User login

Four pillars of a successful practice: 2. Attract new patients

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 3: Obtain and maintain physician referrals (June 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

External marketing is nothing more than making potential patients aware of your service and areas of expertise. The public truly does not mind marketing, as long as it believes you are communicating useful information and providing value. Nevertheless, such marketing—getting the word out to the public and potential referring physicians—takes some physicians out of their comfort zone. Some doctors think that marketing is synonymous with advertising.

The truth is, you can make the public aware of your services and expertise in an ethical and professional fashion without spending large amounts of money on advertising or hiring an expensive consultant.

How?

The essence of external marketing is writing, speaking, and making use of the Internet. In this article, I review simple, inexpensive techniques to increase your visibility among your peers and in your community. These techniques do not require additional staff or anything more than minimal assistance from your hospital’s public relations and marketing departments and the creation of a few PowerPoint slides that will hold the attention of your audience. A future article will describe Internet marketing strategies.

Try your hand at public speaking

Few of us are natural-born orators, but if you get started on the speaking circuit and acquire effective skills, you’ll be amazed at the demand for your presentations and the commensurate number of new patients filling your appointment book. When you take your message to the podium, audiences have an opportunity not only to learn more about your medical topic and how it applies to their health and wellness, but also to interact with you before and after the presentation.

Most of us have been asked to give a presentation to a lay audience at some time or another. How many of us have set off with a PowerPoint presentation from a pharmaceutical company that contains information far too technical for a nonmedical audience? Is it any wonder that so few talks motivate new patients to call our practices?

How to get invited to speak at local events

Even if you have a knack for public speaking, you still need to generate invitations for speaking engagements. I systematically contact meeting planners at various churches, service organizations like the Junior League, women’s book clubs, and patient advocacy groups, such as the American Cancer Society and American Diabetes Association. A list of these organizations and clubs can be obtained from the Chamber of Commerce in your community.

When I began public speaking, I created a public relations packet and sent it to meeting planners in the community. The packet contained a brief biography that outlined my credentials, listed organizations or groups to which I have given talks in the past, and provided a few testimonials from previous audience members. I also included a fact sheet (see the box on this page) and several articles on the topic to be covered. The articles were written by me for local outlets or written by others for publication in national magazines or other lay publications.

After I delivered a talk, I hung around to answer questions. I also made sure to have plenty of business cards to hand out, as well as my practice brochure and articles that pertained to the topic I had just presented.

Overactive bladder: You don’t have to depend on Depends!

Overactive bladder is a common disorder that affects millions of American women and men. Most people who have this condition suffer in silence and do not seek help from a health-care professional. The good news: Most sufferers can be helped.

Overactive bladder:

- affects 33 million American men and women

- can result in reclusive behavior

- can be a source of tremendous embarrassment

- can cause recurrent urinary tract infections

- hinders workplace interactions

- limits personal mobility

- can cause skin infections

- may lead to falls and fractures

- may lead to nursing home institutionalization

- is expensive—economic costs exceeded $35 billion in 2008.

Help is available. No one needs to depend on Depends!

If you would like additional information on this topic, or you are interested in having Dr. Neil Baum speak to your group about overactive bladder and other urologic problems, please call (504) 891-8454 or write to Dr. Baum at [email protected].

Don’t overlook support groups and group appointments

Conducting a support group is an excellent way to target a specific diagnosis or disease state. If you can identify women who have a chronic problem, such as pelvic pain, incontinence, or endometriosis, and invite them to a meeting, you’ll find that they appreciate your interest and expertise and often become patients in your practice. Women who attend these meetings get to know who you are, what you do, and where to find you.

Start by organizing your current patients. I have discovered that it is easiest to start with patients in your own practice when organizing these meetings. These women know others with similar problems and soon invite them to your group.

How to start a support group

Choose a date for your meeting. Keep the following in mind:

- Select a date 2 or 3 months in the future. Decide on several possible alternative dates as well. Don’t choose a date near a major holiday. Because I practice in New Orleans, for example, I would never pick a date a week before or after Mardi Gras.

- Tuesday and Wednesday evenings are the best nights of the week. Most people do not schedule social engagements during the middle of the week.

- If your target audience is senior citizens, they may not be able to attend or drive at night. A Saturday morning or weekday afternoon meeting might be better for them.

- At the meeting, provide a sign-in sheet to record the names and email addresses of all who attend. You can use this list to contact attendees later through an online newsletter.

Within 1 week after your support group presentation, send a follow-up email and appropriate additional information to attendees on your sign-in sheet. The letter should thank them for attending and let them know you are available to answer any questions. You can then add their names to your database and contact them periodically when new treatments or diagnostic techniques become available.

Ethnic communities require special attention

With so many different ethnicities in many US metropolitan areas, you may have an opportunity to attract new patients from these groups. If possible, try to learn to speak the language of the ethnic group you primarily serve—you will have an advantage in attracting foreign-born immigrants if you can speak their language. Alternatively, you can serve their needs by having someone on staff who can translate for you.

Be aware, however, that professional medical interpreters recommend employing a trained medical professional to manage the translation. Without specific training in the language and familiarity with the nuances of translating during a medical examination, diagnostic cues and treatment recommendations may be missed or misinterpreted.

Some translation services specialize in medical translation. You can contact the service and request a translator in nearly any language, including Vietnamese, Russian, Serbian, and Afrikaans, and they will arrange for a translator to arrive at a designated time. The fees are reasonable, and using such a service ensures that you can communicate with patients when neither you nor a staffer speaks the language.

It is still a good idea for you to learn some basic vocabulary, such as greetings, farewells, and the names of body parts. Not only will this make diagnoses more efficient, it will make your patients feel welcome.

