User login

Clonidine: Off-label uses in pediatric patients

Clonidine is a centrally acting alpha-2 agonist originally developed for treating hypertension. It is believed to work by stimulating alpha-2 receptors in various areas of the brain. It is nonselective, binding alpha-2A, -2B, and -2C receptors, and mediates inattentiveness, hyperactivity, impulsivity, sedation, and hypotension.1 Clonidine is available as immediate-release (IR), extended-release, and patch formulations, with typical doses ranging from 0.1 to 0.4 mg/d. The most common adverse effects are anticholinergic, such as sedation, dry mouth, and constipation. Since clonidine is effective at lowering blood pressure, the main safety concern is the possibility of rebound hypertension if abruptly stopped, which necessitates a short taper period.1

In child and adolescent psychiatry, the only FDA-approved use of clonidine is for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Yet this medication has been increasingly used off-label for several common psychiatric ailments in pediatric patients. In this article, we discuss potential uses of clonidine in child and adolescent psychiatry; except for ADHD, all uses we describe are off-label.

ADHD. Clonidine is effective both as a monotherapy and as an adjunctive therapy to stimulants for pediatric ADHD. When used alone, clonidine is better suited for patients who have hyperactivity as their primary concern, whereas stimulants may be better suited for patients with inattentive subtypes. It also can help reduce sleep disturbances associated with the use of stimulants, especially insomnia.1

Tics/Tourette syndrome. Clonidine is a first-line treatment for tics in Tourette syndrome, demonstrating high efficacy with limited or no adverse effects. Furthermore, ADHD is the most common comorbid condition in patients with dystonic tics, which makes clonidine useful for simultaneously treating both conditions.2

Insomnia. Currently, there are no FDA-approved medications for treating sleep disorders in children and adolescents. However, clonidine is among the most used medications for childhood sleep difficulties, second only to antihistamines. The IR formulation is often preferred for this indication due to increased sedation.3

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research has shown clonidine can help reduce hyperarousal symptoms, address sleep difficulties, and reduce PTSD trauma nightmares, anxiety, and irritability.4

Substance detoxification. Clonidine successfully suppresses opiate withdrawal signs and symptoms by reducing sympathetic overactivity. It can help with alcohol withdrawal and smoking cessation.2

Antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Controlled trials have shown that clonidine significantly reduces akathisia associated with the use of antipsychotics.2

Sialorrhea. Due to its anticholinergic effects, clonidine can effectively reduce antipsychotic-induced hypersalivation.2

Behavioral disturbances. Due to its sedative and anti-impulsive properties, clonidine can be used to address broadly defined behavioral issues, including anxiety-related behaviors, aggression, and agitation, although there is a lack of proven efficacy.1,2,4

1. Stahl SM, Grady MM, Muntner N. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Prescriber’s Guide: Children and Adolescents. Cambridge University Press; 2019.

2. Naguy A. Clonidine use in psychiatry: panacea or panache. Pharmacology. 2016;98(1-2):87-92. doi:10.1159/000446441

3. Jang YJ, Choi H, Han TS, et al. Effectiveness of clonidine in child and adolescent sleep disorders. Psychiatry Investig. 2022;19(9):738-747. doi:10.30773/pi.2022.0117

4. Bajor LA, Balsara C, Osser DN. An evidence-based approach to psychopharmacology for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - 2022 update. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114840. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114840

Clonidine is a centrally acting alpha-2 agonist originally developed for treating hypertension. It is believed to work by stimulating alpha-2 receptors in various areas of the brain. It is nonselective, binding alpha-2A, -2B, and -2C receptors, and mediates inattentiveness, hyperactivity, impulsivity, sedation, and hypotension.1 Clonidine is available as immediate-release (IR), extended-release, and patch formulations, with typical doses ranging from 0.1 to 0.4 mg/d. The most common adverse effects are anticholinergic, such as sedation, dry mouth, and constipation. Since clonidine is effective at lowering blood pressure, the main safety concern is the possibility of rebound hypertension if abruptly stopped, which necessitates a short taper period.1

In child and adolescent psychiatry, the only FDA-approved use of clonidine is for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Yet this medication has been increasingly used off-label for several common psychiatric ailments in pediatric patients. In this article, we discuss potential uses of clonidine in child and adolescent psychiatry; except for ADHD, all uses we describe are off-label.

ADHD. Clonidine is effective both as a monotherapy and as an adjunctive therapy to stimulants for pediatric ADHD. When used alone, clonidine is better suited for patients who have hyperactivity as their primary concern, whereas stimulants may be better suited for patients with inattentive subtypes. It also can help reduce sleep disturbances associated with the use of stimulants, especially insomnia.1

Tics/Tourette syndrome. Clonidine is a first-line treatment for tics in Tourette syndrome, demonstrating high efficacy with limited or no adverse effects. Furthermore, ADHD is the most common comorbid condition in patients with dystonic tics, which makes clonidine useful for simultaneously treating both conditions.2

Insomnia. Currently, there are no FDA-approved medications for treating sleep disorders in children and adolescents. However, clonidine is among the most used medications for childhood sleep difficulties, second only to antihistamines. The IR formulation is often preferred for this indication due to increased sedation.3

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research has shown clonidine can help reduce hyperarousal symptoms, address sleep difficulties, and reduce PTSD trauma nightmares, anxiety, and irritability.4

Substance detoxification. Clonidine successfully suppresses opiate withdrawal signs and symptoms by reducing sympathetic overactivity. It can help with alcohol withdrawal and smoking cessation.2

Antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Controlled trials have shown that clonidine significantly reduces akathisia associated with the use of antipsychotics.2

Sialorrhea. Due to its anticholinergic effects, clonidine can effectively reduce antipsychotic-induced hypersalivation.2

Behavioral disturbances. Due to its sedative and anti-impulsive properties, clonidine can be used to address broadly defined behavioral issues, including anxiety-related behaviors, aggression, and agitation, although there is a lack of proven efficacy.1,2,4

Clonidine is a centrally acting alpha-2 agonist originally developed for treating hypertension. It is believed to work by stimulating alpha-2 receptors in various areas of the brain. It is nonselective, binding alpha-2A, -2B, and -2C receptors, and mediates inattentiveness, hyperactivity, impulsivity, sedation, and hypotension.1 Clonidine is available as immediate-release (IR), extended-release, and patch formulations, with typical doses ranging from 0.1 to 0.4 mg/d. The most common adverse effects are anticholinergic, such as sedation, dry mouth, and constipation. Since clonidine is effective at lowering blood pressure, the main safety concern is the possibility of rebound hypertension if abruptly stopped, which necessitates a short taper period.1

In child and adolescent psychiatry, the only FDA-approved use of clonidine is for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Yet this medication has been increasingly used off-label for several common psychiatric ailments in pediatric patients. In this article, we discuss potential uses of clonidine in child and adolescent psychiatry; except for ADHD, all uses we describe are off-label.

