User login

October 2018

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) can affect individuals regardless of age, race, or sex, but ACD accounts for 20% of all contact dermatitis reactions. ACD results in an inflammatory reaction in those who have been previously sensitized to an allergen. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

Once sensitized, epidermal antigen-presenting cells (APCs) called Langerhans cells process the allergen and present it in a complex on the surface of the cell to a CD4+ T cell. Subsequently, inflammatory cytokines and mediators are released, resulting in an allergic cutaneous (eczematous) reaction. Lesions may appear to be vesicular or bullous. Occasionally, a generalized eruption may occur. With repeated exposure, reactions may be acute or chronic.

Common causes of allergic contact dermatitis include toxicodendron plants (poison ivy, oak, and sumac; cashew nut tree; and mango), metals (nickel and gold), topical antibiotics (neomycin and bacitracin), fragrance and Balsam of Peru, deodorant, preservatives (formaldehyde), and rubber (elastic and gloves).

Patch testing is the standard means of detecting which allergen is causing the sensitization in an individual. The Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (TRUE) test or individually prepared aluminum (Finn) chambers containing the most common allergens are applied to the patient’s upper back. The patches are removed after 48 hours and read, and then reevaluated at day 4 or 5. Positive reactions appear as eczematous or vesicular papules or plaques.

Treatment includes avoidance of the allergens. Topical corticosteroid creams are helpful. For severe or generalized reactions, oral prednisone may be used. It is important to note that patient may be allergic to topical steroids. Patch testing can be performed to elucidate such allergens.

In contrast, 80% of contact dermatitis reactions are irritant, not allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results is a local inflammatory reaction in people who have come into contact with a substance. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure. Common causes include alkalis (detergents, soaps), acids (often found as an industrial work exposure), metals, solvents (occupational dermatitis), hydrocarbons, and chlorinated compounds.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) can affect individuals regardless of age, race, or sex, but ACD accounts for 20% of all contact dermatitis reactions. ACD results in an inflammatory reaction in those who have been previously sensitized to an allergen. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

Once sensitized, epidermal antigen-presenting cells (APCs) called Langerhans cells process the allergen and present it in a complex on the surface of the cell to a CD4+ T cell. Subsequently, inflammatory cytokines and mediators are released, resulting in an allergic cutaneous (eczematous) reaction. Lesions may appear to be vesicular or bullous. Occasionally, a generalized eruption may occur. With repeated exposure, reactions may be acute or chronic.

Common causes of allergic contact dermatitis include toxicodendron plants (poison ivy, oak, and sumac; cashew nut tree; and mango), metals (nickel and gold), topical antibiotics (neomycin and bacitracin), fragrance and Balsam of Peru, deodorant, preservatives (formaldehyde), and rubber (elastic and gloves).

Patch testing is the standard means of detecting which allergen is causing the sensitization in an individual. The Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (TRUE) test or individually prepared aluminum (Finn) chambers containing the most common allergens are applied to the patient’s upper back. The patches are removed after 48 hours and read, and then reevaluated at day 4 or 5. Positive reactions appear as eczematous or vesicular papules or plaques.

Treatment includes avoidance of the allergens. Topical corticosteroid creams are helpful. For severe or generalized reactions, oral prednisone may be used. It is important to note that patient may be allergic to topical steroids. Patch testing can be performed to elucidate such allergens.

In contrast, 80% of contact dermatitis reactions are irritant, not allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results is a local inflammatory reaction in people who have come into contact with a substance. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure. Common causes include alkalis (detergents, soaps), acids (often found as an industrial work exposure), metals, solvents (occupational dermatitis), hydrocarbons, and chlorinated compounds.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) can affect individuals regardless of age, race, or sex, but ACD accounts for 20% of all contact dermatitis reactions. ACD results in an inflammatory reaction in those who have been previously sensitized to an allergen. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

Once sensitized, epidermal antigen-presenting cells (APCs) called Langerhans cells process the allergen and present it in a complex on the surface of the cell to a CD4+ T cell. Subsequently, inflammatory cytokines and mediators are released, resulting in an allergic cutaneous (eczematous) reaction. Lesions may appear to be vesicular or bullous. Occasionally, a generalized eruption may occur. With repeated exposure, reactions may be acute or chronic.

Common causes of allergic contact dermatitis include toxicodendron plants (poison ivy, oak, and sumac; cashew nut tree; and mango), metals (nickel and gold), topical antibiotics (neomycin and bacitracin), fragrance and Balsam of Peru, deodorant, preservatives (formaldehyde), and rubber (elastic and gloves).

Patch testing is the standard means of detecting which allergen is causing the sensitization in an individual. The Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (TRUE) test or individually prepared aluminum (Finn) chambers containing the most common allergens are applied to the patient’s upper back. The patches are removed after 48 hours and read, and then reevaluated at day 4 or 5. Positive reactions appear as eczematous or vesicular papules or plaques.

Treatment includes avoidance of the allergens. Topical corticosteroid creams are helpful. For severe or generalized reactions, oral prednisone may be used. It is important to note that patient may be allergic to topical steroids. Patch testing can be performed to elucidate such allergens.

In contrast, 80% of contact dermatitis reactions are irritant, not allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results is a local inflammatory reaction in people who have come into contact with a substance. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure. Common causes include alkalis (detergents, soaps), acids (often found as an industrial work exposure), metals, solvents (occupational dermatitis), hydrocarbons, and chlorinated compounds.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 30-year-old female presented with 2 days of intensely pruritic erythematous papules and vesicles on her bilateral arms and hands. The lesions began appearing 1 day after a camping trip. Her neck, chest, and upper back were clear.

Make The Diagnosis - September 2018

Some have postulated an infectious agent as the cause. Atopic dermatitis may confer an increased risk because of the chronic stimulation of T cells. Males are more commonly affected than females by a 2:1 ratio. A worse prognosis is associated with advanced age. Children and adolescents may be affected as well.

With mycosis fungoides, there are three main types of skin lesions: patch, plaque, and tumor. Patients will progress from patch to plaque to tumor stage in classic MF. Often, lesions begin as scaly, erythematous patches that resemble eczema. Because of the nonspecific nature of early lesions, the median duration from the onset of skin lesions to the diagnosis of MF is 4-6 years. Patch stage lesions may be pruritic or asymptomatic. Commonly, they present in non–sun-exposed areas, such as the buttocks. Annular, infiltrated, red-brown or violaceous plaques can develop, which represent malignant T-cell infiltration. Many patients never progress past the plaque stage. Tumor stage MF is more aggressive, with nodules that may undergo necrosis and ulceration.

The leukemic form of MF is Sézary syndrome. Patients present with pruritic erythroderma and lymphadenopathy. Nail dystrophy, scaling of palms and soles, and alopecia may be present. A peripheral blood smear reveals Sézary cells, which are large, hyperconvoluted lymphocytes. The count of Sézary cells is usually greater than 1000 cells/mm3.

Histology of early lesions may not be diagnostic for CTCL. Often, biopsies will be read as eczematous or psoriasiform for years before the diagnosis of MF is made. Classically, epidermotropism (single-cell exocytosis of lymphocytes into the epidermis) is present. Advanced stages may show a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes in the dermis. Groups of lymphocytes in the epidermis form Pautrier’s microabscesses. Mycosis cells may exhibit cerebriform nuclei. Neoplastic cells in MF are CD3+, CD4+, CD45RO+, CD8–. Tissue can be sent for T-cell gene rearrangement polymerase chain reaction. The presence of monoclonal T-cell gene receptor rearrangements can aid in the diagnosis of MF.