Provide translations of your educational materials for patients who are more comfortable with a language besides English. If these materials are not already available from pharmaceutical or medical manufacturing companies, have the most frequently used information translated. The nearest university or college might be a good resource. The language departments at these institutions often can refer you to people who do translations on a freelance basis.

Be sure to add information to your Web site and other social media that makes it clear that you accept patients who speak other languages.

Consider writing articles for lay publications

How many referrals or new patients do you get from articles you have written for professional journals?

There is a good chance that your answer is the same as mine: “None.”

My CV lists nearly 175 articles that have been published in peer-reviewed professional journals, but I have not seen a single referral or new patient as a result. However, I have written several hundred articles for local newspapers and magazines that have generated hundreds of new patient visits to my practice.

Become a media resource: Write, be proactive, be responsive

By writing articles for the local press, you can easily become a media resource. Reporters and editors will notice your pieces. Often they will contact you for articles or ask you for quotations to be included in articles they are writing. If you are responsive, they will keep you in their database as an expert to call on whenever your specialty is in the news.

You can promote this transition yourself. When Whoopi Goldberg shared her experience with urinary incontinence on the television talk show The View, I contacted my local paper, the Times-Picayune, and offered to provide information about the problems of incontinence and overactive bladder and how an outpatient evaluation can often lead to cure of this disease.

What should you write about?

Topics of interest to lay readers in your community undoubtedly include wellness, menopause, cancer prevention, female sexual dysfunction, and vaginal rejuvenation. You can create an interesting article about new procedures, new treatments, a unique case with an excellent result, or the use of new technologies, such as new in-office procedures for permanent contraception.

Like medical skills, writing skills can be learned and polished. The more you do it, the better you get. The better you get, the more women you will attract to your practice.

Use your Web site to attract new patients

For most ObGyns, the majority of patients they serve come from within their community. A clinician’s service area usually encompasses no more than three to five zip codes or a 25- to 50-mile radius. All of us enjoy seeing a patient who has traveled more than 100 miles to see us for a gynecologic problem. Imagine the excitement when a patient from 1,000, 5,000, or even 10,000 miles away contacts your office for an appointment. This is exactly what a Web site can do for you and your practice. (Note: In a future article, I will focus on Internet marketing.)

Blogging offers an opportunity to engage potential patients

If you have a Web site, then you’ve already taken the most critical step toward marketing your practice in an increasingly Internet-savvy age. Today’s patients rely on the Internet for personal health information; they also expect a level of interaction and communication from their clinician on the Web. That’s because popular social media platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, are growing rapidly, enabling patients to use a variety of social media resources for support, education, and treatment decisions. A static Web site that consists only of your practice name, staff biographies, your office address and phone numbers, and a map to guide patients to your practice won’t cut it any longer in terms of patient expectations.

Health-care practitioners are just beginning to embrace social media—Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and blogging—as an important component of their Internet marketing strategy. Blogging is easy, quick, and free. In many cases, a blog already is integrated with the rest of your professionally designed Web site. To get started, you just need to contribute content to the blog.

Although a blog won’t deliver an instant return on investment, it can, with time, build awareness of your practice and help promote your services to existing and potential patients. Blogs are driven by content, and a blog tied to your practice gives you the freedom to write and publish content that is unique to you and your practice. Written effectively, blogs present the perfect opportunity to interact with your patients while promoting your services.

Blogs also can improve your search engine ranking significantly. By adding new content to your blog on a regular basis, you ensure that search engines “crawl” your site more often. More important, blogs make it possible to dually publish content on other social media sites, functioning as the nucleus of your social media maintenance. Regular posts to your blog can be synced with your Facebook and Twitter accounts for seamless social networking.

Choose a snappy headline

Few patients will read a blog post with a headline that doesn’t entice them in some way. A compelling headline is essential to get your visitor to read the rest of the article and revisit your blog for new posts in the future.

Think of your blog title as a billboard. Consider that you are trying to attract the attention of drivers who have only a few seconds to look at your signage. The same is true for the title of your blog. Visitors often read the title and make a decision about whether to read the rest of the content. For example, an article entitled “Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence” probably would not get the eyeballs to stick, compared with a headline like “You don’t have to depend on Depends!” Doctors tend to think conservatively and may generate bland titles more suitable for a medical journal. I suggest that you think more like a tabloid journalist to attract readers to your blog.

Keep blog posts lay-friendly

Because patients will be reading your blog, remember to write for them and not for your colleagues. Be conversational and avoid overusing medical terminology that your readers won’t appreciate or understand. Try to target your writing to the 10th grade level so that you attract both educated and less educated readers. Some blog sites evaluate your writing to determine its grade level and will assist you in keeping your material understandable by most readers.

For example, Writing Sample Analyzer uses syllable counts and sentence length to determine the average grade level of your material (http://sarahktyler.com/code/sam ple.php). And the Readability Calculator at http://www.online-utility.org/english/readability_test_and_improve.jsp is also useful. In general, these tools penalize writers for polysyllabic words and long, complex sentences. Your writing will score higher when you use simpler diction and write short sentences.

Educate, rather than advertise.

Blogs should be used to support your online marketing efforts and provide patients with important information about your practice and services. A blog is not designed to be an advertising tool. Using it as such a tool will cause readers to lose interest fast. If you think education first, your material will be attractive to readers and they may call your office for an appointment.

Some organizational pointers:

- Avoid lengthy blog posts; they can lose reader interest. Pages with a lot of white space are easier to scan and more likely to keep patients reading. Say enough to get your point across, but don’t lose your readers’ attention with irrelevant information.

- Include subheadings and bullet points every few paragraphs so readers can quickly browse your post for the information they want.

