User login

Perinatal psychiatry: 5 key principles

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

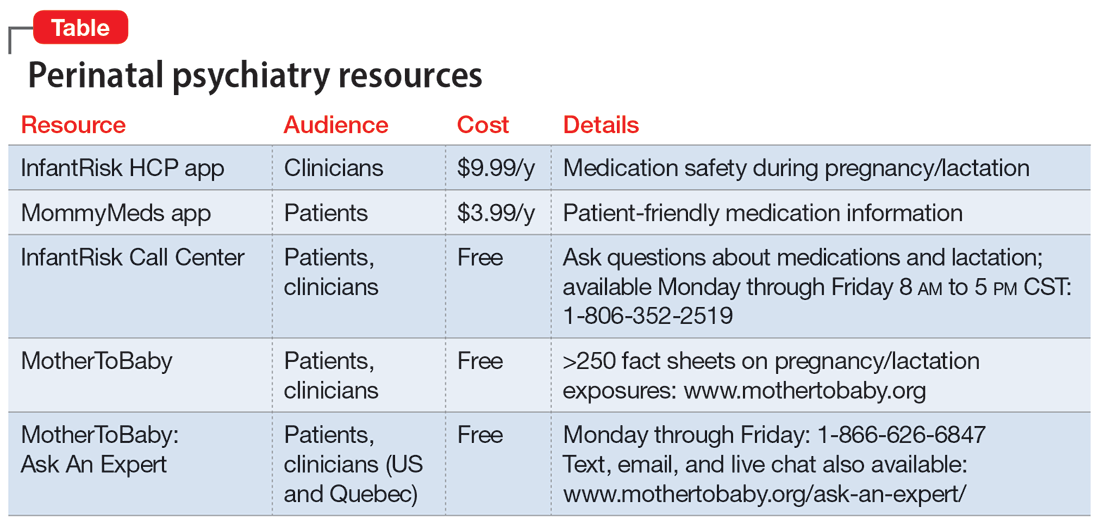

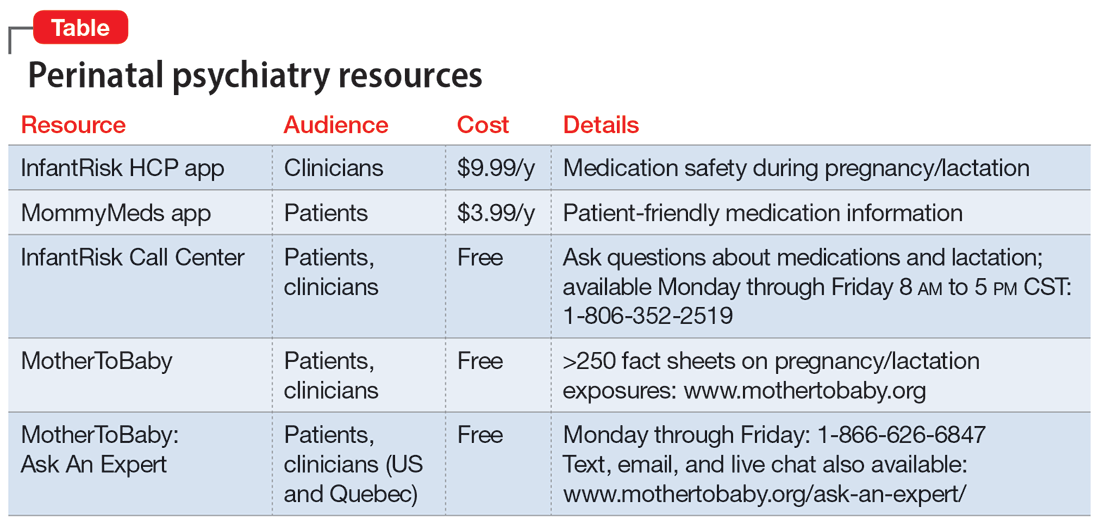

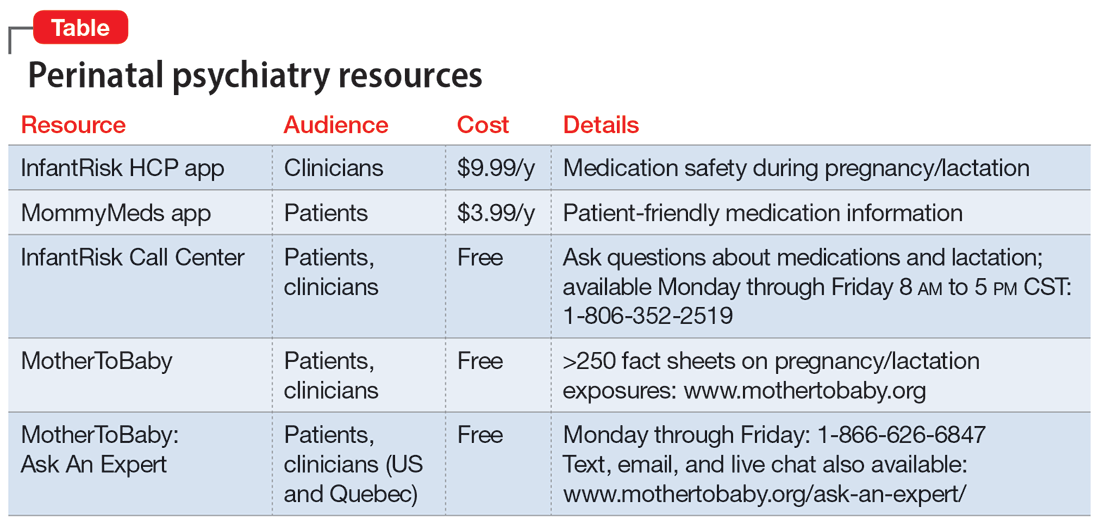

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

Diagnosing borderline personality disorder: Avoid these pitfalls

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, reduced quality of life, increased use of health care services, and excess mortality.1 Unfortunately, this disorder is often underrecognized and underdiagnosed, and patients with BPD may not receive an accurate diagnosis for years after first seeking treatment.1 Problems in diagnosing BPD include:

Stigma. Some patients may view the term “borderline” as stigmatizing, as if we are calling these patients borderline human beings. One of the symptoms of BPD is a “markedly and persistently unstable self-image.”2 Such patients do not need a stigmatizing label to worsen their self-image.