Treatment includes topical steroids, mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard) or bexarotene gel, PUVA therapy, and narrow-band UVB light for limited and/or patch disease. Localized radiotherapy can be used for more resistant lesions. Topical therapies are preferred in the early stages in MF. Systemic treatments for patients who do not respond to local therapy, or in more advanced disease include methotrexate, interferon-alpha, oral bexarotene, denileukin diftitox, and combination chemotherapy. Photopheresis is reserved for erythrodermic disease.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Some have postulated an infectious agent as the cause. Atopic dermatitis may confer an increased risk because of the chronic stimulation of T cells. Males are more commonly affected than females by a 2:1 ratio. A worse prognosis is associated with advanced age. Children and adolescents may be affected as well.

With mycosis fungoides, there are three main types of skin lesions: patch, plaque, and tumor. Patients will progress from patch to plaque to tumor stage in classic MF. Often, lesions begin as scaly, erythematous patches that resemble eczema. Because of the nonspecific nature of early lesions, the median duration from the onset of skin lesions to the diagnosis of MF is 4-6 years. Patch stage lesions may be pruritic or asymptomatic. Commonly, they present in non–sun-exposed areas, such as the buttocks. Annular, infiltrated, red-brown or violaceous plaques can develop, which represent malignant T-cell infiltration. Many patients never progress past the plaque stage. Tumor stage MF is more aggressive, with nodules that may undergo necrosis and ulceration.

The leukemic form of MF is Sézary syndrome. Patients present with pruritic erythroderma and lymphadenopathy. Nail dystrophy, scaling of palms and soles, and alopecia may be present. A peripheral blood smear reveals Sézary cells, which are large, hyperconvoluted lymphocytes. The count of Sézary cells is usually greater than 1000 cells/mm3.

Histology of early lesions may not be diagnostic for CTCL. Often, biopsies will be read as eczematous or psoriasiform for years before the diagnosis of MF is made. Classically, epidermotropism (single-cell exocytosis of lymphocytes into the epidermis) is present. Advanced stages may show a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes in the dermis. Groups of lymphocytes in the epidermis form Pautrier’s microabscesses. Mycosis cells may exhibit cerebriform nuclei. Neoplastic cells in MF are CD3+, CD4+, CD45RO+, CD8–. Tissue can be sent for T-cell gene rearrangement polymerase chain reaction. The presence of monoclonal T-cell gene receptor rearrangements can aid in the diagnosis of MF.

Treatment includes topical steroids, mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard) or bexarotene gel, PUVA therapy, and narrow-band UVB light for limited and/or patch disease. Localized radiotherapy can be used for more resistant lesions. Topical therapies are preferred in the early stages in MF. Systemic treatments for patients who do not respond to local therapy, or in more advanced disease include methotrexate, interferon-alpha, oral bexarotene, denileukin diftitox, and combination chemotherapy. Photopheresis is reserved for erythrodermic disease.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Some have postulated an infectious agent as the cause. Atopic dermatitis may confer an increased risk because of the chronic stimulation of T cells. Males are more commonly affected than females by a 2:1 ratio. A worse prognosis is associated with advanced age. Children and adolescents may be affected as well.

With mycosis fungoides, there are three main types of skin lesions: patch, plaque, and tumor. Patients will progress from patch to plaque to tumor stage in classic MF. Often, lesions begin as scaly, erythematous patches that resemble eczema. Because of the nonspecific nature of early lesions, the median duration from the onset of skin lesions to the diagnosis of MF is 4-6 years. Patch stage lesions may be pruritic or asymptomatic. Commonly, they present in non–sun-exposed areas, such as the buttocks. Annular, infiltrated, red-brown or violaceous plaques can develop, which represent malignant T-cell infiltration. Many patients never progress past the plaque stage. Tumor stage MF is more aggressive, with nodules that may undergo necrosis and ulceration.

The leukemic form of MF is Sézary syndrome. Patients present with pruritic erythroderma and lymphadenopathy. Nail dystrophy, scaling of palms and soles, and alopecia may be present. A peripheral blood smear reveals Sézary cells, which are large, hyperconvoluted lymphocytes. The count of Sézary cells is usually greater than 1000 cells/mm3.

Histology of early lesions may not be diagnostic for CTCL. Often, biopsies will be read as eczematous or psoriasiform for years before the diagnosis of MF is made. Classically, epidermotropism (single-cell exocytosis of lymphocytes into the epidermis) is present. Advanced stages may show a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes in the dermis. Groups of lymphocytes in the epidermis form Pautrier’s microabscesses. Mycosis cells may exhibit cerebriform nuclei. Neoplastic cells in MF are CD3+, CD4+, CD45RO+, CD8–. Tissue can be sent for T-cell gene rearrangement polymerase chain reaction. The presence of monoclonal T-cell gene receptor rearrangements can aid in the diagnosis of MF.

Treatment includes topical steroids, mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard) or bexarotene gel, PUVA therapy, and narrow-band UVB light for limited and/or patch disease. Localized radiotherapy can be used for more resistant lesions. Topical therapies are preferred in the early stages in MF. Systemic treatments for patients who do not respond to local therapy, or in more advanced disease include methotrexate, interferon-alpha, oral bexarotene, denileukin diftitox, and combination chemotherapy. Photopheresis is reserved for erythrodermic disease.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

What is your diagnosis?

Laboratory work revealed a normal CBC and differential, an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and sedimentation rate (ESR), negative antistreptolysin O (ASO) titers, negative pregnancy test, a normal urinalysis, and negative blood, throat, and urine cultures. A chest x-ray also was negative as well as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels. Tuberculosis interferon-gamma release essay was negative.

The patient was diagnosed with erythema nodosum (EN), based on physical exam and history of the lesions. In her particular case, infectious causes including streptococcus infection, tuberculosis, and coccidioidomycosis were ruled out. There were no x-ray findings that suggested sarcoidosis and her ACE level was within normal limits. The pregnancy test also was negative. Given her recent start on OCs, this was thought to be the cause of the lesions.

She was treated with elevation, compression stockings, and NSAIDs and discontinuation of OCs. The lesions resolved after 6 weeks leaving bruiselike patches (erythema contusiformis).

EN is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, causing inflammation on the fat (panniculitis) most commonly on the shins, but it can also occur on the arms, face, neck, and thighs. It is the most common type of panniculitis and is usually seen more often in women from the second to fourth decade of life. Erythematous tender nodules in crops commonly located on the shins are the characteristic physical finding. Systemic symptoms can occur including fever, malaise, and joint pain. The lesions usually last up to 6-8 weeks and may leave bruiselike patches or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that can take months to improve.1

The diagnosis of EN usually is made by physical examination and natural history. In unusual severe cases or lesions in atypical locations, a skin biopsy is indicated. Histologic examination of one of the lesions reveals a septal panniculitis without vasculitis. Miescher’s radial granulomas (grouped macrophages around neutrophils or septa-like spaces) often are present and are a characteristic feature of EN.

EN can be triggered by different types of infections such as streptococcus, mycoplasma, tuberculosis, or bacterial gastroenteritis; medications such as OCs, sulfonamides, iodides, penicillin, or bromides; medical conditions that include inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, or sarcoidosis; or neutrophilic dermatosis and malignancy such as leukemia and Hodgkin disease.2,3 A third of the cases are idiopathic. In children, streptococcal infections are responsible for most cases of EN.4

Recommended work-up to investigate possible triggers includes a CBC with differential, sedimentation rate, CRP, ASO titers or anti-DNase B titers, tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma TB test and a chest X ray. If there are any other symptoms, physical signs, or risk factors are present for the other not so common causes, further ancillary testing may be warranted.