Provide fresh, unique content that is new and interesting. Offer advice and tips for improved health, and inform patients about new technology and treatments that are specific to your practice. For example, if you offer a noninvasive approach to a medical problem using a procedure that is new in your community, write a post on this topic and include a testimonial from one of your treated patients. This strategy is very effective at generating new patients.

Don’t let your content get stale

Post to your blog regularly, providing new and updated content. Once you develop an audience, keep them coming back by adhering to a schedule. Every update you make to your blog counts as fresh content—a significant factor search engines use to rank Web sites. I suggest that you consider blogging at a minimum of once a week.

We are in the age of social media. The social media train is leaving the station, and you better get on board. The easiest way to start is by creating and posting regularly on your blog site.

External marketing to attract new patients to your ObGyn practice basically consists of writing and speaking. If you want to market outside your practice, you need to think about putting your writing and speaking skills into action. So, speak up and get your pen or computer working!

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CLICK HERE to access recent articles on managing your ObGyn practice.

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 3: Obtain and maintain physician referrals (June 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

External marketing is nothing more than making potential patients aware of your service and areas of expertise. The public truly does not mind marketing, as long as it believes you are communicating useful information and providing value. Nevertheless, such marketing—getting the word out to the public and potential referring physicians—takes some physicians out of their comfort zone. Some doctors think that marketing is synonymous with advertising.

The truth is, you can make the public aware of your services and expertise in an ethical and professional fashion without spending large amounts of money on advertising or hiring an expensive consultant.

How?

The essence of external marketing is writing, speaking, and making use of the Internet. In this article, I review simple, inexpensive techniques to increase your visibility among your peers and in your community. These techniques do not require additional staff or anything more than minimal assistance from your hospital’s public relations and marketing departments and the creation of a few PowerPoint slides that will hold the attention of your audience. A future article will describe Internet marketing strategies.

Try your hand at public speaking

Few of us are natural-born orators, but if you get started on the speaking circuit and acquire effective skills, you’ll be amazed at the demand for your presentations and the commensurate number of new patients filling your appointment book. When you take your message to the podium, audiences have an opportunity not only to learn more about your medical topic and how it applies to their health and wellness, but also to interact with you before and after the presentation.

Most of us have been asked to give a presentation to a lay audience at some time or another. How many of us have set off with a PowerPoint presentation from a pharmaceutical company that contains information far too technical for a nonmedical audience? Is it any wonder that so few talks motivate new patients to call our practices?

How to get invited to speak at local events

Even if you have a knack for public speaking, you still need to generate invitations for speaking engagements. I systematically contact meeting planners at various churches, service organizations like the Junior League, women’s book clubs, and patient advocacy groups, such as the American Cancer Society and American Diabetes Association. A list of these organizations and clubs can be obtained from the Chamber of Commerce in your community.

When I began public speaking, I created a public relations packet and sent it to meeting planners in the community. The packet contained a brief biography that outlined my credentials, listed organizations or groups to which I have given talks in the past, and provided a few testimonials from previous audience members. I also included a fact sheet (see the box on this page) and several articles on the topic to be covered. The articles were written by me for local outlets or written by others for publication in national magazines or other lay publications.

After I delivered a talk, I hung around to answer questions. I also made sure to have plenty of business cards to hand out, as well as my practice brochure and articles that pertained to the topic I had just presented.

Overactive bladder: You don’t have to depend on Depends!

Overactive bladder is a common disorder that affects millions of American women and men. Most people who have this condition suffer in silence and do not seek help from a health-care professional. The good news: Most sufferers can be helped.

Overactive bladder:

- affects 33 million American men and women

- can result in reclusive behavior

- can be a source of tremendous embarrassment

- can cause recurrent urinary tract infections

- hinders workplace interactions

- limits personal mobility

- can cause skin infections

- may lead to falls and fractures

- may lead to nursing home institutionalization

- is expensive—economic costs exceeded $35 billion in 2008.

Help is available. No one needs to depend on Depends!

If you would like additional information on this topic, or you are interested in having Dr. Neil Baum speak to your group about overactive bladder and other urologic problems, please call (504) 891-8454 or write to Dr. Baum at [email protected].

Don’t overlook support groups and group appointments

Conducting a support group is an excellent way to target a specific diagnosis or disease state. If you can identify women who have a chronic problem, such as pelvic pain, incontinence, or endometriosis, and invite them to a meeting, you’ll find that they appreciate your interest and expertise and often become patients in your practice. Women who attend these meetings get to know who you are, what you do, and where to find you.

Start by organizing your current patients. I have discovered that it is easiest to start with patients in your own practice when organizing these meetings. These women know others with similar problems and soon invite them to your group.

How to start a support group

Choose a date for your meeting. Keep the following in mind:

- Select a date 2 or 3 months in the future. Decide on several possible alternative dates as well. Don’t choose a date near a major holiday. Because I practice in New Orleans, for example, I would never pick a date a week before or after Mardi Gras.

- Tuesday and Wednesday evenings are the best nights of the week. Most people do not schedule social engagements during the middle of the week.

- If your target audience is senior citizens, they may not be able to attend or drive at night. A Saturday morning or weekday afternoon meeting might be better for them.

- At the meeting, provide a sign-in sheet to record the names and email addresses of all who attend. You can use this list to contact attendees later through an online newsletter.

Within 1 week after your support group presentation, send a follow-up email and appropriate additional information to attendees on your sign-in sheet. The letter should thank them for attending and let them know you are available to answer any questions. You can then add their names to your database and contact them periodically when new treatments or diagnostic techniques become available.

Ethnic communities require special attention

With so many different ethnicities in many US metropolitan areas, you may have an opportunity to attract new patients from these groups. If possible, try to learn to speak the language of the ethnic group you primarily serve—you will have an advantage in attracting foreign-born immigrants if you can speak their language. Alternatively, you can serve their needs by having someone on staff who can translate for you.

