive weakness and fatigue, which resulted in him tripping and falling onto his left hand and arm 1 day prior to admission. His past medical history was significant for transfusion‐dependent anemia and hypertension. His current treatment regimen for myelofibrosis included thalidomide and darbopoetin alfa.

Physical examination revealed a pale and edematous man who was holding his injured arm to his chest, but in no distress. He had massive hepatosplenomegaly (Figure 1) and pitting edema of the lower extremities that extended to his abdomen.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood count of 5000, hematocrit of 29%, and platelets of 218,000. The peripheral blood smear (Figure 2) showed marked anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, and teardrop cells (Figure 2; arrow).

Imaging of the left arm and hand was significant for a third metacarpal fracture and first phalanx fracture. Of note, these x‐rays also revealed numerous round lucencies within the osseous structures of the left hand, wrist, and forearm (Figure 3; arrow).

The patient's hospital course was uncomplicated and included casting of the left arm, treatment of his lower extremity edema, and transfusion for a slowly declining hematocrit. He was discharged home after several days but died 1 month later.

Primary myelofibrosis is a myeloproliferative disease that consists of 2 phases. The first phase is the growth and proliferation of abnormal bone marrow stem cells, which leads to ineffective erythropoiesis. This is followed by reactive myelofibrosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis.1 These 2 phases of the disease can lead to a constellation of findings, as illustrated in these images. The median length of survival from diagnosis is 3 to 5 years, with the main causes of death being infection, hemorrhage, cardiac failure, and leukemic transformation.1 Presenting signs, symptoms, and laboratory results may include cachexia, splenomegaly, anemia, an increased or decreased white blood cell count and/or platelet count, and an increase in lactate dehydrogenase. Radiographically, the most common findings are marked splenomegaly and osteosclerosis.2

Osteosclerotic lesions are found in 30% to 70% of patients with myelofibrosis and are a result of marrow fibrosis, which leads to the appearance of diffuse, patchy increases in bone density.2 Osteolytic lesions, as seen in this case, are much less common. They appear in the literature in case reports, but are not considered to be a typical finding. They are usually painful and have been reported as a poor prognostic indicator.3, 4

An 83‐year‐old man with a 7‐year history of myelofibrosis presented to the hospital with progressive weakness and fatigue, which resulted in him tripping and falling onto his left hand and arm 1 day prior to admission. His past medical history was significant for transfusion‐dependent anemia and hypertension. His current treatment regimen for myelofibrosis included thalidomide and darbopoetin alfa.

Physical examination revealed a pale and edematous man who was holding his injured arm to his chest, but in no distress. He had massive hepatosplenomegaly (Figure 1) and pitting edema of the lower extremities that extended to his abdomen.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood count of 5000, hematocrit of 29%, and platelets of 218,000. The peripheral blood smear (Figure 2) showed marked anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, and teardrop cells (Figure 2; arrow).

Imaging of the left arm and hand was significant for a third metacarpal fracture and first phalanx fracture. Of note, these x‐rays also revealed numerous round lucencies within the osseous structures of the left hand, wrist, and forearm (Figure 3; arrow).

The patient's hospital course was uncomplicated and included casting of the left arm, treatment of his lower extremity edema, and transfusion for a slowly declining hematocrit. He was discharged home after several days but died 1 month later.

Primary myelofibrosis is a myeloproliferative disease that consists of 2 phases. The first phase is the growth and proliferation of abnormal bone marrow stem cells, which leads to ineffective erythropoiesis. This is followed by reactive myelofibrosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis.1 These 2 phases of the disease can lead to a constellation of findings, as illustrated in these images. The median length of survival from diagnosis is 3 to 5 years, with the main causes of death being infection, hemorrhage, cardiac failure, and leukemic transformation.1 Presenting signs, symptoms, and laboratory results may include cachexia, splenomegaly, anemia, an increased or decreased white blood cell count and/or platelet count, and an increase in lactate dehydrogenase. Radiographically, the most common findings are marked splenomegaly and osteosclerosis.2

Osteosclerotic lesions are found in 30% to 70% of patients with myelofibrosis and are a result of marrow fibrosis, which leads to the appearance of diffuse, patchy increases in bone density.2 Osteolytic lesions, as seen in this case, are much less common. They appear in the literature in case reports, but are not considered to be a typical finding. They are usually painful and have been reported as a poor prognostic indicator.3, 4

- Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia.N Engl J Med.2000;342(17):1255‒1265.

