User login

RSS feeds

In my last column, I mentioned RSS news feeds as a useful, versatile online tool. As my editor later reminded me, however, it has been over a decade since I’ve discussed RSS feeds – so an update is certainly in order.

The sheer volume of information on the web makes quick and efficient searching an indispensable skill, but once you become quick and efficient at finding the information you need, a new problem arises: The information changes! All the good medical, news, and other information-based websites change and update their content on a regular but unpredictable basis. And checking each one for new information can be very tedious, if you can remember to do it at all.

Many sites offer an email service to notify you of new content, but multiple email subscriptions clutter your inbox and often can’t select out the information you’re really interested in. RSS feeds are a more efficient and increasingly popular method of staying current on all the subjects that interest you – medical and otherwise. RSS (which stands for Rich Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication, depending on whom you ask) is a file format that websites use (or a similar one called Atom) to produce a summary file, or “feed,” of new content, along with links to full versions of that content. When you subscribe to a given website’s feed, you’ll receive a summary of new content each time the website is updated.

Thousands of websites now offer RSS feeds, including most of the large medical information services, all the major news organizations, and many web logs.

To subscribe to feeds, you must download a program called a feed reader, which is basically just a browser specializing in RSS and Atom files. Dozens of readers (also known as aggregators) are available. Some can be accessed through browsers, others are integrated into email programs, and still others run as standalone applications. With the rise of cloud computing, some cloud-based services offer feed aggregation as part of their service.

Many readers are free, but those with the most advanced features usually come with a fee of some sort. (As always, I have no financial interest in any enterprise discussed in this column.) A comprehensive list of available readers can be found in the Wikipedia article “Comparison of Feed Aggregators.”

It’s not always easy to find out whether a particular website offers a feed, because there is no universally recognized method of indicating its existence. Look for a link to “RSS” or “Syndicate This,” or an orange rectangle with the letters “RSS” or “XML” (don’t ask). These links are not always on the home page. You may need to consult the site map to find a link to a page explaining available feeds and how to find them.

Some of the major sites have multiple feeds to choose from. For example, you can generate a feed of current stories related to the page that you are following on Google News by clicking the RSS link on any Google News page.

Once you know the URL of the RSS feed you want, you provide it to your reader program, which will monitor the feed for you. (Many RSS aggregators come preconfigured with a list of feed URLs for popular news websites.)

In addition to notifying you of important news headlines, changes to your favorite websites, and new developments in any medical (or other) field of interest to you, RSS feeds have many other uses. Some will notify you of new products in a store or catalog, new newsletter issues (including email newsletters), weather and other changing-condition alerts, and the addition of new items to a database – or new members to a group.

It can work the other way as well: If you want readers of your website, blog, or podcast to receive the latest news about your practice, such as new treatments and procedures you’re offering – or if you want to know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites – you can create your own RSS feed. In my next column, I’ll explain exactly how to do that.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In my last column, I mentioned RSS news feeds as a useful, versatile online tool. As my editor later reminded me, however, it has been over a decade since I’ve discussed RSS feeds – so an update is certainly in order.

The sheer volume of information on the web makes quick and efficient searching an indispensable skill, but once you become quick and efficient at finding the information you need, a new problem arises: The information changes! All the good medical, news, and other information-based websites change and update their content on a regular but unpredictable basis. And checking each one for new information can be very tedious, if you can remember to do it at all.

Many sites offer an email service to notify you of new content, but multiple email subscriptions clutter your inbox and often can’t select out the information you’re really interested in. RSS feeds are a more efficient and increasingly popular method of staying current on all the subjects that interest you – medical and otherwise. RSS (which stands for Rich Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication, depending on whom you ask) is a file format that websites use (or a similar one called Atom) to produce a summary file, or “feed,” of new content, along with links to full versions of that content. When you subscribe to a given website’s feed, you’ll receive a summary of new content each time the website is updated.

Thousands of websites now offer RSS feeds, including most of the large medical information services, all the major news organizations, and many web logs.

To subscribe to feeds, you must download a program called a feed reader, which is basically just a browser specializing in RSS and Atom files. Dozens of readers (also known as aggregators) are available. Some can be accessed through browsers, others are integrated into email programs, and still others run as standalone applications. With the rise of cloud computing, some cloud-based services offer feed aggregation as part of their service.

Many readers are free, but those with the most advanced features usually come with a fee of some sort. (As always, I have no financial interest in any enterprise discussed in this column.) A comprehensive list of available readers can be found in the Wikipedia article “Comparison of Feed Aggregators.”

It’s not always easy to find out whether a particular website offers a feed, because there is no universally recognized method of indicating its existence. Look for a link to “RSS” or “Syndicate This,” or an orange rectangle with the letters “RSS” or “XML” (don’t ask). These links are not always on the home page. You may need to consult the site map to find a link to a page explaining available feeds and how to find them.

Some of the major sites have multiple feeds to choose from. For example, you can generate a feed of current stories related to the page that you are following on Google News by clicking the RSS link on any Google News page.

Once you know the URL of the RSS feed you want, you provide it to your reader program, which will monitor the feed for you. (Many RSS aggregators come preconfigured with a list of feed URLs for popular news websites.)

In addition to notifying you of important news headlines, changes to your favorite websites, and new developments in any medical (or other) field of interest to you, RSS feeds have many other uses. Some will notify you of new products in a store or catalog, new newsletter issues (including email newsletters), weather and other changing-condition alerts, and the addition of new items to a database – or new members to a group.

It can work the other way as well: If you want readers of your website, blog, or podcast to receive the latest news about your practice, such as new treatments and procedures you’re offering – or if you want to know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites – you can create your own RSS feed. In my next column, I’ll explain exactly how to do that.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In my last column, I mentioned RSS news feeds as a useful, versatile online tool. As my editor later reminded me, however, it has been over a decade since I’ve discussed RSS feeds – so an update is certainly in order.

The sheer volume of information on the web makes quick and efficient searching an indispensable skill, but once you become quick and efficient at finding the information you need, a new problem arises: The information changes! All the good medical, news, and other information-based websites change and update their content on a regular but unpredictable basis. And checking each one for new information can be very tedious, if you can remember to do it at all.

Many sites offer an email service to notify you of new content, but multiple email subscriptions clutter your inbox and often can’t select out the information you’re really interested in. RSS feeds are a more efficient and increasingly popular method of staying current on all the subjects that interest you – medical and otherwise. RSS (which stands for Rich Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication, depending on whom you ask) is a file format that websites use (or a similar one called Atom) to produce a summary file, or “feed,” of new content, along with links to full versions of that content. When you subscribe to a given website’s feed, you’ll receive a summary of new content each time the website is updated.

Thousands of websites now offer RSS feeds, including most of the large medical information services, all the major news organizations, and many web logs.

