User login

The Socrates Project for Difficult Diagnosis at Northwestern Medicine

Internists are experts in general medicine, skilled at mapping the few hundred ways the human body can go awry onto thousands of diagnoses, and managing the uncertainty inherent in that process. Generalists, almost by definition, consult specialists with their specialty-focused questions; but who does one call for a general consultation about diagnosis if a specific diagnosis remains elusive and the pathology does not fit cleanly into the purview of a consultant? Outside of sage advice from colleagues (usually senior), most medical centers lack a consultation service focused on diagnosis. There is no oracle to seek. In this perspective, we describe our institution’s answer to this problem: the creation of a service for difficult diagnosis based on Socratic principles, particularly the role of iterative hypothesis testing in the process of diagnosis.1

In 2015, Northwestern Medicine began the Socrates Project, a physician-to-physician consultation service that assists doctors working to diagnose conditions that have so far eluded detection. Our service’s goal is to improve patient care by providing an opinion to the referring physician on diagnostic possibilities for a particular case and ideas to reduce—or at least manage—diagnostic uncertainty.

Most patients referred to the Socrates Project have already undergone an extensive evaluation at top medical centers by experienced clinicians. It would be hubris to assume that we will find a definitive diagnosis in every case; indeed, because of the types of cases referred to our group, it is rare that we find a “Eureka!” diagnosis. When a colleague consults our group, we under-promise in hopes of over-delivering. Instead, we convey to referring physicians that we will conduct a thorough case review and explain our thinking in hopes of uncovering an additional diagnostic avenue, even if that avenue does not ultimately lead to a definitive diagnosis. In addition, the Socrates Project often serves as a broker between consulting services that are deadlocked because of differing diagnostic opinions. We also assist with cases in which a functional disorder is suspected, yet the referring physician is hesitant to diagnose a patient with such a disorder out of concern about missing an important (and possibly obscure) diagnosis.

PERSONNEL AND PROCESS

The Socrates Project receives approximately two consult requests per week, usually from general internists but also from specialists in nearly all disciplines. Around 80% of the referrals are for current inpatients. Our service model is similar to a tumor board, which exists as an interdisciplinary group operating in parallel to the clinical services, to provide consensus-based recommendations. As a result, we act as doctors for doctors, formalizing the curbside consultation. Our usual turnaround time is a week but can be faster for urgent cases. Currently, Socrates Project members, including the faculty leader, volunteer their time and effort at no cost, and there are no charges to patients when physicians consult our group. An overview of the Socrates Project’s personnel and process are outlined in the Figure.

Northwestern’s Chief Medical Residents (CMRs) serve as the fellows for the service, and one of them assumes primary responsibility for each new consultation request the service receives. After obtaining the patient’s case history from the referring provider, the CMR then undertakes a thorough review of the electronic health record and any other available records from other institutions. In the inpatient setting, the CMR performs a new history and physical; phone calls or video conferencing permit history taking for outpatients. In contrast with the standard consultant note, we do not redocument the history, physical, and lab and imaging findings but instead construct a detailed problem list that synthesizes relevant findings into a useful working document.

The service’s faculty leader (BDS) then reviews the problem list with the CMRs to help refine the problem list and begin producing a differential diagnosis during a weekly hour-long meeting. As evidence supports team-based diagnostic collaborations,2 the problem list and preliminary differential diagnosis then becomes a shareable document that the CMR or team leader presents to ad hoc general internists, specialists, and the other CMRs. The presentation can be in person, by phone, or e-mail. These ad hoc members, approximately 20 in number and spanning from junior attending physicians to senior clinicians, have volunteered to help the Socrates Project by adding their thoughts on differential diagnoses that explain the problem list and how to move forward with further testing. The ad hoc members have self-identified as clinicians with an interest in medical diagnosis—including surgeons, neurologists, psychiatrists, radiologists, and pathologists—and range in expertise from general internists to subspecialists. Finally, we document our problem list, differential diagnosis, and recommendations in the medical record and discuss the case with the referring team. The service limits its scope of clinical recommendation to diagnosis and avoids commenting on management decisions outside of the use of therapies as empiric diagnostic tests. A sample note is provided as an online Appendix.

MOVING FORWARD WITH ONGOING UNCERTAINTY

Despite our process, we are often left without a satisfying diagnosis. We then are then faced with three possibilities: (1) The diagnosis is identifiable, just not by the physicians involved in the case—we did not think of the diagnosis in our deliberations; (2) The diagnosis is a described condition but without an available test—autoimmune limbic encephalitis associated with an unassayable or unknown auto-antibody, or the acuity of a critically ill patient makes diagnostic testing unreliable or not feasible; (3) The diagnosis has not yet been described by medical science—we are seeing a case of HIV infection in 1971.

With the personnel and process outlined above, we hope to provide recommendations that are useful in guiding a diagnostic workup regardless of which of these three scenarios is applicable. Our flexibility with involving the appropriate specialists in the Socrates Project should minimize the number of patients with a knowable diagnosis that is unknown to us. In the second scenario, our recommendations may rest upon the incorporation of a treatment as a diagnostic test. In the limbic encephalitis example above, a trial of steroids with rapid improvement in the patient’s condition may increase diagnostic certainty. The third scenario is the most difficult to identify. Pattern recognition of similarly presenting patients, keeping ourselves updated on pertinent primary literature, and consideration of advanced diagnostic testing such as exome sequencing and other next-generation sequencing strategies are essential in hoping to characterize a specific clinical syndrome that has yet to be described.

For situations in which our recommendations do not yield a diagnosis, we recognize the role for protocols such as genomic or metagenomic sequencing that assess multiple diagnostic possibilities in parallel without an a priori hypothesis.3,4 The utility of multi-omics testing in diagnostic workups has been detailed by the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN), which has created a systematic approach to describing new syndromes with the aid of metabolomic and genomic profiling.5 It is important to note that even with the resources available to the UDN, the diagnosis rate is 35%, emphasizing that in the majority of diagnosis-refractory cases, a diagnosis will not be found. This low diagnosis rate underscores the need for continued inquiry and cataloging of cases and data for further review or synthesis as the body of medical knowledge continues to expand. For these reasons, we have a follow-up system in place, which involves the assigned CMR regularly reviewing the chart and reporting during our weekly meetings. We make phone calls to patients and providers for cases that appear to be lost to follow-up.

LIMITATIONS

We recognize several important limitations to our care model that may represent barriers to establishing, maintaining, and evaluating a similar service at other institutions. For example, there are limitations and benefits of the CMR as point person for managing our consultations. While they are admittedly junior colleagues with limited experience, CMRs tend to be among the best-read and up-to-date clinicians in the hospital by virtue of their recent general-medicine training and identification as a top clinician and leader. Moreover, in their role with the Socrates Project, CMRs have more time to think, talk with patients, and review the medical record than other clinicians, who may be under pressure to see an increasing number of patients while billing at higher levels. Indeed, the Socrates Project CMRs have, on a number of occasions, been the team members who find the piece of data that no one else thought relevant.

