User login

The skill set of the ‘pluripotent’ hospitalist

Editor’s note: National Hospitalist Day occurs the first Thursday in March annually, and serves to celebrate the fastest growing specialty in modern medicine and hospitalists’ enduring contributions to the evolving health care landscape. On National Hospitalist Day in 2021, SHM convened a virtual roundtable with a diverse group of hospitalists to discuss skill set, wellness, and other key issues for hospitalists. To listen to the entire roundtable discussion, visit this Explore The Space podcast episode.

A hospitalist isn’t just a physician who happens to work in a hospital. They are medical professionals with a robust skill set that they use both inside and outside the hospital setting. But what skill sets do hospitalists need to become successful in their careers? And what skill sets does a “pluripotent” hospitalist need in their armamentarium?

These were the issues discussed by participants of a virtual roundtable discussion on National Hospitalist Day – March 4, 2021 – as part of a joint effort of the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Explore the Space podcast.

Maylyn S. Martinez, MD, clinician-researcher and clinical associate at the University of Chicago, sees her hospitalist and research skill sets as two “buckets” of skills she can sort through, with diagnostic, knowledge-based care coordination, and interpersonal skills as lanes where she can focus and improve. “I’m always trying to work in, and sharpen, and find ways to get better at something in each of those every day,” she said.

For Anika Kumar, MD, FHM, pediatric editor of the Hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, much of her work is focused on problem solving. “I approach that as: ‘How do I come up with my differential diagnosis, and how do I diagnose the patient?’ I think that the lanes are a little bit different, but there is some overlap.”

Adaptability is another important part of the skill set for the hospitalist, Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd, associate professor in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, said during the discussion. “I think we all really value teamwork, and we take on the role of being the coordinator and making sure things are getting done in a seamless and thoughtful manner. Communicating with families, communicating with our research team, communicating with primary care physicians. I think that is something we’re very used to doing, and I think we do it well. I think we don’t shy away from difficult conversations with consultants. And I think that’s what makes being a hospitalist so amazing.”

Achieving wellness as a hospitalist

Another topic discussed during the roundtable was “comprehensive care for the hospitalist” and how they can achieve a sense of wellness for themselves. Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, clinician-educator and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said long-term satisfaction in one’s career is less about compensation and more about autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

“Autonomy is shrinking a little bit in health care. But if we connect to our purpose – ‘what are we doing here and how do we connect?’ – it’s either learning about patients and their stories, being with a team of people that you work with, that really builds that purpose,” he said.

Regarding mastery, there’s “tremendous joy if you’re in an environment where people value your mastery, whether it is working in a team or communicating or diagnosing or doing a procedure. If you think of setting up the work environment and those things are in place, I think a lot of wellness can actually happen at work, even though another component, of course, is balancing your life outside of work,” Dr. Dhaliwal said.

This may seem out of reach during COVID-19, but wellness is still achievable during the pandemic, Dr. Martinez said. Her time is spent 75% as a researcher and 25% as a clinician, which is her ideal balance. “I enjoy doing my research, doing my own statistics and writing grants and just learning about this problem that I’ve developed an interest in,” she said. “I just think that’s an important piece for people to focus on as far as health care for the hospitalist, is that there’s no no-one-size-fits-all, that’s for sure.”

Dr. Kumar noted that her clinical time gives her energy for nonclinical work. “I love my clinical time. It’s one of my favorite things that I do,” she said. Although she is tired at the end of the week, “I feel like I am not only giving back to my patients and my team, but I’m also giving back to myself and reminding myself why it is I do what I do every day,” she said.

Wellness for Dr. Unaka meant remembering what drew her to medicine. “It was definitely the opportunity to build strong relationships with patients and families,” she said. While these encounters can sometimes be heavy and stay with a hospitalist, “the fact that we’re in it with them is something that gives a lot of us purpose. I think that when I reflect on all of those things, I’m so happy that I’m in the role that I am.”

Unique skills during COVID-19

Mark Shapiro, MD, hospitalist and host of the roundtable and the Explore the Space podcast, also asked the panelists what skills they unexpectedly leveraged during the pandemic. Communication – with colleagues and with the community they serve – was a universal answer among the panelists.

“I learned – really from seeing some of our senior leaders here do it so well – the importance of being visible, particularly at a time when people were not together and more isolated,” Dr. Unaka said. “I think being able to be visible when you can, in order to deliver really complicated or tough news or communicate about uncertainty, for instance. Being here for our residents – many of our interns moved here sight unseen. I think they needed to feel like they had some sense of normalcy and a sense of community. I really learned how important it was to be visible, and available, and how important the little things mattered.”

Dr. Martinez said that worrying about her patients with COVID-19 in the hospital and the uncertainty around the disease kept her up at night. “I think we always have a hard time leaving work at work and getting a good night’s sleep. I just could not let go of worrying about these patients and having terrible insomnia, trying to leave work at work and I couldn’t – even after they were discharged.”

Dr. Shapiro said the skill he most needed to work on during the pandemic was his courage. “I remember the first time I took care of COVID patients. I was scared. I have no problems saying that out loud. That was a scary experience.”

The demeanor of the nurses on his unit, who had already seen patients with COVID-19, helped ground him during those moments and gave him the courage to move forward. “They’d already been doing it and they were the same. Same affect, same jokes, same everything,” he said. “That actually really helped, and I’ve leaned on that every time I’ve been back on our COVID service.”

Importance of mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic has also shined a light on the importance of mental health. “I think it is important to acknowledge that as hospitalists who have been out on the bleeding edge for a year, mental health is critically important, and we know that we face shortages in that space for the public at large and also for our profession,” Dr. Shapiro said.

When asked about what mental health and self-care looks like for her, Dr. Kumar referenced the need for exercise, meditation, and yoga. “My mental health was better knowing that the people closest to me – whether they be colleagues or friends or family – their mental health was also in a good place and they were also in a good place. And that helped to build me up,” she said.

Dr. Unaka called attention to the stigma around mental health, particularly among physicians, and the lack of resources to address the issue. “It’s a real problem,” she said. “I think it’s at a point where we as a profession need to advocate on behalf of each other and on behalf of our trainees. And honestly, I think we need to view mental health as just ‘health’ and stop separating it out in order for us to move to a place where people feel like they can access what they need without feeling shame about it.”

Editor’s note: National Hospitalist Day occurs the first Thursday in March annually, and serves to celebrate the fastest growing specialty in modern medicine and hospitalists’ enduring contributions to the evolving health care landscape. On National Hospitalist Day in 2021, SHM convened a virtual roundtable with a diverse group of hospitalists to discuss skill set, wellness, and other key issues for hospitalists. To listen to the entire roundtable discussion, visit this Explore The Space podcast episode.

A hospitalist isn’t just a physician who happens to work in a hospital. They are medical professionals with a robust skill set that they use both inside and outside the hospital setting. But what skill sets do hospitalists need to become successful in their careers? And what skill sets does a “pluripotent” hospitalist need in their armamentarium?

These were the issues discussed by participants of a virtual roundtable discussion on National Hospitalist Day – March 4, 2021 – as part of a joint effort of the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Explore the Space podcast.

Maylyn S. Martinez, MD, clinician-researcher and clinical associate at the University of Chicago, sees her hospitalist and research skill sets as two “buckets” of skills she can sort through, with diagnostic, knowledge-based care coordination, and interpersonal skills as lanes where she can focus and improve. “I’m always trying to work in, and sharpen, and find ways to get better at something in each of those every day,” she said.

For Anika Kumar, MD, FHM, pediatric editor of the Hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, much of her work is focused on problem solving. “I approach that as: ‘How do I come up with my differential diagnosis, and how do I diagnose the patient?’ I think that the lanes are a little bit different, but there is some overlap.”

Adaptability is another important part of the skill set for the hospitalist, Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd, associate professor in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, said during the discussion. “I think we all really value teamwork, and we take on the role of being the coordinator and making sure things are getting done in a seamless and thoughtful manner. Communicating with families, communicating with our research team, communicating with primary care physicians. I think that is something we’re very used to doing, and I think we do it well. I think we don’t shy away from difficult conversations with consultants. And I think that’s what makes being a hospitalist so amazing.”

Achieving wellness as a hospitalist

Another topic discussed during the roundtable was “comprehensive care for the hospitalist” and how they can achieve a sense of wellness for themselves. Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, clinician-educator and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said long-term satisfaction in one’s career is less about compensation and more about autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

“Autonomy is shrinking a little bit in health care. But if we connect to our purpose – ‘what are we doing here and how do we connect?’ – it’s either learning about patients and their stories, being with a team of people that you work with, that really builds that purpose,” he said.

