User login

Glucose-lowering effects of incretin-based therapies

Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus: potential role of incretin-based therapies

Glucose-lowering effects of incretin-based therapies

Safety, tolerability, and nonglycemic effects of incretin-based therapies

- Glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP-4) inhibitors effectively lower blood glucose levels in a glucose-dependent manner, which results in a low incidence of hypoglycemia

- Reduction of glycosylated hemoglobin is greater with GLP-1 agonists (up to 1.5%) than with DPP-4 inhibitors (up to 0.9%), as is reduction of postprandial glucose (PPG)

- GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors vary in dosing (frequency, route of administration), contraindications, and requirement for dose adjustments with renal impairment

- GLP-1 agonists are emphasized in the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) 2009 guidelines and the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) 2009 consensus statement

The authors received editorial assistance from the Primary Care Education Consortium and WriteHealth, LLC in the development of this activity and honoraria from the Primary Care Education Consortium. They have disclosed that Dr Campbell is on the advisory board for Daiichi-Sankyo and the speakers bureau for Eli Lilly and Co; Dr Cobble is on the advisory board for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly and Co and speakers bureau for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca/Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novo Nordisk Inc; Dr Reid is on the advisory board and speakers bureau for Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk Inc, and sanofi-aventis; and Dr Shomali is on the advisory board for Novo Nordisk Inc and speakers bureau for Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Co, sanofi-aventis, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Introduction

The selection of glucose-lowering therapies is dependent on many factors, including stage of disease progression, comorbidities, and previous treatments, as highlighted in the 3 cases. Other factors include an agent’s efficacy in lowering blood glucose levels, side effects and tolerability, safety, convenience and ease of use, and cost, as well as a patient’s current glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) level. The mechanisms of action of concurrent glucose-lowering therapies also should be considered, since using therapies with complementary mechanisms is desirable.1 This article will focus on efficacy factors, while nonglycemic factors, including safety and tolerability, will be discussed in the next article in this supplement (“Safety, tolerability, and nonglycemic effects of incretin-based therapies”). Among these many factors, 2 concerning efficacy deserve discussion at this point.

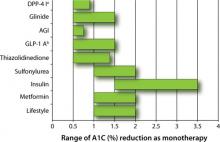

First, the magnitude to which a pharmacologic option typically lowers blood glucose varies from 0.5% to 3.5% as either monotherapy or combination therapy (FIGURE 1).1-3 According to the AACE/ACE 2009 recommendations, monotherapy is appropriate if the initial A1C level is 6.5% to 7.5%, while dual therapy is appropriate if the A1C level is 7.6% to 9.0%. If the A1C level is >9.0%, however, combination (dual or triple) therapy is required.4,5 In contrast, the ADA/EASD 2009 consensus statement provides more general options. These treatment recommendations are based on landmark trials that show the risk of microvascular and, perhaps, macrovascular complications are decreased substantially.

The second factor to consider is the effectiveness of each agent in lowering both fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and PPG. As demonstrated by Monnier et al, at an A1C level of approximately 8% to 8.5%, FPG and PPG contribute equally to the A1C level.6 At A1C >8.5%, the contribution of FPG increases and PPG decreases. Conversely, at A1C <8%, the contribution of PPG increases and FPG decreases. Thus, the increasing predominance of PPG as patients gain better glycemic control suggests that an agent that effectively lowers both FPG and PPG is needed to achieve the target glycemic goal of ≤7%.

The correlation between PPG and cardiovascular risk is also worth mentioning here. A number of studies have linked elevated PPG levels to increased cardiovascular risk,7-10 and 2 studies have shown PPG to be more predictive than FPG for cardiovascular risk.11,12 One recent study, NAVIGATOR, sought to explore this connection further but could not provide definitive results.13,14 While the study found that 5 years of nateglinide provided no protection against progression of cardiovascular disease in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and cardiovascular disease (or risk factors), it also revealed a paradoxical increase in PPG levels in patients taking the drug. Research on this issue will no doubt continue. The agents that provide the greatest reduction in PPG are insulin, GLP-1 agonists, and pramlintide.4 Of course, benefits of glycemic control must be weighed against potential adverse effects of each agent, as will be discussed in the next article.

FIGURE 1 Range of A1C lowering by class of glucose-lowering agent as monotherapy or by lifestyle modification1-3

AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; DPP-4 I, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; GLP-1 A, glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist.

a Adapted to include sitagliptin and saxagliptin.

b Adapted to include exenatide and liraglutide.

Selecting initial therapy

Metformin, in combination with lifestyle intervention, has become the recommended first-line pharmacologic agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), unless there is a contraindication, such as renal disease, hepatic disease, heart failure, gastrointestinal intolerance, or risk of lactic acidosis. This is because of its efficacy, safety, absence of weight gain, and relatively low cost.1,4 But how should therapy be modified if metformin is no longer effective in maintaining glycemic control or if it is contraindicated? Let’s return to our 3 cases and focus on the glycemic effects of the glucose-lowering agents. (The next article focuses on nonglycemic effects.) As a reminder, in these cases we address dual oral therapy failure, intolerance to metformin monotherapy, and metformin failure.

Modifying therapy

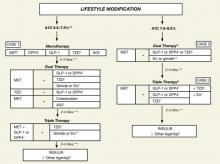

As we focus our attention on the GLP-1 agonists (exenatide, liraglutide) and DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, saxagliptin), we will keep in mind the current indications and limitations of use, as approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (TABLE 1).15-19 We also need to keep in mind the increasing role of the GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in the treatment of patients with T2DM, as reflected in the ADA/EASD 2009 consensus guidelines1 and especially the 2009 consensus statement by the AACE/ACE (FIGURE 2).4 Finally, as described in the 2010 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes by the ADA, in reflection of recent clinical trials such as ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VADT, the target glycemic goal must be carefully determined based on many factors, including patient comorbidity, duration of T2DM, life expectancy, and history of hypoglycemia.20

TABLE 1

Approved indications and limitations of the GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors15-19

| Class/agents | Indications and usage | Limitations of use |

|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 agonists | ||

| Exenatide | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied in combination with insulin. Has not been studied sufficiently in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Use with caution. Do not use if CrCl <30 mL/min or in ESRD. Use with caution in patients with renal transplantation. |

| Liraglutide | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied in combination with insulin. Has not been studied sufficiently in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Use with caution. Not recommended as first-line therapy for patients inadequately controlled with diet and exercise. No dosing adjustment; use with caution in patients with renal disease. |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | ||

| Sitagliptin | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied sufficiently in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Use with caution. Dose is reduced to 50 mg OD when CrCl ≥30 to <50 mL/min and to 25 mg OD when CrCL <30 mL/min or in ESRD requiring dialysis. |

| Saxagliptin | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied in combination with insulin. Dose is reduced to 2.5 mg OD when CrCl ≤50 mL/min or in ESRD requiring dialysis. |

| DPP, dipeptidyl peptidase; ESRD, end stage renal disease; GLP, glucagon-like peptide; OD, once daily; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. | ||

FIGURE 2 An algorithm for glycemic control by the AACE/ACE*4,5

A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; MET, metformin; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

*To achieve A1C goal ≤6.5%, which may not be appropriate for all patients.

**For patients with diabetes and A1C <6.5%, pharmacologic Rx may be considered.

***If A1C goal not achieved safely.

†Preferred initial agent.

1DPP-4 if ↑PPG and ↑FPG or GLP-1 if ↑↑PPG.

2TZD if metabolic syndrome and/or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

3AGI if ↑PPG.

4Glinide if ↑PPG or SU if ↑FPG.

5Low-dose secretagogue recommended.

6a) Discontinue insulin secretagogue with multidose insulin; b) Can use pramlintide with prandial insulin.

7Decrease secretagogue by 50% when added to GLP-1 or DPP-4.

8If A1C <8.5%, combination Rx with agents that cause hypoglycemia should be used with caution.

9If A1C >8.5%, in patients on dual therapy, insulin should be considered.

Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, et al. Statement by an American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: an algorithm for glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:540-559. [Published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2009;15:768-770]. Reprinted with permission from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Case 1

This 53-year-old man was recently diagnosed with T2DM, with a baseline A1C of 7.5%. He is intolerant of metformin and wants to be treated with an alternative medication. In the case of metformin intolerance or a contraindication to metformin, a thiazolidinedione, DPP-4 inhibitor, GLP-1 agonist, or α-glucosidase inhibitor is recommended by the AACE/ACE if the patient’s A1C level is 6.5% to 7.5% (FIGURE 2).4,5 The safety and tolerability associated with each treatment option, such as hypoglycemia and weight gain, should be discussed with the patient.

