User login

Implementation of ICD-10 codes delayed 1 year

Change has come again to ICD-9 diagnostic codes

Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA (Reimbursement Advisor, November 2011)

Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen G. Sebelius recently announced that the date for compliance with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, diagnosis and procedure codes, or ICD-10, has been changed from October 1, 2013, to October 1, 2014.

Secretary Sebelius noted that the date change has been made in reaction to many providers’ concerns about the administrative burdens they will face in years ahead due to implementation of electronic health records and the Affordable Care Act.1

“ICD-10 codes provide more robust and specific data that will help improve patient care and enable the exchange of our health-care data with that of the rest of the world that has long been using ICD-10. Entities covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) will be required to use the ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes,” said Secretary Sebelius.”1

The final rule was issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and published in the Federal Register on September 5, 2012. The rule states that, “The change in the compliance date is intended to give covered health-care providers and other covered entities more time to prepare and fully test their systems to ensure a smooth and coordinated transition by all covered entities.”2

Adoption will “increase standardization within HIPAA standard transactions and provide a platform for other regulatory and industry initiatives. Their adoption will allow for a higher level of automation for health-care provider offices, particularly for provider processing of billing and insurance related tasks, eligibility responses from health plans, and remittance advice that describes health-care claim payments.”2

Decision based on costs versus savings

HHS is aware that health-care plans, hospitals, and physician practices are currently in the process of implementing the ICD-10 due to the anticipated 2013 compliance date. It is estimated that the 1-year delay may cost the entire health-care industry $1 billion to $6.6 billion. However, HHS also anticipates substantial savings ($3.6 billion to $8 billion) by avoiding costs that could incur if a significant number of providers are unprepared for the transition to ICD-10. Possible consequences of implementing ICD-10 in 2013 are: 1) health-care providers and plans could have to manually process claims for claims to be paid and 2) small health-care providers might have to arrange for loans or lines of credit to continue to provide health-care services because of delayed payments. The decision to delay administration of ICD-10 was based on these factors.3

The American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) will continue to assist the industry through the implementation process. AHIMA CEO Lynne Thomas Gordon, MBA, RHIA, FACHE, CAE, wrote on August 24, 2012, “ICD-10-CM/PCS implementation is inevitable, but today’s news gives the health-care community the certainty and clarity it needs to move forward with implementation, testing, and training. We realize that a few are still apprehensive about the implementation process, and that is why AHIMA remains committed to assisting the health-care community with its transition to a new code set that will lead to improved patient care and reduced costs.”3

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Change has come again to ICD-9 diagnostic codes

Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA (Reimbursement Advisor, November 2011)

Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen G. Sebelius recently announced that the date for compliance with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, diagnosis and procedure codes, or ICD-10, has been changed from October 1, 2013, to October 1, 2014.

Secretary Sebelius noted that the date change has been made in reaction to many providers’ concerns about the administrative burdens they will face in years ahead due to implementation of electronic health records and the Affordable Care Act.1

“ICD-10 codes provide more robust and specific data that will help improve patient care and enable the exchange of our health-care data with that of the rest of the world that has long been using ICD-10. Entities covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) will be required to use the ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes,” said Secretary Sebelius.”1

The final rule was issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and published in the Federal Register on September 5, 2012. The rule states that, “The change in the compliance date is intended to give covered health-care providers and other covered entities more time to prepare and fully test their systems to ensure a smooth and coordinated transition by all covered entities.”2

Adoption will “increase standardization within HIPAA standard transactions and provide a platform for other regulatory and industry initiatives. Their adoption will allow for a higher level of automation for health-care provider offices, particularly for provider processing of billing and insurance related tasks, eligibility responses from health plans, and remittance advice that describes health-care claim payments.”2

Decision based on costs versus savings

HHS is aware that health-care plans, hospitals, and physician practices are currently in the process of implementing the ICD-10 due to the anticipated 2013 compliance date. It is estimated that the 1-year delay may cost the entire health-care industry $1 billion to $6.6 billion. However, HHS also anticipates substantial savings ($3.6 billion to $8 billion) by avoiding costs that could incur if a significant number of providers are unprepared for the transition to ICD-10. Possible consequences of implementing ICD-10 in 2013 are: 1) health-care providers and plans could have to manually process claims for claims to be paid and 2) small health-care providers might have to arrange for loans or lines of credit to continue to provide health-care services because of delayed payments. The decision to delay administration of ICD-10 was based on these factors.3

The American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) will continue to assist the industry through the implementation process. AHIMA CEO Lynne Thomas Gordon, MBA, RHIA, FACHE, CAE, wrote on August 24, 2012, “ICD-10-CM/PCS implementation is inevitable, but today’s news gives the health-care community the certainty and clarity it needs to move forward with implementation, testing, and training. We realize that a few are still apprehensive about the implementation process, and that is why AHIMA remains committed to assisting the health-care community with its transition to a new code set that will lead to improved patient care and reduced costs.”3

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Change has come again to ICD-9 diagnostic codes

Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA (Reimbursement Advisor, November 2011)

Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen G. Sebelius recently announced that the date for compliance with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, diagnosis and procedure codes, or ICD-10, has been changed from October 1, 2013, to October 1, 2014.

Secretary Sebelius noted that the date change has been made in reaction to many providers’ concerns about the administrative burdens they will face in years ahead due to implementation of electronic health records and the Affordable Care Act.1

“ICD-10 codes provide more robust and specific data that will help improve patient care and enable the exchange of our health-care data with that of the rest of the world that has long been using ICD-10. Entities covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) will be required to use the ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes,” said Secretary Sebelius.”1

The final rule was issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and published in the Federal Register on September 5, 2012. The rule states that, “The change in the compliance date is intended to give covered health-care providers and other covered entities more time to prepare and fully test their systems to ensure a smooth and coordinated transition by all covered entities.”2

Adoption will “increase standardization within HIPAA standard transactions and provide a platform for other regulatory and industry initiatives. Their adoption will allow for a higher level of automation for health-care provider offices, particularly for provider processing of billing and insurance related tasks, eligibility responses from health plans, and remittance advice that describes health-care claim payments.”2

Decision based on costs versus savings

HHS is aware that health-care plans, hospitals, and physician practices are currently in the process of implementing the ICD-10 due to the anticipated 2013 compliance date. It is estimated that the 1-year delay may cost the entire health-care industry $1 billion to $6.6 billion. However, HHS also anticipates substantial savings ($3.6 billion to $8 billion) by avoiding costs that could incur if a significant number of providers are unprepared for the transition to ICD-10. Possible consequences of implementing ICD-10 in 2013 are: 1) health-care providers and plans could have to manually process claims for claims to be paid and 2) small health-care providers might have to arrange for loans or lines of credit to continue to provide health-care services because of delayed payments. The decision to delay administration of ICD-10 was based on these factors.3

The American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) will continue to assist the industry through the implementation process. AHIMA CEO Lynne Thomas Gordon, MBA, RHIA, FACHE, CAE, wrote on August 24, 2012, “ICD-10-CM/PCS implementation is inevitable, but today’s news gives the health-care community the certainty and clarity it needs to move forward with implementation, testing, and training. We realize that a few are still apprehensive about the implementation process, and that is why AHIMA remains committed to assisting the health-care community with its transition to a new code set that will lead to improved patient care and reduced costs.”3

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Faulty equipment blamed for improper diagnosis: $78M verdict … and more

AT 36 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. After ultrasonography (US), a nurse told her the fetus had died in utero, but the mother continued to feel fetal movement. The ED physician requested a second US, but it took 75 minutes for a radiology technician to arrive. This US showed a beating fetal heart with placental abruption. After cesarean delivery, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The first US was performed by an inexperienced technician using outdated equipment and the wrong transducer. An experienced technician with newer equipment should have been immediately available. The ED physician did not react when fetal distress was first identified.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ED physician was told that the baby had died. Perhaps the child’s heart had started again by the time the second US was performed and a heartbeat found. The hospital denied negligence.

