User login

Case Management Improves Quality of Life for Cancer Survivors

After cancer treatment, a new challenge emerges as patients negotiate reentry into their everyday lives. These patients often need multifaceted, simultaneous, and ongoing help with physical, emotional, and psychological issues. And they’re often dealing with a multiplicity of health care providers.

Researchers from University of Zurich and Centres for Addiction Medicine in Zurich, Switzerland, saw similarities between these needs and those of patients with chronic medical conditions. They hypothesized that case management—like that for chronic diseases—could work for cancer survivors perhaps even better than usual care. Among other duties, case managers can assess individual needs, identify barriers, ensure coordination among care providers, and perhaps most important, promote empowering self-management skills and self-efficacy. All of which could help cancer survivors cope with the long-term consequences of cancer and improve health-related quality of life (QOL).

Related: Putting the Focus on Quality of Life in Cancer Care

The researchers designed an intervention study in which 5 oncology nurse case managers met with 95 patients at least once a month for 3 months, then conducted telephone follow-ups for 9 months. Questionnaires measured health-related QOL at 12 months via the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), self-efficacy, and concordance of received care with the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC).

Although the researchers’ study did not show a significant absolute difference between the groups in FACT-G after 12 months, all scores improved in the case management group compared with the usual care group. Overall, case management clearly boosted QOL and self-efficacy and aligned health care with the chronic care model.

Related: Quality of Supportive Care for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer in the VHA

According to the researchers, their study is the first, to their knowledge, to examine the effect of case management on the QOL of early cancer survivors. Several factors help explain the intervention’s success: (1) The case managers provided important information on long-term symptoms and available services and therapies; (2) They offered a continuity of care when treatment appointments ceased and medical follow-up visits were less frequent; and (3) They offered support to cope with the psychological issues of the reentry phase.

All in all, the researchers say their findings show case management is a practical approach to bridging a “fragmented oncological health care system” and addressing the heterogenic needs of cancer survivors.

Source:

Scherz N, Bachmann-Mettler I, Chmiel C. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):223.

doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3213-9.

After cancer treatment, a new challenge emerges as patients negotiate reentry into their everyday lives. These patients often need multifaceted, simultaneous, and ongoing help with physical, emotional, and psychological issues. And they’re often dealing with a multiplicity of health care providers.

Researchers from University of Zurich and Centres for Addiction Medicine in Zurich, Switzerland, saw similarities between these needs and those of patients with chronic medical conditions. They hypothesized that case management—like that for chronic diseases—could work for cancer survivors perhaps even better than usual care. Among other duties, case managers can assess individual needs, identify barriers, ensure coordination among care providers, and perhaps most important, promote empowering self-management skills and self-efficacy. All of which could help cancer survivors cope with the long-term consequences of cancer and improve health-related quality of life (QOL).

Related: Putting the Focus on Quality of Life in Cancer Care

The researchers designed an intervention study in which 5 oncology nurse case managers met with 95 patients at least once a month for 3 months, then conducted telephone follow-ups for 9 months. Questionnaires measured health-related QOL at 12 months via the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), self-efficacy, and concordance of received care with the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC).

Although the researchers’ study did not show a significant absolute difference between the groups in FACT-G after 12 months, all scores improved in the case management group compared with the usual care group. Overall, case management clearly boosted QOL and self-efficacy and aligned health care with the chronic care model.

Related: Quality of Supportive Care for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer in the VHA

According to the researchers, their study is the first, to their knowledge, to examine the effect of case management on the QOL of early cancer survivors. Several factors help explain the intervention’s success: (1) The case managers provided important information on long-term symptoms and available services and therapies; (2) They offered a continuity of care when treatment appointments ceased and medical follow-up visits were less frequent; and (3) They offered support to cope with the psychological issues of the reentry phase.

All in all, the researchers say their findings show case management is a practical approach to bridging a “fragmented oncological health care system” and addressing the heterogenic needs of cancer survivors.

Source:

Scherz N, Bachmann-Mettler I, Chmiel C. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):223.

doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3213-9.

After cancer treatment, a new challenge emerges as patients negotiate reentry into their everyday lives. These patients often need multifaceted, simultaneous, and ongoing help with physical, emotional, and psychological issues. And they’re often dealing with a multiplicity of health care providers.

Researchers from University of Zurich and Centres for Addiction Medicine in Zurich, Switzerland, saw similarities between these needs and those of patients with chronic medical conditions. They hypothesized that case management—like that for chronic diseases—could work for cancer survivors perhaps even better than usual care. Among other duties, case managers can assess individual needs, identify barriers, ensure coordination among care providers, and perhaps most important, promote empowering self-management skills and self-efficacy. All of which could help cancer survivors cope with the long-term consequences of cancer and improve health-related quality of life (QOL).

Related: Putting the Focus on Quality of Life in Cancer Care

The researchers designed an intervention study in which 5 oncology nurse case managers met with 95 patients at least once a month for 3 months, then conducted telephone follow-ups for 9 months. Questionnaires measured health-related QOL at 12 months via the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), self-efficacy, and concordance of received care with the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC).

Although the researchers’ study did not show a significant absolute difference between the groups in FACT-G after 12 months, all scores improved in the case management group compared with the usual care group. Overall, case management clearly boosted QOL and self-efficacy and aligned health care with the chronic care model.

Related: Quality of Supportive Care for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer in the VHA

According to the researchers, their study is the first, to their knowledge, to examine the effect of case management on the QOL of early cancer survivors. Several factors help explain the intervention’s success: (1) The case managers provided important information on long-term symptoms and available services and therapies; (2) They offered a continuity of care when treatment appointments ceased and medical follow-up visits were less frequent; and (3) They offered support to cope with the psychological issues of the reentry phase.

All in all, the researchers say their findings show case management is a practical approach to bridging a “fragmented oncological health care system” and addressing the heterogenic needs of cancer survivors.

Source:

Scherz N, Bachmann-Mettler I, Chmiel C. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):223.

doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3213-9.

Orthorexia Nervosa: An Obsession With Healthy Eating

First named by Steven Bratman in 1997, orthorexia nervosa (ON) from the Greek ortho, meaning correct, and orexi, meaning appetite, is classified as an unspecified feeding and eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5).1,2

Hypothetical Case

Mr. P is a 30-year-old male who presented to the mental health clinic with his wife. The patient recounted that he had wanted to “be healthy” since childhood and has focused on exercise and proper diet, but anxiety about diet and food intake have steadily increased. Two years ago, he adopted a vegetarian diet by progressively eliminating several foods and food groups from his diet. He now feels “proud” to eat certain organically grown fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and drink only fruit or vegetable juice.

His wife stated that he spent between 3 and 5 hours daily preparing food or talking to friends and family about “correct foods to eat.” He also believed that errors in dietary habits caused physical or mental illnesses. He reported significant guilt and shame whenever he “slips up” on his dietary regimen and eats anything containing seafood, beef, or pork products, which he corrects by a day of fasting. His wife was frustrated because he refused to go to restaurants and started declining offers from friends to eat dinner at their homes unless he could bring his prepared food. He describes feeling “annoyed” when he sees other people eating fast food or meat.

Mr. P reported no significant medical or surgical history. His family history was significant for anxiety in his mother. He used to drink alcohol socially but ceased a few years ago due to its carbohydrate content. He never smoked or used illicit drugs.

A mental status exam revealed a thin male who appeared his stated age. He was cooperative, casually dressed, and made fair eye contact. He spoke clearly with an anxious tone and appropriate rate and volume. His affect was congruent with stated anxious mood. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He reported no paranoia, auditory or visual hallucinations, and suicidal or homicidal ideation.