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors as monotherapy

Use of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors as monotherapy in combination with lifestyle intervention has been investigated in several clinical trials.2,3,21-25 Generally, as monotherapy, DPP-4 inhibitors have been shown to reduce A1C by 0.5% to 0.9% and GLP-1 agonists by 0.5% to 1.5%.1-3 Increasing the dose provides additional modest glucose reduction. For our patient in Case 1, therefore, either of the DPP-4 inhibitors, sitagliptin or saxagliptin, would be expected to reduce his A1C from his current level of 7.5% to the target level of <7.0%. The GLP-1 agonists, exenatide or liraglutide, would also be expected to reduce his A1C to the target level.

Results of clinical trials have shown that monotherapy with a DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist reduces FPG levels by 11 to 22 mg/dL and 11 to 61 mg/dL, respectively. Reductions in PPG levels range from 24 to 35 mg/dL for the DPP-4 inhibitors and 21 to 48 mg/dL for the GLP-1 agonists. The substantial reduction in PPG is especially important as the A1C level drops to <8.0%6 and approaches the target level of <7.0%, as is the case with this patient.

The greater reductions in FPG and PPG observed with GLP-1 agonists compared with DPP-4 inhibitors likely stem from the pharmacologic level of GLP-1 activity achieved with the GLP-1 agonists and their direct action on the GLP-1 receptor,26-28 which is in contrast to the indirect action of the DPP-4 inhibitors and the resulting lower physiologic levels of endogenous GLP-1.29

The glucose-lowering ability of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists appears to be affected by the baseline A1C level and history of previous treatment. A monotherapy trial with sitagliptin showed that patients with a baseline A1C level ≥9.0% experienced a reduction in A1C of 1.5% compared with 0.6% for those with a baseline A1C level <8.0%.30 For the patient in Case 1, the reduction of 0.6% would be sufficient to lower his A1C to <7.0%.

Similarly, limited data suggest that patients previously treated with glucose-lowering therapy achieve a smaller reduction in A1C compared with those managed with diet and exercise alone. In a study by Garber et al,2 patients previously managed with diet and exercise alone achieved a reduction in A1C of 1.2% and 1.6% with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg once daily, respectively, vs 0.5% and 0.7% for those previously treated with glucose-lowering monotherapy.

In summary, data from clinical trials support the efficacy of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists as monotherapy in combination with lifestyle intervention. In the case of this 53-year-old man with an A1C level of 7.5%, either of the 2 DPP-4 inhibitors or the 2 GLP-1 agonists would provide sufficient glucose-lowering to achieve the target A1C level of <7.0%. Furthermore, although a greater reduction has been observed with GLP-1 agonists (0.5% to 1.5%), the DPP-4 inhibitors also should provide for significant reduction (0.5% to 0.9%) of this patient’s PPG level.

We now turn our attention to the glycemic effects of the GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with 1 or more pharmacologic agents.

Case 2

This 47-year-old man was diagnosed with T2DM 2.5 years ago. The addition of pioglitazone to the combination of lifestyle intervention and metformin has resulted in significant edema and weight gain. He refuses to take a diuretic because of previous experience and wants to discontinue his pioglitazone. He currently has an A1C of 7.0%. What should replace pioglitazone for this patient, who is no longer achieving glycemic control with lifestyle intervention and metformin?

For a patient with an A1C level of 7.6% to 9.0%, the AACE/ACE 2009 guidelines suggest adding a GLP-1 agonist, DPP-4 inhibitor, or thiazolidinedione (FIGURE 2).4,5 Among these 3 options, GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors are preferred due to both their efficacy data when combined with metformin and their overall safety profiles. The GLP-1 agonists are preferred over the DPP-4 inhibitors due to better reduction of PPG levels and potential for substantial weight loss. Thiazolidinediones would be the third choice because of their risks of weight gain, edema, congestive heart failure, and fractures.4

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with metformin

Many clinical trials have been conducted with GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with lifestyle intervention and metformin (TABLE 2).31-36 These trials generally show similar trends in A1C reduction as with monotherapy, although a somewhat greater reduction has been seen with GLP-1 agonists compared with DPP-4 inhibitors. Increasing the dose may provide additional modest glucose reduction. As is typical with monotherapy, patients with a higher baseline A1C level (ie, ≥9.0%) achieve greater A1C reduction. The same holds true for reductions in FPG and PPG levels. For the patient in Case 2, who had an A1C level of 7.8% prior to addition of pioglitazone, discontinuation of pioglitazone and addition of either exenatide or liraglutide to lifestyle intervention and metformin would be expected to lower his A1C level to the target of <7.0%. Although possible, it is unlikely that addition of sitagliptin or saxagliptin would achieve the target A1C level.

TABLE 2

Selected clinical trials of incretin-based therapies as add-on therapy to metformin31-36

| Agent/clinical trial | Duration (wk) | A1C (%) | % Patients achieving A1C < 7% | FPG (mg/dL) | PPG (mg/dL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | |||

| Exenatide (E) | ||||||||

| DeFronzo, 200531 | 30 | |||||||

| E, 5 μg BID | 8.3 | –0.4 | 32 | 176 | –7 | NR | NR | |

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.2 | –0.8 | 46 | 168 | –10 | NR | NR | |

| Placebo | 8.2 | +0.1 | 13 | 170 | +14 | NR | NR | |

| Barnett, 200732 | 32 | |||||||

| E, 5 μg BID x 4 wk, then 10 μg BID | 9.0 | -1.4 | 38 | NR | –52 | NR | NR | |

| Glargine | 9.0 | -1.4 | 40 | NR | –74 | NR | NR | |

| Liraglutide (L) | ||||||||

| Nauck, 200933 | 26 | |||||||

| L, 0.6 mg OD | 8.4 | –0.7 | 28 | 184 | –20 | NR | –31 | |

| L, 1.2 mg OD | 8.3 | –1.0 | 35 | 178 | –29 | NR | –41 | |

| L, 1.8 mg OD | 8.4 | –1.0 | 42 | 182 | –31 | NR | –47 | |

| Glim, 4 mg OD | 8.4 | –1.0 | 36 | 180 | –23 | NR | –45 | |

| Placebo | 8.4 | +0.1 | 11 | 180 | +7 | NR | +11 | |

| Sitagliptin (Si) | ||||||||

| Charbonnel, 200634 | 24 | |||||||

| Si, 100 mg OD | 8.0 | –0.7 | 47 | 169 | –16 | NR | NR | |

| Placebo | 8.0 | 0 | 18 | 173 | +9 | NR | NR | |

| Raz, 200835 | 18a/30 | |||||||

| Si, 100 mg OD | 9.3 | –1.0 | 22 | 202 | –29 | NR | –68a | |

| Placebo | 9.1 | 0 | 3 | 198 | –4 | NR | –14a | |

| Saxagliptin (Sa) | ||||||||

| DeFronzo, 200936 | 24 | |||||||

| Sa, 2.5 mg OD | 8.1 | –0.6 | 37 | 174 | –14 | NR | –62 | |

| Sa, 5 mg OD | 8.1 | –0.7 | 44 | 180 | –22 | NR | –58 | |

| Sa, 10 mg OD | 8.0 | –0.6 | 44 | 176 | –21 | NR | –50 | |

| Placebo | 8.1 | +0.1 | 17 | 174 | +1 | NR | –18 | |

| A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; BID, twice daily; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; Glim, glimepiride; NR, not reported; OD, once daily; PPG, postprandial glucose. aMeasured at 18 weeks. | ||||||||

Choosing among incretin-based therapies

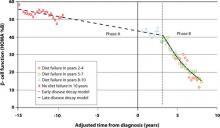

The choice of 1 GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor over another can be difficult, but recent data from 3 clinical trials provide some guidance in terms of efficacy and safety. Each of these trials has been a direct comparison of add-on therapy with 2 incretin-based therapies. The first, by Buse et al, was an open-label comparison of exenatide 10 μg twice daily with liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily for 26 weeks.37 Patients with inadequately controlled T2DM on maximally tolerated doses of metformin, sulfonylurea, or both participated in the study (N=464). The mean change in A1C level from baseline to Week 26 was significantly greater with liraglutide than with exenatide (+1.1% vs +0.8%, respectively; P<.0001) (FIGURE 3A).37 The difference between the 2 groups was greatest for patients with a baseline A1C ≥10% (liraglutide, –2.4%; exenatide, –1.2%). Furthermore, more patients in the liraglutide group than in the exenatide group achieved an A1C level <7% (54% vs 43%; P=.0015). This may have been a result of a significantly greater reduction in FPG with liraglutide than with exenatide (29 vs 11 mg/dL; P<.0001). The reduction in PPG after breakfast and after dinner (but not after lunch) from baseline to Week 26, however, was significantly greater with exenatide than with liraglutide (FIGURE 3B).37 Liraglutide increased mean fasting insulin secretion (+12.4 pmol/L), whereas there was a small reduction with exenatide (–1.4 pmol/L; P=.0355). Fasting glucagon secretion was reduced in both the liraglutide and exenatide groups, but the difference was not significant (–19.4 vs –12.3 ng/L; P=.1436). A 14-week extension of this study showed that patients who were switched from exenatide to liraglutide experienced a significant further reduction in A1C (–0.3%), FPG (–16 mg/dL), and body weight (–0.9 kg) (P<.0001 for all mean values).38 In those who continued liraglutide, A1C (–0.1%) and FPG (–4 mg/dL) levels remained relatively stable, while body weight was further reduced (–0.4 kg) (P<.009).