ADHD. Clonidine is effective both as a monotherapy and as an adjunctive therapy to stimulants for pediatric ADHD. When used alone, clonidine is better suited for patients who have hyperactivity as their primary concern, whereas stimulants may be better suited for patients with inattentive subtypes. It also can help reduce sleep disturbances associated with the use of stimulants, especially insomnia.1

Tics/Tourette syndrome. Clonidine is a first-line treatment for tics in Tourette syndrome, demonstrating high efficacy with limited or no adverse effects. Furthermore, ADHD is the most common comorbid condition in patients with dystonic tics, which makes clonidine useful for simultaneously treating both conditions.2

Insomnia. Currently, there are no FDA-approved medications for treating sleep disorders in children and adolescents. However, clonidine is among the most used medications for childhood sleep difficulties, second only to antihistamines. The IR formulation is often preferred for this indication due to increased sedation.3

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research has shown clonidine can help reduce hyperarousal symptoms, address sleep difficulties, and reduce PTSD trauma nightmares, anxiety, and irritability.4

Substance detoxification. Clonidine successfully suppresses opiate withdrawal signs and symptoms by reducing sympathetic overactivity. It can help with alcohol withdrawal and smoking cessation.2

Antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Controlled trials have shown that clonidine significantly reduces akathisia associated with the use of antipsychotics.2

Sialorrhea. Due to its anticholinergic effects, clonidine can effectively reduce antipsychotic-induced hypersalivation.2

Behavioral disturbances. Due to its sedative and anti-impulsive properties, clonidine can be used to address broadly defined behavioral issues, including anxiety-related behaviors, aggression, and agitation, although there is a lack of proven efficacy.1,2,4

1. Stahl SM, Grady MM, Muntner N. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Prescriber’s Guide: Children and Adolescents. Cambridge University Press; 2019.

2. Naguy A. Clonidine use in psychiatry: panacea or panache. Pharmacology. 2016;98(1-2):87-92. doi:10.1159/000446441

3. Jang YJ, Choi H, Han TS, et al. Effectiveness of clonidine in child and adolescent sleep disorders. Psychiatry Investig. 2022;19(9):738-747. doi:10.30773/pi.2022.0117

4. Bajor LA, Balsara C, Osser DN. An evidence-based approach to psychopharmacology for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - 2022 update. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114840. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114840

1. Stahl SM, Grady MM, Muntner N. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Prescriber’s Guide: Children and Adolescents. Cambridge University Press; 2019.

2. Naguy A. Clonidine use in psychiatry: panacea or panache. Pharmacology. 2016;98(1-2):87-92. doi:10.1159/000446441

3. Jang YJ, Choi H, Han TS, et al. Effectiveness of clonidine in child and adolescent sleep disorders. Psychiatry Investig. 2022;19(9):738-747. doi:10.30773/pi.2022.0117

4. Bajor LA, Balsara C, Osser DN. An evidence-based approach to psychopharmacology for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - 2022 update. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114840. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114840

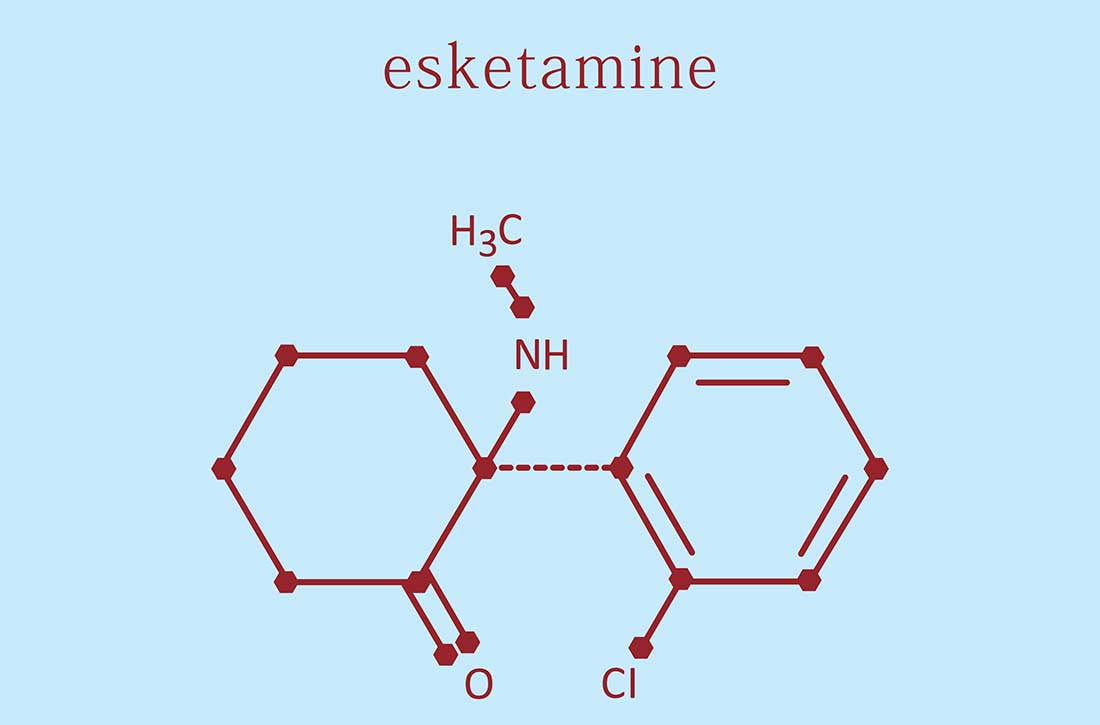

Intranasal esketamine: A primer

Intranasal esketamine is an FDA-approved ketamine molecule indicated for use together with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in patients age ≥18 who have had an inadequate response to ≥2 antidepressants, and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts or actions.¹ Since March 2019, we’ve been treating patients with intranasal esketamine. Based on our experiences, here is a summary of what we have learned.

REMS is required. Due to the potential risks resulting from sedation and dissociation caused by esketamine and the risk of abuse and misuse, esketamine is available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The program links your office Drug Enforcement Administration number to the address where this schedule III medication will be stored and given to the patient for self-administration. Requirements and other details about the REMS are available at www.spravatorems.com.

