User login

Acute Pancreatitis with Eruptive Xanthomas

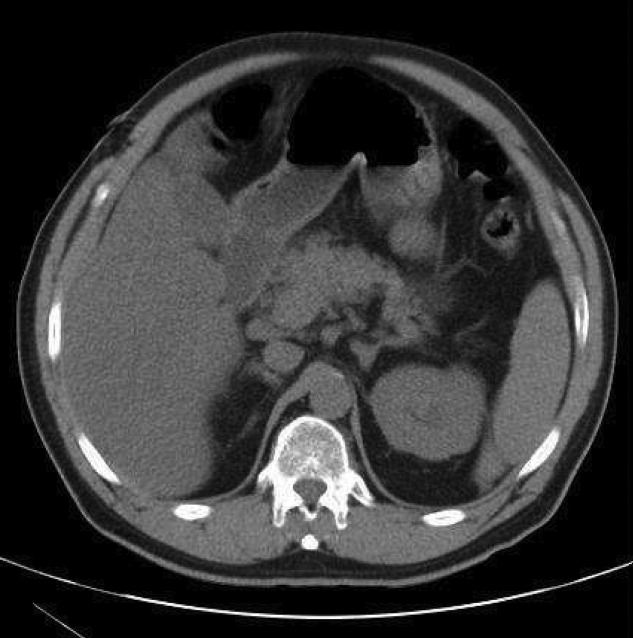

A 54‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of epigastric abdominal pain. He also described 1 month of a nonpruritic but tender rash, on his right elbow, abdomen, buttocks, posterior thighs, and knees. He was obese with a past medical history remarkable for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hemoglobin A1C of 12.7. His abdomen was tender to palpation in the epigastric area with no rebound or guarding. Skin examination demonstrated multiple yellow waxy papules on the extensor surfaces of his arms, abdomen, thighs, knees, and buttocks, consistent with eruptive xanthomas (Figure 1). Laboratory values were significant for lipase at 852 g/L (normal, 8‐78 g/L) and triglycerides at 6200 mg/dL. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast demonstrated extensive inflammatory changes surrounding the head of the pancreas, consistent with acute pancreatitis (Figure 2). The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia was made. Dietary and pharmacologic interventions helped decrease the triglyceride level and his rash and abdominal pain were improved at outpatient follow‐up 2 weeks later.

Hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of acute pancreatitis.1 Eruptive xanthomas can be associated with primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia, particularly in the setting of poorly controlled diabetes.2 The risk of acute pancreatitis and eruptive xanthomas increases when the level of serum triglyceride reaches the thousands.

Rapid recognition of eruptive xanthomas can assist in identifying the etiology of acute pancreatitis.

- .Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. [Review].Gastroenterol Clin North Am.1990;19(4):783–791.

- .Xanthomas and hyperlipidemias.J Am Acad Dermatol.1985;13(1):1–30.

A 54‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of epigastric abdominal pain. He also described 1 month of a nonpruritic but tender rash, on his right elbow, abdomen, buttocks, posterior thighs, and knees. He was obese with a past medical history remarkable for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hemoglobin A1C of 12.7. His abdomen was tender to palpation in the epigastric area with no rebound or guarding. Skin examination demonstrated multiple yellow waxy papules on the extensor surfaces of his arms, abdomen, thighs, knees, and buttocks, consistent with eruptive xanthomas (Figure 1). Laboratory values were significant for lipase at 852 g/L (normal, 8‐78 g/L) and triglycerides at 6200 mg/dL. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast demonstrated extensive inflammatory changes surrounding the head of the pancreas, consistent with acute pancreatitis (Figure 2). The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia was made. Dietary and pharmacologic interventions helped decrease the triglyceride level and his rash and abdominal pain were improved at outpatient follow‐up 2 weeks later.

Hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of acute pancreatitis.1 Eruptive xanthomas can be associated with primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia, particularly in the setting of poorly controlled diabetes.2 The risk of acute pancreatitis and eruptive xanthomas increases when the level of serum triglyceride reaches the thousands.

Rapid recognition of eruptive xanthomas can assist in identifying the etiology of acute pancreatitis.

A 54‐year‐old man presented with a 1‐day history of epigastric abdominal pain. He also described 1 month of a nonpruritic but tender rash, on his right elbow, abdomen, buttocks, posterior thighs, and knees. He was obese with a past medical history remarkable for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and hemoglobin A1C of 12.7. His abdomen was tender to palpation in the epigastric area with no rebound or guarding. Skin examination demonstrated multiple yellow waxy papules on the extensor surfaces of his arms, abdomen, thighs, knees, and buttocks, consistent with eruptive xanthomas (Figure 1). Laboratory values were significant for lipase at 852 g/L (normal, 8‐78 g/L) and triglycerides at 6200 mg/dL. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast demonstrated extensive inflammatory changes surrounding the head of the pancreas, consistent with acute pancreatitis (Figure 2). The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia was made. Dietary and pharmacologic interventions helped decrease the triglyceride level and his rash and abdominal pain were improved at outpatient follow‐up 2 weeks later.

Hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of acute pancreatitis.1 Eruptive xanthomas can be associated with primary and secondary hypertriglyceridemia, particularly in the setting of poorly controlled diabetes.2 The risk of acute pancreatitis and eruptive xanthomas increases when the level of serum triglyceride reaches the thousands.

Rapid recognition of eruptive xanthomas can assist in identifying the etiology of acute pancreatitis.

- .Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. [Review].Gastroenterol Clin North Am.1990;19(4):783–791.

- .Xanthomas and hyperlipidemias.J Am Acad Dermatol.1985;13(1):1–30.

- .Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. [Review].Gastroenterol Clin North Am.1990;19(4):783–791.

- .Xanthomas and hyperlipidemias.J Am Acad Dermatol.1985;13(1):1–30.

Pretibial Myxedema

An 83‐year‐old female reported increased swelling of her legs over the past 2 years. She noted temperature intolerance, low energy, and constipation, but denied any hair loss or nail changes. On exam, she had marked bilateral lower extremity edema that was predominately nonpitting. Overlying the edema there were thickened, well‐defined plaques with a peau d'orange appearance surrounded by brown, thin plaques on the pretibial areas sparing the dorsum of the feet (Figure 1). A punch biopsy was obtained and demonstrated increased deposition of mucin throughout the dermis along with fragmentation and increased numbers of elastic fibers consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema. Measured thyrotropin level was elevated at 3.9 U/mL (normal, 0.3‐3.8 U/mL), consistent with hypothyroidism. This is a severe example of pretibial myxedema, or infiltrative dermopathy, which can occur, more commonly, in the setting of Graves' disease or, in rare circumstances, hypothyroidism.1 Myxedema results from the accumulation of hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate in the dermis.2 Treatment is difficult and includes topical glucocorticoids under occlusion and, if indicated, thyroid corrective therapy.3

- .Pretibial myxedema.Dermatol Online J.7(1):18.

- ,,.Pretibial myxoedema: a manifestation of lymphoedema?Lancet.1993;341(8842):403–404.

- .Successful treatment of chronic skin diseases with clobetasol propionate and a hydrocolloid occlusive dressing.Acta Derm Venereol.1992;72(1):69–71.

An 83‐year‐old female reported increased swelling of her legs over the past 2 years. She noted temperature intolerance, low energy, and constipation, but denied any hair loss or nail changes. On exam, she had marked bilateral lower extremity edema that was predominately nonpitting. Overlying the edema there were thickened, well‐defined plaques with a peau d'orange appearance surrounded by brown, thin plaques on the pretibial areas sparing the dorsum of the feet (Figure 1). A punch biopsy was obtained and demonstrated increased deposition of mucin throughout the dermis along with fragmentation and increased numbers of elastic fibers consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema. Measured thyrotropin level was elevated at 3.9 U/mL (normal, 0.3‐3.8 U/mL), consistent with hypothyroidism. This is a severe example of pretibial myxedema, or infiltrative dermopathy, which can occur, more commonly, in the setting of Graves' disease or, in rare circumstances, hypothyroidism.1 Myxedema results from the accumulation of hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate in the dermis.2 Treatment is difficult and includes topical glucocorticoids under occlusion and, if indicated, thyroid corrective therapy.3

An 83‐year‐old female reported increased swelling of her legs over the past 2 years. She noted temperature intolerance, low energy, and constipation, but denied any hair loss or nail changes. On exam, she had marked bilateral lower extremity edema that was predominately nonpitting. Overlying the edema there were thickened, well‐defined plaques with a peau d'orange appearance surrounded by brown, thin plaques on the pretibial areas sparing the dorsum of the feet (Figure 1). A punch biopsy was obtained and demonstrated increased deposition of mucin throughout the dermis along with fragmentation and increased numbers of elastic fibers consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema. Measured thyrotropin level was elevated at 3.9 U/mL (normal, 0.3‐3.8 U/mL), consistent with hypothyroidism. This is a severe example of pretibial myxedema, or infiltrative dermopathy, which can occur, more commonly, in the setting of Graves' disease or, in rare circumstances, hypothyroidism.1 Myxedema results from the accumulation of hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate in the dermis.2 Treatment is difficult and includes topical glucocorticoids under occlusion and, if indicated, thyroid corrective therapy.3

- .Pretibial myxedema.Dermatol Online J.7(1):18.

- ,,.Pretibial myxoedema: a manifestation of lymphoedema?Lancet.1993;341(8842):403–404.

- .Successful treatment of chronic skin diseases with clobetasol propionate and a hydrocolloid occlusive dressing.Acta Derm Venereol.1992;72(1):69–71.

- .Pretibial myxedema.Dermatol Online J.7(1):18.

- ,,.Pretibial myxoedema: a manifestation of lymphoedema?Lancet.1993;341(8842):403–404.

- .Successful treatment of chronic skin diseases with clobetasol propionate and a hydrocolloid occlusive dressing.Acta Derm Venereol.1992;72(1):69–71.

Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

A 79‐year‐old woman presented from a nursing home with unusual lower extremity skin changes. Her medical history included congestive heart failure, morbid obesity, chronic lymphedema, and deep vein thrombosis with inferior vena cava filter placement. There was no history of cellulitis, filariasis, or travel to endemic areas. The patient was afebrile without adenopathy and had bilateral lower extremity edema with hyperpigmented, cobble‐stoned, hyperkeratotic skin and verrucous nodules on the inner thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa secondary to longstanding lymphedema and obesity was diagnosed by the dermatology consultant. The patient was treated with compression stockings and topical emollients. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a rare disorder secondary to chronic noninfectious or recurrent cellulitic lymphedema that results in hyperplastic fibrotic dermal changes.1 Diagnosis is clinical, but biopsy to exclude malignancies such as Stewart‐Treves syndrome is needed in atypical cases.2 Treatment options include compression stockings, limb elevation, topical keratolytics, emollients, retinoids, and surgical debridement.2, 3

- ,,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa.Cutis.1998;62:77–80.

