User login

Championing preventive care in ObGyn: A tool to evaluate for useful medical apps

Personalizing care is at the heart of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2020–2021 President Dr. Eva Chalas’ initiative to “Revisit the Visit.” As obstetrician-gynecologists, we care for patients across the entirety of their life. This role gives us the opportunity to form long-term partnerships with women to address important preventive health care measures.

Dr. Chalas established a Presidential Task Force that identified 5 areas of preventive health that significantly influence the long-term morbidity of women: obesity, cardiovascular disease, preconception counseling, diabetes, and cancer risk. The annual visit can serve as a particularly impactful point of care to achieve specific preventive care objectives and offer mitigation strategies based on patient-specific risk factors. We are uniquely positioned to identify and initiate the conversation and subsequently manage, treat, and address these critical health areas.

Harnessing modern technology

To adopt these health topics into practice, we need improved, more effective tools both to increase productivity during the office visit and to provide more personalized care. Notably, the widespread adoption of and proliferation of mobile devices—and the medical apps accessible on them—is creating new and innovative ways to improve health and health care delivery. More than 90% of physicians use a smartphone at work, and 62% of smartphone users have used their device to gather health data.1

In addition, according to a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report, in 2017, 325,000 health care applications were available on smartphones; this equates to an expected 3.7 billion mobile health application downloads that year by 1.7 billion smartphone users worldwide.2 As of October 2020, 48,000-plus health apps were available on the iOS mobile operating system alone.3

For patients and clinicians, picking the most suitable apps can be challenging in the face of evolving clinical evidence, emerging privacy risks, functionality concerns, and the fact that apps constantly update and change. Many have relied on star rating systems and user reviews in app stores to guide their selection process despite mounting evidence that suggests that such evaluation methods are misleading, not always addressing such important parameters as usability, validity, security, and privacy.4,5

Approaches for evaluating medical apps

Many app evaluation frameworks have emerged, but none is universally accepted within the health care field.

The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) App Evaluation Model represents a comprehensive resource to consider when evaluating medical apps. It stratifies numerous variables into 5 levels that form a pyramid. In this model, background information forms the base of this pyramid and includes factors such as business model, credibility, cost, and advertising of the app. The top of the pyramid is comprised of data integration that considers data ownership and therapeutic alliance.6 Although this model is beneficial in that it provides a framework, it is not practical for point-of-care purposes as it offers no objective way to rate or score an app for quick and easy comparison.

The privately owned and operated Health On the Net (HON) Foundation is well known for its HONcode, an ethical standard for quality medical information on the internet. It uses 8 principles to certify a health website. However, the HON website itself states that it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of medical information presented by a site.7 Although HON certification by a website is a sign of good intention, it is not beneficial to the practicing clinician who is looking to use an app to directly assist in clinical care.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is another well-respected body that has delineated essential details to consider when using a health website. The AHRQ identifies features (similar to those of the APA pyramid and HONcode) for users to consider, such as credibility, content, design, and disclosures.8 However, this model too lacks a concise user-friendly evaluating system.

Although the FDA plans to apply some regulatory authority to the evaluation of a certain subset of high-risk mobile medical apps, it is not planning to evaluate or regulate many of the medical apps that clinicians use in daily practice. This leaves us, and our patients, to be guided by the principle of caveat emptor, or “let the buyer beware.”

Thus, Dr. Chalas’ Presidential Task Force carefully considered various resources to provide a useful tool that would help obstetrician-gynecologists objectively vet a medical app in practice.

Continue to: The Task Force’s recommended rubric...

