User login

Firing an Employee Is Never Easy

My recent column on good hiring practices, which stressed the importance of replacing marginal employees with excellent ones, triggered an interesting round of discussion. "Isn’t it true," asked a colleague, "that most physicians tolerate marginal employees because it’s less painful than firing them?"

Indeed it is. Firing someone is never easy, and it is particularly tough on physicians. But sometimes it is unavoidable to preserve the efficiency and morale of yourself and your other employees.

Before you do it, however, be sure that you have legitimate grounds, and assemble as much documentation as possible. Record all terminatable transgressions in the employee’s permanent record, and document all verbal and written warnings. This is essential; you must be prepared to prove that your reasons for termination were legal.

Former employees will sometimes charge that their civil rights were violated. For example, federal law prohibits you from firing anyone because of race, gender, national origin, disability, religion, or age. You cannot fire a woman because she is pregnant, or recently gave birth. Other illegal reasons include assertion of antidiscrimination rights, refusing to take a lie detector test, and reporting OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) violations.

You also can’t terminate someone for refusing to commit an illegal act, such as filing false insurance claims; or for exercising a legal right, such as voting or participating in a political demonstration.

And you cannot fire an alcohol abuser unless he or she is caught drinking at work; but many forms of illegal drug use are legitimate cause for termination. Other laws may apply, depending on where you live. When in doubt, contact your state labor department or fair employment office.

If a fired employee alleges that he or she was fired for any of these illegal reasons, and you do not have convincing documentation to counter the charge, you may find yourself defending your actions in court.

As I’ve mentioned in the past, consider adding employment practices liability insurance (EPLI) to your umbrella policy, since a wrongful termination lawsuit is always a possibility despite your best efforts to prevent it.

Once you have all your legal ducks in a row, don’t procrastinate. Get it over with, first thing on Monday morning. If you wait until Friday afternoon you will worry about the dreaded task all week long, and the fired employee will stew about it all weekend.

Explain the performance you have expected, the steps you have taken to help correct the problems you have seen, and the fact that the problems persist. Try to limit the conversation to a minute or two, have the final paycheck ready, and make it clear that the decision has already been made, so begging and pleading will not change anything.

I’ve been asked to share exactly what I say; so for what it’s worth, here it is: "I have called you in to discuss a difficult issue. You know that we have not been happy with your performance. We are still not happy with it, despite all the discussions we have had, and we feel that you can do better elsewhere. So today we will part company, and I wish you the best of luck in your future endeavors. Here is your severance check. I hope there are no hard feelings."

There will, of course be hard feelings, but that cannot be helped. The point is to be quick, firm, and decisive. Get it over with and allow everyone to move on.

Be sure to get all your office keys back – or change the locks if you cannot. Back up all important computer files, and change all your passwords. Most employees know more of them than you would ever suspect.

Finally, call the staff together and explain what you have done. They should hear the story from you, not a distorted version through the rumor mill. You don’t have to explain your reasoning or divulge every detail, but do explain how the termination will affect everyone else. Responsibilities will need to be shifted until a replacement can be hired, and all employees should understand that.

If you are asked in the future to give a reference or write a letter of recommendation for the terminated employee, be sure that everything you say is truthful and well documented.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

My recent column on good hiring practices, which stressed the importance of replacing marginal employees with excellent ones, triggered an interesting round of discussion. "Isn’t it true," asked a colleague, "that most physicians tolerate marginal employees because it’s less painful than firing them?"

Indeed it is. Firing someone is never easy, and it is particularly tough on physicians. But sometimes it is unavoidable to preserve the efficiency and morale of yourself and your other employees.

Before you do it, however, be sure that you have legitimate grounds, and assemble as much documentation as possible. Record all terminatable transgressions in the employee’s permanent record, and document all verbal and written warnings. This is essential; you must be prepared to prove that your reasons for termination were legal.

Former employees will sometimes charge that their civil rights were violated. For example, federal law prohibits you from firing anyone because of race, gender, national origin, disability, religion, or age. You cannot fire a woman because she is pregnant, or recently gave birth. Other illegal reasons include assertion of antidiscrimination rights, refusing to take a lie detector test, and reporting OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) violations.

You also can’t terminate someone for refusing to commit an illegal act, such as filing false insurance claims; or for exercising a legal right, such as voting or participating in a political demonstration.

And you cannot fire an alcohol abuser unless he or she is caught drinking at work; but many forms of illegal drug use are legitimate cause for termination. Other laws may apply, depending on where you live. When in doubt, contact your state labor department or fair employment office.

If a fired employee alleges that he or she was fired for any of these illegal reasons, and you do not have convincing documentation to counter the charge, you may find yourself defending your actions in court.

As I’ve mentioned in the past, consider adding employment practices liability insurance (EPLI) to your umbrella policy, since a wrongful termination lawsuit is always a possibility despite your best efforts to prevent it.

Once you have all your legal ducks in a row, don’t procrastinate. Get it over with, first thing on Monday morning. If you wait until Friday afternoon you will worry about the dreaded task all week long, and the fired employee will stew about it all weekend.

Explain the performance you have expected, the steps you have taken to help correct the problems you have seen, and the fact that the problems persist. Try to limit the conversation to a minute or two, have the final paycheck ready, and make it clear that the decision has already been made, so begging and pleading will not change anything.

I’ve been asked to share exactly what I say; so for what it’s worth, here it is: "I have called you in to discuss a difficult issue. You know that we have not been happy with your performance. We are still not happy with it, despite all the discussions we have had, and we feel that you can do better elsewhere. So today we will part company, and I wish you the best of luck in your future endeavors. Here is your severance check. I hope there are no hard feelings."

There will, of course be hard feelings, but that cannot be helped. The point is to be quick, firm, and decisive. Get it over with and allow everyone to move on.

Be sure to get all your office keys back – or change the locks if you cannot. Back up all important computer files, and change all your passwords. Most employees know more of them than you would ever suspect.

Finally, call the staff together and explain what you have done. They should hear the story from you, not a distorted version through the rumor mill. You don’t have to explain your reasoning or divulge every detail, but do explain how the termination will affect everyone else. Responsibilities will need to be shifted until a replacement can be hired, and all employees should understand that.

If you are asked in the future to give a reference or write a letter of recommendation for the terminated employee, be sure that everything you say is truthful and well documented.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

My recent column on good hiring practices, which stressed the importance of replacing marginal employees with excellent ones, triggered an interesting round of discussion. "Isn’t it true," asked a colleague, "that most physicians tolerate marginal employees because it’s less painful than firing them?"

Indeed it is. Firing someone is never easy, and it is particularly tough on physicians. But sometimes it is unavoidable to preserve the efficiency and morale of yourself and your other employees.

Before you do it, however, be sure that you have legitimate grounds, and assemble as much documentation as possible. Record all terminatable transgressions in the employee’s permanent record, and document all verbal and written warnings. This is essential; you must be prepared to prove that your reasons for termination were legal.

Former employees will sometimes charge that their civil rights were violated. For example, federal law prohibits you from firing anyone because of race, gender, national origin, disability, religion, or age. You cannot fire a woman because she is pregnant, or recently gave birth. Other illegal reasons include assertion of antidiscrimination rights, refusing to take a lie detector test, and reporting OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) violations.