Another factor that may limit establishment of a similar team at other institutions is our volunteer-based model. The Socrates Project members volunteer because they love clinical medicine and serve on the team without remuneration for professional effort. With the CMR role as a notable exception, pressure from achieving relative value unit targets, obtaining grant funding, and publishing primary research publications in their field may limit this care model, particularly when shifting from a clinical-only activity to one that also formally investigates the service’s process and outcomes.

DISCOVERY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Beyond our clinical objective, we hope that the Socrates Project will further the discovery and description of previously unrecognized disease processes. To that end, we are pursuing an institutional review board-approved protocol to perform a rigorous assessment of the Socrates Project’s process and outcomes, including a cataloging of case archetypes and the time to definitive diagnosis if a diagnosis is established. As we continue to collect data, increasing our referral network may also lead to refinement and improvement in diagnostic processes and outcomes. Over time, we expect that the diagnostic resources available to us will evolve. Utilizing collective intelligence has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy,6 and emerging artificial intelligence technologies may improve diagnostic performance as well.7,8 Most importantly, through this endeavor, we hope to serve less as an oracle and more as a humble Socratic consultant for clinicians working to reduce diagnostic uncertainty for their patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Northwestern University Chief Medical Residents, 2015-present, for their tireless efforts in support of the Socrates Project.

1. Cooper JM. Plato: Five dialogues : euthyphro, apology, crito, meno, phaedo. Hackett Publishing; 2002.

2. Hautz WE, Kammer JE, Schauber SK, Spies CD, Gaissmaier W. Diagnostic performance by medical students working individually or in teams. JAMA. 2015;313(3):303-304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.15770.

3. Adams DR, Eng CM. Next-generation sequencing to diagnose suspected genetic disorders. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(14):1353-1362. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1711801.

4. Chiu CY, Miller SA. Clinical metagenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(6):341-355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0113-7.

5. Splinter K, Adams DR, Bacino CA, et al. Effect of genetic diagnosis on patients with previously undiagnosed disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2131-2139. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1714458.

6. Barnett ML, Boddupalli D, Nundy S, Bates DW. Comparative accuracy of diagnosis by collective intelligence of multiple physicians vs individual physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

7. Liang H, Tsui BY, Ni H, et al. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):433-438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0335-9.

8. Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1347-1358. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1814259.

Internists are experts in general medicine, skilled at mapping the few hundred ways the human body can go awry onto thousands of diagnoses, and managing the uncertainty inherent in that process. Generalists, almost by definition, consult specialists with their specialty-focused questions; but who does one call for a general consultation about diagnosis if a specific diagnosis remains elusive and the pathology does not fit cleanly into the purview of a consultant? Outside of sage advice from colleagues (usually senior), most medical centers lack a consultation service focused on diagnosis. There is no oracle to seek. In this perspective, we describe our institution’s answer to this problem: the creation of a service for difficult diagnosis based on Socratic principles, particularly the role of iterative hypothesis testing in the process of diagnosis.1

In 2015, Northwestern Medicine began the Socrates Project, a physician-to-physician consultation service that assists doctors working to diagnose conditions that have so far eluded detection. Our service’s goal is to improve patient care by providing an opinion to the referring physician on diagnostic possibilities for a particular case and ideas to reduce—or at least manage—diagnostic uncertainty.

Most patients referred to the Socrates Project have already undergone an extensive evaluation at top medical centers by experienced clinicians. It would be hubris to assume that we will find a definitive diagnosis in every case; indeed, because of the types of cases referred to our group, it is rare that we find a “Eureka!” diagnosis. When a colleague consults our group, we under-promise in hopes of over-delivering. Instead, we convey to referring physicians that we will conduct a thorough case review and explain our thinking in hopes of uncovering an additional diagnostic avenue, even if that avenue does not ultimately lead to a definitive diagnosis. In addition, the Socrates Project often serves as a broker between consulting services that are deadlocked because of differing diagnostic opinions. We also assist with cases in which a functional disorder is suspected, yet the referring physician is hesitant to diagnose a patient with such a disorder out of concern about missing an important (and possibly obscure) diagnosis.

PERSONNEL AND PROCESS

The Socrates Project receives approximately two consult requests per week, usually from general internists but also from specialists in nearly all disciplines. Around 80% of the referrals are for current inpatients. Our service model is similar to a tumor board, which exists as an interdisciplinary group operating in parallel to the clinical services, to provide consensus-based recommendations. As a result, we act as doctors for doctors, formalizing the curbside consultation. Our usual turnaround time is a week but can be faster for urgent cases. Currently, Socrates Project members, including the faculty leader, volunteer their time and effort at no cost, and there are no charges to patients when physicians consult our group. An overview of the Socrates Project’s personnel and process are outlined in the Figure.

Northwestern’s Chief Medical Residents (CMRs) serve as the fellows for the service, and one of them assumes primary responsibility for each new consultation request the service receives. After obtaining the patient’s case history from the referring provider, the CMR then undertakes a thorough review of the electronic health record and any other available records from other institutions. In the inpatient setting, the CMR performs a new history and physical; phone calls or video conferencing permit history taking for outpatients. In contrast with the standard consultant note, we do not redocument the history, physical, and lab and imaging findings but instead construct a detailed problem list that synthesizes relevant findings into a useful working document.

The service’s faculty leader (BDS) then reviews the problem list with the CMRs to help refine the problem list and begin producing a differential diagnosis during a weekly hour-long meeting. As evidence supports team-based diagnostic collaborations,2 the problem list and preliminary differential diagnosis then becomes a shareable document that the CMR or team leader presents to ad hoc general internists, specialists, and the other CMRs. The presentation can be in person, by phone, or e-mail. These ad hoc members, approximately 20 in number and spanning from junior attending physicians to senior clinicians, have volunteered to help the Socrates Project by adding their thoughts on differential diagnoses that explain the problem list and how to move forward with further testing. The ad hoc members have self-identified as clinicians with an interest in medical diagnosis—including surgeons, neurologists, psychiatrists, radiologists, and pathologists—and range in expertise from general internists to subspecialists. Finally, we document our problem list, differential diagnosis, and recommendations in the medical record and discuss the case with the referring team. The service limits its scope of clinical recommendation to diagnosis and avoids commenting on management decisions outside of the use of therapies as empiric diagnostic tests. A sample note is provided as an online Appendix.

MOVING FORWARD WITH ONGOING UNCERTAINTY

Despite our process, we are often left without a satisfying diagnosis. We then are then faced with three possibilities: (1) The diagnosis is identifiable, just not by the physicians involved in the case—we did not think of the diagnosis in our deliberations; (2) The diagnosis is a described condition but without an available test—autoimmune limbic encephalitis associated with an unassayable or unknown auto-antibody, or the acuity of a critically ill patient makes diagnostic testing unreliable or not feasible; (3) The diagnosis has not yet been described by medical science—we are seeing a case of HIV infection in 1971.