VERDICT A Pennsylvania jury found the ED physician not negligent; the hospital was 100% at fault. A $78.5 million verdict included $1.5 million in emotional distress to the mother, $10 million in pain and suffering for the child, $2million in lost future earnings, and the rest in future medical expenses.

Ligated ureter found after hysterectomy

A 50-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. She went to the ED with pain 6 days later. Imaging studies indicated a ligated ureter; a nephrostomy tube was placed. She required a nephrostomy bag for 4 months and underwent two repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The patient’s ureter was ligated and/or constricted during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in failing to recognize and repair the injury during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ureter was not ligated during surgery; therefore it could not have been discovered. In addition, injury to a ureter is a known risk of the procedure.

VERDICT An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

Myomectomy after cesarean; mother dies

IMMEDIATELY AFTER A WOMAN with preeclampsia had a cesarean delivery, she underwent a myomectomy. The day before discharge, her abdominal incision opened and a clear liquid drained. The day after discharge, she went to the ED with intense abdominal pain. Necrotizing fasciitis was found and debridement surgery performed. She was transferred to another hospital but died of sepsis several days later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The infection occurred because the myomectomy was performed immediately following cesarean delivery. Prophylactic antibiotics were not prescribed before surgery. The mother was not fully informed as to the risks of concurrent operations. The ObGyns failed to recognize the infection before discharging the patient.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of the risks of surgery; it was reasonable to perform myomectomy immediately following cesarean delivery. There were no signs or symptoms of infection before discharge. Cesarean incisions open about 30% of the time—not a cause for concern. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean procedures are not standard of care. The patient’s infection was caused by a rapidly spreading, rare bacterium.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

TOLAC to cesarean: baby has cerebral palsy

A WOMAN WANTED A TRIAL OF LABOR after a previous cesarean delivery (TOLAC). During labor, fetal distress was noted, and a cesarean delivery was performed. Uterine rupture had occurred. The baby has spastic cerebral palsy with significantly impaired neuromotor and cognitive abilities.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The hospital staff and physicians overlooked earlier fetal distress. A timelier delivery would have prevented the child’s injuries.

DEFENDANTs’ DEFENSE The hospital reached a confidential settlement. The ObGyns claimed fetal tracings were not suggestive of uterine rupture; they met the standard of care.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

WHEN GESTATIONAL DIABETES WAS DIAGNOSED at 33 weeks’ gestation, a family practitioner (FP) referred the mother to an ObGyn practice. Two ObGyns performed amniocentesis to check fetal lung maturity. After the procedure, fetal distress was noted, and the ObGyns instructed the FP to induce labor.

The baby suffered brain damage, had seizures, and has cerebral palsy. She was born without kidney function. By age 10, she had 2 kidney transplant operations and functions at a pre-kindergarten level.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The mother was not fully informed of the risks of and alternatives to amniocentesis. Although complications arose before amniocentesis, the test proceeded. The ObGyns were negligent in not performing cesarean delivery when fetal distress was detected.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The FP and hospital settled prior to trial. The ObGyns claimed that their care was an appropriate alternative to the actions the patient claimed should have been taken.

VERDICT Costs for the child’s care had reached $1.4 million before trial. A $9 million Virginia verdict was returned that included $7 million for the child and $2 million for the mother, but the settlement was reduced by the state cap.

Did HT cause breast cancer?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was prescribed conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate (Prempro, Wyeth, Inc.) for hormone therapy by her gynecologist.

After taking the drug for 5 years, the patient developed invasive breast cancer. She underwent a lumpectomy, chemotherapy, and three reconstructive surgeries.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The manufacturer failed to warn of a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer while taking the product.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Prempro alone does not cause cancer. The drug is just one of many contributing factors that may or may not increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

VERDICT A $3.75 million Connecticut verdict was returned for the patient plus $250,000 to her husband for loss of consortium.

Failure to diagnose preeclampsia—twice

AT 28 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman with a history of hypertension went to an ED with headache, nausea, vomiting, cramping, and ringing in her ears. After waiting 4 hours before being seen, her BP was 150/108 mm Hg and normal fetal heart tones were heard. The ED physician diagnosed otitis media and discharged her.

Later that evening, the patient returned to the ED with similar symptoms. A urine specimen showed significant proteinuria and the fetal heart rate was 158 bpm. A second ED physician diagnosed a urinary tract infection, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, and sent her home.

A few hours later, she returned to the ED by ambulance suffering from eclamptic seizures. Her BP was 174/121 mm Hg, and no fetal heart tones were heard. She delivered a stillborn child by cesarean delivery.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians were negligent in failing to diagnose preeclampsia at the first two visits.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The first ED physician settled for $45,000 while serving a prison sentence after conviction on two sex-abuse felonies related to his treatment of female patients at the same ED. The second ED physician denied negligence.

VERDICT A $50,000 Alabama verdict was returned for compensatory damages for the mother and $600,000 punitive damages for the stillborn child.

Inflated Foley catheter injures mother

DURING A LONG AND DIFFICULT LABOR, an ObGyn used forceps to complete delivery of a 31-year-old woman’s first child. The baby was healthy, but the mother has suffered urinary incontinence since delivery. Despite several repair operations, the condition remains.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to remove a fully inflated Foley catheter before beginning delivery, leading to a urethral sphincter injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The decision regarding removal of the catheter was a matter of hospital policy. The ObGyn blamed improper catheter placement on the nurses.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

AT 36 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. After ultrasonography (US), a nurse told her the fetus had died in utero, but the mother continued to feel fetal movement. The ED physician requested a second US, but it took 75 minutes for a radiology technician to arrive. This US showed a beating fetal heart with placental abruption. After cesarean delivery, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The first US was performed by an inexperienced technician using outdated equipment and the wrong transducer. An experienced technician with newer equipment should have been immediately available. The ED physician did not react when fetal distress was first identified.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ED physician was told that the baby had died. Perhaps the child’s heart had started again by the time the second US was performed and a heartbeat found. The hospital denied negligence.

VERDICT A Pennsylvania jury found the ED physician not negligent; the hospital was 100% at fault. A $78.5 million verdict included $1.5 million in emotional distress to the mother, $10 million in pain and suffering for the child, $2million in lost future earnings, and the rest in future medical expenses.

Ligated ureter found after hysterectomy

A 50-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. She went to the ED with pain 6 days later. Imaging studies indicated a ligated ureter; a nephrostomy tube was placed. She required a nephrostomy bag for 4 months and underwent two repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The patient’s ureter was ligated and/or constricted during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in failing to recognize and repair the injury during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ureter was not ligated during surgery; therefore it could not have been discovered. In addition, injury to a ureter is a known risk of the procedure.