A physical exam revealed a thin male in no distress who measured 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 145 pounds, which yielded a body mass index of 20.8. His vitals included temperature of 98° F, blood pressure 115/76, pulse 74, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. The remaining physical examination revealed no abnormalities. A complete blood count, thyroid function, urinalysis, and urine drug screens were within normal limits. Comprehensive metabolic profile revealed decreased sodium of 130 meq/L. Electrocardiogram revealed bradycardia.

An ON diagnosis is made primarily through a clinical interview. Collateral information from individuals familiar with the patient can be helpful. Experts have proposed and recently revised criteria for ON (Table). Although the ORTO-15 assessment tool may assist with diagnosis, the tool does not substitute for the clinical interview.

Discussion

There is no reliable measure of prevalence of ON, though Varga and colleagues initially estimated ON to occur in 6.9% of the general population, and ON may occur more frequently in health care professionals and performance artists.3 However, these may be overestimates, as the assessment tool used in the study does not adequately separate people with healthy eating habits from those with ON.4,5

Most prevalence studies were conducted in Europe and Turkey, and prevalence of ON may differ in the U.S. population. A recent assessment determined a prevalence of about 1%, similar to that of other eating disorders.5 No study has reported a correlation between ON and gender, but a survey of 448 college students in the U.S. (mean age 22 years) reported highest ON tendencies in Hispanic/Latino and overweight/obese students.6

Relationship to Other Illnesses

There is significant debate whether ON is a single syndrome, a variance of other syndromes, or a behavioral and culturally influenced attitude.7,8 Although ON may lead to or be comorbid with anorexia nervosa (AN) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), subtle differences exist between ON and these conditions.

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AN, patients must weigh below minimally normal weight for their height and age, have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, and have a disturbed experience of their weight or body shape or cannot recognize the severity of the low weight.2 In contrast, an individual with ON may possess normal or low-normal weight. Patients with AN focus on food quantity, while patients with ON tend to focus on food quality. As summarized by Bratman, “People are ashamed of their anorexia, but they actively evangelize their orthorexia. People with anorexia skip meals; people with orthorexia do not (unless they are fasting). Those with anorexia focus only on avoiding foods, while those with orthorexia both avoid foods they think are bad and embrace foods they think are super-healthy.”9

Similarities between ON and OCD include anxiety, a need to exert control, and perfectionism. However, patients with OCD tend to report distress from compulsive behavior and a desire to change, thus exhibiting insight into their illness.8,10 Similarities between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and ON include perfectionism, rigid thinking, excessive devotion, hypermorality, and a preoccupation with details and perceived rules.11

While no studies have yet described ON as a feature of somatoform disorders, some experts have hypothesized that preoccupation with illness in a patient with somatization disorder may engender a preoccupation with food and diet as a way to combat either real or perceived illness.11 Finally, there is a report of ON associated with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia, and the development of ON may increase risk for future psychotic disorders.11,12

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of ON is unknown, though it is likely multifactorial. Individuals with ON have neurocognitive deficits similar to those seen in patients with AN and OCD, including impairments in set-shifting (flexible problem solving), external attention, and working memory.11,13 Given these cognitive deficits as well as similar symptomatology, there may be analogous brain dysfunction in patients with ON and AN or OCD. Neuroimaging studies of patients with AN have revealed dysregulation of dopamine transmission in the reward circuitry of the ventral striatum and the food regulatory mechanism in the hypothalamus.14

Dysmorphology of and dysfunction in neural circuitry, particularly the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical pathway, have been implicated in OCD.15 Neuroimaging studies have revealed increased volume and activation of the orbitofrontal cortex, which may be associated with obsessions and difficulty with extinction recall.14,15 In contrast, decreased volume and activity of the thalamus may impair its ability to inhibit the orbitofrontal cortex.15,16 Decreased volume and activity of the cingulate gyrus may be associated with difficulty in error monitoring and fear conditioning, while overactivation of the parietal lobe and cerebellum may be associated with compulsive behaviors.15,16

Risk Factors

Factors that contribute to the development of AN and possibly ON include development of food preferences, inherited differences in taste perception, food neophobia or pickiness, being premorbidly overweight or obese, parental feeding practices, and a history of parental eating disorders.14 One survey associated orthorexic tendencies with perfectionism, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, self-classified weight, and fearful and dismissing attachment styles.17 Significant predictors of ON included overweight preoccupation, appearance orientation, and a history of an eating disorder.17

Treatment

In contrast to patients with AN, patients with ON may be easily amenable to treatment, given their pursuit of and emphasis on wellness.18 Experts recommend a multidisciplinary team approach that includes physicians, psychotherapists, and dieticians.11 Treatment may be undertaken in an outpatient setting, but hospitalization for refeeding is recommended in cases with significant weight loss or malnourishment.11 Physical examination and laboratory studies are warranted, as excessive dietary restrictions can lead to weight loss and medical complications similar to those seen in AN, including osteopenia, anemia, hyponatremia, pancytopenia, bradycardia, and even pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.19-21

There are no reported studies exploring the efficacy of psychotherapy or psychotropic medications for patients with ON. However, several treatments have been proposed given the symptom overlap with AN. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be beneficial for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive traits.18 However, patients with ON may refuse medications as unnatural substances.18

Cognitive behavioral therapy may be beneficial to address perfectionism and cognitive distortions, and exposure and response prevention may reduce obsessive-compulsive behaviors.11 Relaxation therapy may reduce mealtime anxiety. Psychoeducation may correct inaccurate beliefs about food groups, purity, and preparation, but it may induce emotional stress for the patient with ON.11

Conclusion

Orthorexia nervosa is perhaps best summarized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors. However, the attempt to attain optimum health through attention to diet may lead to malnourishment, loss of relationships, and poor quality of life.11 It is a little-understood disorder with uncertain etiology, imprecise assessment tools, and no formal diagnostic criteria or classification. Orthorexic characteristics vary from normal to pathologic in degree, and making a diagnosis remains a clinical judgment.22 Further research is needed to develop valid diagnostic tools and determining whether ON should be classified as a unique illness or a variation of other eating or anxiety disorders. Further research also may identify the etiology of ON, thus enabling targeted multidisciplinary treatment.

1. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga J. 1997;136:42-50.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Feeding and eating disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:329-354.

3. Varga M, Dukay-Szabó S, Túry F, van Furth EF. Evidence and gaps in the literature on orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(2):103-111.

4. Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C. Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(2):e28-e32.

5. Dunn TM, Gibbs J, Whitney N, Starosta A. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is less than 1 %: data from a US sample. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;22(1):185-192.

6. Bundros J, Clifford D, Silliman K, Neyman Morris M. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among college students based on Bratman’s test and associated tendencies. Appetite. 2016;101:86-94.

7. Vandereycken W. Media hype, diagnostic fad or genuine disorder? Professionals’ opinions about night eating syndrome, orthorexia, muscle dysmorphia, and emetophobia. Eat Disord. 2011;19(2):145-155.

8. Dell’Osso L, Abelli M, Carpita B, et al. Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1651-1660.

9. Bratman S. Orthorexia: an update. http://www.orthorexia.com/orthorexia-an-update. Updated October 5, 2015. Accessed April 18, 2017.

10. Dunn TM, Bratman S. On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav. 2016;21:11-17.

11. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

12. Saddichha S, Babu GN, Chandra P. Orthorexia nervosa presenting as prodrome of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):110.