With the personnel and process outlined above, we hope to provide recommendations that are useful in guiding a diagnostic workup regardless of which of these three scenarios is applicable. Our flexibility with involving the appropriate specialists in the Socrates Project should minimize the number of patients with a knowable diagnosis that is unknown to us. In the second scenario, our recommendations may rest upon the incorporation of a treatment as a diagnostic test. In the limbic encephalitis example above, a trial of steroids with rapid improvement in the patient’s condition may increase diagnostic certainty. The third scenario is the most difficult to identify. Pattern recognition of similarly presenting patients, keeping ourselves updated on pertinent primary literature, and consideration of advanced diagnostic testing such as exome sequencing and other next-generation sequencing strategies are essential in hoping to characterize a specific clinical syndrome that has yet to be described.

For situations in which our recommendations do not yield a diagnosis, we recognize the role for protocols such as genomic or metagenomic sequencing that assess multiple diagnostic possibilities in parallel without an a priori hypothesis.3,4 The utility of multi-omics testing in diagnostic workups has been detailed by the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN), which has created a systematic approach to describing new syndromes with the aid of metabolomic and genomic profiling.5 It is important to note that even with the resources available to the UDN, the diagnosis rate is 35%, emphasizing that in the majority of diagnosis-refractory cases, a diagnosis will not be found. This low diagnosis rate underscores the need for continued inquiry and cataloging of cases and data for further review or synthesis as the body of medical knowledge continues to expand. For these reasons, we have a follow-up system in place, which involves the assigned CMR regularly reviewing the chart and reporting during our weekly meetings. We make phone calls to patients and providers for cases that appear to be lost to follow-up.

LIMITATIONS

We recognize several important limitations to our care model that may represent barriers to establishing, maintaining, and evaluating a similar service at other institutions. For example, there are limitations and benefits of the CMR as point person for managing our consultations. While they are admittedly junior colleagues with limited experience, CMRs tend to be among the best-read and up-to-date clinicians in the hospital by virtue of their recent general-medicine training and identification as a top clinician and leader. Moreover, in their role with the Socrates Project, CMRs have more time to think, talk with patients, and review the medical record than other clinicians, who may be under pressure to see an increasing number of patients while billing at higher levels. Indeed, the Socrates Project CMRs have, on a number of occasions, been the team members who find the piece of data that no one else thought relevant.

Another factor that may limit establishment of a similar team at other institutions is our volunteer-based model. The Socrates Project members volunteer because they love clinical medicine and serve on the team without remuneration for professional effort. With the CMR role as a notable exception, pressure from achieving relative value unit targets, obtaining grant funding, and publishing primary research publications in their field may limit this care model, particularly when shifting from a clinical-only activity to one that also formally investigates the service’s process and outcomes.

DISCOVERY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Beyond our clinical objective, we hope that the Socrates Project will further the discovery and description of previously unrecognized disease processes. To that end, we are pursuing an institutional review board-approved protocol to perform a rigorous assessment of the Socrates Project’s process and outcomes, including a cataloging of case archetypes and the time to definitive diagnosis if a diagnosis is established. As we continue to collect data, increasing our referral network may also lead to refinement and improvement in diagnostic processes and outcomes. Over time, we expect that the diagnostic resources available to us will evolve. Utilizing collective intelligence has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy,6 and emerging artificial intelligence technologies may improve diagnostic performance as well.7,8 Most importantly, through this endeavor, we hope to serve less as an oracle and more as a humble Socratic consultant for clinicians working to reduce diagnostic uncertainty for their patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Northwestern University Chief Medical Residents, 2015-present, for their tireless efforts in support of the Socrates Project.

Internists are experts in general medicine, skilled at mapping the few hundred ways the human body can go awry onto thousands of diagnoses, and managing the uncertainty inherent in that process. Generalists, almost by definition, consult specialists with their specialty-focused questions; but who does one call for a general consultation about diagnosis if a specific diagnosis remains elusive and the pathology does not fit cleanly into the purview of a consultant? Outside of sage advice from colleagues (usually senior), most medical centers lack a consultation service focused on diagnosis. There is no oracle to seek. In this perspective, we describe our institution’s answer to this problem: the creation of a service for difficult diagnosis based on Socratic principles, particularly the role of iterative hypothesis testing in the process of diagnosis.1

In 2015, Northwestern Medicine began the Socrates Project, a physician-to-physician consultation service that assists doctors working to diagnose conditions that have so far eluded detection. Our service’s goal is to improve patient care by providing an opinion to the referring physician on diagnostic possibilities for a particular case and ideas to reduce—or at least manage—diagnostic uncertainty.

Most patients referred to the Socrates Project have already undergone an extensive evaluation at top medical centers by experienced clinicians. It would be hubris to assume that we will find a definitive diagnosis in every case; indeed, because of the types of cases referred to our group, it is rare that we find a “Eureka!” diagnosis. When a colleague consults our group, we under-promise in hopes of over-delivering. Instead, we convey to referring physicians that we will conduct a thorough case review and explain our thinking in hopes of uncovering an additional diagnostic avenue, even if that avenue does not ultimately lead to a definitive diagnosis. In addition, the Socrates Project often serves as a broker between consulting services that are deadlocked because of differing diagnostic opinions. We also assist with cases in which a functional disorder is suspected, yet the referring physician is hesitant to diagnose a patient with such a disorder out of concern about missing an important (and possibly obscure) diagnosis.

PERSONNEL AND PROCESS

The Socrates Project receives approximately two consult requests per week, usually from general internists but also from specialists in nearly all disciplines. Around 80% of the referrals are for current inpatients. Our service model is similar to a tumor board, which exists as an interdisciplinary group operating in parallel to the clinical services, to provide consensus-based recommendations. As a result, we act as doctors for doctors, formalizing the curbside consultation. Our usual turnaround time is a week but can be faster for urgent cases. Currently, Socrates Project members, including the faculty leader, volunteer their time and effort at no cost, and there are no charges to patients when physicians consult our group. An overview of the Socrates Project’s personnel and process are outlined in the Figure.

Northwestern’s Chief Medical Residents (CMRs) serve as the fellows for the service, and one of them assumes primary responsibility for each new consultation request the service receives. After obtaining the patient’s case history from the referring provider, the CMR then undertakes a thorough review of the electronic health record and any other available records from other institutions. In the inpatient setting, the CMR performs a new history and physical; phone calls or video conferencing permit history taking for outpatients. In contrast with the standard consultant note, we do not redocument the history, physical, and lab and imaging findings but instead construct a detailed problem list that synthesizes relevant findings into a useful working document.

The service’s faculty leader (BDS) then reviews the problem list with the CMRs to help refine the problem list and begin producing a differential diagnosis during a weekly hour-long meeting. As evidence supports team-based diagnostic collaborations,2 the problem list and preliminary differential diagnosis then becomes a shareable document that the CMR or team leader presents to ad hoc general internists, specialists, and the other CMRs. The presentation can be in person, by phone, or e-mail. These ad hoc members, approximately 20 in number and spanning from junior attending physicians to senior clinicians, have volunteered to help the Socrates Project by adding their thoughts on differential diagnoses that explain the problem list and how to move forward with further testing. The ad hoc members have self-identified as clinicians with an interest in medical diagnosis—including surgeons, neurologists, psychiatrists, radiologists, and pathologists—and range in expertise from general internists to subspecialists. Finally, we document our problem list, differential diagnosis, and recommendations in the medical record and discuss the case with the referring team. The service limits its scope of clinical recommendation to diagnosis and avoids commenting on management decisions outside of the use of therapies as empiric diagnostic tests. A sample note is provided as an online Appendix.