VERDICT An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

Myomectomy after cesarean; mother dies

IMMEDIATELY AFTER A WOMAN with preeclampsia had a cesarean delivery, she underwent a myomectomy. The day before discharge, her abdominal incision opened and a clear liquid drained. The day after discharge, she went to the ED with intense abdominal pain. Necrotizing fasciitis was found and debridement surgery performed. She was transferred to another hospital but died of sepsis several days later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The infection occurred because the myomectomy was performed immediately following cesarean delivery. Prophylactic antibiotics were not prescribed before surgery. The mother was not fully informed as to the risks of concurrent operations. The ObGyns failed to recognize the infection before discharging the patient.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of the risks of surgery; it was reasonable to perform myomectomy immediately following cesarean delivery. There were no signs or symptoms of infection before discharge. Cesarean incisions open about 30% of the time—not a cause for concern. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean procedures are not standard of care. The patient’s infection was caused by a rapidly spreading, rare bacterium.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

TOLAC to cesarean: baby has cerebral palsy

A WOMAN WANTED A TRIAL OF LABOR after a previous cesarean delivery (TOLAC). During labor, fetal distress was noted, and a cesarean delivery was performed. Uterine rupture had occurred. The baby has spastic cerebral palsy with significantly impaired neuromotor and cognitive abilities.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The hospital staff and physicians overlooked earlier fetal distress. A timelier delivery would have prevented the child’s injuries.

DEFENDANTs’ DEFENSE The hospital reached a confidential settlement. The ObGyns claimed fetal tracings were not suggestive of uterine rupture; they met the standard of care.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

WHEN GESTATIONAL DIABETES WAS DIAGNOSED at 33 weeks’ gestation, a family practitioner (FP) referred the mother to an ObGyn practice. Two ObGyns performed amniocentesis to check fetal lung maturity. After the procedure, fetal distress was noted, and the ObGyns instructed the FP to induce labor.

The baby suffered brain damage, had seizures, and has cerebral palsy. She was born without kidney function. By age 10, she had 2 kidney transplant operations and functions at a pre-kindergarten level.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The mother was not fully informed of the risks of and alternatives to amniocentesis. Although complications arose before amniocentesis, the test proceeded. The ObGyns were negligent in not performing cesarean delivery when fetal distress was detected.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The FP and hospital settled prior to trial. The ObGyns claimed that their care was an appropriate alternative to the actions the patient claimed should have been taken.

VERDICT Costs for the child’s care had reached $1.4 million before trial. A $9 million Virginia verdict was returned that included $7 million for the child and $2 million for the mother, but the settlement was reduced by the state cap.

Did HT cause breast cancer?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was prescribed conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate (Prempro, Wyeth, Inc.) for hormone therapy by her gynecologist.

After taking the drug for 5 years, the patient developed invasive breast cancer. She underwent a lumpectomy, chemotherapy, and three reconstructive surgeries.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The manufacturer failed to warn of a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer while taking the product.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Prempro alone does not cause cancer. The drug is just one of many contributing factors that may or may not increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

VERDICT A $3.75 million Connecticut verdict was returned for the patient plus $250,000 to her husband for loss of consortium.

Failure to diagnose preeclampsia—twice

AT 28 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman with a history of hypertension went to an ED with headache, nausea, vomiting, cramping, and ringing in her ears. After waiting 4 hours before being seen, her BP was 150/108 mm Hg and normal fetal heart tones were heard. The ED physician diagnosed otitis media and discharged her.

Later that evening, the patient returned to the ED with similar symptoms. A urine specimen showed significant proteinuria and the fetal heart rate was 158 bpm. A second ED physician diagnosed a urinary tract infection, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, and sent her home.

A few hours later, she returned to the ED by ambulance suffering from eclamptic seizures. Her BP was 174/121 mm Hg, and no fetal heart tones were heard. She delivered a stillborn child by cesarean delivery.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians were negligent in failing to diagnose preeclampsia at the first two visits.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The first ED physician settled for $45,000 while serving a prison sentence after conviction on two sex-abuse felonies related to his treatment of female patients at the same ED. The second ED physician denied negligence.

VERDICT A $50,000 Alabama verdict was returned for compensatory damages for the mother and $600,000 punitive damages for the stillborn child.

Inflated Foley catheter injures mother

DURING A LONG AND DIFFICULT LABOR, an ObGyn used forceps to complete delivery of a 31-year-old woman’s first child. The baby was healthy, but the mother has suffered urinary incontinence since delivery. Despite several repair operations, the condition remains.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to remove a fully inflated Foley catheter before beginning delivery, leading to a urethral sphincter injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The decision regarding removal of the catheter was a matter of hospital policy. The ObGyn blamed improper catheter placement on the nurses.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

AT 36 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. After ultrasonography (US), a nurse told her the fetus had died in utero, but the mother continued to feel fetal movement. The ED physician requested a second US, but it took 75 minutes for a radiology technician to arrive. This US showed a beating fetal heart with placental abruption. After cesarean delivery, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The first US was performed by an inexperienced technician using outdated equipment and the wrong transducer. An experienced technician with newer equipment should have been immediately available. The ED physician did not react when fetal distress was first identified.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ED physician was told that the baby had died. Perhaps the child’s heart had started again by the time the second US was performed and a heartbeat found. The hospital denied negligence.

VERDICT A Pennsylvania jury found the ED physician not negligent; the hospital was 100% at fault. A $78.5 million verdict included $1.5 million in emotional distress to the mother, $10 million in pain and suffering for the child, $2million in lost future earnings, and the rest in future medical expenses.

Ligated ureter found after hysterectomy

A 50-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. She went to the ED with pain 6 days later. Imaging studies indicated a ligated ureter; a nephrostomy tube was placed. She required a nephrostomy bag for 4 months and underwent two repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The patient’s ureter was ligated and/or constricted during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in failing to recognize and repair the injury during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ureter was not ligated during surgery; therefore it could not have been discovered. In addition, injury to a ureter is a known risk of the procedure.

VERDICT An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

Myomectomy after cesarean; mother dies

IMMEDIATELY AFTER A WOMAN with preeclampsia had a cesarean delivery, she underwent a myomectomy. The day before discharge, her abdominal incision opened and a clear liquid drained. The day after discharge, she went to the ED with intense abdominal pain. Necrotizing fasciitis was found and debridement surgery performed. She was transferred to another hospital but died of sepsis several days later.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The infection occurred because the myomectomy was performed immediately following cesarean delivery. Prophylactic antibiotics were not prescribed before surgery. The mother was not fully informed as to the risks of concurrent operations. The ObGyns failed to recognize the infection before discharging the patient.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of the risks of surgery; it was reasonable to perform myomectomy immediately following cesarean delivery. There were no signs or symptoms of infection before discharge. Cesarean incisions open about 30% of the time—not a cause for concern. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean procedures are not standard of care. The patient’s infection was caused by a rapidly spreading, rare bacterium.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

TOLAC to cesarean: baby has cerebral palsy

A WOMAN WANTED A TRIAL OF LABOR after a previous cesarean delivery (TOLAC). During labor, fetal distress was noted, and a cesarean delivery was performed. Uterine rupture had occurred. The baby has spastic cerebral palsy with significantly impaired neuromotor and cognitive abilities.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The hospital staff and physicians overlooked earlier fetal distress. A timelier delivery would have prevented the child’s injuries.