You also can’t terminate someone for refusing to commit an illegal act, such as filing false insurance claims; or for exercising a legal right, such as voting or participating in a political demonstration.

And you cannot fire an alcohol abuser unless he or she is caught drinking at work; but many forms of illegal drug use are legitimate cause for termination. Other laws may apply, depending on where you live. When in doubt, contact your state labor department or fair employment office.

If a fired employee alleges that he or she was fired for any of these illegal reasons, and you do not have convincing documentation to counter the charge, you may find yourself defending your actions in court.

As I’ve mentioned in the past, consider adding employment practices liability insurance (EPLI) to your umbrella policy, since a wrongful termination lawsuit is always a possibility despite your best efforts to prevent it.

Once you have all your legal ducks in a row, don’t procrastinate. Get it over with, first thing on Monday morning. If you wait until Friday afternoon you will worry about the dreaded task all week long, and the fired employee will stew about it all weekend.

Explain the performance you have expected, the steps you have taken to help correct the problems you have seen, and the fact that the problems persist. Try to limit the conversation to a minute or two, have the final paycheck ready, and make it clear that the decision has already been made, so begging and pleading will not change anything.

I’ve been asked to share exactly what I say; so for what it’s worth, here it is: "I have called you in to discuss a difficult issue. You know that we have not been happy with your performance. We are still not happy with it, despite all the discussions we have had, and we feel that you can do better elsewhere. So today we will part company, and I wish you the best of luck in your future endeavors. Here is your severance check. I hope there are no hard feelings."

There will, of course be hard feelings, but that cannot be helped. The point is to be quick, firm, and decisive. Get it over with and allow everyone to move on.

Be sure to get all your office keys back – or change the locks if you cannot. Back up all important computer files, and change all your passwords. Most employees know more of them than you would ever suspect.

Finally, call the staff together and explain what you have done. They should hear the story from you, not a distorted version through the rumor mill. You don’t have to explain your reasoning or divulge every detail, but do explain how the termination will affect everyone else. Responsibilities will need to be shifted until a replacement can be hired, and all employees should understand that.

If you are asked in the future to give a reference or write a letter of recommendation for the terminated employee, be sure that everything you say is truthful and well documented.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

AHRQ's Director Looks to Hospitalists to Help Reduce Readmissions

Although a recently released study of Medicare data uncovers little progress in reducing hospital readmissions, and the Oct. 1 deadline to implement CMS’ Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program looms, Carolyn Clancy, MD, director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), says she's not worried about the ability of America’s hospitalists to rise to the occasion and get a handle on the problem.

Dr. Clancy recently wrote a commentary outlining the government's approach to controlling readmissions, stating that taking aim at readmissions is 1) an integral component of its value-based purchasing program and 2) is an opportunity for improving hospital quality and patient safety.

"Hospitalists are often on the receiving end of hospitalizations resulting from poor coordination of care. I think it would be very exciting to be part of the solution," Dr. Clancy says. She says she observed firsthand during a recent hospital stay how hospitalists helped her to think about how she should care for herself after returning home. But her father suffered a needless rehospitalization when important information (how much Coumadin to take) was miscommunicated in a post-discharge follow-up phone call, causing him to start bleeding.

"Hospitalists who want to embrace the challenge will find a phenomenal amount of information on Innovations Exchange, where people from all over America are sharing their clinical innovations."

Dr. Clancy says she hopes AHRQ-supported tools and studies "will make it easier for hospitals to do the right thing."

Although a recently released study of Medicare data uncovers little progress in reducing hospital readmissions, and the Oct. 1 deadline to implement CMS’ Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program looms, Carolyn Clancy, MD, director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), says she's not worried about the ability of America’s hospitalists to rise to the occasion and get a handle on the problem.

Dr. Clancy recently wrote a commentary outlining the government's approach to controlling readmissions, stating that taking aim at readmissions is 1) an integral component of its value-based purchasing program and 2) is an opportunity for improving hospital quality and patient safety.

"Hospitalists are often on the receiving end of hospitalizations resulting from poor coordination of care. I think it would be very exciting to be part of the solution," Dr. Clancy says. She says she observed firsthand during a recent hospital stay how hospitalists helped her to think about how she should care for herself after returning home. But her father suffered a needless rehospitalization when important information (how much Coumadin to take) was miscommunicated in a post-discharge follow-up phone call, causing him to start bleeding.

"Hospitalists who want to embrace the challenge will find a phenomenal amount of information on Innovations Exchange, where people from all over America are sharing their clinical innovations."

Dr. Clancy says she hopes AHRQ-supported tools and studies "will make it easier for hospitals to do the right thing."

Although a recently released study of Medicare data uncovers little progress in reducing hospital readmissions, and the Oct. 1 deadline to implement CMS’ Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program looms, Carolyn Clancy, MD, director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), says she's not worried about the ability of America’s hospitalists to rise to the occasion and get a handle on the problem.

Dr. Clancy recently wrote a commentary outlining the government's approach to controlling readmissions, stating that taking aim at readmissions is 1) an integral component of its value-based purchasing program and 2) is an opportunity for improving hospital quality and patient safety.

"Hospitalists are often on the receiving end of hospitalizations resulting from poor coordination of care. I think it would be very exciting to be part of the solution," Dr. Clancy says. She says she observed firsthand during a recent hospital stay how hospitalists helped her to think about how she should care for herself after returning home. But her father suffered a needless rehospitalization when important information (how much Coumadin to take) was miscommunicated in a post-discharge follow-up phone call, causing him to start bleeding.

"Hospitalists who want to embrace the challenge will find a phenomenal amount of information on Innovations Exchange, where people from all over America are sharing their clinical innovations."

Dr. Clancy says she hopes AHRQ-supported tools and studies "will make it easier for hospitals to do the right thing."

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Elbert Huang discusses primary care's role in providing access and value

Click here to listen to Dr. Huang

Click here to listen to Dr. Huang

Click here to listen to Dr. Huang

Insurers Promote Collaborative Approach to 30-Day Readmission Reductions

Although Medicare's looming financial penalties for hospitals with excessive readmissions might seem like a blunt weapon, private health plans often have the flexibility to negotiate with partnering hospitals around incentives for readmissions prevention.

"We have arrangements with private insurance companies where we put at risk future compensation, based on achieving negotiated readmissions results," says Mark Carley, vice president of managed care and network development for Centura Health, a 13-hospital system in Colorado.

Payors, including United Healthcare, have developed their own readmissions programs and reporting mechanisms, although each program’s incentives are a little different, Carley says. Target rates are negotiated based on each hospital's readmissions in the previous 12-month period and national averages. The plan can also provide helpful data on its beneficiaries and other forms of assistance, because it wants to see the hospital hit the target, he adds. "If the target has been set too high, they may be willing to renegotiate."

But the plan doesn't tell the hospital how to reach that target.

"Where the complexity comes in is how we as a system implement internal policies and procedures to improve our care coordination, discharge processes, follow-up, and communication with downstream providers," says Carley. Centura Health's approach to readmissions has included close study of past performance data in search of opportunities for improvement, fine-tuning of the discharge planning process, and follow-up phone calls to patients and providers.