- ,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review.Am J Clin Dermatol.2008;9:141–146.

- ,,,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement.Dermatol Surg.2004;30:939–941.

A 79‐year‐old woman presented from a nursing home with unusual lower extremity skin changes. Her medical history included congestive heart failure, morbid obesity, chronic lymphedema, and deep vein thrombosis with inferior vena cava filter placement. There was no history of cellulitis, filariasis, or travel to endemic areas. The patient was afebrile without adenopathy and had bilateral lower extremity edema with hyperpigmented, cobble‐stoned, hyperkeratotic skin and verrucous nodules on the inner thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa secondary to longstanding lymphedema and obesity was diagnosed by the dermatology consultant. The patient was treated with compression stockings and topical emollients. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a rare disorder secondary to chronic noninfectious or recurrent cellulitic lymphedema that results in hyperplastic fibrotic dermal changes.1 Diagnosis is clinical, but biopsy to exclude malignancies such as Stewart‐Treves syndrome is needed in atypical cases.2 Treatment options include compression stockings, limb elevation, topical keratolytics, emollients, retinoids, and surgical debridement.2, 3

A 79‐year‐old woman presented from a nursing home with unusual lower extremity skin changes. Her medical history included congestive heart failure, morbid obesity, chronic lymphedema, and deep vein thrombosis with inferior vena cava filter placement. There was no history of cellulitis, filariasis, or travel to endemic areas. The patient was afebrile without adenopathy and had bilateral lower extremity edema with hyperpigmented, cobble‐stoned, hyperkeratotic skin and verrucous nodules on the inner thighs (Figures 1 and 2). Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa secondary to longstanding lymphedema and obesity was diagnosed by the dermatology consultant. The patient was treated with compression stockings and topical emollients. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a rare disorder secondary to chronic noninfectious or recurrent cellulitic lymphedema that results in hyperplastic fibrotic dermal changes.1 Diagnosis is clinical, but biopsy to exclude malignancies such as Stewart‐Treves syndrome is needed in atypical cases.2 Treatment options include compression stockings, limb elevation, topical keratolytics, emollients, retinoids, and surgical debridement.2, 3

- ,,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa.Cutis.1998;62:77–80.

- ,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review.Am J Clin Dermatol.2008;9:141–146.

- ,,,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement.Dermatol Surg.2004;30:939–941.

- ,,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa.Cutis.1998;62:77–80.

- ,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review.Am J Clin Dermatol.2008;9:141–146.

- ,,,.Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement.Dermatol Surg.2004;30:939–941.

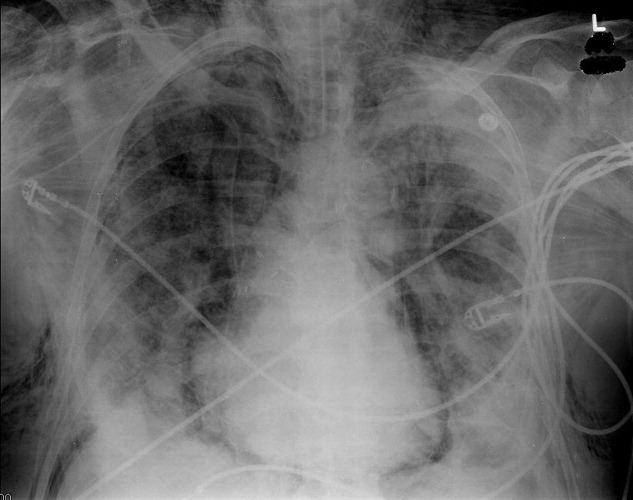

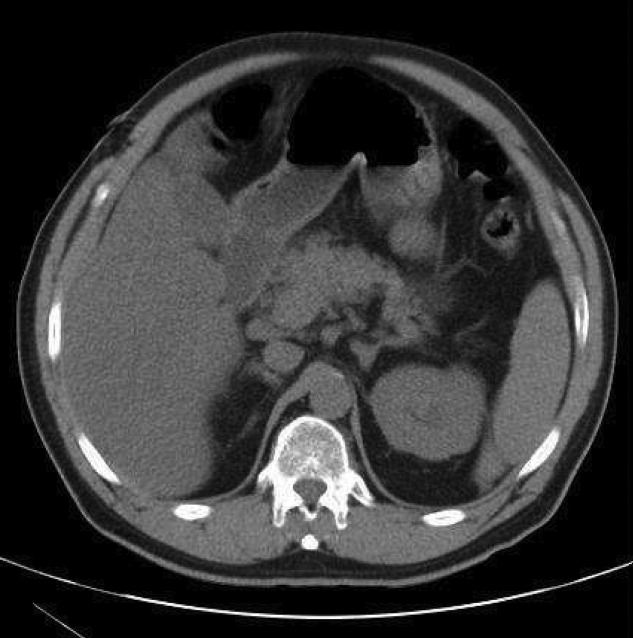

Pneumomediastinum and Pneumopericardium

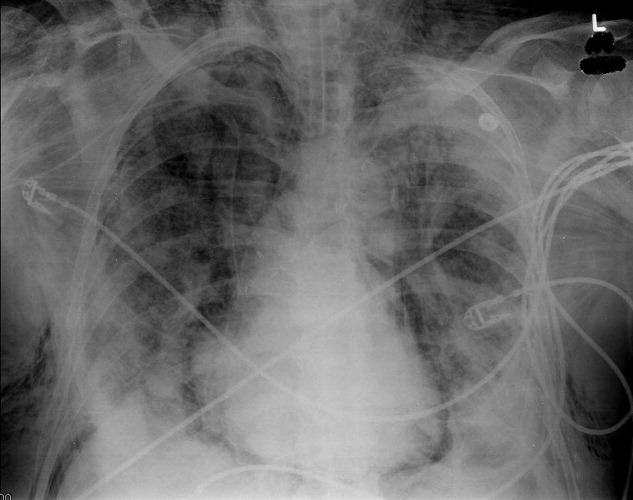

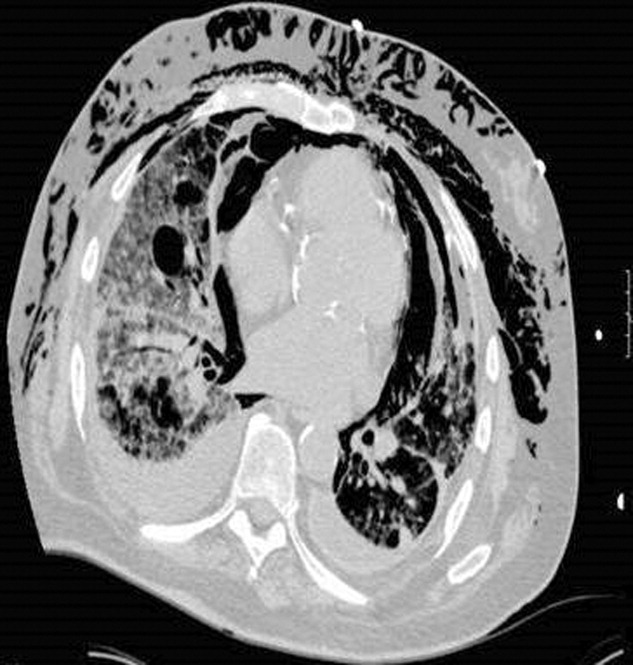

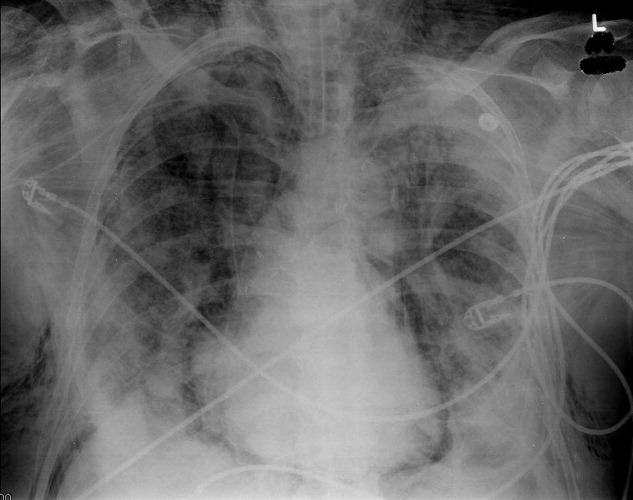

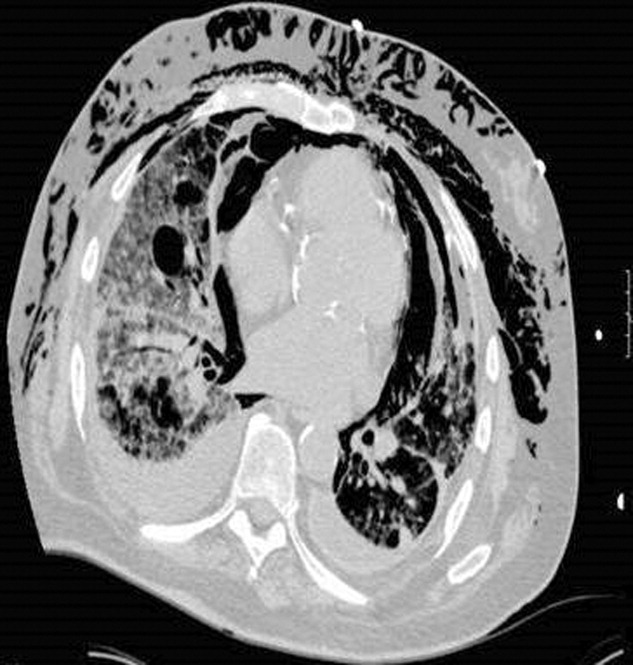

A 73‐year‐old male presented with acute congestive heart failure and non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction. His initial chest x‐ray and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated pulmonary vascular congestion and alveolar infiltrates, and he promptly underwent cardiac catheterization with placement of a coronary stent. Subsequently, his respiratory status deteriorated, and repeat films and chest CT demonstrated extensive pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium (Figures 13). The patient was intubated, and bronchoscopy and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy were performed, but demonstrated no evidence of perforation that could cause such an air leak. There was no evidence of tamponade, clinically or on echocardiogram. His condition worsened abruptly, and he expired following a cardiac arrest. Postmortem, the team considered that the extensive air leak could have been caused by catheterization, stent placement, central line placement, or mediastinitis or pericarditis causing microscopic fistulae. The patient's tracheal aspirate and biopsy grew Candida albicans but no evidence of invasive candidiasis was found on autopsy. No definitive etiology was found.