DEFENDANTs’ DEFENSE The hospital reached a confidential settlement. The ObGyns claimed fetal tracings were not suggestive of uterine rupture; they met the standard of care.

VERDICT A Texas defense verdict was returned.

WHEN GESTATIONAL DIABETES WAS DIAGNOSED at 33 weeks’ gestation, a family practitioner (FP) referred the mother to an ObGyn practice. Two ObGyns performed amniocentesis to check fetal lung maturity. After the procedure, fetal distress was noted, and the ObGyns instructed the FP to induce labor.

The baby suffered brain damage, had seizures, and has cerebral palsy. She was born without kidney function. By age 10, she had 2 kidney transplant operations and functions at a pre-kindergarten level.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The mother was not fully informed of the risks of and alternatives to amniocentesis. Although complications arose before amniocentesis, the test proceeded. The ObGyns were negligent in not performing cesarean delivery when fetal distress was detected.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The FP and hospital settled prior to trial. The ObGyns claimed that their care was an appropriate alternative to the actions the patient claimed should have been taken.

VERDICT Costs for the child’s care had reached $1.4 million before trial. A $9 million Virginia verdict was returned that included $7 million for the child and $2 million for the mother, but the settlement was reduced by the state cap.

Did HT cause breast cancer?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was prescribed conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate (Prempro, Wyeth, Inc.) for hormone therapy by her gynecologist.

After taking the drug for 5 years, the patient developed invasive breast cancer. She underwent a lumpectomy, chemotherapy, and three reconstructive surgeries.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The manufacturer failed to warn of a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer while taking the product.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Prempro alone does not cause cancer. The drug is just one of many contributing factors that may or may not increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

VERDICT A $3.75 million Connecticut verdict was returned for the patient plus $250,000 to her husband for loss of consortium.

Failure to diagnose preeclampsia—twice

AT 28 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a woman with a history of hypertension went to an ED with headache, nausea, vomiting, cramping, and ringing in her ears. After waiting 4 hours before being seen, her BP was 150/108 mm Hg and normal fetal heart tones were heard. The ED physician diagnosed otitis media and discharged her.

Later that evening, the patient returned to the ED with similar symptoms. A urine specimen showed significant proteinuria and the fetal heart rate was 158 bpm. A second ED physician diagnosed a urinary tract infection, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, and sent her home.

A few hours later, she returned to the ED by ambulance suffering from eclamptic seizures. Her BP was 174/121 mm Hg, and no fetal heart tones were heard. She delivered a stillborn child by cesarean delivery.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians were negligent in failing to diagnose preeclampsia at the first two visits.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The first ED physician settled for $45,000 while serving a prison sentence after conviction on two sex-abuse felonies related to his treatment of female patients at the same ED. The second ED physician denied negligence.

VERDICT A $50,000 Alabama verdict was returned for compensatory damages for the mother and $600,000 punitive damages for the stillborn child.

Inflated Foley catheter injures mother

DURING A LONG AND DIFFICULT LABOR, an ObGyn used forceps to complete delivery of a 31-year-old woman’s first child. The baby was healthy, but the mother has suffered urinary incontinence since delivery. Despite several repair operations, the condition remains.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to remove a fully inflated Foley catheter before beginning delivery, leading to a urethral sphincter injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The decision regarding removal of the catheter was a matter of hospital policy. The ObGyn blamed improper catheter placement on the nurses.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Women’s health under the Affordable Care Act: What is covered?

Lay midwives and the ObGyn: Is collaboration risky?

(May 2012)

How state budget crises are putting the squeeze on Medicaid (and you)

(February 2012)

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

(October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

with Janelle Yates, Senior Editor (August 2010)

For the first half of 2012, the big question was: Will anything be covered under the Affordable Care Act (ACA)? After considering constitutional challenges to the Act that had the potential to invalidate the entire law, the US Supreme Court ruled, on June 28, that the ACA met constitutional muster in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012).

Now that the Court has upheld the ACA, let’s review the major women’s health services included under the law. This Web version incorporates 10 more women's health provisions from the ACA, from smoking cessation to young women’s breast cancer, that were not in the print version.

Preventive services guaranteed without copays

A major component of the health reform law went into effect August 1, 2012; it requires most health plans to cover women’s preventive services without requiring enrollees to pay a copay or deductibles. This provision reflects Congress’ understanding that women have a longer life expectancy and bear a greater burden of chronic disease, disability, and reproductive and gender-specific conditions. In addition, women often have a different response to treatment than men do.

The federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates that Americans use preventive services at only about half of the recommended rate. By 2013, as many as 73 million individuals will benefit from preventive care offered under the law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) worked with the Institute of Medicine (IOM)—which was charged with advising HHS—to encourage the inclusion of women’s preventive services specified in ACOG guidelines to ensure women’s health and well-being. As ACOG Executive Vice President Hal C. Lawrence, MD, told the IOM in January 2011:

- The College’s clinical guidelines…offer an excellent resource…and encompass the entire field of women’s preventive care. Our guidance is based on the best available evidence and is developed by committees with expertise reflecting the breadth of women’s health care and subject to a rigorous conflict of interest policy.

Dr. Lawrence further urged the IOM “to recommend coverage of the following services and products without cost-sharing”:

- well-woman visits

- preconception care

- family planning counseling and services

- HIV screening (for women at average risk)

- screening for intimate partner violence

- testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) as part of cervical cancer screening.

ACOG’s recommendations were approved by the IOM and, subsequently, by HHS. As a result, all private health plans that began on or after September 30, 2010, are required to cover these services at no out-of-pocket cost to patients (TABLE).

Women’s preventive services guaranteed under ACA*

| Service | Frequency | HHS guidelines for health insurance coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Well-woman visit | Annual for adult women, although HHS recognizes that several visits may be needed to obtain all necessary recommended preventive services, depending on a woman’s health status, health needs, and other risk factors** | The visit should focus on preventive services that are appropriate for the patient’s age and development, including preconception and prenatal care. This visit should, where appropriate, include other preventive services listed in this set of guidelines, as well as others referenced in section 2713 |

| Screening for gestational diabetes | Between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation and at the first prenatal visit for pregnant women identified to be at high risk for diabetes | |

| Testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) | At age 30 and older, no more frequently than every 3 years | High-risk HPV DNA testing in women who have normal cervical cytology |

| Counseling about sexually transmitted infection (STI) | Annual | All sexually active women |

| Counseling about and screening for HIV | Annual | All sexually active women |

| Counseling about and provision of contraception† | As prescribed | All FDA-approved contraceptive methods and sterilization procedures. Counseling for all women with reproductive capacity |

| Breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling | In conjunction with each birth | Comprehensive lactation support and counseling by a trained provider during pregnancy or postpartum (or both), as well as costs for renting breastfeeding equipment |

| Screening for and counseling about interpersonal and domestic violence | Annual | |

| HHS = Health and Human Services * HHS guidelines are effective August 1, 2011. Nongrandfathered plans and insurers are required to provide coverage without cost-sharing consistent with HHS guidelines in the first plan year (in the individual market, policy year) that begins on or after August 1, 2012. ** The July 2011 Institute of Medicine report titled “Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gap” lists recommendations on individual preventive services that may be obtained during a well-woman preventive service visit. † Group health plans sponsored by certain religious employers, and group health insurance coverage in connection with such plans, are exempt from the requirement to cover contraceptive services. SOURCE: Adapted from Healthcare.gov. Affordable Care Act Expands Prevention Coverage for Women’s Health and Well-Being. http://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed August 8, 2012. | ||