Terminology. The word borderline may also imply relatively mild psychiatric symptoms. However, “borderline personality disorder” does not refer to a mild personality disorder. DSM-5 describes potential BPD symptoms as “intense,” “marked,” or “severe,” and 1 of the symptoms is suicidal behavior.2

Symptoms. To meet the criteria for a BPD diagnosis, a patient must exhibit ≥5 of 9 severe symptoms2:

- frantic efforts to avoid abandonment

- unstable and intense interpersonal relationships

- unstable self-image

- impulsivity in ≥2 areas that are potentially self-damaging

- suicidal behavior

- affective instability

- chronic feelings of emptiness

- inappropriate anger

- transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms.

Asking about all 9 of these criteria and their severity is not part of a routine psychiatric evaluation. A patient might not volunteer any of this information because they are concerned about potential stigma. Additionally, perhaps most of the general population has had a “BPD-like” symptom at least once during their lives. This symptom might not have been severe enough to qualify as a true BPD symptom. Clinicians might have difficulty discerning BPD-like symptoms from true BPD symptoms.

Comorbidities. Many patients with BPD also have a comorbid mood disorder or substance use disorder.1,3 Clinicians might focus on a comorbid diagnosis and not recognize BPD.

Stress. BPD symptoms may become more severe when the patient faces a stressful situation. The BPD symptoms might seem more severe than the stress would warrant.2 However, clinicians might blame the BPD symptoms solely on stress and not acknowledge the underlying BPD diagnosis.

Awareness of these factors can help clinicians keep BPD in the differential diagnosis when conducting a psychiatric evaluation, thus reducing the chances of overlooking this serious disorder.

1. Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:663-666.

3. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008:69(4)533-545.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, reduced quality of life, increased use of health care services, and excess mortality.1 Unfortunately, this disorder is often underrecognized and underdiagnosed, and patients with BPD may not receive an accurate diagnosis for years after first seeking treatment.1 Problems in diagnosing BPD include:

Stigma. Some patients may view the term “borderline” as stigmatizing, as if we are calling these patients borderline human beings. One of the symptoms of BPD is a “markedly and persistently unstable self-image.”2 Such patients do not need a stigmatizing label to worsen their self-image.

Terminology. The word borderline may also imply relatively mild psychiatric symptoms. However, “borderline personality disorder” does not refer to a mild personality disorder. DSM-5 describes potential BPD symptoms as “intense,” “marked,” or “severe,” and 1 of the symptoms is suicidal behavior.2

Symptoms. To meet the criteria for a BPD diagnosis, a patient must exhibit ≥5 of 9 severe symptoms2:

- frantic efforts to avoid abandonment

- unstable and intense interpersonal relationships

- unstable self-image

- impulsivity in ≥2 areas that are potentially self-damaging

- suicidal behavior

- affective instability

- chronic feelings of emptiness

- inappropriate anger

- transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms.

Asking about all 9 of these criteria and their severity is not part of a routine psychiatric evaluation. A patient might not volunteer any of this information because they are concerned about potential stigma. Additionally, perhaps most of the general population has had a “BPD-like” symptom at least once during their lives. This symptom might not have been severe enough to qualify as a true BPD symptom. Clinicians might have difficulty discerning BPD-like symptoms from true BPD symptoms.

Comorbidities. Many patients with BPD also have a comorbid mood disorder or substance use disorder.1,3 Clinicians might focus on a comorbid diagnosis and not recognize BPD.

Stress. BPD symptoms may become more severe when the patient faces a stressful situation. The BPD symptoms might seem more severe than the stress would warrant.2 However, clinicians might blame the BPD symptoms solely on stress and not acknowledge the underlying BPD diagnosis.

Awareness of these factors can help clinicians keep BPD in the differential diagnosis when conducting a psychiatric evaluation, thus reducing the chances of overlooking this serious disorder.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, reduced quality of life, increased use of health care services, and excess mortality.1 Unfortunately, this disorder is often underrecognized and underdiagnosed, and patients with BPD may not receive an accurate diagnosis for years after first seeking treatment.1 Problems in diagnosing BPD include:

Stigma. Some patients may view the term “borderline” as stigmatizing, as if we are calling these patients borderline human beings. One of the symptoms of BPD is a “markedly and persistently unstable self-image.”2 Such patients do not need a stigmatizing label to worsen their self-image.

Terminology. The word borderline may also imply relatively mild psychiatric symptoms. However, “borderline personality disorder” does not refer to a mild personality disorder. DSM-5 describes potential BPD symptoms as “intense,” “marked,” or “severe,” and 1 of the symptoms is suicidal behavior.2

Symptoms. To meet the criteria for a BPD diagnosis, a patient must exhibit ≥5 of 9 severe symptoms2:

- frantic efforts to avoid abandonment

- unstable and intense interpersonal relationships

- unstable self-image

- impulsivity in ≥2 areas that are potentially self-damaging

- suicidal behavior

- affective instability

- chronic feelings of emptiness

- inappropriate anger

- transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms.