13. Koven NS, Senbonmatsu R. A neuropsychological evaluation of orthorexia nervosa. Open J Psychiatry. 2013;3(2):214-222.

14. Gorwood P, Blanchet-Collet C, Chartrel N, et al. New insights in anorexia nervosa. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:256.

15. Milad MR, Rauch SL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathways. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(1):43-51.

16. Tang W, Zhu Q, Gong X, Zhu C, Wang Y, Chen S. Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit abnormalities in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A voxel-based morphometric and fMRI study of the whole brain. Behav Brain Res. 2016;313:17-22.

17. Barnes MA, Caltabiano ML. The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22(1):177-184.

18. Mathieu J. What is orthorexia? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(10):1510-1512.

19. Catalina Zamora ML, Bote Bonaechea B, García Sánchez F, Ríos Rial B. Orthorexia nervosa. A new eating behavior disorder? [in Spanish]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2005;33(1):66-68.

20. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, Yager J, Weintraub P. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

21. Park SW, Kim JY, Go GJ, Jeon ES, Pyo HJ, Kwon YJ. Orthorexia nervosa with hyponatremia, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastimum, pneumothorax, and pancytopenia. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2011;9(1):32-37.

22. Mogallapu RNG, Aynampudi AR, Scarff JR, Lippmann S. Orthorexia nervosa. The Kentucky Psychiatrist. 2012;22(3):3-6.

First named by Steven Bratman in 1997, orthorexia nervosa (ON) from the Greek ortho, meaning correct, and orexi, meaning appetite, is classified as an unspecified feeding and eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5).1,2

Hypothetical Case

Mr. P is a 30-year-old male who presented to the mental health clinic with his wife. The patient recounted that he had wanted to “be healthy” since childhood and has focused on exercise and proper diet, but anxiety about diet and food intake have steadily increased. Two years ago, he adopted a vegetarian diet by progressively eliminating several foods and food groups from his diet. He now feels “proud” to eat certain organically grown fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and drink only fruit or vegetable juice.

His wife stated that he spent between 3 and 5 hours daily preparing food or talking to friends and family about “correct foods to eat.” He also believed that errors in dietary habits caused physical or mental illnesses. He reported significant guilt and shame whenever he “slips up” on his dietary regimen and eats anything containing seafood, beef, or pork products, which he corrects by a day of fasting. His wife was frustrated because he refused to go to restaurants and started declining offers from friends to eat dinner at their homes unless he could bring his prepared food. He describes feeling “annoyed” when he sees other people eating fast food or meat.

Mr. P reported no significant medical or surgical history. His family history was significant for anxiety in his mother. He used to drink alcohol socially but ceased a few years ago due to its carbohydrate content. He never smoked or used illicit drugs.

A mental status exam revealed a thin male who appeared his stated age. He was cooperative, casually dressed, and made fair eye contact. He spoke clearly with an anxious tone and appropriate rate and volume. His affect was congruent with stated anxious mood. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He reported no paranoia, auditory or visual hallucinations, and suicidal or homicidal ideation.

A physical exam revealed a thin male in no distress who measured 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 145 pounds, which yielded a body mass index of 20.8. His vitals included temperature of 98° F, blood pressure 115/76, pulse 74, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. The remaining physical examination revealed no abnormalities. A complete blood count, thyroid function, urinalysis, and urine drug screens were within normal limits. Comprehensive metabolic profile revealed decreased sodium of 130 meq/L. Electrocardiogram revealed bradycardia.

An ON diagnosis is made primarily through a clinical interview. Collateral information from individuals familiar with the patient can be helpful. Experts have proposed and recently revised criteria for ON (Table). Although the ORTO-15 assessment tool may assist with diagnosis, the tool does not substitute for the clinical interview.

Discussion

There is no reliable measure of prevalence of ON, though Varga and colleagues initially estimated ON to occur in 6.9% of the general population, and ON may occur more frequently in health care professionals and performance artists.3 However, these may be overestimates, as the assessment tool used in the study does not adequately separate people with healthy eating habits from those with ON.4,5

Most prevalence studies were conducted in Europe and Turkey, and prevalence of ON may differ in the U.S. population. A recent assessment determined a prevalence of about 1%, similar to that of other eating disorders.5 No study has reported a correlation between ON and gender, but a survey of 448 college students in the U.S. (mean age 22 years) reported highest ON tendencies in Hispanic/Latino and overweight/obese students.6

Relationship to Other Illnesses

There is significant debate whether ON is a single syndrome, a variance of other syndromes, or a behavioral and culturally influenced attitude.7,8 Although ON may lead to or be comorbid with anorexia nervosa (AN) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), subtle differences exist between ON and these conditions.

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AN, patients must weigh below minimally normal weight for their height and age, have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, and have a disturbed experience of their weight or body shape or cannot recognize the severity of the low weight.2 In contrast, an individual with ON may possess normal or low-normal weight. Patients with AN focus on food quantity, while patients with ON tend to focus on food quality. As summarized by Bratman, “People are ashamed of their anorexia, but they actively evangelize their orthorexia. People with anorexia skip meals; people with orthorexia do not (unless they are fasting). Those with anorexia focus only on avoiding foods, while those with orthorexia both avoid foods they think are bad and embrace foods they think are super-healthy.”9

Similarities between ON and OCD include anxiety, a need to exert control, and perfectionism. However, patients with OCD tend to report distress from compulsive behavior and a desire to change, thus exhibiting insight into their illness.8,10 Similarities between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and ON include perfectionism, rigid thinking, excessive devotion, hypermorality, and a preoccupation with details and perceived rules.11

While no studies have yet described ON as a feature of somatoform disorders, some experts have hypothesized that preoccupation with illness in a patient with somatization disorder may engender a preoccupation with food and diet as a way to combat either real or perceived illness.11 Finally, there is a report of ON associated with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia, and the development of ON may increase risk for future psychotic disorders.11,12

Pathophysiology

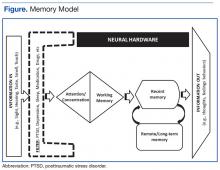

The exact cause of ON is unknown, though it is likely multifactorial. Individuals with ON have neurocognitive deficits similar to those seen in patients with AN and OCD, including impairments in set-shifting (flexible problem solving), external attention, and working memory.11,13 Given these cognitive deficits as well as similar symptomatology, there may be analogous brain dysfunction in patients with ON and AN or OCD. Neuroimaging studies of patients with AN have revealed dysregulation of dopamine transmission in the reward circuitry of the ventral striatum and the food regulatory mechanism in the hypothalamus.14

Dysmorphology of and dysfunction in neural circuitry, particularly the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical pathway, have been implicated in OCD.15 Neuroimaging studies have revealed increased volume and activation of the orbitofrontal cortex, which may be associated with obsessions and difficulty with extinction recall.14,15 In contrast, decreased volume and activity of the thalamus may impair its ability to inhibit the orbitofrontal cortex.15,16 Decreased volume and activity of the cingulate gyrus may be associated with difficulty in error monitoring and fear conditioning, while overactivation of the parietal lobe and cerebellum may be associated with compulsive behaviors.15,16

Risk Factors

Factors that contribute to the development of AN and possibly ON include development of food preferences, inherited differences in taste perception, food neophobia or pickiness, being premorbidly overweight or obese, parental feeding practices, and a history of parental eating disorders.14 One survey associated orthorexic tendencies with perfectionism, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, self-classified weight, and fearful and dismissing attachment styles.17 Significant predictors of ON included overweight preoccupation, appearance orientation, and a history of an eating disorder.17