Treatment. Start with the online REMS patient enrollment/consent form. Contraindications include having a history of aneurysmal vascular disease, intracerebral hemorrhage, or allergy to ketamine/esketamine. Adjunctive treatment with esketamine plus sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, or duloxetine are comparably effective.¹ We have found that adding magnesium to block glutamate action at N-methyl-

Iatrogenic effects rarely lead to dropout. The first session is critical to allay anticipatory anxiety. Sedation, blood pressure increase, and dissociation are common but transient adverse effects that typically peak at 40 minutes and resolve by 90 minutes. Record blood pressure on a REMS monitoring form before treatment, at 40 minutes, and at 2 hours. Avoid administering sedative or prohypertensive medications together with esketamine.¹ Dissociation is more common in patients with a history of trauma. Combine music, guided imagery, or psychotherapy to harness this for therapeutic benefit. Sleepiness can last 4 hours; make sure the patient has arranged for a ride home, as they cannot drive until the next day. Verify normal blood pressure before starting treatment. Clonidine or labetalol for hypertension/severe dissociation and ondansetron or prochlorperazine for nausea are rarely needed. Advise patients to use the bathroom before treatment and keep a trash can nearby for vomiting. Other transient adverse effects found in TRD clinical trials that occurred >5% and twice that of placebo were dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and feeling drunk.¹

Reimbursement for treatment with esketamine is available through most insurances, including copay cards, rebates, deductible support, and free assistance programs. Coverage is either through pharmacy benefit, assignment of medical benefit (pharmacy handles the medical benefit), or medical benefit with remuneration above wholesale price.

Zeitgeist shift. Emergency departments are backlogged and patients languish waiting to feel the effects of oral antidepressants. Intranasal esketamine could help alleviate this situation by producing a more immediate response. We also have observed improvements in comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and in cognitive deficits of dementia, possibly due to rapidly enhanced neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, and astrocyte functioning, which NMDA receptor antagonism, AMPA activation, and downstream mediators (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor) may promote.4

1. Spravato (esketamine nasal spray) medication guide. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-patient-information/SPRAVATO-medication-guide.pdf

2. Spravato Healthcare Professional Website. TRD safety & efficacy. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.spravatohcp.com/trd-long-term/efficacy

3. Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428-438. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020172

4. Matveychuk D, Thomas RK, Swainson J, et al. Ketamine as an antidepressant: overview of its mechanisms of action and potential predictive biomarkers. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320916657. doi:10.1177/2045125320916657

Intranasal esketamine is an FDA-approved ketamine molecule indicated for use together with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in patients age ≥18 who have had an inadequate response to ≥2 antidepressants, and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts or actions.¹ Since March 2019, we’ve been treating patients with intranasal esketamine. Based on our experiences, here is a summary of what we have learned.

REMS is required. Due to the potential risks resulting from sedation and dissociation caused by esketamine and the risk of abuse and misuse, esketamine is available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The program links your office Drug Enforcement Administration number to the address where this schedule III medication will be stored and given to the patient for self-administration. Requirements and other details about the REMS are available at www.spravatorems.com.

Treatment. Start with the online REMS patient enrollment/consent form. Contraindications include having a history of aneurysmal vascular disease, intracerebral hemorrhage, or allergy to ketamine/esketamine. Adjunctive treatment with esketamine plus sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, or duloxetine are comparably effective.¹ We have found that adding magnesium to block glutamate action at N-methyl-

Iatrogenic effects rarely lead to dropout. The first session is critical to allay anticipatory anxiety. Sedation, blood pressure increase, and dissociation are common but transient adverse effects that typically peak at 40 minutes and resolve by 90 minutes. Record blood pressure on a REMS monitoring form before treatment, at 40 minutes, and at 2 hours. Avoid administering sedative or prohypertensive medications together with esketamine.¹ Dissociation is more common in patients with a history of trauma. Combine music, guided imagery, or psychotherapy to harness this for therapeutic benefit. Sleepiness can last 4 hours; make sure the patient has arranged for a ride home, as they cannot drive until the next day. Verify normal blood pressure before starting treatment. Clonidine or labetalol for hypertension/severe dissociation and ondansetron or prochlorperazine for nausea are rarely needed. Advise patients to use the bathroom before treatment and keep a trash can nearby for vomiting. Other transient adverse effects found in TRD clinical trials that occurred >5% and twice that of placebo were dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and feeling drunk.¹

Reimbursement for treatment with esketamine is available through most insurances, including copay cards, rebates, deductible support, and free assistance programs. Coverage is either through pharmacy benefit, assignment of medical benefit (pharmacy handles the medical benefit), or medical benefit with remuneration above wholesale price.

Zeitgeist shift. Emergency departments are backlogged and patients languish waiting to feel the effects of oral antidepressants. Intranasal esketamine could help alleviate this situation by producing a more immediate response. We also have observed improvements in comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and in cognitive deficits of dementia, possibly due to rapidly enhanced neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, and astrocyte functioning, which NMDA receptor antagonism, AMPA activation, and downstream mediators (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor) may promote.4

Intranasal esketamine is an FDA-approved ketamine molecule indicated for use together with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in patients age ≥18 who have had an inadequate response to ≥2 antidepressants, and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts or actions.¹ Since March 2019, we’ve been treating patients with intranasal esketamine. Based on our experiences, here is a summary of what we have learned.

REMS is required. Due to the potential risks resulting from sedation and dissociation caused by esketamine and the risk of abuse and misuse, esketamine is available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The program links your office Drug Enforcement Administration number to the address where this schedule III medication will be stored and given to the patient for self-administration. Requirements and other details about the REMS are available at www.spravatorems.com.

Treatment. Start with the online REMS patient enrollment/consent form. Contraindications include having a history of aneurysmal vascular disease, intracerebral hemorrhage, or allergy to ketamine/esketamine. Adjunctive treatment with esketamine plus sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, or duloxetine are comparably effective.¹ We have found that adding magnesium to block glutamate action at N-methyl-

Iatrogenic effects rarely lead to dropout. The first session is critical to allay anticipatory anxiety. Sedation, blood pressure increase, and dissociation are common but transient adverse effects that typically peak at 40 minutes and resolve by 90 minutes. Record blood pressure on a REMS monitoring form before treatment, at 40 minutes, and at 2 hours. Avoid administering sedative or prohypertensive medications together with esketamine.¹ Dissociation is more common in patients with a history of trauma. Combine music, guided imagery, or psychotherapy to harness this for therapeutic benefit. Sleepiness can last 4 hours; make sure the patient has arranged for a ride home, as they cannot drive until the next day. Verify normal blood pressure before starting treatment. Clonidine or labetalol for hypertension/severe dissociation and ondansetron or prochlorperazine for nausea are rarely needed. Advise patients to use the bathroom before treatment and keep a trash can nearby for vomiting. Other transient adverse effects found in TRD clinical trials that occurred >5% and twice that of placebo were dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and feeling drunk.¹

Reimbursement for treatment with esketamine is available through most insurances, including copay cards, rebates, deductible support, and free assistance programs. Coverage is either through pharmacy benefit, assignment of medical benefit (pharmacy handles the medical benefit), or medical benefit with remuneration above wholesale price.