MOVING FORWARD WITH ONGOING UNCERTAINTY

Despite our process, we are often left without a satisfying diagnosis. We then are then faced with three possibilities: (1) The diagnosis is identifiable, just not by the physicians involved in the case—we did not think of the diagnosis in our deliberations; (2) The diagnosis is a described condition but without an available test—autoimmune limbic encephalitis associated with an unassayable or unknown auto-antibody, or the acuity of a critically ill patient makes diagnostic testing unreliable or not feasible; (3) The diagnosis has not yet been described by medical science—we are seeing a case of HIV infection in 1971.

With the personnel and process outlined above, we hope to provide recommendations that are useful in guiding a diagnostic workup regardless of which of these three scenarios is applicable. Our flexibility with involving the appropriate specialists in the Socrates Project should minimize the number of patients with a knowable diagnosis that is unknown to us. In the second scenario, our recommendations may rest upon the incorporation of a treatment as a diagnostic test. In the limbic encephalitis example above, a trial of steroids with rapid improvement in the patient’s condition may increase diagnostic certainty. The third scenario is the most difficult to identify. Pattern recognition of similarly presenting patients, keeping ourselves updated on pertinent primary literature, and consideration of advanced diagnostic testing such as exome sequencing and other next-generation sequencing strategies are essential in hoping to characterize a specific clinical syndrome that has yet to be described.

For situations in which our recommendations do not yield a diagnosis, we recognize the role for protocols such as genomic or metagenomic sequencing that assess multiple diagnostic possibilities in parallel without an a priori hypothesis.3,4 The utility of multi-omics testing in diagnostic workups has been detailed by the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN), which has created a systematic approach to describing new syndromes with the aid of metabolomic and genomic profiling.5 It is important to note that even with the resources available to the UDN, the diagnosis rate is 35%, emphasizing that in the majority of diagnosis-refractory cases, a diagnosis will not be found. This low diagnosis rate underscores the need for continued inquiry and cataloging of cases and data for further review or synthesis as the body of medical knowledge continues to expand. For these reasons, we have a follow-up system in place, which involves the assigned CMR regularly reviewing the chart and reporting during our weekly meetings. We make phone calls to patients and providers for cases that appear to be lost to follow-up.

LIMITATIONS

We recognize several important limitations to our care model that may represent barriers to establishing, maintaining, and evaluating a similar service at other institutions. For example, there are limitations and benefits of the CMR as point person for managing our consultations. While they are admittedly junior colleagues with limited experience, CMRs tend to be among the best-read and up-to-date clinicians in the hospital by virtue of their recent general-medicine training and identification as a top clinician and leader. Moreover, in their role with the Socrates Project, CMRs have more time to think, talk with patients, and review the medical record than other clinicians, who may be under pressure to see an increasing number of patients while billing at higher levels. Indeed, the Socrates Project CMRs have, on a number of occasions, been the team members who find the piece of data that no one else thought relevant.

Another factor that may limit establishment of a similar team at other institutions is our volunteer-based model. The Socrates Project members volunteer because they love clinical medicine and serve on the team without remuneration for professional effort. With the CMR role as a notable exception, pressure from achieving relative value unit targets, obtaining grant funding, and publishing primary research publications in their field may limit this care model, particularly when shifting from a clinical-only activity to one that also formally investigates the service’s process and outcomes.

DISCOVERY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Beyond our clinical objective, we hope that the Socrates Project will further the discovery and description of previously unrecognized disease processes. To that end, we are pursuing an institutional review board-approved protocol to perform a rigorous assessment of the Socrates Project’s process and outcomes, including a cataloging of case archetypes and the time to definitive diagnosis if a diagnosis is established. As we continue to collect data, increasing our referral network may also lead to refinement and improvement in diagnostic processes and outcomes. Over time, we expect that the diagnostic resources available to us will evolve. Utilizing collective intelligence has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy,6 and emerging artificial intelligence technologies may improve diagnostic performance as well.7,8 Most importantly, through this endeavor, we hope to serve less as an oracle and more as a humble Socratic consultant for clinicians working to reduce diagnostic uncertainty for their patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Northwestern University Chief Medical Residents, 2015-present, for their tireless efforts in support of the Socrates Project.

1. Cooper JM. Plato: Five dialogues : euthyphro, apology, crito, meno, phaedo. Hackett Publishing; 2002.

2. Hautz WE, Kammer JE, Schauber SK, Spies CD, Gaissmaier W. Diagnostic performance by medical students working individually or in teams. JAMA. 2015;313(3):303-304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.15770.

3. Adams DR, Eng CM. Next-generation sequencing to diagnose suspected genetic disorders. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(14):1353-1362. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1711801.

4. Chiu CY, Miller SA. Clinical metagenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(6):341-355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0113-7.

5. Splinter K, Adams DR, Bacino CA, et al. Effect of genetic diagnosis on patients with previously undiagnosed disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2131-2139. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1714458.

6. Barnett ML, Boddupalli D, Nundy S, Bates DW. Comparative accuracy of diagnosis by collective intelligence of multiple physicians vs individual physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

7. Liang H, Tsui BY, Ni H, et al. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):433-438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0335-9.

8. Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1347-1358. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1814259.

1. Cooper JM. Plato: Five dialogues : euthyphro, apology, crito, meno, phaedo. Hackett Publishing; 2002.

2. Hautz WE, Kammer JE, Schauber SK, Spies CD, Gaissmaier W. Diagnostic performance by medical students working individually or in teams. JAMA. 2015;313(3):303-304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.15770.

3. Adams DR, Eng CM. Next-generation sequencing to diagnose suspected genetic disorders. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(14):1353-1362. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1711801.

4. Chiu CY, Miller SA. Clinical metagenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(6):341-355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0113-7.

5. Splinter K, Adams DR, Bacino CA, et al. Effect of genetic diagnosis on patients with previously undiagnosed disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2131-2139. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1714458.

6. Barnett ML, Boddupalli D, Nundy S, Bates DW. Comparative accuracy of diagnosis by collective intelligence of multiple physicians vs individual physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

7. Liang H, Tsui BY, Ni H, et al. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):433-438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0335-9.

8. Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1347-1358. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1814259.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Call to Action: Hospitalists’ Role in Addressing Substance Use Disorder

In 2017, the death toll from drug overdoses reached a record high, killing more Americans than the entire Vietnam War or the HIV/AIDS epidemic at its peak.1 Up to one-quarter of hospitalized patients have a substance use disorder (SUD) and SUD-related2,3 hospitalizations are surging. People with SUD have longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions.3,4 While the burden of SUD is staggering, it is far from hopeless. There are multiple evidence-based and highly effective interventions to treat SUD, including medications, behavioral interventions, and harm reduction strategies.