In contrast to pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium is a rare condition and its pathophysiology is not well understood. Most cases have been reported in newborns receiving mechanical ventilation. In adults, the condition occurs due to chest trauma, or can be iatrogenic secondary to laparoscopy, bronchoscopy, or endotracheal intubation. There have been case reports of pneumopericardium after cardiac catheterization and central line placement.1, 2 Other causes include lung transplant, esophageal perforation, severe asthma, positive pressure ventilation, and pericarditis (eg, histoplasmosis and tuberculosis).3, 4 Clinical findings include distant heart sounds, shifting precordial tympany, and a succussion splash with metallic tinkling (known as mill wheel murmur) in hydropneumopericardium.5 Chest CT can distinguish pneumopericardium from pneumomediastinum: with the former, the air changes position when the patient adopts a supine position.6 Cardiac tamponade can occur in up to 37% of cases, and pericardiocentesis or pericardial tube drainage in these cases can be lifesaving.7

- ,,,,.[Cardiac tamponade and central venous catheterization].Ann Fr Anesth Reanim.1992;11:201–204. [French]

- ,,,.Pneumopericardium as a complication of balloon atrial septostomy.Pediatr Cardiol.1987;8:135–137.

- ,,,,.Continuous left hemidiaphragm sign revisited: a case of spontaneous pneumopericardium and literature review.Heart.2002;88:e5.

- ,.Tension pneumopericardium: a case report and a review of the literature.Am Surg.2006;72:330–331.

- Symptoms and signs of syndromes associated with mill wheel murmurs.NC Med J.1988;49:569–572.

- ,.Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs.AJR Am J Roentgenol.1996;166:1041–1048.

- ,,,,.Cardiac tamponade without pericardial effusion after blunt chest trauma.Am Heart J.1996;131:198–200.

A 73‐year‐old male presented with acute congestive heart failure and non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction. His initial chest x‐ray and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated pulmonary vascular congestion and alveolar infiltrates, and he promptly underwent cardiac catheterization with placement of a coronary stent. Subsequently, his respiratory status deteriorated, and repeat films and chest CT demonstrated extensive pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium (Figures 13). The patient was intubated, and bronchoscopy and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy were performed, but demonstrated no evidence of perforation that could cause such an air leak. There was no evidence of tamponade, clinically or on echocardiogram. His condition worsened abruptly, and he expired following a cardiac arrest. Postmortem, the team considered that the extensive air leak could have been caused by catheterization, stent placement, central line placement, or mediastinitis or pericarditis causing microscopic fistulae. The patient's tracheal aspirate and biopsy grew Candida albicans but no evidence of invasive candidiasis was found on autopsy. No definitive etiology was found.

In contrast to pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium is a rare condition and its pathophysiology is not well understood. Most cases have been reported in newborns receiving mechanical ventilation. In adults, the condition occurs due to chest trauma, or can be iatrogenic secondary to laparoscopy, bronchoscopy, or endotracheal intubation. There have been case reports of pneumopericardium after cardiac catheterization and central line placement.1, 2 Other causes include lung transplant, esophageal perforation, severe asthma, positive pressure ventilation, and pericarditis (eg, histoplasmosis and tuberculosis).3, 4 Clinical findings include distant heart sounds, shifting precordial tympany, and a succussion splash with metallic tinkling (known as mill wheel murmur) in hydropneumopericardium.5 Chest CT can distinguish pneumopericardium from pneumomediastinum: with the former, the air changes position when the patient adopts a supine position.6 Cardiac tamponade can occur in up to 37% of cases, and pericardiocentesis or pericardial tube drainage in these cases can be lifesaving.7

A 73‐year‐old male presented with acute congestive heart failure and non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction. His initial chest x‐ray and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated pulmonary vascular congestion and alveolar infiltrates, and he promptly underwent cardiac catheterization with placement of a coronary stent. Subsequently, his respiratory status deteriorated, and repeat films and chest CT demonstrated extensive pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium (Figures 13). The patient was intubated, and bronchoscopy and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy were performed, but demonstrated no evidence of perforation that could cause such an air leak. There was no evidence of tamponade, clinically or on echocardiogram. His condition worsened abruptly, and he expired following a cardiac arrest. Postmortem, the team considered that the extensive air leak could have been caused by catheterization, stent placement, central line placement, or mediastinitis or pericarditis causing microscopic fistulae. The patient's tracheal aspirate and biopsy grew Candida albicans but no evidence of invasive candidiasis was found on autopsy. No definitive etiology was found.

In contrast to pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium is a rare condition and its pathophysiology is not well understood. Most cases have been reported in newborns receiving mechanical ventilation. In adults, the condition occurs due to chest trauma, or can be iatrogenic secondary to laparoscopy, bronchoscopy, or endotracheal intubation. There have been case reports of pneumopericardium after cardiac catheterization and central line placement.1, 2 Other causes include lung transplant, esophageal perforation, severe asthma, positive pressure ventilation, and pericarditis (eg, histoplasmosis and tuberculosis).3, 4 Clinical findings include distant heart sounds, shifting precordial tympany, and a succussion splash with metallic tinkling (known as mill wheel murmur) in hydropneumopericardium.5 Chest CT can distinguish pneumopericardium from pneumomediastinum: with the former, the air changes position when the patient adopts a supine position.6 Cardiac tamponade can occur in up to 37% of cases, and pericardiocentesis or pericardial tube drainage in these cases can be lifesaving.7

- ,,,,.[Cardiac tamponade and central venous catheterization].Ann Fr Anesth Reanim.1992;11:201–204. [French]

- ,,,.Pneumopericardium as a complication of balloon atrial septostomy.Pediatr Cardiol.1987;8:135–137.

- ,,,,.Continuous left hemidiaphragm sign revisited: a case of spontaneous pneumopericardium and literature review.Heart.2002;88:e5.

- ,.Tension pneumopericardium: a case report and a review of the literature.Am Surg.2006;72:330–331.

- Symptoms and signs of syndromes associated with mill wheel murmurs.NC Med J.1988;49:569–572.

- ,.Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs.AJR Am J Roentgenol.1996;166:1041–1048.

- ,,,,.Cardiac tamponade without pericardial effusion after blunt chest trauma.Am Heart J.1996;131:198–200.

- ,,,,.[Cardiac tamponade and central venous catheterization].Ann Fr Anesth Reanim.1992;11:201–204. [French]

- ,,,.Pneumopericardium as a complication of balloon atrial septostomy.Pediatr Cardiol.1987;8:135–137.

- ,,,,.Continuous left hemidiaphragm sign revisited: a case of spontaneous pneumopericardium and literature review.Heart.2002;88:e5.

- ,.Tension pneumopericardium: a case report and a review of the literature.Am Surg.2006;72:330–331.

- Symptoms and signs of syndromes associated with mill wheel murmurs.NC Med J.1988;49:569–572.

- ,.Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs.AJR Am J Roentgenol.1996;166:1041–1048.

- ,,,,.Cardiac tamponade without pericardial effusion after blunt chest trauma.Am Heart J.1996;131:198–200.