Be aware, however, that professional medical interpreters recommend employing a trained medical professional to manage the translation. Without specific training in the language and familiarity with the nuances of translating during a medical examination, diagnostic cues and treatment recommendations may be missed or misinterpreted.

Some translation services specialize in medical translation. You can contact the service and request a translator in nearly any language, including Vietnamese, Russian, Serbian, and Afrikaans, and they will arrange for a translator to arrive at a designated time. The fees are reasonable, and using such a service ensures that you can communicate with patients when neither you nor a staffer speaks the language.

It is still a good idea for you to learn some basic vocabulary, such as greetings, farewells, and the names of body parts. Not only will this make diagnoses more efficient, it will make your patients feel welcome.

Provide translations of your educational materials for patients who are more comfortable with a language besides English. If these materials are not already available from pharmaceutical or medical manufacturing companies, have the most frequently used information translated. The nearest university or college might be a good resource. The language departments at these institutions often can refer you to people who do translations on a freelance basis.

Be sure to add information to your Web site and other social media that makes it clear that you accept patients who speak other languages.

Consider writing articles for lay publications

How many referrals or new patients do you get from articles you have written for professional journals?

There is a good chance that your answer is the same as mine: “None.”

My CV lists nearly 175 articles that have been published in peer-reviewed professional journals, but I have not seen a single referral or new patient as a result. However, I have written several hundred articles for local newspapers and magazines that have generated hundreds of new patient visits to my practice.

Become a media resource: Write, be proactive, be responsive

By writing articles for the local press, you can easily become a media resource. Reporters and editors will notice your pieces. Often they will contact you for articles or ask you for quotations to be included in articles they are writing. If you are responsive, they will keep you in their database as an expert to call on whenever your specialty is in the news.

You can promote this transition yourself. When Whoopi Goldberg shared her experience with urinary incontinence on the television talk show The View, I contacted my local paper, the Times-Picayune, and offered to provide information about the problems of incontinence and overactive bladder and how an outpatient evaluation can often lead to cure of this disease.

What should you write about?

Topics of interest to lay readers in your community undoubtedly include wellness, menopause, cancer prevention, female sexual dysfunction, and vaginal rejuvenation. You can create an interesting article about new procedures, new treatments, a unique case with an excellent result, or the use of new technologies, such as new in-office procedures for permanent contraception.

Like medical skills, writing skills can be learned and polished. The more you do it, the better you get. The better you get, the more women you will attract to your practice.

Use your Web site to attract new patients

For most ObGyns, the majority of patients they serve come from within their community. A clinician’s service area usually encompasses no more than three to five zip codes or a 25- to 50-mile radius. All of us enjoy seeing a patient who has traveled more than 100 miles to see us for a gynecologic problem. Imagine the excitement when a patient from 1,000, 5,000, or even 10,000 miles away contacts your office for an appointment. This is exactly what a Web site can do for you and your practice. (Note: In a future article, I will focus on Internet marketing.)

Blogging offers an opportunity to engage potential patients

If you have a Web site, then you’ve already taken the most critical step toward marketing your practice in an increasingly Internet-savvy age. Today’s patients rely on the Internet for personal health information; they also expect a level of interaction and communication from their clinician on the Web. That’s because popular social media platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, are growing rapidly, enabling patients to use a variety of social media resources for support, education, and treatment decisions. A static Web site that consists only of your practice name, staff biographies, your office address and phone numbers, and a map to guide patients to your practice won’t cut it any longer in terms of patient expectations.

Health-care practitioners are just beginning to embrace social media—Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and blogging—as an important component of their Internet marketing strategy. Blogging is easy, quick, and free. In many cases, a blog already is integrated with the rest of your professionally designed Web site. To get started, you just need to contribute content to the blog.

Although a blog won’t deliver an instant return on investment, it can, with time, build awareness of your practice and help promote your services to existing and potential patients. Blogs are driven by content, and a blog tied to your practice gives you the freedom to write and publish content that is unique to you and your practice. Written effectively, blogs present the perfect opportunity to interact with your patients while promoting your services.

Blogs also can improve your search engine ranking significantly. By adding new content to your blog on a regular basis, you ensure that search engines “crawl” your site more often. More important, blogs make it possible to dually publish content on other social media sites, functioning as the nucleus of your social media maintenance. Regular posts to your blog can be synced with your Facebook and Twitter accounts for seamless social networking.

Choose a snappy headline

Few patients will read a blog post with a headline that doesn’t entice them in some way. A compelling headline is essential to get your visitor to read the rest of the article and revisit your blog for new posts in the future.

Think of your blog title as a billboard. Consider that you are trying to attract the attention of drivers who have only a few seconds to look at your signage. The same is true for the title of your blog. Visitors often read the title and make a decision about whether to read the rest of the content. For example, an article entitled “Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence” probably would not get the eyeballs to stick, compared with a headline like “You don’t have to depend on Depends!” Doctors tend to think conservatively and may generate bland titles more suitable for a medical journal. I suggest that you think more like a tabloid journalist to attract readers to your blog.

Keep blog posts lay-friendly

Because patients will be reading your blog, remember to write for them and not for your colleagues. Be conversational and avoid overusing medical terminology that your readers won’t appreciate or understand. Try to target your writing to the 10th grade level so that you attract both educated and less educated readers. Some blog sites evaluate your writing to determine its grade level and will assist you in keeping your material understandable by most readers.

For example, Writing Sample Analyzer uses syllable counts and sentence length to determine the average grade level of your material (http://sarahktyler.com/code/sam ple.php). And the Readability Calculator at http://www.online-utility.org/english/readability_test_and_improve.jsp is also useful. In general, these tools penalize writers for polysyllabic words and long, complex sentences. Your writing will score higher when you use simpler diction and write short sentences.

