User login

Use psychoeducational family therapy to help families cope with autism

Treating a family in crisis because of a difficult-to-manage family member with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be overwhelming. The family often is desperate and exhausted and, therefore, can be overly needy, demanding, and disorganized. Psychiatrists often are asked to intervene with medication, even though there are no drugs to treat core symptoms of ASD. At best, medication can ease associated symptoms, such as insomnia. However, when coupled with reasonable medication management, psychoeducational family therapy can be an effective, powerful intervention during initial and follow-up medication visits.

Families of ASD patients often show dysfunctional patterns: poor interpersonal and generational boundaries, closed family systems, pathological triangulations, fused and disengaged relationships, resentments, etc. It is easy to assume that an autistic patient’s behavior problems are related to these dysfunctional patterns, and these patterns are caused by psychopathology within the family. In the 1970s and 1980s researchers began to challenge this same assumption in families of patients with schizophrenia and found that the illness shaped family patterns, not the reverse. Illness exacerbations could be minimized by teaching families to reduce their expressed emotions. In addition, research clinicians stopped blaming family members and began describing family dysfunction as a “normal response” to severe psychiatric illness.1

Families of autistic individuals should learn to avoid coercive patterns and clarify interpersonal boundaries. Family members also should understand that dysfunctional patterns are a normal response to illness, these patterns can be corrected, and the correction can lead to improved management of ASD.

Psychoeducational family therapy provides an excellent framework for this family-psychiatrist interaction. Time-consuming, complex, expressive family therapies are not recommended because they tend to heighten expressed emotions.

Consider the following tips when providing psychoeducational family therapy:

• Remember that the extreme stress these families experience is based in reality. Lower functioning ASD patients might not sleep, require constant supervision, and cannot tolerate even minor frustrations.

• Respect the family’s ego defenses as a normal response to stress. Expect to feel some initial frustration and anxiety when working with overwhelmed families.

• Normalize negative feelings within the family. Everyone goes through anger, grief, and hopelessness when handling such a stressful situation.

• Avoid blaming dysfunctional patterns on individuals. Dysfunctional behavior is a normal response to the stress of caring for a family member with ASD.

• Empower the family. Remind the family that they know the patient best, so help them to find their own solutions to behavioral problems.

• Focus on the basics including establishing normal sleeping patterns and regular household routines.

• Educate the family about low sensory stimulation in the home. ASD patients are easily overwhelmed by sensory stimulation which can lead to lower frustration tolerance.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Nichols MP. Family therapy: concepts and methods. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2006.

Treating a family in crisis because of a difficult-to-manage family member with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be overwhelming. The family often is desperate and exhausted and, therefore, can be overly needy, demanding, and disorganized. Psychiatrists often are asked to intervene with medication, even though there are no drugs to treat core symptoms of ASD. At best, medication can ease associated symptoms, such as insomnia. However, when coupled with reasonable medication management, psychoeducational family therapy can be an effective, powerful intervention during initial and follow-up medication visits.

Families of ASD patients often show dysfunctional patterns: poor interpersonal and generational boundaries, closed family systems, pathological triangulations, fused and disengaged relationships, resentments, etc. It is easy to assume that an autistic patient’s behavior problems are related to these dysfunctional patterns, and these patterns are caused by psychopathology within the family. In the 1970s and 1980s researchers began to challenge this same assumption in families of patients with schizophrenia and found that the illness shaped family patterns, not the reverse. Illness exacerbations could be minimized by teaching families to reduce their expressed emotions. In addition, research clinicians stopped blaming family members and began describing family dysfunction as a “normal response” to severe psychiatric illness.1

Families of autistic individuals should learn to avoid coercive patterns and clarify interpersonal boundaries. Family members also should understand that dysfunctional patterns are a normal response to illness, these patterns can be corrected, and the correction can lead to improved management of ASD.

Psychoeducational family therapy provides an excellent framework for this family-psychiatrist interaction. Time-consuming, complex, expressive family therapies are not recommended because they tend to heighten expressed emotions.

Consider the following tips when providing psychoeducational family therapy:

• Remember that the extreme stress these families experience is based in reality. Lower functioning ASD patients might not sleep, require constant supervision, and cannot tolerate even minor frustrations.

• Respect the family’s ego defenses as a normal response to stress. Expect to feel some initial frustration and anxiety when working with overwhelmed families.

• Normalize negative feelings within the family. Everyone goes through anger, grief, and hopelessness when handling such a stressful situation.

• Avoid blaming dysfunctional patterns on individuals. Dysfunctional behavior is a normal response to the stress of caring for a family member with ASD.

• Empower the family. Remind the family that they know the patient best, so help them to find their own solutions to behavioral problems.

• Focus on the basics including establishing normal sleeping patterns and regular household routines.

• Educate the family about low sensory stimulation in the home. ASD patients are easily overwhelmed by sensory stimulation which can lead to lower frustration tolerance.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Treating a family in crisis because of a difficult-to-manage family member with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be overwhelming. The family often is desperate and exhausted and, therefore, can be overly needy, demanding, and disorganized. Psychiatrists often are asked to intervene with medication, even though there are no drugs to treat core symptoms of ASD. At best, medication can ease associated symptoms, such as insomnia. However, when coupled with reasonable medication management, psychoeducational family therapy can be an effective, powerful intervention during initial and follow-up medication visits.