To subscribe to feeds, you must download a program called a feed reader, which is basically just a browser specializing in RSS and Atom files. Dozens of readers (also known as aggregators) are available. Some can be accessed through browsers, others are integrated into email programs, and still others run as standalone applications. With the rise of cloud computing, some cloud-based services offer feed aggregation as part of their service.

Many readers are free, but those with the most advanced features usually come with a fee of some sort. (As always, I have no financial interest in any enterprise discussed in this column.) A comprehensive list of available readers can be found in the Wikipedia article “Comparison of Feed Aggregators.”

It’s not always easy to find out whether a particular website offers a feed, because there is no universally recognized method of indicating its existence. Look for a link to “RSS” or “Syndicate This,” or an orange rectangle with the letters “RSS” or “XML” (don’t ask). These links are not always on the home page. You may need to consult the site map to find a link to a page explaining available feeds and how to find them.

Some of the major sites have multiple feeds to choose from. For example, you can generate a feed of current stories related to the page that you are following on Google News by clicking the RSS link on any Google News page.

Once you know the URL of the RSS feed you want, you provide it to your reader program, which will monitor the feed for you. (Many RSS aggregators come preconfigured with a list of feed URLs for popular news websites.)

In addition to notifying you of important news headlines, changes to your favorite websites, and new developments in any medical (or other) field of interest to you, RSS feeds have many other uses. Some will notify you of new products in a store or catalog, new newsletter issues (including email newsletters), weather and other changing-condition alerts, and the addition of new items to a database – or new members to a group.

It can work the other way as well: If you want readers of your website, blog, or podcast to receive the latest news about your practice, such as new treatments and procedures you’re offering – or if you want to know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites – you can create your own RSS feed. In my next column, I’ll explain exactly how to do that.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Using videos to educate your ObGyn patients

Patient barriers to optimal health-care outcomes are well documented. According to a 2003 estimate from the National Center for Education Statistics, 9 in 10 individuals do not know how to adequately access information readily available for their own health care.1 A December 7, 2013, report in Modern Healthcare stated, “When patients are in doctors’ offices, they (might) hear 50% of what’s being said and maybe their relative hears another 30%, but they walk away without 20%.”2

In addition, patients often do not fill or refill their prescriptions. More than 31% of about 37,000 prescriptions written in a primary care setting for nearly 16,000 patients were not filled.3 Reasons may be poor health literacy, a medication’s expense, or disappointment with lack of drug efficacy. In a 2010 Commonwealth Fund survey, 23.1% of US patients reported not filling a drug prescription in the previous 12 months due to cost,4 and in 2012, 27% did not follow through with recommended testing or treatment.5

On the physician side, the advent of managed care, electronic health records, and requirements to document extraneous information have shortened “face time” with patients. This means less time to educate patients about their conditions and treatments. And patients who have insufficient information may have trouble adhering with recommendations and experience unsatisfactory outcomes.

Using focused patient-education videos can help you circumvent in-office time constraints and inform patients of their conditions and your recommendations, thereby increasing practice efficiency and improving patient outcomes. There are certain considerations you should keep in mind when implementing and executing videos for patients.

Planning your video

With videos, you can convey to patients the exact message you want them to receive. This is far more effective and more appreciatedthan videos distributed by pharmaceutical companies and vendors of equipment used in your office or hospital. If you do not have the time to create patient videos, purchasing professionally created videos could be worth the cost; however, those created by physicians are far better and can be a source of enhanced communication when patients see their own physician on the screen discussing the condition, procedure, or medications prescribed.

We suggest selecting topics you regularly discuss with patients. If the topic of prolapse arises several times a day or week, a video presentation about it would be appropriate. Other topics of interest to gynecology patients are shown in the TABLE. The topics included are those that many of our colleagues find that they discuss with patients frequently and are in need of an instructional video.

Example video topics for patient viewing

• Evaluation of urinary incontinence

• Recurrent urinary tract infection

• Infertility evaluation

• Options for hysterectomy

• Management of menometrorrhagia

• Contraception options (including bilateral tubal ligation)

• Pros and cons of hormone replacement therapy

• Breast self examination

One of us (NB) likes to select topics that are receiving lots of publicity. For example, when flibanserin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015 and patients were asking about it, we created a video with a handout that summarized the drug’s actions and its adverse effects and that emphasized the precaution about using flibanserin in conjunction with alcohol.

Production elements

The script.

- Define the problem/condition

- Offer how the problem is evaluated

- Discuss treatment options

- Go over risks and complications

- Include a summary.

Embedding details of these bullet points into a PowerPoint presentation can serve as your teleprompter. Each video might end with the statement, “I hope you have found this video on <name of topic> informative. If you open the door at the end of the video, I will return to the examination room and provide you with a summary of the <topic> and answer any questions you may have.” We refer to this as the “sandwich technique,” in which the physician interacts with the patient first and performs the examination, invites the patient to watch the video, and returns to the room to conclude the patient visit.

The recording device. Recording can be accomplished easily with technology available in nearly every ObGyn office. You can use a video camera, the webcam on your computer, or a smart phone (probably the easiest choice). The quality of video created with the Apple, Samsung, or Motorola devices is excellent. The only other piece of equipment we recommend is a flexible tripod to hold the phone. Several such tripod stands are available for purchase, but the type with a flexible stand can be beneficial (FIGURE 1). These are available for purchase on Amazon.

| FIGURE 1 Our recommended tripod stand | ||

| ||

The TriFlex Mini Phone Tripod Stand, available for purchase at retailers and at Amazon (http://www.amazon.com/dp/B017NA7V1U?psc=1). | ||

Putting it all together. With the smartphone in the tripod attached to the computer and the PowerPoint program serving as your notes, you are ready to create a video. We suggest limiting the recording to 5 to 7 minutes, the attention span of most patients. Those who want to produce a more professional looking video can use the editing programs iMovie on the Mac or Movie Maker on the PC.

Videos can be uploaded to your website, your EMR, or onto separate computers in each of your examination rooms. Depending on where you upload your videos (your own website or YouTube), patients can access them from home. An advantage of your own website and YouTube is that the videos can be viewed again and by patients’ significant others (which patients often inquire about the ability to do).

Other considerations

Videos that are conversational in nature, using the pronouns “I” and “we” and using such language as “my opinion” and “our patients” may hold the attention of viewers more than didactic “talking head” videos. In addition, creating videos on controversial topics that patients are interested in and need more information about can benefit patients and your practice.

Creating videos in other languages for your patients is an option as well. If you speak the language, then create your video in both English and the other language. Or you can create the script and ask a patient who speaks the non-English language to assist with the video production or voiceover. Also, there are other language videos for patients on YouTube. An excellent example of a Spanish-language gynecologic video on the pelvic examination is available (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKsGYc-dCSI). It is easy to create a link from your website to a YouTube video. This requires requesting permission from the creator of the video. (We do not recommend showcasing another physician on your website.)

Example Patient education videos

Examples of videos on stress urinary incontinence and treatment with a midurethral sling can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BFZj8x3-oCA and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gnOqkXiye0.