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addictions care.5 Hospital-based addictions care has the potential to engage sicker, highly vulnerable patients, many who are not engaged in primary care or outpatient addictions care.6 Studied effects of hospital-based addictions care include improved SUD treatment engagement, reduced alcohol and drug use, lower hospital readmissions, and improved provider experience.7-9

Most hospitals, however, do not treat SUD during hospitalization and do not connect people to treatment after discharge. Hospitals may lack staffing or financial resources to implement addiction care, may believe that SUDs are an outpatient concern, may want to avoid caring for people with SUD, or may simply not know where to begin. Whatever the reason, unaddressed SUD can lead to untreated withdrawal, disruptive patient behaviors, failure to complete recommended medical therapy, high rates of against medical advice discharge, poor patient experience, and widespread provider distress.8

Hospitalists—individually and collectively—are uniquely positioned to address this gap. By treating addiction effectively and compassionately, hospitalists can engage patients, improve care, improve patient and provider experience, and lower costs. This paper is a call to action that describes the current state of hospital-based addictions care, outlines key challenges to implementing SUD care in the hospital, debunks common misconceptions, and identifies actionable steps for hospitalists, hospital leaders, and hospitalist organizations.

MODELS TO DELIVER HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging; they include a range of models, with variations in how patients are identified, team composition, service availability, and financing.10 Existing addiction medicine consult services commonly offer SUD assessments, psychological intervention, medical management of SUDs (eg, initiating methadone or buprenorphine), medical pain management, and linkage to SUD care after hospitalization. Some services also explicitly integrate harm reduction principles (eg, naloxone distribution, safe injection education, permitting patients to smoke).11 Additional consult service activities include hospital-wide SUD education, and creation and implementation of hospital guidance documents (eg, methadone policies).10 Some consult services utilize only physicians, while others include interprofessional providers, such as nurses, social workers, and peers with lived experience of addiction. Whereas addiction medicine physicians staff some consult services, hospitalists with less formal addiction credentials staff others.

Broadly, hospital-based addictions care cannot depend solely on consult services. Just as not all hospitals have cardiology consult services, not all hospitals will have addiction consult services. As such, hospitalists can play an even greater role by implementing order sets and guidelines, supporting partnerships with community SUD treatment, and independently initiating evidence-based medications.

CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Pervasive individual and structural stigmas12 are perhaps the most critical barriers to incorporating addiction medicine into routine hospital practice, and they are both cause and consequence of our system failures. Most medical schools and residencies lack SUD training, which means that the understanding of addiction as a moral deficiency or lack of willpower may remain unchallenged. Stigma surrounding SUDs contributes to hospitalists’ and hospital leaders’ aversion to treating patients with SUD, and to fears that providing quality SUD care will attract patients suffering from these conditions.

Recent national efforts have focused on the problem of opioid overprescribing. Without an equal emphasis on treatment, this focus can lead to undertreatment of pain and/or opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients, particularly since most hospitalists have little to no training in diagnosing SUD, prescribing life-saving medications for opioid use disorder, or managing acute pain in patients with SUD. The focus on overprescribing also diverts attention away from trends involving stimulants,2 fentanyl contamination of the drug supply,13 and alcohol, all of which have important implications for the care of hospitalized adults.

Hospital policies are often not grounded in evidence (eg, recommending clonidine for first-line treatment of opioid withdrawal and not buprenorphine/methadone), and there are widespread misconceptions about perceived legal barriers to treating opioid use disorder in the hospital, which is both safe and legal.10 People with SUD may be unjustly viewed through a criminal justice lens. Policies focused on controlling visitors and conducting room searches disproportionately burden people with SUD, which may create further harms through reinforcing negative provider cognitive biases about SUDs. Finally, hospitals may lack inpatient social work and pharmacy supports, and they rarely have pathways to connect people to SUD care after discharge.

Funding remains a widespread challenge. While some hospital administrators support addiction medicine services because of the pressing medical need and public health crisis, most services depend on billing or demonstrated savings through reduced hospital days or readmissions.

A CALL TO ACTION: HOW HOSPITALISTS CAN IMPROVE ADDICTION CARE

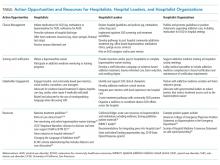

Individual hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, and hospitalist organizations can engage by improving individual practice, driving systems change, and through advocacy and policy change (Table).

Individual Hospitalists

Providing basic addiction medicine care should be a core competency for all hospitalists, just as every hospitalist can initiate a goals-of-care conversation or prescribe insulin. For opioid use disorder, hospitalists should treat withdrawal and offer treatment initiation with opioid agonist therapy (ie, methadone, buprenorphine), which reduces mortality by over half. Commonly, hospitalized patients are subjected to harmful, nonevidence-based treatments, such as mandated rapid methadone tapers,25 which can lead to undertreated withdrawal, increased pain, and opioid cravings. This increases patients’ risk for overdose after discharge and precludes them from receiving life-saving, evidence-based methadone maintenance, or buprenorphine treatment. Though widely misunderstood, prescribing methadone in the hospital is legal, and providers need no special waiver to prescribe buprenorphine during admission. Current laws require that hospitalists have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge and prohibit hospitalists (or anyone outside of an opioid treatment program) from prescribing methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder at discharge. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol use disorder (eg, naltrexone) and be good stewards of opioids during hospitalization, avoiding intravenous opioids where appropriate and curbing excessive prescribing at discharge. Given high rates of overdose and fentanyl contamination of stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone at discharge to every patient with SUD, on chronic opioids, or who uses any nonmedical substances.

Resources exist for individual hospitalists seeking mentorship or additional training (Table). Though not necessary for in-hospital prescribing, hospitalists can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge (commonly called the X-waiver). To qualify, physicians must complete eight hours of accredited training (online and/or in-person), after which they must request a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Advanced-practice practitioners must complete 24 hours of training. Many have argued that policymakers should end this waiver requirement.26 While we support efforts to “X the X” and urgently expand treatment access, additional training can enrich providers’ knowledge and confidence to prescribe buprenorphine, and is a relatively simple way that all hospitalists could act. Finally, by treating addiction and modeling patient-centered addictions care, hospitalists can legitimize and destigmatize the disease of addiction,8 and have the potential to mentor and train students, residents, nurses, and other staff.27

Hospitalist Leaders

As leaders, hospitalists can play a key role in promoting hospital-based addictions care and tailoring solutions to meet local needs. Leaders can promote a cultural shift away from stigma, and promote evidence-based, life-saving care. Hospitalist leaders could require all hospitalists to obtain buprenorphine waivers. Leaders could initiate quality improvement projects related to SUD service delivery, develop policies that support inpatient SUD treatment, develop order sets for medication initiation, engage community substance use treatment partners, build pathways to timely addiction care after discharge, and champion development of addiction medicine consult services.

Hospitalist leaders can reference open-source guidelines, order sets, assessment and treatment tools, patient materials, pharmacy and therapeutics committee materials, and other resources for implementing services for hospitalized patients with SUD (Table).21,22 Hospitalist leaders who understand financial and quality drivers can also champion the business and quality case for hospital-based addictions care, and help pursue local and national funding opportunities.