Erythematous nodules and papules on the shin in children are commonly caused by arthropod bites also known as papular urticaria. These lesions are pruritic rather than tender and usually respond to topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. Subcutaneous bacterial, fungal, or atypical mycobacterial infections can present with tender nodules that can ulcerate and drain on the shins, feet, or any other body part. These patients may have a history of immunodeficiency and usually systemic symptoms of infection are present. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) also can present with tender nodules on the legs but these lesions usually necrose and ulcerate and may be associated with livedo racemosa, a transient or persistent, blotchy, reddish-blue to purple, netlike cyanotic pattern. On pathology, PAN presents with necrotizing medium vessel vasculitis. Malignant nodules also can occur on the shin. Pathology will show atypical cells. Other forms of panniculitis, such as erythema induratum and pancreatic panniculitis, can present with tender nodules but these lesions usually occur on the calves and ulcerate.

Management of EN starts with treating the underlying infection or stopping the causative medication. Initial measures include bed rest, leg elevation, compression bandages, and NSAIDs. Potassium iodide is a very effective therapy as it may control the symptoms within 24 hours. When there is no response to the above, or the patient has severe symptoms, a short course of systemic glucocorticoids can be started. Other medications for recalcitrant or recurrent lesions include colchicine, dapsone, or hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Panniculitis, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, p. 1641).

2. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Mar;43(3):584-92.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Sep 1;25(25):4011-2.

4. Turk J Pediatr. 2014 Mar-Apr;56(2):144-9.

Laboratory work revealed a normal CBC and differential, an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and sedimentation rate (ESR), negative antistreptolysin O (ASO) titers, negative pregnancy test, a normal urinalysis, and negative blood, throat, and urine cultures. A chest x-ray also was negative as well as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels. Tuberculosis interferon-gamma release essay was negative.

The patient was diagnosed with erythema nodosum (EN), based on physical exam and history of the lesions. In her particular case, infectious causes including streptococcus infection, tuberculosis, and coccidioidomycosis were ruled out. There were no x-ray findings that suggested sarcoidosis and her ACE level was within normal limits. The pregnancy test also was negative. Given her recent start on OCs, this was thought to be the cause of the lesions.

She was treated with elevation, compression stockings, and NSAIDs and discontinuation of OCs. The lesions resolved after 6 weeks leaving bruiselike patches (erythema contusiformis).

EN is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, causing inflammation on the fat (panniculitis) most commonly on the shins, but it can also occur on the arms, face, neck, and thighs. It is the most common type of panniculitis and is usually seen more often in women from the second to fourth decade of life. Erythematous tender nodules in crops commonly located on the shins are the characteristic physical finding. Systemic symptoms can occur including fever, malaise, and joint pain. The lesions usually last up to 6-8 weeks and may leave bruiselike patches or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that can take months to improve.1

The diagnosis of EN usually is made by physical examination and natural history. In unusual severe cases or lesions in atypical locations, a skin biopsy is indicated. Histologic examination of one of the lesions reveals a septal panniculitis without vasculitis. Miescher’s radial granulomas (grouped macrophages around neutrophils or septa-like spaces) often are present and are a characteristic feature of EN.

EN can be triggered by different types of infections such as streptococcus, mycoplasma, tuberculosis, or bacterial gastroenteritis; medications such as OCs, sulfonamides, iodides, penicillin, or bromides; medical conditions that include inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, or sarcoidosis; or neutrophilic dermatosis and malignancy such as leukemia and Hodgkin disease.2,3 A third of the cases are idiopathic. In children, streptococcal infections are responsible for most cases of EN.4

Recommended work-up to investigate possible triggers includes a CBC with differential, sedimentation rate, CRP, ASO titers or anti-DNase B titers, tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma TB test and a chest X ray. If there are any other symptoms, physical signs, or risk factors are present for the other not so common causes, further ancillary testing may be warranted.

Erythematous nodules and papules on the shin in children are commonly caused by arthropod bites also known as papular urticaria. These lesions are pruritic rather than tender and usually respond to topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. Subcutaneous bacterial, fungal, or atypical mycobacterial infections can present with tender nodules that can ulcerate and drain on the shins, feet, or any other body part. These patients may have a history of immunodeficiency and usually systemic symptoms of infection are present. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) also can present with tender nodules on the legs but these lesions usually necrose and ulcerate and may be associated with livedo racemosa, a transient or persistent, blotchy, reddish-blue to purple, netlike cyanotic pattern. On pathology, PAN presents with necrotizing medium vessel vasculitis. Malignant nodules also can occur on the shin. Pathology will show atypical cells. Other forms of panniculitis, such as erythema induratum and pancreatic panniculitis, can present with tender nodules but these lesions usually occur on the calves and ulcerate.

Management of EN starts with treating the underlying infection or stopping the causative medication. Initial measures include bed rest, leg elevation, compression bandages, and NSAIDs. Potassium iodide is a very effective therapy as it may control the symptoms within 24 hours. When there is no response to the above, or the patient has severe symptoms, a short course of systemic glucocorticoids can be started. Other medications for recalcitrant or recurrent lesions include colchicine, dapsone, or hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Panniculitis, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, p. 1641).

2. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Mar;43(3):584-92.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Sep 1;25(25):4011-2.

4. Turk J Pediatr. 2014 Mar-Apr;56(2):144-9.

Laboratory work revealed a normal CBC and differential, an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and sedimentation rate (ESR), negative antistreptolysin O (ASO) titers, negative pregnancy test, a normal urinalysis, and negative blood, throat, and urine cultures. A chest x-ray also was negative as well as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels. Tuberculosis interferon-gamma release essay was negative.

The patient was diagnosed with erythema nodosum (EN), based on physical exam and history of the lesions. In her particular case, infectious causes including streptococcus infection, tuberculosis, and coccidioidomycosis were ruled out. There were no x-ray findings that suggested sarcoidosis and her ACE level was within normal limits. The pregnancy test also was negative. Given her recent start on OCs, this was thought to be the cause of the lesions.

She was treated with elevation, compression stockings, and NSAIDs and discontinuation of OCs. The lesions resolved after 6 weeks leaving bruiselike patches (erythema contusiformis).

EN is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, causing inflammation on the fat (panniculitis) most commonly on the shins, but it can also occur on the arms, face, neck, and thighs. It is the most common type of panniculitis and is usually seen more often in women from the second to fourth decade of life. Erythematous tender nodules in crops commonly located on the shins are the characteristic physical finding. Systemic symptoms can occur including fever, malaise, and joint pain. The lesions usually last up to 6-8 weeks and may leave bruiselike patches or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that can take months to improve.1

The diagnosis of EN usually is made by physical examination and natural history. In unusual severe cases or lesions in atypical locations, a skin biopsy is indicated. Histologic examination of one of the lesions reveals a septal panniculitis without vasculitis. Miescher’s radial granulomas (grouped macrophages around neutrophils or septa-like spaces) often are present and are a characteristic feature of EN.

EN can be triggered by different types of infections such as streptococcus, mycoplasma, tuberculosis, or bacterial gastroenteritis; medications such as OCs, sulfonamides, iodides, penicillin, or bromides; medical conditions that include inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, or sarcoidosis; or neutrophilic dermatosis and malignancy such as leukemia and Hodgkin disease.2,3 A third of the cases are idiopathic. In children, streptococcal infections are responsible for most cases of EN.4

Recommended work-up to investigate possible triggers includes a CBC with differential, sedimentation rate, CRP, ASO titers or anti-DNase B titers, tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma TB test and a chest X ray. If there are any other symptoms, physical signs, or risk factors are present for the other not so common causes, further ancillary testing may be warranted.

Erythematous nodules and papules on the shin in children are commonly caused by arthropod bites also known as papular urticaria. These lesions are pruritic rather than tender and usually respond to topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. Subcutaneous bacterial, fungal, or atypical mycobacterial infections can present with tender nodules that can ulcerate and drain on the shins, feet, or any other body part. These patients may have a history of immunodeficiency and usually systemic symptoms of infection are present. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) also can present with tender nodules on the legs but these lesions usually necrose and ulcerate and may be associated with livedo racemosa, a transient or persistent, blotchy, reddish-blue to purple, netlike cyanotic pattern. On pathology, PAN presents with necrotizing medium vessel vasculitis. Malignant nodules also can occur on the shin. Pathology will show atypical cells. Other forms of panniculitis, such as erythema induratum and pancreatic panniculitis, can present with tender nodules but these lesions usually occur on the calves and ulcerate.