Treatment

In contrast to patients with AN, patients with ON may be easily amenable to treatment, given their pursuit of and emphasis on wellness.18 Experts recommend a multidisciplinary team approach that includes physicians, psychotherapists, and dieticians.11 Treatment may be undertaken in an outpatient setting, but hospitalization for refeeding is recommended in cases with significant weight loss or malnourishment.11 Physical examination and laboratory studies are warranted, as excessive dietary restrictions can lead to weight loss and medical complications similar to those seen in AN, including osteopenia, anemia, hyponatremia, pancytopenia, bradycardia, and even pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.19-21

There are no reported studies exploring the efficacy of psychotherapy or psychotropic medications for patients with ON. However, several treatments have been proposed given the symptom overlap with AN. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be beneficial for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive traits.18 However, patients with ON may refuse medications as unnatural substances.18

Cognitive behavioral therapy may be beneficial to address perfectionism and cognitive distortions, and exposure and response prevention may reduce obsessive-compulsive behaviors.11 Relaxation therapy may reduce mealtime anxiety. Psychoeducation may correct inaccurate beliefs about food groups, purity, and preparation, but it may induce emotional stress for the patient with ON.11

Conclusion

Orthorexia nervosa is perhaps best summarized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors. However, the attempt to attain optimum health through attention to diet may lead to malnourishment, loss of relationships, and poor quality of life.11 It is a little-understood disorder with uncertain etiology, imprecise assessment tools, and no formal diagnostic criteria or classification. Orthorexic characteristics vary from normal to pathologic in degree, and making a diagnosis remains a clinical judgment.22 Further research is needed to develop valid diagnostic tools and determining whether ON should be classified as a unique illness or a variation of other eating or anxiety disorders. Further research also may identify the etiology of ON, thus enabling targeted multidisciplinary treatment.

First named by Steven Bratman in 1997, orthorexia nervosa (ON) from the Greek ortho, meaning correct, and orexi, meaning appetite, is classified as an unspecified feeding and eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5).1,2

Hypothetical Case

Mr. P is a 30-year-old male who presented to the mental health clinic with his wife. The patient recounted that he had wanted to “be healthy” since childhood and has focused on exercise and proper diet, but anxiety about diet and food intake have steadily increased. Two years ago, he adopted a vegetarian diet by progressively eliminating several foods and food groups from his diet. He now feels “proud” to eat certain organically grown fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and drink only fruit or vegetable juice.

His wife stated that he spent between 3 and 5 hours daily preparing food or talking to friends and family about “correct foods to eat.” He also believed that errors in dietary habits caused physical or mental illnesses. He reported significant guilt and shame whenever he “slips up” on his dietary regimen and eats anything containing seafood, beef, or pork products, which he corrects by a day of fasting. His wife was frustrated because he refused to go to restaurants and started declining offers from friends to eat dinner at their homes unless he could bring his prepared food. He describes feeling “annoyed” when he sees other people eating fast food or meat.

Mr. P reported no significant medical or surgical history. His family history was significant for anxiety in his mother. He used to drink alcohol socially but ceased a few years ago due to its carbohydrate content. He never smoked or used illicit drugs.

A mental status exam revealed a thin male who appeared his stated age. He was cooperative, casually dressed, and made fair eye contact. He spoke clearly with an anxious tone and appropriate rate and volume. His affect was congruent with stated anxious mood. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He reported no paranoia, auditory or visual hallucinations, and suicidal or homicidal ideation.

A physical exam revealed a thin male in no distress who measured 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 145 pounds, which yielded a body mass index of 20.8. His vitals included temperature of 98° F, blood pressure 115/76, pulse 74, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. The remaining physical examination revealed no abnormalities. A complete blood count, thyroid function, urinalysis, and urine drug screens were within normal limits. Comprehensive metabolic profile revealed decreased sodium of 130 meq/L. Electrocardiogram revealed bradycardia.

An ON diagnosis is made primarily through a clinical interview. Collateral information from individuals familiar with the patient can be helpful. Experts have proposed and recently revised criteria for ON (Table). Although the ORTO-15 assessment tool may assist with diagnosis, the tool does not substitute for the clinical interview.

Discussion

There is no reliable measure of prevalence of ON, though Varga and colleagues initially estimated ON to occur in 6.9% of the general population, and ON may occur more frequently in health care professionals and performance artists.3 However, these may be overestimates, as the assessment tool used in the study does not adequately separate people with healthy eating habits from those with ON.4,5

Most prevalence studies were conducted in Europe and Turkey, and prevalence of ON may differ in the U.S. population. A recent assessment determined a prevalence of about 1%, similar to that of other eating disorders.5 No study has reported a correlation between ON and gender, but a survey of 448 college students in the U.S. (mean age 22 years) reported highest ON tendencies in Hispanic/Latino and overweight/obese students.6

Relationship to Other Illnesses

There is significant debate whether ON is a single syndrome, a variance of other syndromes, or a behavioral and culturally influenced attitude.7,8 Although ON may lead to or be comorbid with anorexia nervosa (AN) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), subtle differences exist between ON and these conditions.

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AN, patients must weigh below minimally normal weight for their height and age, have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, and have a disturbed experience of their weight or body shape or cannot recognize the severity of the low weight.2 In contrast, an individual with ON may possess normal or low-normal weight. Patients with AN focus on food quantity, while patients with ON tend to focus on food quality. As summarized by Bratman, “People are ashamed of their anorexia, but they actively evangelize their orthorexia. People with anorexia skip meals; people with orthorexia do not (unless they are fasting). Those with anorexia focus only on avoiding foods, while those with orthorexia both avoid foods they think are bad and embrace foods they think are super-healthy.”9

Similarities between ON and OCD include anxiety, a need to exert control, and perfectionism. However, patients with OCD tend to report distress from compulsive behavior and a desire to change, thus exhibiting insight into their illness.8,10 Similarities between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and ON include perfectionism, rigid thinking, excessive devotion, hypermorality, and a preoccupation with details and perceived rules.11

While no studies have yet described ON as a feature of somatoform disorders, some experts have hypothesized that preoccupation with illness in a patient with somatization disorder may engender a preoccupation with food and diet as a way to combat either real or perceived illness.11 Finally, there is a report of ON associated with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia, and the development of ON may increase risk for future psychotic disorders.11,12

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of ON is unknown, though it is likely multifactorial. Individuals with ON have neurocognitive deficits similar to those seen in patients with AN and OCD, including impairments in set-shifting (flexible problem solving), external attention, and working memory.11,13 Given these cognitive deficits as well as similar symptomatology, there may be analogous brain dysfunction in patients with ON and AN or OCD. Neuroimaging studies of patients with AN have revealed dysregulation of dopamine transmission in the reward circuitry of the ventral striatum and the food regulatory mechanism in the hypothalamus.14

Dysmorphology of and dysfunction in neural circuitry, particularly the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical pathway, have been implicated in OCD.15 Neuroimaging studies have revealed increased volume and activation of the orbitofrontal cortex, which may be associated with obsessions and difficulty with extinction recall.14,15 In contrast, decreased volume and activity of the thalamus may impair its ability to inhibit the orbitofrontal cortex.15,16 Decreased volume and activity of the cingulate gyrus may be associated with difficulty in error monitoring and fear conditioning, while overactivation of the parietal lobe and cerebellum may be associated with compulsive behaviors.15,16