Families of ASD patients often show dysfunctional patterns: poor interpersonal and generational boundaries, closed family systems, pathological triangulations, fused and disengaged relationships, resentments, etc. It is easy to assume that an autistic patient’s behavior problems are related to these dysfunctional patterns, and these patterns are caused by psychopathology within the family. In the 1970s and 1980s researchers began to challenge this same assumption in families of patients with schizophrenia and found that the illness shaped family patterns, not the reverse. Illness exacerbations could be minimized by teaching families to reduce their expressed emotions. In addition, research clinicians stopped blaming family members and began describing family dysfunction as a “normal response” to severe psychiatric illness.1

Families of autistic individuals should learn to avoid coercive patterns and clarify interpersonal boundaries. Family members also should understand that dysfunctional patterns are a normal response to illness, these patterns can be corrected, and the correction can lead to improved management of ASD.

Psychoeducational family therapy provides an excellent framework for this family-psychiatrist interaction. Time-consuming, complex, expressive family therapies are not recommended because they tend to heighten expressed emotions.

Consider the following tips when providing psychoeducational family therapy:

• Remember that the extreme stress these families experience is based in reality. Lower functioning ASD patients might not sleep, require constant supervision, and cannot tolerate even minor frustrations.

• Respect the family’s ego defenses as a normal response to stress. Expect to feel some initial frustration and anxiety when working with overwhelmed families.

• Normalize negative feelings within the family. Everyone goes through anger, grief, and hopelessness when handling such a stressful situation.

• Avoid blaming dysfunctional patterns on individuals. Dysfunctional behavior is a normal response to the stress of caring for a family member with ASD.

• Empower the family. Remind the family that they know the patient best, so help them to find their own solutions to behavioral problems.

• Focus on the basics including establishing normal sleeping patterns and regular household routines.

• Educate the family about low sensory stimulation in the home. ASD patients are easily overwhelmed by sensory stimulation which can lead to lower frustration tolerance.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Nichols MP. Family therapy: concepts and methods. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2006.

Reference

1. Nichols MP. Family therapy: concepts and methods. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2006.

Educate patients about proper disposal of unused Rx medications—for their safety

Patients often tell clinicians that they used their “left-over” medications from previous refills, or that a family member shared medication with them. Other patients, who are non-adherent or have had a recent medication change, might reveal that they have some unused pills at home. As clinicians, what does this practice by our patients mean for us?

Prescription drug abuse is an emerging crisis, and drug diversion is a significant contributing factor.1 According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health,2 in 2011 and 2012, on average, more than one-half of participants age ≥12 who used a pain reliever, tranquilizer, stimulant, or sedative non-medically obtained their most recently used drug “from a friend or relative for free.”

Unused, expired, and “extra” medications pose a significant risk for diversion, abuse, and accidental overdose.3 According to the Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan,1 proper medication disposal is a major problem that needs action to help reduce prescription drug abuse.

Regrettably, <20% of patients receive advice on medication disposal from their health care provider,4 even though clinicians have an opportunity to educate patients and their caregivers on appropriate use, and safe disposal of, medications—in particular, controlled substances.

What should we emphasize to our patients about disposing of medications when it’s necessary?

Teach responsible use

Stress that medications prescribed for the patient are for his (her) use alone and should not be shared with friends or family. Sharing might seem kind and generous, but it can be dangerous. Medications should be used only at the prescribed dosage and frequency and for the recommended duration. If the medication causes an adverse effect or other problem, instruct the patient to talk to you before making any changes to the established regimen.

Emphasize safe disposal

Follow instructions. The label on medication bottles or other containers often has specific instructions on how to properly store, and even dispose of, the drug. Advise your patient to follow instructions on the label carefully.

Participate in a take-back program. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) sponsors several kinds of drug take-back programs, including permanent locations where unused prescriptions are collected; 1-day events; and mail-in/ship-back programs.

The National Prescription Drug Take-Back Initiative is one such program that collects unused or expired medications on “Take Back Days.” On such days, DEA-coordinated collection sites nationwide accept unneeded pills, including prescription painkillers and other controlled substances, for disposal only when law enforcement personnel are present. In 2014, this program collected 780,158 lb of prescribed controlled medications.5

Patients can get more information about these programs by contacting a local pharmacy or their household trash and recycling service division.1,6

Discard medications properly in trash. An acceptable household strategy for disposing of prescription drugs is to mix the medication with an undesirable substance, such as used cat litter or coffee grounds, place the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or disposable container with a lid, and then place it in the trash.

Don’t flush. People sometimes flush unused medications down the toilet or drain. The current recommendation is against flushing unless instructions on the bottle specifically say to do so. Flushing is appropriate for disposing of some medications such as opiates, thereby minimizing the risk of accidental overdose or misuse.6 It is important to remember that most municipal sewage treatment plans do not have the ability to extract pharmaceuticals from wastewater.7

Discard empty bottles. It is important to discard pill bottles once they are empty and to remove any identifiable personal information from the label. Educate patients not to use empty pill bottles to store or transport other medications; this practice might result in accidental ingestion of the wrong medication or dose.These methods of disposal are in accordance with federal, state, and local regulations, as well as human and environmental safety standards. Appropriate disposal decreases contamination of soil and bodies of water with active pharmaceutical ingredients, thereby minimizing people’s and aquatic animals’ chronic exposure to low levels of drugs.3

Encourage patients to seek drug safety information. Patients might benefit from the information and services provided by:

• National Council on Patient Information and Education (www.talkaboutrx.org)

• Medication Use Safety Training for Seniors (www.mustforseniors.org), a nationwide initiative to promote medication education and safety in the geriatric population through an interactive program.

Remember: Although prescribing medications is strictly regulated, particularly for controlled substances, those regulations do little to prevent diversion of medications after they’ve been prescribed. Educating patients and their caregivers about safe disposal can help protect them, their family, and others.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Epidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ ondcp/issues-content/prescription-drugs/rx_abuse_plan. pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 29, 2015.

2. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings and detailed tables. http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/ NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/Index.aspx. Updated October 12, 2013. Accessed February 12, 2015.