Asking about all 9 of these criteria and their severity is not part of a routine psychiatric evaluation. A patient might not volunteer any of this information because they are concerned about potential stigma. Additionally, perhaps most of the general population has had a “BPD-like” symptom at least once during their lives. This symptom might not have been severe enough to qualify as a true BPD symptom. Clinicians might have difficulty discerning BPD-like symptoms from true BPD symptoms.

Comorbidities. Many patients with BPD also have a comorbid mood disorder or substance use disorder.1,3 Clinicians might focus on a comorbid diagnosis and not recognize BPD.

Stress. BPD symptoms may become more severe when the patient faces a stressful situation. The BPD symptoms might seem more severe than the stress would warrant.2 However, clinicians might blame the BPD symptoms solely on stress and not acknowledge the underlying BPD diagnosis.

Awareness of these factors can help clinicians keep BPD in the differential diagnosis when conducting a psychiatric evaluation, thus reducing the chances of overlooking this serious disorder.

1. Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:663-666.

3. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008:69(4)533-545.

1. Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:663-666.

3. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008:69(4)533-545.

From smiling to smizing: Assessing the affect of a patient wearing a mask

Although the guidelines for masking in hospitals and other health care settings have been revised and face masks are no longer mandatory, it is important to note that some patients and clinicians will choose to continue wearing masks for various personal or clinical reasons. While effective in reducing transmission of the coronavirus, masks have created challenges in assessing patients’ affective states, which impacts the accuracy of diagnosis and treatment. This article discusses strategies for assessing affect in patients wearing face masks.

How masks complicate assessing affect

One obvious challenge masks present is they prevent clinicians from seeing their patients’ facial expressions. Face masks cover the mouth, nose, and cheeks, all of which are involved in communicating emotions. As a result, clinicians may miss important cues that could inform their assessment of a patient’s affect. For example, when a masked patient is smiling, it is difficult to determine whether their smile is genuine or forced. A study that evaluated the interpretation of 6 emotions (angry, disgusted, fearful, happy, neutral, and sad) in masked patients found that emotion recognition was significantly reduced for all emotions except for fearful and neutral faces.1

Another challenge is the potential for misinterpretation. Health care professionals may rely more heavily on nonverbal cues, such as body language, to interpret a patient’s affect. However, these cues can be influenced by other factors, such as cultural differences and individual variations in communication style. Culture is a key component in assessing nonverbal emotion reading cues.2

Strategies to overcome these challenges

There are several strategies clinicians can use to overcome the difficulties of assessing affect while a patient is wearing a mask:

Focus on other nonverbal cues, such as a patient’s posture and hand gestures. Verbal cues—such as tone of voice, choice of words, and voice inflection—can also provide valuable insights. For example, a patient who speaks in a hesitant or monotone voice may be experiencing anxiety or depression. Clinicians can ask open-ended questions, encouraging patients to expand on their emotions and provide further information about their affect.

Maintain eye contact. Eye contact is an essential component of nonverbal communication. The eyes are “the window of the soul” and can convey various emotions including happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, trust, interest, and empathy. Maintaining eye contact is crucial for building positive relationships with patients, and learning to smile with your eyes (smize) can help build rapport.

Take advantage of technology. Clinicians can leverage telemedicine to assess affect. Telemedicine platforms, which have become increasingly popular during the COVID-19 pandemic, allow clinicians to monitor patients remotely and observe nonverbal cues. Virtual reality technology can also help by documenting physiological responses such as heart rate and skin conductance.

Use standardized assessment tools, as these instruments can aid in assessing affect. For example, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale are standardized questionnaires assessing depression and anxiety, respectively. Administering these tools to patients wearing a face mask can provide information about their affective state.

1. Carbon CC. Wearing face masks strongly confuses counterparts in reading emotions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:566886. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566886

2. Yuki M, Maddux WW, Masuda T. Are the windows to the soul the same in the East and West? Cultural differences in using the eyes and mouth as cues to recognize emotions in Japan and the United States. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43(2):303-311.

Although the guidelines for masking in hospitals and other health care settings have been revised and face masks are no longer mandatory, it is important to note that some patients and clinicians will choose to continue wearing masks for various personal or clinical reasons. While effective in reducing transmission of the coronavirus, masks have created challenges in assessing patients’ affective states, which impacts the accuracy of diagnosis and treatment. This article discusses strategies for assessing affect in patients wearing face masks.

How masks complicate assessing affect

One obvious challenge masks present is they prevent clinicians from seeing their patients’ facial expressions. Face masks cover the mouth, nose, and cheeks, all of which are involved in communicating emotions. As a result, clinicians may miss important cues that could inform their assessment of a patient’s affect. For example, when a masked patient is smiling, it is difficult to determine whether their smile is genuine or forced. A study that evaluated the interpretation of 6 emotions (angry, disgusted, fearful, happy, neutral, and sad) in masked patients found that emotion recognition was significantly reduced for all emotions except for fearful and neutral faces.1

Another challenge is the potential for misinterpretation. Health care professionals may rely more heavily on nonverbal cues, such as body language, to interpret a patient’s affect. However, these cues can be influenced by other factors, such as cultural differences and individual variations in communication style. Culture is a key component in assessing nonverbal emotion reading cues.2

Strategies to overcome these challenges

There are several strategies clinicians can use to overcome the difficulties of assessing affect while a patient is wearing a mask:

Focus on other nonverbal cues, such as a patient’s posture and hand gestures. Verbal cues—such as tone of voice, choice of words, and voice inflection—can also provide valuable insights. For example, a patient who speaks in a hesitant or monotone voice may be experiencing anxiety or depression. Clinicians can ask open-ended questions, encouraging patients to expand on their emotions and provide further information about their affect.