Management of EN starts with treating the underlying infection or stopping the causative medication. Initial measures include bed rest, leg elevation, compression bandages, and NSAIDs. Potassium iodide is a very effective therapy as it may control the symptoms within 24 hours. When there is no response to the above, or the patient has severe symptoms, a short course of systemic glucocorticoids can be started. Other medications for recalcitrant or recurrent lesions include colchicine, dapsone, or hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Panniculitis, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, p. 1641).

2. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Mar;43(3):584-92.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Sep 1;25(25):4011-2.

4. Turk J Pediatr. 2014 Mar-Apr;56(2):144-9.

A 16-year-old female came to the dermatology clinic for acne follow-up. She reported some improvement on her acne since she started taking OCs. She also had been using benzoyl peroxide and tretinoin on her face. In addition to the acne, she also wanted us to check some tender bumps she had been getting on her shins after she came back from a camping trip. Initially she thought they were bug bites, but the lesions were getting larger, more tender, and not improving with diphenhydramine.

The physical exam did not reveal acute distress. She was afebrile. On skin examination, she had comedones, papules and scars on her face, chest, and back. On her shins there were several erythematous tender nodules and plaques. There was no edema on her legs and pulses were present.

Make The Diagnosis - August 2018

respectively, of pityriasis lichenoides, an uncommon clonal T-cell disorder. The cause is unknown, although associations with infections have been reported. Pityriasis lichenoides more commonly affects children or young adults, usually before age 30 years. The disease can occur in all races.

In PLEVA, erythematous to brown papules and macules, in various stages of evolution, appear suddenly and in crops. The trunk and flexural areas are most often affected, but lesions may become widespread and may be pruritic or painful. Lesions may crust, ulcerate, or become necrotic and can heal with scarring. In general, patients don’t have constitutional symptoms. Lesions tend to resolve spontaneously over 1-3 years.

Rarely, PLEVA may develop into a more severe form called febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, a dermatologic emergency. Patients (more commonly, young males) may present with high fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Lesions become very painful, ulcerated, and necrotic, and extensive necrosis may be present. Changes in mental status, breathing difficulties, anemia, arthritis, abdominal pain, and sepsis may occur. Patients require hospitalization. There is a 25% mortality rate.

PLC is at the other end of this disease spectrum, representing the chronic, more mild stage of the disorder. Lesions present as indolent, asymptomatic, scaly macules and erythematous papules, favoring the trunk and proximal extremities. Lesions tend to be fewer in number than seen in PLEVA. They resolve over several months and may result in hypopigmentation, but usually don’t cause scarring. Patients may have long periods of remission between outbreaks. T-cell gene rearrangement may demonstrate monoclonality. PLC is generally considered a benign disease, although there are patients who have developed cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. For this reason, patients should be followed carefully for signs of malignant transformation.

Both forms share a common histologic picture. In PLEVA, focal parakeratosis and crusting is present. A dense, wedge-shaped infiltrate can be seen with prominent lymphocytic exocystosis in the epidermis. Necrotic keratinocytes are often seen. There may be spongiosis and intraepidermal vesicles. Extravasation of erythrocytes often occurs in the epidermis. PLC is histologically similar but far more subtle. There is less crusting, less spongiosis, fewer vesicles, and fewer necrotic keratinocytes. Generally, atypia of lymphocytes is absent.

Mucha-Habermann requires treatment with systemic steroids. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, or dapsone may be used as steroid-sparing agents. Upon treatment, lesions may resolve or revert back to more typical lesions of PLEVA. Treatment for PLEVA and PLC includes oral tetracycline or erythromycin, antihistamines (if pruritus is present), topical steroids, topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, or phototherapy. Low-dose weekly methotrexate may be helpful.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

respectively, of pityriasis lichenoides, an uncommon clonal T-cell disorder. The cause is unknown, although associations with infections have been reported. Pityriasis lichenoides more commonly affects children or young adults, usually before age 30 years. The disease can occur in all races.

In PLEVA, erythematous to brown papules and macules, in various stages of evolution, appear suddenly and in crops. The trunk and flexural areas are most often affected, but lesions may become widespread and may be pruritic or painful. Lesions may crust, ulcerate, or become necrotic and can heal with scarring. In general, patients don’t have constitutional symptoms. Lesions tend to resolve spontaneously over 1-3 years.

Rarely, PLEVA may develop into a more severe form called febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, a dermatologic emergency. Patients (more commonly, young males) may present with high fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Lesions become very painful, ulcerated, and necrotic, and extensive necrosis may be present. Changes in mental status, breathing difficulties, anemia, arthritis, abdominal pain, and sepsis may occur. Patients require hospitalization. There is a 25% mortality rate.

PLC is at the other end of this disease spectrum, representing the chronic, more mild stage of the disorder. Lesions present as indolent, asymptomatic, scaly macules and erythematous papules, favoring the trunk and proximal extremities. Lesions tend to be fewer in number than seen in PLEVA. They resolve over several months and may result in hypopigmentation, but usually don’t cause scarring. Patients may have long periods of remission between outbreaks. T-cell gene rearrangement may demonstrate monoclonality. PLC is generally considered a benign disease, although there are patients who have developed cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. For this reason, patients should be followed carefully for signs of malignant transformation.

Both forms share a common histologic picture. In PLEVA, focal parakeratosis and crusting is present. A dense, wedge-shaped infiltrate can be seen with prominent lymphocytic exocystosis in the epidermis. Necrotic keratinocytes are often seen. There may be spongiosis and intraepidermal vesicles. Extravasation of erythrocytes often occurs in the epidermis. PLC is histologically similar but far more subtle. There is less crusting, less spongiosis, fewer vesicles, and fewer necrotic keratinocytes. Generally, atypia of lymphocytes is absent.

Mucha-Habermann requires treatment with systemic steroids. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, or dapsone may be used as steroid-sparing agents. Upon treatment, lesions may resolve or revert back to more typical lesions of PLEVA. Treatment for PLEVA and PLC includes oral tetracycline or erythromycin, antihistamines (if pruritus is present), topical steroids, topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, or phototherapy. Low-dose weekly methotrexate may be helpful.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

respectively, of pityriasis lichenoides, an uncommon clonal T-cell disorder. The cause is unknown, although associations with infections have been reported. Pityriasis lichenoides more commonly affects children or young adults, usually before age 30 years. The disease can occur in all races.

In PLEVA, erythematous to brown papules and macules, in various stages of evolution, appear suddenly and in crops. The trunk and flexural areas are most often affected, but lesions may become widespread and may be pruritic or painful. Lesions may crust, ulcerate, or become necrotic and can heal with scarring. In general, patients don’t have constitutional symptoms. Lesions tend to resolve spontaneously over 1-3 years.

Rarely, PLEVA may develop into a more severe form called febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, a dermatologic emergency. Patients (more commonly, young males) may present with high fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Lesions become very painful, ulcerated, and necrotic, and extensive necrosis may be present. Changes in mental status, breathing difficulties, anemia, arthritis, abdominal pain, and sepsis may occur. Patients require hospitalization. There is a 25% mortality rate.

PLC is at the other end of this disease spectrum, representing the chronic, more mild stage of the disorder. Lesions present as indolent, asymptomatic, scaly macules and erythematous papules, favoring the trunk and proximal extremities. Lesions tend to be fewer in number than seen in PLEVA. They resolve over several months and may result in hypopigmentation, but usually don’t cause scarring. Patients may have long periods of remission between outbreaks. T-cell gene rearrangement may demonstrate monoclonality. PLC is generally considered a benign disease, although there are patients who have developed cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. For this reason, patients should be followed carefully for signs of malignant transformation.