- ,,,,.Imaging findings in patients with myelofibrosis.Eur Radiol.1999;9:1366‒1375.

- ,,, et al.Unusual radiological findings in a case of myelofibrosis secondary to polycythemia vera.Ann Hematol.2006;85:555‒556.

- ,,.Osteolytic bone lesions in a patient with idiopathic myelofibrosis and bronchial carcinoma.J Clin Pathol.1995;48:867‒868.

- Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia.N Engl J Med.2000;342(17):1255‒1265.

- ,,,,.Imaging findings in patients with myelofibrosis.Eur Radiol.1999;9:1366‒1375.

- ,,, et al.Unusual radiological findings in a case of myelofibrosis secondary to polycythemia vera.Ann Hematol.2006;85:555‒556.

- ,,.Osteolytic bone lesions in a patient with idiopathic myelofibrosis and bronchial carcinoma.J Clin Pathol.1995;48:867‒868.

Disseminated Sporotrichosis

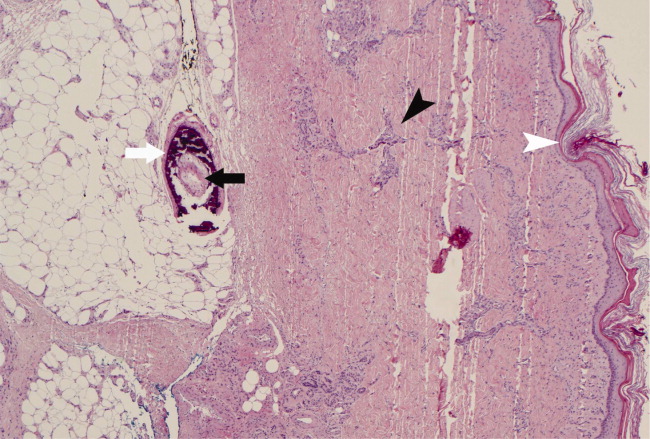

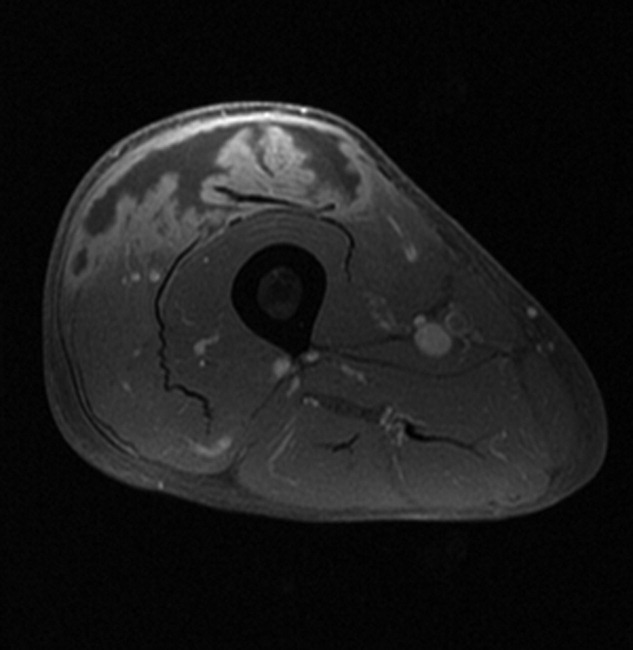

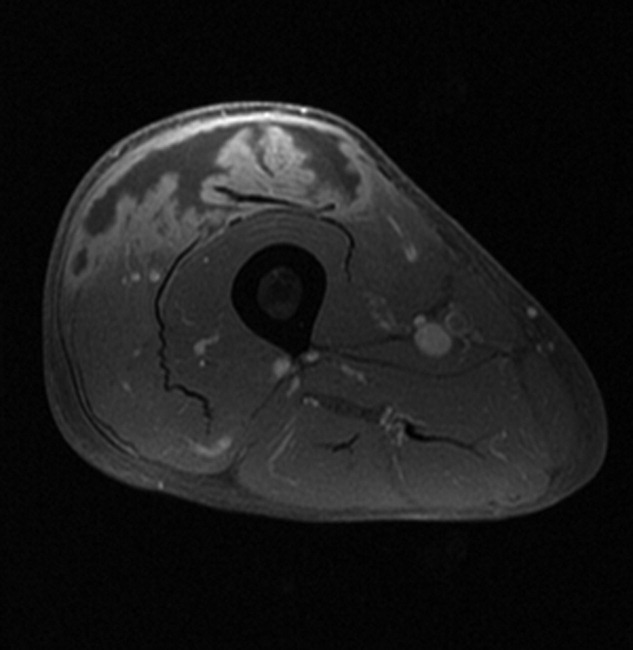

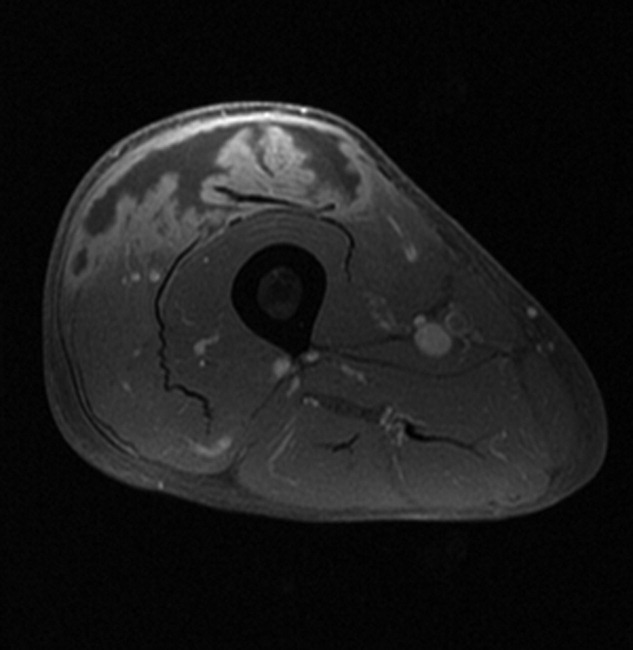

A 61‐year‐old healthy man presented with recurrent right wrist pain. The patient underwent unsuccessful carpal tunnel surgery and pathology revealed granulomatous inflammation. With worsening pain and new nodular inflammation, prednisone and azathioprine were prescribed for presumed sarcoidosis. Subsequently, right arm ulceration developed (Figure 1), and wound and blood cultures revealed Sporothrix schenkii. Immunosuppressive medications were stopped, but the ulceration progressed and ultimately involved the entire arm (Figure 2). New lower‐extremity fluid collections seen on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) MRI (Figures 3, 4) prompted several surgical debridements. Multiple abscesses formed in all extremities despite amphotericin and itraconazole therapy. The patient was eventually discharged with ongoing amphotericin and plans for surveillance imaging and repeated debridements.

Sporothrix schenckii is a dimorphic fungus often associated with cutaneous infections of the extremities in gardeners. These infections are definitively treated with oral azole medications or topical potassium iodide. Disseminated sporotrichosis is almost exclusively seen in immunosuppressed patients including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)1 and hematologic malignancies.2 Iatrogenic immunosuppression from chemotherapy or corticosteroids can also place a patient at risk for disseminated disease. Disseminated sporotrichosis is extremely difficult to manage with significant morbidity and mortality; fatal cases are commonly reported in the literature.3

- ,,,.Cutaneous and meningeal sporotrichosis in a HIV patient.Rev Iberoam Micol.2007;24(2):161–163.