The Task Force’s recommended rubric

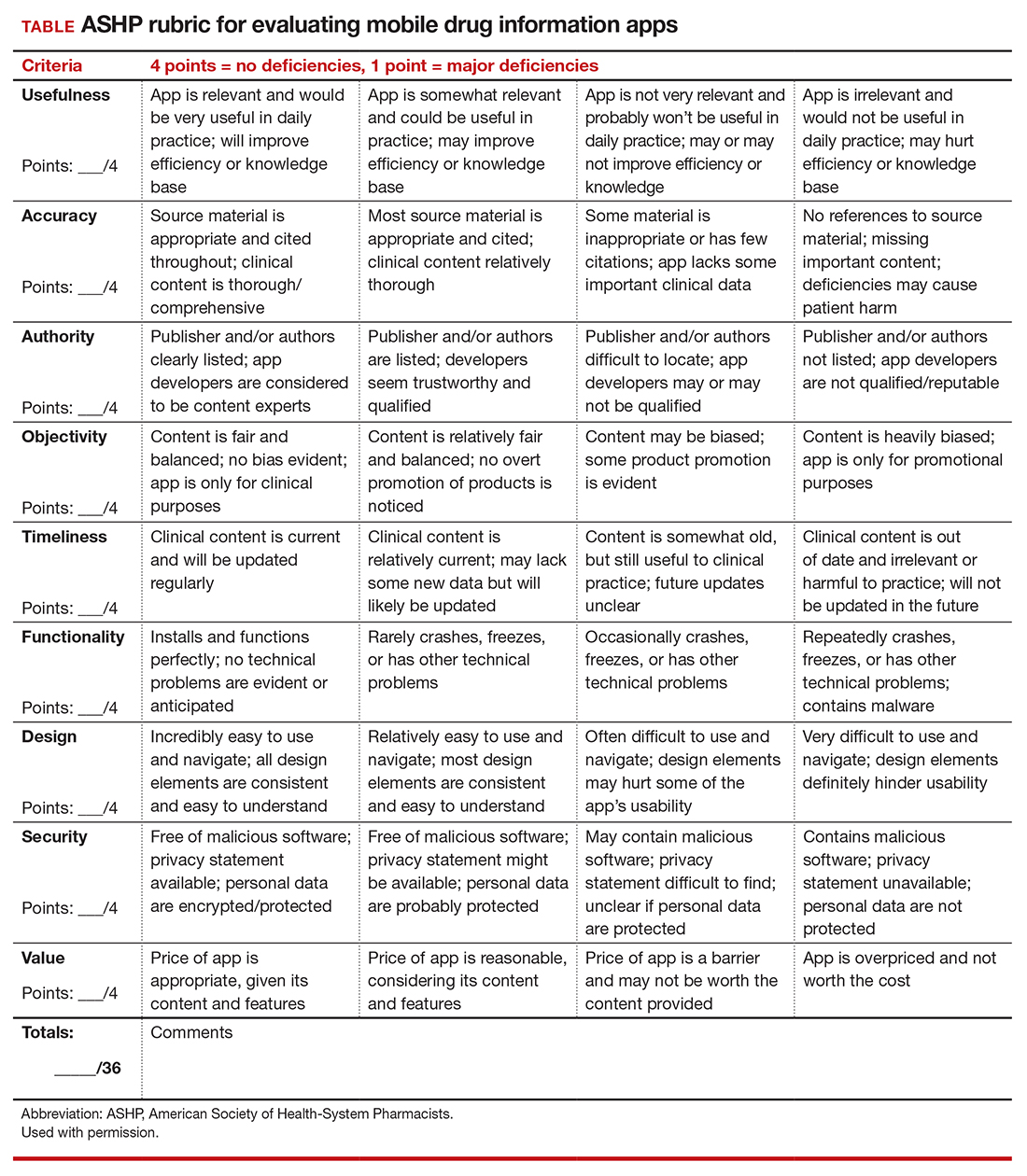

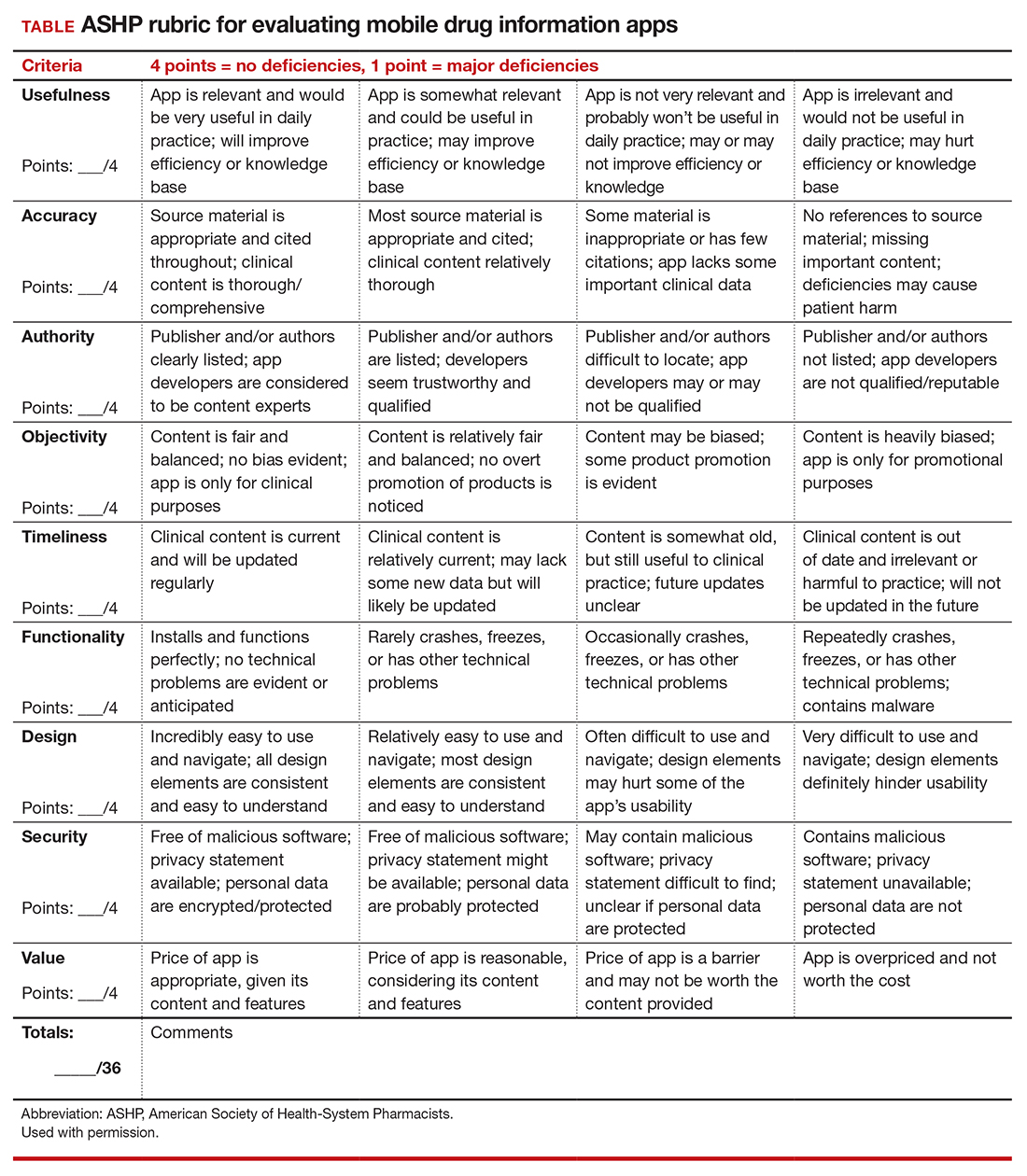

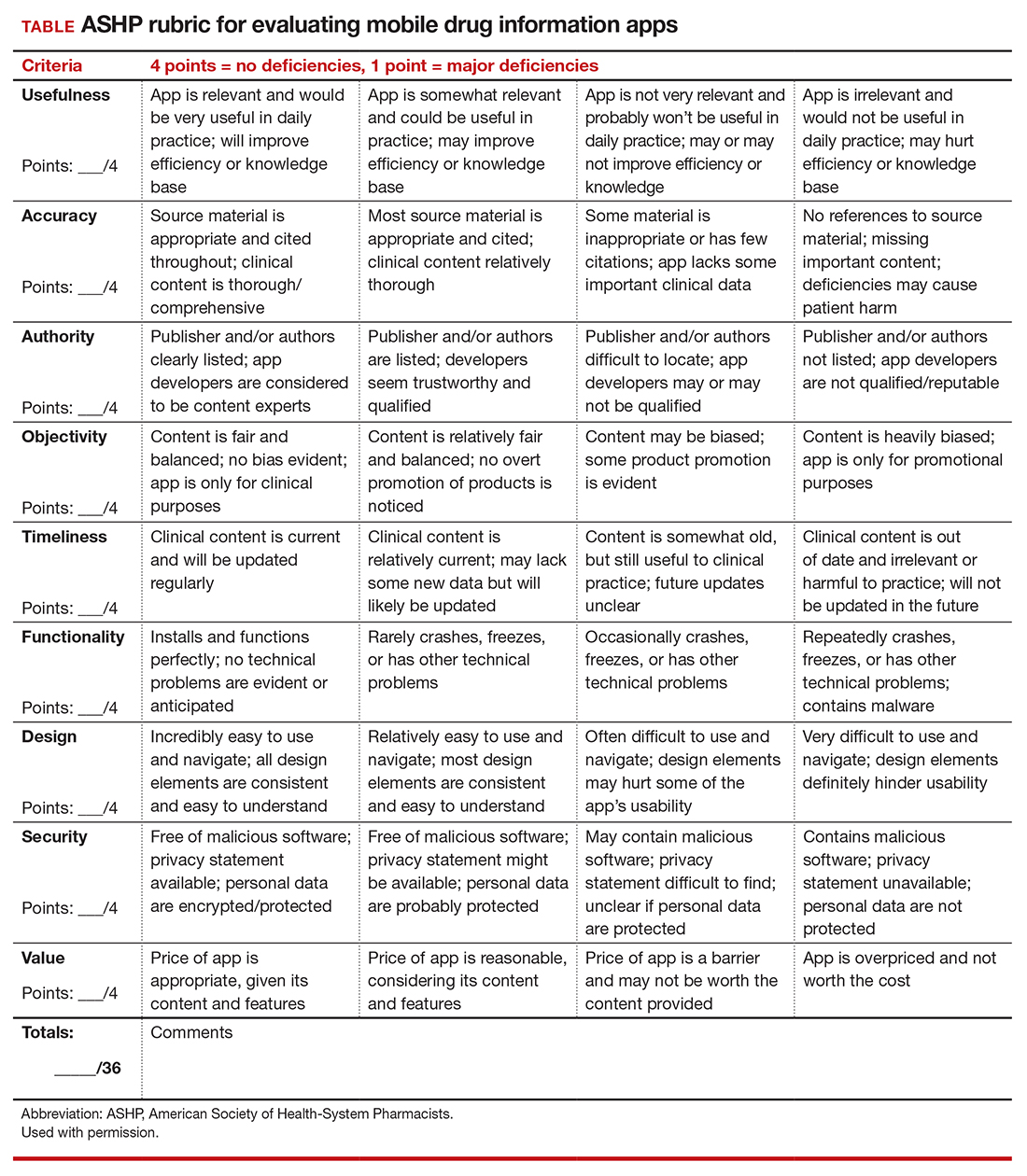

The rubric shown for evaluating mobile drug information apps was developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP). The ASHP rubric takes into account the criteria recognized by the APA pyramid, the HON Foundation, and the AHRQ and incorporates them into a user-friendly tool and scoring system that can be applied as an evaluation checklist.9 This tool is meant to aid clinicians in evaluating medical apps, but it ultimately is the user’s decision to determine if an app’s deficiencies should deter its use.

While all of the criteria are relevant and important, it is incumbent on us as medical experts to pay careful attention to the accuracy, authority, objectivity, timeliness, and security of any app we consider incorporating into clinical practice. A low score on these criteria would belie any perceived usefulness or value the app may have.

When applying the rubric to evaluate the quality of an app, we should be mindful of the primary user and which characteristics are more important than others to effect positive changes in health. For example, in addressing obesity, it is the patient who will be interacting with the app. Therefore, it’s important that the app should score, on a 1- to 4-point scale (1 point being major deficiencies, 4 points being no deficiencies), a 4 out of 4 on features like usefulness, functionality, and design. Coveted design features that enhance the user’s experience will appeal to patients and keep them engaged and motivated. However, when addressing a woman’s health with respect to cancer risk, the principal features on which the app should score 4 out of 4 would be authority, objectivity, timeliness, and accuracy.

In the upcoming articles in this series, a member of the Presidential Task Force will reference the ASHP rubric to guide clinicians in choosing apps to address one of the critical health areas with their patients. The author of the piece will highlight key features of an app to consider what would add the most value in incorporating its use in clinical practice.

It would be impossible to evaluate all health care apps even if we focused only on the medical apps relevant to obstetrics and gynecology. There is much value in having a framework for efficiently measuring an app’s benefit in clinical practice. The objective of this article series is to help clinicians Revisit the Visit by providing an effective tool to evaluate a medical app. ●

- Mobius MD website. 11 Surprising mobile health statistics. http://www.mobius.md/blog/2019/03/11-mobile-health -statistics/. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. Device software functions including medical applications. November 5, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center -excellence/device-software-functions-including-mobile -medical-applications. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Statista website. Number of mHealth apps available in the Apple App Store from 1st quarter 2015 to 4th quarter 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/779910/health-apps -available-ios-worldwide/. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- Campbell L. Using star ratings to choose a medical app? There’s a better way. Healthline website. Updated August 3, 2018. http://healthline.com/health-news/using-ratings-to -choose-medical-app-theres-a-better-way. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Levine DM, Co Z, Newmark LP, et al. Design and testing of a mobile health application rating tool. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:74.

- Torous JB, Chan SR, Gipson SY, et al. A hierarchical framework for evaluation and informed decision making regarding smartphone apps for clinical care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:498-500.

- Health On the Net website. The commitment to reliable health and medical information on the internet. https:// www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/Visitor/visitor.html. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Assessing the quality of internet health information. June 1999. http:// www.ahrq.gov/research/data/infoqual.html. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Hanrahan C, Aungst TD, Cole S. Evaluating mobile medical applications. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists eReports. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/store-files /mobile-medical-apps.ashx. Accessed January 22, 2021.

Personalizing care is at the heart of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2020–2021 President Dr. Eva Chalas’ initiative to “Revisit the Visit.” As obstetrician-gynecologists, we care for patients across the entirety of their life. This role gives us the opportunity to form long-term partnerships with women to address important preventive health care measures.

Dr. Chalas established a Presidential Task Force that identified 5 areas of preventive health that significantly influence the long-term morbidity of women: obesity, cardiovascular disease, preconception counseling, diabetes, and cancer risk. The annual visit can serve as a particularly impactful point of care to achieve specific preventive care objectives and offer mitigation strategies based on patient-specific risk factors. We are uniquely positioned to identify and initiate the conversation and subsequently manage, treat, and address these critical health areas.

Harnessing modern technology

To adopt these health topics into practice, we need improved, more effective tools both to increase productivity during the office visit and to provide more personalized care. Notably, the widespread adoption of and proliferation of mobile devices—and the medical apps accessible on them—is creating new and innovative ways to improve health and health care delivery. More than 90% of physicians use a smartphone at work, and 62% of smartphone users have used their device to gather health data.1

In addition, according to a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report, in 2017, 325,000 health care applications were available on smartphones; this equates to an expected 3.7 billion mobile health application downloads that year by 1.7 billion smartphone users worldwide.2 As of October 2020, 48,000-plus health apps were available on the iOS mobile operating system alone.3

For patients and clinicians, picking the most suitable apps can be challenging in the face of evolving clinical evidence, emerging privacy risks, functionality concerns, and the fact that apps constantly update and change. Many have relied on star rating systems and user reviews in app stores to guide their selection process despite mounting evidence that suggests that such evaluation methods are misleading, not always addressing such important parameters as usability, validity, security, and privacy.4,5

Approaches for evaluating medical apps

Many app evaluation frameworks have emerged, but none is universally accepted within the health care field.