"In addition, we are working with post-acute providers to provide smoother transitions in the discharge process," he says.

Although Medicare's looming financial penalties for hospitals with excessive readmissions might seem like a blunt weapon, private health plans often have the flexibility to negotiate with partnering hospitals around incentives for readmissions prevention.

"We have arrangements with private insurance companies where we put at risk future compensation, based on achieving negotiated readmissions results," says Mark Carley, vice president of managed care and network development for Centura Health, a 13-hospital system in Colorado.

Payors, including United Healthcare, have developed their own readmissions programs and reporting mechanisms, although each program’s incentives are a little different, Carley says. Target rates are negotiated based on each hospital's readmissions in the previous 12-month period and national averages. The plan can also provide helpful data on its beneficiaries and other forms of assistance, because it wants to see the hospital hit the target, he adds. "If the target has been set too high, they may be willing to renegotiate."

But the plan doesn't tell the hospital how to reach that target.

"Where the complexity comes in is how we as a system implement internal policies and procedures to improve our care coordination, discharge processes, follow-up, and communication with downstream providers," says Carley. Centura Health's approach to readmissions has included close study of past performance data in search of opportunities for improvement, fine-tuning of the discharge planning process, and follow-up phone calls to patients and providers.

"In addition, we are working with post-acute providers to provide smoother transitions in the discharge process," he says.

Although Medicare's looming financial penalties for hospitals with excessive readmissions might seem like a blunt weapon, private health plans often have the flexibility to negotiate with partnering hospitals around incentives for readmissions prevention.

"We have arrangements with private insurance companies where we put at risk future compensation, based on achieving negotiated readmissions results," says Mark Carley, vice president of managed care and network development for Centura Health, a 13-hospital system in Colorado.

Payors, including United Healthcare, have developed their own readmissions programs and reporting mechanisms, although each program’s incentives are a little different, Carley says. Target rates are negotiated based on each hospital's readmissions in the previous 12-month period and national averages. The plan can also provide helpful data on its beneficiaries and other forms of assistance, because it wants to see the hospital hit the target, he adds. "If the target has been set too high, they may be willing to renegotiate."

But the plan doesn't tell the hospital how to reach that target.

"Where the complexity comes in is how we as a system implement internal policies and procedures to improve our care coordination, discharge processes, follow-up, and communication with downstream providers," says Carley. Centura Health's approach to readmissions has included close study of past performance data in search of opportunities for improvement, fine-tuning of the discharge planning process, and follow-up phone calls to patients and providers.

"In addition, we are working with post-acute providers to provide smoother transitions in the discharge process," he says.

Prolonged delivery: child with CP awarded $70M … and more

AFTER MORE THAN 4 HOURS of second-stage labor followed by prolonged pushing and crowning, the baby was born depressed. Later, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to perform an episiotomy, not attempting vacuum extraction, and not using forceps to assist delivery. Although fetal heart-rate monitoring results deteriorated, the ObGyn did not assess contractions for 30 minutes at one point. Hospital staff members were unable to adequately intubate or ventilate the newborn. The hospital staff disposed of the baby’s cord blood. Records were altered.

The parents’ counsel proposed that the defendants’ insurance company refused all settlement efforts prior to trial because the case venue was known to be conservative regarding jury verdicts.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The hospital and the ObGyn were not negligent; the mother and baby received proper care. Hospital staff acted appropriately.

VERDICT During the trial, the hospital settled for an undisclosed amount. An additional $2 million was offered on behalf of the ObGyn later in the trial, but the parents refused settlement at that time.

A California jury returned a $74.525 million verdict against the ObGyn. The child was awarded $70.725 million for medical expenses, lost earnings, and damages. The parents were awarded $3.8 million for emotional distress.

Was ectopic pregnancy missed?

A WOMAN IN SEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN saw her internist. CT scans revealed a right ovarian cyst. When pain continued, she saw her ObGyn 3 weeks later, and her bowel was full of hard stool. Ultrasonography (US) showed a multicystic right ovary and a thin endometrial stripe. She was taking birth control pills and her husband had a vasectomy. She was told her abdominal pain was from constipation and ovarian cysts. A week later, she had laparoscopic surgery to remove an ectopic pregnancy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform a pregnancy test, and did not diagnose an ectopic pregnancy in a timely manner. An earlier diagnosis would have allowed medical rather than surgical resolution.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE It was too early to determine if the pregnancy was intrauterine or ectopic. An earlier diagnosis would have resulted in laparoscopic surgery rather than medical treatment, as the medication (methotrexate) can cause increased pain.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Foreshortened vagina inhibits intercourse

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent anterior and posterior colphorrhaphy to repair a cystocele and rectocele, sacrospinous ligament fixation for vaginal prolapse, and a TVT mid-urethral suspension procedure to correct stress urinary incontinence. During two follow-up visits, the gynecologist determined that she was healing normally.

Within the next few weeks, the patient came to believe that her vagina had been sewn shut. She did not return to her gynecologist, but sought treatment with another physician 6 months later. It was determined that she had a stenotic and foreshortened vagina.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Too much vaginal tissue was removed during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The stenotic and foreshortened vagina was an unexpected result of the healing process after surgery.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Hydrocephalus in utero not seen until too late

A WOMAN HAD PRENATAL TREATMENT at a federally funded health clinic. A certified nurse midwife (CNM) ordered second-trimester US, with normal results. During the third trimester, the mother switched to a private ObGyn who ordered testing. US indicated the fetus was hydrocephalic. The child was born with cognitive disabilities and will need lifelong care.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The CNM ordered US too early in the pregnancy to be of diagnostic value; no further testing was undertaken. When hydrocephalus was seen, an abortion was not legally available because of fetal age.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Even if US had been performed later in the second trimester, the defect would not have shown.

VERDICT A $4 million New Jersey settlement was reached.

WHEN SHOULDER DYSTOCIA WAS ENCOUNTERED, the ObGyn used standard maneuvers to deliver the child. The baby suffered a severe brachial plexus injury with rupture of C7 nerve and avulsions at C8 and T1.

Nerve-graft surgery at 6 months and tendon transfer surgery at 2 years resulted in recovery of good shoulder and elbow function, but the child has inadequate use of his wrist and hand. Additional surgeries are planned.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not inform the mother that she was at risk for shoulder dystocia, nor did he discuss cesarean delivery. The mother’s risk factors included short stature, gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, and two previous deliveries that involved vacuum assistance and a broken clavicle. The ObGyn applied excessive traction to the fetal head during delivery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother’s risk factors were not severe enough to consider the chance of shoulder dystocia. The baby’s injuries were due to the normal forces of labor. Traction placed on the baby’s head during delivery was gentle and appropriate.

VERDICT A $5.5 million Iowa verdict was returned.

Faulty testing: baby has Down syndrome

AT 13 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 34-year-old woman underwent chorionic villus sampling (CVS) at a maternal-fetal medicine center. Results showed a normal chromosomal profile. Later, two sonograms indicated possible Down syndrome. The parents were assured that the baby did not have a genetic disorder; amniocentesis was never suggested.