Contraceptive mandate triggers a firestorm

On February 10, 2012, under pressure from religious groups, the Obama Administration offered a religious exemption to the contraception mandate for certain employers and group health plans. Under this “accommodation,” certain religious employers are exempt from the requirement to cover contraceptive services in their group health plans. An employer qualifies for this exemption if it:

- has the inculcation of religious values as one of its purposes

- primarily employs individuals who share its religious tenets

- primarily serves individuals who share its religious tenets, and

- qualifies for nonprofit status under

Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules. At the same time that the Obama Administration wanted to accommodate employers’ religious beliefs, it also wanted to ensure that every woman would have access to free preventive care, including contraceptive services, regardless of where she works. And so while the Administration requires insurers to offer group health plan coverage without contraceptive coverage to religious-affiliated organizations, it also requires insurers to provide contraceptive coverage directly to individuals covered under the organization’s group health plan with no cost sharing.

This contraceptive mandate—even with the accommodation—has set off a firestorm on Capitol Hill that will eventually be settled in the courts.

Medicaid expansion falls short of original goal

In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the plaintiffs asked the Supreme Court to rule on the federal government’s authority to require states to expand their Medicaid programs. Medicaid costs are typically shared by the federal and state governments. Under the ACA, state Medicaid programs were required to cover nearly all individuals who have incomes below 133% of the federal poverty level—$30,656 for a family of four in 2012—paid entirely by the federal government from 2014 through 2016. After that, the federal share gradually declines to, and then stays at, 90%. States that did not expand their Medicaid programs risked losing all federal Medicaid funding.

The Court ruled that the federal government can expand Medicaid but can’t penalize states that don’t accept the expansion mandate—effectively turning the mandate into a state option. States will receive the additional federal funds if they expand coverage, but states that don’t expand will not be penalized by losing existing federal funds for other parts of the program.

Since the ruling, a number of governors have announced that they will not expand their Medicaid programs, including governors of Florida and Louisiana. Those two states alone are home to 20% of all individuals intended to be covered under the Medicaid expansion.

This part of the ACA is particularly important to women because it strikes, for the first time, the requirement that a low-income woman must be pregnant to receive Medicaid coverage.

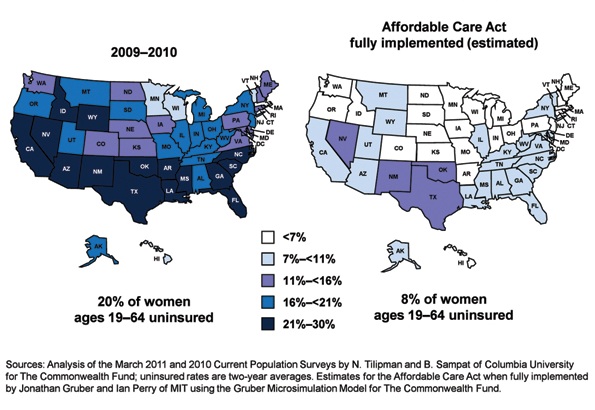

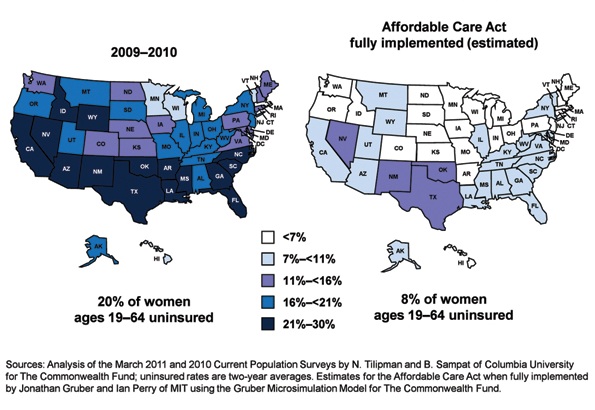

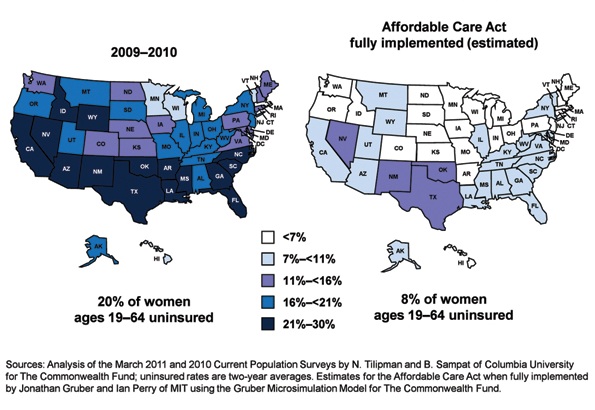

The figure below shows the dramatic potential improvement in coverage for women if all states fully implement the Medicaid expansion. Time, court decisions, elections, and state budget fights will determine how much of this change is realized for women’s health.

Percentage of insured women will increase under ACA

Percentage of women aged 19 to 64 years who were uninsured in 2009–2012 and under the Affordable Care Act when fully implemented.

SOURCE: Commonwealth Fund. Analysis of the March 2011 and 2010 Current Population Surveys by N. Tilipman and B. Sampat of Columbia University.

Women gain direct access to ObGyns

The ACA guarantees women in all states and all plans direct access to their ObGyns. Before the ACA, women in nine states lacked this guarantee, and women in 16 other states had only limited direct access. Now, a woman can go directly to her ObGyn without having to get a referral from her primary care physician or insurer.

Direct access is especially important because the ACA establishes new delivery systems, such as medical homes and accountable care organizations, designed to capture patients to maximize savings. An ObGyn does not have to be the patient’s primary care provider, and the patient’s access to her ObGyn cannot be limited to a certain number of visits or types of services.

ACA encourages states to cover family-planning services

Under the ACA, states have an easier time covering family-planning services, up to the same eligibility levels as pregnant women. Family planning is still an optional service that a state can choose to extend to women who have incomes above the Medicaid income eligibility level but, before the ACA was enacted, states had to apply to HHS for permission to waive the federal rules, often a very cumbersome process.

Prior to the ACA, 27 states had family planning waivers to provide services to nonpregnant women who had incomes above the Medicaid eligibility level—most at or near 200% of poverty. Now, states can provide family planning services to this population without federal approval.

Don’t miss Dr. Robert L. Barbieri’s October article titled “Gynecologic care across a woman’s life”

Insurance reforms end lifetime limits on coverage

Insurance reforms are important to us and our patients. The better the private health insurance system works—allowing us to provide our best possible care to patients and making sure they can see us when they need our care—the less our nation relies on the public safety net.

Beginning in 2010, the ACA eliminated all lifetime limits on how much insurance companies would cover when beneficiaries get sick; it also bans insurance companies from dropping people from coverage when they get sick. So if your patient has private health insurance and has faithfully paid her premiums and hasn’t committed fraud, her insurer cannot drop her or impose a limit on her coverage once she claims benefits.

This may be especially important for patients who need the most care, such as those who have cancer or another long-term, expensive, and unforeseen diagnosis. Because of this provision, you will not have to worry about your patient losing coverage in the middle of a long course of treatment.