Zeitgeist shift. Emergency departments are backlogged and patients languish waiting to feel the effects of oral antidepressants. Intranasal esketamine could help alleviate this situation by producing a more immediate response. We also have observed improvements in comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and in cognitive deficits of dementia, possibly due to rapidly enhanced neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, and astrocyte functioning, which NMDA receptor antagonism, AMPA activation, and downstream mediators (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor) may promote.4

1. Spravato (esketamine nasal spray) medication guide. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-patient-information/SPRAVATO-medication-guide.pdf

2. Spravato Healthcare Professional Website. TRD safety & efficacy. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.spravatohcp.com/trd-long-term/efficacy

3. Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428-438. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020172

4. Matveychuk D, Thomas RK, Swainson J, et al. Ketamine as an antidepressant: overview of its mechanisms of action and potential predictive biomarkers. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320916657. doi:10.1177/2045125320916657

1. Spravato (esketamine nasal spray) medication guide. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-patient-information/SPRAVATO-medication-guide.pdf

2. Spravato Healthcare Professional Website. TRD safety & efficacy. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.spravatohcp.com/trd-long-term/efficacy

3. Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428-438. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020172

4. Matveychuk D, Thomas RK, Swainson J, et al. Ketamine as an antidepressant: overview of its mechanisms of action and potential predictive biomarkers. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320916657. doi:10.1177/2045125320916657

Prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia: What to look for

Schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms that typically follow a prodromal period of premonitory signs and symptoms that appear before the manifestation of the full-blown syndrome. Signs and symptoms during the prodromal phase are subsyndromal, which implies a lower degree of intensity, duration, or frequency than observed when the patient meets the full criteria for the syndrome. Early detection of prodromal symptoms can improve prognosis, but these subtle symptoms may go unrecognized.

In schizophrenia, a patient may exhibit prodromal signs and symptoms before the appearance of pathognomonic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization. The schizophrenia prodrome can be conceptualized as a period of prepsychotic disturbances depicting an alteration in the individual’s behavior and perception. Prodromal symptoms can last from weeks to years before the psychotic illness clinically manifests.1 The prodromal symptom cluster typically becomes evident during adolescence and young adulthood.2

In the mid-1990s, investigators tried to identify a “putative prodrome” for psychosis. The term “at-risk mental state” (ARMS) for psychosis is based on retrospective reports of prodromal symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Over the next 2 decades, scales such as the Comprehensive Assessment of ARMS (CAARMS)3 and the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndrome4 were designed to enhance the objectivity and diagnostic accuracy of the ARMS. These scales have reasonable interrater reliability.5

Researchers also have attempted to stage the severity of ARMS.6 Key symptom group predictors were studied to determine which individual symptoms or cluster of symptoms are most associated with poor outcomes and progression to psychosis. Raballo et al7 found the severity of the CAARMS disorganization dimension was the strongest predictor of transition to frank psychosis. Other research suggests that approximately one-third of ARMS patients transition to psychosis within 3 years, another one-third have persistent attenuated psychotic symptoms, and the remaining one-third experience symptom remission.8,9