A week before the baby’s birth, the parents were told the child has Down syndrome.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Maternal tissue, not fetal tissue, had been removed and tested during CVS. The parents would have aborted the fetus had they known she had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE CVS was properly administered.

VERDICT A $3 million Missouri verdict was returned against the center where the testing was performed.

Why did the uterus seem to be growing?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN’S UTERUS was larger than normal in February 2007. By November 2008, her uterus was the size of a 14-week gestation. In September 2009, she complained of abdominal discomfort. Her uterus was larger than at the previous visit. The gynecologist suggested a hysterectomy, but nothing was scheduled.

In November 2009, she reported increasing pelvic pressure; her uterus was the size of an 18-week gestation. US and MRI showed large masses on both ovaries although the uterus had no masses or fibroids within it. A gynecologic oncologist performed abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral peri-aortic lymph node dissection. Pathology returned a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The patient underwent chemotherapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist was negligent in not ordering testing in 2007 when the larger-than-normal uterus was first detected, or in subsequent visits through September 2009. A more timely reaction would have given her an opportunity to treat the cancer at an earlier stage.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $650,000 Maryland settlement was reached.

Erb’s palsy after shoulder dystocia

DURING VAGINAL DELIVERY, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury and has Erb’s palsy. There was some improvement after two operations, but she still has muscle weakness, arm-length discrepancy, and limited range of motion.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn applied excessive downward traction on the baby’s head when her left shoulder could not pass under the pubic bone.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The injury was caused by uterine contractions and maternal pushing. Proper maneuvers and gentle pressure were used.

VERDICT A $1.34 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

AFTER MORE THAN 4 HOURS of second-stage labor followed by prolonged pushing and crowning, the baby was born depressed. Later, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to perform an episiotomy, not attempting vacuum extraction, and not using forceps to assist delivery. Although fetal heart-rate monitoring results deteriorated, the ObGyn did not assess contractions for 30 minutes at one point. Hospital staff members were unable to adequately intubate or ventilate the newborn. The hospital staff disposed of the baby’s cord blood. Records were altered.

The parents’ counsel proposed that the defendants’ insurance company refused all settlement efforts prior to trial because the case venue was known to be conservative regarding jury verdicts.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The hospital and the ObGyn were not negligent; the mother and baby received proper care. Hospital staff acted appropriately.

VERDICT During the trial, the hospital settled for an undisclosed amount. An additional $2 million was offered on behalf of the ObGyn later in the trial, but the parents refused settlement at that time.

A California jury returned a $74.525 million verdict against the ObGyn. The child was awarded $70.725 million for medical expenses, lost earnings, and damages. The parents were awarded $3.8 million for emotional distress.

Was ectopic pregnancy missed?

A WOMAN IN SEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN saw her internist. CT scans revealed a right ovarian cyst. When pain continued, she saw her ObGyn 3 weeks later, and her bowel was full of hard stool. Ultrasonography (US) showed a multicystic right ovary and a thin endometrial stripe. She was taking birth control pills and her husband had a vasectomy. She was told her abdominal pain was from constipation and ovarian cysts. A week later, she had laparoscopic surgery to remove an ectopic pregnancy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform a pregnancy test, and did not diagnose an ectopic pregnancy in a timely manner. An earlier diagnosis would have allowed medical rather than surgical resolution.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE It was too early to determine if the pregnancy was intrauterine or ectopic. An earlier diagnosis would have resulted in laparoscopic surgery rather than medical treatment, as the medication (methotrexate) can cause increased pain.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Foreshortened vagina inhibits intercourse

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent anterior and posterior colphorrhaphy to repair a cystocele and rectocele, sacrospinous ligament fixation for vaginal prolapse, and a TVT mid-urethral suspension procedure to correct stress urinary incontinence. During two follow-up visits, the gynecologist determined that she was healing normally.

Within the next few weeks, the patient came to believe that her vagina had been sewn shut. She did not return to her gynecologist, but sought treatment with another physician 6 months later. It was determined that she had a stenotic and foreshortened vagina.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Too much vaginal tissue was removed during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The stenotic and foreshortened vagina was an unexpected result of the healing process after surgery.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Hydrocephalus in utero not seen until too late

A WOMAN HAD PRENATAL TREATMENT at a federally funded health clinic. A certified nurse midwife (CNM) ordered second-trimester US, with normal results. During the third trimester, the mother switched to a private ObGyn who ordered testing. US indicated the fetus was hydrocephalic. The child was born with cognitive disabilities and will need lifelong care.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The CNM ordered US too early in the pregnancy to be of diagnostic value; no further testing was undertaken. When hydrocephalus was seen, an abortion was not legally available because of fetal age.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Even if US had been performed later in the second trimester, the defect would not have shown.

VERDICT A $4 million New Jersey settlement was reached.

WHEN SHOULDER DYSTOCIA WAS ENCOUNTERED, the ObGyn used standard maneuvers to deliver the child. The baby suffered a severe brachial plexus injury with rupture of C7 nerve and avulsions at C8 and T1.

Nerve-graft surgery at 6 months and tendon transfer surgery at 2 years resulted in recovery of good shoulder and elbow function, but the child has inadequate use of his wrist and hand. Additional surgeries are planned.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not inform the mother that she was at risk for shoulder dystocia, nor did he discuss cesarean delivery. The mother’s risk factors included short stature, gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, and two previous deliveries that involved vacuum assistance and a broken clavicle. The ObGyn applied excessive traction to the fetal head during delivery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother’s risk factors were not severe enough to consider the chance of shoulder dystocia. The baby’s injuries were due to the normal forces of labor. Traction placed on the baby’s head during delivery was gentle and appropriate.

VERDICT A $5.5 million Iowa verdict was returned.

Faulty testing: baby has Down syndrome

AT 13 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 34-year-old woman underwent chorionic villus sampling (CVS) at a maternal-fetal medicine center. Results showed a normal chromosomal profile. Later, two sonograms indicated possible Down syndrome. The parents were assured that the baby did not have a genetic disorder; amniocentesis was never suggested.

A week before the baby’s birth, the parents were told the child has Down syndrome.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Maternal tissue, not fetal tissue, had been removed and tested during CVS. The parents would have aborted the fetus had they known she had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE CVS was properly administered.

VERDICT A $3 million Missouri verdict was returned against the center where the testing was performed.

Why did the uterus seem to be growing?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN’S UTERUS was larger than normal in February 2007. By November 2008, her uterus was the size of a 14-week gestation. In September 2009, she complained of abdominal discomfort. Her uterus was larger than at the previous visit. The gynecologist suggested a hysterectomy, but nothing was scheduled.

In November 2009, she reported increasing pelvic pressure; her uterus was the size of an 18-week gestation. US and MRI showed large masses on both ovaries although the uterus had no masses or fibroids within it. A gynecologic oncologist performed abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral peri-aortic lymph node dissection. Pathology returned a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The patient underwent chemotherapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist was negligent in not ordering testing in 2007 when the larger-than-normal uterus was first detected, or in subsequent visits through September 2009. A more timely reaction would have given her an opportunity to treat the cancer at an earlier stage.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $650,000 Maryland settlement was reached.