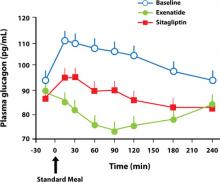

The second study was a crossover trial by DeFronzo et al that compared exenatide with sitagliptin in patients inadequately controlled with metformin (N=95).39 In addition to maintaining a stable dose of metformin, patients received either exenatide 5 μg twice daily for 1 week followed by 10 μg twice daily for 1 week, or sitagliptin 100 mg every morning for 2 weeks. Patients were then crossed over to the other treatment. While the mean change from baseline FPG (178 mg/dL) was similar in the exenatide and sitagliptin groups (–15 vs –19 mg/dL; P=.3234), the change from baseline 2-hour PPG (245 mg/dL) was –112 mg/dL for exenatide vs –37 mg/dL for sitagliptin (P<.0001). Following crossover, the patients who were switched from exenatide to sitagliptin experienced an increase in PPG of approximately 73 mg/dL (from 133 to 205 mg/dL), whereas those switched from sitagliptin to exenatide experienced a further reduction of –76 mg/dL (from 209 to 133 mg/dL). Consistent with these observations, exenatide was more effective than sitagliptin in augmenting postprandial insulin secretion and suppressing postprandial glucagon secretion. Exenatide, but not sitagliptin, significantly slowed gastric emptying (P<.0001).

In the third trial, Pratley et al compared the addition of liraglutide 1.2 mg or 1.8 mg and sitagliptin 100 mg once daily in patients inadequately controlled with metformin 1500 mg daily or more (N=665).40 From a mean A1C level of 8.5% at baseline, reductions in A1C after 26 weeks were 1.2% for liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.5% for liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 0.9% for sitagliptin (P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses). Mean reductions in FPG were 34 mg/dL for liraglutide 1.2 mg and 39 mg/dL for liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 15 mg/dL for sitagliptin. Weight decreased in all 3 groups but by significantly more with liraglutide: 2.9 kg with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 3.4 kg with liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 1.0 kg with sitagliptin (P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses). Both liraglutide doses resulted in significant improvements from baseline in homeostasis model assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-B): 27.23% with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 28.70% with liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 4.18% with sitagliptin (P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses), whereas no treatment differences were observed for HOMA–insulin resistance or fasting insulin concentration.

The results of these trials indicate that for this 47-year-old man, a GLP-1 agonist would be a better choice to replace pioglitazone, primarily because the A1C reduction of ≥1.0% that can be achieved with this class of drug, and which is needed in this case, is greater than the reduction that can be expected with a DPP-4 inhibitor. Other issues such as weight loss and low individual incidence of hypoglycemia, which also need to be considered, are discussed in the next article.

FIGURE 3 Comparison of glucose-lowering effects of liraglutide and exenatide37

A, Change in glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) level from baseline to Week 26 with liraglutide 1.8 mg once a day or exenatide 10 μg twice a day.

B, Efficacy of treatment with liraglutide 1.8 mg once a day vs exenatide 10 μg twice a day: 7-point self-measured plasma glucose profiles from baseline to Week 26.

Reprinted with permission from: Lancet. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). 2009;374:39-47. Copyright Elsevier, 2009.

Case 3

This 68-year-old woman was diagnosed with T2DM 5 years ago. She has experienced disease progression with a rising A1C level despite dual oral therapy. Her current A1C is 7.4%. She also has peripheral arterial disease and osteoporosis, both of which are being treated. For a patient who has failed dual oral therapy with metformin and another agent, the AACE/ACE guidelines suggest the addition of a DPP-4 inhibitor, GLP-1 agonist, or thiazolidinedione (FIGURE 2).4,5 If a DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist is added, the dose of the sulfonylurea should be decreased by 50% due to the increased risk of hypoglycemia.5 Her mild renal insufficiency is also a consideration.

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with metformin and other oral agents

Many clinical trials have been conducted with a GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor in combination with lifestyle intervention, metformin, and 1 or 2 other agents. As shown in TABLE 3,41-48 the reductions in A1C observed when a GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor is added to dual therapy are generally similar to those observed with GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor monotherapy, although reductions of up to 1.5% have been observed with the addition of liraglutide.46,47 Similarly, reductions in FPG with combination therapy—7 to 74 mg/dL with GLP-1 agonists and 14 to 29 mg/dL with DPP-4 inhibitors—have been comparable to those observed with monotherapy. These results provide evidence of the effectiveness of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in further lowering blood glucose levels when added to dual therapy in patients with advanced disease.

TABLE 3

Selected clinical trials of incretin-based therapies added to combination therapy41-48

| Agent/clinical trial | Combination/duration (wk) | A1C (%) | % Patients achieving A1C <7% | FPG (mg/dL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | |||

| Exenatide (E) | ||||||

| Kendall, 200541 | Met + SU/30 | |||||

| E, 5 μg BID | 8.5 | -0.6 | 27 | 182 | -9 | |

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.5 | -0.6 | 34 | 178 | -11 | |

| Placebo | 8.5 | +0.2 | 9 | 180 | +14 | |

| Blonde, 200642 | Met + SU/52 | |||||

| E, 5 μg BID | 8.3 | -1.1 | 48 | 173 | -16 | |

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.3 | -1.1 | 48 | 173 | -16 | |

| Nauck, 200743 | Met + SU/52 | |||||

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.6 | -1.0 | 32 | 198 | -32 | |

| Aspart 70/30 BID | 8.6 | -0.9 | 24 | 203 | -31 | |

| Heine, 200544 | Met + SU/26 | |||||

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.2 | -1.1 | 46 | 182 | -26 | |

| Glargine OD | 8.3 | -1.1 | 48 | 187 | -52 | |

| Zinman, 200745 | TZD±Met/16 | |||||

| E, 10 μg BID | 7.9 | -0.9 | 62 | 164 | -29 | |

| Placebo | 7.9 | +0.1 | 16 | 159 | +2 | |

| Liraglutide (L) | ||||||

| Russell-Jones, 200946 | Met + Glim/26 | |||||

| L, 1.8 mg OD | 8.3 | -1.3 | NR | 164 | -28 | |

| Glargine | 8.2 | -1.1 | NR | 164 | -32 | |

| Placebo | 8.3 | -0.2 | NR | 169 | +10 | |

| Zinman, 200947 | Met + Rosi/26 | |||||

| L, 1.2 mg OD | 8.5 | -1.5 | 58 | 182 | -43 | |

| L, 1.8 mg OD | 8.6 | -1.5 | 54 | 185 | -48 | |

| Placebo | 8.4 | -0.5 | 28 | 180 | -9 | |

| Sitagliptin (Si) | ||||||

| Hermansen, 200748 | Glim±Met/24 | |||||

| Si, 100 mg OD | 8.3 | -0.5 | 17 | 181 | -4 | |

| Placebo | 8.3 | +0.3 | 5 | 182 | +16 | |

| A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; BID, twice daily; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; Glim, glimepiride; Met, metformin; NR, not reported; OD, once daily; Rosi, rosiglitazone; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione. | ||||||

GLP-1 agonist and DPP-4 inhibitor trials compared with insulin

While sitagliptin is the only one of the 4 incretin-based therapies approved for use in combination with insulin (TABLE 1),15-19 several studies have compared the efficacy of adding exenatide, liraglutide, or sitagliptin with adding insulin glargine to other glucose-lowering therapy.32,43,44,46 These trials have generally shown a GLP-1 agonist to provide glucose-lowering ability comparable to that with insulin glargine. For example, separate 26-week trials compared exenatide and liraglutide with insulin glargine in patients suboptimally controlled with metformin and a sulfonylurea. In the first (N=551), both exenatide and insulin glargine decreased the mean A1C level 1.1%.44 The FPG level decreased 26 mg/dL in the exenatide group and 52 mg/dL in the insulin glargine group (P<.001). On the other hand, exenatide reduced PPG excursions compared with insulin glargine. In the second trial (N=576), the A1C level decreased 1.3% in the liraglutide group vs 1.1% in the insulin glargine group (P=.0015) and 0.2% in the placebo group (both, P<.0001 vs placebo).46 The FPG level decreased 28 and 32 mg/dL, respectively, in the liraglutide and insulin glargine groups and increased 10 mg/dL in the placebo group. Postprandial glucose decreased 33 and 29 mg/dL, respectively, in the liraglutide and glargine groups but did not change in the placebo group (P<.0001 liraglutide vs placebo). These trials showed that addition of exenatide or liraglutide to metformin and a sulfonylurea provides comparable glucose reduction to addition of insulin glargine.