The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) App Evaluation Model represents a comprehensive resource to consider when evaluating medical apps. It stratifies numerous variables into 5 levels that form a pyramid. In this model, background information forms the base of this pyramid and includes factors such as business model, credibility, cost, and advertising of the app. The top of the pyramid is comprised of data integration that considers data ownership and therapeutic alliance.6 Although this model is beneficial in that it provides a framework, it is not practical for point-of-care purposes as it offers no objective way to rate or score an app for quick and easy comparison.

The privately owned and operated Health On the Net (HON) Foundation is well known for its HONcode, an ethical standard for quality medical information on the internet. It uses 8 principles to certify a health website. However, the HON website itself states that it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of medical information presented by a site.7 Although HON certification by a website is a sign of good intention, it is not beneficial to the practicing clinician who is looking to use an app to directly assist in clinical care.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is another well-respected body that has delineated essential details to consider when using a health website. The AHRQ identifies features (similar to those of the APA pyramid and HONcode) for users to consider, such as credibility, content, design, and disclosures.8 However, this model too lacks a concise user-friendly evaluating system.

Although the FDA plans to apply some regulatory authority to the evaluation of a certain subset of high-risk mobile medical apps, it is not planning to evaluate or regulate many of the medical apps that clinicians use in daily practice. This leaves us, and our patients, to be guided by the principle of caveat emptor, or “let the buyer beware.”

Thus, Dr. Chalas’ Presidential Task Force carefully considered various resources to provide a useful tool that would help obstetrician-gynecologists objectively vet a medical app in practice.

Continue to: The Task Force’s recommended rubric...

The Task Force’s recommended rubric

The rubric shown for evaluating mobile drug information apps was developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP). The ASHP rubric takes into account the criteria recognized by the APA pyramid, the HON Foundation, and the AHRQ and incorporates them into a user-friendly tool and scoring system that can be applied as an evaluation checklist.9 This tool is meant to aid clinicians in evaluating medical apps, but it ultimately is the user’s decision to determine if an app’s deficiencies should deter its use.

While all of the criteria are relevant and important, it is incumbent on us as medical experts to pay careful attention to the accuracy, authority, objectivity, timeliness, and security of any app we consider incorporating into clinical practice. A low score on these criteria would belie any perceived usefulness or value the app may have.

When applying the rubric to evaluate the quality of an app, we should be mindful of the primary user and which characteristics are more important than others to effect positive changes in health. For example, in addressing obesity, it is the patient who will be interacting with the app. Therefore, it’s important that the app should score, on a 1- to 4-point scale (1 point being major deficiencies, 4 points being no deficiencies), a 4 out of 4 on features like usefulness, functionality, and design. Coveted design features that enhance the user’s experience will appeal to patients and keep them engaged and motivated. However, when addressing a woman’s health with respect to cancer risk, the principal features on which the app should score 4 out of 4 would be authority, objectivity, timeliness, and accuracy.

In the upcoming articles in this series, a member of the Presidential Task Force will reference the ASHP rubric to guide clinicians in choosing apps to address one of the critical health areas with their patients. The author of the piece will highlight key features of an app to consider what would add the most value in incorporating its use in clinical practice.

It would be impossible to evaluate all health care apps even if we focused only on the medical apps relevant to obstetrics and gynecology. There is much value in having a framework for efficiently measuring an app’s benefit in clinical practice. The objective of this article series is to help clinicians Revisit the Visit by providing an effective tool to evaluate a medical app. ●

Personalizing care is at the heart of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2020–2021 President Dr. Eva Chalas’ initiative to “Revisit the Visit.” As obstetrician-gynecologists, we care for patients across the entirety of their life. This role gives us the opportunity to form long-term partnerships with women to address important preventive health care measures.

Dr. Chalas established a Presidential Task Force that identified 5 areas of preventive health that significantly influence the long-term morbidity of women: obesity, cardiovascular disease, preconception counseling, diabetes, and cancer risk. The annual visit can serve as a particularly impactful point of care to achieve specific preventive care objectives and offer mitigation strategies based on patient-specific risk factors. We are uniquely positioned to identify and initiate the conversation and subsequently manage, treat, and address these critical health areas.

Harnessing modern technology

To adopt these health topics into practice, we need improved, more effective tools both to increase productivity during the office visit and to provide more personalized care. Notably, the widespread adoption of and proliferation of mobile devices—and the medical apps accessible on them—is creating new and innovative ways to improve health and health care delivery. More than 90% of physicians use a smartphone at work, and 62% of smartphone users have used their device to gather health data.1

In addition, according to a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report, in 2017, 325,000 health care applications were available on smartphones; this equates to an expected 3.7 billion mobile health application downloads that year by 1.7 billion smartphone users worldwide.2 As of October 2020, 48,000-plus health apps were available on the iOS mobile operating system alone.3

For patients and clinicians, picking the most suitable apps can be challenging in the face of evolving clinical evidence, emerging privacy risks, functionality concerns, and the fact that apps constantly update and change. Many have relied on star rating systems and user reviews in app stores to guide their selection process despite mounting evidence that suggests that such evaluation methods are misleading, not always addressing such important parameters as usability, validity, security, and privacy.4,5

Approaches for evaluating medical apps

Many app evaluation frameworks have emerged, but none is universally accepted within the health care field.

The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) App Evaluation Model represents a comprehensive resource to consider when evaluating medical apps. It stratifies numerous variables into 5 levels that form a pyramid. In this model, background information forms the base of this pyramid and includes factors such as business model, credibility, cost, and advertising of the app. The top of the pyramid is comprised of data integration that considers data ownership and therapeutic alliance.6 Although this model is beneficial in that it provides a framework, it is not practical for point-of-care purposes as it offers no objective way to rate or score an app for quick and easy comparison.

The privately owned and operated Health On the Net (HON) Foundation is well known for its HONcode, an ethical standard for quality medical information on the internet. It uses 8 principles to certify a health website. However, the HON website itself states that it cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of medical information presented by a site.7 Although HON certification by a website is a sign of good intention, it is not beneficial to the practicing clinician who is looking to use an app to directly assist in clinical care.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is another well-respected body that has delineated essential details to consider when using a health website. The AHRQ identifies features (similar to those of the APA pyramid and HONcode) for users to consider, such as credibility, content, design, and disclosures.8 However, this model too lacks a concise user-friendly evaluating system.

Although the FDA plans to apply some regulatory authority to the evaluation of a certain subset of high-risk mobile medical apps, it is not planning to evaluate or regulate many of the medical apps that clinicians use in daily practice. This leaves us, and our patients, to be guided by the principle of caveat emptor, or “let the buyer beware.”

Thus, Dr. Chalas’ Presidential Task Force carefully considered various resources to provide a useful tool that would help obstetrician-gynecologists objectively vet a medical app in practice.

Continue to: The Task Force’s recommended rubric...

The Task Force’s recommended rubric

The rubric shown for evaluating mobile drug information apps was developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP). The ASHP rubric takes into account the criteria recognized by the APA pyramid, the HON Foundation, and the AHRQ and incorporates them into a user-friendly tool and scoring system that can be applied as an evaluation checklist.9 This tool is meant to aid clinicians in evaluating medical apps, but it ultimately is the user’s decision to determine if an app’s deficiencies should deter its use.

While all of the criteria are relevant and important, it is incumbent on us as medical experts to pay careful attention to the accuracy, authority, objectivity, timeliness, and security of any app we consider incorporating into clinical practice. A low score on these criteria would belie any perceived usefulness or value the app may have.

When applying the rubric to evaluate the quality of an app, we should be mindful of the primary user and which characteristics are more important than others to effect positive changes in health. For example, in addressing obesity, it is the patient who will be interacting with the app. Therefore, it’s important that the app should score, on a 1- to 4-point scale (1 point being major deficiencies, 4 points being no deficiencies), a 4 out of 4 on features like usefulness, functionality, and design. Coveted design features that enhance the user’s experience will appeal to patients and keep them engaged and motivated. However, when addressing a woman’s health with respect to cancer risk, the principal features on which the app should score 4 out of 4 would be authority, objectivity, timeliness, and accuracy.

In the upcoming articles in this series, a member of the Presidential Task Force will reference the ASHP rubric to guide clinicians in choosing apps to address one of the critical health areas with their patients. The author of the piece will highlight key features of an app to consider what would add the most value in incorporating its use in clinical practice.

It would be impossible to evaluate all health care apps even if we focused only on the medical apps relevant to obstetrics and gynecology. There is much value in having a framework for efficiently measuring an app’s benefit in clinical practice. The objective of this article series is to help clinicians Revisit the Visit by providing an effective tool to evaluate a medical app. ●

- Mobius MD website. 11 Surprising mobile health statistics. http://www.mobius.md/blog/2019/03/11-mobile-health -statistics/. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. Device software functions including medical applications. November 5, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center -excellence/device-software-functions-including-mobile -medical-applications. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Statista website. Number of mHealth apps available in the Apple App Store from 1st quarter 2015 to 4th quarter 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/779910/health-apps -available-ios-worldwide/. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- Campbell L. Using star ratings to choose a medical app? There’s a better way. Healthline website. Updated August 3, 2018. http://healthline.com/health-news/using-ratings-to -choose-medical-app-theres-a-better-way. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Levine DM, Co Z, Newmark LP, et al. Design and testing of a mobile health application rating tool. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:74.

- Torous JB, Chan SR, Gipson SY, et al. A hierarchical framework for evaluation and informed decision making regarding smartphone apps for clinical care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:498-500.