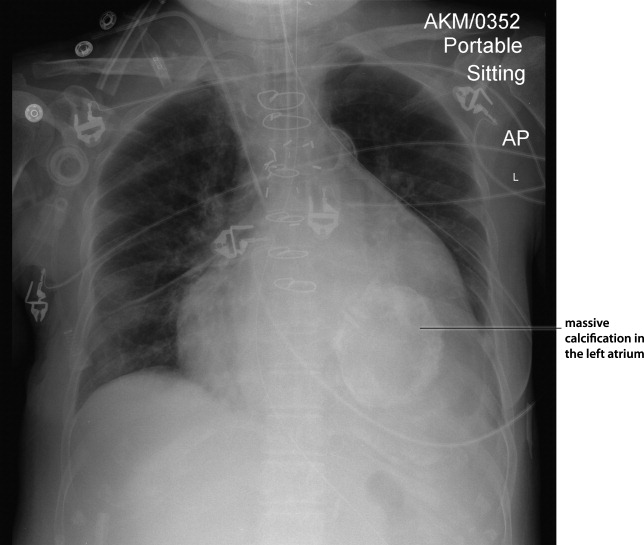

Myocardial Calcification in ESRD

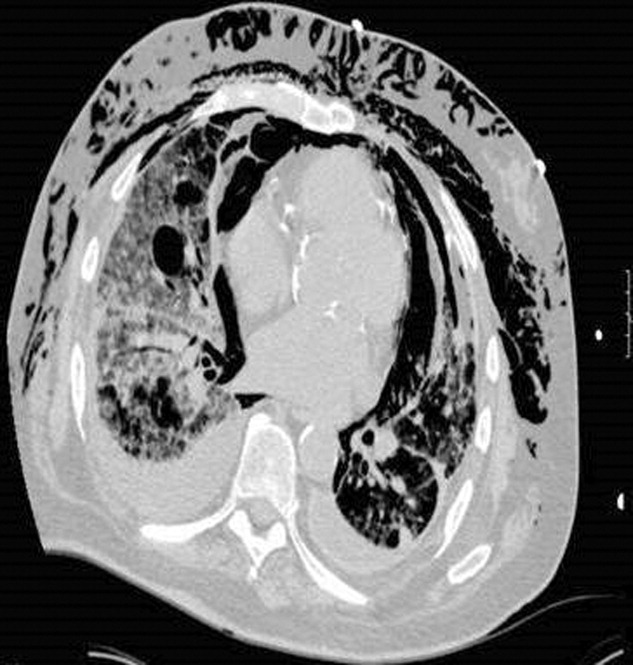

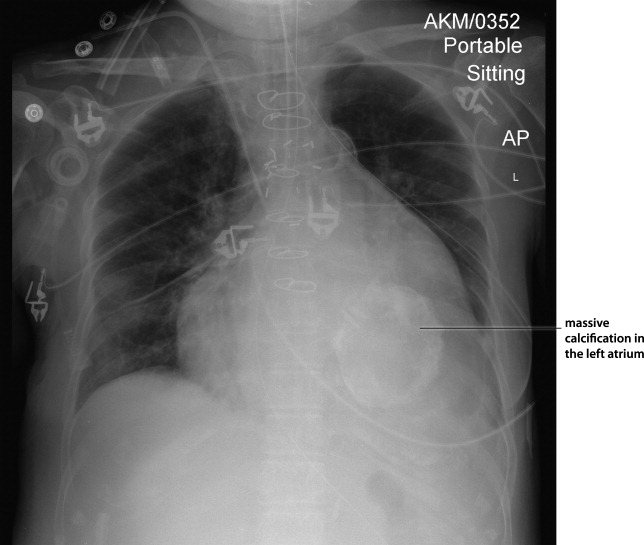

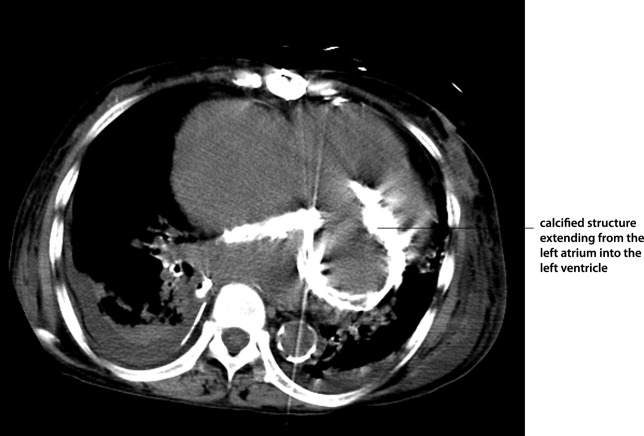

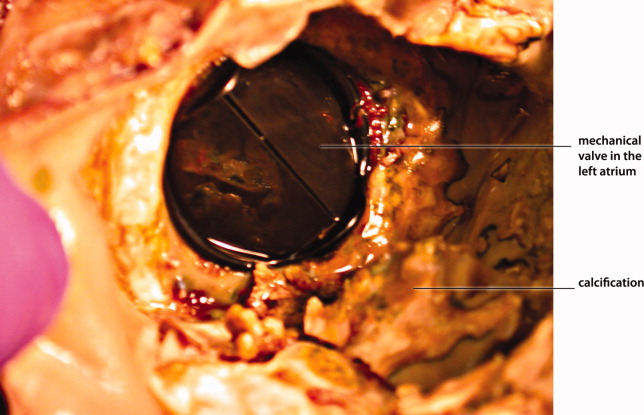

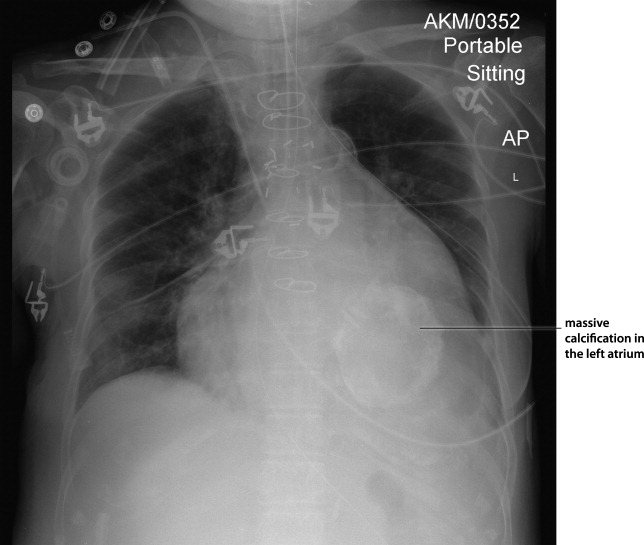

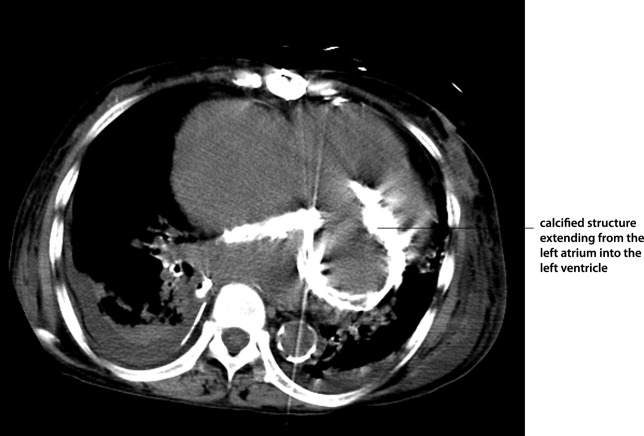

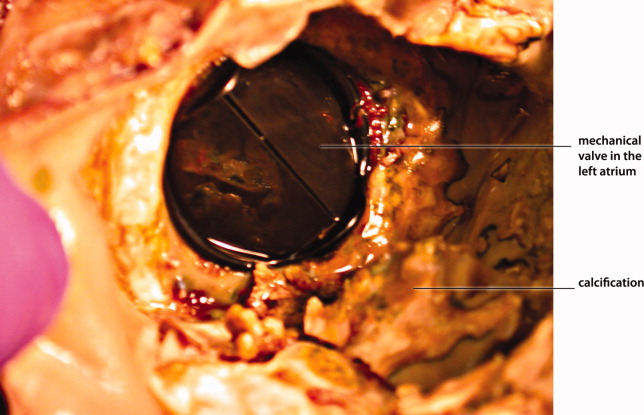

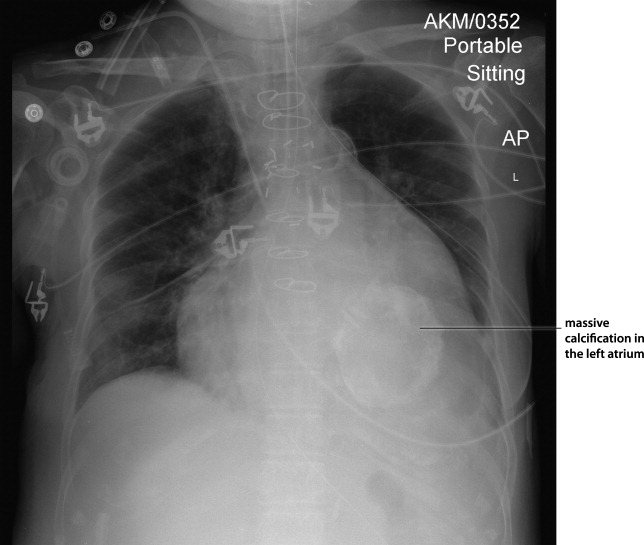

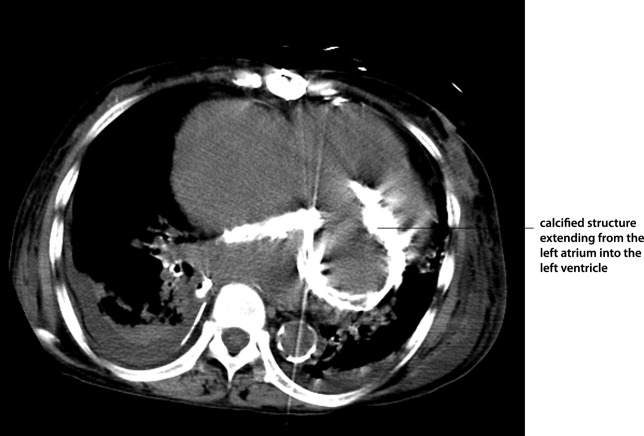

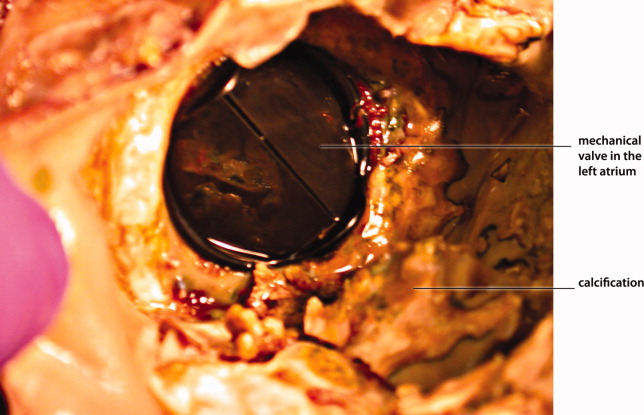

Myocardial calcification is very rare and has been associated with metastatic calcium deposition. A 57‐year‐old woman with end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) due to hypertension on peritoneal dialysis, coronary artery disease, mechanical valve from mitral stenosis without history of rheumatic disease, atrial fibrillation, and a positive tuberculin skin test presented with tuberculous peritonitis (culture confirmed) and calcifications of her heart. Her chest film showed a retrocardiac calcified lesion (Figure 1). Chest computed tomography (CT) showed cardiac hypertrophy with calcification of the left atrium and ventricle (Figure 2). She began antituberculosis medications but she died 1 month later. At autopsy, the cardiac tissue confirmed endocardial and myocardial calcifications without tuberculum bacilli (Figure 3).

Her ESRD led to an elevated calcium‐phosphate product, which more commonly causes vascular calcifications (calciphylaxis), but can lead to calcification of the cardiac tissue.1 Some other possible causes include myocardial infarction, myocardial fibrosis, rheumatic carditis, and caseous necrosis from tuberculosis.2 Treatment for massive cardiac calcification includes endoatriectomy and replacement of the mitral valve.

- ,,,.Soft tissue calcification in pediatric patients with end‐stage renal disease.Kidney Int.1990;38(5):931–936.

- ,.Calcifications of the heart.Radiol Clin North Am.2004;42(3):603–617,vi–vii.

Myocardial calcification is very rare and has been associated with metastatic calcium deposition. A 57‐year‐old woman with end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) due to hypertension on peritoneal dialysis, coronary artery disease, mechanical valve from mitral stenosis without history of rheumatic disease, atrial fibrillation, and a positive tuberculin skin test presented with tuberculous peritonitis (culture confirmed) and calcifications of her heart. Her chest film showed a retrocardiac calcified lesion (Figure 1). Chest computed tomography (CT) showed cardiac hypertrophy with calcification of the left atrium and ventricle (Figure 2). She began antituberculosis medications but she died 1 month later. At autopsy, the cardiac tissue confirmed endocardial and myocardial calcifications without tuberculum bacilli (Figure 3).

Her ESRD led to an elevated calcium‐phosphate product, which more commonly causes vascular calcifications (calciphylaxis), but can lead to calcification of the cardiac tissue.1 Some other possible causes include myocardial infarction, myocardial fibrosis, rheumatic carditis, and caseous necrosis from tuberculosis.2 Treatment for massive cardiac calcification includes endoatriectomy and replacement of the mitral valve.