Erb’s palsy after shoulder dystocia

DURING VAGINAL DELIVERY, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury and has Erb’s palsy. There was some improvement after two operations, but she still has muscle weakness, arm-length discrepancy, and limited range of motion.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn applied excessive downward traction on the baby’s head when her left shoulder could not pass under the pubic bone.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The injury was caused by uterine contractions and maternal pushing. Proper maneuvers and gentle pressure were used.

VERDICT A $1.34 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

AFTER MORE THAN 4 HOURS of second-stage labor followed by prolonged pushing and crowning, the baby was born depressed. Later, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to perform an episiotomy, not attempting vacuum extraction, and not using forceps to assist delivery. Although fetal heart-rate monitoring results deteriorated, the ObGyn did not assess contractions for 30 minutes at one point. Hospital staff members were unable to adequately intubate or ventilate the newborn. The hospital staff disposed of the baby’s cord blood. Records were altered.

The parents’ counsel proposed that the defendants’ insurance company refused all settlement efforts prior to trial because the case venue was known to be conservative regarding jury verdicts.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The hospital and the ObGyn were not negligent; the mother and baby received proper care. Hospital staff acted appropriately.

VERDICT During the trial, the hospital settled for an undisclosed amount. An additional $2 million was offered on behalf of the ObGyn later in the trial, but the parents refused settlement at that time.

A California jury returned a $74.525 million verdict against the ObGyn. The child was awarded $70.725 million for medical expenses, lost earnings, and damages. The parents were awarded $3.8 million for emotional distress.

Was ectopic pregnancy missed?

A WOMAN IN SEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN saw her internist. CT scans revealed a right ovarian cyst. When pain continued, she saw her ObGyn 3 weeks later, and her bowel was full of hard stool. Ultrasonography (US) showed a multicystic right ovary and a thin endometrial stripe. She was taking birth control pills and her husband had a vasectomy. She was told her abdominal pain was from constipation and ovarian cysts. A week later, she had laparoscopic surgery to remove an ectopic pregnancy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform a pregnancy test, and did not diagnose an ectopic pregnancy in a timely manner. An earlier diagnosis would have allowed medical rather than surgical resolution.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE It was too early to determine if the pregnancy was intrauterine or ectopic. An earlier diagnosis would have resulted in laparoscopic surgery rather than medical treatment, as the medication (methotrexate) can cause increased pain.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Foreshortened vagina inhibits intercourse

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent anterior and posterior colphorrhaphy to repair a cystocele and rectocele, sacrospinous ligament fixation for vaginal prolapse, and a TVT mid-urethral suspension procedure to correct stress urinary incontinence. During two follow-up visits, the gynecologist determined that she was healing normally.

Within the next few weeks, the patient came to believe that her vagina had been sewn shut. She did not return to her gynecologist, but sought treatment with another physician 6 months later. It was determined that she had a stenotic and foreshortened vagina.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Too much vaginal tissue was removed during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The stenotic and foreshortened vagina was an unexpected result of the healing process after surgery.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Hydrocephalus in utero not seen until too late

A WOMAN HAD PRENATAL TREATMENT at a federally funded health clinic. A certified nurse midwife (CNM) ordered second-trimester US, with normal results. During the third trimester, the mother switched to a private ObGyn who ordered testing. US indicated the fetus was hydrocephalic. The child was born with cognitive disabilities and will need lifelong care.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The CNM ordered US too early in the pregnancy to be of diagnostic value; no further testing was undertaken. When hydrocephalus was seen, an abortion was not legally available because of fetal age.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Even if US had been performed later in the second trimester, the defect would not have shown.

VERDICT A $4 million New Jersey settlement was reached.

WHEN SHOULDER DYSTOCIA WAS ENCOUNTERED, the ObGyn used standard maneuvers to deliver the child. The baby suffered a severe brachial plexus injury with rupture of C7 nerve and avulsions at C8 and T1.

Nerve-graft surgery at 6 months and tendon transfer surgery at 2 years resulted in recovery of good shoulder and elbow function, but the child has inadequate use of his wrist and hand. Additional surgeries are planned.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not inform the mother that she was at risk for shoulder dystocia, nor did he discuss cesarean delivery. The mother’s risk factors included short stature, gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, and two previous deliveries that involved vacuum assistance and a broken clavicle. The ObGyn applied excessive traction to the fetal head during delivery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother’s risk factors were not severe enough to consider the chance of shoulder dystocia. The baby’s injuries were due to the normal forces of labor. Traction placed on the baby’s head during delivery was gentle and appropriate.

VERDICT A $5.5 million Iowa verdict was returned.

Faulty testing: baby has Down syndrome

AT 13 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 34-year-old woman underwent chorionic villus sampling (CVS) at a maternal-fetal medicine center. Results showed a normal chromosomal profile. Later, two sonograms indicated possible Down syndrome. The parents were assured that the baby did not have a genetic disorder; amniocentesis was never suggested.

A week before the baby’s birth, the parents were told the child has Down syndrome.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Maternal tissue, not fetal tissue, had been removed and tested during CVS. The parents would have aborted the fetus had they known she had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE CVS was properly administered.

VERDICT A $3 million Missouri verdict was returned against the center where the testing was performed.

Why did the uterus seem to be growing?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN’S UTERUS was larger than normal in February 2007. By November 2008, her uterus was the size of a 14-week gestation. In September 2009, she complained of abdominal discomfort. Her uterus was larger than at the previous visit. The gynecologist suggested a hysterectomy, but nothing was scheduled.

In November 2009, she reported increasing pelvic pressure; her uterus was the size of an 18-week gestation. US and MRI showed large masses on both ovaries although the uterus had no masses or fibroids within it. A gynecologic oncologist performed abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral peri-aortic lymph node dissection. Pathology returned a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The patient underwent chemotherapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist was negligent in not ordering testing in 2007 when the larger-than-normal uterus was first detected, or in subsequent visits through September 2009. A more timely reaction would have given her an opportunity to treat the cancer at an earlier stage.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $650,000 Maryland settlement was reached.

Erb’s palsy after shoulder dystocia

DURING VAGINAL DELIVERY, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury and has Erb’s palsy. There was some improvement after two operations, but she still has muscle weakness, arm-length discrepancy, and limited range of motion.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn applied excessive downward traction on the baby’s head when her left shoulder could not pass under the pubic bone.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The injury was caused by uterine contractions and maternal pushing. Proper maneuvers and gentle pressure were used.

VERDICT A $1.34 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

New overactive bladder treatment approved by FDA

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Myrbetriq™ (mirabegron) extended-release tablets for the treatment of overactive bladder (OAB) with symptoms of urge urinary incontinence, urgency, and urinary frequency.

“Myrbetriq is the first oral OAB treatment with a distinct mechanism of action since the launch of anticholinergic agents 30 years ago,” said Steven Ryder, MD, president of Astellas Pharma Global Development. “The approval of Myrbetriq represents an important milestone in OAB treatment and in our ongoing commitment to advancing urological health.” Astellas Pharma US, Inc., is a subsidiary of Tokyo-based Astellas Pharma Inc.

