User login

Traditional Chinese medicine improves outcomes in HFrEF

When added to guideline-directed therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), a traditional Chinese medicine called qiliqiangxin reduced the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization by more than 20%, results of a large placebo-controlled trial show.

reported Xinli Li, MD, PhD, First Affiliated Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, China.

Qiliqiangxin, a commonly used therapy in China for cardiovascular disease, is not a single chemical entity but a treatment composed of 11 plant-based substances that together are associated with diuretic effects, vasodilation, and “cardiotonic” activity, Dr. Li said. He also cited studies showing an upregulation effect on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-beta (PGC1-beta).

The results were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Hard endpoints pursued in rigorous design

There have been numerous studies of qiliqiangxin for cardiovascular diseases, including a double-blind study that associated this agent with a greater than 30% reduction in the surrogate endpoint of N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).

In the newly completed multicenter trial, called QUEST, the goal was to determine whether this therapy could reduce hard endpoints relative to placebo in a rigorously conducted trial enrolling patients receiving an optimized triple-therapy heart failure regimen.

Few patients in the study received a sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2 inhibitor), which was not a standard at the time the study was designed but is now part of the quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy in most European and North American guidelines.

In this trial, 3,119 patients were randomly assigned at 133 centers in China to take four capsules of qiliqiangxin or placebo three times per day. At a median follow-up of 18.3 months, outcomes were evaluable in nearly all 1,561 patients randomly assigned to the experimental therapy and 1,555 patients randomly assigned to placebo.

The key inclusion criteria were a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less and a serum NT-proBNP level of at least 450 pg/mL. Patients in New York Heart Association class IV heart failure were excluded.

At enrollment, more than 80% of patients in both arms were receiving a renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitor (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, or angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor), more than 80% were receiving a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, and more than 85% were receiving a beta-blocker.

Death and hospitalization reduced 22%

By hazard ratio, the primary composite endpoint of CV death and heart failure hospitalization was reduced by 22% relative to placebo (HR, 0.78; P < .001). When evaluated separately, the relative reductions in these respective endpoints were 17% (HR, 0.83; P = .045) and 24% (HR, 0.76; P = .002).

The risk reduction was robust (HR, 0.76; P < .001) in patients with an ischemic cause but nonsignificant in those without (HR, 0.92; P = .575). A significant benefit was sustained in patients receiving an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (HR, 0.84; P = .041), as well as those who did not receive this class of drug (HR, 0.77; P = .012).

However, the benefit of qiliqiangxin among patients receiving all components of guideline-directed triple therapy (RAS inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid antagonist) was only a trend (HR, 0.86; P = .079).

All-cause mortality, a secondary endpoint, was lower among patients randomly assigned to qiliqiangxin than to those assigned to placebo, but this difference fell just short of statistical significance (14.21% vs. 16.85%; P = .058).

Qiliqiangxin was well tolerated. The proportion of patients with a serious adverse event was numerically lower with qiliqiangxin than with placebo (17.43% vs. 19.74%), whereas discontinuations associated with an adverse event were numerically higher in the qiliqiangxin group (1.03% vs. 0.58%), albeit still very low in both study arms.

Overlap of drug benefits suspected

Given the safety of this drug and its highly significant reduction in a composite endpoint used in other major HFrEF trials, the ESC-invited discussant, Carolyn S.P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, National Heart Centre, Singapore, called the outcome “remarkable” and a validation for “the millions of people” who are already taking qiliqiangxin in China and other Asian countries.

Using the DAPA-HF trial as a point of reference, Dr. Lam noted that relative reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death for the SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin relative to placebo on top of triple guideline-directed medical therapy was lower (17% vs. 24%), but there were significant reductions in each of the components, as well as a nonsignificant signal of a mortality benefit.

However, Dr. Lam pointed out that there does seem to be more of an overlap for the benefits of qiliqiangxin than dapagliflozin relative to other components of triple therapy based on the lower rate of benefit when patients were optimized on triple therapy.

“The subgroup analysis [of this study] is very important,” Dr. Lam said. Qiliqiangxin may be best in patients who cannot take one or more of the components of triple therapy, she suggested, even though she called for further studies to test this theory. She also cautioned that the pill burden of four capsules taken three times per day might be onerous for some patients.