3. Daughton CG, Ruhoy IS. Green pharmacy and pharmEcovigilance: prescribing and the planet. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(2):211-232.

4. Seehusen DA, Edwards J. Patient practices and beliefs concerning disposal of medications. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):542-547.

5. DEA’S National Prescription Drug Take-Back Days meet a growing need for Americans. Drug Enforcement Administration. http://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2014/ hq050814.shtml. Published May 8, 2014. Accessed January 29, 2015.

6. How to dispose of unused medicines. FDA Consumer Health Information. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsing MedicineSafely/UnderstandingOver-the-Counter Medicines/ucm107163.pdf. Published April 2011. Accessed January 29, 2015.

7. Herring ME, Shah SK, Shah SK, et al. Current regulations and modest proposals regarding disposal of unused opioids and other controlled substances. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008;108(7):338-343.

Back Initiative, Take Back Days, discard medications

Patients often tell clinicians that they used their “left-over” medications from previous refills, or that a family member shared medication with them. Other patients, who are non-adherent or have had a recent medication change, might reveal that they have some unused pills at home. As clinicians, what does this practice by our patients mean for us?

Prescription drug abuse is an emerging crisis, and drug diversion is a significant contributing factor.1 According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health,2 in 2011 and 2012, on average, more than one-half of participants age ≥12 who used a pain reliever, tranquilizer, stimulant, or sedative non-medically obtained their most recently used drug “from a friend or relative for free.”

Unused, expired, and “extra” medications pose a significant risk for diversion, abuse, and accidental overdose.3 According to the Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan,1 proper medication disposal is a major problem that needs action to help reduce prescription drug abuse.

Regrettably, <20% of patients receive advice on medication disposal from their health care provider,4 even though clinicians have an opportunity to educate patients and their caregivers on appropriate use, and safe disposal of, medications—in particular, controlled substances.

What should we emphasize to our patients about disposing of medications when it’s necessary?

Teach responsible use

Stress that medications prescribed for the patient are for his (her) use alone and should not be shared with friends or family. Sharing might seem kind and generous, but it can be dangerous. Medications should be used only at the prescribed dosage and frequency and for the recommended duration. If the medication causes an adverse effect or other problem, instruct the patient to talk to you before making any changes to the established regimen.

Emphasize safe disposal

Follow instructions. The label on medication bottles or other containers often has specific instructions on how to properly store, and even dispose of, the drug. Advise your patient to follow instructions on the label carefully.

Participate in a take-back program. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) sponsors several kinds of drug take-back programs, including permanent locations where unused prescriptions are collected; 1-day events; and mail-in/ship-back programs.

The National Prescription Drug Take-Back Initiative is one such program that collects unused or expired medications on “Take Back Days.” On such days, DEA-coordinated collection sites nationwide accept unneeded pills, including prescription painkillers and other controlled substances, for disposal only when law enforcement personnel are present. In 2014, this program collected 780,158 lb of prescribed controlled medications.5

Patients can get more information about these programs by contacting a local pharmacy or their household trash and recycling service division.1,6

Discard medications properly in trash. An acceptable household strategy for disposing of prescription drugs is to mix the medication with an undesirable substance, such as used cat litter or coffee grounds, place the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or disposable container with a lid, and then place it in the trash.

Don’t flush. People sometimes flush unused medications down the toilet or drain. The current recommendation is against flushing unless instructions on the bottle specifically say to do so. Flushing is appropriate for disposing of some medications such as opiates, thereby minimizing the risk of accidental overdose or misuse.6 It is important to remember that most municipal sewage treatment plans do not have the ability to extract pharmaceuticals from wastewater.7

Discard empty bottles. It is important to discard pill bottles once they are empty and to remove any identifiable personal information from the label. Educate patients not to use empty pill bottles to store or transport other medications; this practice might result in accidental ingestion of the wrong medication or dose.These methods of disposal are in accordance with federal, state, and local regulations, as well as human and environmental safety standards. Appropriate disposal decreases contamination of soil and bodies of water with active pharmaceutical ingredients, thereby minimizing people’s and aquatic animals’ chronic exposure to low levels of drugs.3

Encourage patients to seek drug safety information. Patients might benefit from the information and services provided by:

• National Council on Patient Information and Education (www.talkaboutrx.org)

• Medication Use Safety Training for Seniors (www.mustforseniors.org), a nationwide initiative to promote medication education and safety in the geriatric population through an interactive program.

Remember: Although prescribing medications is strictly regulated, particularly for controlled substances, those regulations do little to prevent diversion of medications after they’ve been prescribed. Educating patients and their caregivers about safe disposal can help protect them, their family, and others.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Patients often tell clinicians that they used their “left-over” medications from previous refills, or that a family member shared medication with them. Other patients, who are non-adherent or have had a recent medication change, might reveal that they have some unused pills at home. As clinicians, what does this practice by our patients mean for us?

Prescription drug abuse is an emerging crisis, and drug diversion is a significant contributing factor.1 According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health,2 in 2011 and 2012, on average, more than one-half of participants age ≥12 who used a pain reliever, tranquilizer, stimulant, or sedative non-medically obtained their most recently used drug “from a friend or relative for free.”

Unused, expired, and “extra” medications pose a significant risk for diversion, abuse, and accidental overdose.3 According to the Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan,1 proper medication disposal is a major problem that needs action to help reduce prescription drug abuse.

Regrettably, <20% of patients receive advice on medication disposal from their health care provider,4 even though clinicians have an opportunity to educate patients and their caregivers on appropriate use, and safe disposal of, medications—in particular, controlled substances.

What should we emphasize to our patients about disposing of medications when it’s necessary?