Risk Factors

Factors that contribute to the development of AN and possibly ON include development of food preferences, inherited differences in taste perception, food neophobia or pickiness, being premorbidly overweight or obese, parental feeding practices, and a history of parental eating disorders.14 One survey associated orthorexic tendencies with perfectionism, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, self-classified weight, and fearful and dismissing attachment styles.17 Significant predictors of ON included overweight preoccupation, appearance orientation, and a history of an eating disorder.17

Treatment

In contrast to patients with AN, patients with ON may be easily amenable to treatment, given their pursuit of and emphasis on wellness.18 Experts recommend a multidisciplinary team approach that includes physicians, psychotherapists, and dieticians.11 Treatment may be undertaken in an outpatient setting, but hospitalization for refeeding is recommended in cases with significant weight loss or malnourishment.11 Physical examination and laboratory studies are warranted, as excessive dietary restrictions can lead to weight loss and medical complications similar to those seen in AN, including osteopenia, anemia, hyponatremia, pancytopenia, bradycardia, and even pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.19-21

There are no reported studies exploring the efficacy of psychotherapy or psychotropic medications for patients with ON. However, several treatments have been proposed given the symptom overlap with AN. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be beneficial for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive traits.18 However, patients with ON may refuse medications as unnatural substances.18

Cognitive behavioral therapy may be beneficial to address perfectionism and cognitive distortions, and exposure and response prevention may reduce obsessive-compulsive behaviors.11 Relaxation therapy may reduce mealtime anxiety. Psychoeducation may correct inaccurate beliefs about food groups, purity, and preparation, but it may induce emotional stress for the patient with ON.11

Conclusion

Orthorexia nervosa is perhaps best summarized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors. However, the attempt to attain optimum health through attention to diet may lead to malnourishment, loss of relationships, and poor quality of life.11 It is a little-understood disorder with uncertain etiology, imprecise assessment tools, and no formal diagnostic criteria or classification. Orthorexic characteristics vary from normal to pathologic in degree, and making a diagnosis remains a clinical judgment.22 Further research is needed to develop valid diagnostic tools and determining whether ON should be classified as a unique illness or a variation of other eating or anxiety disorders. Further research also may identify the etiology of ON, thus enabling targeted multidisciplinary treatment.

1. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga J. 1997;136:42-50.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Feeding and eating disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:329-354.

3. Varga M, Dukay-Szabó S, Túry F, van Furth EF. Evidence and gaps in the literature on orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(2):103-111.

4. Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C. Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(2):e28-e32.

5. Dunn TM, Gibbs J, Whitney N, Starosta A. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is less than 1 %: data from a US sample. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;22(1):185-192.

6. Bundros J, Clifford D, Silliman K, Neyman Morris M. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among college students based on Bratman’s test and associated tendencies. Appetite. 2016;101:86-94.

7. Vandereycken W. Media hype, diagnostic fad or genuine disorder? Professionals’ opinions about night eating syndrome, orthorexia, muscle dysmorphia, and emetophobia. Eat Disord. 2011;19(2):145-155.

8. Dell’Osso L, Abelli M, Carpita B, et al. Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1651-1660.

9. Bratman S. Orthorexia: an update. http://www.orthorexia.com/orthorexia-an-update. Updated October 5, 2015. Accessed April 18, 2017.

10. Dunn TM, Bratman S. On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav. 2016;21:11-17.

11. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

12. Saddichha S, Babu GN, Chandra P. Orthorexia nervosa presenting as prodrome of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):110.

13. Koven NS, Senbonmatsu R. A neuropsychological evaluation of orthorexia nervosa. Open J Psychiatry. 2013;3(2):214-222.

14. Gorwood P, Blanchet-Collet C, Chartrel N, et al. New insights in anorexia nervosa. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:256.

15. Milad MR, Rauch SL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathways. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(1):43-51.

16. Tang W, Zhu Q, Gong X, Zhu C, Wang Y, Chen S. Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit abnormalities in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A voxel-based morphometric and fMRI study of the whole brain. Behav Brain Res. 2016;313:17-22.

17. Barnes MA, Caltabiano ML. The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22(1):177-184.

18. Mathieu J. What is orthorexia? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(10):1510-1512.

19. Catalina Zamora ML, Bote Bonaechea B, García Sánchez F, Ríos Rial B. Orthorexia nervosa. A new eating behavior disorder? [in Spanish]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2005;33(1):66-68.

20. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, Yager J, Weintraub P. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

21. Park SW, Kim JY, Go GJ, Jeon ES, Pyo HJ, Kwon YJ. Orthorexia nervosa with hyponatremia, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastimum, pneumothorax, and pancytopenia. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2011;9(1):32-37.

22. Mogallapu RNG, Aynampudi AR, Scarff JR, Lippmann S. Orthorexia nervosa. The Kentucky Psychiatrist. 2012;22(3):3-6.

1. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga J. 1997;136:42-50.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Feeding and eating disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:329-354.

3. Varga M, Dukay-Szabó S, Túry F, van Furth EF. Evidence and gaps in the literature on orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(2):103-111.

4. Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C. Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(2):e28-e32.

5. Dunn TM, Gibbs J, Whitney N, Starosta A. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is less than 1 %: data from a US sample. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;22(1):185-192.

6. Bundros J, Clifford D, Silliman K, Neyman Morris M. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among college students based on Bratman’s test and associated tendencies. Appetite. 2016;101:86-94.

7. Vandereycken W. Media hype, diagnostic fad or genuine disorder? Professionals’ opinions about night eating syndrome, orthorexia, muscle dysmorphia, and emetophobia. Eat Disord. 2011;19(2):145-155.

8. Dell’Osso L, Abelli M, Carpita B, et al. Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1651-1660.

9. Bratman S. Orthorexia: an update. http://www.orthorexia.com/orthorexia-an-update. Updated October 5, 2015. Accessed April 18, 2017.

10. Dunn TM, Bratman S. On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav. 2016;21:11-17.

11. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

12. Saddichha S, Babu GN, Chandra P. Orthorexia nervosa presenting as prodrome of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):110.

13. Koven NS, Senbonmatsu R. A neuropsychological evaluation of orthorexia nervosa. Open J Psychiatry. 2013;3(2):214-222.

14. Gorwood P, Blanchet-Collet C, Chartrel N, et al. New insights in anorexia nervosa. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:256.

15. Milad MR, Rauch SL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathways. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(1):43-51.

16. Tang W, Zhu Q, Gong X, Zhu C, Wang Y, Chen S. Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit abnormalities in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A voxel-based morphometric and fMRI study of the whole brain. Behav Brain Res. 2016;313:17-22.

17. Barnes MA, Caltabiano ML. The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22(1):177-184.

18. Mathieu J. What is orthorexia? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(10):1510-1512.

19. Catalina Zamora ML, Bote Bonaechea B, García Sánchez F, Ríos Rial B. Orthorexia nervosa. A new eating behavior disorder? [in Spanish]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2005;33(1):66-68.

20. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, Yager J, Weintraub P. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

21. Park SW, Kim JY, Go GJ, Jeon ES, Pyo HJ, Kwon YJ. Orthorexia nervosa with hyponatremia, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastimum, pneumothorax, and pancytopenia. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2011;9(1):32-37.