Dr. Neil Baum is the author of Social Media for the Healthcare Professional (Greenbranch Publishing, 2012).

Advantages of creating videos

When patients are watching the video, you can conduct visits with other patients and even perform brief office procedures. You can anticipate an up to 15% to 20% improvement in office efficiency by using educational videos. And patients will appreciate the information and the written summary accompanying each video.

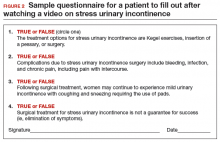

Videos and medical-legal protection

Documentation is necessary to protect yourself from litigation. Record the viewing of a video in a patient’s chart, as well as the receipt of pertinent written information. We suggest you also note that all of the patient’s questions were answered before the patient left the office. To confirm that the patient understood the condition, procedure, or surgery, you can ask the patient to fill out a true/false questionnaire after watching the video and also include it in the chart. A questionnaire I (NB) use after the patient watches a video on stress incontinence is shown in FIGURE 2.

A statement to accompany the questionnaire is also a good idea. Example: “<name of patient> watched a video on the treatment of stress incontinence. The video discussed the procedure and its risks and complications, and alternate treatments, including the option to have no treatment. She agrees to proceeding with a midurethral sling using synthetic mesh and understands the risks and complications associated with the use of mesh.”

An additional helpful option is to end your videos with a comment that addresses the statement and consent form you will ask the patient to sign. For instance, “I will return to the examination room and provide you with a summary of the <topic> and answer any questions you may have. I also will ask you to sign a procedure or operative consent form as well as sign a statement that says you have watched the video, understand the content, and have had your questions answered.”

We believe that this makes the video an excellent medical-legal protection tool for the physician and that the video enhances the informed consent process.

Bottom line

We are challenged today to provide quality care in an efficient and cost-effective manner. This is a concern for every ObGyn practice regardless of its size or location or whether it is a solo or group practice or academic or private. We can improve our efficiency and our productivity, maintain quality of care, improve patient adherence, and even improve outcomes using patient videos. So get ready for lights, camera, and action!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Dept of Education, 2006.

- 1NCES publication 2006-483.2. Modern Healthcare. Providers help patients address emotion, money, health literacy. Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20131207/MAGAZINE/312079983. Accessed April 15, 2016.

- Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Huang A, Winsdale N, Doran P. The incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary care: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):441–450.

- Morgan S, Kennedy J. Prescription drug accessibility and affordability in the United States and abroad. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2010;89:1012.

- Collins SR, Robertson R, Garber T, et al. Insuring the future. Current trends in health coverage and the effects of implementing the Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Fund%20Report/2013/Apr/1681_Collins_insuring_future_biennial_survey_2012_FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2016.

Patient barriers to optimal health-care outcomes are well documented. According to a 2003 estimate from the National Center for Education Statistics, 9 in 10 individuals do not know how to adequately access information readily available for their own health care.1 A December 7, 2013, report in Modern Healthcare stated, “When patients are in doctors’ offices, they (might) hear 50% of what’s being said and maybe their relative hears another 30%, but they walk away without 20%.”2

In addition, patients often do not fill or refill their prescriptions. More than 31% of about 37,000 prescriptions written in a primary care setting for nearly 16,000 patients were not filled.3 Reasons may be poor health literacy, a medication’s expense, or disappointment with lack of drug efficacy. In a 2010 Commonwealth Fund survey, 23.1% of US patients reported not filling a drug prescription in the previous 12 months due to cost,4 and in 2012, 27% did not follow through with recommended testing or treatment.5

On the physician side, the advent of managed care, electronic health records, and requirements to document extraneous information have shortened “face time” with patients. This means less time to educate patients about their conditions and treatments. And patients who have insufficient information may have trouble adhering with recommendations and experience unsatisfactory outcomes.

Using focused patient-education videos can help you circumvent in-office time constraints and inform patients of their conditions and your recommendations, thereby increasing practice efficiency and improving patient outcomes. There are certain considerations you should keep in mind when implementing and executing videos for patients.

Planning your video

With videos, you can convey to patients the exact message you want them to receive. This is far more effective and more appreciatedthan videos distributed by pharmaceutical companies and vendors of equipment used in your office or hospital. If you do not have the time to create patient videos, purchasing professionally created videos could be worth the cost; however, those created by physicians are far better and can be a source of enhanced communication when patients see their own physician on the screen discussing the condition, procedure, or medications prescribed.

We suggest selecting topics you regularly discuss with patients. If the topic of prolapse arises several times a day or week, a video presentation about it would be appropriate. Other topics of interest to gynecology patients are shown in the TABLE. The topics included are those that many of our colleagues find that they discuss with patients frequently and are in need of an instructional video.

Example video topics for patient viewing

• Evaluation of urinary incontinence

• Recurrent urinary tract infection

• Infertility evaluation

• Options for hysterectomy

• Management of menometrorrhagia

• Contraception options (including bilateral tubal ligation)

• Pros and cons of hormone replacement therapy

• Breast self examination

One of us (NB) likes to select topics that are receiving lots of publicity. For example, when flibanserin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015 and patients were asking about it, we created a video with a handout that summarized the drug’s actions and its adverse effects and that emphasized the precaution about using flibanserin in conjunction with alcohol.

Production elements

The script.

- Define the problem/condition

- Offer how the problem is evaluated

- Discuss treatment options

- Go over risks and complications

- Include a summary.

Embedding details of these bullet points into a PowerPoint presentation can serve as your teleprompter. Each video might end with the statement, “I hope you have found this video on <name of topic> informative. If you open the door at the end of the video, I will return to the examination room and provide you with a summary of the <topic> and answer any questions you may have.” We refer to this as the “sandwich technique,” in which the physician interacts with the patient first and performs the examination, invites the patient to watch the video, and returns to the room to conclude the patient visit.

The recording device. Recording can be accomplished easily with technology available in nearly every ObGyn office. You can use a video camera, the webcam on your computer, or a smart phone (probably the easiest choice). The quality of video created with the Apple, Samsung, or Motorola devices is excellent. The only other piece of equipment we recommend is a flexible tripod to hold the phone. Several such tripod stands are available for purchase, but the type with a flexible stand can be beneficial (FIGURE 1). These are available for purchase on Amazon.

| FIGURE 1 Our recommended tripod stand | ||

| ||

The TriFlex Mini Phone Tripod Stand, available for purchase at retailers and at Amazon (http://www.amazon.com/dp/B017NA7V1U?psc=1). | ||

Putting it all together. With the smartphone in the tripod attached to the computer and the PowerPoint program serving as your notes, you are ready to create a video. We suggest limiting the recording to 5 to 7 minutes, the attention span of most patients. Those who want to produce a more professional looking video can use the editing programs iMovie on the Mac or Movie Maker on the PC.