Maintain eye contact. Eye contact is an essential component of nonverbal communication. The eyes are “the window of the soul” and can convey various emotions including happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, trust, interest, and empathy. Maintaining eye contact is crucial for building positive relationships with patients, and learning to smile with your eyes (smize) can help build rapport.

Take advantage of technology. Clinicians can leverage telemedicine to assess affect. Telemedicine platforms, which have become increasingly popular during the COVID-19 pandemic, allow clinicians to monitor patients remotely and observe nonverbal cues. Virtual reality technology can also help by documenting physiological responses such as heart rate and skin conductance.

Use standardized assessment tools, as these instruments can aid in assessing affect. For example, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale are standardized questionnaires assessing depression and anxiety, respectively. Administering these tools to patients wearing a face mask can provide information about their affective state.

Although the guidelines for masking in hospitals and other health care settings have been revised and face masks are no longer mandatory, it is important to note that some patients and clinicians will choose to continue wearing masks for various personal or clinical reasons. While effective in reducing transmission of the coronavirus, masks have created challenges in assessing patients’ affective states, which impacts the accuracy of diagnosis and treatment. This article discusses strategies for assessing affect in patients wearing face masks.

How masks complicate assessing affect

One obvious challenge masks present is they prevent clinicians from seeing their patients’ facial expressions. Face masks cover the mouth, nose, and cheeks, all of which are involved in communicating emotions. As a result, clinicians may miss important cues that could inform their assessment of a patient’s affect. For example, when a masked patient is smiling, it is difficult to determine whether their smile is genuine or forced. A study that evaluated the interpretation of 6 emotions (angry, disgusted, fearful, happy, neutral, and sad) in masked patients found that emotion recognition was significantly reduced for all emotions except for fearful and neutral faces.1

Another challenge is the potential for misinterpretation. Health care professionals may rely more heavily on nonverbal cues, such as body language, to interpret a patient’s affect. However, these cues can be influenced by other factors, such as cultural differences and individual variations in communication style. Culture is a key component in assessing nonverbal emotion reading cues.2

Strategies to overcome these challenges

There are several strategies clinicians can use to overcome the difficulties of assessing affect while a patient is wearing a mask:

Focus on other nonverbal cues, such as a patient’s posture and hand gestures. Verbal cues—such as tone of voice, choice of words, and voice inflection—can also provide valuable insights. For example, a patient who speaks in a hesitant or monotone voice may be experiencing anxiety or depression. Clinicians can ask open-ended questions, encouraging patients to expand on their emotions and provide further information about their affect.

Maintain eye contact. Eye contact is an essential component of nonverbal communication. The eyes are “the window of the soul” and can convey various emotions including happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, trust, interest, and empathy. Maintaining eye contact is crucial for building positive relationships with patients, and learning to smile with your eyes (smize) can help build rapport.

Take advantage of technology. Clinicians can leverage telemedicine to assess affect. Telemedicine platforms, which have become increasingly popular during the COVID-19 pandemic, allow clinicians to monitor patients remotely and observe nonverbal cues. Virtual reality technology can also help by documenting physiological responses such as heart rate and skin conductance.

Use standardized assessment tools, as these instruments can aid in assessing affect. For example, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale are standardized questionnaires assessing depression and anxiety, respectively. Administering these tools to patients wearing a face mask can provide information about their affective state.

1. Carbon CC. Wearing face masks strongly confuses counterparts in reading emotions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:566886. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566886

2. Yuki M, Maddux WW, Masuda T. Are the windows to the soul the same in the East and West? Cultural differences in using the eyes and mouth as cues to recognize emotions in Japan and the United States. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43(2):303-311.

1. Carbon CC. Wearing face masks strongly confuses counterparts in reading emotions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:566886. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566886

2. Yuki M, Maddux WW, Masuda T. Are the windows to the soul the same in the East and West? Cultural differences in using the eyes and mouth as cues to recognize emotions in Japan and the United States. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43(2):303-311.

When a patient wants to stop taking their antipsychotic: Be ‘A SPORT’

For patients with schizophrenia, adherence to antipsychotic treatment reduces the rate of relapse of psychosis, lowers the rate of rehospitalization, and reduces the severity of illness.1 Despite this, patients may want to discontinue their medications for multiple reasons, including limited insight, adverse effects, or a negative attitude toward medication.1 Understanding a patient’s reason for wanting to discontinue their antipsychotic is critical to providing patient-centered care, building the therapeutic alliance, and offering potential solutions.