Regarding mastery, there’s “tremendous joy if you’re in an environment where people value your mastery, whether it is working in a team or communicating or diagnosing or doing a procedure. If you think of setting up the work environment and those things are in place, I think a lot of wellness can actually happen at work, even though another component, of course, is balancing your life outside of work,” Dr. Dhaliwal said.

This may seem out of reach during COVID-19, but wellness is still achievable during the pandemic, Dr. Martinez said. Her time is spent 75% as a researcher and 25% as a clinician, which is her ideal balance. “I enjoy doing my research, doing my own statistics and writing grants and just learning about this problem that I’ve developed an interest in,” she said. “I just think that’s an important piece for people to focus on as far as health care for the hospitalist, is that there’s no no-one-size-fits-all, that’s for sure.”

Dr. Kumar noted that her clinical time gives her energy for nonclinical work. “I love my clinical time. It’s one of my favorite things that I do,” she said. Although she is tired at the end of the week, “I feel like I am not only giving back to my patients and my team, but I’m also giving back to myself and reminding myself why it is I do what I do every day,” she said.

Wellness for Dr. Unaka meant remembering what drew her to medicine. “It was definitely the opportunity to build strong relationships with patients and families,” she said. While these encounters can sometimes be heavy and stay with a hospitalist, “the fact that we’re in it with them is something that gives a lot of us purpose. I think that when I reflect on all of those things, I’m so happy that I’m in the role that I am.”

Unique skills during COVID-19

Mark Shapiro, MD, hospitalist and host of the roundtable and the Explore the Space podcast, also asked the panelists what skills they unexpectedly leveraged during the pandemic. Communication – with colleagues and with the community they serve – was a universal answer among the panelists.

“I learned – really from seeing some of our senior leaders here do it so well – the importance of being visible, particularly at a time when people were not together and more isolated,” Dr. Unaka said. “I think being able to be visible when you can, in order to deliver really complicated or tough news or communicate about uncertainty, for instance. Being here for our residents – many of our interns moved here sight unseen. I think they needed to feel like they had some sense of normalcy and a sense of community. I really learned how important it was to be visible, and available, and how important the little things mattered.”

Dr. Martinez said that worrying about her patients with COVID-19 in the hospital and the uncertainty around the disease kept her up at night. “I think we always have a hard time leaving work at work and getting a good night’s sleep. I just could not let go of worrying about these patients and having terrible insomnia, trying to leave work at work and I couldn’t – even after they were discharged.”

Dr. Shapiro said the skill he most needed to work on during the pandemic was his courage. “I remember the first time I took care of COVID patients. I was scared. I have no problems saying that out loud. That was a scary experience.”

The demeanor of the nurses on his unit, who had already seen patients with COVID-19, helped ground him during those moments and gave him the courage to move forward. “They’d already been doing it and they were the same. Same affect, same jokes, same everything,” he said. “That actually really helped, and I’ve leaned on that every time I’ve been back on our COVID service.”

Importance of mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic has also shined a light on the importance of mental health. “I think it is important to acknowledge that as hospitalists who have been out on the bleeding edge for a year, mental health is critically important, and we know that we face shortages in that space for the public at large and also for our profession,” Dr. Shapiro said.

When asked about what mental health and self-care looks like for her, Dr. Kumar referenced the need for exercise, meditation, and yoga. “My mental health was better knowing that the people closest to me – whether they be colleagues or friends or family – their mental health was also in a good place and they were also in a good place. And that helped to build me up,” she said.

Dr. Unaka called attention to the stigma around mental health, particularly among physicians, and the lack of resources to address the issue. “It’s a real problem,” she said. “I think it’s at a point where we as a profession need to advocate on behalf of each other and on behalf of our trainees. And honestly, I think we need to view mental health as just ‘health’ and stop separating it out in order for us to move to a place where people feel like they can access what they need without feeling shame about it.”

Editor’s note: National Hospitalist Day occurs the first Thursday in March annually, and serves to celebrate the fastest growing specialty in modern medicine and hospitalists’ enduring contributions to the evolving health care landscape. On National Hospitalist Day in 2021, SHM convened a virtual roundtable with a diverse group of hospitalists to discuss skill set, wellness, and other key issues for hospitalists. To listen to the entire roundtable discussion, visit this Explore The Space podcast episode.

A hospitalist isn’t just a physician who happens to work in a hospital. They are medical professionals with a robust skill set that they use both inside and outside the hospital setting. But what skill sets do hospitalists need to become successful in their careers? And what skill sets does a “pluripotent” hospitalist need in their armamentarium?

These were the issues discussed by participants of a virtual roundtable discussion on National Hospitalist Day – March 4, 2021 – as part of a joint effort of the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Explore the Space podcast.

Maylyn S. Martinez, MD, clinician-researcher and clinical associate at the University of Chicago, sees her hospitalist and research skill sets as two “buckets” of skills she can sort through, with diagnostic, knowledge-based care coordination, and interpersonal skills as lanes where she can focus and improve. “I’m always trying to work in, and sharpen, and find ways to get better at something in each of those every day,” she said.

For Anika Kumar, MD, FHM, pediatric editor of the Hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, much of her work is focused on problem solving. “I approach that as: ‘How do I come up with my differential diagnosis, and how do I diagnose the patient?’ I think that the lanes are a little bit different, but there is some overlap.”

Adaptability is another important part of the skill set for the hospitalist, Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd, associate professor in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, said during the discussion. “I think we all really value teamwork, and we take on the role of being the coordinator and making sure things are getting done in a seamless and thoughtful manner. Communicating with families, communicating with our research team, communicating with primary care physicians. I think that is something we’re very used to doing, and I think we do it well. I think we don’t shy away from difficult conversations with consultants. And I think that’s what makes being a hospitalist so amazing.”

Achieving wellness as a hospitalist

Another topic discussed during the roundtable was “comprehensive care for the hospitalist” and how they can achieve a sense of wellness for themselves. Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, clinician-educator and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said long-term satisfaction in one’s career is less about compensation and more about autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

“Autonomy is shrinking a little bit in health care. But if we connect to our purpose – ‘what are we doing here and how do we connect?’ – it’s either learning about patients and their stories, being with a team of people that you work with, that really builds that purpose,” he said.

Regarding mastery, there’s “tremendous joy if you’re in an environment where people value your mastery, whether it is working in a team or communicating or diagnosing or doing a procedure. If you think of setting up the work environment and those things are in place, I think a lot of wellness can actually happen at work, even though another component, of course, is balancing your life outside of work,” Dr. Dhaliwal said.

This may seem out of reach during COVID-19, but wellness is still achievable during the pandemic, Dr. Martinez said. Her time is spent 75% as a researcher and 25% as a clinician, which is her ideal balance. “I enjoy doing my research, doing my own statistics and writing grants and just learning about this problem that I’ve developed an interest in,” she said. “I just think that’s an important piece for people to focus on as far as health care for the hospitalist, is that there’s no no-one-size-fits-all, that’s for sure.”

Dr. Kumar noted that her clinical time gives her energy for nonclinical work. “I love my clinical time. It’s one of my favorite things that I do,” she said. Although she is tired at the end of the week, “I feel like I am not only giving back to my patients and my team, but I’m also giving back to myself and reminding myself why it is I do what I do every day,” she said.

Wellness for Dr. Unaka meant remembering what drew her to medicine. “It was definitely the opportunity to build strong relationships with patients and families,” she said. While these encounters can sometimes be heavy and stay with a hospitalist, “the fact that we’re in it with them is something that gives a lot of us purpose. I think that when I reflect on all of those things, I’m so happy that I’m in the role that I am.”

Unique skills during COVID-19

Mark Shapiro, MD, hospitalist and host of the roundtable and the Explore the Space podcast, also asked the panelists what skills they unexpectedly leveraged during the pandemic. Communication – with colleagues and with the community they serve – was a universal answer among the panelists.

“I learned – really from seeing some of our senior leaders here do it so well – the importance of being visible, particularly at a time when people were not together and more isolated,” Dr. Unaka said. “I think being able to be visible when you can, in order to deliver really complicated or tough news or communicate about uncertainty, for instance. Being here for our residents – many of our interns moved here sight unseen. I think they needed to feel like they had some sense of normalcy and a sense of community. I really learned how important it was to be visible, and available, and how important the little things mattered.”