Myocardial calcification is very rare and has been associated with metastatic calcium deposition. A 57‐year‐old woman with end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) due to hypertension on peritoneal dialysis, coronary artery disease, mechanical valve from mitral stenosis without history of rheumatic disease, atrial fibrillation, and a positive tuberculin skin test presented with tuberculous peritonitis (culture confirmed) and calcifications of her heart. Her chest film showed a retrocardiac calcified lesion (Figure 1). Chest computed tomography (CT) showed cardiac hypertrophy with calcification of the left atrium and ventricle (Figure 2). She began antituberculosis medications but she died 1 month later. At autopsy, the cardiac tissue confirmed endocardial and myocardial calcifications without tuberculum bacilli (Figure 3).

Her ESRD led to an elevated calcium‐phosphate product, which more commonly causes vascular calcifications (calciphylaxis), but can lead to calcification of the cardiac tissue.1 Some other possible causes include myocardial infarction, myocardial fibrosis, rheumatic carditis, and caseous necrosis from tuberculosis.2 Treatment for massive cardiac calcification includes endoatriectomy and replacement of the mitral valve.

- ,,,.Soft tissue calcification in pediatric patients with end‐stage renal disease.Kidney Int.1990;38(5):931–936.

- ,.Calcifications of the heart.Radiol Clin North Am.2004;42(3):603–617,vi–vii.

- ,,,.Soft tissue calcification in pediatric patients with end‐stage renal disease.Kidney Int.1990;38(5):931–936.

- ,.Calcifications of the heart.Radiol Clin North Am.2004;42(3):603–617,vi–vii.

Male with Arthritis and Scaly Skin Rash

A 32‐year‐old male presented to the emergency department complaining of pain and swelling in the right knee and left hand, along with a skin rash on both feet. He denied any fever or recent history of travel. Symptoms started 1 week before presentation. Recent medical history was significant for Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis 10 weeks prior, which had been successfully treated.

Physical examination revealed right knee effusion, dactylitis manifested by both swelling of the digits of the left hand and finger‐tip ulcerations (Figure 1), as well as hyperkeratotic plaques with erythematous bases on the soles of both feet, consistent with keratoderma blenorrhagica (Figure 2). Furthermore, scaly erythematous lesions over the penis and the scrotum were recognized, indicating circinate balanitis (Figure 3).

Laboratory tests including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were unremarkable aside from an elevated sedimentation rate and positive human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐B27.

The patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis (Reiter's syndrome). A treatment regimen was initiated consisting of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), prednisone, and sulfasalazine. Close outpatient follow‐up was established. Four months later, the patient remained debilitated by the disease, and etanercept was added resulting in significant improvement.

Reactive arthritis, also known as Reiter's syndrome, is an autoimmune disease that usually develops 2 to 4 weeks after a genitourinary or gastrointestinal infection. The classic triad of arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis does not occur in all patients. Diagnosis is made by medical history and clinical findings. Numerous therapeutic modalities have been used with variable success, including short‐term antibiotics, NSAIDs, systemic corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, cyclosporine, etretinate, and tumor‐necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors.

A 32‐year‐old male presented to the emergency department complaining of pain and swelling in the right knee and left hand, along with a skin rash on both feet. He denied any fever or recent history of travel. Symptoms started 1 week before presentation. Recent medical history was significant for Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis 10 weeks prior, which had been successfully treated.

Physical examination revealed right knee effusion, dactylitis manifested by both swelling of the digits of the left hand and finger‐tip ulcerations (Figure 1), as well as hyperkeratotic plaques with erythematous bases on the soles of both feet, consistent with keratoderma blenorrhagica (Figure 2). Furthermore, scaly erythematous lesions over the penis and the scrotum were recognized, indicating circinate balanitis (Figure 3).

Laboratory tests including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were unremarkable aside from an elevated sedimentation rate and positive human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐B27.

The patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis (Reiter's syndrome). A treatment regimen was initiated consisting of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), prednisone, and sulfasalazine. Close outpatient follow‐up was established. Four months later, the patient remained debilitated by the disease, and etanercept was added resulting in significant improvement.

Reactive arthritis, also known as Reiter's syndrome, is an autoimmune disease that usually develops 2 to 4 weeks after a genitourinary or gastrointestinal infection. The classic triad of arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis does not occur in all patients. Diagnosis is made by medical history and clinical findings. Numerous therapeutic modalities have been used with variable success, including short‐term antibiotics, NSAIDs, systemic corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, cyclosporine, etretinate, and tumor‐necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors.

A 32‐year‐old male presented to the emergency department complaining of pain and swelling in the right knee and left hand, along with a skin rash on both feet. He denied any fever or recent history of travel. Symptoms started 1 week before presentation. Recent medical history was significant for Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis 10 weeks prior, which had been successfully treated.

Physical examination revealed right knee effusion, dactylitis manifested by both swelling of the digits of the left hand and finger‐tip ulcerations (Figure 1), as well as hyperkeratotic plaques with erythematous bases on the soles of both feet, consistent with keratoderma blenorrhagica (Figure 2). Furthermore, scaly erythematous lesions over the penis and the scrotum were recognized, indicating circinate balanitis (Figure 3).

Laboratory tests including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were unremarkable aside from an elevated sedimentation rate and positive human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐B27.

The patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis (Reiter's syndrome). A treatment regimen was initiated consisting of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), prednisone, and sulfasalazine. Close outpatient follow‐up was established. Four months later, the patient remained debilitated by the disease, and etanercept was added resulting in significant improvement.

Reactive arthritis, also known as Reiter's syndrome, is an autoimmune disease that usually develops 2 to 4 weeks after a genitourinary or gastrointestinal infection. The classic triad of arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis does not occur in all patients. Diagnosis is made by medical history and clinical findings. Numerous therapeutic modalities have been used with variable success, including short‐term antibiotics, NSAIDs, systemic corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, cyclosporine, etretinate, and tumor‐necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors.

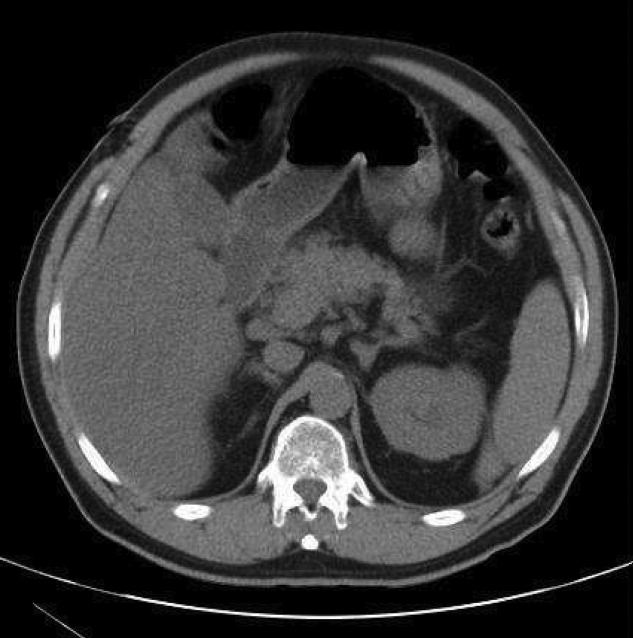

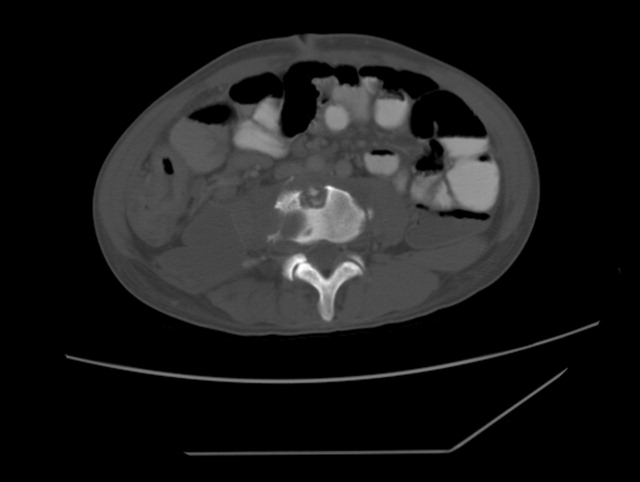

A Meal to Remember

A previously healthy 50‐year‐old man was eating a meal of rigatoni and shrimp at his favorite San Francisco restaurant when he suddenly developed severe pain in his throat followed a short time later by pleuritic chest pain localized to the anterior right chest. He completed his meal and then sought medical attention in the Emergency Department. He was in mild distress secondary to pain but his physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 15,300/mm3 with 86% neutrophils. A chest X‐ray, electrocardiogram, cardiac enzymes, and ventilation/perfusion scan were all normal. Because there was suspicion of an ingested foreign body, an abdominal radiograph was obtained which revealed a 2‐cm trapezoidal foreign body in the right lower quadrant (Figure 1; arrow). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed air in the mediastinum consistent with esophageal perforation (Figure 2). One day after admission a Hypaque esophagram showed trauma to the posterior cervical region of the esophagus, but no leak of contrast material into the mediastinum. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and nothing by mouth. Stools were screened and 48 hours after admission the patient (painlessly) passed a piece of glass with a very sharp point (Figure 3) correlating in size and shape to the foreign body seen on the previous abdominal radiograph. The glass had apparently fallen into the patient's restaurant meal the night of admission. The patient did well and was discharged 6 days after admission. He asked the manager of his favorite restaurant to reimburse him the $200 copayment required for hospitalization required under his Preferred Provider Plan; the request was immediately honored.

Esophageal perforation is an emergency because of its high mortality rate. The most frequent cause is iatrogenic with instrumentation from endoscopic procedures. Other causes include foreign body ingestion (as in this case), trauma, operative injury, and tumor.1 Aggressive surgical intervention vs. conservative nonsurgical management remains a controversial topic.2 Early‐contained perforations can be managed successfully by limiting oral intake and giving parenteral antibiotics.3, 4 Any signs of sepsis, deterioration in the patient's condition, or uncontained rupture warrants immediate surgical intervention.14

- ,,, et al.Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;77:1475–1483.

- ,,,.Esophageal perforation in adults.Ann Surg.2005;241(6):1016–1023.

- ,,.Esophageal perforation: emphasis of management.Ann Thorac Surg.1996;61:1447–1452

- ,,,.Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations.Ann Surg.1997;225(4):415–421.