Videos can be uploaded to your website, your EMR, or onto separate computers in each of your examination rooms. Depending on where you upload your videos (your own website or YouTube), patients can access them from home. An advantage of your own website and YouTube is that the videos can be viewed again and by patients’ significant others (which patients often inquire about the ability to do).

Other considerations

Videos that are conversational in nature, using the pronouns “I” and “we” and using such language as “my opinion” and “our patients” may hold the attention of viewers more than didactic “talking head” videos. In addition, creating videos on controversial topics that patients are interested in and need more information about can benefit patients and your practice.

Creating videos in other languages for your patients is an option as well. If you speak the language, then create your video in both English and the other language. Or you can create the script and ask a patient who speaks the non-English language to assist with the video production or voiceover. Also, there are other language videos for patients on YouTube. An excellent example of a Spanish-language gynecologic video on the pelvic examination is available (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKsGYc-dCSI). It is easy to create a link from your website to a YouTube video. This requires requesting permission from the creator of the video. (We do not recommend showcasing another physician on your website.)

Example Patient education videos

Examples of videos on stress urinary incontinence and treatment with a midurethral sling can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BFZj8x3-oCA and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gnOqkXiye0.

Dr. Neil Baum is the author of Social Media for the Healthcare Professional (Greenbranch Publishing, 2012).

Advantages of creating videos

When patients are watching the video, you can conduct visits with other patients and even perform brief office procedures. You can anticipate an up to 15% to 20% improvement in office efficiency by using educational videos. And patients will appreciate the information and the written summary accompanying each video.

Videos and medical-legal protection

Documentation is necessary to protect yourself from litigation. Record the viewing of a video in a patient’s chart, as well as the receipt of pertinent written information. We suggest you also note that all of the patient’s questions were answered before the patient left the office. To confirm that the patient understood the condition, procedure, or surgery, you can ask the patient to fill out a true/false questionnaire after watching the video and also include it in the chart. A questionnaire I (NB) use after the patient watches a video on stress incontinence is shown in FIGURE 2.

A statement to accompany the questionnaire is also a good idea. Example: “<name of patient> watched a video on the treatment of stress incontinence. The video discussed the procedure and its risks and complications, and alternate treatments, including the option to have no treatment. She agrees to proceeding with a midurethral sling using synthetic mesh and understands the risks and complications associated with the use of mesh.”

An additional helpful option is to end your videos with a comment that addresses the statement and consent form you will ask the patient to sign. For instance, “I will return to the examination room and provide you with a summary of the <topic> and answer any questions you may have. I also will ask you to sign a procedure or operative consent form as well as sign a statement that says you have watched the video, understand the content, and have had your questions answered.”

We believe that this makes the video an excellent medical-legal protection tool for the physician and that the video enhances the informed consent process.

Bottom line

We are challenged today to provide quality care in an efficient and cost-effective manner. This is a concern for every ObGyn practice regardless of its size or location or whether it is a solo or group practice or academic or private. We can improve our efficiency and our productivity, maintain quality of care, improve patient adherence, and even improve outcomes using patient videos. So get ready for lights, camera, and action!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Patient barriers to optimal health-care outcomes are well documented. According to a 2003 estimate from the National Center for Education Statistics, 9 in 10 individuals do not know how to adequately access information readily available for their own health care.1 A December 7, 2013, report in Modern Healthcare stated, “When patients are in doctors’ offices, they (might) hear 50% of what’s being said and maybe their relative hears another 30%, but they walk away without 20%.”2

In addition, patients often do not fill or refill their prescriptions. More than 31% of about 37,000 prescriptions written in a primary care setting for nearly 16,000 patients were not filled.3 Reasons may be poor health literacy, a medication’s expense, or disappointment with lack of drug efficacy. In a 2010 Commonwealth Fund survey, 23.1% of US patients reported not filling a drug prescription in the previous 12 months due to cost,4 and in 2012, 27% did not follow through with recommended testing or treatment.5

On the physician side, the advent of managed care, electronic health records, and requirements to document extraneous information have shortened “face time” with patients. This means less time to educate patients about their conditions and treatments. And patients who have insufficient information may have trouble adhering with recommendations and experience unsatisfactory outcomes.

Using focused patient-education videos can help you circumvent in-office time constraints and inform patients of their conditions and your recommendations, thereby increasing practice efficiency and improving patient outcomes. There are certain considerations you should keep in mind when implementing and executing videos for patients.

Planning your video

With videos, you can convey to patients the exact message you want them to receive. This is far more effective and more appreciatedthan videos distributed by pharmaceutical companies and vendors of equipment used in your office or hospital. If you do not have the time to create patient videos, purchasing professionally created videos could be worth the cost; however, those created by physicians are far better and can be a source of enhanced communication when patients see their own physician on the screen discussing the condition, procedure, or medications prescribed.

We suggest selecting topics you regularly discuss with patients. If the topic of prolapse arises several times a day or week, a video presentation about it would be appropriate. Other topics of interest to gynecology patients are shown in the TABLE. The topics included are those that many of our colleagues find that they discuss with patients frequently and are in need of an instructional video.

Example video topics for patient viewing

• Evaluation of urinary incontinence

• Recurrent urinary tract infection

• Infertility evaluation

• Options for hysterectomy

• Management of menometrorrhagia

• Contraception options (including bilateral tubal ligation)

• Pros and cons of hormone replacement therapy

• Breast self examination

One of us (NB) likes to select topics that are receiving lots of publicity. For example, when flibanserin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015 and patients were asking about it, we created a video with a handout that summarized the drug’s actions and its adverse effects and that emphasized the precaution about using flibanserin in conjunction with alcohol.

Production elements

The script.

- Define the problem/condition

- Offer how the problem is evaluated

- Discuss treatment options

- Go over risks and complications

- Include a summary.

Embedding details of these bullet points into a PowerPoint presentation can serve as your teleprompter. Each video might end with the statement, “I hope you have found this video on <name of topic> informative. If you open the door at the end of the video, I will return to the examination room and provide you with a summary of the <topic> and answer any questions you may have.” We refer to this as the “sandwich technique,” in which the physician interacts with the patient first and performs the examination, invites the patient to watch the video, and returns to the room to conclude the patient visit.

The recording device. Recording can be accomplished easily with technology available in nearly every ObGyn office. You can use a video camera, the webcam on your computer, or a smart phone (probably the easiest choice). The quality of video created with the Apple, Samsung, or Motorola devices is excellent. The only other piece of equipment we recommend is a flexible tripod to hold the phone. Several such tripod stands are available for purchase, but the type with a flexible stand can be beneficial (FIGURE 1). These are available for purchase on Amazon.

| FIGURE 1 Our recommended tripod stand | ||

| ||

The TriFlex Mini Phone Tripod Stand, available for purchase at retailers and at Amazon (http://www.amazon.com/dp/B017NA7V1U?psc=1). | ||

Putting it all together. With the smartphone in the tripod attached to the computer and the PowerPoint program serving as your notes, you are ready to create a video. We suggest limiting the recording to 5 to 7 minutes, the attention span of most patients. Those who want to produce a more professional looking video can use the editing programs iMovie on the Mac or Movie Maker on the PC.