Of the many questions still to be answered, Dr. Lam noted that the low rate of enrollment for patients (< 10%) taking SGLT-2 inhibitors makes the contribution of qiliqiangxin unclear among those receiving the current standard of quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy.

She also suggested that it will be important to dissect the relative contribution of the different active ingredients of qiliqiangxin.

“This is not a purified compound that we are used to in Western medicine,” Dr. Lam said. While she praised the study as “scientifically rigorous” and indicated that the results support a clinical benefit from qiliqiangxin, she thinks an exploration of the mechanism or mechanisms of benefit is a next step in understanding where this therapy fits in HFrEF management.

Dr. Li reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Roche, and Yiling. Dr. Lam reports financial relationships with more than 25 pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, many of which produce therapies for heart failure, as well as with Medscape/WebMD Global LLC. The study was supported by the Chinese National Key Research and Development Project and Yiling Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When added to guideline-directed therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), a traditional Chinese medicine called qiliqiangxin reduced the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization by more than 20%, results of a large placebo-controlled trial show.

reported Xinli Li, MD, PhD, First Affiliated Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, China.

Qiliqiangxin, a commonly used therapy in China for cardiovascular disease, is not a single chemical entity but a treatment composed of 11 plant-based substances that together are associated with diuretic effects, vasodilation, and “cardiotonic” activity, Dr. Li said. He also cited studies showing an upregulation effect on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-beta (PGC1-beta).

The results were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Hard endpoints pursued in rigorous design

There have been numerous studies of qiliqiangxin for cardiovascular diseases, including a double-blind study that associated this agent with a greater than 30% reduction in the surrogate endpoint of N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).

In the newly completed multicenter trial, called QUEST, the goal was to determine whether this therapy could reduce hard endpoints relative to placebo in a rigorously conducted trial enrolling patients receiving an optimized triple-therapy heart failure regimen.

Few patients in the study received a sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2 inhibitor), which was not a standard at the time the study was designed but is now part of the quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy in most European and North American guidelines.

In this trial, 3,119 patients were randomly assigned at 133 centers in China to take four capsules of qiliqiangxin or placebo three times per day. At a median follow-up of 18.3 months, outcomes were evaluable in nearly all 1,561 patients randomly assigned to the experimental therapy and 1,555 patients randomly assigned to placebo.

The key inclusion criteria were a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less and a serum NT-proBNP level of at least 450 pg/mL. Patients in New York Heart Association class IV heart failure were excluded.

At enrollment, more than 80% of patients in both arms were receiving a renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitor (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, or angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor), more than 80% were receiving a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, and more than 85% were receiving a beta-blocker.

Death and hospitalization reduced 22%

By hazard ratio, the primary composite endpoint of CV death and heart failure hospitalization was reduced by 22% relative to placebo (HR, 0.78; P < .001). When evaluated separately, the relative reductions in these respective endpoints were 17% (HR, 0.83; P = .045) and 24% (HR, 0.76; P = .002).

The risk reduction was robust (HR, 0.76; P < .001) in patients with an ischemic cause but nonsignificant in those without (HR, 0.92; P = .575). A significant benefit was sustained in patients receiving an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (HR, 0.84; P = .041), as well as those who did not receive this class of drug (HR, 0.77; P = .012).

However, the benefit of qiliqiangxin among patients receiving all components of guideline-directed triple therapy (RAS inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid antagonist) was only a trend (HR, 0.86; P = .079).

All-cause mortality, a secondary endpoint, was lower among patients randomly assigned to qiliqiangxin than to those assigned to placebo, but this difference fell just short of statistical significance (14.21% vs. 16.85%; P = .058).

Qiliqiangxin was well tolerated. The proportion of patients with a serious adverse event was numerically lower with qiliqiangxin than with placebo (17.43% vs. 19.74%), whereas discontinuations associated with an adverse event were numerically higher in the qiliqiangxin group (1.03% vs. 0.58%), albeit still very low in both study arms.