Both forms share a common histologic picture. In PLEVA, focal parakeratosis and crusting is present. A dense, wedge-shaped infiltrate can be seen with prominent lymphocytic exocystosis in the epidermis. Necrotic keratinocytes are often seen. There may be spongiosis and intraepidermal vesicles. Extravasation of erythrocytes often occurs in the epidermis. PLC is histologically similar but far more subtle. There is less crusting, less spongiosis, fewer vesicles, and fewer necrotic keratinocytes. Generally, atypia of lymphocytes is absent.

Mucha-Habermann requires treatment with systemic steroids. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, or dapsone may be used as steroid-sparing agents. Upon treatment, lesions may resolve or revert back to more typical lesions of PLEVA. Treatment for PLEVA and PLC includes oral tetracycline or erythromycin, antihistamines (if pruritus is present), topical steroids, topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, or phototherapy. Low-dose weekly methotrexate may be helpful.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 28-year-old white female with no significant past medical history presents with a 10-year history of asymptomatic erythematous papules and scaly patches that come and go. She has used topical steroids in the past.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - July 2018

Frequently misdiagnosed, streptococcal intertrigo more commonly affects infants and toddlers but is rarely reported, especially compared with other Streptococcus pyogenes infections, including impetigo, erysipelas, and cellulitis.1

Intertrigo, meaning “between” (inter) and “to rub” (terere) in Latin, describes any skin disorder involving two opposing skin surfaces that touch or rub to cause friction.2 The continuous chaffing, coupled with moisture trapped within the skin folds, leads to irritation and maceration, which provides an ideal environment for pathogens to thrive. Thus, frictional dermatitides that arise may become secondarily infected with one or more microorganisms, such as Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and even organisms less commonly associated with cutaneous infection, such as Proteus mirabilis.3

Streptococcal intertrigo may affect any intertriginous area, but most commonly it affects the folds of the neck; this is likely because of the combination of the deep folds that develop in shorter, infantile necks and the moisture from drool and saliva that pools in the area.5,6 In addition to these cervical folds, other intertriginous areas commonly are affected, including the inguinal, axillary, popliteal, posterior auricular, perianal, and genital folds.

Perianal streptococcal disease may present in a similar manner as streptococcal intertrigo, manifesting as well-demarcated, beefy red plaques in the skin folds around the anus and, in females, frequently perivaginally.7 Unlike streptococcal intertrigo, perianal streptococcal disease is often characterized by pain, pruritus, and fissuring of the involved area.8 It is associated with pharyngeal colonization of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.7

Diagnosis is straight forward and may be confirmed by a positive streptococcal rapid antigen test of swab specimens of one or more surfaces of affected skin or by culture from a skin swab yielding growth of the organism.1,5 Skin biopsy is not necessary. If the index of suspicion for candida is high, a potassium hydroxide preparation and culture may be performed. Checking serum anti-DNase B antibodies, antistreptolysin O, and pharyngeal cultures is often unrevealing.9 A urinalysis may be performed to assess for poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis if the patient later develops facial or orbital edema, hypertension, hematuria, or lethargy.9

Treatment consists of systemic antistreptococcal therapy; oral amoxicillin and penicillin frequently have been used.9 Moisture in the area should be reduced with application of absorptive powders and physical barriers, such as zinc oxide, after gentle cleansing of the area.5

Other diagnoses to consider when evaluating dermatitides affecting skin folds include: other infectious causes, which may be ruled out by fungal or bacterial culture; inverse psoriasis, which will frequently demonstrate scale; atopic dermatitis, which will be pruritic with history of atopy; irritant or contact dermatitis, which will often have correlating clinical history; seborrheic dermatitis, which will often involve greasiness and scale; and less commonly, acrodermatitis enteropathica, which will be accompanied by diarrhea and hair loss.2,9 Scabies also may be on the differential if the patient endorses severe pruritus with close contacts with similar symptoms.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the university. They had no conflicts of interest or disclosures to report.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;31(2):e71-2.

2. Clin Dermatol. 2011 Mar-Apr;29(2):173-9.

3. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec;112(6 pt 1):1427-9.

4. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Mar 20. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224179.

5. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 Aug;31(8):872-3.

6. J Pediatr. 2015 May;166(5):1318.

7. J Pediatr. 2015 Sep;167(3):687-93.e1-2.

8. Pediatrics in Review. 1991;12(8):248-55.

9. J Pediatr. 2017 May;184:230-1.e1.

Frequently misdiagnosed, streptococcal intertrigo more commonly affects infants and toddlers but is rarely reported, especially compared with other Streptococcus pyogenes infections, including impetigo, erysipelas, and cellulitis.1

Intertrigo, meaning “between” (inter) and “to rub” (terere) in Latin, describes any skin disorder involving two opposing skin surfaces that touch or rub to cause friction.2 The continuous chaffing, coupled with moisture trapped within the skin folds, leads to irritation and maceration, which provides an ideal environment for pathogens to thrive. Thus, frictional dermatitides that arise may become secondarily infected with one or more microorganisms, such as Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and even organisms less commonly associated with cutaneous infection, such as Proteus mirabilis.3

Streptococcal intertrigo may affect any intertriginous area, but most commonly it affects the folds of the neck; this is likely because of the combination of the deep folds that develop in shorter, infantile necks and the moisture from drool and saliva that pools in the area.5,6 In addition to these cervical folds, other intertriginous areas commonly are affected, including the inguinal, axillary, popliteal, posterior auricular, perianal, and genital folds.

Perianal streptococcal disease may present in a similar manner as streptococcal intertrigo, manifesting as well-demarcated, beefy red plaques in the skin folds around the anus and, in females, frequently perivaginally.7 Unlike streptococcal intertrigo, perianal streptococcal disease is often characterized by pain, pruritus, and fissuring of the involved area.8 It is associated with pharyngeal colonization of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.7

Diagnosis is straight forward and may be confirmed by a positive streptococcal rapid antigen test of swab specimens of one or more surfaces of affected skin or by culture from a skin swab yielding growth of the organism.1,5 Skin biopsy is not necessary. If the index of suspicion for candida is high, a potassium hydroxide preparation and culture may be performed. Checking serum anti-DNase B antibodies, antistreptolysin O, and pharyngeal cultures is often unrevealing.9 A urinalysis may be performed to assess for poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis if the patient later develops facial or orbital edema, hypertension, hematuria, or lethargy.9

Treatment consists of systemic antistreptococcal therapy; oral amoxicillin and penicillin frequently have been used.9 Moisture in the area should be reduced with application of absorptive powders and physical barriers, such as zinc oxide, after gentle cleansing of the area.5

Other diagnoses to consider when evaluating dermatitides affecting skin folds include: other infectious causes, which may be ruled out by fungal or bacterial culture; inverse psoriasis, which will frequently demonstrate scale; atopic dermatitis, which will be pruritic with history of atopy; irritant or contact dermatitis, which will often have correlating clinical history; seborrheic dermatitis, which will often involve greasiness and scale; and less commonly, acrodermatitis enteropathica, which will be accompanied by diarrhea and hair loss.2,9 Scabies also may be on the differential if the patient endorses severe pruritus with close contacts with similar symptoms.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the university. They had no conflicts of interest or disclosures to report.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;31(2):e71-2.

2. Clin Dermatol. 2011 Mar-Apr;29(2):173-9.

3. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec;112(6 pt 1):1427-9.

4. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Mar 20. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224179.

5. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 Aug;31(8):872-3.