Videos can be uploaded to your website, your EMR, or onto separate computers in each of your examination rooms. Depending on where you upload your videos (your own website or YouTube), patients can access them from home. An advantage of your own website and YouTube is that the videos can be viewed again and by patients’ significant others (which patients often inquire about the ability to do).

Other considerations

Videos that are conversational in nature, using the pronouns “I” and “we” and using such language as “my opinion” and “our patients” may hold the attention of viewers more than didactic “talking head” videos. In addition, creating videos on controversial topics that patients are interested in and need more information about can benefit patients and your practice.

Creating videos in other languages for your patients is an option as well. If you speak the language, then create your video in both English and the other language. Or you can create the script and ask a patient who speaks the non-English language to assist with the video production or voiceover. Also, there are other language videos for patients on YouTube. An excellent example of a Spanish-language gynecologic video on the pelvic examination is available (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKsGYc-dCSI). It is easy to create a link from your website to a YouTube video. This requires requesting permission from the creator of the video. (We do not recommend showcasing another physician on your website.)

Example Patient education videos

Examples of videos on stress urinary incontinence and treatment with a midurethral sling can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BFZj8x3-oCA and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gnOqkXiye0.

Dr. Neil Baum is the author of Social Media for the Healthcare Professional (Greenbranch Publishing, 2012).

Advantages of creating videos

When patients are watching the video, you can conduct visits with other patients and even perform brief office procedures. You can anticipate an up to 15% to 20% improvement in office efficiency by using educational videos. And patients will appreciate the information and the written summary accompanying each video.

Videos and medical-legal protection

Documentation is necessary to protect yourself from litigation. Record the viewing of a video in a patient’s chart, as well as the receipt of pertinent written information. We suggest you also note that all of the patient’s questions were answered before the patient left the office. To confirm that the patient understood the condition, procedure, or surgery, you can ask the patient to fill out a true/false questionnaire after watching the video and also include it in the chart. A questionnaire I (NB) use after the patient watches a video on stress incontinence is shown in FIGURE 2.

A statement to accompany the questionnaire is also a good idea. Example: “<name of patient> watched a video on the treatment of stress incontinence. The video discussed the procedure and its risks and complications, and alternate treatments, including the option to have no treatment. She agrees to proceeding with a midurethral sling using synthetic mesh and understands the risks and complications associated with the use of mesh.”

An additional helpful option is to end your videos with a comment that addresses the statement and consent form you will ask the patient to sign. For instance, “I will return to the examination room and provide you with a summary of the <topic> and answer any questions you may have. I also will ask you to sign a procedure or operative consent form as well as sign a statement that says you have watched the video, understand the content, and have had your questions answered.”

We believe that this makes the video an excellent medical-legal protection tool for the physician and that the video enhances the informed consent process.

Bottom line

We are challenged today to provide quality care in an efficient and cost-effective manner. This is a concern for every ObGyn practice regardless of its size or location or whether it is a solo or group practice or academic or private. We can improve our efficiency and our productivity, maintain quality of care, improve patient adherence, and even improve outcomes using patient videos. So get ready for lights, camera, and action!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Dept of Education, 2006.

- 1NCES publication 2006-483.2. Modern Healthcare. Providers help patients address emotion, money, health literacy. Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20131207/MAGAZINE/312079983. Accessed April 15, 2016.

- Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Huang A, Winsdale N, Doran P. The incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary care: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):441–450.

- Morgan S, Kennedy J. Prescription drug accessibility and affordability in the United States and abroad. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2010;89:1012.

- Collins SR, Robertson R, Garber T, et al. Insuring the future. Current trends in health coverage and the effects of implementing the Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Fund%20Report/2013/Apr/1681_Collins_insuring_future_biennial_survey_2012_FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2016.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Dept of Education, 2006.

- 1NCES publication 2006-483.2. Modern Healthcare. Providers help patients address emotion, money, health literacy. Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20131207/MAGAZINE/312079983. Accessed April 15, 2016.

- Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Huang A, Winsdale N, Doran P. The incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary care: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):441–450.

- Morgan S, Kennedy J. Prescription drug accessibility and affordability in the United States and abroad. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2010;89:1012.

- Collins SR, Robertson R, Garber T, et al. Insuring the future. Current trends in health coverage and the effects of implementing the Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Fund%20Report/2013/Apr/1681_Collins_insuring_future_biennial_survey_2012_FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2016.

In this article

• Videos and medical-legal protection

• Patient questionnaire post-video viewing

Your online reputation

Have you ever run across a negative or even malicious comment about you or your practice on the web, in full view of the world? You’re certainly not alone.

Chances are it was on one of those doctor rating sites, whose supposedly “objective” evaluations are anything but fair or accurate; one curmudgeon, angry about something that usually has nothing to do with your clinical skills, can use his First Amendment–protected right to trash you unfairly, as thousands of satisfied patients remain silent.

What to do? You could hire one of the many companies in the rapidly burgeoning field of online reputation management; but that can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars per month for monitoring and intervention, and there are no guarantees of success.

A better solution is to generate your own search results – positive ones – that will overwhelm any negative comments that search engines might find. Start with the social networking sites. However you feel about networking, there’s no getting around the fact that personal pages on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter rank very high on major search engines. (Some consultants say a favorable LinkedIn profile is particularly helpful because of that site’s reputation as a “professional” network.) Your community activities, charitable work, interesting hobbies – anything that casts you in a favorable light – need to be mentioned prominently in your network profiles.

You can also use Google’s profiling tool (https://plus.google.com/up/accounts/) to create a sterling bio, complete with links to URLs, photos, and anything else that shows you in the best possible light. And your Google profile will be at or near the top of any Google search.

Wikipedia articles also go to the top of most searches, so if you’re notable enough to merit mention in one – or to have one of your own – see that it is done, and updated regularly. You can’t do that yourself, however; Wikipedia’s conflict of interest rules forbid writing or editing content about yourself. Someone with a theoretically “neutral point of view” will have to do it.

If you don’t yet have a website, now would be a good time. As I’ve discussed many times, a professionally designed site will be far more attractive and polished than anything you could build yourself. Furthermore, an experienced designer will employ “search engine optimization” (SEO), meaning that content will be created in a way that is readily visible to search engine users.

Leave design and SEO to the pros, but don’t delegate the content itself; as captain of the ship you are responsible for all the facts and opinions on your site. And remember that once it’s online, it’s online forever; consider the ramifications of anything you post on any site (yours or others) before hitting the “send” button. “The most damaging item about you,” one consultant told me, “could well be something you posted yourself.” Just ask any of several prominent politicians who have famously sabotaged their own careers online.

That said, don’t be shy about creating content. Make your (noncontroversial) opinions known on Facebook and Twitter. If social networks are not your thing, add a blog to your web site and write about what you know, and what interests you. If you have expertise in a particular field, write about that.