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with agents other than metformin

While metformin is the cornerstone of glucose-lowering therapy, GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors have been investigated as dual therapy in combination with agents other than metformin.49-52

The addition of liraglutide 0.6 mg, 1.2 mg, or 1.8 mg; rosiglitazone 4 mg; or placebo to glimepiride 2 mg to 4 mg was compared in patients with inadequately controlled blood glucose on monotherapy or combination therapy, excluding insulin (N=1041).49 After 26 weeks, the mean A1C level decreased 1.1% with either liraglutide 1.2 mg or 1.8 mg once daily and 0.4% with rosiglitazone 4 mg daily but increased 0.2% with placebo (all, P<.0001). Similarly, the decrease in FPG was significantly greater with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg compared with placebo (treatment difference, 47 mg/dL; P<.0001) and rosiglitazone 4 mg (treatment difference, 13 mg/dL; P<.006). Reductions in PPG were also significantly greater with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg (45 and 49 mg/dL, respectively) than with rosiglitazone 4 mg (32 mg/dL; P≤.043 vs liraglutide 1.2 mg; P=.0022 vs liraglutide 1.8 mg) and placebo (7 mg/dL; P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses).

Two trials have investigated treatment with a DPP-4 inhibitor in combination with a thiazolidinedione. In 1 trial, patients (N=353) were randomized to receive sitagliptin 100 mg once daily or placebo in combination with pioglitazone 30 mg to 45 mg daily.50 After 24 weeks, the mean A1C level decreased 0.9% with the addition of sitagliptin and 0.2% with placebo (P<.001). The FPG level decreased 17 mg/dL in the sitagliptin group and increased 1 mg/dL in the placebo group (P<.001). Similar changes in A1C and FPG levels were observed in another trial involving the addition of saxagliptin 2.5 mg or 5 mg once daily to pioglitazone 30 mg to 45 mg or rosiglitazone 4 mg to 8 mg once daily.51 Reduction in the PPG area under the curve was greater with either dose of saxagliptin than with placebo.

The addition of saxagliptin to a submaximal dose of glyburide was compared with uptitration of glyburide in 768 patients with T2DM.52 Patients were randomized to receive saxagliptin 2.5 mg or 5 mg once daily in combination with glyburide 7.5 mg once daily, or glyburide 10 mg to 15 mg once daily for 24 weeks. The mean A1C level decreased 0.5% and 0.6% in the saxagliptin 2.5 mg and 5 mg groups, respectively, and increased 0.1% in the glyburide uptitration group (P<.0001 vs both saxagliptin groups). The FPG level decreased 7 and 10 mg/dL in the saxagliptin 2.5 mg and 5 mg groups, respectively, and increased 1 mg/dL in the glyburide uptitration group (P=.0218 and P=.002, respectively). Similar changes were observed in PPG (P<.0001).

These trials demonstrate that the efficacy of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors extend to combined use with agents other than metformin.

Summary

Extensive experience from randomized clinical trials demonstrates the efficacy of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors as monotherapy and in combination with metformin and other agents, although reductions in FPG and PPG, and consequently A1C, are greater with GLP-1 agonists than with DPP-4 inhibitors. This difference may result from the pharmacologic levels of GLP-1 activity that are achieved with the GLP-1 agonists and their direct action on the GLP-1 receptor. The GLP-1 agonists have attributes that would make either of them an appropriate choice in the management of all 3 patients in our case studies, while either DPP-4 inhibitor would be an appropriate choice for Case 1. Differences in dosing, administration, safety, and tolerability should be considered.

1. Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:193-203.

2. Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373:473-481.

3. Rosenstock J, Sankoh S, List JF. Glucose-lowering activity of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor saxagliptin in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:376-386.

4. Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, et al. Statement by an American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: an algorithm for glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:540-559.

5. Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology. AACE/ACE diabetes algorithm for glycemic control (update). http://www.aace.com/pub/pdf/GlycemicControlAlgorithmPPT.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed May 17, 2010.

6. Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c). Diabetes Care. 2003;26:881-885.

7. Fuller JH, Shipley MJ, Rose G, et al. Coronary-heart-disease risk and impaired glucose tolerance. The Whitehall Study. Lancet. 1980;1:1373-1376.

8. Beks PJ, Mackaay AJC, de Neeling JND, et al. Peripheral arterial disease in relation to glycaemic level in an elderly caucasian population. The Hoorn Study. Diabetologia. 1995;38:86-96.

9. Fontbonne AM, Eschwège EM. Insulin and cardiovascular disease. Paris Prospective Study. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:461-469.

10. Donahue RP, Abbott RD, Reed DM, et al. Postchallenge glucose concentration and coronary heart disease in men of Japanese ancestry. Honolulu Heart Program. Diabetes. 1987;36:689-692.

11. DECODE Study Group. European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and ADA diagnostic criteria. Diabetes epidemiology: collaborative analysis of diagnostic criteria in Europe. Lancet. 1999;354:617-621.

12. Hanefeld M, Fischer S, Julius U, et al. for the DIS Group. Risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in newly detected NIDDM: the Diabetes Intervention Study, 11-year follow-up. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1577-1583.

13. McMurray JJ, Holman RR, Haffner SJ, et al. and the NAVIGATOR Study Group. Effect of nateglinide on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. New Engl J Med. 2010;362:1463-1476.

14. Nathan DM. Navigating the choices for diabetes prevention. New Engl J Med. 2010;362:1533-1535.

15. Byetta [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

16. Victoza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc; 2010.

17. Januvia [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; February 26, 2010.

18. Onglyza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2009.

19. Januvia Supplement approval. US Food and Drug Administration. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2010/021995s010s011s012s014ltr.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed June 7, 2010.

20. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2010 Diabetes Care. 2010;33(suppl 1):S11-S61.

21. Nelson P, Poon T, Guan X, et al. The incretin mimetic exenatide as a monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9:317-326.

22. Moretto TJ, Milton DR, Ridge TD, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of exenatide monotherapy over 24 weeks in antidiabetic drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1448-1460.

23. Vilsboll T, Zdravkovic M, Le Thi T, et al. Liraglutide, a long-acting human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, given as monotherapy significantly improves glycemic control and lowers body weight without risk of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1608-1610.

24. Scott R, Wu M, Sanchez M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy over 12 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:171-180.

25. Hanefeld M, Herman GA, Wu M, et al. Once-daily sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:1329-1339.

26. Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Madsbad S, et al. Defective amplification of the late phase insulin response to glucose by GIP in obese type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1111-1119.

27. Nauck MA, Heimesaat MM, Orskov C, et al. Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 [7-36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory poly-peptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:301-307.

28. Zander M, Madsbad S, Madsen JL, et al. Effect of 6-week course of glucagon-like peptide 1 on glycaemic control, insulin sensitivity, and beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes: a parallel-group study. Lancet. 2002;359:824-830.

29. Deacon CF, Hughes TE, Holst JJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition potentiates the insulinotropic effect of glucagon-like peptide 1 in the anesthetized pig. Diabetes. 1998;47:764-769.

30. Aschner P, Kipnes MS, Lunceford JK, et al. Effect of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2632-2637.

31. DeFronzo RA, Ratner RE, Han J, et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1092-1100.

32. Barnett AH, Burger J, Johns D, et al. Tolerability and efficacy of exenatide and titrated insulin glargine in adult patients with type 2 diabetes previously uncontrolled with metformin or a sulfonylurea: a multinational, randomized, open-label, two-period, crossover noninferiority trial. Clin Ther. 2007;29:2333-2348.

33. Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:84-90.

34. Charbonnel B, Karasik A, Liu J, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin alone. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2638-2643.

35. Raz I, Chen Y, Wu M, et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:537-550.

36. DeFronzo RA, Hissa MN, Garber AJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of saxagliptin when added to metformin therapy in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes on metformin alone. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1649-1655.

37. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet. 2009;374:39-47.

38. Buse JB, Sesti G, Schmidt WE, et al. Switching to once-daily liraglutide from twice-daily exenatide further improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes using oral agents. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1300-1303.

39. DeFronzo RA, Okerson T, Viswanathan P, et al. Effects of exenatide versus sitagliptin on postprandial glucose, insulin and glucagon secretion, gastric emptying, and caloric intake: a randomized, cross-over study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2943-2952.

40. Pratley RE, Nauck M, Bailey T, et al. Liraglutide versus sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who did not have adequate glycaemic control with metformin: a 26-week, randomised, parallel-group, open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1447-1456.

41. Kendall DM, Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin and a sulfonylurea. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1083-1091.

42. Blonde L, Klein EJ, Han J, et al. Interim analysis of the effects of exenatide treatment on A1C, weight and cardiovascular risk factors over 82 weeks in 314 over-weight patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2006;8:436-447.

43. Nauck MA, Duran S, Kim D, et al. A comparison of twice-daily exenatide and biphasic insulin aspart in patients with type 2 diabetes who were suboptimally controlled with sulfonylurea and metformin: a non-inferiority study. Diabetologia. 2007;50:259-267.

44. Heine RJ, Van Gaal LF, Johns D, et al. Exenatide versus insulin glargine in patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:559-569.

45. Zinman B, Hoogwerf BJ, Duran GS, et al. The effect of adding exenatide to a thiazolidinedione in suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:477-485.

46. Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met+SU): A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2046-2055.

47. Zinman B, Gerich J, Buse JB, et al. Efficacy and safety of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide in combination with metformin and thiazolidinedione in patients with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-4 Met+TZD). Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1224-1230.

48. Hermansen K, Kipnes M, Luo E, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on glimepiride alone or on glimepiride and metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:733-745.

49. Marre M, Shaw J, Brandle M, et al. Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-1 SU). Diabet Med. 2009;26:268-278.

50. Rosenstock J, Brazg R, Andryuk PJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing pioglitazone therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1556-1568.

51. Hollander P, Li J, Allen E, et al. Saxagliptin added to a thiazolidinedione improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes and inadequate control on thiazolidinedione alone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4810-4819.

52. Chacra AR, Tan GH, Apanovitch A, et al. Saxagliptin added to a submaximal dose of sulphonylurea improves glycaemic control compared with uptitration of sulphonylurea in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1395-1406.

Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus: potential role of incretin-based therapies

Glucose-lowering effects of incretin-based therapies

Safety, tolerability, and nonglycemic effects of incretin-based therapies

- Glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP-4) inhibitors effectively lower blood glucose levels in a glucose-dependent manner, which results in a low incidence of hypoglycemia

- Reduction of glycosylated hemoglobin is greater with GLP-1 agonists (up to 1.5%) than with DPP-4 inhibitors (up to 0.9%), as is reduction of postprandial glucose (PPG)

- GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors vary in dosing (frequency, route of administration), contraindications, and requirement for dose adjustments with renal impairment

- GLP-1 agonists are emphasized in the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) 2009 guidelines and the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) 2009 consensus statement

The authors received editorial assistance from the Primary Care Education Consortium and WriteHealth, LLC in the development of this activity and honoraria from the Primary Care Education Consortium. They have disclosed that Dr Campbell is on the advisory board for Daiichi-Sankyo and the speakers bureau for Eli Lilly and Co; Dr Cobble is on the advisory board for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly and Co and speakers bureau for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca/Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novo Nordisk Inc; Dr Reid is on the advisory board and speakers bureau for Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk Inc, and sanofi-aventis; and Dr Shomali is on the advisory board for Novo Nordisk Inc and speakers bureau for Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Co, sanofi-aventis, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Introduction

The selection of glucose-lowering therapies is dependent on many factors, including stage of disease progression, comorbidities, and previous treatments, as highlighted in the 3 cases. Other factors include an agent’s efficacy in lowering blood glucose levels, side effects and tolerability, safety, convenience and ease of use, and cost, as well as a patient’s current glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) level. The mechanisms of action of concurrent glucose-lowering therapies also should be considered, since using therapies with complementary mechanisms is desirable.1 This article will focus on efficacy factors, while nonglycemic factors, including safety and tolerability, will be discussed in the next article in this supplement (“Safety, tolerability, and nonglycemic effects of incretin-based therapies”). Among these many factors, 2 concerning efficacy deserve discussion at this point.

First, the magnitude to which a pharmacologic option typically lowers blood glucose varies from 0.5% to 3.5% as either monotherapy or combination therapy (FIGURE 1).1-3 According to the AACE/ACE 2009 recommendations, monotherapy is appropriate if the initial A1C level is 6.5% to 7.5%, while dual therapy is appropriate if the A1C level is 7.6% to 9.0%. If the A1C level is >9.0%, however, combination (dual or triple) therapy is required.4,5 In contrast, the ADA/EASD 2009 consensus statement provides more general options. These treatment recommendations are based on landmark trials that show the risk of microvascular and, perhaps, macrovascular complications are decreased substantially.

The second factor to consider is the effectiveness of each agent in lowering both fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and PPG. As demonstrated by Monnier et al, at an A1C level of approximately 8% to 8.5%, FPG and PPG contribute equally to the A1C level.6 At A1C >8.5%, the contribution of FPG increases and PPG decreases. Conversely, at A1C <8%, the contribution of PPG increases and FPG decreases. Thus, the increasing predominance of PPG as patients gain better glycemic control suggests that an agent that effectively lowers both FPG and PPG is needed to achieve the target glycemic goal of ≤7%.

The correlation between PPG and cardiovascular risk is also worth mentioning here. A number of studies have linked elevated PPG levels to increased cardiovascular risk,7-10 and 2 studies have shown PPG to be more predictive than FPG for cardiovascular risk.11,12 One recent study, NAVIGATOR, sought to explore this connection further but could not provide definitive results.13,14 While the study found that 5 years of nateglinide provided no protection against progression of cardiovascular disease in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and cardiovascular disease (or risk factors), it also revealed a paradoxical increase in PPG levels in patients taking the drug. Research on this issue will no doubt continue. The agents that provide the greatest reduction in PPG are insulin, GLP-1 agonists, and pramlintide.4 Of course, benefits of glycemic control must be weighed against potential adverse effects of each agent, as will be discussed in the next article.

FIGURE 1 Range of A1C lowering by class of glucose-lowering agent as monotherapy or by lifestyle modification1-3

AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; DPP-4 I, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; GLP-1 A, glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist.

a Adapted to include sitagliptin and saxagliptin.

b Adapted to include exenatide and liraglutide.

Selecting initial therapy

Metformin, in combination with lifestyle intervention, has become the recommended first-line pharmacologic agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), unless there is a contraindication, such as renal disease, hepatic disease, heart failure, gastrointestinal intolerance, or risk of lactic acidosis. This is because of its efficacy, safety, absence of weight gain, and relatively low cost.1,4 But how should therapy be modified if metformin is no longer effective in maintaining glycemic control or if it is contraindicated? Let’s return to our 3 cases and focus on the glycemic effects of the glucose-lowering agents. (The next article focuses on nonglycemic effects.) As a reminder, in these cases we address dual oral therapy failure, intolerance to metformin monotherapy, and metformin failure.