Overlap of drug benefits suspected

Given the safety of this drug and its highly significant reduction in a composite endpoint used in other major HFrEF trials, the ESC-invited discussant, Carolyn S.P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, National Heart Centre, Singapore, called the outcome “remarkable” and a validation for “the millions of people” who are already taking qiliqiangxin in China and other Asian countries.

Using the DAPA-HF trial as a point of reference, Dr. Lam noted that relative reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death for the SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin relative to placebo on top of triple guideline-directed medical therapy was lower (17% vs. 24%), but there were significant reductions in each of the components, as well as a nonsignificant signal of a mortality benefit.

However, Dr. Lam pointed out that there does seem to be more of an overlap for the benefits of qiliqiangxin than dapagliflozin relative to other components of triple therapy based on the lower rate of benefit when patients were optimized on triple therapy.

“The subgroup analysis [of this study] is very important,” Dr. Lam said. Qiliqiangxin may be best in patients who cannot take one or more of the components of triple therapy, she suggested, even though she called for further studies to test this theory. She also cautioned that the pill burden of four capsules taken three times per day might be onerous for some patients.

Of the many questions still to be answered, Dr. Lam noted that the low rate of enrollment for patients (< 10%) taking SGLT-2 inhibitors makes the contribution of qiliqiangxin unclear among those receiving the current standard of quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy.

She also suggested that it will be important to dissect the relative contribution of the different active ingredients of qiliqiangxin.

“This is not a purified compound that we are used to in Western medicine,” Dr. Lam said. While she praised the study as “scientifically rigorous” and indicated that the results support a clinical benefit from qiliqiangxin, she thinks an exploration of the mechanism or mechanisms of benefit is a next step in understanding where this therapy fits in HFrEF management.

Dr. Li reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Roche, and Yiling. Dr. Lam reports financial relationships with more than 25 pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, many of which produce therapies for heart failure, as well as with Medscape/WebMD Global LLC. The study was supported by the Chinese National Key Research and Development Project and Yiling Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When added to guideline-directed therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), a traditional Chinese medicine called qiliqiangxin reduced the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization by more than 20%, results of a large placebo-controlled trial show.

reported Xinli Li, MD, PhD, First Affiliated Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, China.

Qiliqiangxin, a commonly used therapy in China for cardiovascular disease, is not a single chemical entity but a treatment composed of 11 plant-based substances that together are associated with diuretic effects, vasodilation, and “cardiotonic” activity, Dr. Li said. He also cited studies showing an upregulation effect on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-beta (PGC1-beta).

The results were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Hard endpoints pursued in rigorous design

There have been numerous studies of qiliqiangxin for cardiovascular diseases, including a double-blind study that associated this agent with a greater than 30% reduction in the surrogate endpoint of N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).

In the newly completed multicenter trial, called QUEST, the goal was to determine whether this therapy could reduce hard endpoints relative to placebo in a rigorously conducted trial enrolling patients receiving an optimized triple-therapy heart failure regimen.

Few patients in the study received a sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2 inhibitor), which was not a standard at the time the study was designed but is now part of the quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy in most European and North American guidelines.

In this trial, 3,119 patients were randomly assigned at 133 centers in China to take four capsules of qiliqiangxin or placebo three times per day. At a median follow-up of 18.3 months, outcomes were evaluable in nearly all 1,561 patients randomly assigned to the experimental therapy and 1,555 patients randomly assigned to placebo.

The key inclusion criteria were a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less and a serum NT-proBNP level of at least 450 pg/mL. Patients in New York Heart Association class IV heart failure were excluded.

At enrollment, more than 80% of patients in both arms were receiving a renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitor (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, or angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor), more than 80% were receiving a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, and more than 85% were receiving a beta-blocker.

Death and hospitalization reduced 22%

By hazard ratio, the primary composite endpoint of CV death and heart failure hospitalization was reduced by 22% relative to placebo (HR, 0.78; P < .001). When evaluated separately, the relative reductions in these respective endpoints were 17% (HR, 0.83; P = .045) and 24% (HR, 0.76; P = .002).

The risk reduction was robust (HR, 0.76; P < .001) in patients with an ischemic cause but nonsignificant in those without (HR, 0.92; P = .575). A significant benefit was sustained in patients receiving an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (HR, 0.84; P = .041), as well as those who did not receive this class of drug (HR, 0.77; P = .012).