Incidentally, if the URL for your web site is not your name, you should also register your name as a separate domain name – if only to be sure that a trickster, or someone with the same name and a bad reputation, doesn’t get it.

Set up an RSS news feed for yourself, so you’ll know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites, or on blogs. If something untrue is posted about you, take action. Reputable news sites and blogs have their own reputations to protect, and so can usually be persuaded to correct anything that is demonstrably false. Try to get the error removed entirely, or corrected within the original article. An erratum on the last page of the next edition will be ignored, and will leave the false information online, intact.

Unfair comments on doctor rating sites are unlikely to be removed unless they are blatantly libelous; but there is nothing wrong with encouraging happy patients to write favorable reviews. Turnabout is fair play.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Have you ever run across a negative or even malicious comment about you or your practice on the web, in full view of the world? You’re certainly not alone.

Chances are it was on one of those doctor rating sites, whose supposedly “objective” evaluations are anything but fair or accurate; one curmudgeon, angry about something that usually has nothing to do with your clinical skills, can use his First Amendment–protected right to trash you unfairly, as thousands of satisfied patients remain silent.

What to do? You could hire one of the many companies in the rapidly burgeoning field of online reputation management; but that can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars per month for monitoring and intervention, and there are no guarantees of success.

A better solution is to generate your own search results – positive ones – that will overwhelm any negative comments that search engines might find. Start with the social networking sites. However you feel about networking, there’s no getting around the fact that personal pages on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter rank very high on major search engines. (Some consultants say a favorable LinkedIn profile is particularly helpful because of that site’s reputation as a “professional” network.) Your community activities, charitable work, interesting hobbies – anything that casts you in a favorable light – need to be mentioned prominently in your network profiles.

You can also use Google’s profiling tool (https://plus.google.com/up/accounts/) to create a sterling bio, complete with links to URLs, photos, and anything else that shows you in the best possible light. And your Google profile will be at or near the top of any Google search.

Wikipedia articles also go to the top of most searches, so if you’re notable enough to merit mention in one – or to have one of your own – see that it is done, and updated regularly. You can’t do that yourself, however; Wikipedia’s conflict of interest rules forbid writing or editing content about yourself. Someone with a theoretically “neutral point of view” will have to do it.

If you don’t yet have a website, now would be a good time. As I’ve discussed many times, a professionally designed site will be far more attractive and polished than anything you could build yourself. Furthermore, an experienced designer will employ “search engine optimization” (SEO), meaning that content will be created in a way that is readily visible to search engine users.

Leave design and SEO to the pros, but don’t delegate the content itself; as captain of the ship you are responsible for all the facts and opinions on your site. And remember that once it’s online, it’s online forever; consider the ramifications of anything you post on any site (yours or others) before hitting the “send” button. “The most damaging item about you,” one consultant told me, “could well be something you posted yourself.” Just ask any of several prominent politicians who have famously sabotaged their own careers online.

That said, don’t be shy about creating content. Make your (noncontroversial) opinions known on Facebook and Twitter. If social networks are not your thing, add a blog to your web site and write about what you know, and what interests you. If you have expertise in a particular field, write about that.

Incidentally, if the URL for your web site is not your name, you should also register your name as a separate domain name – if only to be sure that a trickster, or someone with the same name and a bad reputation, doesn’t get it.

Set up an RSS news feed for yourself, so you’ll know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites, or on blogs. If something untrue is posted about you, take action. Reputable news sites and blogs have their own reputations to protect, and so can usually be persuaded to correct anything that is demonstrably false. Try to get the error removed entirely, or corrected within the original article. An erratum on the last page of the next edition will be ignored, and will leave the false information online, intact.

Unfair comments on doctor rating sites are unlikely to be removed unless they are blatantly libelous; but there is nothing wrong with encouraging happy patients to write favorable reviews. Turnabout is fair play.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Have you ever run across a negative or even malicious comment about you or your practice on the web, in full view of the world? You’re certainly not alone.

Chances are it was on one of those doctor rating sites, whose supposedly “objective” evaluations are anything but fair or accurate; one curmudgeon, angry about something that usually has nothing to do with your clinical skills, can use his First Amendment–protected right to trash you unfairly, as thousands of satisfied patients remain silent.

What to do? You could hire one of the many companies in the rapidly burgeoning field of online reputation management; but that can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars per month for monitoring and intervention, and there are no guarantees of success.

A better solution is to generate your own search results – positive ones – that will overwhelm any negative comments that search engines might find. Start with the social networking sites. However you feel about networking, there’s no getting around the fact that personal pages on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter rank very high on major search engines. (Some consultants say a favorable LinkedIn profile is particularly helpful because of that site’s reputation as a “professional” network.) Your community activities, charitable work, interesting hobbies – anything that casts you in a favorable light – need to be mentioned prominently in your network profiles.

You can also use Google’s profiling tool (https://plus.google.com/up/accounts/) to create a sterling bio, complete with links to URLs, photos, and anything else that shows you in the best possible light. And your Google profile will be at or near the top of any Google search.

Wikipedia articles also go to the top of most searches, so if you’re notable enough to merit mention in one – or to have one of your own – see that it is done, and updated regularly. You can’t do that yourself, however; Wikipedia’s conflict of interest rules forbid writing or editing content about yourself. Someone with a theoretically “neutral point of view” will have to do it.

If you don’t yet have a website, now would be a good time. As I’ve discussed many times, a professionally designed site will be far more attractive and polished than anything you could build yourself. Furthermore, an experienced designer will employ “search engine optimization” (SEO), meaning that content will be created in a way that is readily visible to search engine users.

Leave design and SEO to the pros, but don’t delegate the content itself; as captain of the ship you are responsible for all the facts and opinions on your site. And remember that once it’s online, it’s online forever; consider the ramifications of anything you post on any site (yours or others) before hitting the “send” button. “The most damaging item about you,” one consultant told me, “could well be something you posted yourself.” Just ask any of several prominent politicians who have famously sabotaged their own careers online.

That said, don’t be shy about creating content. Make your (noncontroversial) opinions known on Facebook and Twitter. If social networks are not your thing, add a blog to your web site and write about what you know, and what interests you. If you have expertise in a particular field, write about that.

Incidentally, if the URL for your web site is not your name, you should also register your name as a separate domain name – if only to be sure that a trickster, or someone with the same name and a bad reputation, doesn’t get it.

Set up an RSS news feed for yourself, so you’ll know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites, or on blogs. If something untrue is posted about you, take action. Reputable news sites and blogs have their own reputations to protect, and so can usually be persuaded to correct anything that is demonstrably false. Try to get the error removed entirely, or corrected within the original article. An erratum on the last page of the next edition will be ignored, and will leave the false information online, intact.