Modifying therapy

As we focus our attention on the GLP-1 agonists (exenatide, liraglutide) and DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, saxagliptin), we will keep in mind the current indications and limitations of use, as approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (TABLE 1).15-19 We also need to keep in mind the increasing role of the GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in the treatment of patients with T2DM, as reflected in the ADA/EASD 2009 consensus guidelines1 and especially the 2009 consensus statement by the AACE/ACE (FIGURE 2).4 Finally, as described in the 2010 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes by the ADA, in reflection of recent clinical trials such as ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VADT, the target glycemic goal must be carefully determined based on many factors, including patient comorbidity, duration of T2DM, life expectancy, and history of hypoglycemia.20

TABLE 1

Approved indications and limitations of the GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors15-19

| Class/agents | Indications and usage | Limitations of use |

|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 agonists | ||

| Exenatide | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied in combination with insulin. Has not been studied sufficiently in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Use with caution. Do not use if CrCl <30 mL/min or in ESRD. Use with caution in patients with renal transplantation. |

| Liraglutide | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied in combination with insulin. Has not been studied sufficiently in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Use with caution. Not recommended as first-line therapy for patients inadequately controlled with diet and exercise. No dosing adjustment; use with caution in patients with renal disease. |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | ||

| Sitagliptin | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied sufficiently in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Use with caution. Dose is reduced to 50 mg OD when CrCl ≥30 to <50 mL/min and to 25 mg OD when CrCL <30 mL/min or in ESRD requiring dialysis. |

| Saxagliptin | Adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM. | Not for treatment of T1DM or diabetic acidosis. Has not been studied in combination with insulin. Dose is reduced to 2.5 mg OD when CrCl ≤50 mL/min or in ESRD requiring dialysis. |

| DPP, dipeptidyl peptidase; ESRD, end stage renal disease; GLP, glucagon-like peptide; OD, once daily; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. | ||

FIGURE 2 An algorithm for glycemic control by the AACE/ACE*4,5

A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; MET, metformin; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

*To achieve A1C goal ≤6.5%, which may not be appropriate for all patients.

**For patients with diabetes and A1C <6.5%, pharmacologic Rx may be considered.

***If A1C goal not achieved safely.

†Preferred initial agent.

1DPP-4 if ↑PPG and ↑FPG or GLP-1 if ↑↑PPG.

2TZD if metabolic syndrome and/or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

3AGI if ↑PPG.

4Glinide if ↑PPG or SU if ↑FPG.

5Low-dose secretagogue recommended.

6a) Discontinue insulin secretagogue with multidose insulin; b) Can use pramlintide with prandial insulin.

7Decrease secretagogue by 50% when added to GLP-1 or DPP-4.

8If A1C <8.5%, combination Rx with agents that cause hypoglycemia should be used with caution.

9If A1C >8.5%, in patients on dual therapy, insulin should be considered.

Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, et al. Statement by an American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: an algorithm for glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:540-559. [Published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2009;15:768-770]. Reprinted with permission from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Case 1

This 53-year-old man was recently diagnosed with T2DM, with a baseline A1C of 7.5%. He is intolerant of metformin and wants to be treated with an alternative medication. In the case of metformin intolerance or a contraindication to metformin, a thiazolidinedione, DPP-4 inhibitor, GLP-1 agonist, or α-glucosidase inhibitor is recommended by the AACE/ACE if the patient’s A1C level is 6.5% to 7.5% (FIGURE 2).4,5 The safety and tolerability associated with each treatment option, such as hypoglycemia and weight gain, should be discussed with the patient.

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors as monotherapy

Use of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors as monotherapy in combination with lifestyle intervention has been investigated in several clinical trials.2,3,21-25 Generally, as monotherapy, DPP-4 inhibitors have been shown to reduce A1C by 0.5% to 0.9% and GLP-1 agonists by 0.5% to 1.5%.1-3 Increasing the dose provides additional modest glucose reduction. For our patient in Case 1, therefore, either of the DPP-4 inhibitors, sitagliptin or saxagliptin, would be expected to reduce his A1C from his current level of 7.5% to the target level of <7.0%. The GLP-1 agonists, exenatide or liraglutide, would also be expected to reduce his A1C to the target level.

Results of clinical trials have shown that monotherapy with a DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist reduces FPG levels by 11 to 22 mg/dL and 11 to 61 mg/dL, respectively. Reductions in PPG levels range from 24 to 35 mg/dL for the DPP-4 inhibitors and 21 to 48 mg/dL for the GLP-1 agonists. The substantial reduction in PPG is especially important as the A1C level drops to <8.0%6 and approaches the target level of <7.0%, as is the case with this patient.

The greater reductions in FPG and PPG observed with GLP-1 agonists compared with DPP-4 inhibitors likely stem from the pharmacologic level of GLP-1 activity achieved with the GLP-1 agonists and their direct action on the GLP-1 receptor,26-28 which is in contrast to the indirect action of the DPP-4 inhibitors and the resulting lower physiologic levels of endogenous GLP-1.29

The glucose-lowering ability of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists appears to be affected by the baseline A1C level and history of previous treatment. A monotherapy trial with sitagliptin showed that patients with a baseline A1C level ≥9.0% experienced a reduction in A1C of 1.5% compared with 0.6% for those with a baseline A1C level <8.0%.30 For the patient in Case 1, the reduction of 0.6% would be sufficient to lower his A1C to <7.0%.

Similarly, limited data suggest that patients previously treated with glucose-lowering therapy achieve a smaller reduction in A1C compared with those managed with diet and exercise alone. In a study by Garber et al,2 patients previously managed with diet and exercise alone achieved a reduction in A1C of 1.2% and 1.6% with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg once daily, respectively, vs 0.5% and 0.7% for those previously treated with glucose-lowering monotherapy.

In summary, data from clinical trials support the efficacy of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists as monotherapy in combination with lifestyle intervention. In the case of this 53-year-old man with an A1C level of 7.5%, either of the 2 DPP-4 inhibitors or the 2 GLP-1 agonists would provide sufficient glucose-lowering to achieve the target A1C level of <7.0%. Furthermore, although a greater reduction has been observed with GLP-1 agonists (0.5% to 1.5%), the DPP-4 inhibitors also should provide for significant reduction (0.5% to 0.9%) of this patient’s PPG level.

We now turn our attention to the glycemic effects of the GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with 1 or more pharmacologic agents.

Case 2

This 47-year-old man was diagnosed with T2DM 2.5 years ago. The addition of pioglitazone to the combination of lifestyle intervention and metformin has resulted in significant edema and weight gain. He refuses to take a diuretic because of previous experience and wants to discontinue his pioglitazone. He currently has an A1C of 7.0%. What should replace pioglitazone for this patient, who is no longer achieving glycemic control with lifestyle intervention and metformin?

For a patient with an A1C level of 7.6% to 9.0%, the AACE/ACE 2009 guidelines suggest adding a GLP-1 agonist, DPP-4 inhibitor, or thiazolidinedione (FIGURE 2).4,5 Among these 3 options, GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors are preferred due to both their efficacy data when combined with metformin and their overall safety profiles. The GLP-1 agonists are preferred over the DPP-4 inhibitors due to better reduction of PPG levels and potential for substantial weight loss. Thiazolidinediones would be the third choice because of their risks of weight gain, edema, congestive heart failure, and fractures.4

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with metformin

Many clinical trials have been conducted with GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with lifestyle intervention and metformin (TABLE 2).31-36 These trials generally show similar trends in A1C reduction as with monotherapy, although a somewhat greater reduction has been seen with GLP-1 agonists compared with DPP-4 inhibitors. Increasing the dose may provide additional modest glucose reduction. As is typical with monotherapy, patients with a higher baseline A1C level (ie, ≥9.0%) achieve greater A1C reduction. The same holds true for reductions in FPG and PPG levels. For the patient in Case 2, who had an A1C level of 7.8% prior to addition of pioglitazone, discontinuation of pioglitazone and addition of either exenatide or liraglutide to lifestyle intervention and metformin would be expected to lower his A1C level to the target of <7.0%. Although possible, it is unlikely that addition of sitagliptin or saxagliptin would achieve the target A1C level.