A previously healthy 50‐year‐old man was eating a meal of rigatoni and shrimp at his favorite San Francisco restaurant when he suddenly developed severe pain in his throat followed a short time later by pleuritic chest pain localized to the anterior right chest. He completed his meal and then sought medical attention in the Emergency Department. He was in mild distress secondary to pain but his physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 15,300/mm3 with 86% neutrophils. A chest X‐ray, electrocardiogram, cardiac enzymes, and ventilation/perfusion scan were all normal. Because there was suspicion of an ingested foreign body, an abdominal radiograph was obtained which revealed a 2‐cm trapezoidal foreign body in the right lower quadrant (Figure 1; arrow). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed air in the mediastinum consistent with esophageal perforation (Figure 2). One day after admission a Hypaque esophagram showed trauma to the posterior cervical region of the esophagus, but no leak of contrast material into the mediastinum. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and nothing by mouth. Stools were screened and 48 hours after admission the patient (painlessly) passed a piece of glass with a very sharp point (Figure 3) correlating in size and shape to the foreign body seen on the previous abdominal radiograph. The glass had apparently fallen into the patient's restaurant meal the night of admission. The patient did well and was discharged 6 days after admission. He asked the manager of his favorite restaurant to reimburse him the $200 copayment required for hospitalization required under his Preferred Provider Plan; the request was immediately honored.

Esophageal perforation is an emergency because of its high mortality rate. The most frequent cause is iatrogenic with instrumentation from endoscopic procedures. Other causes include foreign body ingestion (as in this case), trauma, operative injury, and tumor.1 Aggressive surgical intervention vs. conservative nonsurgical management remains a controversial topic.2 Early‐contained perforations can be managed successfully by limiting oral intake and giving parenteral antibiotics.3, 4 Any signs of sepsis, deterioration in the patient's condition, or uncontained rupture warrants immediate surgical intervention.14

A previously healthy 50‐year‐old man was eating a meal of rigatoni and shrimp at his favorite San Francisco restaurant when he suddenly developed severe pain in his throat followed a short time later by pleuritic chest pain localized to the anterior right chest. He completed his meal and then sought medical attention in the Emergency Department. He was in mild distress secondary to pain but his physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 15,300/mm3 with 86% neutrophils. A chest X‐ray, electrocardiogram, cardiac enzymes, and ventilation/perfusion scan were all normal. Because there was suspicion of an ingested foreign body, an abdominal radiograph was obtained which revealed a 2‐cm trapezoidal foreign body in the right lower quadrant (Figure 1; arrow). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed air in the mediastinum consistent with esophageal perforation (Figure 2). One day after admission a Hypaque esophagram showed trauma to the posterior cervical region of the esophagus, but no leak of contrast material into the mediastinum. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and nothing by mouth. Stools were screened and 48 hours after admission the patient (painlessly) passed a piece of glass with a very sharp point (Figure 3) correlating in size and shape to the foreign body seen on the previous abdominal radiograph. The glass had apparently fallen into the patient's restaurant meal the night of admission. The patient did well and was discharged 6 days after admission. He asked the manager of his favorite restaurant to reimburse him the $200 copayment required for hospitalization required under his Preferred Provider Plan; the request was immediately honored.

Esophageal perforation is an emergency because of its high mortality rate. The most frequent cause is iatrogenic with instrumentation from endoscopic procedures. Other causes include foreign body ingestion (as in this case), trauma, operative injury, and tumor.1 Aggressive surgical intervention vs. conservative nonsurgical management remains a controversial topic.2 Early‐contained perforations can be managed successfully by limiting oral intake and giving parenteral antibiotics.3, 4 Any signs of sepsis, deterioration in the patient's condition, or uncontained rupture warrants immediate surgical intervention.14

- ,,, et al.Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;77:1475–1483.

- ,,,.Esophageal perforation in adults.Ann Surg.2005;241(6):1016–1023.

- ,,.Esophageal perforation: emphasis of management.Ann Thorac Surg.1996;61:1447–1452

- ,,,.Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations.Ann Surg.1997;225(4):415–421.

- ,,, et al.Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;77:1475–1483.

- ,,,.Esophageal perforation in adults.Ann Surg.2005;241(6):1016–1023.

- ,,.Esophageal perforation: emphasis of management.Ann Thorac Surg.1996;61:1447–1452

- ,,,.Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations.Ann Surg.1997;225(4):415–421.