The insurance practice of charging women more than men for equivalent policies ended on January 1, 2011, making insurance more affordable for our patients. Insurers in the individual and small group markets are allowed to vary premiums only for age, geographic location, family size, and tobacco use, not for gender—another important aspect of the law.

2014 is a key year in health reform

Exchanges begin

In 2014, under the ACA, state health insurance exchanges become reality.

An exchange is a marketplace where people can shop for health insurance; private health insurers can market their insurance products in state and multistate exchanges if they comply with new federal insurance reforms established in the ACA and offer the minimum benefits packages established by each state. Exchanges are intended to offer patients a choice of health insurance plans that are affordable, comprehensive, and easy to compare. Low-income individuals will be able to purchase private insurance in the exchanges with the federal premium subsidies or tax credits.

Insurers wanting to market their policies in an exchange may not deny coverage for preexisting conditions, including pregnancy, domestic violence, and previous cesarean delivery. They can’t deny coverage on the basis of an individual’s medical history, health status, genetic information, or disability. And they can’t impose waiting periods longer than 90 days before coverage takes effect, including 9-month waiting periods before maternity coverage.

Essential benefits are established

The ACA sets a minimum standard of health-care coverage that must be included in nearly every private insurance policy. The intent is that every person in the United States, regardless of where they live, who employs them, and what their income is, should have access to the same basic care.

Effective January 1, 2014, all insurance plans, except plans that existed before the ACA was enacted on March 23, 2010, must offer an “essential health benefits” (EHB) package, which must include:

- ambulatory patient services

- emergency services

- hospitalization

- maternity and newborn care

- mental health and substance use disorder services

- prescription drugs

- rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices

- laboratory services

- women’s preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

- pediatric services, including oral and vision care.

Last December, HHS surprised many by giving states flexibility to design their own EHB packages, as long as the packages included each service on the list.

To choose its EHB package, a state must select a “benchmark” plan from the top- selling plans in four markets: federal and state public employee plans, commercial HMO plans, and small business plans. If a state doesn’t select a benchmark plan, the EHB defaults to the largest small-group market plan in the state. Each state must also choose an EHB package for its Medicaid program using the same 10 benefit categories.

State EHB plans must follow ACA requirements on annual and lifetime dollar limits but may impose limits on the scope and duration of coverage.

As for state-mandated benefits, if a state selects an EHB package that does not include a benefit already mandated by the state, the state must fund coverage for that service on its own—a decision HHS has promised to revisit in 2016.

Abortion decisions reside with the states

ACA requirements regarding abortion coverage 1) take effect in 2014 and 2) apply only to private health insurance plans marketed in the state exchanges that 3) cover abortions beyond those eligible for Medicaid coverage now, which are those that involve cases of rape or incest or that are necessary to save the life of the mother. Medicaid coverage for these categories of abortion is allowed under the Hyde Amendment.

Each insurer marketing a health plan in an exchange can determine whether or not its plan will cover abortion and, if it does, whether coverage will be limited to or go beyond those allowed under the Hyde Amendment. No federal tax or premium subsidies may be used to pay for abortions beyond those permitted by the Hyde Amendment.

The Secretary of HHS must ensure that at least one plan in each state exchange covers abortion, and that at least one plan either covers no abortions or limits abortions to those allowed under the Hyde Amendment. Insurers who offer abortion coverage beyond Hyde have to comply with a number of administrative requirements.

Congress was clear that the ultimate decisions about abortion should be made at the state rather than the federal level, and it gave states the ultimate trump card: Any state can pass legislation that prohibits any plan from offering abortion coverage of any kind within that state’s exchange. Any state can prohibit insurers offering plans within that state’s exchange from including any abortion coverage.

10 additional health provisions under the ACA

1. Creation of women's medical homes

The law points the way for creation of medical homes for women in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. The bill establishes an Innovation Center within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that has broad authority to evaluate, test, and adopt systems that foster patient-centered care, improve quality, and contain costs under Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)—and this includes patient-centered medical homes that address women’s unique health needs. ObGyn practices are eligible to participate and to receive additional reimbursement if they do.

2. Smoking-cessation counseling in pregnancy

The framers of the ACA recognized the large negative impact that smoking has on health, especially during pregnancy. Studies suggest that the intervention of a physician—most notably, counseling of the patient to quit smoking—has strong potential to modify this behavior. The new law provides reimbursement for this intervention. There are no copays or deductibles for patients, and smoking-cessation services can include diagnostic, therapeutic, and counseling modalities in addition to prescription of pharmacotherapy.

Before this bill became law, only 24 state Medicaid programs paid ObGyns or other physicians for smoking-cessation counseling of pregnant patients, and five states provided no coverage at all. Now, all pregnant Medicaid patients can get this counseling, and you’ll be paid for this important service.

3. Payments to nonphysician providers in freestanding birth centers

Before the ACA became law, Medicaid was authorized to pay hospitals and other facilities operated by and under the supervision of a physician; no payments were authorized for services of an ambulatory center operated by other health professionals. The ACA authorizes Medicaid payments to state-recognized freestanding birth centers not operated by or under the supervision of a physician. A state that doesn’t currently license birth centers must pass legislation and license these centers before the centers can receive these payments.

Medicaid will also reimburse providers who practice in state-recognized freestanding birth centers, as long as the individuals are practicing within their state’s scope of practice laws and regulations. Because the type of provider is not specified but instead left up to each state’s scope of practice laws and regulations, this provision could allow for separate provider payments for physicians, certified nurse midwives, certified professional midwives, and doulas.

4. Immigrant coverage

Legal immigrants are bound by the individual coverage mandate and must purchase health insurance. These individuals are eligible for income-related premium credits and subsidies for insurance purchased through an exchange. Legal immigrants who are barred from Medicaid during their first 5 years in the United States (by earlier law) are eligible for premium credits only.

Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Medicaid, premium credits, or subsidies and are barred from purchasing insurance in the exchange, even with their own money.

5. Postpartum depression

Health reform will help bring perinatal and postpartum depression out of the shadows by providing federal funds for research, patient education, and clinical treatment. For example, the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will:

- conduct research into the causes of, and treatments for, postpartum conditions

- create a national public awareness campaign to increase awareness and knowledge of postpartum depression and psychosis

- provide grants to study the benefits of screening for postpartum depression and psychosis

- establish grants to deliver or enhance outpatient, inpatient, and home-based health and support services, including case management and comprehensive treatment services for individuals with, or at risk for, postpartum conditions.

The National Institute of Mental Health is encouraged to conduct a 10-year longitudinal study on the mental health consequences of pregnancy. This study is intended to focus on perinatal depression.

Community health centers will be eligible for grants in 2012 (as they were in 2011) to the tune of $3 million for inpatient and outpatient counseling and services.

And a federal public awareness campaign will educate the public through radio and television ads.

These endeavors point to the need for ObGyns to familiarize themselves with postpartum depression—if they aren’t already well versed in the subject—because patients are likely to become more aware of this issue and look to their ObGyns for answers.

6. Maternal home visits

Congress established a new Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program to improve maternal and fetal health in underserved areas of our country. This program will provide funds to states, tribes, and territories to develop and implement evidence-based home-visitation models to reduce infant and maternal mortality and its causes by producing improvements in:

- prenatal, maternal, and newborn health

- child health and development

- parenting skills

- school readiness

- juvenile delinquency

- family economic self-sufficiency.