- ,,.Systemic sporotrichosis.Ann Intern Med.1970;73(1):23–30.

- ,,,,.Fatal sporotrichosis.Cutis.2006;78(4):253–256.

A 61‐year‐old healthy man presented with recurrent right wrist pain. The patient underwent unsuccessful carpal tunnel surgery and pathology revealed granulomatous inflammation. With worsening pain and new nodular inflammation, prednisone and azathioprine were prescribed for presumed sarcoidosis. Subsequently, right arm ulceration developed (Figure 1), and wound and blood cultures revealed Sporothrix schenkii. Immunosuppressive medications were stopped, but the ulceration progressed and ultimately involved the entire arm (Figure 2). New lower‐extremity fluid collections seen on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) MRI (Figures 3, 4) prompted several surgical debridements. Multiple abscesses formed in all extremities despite amphotericin and itraconazole therapy. The patient was eventually discharged with ongoing amphotericin and plans for surveillance imaging and repeated debridements.

Sporothrix schenckii is a dimorphic fungus often associated with cutaneous infections of the extremities in gardeners. These infections are definitively treated with oral azole medications or topical potassium iodide. Disseminated sporotrichosis is almost exclusively seen in immunosuppressed patients including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)1 and hematologic malignancies.2 Iatrogenic immunosuppression from chemotherapy or corticosteroids can also place a patient at risk for disseminated disease. Disseminated sporotrichosis is extremely difficult to manage with significant morbidity and mortality; fatal cases are commonly reported in the literature.3

A 61‐year‐old healthy man presented with recurrent right wrist pain. The patient underwent unsuccessful carpal tunnel surgery and pathology revealed granulomatous inflammation. With worsening pain and new nodular inflammation, prednisone and azathioprine were prescribed for presumed sarcoidosis. Subsequently, right arm ulceration developed (Figure 1), and wound and blood cultures revealed Sporothrix schenkii. Immunosuppressive medications were stopped, but the ulceration progressed and ultimately involved the entire arm (Figure 2). New lower‐extremity fluid collections seen on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) MRI (Figures 3, 4) prompted several surgical debridements. Multiple abscesses formed in all extremities despite amphotericin and itraconazole therapy. The patient was eventually discharged with ongoing amphotericin and plans for surveillance imaging and repeated debridements.

Sporothrix schenckii is a dimorphic fungus often associated with cutaneous infections of the extremities in gardeners. These infections are definitively treated with oral azole medications or topical potassium iodide. Disseminated sporotrichosis is almost exclusively seen in immunosuppressed patients including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)1 and hematologic malignancies.2 Iatrogenic immunosuppression from chemotherapy or corticosteroids can also place a patient at risk for disseminated disease. Disseminated sporotrichosis is extremely difficult to manage with significant morbidity and mortality; fatal cases are commonly reported in the literature.3

- ,,,.Cutaneous and meningeal sporotrichosis in a HIV patient.Rev Iberoam Micol.2007;24(2):161–163.

- ,,.Systemic sporotrichosis.Ann Intern Med.1970;73(1):23–30.

- ,,,,.Fatal sporotrichosis.Cutis.2006;78(4):253–256.

- ,,,.Cutaneous and meningeal sporotrichosis in a HIV patient.Rev Iberoam Micol.2007;24(2):161–163.

- ,,.Systemic sporotrichosis.Ann Intern Med.1970;73(1):23–30.

- ,,,,.Fatal sporotrichosis.Cutis.2006;78(4):253–256.