Educate, rather than advertise.

Blogs should be used to support your online marketing efforts and provide patients with important information about your practice and services. A blog is not designed to be an advertising tool. Using it as such a tool will cause readers to lose interest fast. If you think education first, your material will be attractive to readers and they may call your office for an appointment.

Some organizational pointers:

- Avoid lengthy blog posts; they can lose reader interest. Pages with a lot of white space are easier to scan and more likely to keep patients reading. Say enough to get your point across, but don’t lose your readers’ attention with irrelevant information.

- Include subheadings and bullet points every few paragraphs so readers can quickly browse your post for the information they want.

Provide fresh, unique content that is new and interesting. Offer advice and tips for improved health, and inform patients about new technology and treatments that are specific to your practice. For example, if you offer a noninvasive approach to a medical problem using a procedure that is new in your community, write a post on this topic and include a testimonial from one of your treated patients. This strategy is very effective at generating new patients.

Don’t let your content get stale

Post to your blog regularly, providing new and updated content. Once you develop an audience, keep them coming back by adhering to a schedule. Every update you make to your blog counts as fresh content—a significant factor search engines use to rank Web sites. I suggest that you consider blogging at a minimum of once a week.

We are in the age of social media. The social media train is leaving the station, and you better get on board. The easiest way to start is by creating and posting regularly on your blog site.

External marketing to attract new patients to your ObGyn practice basically consists of writing and speaking. If you want to market outside your practice, you need to think about putting your writing and speaking skills into action. So, speak up and get your pen or computer working!

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CLICK HERE to access recent articles on managing your ObGyn practice.

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 3: Obtain and maintain physician referrals (June 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

External marketing is nothing more than making potential patients aware of your service and areas of expertise. The public truly does not mind marketing, as long as it believes you are communicating useful information and providing value. Nevertheless, such marketing—getting the word out to the public and potential referring physicians—takes some physicians out of their comfort zone. Some doctors think that marketing is synonymous with advertising.

The truth is, you can make the public aware of your services and expertise in an ethical and professional fashion without spending large amounts of money on advertising or hiring an expensive consultant.

How?

The essence of external marketing is writing, speaking, and making use of the Internet. In this article, I review simple, inexpensive techniques to increase your visibility among your peers and in your community. These techniques do not require additional staff or anything more than minimal assistance from your hospital’s public relations and marketing departments and the creation of a few PowerPoint slides that will hold the attention of your audience. A future article will describe Internet marketing strategies.

Try your hand at public speaking

Few of us are natural-born orators, but if you get started on the speaking circuit and acquire effective skills, you’ll be amazed at the demand for your presentations and the commensurate number of new patients filling your appointment book. When you take your message to the podium, audiences have an opportunity not only to learn more about your medical topic and how it applies to their health and wellness, but also to interact with you before and after the presentation.

Most of us have been asked to give a presentation to a lay audience at some time or another. How many of us have set off with a PowerPoint presentation from a pharmaceutical company that contains information far too technical for a nonmedical audience? Is it any wonder that so few talks motivate new patients to call our practices?

How to get invited to speak at local events

Even if you have a knack for public speaking, you still need to generate invitations for speaking engagements. I systematically contact meeting planners at various churches, service organizations like the Junior League, women’s book clubs, and patient advocacy groups, such as the American Cancer Society and American Diabetes Association. A list of these organizations and clubs can be obtained from the Chamber of Commerce in your community.

When I began public speaking, I created a public relations packet and sent it to meeting planners in the community. The packet contained a brief biography that outlined my credentials, listed organizations or groups to which I have given talks in the past, and provided a few testimonials from previous audience members. I also included a fact sheet (see the box on this page) and several articles on the topic to be covered. The articles were written by me for local outlets or written by others for publication in national magazines or other lay publications.

After I delivered a talk, I hung around to answer questions. I also made sure to have plenty of business cards to hand out, as well as my practice brochure and articles that pertained to the topic I had just presented.

Overactive bladder: You don’t have to depend on Depends!

Overactive bladder is a common disorder that affects millions of American women and men. Most people who have this condition suffer in silence and do not seek help from a health-care professional. The good news: Most sufferers can be helped.

Overactive bladder:

- affects 33 million American men and women

- can result in reclusive behavior

- can be a source of tremendous embarrassment

- can cause recurrent urinary tract infections

- hinders workplace interactions

- limits personal mobility

- can cause skin infections

- may lead to falls and fractures

- may lead to nursing home institutionalization

- is expensive—economic costs exceeded $35 billion in 2008.

Help is available. No one needs to depend on Depends!

If you would like additional information on this topic, or you are interested in having Dr. Neil Baum speak to your group about overactive bladder and other urologic problems, please call (504) 891-8454 or write to Dr. Baum at [email protected].

Don’t overlook support groups and group appointments

Conducting a support group is an excellent way to target a specific diagnosis or disease state. If you can identify women who have a chronic problem, such as pelvic pain, incontinence, or endometriosis, and invite them to a meeting, you’ll find that they appreciate your interest and expertise and often become patients in your practice. Women who attend these meetings get to know who you are, what you do, and where to find you.

Start by organizing your current patients. I have discovered that it is easiest to start with patients in your own practice when organizing these meetings. These women know others with similar problems and soon invite them to your group.

How to start a support group

Choose a date for your meeting. Keep the following in mind:

- Select a date 2 or 3 months in the future. Decide on several possible alternative dates as well. Don’t choose a date near a major holiday. Because I practice in New Orleans, for example, I would never pick a date a week before or after Mardi Gras.