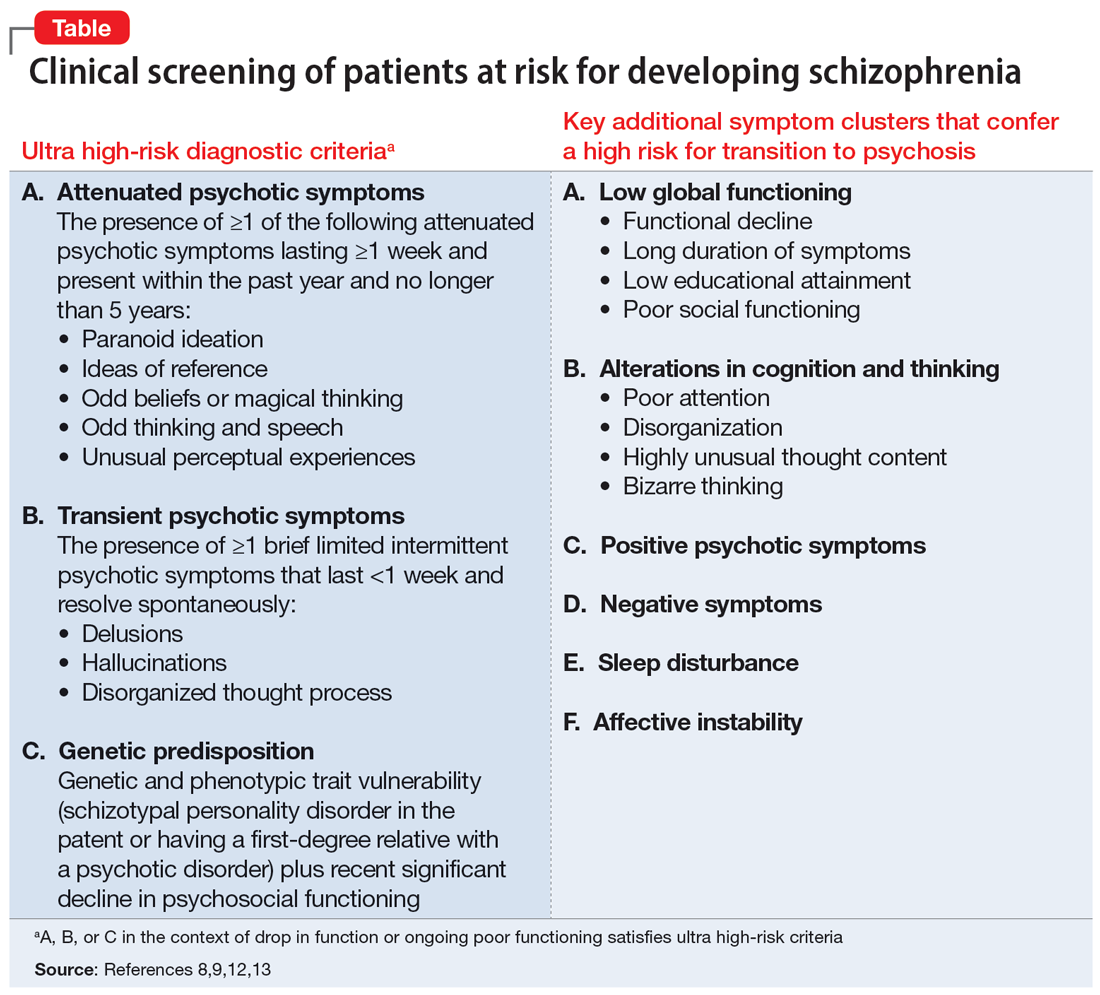

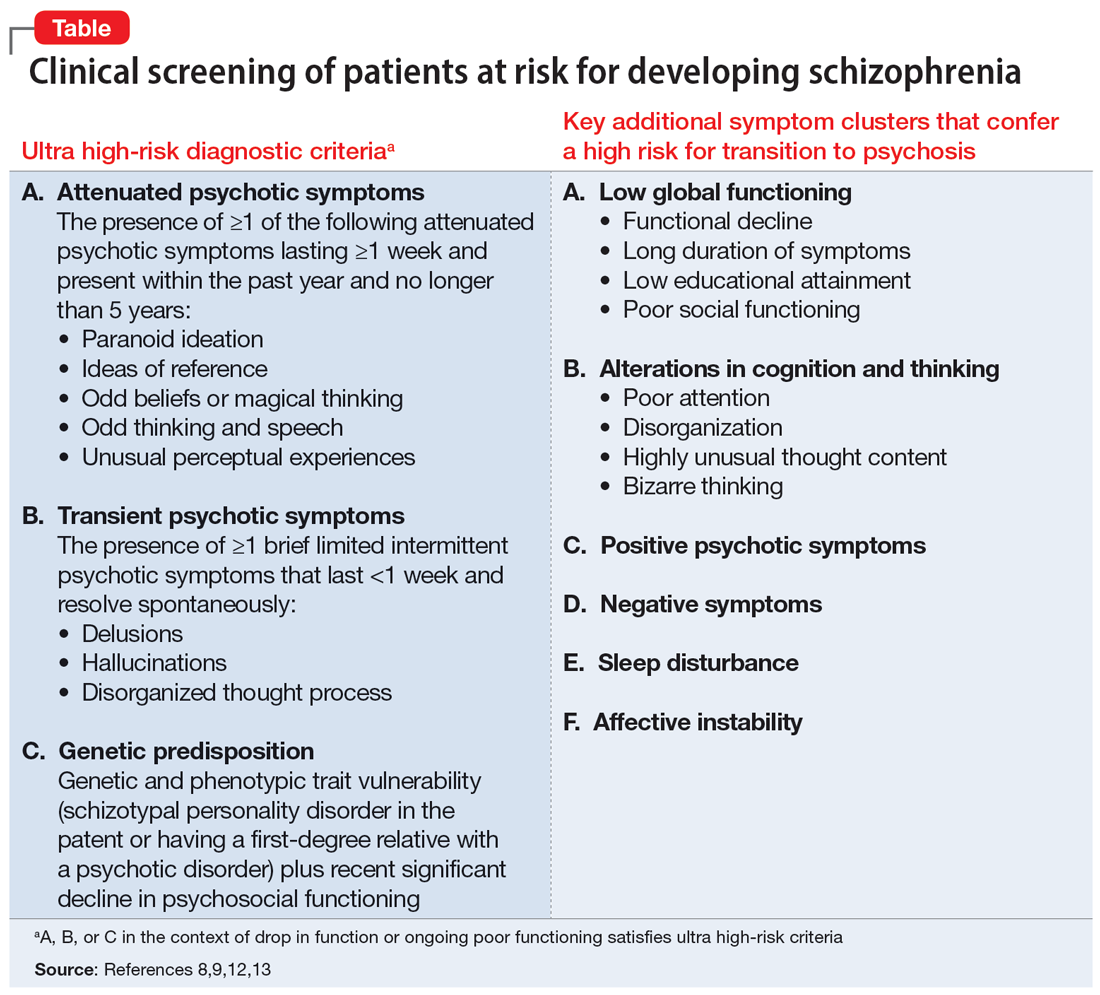

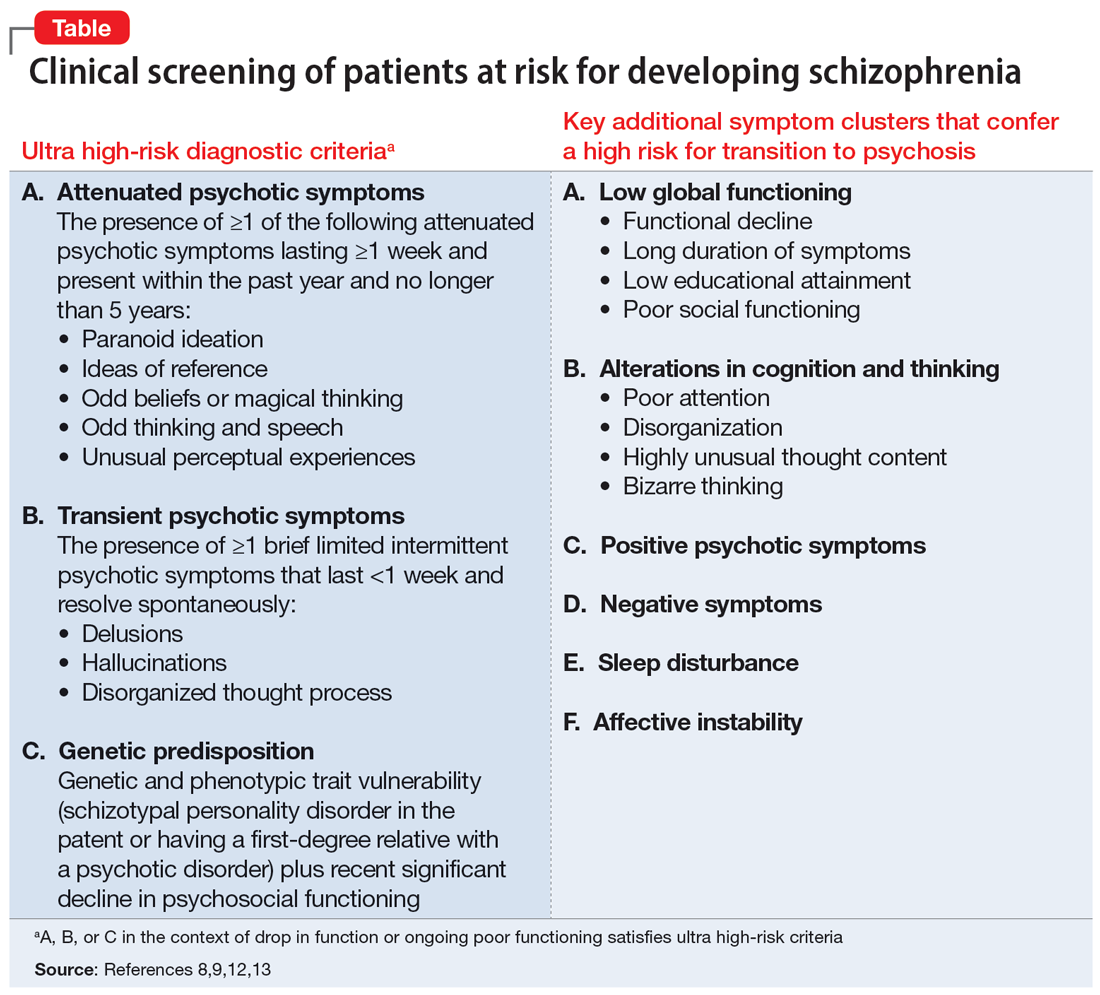

Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, current scales and clinical predictors continue to be imperfect.8 Efforts to identify specific biological markers and predictors of transition to clinical psychosis have not been successful for ARMS.10,11 The Table8,9,12,13 summarizes diagnostic criteria that have been developed to more clearly identify which ARMS patients face the highest imminent risk for transition to psychosis; these have been referred to as ultra high-risk (UHR) criteria.14 These UHR criteria depict 3 categories of clinical presentation believed to confer risk of transition to psychosis: attenuated psychotic symptoms, transient psychotic symptoms, and genetic predisposition. Subsequent research found that certain additional symptom variables, as well as combinations of specific symptom clusters, conferred increased risk and improved the positive predictive sensitivity to as high as 83%.15 In addition to the UHR criteria, the Table8,9,12,13 also lists these additional variables shown to confer a high positive predictive value (PPV) of transition, alone or in combination with the UHR criterion. Thompson et al16 provide more detailed information on these later variables and their relative PPV.

What about treatment?

While discussion of the optimal treatment options for patients with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia is beyond the scope of this article, early interventions can focus on preventing the biological, psychological, and social disruption that results from such symptoms. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient while they retain insight and engaging supportive family members is a key starting point. Case management, cognitive-behavioral or supportive therapy, and treatment of comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are helpful. There is no clear consensus on the utility of pharmacotherapy in the prodromal stage of psychosis. While scales and structured interviews can guide assessment, clinical judgment is the key driver of the appropriateness of initiating pharmacologic treatment to address symptoms. Because up to two-thirds of patients who satisfy UHR criteria do not go on to develop schizophrenia,16 clinicians should be thoughtful about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics.

1. George M, Maheshwari S, Chandran S, et al. Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(4):505-509.

2. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353-370.

3. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964-971.

4. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703-715.

5. Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, et al. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire--brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42-46.

6. Nieman DH, McGorry PD. Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):825-834.

7. Raballo A, Nelson B, Thompson A, et al. The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states: from mapping the onset to mapping the structure. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1-3):107-114.

8. Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220-229.

9. Cannon TD. How schizophrenia develops: cognitive and brain mechanisms underlying onset of psychosis. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(12):744-756.

10. Castle DJ. Is it appropriate to treat people at high-risk of psychosis before first onset? - no. Med J Aust. 2012;196(9):557.

11. Wood SJ, Reniers RL, Heinze K. Neuroimaging findings in the at-risk mental state: a review of recent literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):13-18.

12. Nelson B, Yung AR. Can clinicians predict psychosis in an ultra high risk group? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(7):625-630.

13. Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):405-416.

14. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):131-142.

15. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, et al. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European prediction of psychosis study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):241-251.

16. Thompson A, Marwaha S, Broome MR. At-risk mental state for psychosis: identification and current treatment approaches. BJPsych Advances. 2016;22(3):186-193.

Schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms that typically follow a prodromal period of premonitory signs and symptoms that appear before the manifestation of the full-blown syndrome. Signs and symptoms during the prodromal phase are subsyndromal, which implies a lower degree of intensity, duration, or frequency than observed when the patient meets the full criteria for the syndrome. Early detection of prodromal symptoms can improve prognosis, but these subtle symptoms may go unrecognized.