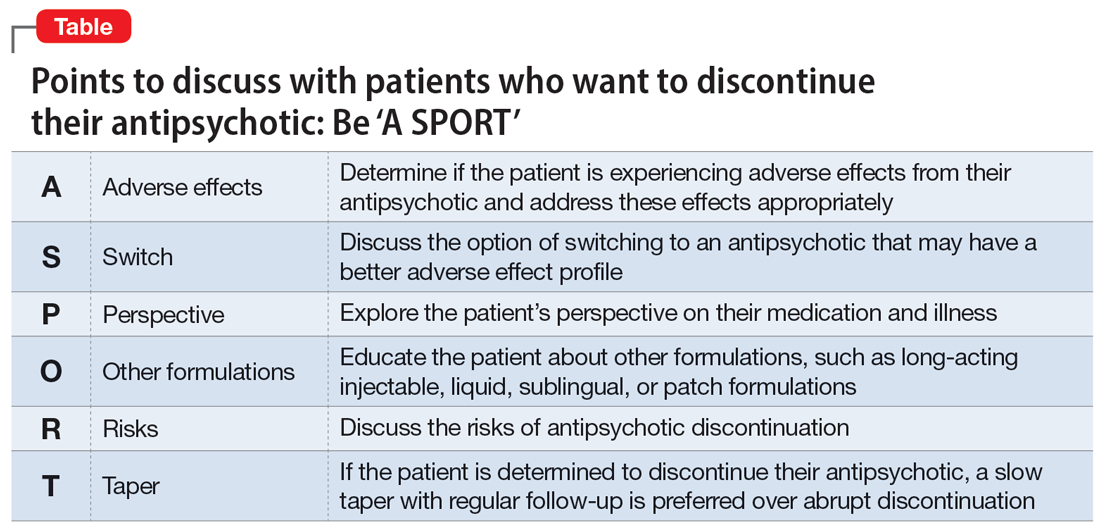

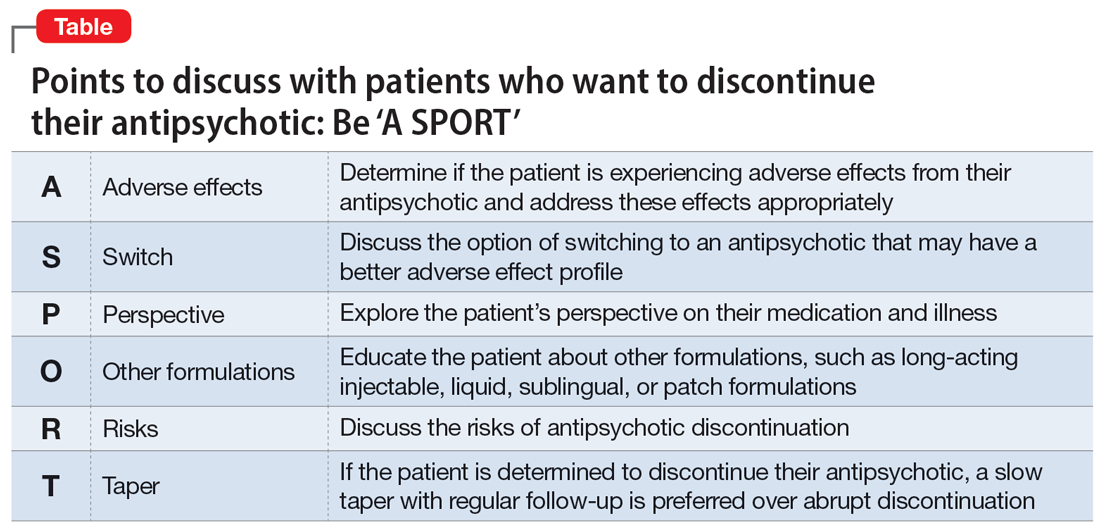

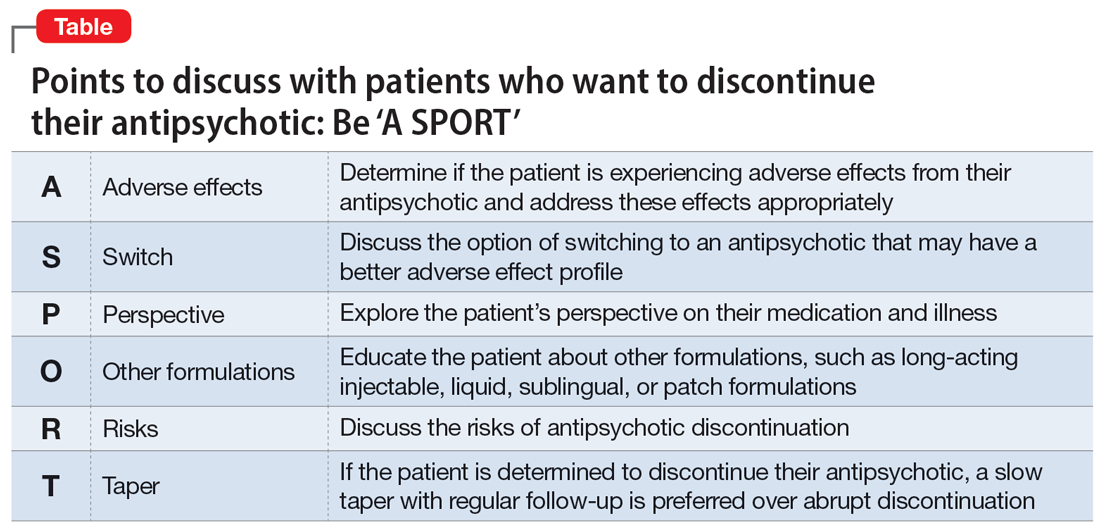

Clinicians can recall the mnemonic “A SPORT” (Table) to help ensure they have a thorough discussion with patients about the risks of discontinuation and potential solutions.

Points to cover

First, explore and acknowledge if a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, which may be causing them to have a negative attitude toward medications. If a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, offer interventions to mitigate those effects, such as adding an anticholinergic agent to address extrapyramidal symptoms. Decreasing the antipsychotic dosage might reduce the adverse effects burden while still optimizing the benefits from the antipsychotic. Additionally, switching to an alternate medication with a more favorable adverse effect profile may be an option. Whether the patient is experiencing intolerable adverse effects or just has a negative view of their prescribed antipsychotic, it is important to discuss switching medications.

Identifying patient attitudes and their general perspective toward their medication and illness is key. Similarly, a patient’s impaired insight into their mental illness has been associated with treatment discontinuation.2 A strong therapeutic alliance with your patient is of the utmost importance in these situations.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are useful clinical tools for patients who struggle to adhere to oral medications. Educating patients and caregivers about other formulations—namely LAIs—can help clarify any misconceptions they may have. One study found that patients who were prescribed oral antipsychotics thought LAIs would be painful, have worse adverse effects, and would not be beneficial in preventing relapse.3 In addition to LAIs, other formulations of antipsychotic medications, such as patches, sublingual tablets, or liquids, may be an option.