Hospitalist Organizations

Hospitalist societies could provide training at regional and national conferences to upskill hospitalists to care for people with SUD; support addiction medicine interest groups; and partner with addiction medicine societies, harm reduction organizations, and organizations focused on trauma-informed care. They could endorse practice guidelines and position statements describing the crucial role of hospitalists in addressing the overdose crisis and offering medication for addiction (Table). Hospitalist organizations can engage national and state hospital associations, lobby medical specialties to include addiction medicine competencies in board certification requirements, and advocate with governmental leaders to reduce barriers that restrict treatment access such as the X-waiver.

MOVING FORWARD

Regardless of whether a hospitalist is serving as an individual provider, a hospitalist leader, or as part of a hospitalist organization, hospitalists can take critical steps to advance the care of people with SUD. These steps shift the culture of hospitals from one where patients are afraid to discuss their substance use, to one that creates space for connection, treatment engagement, and healing. By starting medications, utilizing widely accessible resources, and collaborating with community treatment and harm reduction organizations, each one of us can play a part in addressing the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript. Dr. Englander would like to thank Dr. David Bangsberg and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for their mentorship.

1. Weiss A, Elixhauser A, Barrett M, Steiner C, Bailey M, O’Malley L. Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009-2014. Statistical Brief #219. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2016. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp. Accessed May 21, 2019.

2. Winkelman TA, Admon LK, Jennings L, Shippee ND, Richardson CR, Bart G. Evaluation of amphetamine-related hospitalizations and associated clinical outcomes and costs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183758. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3758.

3. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424.

4. Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, et al. Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. J Addict Med. 2012;6(1):50-56. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e318231de51.

5. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736.

6. Velez C, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis P, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. doi 10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4.

7. Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):909-916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z.

8. Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. “We’ve learned it’s a medical illness, not a moral choice”: qualitative study of the effects of a multicomponent addiction intervention on hospital providers’ attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752-758. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2993.

9. McQueen J, Howe TE, Allan L, Mains D, Hardy V. Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(8):CD005191 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005191.pub3.

10. Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496.

11. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001.

12. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a “risk environment”: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010.

13. Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Policy. 2019. pii: S0955-3959(19)30018-0. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.010.

14. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder-Executive Summary. February 2018. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-63-Medications-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Executive-Summary/sma18-5063exsumm. Accessed August 8, 2019.

15. Providers Clinical Support System. Discover the rewards of treating patients with Opioid Use Disorders. https://pcssnow.org/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

16. California Bridge Program. Treatment Starts Here: Resources for the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders from the Acute Care Setting. https://www.bridgetotreatment.org/resources. Accessed August 7, 2019.

17. Clinical Consultation Center. Substance Use Resources. 2019. https://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinical-resources/substance-use-resources/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

18. Thakarar K, Weinstein ZM, Walley AY. Optimising health and safety of people who inject drugs during transition from acute to outpatient care: narrative review with clinical checklist. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1088):356-363. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133720.

19. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Changing the Language of Addiction. Washington, D.C. 2017. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Memo%20-%20Changing%20Federal%20Terminology%20Regrading%20Substance%20Use%20and%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2019.

20. The University of New Mexico. Project ECHO: A Revolution in Medical Education and Care Delivery. 2019. https://echo.unm.edu/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

21. Englander H, Mahoney S, Brandt K, et al. Tools to support hospital-based addiction care: core components, values, and activities of the Improving Addiction Care Team. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):85-89. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000487.

22. Englander H, Gregg J, Gollickson J, et al. Recommendations for intergrating peer mentors in hospital-based addiction care. Subst Abus. In press. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1635968.

23. American College of Medical Toxicology. ACMT Position Statement: Buprenorphine Administration in the Emergency Department. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/equal-documents/policy_acmt_bupeadministration.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2019.

24. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

25. Winetsky D, Weinrieb RM, Perrone J. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):62-64. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2861.

26. Frank JW, Wakeman SE, Gordon AJ. No end to the crisis without an end to the waiver. Subst Abus. 2018;39(3):263-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2018.1543382.

27. Gorfinkel L, Klimas J, Reel B, et al. In-hospital training in addiction medicine: a mixed-methods study of health care provider benefits and differences. Subst Abus. 2019. In press. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2018.1561596.

In 2017, the death toll from drug overdoses reached a record high, killing more Americans than the entire Vietnam War or the HIV/AIDS epidemic at its peak.1 Up to one-quarter of hospitalized patients have a substance use disorder (SUD) and SUD-related2,3 hospitalizations are surging. People with SUD have longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions.3,4 While the burden of SUD is staggering, it is far from hopeless. There are multiple evidence-based and highly effective interventions to treat SUD, including medications, behavioral interventions, and harm reduction strategies.

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addictions care.5 Hospital-based addictions care has the potential to engage sicker, highly vulnerable patients, many who are not engaged in primary care or outpatient addictions care.6 Studied effects of hospital-based addictions care include improved SUD treatment engagement, reduced alcohol and drug use, lower hospital readmissions, and improved provider experience.7-9

Most hospitals, however, do not treat SUD during hospitalization and do not connect people to treatment after discharge. Hospitals may lack staffing or financial resources to implement addiction care, may believe that SUDs are an outpatient concern, may want to avoid caring for people with SUD, or may simply not know where to begin. Whatever the reason, unaddressed SUD can lead to untreated withdrawal, disruptive patient behaviors, failure to complete recommended medical therapy, high rates of against medical advice discharge, poor patient experience, and widespread provider distress.8

Hospitalists—individually and collectively—are uniquely positioned to address this gap. By treating addiction effectively and compassionately, hospitalists can engage patients, improve care, improve patient and provider experience, and lower costs. This paper is a call to action that describes the current state of hospital-based addictions care, outlines key challenges to implementing SUD care in the hospital, debunks common misconceptions, and identifies actionable steps for hospitalists, hospital leaders, and hospitalist organizations.

MODELS TO DELIVER HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging; they include a range of models, with variations in how patients are identified, team composition, service availability, and financing.10 Existing addiction medicine consult services commonly offer SUD assessments, psychological intervention, medical management of SUDs (eg, initiating methadone or buprenorphine), medical pain management, and linkage to SUD care after hospitalization. Some services also explicitly integrate harm reduction principles (eg, naloxone distribution, safe injection education, permitting patients to smoke).11 Additional consult service activities include hospital-wide SUD education, and creation and implementation of hospital guidance documents (eg, methadone policies).10 Some consult services utilize only physicians, while others include interprofessional providers, such as nurses, social workers, and peers with lived experience of addiction. Whereas addiction medicine physicians staff some consult services, hospitalists with less formal addiction credentials staff others.

Broadly, hospital-based addictions care cannot depend solely on consult services. Just as not all hospitals have cardiology consult services, not all hospitals will have addiction consult services. As such, hospitalists can play an even greater role by implementing order sets and guidelines, supporting partnerships with community SUD treatment, and independently initiating evidence-based medications.

CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Pervasive individual and structural stigmas12 are perhaps the most critical barriers to incorporating addiction medicine into routine hospital practice, and they are both cause and consequence of our system failures. Most medical schools and residencies lack SUD training, which means that the understanding of addiction as a moral deficiency or lack of willpower may remain unchallenged. Stigma surrounding SUDs contributes to hospitalists’ and hospital leaders’ aversion to treating patients with SUD, and to fears that providing quality SUD care will attract patients suffering from these conditions.