- Health On the Net website. The commitment to reliable health and medical information on the internet. https:// www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/Visitor/visitor.html. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Assessing the quality of internet health information. June 1999. http:// www.ahrq.gov/research/data/infoqual.html. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Hanrahan C, Aungst TD, Cole S. Evaluating mobile medical applications. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists eReports. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/store-files /mobile-medical-apps.ashx. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- Mobius MD website. 11 Surprising mobile health statistics. http://www.mobius.md/blog/2019/03/11-mobile-health -statistics/. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. Device software functions including medical applications. November 5, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center -excellence/device-software-functions-including-mobile -medical-applications. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Statista website. Number of mHealth apps available in the Apple App Store from 1st quarter 2015 to 4th quarter 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/779910/health-apps -available-ios-worldwide/. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- Campbell L. Using star ratings to choose a medical app? There’s a better way. Healthline website. Updated August 3, 2018. http://healthline.com/health-news/using-ratings-to -choose-medical-app-theres-a-better-way. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Levine DM, Co Z, Newmark LP, et al. Design and testing of a mobile health application rating tool. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:74.

- Torous JB, Chan SR, Gipson SY, et al. A hierarchical framework for evaluation and informed decision making regarding smartphone apps for clinical care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:498-500.

- Health On the Net website. The commitment to reliable health and medical information on the internet. https:// www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/Visitor/visitor.html. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Assessing the quality of internet health information. June 1999. http:// www.ahrq.gov/research/data/infoqual.html. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Hanrahan C, Aungst TD, Cole S. Evaluating mobile medical applications. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists eReports. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/store-files /mobile-medical-apps.ashx. Accessed January 22, 2021.

A reliable rubric for evaluating medical apps

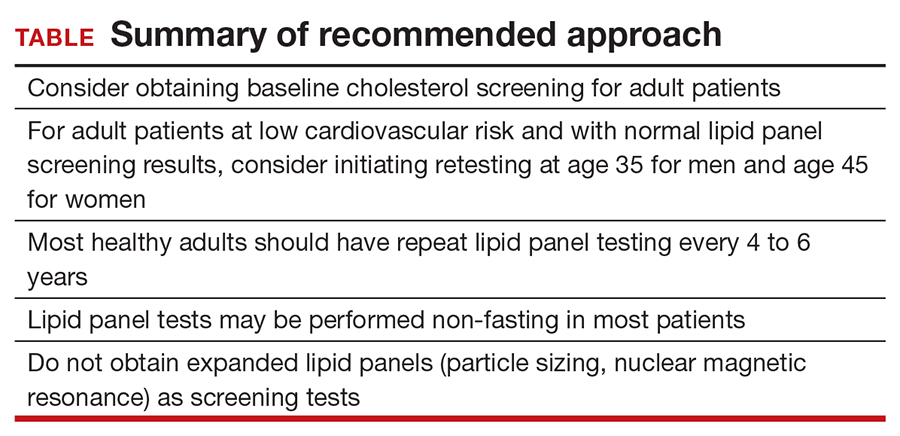

To help ObGyns evaluate mobile apps for use in clinical practice, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Presidential Task Force of Dr. Eva Chalas recommends a quantitative rubric that was developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) for evaluating drug information apps (TABLE).1 Criteria are graded on a point scale of 1 to 4, with 1 point indicating major deficiencies and 4 points indicating no deficiencies.

The ASHP used the following criteria in evaluating mobile apps:

- Usefulness: the app’s overall usefulness in a particular practice setting

- Accuracy: overall accuracy of the app should be thoroughly examined

- Authority: it is critical to assess authority or authorship to determine that the developers are reputable, qualified, and authoritative enough to create the medical content in question

- Objectivity: to determine if content is fair, balanced, and unbiased

- Timeliness: given that medical information is continually changing, an app must be evaluated based on the timeliness of its content

- Functionality: how the app downloads, deploys, and operates across devices and software platforms (that is, iOS, Android)

- Design: well-designed apps are generally more user friendly and, therefore, useful. They should require minimal or no training and have easily discernible buttons, a clean and uncluttered format, consistent graphics layout, terminology appropriate for the intended audience, streamlined navigation without extraneous steps/gestures, appropriate-sized text, and sufficient white space to improve readability.

- Security: Many apps collect a wide array of personal and device data. Collected data has the potential for being sold to third parties for marketing and advertising purposes. Apps should disclose their privacy policy and provide an explanation as to why personal data are being collected. If personal identifiable information (PII) is collected, then the app should be encrypted. If protected health information (PHI) is collected, the app must follow compliance with HIPAA/HITECH (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act/Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act). Additionally, apps should not compromise the security or functionality of the mobile device being used.

- Value: appropriateness of an app's cost. ●

- Hanrahan C, Aungst TD, Cole S. Evaluating mobile medical applications. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists eReports. https://www.ashp .org/-/media/store-files/mobile-medical-apps. ashx. Accessed January 22, 2021.

To help ObGyns evaluate mobile apps for use in clinical practice, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Presidential Task Force of Dr. Eva Chalas recommends a quantitative rubric that was developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) for evaluating drug information apps (TABLE).1 Criteria are graded on a point scale of 1 to 4, with 1 point indicating major deficiencies and 4 points indicating no deficiencies.

The ASHP used the following criteria in evaluating mobile apps:

- Usefulness: the app’s overall usefulness in a particular practice setting

- Accuracy: overall accuracy of the app should be thoroughly examined

- Authority: it is critical to assess authority or authorship to determine that the developers are reputable, qualified, and authoritative enough to create the medical content in question

- Objectivity: to determine if content is fair, balanced, and unbiased

- Timeliness: given that medical information is continually changing, an app must be evaluated based on the timeliness of its content

- Functionality: how the app downloads, deploys, and operates across devices and software platforms (that is, iOS, Android)

- Design: well-designed apps are generally more user friendly and, therefore, useful. They should require minimal or no training and have easily discernible buttons, a clean and uncluttered format, consistent graphics layout, terminology appropriate for the intended audience, streamlined navigation without extraneous steps/gestures, appropriate-sized text, and sufficient white space to improve readability.

- Security: Many apps collect a wide array of personal and device data. Collected data has the potential for being sold to third parties for marketing and advertising purposes. Apps should disclose their privacy policy and provide an explanation as to why personal data are being collected. If personal identifiable information (PII) is collected, then the app should be encrypted. If protected health information (PHI) is collected, the app must follow compliance with HIPAA/HITECH (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act/Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act). Additionally, apps should not compromise the security or functionality of the mobile device being used.

- Value: appropriateness of an app's cost. ●

To help ObGyns evaluate mobile apps for use in clinical practice, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Presidential Task Force of Dr. Eva Chalas recommends a quantitative rubric that was developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) for evaluating drug information apps (TABLE).1 Criteria are graded on a point scale of 1 to 4, with 1 point indicating major deficiencies and 4 points indicating no deficiencies.

The ASHP used the following criteria in evaluating mobile apps:

- Usefulness: the app’s overall usefulness in a particular practice setting

- Accuracy: overall accuracy of the app should be thoroughly examined

- Authority: it is critical to assess authority or authorship to determine that the developers are reputable, qualified, and authoritative enough to create the medical content in question

- Objectivity: to determine if content is fair, balanced, and unbiased

- Timeliness: given that medical information is continually changing, an app must be evaluated based on the timeliness of its content

- Functionality: how the app downloads, deploys, and operates across devices and software platforms (that is, iOS, Android)

- Design: well-designed apps are generally more user friendly and, therefore, useful. They should require minimal or no training and have easily discernible buttons, a clean and uncluttered format, consistent graphics layout, terminology appropriate for the intended audience, streamlined navigation without extraneous steps/gestures, appropriate-sized text, and sufficient white space to improve readability.

- Security: Many apps collect a wide array of personal and device data. Collected data has the potential for being sold to third parties for marketing and advertising purposes. Apps should disclose their privacy policy and provide an explanation as to why personal data are being collected. If personal identifiable information (PII) is collected, then the app should be encrypted. If protected health information (PHI) is collected, the app must follow compliance with HIPAA/HITECH (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act/Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act). Additionally, apps should not compromise the security or functionality of the mobile device being used.

- Value: appropriateness of an app's cost. ●

- Hanrahan C, Aungst TD, Cole S. Evaluating mobile medical applications. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists eReports. https://www.ashp .org/-/media/store-files/mobile-medical-apps. ashx. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- Hanrahan C, Aungst TD, Cole S. Evaluating mobile medical applications. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists eReports. https://www.ashp .org/-/media/store-files/mobile-medical-apps. ashx. Accessed January 22, 2021.

Online patient reviews and HIPAA

In 2013, a California hospital paid $275,000 to settle claims that it violated the HIPAA privacy rule when it disclosed a patient’s health information in response to a negative online review. More recently, a Texas dental practice paid a substantial fine to the Department of Health & Human Services, which enforces HIPAA, after it responded to unfavorable Yelp reviews with patient names and details of their health conditions, treatment plans, and cost information. In addition to the fine, the practice agreed to 2 years of monitoring by HHS for compliance with HIPAA rules.

Most physicians have had the unpleasant experience of finding a negative online review from a disgruntled patient or family member. Some are justified, many are not; either way, your first impulse will often be to post a response – but that is almost always a bad idea. “Social media is not the place for providers to discuss a patient’s care,” an HHS official said in a statement issued about the dental practice case in 2016. “Doctors and dentists must think carefully about patient privacy before responding to online reviews.”

Any information that could be used to identify a patient is a HIPAA breach. This is true even if the patient has already disclosed information, because doing so does not nullify their HIPAA rights, and HIPAA provides no exceptions for responses. Even acknowledging that the reviewer was in fact your patient could, in some cases, be considered a violation.

Responding to good reviews can get you in trouble too, for the same reasons. In 2016, a physical therapy practice paid a $25,000 fine after it posted patient testimonials, “including full names and full-face photographic images to its website without obtaining valid, HIPAA-compliant authorizations.”

And by the way, most malpractice policies specifically exclude disciplinary fines and settlements from coverage.

All of that said,

- Ignore them. This is your best choice most of the time. Most negative reviews have minimal impact and simply do not deserve a response; responding may pour fuel on the fire. Besides, an occasional negative review actually lends credibility to a reviewing site and to the positive reviews posted on that site. Polls show that readers are suspicious of sites that contain only rave reviews. They assume such reviews have been “whitewashed” – or just fabricated.