Dr. Martinez said that worrying about her patients with COVID-19 in the hospital and the uncertainty around the disease kept her up at night. “I think we always have a hard time leaving work at work and getting a good night’s sleep. I just could not let go of worrying about these patients and having terrible insomnia, trying to leave work at work and I couldn’t – even after they were discharged.”

Dr. Shapiro said the skill he most needed to work on during the pandemic was his courage. “I remember the first time I took care of COVID patients. I was scared. I have no problems saying that out loud. That was a scary experience.”

The demeanor of the nurses on his unit, who had already seen patients with COVID-19, helped ground him during those moments and gave him the courage to move forward. “They’d already been doing it and they were the same. Same affect, same jokes, same everything,” he said. “That actually really helped, and I’ve leaned on that every time I’ve been back on our COVID service.”

Importance of mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic has also shined a light on the importance of mental health. “I think it is important to acknowledge that as hospitalists who have been out on the bleeding edge for a year, mental health is critically important, and we know that we face shortages in that space for the public at large and also for our profession,” Dr. Shapiro said.

When asked about what mental health and self-care looks like for her, Dr. Kumar referenced the need for exercise, meditation, and yoga. “My mental health was better knowing that the people closest to me – whether they be colleagues or friends or family – their mental health was also in a good place and they were also in a good place. And that helped to build me up,” she said.

Dr. Unaka called attention to the stigma around mental health, particularly among physicians, and the lack of resources to address the issue. “It’s a real problem,” she said. “I think it’s at a point where we as a profession need to advocate on behalf of each other and on behalf of our trainees. And honestly, I think we need to view mental health as just ‘health’ and stop separating it out in order for us to move to a place where people feel like they can access what they need without feeling shame about it.”

Virtual is the new real

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the transformation of Internet-based, remotely accessible innovative technologies. Internet-based customer service delivery technology was rapidly adopted and utilized by several services industries, but health care systems in most of the countries across the world faced unique challenges in adopting the technology for the delivery of health care services. The health care ecosystem of the United States was not immune to such challenges, and several significant barriers surfaced while the pandemic was underway.

Complexly structured, fragmented, unprepared, and overly burnt-out health systems in the United States arguably have fallen short of maximizing the value of telehealth in delivering safe, easily accessible, comprehensive, and cost-effective health care services. In this essay, we examine the reasons for such a suboptimal performance and discuss a few important strategies that may be useful in maximizing the value of telehealth value in several, appropriate health care services.

Hospitals and telehealth

Are hospitalists preparing ourselves “not to see” patients in a hospital-based health care delivery setting? If you have not yet started yet, now may be the right time! Yes, a certain percentage of doctor-patient encounters in hospital settings will remain virtual forever.

A well-established telehealth infrastructure is rarely found in most U.S. hospitals, although the COVID-19 pandemic has unexpectedly boosted the rapid growth of telehealth in the country.1 Public health emergency declarations in the United States in the face of the COVID-19 crisis have facilitated two important initiatives to restore health care delivery amidst formal and informal lockdowns that brought states to a grinding halt. These extend from expansion of virtual services, including telehealth, virtual check-ins, and e-visits, to the decision by the Department of Health & Human Services Office of Civil Rights to exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for the use of relatively inexpensive, non–public-facing mobile and other audiovisual technology tools.2

Hospital-based care in the United States taps nearly 33% of national health expenditure. An additional 30% of national health expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities is indirectly influenced by care delivered at health care facilities.3 Studies show that about 20% of ED visits could potentially be avoided via virtual urgent care offerings.4 A rapidly changing health care ecosystem is proving formidable for most hospital systems, and a test for their resilience and agility. Not just the implementation of telehealth is challenging, but getting it right is the key success factor.