However, the benefit of qiliqiangxin among patients receiving all components of guideline-directed triple therapy (RAS inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid antagonist) was only a trend (HR, 0.86; P = .079).

All-cause mortality, a secondary endpoint, was lower among patients randomly assigned to qiliqiangxin than to those assigned to placebo, but this difference fell just short of statistical significance (14.21% vs. 16.85%; P = .058).

Qiliqiangxin was well tolerated. The proportion of patients with a serious adverse event was numerically lower with qiliqiangxin than with placebo (17.43% vs. 19.74%), whereas discontinuations associated with an adverse event were numerically higher in the qiliqiangxin group (1.03% vs. 0.58%), albeit still very low in both study arms.

Overlap of drug benefits suspected

Given the safety of this drug and its highly significant reduction in a composite endpoint used in other major HFrEF trials, the ESC-invited discussant, Carolyn S.P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, National Heart Centre, Singapore, called the outcome “remarkable” and a validation for “the millions of people” who are already taking qiliqiangxin in China and other Asian countries.

Using the DAPA-HF trial as a point of reference, Dr. Lam noted that relative reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death for the SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin relative to placebo on top of triple guideline-directed medical therapy was lower (17% vs. 24%), but there were significant reductions in each of the components, as well as a nonsignificant signal of a mortality benefit.

However, Dr. Lam pointed out that there does seem to be more of an overlap for the benefits of qiliqiangxin than dapagliflozin relative to other components of triple therapy based on the lower rate of benefit when patients were optimized on triple therapy.

“The subgroup analysis [of this study] is very important,” Dr. Lam said. Qiliqiangxin may be best in patients who cannot take one or more of the components of triple therapy, she suggested, even though she called for further studies to test this theory. She also cautioned that the pill burden of four capsules taken three times per day might be onerous for some patients.

Of the many questions still to be answered, Dr. Lam noted that the low rate of enrollment for patients (< 10%) taking SGLT-2 inhibitors makes the contribution of qiliqiangxin unclear among those receiving the current standard of quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy.

She also suggested that it will be important to dissect the relative contribution of the different active ingredients of qiliqiangxin.

“This is not a purified compound that we are used to in Western medicine,” Dr. Lam said. While she praised the study as “scientifically rigorous” and indicated that the results support a clinical benefit from qiliqiangxin, she thinks an exploration of the mechanism or mechanisms of benefit is a next step in understanding where this therapy fits in HFrEF management.

Dr. Li reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Roche, and Yiling. Dr. Lam reports financial relationships with more than 25 pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, many of which produce therapies for heart failure, as well as with Medscape/WebMD Global LLC. The study was supported by the Chinese National Key Research and Development Project and Yiling Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2023

No reduction in AFib after noncardiac surgery with colchicine: COP-AF

Trends were seen with reductions in events, but these did not reach significance. However, benefit was seen in a post-hoc analysis looking at a composite of both of those endpoints, the researchers note, as well as a composite of vascular death, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important perioperative AFib, the researchers report.

“We interpret that as there is a trend that is promising, a trend that needs to be further explored,” lead author David Conen, MD, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “We think that further studies are needed to tease out which patients can benefit from colchicine and in what setting it can be used.”

Treatment was safe, with no effect on the risk for sepsis or infection, but it did cause an increase in noninfectious diarrhea. “These events were mostly benign and did not increase length of stay, and only one patient was readmitted because of diarrhea,” Dr. Conen noted.

Results of the COP-AF trial were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, Amsterdam, and published online in The Lancet .

Inflammation and perioperative AFib

AFib and MINS are common complications in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery, Dr. Conen explained. The literature suggests AFib occurs in about 10% and MINS in about 20% of these patients, “and patients with these complications have a much higher risk of additional complications, such as stroke or MI [myocardial infarction],” Dr. Conen said.

Both disorders are associated with high levels of inflammatory biomarkers, so they set out to test colchicine, a well-known anti-inflammatory drug used in higher doses to treat common clinical disorders, such as gout and pericarditis. Small, randomized trials had shown it reduced the incidence of perioperative AFib after cardiac surgery, he noted.