For patients to be able to provide informed consent regarding the decision to discontinue their antipsychotic, it is important to educate them about the risks of not taking an antipsychotic, such as an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and poor outcomes. Explain that patients with first-episode psychosis who achieve remission of symptoms while taking an antipsychotic can remain in remission with continued treatment, but there is a 5-fold increased risk of relapse when discontinuing an antipsychotic during first-episode psychosis.4

Lastly, despite discussing the risks and benefits, if a patient is determined to discontinue their antipsychotic, we recommend a slow taper of medication rather than abrupt discontinuation. Research has shown that more than one-half of patients who abruptly discontinue an antipsychotic experience withdrawal symptoms, including (but not limited to) nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches, as well as anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.5 These symptoms may occur within 4 weeks after discontinuation.5 While there are no clear guidelines on deprescribing antipsychotics, it is best to individualize the taper based on patient response. Family and caregiver involvement, close follow-up, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the tapering process.6

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherenc. 2017;11:449-468. doi:10.2147/PPA.S124658

2. Kim J, Ozzoude M, Nakajima S, et al. Insight and medication adherence in schizophrenia: an analysis of the CATIE trial. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107634. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.05.011

3. Sugawara N, Kudo S, Ishioka M, et al. Attitudes toward long-acting injectable antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:205-211. doi:10.2147/NDT.S188337

4. Winton-Brown TT, Elanjithara T, Power P, et al. Five-fold increased risk of relapse following breaks in antipsychotic treatment of first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:50-56. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.029

5. Brandt L, Bschor T, Henssler J, et al. Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569912. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569912

6. Gupta S, Cahill JD, Miller R. Deprescribing antipsychotics: a guide for clinicians. BJPsych Advances. 2018;24(5):295-302. doi:10.1192/bja.2018.2

For patients with schizophrenia, adherence to antipsychotic treatment reduces the rate of relapse of psychosis, lowers the rate of rehospitalization, and reduces the severity of illness.1 Despite this, patients may want to discontinue their medications for multiple reasons, including limited insight, adverse effects, or a negative attitude toward medication.1 Understanding a patient’s reason for wanting to discontinue their antipsychotic is critical to providing patient-centered care, building the therapeutic alliance, and offering potential solutions.

Clinicians can recall the mnemonic “A SPORT” (Table) to help ensure they have a thorough discussion with patients about the risks of discontinuation and potential solutions.

Points to cover

First, explore and acknowledge if a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, which may be causing them to have a negative attitude toward medications. If a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, offer interventions to mitigate those effects, such as adding an anticholinergic agent to address extrapyramidal symptoms. Decreasing the antipsychotic dosage might reduce the adverse effects burden while still optimizing the benefits from the antipsychotic. Additionally, switching to an alternate medication with a more favorable adverse effect profile may be an option. Whether the patient is experiencing intolerable adverse effects or just has a negative view of their prescribed antipsychotic, it is important to discuss switching medications.

Identifying patient attitudes and their general perspective toward their medication and illness is key. Similarly, a patient’s impaired insight into their mental illness has been associated with treatment discontinuation.2 A strong therapeutic alliance with your patient is of the utmost importance in these situations.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are useful clinical tools for patients who struggle to adhere to oral medications. Educating patients and caregivers about other formulations—namely LAIs—can help clarify any misconceptions they may have. One study found that patients who were prescribed oral antipsychotics thought LAIs would be painful, have worse adverse effects, and would not be beneficial in preventing relapse.3 In addition to LAIs, other formulations of antipsychotic medications, such as patches, sublingual tablets, or liquids, may be an option.

For patients to be able to provide informed consent regarding the decision to discontinue their antipsychotic, it is important to educate them about the risks of not taking an antipsychotic, such as an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and poor outcomes. Explain that patients with first-episode psychosis who achieve remission of symptoms while taking an antipsychotic can remain in remission with continued treatment, but there is a 5-fold increased risk of relapse when discontinuing an antipsychotic during first-episode psychosis.4

Lastly, despite discussing the risks and benefits, if a patient is determined to discontinue their antipsychotic, we recommend a slow taper of medication rather than abrupt discontinuation. Research has shown that more than one-half of patients who abruptly discontinue an antipsychotic experience withdrawal symptoms, including (but not limited to) nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches, as well as anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.5 These symptoms may occur within 4 weeks after discontinuation.5 While there are no clear guidelines on deprescribing antipsychotics, it is best to individualize the taper based on patient response. Family and caregiver involvement, close follow-up, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the tapering process.6

For patients with schizophrenia, adherence to antipsychotic treatment reduces the rate of relapse of psychosis, lowers the rate of rehospitalization, and reduces the severity of illness.1 Despite this, patients may want to discontinue their medications for multiple reasons, including limited insight, adverse effects, or a negative attitude toward medication.1 Understanding a patient’s reason for wanting to discontinue their antipsychotic is critical to providing patient-centered care, building the therapeutic alliance, and offering potential solutions.

Clinicians can recall the mnemonic “A SPORT” (Table) to help ensure they have a thorough discussion with patients about the risks of discontinuation and potential solutions.

Points to cover

First, explore and acknowledge if a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, which may be causing them to have a negative attitude toward medications. If a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, offer interventions to mitigate those effects, such as adding an anticholinergic agent to address extrapyramidal symptoms. Decreasing the antipsychotic dosage might reduce the adverse effects burden while still optimizing the benefits from the antipsychotic. Additionally, switching to an alternate medication with a more favorable adverse effect profile may be an option. Whether the patient is experiencing intolerable adverse effects or just has a negative view of their prescribed antipsychotic, it is important to discuss switching medications.