Teach responsible use

Stress that medications prescribed for the patient are for his (her) use alone and should not be shared with friends or family. Sharing might seem kind and generous, but it can be dangerous. Medications should be used only at the prescribed dosage and frequency and for the recommended duration. If the medication causes an adverse effect or other problem, instruct the patient to talk to you before making any changes to the established regimen.

Emphasize safe disposal

Follow instructions. The label on medication bottles or other containers often has specific instructions on how to properly store, and even dispose of, the drug. Advise your patient to follow instructions on the label carefully.

Participate in a take-back program. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) sponsors several kinds of drug take-back programs, including permanent locations where unused prescriptions are collected; 1-day events; and mail-in/ship-back programs.

The National Prescription Drug Take-Back Initiative is one such program that collects unused or expired medications on “Take Back Days.” On such days, DEA-coordinated collection sites nationwide accept unneeded pills, including prescription painkillers and other controlled substances, for disposal only when law enforcement personnel are present. In 2014, this program collected 780,158 lb of prescribed controlled medications.5

Patients can get more information about these programs by contacting a local pharmacy or their household trash and recycling service division.1,6

Discard medications properly in trash. An acceptable household strategy for disposing of prescription drugs is to mix the medication with an undesirable substance, such as used cat litter or coffee grounds, place the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or disposable container with a lid, and then place it in the trash.

Don’t flush. People sometimes flush unused medications down the toilet or drain. The current recommendation is against flushing unless instructions on the bottle specifically say to do so. Flushing is appropriate for disposing of some medications such as opiates, thereby minimizing the risk of accidental overdose or misuse.6 It is important to remember that most municipal sewage treatment plans do not have the ability to extract pharmaceuticals from wastewater.7

Discard empty bottles. It is important to discard pill bottles once they are empty and to remove any identifiable personal information from the label. Educate patients not to use empty pill bottles to store or transport other medications; this practice might result in accidental ingestion of the wrong medication or dose.These methods of disposal are in accordance with federal, state, and local regulations, as well as human and environmental safety standards. Appropriate disposal decreases contamination of soil and bodies of water with active pharmaceutical ingredients, thereby minimizing people’s and aquatic animals’ chronic exposure to low levels of drugs.3

Encourage patients to seek drug safety information. Patients might benefit from the information and services provided by:

• National Council on Patient Information and Education (www.talkaboutrx.org)

• Medication Use Safety Training for Seniors (www.mustforseniors.org), a nationwide initiative to promote medication education and safety in the geriatric population through an interactive program.

Remember: Although prescribing medications is strictly regulated, particularly for controlled substances, those regulations do little to prevent diversion of medications after they’ve been prescribed. Educating patients and their caregivers about safe disposal can help protect them, their family, and others.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Epidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ ondcp/issues-content/prescription-drugs/rx_abuse_plan. pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 29, 2015.

2. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings and detailed tables. http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/ NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/Index.aspx. Updated October 12, 2013. Accessed February 12, 2015.

3. Daughton CG, Ruhoy IS. Green pharmacy and pharmEcovigilance: prescribing and the planet. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(2):211-232.

4. Seehusen DA, Edwards J. Patient practices and beliefs concerning disposal of medications. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):542-547.

5. DEA’S National Prescription Drug Take-Back Days meet a growing need for Americans. Drug Enforcement Administration. http://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2014/ hq050814.shtml. Published May 8, 2014. Accessed January 29, 2015.

6. How to dispose of unused medicines. FDA Consumer Health Information. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsing MedicineSafely/UnderstandingOver-the-Counter Medicines/ucm107163.pdf. Published April 2011. Accessed January 29, 2015.

7. Herring ME, Shah SK, Shah SK, et al. Current regulations and modest proposals regarding disposal of unused opioids and other controlled substances. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008;108(7):338-343.

1. Epidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ ondcp/issues-content/prescription-drugs/rx_abuse_plan. pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 29, 2015.

2. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings and detailed tables. http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/ NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/Index.aspx. Updated October 12, 2013. Accessed February 12, 2015.

3. Daughton CG, Ruhoy IS. Green pharmacy and pharmEcovigilance: prescribing and the planet. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(2):211-232.

4. Seehusen DA, Edwards J. Patient practices and beliefs concerning disposal of medications. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):542-547.

5. DEA’S National Prescription Drug Take-Back Days meet a growing need for Americans. Drug Enforcement Administration. http://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2014/ hq050814.shtml. Published May 8, 2014. Accessed January 29, 2015.

6. How to dispose of unused medicines. FDA Consumer Health Information. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsing MedicineSafely/UnderstandingOver-the-Counter Medicines/ucm107163.pdf. Published April 2011. Accessed January 29, 2015.

7. Herring ME, Shah SK, Shah SK, et al. Current regulations and modest proposals regarding disposal of unused opioids and other controlled substances. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008;108(7):338-343.

Back Initiative, Take Back Days, discard medications

Back Initiative, Take Back Days, discard medications

Cloud-based systems can help secure patient information

Physicians hardly need the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to remind them how important it is to safeguard their patients’ records. Physicians understand that patient information is sensitive and it would be disastrous if their files became public or fell into the wrong hands. However, the use of health information technology to record patient information, although beneficial for medical professionals and patients, poses risks to patient privacy.1

HIPAA requires clinicians and health care systems to protect patient information, whether it is maintained in an electronic health records system, stored on a mobile device, or transmitted via e-mail to another physician. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will increase HIPAA audits this year to make sure that medical practices have taken measures to protect their patients’ health information. Physicians and other clinicians can take advantage of cloud-based file-sharing services, such as Dropbox, without running afoul of HIPAA.

Mobile computing, the cloud, and patient information: A risky combination

Although mobile computing and cloud-based file-sharing sites such as Dropbox and Google Drive allow physicians to take notes on a tablet, annotate those notes on a laptop, and share them with a physician who views them on his (her) desktop, this free flow of information makes it more difficult to stay compliant with HIPAA.