In schizophrenia, a patient may exhibit prodromal signs and symptoms before the appearance of pathognomonic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization. The schizophrenia prodrome can be conceptualized as a period of prepsychotic disturbances depicting an alteration in the individual’s behavior and perception. Prodromal symptoms can last from weeks to years before the psychotic illness clinically manifests.1 The prodromal symptom cluster typically becomes evident during adolescence and young adulthood.2

In the mid-1990s, investigators tried to identify a “putative prodrome” for psychosis. The term “at-risk mental state” (ARMS) for psychosis is based on retrospective reports of prodromal symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Over the next 2 decades, scales such as the Comprehensive Assessment of ARMS (CAARMS)3 and the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndrome4 were designed to enhance the objectivity and diagnostic accuracy of the ARMS. These scales have reasonable interrater reliability.5

Researchers also have attempted to stage the severity of ARMS.6 Key symptom group predictors were studied to determine which individual symptoms or cluster of symptoms are most associated with poor outcomes and progression to psychosis. Raballo et al7 found the severity of the CAARMS disorganization dimension was the strongest predictor of transition to frank psychosis. Other research suggests that approximately one-third of ARMS patients transition to psychosis within 3 years, another one-third have persistent attenuated psychotic symptoms, and the remaining one-third experience symptom remission.8,9

Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, current scales and clinical predictors continue to be imperfect.8 Efforts to identify specific biological markers and predictors of transition to clinical psychosis have not been successful for ARMS.10,11 The Table8,9,12,13 summarizes diagnostic criteria that have been developed to more clearly identify which ARMS patients face the highest imminent risk for transition to psychosis; these have been referred to as ultra high-risk (UHR) criteria.14 These UHR criteria depict 3 categories of clinical presentation believed to confer risk of transition to psychosis: attenuated psychotic symptoms, transient psychotic symptoms, and genetic predisposition. Subsequent research found that certain additional symptom variables, as well as combinations of specific symptom clusters, conferred increased risk and improved the positive predictive sensitivity to as high as 83%.15 In addition to the UHR criteria, the Table8,9,12,13 also lists these additional variables shown to confer a high positive predictive value (PPV) of transition, alone or in combination with the UHR criterion. Thompson et al16 provide more detailed information on these later variables and their relative PPV.

What about treatment?

While discussion of the optimal treatment options for patients with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia is beyond the scope of this article, early interventions can focus on preventing the biological, psychological, and social disruption that results from such symptoms. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient while they retain insight and engaging supportive family members is a key starting point. Case management, cognitive-behavioral or supportive therapy, and treatment of comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are helpful. There is no clear consensus on the utility of pharmacotherapy in the prodromal stage of psychosis. While scales and structured interviews can guide assessment, clinical judgment is the key driver of the appropriateness of initiating pharmacologic treatment to address symptoms. Because up to two-thirds of patients who satisfy UHR criteria do not go on to develop schizophrenia,16 clinicians should be thoughtful about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics.

Schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms that typically follow a prodromal period of premonitory signs and symptoms that appear before the manifestation of the full-blown syndrome. Signs and symptoms during the prodromal phase are subsyndromal, which implies a lower degree of intensity, duration, or frequency than observed when the patient meets the full criteria for the syndrome. Early detection of prodromal symptoms can improve prognosis, but these subtle symptoms may go unrecognized.