Myrbetriq, a once-daily oral beta-3 adrenergic agonist, offers a new treatment option for patients with OAB. Antimuscarinics, the current OAB treatment standard, work by binding to muscarinic receptors in the bladder and inhibiting involuntary bladder contractions. Myrbetriq relaxes the detrusor smooth muscle during the storage phase of the urinary bladder fill-void cycle by activation of beta-3 adrenergic receptors, therefore increasing bladder capacity.

Myrbetriq has been studied in more than 10,000 individuals over 10 years. FDA approval was based on safety and efficacy data from three placebo-controlled Phase 3 studies in which treatment with Myrbetriq 25 mg and 50 mg resulted in statistically significantly improvement in efficacy parameters of incontinence episodes and number of urinations per 24 hours.

The recommended starting dose for Myrbetriq is 25 mg once daily with or without food. The dose may be increased to 50 mg. Most commonly reported adverse reactions were hypertension, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache. Myrbetriq will be available in pharmacies in the fourth quarter of 2012.

For additional information, visit www.myrbetriq.com.

Update on Urinary Incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (December 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Myrbetriq™ (mirabegron) extended-release tablets for the treatment of overactive bladder (OAB) with symptoms of urge urinary incontinence, urgency, and urinary frequency.

“Myrbetriq is the first oral OAB treatment with a distinct mechanism of action since the launch of anticholinergic agents 30 years ago,” said Steven Ryder, MD, president of Astellas Pharma Global Development. “The approval of Myrbetriq represents an important milestone in OAB treatment and in our ongoing commitment to advancing urological health.” Astellas Pharma US, Inc., is a subsidiary of Tokyo-based Astellas Pharma Inc.

Myrbetriq, a once-daily oral beta-3 adrenergic agonist, offers a new treatment option for patients with OAB. Antimuscarinics, the current OAB treatment standard, work by binding to muscarinic receptors in the bladder and inhibiting involuntary bladder contractions. Myrbetriq relaxes the detrusor smooth muscle during the storage phase of the urinary bladder fill-void cycle by activation of beta-3 adrenergic receptors, therefore increasing bladder capacity.

Myrbetriq has been studied in more than 10,000 individuals over 10 years. FDA approval was based on safety and efficacy data from three placebo-controlled Phase 3 studies in which treatment with Myrbetriq 25 mg and 50 mg resulted in statistically significantly improvement in efficacy parameters of incontinence episodes and number of urinations per 24 hours.

The recommended starting dose for Myrbetriq is 25 mg once daily with or without food. The dose may be increased to 50 mg. Most commonly reported adverse reactions were hypertension, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache. Myrbetriq will be available in pharmacies in the fourth quarter of 2012.

For additional information, visit www.myrbetriq.com.

Update on Urinary Incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (December 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Myrbetriq™ (mirabegron) extended-release tablets for the treatment of overactive bladder (OAB) with symptoms of urge urinary incontinence, urgency, and urinary frequency.

“Myrbetriq is the first oral OAB treatment with a distinct mechanism of action since the launch of anticholinergic agents 30 years ago,” said Steven Ryder, MD, president of Astellas Pharma Global Development. “The approval of Myrbetriq represents an important milestone in OAB treatment and in our ongoing commitment to advancing urological health.” Astellas Pharma US, Inc., is a subsidiary of Tokyo-based Astellas Pharma Inc.

Myrbetriq, a once-daily oral beta-3 adrenergic agonist, offers a new treatment option for patients with OAB. Antimuscarinics, the current OAB treatment standard, work by binding to muscarinic receptors in the bladder and inhibiting involuntary bladder contractions. Myrbetriq relaxes the detrusor smooth muscle during the storage phase of the urinary bladder fill-void cycle by activation of beta-3 adrenergic receptors, therefore increasing bladder capacity.

Myrbetriq has been studied in more than 10,000 individuals over 10 years. FDA approval was based on safety and efficacy data from three placebo-controlled Phase 3 studies in which treatment with Myrbetriq 25 mg and 50 mg resulted in statistically significantly improvement in efficacy parameters of incontinence episodes and number of urinations per 24 hours.

The recommended starting dose for Myrbetriq is 25 mg once daily with or without food. The dose may be increased to 50 mg. Most commonly reported adverse reactions were hypertension, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache. Myrbetriq will be available in pharmacies in the fourth quarter of 2012.

For additional information, visit www.myrbetriq.com.

Update on Urinary Incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (December 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Workforce Shortages, Increased Patient Populations, and Funding Woes Pressure U.S. Primary-Care System

It’s been about 15 years since the last surge of interest in primary care as a career, when U.S. medical graduates temporarily reversed a long decline by flocking to family medicine, general internal medicine, and pediatrics. Newly minted doctors responded enthusiastically to a widely held perception in the mid-1990s that primary care would be central to a brave new paradigm of managed healthcare delivery.

That profound change never materialized, and the primary-care workforce has since resumed a downward slide that is sounding alarm bells throughout the country. Even more distressing, the medical profession’s recent misfortunes have spread far beyond the doctor’s office.

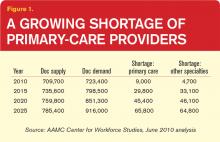

“What we’re looking at now is that there’s a shortage of somewhere around 90,000 physicians in the next 10 years, increasing in the five years beyond that to 125,000 or more,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The association’s estimates suggest that the 10- and 15-year shortfalls will be split nearly evenly between primary care and other specialties.

Hospitalists could feel that widening gap as well. With increasing numbers of aging baby boomers reaching Medicare eligibility and 32 million Americans set to join the ranks of the insured by 2019 through the Affordable Care Act, primary care’s difficulties arguably are the closest to a full-blown crisis. “Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline,” began a 2009 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 And that was before an estimate suggesting that new insurance mandates will require an additional 4,307 to 6,940 primary-care physicians to meet demand before the end of the decade contributing about 15% to the expected shortfall.2

Why should hospitalists care about the fate of their counterparts? For starters, what’s good for outpatient providers is good for a sound healthcare system. Researchers have linked strong

primary care to lower overall spending, fewer health disparities, and higher quality of care.3

Hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) also are inexorably linked. They follow similar training and education pathways, and need each other to ensure safe transitions of care. And despite the evidence pointing to a slew of contributing factors, HM regularly is blamed for many of primary care’s mounting woes.

Based on well-functioning healthcare systems around the world, analysts say the ideal primary-care-to-specialty-care-provider ratio should be roughly 40:60 or 50:50. According to Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), only about 32% of physicians in the U.S. are practicing primary care. Unless something changes, that percentage will erode even further. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” Dr. Klink says.

Opinions differ on the extent of the current PCP shortage. Nevertheless, there is clearly a “huge maldistribution problem,” says Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center. Rural and underserved areas already are being shortchanged as more doctors locate in more affluent and desirable areas, he says.

That phenomenon is hardly unique to primary care, but Dr. Phillips says the deficit in frontline doctors could cause disproportionately more hardships in rural and underserved communities given the shrinking pipeline for medical trainees. A decade ago, almost a third of all medical graduates were placed into primary-care residency training slots. Now, he says, that figure is a bit less than 22%. “We can’t even replace the primary-care workforce we have now with that kind of output,” Dr. Phillips says.