Hospital-based telehealth

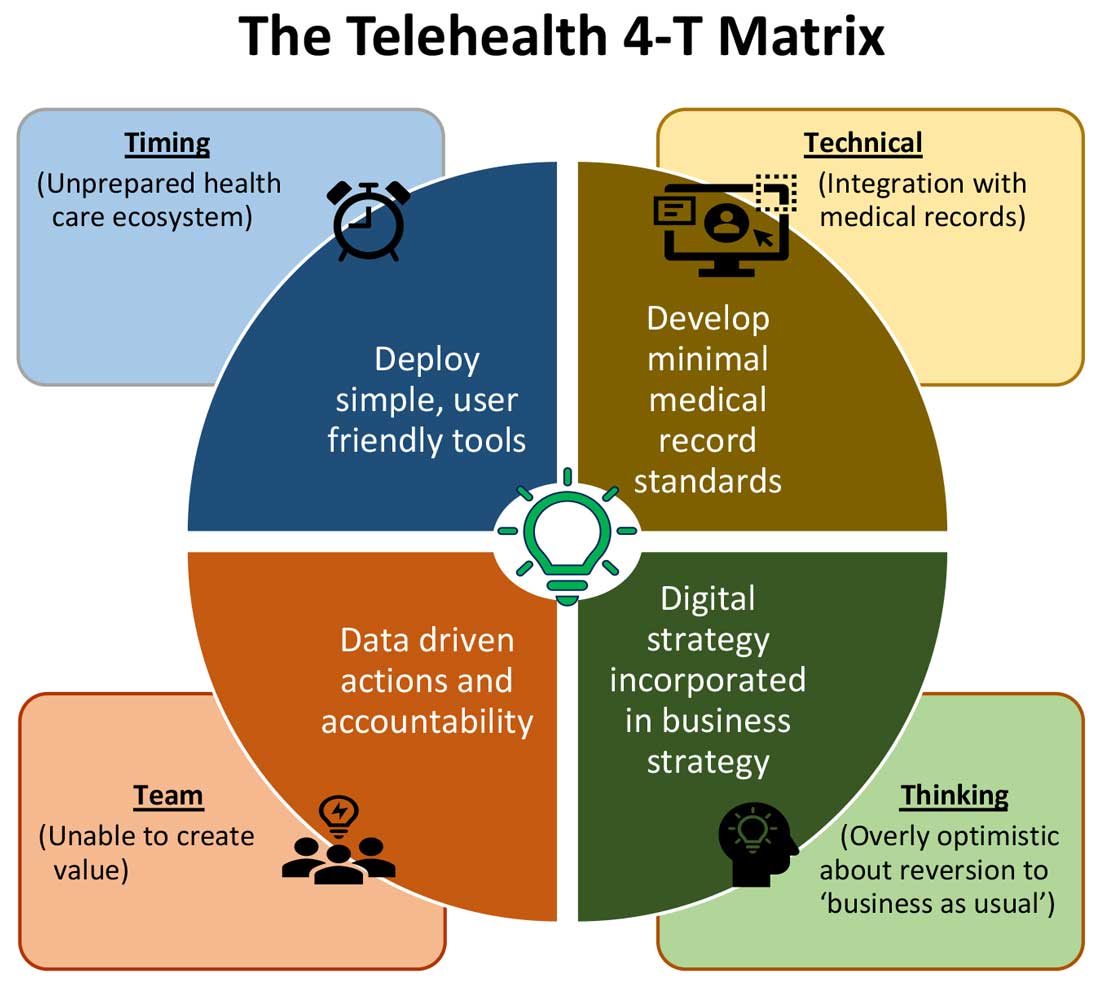

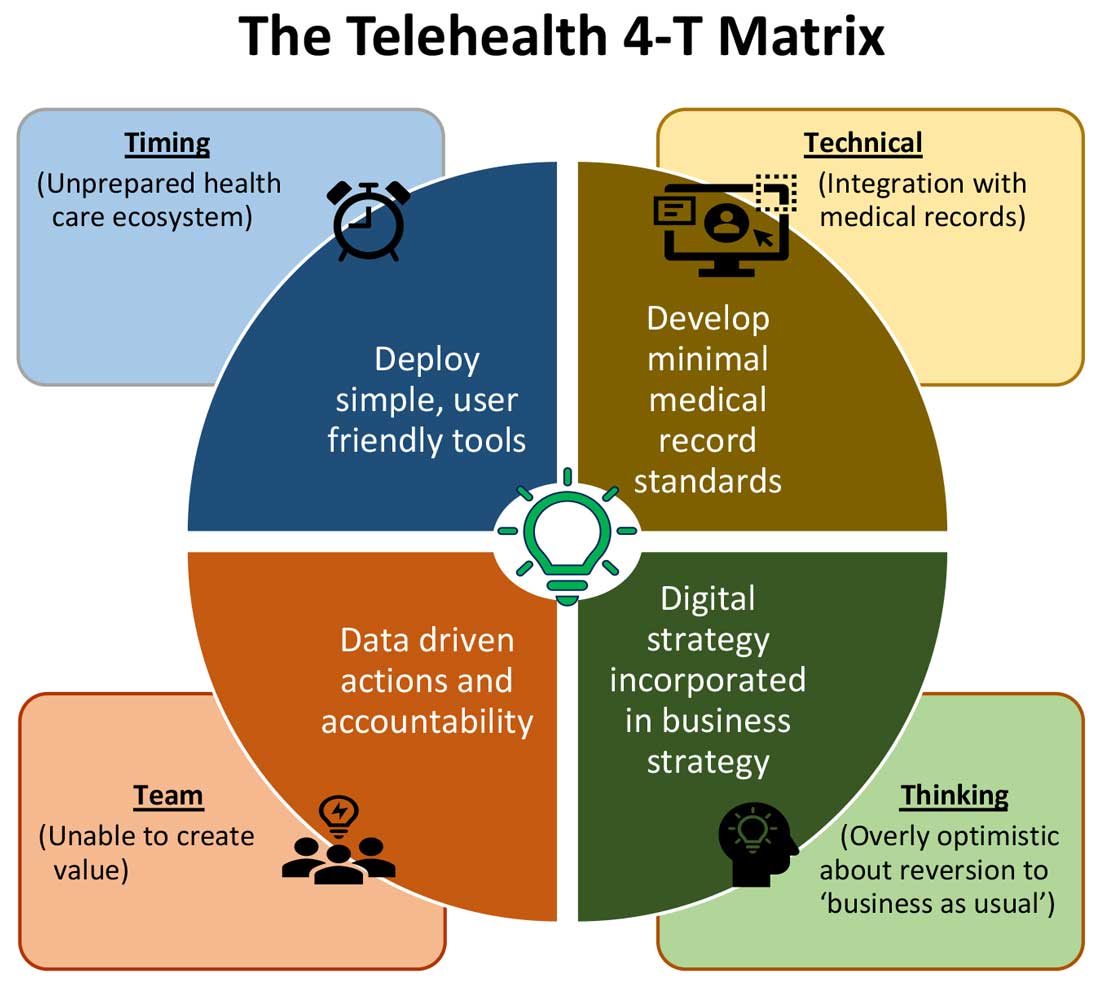

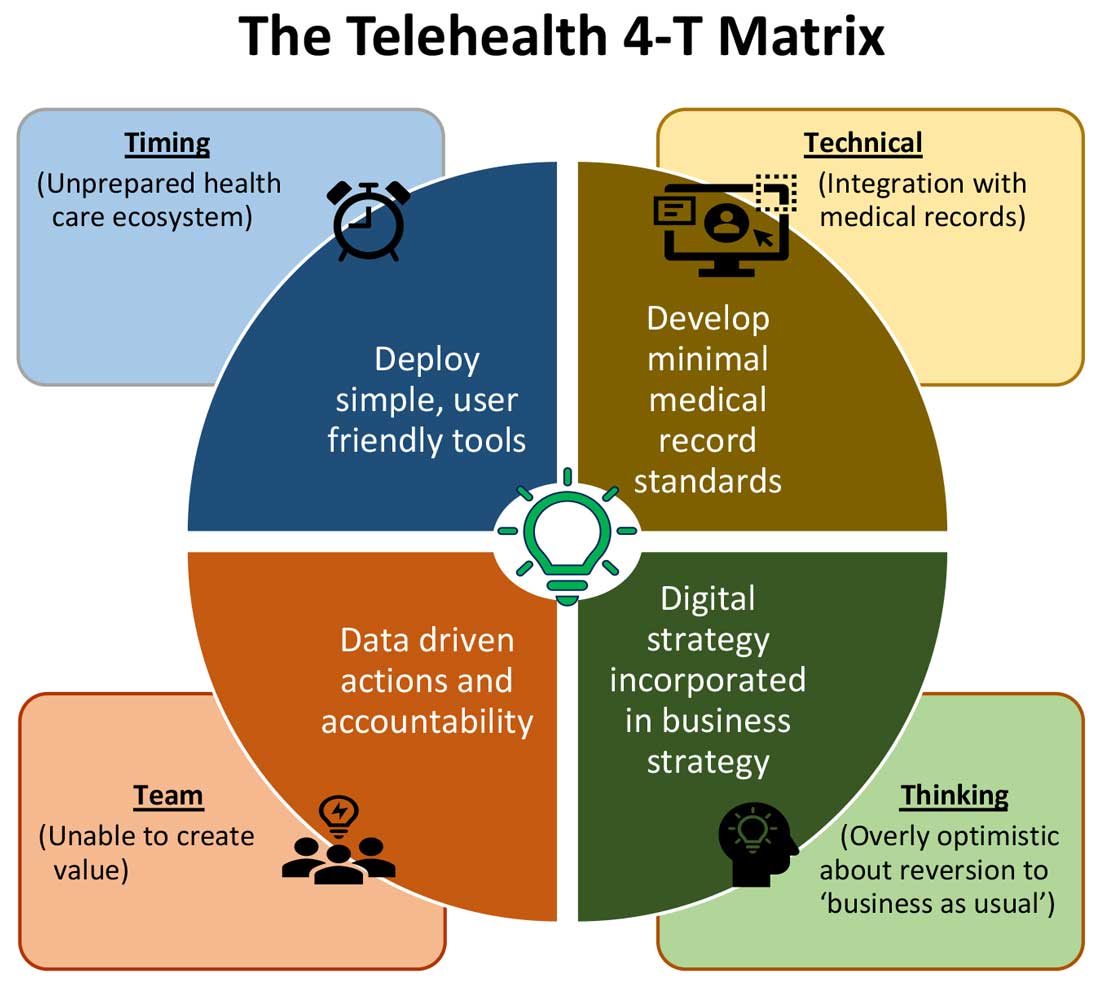

Expansion of telehealth coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and most commercial payers did not quite ride the pandemic-induced momentum across the care continuum. Hospitals are lagging far behind ambulatory care in implementing telehealth. As illustrated in the “4-T Matrix” (see graphic) we would like to examine four key reasons for such a sluggish initial uptake and try to propose four important strategies that may help us to maximize the value created by telehealth technologies.

1. Timing

The health care system has always lagged far behind other service industries in terms of technology adaptation. Because of the unique nature of health care services, face-to-face interaction supersedes all other forms of communication. A rapidly evolving pandemic was not matched by simultaneous technology education for patients and providers. The enormous choice of hard-to-navigate telehealth tools; time and labor-intensive implementation; and uncertainty around payer, policy, and regulatory expectations might have precluded providers from the rapid adoption of telehealth in the hospital setting. Patients’ specific characteristics, such as the absence of technology-centered education, information, age, comorbidities, lack of technical literacy, and dependency on caregivers contributed to the suboptimal response from patients and families.

Deploying simple, ubiquitous, user-friendly, and technologically less challenging telehealth solutions may be a better approach to increase the adoption of such solutions by providers and patients. Hospitals need to develop and distribute telehealth user guides in all possible modes of communication. Provider-centric in-service sessions, workshops, and live support by “superuser teams” often work well in reducing end-user resistance.

2. Technical

Current electronic medical records vary widely in their features and offerings, and their ability to interact with third-party software and platforms. Dissatisfaction of end users with EMRs is well known, as is their likely relationship to burnout. Recent research continues to show a strong relationship between EMR usability and the odds of burnout among physicians.5 In the current climate, administrators and health informaticists have the responsibility to avoid adding increased burdens to end users.

Another issue is the limited connectivity in many remote/rural areas that would impact implementation of telehealth platforms. Studies indicate that 33% of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband Internet to support video visits.6 The recent successful implementation of telehealth across 530 providers in 75 ambulatory practices operated by Munson Healthcare, a rural health system in northern Michigan, sheds light on the technology’s enormous potential in providing safe access to rural populations.6,7

Privacy and safety of patient data is of paramount importance. According to a national poll on healthy aging by the University of Michigan in May 2019, targeting older adults, 47% of survey responders expressed difficulty using technology and 49% of survey responders were concerned about privacy.8 Use of certification and other tools offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology would help reassure users, and the ability to capture and share images between providers would be of immense benefit in facilitating e-consults.