- Solicit more reviews to that site. The more you can obtain, the less impact any complaints will have, since you know the overwhelming majority of your patients are happy with your care and will post a positive review if asked. Solicit them on your website, on social media, or in your email reminders. To be clear, you must encourage reviews from all patients, whether they have had a positive experience or not. If you invite only the satisfied ones, you are “filtering,” which can be perceived as false or deceptive advertising. (Google calls it “review-gating,” and according to their guidelines, if they catch you doing it they will remove all of your reviews.)

- Respond politely. In those rare cases where you feel you must respond, do so without acknowledging that the individual was a patient, or disclosing any information that may be linked to the patient. For example, you can say that you provide excellent and appropriate care, or describe your general policies. Be polite, professional, and sensitive to the patient’s position. Readers tend to respect and sympathize with a doctor who responds in a professional, respectful manner and does not trash the complainant in retaliation.

- Take the discussion offline. Sometimes the person posting the review is just frustrated and wants to be heard. In those cases, consider contacting the patient and offering to discuss their concerns privately. If you cannot resolve your differences, try to get the patient’s written permission to post a response to their review. If they refuse, you can explain that, thereby capturing the moral high ground.

If the review contains false or defamatory content, that’s a different situation entirely; you will probably need to consult your attorney.

Regardless of how you handle negative reviews, be sure to learn from them. Your critics, as the song goes, are not always evil – and not always wrong. Complaints give you a chance to review your office policies and procedures and your own conduct, identify weaknesses, and make changes as necessary. At the very least, the exercise will help you to avoid similar complaints in the future. Don’t let valuable opportunities like that pass you by.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In 2013, a California hospital paid $275,000 to settle claims that it violated the HIPAA privacy rule when it disclosed a patient’s health information in response to a negative online review. More recently, a Texas dental practice paid a substantial fine to the Department of Health & Human Services, which enforces HIPAA, after it responded to unfavorable Yelp reviews with patient names and details of their health conditions, treatment plans, and cost information. In addition to the fine, the practice agreed to 2 years of monitoring by HHS for compliance with HIPAA rules.

Most physicians have had the unpleasant experience of finding a negative online review from a disgruntled patient or family member. Some are justified, many are not; either way, your first impulse will often be to post a response – but that is almost always a bad idea. “Social media is not the place for providers to discuss a patient’s care,” an HHS official said in a statement issued about the dental practice case in 2016. “Doctors and dentists must think carefully about patient privacy before responding to online reviews.”

Any information that could be used to identify a patient is a HIPAA breach. This is true even if the patient has already disclosed information, because doing so does not nullify their HIPAA rights, and HIPAA provides no exceptions for responses. Even acknowledging that the reviewer was in fact your patient could, in some cases, be considered a violation.

Responding to good reviews can get you in trouble too, for the same reasons. In 2016, a physical therapy practice paid a $25,000 fine after it posted patient testimonials, “including full names and full-face photographic images to its website without obtaining valid, HIPAA-compliant authorizations.”

And by the way, most malpractice policies specifically exclude disciplinary fines and settlements from coverage.

All of that said,

- Ignore them. This is your best choice most of the time. Most negative reviews have minimal impact and simply do not deserve a response; responding may pour fuel on the fire. Besides, an occasional negative review actually lends credibility to a reviewing site and to the positive reviews posted on that site. Polls show that readers are suspicious of sites that contain only rave reviews. They assume such reviews have been “whitewashed” – or just fabricated.

- Solicit more reviews to that site. The more you can obtain, the less impact any complaints will have, since you know the overwhelming majority of your patients are happy with your care and will post a positive review if asked. Solicit them on your website, on social media, or in your email reminders. To be clear, you must encourage reviews from all patients, whether they have had a positive experience or not. If you invite only the satisfied ones, you are “filtering,” which can be perceived as false or deceptive advertising. (Google calls it “review-gating,” and according to their guidelines, if they catch you doing it they will remove all of your reviews.)

- Respond politely. In those rare cases where you feel you must respond, do so without acknowledging that the individual was a patient, or disclosing any information that may be linked to the patient. For example, you can say that you provide excellent and appropriate care, or describe your general policies. Be polite, professional, and sensitive to the patient’s position. Readers tend to respect and sympathize with a doctor who responds in a professional, respectful manner and does not trash the complainant in retaliation.

- Take the discussion offline. Sometimes the person posting the review is just frustrated and wants to be heard. In those cases, consider contacting the patient and offering to discuss their concerns privately. If you cannot resolve your differences, try to get the patient’s written permission to post a response to their review. If they refuse, you can explain that, thereby capturing the moral high ground.

If the review contains false or defamatory content, that’s a different situation entirely; you will probably need to consult your attorney.

Regardless of how you handle negative reviews, be sure to learn from them. Your critics, as the song goes, are not always evil – and not always wrong. Complaints give you a chance to review your office policies and procedures and your own conduct, identify weaknesses, and make changes as necessary. At the very least, the exercise will help you to avoid similar complaints in the future. Don’t let valuable opportunities like that pass you by.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In 2013, a California hospital paid $275,000 to settle claims that it violated the HIPAA privacy rule when it disclosed a patient’s health information in response to a negative online review. More recently, a Texas dental practice paid a substantial fine to the Department of Health & Human Services, which enforces HIPAA, after it responded to unfavorable Yelp reviews with patient names and details of their health conditions, treatment plans, and cost information. In addition to the fine, the practice agreed to 2 years of monitoring by HHS for compliance with HIPAA rules.

Most physicians have had the unpleasant experience of finding a negative online review from a disgruntled patient or family member. Some are justified, many are not; either way, your first impulse will often be to post a response – but that is almost always a bad idea. “Social media is not the place for providers to discuss a patient’s care,” an HHS official said in a statement issued about the dental practice case in 2016. “Doctors and dentists must think carefully about patient privacy before responding to online reviews.”

Any information that could be used to identify a patient is a HIPAA breach. This is true even if the patient has already disclosed information, because doing so does not nullify their HIPAA rights, and HIPAA provides no exceptions for responses. Even acknowledging that the reviewer was in fact your patient could, in some cases, be considered a violation.

Responding to good reviews can get you in trouble too, for the same reasons. In 2016, a physical therapy practice paid a $25,000 fine after it posted patient testimonials, “including full names and full-face photographic images to its website without obtaining valid, HIPAA-compliant authorizations.”

And by the way, most malpractice policies specifically exclude disciplinary fines and settlements from coverage.

All of that said,

- Ignore them. This is your best choice most of the time. Most negative reviews have minimal impact and simply do not deserve a response; responding may pour fuel on the fire. Besides, an occasional negative review actually lends credibility to a reviewing site and to the positive reviews posted on that site. Polls show that readers are suspicious of sites that contain only rave reviews. They assume such reviews have been “whitewashed” – or just fabricated.

- Solicit more reviews to that site. The more you can obtain, the less impact any complaints will have, since you know the overwhelming majority of your patients are happy with your care and will post a positive review if asked. Solicit them on your website, on social media, or in your email reminders. To be clear, you must encourage reviews from all patients, whether they have had a positive experience or not. If you invite only the satisfied ones, you are “filtering,” which can be perceived as false or deceptive advertising. (Google calls it “review-gating,” and according to their guidelines, if they catch you doing it they will remove all of your reviews.)

- Respond politely. In those rare cases where you feel you must respond, do so without acknowledging that the individual was a patient, or disclosing any information that may be linked to the patient. For example, you can say that you provide excellent and appropriate care, or describe your general policies. Be polite, professional, and sensitive to the patient’s position. Readers tend to respect and sympathize with a doctor who responds in a professional, respectful manner and does not trash the complainant in retaliation.

- Take the discussion offline. Sometimes the person posting the review is just frustrated and wants to be heard. In those cases, consider contacting the patient and offering to discuss their concerns privately. If you cannot resolve your differences, try to get the patient’s written permission to post a response to their review. If they refuse, you can explain that, thereby capturing the moral high ground.

If the review contains false or defamatory content, that’s a different situation entirely; you will probably need to consult your attorney.

Regardless of how you handle negative reviews, be sure to learn from them. Your critics, as the song goes, are not always evil – and not always wrong. Complaints give you a chance to review your office policies and procedures and your own conduct, identify weaknesses, and make changes as necessary. At the very least, the exercise will help you to avoid similar complaints in the future. Don’t let valuable opportunities like that pass you by.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

2021 Update on cervical disease

Infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) is an essential step in the development of cervical cancer and its precursors, as well as in several other cancers, including oropharyngeal, vulvar, vaginal, anal, and penile cancers. At least 13 HPV strains, known collectively as hrHPV, have been associated with cervical cancer, in addition to more than 150 low-risk HPV types that have not been associated with cancer (for example, HPV 6 and 11).1 Up to 80% of women (and most men, although men are not tested routinely) will become infected with at least one of the high-risk HPV types throughout their lives, although in most cases these infections will be transient and have no clinical impact for the patient. Patients who test positive consecutively over time for hrHPV, and especially those who test positive for one of the most virulent HPV types (HPV 16 or 18), have a higher risk of developing cervical cancer or precancer. In addition, many patients who acquire HPV at a young age may “clear” the infection, which usually means that the virus becomes inactive; however, often, for unknown reasons, the virus can be reactivated in some women later in life.

This knowledge of the natural history of HPV has led to improved approaches to cervical cancer prevention, which relies on a combined strategy that includes vaccinating as many children and young adults as possible against hrHPV, screening and triaging approaches that use HPV-based tests, and applying risk-based evaluation for abnormal screening results. New guidelines and information address the best approaches to each of these aspects of cervical cancer prevention, which we review here.

HPV vaccination: Recommendations and effect on cervical cancer rates

Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

Lei J, Ploner A, Elfstrom KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;1340-1348.