Port‐A‐Cath Embolization

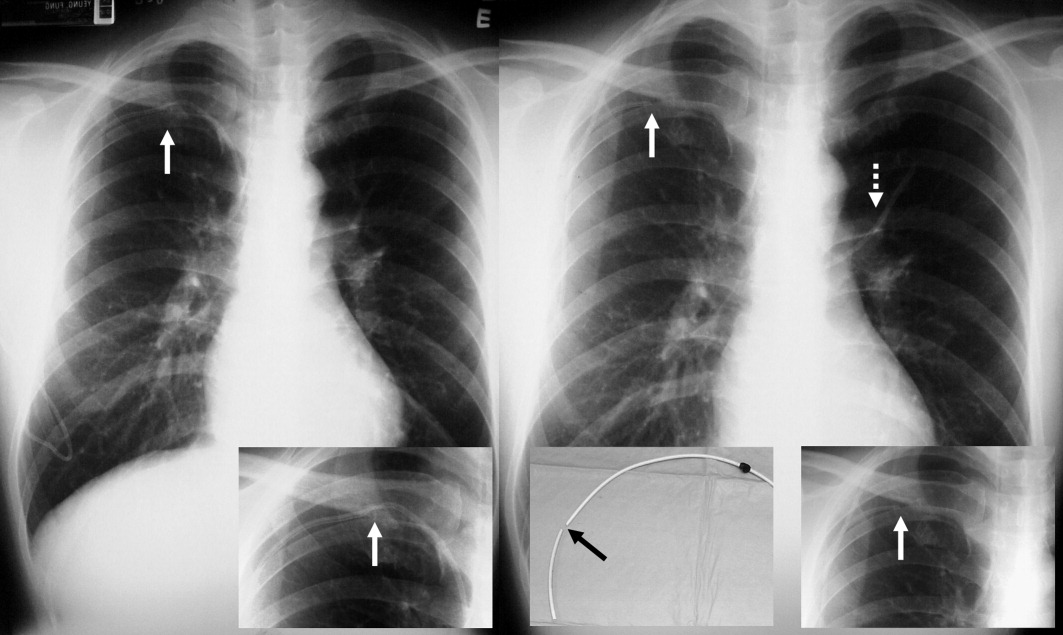

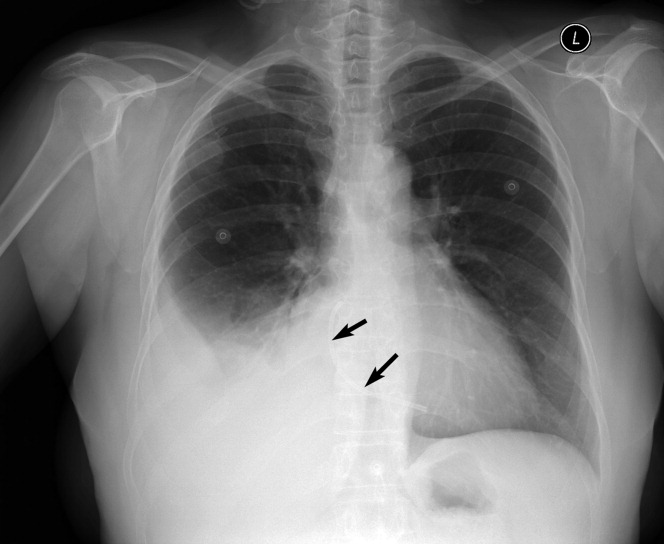

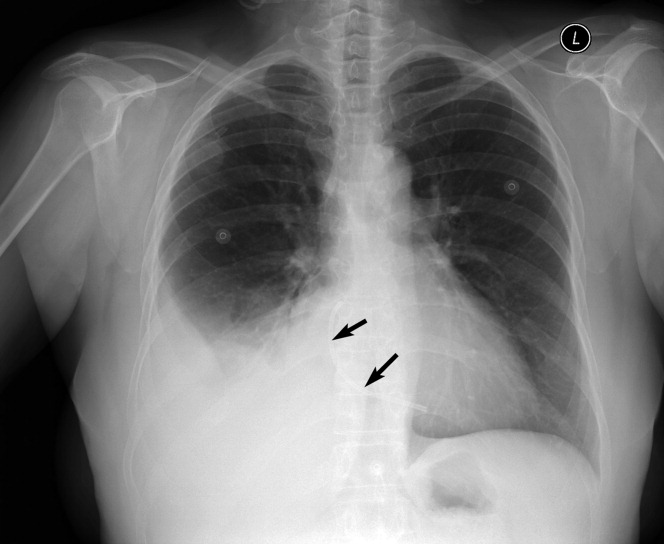

A 59‐year‐old white female, with a 3‐year history of Port‐A‐Cath (PAC) placement for abdominal mesothelioma, presented with 2 episodes of cardiac palpitations. The onset of palpitations occurred 2 days prior to admission, following 15 minutes of vigorous but failed attempts to access the PAC with normal saline and tissue plasminogen activator at her oncologist's office. Although asymptomatic at the time of manipulation, each episode was triggered by subsequent exertion, lasting for about 1 minute, and not associated with chest pain. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm and occasional premature ventricular contractions. A chest x‐ray showed a catheter fragment spanning the right atrium and ventricle (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a 10‐cm dislodged catheter (Figure 2). Following emergent catheter retrieval via right‐sided heart catheterization, the patient's symptoms resolved. At least 42 cases of catheter embolization have been reported in the recent literature.1 Of these cases, only 7% had palpitations. Although rare, catheter fracture should be considered in patients with palpitations and history of indwelling venous catheter.

- ,.Ventricular tachycardia secondary to Port‐A‐Cath fracture and embolization.J Emerg Med.2003;24:29–34.

A 59‐year‐old white female, with a 3‐year history of Port‐A‐Cath (PAC) placement for abdominal mesothelioma, presented with 2 episodes of cardiac palpitations. The onset of palpitations occurred 2 days prior to admission, following 15 minutes of vigorous but failed attempts to access the PAC with normal saline and tissue plasminogen activator at her oncologist's office. Although asymptomatic at the time of manipulation, each episode was triggered by subsequent exertion, lasting for about 1 minute, and not associated with chest pain. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm and occasional premature ventricular contractions. A chest x‐ray showed a catheter fragment spanning the right atrium and ventricle (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a 10‐cm dislodged catheter (Figure 2). Following emergent catheter retrieval via right‐sided heart catheterization, the patient's symptoms resolved. At least 42 cases of catheter embolization have been reported in the recent literature.1 Of these cases, only 7% had palpitations. Although rare, catheter fracture should be considered in patients with palpitations and history of indwelling venous catheter.

A 59‐year‐old white female, with a 3‐year history of Port‐A‐Cath (PAC) placement for abdominal mesothelioma, presented with 2 episodes of cardiac palpitations. The onset of palpitations occurred 2 days prior to admission, following 15 minutes of vigorous but failed attempts to access the PAC with normal saline and tissue plasminogen activator at her oncologist's office. Although asymptomatic at the time of manipulation, each episode was triggered by subsequent exertion, lasting for about 1 minute, and not associated with chest pain. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm and occasional premature ventricular contractions. A chest x‐ray showed a catheter fragment spanning the right atrium and ventricle (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a 10‐cm dislodged catheter (Figure 2). Following emergent catheter retrieval via right‐sided heart catheterization, the patient's symptoms resolved. At least 42 cases of catheter embolization have been reported in the recent literature.1 Of these cases, only 7% had palpitations. Although rare, catheter fracture should be considered in patients with palpitations and history of indwelling venous catheter.

- ,.Ventricular tachycardia secondary to Port‐A‐Cath fracture and embolization.J Emerg Med.2003;24:29–34.

- ,.Ventricular tachycardia secondary to Port‐A‐Cath fracture and embolization.J Emerg Med.2003;24:29–34.