The need of the hour is redesigned work flow, to help providers adopt and use virtual care/telehealth efficiently. Work flow redesign must be coupled with technological advances to allow seamless integration of third-party telehealth platforms into existing EMR systems or built directly into EMRs. Use of quality metrics and analytical tools specific to telehealth would help measure the technology’s impact on patient care, outcomes, and end-user/provider experience.

3. Teams and training

Outcomes of health care interventions are often determined by the effectiveness of teams. Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and patients to a breaking point.5 Decentralized, uncoordinated, and siloed efforts by individual teams across the care continuum were contributing factors for the partial success of telehealth care delivery pathways. The hospital systems with telehealth-ready teams at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were so rare that the knowledge and technical training opportunities for innovators grew severalfold during the pandemic.

As per the American Medical Association, telehealth success is massively dependent on building the right team. Core, leadership, advisory, and implementation teams comprised of clinical representatives, end users, administrative personnel, executive members of the organization, technical experts, and payment/policy experts should be put together before implementing a telehealth strategy.9 Seamless integration of hospital-based care with ambulatory care via a telehealth platform is only complete when care managers are trained and deployed to fulfill the needs of a diverse group of patients. Deriving overall value from telehealth is only possible when there is a skill development, training and mentoring team put in place.

4. Thinking

In most U.S. hospitals, inpatient health care is equally distributed between nonprocedure and procedure-based services. Hospitals resorted to suspension of nonemergent procedures to mitigate the risk of spreading COVID-19. This was further compounded by many patients’ self-selection to defer care, an abrupt reduction in the influx of patients from the referral base because of suboptimally operating ambulatory care services, leading to low hospital occupancy.

Hospitals across the nation have gone through a massive short-term financial crunch and unfavorable cash-flow forecast, which prompted a paradoxical work-force reduction. While some argue that it may be akin to strategic myopia, the authors believed that such a response is strategically imperative to keep the hospital afloat. It is reasonable to attribute the paucity of innovation to constrained resources, and health systems are simply staying overly optimistic about “weathering the storm” and reverting soon to “business as usual.” The technological framework necessary for deploying a telehealth solution often comes with a price. Financially challenged hospital systems rarely exercise any capital-intensive activities. By contrast, telehealth adoption by ambulatory care can result in quicker resumption of patient care in community settings. A lack of operational and infrastructure synchrony between ambulatory and in-hospital systems has failed to capture telehealth-driven inpatient volume. For example, direct admissions from ambulatory telehealth referrals was a missed opportunity in several places. Referrals for labs, diagnostic tests, and other allied services could have helped hospitals offset their fixed costs. Similarly, work flows related to discharge and postdischarge follow up rarely embrace telehealth tools or telehealth care pathways. A brisk change in the health care ecosystem is partly responsible for this.

Digital strategy needs to be incorporated into business strategy. For the reasons already discussed, telehealth technology is not a “nice to have” anymore, but a “must have.” At present, providers are of the opinion that about 20% of their patient services can be delivered via a telehealth platform. Similar trends are observed among patients, as a new modality of access to care is increasingly beneficial to them. Telehealth must be incorporated in standardized hospital work flows. Use of telehealth for preoperative clearance will greatly minimize same-day surgery cancellations. Given the potential shortage in resources, telehealth adoption for inpatient consultations will help systems conserve personal protective equipment, minimize the risk of staff exposure to COVID-19, and improve efficiency.

Digital strategy also prompts the reengineering of care delivery.10 Excessive and unused physical capacity can be converted into digital care hubs. Health maintenance, prevention, health promotion, health education, and chronic disease management not only can serve a variety of patient groups but can also help address the “last-mile problem” in health care. A successful digital strategy usually has three important components – Commitment: Hospital leadership is committed to include digital transformation as a strategic objective; Cost: Digital strategy is added as a line item in the budget; and Control: Measurable metrics are put in place to monitor the performance, impact, and influence of the digital strategy.

Conclusion

For decades, most U.S. health systems occupied the periphery of technological transformation when compared to the rest of the service industry. While most health systems took a heroic approach to the adoption of telehealth during COVID-19, despite being unprepared, the need for a systematic telehealth deployment is far from being adequately fulfilled. The COVID-19 pandemic brought permanent changes to several business disciplines globally. Given the impact of the pandemic on the health and overall wellbeing of American society, the U.S. health care industry must leave no stone unturned in its quest for transformation.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark, and is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Prasad is medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management, and physician advisory services at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi, both in Jackson.

References

1. Finnegan M. “Telehealth booms amid COVID-19 crisis.” Computerworld. 2020 Apr 27. www.computerworld.com/article/3540315/telehealth-booms-amid-covid-19-crisis-virtual-care-is-here-to-stay.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

2. Department of Health & Human Services. “OCR Announces Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency.” 2020 Mar 17. www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/03/17/ocr-announces-notification-of-enforcement-discretion-for-telehealth-remote-communications-during-the-covid-19.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. “Health Expenditures.” www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

4. Bestsennyy O et al. “Telehealth: A post–COVID-19 reality?” McKinsey & Company. 2020 May 29. www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

5. Melnick ER et al. The Association Between Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability and Professional Burnout Among U.S. Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 March;95(3):476-87.

6. Hirko KA et al. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Nov;27(11):1816-8. .

7. American Academy of Family Physicians. “Study Examines Telehealth, Rural Disparities in Pandemic.” 2020 July 30. www.aafp.org/news/practice-professional-issues/20200730ruraltelehealth.html. Accessed 2020 Dec 15.

8. Kurlander J et al. “Virtual Visits: Telehealth and Older Adults.” National Poll on Healthy Aging. 2019 Oct. hdl.handle.net/2027.42/151376.

9. American Medical Association. Telehealth Implementation Playbook. 2019. www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-04/ama-telehealth-implementation-playbook.pdf.

10. Smith AC et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020 Jun;26(5):309-13.

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the transformation of Internet-based, remotely accessible innovative technologies. Internet-based customer service delivery technology was rapidly adopted and utilized by several services industries, but health care systems in most of the countries across the world faced unique challenges in adopting the technology for the delivery of health care services. The health care ecosystem of the United States was not immune to such challenges, and several significant barriers surfaced while the pandemic was underway.

Complexly structured, fragmented, unprepared, and overly burnt-out health systems in the United States arguably have fallen short of maximizing the value of telehealth in delivering safe, easily accessible, comprehensive, and cost-effective health care services. In this essay, we examine the reasons for such a suboptimal performance and discuss a few important strategies that may be useful in maximizing the value of telehealth value in several, appropriate health care services.

Hospitals and telehealth

Are hospitalists preparing ourselves “not to see” patients in a hospital-based health care delivery setting? If you have not yet started yet, now may be the right time! Yes, a certain percentage of doctor-patient encounters in hospital settings will remain virtual forever.

A well-established telehealth infrastructure is rarely found in most U.S. hospitals, although the COVID-19 pandemic has unexpectedly boosted the rapid growth of telehealth in the country.1 Public health emergency declarations in the United States in the face of the COVID-19 crisis have facilitated two important initiatives to restore health care delivery amidst formal and informal lockdowns that brought states to a grinding halt. These extend from expansion of virtual services, including telehealth, virtual check-ins, and e-visits, to the decision by the Department of Health & Human Services Office of Civil Rights to exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for the use of relatively inexpensive, non–public-facing mobile and other audiovisual technology tools.2

Hospital-based care in the United States taps nearly 33% of national health expenditure. An additional 30% of national health expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities is indirectly influenced by care delivered at health care facilities.3 Studies show that about 20% of ED visits could potentially be avoided via virtual urgent care offerings.4 A rapidly changing health care ecosystem is proving formidable for most hospital systems, and a test for their resilience and agility. Not just the implementation of telehealth is challenging, but getting it right is the key success factor.

Hospital-based telehealth

Expansion of telehealth coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and most commercial payers did not quite ride the pandemic-induced momentum across the care continuum. Hospitals are lagging far behind ambulatory care in implementing telehealth. As illustrated in the “4-T Matrix” (see graphic) we would like to examine four key reasons for such a sluggish initial uptake and try to propose four important strategies that may help us to maximize the value created by telehealth technologies.

1. Timing

The health care system has always lagged far behind other service industries in terms of technology adaptation. Because of the unique nature of health care services, face-to-face interaction supersedes all other forms of communication. A rapidly evolving pandemic was not matched by simultaneous technology education for patients and providers. The enormous choice of hard-to-navigate telehealth tools; time and labor-intensive implementation; and uncertainty around payer, policy, and regulatory expectations might have precluded providers from the rapid adoption of telehealth in the hospital setting. Patients’ specific characteristics, such as the absence of technology-centered education, information, age, comorbidities, lack of technical literacy, and dependency on caregivers contributed to the suboptimal response from patients and families.