Unfair comments on doctor rating sites are unlikely to be removed unless they are blatantly libelous; but there is nothing wrong with encouraging happy patients to write favorable reviews. Turnabout is fair play.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Goodbye measures of data quantity, hello data quality measures of MACRA

Practicing clinical medicine is increasingly challenging. Besides the onslaught of new clinical information, we have credentialing, accreditation, certification, team-based care, and patient satisfaction that contribute to the complexity of current medical practice. At the heart of many of these challenges is the issue of accountability. Never has our work product as physicians been under such intense scrutiny as it is today.

To demonstrate proof of the care we have provided, we have enlisted a host of administrators, assistants, abstractors, and other helpers to decipher our work and demonstrate its value to professional organizations, boards, hospitals, insurers, and the government. They comb through our charts, decipher our handwriting and dictations, guesstimate our intentions, and sometimes devalue our care because we have not adequately documented what we have done. To solve this accountability problem, our government and the payer community have promoted the electronic health record (EHR) as the “single source of truth” for the care we provide.

This effort received a huge boost in 2009 with the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. HITECH authorized incentive payments through Medicare and Medicaid to health care providers that could demonstrate Meaningful Use (MU) of a certified EHR. This resulted in a boom in EHR purchases and installations.

By 2012, 71.8% of office-based physicians reported using some type of EHR system, up from 34.8% in 2007.1 In many respects this action was designed as a stimulus for the slow economy, but Congress also wanted some type of accountability that the money spent to subsidize EHR purchases was going to be well spent, and would hopefully have an impact on some of the serious health issues we face.

The initial stage of this MU program seemed to work out reasonably well. So, if a little is good, more must be better, right? Unfortunately, no. But, where did MU go wrong, and how is it being fixed? Contrary to popular belief, MU is not going away, it is being transformed. To help you navigate the tethered landscape of MU past and, more importantly, bring you up to speed on MU future (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 [MACRA]) and your payment incentives in this data-centric world, we address MU transformation in this article.

Where Meaningful Use stage 2 went wrong

MU stage 2 turned out to significantly increase the documentation burden on health care professionals. In addition, one of the tragic unintended consequences was that all available EHR development resources by vendors went toward meeting MU data capture requirements rather than to improving the usability and efficiency of the EHRs. Neither result has been well received by health care professionals.

Stage 3 of MU is now in place. It is an attempt to simplify the requirements and focus on quality, safety, interoperability, and patient engagement. See “Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications”. The current progression of MU stages is depicted in TABLE 1.2

Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications

Objective 1: Protect patient health information. Protect electronic health information created or maintained by the Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) through the implementation of appropriate technical, administrative, and physical safeguards.

Objective 2: Electronic prescribing. Eligible providers (EPs) must generate and transmit permissible prescriptions electronically, and eligible hospitals must generate and transmit permissible discharge prescriptions electronically.

Objective 3: Clinical decision support. Implement clinical decision support interventions focused on improving performance on high-priority health conditions.

Objective 4: Computerized provider order entry. Use computerized provider order entry for medication, laboratory, and diagnostic imaging orders directly entered by any licensed health care professional, credentialed medical assistant, or a medical staff member credentialed and performing the equivalent duties of a credentialed medical assistant, who can enter orders into the medical record per state, local, and professional guidelines.

Objective 5: Patient electronic access to health information. The EP provides patients (or patient-authorized representatives) with timely electronic access to their health information and patient-specific education.

Objective 6: Coordination of care through patient engagement. Use the CEHRT to engage with patients or their authorized representatives about the patient's care.

Objective 7: Health information exchange. The EP provides a summary of care record when transitioning or referring their patient to another setting of care, receives or retrieves a summary of care record upon the receipt of a transition or referral or upon the first patient encounter with a new patient, and incorporates summary of care information from other providers into their EHR using the functions of CEHRT.

Objective 8: Public health and clinical data registry reporting. The EP is in active engagement with a public health agency or clinical data registry to submit electronic public health data in a meaningful way using certified EHR technology, except where prohibited, and in accordance with applicable law and practice.

Reference

1. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 3. Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/30/2015-06685/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3#t-4. Accessed March 19, 2016.

Our new paradigm

Now that EHR implementation is fairly widespread, attention is focused on streamlining the reporting and documentation required for accountability, both from the data entry standpoint and the data analysis standpoint. Discrete data elements, entered by clinicians at the point of care, and downloaded directly from the EHR increasingly will be the way our patient care is assessed. Understanding this new paradigm is critical for both practice and professional viability.

Challenges in this new era

To understand the challenges ahead, we must first take a critical look at how physicians think about documentation, and what changes these models of documentation will have to undergo. Physicians are taught to think in complex models that we document as narratives or stories. While these models are composed of individual “elements” (patient age, due date, hemoglobin value, systolic blood pressure), the real information is in how these elements are related. Understanding a patient, a disease process, or a clinical workflow involves elements that must have context and relationships to be meaningful. Isolated hemoglobin or systolic blood pressure values tell us little, and may in fact obscure the forest for the trees. Physicians want to tell, and understand, the story.

However, an EHR is much more than a collection of narrative text documents. Entering data as discrete elements will allow each data element to be standardized, delegated, automated, analyzed, and monetized. In fact, these processes cannot be accomplished without the data being in this discrete form. While a common complaint about EHRs is that the “story” is hard to decipher, discrete elements are here to stay. Algorithms that can “read” a story and automatically populate these elements (known as natural language processing, or NLP) may someday allow us to go back to our dictations, but that day is frustratingly still far off.

Hello eCQMs

Up to now, physicians have relied on an army of abstractors, coders, billers, quality and safety helpers, and the like to read our notes and supply discrete data to the many clients who want to see accountability for our work. This process of course adds considerable cost to the health care system, and the data collected may not always supply accurate information. The gap between administrative data (gathered from the International Classificationof Diseases Ninth and Tenth revisions and Current Procedural Terminology [copyright American Medical Association] codes) and clinical reality is well documented.3–5

In an attempt to simplify this process, and to create a stronger connection to actual clinical data, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)6 is moving toward direct extraction of discrete data that have been entered by health care providers themselves.7 Using clinical data to report on quality metrics allows for improvement in risk adjustment as well as accuracy. Specific measures of this type have been designated eCQMs.

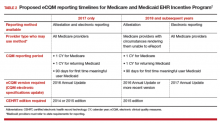

An eCQM is a format for a quality measure, utilizing data entered directly by health care professionals, and extracted directly from the EHR, without the need for additional personnel to review and abstract the chart. eCQMs rapidly are being phased into use for Medicare reimbursement; it is assumed that Medicaid and private payers soon will follow. Instead of payment solely for the quantity of documentation and intervention, we will soon also be paid for the quality of the care we provide (and document). TABLE 2 includes the proposed eCQM reporting timelines for Medicare and Medicaid.2

MACRA

eCQMs are a part of a larger federal effort to reform physician payments—MACRA. Over the past few years, there have been numerous federal programs to measure the quality and appropriateness of care. The Evaluation and Management (E&M) coding guidelines have been supplemented with factors for quality (Physician Quality Reporting System [PQRS]), resource use (the Value-based Payment Modifier), and EHR engagement (MU stages 1, 2, and 3). All of these programs are now being rolled up into a single program under MACRA.