TABLE 2

Selected clinical trials of incretin-based therapies as add-on therapy to metformin31-36

| Agent/clinical trial | Duration (wk) | A1C (%) | % Patients achieving A1C < 7% | FPG (mg/dL) | PPG (mg/dL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | |||

| Exenatide (E) | ||||||||

| DeFronzo, 200531 | 30 | |||||||

| E, 5 μg BID | 8.3 | –0.4 | 32 | 176 | –7 | NR | NR | |

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.2 | –0.8 | 46 | 168 | –10 | NR | NR | |

| Placebo | 8.2 | +0.1 | 13 | 170 | +14 | NR | NR | |

| Barnett, 200732 | 32 | |||||||

| E, 5 μg BID x 4 wk, then 10 μg BID | 9.0 | -1.4 | 38 | NR | –52 | NR | NR | |

| Glargine | 9.0 | -1.4 | 40 | NR | –74 | NR | NR | |

| Liraglutide (L) | ||||||||

| Nauck, 200933 | 26 | |||||||

| L, 0.6 mg OD | 8.4 | –0.7 | 28 | 184 | –20 | NR | –31 | |

| L, 1.2 mg OD | 8.3 | –1.0 | 35 | 178 | –29 | NR | –41 | |

| L, 1.8 mg OD | 8.4 | –1.0 | 42 | 182 | –31 | NR | –47 | |

| Glim, 4 mg OD | 8.4 | –1.0 | 36 | 180 | –23 | NR | –45 | |

| Placebo | 8.4 | +0.1 | 11 | 180 | +7 | NR | +11 | |

| Sitagliptin (Si) | ||||||||

| Charbonnel, 200634 | 24 | |||||||

| Si, 100 mg OD | 8.0 | –0.7 | 47 | 169 | –16 | NR | NR | |

| Placebo | 8.0 | 0 | 18 | 173 | +9 | NR | NR | |

| Raz, 200835 | 18a/30 | |||||||

| Si, 100 mg OD | 9.3 | –1.0 | 22 | 202 | –29 | NR | –68a | |

| Placebo | 9.1 | 0 | 3 | 198 | –4 | NR | –14a | |

| Saxagliptin (Sa) | ||||||||

| DeFronzo, 200936 | 24 | |||||||

| Sa, 2.5 mg OD | 8.1 | –0.6 | 37 | 174 | –14 | NR | –62 | |

| Sa, 5 mg OD | 8.1 | –0.7 | 44 | 180 | –22 | NR | –58 | |

| Sa, 10 mg OD | 8.0 | –0.6 | 44 | 176 | –21 | NR | –50 | |

| Placebo | 8.1 | +0.1 | 17 | 174 | +1 | NR | –18 | |

| A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; BID, twice daily; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; Glim, glimepiride; NR, not reported; OD, once daily; PPG, postprandial glucose. aMeasured at 18 weeks. | ||||||||

Choosing among incretin-based therapies

The choice of 1 GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor over another can be difficult, but recent data from 3 clinical trials provide some guidance in terms of efficacy and safety. Each of these trials has been a direct comparison of add-on therapy with 2 incretin-based therapies. The first, by Buse et al, was an open-label comparison of exenatide 10 μg twice daily with liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily for 26 weeks.37 Patients with inadequately controlled T2DM on maximally tolerated doses of metformin, sulfonylurea, or both participated in the study (N=464). The mean change in A1C level from baseline to Week 26 was significantly greater with liraglutide than with exenatide (+1.1% vs +0.8%, respectively; P<.0001) (FIGURE 3A).37 The difference between the 2 groups was greatest for patients with a baseline A1C ≥10% (liraglutide, –2.4%; exenatide, –1.2%). Furthermore, more patients in the liraglutide group than in the exenatide group achieved an A1C level <7% (54% vs 43%; P=.0015). This may have been a result of a significantly greater reduction in FPG with liraglutide than with exenatide (29 vs 11 mg/dL; P<.0001). The reduction in PPG after breakfast and after dinner (but not after lunch) from baseline to Week 26, however, was significantly greater with exenatide than with liraglutide (FIGURE 3B).37 Liraglutide increased mean fasting insulin secretion (+12.4 pmol/L), whereas there was a small reduction with exenatide (–1.4 pmol/L; P=.0355). Fasting glucagon secretion was reduced in both the liraglutide and exenatide groups, but the difference was not significant (–19.4 vs –12.3 ng/L; P=.1436). A 14-week extension of this study showed that patients who were switched from exenatide to liraglutide experienced a significant further reduction in A1C (–0.3%), FPG (–16 mg/dL), and body weight (–0.9 kg) (P<.0001 for all mean values).38 In those who continued liraglutide, A1C (–0.1%) and FPG (–4 mg/dL) levels remained relatively stable, while body weight was further reduced (–0.4 kg) (P<.009).

The second study was a crossover trial by DeFronzo et al that compared exenatide with sitagliptin in patients inadequately controlled with metformin (N=95).39 In addition to maintaining a stable dose of metformin, patients received either exenatide 5 μg twice daily for 1 week followed by 10 μg twice daily for 1 week, or sitagliptin 100 mg every morning for 2 weeks. Patients were then crossed over to the other treatment. While the mean change from baseline FPG (178 mg/dL) was similar in the exenatide and sitagliptin groups (–15 vs –19 mg/dL; P=.3234), the change from baseline 2-hour PPG (245 mg/dL) was –112 mg/dL for exenatide vs –37 mg/dL for sitagliptin (P<.0001). Following crossover, the patients who were switched from exenatide to sitagliptin experienced an increase in PPG of approximately 73 mg/dL (from 133 to 205 mg/dL), whereas those switched from sitagliptin to exenatide experienced a further reduction of –76 mg/dL (from 209 to 133 mg/dL). Consistent with these observations, exenatide was more effective than sitagliptin in augmenting postprandial insulin secretion and suppressing postprandial glucagon secretion. Exenatide, but not sitagliptin, significantly slowed gastric emptying (P<.0001).

In the third trial, Pratley et al compared the addition of liraglutide 1.2 mg or 1.8 mg and sitagliptin 100 mg once daily in patients inadequately controlled with metformin 1500 mg daily or more (N=665).40 From a mean A1C level of 8.5% at baseline, reductions in A1C after 26 weeks were 1.2% for liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.5% for liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 0.9% for sitagliptin (P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses). Mean reductions in FPG were 34 mg/dL for liraglutide 1.2 mg and 39 mg/dL for liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 15 mg/dL for sitagliptin. Weight decreased in all 3 groups but by significantly more with liraglutide: 2.9 kg with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 3.4 kg with liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 1.0 kg with sitagliptin (P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses). Both liraglutide doses resulted in significant improvements from baseline in homeostasis model assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-B): 27.23% with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 28.70% with liraglutide 1.8 mg vs 4.18% with sitagliptin (P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses), whereas no treatment differences were observed for HOMA–insulin resistance or fasting insulin concentration.

The results of these trials indicate that for this 47-year-old man, a GLP-1 agonist would be a better choice to replace pioglitazone, primarily because the A1C reduction of ≥1.0% that can be achieved with this class of drug, and which is needed in this case, is greater than the reduction that can be expected with a DPP-4 inhibitor. Other issues such as weight loss and low individual incidence of hypoglycemia, which also need to be considered, are discussed in the next article.

FIGURE 3 Comparison of glucose-lowering effects of liraglutide and exenatide37

A, Change in glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) level from baseline to Week 26 with liraglutide 1.8 mg once a day or exenatide 10 μg twice a day.

B, Efficacy of treatment with liraglutide 1.8 mg once a day vs exenatide 10 μg twice a day: 7-point self-measured plasma glucose profiles from baseline to Week 26.

Reprinted with permission from: Lancet. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). 2009;374:39-47. Copyright Elsevier, 2009.

Case 3

This 68-year-old woman was diagnosed with T2DM 5 years ago. She has experienced disease progression with a rising A1C level despite dual oral therapy. Her current A1C is 7.4%. She also has peripheral arterial disease and osteoporosis, both of which are being treated. For a patient who has failed dual oral therapy with metformin and another agent, the AACE/ACE guidelines suggest the addition of a DPP-4 inhibitor, GLP-1 agonist, or thiazolidinedione (FIGURE 2).4,5 If a DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist is added, the dose of the sulfonylurea should be decreased by 50% due to the increased risk of hypoglycemia.5 Her mild renal insufficiency is also a consideration.

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with metformin and other oral agents

Many clinical trials have been conducted with a GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor in combination with lifestyle intervention, metformin, and 1 or 2 other agents. As shown in TABLE 3,41-48 the reductions in A1C observed when a GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor is added to dual therapy are generally similar to those observed with GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor monotherapy, although reductions of up to 1.5% have been observed with the addition of liraglutide.46,47 Similarly, reductions in FPG with combination therapy—7 to 74 mg/dL with GLP-1 agonists and 14 to 29 mg/dL with DPP-4 inhibitors—have been comparable to those observed with monotherapy. These results provide evidence of the effectiveness of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in further lowering blood glucose levels when added to dual therapy in patients with advanced disease.