6. J Pediatr. 2015 May;166(5):1318.

7. J Pediatr. 2015 Sep;167(3):687-93.e1-2.

8. Pediatrics in Review. 1991;12(8):248-55.

9. J Pediatr. 2017 May;184:230-1.e1.

Frequently misdiagnosed, streptococcal intertrigo more commonly affects infants and toddlers but is rarely reported, especially compared with other Streptococcus pyogenes infections, including impetigo, erysipelas, and cellulitis.1

Intertrigo, meaning “between” (inter) and “to rub” (terere) in Latin, describes any skin disorder involving two opposing skin surfaces that touch or rub to cause friction.2 The continuous chaffing, coupled with moisture trapped within the skin folds, leads to irritation and maceration, which provides an ideal environment for pathogens to thrive. Thus, frictional dermatitides that arise may become secondarily infected with one or more microorganisms, such as Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and even organisms less commonly associated with cutaneous infection, such as Proteus mirabilis.3

Streptococcal intertrigo may affect any intertriginous area, but most commonly it affects the folds of the neck; this is likely because of the combination of the deep folds that develop in shorter, infantile necks and the moisture from drool and saliva that pools in the area.5,6 In addition to these cervical folds, other intertriginous areas commonly are affected, including the inguinal, axillary, popliteal, posterior auricular, perianal, and genital folds.

Perianal streptococcal disease may present in a similar manner as streptococcal intertrigo, manifesting as well-demarcated, beefy red plaques in the skin folds around the anus and, in females, frequently perivaginally.7 Unlike streptococcal intertrigo, perianal streptococcal disease is often characterized by pain, pruritus, and fissuring of the involved area.8 It is associated with pharyngeal colonization of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.7

Diagnosis is straight forward and may be confirmed by a positive streptococcal rapid antigen test of swab specimens of one or more surfaces of affected skin or by culture from a skin swab yielding growth of the organism.1,5 Skin biopsy is not necessary. If the index of suspicion for candida is high, a potassium hydroxide preparation and culture may be performed. Checking serum anti-DNase B antibodies, antistreptolysin O, and pharyngeal cultures is often unrevealing.9 A urinalysis may be performed to assess for poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis if the patient later develops facial or orbital edema, hypertension, hematuria, or lethargy.9

Treatment consists of systemic antistreptococcal therapy; oral amoxicillin and penicillin frequently have been used.9 Moisture in the area should be reduced with application of absorptive powders and physical barriers, such as zinc oxide, after gentle cleansing of the area.5

Other diagnoses to consider when evaluating dermatitides affecting skin folds include: other infectious causes, which may be ruled out by fungal or bacterial culture; inverse psoriasis, which will frequently demonstrate scale; atopic dermatitis, which will be pruritic with history of atopy; irritant or contact dermatitis, which will often have correlating clinical history; seborrheic dermatitis, which will often involve greasiness and scale; and less commonly, acrodermatitis enteropathica, which will be accompanied by diarrhea and hair loss.2,9 Scabies also may be on the differential if the patient endorses severe pruritus with close contacts with similar symptoms.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the university. They had no conflicts of interest or disclosures to report.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;31(2):e71-2.

2. Clin Dermatol. 2011 Mar-Apr;29(2):173-9.

3. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec;112(6 pt 1):1427-9.

4. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Mar 20. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224179.

5. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 Aug;31(8):872-3.

6. J Pediatr. 2015 May;166(5):1318.

7. J Pediatr. 2015 Sep;167(3):687-93.e1-2.

8. Pediatrics in Review. 1991;12(8):248-55.

9. J Pediatr. 2017 May;184:230-1.e1.

An 8-week-old male with a history of cradle cap presented for a second evaluation of an erythematous rash on the neck that started 1.5 weeks before, and it had since worsened. The parents note that their infant has been more irritable, but they otherwise deny any fever, diarrhea, constipation, or decrease in oral intake.

The patient’s first evaluation had been 3 days prior; nystatin cream was prescribed, and the parents applied it twice a day but without improvement to the rash. The patient also had a rash behind the ears bilaterally, which was treated with hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment with some improvement

On physical exam, the central neck is covered by a bright, beefy red, erythematous plaque with distinct borders and strong odor. There is faint scale and superficial desquamation between the skin folds. There are no surrounding papules or pustules. The patient’s chin is moist with drool. In the postauricular skin folds bilaterally, there are fainter but still erythematous plaques with mild scale.

Make the Diagnosis - June 2018

Different types of steatocystoma multiplex have been described: localized, generalized, facial, acral, and suppurative (in which the lesions resemble hidradenitis suppurativa).

This condition is autosomal dominant and is linked to defects in KRT17 gene, which instructs the production of keratin 17. However, some cases of steatocystoma multiplex occur sporadically with no mutation in the KRT17 gene; in them, the cause is unknown. Steatocystoma multiplex may be associated with eruptive vellus hair cysts and pachyonychia congenita (nail and teeth abnormalities and palmoplantar keratoderma). Lesions often appear during adolescence, when an individual hits puberty. Hormones likely influence the development of the cysts from the pilosebaceous unit. If there is a single steatocystoma, it is called steatocystoma simplex.

Steatocystomas do not resolve on their own. The small, benign cysts are located fairly superficial in the dermis. If punctured, they drain a yellow, oily liquid sebum. Lesions may become inflamed and may heal with scarring, as in acne. They may be treated by incision and drainage or excision to remove the cyst wall. Electrosurgery and cryotherapy may be used. Oral antibiotics may improve inflamed lesions. There are reports in the literature in which isotretinoin has helped; however, it is not curative. In some cases, the lesions can reoccur and may even be worse.

Case and photo submitted by: Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD; Aventura, Fla.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Different types of steatocystoma multiplex have been described: localized, generalized, facial, acral, and suppurative (in which the lesions resemble hidradenitis suppurativa).

This condition is autosomal dominant and is linked to defects in KRT17 gene, which instructs the production of keratin 17. However, some cases of steatocystoma multiplex occur sporadically with no mutation in the KRT17 gene; in them, the cause is unknown. Steatocystoma multiplex may be associated with eruptive vellus hair cysts and pachyonychia congenita (nail and teeth abnormalities and palmoplantar keratoderma). Lesions often appear during adolescence, when an individual hits puberty. Hormones likely influence the development of the cysts from the pilosebaceous unit. If there is a single steatocystoma, it is called steatocystoma simplex.

Steatocystomas do not resolve on their own. The small, benign cysts are located fairly superficial in the dermis. If punctured, they drain a yellow, oily liquid sebum. Lesions may become inflamed and may heal with scarring, as in acne. They may be treated by incision and drainage or excision to remove the cyst wall. Electrosurgery and cryotherapy may be used. Oral antibiotics may improve inflamed lesions. There are reports in the literature in which isotretinoin has helped; however, it is not curative. In some cases, the lesions can reoccur and may even be worse.

Case and photo submitted by: Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD; Aventura, Fla.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Different types of steatocystoma multiplex have been described: localized, generalized, facial, acral, and suppurative (in which the lesions resemble hidradenitis suppurativa).

This condition is autosomal dominant and is linked to defects in KRT17 gene, which instructs the production of keratin 17. However, some cases of steatocystoma multiplex occur sporadically with no mutation in the KRT17 gene; in them, the cause is unknown. Steatocystoma multiplex may be associated with eruptive vellus hair cysts and pachyonychia congenita (nail and teeth abnormalities and palmoplantar keratoderma). Lesions often appear during adolescence, when an individual hits puberty. Hormones likely influence the development of the cysts from the pilosebaceous unit. If there is a single steatocystoma, it is called steatocystoma simplex.

Steatocystomas do not resolve on their own. The small, benign cysts are located fairly superficial in the dermis. If punctured, they drain a yellow, oily liquid sebum. Lesions may become inflamed and may heal with scarring, as in acne. They may be treated by incision and drainage or excision to remove the cyst wall. Electrosurgery and cryotherapy may be used. Oral antibiotics may improve inflamed lesions. There are reports in the literature in which isotretinoin has helped; however, it is not curative. In some cases, the lesions can reoccur and may even be worse.