Dropbox and other file-sharing services encrypt documents while they’re stored in the cloud but the files are unprotected when downloaded to a device. E-mail, which isn’t as versatile or useful as these services, also is not HIPAA-compliant unless the files are encrypted.

Often, small psychiatric practices use these online services and e-mail even if they’re aware of the risks because they don’t have time to research a better solution. Or they might resort to faxing or even snail-mailing documents, losing out on the increased productivity that the cloud can provide.

Secure technologies satisfy auditors

A number of tools exist to help physicians seamlessly integrate the encryption necessary to keep their patients’ records safe and meet HIPAA security requirements. Here’s a look at 3 options.

Sookasa (plus Dropbox). One option is to invest in a software product designed to encrypt documents shared through cloud-based services. This type of software creates a compliance “shield” around files stored on the cloud, converting files into HIPAA safe havens. The files are encrypted when synced to new devices or shared with other users, meaning they’re protected no matter where they reside.2

Sookasa is an online service that encrypts files shared and stored in Dropbox. The company plans to extend its support to other popular cloud services such as Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive. Sookasa also audits and controls access to encrypted files, so that patient data can be blocked even if a device is lost or sto len. Sookasa users also can share files via e-mail with added encryption and authentication to make sure only the authorized receiver gets the documents.2

TigerText. Regular SMS text messages on your mobile phone aren’t compliant with HIPAA, but TigerText replicates the texting experience in a secure way. Instead of being stored on your mobile phone, messages sent through TigerText are stored on the company’s servers. Messages sent through the application can’t be saved, copied, or forwarded to other recipients. TigerText messages also are deleted, either after a set time period or after they’ve been read. Because the messages aren’t stored on phones, a lost or stolen phone won’t result in a data breach and a HIPAA violation.3

Secure text messaging won’t help physicians store and manage large amounts of patient files, but it’s a must-have if they use texting to communicate about patient care.

DataMotion SecureMail provides e-mail encryption services to health care organizations and other enterprises. Using a decryption key, authorized users can open and read the encrypted e-mails, which are HIPAA-compliant.4 This method is superior to other services that encrypt e-mails on the server. Several providers, such as Google’s e-mail encryption service Postini, ensure that e-mails are encrypted when they are stored on the server; however, the body text and attachments included in specific e-mails are not encrypted on the senders’ and receivers’ devices. If you lose a connected device, you would still be at risk of a HIPAA breach.

DataMotion’s SecureMail provides detailed tracking and logging of e-mails, which is necessary for auditing purposes. The product also works on mobile devices.

E-mail is a helpful tool for quickly sharing files and an e-mail encryption product such as SecureMail makes it possible to do so securely. Other e-mail encryption products do not securely store and back up all files in a centralized way.

DisclosureDr. Cidon is CEO and Co-founder of Sookasa.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HIPAA privacy, security, and breach notification adult program. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/ audit. Accessed February 12, 2015.

2. Sookasa Web site. How it works. https://www.sookasa. com/how-it-works. Accessed February 12, 2015.

3. TigerText Web site. http://www.tigertext.com. Accessed February 12, 2015.

4. DataMotion Web site. http://datamotion.com/products/ securemail/securemail-desktop. Accessed February 12, 2015.

Physicians hardly need the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to remind them how important it is to safeguard their patients’ records. Physicians understand that patient information is sensitive and it would be disastrous if their files became public or fell into the wrong hands. However, the use of health information technology to record patient information, although beneficial for medical professionals and patients, poses risks to patient privacy.1

HIPAA requires clinicians and health care systems to protect patient information, whether it is maintained in an electronic health records system, stored on a mobile device, or transmitted via e-mail to another physician. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will increase HIPAA audits this year to make sure that medical practices have taken measures to protect their patients’ health information. Physicians and other clinicians can take advantage of cloud-based file-sharing services, such as Dropbox, without running afoul of HIPAA.

Mobile computing, the cloud, and patient information: A risky combination

Although mobile computing and cloud-based file-sharing sites such as Dropbox and Google Drive allow physicians to take notes on a tablet, annotate those notes on a laptop, and share them with a physician who views them on his (her) desktop, this free flow of information makes it more difficult to stay compliant with HIPAA.

Dropbox and other file-sharing services encrypt documents while they’re stored in the cloud but the files are unprotected when downloaded to a device. E-mail, which isn’t as versatile or useful as these services, also is not HIPAA-compliant unless the files are encrypted.

Often, small psychiatric practices use these online services and e-mail even if they’re aware of the risks because they don’t have time to research a better solution. Or they might resort to faxing or even snail-mailing documents, losing out on the increased productivity that the cloud can provide.

Secure technologies satisfy auditors

A number of tools exist to help physicians seamlessly integrate the encryption necessary to keep their patients’ records safe and meet HIPAA security requirements. Here’s a look at 3 options.

Sookasa (plus Dropbox). One option is to invest in a software product designed to encrypt documents shared through cloud-based services. This type of software creates a compliance “shield” around files stored on the cloud, converting files into HIPAA safe havens. The files are encrypted when synced to new devices or shared with other users, meaning they’re protected no matter where they reside.2

Sookasa is an online service that encrypts files shared and stored in Dropbox. The company plans to extend its support to other popular cloud services such as Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive. Sookasa also audits and controls access to encrypted files, so that patient data can be blocked even if a device is lost or sto len. Sookasa users also can share files via e-mail with added encryption and authentication to make sure only the authorized receiver gets the documents.2

TigerText. Regular SMS text messages on your mobile phone aren’t compliant with HIPAA, but TigerText replicates the texting experience in a secure way. Instead of being stored on your mobile phone, messages sent through TigerText are stored on the company’s servers. Messages sent through the application can’t be saved, copied, or forwarded to other recipients. TigerText messages also are deleted, either after a set time period or after they’ve been read. Because the messages aren’t stored on phones, a lost or stolen phone won’t result in a data breach and a HIPAA violation.3

Secure text messaging won’t help physicians store and manage large amounts of patient files, but it’s a must-have if they use texting to communicate about patient care.