TABLE 3

Selected clinical trials of incretin-based therapies added to combination therapy41-48

| Agent/clinical trial | Combination/duration (wk) | A1C (%) | % Patients achieving A1C <7% | FPG (mg/dL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change | Baseline | Change | |||

| Exenatide (E) | ||||||

| Kendall, 200541 | Met + SU/30 | |||||

| E, 5 μg BID | 8.5 | -0.6 | 27 | 182 | -9 | |

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.5 | -0.6 | 34 | 178 | -11 | |

| Placebo | 8.5 | +0.2 | 9 | 180 | +14 | |

| Blonde, 200642 | Met + SU/52 | |||||

| E, 5 μg BID | 8.3 | -1.1 | 48 | 173 | -16 | |

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.3 | -1.1 | 48 | 173 | -16 | |

| Nauck, 200743 | Met + SU/52 | |||||

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.6 | -1.0 | 32 | 198 | -32 | |

| Aspart 70/30 BID | 8.6 | -0.9 | 24 | 203 | -31 | |

| Heine, 200544 | Met + SU/26 | |||||

| E, 10 μg BID | 8.2 | -1.1 | 46 | 182 | -26 | |

| Glargine OD | 8.3 | -1.1 | 48 | 187 | -52 | |

| Zinman, 200745 | TZD±Met/16 | |||||

| E, 10 μg BID | 7.9 | -0.9 | 62 | 164 | -29 | |

| Placebo | 7.9 | +0.1 | 16 | 159 | +2 | |

| Liraglutide (L) | ||||||

| Russell-Jones, 200946 | Met + Glim/26 | |||||

| L, 1.8 mg OD | 8.3 | -1.3 | NR | 164 | -28 | |

| Glargine | 8.2 | -1.1 | NR | 164 | -32 | |

| Placebo | 8.3 | -0.2 | NR | 169 | +10 | |

| Zinman, 200947 | Met + Rosi/26 | |||||

| L, 1.2 mg OD | 8.5 | -1.5 | 58 | 182 | -43 | |

| L, 1.8 mg OD | 8.6 | -1.5 | 54 | 185 | -48 | |

| Placebo | 8.4 | -0.5 | 28 | 180 | -9 | |

| Sitagliptin (Si) | ||||||

| Hermansen, 200748 | Glim±Met/24 | |||||

| Si, 100 mg OD | 8.3 | -0.5 | 17 | 181 | -4 | |

| Placebo | 8.3 | +0.3 | 5 | 182 | +16 | |

| A1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; BID, twice daily; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; Glim, glimepiride; Met, metformin; NR, not reported; OD, once daily; Rosi, rosiglitazone; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione. | ||||||

GLP-1 agonist and DPP-4 inhibitor trials compared with insulin

While sitagliptin is the only one of the 4 incretin-based therapies approved for use in combination with insulin (TABLE 1),15-19 several studies have compared the efficacy of adding exenatide, liraglutide, or sitagliptin with adding insulin glargine to other glucose-lowering therapy.32,43,44,46 These trials have generally shown a GLP-1 agonist to provide glucose-lowering ability comparable to that with insulin glargine. For example, separate 26-week trials compared exenatide and liraglutide with insulin glargine in patients suboptimally controlled with metformin and a sulfonylurea. In the first (N=551), both exenatide and insulin glargine decreased the mean A1C level 1.1%.44 The FPG level decreased 26 mg/dL in the exenatide group and 52 mg/dL in the insulin glargine group (P<.001). On the other hand, exenatide reduced PPG excursions compared with insulin glargine. In the second trial (N=576), the A1C level decreased 1.3% in the liraglutide group vs 1.1% in the insulin glargine group (P=.0015) and 0.2% in the placebo group (both, P<.0001 vs placebo).46 The FPG level decreased 28 and 32 mg/dL, respectively, in the liraglutide and insulin glargine groups and increased 10 mg/dL in the placebo group. Postprandial glucose decreased 33 and 29 mg/dL, respectively, in the liraglutide and glargine groups but did not change in the placebo group (P<.0001 liraglutide vs placebo). These trials showed that addition of exenatide or liraglutide to metformin and a sulfonylurea provides comparable glucose reduction to addition of insulin glargine.

GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in combination with agents other than metformin

While metformin is the cornerstone of glucose-lowering therapy, GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors have been investigated as dual therapy in combination with agents other than metformin.49-52

The addition of liraglutide 0.6 mg, 1.2 mg, or 1.8 mg; rosiglitazone 4 mg; or placebo to glimepiride 2 mg to 4 mg was compared in patients with inadequately controlled blood glucose on monotherapy or combination therapy, excluding insulin (N=1041).49 After 26 weeks, the mean A1C level decreased 1.1% with either liraglutide 1.2 mg or 1.8 mg once daily and 0.4% with rosiglitazone 4 mg daily but increased 0.2% with placebo (all, P<.0001). Similarly, the decrease in FPG was significantly greater with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg compared with placebo (treatment difference, 47 mg/dL; P<.0001) and rosiglitazone 4 mg (treatment difference, 13 mg/dL; P<.006). Reductions in PPG were also significantly greater with liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg (45 and 49 mg/dL, respectively) than with rosiglitazone 4 mg (32 mg/dL; P≤.043 vs liraglutide 1.2 mg; P=.0022 vs liraglutide 1.8 mg) and placebo (7 mg/dL; P<.0001 for both liraglutide doses).

Two trials have investigated treatment with a DPP-4 inhibitor in combination with a thiazolidinedione. In 1 trial, patients (N=353) were randomized to receive sitagliptin 100 mg once daily or placebo in combination with pioglitazone 30 mg to 45 mg daily.50 After 24 weeks, the mean A1C level decreased 0.9% with the addition of sitagliptin and 0.2% with placebo (P<.001). The FPG level decreased 17 mg/dL in the sitagliptin group and increased 1 mg/dL in the placebo group (P<.001). Similar changes in A1C and FPG levels were observed in another trial involving the addition of saxagliptin 2.5 mg or 5 mg once daily to pioglitazone 30 mg to 45 mg or rosiglitazone 4 mg to 8 mg once daily.51 Reduction in the PPG area under the curve was greater with either dose of saxagliptin than with placebo.

The addition of saxagliptin to a submaximal dose of glyburide was compared with uptitration of glyburide in 768 patients with T2DM.52 Patients were randomized to receive saxagliptin 2.5 mg or 5 mg once daily in combination with glyburide 7.5 mg once daily, or glyburide 10 mg to 15 mg once daily for 24 weeks. The mean A1C level decreased 0.5% and 0.6% in the saxagliptin 2.5 mg and 5 mg groups, respectively, and increased 0.1% in the glyburide uptitration group (P<.0001 vs both saxagliptin groups). The FPG level decreased 7 and 10 mg/dL in the saxagliptin 2.5 mg and 5 mg groups, respectively, and increased 1 mg/dL in the glyburide uptitration group (P=.0218 and P=.002, respectively). Similar changes were observed in PPG (P<.0001).

These trials demonstrate that the efficacy of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors extend to combined use with agents other than metformin.

Summary

Extensive experience from randomized clinical trials demonstrates the efficacy of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors as monotherapy and in combination with metformin and other agents, although reductions in FPG and PPG, and consequently A1C, are greater with GLP-1 agonists than with DPP-4 inhibitors. This difference may result from the pharmacologic levels of GLP-1 activity that are achieved with the GLP-1 agonists and their direct action on the GLP-1 receptor. The GLP-1 agonists have attributes that would make either of them an appropriate choice in the management of all 3 patients in our case studies, while either DPP-4 inhibitor would be an appropriate choice for Case 1. Differences in dosing, administration, safety, and tolerability should be considered.

Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus: potential role of incretin-based therapies

Glucose-lowering effects of incretin-based therapies

Safety, tolerability, and nonglycemic effects of incretin-based therapies

- Glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP-4) inhibitors effectively lower blood glucose levels in a glucose-dependent manner, which results in a low incidence of hypoglycemia

- Reduction of glycosylated hemoglobin is greater with GLP-1 agonists (up to 1.5%) than with DPP-4 inhibitors (up to 0.9%), as is reduction of postprandial glucose (PPG)

- GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors vary in dosing (frequency, route of administration), contraindications, and requirement for dose adjustments with renal impairment

- GLP-1 agonists are emphasized in the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) 2009 guidelines and the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) 2009 consensus statement

The authors received editorial assistance from the Primary Care Education Consortium and WriteHealth, LLC in the development of this activity and honoraria from the Primary Care Education Consortium. They have disclosed that Dr Campbell is on the advisory board for Daiichi-Sankyo and the speakers bureau for Eli Lilly and Co; Dr Cobble is on the advisory board for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly and Co and speakers bureau for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca/Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novo Nordisk Inc; Dr Reid is on the advisory board and speakers bureau for Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk Inc, and sanofi-aventis; and Dr Shomali is on the advisory board for Novo Nordisk Inc and speakers bureau for Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Co, sanofi-aventis, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Introduction