In schizophrenia, a patient may exhibit prodromal signs and symptoms before the appearance of pathognomonic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization. The schizophrenia prodrome can be conceptualized as a period of prepsychotic disturbances depicting an alteration in the individual’s behavior and perception. Prodromal symptoms can last from weeks to years before the psychotic illness clinically manifests.1 The prodromal symptom cluster typically becomes evident during adolescence and young adulthood.2

In the mid-1990s, investigators tried to identify a “putative prodrome” for psychosis. The term “at-risk mental state” (ARMS) for psychosis is based on retrospective reports of prodromal symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Over the next 2 decades, scales such as the Comprehensive Assessment of ARMS (CAARMS)3 and the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndrome4 were designed to enhance the objectivity and diagnostic accuracy of the ARMS. These scales have reasonable interrater reliability.5

Researchers also have attempted to stage the severity of ARMS.6 Key symptom group predictors were studied to determine which individual symptoms or cluster of symptoms are most associated with poor outcomes and progression to psychosis. Raballo et al7 found the severity of the CAARMS disorganization dimension was the strongest predictor of transition to frank psychosis. Other research suggests that approximately one-third of ARMS patients transition to psychosis within 3 years, another one-third have persistent attenuated psychotic symptoms, and the remaining one-third experience symptom remission.8,9

Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, current scales and clinical predictors continue to be imperfect.8 Efforts to identify specific biological markers and predictors of transition to clinical psychosis have not been successful for ARMS.10,11 The Table8,9,12,13 summarizes diagnostic criteria that have been developed to more clearly identify which ARMS patients face the highest imminent risk for transition to psychosis; these have been referred to as ultra high-risk (UHR) criteria.14 These UHR criteria depict 3 categories of clinical presentation believed to confer risk of transition to psychosis: attenuated psychotic symptoms, transient psychotic symptoms, and genetic predisposition. Subsequent research found that certain additional symptom variables, as well as combinations of specific symptom clusters, conferred increased risk and improved the positive predictive sensitivity to as high as 83%.15 In addition to the UHR criteria, the Table8,9,12,13 also lists these additional variables shown to confer a high positive predictive value (PPV) of transition, alone or in combination with the UHR criterion. Thompson et al16 provide more detailed information on these later variables and their relative PPV.

What about treatment?

While discussion of the optimal treatment options for patients with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia is beyond the scope of this article, early interventions can focus on preventing the biological, psychological, and social disruption that results from such symptoms. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient while they retain insight and engaging supportive family members is a key starting point. Case management, cognitive-behavioral or supportive therapy, and treatment of comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are helpful. There is no clear consensus on the utility of pharmacotherapy in the prodromal stage of psychosis. While scales and structured interviews can guide assessment, clinical judgment is the key driver of the appropriateness of initiating pharmacologic treatment to address symptoms. Because up to two-thirds of patients who satisfy UHR criteria do not go on to develop schizophrenia,16 clinicians should be thoughtful about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics.

1. George M, Maheshwari S, Chandran S, et al. Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(4):505-509.

2. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353-370.

3. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964-971.

4. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703-715.

5. Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, et al. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire--brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42-46.

6. Nieman DH, McGorry PD. Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):825-834.

7. Raballo A, Nelson B, Thompson A, et al. The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states: from mapping the onset to mapping the structure. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1-3):107-114.

8. Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220-229.

9. Cannon TD. How schizophrenia develops: cognitive and brain mechanisms underlying onset of psychosis. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(12):744-756.

10. Castle DJ. Is it appropriate to treat people at high-risk of psychosis before first onset? - no. Med J Aust. 2012;196(9):557.

11. Wood SJ, Reniers RL, Heinze K. Neuroimaging findings in the at-risk mental state: a review of recent literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):13-18.

12. Nelson B, Yung AR. Can clinicians predict psychosis in an ultra high risk group? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(7):625-630.

13. Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):405-416.

14. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):131-142.

15. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, et al. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European prediction of psychosis study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):241-251.

16. Thompson A, Marwaha S, Broome MR. At-risk mental state for psychosis: identification and current treatment approaches. BJPsych Advances. 2016;22(3):186-193.

1. George M, Maheshwari S, Chandran S, et al. Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(4):505-509.

2. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353-370.

3. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964-971.

4. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703-715.

5. Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, et al. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire--brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42-46.

6. Nieman DH, McGorry PD. Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):825-834.

7. Raballo A, Nelson B, Thompson A, et al. The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states: from mapping the onset to mapping the structure. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1-3):107-114.

8. Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220-229.

9. Cannon TD. How schizophrenia develops: cognitive and brain mechanisms underlying onset of psychosis. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(12):744-756.

10. Castle DJ. Is it appropriate to treat people at high-risk of psychosis before first onset? - no. Med J Aust. 2012;196(9):557.

11. Wood SJ, Reniers RL, Heinze K. Neuroimaging findings in the at-risk mental state: a review of recent literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):13-18.

12. Nelson B, Yung AR. Can clinicians predict psychosis in an ultra high risk group? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(7):625-630.

13. Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):405-416.

14. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):131-142.

15. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, et al. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European prediction of psychosis study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):241-251.

16. Thompson A, Marwaha S, Broome MR. At-risk mental state for psychosis: identification and current treatment approaches. BJPsych Advances. 2016;22(3):186-193.