- Tuesday and Wednesday evenings are the best nights of the week. Most people do not schedule social engagements during the middle of the week.

- If your target audience is senior citizens, they may not be able to attend or drive at night. A Saturday morning or weekday afternoon meeting might be better for them.

- At the meeting, provide a sign-in sheet to record the names and email addresses of all who attend. You can use this list to contact attendees later through an online newsletter.

Within 1 week after your support group presentation, send a follow-up email and appropriate additional information to attendees on your sign-in sheet. The letter should thank them for attending and let them know you are available to answer any questions. You can then add their names to your database and contact them periodically when new treatments or diagnostic techniques become available.

Ethnic communities require special attention

With so many different ethnicities in many US metropolitan areas, you may have an opportunity to attract new patients from these groups. If possible, try to learn to speak the language of the ethnic group you primarily serve—you will have an advantage in attracting foreign-born immigrants if you can speak their language. Alternatively, you can serve their needs by having someone on staff who can translate for you.

Be aware, however, that professional medical interpreters recommend employing a trained medical professional to manage the translation. Without specific training in the language and familiarity with the nuances of translating during a medical examination, diagnostic cues and treatment recommendations may be missed or misinterpreted.

Some translation services specialize in medical translation. You can contact the service and request a translator in nearly any language, including Vietnamese, Russian, Serbian, and Afrikaans, and they will arrange for a translator to arrive at a designated time. The fees are reasonable, and using such a service ensures that you can communicate with patients when neither you nor a staffer speaks the language.

It is still a good idea for you to learn some basic vocabulary, such as greetings, farewells, and the names of body parts. Not only will this make diagnoses more efficient, it will make your patients feel welcome.

Provide translations of your educational materials for patients who are more comfortable with a language besides English. If these materials are not already available from pharmaceutical or medical manufacturing companies, have the most frequently used information translated. The nearest university or college might be a good resource. The language departments at these institutions often can refer you to people who do translations on a freelance basis.

Be sure to add information to your Web site and other social media that makes it clear that you accept patients who speak other languages.

Consider writing articles for lay publications

How many referrals or new patients do you get from articles you have written for professional journals?

There is a good chance that your answer is the same as mine: “None.”

My CV lists nearly 175 articles that have been published in peer-reviewed professional journals, but I have not seen a single referral or new patient as a result. However, I have written several hundred articles for local newspapers and magazines that have generated hundreds of new patient visits to my practice.

Become a media resource: Write, be proactive, be responsive

By writing articles for the local press, you can easily become a media resource. Reporters and editors will notice your pieces. Often they will contact you for articles or ask you for quotations to be included in articles they are writing. If you are responsive, they will keep you in their database as an expert to call on whenever your specialty is in the news.

You can promote this transition yourself. When Whoopi Goldberg shared her experience with urinary incontinence on the television talk show The View, I contacted my local paper, the Times-Picayune, and offered to provide information about the problems of incontinence and overactive bladder and how an outpatient evaluation can often lead to cure of this disease.

What should you write about?

Topics of interest to lay readers in your community undoubtedly include wellness, menopause, cancer prevention, female sexual dysfunction, and vaginal rejuvenation. You can create an interesting article about new procedures, new treatments, a unique case with an excellent result, or the use of new technologies, such as new in-office procedures for permanent contraception.

Like medical skills, writing skills can be learned and polished. The more you do it, the better you get. The better you get, the more women you will attract to your practice.

Use your Web site to attract new patients

For most ObGyns, the majority of patients they serve come from within their community. A clinician’s service area usually encompasses no more than three to five zip codes or a 25- to 50-mile radius. All of us enjoy seeing a patient who has traveled more than 100 miles to see us for a gynecologic problem. Imagine the excitement when a patient from 1,000, 5,000, or even 10,000 miles away contacts your office for an appointment. This is exactly what a Web site can do for you and your practice. (Note: In a future article, I will focus on Internet marketing.)

Blogging offers an opportunity to engage potential patients

If you have a Web site, then you’ve already taken the most critical step toward marketing your practice in an increasingly Internet-savvy age. Today’s patients rely on the Internet for personal health information; they also expect a level of interaction and communication from their clinician on the Web. That’s because popular social media platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, are growing rapidly, enabling patients to use a variety of social media resources for support, education, and treatment decisions. A static Web site that consists only of your practice name, staff biographies, your office address and phone numbers, and a map to guide patients to your practice won’t cut it any longer in terms of patient expectations.

Health-care practitioners are just beginning to embrace social media—Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and blogging—as an important component of their Internet marketing strategy. Blogging is easy, quick, and free. In many cases, a blog already is integrated with the rest of your professionally designed Web site. To get started, you just need to contribute content to the blog.

Although a blog won’t deliver an instant return on investment, it can, with time, build awareness of your practice and help promote your services to existing and potential patients. Blogs are driven by content, and a blog tied to your practice gives you the freedom to write and publish content that is unique to you and your practice. Written effectively, blogs present the perfect opportunity to interact with your patients while promoting your services.

Blogs also can improve your search engine ranking significantly. By adding new content to your blog on a regular basis, you ensure that search engines “crawl” your site more often. More important, blogs make it possible to dually publish content on other social media sites, functioning as the nucleus of your social media maintenance. Regular posts to your blog can be synced with your Facebook and Twitter accounts for seamless social networking.

Choose a snappy headline

Few patients will read a blog post with a headline that doesn’t entice them in some way. A compelling headline is essential to get your visitor to read the rest of the article and revisit your blog for new posts in the future.

Think of your blog title as a billboard. Consider that you are trying to attract the attention of drivers who have only a few seconds to look at your signage. The same is true for the title of your blog. Visitors often read the title and make a decision about whether to read the rest of the content. For example, an article entitled “Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence” probably would not get the eyeballs to stick, compared with a headline like “You don’t have to depend on Depends!” Doctors tend to think conservatively and may generate bland titles more suitable for a medical journal. I suggest that you think more like a tabloid journalist to attract readers to your blog.