MACRA has 2 distinct parts, known as the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and the Alternative Payment Model. MIPS keeps the underlying fee-for-service model but adds in a factor based on the following metrics:

- clinical quality (which will be based on eCQMs)

- resource use (a gauge of how many economic resources you use in comparison to your peers)

- clinical practice improvement (a measure of how well you are engaged in quality improvement, which includes capturing patient satisfaction data, and being part of a qualified clinical data registry is one way to demonstrate that engagement)

- meaningful use of EHR.

It is important to understand this last bulleted metric: MU is not going away (although that is a popular belief), it is just being transformed into MACRA, with the MU criteria simplified to emphasize a patient-centered medical record. Getting your patients involved through a portal and being able yourself to download, transmit, and accept patients’ data in electronic form are significant parts of MU. Vendors will continue to bear some of this burden, as their requirement to produce systems capable of these functions also increases their accountability.

Measurement and payment incentive

In the MIPS part of MACRA, the 4 factors of clinical quality, resource use, clinical practice improvement, and meaningful use of EHR will be combined in a formula to determine where each practitioner lies in comparison to his or her peers.

Now the bad news: Instead of receiving a bonus by meeting a benchmark, the bonus funds will be subtracted from those providers on the low end of the curve, and given to those at the top end. No matter how well the group does as a whole, no additional money will be available, and the bottom tier will be paying the bonuses of the top tier. The total pool of money to be distributed by CMS in the MIPS program will only grow by 0.5% per year for the foreseeable future. But MACRA does provide an alternative model for reimbursement, the Alternative Payment Model.

Alternative Payment Model

The Alternative Payment Model is basically an Accountable Care Organization—a group of providers agree to meet a certain standard of care (eCQMs again) and, in turn, receive a lump sum of money to deliver that care to a population. If there is some money left over at the end of a year, the group runs a profit. If not, they run a loss. One advantage of this model is that, under MACRA, the pool of money paid to “qualified” groups will increase at 5% per year for the next 5 years. This is certainly a better deal than the 0.5% increase of MIPS.

For specialists in general obstetrics and gynecology it may very well be that the volume of Medicare patients we see will be insufficient to participate meaningfully in either MIPS or the Alternative Payment Model. Regulations are still being crafted to exempt low-volume providers from the burdens associated with MACRA, and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) is working diligently to advocate for systems that will allow members to see Medicare patients without requiring the substantial investments these programs likely will require.

The EHR: The single source of truth

The push to make the EHR the single source of truth will streamline many peripheral activities on the health care delivery side as well as the payer side. These requirements will present a new challenge to health care professionals, however. No one went to medical school to become a data entry clerk. Still, EHRs show the promise to transform many aspects of health care delivery. They speed communication,8 reduce errors,9 and may well improve the safety and quality of care. There also is some evidence developing that they may slow the rising cost of health care.10

But they are also quickly becoming a major source of physician dissatisfaction,11 with an apparent dose-response relationship.12 Authors of a recent RAND study note, “the current state of EHR technology significantly worsened professional satisfaction in multiple ways, due to poor usability, time-consuming data entry, interference with face-to-face patient care, inefficient and less fulfilling work content, insufficient health information exchange, and degradation of clinical documentation.”13

This pushback against EHRs has beenheard all the way to Congress. The Senate recently has introduced the ‘‘Improving Health Information Technology Act.’’14 This bill includes proposals for rating EHR systems, decreasing “unnecessary” documentation, prohibiting “information blocking,” and increasing interoperability. It remains to be seen what specific actions will be included, and how this bill will fare in an election year.

So the practice of medicine continues to evolve, and our accountability obligations show no sign of slowing down. The vision of the EHR as a single source of truth—the tool to streamline both the data entry and the data analysis—is being pushed hard by the folks who control the purse strings. This certainly will change the way we conduct our work as physicians and health care professionals. There are innovative efforts being developed to ease this burden. Cloud-based object-oriented data models, independent “apps,” open Application Programming Interfaces, or other technologies may supplant the transactional billing platforms15 we now rely upon.

ACOG is engaged at many levels with these issues, and we will continue to keep the interests of our members and the health of our patients at the center of our efforts. But it seems that, at least for now, a move to capturing discrete data elements and relying on eCQMs for quality measurements will shape the foreseeable payment incentive future.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Hsiao CJ, Hing E, Ashman J. Trends in electronic health record system use among office-based physicians: United States, 2007–2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2014;(75):1–18.

- Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 3. Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/30/2015-06685/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3#t-4. Published March 10, 2015. Accessed March 19, 2016.

- Assareh H, Achat HM, Stubbs JM, Guevarra VM, Hill K.Incidence and variation of discrepancies in recording chronic conditions in Australian hospital administrative data. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147087.

- Williams DJ, Shah SS, Myers A, et al. Identifying pediatric community-acquired pneumonia hospitalizations: Accuracy of administrative billing codes. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(9):851–858.

- Liede A, Hernandez RK, Roth M, Calkins G, Larrabee K, Nicacio L. Validation of International Classification of Diseases coding for bone metastases in electronic health records using technology-enabled abstraction. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:441–448.

- Revisions of Quality Reporting Requirements for Specific Providers, Including Changes Related to the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program. Federal Register website. https://federalregister.gov/a/2015-19049. Published August 17, 2015. Accessed March 19, 2016.

- Panjamapirom A. Hospitals: Electronic CQM Reporting Has Arrived. Are You Ready? http://www.ihealthbeat.org/perspectives/2015/hospitals-electronic-cqm-reporting-has -arrived-are-you-ready. Published August 24, 2015. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Bernstein PS, Farinelli C, Merkatz IR. Using an electronic medical record to improve communication within a prenatal care network. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(3):607–612.

- George J, Bernstein PS. Using electronic medical records to reduce errors and risks in a prenatal network. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21(6):527–531.

- Adler-Milstein J, Salzberg C, Franz C, Orav EJ, Newhouse JP, Bates DW. Effect of electronic health records on health care costs: longitudinal comparative evidence from community practices. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):97–104.

- Pedulli L. Survey reveals widespread dissatisfaction with EHR systems. http://www.clinical-innovation.com/topics/ehr-emr/survey-reveals-widespread-dissatisfaction-ehr-systems. Published February 11, 2014. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100–e106.

- Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. RAND Corporation website. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR439.html. Published 2013. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Majority and Minority Staff of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. Summary of Improving Health Information Technology Act. http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Improving%20Health%20Information%20Technology%20Act%20--%20Summary.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2016.

- LetDoctorsbeDoctors.com. http://www.letdoctorsbedoctors.com/?sf21392355=1. Published 2016. Accessed March 18, 2016.