Vaccination at ages 27 to 45, although approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, is recommended only in a shared decision-making capacity by ACIP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) due to the vaccine’s minimal effect on cancer prevention in this age group. The ACIP and ACOG do not recommend catch-up vaccination for adults aged 27 to 45 years, but they recognize that some who are not adequately vaccinated might be at risk for new HPV infection and thus may benefit from vaccination.4

In contrast, the American Cancer Society (ACS) does not endorse the 2019 ACIP recommendation for shared clinical decision making in 27- to 45-year-olds because of the low effectiveness and low cancer prevention potential of vaccination in this age group, the burden of decision making on patients and clinicians, and the lack of sufficient guidance on selecting individuals who might benefit.5

Decline in HPV infections

A study in the United States between 2003 and 2014 showed a 71% decline in vaccine-type HPV infections among girls and women aged 14 to 19 in the post–vaccine available era as compared with the prevaccine era, and a lesser but still reasonable decline among women in the 20- to 24-year-old age group.6 Overall, vaccine-type HPV infections decreased 89% for vaccinated girls and 34% for unvaccinated girls, demonstrating some herd immunity.6 Ideally, the vaccine is given before the onset of skin-to-skin genital sexual activity. Many studies have found the vaccine to be safe and that immunogenicity is maintained for at least 9 years.7-11

Decrease in invasive cervical cancer

Recently, Lei and colleagues published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that reviewed outcomes for more than 1.6 million girls and women vaccinated against HPV in Sweden between 2006 and 2017.12 Among girls who were vaccinated at younger than 17 years of age, there were only 2 cases of cancer, in contrast to 17 cases among those vaccinated at age 17 to 30 and 538 cases among those not vaccinated.

This is the first study to show definitively the preventive effect of HPV vaccination on the development of invasive cancer and the tremendous advantage of vaccinating at a young age. Nonetheless, the advantage conferred by catch-up vaccination (that is, vaccinating those at ages 17–30) also was significant.

Despite the well-established benefits of HPV vaccination, only 57% of women and 52% of men in the recommended age groups have received all recommended doses.13 Based on these findings, we need to advocate to our patients to vaccinate all children as early as recommended or possible and to continue catch-up vaccination for those in their 20s, even if they have hrHPV, given the efficacy of the current nonvalent vaccine against at least 7 oncogenic types. It is not at all clear that there is a benefit to vaccinating older women to prevent cancer, and we should currently focus on vaccinating younger people and continue to screen older women as newer research indicates that cervical cancer is increasing among women older than age 65.14

Continue to: Updated guidance on cervical cancer screening for average-risk women...

Updated guidance on cervical cancer screening for average-risk women

US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Frist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Fontham ET, Wolf AM, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

As more is understood about the natural history of HPV and its role in the development of cervical cancer and its precursors, refinements and updates have been made to our approaches for screening people at risk. There is much evidence and experience available on recommending Pap testing and HPV cotesting (testing for HPV along with cytology even if the cytology result is normal) among women aged 30 to 65 years, as that has been an option since the 2012 guidelines were published.15

We know also that HPV testing is more sensitive for detecting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) or greater at 5 years and that a negative HPV test is more reassuring than a negative Pap test.16

Primary HPV tests

HPV tests can be used in conjunction with cytology (that is, cotesting) or as a primary screening that if positive, can reflex either to cytology or to testing for the most oncogenic subtypes. Currently, only 2 FDA-approved primary screening tests are available, the cobas 4800 HPV test system (Roche Diagnostics) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company).17 Most laboratories in the United States do not yet have the technology for primary testing, and so instead they offer one of the remaining tests (Hybrid Capture 2 [Qiagen] and Cervista and Aptima [Hologic]), which do not necessarily have the same positive and negative predictive value as the tests specifically approved for primary testing. Thus, many clinicians and patients do not yet have access to primary HPV testing.

In addition, due to slow uptake of the HPV vaccine in many parts of the United States,13 there is concern that adding HPV testing in nonvaccinated women under age 30 would result in a surge of unnecessary colposcopy procedures for women with transient infections. Thus, several large expert organizations differ in opinion regarding screening among certain populations and by which test.

Screening guidance from national organizations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Cancer Society (ACS) differ in their recommendations for screening women in their 20s for cervical cancer.18,19 The USPSTF guidelines, which were published first, focus not only on the best test but also on what is feasible and likely to benefit public health, given our current testing capacity and vaccine coverage. The USPSTF recommends starting screening at age 21 with cytology and, if all results are normal, continuing every 3 years until age 30, at which point they recommend cytology every 3 years or cotesting every 5 years or primary HPV testing alone every 5 years (if all results are normal in each case).

In contrast, the ACS published "aspirational” guidelines, with the best evidence-based recommendations, but they acknowledge that due to availability of different testing options, some patients still need to be screened with existing modalities. The ACS recommends the onset of screening at age 25 with either primary HPV testing every 5 years (preferred) or cotesting every 5 years or cytology every 3 years.

Both the USPSTF and ACS guidelines state that if using cytology alone, the screening frequency should be every 3 years, and if using an HPV-based test, the screening interval (if all results are normal) can be extended to every 5 years.

Notably, the newest guidelines for cervical cancer screening essentially limit “screening” to low-risk women who are immunocompetent and who have never had an abnormal result, specifically high-grade dysplasia (that is, CIN 2 or CIN 3). Guidelines for higher-risk groups, including the immunosuppressed, and surveillance among women with prior abnormal results can be accessed (as can all the US guidelines) at the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) website (http://www.asccp.org/).

Continue to: New ASCCP management guidelines focus on individualized risk assessment...

New ASCCP management guidelines focus on individualized risk assessment

Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al; 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines Committee. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24:102-131.