DataMotion SecureMail provides e-mail encryption services to health care organizations and other enterprises. Using a decryption key, authorized users can open and read the encrypted e-mails, which are HIPAA-compliant.4 This method is superior to other services that encrypt e-mails on the server. Several providers, such as Google’s e-mail encryption service Postini, ensure that e-mails are encrypted when they are stored on the server; however, the body text and attachments included in specific e-mails are not encrypted on the senders’ and receivers’ devices. If you lose a connected device, you would still be at risk of a HIPAA breach.

DataMotion’s SecureMail provides detailed tracking and logging of e-mails, which is necessary for auditing purposes. The product also works on mobile devices.

E-mail is a helpful tool for quickly sharing files and an e-mail encryption product such as SecureMail makes it possible to do so securely. Other e-mail encryption products do not securely store and back up all files in a centralized way.

DisclosureDr. Cidon is CEO and Co-founder of Sookasa.

Physicians hardly need the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to remind them how important it is to safeguard their patients’ records. Physicians understand that patient information is sensitive and it would be disastrous if their files became public or fell into the wrong hands. However, the use of health information technology to record patient information, although beneficial for medical professionals and patients, poses risks to patient privacy.1

HIPAA requires clinicians and health care systems to protect patient information, whether it is maintained in an electronic health records system, stored on a mobile device, or transmitted via e-mail to another physician. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will increase HIPAA audits this year to make sure that medical practices have taken measures to protect their patients’ health information. Physicians and other clinicians can take advantage of cloud-based file-sharing services, such as Dropbox, without running afoul of HIPAA.

Mobile computing, the cloud, and patient information: A risky combination

Although mobile computing and cloud-based file-sharing sites such as Dropbox and Google Drive allow physicians to take notes on a tablet, annotate those notes on a laptop, and share them with a physician who views them on his (her) desktop, this free flow of information makes it more difficult to stay compliant with HIPAA.

Dropbox and other file-sharing services encrypt documents while they’re stored in the cloud but the files are unprotected when downloaded to a device. E-mail, which isn’t as versatile or useful as these services, also is not HIPAA-compliant unless the files are encrypted.

Often, small psychiatric practices use these online services and e-mail even if they’re aware of the risks because they don’t have time to research a better solution. Or they might resort to faxing or even snail-mailing documents, losing out on the increased productivity that the cloud can provide.

Secure technologies satisfy auditors

A number of tools exist to help physicians seamlessly integrate the encryption necessary to keep their patients’ records safe and meet HIPAA security requirements. Here’s a look at 3 options.

Sookasa (plus Dropbox). One option is to invest in a software product designed to encrypt documents shared through cloud-based services. This type of software creates a compliance “shield” around files stored on the cloud, converting files into HIPAA safe havens. The files are encrypted when synced to new devices or shared with other users, meaning they’re protected no matter where they reside.2

Sookasa is an online service that encrypts files shared and stored in Dropbox. The company plans to extend its support to other popular cloud services such as Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive. Sookasa also audits and controls access to encrypted files, so that patient data can be blocked even if a device is lost or sto len. Sookasa users also can share files via e-mail with added encryption and authentication to make sure only the authorized receiver gets the documents.2

TigerText. Regular SMS text messages on your mobile phone aren’t compliant with HIPAA, but TigerText replicates the texting experience in a secure way. Instead of being stored on your mobile phone, messages sent through TigerText are stored on the company’s servers. Messages sent through the application can’t be saved, copied, or forwarded to other recipients. TigerText messages also are deleted, either after a set time period or after they’ve been read. Because the messages aren’t stored on phones, a lost or stolen phone won’t result in a data breach and a HIPAA violation.3

Secure text messaging won’t help physicians store and manage large amounts of patient files, but it’s a must-have if they use texting to communicate about patient care.

DataMotion SecureMail provides e-mail encryption services to health care organizations and other enterprises. Using a decryption key, authorized users can open and read the encrypted e-mails, which are HIPAA-compliant.4 This method is superior to other services that encrypt e-mails on the server. Several providers, such as Google’s e-mail encryption service Postini, ensure that e-mails are encrypted when they are stored on the server; however, the body text and attachments included in specific e-mails are not encrypted on the senders’ and receivers’ devices. If you lose a connected device, you would still be at risk of a HIPAA breach.

DataMotion’s SecureMail provides detailed tracking and logging of e-mails, which is necessary for auditing purposes. The product also works on mobile devices.

E-mail is a helpful tool for quickly sharing files and an e-mail encryption product such as SecureMail makes it possible to do so securely. Other e-mail encryption products do not securely store and back up all files in a centralized way.

DisclosureDr. Cidon is CEO and Co-founder of Sookasa.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HIPAA privacy, security, and breach notification adult program. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/ audit. Accessed February 12, 2015.

2. Sookasa Web site. How it works. https://www.sookasa. com/how-it-works. Accessed February 12, 2015.

3. TigerText Web site. http://www.tigertext.com. Accessed February 12, 2015.

4. DataMotion Web site. http://datamotion.com/products/ securemail/securemail-desktop. Accessed February 12, 2015.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HIPAA privacy, security, and breach notification adult program. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/ audit. Accessed February 12, 2015.