Low-dose colchicine (LoDoCo, Agepha Pharma) was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk for MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, or death in patients with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It was approved on the basis of the LoDoCo 2 trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease and the COLCOT trial in patients with recent MI.

COP-AF was a randomized trial, conducted at 45 sites in 11 countries, and enrolled 3,209 patients aged 55 years or older (51.6% male) undergoing major noncardiac thoracic surgery. Patients were excluded if they had previous AFib, had any contraindications to colchicine, or required colchicine on a clinical basis.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive oral colchicine at a dose of 0.5 mg twice daily (1,608 patients) or placebo (1,601 patients). Treatment was begun within 4 hours before surgery and continued for 10 days. Health care providers and patients, as well as data collectors and adjudicators, were blinded to treatment assignment.

The co-primary outcomes were clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS over 14 days of follow-up. The trial was originally looking only at clinically important AFib, Dr. Conen noted, but after the publication of LoDoCo 2 and COLCOT, “MINS was added as an independent co-primary outcome,” requiring more patients to achieve adequate power.

The main safety outcomes were a composite of sepsis or infection, along with noninfectious diarrhea.

Clinically important AFib was defined as AFib that results in angina, heart failure, or symptomatic hypotension or required treatment with a rate-controlling drug, antiarrhythmic drug, or electrical cardioversion. “This definition was chosen because of its prognostic relevance, and to avoid adding short, asymptomatic AFib episodes of uncertain clinical relevance to the primary outcome,” Dr. Conen said during his presentation.

MINS was defined as an MI or any postoperative troponin elevation that was judged by an adjudication panel to be of ischemic origin.

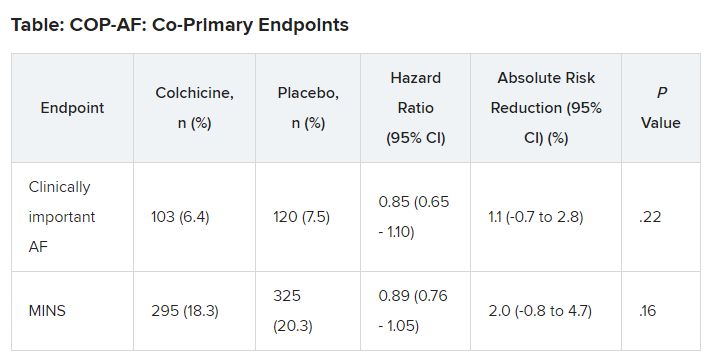

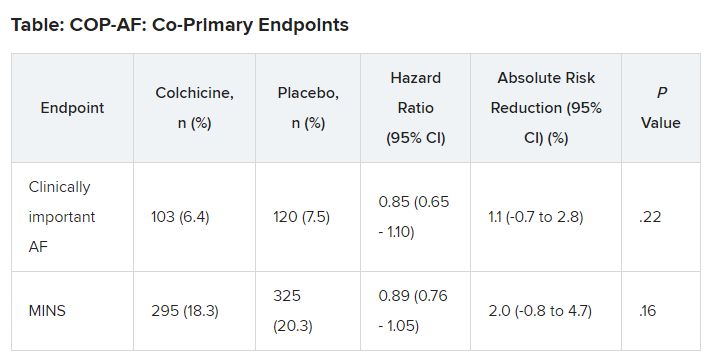

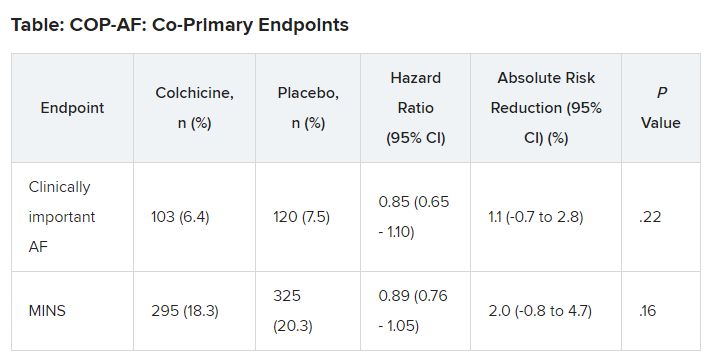

At 14 days, there was no significant difference between groups on either of the co-primary end points.