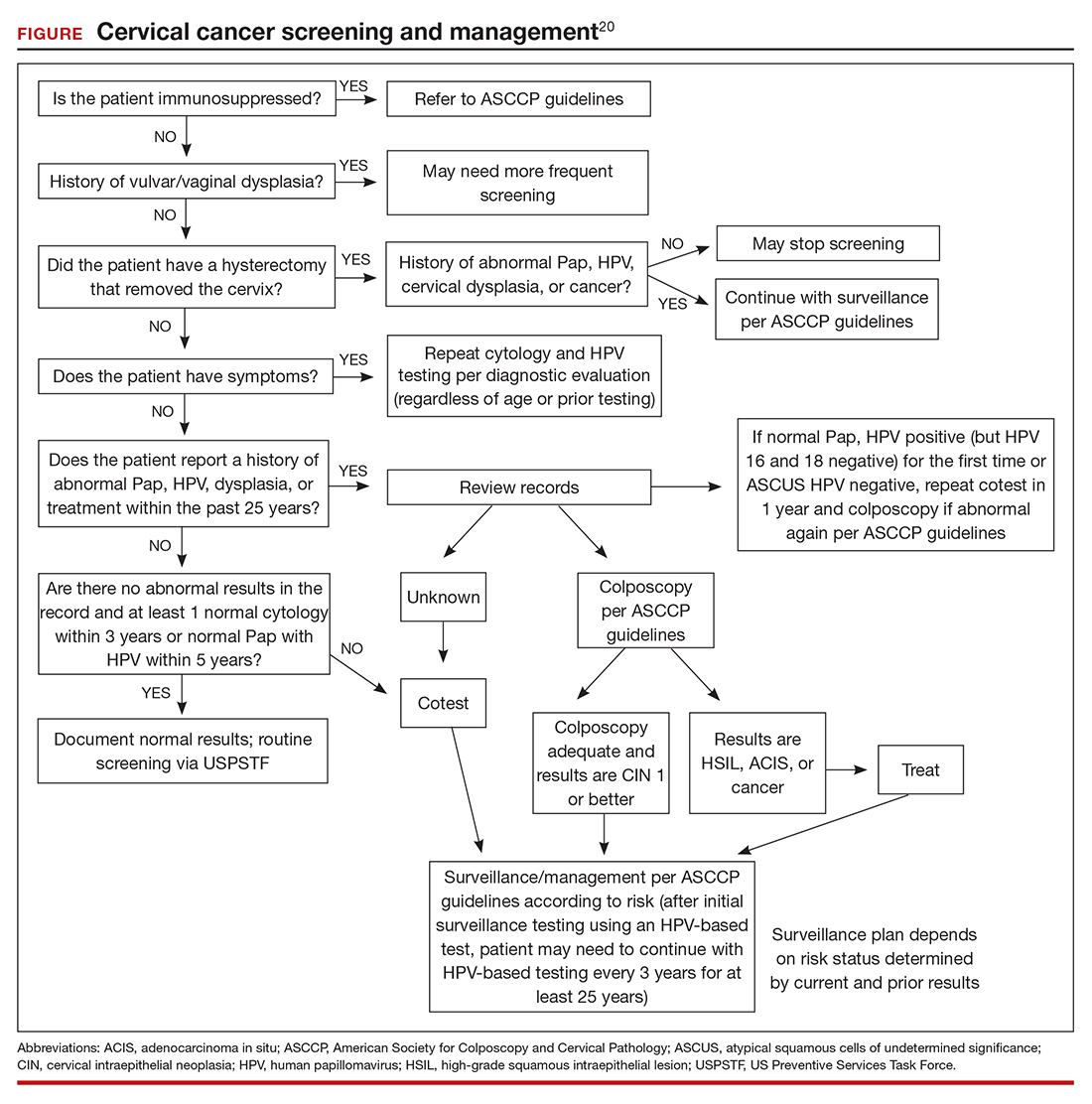

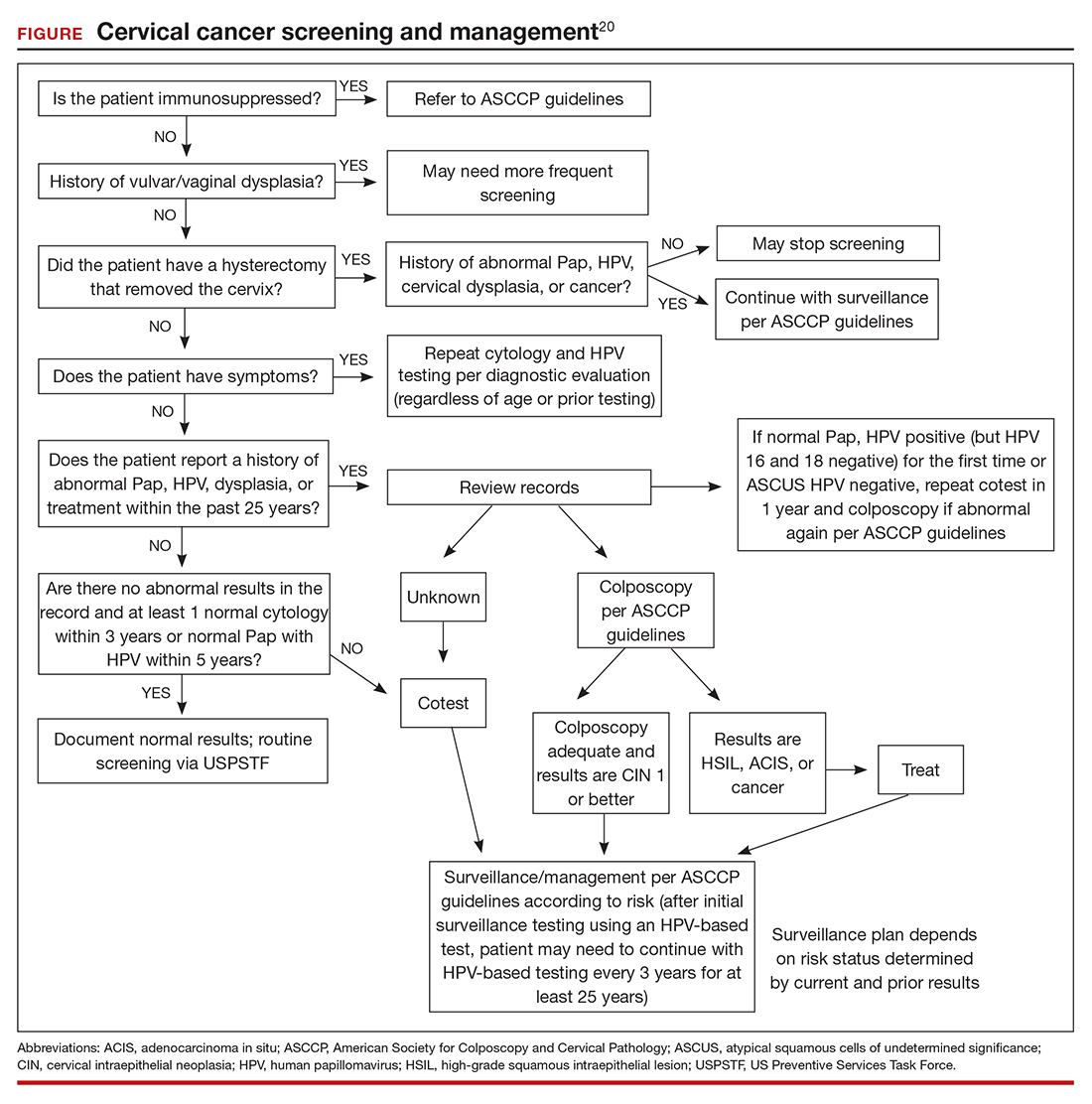

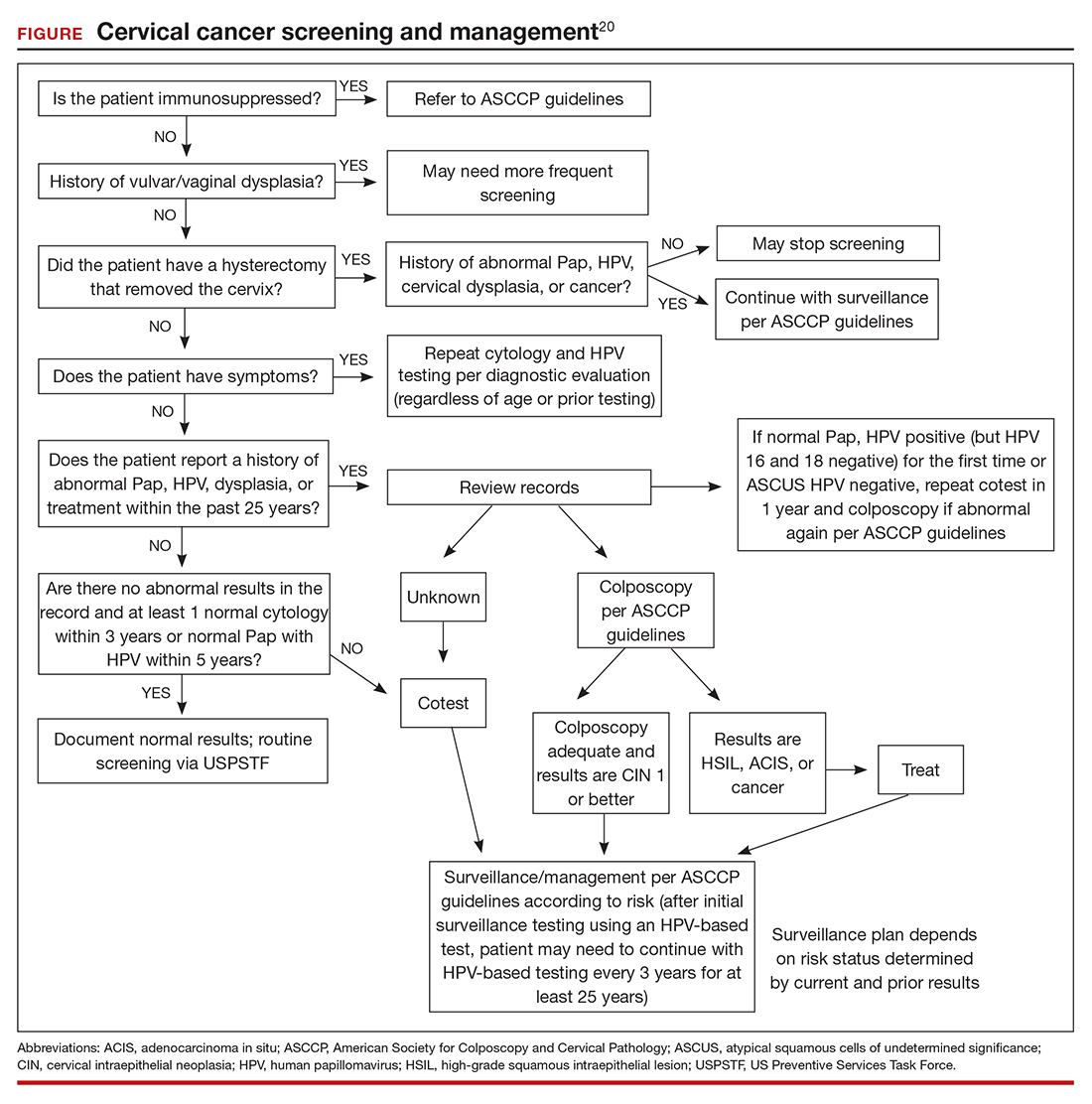

The ASCCP risk-based management guidelines introduce a paradigm shift from managing a specific cervical cancer screening result to using a clinical action threshold based on risk estimates that use both current and past test results to determine frequency and urgency of testing, management, and surveillance (FIGURE).20 The individualized risk estimate helps to target prevention for those at highest risk while minimizing overtesting and overtreatment.

Estimating risk and determining management

The new risk-based management consensus guidelines use risk and clinical action thresholds to determine the appropriate management course for cervical screening abnormalities.20 New data indicate that a patient’s risk of developing cervical precancer or cancer can be estimated using current screening results and previous screening test and biopsy results, while considering personal factors such as age and immunosuppression.20 For each combination of current test results and screening history (including unknown history), the immediate and 5-year risk of CIN 3+ is estimated.

With respect to risk, the following concepts underlie the changes from the 2012 guidelines:

- Negative HPV tests reduce risk.

- Colposcopy performed for low-grade abnormalities, which confirms the absence of CIN 2+, reduces risk.

- A history of HPV-positive results increases risk.

- Prior treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3 increases risk, and women with this history need to be followed closely for at least 25 years, regardless of age.

Once an individual’s risk is estimated, it is compared with 1 of the 6 proposed “clinical action thresholds”: treatment, optional treatment or colposcopy/biopsy, colposcopy/ biopsy, 1-year surveillance, 3-year surveillance, or 5-year return to regular screening (<0.15% 5-year CIN 3+ risk).

Key takeaways

Increasing knowledge of the natural history of HPV has led to improved approaches to prevention, including the nonvalent HPV vaccine, which protects against 7 high-risk and 2 low-risk HPV types; specific screening guidelines that take into consideration age, immune status, and prior abnormality; and risk-based management guidelines that use both current and prior results as well as age to recommend the best approach for managing an abnormal result and providing surveillance after an abnormal result. ●

Using the ASCCP risk thresholds, most patients with a history of an abnormal result, especially CIN 2+, likely will need more frequent surveillance testing for the foreseeable future. As increasing cohorts are vaccinated and as new biomarkers emerge that can help triage patients into more precise categories, the current risk categories likely will evolve. Hopefully, women at high risk will be appropriately managed, and those at low risk will avoid overtreatment.

- Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:1-17.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68;698-702.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1405-1408.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Human papillomavirus vaccination: ACOG committee opinion no. 809. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:e15-e21.

- Saslow D, Andrews KS, Manassaram-Baptiste D, et al; American Cancer Society Guideline Development Group. Human papillomavirus vaccination 2020 guideline update: American Cancer Society guideline adaptation. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:274-280.

- Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction— National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:594-603.

- Gee J, Weinbaum C, Sukumaran L, et al. Quadrivalent HPV vaccine safety review and safety monitoring plans for ninevalent HPV vaccine in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1406-1417.

- Cameron RL, Ahmed S, Pollock KG. Adverse event monitoring of the human papillomavirus vaccines in Scotland. Intern Med J. 2016;46:452-457.