Identifying patient attitudes and their general perspective toward their medication and illness is key. Similarly, a patient’s impaired insight into their mental illness has been associated with treatment discontinuation.2 A strong therapeutic alliance with your patient is of the utmost importance in these situations.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are useful clinical tools for patients who struggle to adhere to oral medications. Educating patients and caregivers about other formulations—namely LAIs—can help clarify any misconceptions they may have. One study found that patients who were prescribed oral antipsychotics thought LAIs would be painful, have worse adverse effects, and would not be beneficial in preventing relapse.3 In addition to LAIs, other formulations of antipsychotic medications, such as patches, sublingual tablets, or liquids, may be an option.

For patients to be able to provide informed consent regarding the decision to discontinue their antipsychotic, it is important to educate them about the risks of not taking an antipsychotic, such as an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and poor outcomes. Explain that patients with first-episode psychosis who achieve remission of symptoms while taking an antipsychotic can remain in remission with continued treatment, but there is a 5-fold increased risk of relapse when discontinuing an antipsychotic during first-episode psychosis.4

Lastly, despite discussing the risks and benefits, if a patient is determined to discontinue their antipsychotic, we recommend a slow taper of medication rather than abrupt discontinuation. Research has shown that more than one-half of patients who abruptly discontinue an antipsychotic experience withdrawal symptoms, including (but not limited to) nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches, as well as anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.5 These symptoms may occur within 4 weeks after discontinuation.5 While there are no clear guidelines on deprescribing antipsychotics, it is best to individualize the taper based on patient response. Family and caregiver involvement, close follow-up, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the tapering process.6

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherenc. 2017;11:449-468. doi:10.2147/PPA.S124658

2. Kim J, Ozzoude M, Nakajima S, et al. Insight and medication adherence in schizophrenia: an analysis of the CATIE trial. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107634. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.05.011

3. Sugawara N, Kudo S, Ishioka M, et al. Attitudes toward long-acting injectable antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:205-211. doi:10.2147/NDT.S188337

4. Winton-Brown TT, Elanjithara T, Power P, et al. Five-fold increased risk of relapse following breaks in antipsychotic treatment of first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:50-56. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.029

5. Brandt L, Bschor T, Henssler J, et al. Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569912. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569912

6. Gupta S, Cahill JD, Miller R. Deprescribing antipsychotics: a guide for clinicians. BJPsych Advances. 2018;24(5):295-302. doi:10.1192/bja.2018.2

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherenc. 2017;11:449-468. doi:10.2147/PPA.S124658

2. Kim J, Ozzoude M, Nakajima S, et al. Insight and medication adherence in schizophrenia: an analysis of the CATIE trial. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107634. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.05.011

3. Sugawara N, Kudo S, Ishioka M, et al. Attitudes toward long-acting injectable antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:205-211. doi:10.2147/NDT.S188337

4. Winton-Brown TT, Elanjithara T, Power P, et al. Five-fold increased risk of relapse following breaks in antipsychotic treatment of first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:50-56. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.029

5. Brandt L, Bschor T, Henssler J, et al. Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569912. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569912

6. Gupta S, Cahill JD, Miller R. Deprescribing antipsychotics: a guide for clinicians. BJPsych Advances. 2018;24(5):295-302. doi:10.1192/bja.2018.2

Tips for efficient night shift work in a psychiatric ED

Attending psychiatrists who work night shift in a psychiatric emergency department (ED) or medical ED require a different set of skills than when working daytime or evening shifts, especially when working full-time or solo. While all patients should be treated carefully and meticulously regardless of the shift, this article offers tips for efficiency for solo attending psychiatrists who work night shift in an ED.

Check orders. Typically, multiple psychiatric clinicians are available on other shifts, but only 1 at night. This can lead to significant variability and potential errors in patients’ orders. Such errors filter down to night shift and often must be addressed by the solo clinician, who can’t say “that person is not my patient” because there are no other clinicians available to help. Carefully check orders (ideally, on all patients every shift) to ensure there are no errors or omissions.

Use note templates. While it is important to avoid using mere checklists, with electronic medical record systems, create templates for typical notes. This will save time when the pace of patients increases.

Be brief in your documentation. Brevity is key when documenting at night. Focus on what is necessary and sufficient.

Conduct thorough but efficient interviews. Be aware of how much time you spend on patient interviews. While still thorough, interviews must often be shorter due to a higher staff-to-patient ratio at night.

Be aware of potential medical issues. Many psychiatric EDs are not attached to a hospital. With other medical consultants not readily available in the middle of the night, be particularly alert for any acute medical issues that may arise, and act accordingly.

Focus on the order of tasks. Be aware of which tasks you complete and in what order. For example, at night you may need to medicate sooner for agitation because other patients are sleeping, instead of letting one patient’s agitation disrupt the entire night milieu.

Continue to: Don't let tasks pile up

Don’t let tasks pile up. Time management and multitasking are key skills at night. Take care of clinical issues as they arise. Finish documentation as you go along. Don’t let things pile up throughout your shift and then spend significant time after your shift to catch up.

Know your staff. The staff around you are your eyes and ears. Get to know your clinical and nonclinical staff’s tendencies. This can be immensely helpful in picking up any different patterns when interviewing and observing patients.

Know your limits. You may not be able to solve everything or obtain the ideal collateral at night. Don’t get caught up in definitively trying to resolve things and end up wasting precious time at night. Let it go. Don’t overthink. If all else fails, hold the patient overnight.