22. Mogallapu RNG, Aynampudi AR, Scarff JR, Lippmann S. Orthorexia nervosa. The Kentucky Psychiatrist. 2012;22(3):3-6.

Interprofessional Education in Patient Aligned Care Team Primary Care-Mental Health Integration

Over the past 10 years, the VHA has been a national leader in primary care-mental health integration (PC-MHI) within patient aligned care teams (PACTs).1,2 Studies of the PC-MHI collaborative care model consistently have shown increased access to MH services, higher levels of MH treatment engagement, improved MH treatment outcomes, and high patient and provider satisfaction.3-7 Primary care-mental health integration relies heavily on interprofessional team-based practice with providers from diverse educational and clinical backgrounds who work together to deliver integrated mental and behavioral health services within PACTs. This model requires a unique blending of professional cultures and communication and practice styles.

To sustain PC-MHI in PACT, health care professionals (HCPs) must be well trained to work effectively in interprofessional teams. Across health care organizations, training in collaborative interprofessional team-based practice has been identified as an important and challenging task.8-11

Integrating educational experiences among different HCP learners is an approach to developing competency in interprofessional collaboration early in training. The World Health Organization defined interprofessional education (IPE) as occurring “when students from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.”9 Fundamental to this definition is the belief that interaction among learners from different disciplines during their training develops competency in subsequent effective collaborative practice. Studies of IPE in MH professional training have found that prelicensure IPE contributes to increased knowledge of roles and responsibilities of different disciplines, improved interprofessional communication and attitudes, and increased willingness to work in teams.12-17

Interprofessional education is a valuable training model, but developing interprofessional learning experiences in a system of diverse and often siloed training programs is difficult. More information about design and implementation of IPE training experiences is needed, particularly in outpatient settings in which integration of traditionally separate discipline-specific care is central to the health care mission. The VA PACT PC-MHI is a strong team-based care model that represents a unique opportunity for training across disciplines in interprofessional collaborative care.

To find innovative approaches to meeting the need for IPE in PACT PC-MHI, the authors developed a new IPE program in PC-MHI at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital (WSMMVH) in Madison, Wisconsin. This article reviews the development, implementation, and first-year evaluation of the training program and discusses the challenges and the IPE areas in need of improvement in PACT PC-MHI.

Methods

In 2012, the VHA launched phase 1 of the Mental Health Education Expansion Initiative (MHEEI), a collaboration of the Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), VHA Mental Health Services (VHA-MHS), and the Office of Mental Health Operations (OMHO).18 The MHEEI was intended to “increase expertise in critical areas of need, expand the recruitment pipeline of well-trained, highly qualified health care providers in behavioral and mental health disciplines, and promote the utilization of interprofessional team-based care.”18 In response, WSMMVH organized a planning committee and submitted a funding request through the section of MHEEI called PACT With Integrated Behavioral Health Providers. The planning committee included training program directors and staff from psychiatry, pharmacy, social work, psychology, and primary care. The authors received funding for trainees in psychiatry (postgraduate year 4 [PGY-4]), pharmacy/MH residency (PGY-2), pharmacy/ambulatory care (PGY-1), and social work (interns).

Curriculum Development

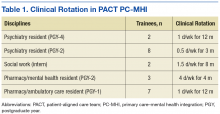

The planning committee met regularly for 6 months to develop the organization, learning objectives, educational strategies, and implementation plan for the IPE program. The program was organized as a 4- to 12-month clinical rotation with the PC-MHI team in PACT, combined with 12 months of protected weekly IPE time (Table 1).

Learning Objectives

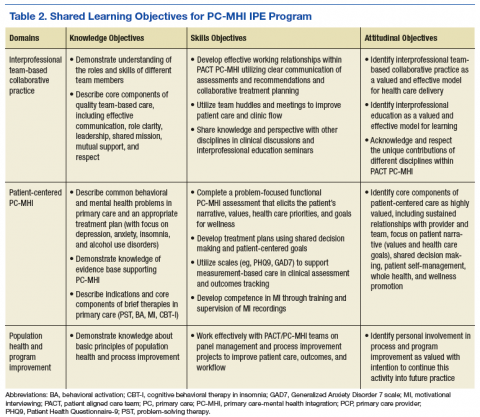

To better understand the educational needs and foci for learning objectives, the interprofessional planning committee reviewed guidelines on training in integrated care and collaborative team-based practice.2,9,10,19-21 These guidelines were compared with existing training opportunities for each discipline to identify training gaps and needs.

Learning objectives were organized into 3 domains: patient-centered PC-MHI, collaborative team-based practice, and population health and program improvement. Table 2 outlines the shared learning objectives linked to each domain that were common to the psychiatry, pharmacy, and social work disciplines. Although many of the learning objectives were shared among all disciplines, each trainee also had discipline-specific clinical activities and learning objectives. Psychiatry and pharmacy residents focused on primary care psychiatric medication consultation and care management for antidepressant medication starts. Social work interns focused on psychosocial and functional assessment and brief problem-focused psychotherapies. Learning objectives were met through direct veteran care in the primary care clinic as part of the PACT PC-MHI team and through interprofessional learning activities during protected weekly education time.

Implementation

Critical stakeholders in implementing the IPE program involved themselves early and throughout the planning process. Stakeholders included VAMC leadership, primary care and MH service line chiefs and clinic managers, training program directors, and PACT staff. Planning committee members gave presentations on the IPE program at MH service line and PACT meetings in the 2 months before program initiation in order to orient staff to learning objectives, program structure, and impact on PACT PC-MHI operations. Throughout the first year, the planning committee continued to meet every 2 weeks to review progress, solve implementation problems, and revise learning objectives and activities.

Trainee Clinical Activities

A wide range of educational strategies were planned to meet learning objectives across the 3 domains. There was strong emphasis on experiential learning through daily PACT and PC-MHI clinical work, team huddles and meetings, and trainee-led program improvement projects.

Psychiatry and PGY-2 pharmacy/MH residents focused on direct and indirect medication consultation and problem-focused assessments. Their clinical activities included PC-MHI medication evaluation and follow-up visits; chart reviews and e-consults for medication recommendations to PACT providers; reviews of care management data and consultations on veterans enrolled in depression and anxiety care management; “curbside consultations” for providers in PACT huddles and meetings and throughout the clinic day; and “warm handoffs,” same-day initial PC-MHI problem-focused assessments performed on PACT provider request. The residents were part of a pool of staff and trainees who performed these assessments.

PGY-1 pharmacy residents made care management phone calls for antidepressant trials for depression and anxiety. These residents were trained in motivational interviewing (MI). They applied their MI skills during care management calls focused on medication adherence and behavioral interventions for depression (eg, exercise, planning pleasurable activity) and during other clinical rotations, including tobacco cessation and medication management for diabetes and hypertension. Particularly challenging veteran cases from these clinics were cosupervised with medication management and PC-MHIstaff for added consultation on engagement, behavior change, and treatment plan adherence.

Social work interns completed initial PC-MHI psychosocial and functional assessments by phone and directly by same-day warm handoffs from PACT staff. The PC-MHI therapies they provided included problem-solving therapy, behavioral activation, stress management based on cognitive behavioral therapy, and brief alcohol interventions.

Group IPE Activities

All trainees had a weekly protected block of 3 hours during which they came together for group IPE that was designed to elicit active participation; facilitate interprofessional communication; and develop an understanding of and respect for the knowledge, culture, and practice style of the different disciplines.

Trainees participated in a Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI) workshop focused on developing a better understanding of individual differences in thinking and problem solving, with the goal of improving communication and learning within teams.22 In a seminar series on professionalism and boundaries in health care, trainees from each discipline gave a presentation on the traditional structure and content of their discipline’s training and discussed similarities and differences in their disciplines’ professional oaths, codes of ethics, and boundary guidelines.