Deploying simple, ubiquitous, user-friendly, and technologically less challenging telehealth solutions may be a better approach to increase the adoption of such solutions by providers and patients. Hospitals need to develop and distribute telehealth user guides in all possible modes of communication. Provider-centric in-service sessions, workshops, and live support by “superuser teams” often work well in reducing end-user resistance.

2. Technical

Current electronic medical records vary widely in their features and offerings, and their ability to interact with third-party software and platforms. Dissatisfaction of end users with EMRs is well known, as is their likely relationship to burnout. Recent research continues to show a strong relationship between EMR usability and the odds of burnout among physicians.5 In the current climate, administrators and health informaticists have the responsibility to avoid adding increased burdens to end users.

Another issue is the limited connectivity in many remote/rural areas that would impact implementation of telehealth platforms. Studies indicate that 33% of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband Internet to support video visits.6 The recent successful implementation of telehealth across 530 providers in 75 ambulatory practices operated by Munson Healthcare, a rural health system in northern Michigan, sheds light on the technology’s enormous potential in providing safe access to rural populations.6,7

Privacy and safety of patient data is of paramount importance. According to a national poll on healthy aging by the University of Michigan in May 2019, targeting older adults, 47% of survey responders expressed difficulty using technology and 49% of survey responders were concerned about privacy.8 Use of certification and other tools offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology would help reassure users, and the ability to capture and share images between providers would be of immense benefit in facilitating e-consults.

The need of the hour is redesigned work flow, to help providers adopt and use virtual care/telehealth efficiently. Work flow redesign must be coupled with technological advances to allow seamless integration of third-party telehealth platforms into existing EMR systems or built directly into EMRs. Use of quality metrics and analytical tools specific to telehealth would help measure the technology’s impact on patient care, outcomes, and end-user/provider experience.

3. Teams and training

Outcomes of health care interventions are often determined by the effectiveness of teams. Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and patients to a breaking point.5 Decentralized, uncoordinated, and siloed efforts by individual teams across the care continuum were contributing factors for the partial success of telehealth care delivery pathways. The hospital systems with telehealth-ready teams at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were so rare that the knowledge and technical training opportunities for innovators grew severalfold during the pandemic.

As per the American Medical Association, telehealth success is massively dependent on building the right team. Core, leadership, advisory, and implementation teams comprised of clinical representatives, end users, administrative personnel, executive members of the organization, technical experts, and payment/policy experts should be put together before implementing a telehealth strategy.9 Seamless integration of hospital-based care with ambulatory care via a telehealth platform is only complete when care managers are trained and deployed to fulfill the needs of a diverse group of patients. Deriving overall value from telehealth is only possible when there is a skill development, training and mentoring team put in place.

4. Thinking

In most U.S. hospitals, inpatient health care is equally distributed between nonprocedure and procedure-based services. Hospitals resorted to suspension of nonemergent procedures to mitigate the risk of spreading COVID-19. This was further compounded by many patients’ self-selection to defer care, an abrupt reduction in the influx of patients from the referral base because of suboptimally operating ambulatory care services, leading to low hospital occupancy.

Hospitals across the nation have gone through a massive short-term financial crunch and unfavorable cash-flow forecast, which prompted a paradoxical work-force reduction. While some argue that it may be akin to strategic myopia, the authors believed that such a response is strategically imperative to keep the hospital afloat. It is reasonable to attribute the paucity of innovation to constrained resources, and health systems are simply staying overly optimistic about “weathering the storm” and reverting soon to “business as usual.” The technological framework necessary for deploying a telehealth solution often comes with a price. Financially challenged hospital systems rarely exercise any capital-intensive activities. By contrast, telehealth adoption by ambulatory care can result in quicker resumption of patient care in community settings. A lack of operational and infrastructure synchrony between ambulatory and in-hospital systems has failed to capture telehealth-driven inpatient volume. For example, direct admissions from ambulatory telehealth referrals was a missed opportunity in several places. Referrals for labs, diagnostic tests, and other allied services could have helped hospitals offset their fixed costs. Similarly, work flows related to discharge and postdischarge follow up rarely embrace telehealth tools or telehealth care pathways. A brisk change in the health care ecosystem is partly responsible for this.

Digital strategy needs to be incorporated into business strategy. For the reasons already discussed, telehealth technology is not a “nice to have” anymore, but a “must have.” At present, providers are of the opinion that about 20% of their patient services can be delivered via a telehealth platform. Similar trends are observed among patients, as a new modality of access to care is increasingly beneficial to them. Telehealth must be incorporated in standardized hospital work flows. Use of telehealth for preoperative clearance will greatly minimize same-day surgery cancellations. Given the potential shortage in resources, telehealth adoption for inpatient consultations will help systems conserve personal protective equipment, minimize the risk of staff exposure to COVID-19, and improve efficiency.

Digital strategy also prompts the reengineering of care delivery.10 Excessive and unused physical capacity can be converted into digital care hubs. Health maintenance, prevention, health promotion, health education, and chronic disease management not only can serve a variety of patient groups but can also help address the “last-mile problem” in health care. A successful digital strategy usually has three important components – Commitment: Hospital leadership is committed to include digital transformation as a strategic objective; Cost: Digital strategy is added as a line item in the budget; and Control: Measurable metrics are put in place to monitor the performance, impact, and influence of the digital strategy.

Conclusion

For decades, most U.S. health systems occupied the periphery of technological transformation when compared to the rest of the service industry. While most health systems took a heroic approach to the adoption of telehealth during COVID-19, despite being unprepared, the need for a systematic telehealth deployment is far from being adequately fulfilled. The COVID-19 pandemic brought permanent changes to several business disciplines globally. Given the impact of the pandemic on the health and overall wellbeing of American society, the U.S. health care industry must leave no stone unturned in its quest for transformation.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark, and is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Prasad is medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management, and physician advisory services at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi, both in Jackson.

References

1. Finnegan M. “Telehealth booms amid COVID-19 crisis.” Computerworld. 2020 Apr 27. www.computerworld.com/article/3540315/telehealth-booms-amid-covid-19-crisis-virtual-care-is-here-to-stay.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

2. Department of Health & Human Services. “OCR Announces Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency.” 2020 Mar 17. www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/03/17/ocr-announces-notification-of-enforcement-discretion-for-telehealth-remote-communications-during-the-covid-19.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. “Health Expenditures.” www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

4. Bestsennyy O et al. “Telehealth: A post–COVID-19 reality?” McKinsey & Company. 2020 May 29. www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

5. Melnick ER et al. The Association Between Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability and Professional Burnout Among U.S. Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 March;95(3):476-87.

6. Hirko KA et al. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Nov;27(11):1816-8. .

7. American Academy of Family Physicians. “Study Examines Telehealth, Rural Disparities in Pandemic.” 2020 July 30. www.aafp.org/news/practice-professional-issues/20200730ruraltelehealth.html. Accessed 2020 Dec 15.

8. Kurlander J et al. “Virtual Visits: Telehealth and Older Adults.” National Poll on Healthy Aging. 2019 Oct. hdl.handle.net/2027.42/151376.

9. American Medical Association. Telehealth Implementation Playbook. 2019. www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-04/ama-telehealth-implementation-playbook.pdf.

10. Smith AC et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020 Jun;26(5):309-13.

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the transformation of Internet-based, remotely accessible innovative technologies. Internet-based customer service delivery technology was rapidly adopted and utilized by several services industries, but health care systems in most of the countries across the world faced unique challenges in adopting the technology for the delivery of health care services. The health care ecosystem of the United States was not immune to such challenges, and several significant barriers surfaced while the pandemic was underway.

Complexly structured, fragmented, unprepared, and overly burnt-out health systems in the United States arguably have fallen short of maximizing the value of telehealth in delivering safe, easily accessible, comprehensive, and cost-effective health care services. In this essay, we examine the reasons for such a suboptimal performance and discuss a few important strategies that may be useful in maximizing the value of telehealth value in several, appropriate health care services.

Hospitals and telehealth

Are hospitalists preparing ourselves “not to see” patients in a hospital-based health care delivery setting? If you have not yet started yet, now may be the right time! Yes, a certain percentage of doctor-patient encounters in hospital settings will remain virtual forever.