Case and photo submitted by: Donna Bilu Martin, MD; Premier Dermatology, MD; Aventura, Fla.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Make the Diagnosis - May 2018

and through close skin contact, as well as contaminated clothes and bedding. Adult lice can live up to 36 hours away from its host. Pubic areas most commonly are affected, although other hair-bearing parts of the body often are affected, including eyelashes.

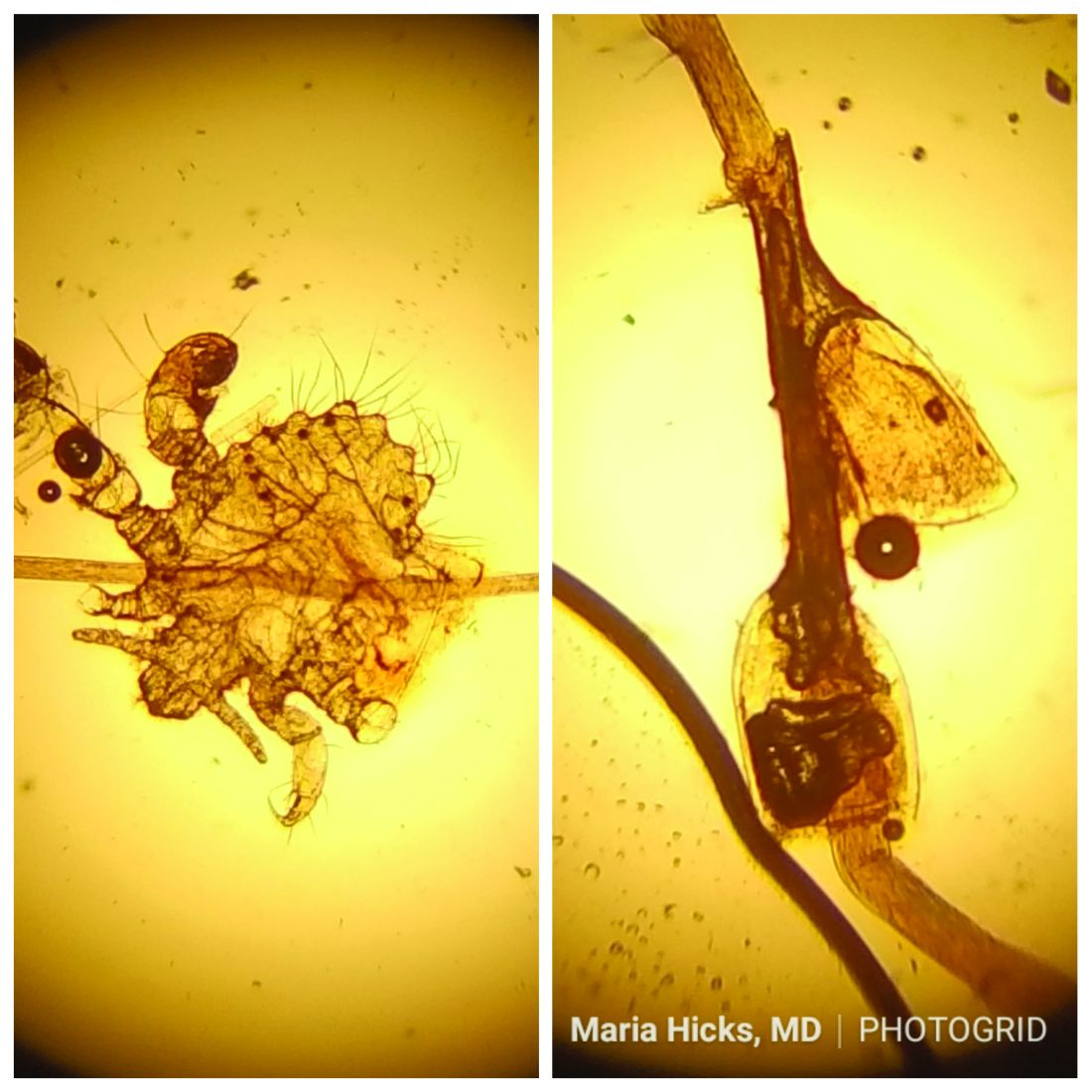

Pruritus can be severe. Secondary bacterial infections may occur as maculae ceruleae, or blue-colored macules, on the skin. The lice are visible to the naked eye and are approximately 1 mm in length. They have a crablike appearance, six legs, and a wide body. Nits may be present on the hair shaft. Unlike hair casts, which can be moved up and down along the hair shaft, nits firmly adhere to the hair. Diagnosis should prompt a workup for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

Treatment for patients and their sexual partners include permethrin topically; and laundering of clothing and bedding. Lice on the eyelashes can be treated with 8 days of twice-daily applications of petrolatum. Ivermectin can be used when topical therapy fails, although this is an off-label treatment (not approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Pediculosis corporis – body lice or clothing lice – is also known as “vagabond’s disease” and is caused by Pediculus humanus var corporis. Body lice lay their eggs in clothing seams and can live in clothing for up to 1 month without feeding on human blood. Often homeless individuals and those living in overcrowded areas can be affected. The louse and nits also are visible to the naked eye. They have a longer, narrower body than Phthirus pubis and are more similar in appearance to head lice. They rarely are found on the skin.

Body lice may carry disease such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever or endocarditis. Permethrin is the most widely used treatment to kill both lice and ova. Other treatments include Malathion, Lindane, and Crotamiton. Clothing and bedding should be laundered.

Scabies is a mite infestation caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Unlike lice, scabies often affects the hands and feet. Characteristic linear burrows may be seen in the finger web spaces. The circle of Hebra describes the areas commonly infected by mites: axillae, antecubital fossa, wrists, hands, and the groin. Pruritus may be severe and worse at night. Patients may be afflicted with both lice and scabies at the same time. Mites are not visible to the naked eye but can be seen microscopically. Topical permethrin cream is used most often for treatment. All household contacts should be treated at the same time. As in louse infestations, clothing and bedding should be laundered. Ivermectin can be used for crusted scabies, although this is an off-label treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Maria Hicks, MD, Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, Tampa, and Dr. Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

and through close skin contact, as well as contaminated clothes and bedding. Adult lice can live up to 36 hours away from its host. Pubic areas most commonly are affected, although other hair-bearing parts of the body often are affected, including eyelashes.

Pruritus can be severe. Secondary bacterial infections may occur as maculae ceruleae, or blue-colored macules, on the skin. The lice are visible to the naked eye and are approximately 1 mm in length. They have a crablike appearance, six legs, and a wide body. Nits may be present on the hair shaft. Unlike hair casts, which can be moved up and down along the hair shaft, nits firmly adhere to the hair. Diagnosis should prompt a workup for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

Treatment for patients and their sexual partners include permethrin topically; and laundering of clothing and bedding. Lice on the eyelashes can be treated with 8 days of twice-daily applications of petrolatum. Ivermectin can be used when topical therapy fails, although this is an off-label treatment (not approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Pediculosis corporis – body lice or clothing lice – is also known as “vagabond’s disease” and is caused by Pediculus humanus var corporis. Body lice lay their eggs in clothing seams and can live in clothing for up to 1 month without feeding on human blood. Often homeless individuals and those living in overcrowded areas can be affected. The louse and nits also are visible to the naked eye. They have a longer, narrower body than Phthirus pubis and are more similar in appearance to head lice. They rarely are found on the skin.

Body lice may carry disease such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever or endocarditis. Permethrin is the most widely used treatment to kill both lice and ova. Other treatments include Malathion, Lindane, and Crotamiton. Clothing and bedding should be laundered.