These programs will have to demonstrate effectiveness and improved outcomes. HHS recently requested suggestions on ways of demonstrating the effectiveness of home-visiting program models for pregnant women, expectant fathers, and caregivers of children from birth through entry into kindergarten.

The law appropriates $350 million to this program in 2012 and $400 million in both 2013 and 2014.

7. Assistance for pregnant students

A new Pregnancy Assistance Fund—$25 million annually over 10 years (fiscal years 2010–2019)—requires the Secretary of HHS (in collaboration with the Secretary of Education) to establish a state grant program to help pregnant and parenting teens and young women. The aim of this program is to help teens who become pregnant and who choose to bring their pregnancies to term or keep their babies, or both, to stay in school. Grants will go to institutions of higher education, high schools and community service centers, as well as state attorneys general.

Institutions that receive grants must work with providers to meet specific practical needs of pregnant or parenting students:

- housing

- childcare

- parenting education

- postpartum counseling

- assistance in finding and accessing needed services

- referrals for prenatal care and delivery, infant or foster care, or adoption.

Funds to attorneys general will be used to combat domestic violence among pregnant teens.

8. Young women's breast cancer

A new program is intended to help educate young women about the importance of breast health and screening, in two ways:

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) will conduct research to develop and test screening measures for prevention and early detection of breast cancer in women 15 to 44 years old.

- The US Department of HHS will create a national awareness campaign, with $9 million in funding each year from 2010 to 2014, to encourage young women to talk with their doctors about breast cancer and early detection.

ObGyns can expect to see more interest and questions about breast health among young women and their mothers. It pays to be prepared with good information for these important conversations.

9. Personal responsibility education

From 2010 through 2014, each state will receive funds for personal responsibility education programs aimed at reducing pregnancy in youths. Funds are $75 million for each fiscal year, allocated to each state depending on the size of its youth population but not intended to be less than $250,000 per state.

Educational programs eligible for federal funds must include both abstinence and contraception information for prevention of teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS, as well as three or more adulthood-preparation subjects.

10. Community-based support of Patient-Centered Medical Homes

Federal funding is available to states for the development of community-based health teams to support medical homes run by primary care practices. These teams may include specialists, nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, dieticians, social workers, behavioral and mental health providers, and physician assistants. Primary care practices in this program function as medical homes and are responsible for addressing a patient’s personal health-care needs. The team links the medical home to community support services for its patients.

Eligible ObGyn practices can qualify as primary care practices, and ObGyns are eligible to serve as specialist members of the community-based health team.

ACA is a mixed bag for ObGyns

Women have much to gain from the provisions of the ACA. It’s also true that many parts of the law are terrible for practicing ObGyns, including the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) and the absence of meaningful medical liability reform. For more on these issues, see “Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?” which appears in the October 2011 issue of OBG Management (available in the archive at obgmanagement.com). ACOG is committed to working with Congress to repeal or remedy those aspects of the law.

A recent study reveals that almost one-third of physicians are no longer accepting Medicaid patients

If all states expanded Medicaid to cover people with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level in 2014, as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) proposes, 23 million people would become eligible for the program.1

That statistic prompts important questions:

- Would the health-care workforce be able to meet the demand of caring for all these new patients?

- Would it be willing?

A recent analysis of data from 4,326 office-based physicians suggests that the answer to both questions is “No”: Almost one-third of these providers were already declining to accept new Medicaid patients in 2011.2

Although 96% of physicians in the analysis accepted new patients in 2011, the percentage of physicians accepting new patients covered by Medicaid was lower (69%), as was the percentage accepting new self-paying patients (91.7%), patients covered by Medicare (83%), and patients with private insurance (82%).2

Physicians who were in solo practice were 23.5% less likely to accept new Medicaid patients, compared with those who practiced in an office with 10 or more other physicians.2

The data from this study come from the 2011 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Electronic Medical Records Supplement, a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. The survey included questions exploring whether physicians were accepting new patients.2

Earlier studies have found that the low reimbursement levels for care delivered through Medicaid has deterred many physicians from accepting patients.3

The view in the ObGyn specialty

The findings of this analysis were not broken down by specialty—only by primary care versus non–primary care. To get an idea of conditions in the ObGyn specialty, OBG Management surveyed the members of its Virtual Board of Editors (VBE). Of the 117 members contacted, 61 responded—a response rate of 52.1%. Roughly three-quarters (75.4%) reported that they currently treat patients covered by Medicaid, but only 60.7% are accepting new patients covered by Medicaid. Twenty-one percent of respondents reported that they have not and will not accept patients covered by Medicaid.

When asked to comment on their level of satisfaction with Medicaid, the most common response among VBE members was dissatisfaction due to “insufficient reimbursement.”

“I am not satisfied with Medicaid,” commented one VBE member. “The reimbursement is terrible….I have certainly thought of stopping care for Medicaid patients and, if Congress ever allows the big cuts to reimbursement that are threatened every year, I think I would stop.”

Another VBE member reported extreme dissatisfaction with Medicaid because of “lousy” reimbursement. He also pointed to “all the paperwork and crazy regulations that require inordinate time and additional personnel just to handle….and then [the claim] gets denied for reasons beyond reason.” He added that physicians who do accept Medicaid “are on the fast track to sainthood.”

Other reasons for refusing to accept patients with Medicaid (or, if Medicaid was accepted, for high levels of aggravation with the program):

- payment rejections

- too many different categories of coverage “that patients are completely uninformed about”

- difficulty finding a specialist who will manage high-risk patients covered by Medicaid

- red tape

- the complex health problems that Medicaid patients tend to have, compared with patients who have other types of coverage.

One VBE member summed up his feelings in one word: “Phooey.”

Several VBE members suggested that health reform should focus on the Medicaid program.

“These plans are just sucking up the state’s money and paying docs peanuts and their administrators big bucks!” wrote Mary Vanko, MD, of Munster, Indiana.

“I’m tired of how much Medicaid is being abused by people,” commented another VBE member. “People using other people’s cards, people with regular insurance getting Medicaid to cover their copays. The whole system needs reform!”

Some physicians were satisfied with Medicaid

Among the respondents were several who reported being satisfied with the program, including one who called the experience “good” and another who reported being “shielded from the reimbursement issues.”

“I have no problems with Medicaid,” wrote another.

—Janelle Yates, Senior Editor

References

1. Kenney GM, Dubay L, Zuckerman S, Huntress M. Making the Medicaid Expansion an ACA Option: How Many Low-Income Americans Could Remain Uninsured? Washington, DC: Urban Institute Health Policy Center; June 29, 2012. http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412606-Making-the-Medicaid-Expansion-an-ACA-Option.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2012.

2. Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Affairs. 2012;31(8):1673–1679.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. QuickStats: percentage of office-based physicians accepting new patients, by types of payment accepted—United States, 1999–2000 and 2008–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(27):928.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Lay midwives and the ObGyn: Is collaboration risky?

(May 2012)

How state budget crises are putting the squeeze on Medicaid (and you)

(February 2012)

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

(October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

with Janelle Yates, Senior Editor (August 2010)

For the first half of 2012, the big question was: Will anything be covered under the Affordable Care Act (ACA)? After considering constitutional challenges to the Act that had the potential to invalidate the entire law, the US Supreme Court ruled, on June 28, that the ACA met constitutional muster in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012).