Keep blog posts lay-friendly

Because patients will be reading your blog, remember to write for them and not for your colleagues. Be conversational and avoid overusing medical terminology that your readers won’t appreciate or understand. Try to target your writing to the 10th grade level so that you attract both educated and less educated readers. Some blog sites evaluate your writing to determine its grade level and will assist you in keeping your material understandable by most readers.

For example, Writing Sample Analyzer uses syllable counts and sentence length to determine the average grade level of your material (http://sarahktyler.com/code/sam ple.php). And the Readability Calculator at http://www.online-utility.org/english/readability_test_and_improve.jsp is also useful. In general, these tools penalize writers for polysyllabic words and long, complex sentences. Your writing will score higher when you use simpler diction and write short sentences.

Educate, rather than advertise.

Blogs should be used to support your online marketing efforts and provide patients with important information about your practice and services. A blog is not designed to be an advertising tool. Using it as such a tool will cause readers to lose interest fast. If you think education first, your material will be attractive to readers and they may call your office for an appointment.

Some organizational pointers:

- Avoid lengthy blog posts; they can lose reader interest. Pages with a lot of white space are easier to scan and more likely to keep patients reading. Say enough to get your point across, but don’t lose your readers’ attention with irrelevant information.

- Include subheadings and bullet points every few paragraphs so readers can quickly browse your post for the information they want.

Provide fresh, unique content that is new and interesting. Offer advice and tips for improved health, and inform patients about new technology and treatments that are specific to your practice. For example, if you offer a noninvasive approach to a medical problem using a procedure that is new in your community, write a post on this topic and include a testimonial from one of your treated patients. This strategy is very effective at generating new patients.

Don’t let your content get stale

Post to your blog regularly, providing new and updated content. Once you develop an audience, keep them coming back by adhering to a schedule. Every update you make to your blog counts as fresh content—a significant factor search engines use to rank Web sites. I suggest that you consider blogging at a minimum of once a week.

We are in the age of social media. The social media train is leaving the station, and you better get on board. The easiest way to start is by creating and posting regularly on your blog site.

External marketing to attract new patients to your ObGyn practice basically consists of writing and speaking. If you want to market outside your practice, you need to think about putting your writing and speaking skills into action. So, speak up and get your pen or computer working!

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CLICK HERE to access recent articles on managing your ObGyn practice.

Drive Change in an ACO

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

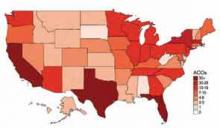

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Should I retire early?

Much has been written of the widespread concern among America’s physicians over upcoming changes in our health care system. Dire predictions of impending doom have prompted many to consider early retirement.

I do not share such concerns, for what that is worth; but if you do, and you are serious about retiring sooner than planned, now would be a great time to take a close look at your financial situation.

Many doctors have a false sense of security about their money; most of us save too little. We either miscalculate or underestimate how much we’ll need to last through retirement.

We tend to live longer than we think we will, and as such we run the risk of outliving our savings. And we don’t face facts about long-term care. Not nearly enough of us have long-term care insurance, or the means to self-fund an extended long-term care situation.

Many people lack a clear idea of where their retirement income will come from, and even when they do, they don’t know how to manage their savings correctly. Doctors in particular are notorious for not understanding investments. Many attempt to manage their practice’s retirement plans with inadequate knowledge of how the investments within their plans work.

So how will you know if you can safely retire before Obamacare gets up to speed? Of course, as with everything else, it depends. But to arrive at any sort of reliable ballpark figure, you’ll need to know three things: (1) how much you realistically expect to spend annually after retirement; (2) how much principal you will need to generate that annual income; and (3) how far your present savings are from that target figure.

An oft-quoted rule of thumb is that in retirement you should plan to spend about 70% of what you are spending now. In my opinion, that’s nonsense. While a few significant expenses, such as disability and malpractice insurance premiums, will be eliminated, other expenses, such as travel, recreation, and medical care (including long-term care insurance, which no one should be without), will increase. My wife and I are assuming we will spend about the same in retirement as we spend now, and I suggest you do too.

Once you know how much money you will spend per year, you can calculate how much money – in interest- and dividend-producing assets – will be needed to generate that amount.

Ideally, you will want to spend only the interest and dividends; by leaving the principal untouched you will never run short, even if you retire at an unusually young age, or longevity runs in your family (or both). Most financial advisers use the 5% rule: You can safely assume a minimum average of 5% annual return on your nest egg. So if you want to spend $100,000 per year, you will need $2 million in assets; for $200,000, you’ll need $4 million.

This is where you may discover – if your present savings are a long way from your target figure – that early retirement is not a realistic option. Better, though, to make that unpleasant discovery now, rather than face the frightening prospect of running out of money at an advanced age. Don’t be tempted to close a wide gap in a hurry with high-return/high-risk investments, which often backfire, leaving you further than ever from retirement.

Of course, it goes without saying that debt can destroy the best-laid retirement plans. If you carry significant debt, pay it off as soon as possible, and certainly before you retire.

Even if you have no plans to retire in the immediate future, it is never too soon to think about retirement. Young physicians often defer contributing to their retirement plans because they want to save for a new house, or college for their children. But there are tangible tax benefits that you get now, because your contributions usually reduce your taxable income, and your investment grows tax-free until you take it out.