Scabies is a mite infestation caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Unlike lice, scabies often affects the hands and feet. Characteristic linear burrows may be seen in the finger web spaces. The circle of Hebra describes the areas commonly infected by mites: axillae, antecubital fossa, wrists, hands, and the groin. Pruritus may be severe and worse at night. Patients may be afflicted with both lice and scabies at the same time. Mites are not visible to the naked eye but can be seen microscopically. Topical permethrin cream is used most often for treatment. All household contacts should be treated at the same time. As in louse infestations, clothing and bedding should be laundered. Ivermectin can be used for crusted scabies, although this is an off-label treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Maria Hicks, MD, Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, Tampa, and Dr. Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

and through close skin contact, as well as contaminated clothes and bedding. Adult lice can live up to 36 hours away from its host. Pubic areas most commonly are affected, although other hair-bearing parts of the body often are affected, including eyelashes.

Pruritus can be severe. Secondary bacterial infections may occur as maculae ceruleae, or blue-colored macules, on the skin. The lice are visible to the naked eye and are approximately 1 mm in length. They have a crablike appearance, six legs, and a wide body. Nits may be present on the hair shaft. Unlike hair casts, which can be moved up and down along the hair shaft, nits firmly adhere to the hair. Diagnosis should prompt a workup for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

Treatment for patients and their sexual partners include permethrin topically; and laundering of clothing and bedding. Lice on the eyelashes can be treated with 8 days of twice-daily applications of petrolatum. Ivermectin can be used when topical therapy fails, although this is an off-label treatment (not approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Pediculosis corporis – body lice or clothing lice – is also known as “vagabond’s disease” and is caused by Pediculus humanus var corporis. Body lice lay their eggs in clothing seams and can live in clothing for up to 1 month without feeding on human blood. Often homeless individuals and those living in overcrowded areas can be affected. The louse and nits also are visible to the naked eye. They have a longer, narrower body than Phthirus pubis and are more similar in appearance to head lice. They rarely are found on the skin.

Body lice may carry disease such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever or endocarditis. Permethrin is the most widely used treatment to kill both lice and ova. Other treatments include Malathion, Lindane, and Crotamiton. Clothing and bedding should be laundered.

Scabies is a mite infestation caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Unlike lice, scabies often affects the hands and feet. Characteristic linear burrows may be seen in the finger web spaces. The circle of Hebra describes the areas commonly infected by mites: axillae, antecubital fossa, wrists, hands, and the groin. Pruritus may be severe and worse at night. Patients may be afflicted with both lice and scabies at the same time. Mites are not visible to the naked eye but can be seen microscopically. Topical permethrin cream is used most often for treatment. All household contacts should be treated at the same time. As in louse infestations, clothing and bedding should be laundered. Ivermectin can be used for crusted scabies, although this is an off-label treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Maria Hicks, MD, Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, Tampa, and Dr. Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 40-year-old HIV-positive male presented with a 1-month history of severely pruritic papules on his chest. The patient reported that he "removes bugs" from his skin. Microscopic examination of a hair clipping was performed.

Make the Diagnosis:

Make the Diagnosis - May 2018

Generally, school-aged children are most often affected. Infections are more likely in late winter and early spring. The virus is spread via respiratory secretions, blood products, and transmission from mother to fetus. The cutaneous findings occur about 10 days after exposure to the virus. By that time, the risk of being contagious is low.

Healthy individuals have no sequelae from fifth disease and require no treatment. However, in patients with hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease, an aplastic crisis can be triggered. In patients with deficient immune systems, parvovirus B19 may cause infection and anemia, requiring hospitalization. Pregnant women exposed to parvovirus B19 are at risk for hydrops fetalis and rarely, fetal malformations or fetal demise. Other uncommon associations include hepatitis, vasculitides, and neurologic disease.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected]. This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Generally, school-aged children are most often affected. Infections are more likely in late winter and early spring. The virus is spread via respiratory secretions, blood products, and transmission from mother to fetus. The cutaneous findings occur about 10 days after exposure to the virus. By that time, the risk of being contagious is low.

Healthy individuals have no sequelae from fifth disease and require no treatment. However, in patients with hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease, an aplastic crisis can be triggered. In patients with deficient immune systems, parvovirus B19 may cause infection and anemia, requiring hospitalization. Pregnant women exposed to parvovirus B19 are at risk for hydrops fetalis and rarely, fetal malformations or fetal demise. Other uncommon associations include hepatitis, vasculitides, and neurologic disease.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected]. This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Generally, school-aged children are most often affected. Infections are more likely in late winter and early spring. The virus is spread via respiratory secretions, blood products, and transmission from mother to fetus. The cutaneous findings occur about 10 days after exposure to the virus. By that time, the risk of being contagious is low.

Healthy individuals have no sequelae from fifth disease and require no treatment. However, in patients with hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease, an aplastic crisis can be triggered. In patients with deficient immune systems, parvovirus B19 may cause infection and anemia, requiring hospitalization. Pregnant women exposed to parvovirus B19 are at risk for hydrops fetalis and rarely, fetal malformations or fetal demise. Other uncommon associations include hepatitis, vasculitides, and neurologic disease.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected]. This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Make The Diagnosis - April 2018

Once an individual has been exposed to varicella-zoster virus, either from primary infection (chickenpox) or vaccination, the virus remains dormant in dorsal root ganglion cells. It may become reactivated at a later time, which results in herpes zoster. Typically, immunosuppression (hematologic malignancy and HIV infection) and age are factors that play a role in reactivation, although young people may develop shingles as well. Older age increases the incidence of herpes zoster.

More than 90% of patients will experience a prodrome of pain, burning, or tingling in the dermatome prior to the development of cutaneous lesions. Occasionally, there will be no symptoms prior. Papules and plaques begin to form, which quickly develop into vesicles and blisters. After a few days, lesions become crusted. Bullae or necrosis may occur in more severe cases. Typically, the condition resolves in 2-3 weeks, but can take 6 weeks or longer in elderly patients. In zoster sine herpete, patients have pain but no skin lesions.

In typical herpes zoster, lesions can be scattered outside the dermatome as well. When more than 20 lesions are scattered outside the area of primary or adjacent dermatomes, this is defined as disseminated herpes zoster. This occurs more commonly in debilitated or immune-compromised individuals. The outlying vesicles are often singular, not grouped, and resemble the “dew drop on a rose petal” look of varicella-zoster lesions. Dissemination necessitates systemic antiviral therapy, preferably intravenous followed by oral treatment once stable. Central nervous system and pulmonary involvement can occur.

Complications of zoster can occur. Postherpetic neuralgia and pain is more common in patients over the age of 50 and may become chronic. Ramsay Hunt syndrome may result in facial paralysis and hearing loss when there is involvement of the facial or auditory nerve. Occasionally, inflammatory lesions can occur within the affected area after the infection has resolved. Secondary bacterial infection, scarring, and motor paralysis can occur.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected]. This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Once an individual has been exposed to varicella-zoster virus, either from primary infection (chickenpox) or vaccination, the virus remains dormant in dorsal root ganglion cells. It may become reactivated at a later time, which results in herpes zoster. Typically, immunosuppression (hematologic malignancy and HIV infection) and age are factors that play a role in reactivation, although young people may develop shingles as well. Older age increases the incidence of herpes zoster.

More than 90% of patients will experience a prodrome of pain, burning, or tingling in the dermatome prior to the development of cutaneous lesions. Occasionally, there will be no symptoms prior. Papules and plaques begin to form, which quickly develop into vesicles and blisters. After a few days, lesions become crusted. Bullae or necrosis may occur in more severe cases. Typically, the condition resolves in 2-3 weeks, but can take 6 weeks or longer in elderly patients. In zoster sine herpete, patients have pain but no skin lesions.