Motivational interviewing training was conducted early in the year so trainees would be prepared to apply MI skills in their daily PACT PC-MHI clinical work. Motivational inteviewing is a patient-centered approach to engaging patients in health promoting behavior change. It is defined as a “directive, client-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence.”23

Trainees recorded MI sessions with at least 2 live-patient visits and at least 2 simulated-patient interviews (with staff serving as patient actors). The structure of MI training and supervision was deliberately designed to facilitate interprofessional communication and learning. In accord with a group supervision model for MI recorded reviews, the trainees presented their tapes to the entire learning group in the presence of a facilitating supervisor. Trainees had the opportunity to observe different interview styles and exchange feedback within a peer group of interprofessional learners.

Seminars were focused on core PC-MHI clinical content (eg, depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorders) and organized around case-based learning. Trainees divided into small teams in which representatives of each discipline offered their perspective on how to approach planning patient assessment and treatment. During the seminars, the authors engaged trainees as teachers and leaders whenever possible. All trainees presented on a topic in which they had some discipline expertise. For example, social work interns led a seminar on support and social services for victims of domestic violence, and PGY-1 pharmacy/ambulatory care residents led seminars and a panel management project focused on diabetes and depression.

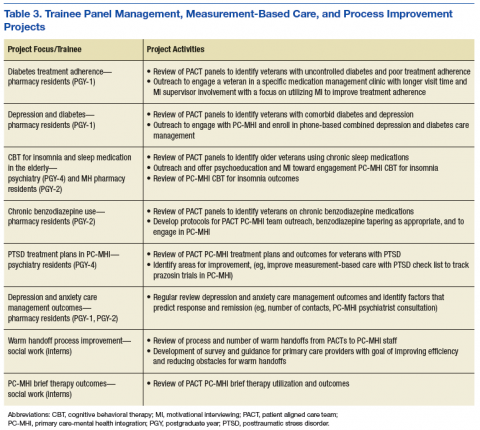

Trainees participated in several PACT PC-MHI projects focused on population- and measurement-based care, panel management, and program improvement (Table 3). Protected IPE time was used to teach trainees about population health principles and different tools for process improvement (eg, Vision-Analysis Team-Aim-Map-Measure-Change-Sustain) and provide a forum in which trainees could share their work with one another.

Evaluations

Several tools were used for trainee and program evaluations. Clinical skills were evaluated during daily supervision. Trainees began the year with PC-MHI staff directly observing all their clinical contacts with veterans. Staff evaluated and offered feedback on trainee clinical interviewing and on assessment and treatment planning skills. Once they were assessed to be ready to see veterans on their own, trainees were advanced by staff to “drop-in” direct supervision: Toward the end of a veteran’s visit, a staff preceptor entered the room to review relevant clinical findings, assessment and finalized treatment planning with the trainee and veteran. When appropriate for trainee competence level, clinical contacts were indirectly supervised: Trainees discussed their assessment and treatment plan with a staff supervisor at the end of the day.

Motivational interviewing recordings were reviewed during group supervision. To objectively evaluate MI skills, supervisors who were VA-certified in MI used the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) coding tool to review and code both the live- and simulated-patient recordings.24 The MITI coding involves quantitative and qualitative analysis using standardized coding items.

Quantitative items included percentage of open-ended questions (Proficiency: 50%; competency: 70%); percentage of reflections considered complex reflections, or reflective statements adding substantial meaning or emphasis and conveying a deeper or more complex picture of what patients say (Proficiency: 40%; competency: 50%); reflection-to-question ratio (Proficiency: 1:1; competency: 2:1); and percentage of MI-adherent provider statements (Proficiency: 90%; competency: 100%).

Qualitative coding items were a global rating of therapist “empathy,” which evaluated the extent to which the trainee understood or made an effort to grasp the patient’s perspective, and “MI spirit.” This coding intended to capture the overall competence of the trainee in emphasizing collaboration, patient autonomy, and evocation of the patient experience (Proficiency score: 5; competency score: 6).

The PC-MHI teaching staff met midyear and end of year as a team to complete trainee evaluations focused on the 3 areas of learning objectives: patient-centered PC-MHI, collaborative team-based practice, and population health and program improvement. Patient-centered PC-MHI involves direct observation and supervision of trainee clinical contacts with veterans, including assessment and treatment planning, clinical documentation, and review of live- and simulated-patient MI recordings. Collaborative team-based practice involves review of trainee participation in day-to-day teamwork, huddles, team meetings, and IPE activities. Population health and program improvement involves review of trainee work on a panel measurement-based care management or program improvement project. In each learning objectives area, trainees were rated on a 3-point scale: needs improvement (1); satisfactory (2); achieved (3). Core knowledge about PC-MHI evidence base, structure, and clinical topics was assessed with case-based written examination at midyear and end of year.

Surveys and qualitative interviews were used to assess trainee perceptions about the IPE program. A midyear and end-of-year survey assessed trainee satisfaction and perceived efficacy of the IPE training program in meeting core learning objectives. A midyear survey designed by pharmacy residents as part of their program improvement project evaluated attitudes around interprofessional learning and team practice. Trainees met individually with the PC-MHI IPE director at midyear and end of year to gather qualitative feedback on the IPE program.

Outcomes

All trainees advanced to the expected level of supervision for clinical contacts (drop-in or indirect clinical supervision). Over the year, there was significant improvement in trainees’ MI skills as measured by MITI coding of at least 2 live-patient or 2 simulated-patient recordings (Figures 1A and 1B). By end of year, most trainees had reached proficiency or competency in several MITI coded items: percentage of open-ended questions (4/12 proficient, 8/12 competent), percentage of complex reflections (2/12 less than proficient, 3/12 proficient, 7/12 competent), MI adherence (1/12 proficient, 11/12 competent), global empathy rating (2/12 proficient, 10/12 competent), and global MI spirit rating (12/12 competent). Average reflection-to-question ratio for the trainee group increased from 0.63 to 0.96 from midyear to end of year, but only 3 of 12 trainees reached the proficiency level of a 1:1 ratio, and no trainee reached the competency level of a 2:1 ratio.

According to the PC-MHI team’s midyear evaluation, most trainees were already making satisfactory progress in the 3 domains of learning objectives for the training program. At end of year, 13 of 14 trainees were assessed as competent in all 3 domains (Figures 2A and B). All trainees passed the midyear and end-of-year written examinations with overall high scores (average score, 82%) demonstrating acquisition of core PC-MHI clinical knowledge.

Trainee evaluations of the IPE program were overall highly favorable at both midyear and at end of year. Trainees rated the program effective or extremely effective in developing their skills in patient-centered care, interprofessional communication, and collaborative team-based practice. They also rated the program highly effective in preparing them to use team-based practice skills in other settings. On a midyear survey, trainees moderately to strongly agreed with several positive beliefs and attitudes about team-based care.

In qualitative interviews at program completion, trainees across disciplines rated the MI training with group supervision as one of their most valuable interprofessional learning experiences. Other highly valued training experiences were PACT PC-MHI panel management projects, team-based clinical case reviews, and cross-disciplinary supervision.