2. Sookasa Web site. How it works. https://www.sookasa. com/how-it-works. Accessed February 12, 2015.

3. TigerText Web site. http://www.tigertext.com. Accessed February 12, 2015.

4. DataMotion Web site. http://datamotion.com/products/ securemail/securemail-desktop. Accessed February 12, 2015.

Abnormal calcium level in a psychiatric presentation? Rule out parathyroid disease

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

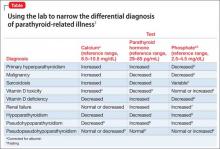

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In some patients, symptoms of depression, psychosis, delirium, or dementia exist concomitantly with, or as a result of, an abnormal (elevated or low) serum calcium concentration that has been precipitated by an unrecognized endocrinopathy. The apparent psychiatric presentations of such patients might reflect parathyroid pathology—not psychopathology.

Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia often are related to a distinct spectrum of conditions, such as diseases of the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and various neoplasms including malignancies. Be alert to the possibility of parathyroid disease in patients whose presentation suggests mental illness concurrent with, or as a direct consequence of, an abnormal calcium level, and investigate appropriately.

The Table1-9 illustrates how 3 clinical laboratory tests—serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), and phosphate—can narrow the differential diagnosis when the clinical impression is parathyroid-related illness. Seek endocrinology consultation whenever a parathyroid-associated ailment is discovered or suspected. Serum calcium is routinely assayed in hospitalized patients; when managing a patient with treatment-refractory psychiatric illness, (1) always check the reported result of that test and (2) consider measuring PTH.

Case reports1

Case 1: Woman with chronic depression. The patient was hospitalized while suicidal. Serial serum calcium levels were 12.5 mg/dL and 15.8 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The PTH level was elevated at 287 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL).

After thyroid imaging, surgery revealed a parathyroid mass, which was resected. Histologic examination confirmed an adenoma.

The calcium concentration declined to 8.6 mg/dL postoperatively and stabilized at 9.2 mg/dL. Psychiatric symptoms resolved fully; she experienced a complete recovery.

Case 2: Man on long-term lithium maintenance. The patient was admitted in a delusional psychotic state. The serum calcium level was 14.3 mg/dL initially, decreasing to 11.5 mg/dL after lithium was discontinued. The PTH level was elevated at 97 pg/mL at admission, consistent with hyperparathyroidism.

A parathyroid adenoma was resected. Serum calcium level normalized at 10.7 mg/dL; psychosis resolved with striking, sustained improvement in mental status.

Full return to mental, physical health

The diagnosis of parathyroid adenoma in these 2 patients, which began with a psychiatric presentation, was properly made after an abnormal serum calcium level was documented. Surgical treatment of the endocrinopathy produced full remission and a return to normal mental and physical health.

Although psychiatric manifestations are associated with an abnormal serum calcium concentration, the severity of those presentations does not correlate with the degree of abnormality of the calcium level.10

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

1. Velasco PJ, Manshadi M, Breen K, et al. Psychiatric aspects of parathyroid disease. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(6):486-490.

2. Harrop JS, Bailey JE, Woodhead JS. Incidence of hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism in relation to the biochemical profile. J Clin Pathol. 1982; 35(4):395-400.

3. Assadi F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based problem-solving approach to clinical cases. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(3):195-201.

4. Ozkhan B, Hatun S, Bereket A. Vitamin D intoxication. Turk J Pediatr. 2012;54(2):93-98.

5. Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, et al. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33(6):528-533.

6. Geller JL, Adam JS. Vitamin D therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(1):5-11.

7. Albaaj F, Hutchison A. Hyperphosphatemia in renal failure: causes, consequences and current management. Drugs. 2003;63(6):577-596.

8. Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):517-522.

9. Brown H, Englert E, Wallach S. The syndrome of pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1956;98(4):517-524.

10. Pfitzenmeyer P, Besancenot JF, Verges B, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in very old patients. Eur J Med. 1993;2(8):453-456.

How to write a suicide risk assessment that’s clinically sound and legally defensible

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

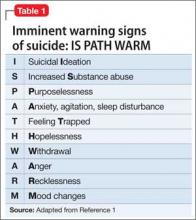

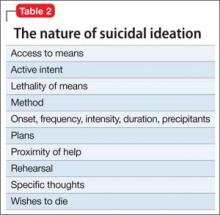

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Suicidologists and legal experts implore clinicians to document their suicide risk assessments (SRAs) thoroughly. It’s difficult, however, to find practical guidance on how to write a clinically sound, legally defensible SRA.

The crux of every SRA is written justification of suicide risk. That justification should reveal your thinking and present a well-reasoned basis for your decision.

Reasoned vs right

It’s more important to provide a justification of suicide risk that’s well-reasoned rather than one that’s right. Suicide is impossible to predict. Instead of prediction, legally we are asked to reasonably anticipate suicide based on clinical facts. In hindsight, especially in the context of a courtroom, decisions might look ill-considered. You need to craft a logical argument, be clear, and avoid jargon.

Convey thoroughness by covering each component of an SRA. Use the mnemonic device CAIPS to help the reader (and you) understand how a conclusion was reached based on the facts of the case.

Chronic and Acute factors. Address the chronic and acute factors that weigh heaviest in your mind. Chronic factors are conditions, past events, and demographics that generally do not change. Acute factors are recent events or conditions that potentially are modifiable. Pay attention to combinations of factors that dramatically elevate risk (eg, previous attempts in the context of acute depression). Avoid repeating every factor, especially when these are documented elsewhere, such as on a checklist.

Imminent warning signs for suicide. Address warning signs (Table 1),1 the nature of current suicidal thoughts (Table 2), and other aspects of mental status (eg, future orientation) that influenced your decision. Use words like “moreover,” “however,” and “in addition” to draw the reader’s attention to the building blocks of your argument.