Recent national efforts have focused on the problem of opioid overprescribing. Without an equal emphasis on treatment, this focus can lead to undertreatment of pain and/or opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients, particularly since most hospitalists have little to no training in diagnosing SUD, prescribing life-saving medications for opioid use disorder, or managing acute pain in patients with SUD. The focus on overprescribing also diverts attention away from trends involving stimulants,2 fentanyl contamination of the drug supply,13 and alcohol, all of which have important implications for the care of hospitalized adults.

Hospital policies are often not grounded in evidence (eg, recommending clonidine for first-line treatment of opioid withdrawal and not buprenorphine/methadone), and there are widespread misconceptions about perceived legal barriers to treating opioid use disorder in the hospital, which is both safe and legal.10 People with SUD may be unjustly viewed through a criminal justice lens. Policies focused on controlling visitors and conducting room searches disproportionately burden people with SUD, which may create further harms through reinforcing negative provider cognitive biases about SUDs. Finally, hospitals may lack inpatient social work and pharmacy supports, and they rarely have pathways to connect people to SUD care after discharge.

Funding remains a widespread challenge. While some hospital administrators support addiction medicine services because of the pressing medical need and public health crisis, most services depend on billing or demonstrated savings through reduced hospital days or readmissions.

A CALL TO ACTION: HOW HOSPITALISTS CAN IMPROVE ADDICTION CARE

Individual hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, and hospitalist organizations can engage by improving individual practice, driving systems change, and through advocacy and policy change (Table).

Individual Hospitalists

Providing basic addiction medicine care should be a core competency for all hospitalists, just as every hospitalist can initiate a goals-of-care conversation or prescribe insulin. For opioid use disorder, hospitalists should treat withdrawal and offer treatment initiation with opioid agonist therapy (ie, methadone, buprenorphine), which reduces mortality by over half. Commonly, hospitalized patients are subjected to harmful, nonevidence-based treatments, such as mandated rapid methadone tapers,25 which can lead to undertreated withdrawal, increased pain, and opioid cravings. This increases patients’ risk for overdose after discharge and precludes them from receiving life-saving, evidence-based methadone maintenance, or buprenorphine treatment. Though widely misunderstood, prescribing methadone in the hospital is legal, and providers need no special waiver to prescribe buprenorphine during admission. Current laws require that hospitalists have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge and prohibit hospitalists (or anyone outside of an opioid treatment program) from prescribing methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder at discharge. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol use disorder (eg, naltrexone) and be good stewards of opioids during hospitalization, avoiding intravenous opioids where appropriate and curbing excessive prescribing at discharge. Given high rates of overdose and fentanyl contamination of stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone at discharge to every patient with SUD, on chronic opioids, or who uses any nonmedical substances.

Resources exist for individual hospitalists seeking mentorship or additional training (Table). Though not necessary for in-hospital prescribing, hospitalists can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge (commonly called the X-waiver). To qualify, physicians must complete eight hours of accredited training (online and/or in-person), after which they must request a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Advanced-practice practitioners must complete 24 hours of training. Many have argued that policymakers should end this waiver requirement.26 While we support efforts to “X the X” and urgently expand treatment access, additional training can enrich providers’ knowledge and confidence to prescribe buprenorphine, and is a relatively simple way that all hospitalists could act. Finally, by treating addiction and modeling patient-centered addictions care, hospitalists can legitimize and destigmatize the disease of addiction,8 and have the potential to mentor and train students, residents, nurses, and other staff.27

Hospitalist Leaders

As leaders, hospitalists can play a key role in promoting hospital-based addictions care and tailoring solutions to meet local needs. Leaders can promote a cultural shift away from stigma, and promote evidence-based, life-saving care. Hospitalist leaders could require all hospitalists to obtain buprenorphine waivers. Leaders could initiate quality improvement projects related to SUD service delivery, develop policies that support inpatient SUD treatment, develop order sets for medication initiation, engage community substance use treatment partners, build pathways to timely addiction care after discharge, and champion development of addiction medicine consult services.

Hospitalist leaders can reference open-source guidelines, order sets, assessment and treatment tools, patient materials, pharmacy and therapeutics committee materials, and other resources for implementing services for hospitalized patients with SUD (Table).21,22 Hospitalist leaders who understand financial and quality drivers can also champion the business and quality case for hospital-based addictions care, and help pursue local and national funding opportunities.

Hospitalist Organizations

Hospitalist societies could provide training at regional and national conferences to upskill hospitalists to care for people with SUD; support addiction medicine interest groups; and partner with addiction medicine societies, harm reduction organizations, and organizations focused on trauma-informed care. They could endorse practice guidelines and position statements describing the crucial role of hospitalists in addressing the overdose crisis and offering medication for addiction (Table). Hospitalist organizations can engage national and state hospital associations, lobby medical specialties to include addiction medicine competencies in board certification requirements, and advocate with governmental leaders to reduce barriers that restrict treatment access such as the X-waiver.

MOVING FORWARD

Regardless of whether a hospitalist is serving as an individual provider, a hospitalist leader, or as part of a hospitalist organization, hospitalists can take critical steps to advance the care of people with SUD. These steps shift the culture of hospitals from one where patients are afraid to discuss their substance use, to one that creates space for connection, treatment engagement, and healing. By starting medications, utilizing widely accessible resources, and collaborating with community treatment and harm reduction organizations, each one of us can play a part in addressing the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript. Dr. Englander would like to thank Dr. David Bangsberg and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for their mentorship.

In 2017, the death toll from drug overdoses reached a record high, killing more Americans than the entire Vietnam War or the HIV/AIDS epidemic at its peak.1 Up to one-quarter of hospitalized patients have a substance use disorder (SUD) and SUD-related2,3 hospitalizations are surging. People with SUD have longer hospital stays, higher costs, and more readmissions.3,4 While the burden of SUD is staggering, it is far from hopeless. There are multiple evidence-based and highly effective interventions to treat SUD, including medications, behavioral interventions, and harm reduction strategies.

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addictions care.5 Hospital-based addictions care has the potential to engage sicker, highly vulnerable patients, many who are not engaged in primary care or outpatient addictions care.6 Studied effects of hospital-based addictions care include improved SUD treatment engagement, reduced alcohol and drug use, lower hospital readmissions, and improved provider experience.7-9

Most hospitals, however, do not treat SUD during hospitalization and do not connect people to treatment after discharge. Hospitals may lack staffing or financial resources to implement addiction care, may believe that SUDs are an outpatient concern, may want to avoid caring for people with SUD, or may simply not know where to begin. Whatever the reason, unaddressed SUD can lead to untreated withdrawal, disruptive patient behaviors, failure to complete recommended medical therapy, high rates of against medical advice discharge, poor patient experience, and widespread provider distress.8

Hospitalists—individually and collectively—are uniquely positioned to address this gap. By treating addiction effectively and compassionately, hospitalists can engage patients, improve care, improve patient and provider experience, and lower costs. This paper is a call to action that describes the current state of hospital-based addictions care, outlines key challenges to implementing SUD care in the hospital, debunks common misconceptions, and identifies actionable steps for hospitalists, hospital leaders, and hospitalist organizations.