TB with Pott's Disease and Psoas Abscess

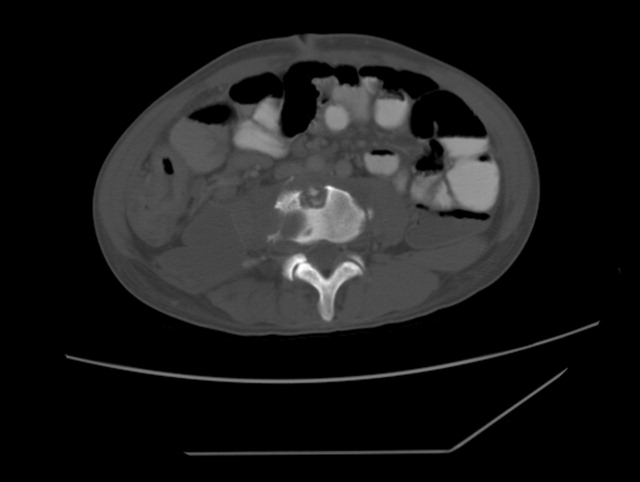

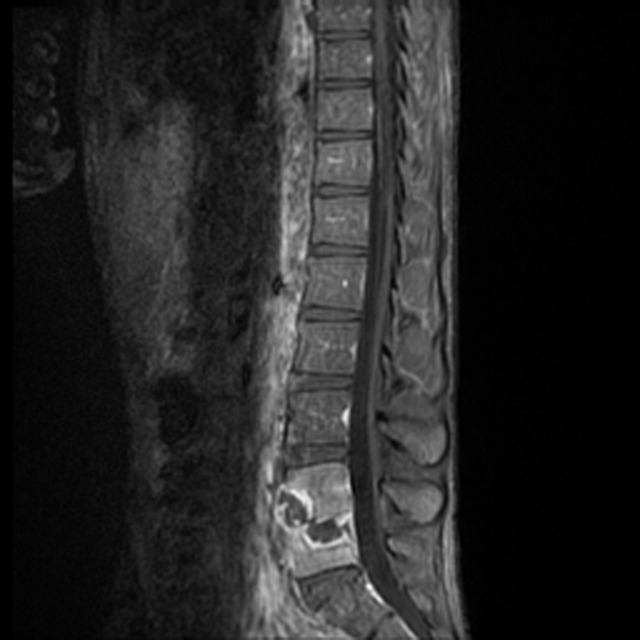

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

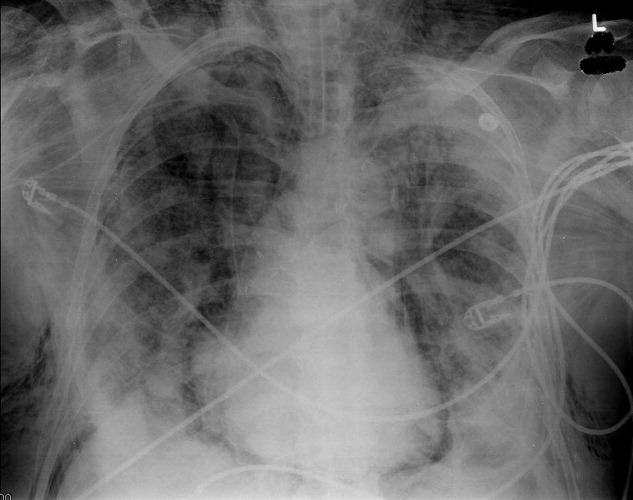

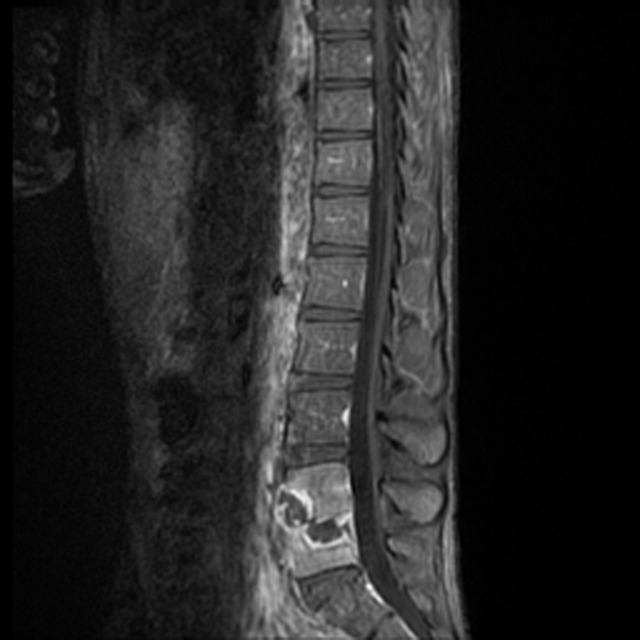

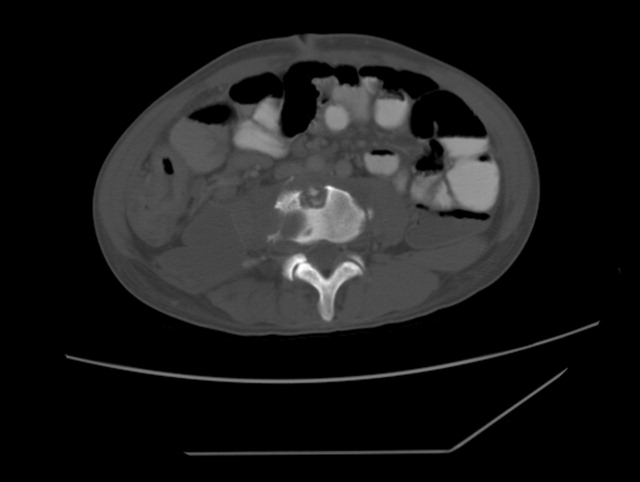

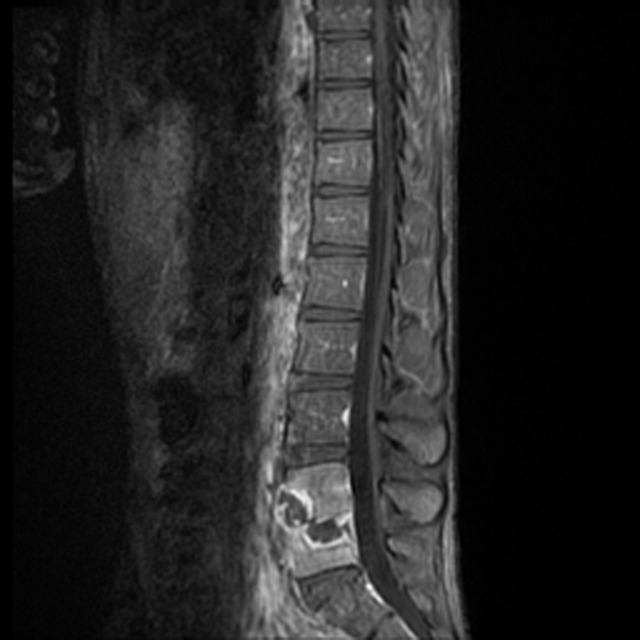

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

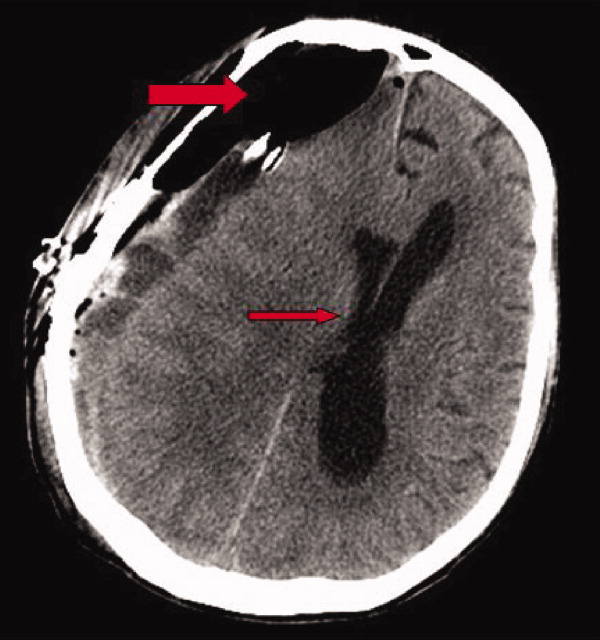

Tension Pneumocephalus as Complication of Hematoma Evacuation

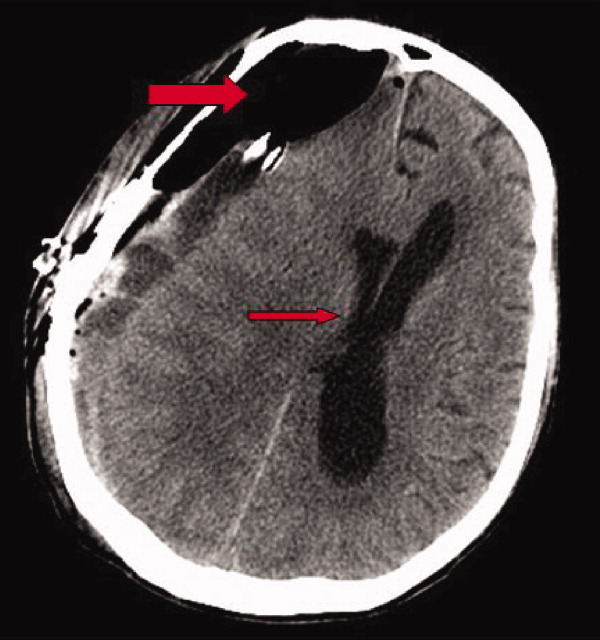

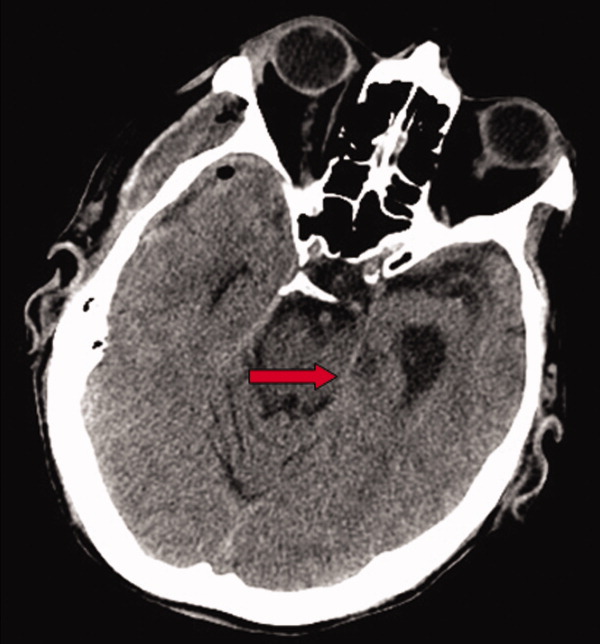

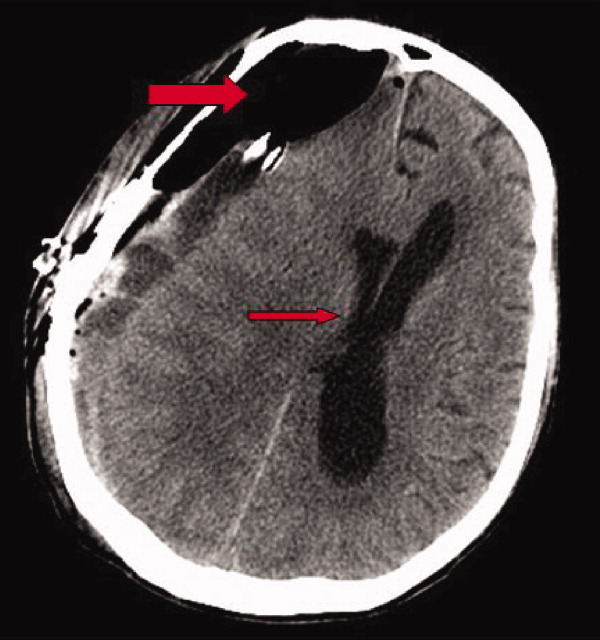

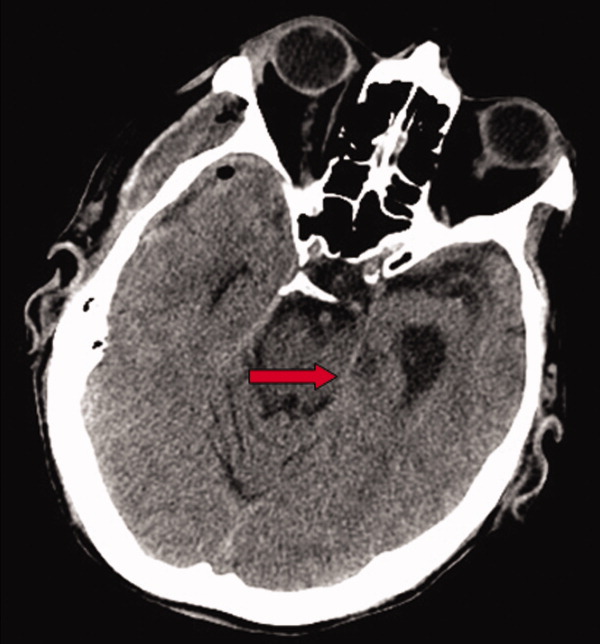

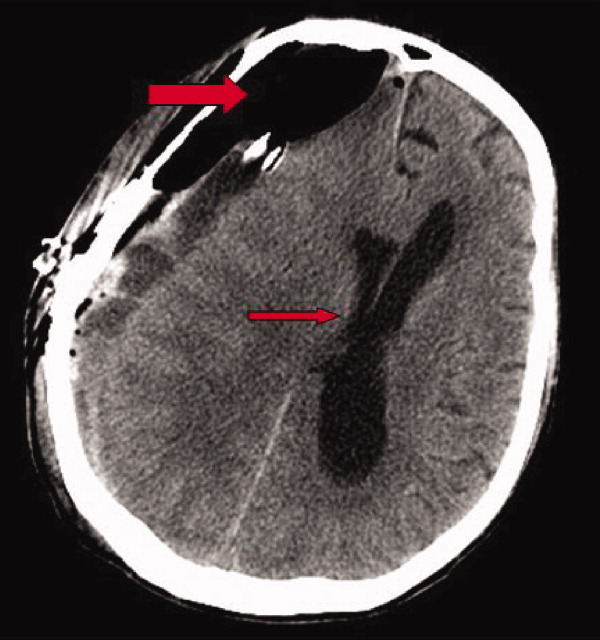

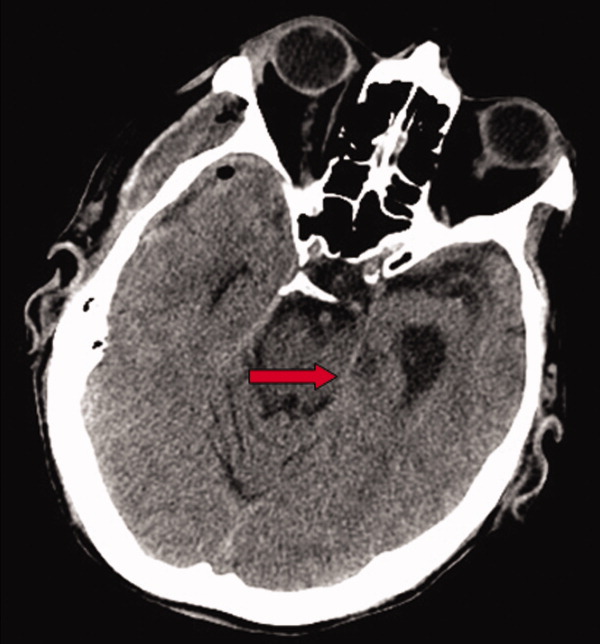

A 78‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital where he presented with declining mental status and a history of falls. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a chronic subdural hematoma with superimposed acute hemorrhage. The subdural hematoma was attributed to a fall at home approximately 5 weeks prior to admission. He was taken to the operating room for urgent craniotomy and hemorrhage evacuation and postoperatively comanaged by neurosurgery, hospitalists, and medicine residents. He tolerated the procedure and was noted to have marked improvement in mental status after the procedure. He was monitored overnight in our intensive care unit without intracranial pressure monitoring.

Early on postoperative day 1, he was awake, alert, following commands, and felt to be stable enough to be transferred to our transitional intensive care unit. However, later in the day he became progressively more confused. A follow‐up CT scan of the brain was ordered (Fig. 1) by the medicine team which revealed a large collection of air (wide arrow) and marked midline shift (thin arrow) consistent with tension pneumocephaly and subfalcine herniation (Fig. 2; arrow). Examination revealed that he was grossly obtunded with marked anisocoria, decerebrate posturing, and rigid tone. Neurosurgery was immediately contacted and recommended accessing 2 indwelling catheters left in the cerebrum as part of the normal postoperative course. Approximately 100 mL of serosanguinous fluid and air was aspirated with immediate improvement in his mental status and exam findings. Over the next few days, he remained clinically stable, and repeat CT scan showed slow resolution of the pneumocephalus and a decrease of his mass effect and midline shift. He was ultimately transferred to our skilled nursing facility for physical therapy and has done relatively well.