Already, many doctors are no longer accepting new Medicaid or Medicare patients because their practices are losing money from low reimbursement rates. The Affordable Care Act’s significant expansion of insurance benefits, Dr. Grover says, will effectively accelerate the timetable of growing imbalances between supply and demand. “I think the challenge you face is, Will the ACA efforts to expand access fail because you’re giving people an insurance card but you have nobody there to take care of them?”

Reasons Aplenty

Some medical students simply aren’t interested in primary care. For the rest, however, interviews with doctors, analysts, and federal officials suggest that the pipeline has been battered throughout its length. Of all the contributing factors, Dr. Phillips says, the main one might be income disparity. In a 2009 study, the center found that the growing gulf in salaries between primary care and subspecialty medicine “cuts in half the likelihood that a student will choose to go into primary care,” he says. Over a career, that gap translates into a difference of $3.5 million. “It dissuades them strongly,” Dr. Phillips says.

At the same time, medical school tuitions have increased at a rate far outstripping the consumer price index. “What we found is that when you hit somewhere between $200,000 and $250,000 in debt, that’s where you see the dropoff really happen,” he says. “Because it becomes almost unfathomable that you can, on a primary-care income, pay off your debts without it severely cutting into your lifestyle.”

Lori Heim, MD, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a hospitalist at Scotland Memorial Hospital in Laurinburg, N.C., says the prevailing fee-for-service payment model has failed primary-care providers, requiring them to work more to meet soaring outpatient demand but reimbursing them less. “People talk about the hamster wheel,” she says. “And that has created more workplace dissatisfaction. Not only does it impact students, but it also impacts the number of primary-care physicians who want to stay in the community, practicing.”

Frederick Chen, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, can relate. “I came from community practice, where you’re seeing 30 to 35 patients a day, and the pressure was entirely on your productivity, and that’s not fun,” he says. “So we’re burning out a lot of primary-care physicians, and students are seeing that very easily.”

The larger theme, several doctors say, is one of perceived worth. Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., says she has to think holistically about her patients’ symptoms, medication lists, family history, home situation, and other factors during her limited time with them. She bristles at the notion that specialists might spend their time considering only one aspect of her patients’ care yet bill twice as much.

“Realistically, I am providing better value to the healthcare system than a specialist does, and yet we pay specialists much more,” she says. “And until that’s different, people go where the money is and they also go where the respect is, and I think it’s going to be very hard to recruit more people to primary care.”

Despite research pointing to financial concerns, lifestyle perceptions, and training inadequacies as key factors in the decline of primary care, perceptions that HM is poaching young talent have been hard to shake. A recent article in The Atlantic asserts that HM might be a “rational choice” given the profession’s more favorable training, lifestyle, and financial considerations.4 The author, a general internist, contrasts those enticements “to the realities of office practice: Fifteen-minute visits with patients on multiple medications, oodles of paperwork that cause office docs to run a gauntlet just to get through their day, and more documentation and regulatory burdens than ever before.”

Nevertheless, the article describes PCPs who resist hospitals’ calls to move to a hospitalist system as honorable “holdouts” who are committed to being directly involved in their patients’ care.

In her blog post at KevinMD.com, “Hospitalists are Killing Primary Care, and other Myths Debunked,” Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago, addresses those perceptions head-on. “If hospitalists did not exist, there would still be declining interest in primary care among medical students and residents,” she writes.

In a subsequent interview, Dr. Arora contends that both primary care and HM instead might be losing out to higher-paying subspecialties, especially the “ROAD” quartet of radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology, and dermatology. She also questions the notion that the professions draw from the same talent pool. “Anecdotally, I can tell you that I don’t see a lot of people choosing between primary care and hospital medicine,” she says. “They’re thinking, ‘Do I want to do critical care, hospital medicine, or cardiology?’ Because the type of person who does hospital medicine is more attracted to that inpatient, acute environment.”

Dr. Horwitz agrees that the choice between a career in primary care and HM might not be as clear-cut as some detractors have suggested. Even so, she describes hospitalists as a “double-edged sword” for PCPs. “On the one hand, primary-care docs get paid so little for their outpatient visits that most need to see a high volume of patients in a day just to break even. So they have less and less time to go to the hospital to see hospitalizations,” Dr. Horwitz says. “The hospitalist movement was really a godsend in that respect, because it allowed primary-care docs to focus on their outpatient practice and not spend all that travel time going to the hospital.”

Other PCPs have lamented the erosion of their inpatient roles while recognizing that current economic realities are gradually pushing them out of the hospital. In fact, Dr. Horwitz says, PCPs often don’t know when their patients have been hospitalized, leading to a breakdown in the continuity of care. A weak primary-care infrastructure in a community, hospitalists say, can likewise imperil safe transitions. With the partitioning of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities, the potential for such miscommunications and lapses has clearly grown.

“We’re all in the same workforce; we’re all trying to take care of patients,” Dr. Heim says. “The discussion needs to be on how do we coordinate, not over turf wars.”

Signs of Life

Experts are focusing more on team-based approaches among the few potential short-term solutions, a common theme in HM circles. Advanced-practice registered nurses, physician assistants, and other providers can be trained more quickly than doctors, potentially extending the reach of primary care. In turn, the concept of team-based care could be beefed up during medical residencies.

Primary-care advocates say more equitable reimbursements also could help to ease the crisis, as would more federal support of residency training. But with many politicians focused on deficit reduction, new government incentives are debuting even as existing programs are being threatened or dismantled.

The Affordable Care Act, for example, more than doubled the capacity of the well-regarded National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayments to doctors who agree to practice in underserved communities. The law also created primary-care incentive payments that added $500 million to physician incomes in 2011. “So that’s a pretty strong message of value, and it’s some real value, too,” Dr. Phillips says.

—Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

The Affordable Care Act, however, cuts $155 billion to hospital payments over 10 years, adding to the downward pressure on reimbursements. And President Obama’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal trims an additional $1 billion, or 10%, from Medicare’s annual payments for patient care, which could impact graduate medical education as hospitals seek to balance out the cuts.

Amid the challenges, primary care is showing some encouraging signs of life. Medical school enrollments are on pace to increase by 30% over their 2002 levels within the next three to five years. In both 2010 and 2011, the number of U.S. medical graduates going into family medicine increased by roughly 10% (followed by a more modest increase of 1% this year). Residency matches in general internal medicine also have been climbing. Dr. Heim and others say it’s no coincidence that students’ interest in primary care began rising again amid public discussions on healthcare reform that focused on the value of primary care.

In the end, the profession’s fate could depend in large part on whether the affirmations continue this time around. “There are some rock stars and heroes of primary care that are not as well-known to medical students as they should be,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. Highlighting some of those individual leaders, Dr. Huang believes, might significantly improve the profession’s standing among students.

“We need a Michael Jordan of primary care,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

- Hofer AN, Abraham JM, Moscovice I. Expansion of coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and primary care utilization. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):69-89.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502.

- Henning Schumann, J. The doctor is out: young talent is turning away from primary care. The Atlantic; March 12, 2012.

It’s been about 15 years since the last surge of interest in primary care as a career, when U.S. medical graduates temporarily reversed a long decline by flocking to family medicine, general internal medicine, and pediatrics. Newly minted doctors responded enthusiastically to a widely held perception in the mid-1990s that primary care would be central to a brave new paradigm of managed healthcare delivery.