No significant differences but positive trends were similarly seen in secondary outcomes of a composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MINS, and nonfatal stroke; the composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke; MINS not fulfilling the fourth universal definition of MI; or MI.

There were no differences in time to chest tube removal, days in hospital, nights in the step-down unit, or nights in the intensive care unit.

In terms of safety, there was no difference between groups on sepsis or infection, which occurred in 6.4% of patients in the colchicine group and 5.2% of those in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.66).

Noninfectious diarrhea was more common with colchicine, with 134 events (8.3%) versus 38 with placebo (2.4%), for an HR of 3.64 (95% CI, 2.54-5.22).

“In two post hoc analyses, colchicine significantly reduced the composite of the two co-primary outcomes,” Dr. Conen noted in his presentation. Clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS occurred in 22.4% in the colchicine group and 25.9% in the placebo group (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02).

“Colchicine also significantly reduced the composite of vascular mortality, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important AFib,” he said; 22.6% of patients in the colchicine group had one of these events versus 26.4% of those in the placebo group (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.96; P = .01).

The researchers also reported significant interactions on both co-primary outcomes for the type of incision, “suggesting that stronger and statistically significant effects among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery as opposed to nonthoracoscopic surgery,” Dr. Conen said.

Patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery treated with colchicine had a reduced risk for clinically important AFib (n = 2,397; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.77), but colchicine treatment increased the risk in patients having open surgery (n = 784; HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.07-2.35; P for interaction < .0001).

There was a beneficial effect on MINS with colchicine among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), but no effect was seen among those having open surgery (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.87-1.53; P for interaction = .041).

Low-risk patients

Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, Montreal Heart Institute and Université de Montréal, was the invited discussant for the COP-AF presentation and congratulated the researchers on “a job well done.”

He made the point that the risk for perioperative AFib has decreased substantially with the greater use of thoracoscopic rather than open surgical approaches. The population of this trial was relatively young, with an average age of 68 years; the presence of concomitant CVD was low, at about 9%; by design, patients with previous AFib were excluded; and only about 20% of patients had surgery with an open approach.

“So that population of patients were probably at relatively low risk of atrial fibrillation, and sure enough, the incidence of perioperative AFib in that population at 7.5% was lower than the assumed rate in the statistical powering of the study at 9%,” Dr. Tardif noted.

The post-hoc analyses showed a “nominally significant effect on the composite of MINS and AFib; however, that combination is fairly difficult to justify given the different pathophysiology and clinical consequences of both outcomes,” he pointed out.

The incidence of postoperative MI as a secondary outcome was low, less than 1%, as was the incidence of postoperative stroke in that study, Dr. Tardif added. “Given the link between presence of blood in the pericardium as a trigger for AFib, it would be interesting to know the incidence of perioperative pericarditis in COP-AF.”

In conclusion, he said, “when trying to put these results into the bigger picture of colchicine in cardiovascular disease, I believe we need large, well-powered clinical trials to determine the value of colchicine to reduce the risk of AFib after cardiac surgery and after catheter ablation,” Dr. Tardif said.

“We all know that colchicine represents the first line of therapy for the treatment of acute and recurrent pericarditis, and finally, low-dose colchicine, at a lower dose than was used in COP-AF, 0.5 mg once daily, is the first anti-inflammatory agent approved by both U.S. FDA and Health Canada to reduce the risk of atherothombotic events in patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease], I believe offering a new pillar of treatment for the prevention of ischemic events in such patients.”

Session co-moderator Franz Weidinger, MD, Landstrasse Clinic, Vienna, Austria, called the COP-AF results “very important” but also noted that they show “the challenge of doing well-powered randomized trials these days when we have patients so well treated for a wide array of cardiovascular disease.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); Accelerating Clinical Trials Consortium; Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan for the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario; Population Health Research Institute; Hamilton Health Sciences; Division of Cardiology at McMaster University, Canada; Hanela Foundation, Switzerland; and General Research Fund, Research Grants Council, Hong Kong. Dr. Conen reports receiving research grants from CIHR, speaker fees from Servier outside the current study, and advisory board fees from Roche Diagnostics and Trimedics outside the current study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Trends were seen with reductions in events, but these did not reach significance. However, benefit was seen in a post-hoc analysis looking at a composite of both of those endpoints, the researchers note, as well as a composite of vascular death, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important perioperative AFib, the researchers report.