A well-established telehealth infrastructure is rarely found in most U.S. hospitals, although the COVID-19 pandemic has unexpectedly boosted the rapid growth of telehealth in the country.1 Public health emergency declarations in the United States in the face of the COVID-19 crisis have facilitated two important initiatives to restore health care delivery amidst formal and informal lockdowns that brought states to a grinding halt. These extend from expansion of virtual services, including telehealth, virtual check-ins, and e-visits, to the decision by the Department of Health & Human Services Office of Civil Rights to exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for the use of relatively inexpensive, non–public-facing mobile and other audiovisual technology tools.2

Hospital-based care in the United States taps nearly 33% of national health expenditure. An additional 30% of national health expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities is indirectly influenced by care delivered at health care facilities.3 Studies show that about 20% of ED visits could potentially be avoided via virtual urgent care offerings.4 A rapidly changing health care ecosystem is proving formidable for most hospital systems, and a test for their resilience and agility. Not just the implementation of telehealth is challenging, but getting it right is the key success factor.

Hospital-based telehealth

Expansion of telehealth coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and most commercial payers did not quite ride the pandemic-induced momentum across the care continuum. Hospitals are lagging far behind ambulatory care in implementing telehealth. As illustrated in the “4-T Matrix” (see graphic) we would like to examine four key reasons for such a sluggish initial uptake and try to propose four important strategies that may help us to maximize the value created by telehealth technologies.

1. Timing

The health care system has always lagged far behind other service industries in terms of technology adaptation. Because of the unique nature of health care services, face-to-face interaction supersedes all other forms of communication. A rapidly evolving pandemic was not matched by simultaneous technology education for patients and providers. The enormous choice of hard-to-navigate telehealth tools; time and labor-intensive implementation; and uncertainty around payer, policy, and regulatory expectations might have precluded providers from the rapid adoption of telehealth in the hospital setting. Patients’ specific characteristics, such as the absence of technology-centered education, information, age, comorbidities, lack of technical literacy, and dependency on caregivers contributed to the suboptimal response from patients and families.

Deploying simple, ubiquitous, user-friendly, and technologically less challenging telehealth solutions may be a better approach to increase the adoption of such solutions by providers and patients. Hospitals need to develop and distribute telehealth user guides in all possible modes of communication. Provider-centric in-service sessions, workshops, and live support by “superuser teams” often work well in reducing end-user resistance.

2. Technical

Current electronic medical records vary widely in their features and offerings, and their ability to interact with third-party software and platforms. Dissatisfaction of end users with EMRs is well known, as is their likely relationship to burnout. Recent research continues to show a strong relationship between EMR usability and the odds of burnout among physicians.5 In the current climate, administrators and health informaticists have the responsibility to avoid adding increased burdens to end users.

Another issue is the limited connectivity in many remote/rural areas that would impact implementation of telehealth platforms. Studies indicate that 33% of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband Internet to support video visits.6 The recent successful implementation of telehealth across 530 providers in 75 ambulatory practices operated by Munson Healthcare, a rural health system in northern Michigan, sheds light on the technology’s enormous potential in providing safe access to rural populations.6,7

Privacy and safety of patient data is of paramount importance. According to a national poll on healthy aging by the University of Michigan in May 2019, targeting older adults, 47% of survey responders expressed difficulty using technology and 49% of survey responders were concerned about privacy.8 Use of certification and other tools offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology would help reassure users, and the ability to capture and share images between providers would be of immense benefit in facilitating e-consults.

The need of the hour is redesigned work flow, to help providers adopt and use virtual care/telehealth efficiently. Work flow redesign must be coupled with technological advances to allow seamless integration of third-party telehealth platforms into existing EMR systems or built directly into EMRs. Use of quality metrics and analytical tools specific to telehealth would help measure the technology’s impact on patient care, outcomes, and end-user/provider experience.

3. Teams and training

Outcomes of health care interventions are often determined by the effectiveness of teams. Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and patients to a breaking point.5 Decentralized, uncoordinated, and siloed efforts by individual teams across the care continuum were contributing factors for the partial success of telehealth care delivery pathways. The hospital systems with telehealth-ready teams at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were so rare that the knowledge and technical training opportunities for innovators grew severalfold during the pandemic.

As per the American Medical Association, telehealth success is massively dependent on building the right team. Core, leadership, advisory, and implementation teams comprised of clinical representatives, end users, administrative personnel, executive members of the organization, technical experts, and payment/policy experts should be put together before implementing a telehealth strategy.9 Seamless integration of hospital-based care with ambulatory care via a telehealth platform is only complete when care managers are trained and deployed to fulfill the needs of a diverse group of patients. Deriving overall value from telehealth is only possible when there is a skill development, training and mentoring team put in place.

4. Thinking

In most U.S. hospitals, inpatient health care is equally distributed between nonprocedure and procedure-based services. Hospitals resorted to suspension of nonemergent procedures to mitigate the risk of spreading COVID-19. This was further compounded by many patients’ self-selection to defer care, an abrupt reduction in the influx of patients from the referral base because of suboptimally operating ambulatory care services, leading to low hospital occupancy.

Hospitals across the nation have gone through a massive short-term financial crunch and unfavorable cash-flow forecast, which prompted a paradoxical work-force reduction. While some argue that it may be akin to strategic myopia, the authors believed that such a response is strategically imperative to keep the hospital afloat. It is reasonable to attribute the paucity of innovation to constrained resources, and health systems are simply staying overly optimistic about “weathering the storm” and reverting soon to “business as usual.” The technological framework necessary for deploying a telehealth solution often comes with a price. Financially challenged hospital systems rarely exercise any capital-intensive activities. By contrast, telehealth adoption by ambulatory care can result in quicker resumption of patient care in community settings. A lack of operational and infrastructure synchrony between ambulatory and in-hospital systems has failed to capture telehealth-driven inpatient volume. For example, direct admissions from ambulatory telehealth referrals was a missed opportunity in several places. Referrals for labs, diagnostic tests, and other allied services could have helped hospitals offset their fixed costs. Similarly, work flows related to discharge and postdischarge follow up rarely embrace telehealth tools or telehealth care pathways. A brisk change in the health care ecosystem is partly responsible for this.

Digital strategy needs to be incorporated into business strategy. For the reasons already discussed, telehealth technology is not a “nice to have” anymore, but a “must have.” At present, providers are of the opinion that about 20% of their patient services can be delivered via a telehealth platform. Similar trends are observed among patients, as a new modality of access to care is increasingly beneficial to them. Telehealth must be incorporated in standardized hospital work flows. Use of telehealth for preoperative clearance will greatly minimize same-day surgery cancellations. Given the potential shortage in resources, telehealth adoption for inpatient consultations will help systems conserve personal protective equipment, minimize the risk of staff exposure to COVID-19, and improve efficiency.

Digital strategy also prompts the reengineering of care delivery.10 Excessive and unused physical capacity can be converted into digital care hubs. Health maintenance, prevention, health promotion, health education, and chronic disease management not only can serve a variety of patient groups but can also help address the “last-mile problem” in health care. A successful digital strategy usually has three important components – Commitment: Hospital leadership is committed to include digital transformation as a strategic objective; Cost: Digital strategy is added as a line item in the budget; and Control: Measurable metrics are put in place to monitor the performance, impact, and influence of the digital strategy.

Conclusion

For decades, most U.S. health systems occupied the periphery of technological transformation when compared to the rest of the service industry. While most health systems took a heroic approach to the adoption of telehealth during COVID-19, despite being unprepared, the need for a systematic telehealth deployment is far from being adequately fulfilled. The COVID-19 pandemic brought permanent changes to several business disciplines globally. Given the impact of the pandemic on the health and overall wellbeing of American society, the U.S. health care industry must leave no stone unturned in its quest for transformation.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark, and is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Prasad is medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management, and physician advisory services at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi, both in Jackson.

References

1. Finnegan M. “Telehealth booms amid COVID-19 crisis.” Computerworld. 2020 Apr 27. www.computerworld.com/article/3540315/telehealth-booms-amid-covid-19-crisis-virtual-care-is-here-to-stay.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

2. Department of Health & Human Services. “OCR Announces Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency.” 2020 Mar 17. www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/03/17/ocr-announces-notification-of-enforcement-discretion-for-telehealth-remote-communications-during-the-covid-19.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. “Health Expenditures.” www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

4. Bestsennyy O et al. “Telehealth: A post–COVID-19 reality?” McKinsey & Company. 2020 May 29. www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

5. Melnick ER et al. The Association Between Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability and Professional Burnout Among U.S. Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 March;95(3):476-87.