That profound change never materialized, and the primary-care workforce has since resumed a downward slide that is sounding alarm bells throughout the country. Even more distressing, the medical profession’s recent misfortunes have spread far beyond the doctor’s office.

“What we’re looking at now is that there’s a shortage of somewhere around 90,000 physicians in the next 10 years, increasing in the five years beyond that to 125,000 or more,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The association’s estimates suggest that the 10- and 15-year shortfalls will be split nearly evenly between primary care and other specialties.

Hospitalists could feel that widening gap as well. With increasing numbers of aging baby boomers reaching Medicare eligibility and 32 million Americans set to join the ranks of the insured by 2019 through the Affordable Care Act, primary care’s difficulties arguably are the closest to a full-blown crisis. “Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline,” began a 2009 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 And that was before an estimate suggesting that new insurance mandates will require an additional 4,307 to 6,940 primary-care physicians to meet demand before the end of the decade contributing about 15% to the expected shortfall.2

Why should hospitalists care about the fate of their counterparts? For starters, what’s good for outpatient providers is good for a sound healthcare system. Researchers have linked strong

primary care to lower overall spending, fewer health disparities, and higher quality of care.3

Hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) also are inexorably linked. They follow similar training and education pathways, and need each other to ensure safe transitions of care. And despite the evidence pointing to a slew of contributing factors, HM regularly is blamed for many of primary care’s mounting woes.

Based on well-functioning healthcare systems around the world, analysts say the ideal primary-care-to-specialty-care-provider ratio should be roughly 40:60 or 50:50. According to Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), only about 32% of physicians in the U.S. are practicing primary care. Unless something changes, that percentage will erode even further. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” Dr. Klink says.

Opinions differ on the extent of the current PCP shortage. Nevertheless, there is clearly a “huge maldistribution problem,” says Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center. Rural and underserved areas already are being shortchanged as more doctors locate in more affluent and desirable areas, he says.

That phenomenon is hardly unique to primary care, but Dr. Phillips says the deficit in frontline doctors could cause disproportionately more hardships in rural and underserved communities given the shrinking pipeline for medical trainees. A decade ago, almost a third of all medical graduates were placed into primary-care residency training slots. Now, he says, that figure is a bit less than 22%. “We can’t even replace the primary-care workforce we have now with that kind of output,” Dr. Phillips says.

Already, many doctors are no longer accepting new Medicaid or Medicare patients because their practices are losing money from low reimbursement rates. The Affordable Care Act’s significant expansion of insurance benefits, Dr. Grover says, will effectively accelerate the timetable of growing imbalances between supply and demand. “I think the challenge you face is, Will the ACA efforts to expand access fail because you’re giving people an insurance card but you have nobody there to take care of them?”

Reasons Aplenty

Some medical students simply aren’t interested in primary care. For the rest, however, interviews with doctors, analysts, and federal officials suggest that the pipeline has been battered throughout its length. Of all the contributing factors, Dr. Phillips says, the main one might be income disparity. In a 2009 study, the center found that the growing gulf in salaries between primary care and subspecialty medicine “cuts in half the likelihood that a student will choose to go into primary care,” he says. Over a career, that gap translates into a difference of $3.5 million. “It dissuades them strongly,” Dr. Phillips says.

At the same time, medical school tuitions have increased at a rate far outstripping the consumer price index. “What we found is that when you hit somewhere between $200,000 and $250,000 in debt, that’s where you see the dropoff really happen,” he says. “Because it becomes almost unfathomable that you can, on a primary-care income, pay off your debts without it severely cutting into your lifestyle.”

Lori Heim, MD, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a hospitalist at Scotland Memorial Hospital in Laurinburg, N.C., says the prevailing fee-for-service payment model has failed primary-care providers, requiring them to work more to meet soaring outpatient demand but reimbursing them less. “People talk about the hamster wheel,” she says. “And that has created more workplace dissatisfaction. Not only does it impact students, but it also impacts the number of primary-care physicians who want to stay in the community, practicing.”

Frederick Chen, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, can relate. “I came from community practice, where you’re seeing 30 to 35 patients a day, and the pressure was entirely on your productivity, and that’s not fun,” he says. “So we’re burning out a lot of primary-care physicians, and students are seeing that very easily.”

The larger theme, several doctors say, is one of perceived worth. Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., says she has to think holistically about her patients’ symptoms, medication lists, family history, home situation, and other factors during her limited time with them. She bristles at the notion that specialists might spend their time considering only one aspect of her patients’ care yet bill twice as much.

“Realistically, I am providing better value to the healthcare system than a specialist does, and yet we pay specialists much more,” she says. “And until that’s different, people go where the money is and they also go where the respect is, and I think it’s going to be very hard to recruit more people to primary care.”

Despite research pointing to financial concerns, lifestyle perceptions, and training inadequacies as key factors in the decline of primary care, perceptions that HM is poaching young talent have been hard to shake. A recent article in The Atlantic asserts that HM might be a “rational choice” given the profession’s more favorable training, lifestyle, and financial considerations.4 The author, a general internist, contrasts those enticements “to the realities of office practice: Fifteen-minute visits with patients on multiple medications, oodles of paperwork that cause office docs to run a gauntlet just to get through their day, and more documentation and regulatory burdens than ever before.”

Nevertheless, the article describes PCPs who resist hospitals’ calls to move to a hospitalist system as honorable “holdouts” who are committed to being directly involved in their patients’ care.

In her blog post at KevinMD.com, “Hospitalists are Killing Primary Care, and other Myths Debunked,” Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago, addresses those perceptions head-on. “If hospitalists did not exist, there would still be declining interest in primary care among medical students and residents,” she writes.

In a subsequent interview, Dr. Arora contends that both primary care and HM instead might be losing out to higher-paying subspecialties, especially the “ROAD” quartet of radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology, and dermatology. She also questions the notion that the professions draw from the same talent pool. “Anecdotally, I can tell you that I don’t see a lot of people choosing between primary care and hospital medicine,” she says. “They’re thinking, ‘Do I want to do critical care, hospital medicine, or cardiology?’ Because the type of person who does hospital medicine is more attracted to that inpatient, acute environment.”

Dr. Horwitz agrees that the choice between a career in primary care and HM might not be as clear-cut as some detractors have suggested. Even so, she describes hospitalists as a “double-edged sword” for PCPs. “On the one hand, primary-care docs get paid so little for their outpatient visits that most need to see a high volume of patients in a day just to break even. So they have less and less time to go to the hospital to see hospitalizations,” Dr. Horwitz says. “The hospitalist movement was really a godsend in that respect, because it allowed primary-care docs to focus on their outpatient practice and not spend all that travel time going to the hospital.”

Other PCPs have lamented the erosion of their inpatient roles while recognizing that current economic realities are gradually pushing them out of the hospital. In fact, Dr. Horwitz says, PCPs often don’t know when their patients have been hospitalized, leading to a breakdown in the continuity of care. A weak primary-care infrastructure in a community, hospitalists say, can likewise imperil safe transitions. With the partitioning of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities, the potential for such miscommunications and lapses has clearly grown.