Now that the Court has upheld the ACA, let’s review the major women’s health services included under the law. This Web version incorporates 10 more women's health provisions from the ACA, from smoking cessation to young women’s breast cancer, that were not in the print version.

Preventive services guaranteed without copays

A major component of the health reform law went into effect August 1, 2012; it requires most health plans to cover women’s preventive services without requiring enrollees to pay a copay or deductibles. This provision reflects Congress’ understanding that women have a longer life expectancy and bear a greater burden of chronic disease, disability, and reproductive and gender-specific conditions. In addition, women often have a different response to treatment than men do.

The federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates that Americans use preventive services at only about half of the recommended rate. By 2013, as many as 73 million individuals will benefit from preventive care offered under the law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) worked with the Institute of Medicine (IOM)—which was charged with advising HHS—to encourage the inclusion of women’s preventive services specified in ACOG guidelines to ensure women’s health and well-being. As ACOG Executive Vice President Hal C. Lawrence, MD, told the IOM in January 2011:

- The College’s clinical guidelines…offer an excellent resource…and encompass the entire field of women’s preventive care. Our guidance is based on the best available evidence and is developed by committees with expertise reflecting the breadth of women’s health care and subject to a rigorous conflict of interest policy.

Dr. Lawrence further urged the IOM “to recommend coverage of the following services and products without cost-sharing”:

- well-woman visits

- preconception care

- family planning counseling and services

- HIV screening (for women at average risk)

- screening for intimate partner violence

- testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) as part of cervical cancer screening.

ACOG’s recommendations were approved by the IOM and, subsequently, by HHS. As a result, all private health plans that began on or after September 30, 2010, are required to cover these services at no out-of-pocket cost to patients (TABLE).

Women’s preventive services guaranteed under ACA*

| Service | Frequency | HHS guidelines for health insurance coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Well-woman visit | Annual for adult women, although HHS recognizes that several visits may be needed to obtain all necessary recommended preventive services, depending on a woman’s health status, health needs, and other risk factors** | The visit should focus on preventive services that are appropriate for the patient’s age and development, including preconception and prenatal care. This visit should, where appropriate, include other preventive services listed in this set of guidelines, as well as others referenced in section 2713 |

| Screening for gestational diabetes | Between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation and at the first prenatal visit for pregnant women identified to be at high risk for diabetes | |

| Testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) | At age 30 and older, no more frequently than every 3 years | High-risk HPV DNA testing in women who have normal cervical cytology |

| Counseling about sexually transmitted infection (STI) | Annual | All sexually active women |

| Counseling about and screening for HIV | Annual | All sexually active women |

| Counseling about and provision of contraception† | As prescribed | All FDA-approved contraceptive methods and sterilization procedures. Counseling for all women with reproductive capacity |

| Breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling | In conjunction with each birth | Comprehensive lactation support and counseling by a trained provider during pregnancy or postpartum (or both), as well as costs for renting breastfeeding equipment |

| Screening for and counseling about interpersonal and domestic violence | Annual | |

| HHS = Health and Human Services * HHS guidelines are effective August 1, 2011. Nongrandfathered plans and insurers are required to provide coverage without cost-sharing consistent with HHS guidelines in the first plan year (in the individual market, policy year) that begins on or after August 1, 2012. ** The July 2011 Institute of Medicine report titled “Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gap” lists recommendations on individual preventive services that may be obtained during a well-woman preventive service visit. † Group health plans sponsored by certain religious employers, and group health insurance coverage in connection with such plans, are exempt from the requirement to cover contraceptive services. SOURCE: Adapted from Healthcare.gov. Affordable Care Act Expands Prevention Coverage for Women’s Health and Well-Being. http://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed August 8, 2012. | ||

Contraceptive mandate triggers a firestorm

On February 10, 2012, under pressure from religious groups, the Obama Administration offered a religious exemption to the contraception mandate for certain employers and group health plans. Under this “accommodation,” certain religious employers are exempt from the requirement to cover contraceptive services in their group health plans. An employer qualifies for this exemption if it:

- has the inculcation of religious values as one of its purposes

- primarily employs individuals who share its religious tenets

- primarily serves individuals who share its religious tenets, and

- qualifies for nonprofit status under

Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules. At the same time that the Obama Administration wanted to accommodate employers’ religious beliefs, it also wanted to ensure that every woman would have access to free preventive care, including contraceptive services, regardless of where she works. And so while the Administration requires insurers to offer group health plan coverage without contraceptive coverage to religious-affiliated organizations, it also requires insurers to provide contraceptive coverage directly to individuals covered under the organization’s group health plan with no cost sharing.

This contraceptive mandate—even with the accommodation—has set off a firestorm on Capitol Hill that will eventually be settled in the courts.

Medicaid expansion falls short of original goal

In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the plaintiffs asked the Supreme Court to rule on the federal government’s authority to require states to expand their Medicaid programs. Medicaid costs are typically shared by the federal and state governments. Under the ACA, state Medicaid programs were required to cover nearly all individuals who have incomes below 133% of the federal poverty level—$30,656 for a family of four in 2012—paid entirely by the federal government from 2014 through 2016. After that, the federal share gradually declines to, and then stays at, 90%. States that did not expand their Medicaid programs risked losing all federal Medicaid funding.

The Court ruled that the federal government can expand Medicaid but can’t penalize states that don’t accept the expansion mandate—effectively turning the mandate into a state option. States will receive the additional federal funds if they expand coverage, but states that don’t expand will not be penalized by losing existing federal funds for other parts of the program.

Since the ruling, a number of governors have announced that they will not expand their Medicaid programs, including governors of Florida and Louisiana. Those two states alone are home to 20% of all individuals intended to be covered under the Medicaid expansion.

This part of the ACA is particularly important to women because it strikes, for the first time, the requirement that a low-income woman must be pregnant to receive Medicaid coverage.

The figure below shows the dramatic potential improvement in coverage for women if all states fully implement the Medicaid expansion. Time, court decisions, elections, and state budget fights will determine how much of this change is realized for women’s health.

Percentage of insured women will increase under ACA

Percentage of women aged 19 to 64 years who were uninsured in 2009–2012 and under the Affordable Care Act when fully implemented.

SOURCE: Commonwealth Fund. Analysis of the March 2011 and 2010 Current Population Surveys by N. Tilipman and B. Sampat of Columbia University.

Women gain direct access to ObGyns

The ACA guarantees women in all states and all plans direct access to their ObGyns. Before the ACA, women in nine states lacked this guarantee, and women in 16 other states had only limited direct access. Now, a woman can go directly to her ObGyn without having to get a referral from her primary care physician or insurer.

Direct access is especially important because the ACA establishes new delivery systems, such as medical homes and accountable care organizations, designed to capture patients to maximize savings. An ObGyn does not have to be the patient’s primary care provider, and the patient’s access to her ObGyn cannot be limited to a certain number of visits or types of services.

ACA encourages states to cover family-planning services

Under the ACA, states have an easier time covering family-planning services, up to the same eligibility levels as pregnant women. Family planning is still an optional service that a state can choose to extend to women who have incomes above the Medicaid income eligibility level but, before the ACA was enacted, states had to apply to HHS for permission to waive the federal rules, often a very cumbersome process.