Pneumocephalus is a relatively common finding in many neurosurgical, intracranial procedures. However, tension pneumocephalus is a rare, life‐threatening form of pneumocephalus in which intracranial air causes mass effect and midline shift. In a review of 295 cases of pneumocephalus, 75% were caused by surgery, mostly intracranial and transsphenoidal, and head trauma. About 9% of cases resulted from infection with gas‐forming bacteria and rare causes include invasion of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma, frequent Valsalva maneuver, and air travel.1 Tension pneumocephalus occurs most commonly after the neurosurgical evacuation of a subdural hematoma. The prevalence of tension pneumocephalus following the evacuation of chronic subdural hematomas has been reported from 2.5% to 16%.2

There are 2 proposed mechanisms for the development of pneumocephalus; 1 proposes that air passes through a dural tear by a ball valve effect in which air can be forced into the intracranial cavity by a rapid increase in intrasinus pressure that occurs during sneezing, coughing, or straining. The air is then trapped intracranially. The second theory proposes that cerebrospinal fluid leakage permits air to enter the intracranial cavity because negative pressure is created as cerebrospinal fluid leaves the space.3 The conversion to tension physiology in either of these theories is less well understood.

- ,,,,.Pneumocephalus secondary to septic thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus: report of a case.J Formos Med Assoc.2001;100(2):142‐144.

- ,,, et al.Subdural tension pneumocephalus following surgery for chronic subdural hematoma.J Neurosurg.1988;68:58‐61.

- ,,,.Nontraumatic tension pneumocephalus—a differential diagnosis of headache in the ED.Am J Emerg Med.2005, Vol.23, pp235‐236.

A 78‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital where he presented with declining mental status and a history of falls. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a chronic subdural hematoma with superimposed acute hemorrhage. The subdural hematoma was attributed to a fall at home approximately 5 weeks prior to admission. He was taken to the operating room for urgent craniotomy and hemorrhage evacuation and postoperatively comanaged by neurosurgery, hospitalists, and medicine residents. He tolerated the procedure and was noted to have marked improvement in mental status after the procedure. He was monitored overnight in our intensive care unit without intracranial pressure monitoring.

Early on postoperative day 1, he was awake, alert, following commands, and felt to be stable enough to be transferred to our transitional intensive care unit. However, later in the day he became progressively more confused. A follow‐up CT scan of the brain was ordered (Fig. 1) by the medicine team which revealed a large collection of air (wide arrow) and marked midline shift (thin arrow) consistent with tension pneumocephaly and subfalcine herniation (Fig. 2; arrow). Examination revealed that he was grossly obtunded with marked anisocoria, decerebrate posturing, and rigid tone. Neurosurgery was immediately contacted and recommended accessing 2 indwelling catheters left in the cerebrum as part of the normal postoperative course. Approximately 100 mL of serosanguinous fluid and air was aspirated with immediate improvement in his mental status and exam findings. Over the next few days, he remained clinically stable, and repeat CT scan showed slow resolution of the pneumocephalus and a decrease of his mass effect and midline shift. He was ultimately transferred to our skilled nursing facility for physical therapy and has done relatively well.

Pneumocephalus is a relatively common finding in many neurosurgical, intracranial procedures. However, tension pneumocephalus is a rare, life‐threatening form of pneumocephalus in which intracranial air causes mass effect and midline shift. In a review of 295 cases of pneumocephalus, 75% were caused by surgery, mostly intracranial and transsphenoidal, and head trauma. About 9% of cases resulted from infection with gas‐forming bacteria and rare causes include invasion of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma, frequent Valsalva maneuver, and air travel.1 Tension pneumocephalus occurs most commonly after the neurosurgical evacuation of a subdural hematoma. The prevalence of tension pneumocephalus following the evacuation of chronic subdural hematomas has been reported from 2.5% to 16%.2

There are 2 proposed mechanisms for the development of pneumocephalus; 1 proposes that air passes through a dural tear by a ball valve effect in which air can be forced into the intracranial cavity by a rapid increase in intrasinus pressure that occurs during sneezing, coughing, or straining. The air is then trapped intracranially. The second theory proposes that cerebrospinal fluid leakage permits air to enter the intracranial cavity because negative pressure is created as cerebrospinal fluid leaves the space.3 The conversion to tension physiology in either of these theories is less well understood.

A 78‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital where he presented with declining mental status and a history of falls. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a chronic subdural hematoma with superimposed acute hemorrhage. The subdural hematoma was attributed to a fall at home approximately 5 weeks prior to admission. He was taken to the operating room for urgent craniotomy and hemorrhage evacuation and postoperatively comanaged by neurosurgery, hospitalists, and medicine residents. He tolerated the procedure and was noted to have marked improvement in mental status after the procedure. He was monitored overnight in our intensive care unit without intracranial pressure monitoring.

Early on postoperative day 1, he was awake, alert, following commands, and felt to be stable enough to be transferred to our transitional intensive care unit. However, later in the day he became progressively more confused. A follow‐up CT scan of the brain was ordered (Fig. 1) by the medicine team which revealed a large collection of air (wide arrow) and marked midline shift (thin arrow) consistent with tension pneumocephaly and subfalcine herniation (Fig. 2; arrow). Examination revealed that he was grossly obtunded with marked anisocoria, decerebrate posturing, and rigid tone. Neurosurgery was immediately contacted and recommended accessing 2 indwelling catheters left in the cerebrum as part of the normal postoperative course. Approximately 100 mL of serosanguinous fluid and air was aspirated with immediate improvement in his mental status and exam findings. Over the next few days, he remained clinically stable, and repeat CT scan showed slow resolution of the pneumocephalus and a decrease of his mass effect and midline shift. He was ultimately transferred to our skilled nursing facility for physical therapy and has done relatively well.

Pneumocephalus is a relatively common finding in many neurosurgical, intracranial procedures. However, tension pneumocephalus is a rare, life‐threatening form of pneumocephalus in which intracranial air causes mass effect and midline shift. In a review of 295 cases of pneumocephalus, 75% were caused by surgery, mostly intracranial and transsphenoidal, and head trauma. About 9% of cases resulted from infection with gas‐forming bacteria and rare causes include invasion of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma, frequent Valsalva maneuver, and air travel.1 Tension pneumocephalus occurs most commonly after the neurosurgical evacuation of a subdural hematoma. The prevalence of tension pneumocephalus following the evacuation of chronic subdural hematomas has been reported from 2.5% to 16%.2

There are 2 proposed mechanisms for the development of pneumocephalus; 1 proposes that air passes through a dural tear by a ball valve effect in which air can be forced into the intracranial cavity by a rapid increase in intrasinus pressure that occurs during sneezing, coughing, or straining. The air is then trapped intracranially. The second theory proposes that cerebrospinal fluid leakage permits air to enter the intracranial cavity because negative pressure is created as cerebrospinal fluid leaves the space.3 The conversion to tension physiology in either of these theories is less well understood.

- ,,,,.Pneumocephalus secondary to septic thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus: report of a case.J Formos Med Assoc.2001;100(2):142‐144.

- ,,, et al.Subdural tension pneumocephalus following surgery for chronic subdural hematoma.J Neurosurg.1988;68:58‐61.

- ,,,.Nontraumatic tension pneumocephalus—a differential diagnosis of headache in the ED.Am J Emerg Med.2005, Vol.23, pp235‐236.

- ,,,,.Pneumocephalus secondary to septic thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus: report of a case.J Formos Med Assoc.2001;100(2):142‐144.

- ,,, et al.Subdural tension pneumocephalus following surgery for chronic subdural hematoma.J Neurosurg.1988;68:58‐61.

- ,,,.Nontraumatic tension pneumocephalus—a differential diagnosis of headache in the ED.Am J Emerg Med.2005, Vol.23, pp235‐236.

Symmetrical drug‐related intertriginous and flexural exanthema after coronary artery angiography

A 57‐year‐old woman developed a pruritic rash 6 hours after undergoing coronary angiography. On exam, symmetrical, eczematous plaques were noted in her bilateral groin (Figure 1), buttocks, axillae (Figure 2), and the intertriginous folds of her breasts. No palmar, plantar, or mucosal lesions were noted and laboratory tests were normal. This patient presents with symmetrical drug‐related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE) secondary to iodine‐based contrast dye. It is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction most often reported to nickel, mercury, and systemic antibiotics, although previous sensitization is often unknown. Also called baboon syndrome because its distribution mimics the pink bottom of a baboon, SDRIFE appears hours to days after exposure to the offending agent. The unusual distribution may be explained by high concentrations of the allergen in sweat. Resolution is typical with discontinuation of the offending drug, although antihistamines, topical steroids, and possibly oral steroids may be useful adjuncts.

A 57‐year‐old woman developed a pruritic rash 6 hours after undergoing coronary angiography. On exam, symmetrical, eczematous plaques were noted in her bilateral groin (Figure 1), buttocks, axillae (Figure 2), and the intertriginous folds of her breasts. No palmar, plantar, or mucosal lesions were noted and laboratory tests were normal. This patient presents with symmetrical drug‐related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE) secondary to iodine‐based contrast dye. It is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction most often reported to nickel, mercury, and systemic antibiotics, although previous sensitization is often unknown. Also called baboon syndrome because its distribution mimics the pink bottom of a baboon, SDRIFE appears hours to days after exposure to the offending agent. The unusual distribution may be explained by high concentrations of the allergen in sweat. Resolution is typical with discontinuation of the offending drug, although antihistamines, topical steroids, and possibly oral steroids may be useful adjuncts.

A 57‐year‐old woman developed a pruritic rash 6 hours after undergoing coronary angiography. On exam, symmetrical, eczematous plaques were noted in her bilateral groin (Figure 1), buttocks, axillae (Figure 2), and the intertriginous folds of her breasts. No palmar, plantar, or mucosal lesions were noted and laboratory tests were normal. This patient presents with symmetrical drug‐related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE) secondary to iodine‐based contrast dye. It is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction most often reported to nickel, mercury, and systemic antibiotics, although previous sensitization is often unknown. Also called baboon syndrome because its distribution mimics the pink bottom of a baboon, SDRIFE appears hours to days after exposure to the offending agent. The unusual distribution may be explained by high concentrations of the allergen in sweat. Resolution is typical with discontinuation of the offending drug, although antihistamines, topical steroids, and possibly oral steroids may be useful adjuncts.