Protective factors. Discuss the protective factors last; they deserve the least weight because none has been shown to immunize people against suicide. Don’t solely rely on your judgment of what is protective (eg, children in the home). Instead, elicit the patient’s reasons for living and dying. Be concerned if he (she) reports more of the latter.

Summary statement. Make an explicit statement about risk, focusing on imminent risk (ie, the next few hours and days). Avoid a “plot twist,” which is a risk level inconsistent with the preceding evidence, because it suggests an error in judgment. The Box gives an example of a justification that follows the CAIPS method.

Additional tips

Consider these strategies:

• Bolster your argument by explicitly addressing hopelessness (the strongest psychological correlate of suicide); use quotes from the patient that support your decision; refer to consultation with family members and colleagues; and include pertinent negatives to show completeness2 (ie, “denied suicide plans”).

• Critically resolve discrepancies between what the patient says and behavior that suggests suicidal intent (eg, a patient who minimizes suicidal intent but shopped for a gun yesterday).

• Last, while reviewing your justification, imagine that your patient completed suicide after leaving your office and that you are in court for negligence. In our experience, this exercise reveals dangerous errors of judgment. A clear and reasoned justification will reduce the risk of litigation and help you make prudent treatment plans.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

1. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. http://www.suicidology.org/resources/ warning-signs. Accessed February 9, 2014.

2. Ballas C. How to write a suicide note: practical tips for documenting the evaluation of a suicidal patient. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/how-write-suicide-note-practical-tips-documenting-evaluation-suicidal-patient. Published May 1, 2007. Accessed July 29, 2013.

6 Strategies to address risk factors for school violence

School shootings engender the deepest of public concern. They violate strongly held cross-culture beliefs about the sanctity of childhood and the obligation to protect children from harm.

Prevention and intervention approaches to school shootings have emerged (1) in the literature, from case studies, and (2) from discourse among experts.1 Approaches include:

• bolstering security at schools

• reducing the facilities’ vulnerability to intrusion

• increasing the capacity to respond at the moment of threat

• transforming the school climate

• increasing attachment and bonding.1,2

Psychiatrists often are consulted by school districts to provide expertise for the latter 2 approaches. Using the following strategies, you can help address risk factors for school violence.

Strengthen school attachment. Develop curricular and extracurricular programs for students that create, and contribute to, a sense of belonging. This, in turn, decreases alienation and reduces hostility. Unaddressed hostility can lead to depression, anger, and, subsequently, violence.

Reduce social aggression. Social aggression, such as teasing, taunting, humiliating, and bullying, is an important predictor of developmental outcomes in victims and perpetrators.3 Social aggression has been linked to peer victimization and low school attachment. Implement social skills programs, such as Making Choices, which have yielded positive effects on social aggression in elementary school students.4

Break codes of silence. This can involve encouraging schools to:

• develop an anonymous mechanism of voicing concerns

• take diligent action based on students’ concerns

• treat disclosures discreetly.

Establish resources for troubled and rejected students. Develop routine emergency modes of communication, such as a protocol for high-priority referral to mental health resources. These could reduce the likelihood of students acting out against the school.

Recommend that security be enhanced. Establishing the position of school resource officer might increase confidence and decrease feelings of vulnerability among teachers, students, and parents. This can increase the perception of school security, potentially helps school attachment, and promotes breaking down codes of silence.5

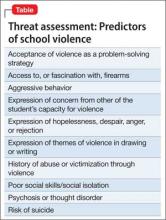

Increase communication within the school, and between the school and law enforcement agencies. Effective communication can help identify the location of an attacker and disrupt a developing event. Create an alert system to notify students, faculty, and parents with an automated text message or phone call during an emergency. Increased accessibility of the students by the school alert system might be a quicker way to reach the school community. Work with security agencies to develop a protocol for communicating and assessing threat potential. Also, develop guidelines to outline referral and assessing procedures for students whose writings may present indication for possible attack or whose class behavior may be alienating or intimidating to either faculty or other students. Behavior that can lead to school violence is outlined in the Table.

You also can educate school administrators about the following:

• School violence has been significantly associated with mental health problems, such as depression and inability to form age appropriate social connections,6 which in combination with extreme social rejection and specific personality-related issues (eg, antisocial personality disorder) can culminate in violent outbreaks.7 Work closely with school nurses and counselors to identify and treat vulnerable students.

• In most multiple-victim incidents, more than 1 person had information about the attack before it occurred that was not communicated to an authority figure. Educate school officials about being sensitive to warnings or threats about possible attack, and help develop ways get counseling for potential attackers.2

• Zero-tolerance policies are ineffective at preventing school shootings, mostly because of literal interpretation and inconsistent implementation of such policies.8 Help circumvent a more stringent zero-tolerance policy with adequate availability of mental health care for students who are identified as being at risk of perpetrating an attack.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Culley MR, Conkling M, Emshoff J, et al. Environmental and contextual influences on school violence and its prevention. J Prim Prev. 2006;27(3):217-227.

2. Wike TL, Fraser MW. School shooting: making sense of the senseless. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(3):162-169.

3. Rudatsikira E, Singh P, Job J, et al. Variables associated with weapon-carrying among young adolescents in southern California. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):470-473.

4. Fraser MW, Galinsky MJ, Smokowski PR, et al. Social information-processing skills training to promote social competence and prevent aggressive behavior in the third grades. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1045-1055.

5. Finn P. School resource officer programs. Finding the funding, reaping the benefits. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 2006;75(8):1-13.

6. Ferguson C, Coulson M, Barnett J. Psychological profiles of school shooters: positive directions and one big wrong turn. J Police Crisis Negot. 2011;11:1-17.

7. Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Smith L, et al. Teasing, rejection and violence: case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(3):202-214.

8. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: an evidentiary review and recommendation. Am Psychol. 2008;63(9):852-862.