MODELS TO DELIVER HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging; they include a range of models, with variations in how patients are identified, team composition, service availability, and financing.10 Existing addiction medicine consult services commonly offer SUD assessments, psychological intervention, medical management of SUDs (eg, initiating methadone or buprenorphine), medical pain management, and linkage to SUD care after hospitalization. Some services also explicitly integrate harm reduction principles (eg, naloxone distribution, safe injection education, permitting patients to smoke).11 Additional consult service activities include hospital-wide SUD education, and creation and implementation of hospital guidance documents (eg, methadone policies).10 Some consult services utilize only physicians, while others include interprofessional providers, such as nurses, social workers, and peers with lived experience of addiction. Whereas addiction medicine physicians staff some consult services, hospitalists with less formal addiction credentials staff others.

Broadly, hospital-based addictions care cannot depend solely on consult services. Just as not all hospitals have cardiology consult services, not all hospitals will have addiction consult services. As such, hospitalists can play an even greater role by implementing order sets and guidelines, supporting partnerships with community SUD treatment, and independently initiating evidence-based medications.

CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF HOSPITAL-BASED ADDICTIONS CARE

Pervasive individual and structural stigmas12 are perhaps the most critical barriers to incorporating addiction medicine into routine hospital practice, and they are both cause and consequence of our system failures. Most medical schools and residencies lack SUD training, which means that the understanding of addiction as a moral deficiency or lack of willpower may remain unchallenged. Stigma surrounding SUDs contributes to hospitalists’ and hospital leaders’ aversion to treating patients with SUD, and to fears that providing quality SUD care will attract patients suffering from these conditions.

Recent national efforts have focused on the problem of opioid overprescribing. Without an equal emphasis on treatment, this focus can lead to undertreatment of pain and/or opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients, particularly since most hospitalists have little to no training in diagnosing SUD, prescribing life-saving medications for opioid use disorder, or managing acute pain in patients with SUD. The focus on overprescribing also diverts attention away from trends involving stimulants,2 fentanyl contamination of the drug supply,13 and alcohol, all of which have important implications for the care of hospitalized adults.

Hospital policies are often not grounded in evidence (eg, recommending clonidine for first-line treatment of opioid withdrawal and not buprenorphine/methadone), and there are widespread misconceptions about perceived legal barriers to treating opioid use disorder in the hospital, which is both safe and legal.10 People with SUD may be unjustly viewed through a criminal justice lens. Policies focused on controlling visitors and conducting room searches disproportionately burden people with SUD, which may create further harms through reinforcing negative provider cognitive biases about SUDs. Finally, hospitals may lack inpatient social work and pharmacy supports, and they rarely have pathways to connect people to SUD care after discharge.

Funding remains a widespread challenge. While some hospital administrators support addiction medicine services because of the pressing medical need and public health crisis, most services depend on billing or demonstrated savings through reduced hospital days or readmissions.

A CALL TO ACTION: HOW HOSPITALISTS CAN IMPROVE ADDICTION CARE

Individual hospitalists, hospitalist leaders, and hospitalist organizations can engage by improving individual practice, driving systems change, and through advocacy and policy change (Table).

Individual Hospitalists

Providing basic addiction medicine care should be a core competency for all hospitalists, just as every hospitalist can initiate a goals-of-care conversation or prescribe insulin. For opioid use disorder, hospitalists should treat withdrawal and offer treatment initiation with opioid agonist therapy (ie, methadone, buprenorphine), which reduces mortality by over half. Commonly, hospitalized patients are subjected to harmful, nonevidence-based treatments, such as mandated rapid methadone tapers,25 which can lead to undertreated withdrawal, increased pain, and opioid cravings. This increases patients’ risk for overdose after discharge and precludes them from receiving life-saving, evidence-based methadone maintenance, or buprenorphine treatment. Though widely misunderstood, prescribing methadone in the hospital is legal, and providers need no special waiver to prescribe buprenorphine during admission. Current laws require that hospitalists have a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge and prohibit hospitalists (or anyone outside of an opioid treatment program) from prescribing methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder at discharge. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol use disorder (eg, naltrexone) and be good stewards of opioids during hospitalization, avoiding intravenous opioids where appropriate and curbing excessive prescribing at discharge. Given high rates of overdose and fentanyl contamination of stimulants, opioids, and benzodiazepines, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone at discharge to every patient with SUD, on chronic opioids, or who uses any nonmedical substances.

Resources exist for individual hospitalists seeking mentorship or additional training (Table). Though not necessary for in-hospital prescribing, hospitalists can obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge (commonly called the X-waiver). To qualify, physicians must complete eight hours of accredited training (online and/or in-person), after which they must request a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Advanced-practice practitioners must complete 24 hours of training. Many have argued that policymakers should end this waiver requirement.26 While we support efforts to “X the X” and urgently expand treatment access, additional training can enrich providers’ knowledge and confidence to prescribe buprenorphine, and is a relatively simple way that all hospitalists could act. Finally, by treating addiction and modeling patient-centered addictions care, hospitalists can legitimize and destigmatize the disease of addiction,8 and have the potential to mentor and train students, residents, nurses, and other staff.27

Hospitalist Leaders

As leaders, hospitalists can play a key role in promoting hospital-based addictions care and tailoring solutions to meet local needs. Leaders can promote a cultural shift away from stigma, and promote evidence-based, life-saving care. Hospitalist leaders could require all hospitalists to obtain buprenorphine waivers. Leaders could initiate quality improvement projects related to SUD service delivery, develop policies that support inpatient SUD treatment, develop order sets for medication initiation, engage community substance use treatment partners, build pathways to timely addiction care after discharge, and champion development of addiction medicine consult services.

Hospitalist leaders can reference open-source guidelines, order sets, assessment and treatment tools, patient materials, pharmacy and therapeutics committee materials, and other resources for implementing services for hospitalized patients with SUD (Table).21,22 Hospitalist leaders who understand financial and quality drivers can also champion the business and quality case for hospital-based addictions care, and help pursue local and national funding opportunities.

Hospitalist Organizations

Hospitalist societies could provide training at regional and national conferences to upskill hospitalists to care for people with SUD; support addiction medicine interest groups; and partner with addiction medicine societies, harm reduction organizations, and organizations focused on trauma-informed care. They could endorse practice guidelines and position statements describing the crucial role of hospitalists in addressing the overdose crisis and offering medication for addiction (Table). Hospitalist organizations can engage national and state hospital associations, lobby medical specialties to include addiction medicine competencies in board certification requirements, and advocate with governmental leaders to reduce barriers that restrict treatment access such as the X-waiver.

MOVING FORWARD

Regardless of whether a hospitalist is serving as an individual provider, a hospitalist leader, or as part of a hospitalist organization, hospitalists can take critical steps to advance the care of people with SUD. These steps shift the culture of hospitals from one where patients are afraid to discuss their substance use, to one that creates space for connection, treatment engagement, and healing. By starting medications, utilizing widely accessible resources, and collaborating with community treatment and harm reduction organizations, each one of us can play a part in addressing the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript. Dr. Englander would like to thank Dr. David Bangsberg and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for their mentorship.