- Chao C, Klein NP, Velicer CM, et al. Surveillance of autoimmune conditions following routine use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine. J Intern Med. 2012;271:193- 203.

- Suragh TA, Lewis P, Arana J, et al. Safety of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 2009–2017. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:2928-2932.

- Pinto LA, Dillner J, Beddows S, et al. Immunogenicity of HPV prophylactic vaccines: serology assays and their use in HPV vaccine evaluation and development. Vaccine. 2018;36(32 pt A):4792-4799.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfstrom KM et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1340- 1348.

- Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1109-1116.

- Feldman S, Cook E, Davis M, et al. Cervical cancer incidence among elderly women in Massachusetts compared with younger women. J Lower Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22: 314-317.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147-172.

- Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, et al. Benchmarking CIN 3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 suppl 1):S28-35.

- Salazar KL, Duhon DJ, Olsen R, et al. A review of the FDA-approved molecular testing platforms for human papillomavirus. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2019;8:284-292.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Fontham ET, Wolf AM, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al; 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines Committee. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24:102-131.

Infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) is an essential step in the development of cervical cancer and its precursors, as well as in several other cancers, including oropharyngeal, vulvar, vaginal, anal, and penile cancers. At least 13 HPV strains, known collectively as hrHPV, have been associated with cervical cancer, in addition to more than 150 low-risk HPV types that have not been associated with cancer (for example, HPV 6 and 11).1 Up to 80% of women (and most men, although men are not tested routinely) will become infected with at least one of the high-risk HPV types throughout their lives, although in most cases these infections will be transient and have no clinical impact for the patient. Patients who test positive consecutively over time for hrHPV, and especially those who test positive for one of the most virulent HPV types (HPV 16 or 18), have a higher risk of developing cervical cancer or precancer. In addition, many patients who acquire HPV at a young age may “clear” the infection, which usually means that the virus becomes inactive; however, often, for unknown reasons, the virus can be reactivated in some women later in life.

This knowledge of the natural history of HPV has led to improved approaches to cervical cancer prevention, which relies on a combined strategy that includes vaccinating as many children and young adults as possible against hrHPV, screening and triaging approaches that use HPV-based tests, and applying risk-based evaluation for abnormal screening results. New guidelines and information address the best approaches to each of these aspects of cervical cancer prevention, which we review here.

HPV vaccination: Recommendations and effect on cervical cancer rates

Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

Lei J, Ploner A, Elfstrom KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;1340-1348.

Vaccination at ages 27 to 45, although approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, is recommended only in a shared decision-making capacity by ACIP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) due to the vaccine’s minimal effect on cancer prevention in this age group. The ACIP and ACOG do not recommend catch-up vaccination for adults aged 27 to 45 years, but they recognize that some who are not adequately vaccinated might be at risk for new HPV infection and thus may benefit from vaccination.4

In contrast, the American Cancer Society (ACS) does not endorse the 2019 ACIP recommendation for shared clinical decision making in 27- to 45-year-olds because of the low effectiveness and low cancer prevention potential of vaccination in this age group, the burden of decision making on patients and clinicians, and the lack of sufficient guidance on selecting individuals who might benefit.5

Decline in HPV infections

A study in the United States between 2003 and 2014 showed a 71% decline in vaccine-type HPV infections among girls and women aged 14 to 19 in the post–vaccine available era as compared with the prevaccine era, and a lesser but still reasonable decline among women in the 20- to 24-year-old age group.6 Overall, vaccine-type HPV infections decreased 89% for vaccinated girls and 34% for unvaccinated girls, demonstrating some herd immunity.6 Ideally, the vaccine is given before the onset of skin-to-skin genital sexual activity. Many studies have found the vaccine to be safe and that immunogenicity is maintained for at least 9 years.7-11

Decrease in invasive cervical cancer

Recently, Lei and colleagues published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that reviewed outcomes for more than 1.6 million girls and women vaccinated against HPV in Sweden between 2006 and 2017.12 Among girls who were vaccinated at younger than 17 years of age, there were only 2 cases of cancer, in contrast to 17 cases among those vaccinated at age 17 to 30 and 538 cases among those not vaccinated.

This is the first study to show definitively the preventive effect of HPV vaccination on the development of invasive cancer and the tremendous advantage of vaccinating at a young age. Nonetheless, the advantage conferred by catch-up vaccination (that is, vaccinating those at ages 17–30) also was significant.

Despite the well-established benefits of HPV vaccination, only 57% of women and 52% of men in the recommended age groups have received all recommended doses.13 Based on these findings, we need to advocate to our patients to vaccinate all children as early as recommended or possible and to continue catch-up vaccination for those in their 20s, even if they have hrHPV, given the efficacy of the current nonvalent vaccine against at least 7 oncogenic types. It is not at all clear that there is a benefit to vaccinating older women to prevent cancer, and we should currently focus on vaccinating younger people and continue to screen older women as newer research indicates that cervical cancer is increasing among women older than age 65.14

Continue to: Updated guidance on cervical cancer screening for average-risk women...

Updated guidance on cervical cancer screening for average-risk women

US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Frist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Fontham ET, Wolf AM, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

As more is understood about the natural history of HPV and its role in the development of cervical cancer and its precursors, refinements and updates have been made to our approaches for screening people at risk. There is much evidence and experience available on recommending Pap testing and HPV cotesting (testing for HPV along with cytology even if the cytology result is normal) among women aged 30 to 65 years, as that has been an option since the 2012 guidelines were published.15

We know also that HPV testing is more sensitive for detecting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) or greater at 5 years and that a negative HPV test is more reassuring than a negative Pap test.16

Primary HPV tests

HPV tests can be used in conjunction with cytology (that is, cotesting) or as a primary screening that if positive, can reflex either to cytology or to testing for the most oncogenic subtypes. Currently, only 2 FDA-approved primary screening tests are available, the cobas 4800 HPV test system (Roche Diagnostics) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company).17 Most laboratories in the United States do not yet have the technology for primary testing, and so instead they offer one of the remaining tests (Hybrid Capture 2 [Qiagen] and Cervista and Aptima [Hologic]), which do not necessarily have the same positive and negative predictive value as the tests specifically approved for primary testing. Thus, many clinicians and patients do not yet have access to primary HPV testing.

In addition, due to slow uptake of the HPV vaccine in many parts of the United States,13 there is concern that adding HPV testing in nonvaccinated women under age 30 would result in a surge of unnecessary colposcopy procedures for women with transient infections. Thus, several large expert organizations differ in opinion regarding screening among certain populations and by which test.

Screening guidance from national organizations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Cancer Society (ACS) differ in their recommendations for screening women in their 20s for cervical cancer.18,19 The USPSTF guidelines, which were published first, focus not only on the best test but also on what is feasible and likely to benefit public health, given our current testing capacity and vaccine coverage. The USPSTF recommends starting screening at age 21 with cytology and, if all results are normal, continuing every 3 years until age 30, at which point they recommend cytology every 3 years or cotesting every 5 years or primary HPV testing alone every 5 years (if all results are normal in each case).

In contrast, the ACS published "aspirational” guidelines, with the best evidence-based recommendations, but they acknowledge that due to availability of different testing options, some patients still need to be screened with existing modalities. The ACS recommends the onset of screening at age 25 with either primary HPV testing every 5 years (preferred) or cotesting every 5 years or cytology every 3 years.

Both the USPSTF and ACS guidelines state that if using cytology alone, the screening frequency should be every 3 years, and if using an HPV-based test, the screening interval (if all results are normal) can be extended to every 5 years.

Notably, the newest guidelines for cervical cancer screening essentially limit “screening” to low-risk women who are immunocompetent and who have never had an abnormal result, specifically high-grade dysplasia (that is, CIN 2 or CIN 3). Guidelines for higher-risk groups, including the immunosuppressed, and surveillance among women with prior abnormal results can be accessed (as can all the US guidelines) at the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) website (http://www.asccp.org/).

Continue to: New ASCCP management guidelines focus on individualized risk assessment...

New ASCCP management guidelines focus on individualized risk assessment

Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al; 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines Committee. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24:102-131.

The ASCCP risk-based management guidelines introduce a paradigm shift from managing a specific cervical cancer screening result to using a clinical action threshold based on risk estimates that use both current and past test results to determine frequency and urgency of testing, management, and surveillance (FIGURE).20 The individualized risk estimate helps to target prevention for those at highest risk while minimizing overtesting and overtreatment.

Estimating risk and determining management

The new risk-based management consensus guidelines use risk and clinical action thresholds to determine the appropriate management course for cervical screening abnormalities.20 New data indicate that a patient’s risk of developing cervical precancer or cancer can be estimated using current screening results and previous screening test and biopsy results, while considering personal factors such as age and immunosuppression.20 For each combination of current test results and screening history (including unknown history), the immediate and 5-year risk of CIN 3+ is estimated.

With respect to risk, the following concepts underlie the changes from the 2012 guidelines:

- Negative HPV tests reduce risk.

- Colposcopy performed for low-grade abnormalities, which confirms the absence of CIN 2+, reduces risk.

- A history of HPV-positive results increases risk.

- Prior treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3 increases risk, and women with this history need to be followed closely for at least 25 years, regardless of age.

Once an individual’s risk is estimated, it is compared with 1 of the 6 proposed “clinical action thresholds”: treatment, optional treatment or colposcopy/biopsy, colposcopy/ biopsy, 1-year surveillance, 3-year surveillance, or 5-year return to regular screening (<0.15% 5-year CIN 3+ risk).

Key takeaways

Increasing knowledge of the natural history of HPV has led to improved approaches to prevention, including the nonvalent HPV vaccine, which protects against 7 high-risk and 2 low-risk HPV types; specific screening guidelines that take into consideration age, immune status, and prior abnormality; and risk-based management guidelines that use both current and prior results as well as age to recommend the best approach for managing an abnormal result and providing surveillance after an abnormal result. ●