Discussion

This article describes the successful development and implementation of a VA-based IPE program in PACT PC-MHI. Interprofessional clinical training and educational experiences were highly valued, and trainees identified positive attitudes and improved skills related to team-based care. These findings support previous findings that IPE is associated with high satisfaction and positive attitudes toward team-based collaborative practice.12-17 Program implementation presented several challenges: nonsynchronous academic calendars and rotation schedules, cross-disciplinary supervision regulations, variations in clinical and supervisory requirements for accreditation standards, the traditional health care hierarchy, and measurement of the impact of IPE experiences.11,25,26

Rotation schedules and academic calendars varied across the psychiatry, pharmacy, and social work home programs. Organizing different trainee rotation schedules was a significant challenge. Collaboration with training directors and support staff was crucial in planning rotations that offered a longitudinal training experience in PACT PC-MHI. Given the participants’ different starting dates, protected IPE time early in the calendar year was focused on developing clinical skills specific to the pharmacy and psychiatry trainees who would be starting in July, and IPE activities that required the presence of all trainee disciplines (eg, MI training, HBDI) were planned for after the September start of the social work interns.

Cross-disciplinary supervision was highly valued by trainees because it offered exposure to the disciplines’ different communication styles and approaches to clinical assessment and decision making. Throughout the year, however, trainees encountered several obstacles to cross-disciplinary supervision, with respect to coding/billing and home program supervisory policies. The authors worked closely with the VA administration and each training program to develop and revise supervising policies and procedures to meet the necessary administrative and program supervisory requirements for accreditation standards.

In some cases, this work resulted in dual supervision by a preceptor of the same discipline (to meet requirements for coding/billing and home program supervision) and clinical supervision by a preceptor of a different discipline (eg, in team meetings or in clinical case reviews during protected IPE time). Preceptors from each discipline met regularly to discuss challenges in cross-disciplinary supervision, review scope-of-practice issues, share information on discipline-specific training, and revise supervisory procedures.

Interprofessional education activities during weekly protected time were designed to improve collaboration and to challenge trainees to examine traditional hierarchical roles and patterns of communication in health care. An emphasis on case-based learning in small groups encouraged trainees to share perspectives on their discipline-specific approach to assessment and treatment planning. Motivational interviewing training, one of the IPE experiences most valued by trainees and staff, created the opportunity for a truly shared learning environment, as trainees largely started at about the same skill level despite having different educational backgrounds. Group supervision of MI recordings offered trainees the opportunity to learn from each other and develop comfort in offering and receiving interprofessional constructive feedback.

Limitations

There were considerable methodologic limitations in the authors’ efforts to evaluate the impact of this training program on trainee attitudes and skills in collaborative team-based practice. Although trainee surveys revealed highly positive attitudes and beliefs about team-based care as well as perceived competence in collaborative practice, these were not validated surveys, and changes could not be accurately measured over time (trainees were not assessed at baseline). Trainees also were involved in other clinical teams within the VA during the year, and it is difficult to assess the specific impact of their PC-MHI IPE experiences. The PC-MHI staff evaluations of trainee competence in collaborative team-based practice were largely observational and potentially vulnerable to biases, as the staff evaluating trainee competence also were part of the IPE program planning process and invested in its success.

To address these limitations in the future, the authors will use better assessment tools at baseline and end of year to more effectively evaluate the impact of the training program on teamwork skills as well changes in attitudes and beliefs about interprofessional learning and teamwork. The Attitudes Toward Interprofessional Health Care Teams Scale and the Perceptions of Effective Interpersonal Teams Scale should be considered as they have published reliability and validity.27,28 The authors could improve the reliability and depth of trainee evaluations with use of a “360-degree evaluation” model for trainee evaluations that includes other PACT members (beyond PC-MHI staff) as well as veterans.

Assessment of MI skills and competency was limited by use of both live- and simulated-patient recordings. Simulation is a valuable learning tool but often does not accurately represent actual clinical situations and challenges. To appropriately assess MI competence, future MI training should emphasize live-patient recordings over simulated-patient visits. Furthermore, whereas trainees reached competency in several MI coding items, none reached competency in the reflection-to-question ratio, and only about half reached competency in percentage of complex reflections. Future MI training will need to focus on further development of reflection skills.

Trainee intentions to remain involved in program improvement and collaborative team-based care in future professional work were core attitudinal learning objectives, but neither was adequately assessed in end-of-year surveys. Ideally, future evaluations will assess subjective trainee intentions and goals around team-based work and objectively measure future professional choices and activities. For example, it would be interesting to determine whether trainees who participated in this program will choose to practice in an interprofessional team-based model or participate in program improvement activities.

Last, the absence of psychology interns was considered a weakness in the learning environment, resulting in a relatively “prescriber-heavy” balance in discipline perspectives for IPE-focused case discussions and other training. Furthermore, the discipline representation in the IPE program did not exemplify the typical PC-MHI team in most VA clinic settings and community practices in which psychology has a strong presence. Adding psychology trainees was an important goal for the IPE program leadership. In 2015, WSMMVH was awarded additional funding for a PACT PC-MHI predoctoral psychology intern through the phase 4 MHEEI. The PC-MHI track psychology intern joined the IPE program in the 2016-2017 training year.

Conclusion

There is broad consensus that interprofessional team-based practice is crucial for providers in the VA and all health care systems. Primary care-mental health integration is an area of VA care in which interprofessional collaboration is uniquely important to implementation and sustainability of the model. Interprofessional education is an effective approach for preparing HCPs for team-based practice, but implementation is challenging. Several factors crucially contributed to the successful implementation of this program: collaboration of the interprofessional planning team with representation from key stakeholders in different departments and training programs; a well-established PACT PC-MHI team with experience in collaborative team-based care; a curriculum structure that emphasized experiential educational strategies designed to promote interprofessional learning and communication; VA leadership support at the national level (MHEEI funding) and local level; and PACT PC-MHI clinical staff committed to teaching and to the IPE mission.

1. Wray LO, Szymanski BR, Kearney LK, McCarthy JF. Implementation of primary care-mental health integration services in the Veterans Health Administration: program activity and associations with engagement in specialty mental health services. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(1):105-116.

2. Kearney LK, Post EP, Pomerantz AS, Zeiss AM. Applying the interprofessional patient aligned care team in the Department of Veterans Affairs: transforming primary care. Am Psychol. 2014;69(4):399-408.

3. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of loner-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314-2321.

4. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al; IMPACT (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment) Investigators. Collaborative care management in late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized control trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836-2845.

5. Katon W, Unützer J. Consultation psychiatry in the medical home and accountable care organizations: achieving the triple aim. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;3(4):305-310.

6. Bruce ML, Tenhave TR, Reynolds CF III, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081-1091.

7. Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF III , Bruce ML, et al; PROSPECT Group. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):882-890.

8. Cox M, Cuff P, Brandt B, Reeves S, Zierler B. Measuring the impact of interprofessional education on collaborative practice and patient outcomes. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(1):1-3.

9. World Health Organization, Study Group on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

10. Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011.

11. Blue AV, Mitcham M, Smith T, Raymond J, Greenburg R. Changing the future of health professions: embedding interprofessional education within an academic health center. Acad Med. 2010;85(8):1290-1295.

12. Priest HM, Roberts P, Dent H, Blincoe C, Lawton D, Armstrong C. Interprofessional education and working in mental health: in search of the evidence base. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(4):474-485.

13. Reeves S. A systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education on staff involved in the care of adults with mental health problems. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8(6):533-542.

14. Carpenter J, Barnes D, Dickinson C, Wooff D. Outcomes of interprofessional education for community mental health services in England: the longitudinal evaluation of a postgraduate programme. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(2):145-161.

15. Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 9. Med Teach. 2007;29(8):735-751.

16. Pauzé E, Reeves S. Examining the effects of interprofessional education on mental health providers: findings from an updated systematic review. J Ment Health. 2010;19(3):258-271.

17. Curran V, Heath O, Adey T, et al. An approach to integrating interprofessional education in collaborative mental health care. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(2):91-95.