6. Hirko KA et al. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Nov;27(11):1816-8. .

7. American Academy of Family Physicians. “Study Examines Telehealth, Rural Disparities in Pandemic.” 2020 July 30. www.aafp.org/news/practice-professional-issues/20200730ruraltelehealth.html. Accessed 2020 Dec 15.

8. Kurlander J et al. “Virtual Visits: Telehealth and Older Adults.” National Poll on Healthy Aging. 2019 Oct. hdl.handle.net/2027.42/151376.

9. American Medical Association. Telehealth Implementation Playbook. 2019. www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-04/ama-telehealth-implementation-playbook.pdf.

10. Smith AC et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020 Jun;26(5):309-13.

Hospitalist movers and shakers – March 2021

Vivek H. Murthy, MD, was named by President Joe Biden as his selection for Surgeon General of the United States. Dr. Murthy filled the same role from 2014-17 during President Barack Obama’s administration.

Dr. Murthy was a hospitalist and an instructor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital at Harvard Medical School prior to becoming surgeon general the first time. He also is the founder of Doctors for America.

David Tupponce, MD, recently was named the new president of Allegheny Health Network’s Grove City (Pa.) Medical Center. He takes over for interim president Allan Klapper, MD, who filled the position since August 2020.

Dr. Tupponce comes to Grove City Medical Center after a successful tenure as president of Central Maine Medical Center (Lewiston, Maine), where he grew its physician group and fine-tuned the hospital quality program. Prior to that, he was chief executive officer at Tenet Healthcare’s Abrazo Scottsdale (Ariz.) Campus and CEO at Paradise Valley Hospital (Phoenix, Ariz.).

Dr. Tupponce is familiar with western Pennsylvania, having earned a master’s degree in medical management from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. He also was chief resident at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Malcolm Mar Fan, MD, has been elevated to medical director of the Hospitalist Group at Evangelical Community Hospital (Lewisburg, Pa.). In the newly established position, Dr. Mar Fan will oversee all operations for the facility’s hospitalist program.

Dr. Mar Fan has been a hospitalist at Evangelical since 2014 after completing his internist residency at Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia. He has played a major role on Evangelical’s Peri-operative Glucose Management Committee and its Informatics Committee for Impatient and Outpatient Electronic Health Records.

Lyon County (Kansas) recently announced that Ladun Oyenuga, MD, has been appointed as public health officer for the county. She began her tenure on January 1.

Dr. Oyenuga is a hospitalist at Newman Regional Health (Emporia, Kan.). She is a native of Nigeria and did her residency at Harlem (N.Y.) Hospital Center. She has been with Newman since 2017.

Cherese Mari Laulhere BirthCare Center (Long Beach, Calif.) recently announced the addition of an OB hospitalist program at Miller Children’s & Women’s Hospital. OB hospitalists, or laborists, care for women with obstetrical issues while in the hospital.

At Cherese Mari Laulhere, OB hospitalists will be on hand 24 hours a day to assist patients’ OB/GYNs or to fill in if the personal physician cannot get to the hospital quickly.

Hospitalists at Nationwide Children’s (Columbus, Ohio) are now providing care for children who are hospitalized at Adena Regional Medical Center (Chillicothe, Ohio).

It is an expansion of an ongoing partnership between the two hospitals. Adena and Nationwide Children’s have been working together in helping to care for children in the south central and southern Ohio region since 2011. Nationwide Children’s hospitalists will round in special care and the well-baby nursery at Adena, as well as provide education programs for Adena providers and staff.

MultiCare Health System (Tacoma, Wash.) has announced that it will expand its hospitalist program partnership with Sound Physicians, also based in Tacoma, to create a region-wide, cohesive group of providers. The goal is to help ensure efficient management of inpatient populations as a region instead of at the individual hospital level, and will allow MultiCare to implement standard tools, processes and regionwide best practices.

The hospitalist programs at Tacoma General Hospital, Allenmore Hospital and Covington Medical Center will transition to Sound Physicians on April 5, 2021. Sound hospitalists are already working at three other MultiCare facilities – Tacoma General Hospital, Allenmore Hospital, and Covington Medical Center.

Vivek H. Murthy, MD, was named by President Joe Biden as his selection for Surgeon General of the United States. Dr. Murthy filled the same role from 2014-17 during President Barack Obama’s administration.

Dr. Murthy was a hospitalist and an instructor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital at Harvard Medical School prior to becoming surgeon general the first time. He also is the founder of Doctors for America.

David Tupponce, MD, recently was named the new president of Allegheny Health Network’s Grove City (Pa.) Medical Center. He takes over for interim president Allan Klapper, MD, who filled the position since August 2020.

Dr. Tupponce comes to Grove City Medical Center after a successful tenure as president of Central Maine Medical Center (Lewiston, Maine), where he grew its physician group and fine-tuned the hospital quality program. Prior to that, he was chief executive officer at Tenet Healthcare’s Abrazo Scottsdale (Ariz.) Campus and CEO at Paradise Valley Hospital (Phoenix, Ariz.).

Dr. Tupponce is familiar with western Pennsylvania, having earned a master’s degree in medical management from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. He also was chief resident at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Malcolm Mar Fan, MD, has been elevated to medical director of the Hospitalist Group at Evangelical Community Hospital (Lewisburg, Pa.). In the newly established position, Dr. Mar Fan will oversee all operations for the facility’s hospitalist program.

Dr. Mar Fan has been a hospitalist at Evangelical since 2014 after completing his internist residency at Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia. He has played a major role on Evangelical’s Peri-operative Glucose Management Committee and its Informatics Committee for Impatient and Outpatient Electronic Health Records.

Lyon County (Kansas) recently announced that Ladun Oyenuga, MD, has been appointed as public health officer for the county. She began her tenure on January 1.

Dr. Oyenuga is a hospitalist at Newman Regional Health (Emporia, Kan.). She is a native of Nigeria and did her residency at Harlem (N.Y.) Hospital Center. She has been with Newman since 2017.

Cherese Mari Laulhere BirthCare Center (Long Beach, Calif.) recently announced the addition of an OB hospitalist program at Miller Children’s & Women’s Hospital. OB hospitalists, or laborists, care for women with obstetrical issues while in the hospital.

At Cherese Mari Laulhere, OB hospitalists will be on hand 24 hours a day to assist patients’ OB/GYNs or to fill in if the personal physician cannot get to the hospital quickly.

Hospitalists at Nationwide Children’s (Columbus, Ohio) are now providing care for children who are hospitalized at Adena Regional Medical Center (Chillicothe, Ohio).

It is an expansion of an ongoing partnership between the two hospitals. Adena and Nationwide Children’s have been working together in helping to care for children in the south central and southern Ohio region since 2011. Nationwide Children’s hospitalists will round in special care and the well-baby nursery at Adena, as well as provide education programs for Adena providers and staff.

MultiCare Health System (Tacoma, Wash.) has announced that it will expand its hospitalist program partnership with Sound Physicians, also based in Tacoma, to create a region-wide, cohesive group of providers. The goal is to help ensure efficient management of inpatient populations as a region instead of at the individual hospital level, and will allow MultiCare to implement standard tools, processes and regionwide best practices.

The hospitalist programs at Tacoma General Hospital, Allenmore Hospital and Covington Medical Center will transition to Sound Physicians on April 5, 2021. Sound hospitalists are already working at three other MultiCare facilities – Tacoma General Hospital, Allenmore Hospital, and Covington Medical Center.

Vivek H. Murthy, MD, was named by President Joe Biden as his selection for Surgeon General of the United States. Dr. Murthy filled the same role from 2014-17 during President Barack Obama’s administration.

Dr. Murthy was a hospitalist and an instructor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital at Harvard Medical School prior to becoming surgeon general the first time. He also is the founder of Doctors for America.

David Tupponce, MD, recently was named the new president of Allegheny Health Network’s Grove City (Pa.) Medical Center. He takes over for interim president Allan Klapper, MD, who filled the position since August 2020.

Dr. Tupponce comes to Grove City Medical Center after a successful tenure as president of Central Maine Medical Center (Lewiston, Maine), where he grew its physician group and fine-tuned the hospital quality program. Prior to that, he was chief executive officer at Tenet Healthcare’s Abrazo Scottsdale (Ariz.) Campus and CEO at Paradise Valley Hospital (Phoenix, Ariz.).