For long-term planning, the most foolproof strategy – seldom employed, because it’s boring – is to sock away a fixed amount per month (after your retirement plan has been funded) in a mutual fund. For example, $1,000 per month for 25 years with the market earning 10% overall comes to almost $2 million, with the power of compounded interest working for you.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

Much has been written of the widespread concern among America’s physicians over upcoming changes in our health care system. Dire predictions of impending doom have prompted many to consider early retirement.

I do not share such concerns, for what that is worth; but if you do, and you are serious about retiring sooner than planned, now would be a great time to take a close look at your financial situation.

Many doctors have a false sense of security about their money; most of us save too little. We either miscalculate or underestimate how much we’ll need to last through retirement.

We tend to live longer than we think we will, and as such we run the risk of outliving our savings. And we don’t face facts about long-term care. Not nearly enough of us have long-term care insurance, or the means to self-fund an extended long-term care situation.

Many people lack a clear idea of where their retirement income will come from, and even when they do, they don’t know how to manage their savings correctly. Doctors in particular are notorious for not understanding investments. Many attempt to manage their practice’s retirement plans with inadequate knowledge of how the investments within their plans work.

So how will you know if you can safely retire before Obamacare gets up to speed? Of course, as with everything else, it depends. But to arrive at any sort of reliable ballpark figure, you’ll need to know three things: (1) how much you realistically expect to spend annually after retirement; (2) how much principal you will need to generate that annual income; and (3) how far your present savings are from that target figure.

An oft-quoted rule of thumb is that in retirement you should plan to spend about 70% of what you are spending now. In my opinion, that’s nonsense. While a few significant expenses, such as disability and malpractice insurance premiums, will be eliminated, other expenses, such as travel, recreation, and medical care (including long-term care insurance, which no one should be without), will increase. My wife and I are assuming we will spend about the same in retirement as we spend now, and I suggest you do too.

Once you know how much money you will spend per year, you can calculate how much money – in interest- and dividend-producing assets – will be needed to generate that amount.

Ideally, you will want to spend only the interest and dividends; by leaving the principal untouched you will never run short, even if you retire at an unusually young age, or longevity runs in your family (or both). Most financial advisers use the 5% rule: You can safely assume a minimum average of 5% annual return on your nest egg. So if you want to spend $100,000 per year, you will need $2 million in assets; for $200,000, you’ll need $4 million.

This is where you may discover – if your present savings are a long way from your target figure – that early retirement is not a realistic option. Better, though, to make that unpleasant discovery now, rather than face the frightening prospect of running out of money at an advanced age. Don’t be tempted to close a wide gap in a hurry with high-return/high-risk investments, which often backfire, leaving you further than ever from retirement.

Of course, it goes without saying that debt can destroy the best-laid retirement plans. If you carry significant debt, pay it off as soon as possible, and certainly before you retire.

Even if you have no plans to retire in the immediate future, it is never too soon to think about retirement. Young physicians often defer contributing to their retirement plans because they want to save for a new house, or college for their children. But there are tangible tax benefits that you get now, because your contributions usually reduce your taxable income, and your investment grows tax-free until you take it out.

For long-term planning, the most foolproof strategy – seldom employed, because it’s boring – is to sock away a fixed amount per month (after your retirement plan has been funded) in a mutual fund. For example, $1,000 per month for 25 years with the market earning 10% overall comes to almost $2 million, with the power of compounded interest working for you.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

Much has been written of the widespread concern among America’s physicians over upcoming changes in our health care system. Dire predictions of impending doom have prompted many to consider early retirement.

I do not share such concerns, for what that is worth; but if you do, and you are serious about retiring sooner than planned, now would be a great time to take a close look at your financial situation.

Many doctors have a false sense of security about their money; most of us save too little. We either miscalculate or underestimate how much we’ll need to last through retirement.

We tend to live longer than we think we will, and as such we run the risk of outliving our savings. And we don’t face facts about long-term care. Not nearly enough of us have long-term care insurance, or the means to self-fund an extended long-term care situation.

Many people lack a clear idea of where their retirement income will come from, and even when they do, they don’t know how to manage their savings correctly. Doctors in particular are notorious for not understanding investments. Many attempt to manage their practice’s retirement plans with inadequate knowledge of how the investments within their plans work.

So how will you know if you can safely retire before Obamacare gets up to speed? Of course, as with everything else, it depends. But to arrive at any sort of reliable ballpark figure, you’ll need to know three things: (1) how much you realistically expect to spend annually after retirement; (2) how much principal you will need to generate that annual income; and (3) how far your present savings are from that target figure.

An oft-quoted rule of thumb is that in retirement you should plan to spend about 70% of what you are spending now. In my opinion, that’s nonsense. While a few significant expenses, such as disability and malpractice insurance premiums, will be eliminated, other expenses, such as travel, recreation, and medical care (including long-term care insurance, which no one should be without), will increase. My wife and I are assuming we will spend about the same in retirement as we spend now, and I suggest you do too.

Once you know how much money you will spend per year, you can calculate how much money – in interest- and dividend-producing assets – will be needed to generate that amount.

Ideally, you will want to spend only the interest and dividends; by leaving the principal untouched you will never run short, even if you retire at an unusually young age, or longevity runs in your family (or both). Most financial advisers use the 5% rule: You can safely assume a minimum average of 5% annual return on your nest egg. So if you want to spend $100,000 per year, you will need $2 million in assets; for $200,000, you’ll need $4 million.

This is where you may discover – if your present savings are a long way from your target figure – that early retirement is not a realistic option. Better, though, to make that unpleasant discovery now, rather than face the frightening prospect of running out of money at an advanced age. Don’t be tempted to close a wide gap in a hurry with high-return/high-risk investments, which often backfire, leaving you further than ever from retirement.

Of course, it goes without saying that debt can destroy the best-laid retirement plans. If you carry significant debt, pay it off as soon as possible, and certainly before you retire.