Prioritize self-care. Night shift work has been shown to negatively impact one’s health.1-3 If you choose this type of work, either part-time or full-time, maintain your own health by exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, obtaining adequate rest between shifts, and seeing your health care team often.

1. Wu QJ, Sun H, Wen ZY, et al. Shift work and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of epidemiological studies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(2):653-662. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9642

2. Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ. 2016;355:i5210. doi:10.1136/bmj.i5210

3. Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2014;62(5):292-301. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2014.08.001

Attending psychiatrists who work night shift in a psychiatric emergency department (ED) or medical ED require a different set of skills than when working daytime or evening shifts, especially when working full-time or solo. While all patients should be treated carefully and meticulously regardless of the shift, this article offers tips for efficiency for solo attending psychiatrists who work night shift in an ED.

Check orders. Typically, multiple psychiatric clinicians are available on other shifts, but only 1 at night. This can lead to significant variability and potential errors in patients’ orders. Such errors filter down to night shift and often must be addressed by the solo clinician, who can’t say “that person is not my patient” because there are no other clinicians available to help. Carefully check orders (ideally, on all patients every shift) to ensure there are no errors or omissions.

Use note templates. While it is important to avoid using mere checklists, with electronic medical record systems, create templates for typical notes. This will save time when the pace of patients increases.

Be brief in your documentation. Brevity is key when documenting at night. Focus on what is necessary and sufficient.

Conduct thorough but efficient interviews. Be aware of how much time you spend on patient interviews. While still thorough, interviews must often be shorter due to a higher staff-to-patient ratio at night.

Be aware of potential medical issues. Many psychiatric EDs are not attached to a hospital. With other medical consultants not readily available in the middle of the night, be particularly alert for any acute medical issues that may arise, and act accordingly.

Focus on the order of tasks. Be aware of which tasks you complete and in what order. For example, at night you may need to medicate sooner for agitation because other patients are sleeping, instead of letting one patient’s agitation disrupt the entire night milieu.

Continue to: Don't let tasks pile up

Don’t let tasks pile up. Time management and multitasking are key skills at night. Take care of clinical issues as they arise. Finish documentation as you go along. Don’t let things pile up throughout your shift and then spend significant time after your shift to catch up.

Know your staff. The staff around you are your eyes and ears. Get to know your clinical and nonclinical staff’s tendencies. This can be immensely helpful in picking up any different patterns when interviewing and observing patients.

Know your limits. You may not be able to solve everything or obtain the ideal collateral at night. Don’t get caught up in definitively trying to resolve things and end up wasting precious time at night. Let it go. Don’t overthink. If all else fails, hold the patient overnight.

Prioritize self-care. Night shift work has been shown to negatively impact one’s health.1-3 If you choose this type of work, either part-time or full-time, maintain your own health by exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, obtaining adequate rest between shifts, and seeing your health care team often.

Attending psychiatrists who work night shift in a psychiatric emergency department (ED) or medical ED require a different set of skills than when working daytime or evening shifts, especially when working full-time or solo. While all patients should be treated carefully and meticulously regardless of the shift, this article offers tips for efficiency for solo attending psychiatrists who work night shift in an ED.

Check orders. Typically, multiple psychiatric clinicians are available on other shifts, but only 1 at night. This can lead to significant variability and potential errors in patients’ orders. Such errors filter down to night shift and often must be addressed by the solo clinician, who can’t say “that person is not my patient” because there are no other clinicians available to help. Carefully check orders (ideally, on all patients every shift) to ensure there are no errors or omissions.

Use note templates. While it is important to avoid using mere checklists, with electronic medical record systems, create templates for typical notes. This will save time when the pace of patients increases.

Be brief in your documentation. Brevity is key when documenting at night. Focus on what is necessary and sufficient.

Conduct thorough but efficient interviews. Be aware of how much time you spend on patient interviews. While still thorough, interviews must often be shorter due to a higher staff-to-patient ratio at night.

Be aware of potential medical issues. Many psychiatric EDs are not attached to a hospital. With other medical consultants not readily available in the middle of the night, be particularly alert for any acute medical issues that may arise, and act accordingly.

Focus on the order of tasks. Be aware of which tasks you complete and in what order. For example, at night you may need to medicate sooner for agitation because other patients are sleeping, instead of letting one patient’s agitation disrupt the entire night milieu.

Continue to: Don't let tasks pile up

Don’t let tasks pile up. Time management and multitasking are key skills at night. Take care of clinical issues as they arise. Finish documentation as you go along. Don’t let things pile up throughout your shift and then spend significant time after your shift to catch up.

Know your staff. The staff around you are your eyes and ears. Get to know your clinical and nonclinical staff’s tendencies. This can be immensely helpful in picking up any different patterns when interviewing and observing patients.

Know your limits. You may not be able to solve everything or obtain the ideal collateral at night. Don’t get caught up in definitively trying to resolve things and end up wasting precious time at night. Let it go. Don’t overthink. If all else fails, hold the patient overnight.

Prioritize self-care. Night shift work has been shown to negatively impact one’s health.1-3 If you choose this type of work, either part-time or full-time, maintain your own health by exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, obtaining adequate rest between shifts, and seeing your health care team often.

1. Wu QJ, Sun H, Wen ZY, et al. Shift work and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of epidemiological studies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(2):653-662. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9642

2. Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ. 2016;355:i5210. doi:10.1136/bmj.i5210

3. Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2014;62(5):292-301. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2014.08.001

1. Wu QJ, Sun H, Wen ZY, et al. Shift work and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of epidemiological studies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(2):653-662. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9642

2. Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ. 2016;355:i5210. doi:10.1136/bmj.i5210

3. Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2014;62(5):292-301. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2014.08.001