Scurvy in psychiatric patients: An easy-to-miss diagnosis

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

Breast cancer screening in women receiving antipsychotics

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

Psychotropic medications for chronic pain

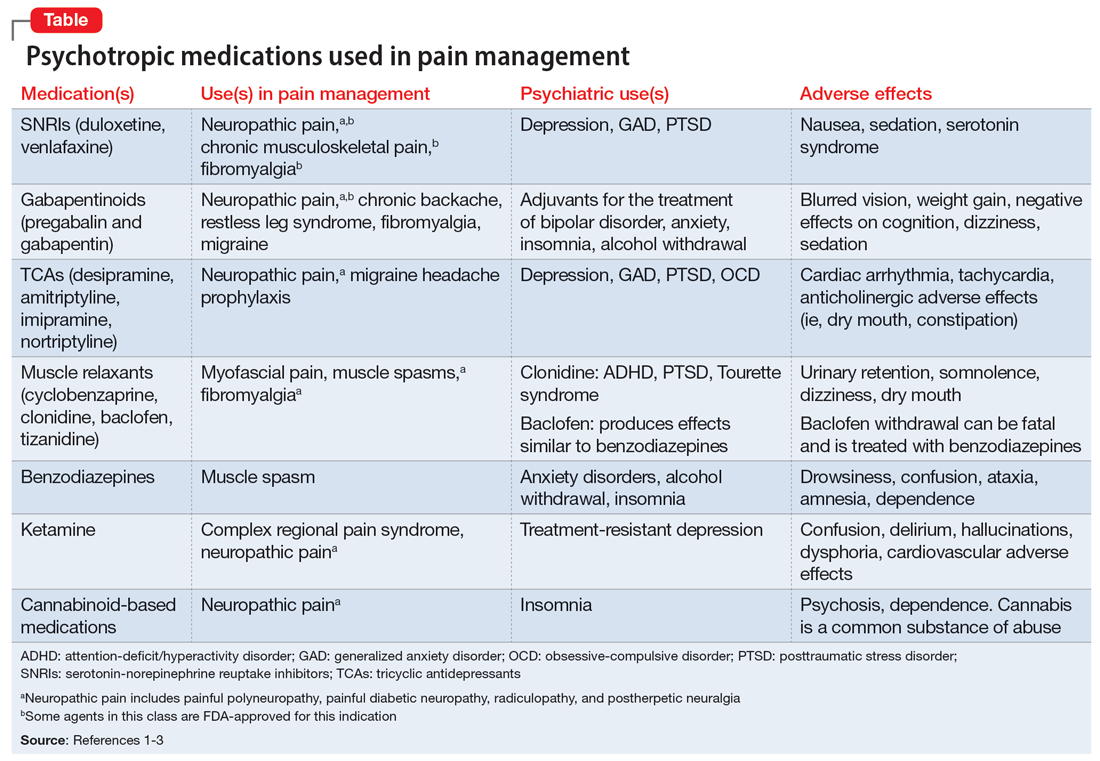

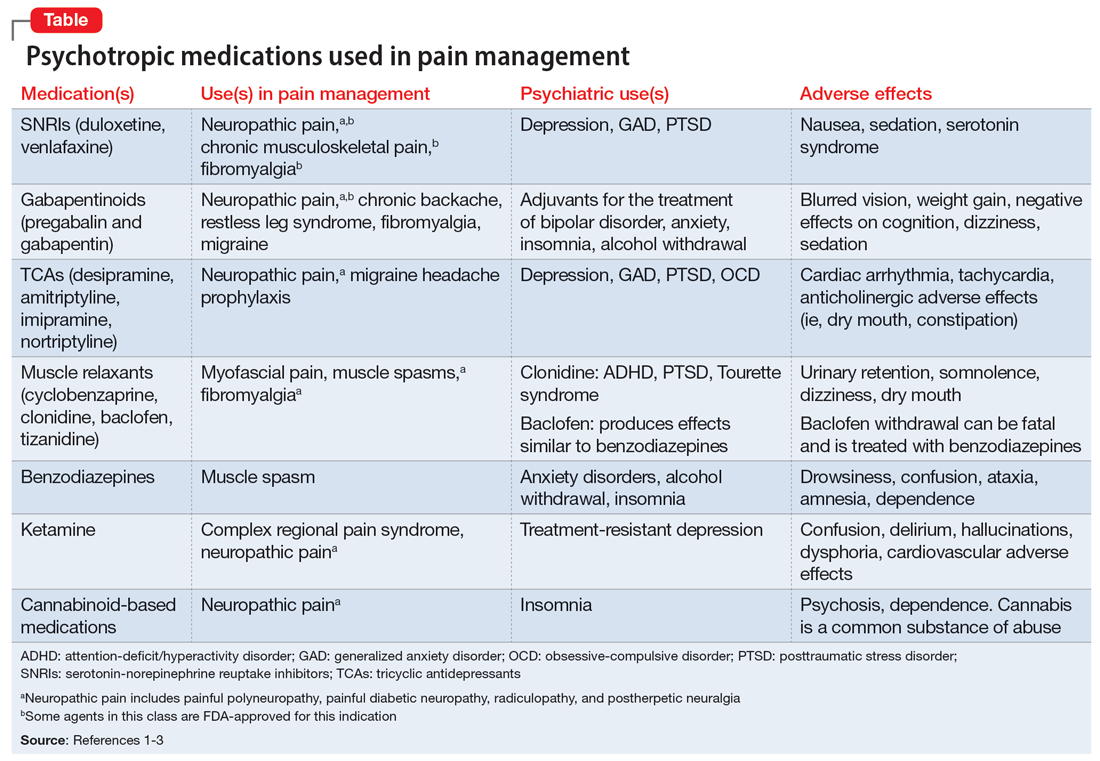

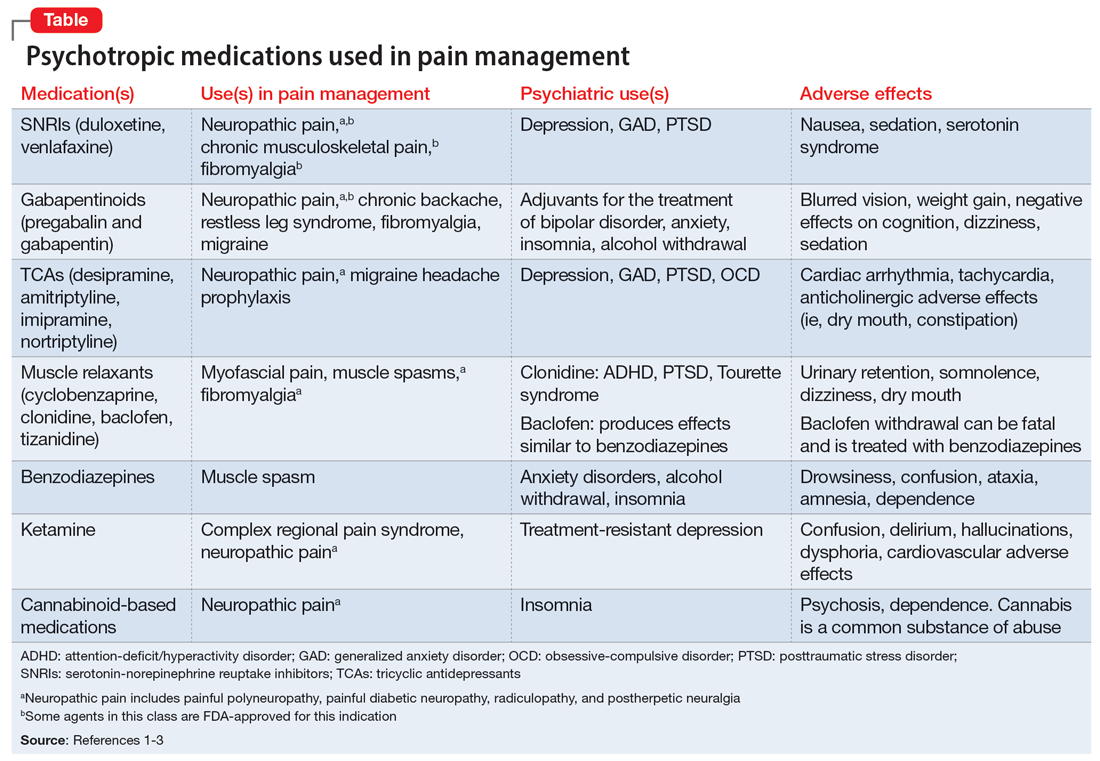

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.