“We interpret that as there is a trend that is promising, a trend that needs to be further explored,” lead author David Conen, MD, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “We think that further studies are needed to tease out which patients can benefit from colchicine and in what setting it can be used.”

Treatment was safe, with no effect on the risk for sepsis or infection, but it did cause an increase in noninfectious diarrhea. “These events were mostly benign and did not increase length of stay, and only one patient was readmitted because of diarrhea,” Dr. Conen noted.

Results of the COP-AF trial were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, Amsterdam, and published online in The Lancet .

Inflammation and perioperative AFib

AFib and MINS are common complications in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery, Dr. Conen explained. The literature suggests AFib occurs in about 10% and MINS in about 20% of these patients, “and patients with these complications have a much higher risk of additional complications, such as stroke or MI [myocardial infarction],” Dr. Conen said.

Both disorders are associated with high levels of inflammatory biomarkers, so they set out to test colchicine, a well-known anti-inflammatory drug used in higher doses to treat common clinical disorders, such as gout and pericarditis. Small, randomized trials had shown it reduced the incidence of perioperative AFib after cardiac surgery, he noted.

Low-dose colchicine (LoDoCo, Agepha Pharma) was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk for MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, or death in patients with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It was approved on the basis of the LoDoCo 2 trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease and the COLCOT trial in patients with recent MI.

COP-AF was a randomized trial, conducted at 45 sites in 11 countries, and enrolled 3,209 patients aged 55 years or older (51.6% male) undergoing major noncardiac thoracic surgery. Patients were excluded if they had previous AFib, had any contraindications to colchicine, or required colchicine on a clinical basis.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive oral colchicine at a dose of 0.5 mg twice daily (1,608 patients) or placebo (1,601 patients). Treatment was begun within 4 hours before surgery and continued for 10 days. Health care providers and patients, as well as data collectors and adjudicators, were blinded to treatment assignment.

The co-primary outcomes were clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS over 14 days of follow-up. The trial was originally looking only at clinically important AFib, Dr. Conen noted, but after the publication of LoDoCo 2 and COLCOT, “MINS was added as an independent co-primary outcome,” requiring more patients to achieve adequate power.

The main safety outcomes were a composite of sepsis or infection, along with noninfectious diarrhea.

Clinically important AFib was defined as AFib that results in angina, heart failure, or symptomatic hypotension or required treatment with a rate-controlling drug, antiarrhythmic drug, or electrical cardioversion. “This definition was chosen because of its prognostic relevance, and to avoid adding short, asymptomatic AFib episodes of uncertain clinical relevance to the primary outcome,” Dr. Conen said during his presentation.

MINS was defined as an MI or any postoperative troponin elevation that was judged by an adjudication panel to be of ischemic origin.

At 14 days, there was no significant difference between groups on either of the co-primary end points.

No significant differences but positive trends were similarly seen in secondary outcomes of a composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MINS, and nonfatal stroke; the composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke; MINS not fulfilling the fourth universal definition of MI; or MI.

There were no differences in time to chest tube removal, days in hospital, nights in the step-down unit, or nights in the intensive care unit.

In terms of safety, there was no difference between groups on sepsis or infection, which occurred in 6.4% of patients in the colchicine group and 5.2% of those in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.66).

Noninfectious diarrhea was more common with colchicine, with 134 events (8.3%) versus 38 with placebo (2.4%), for an HR of 3.64 (95% CI, 2.54-5.22).

“In two post hoc analyses, colchicine significantly reduced the composite of the two co-primary outcomes,” Dr. Conen noted in his presentation. Clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS occurred in 22.4% in the colchicine group and 25.9% in the placebo group (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02).

“Colchicine also significantly reduced the composite of vascular mortality, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important AFib,” he said; 22.6% of patients in the colchicine group had one of these events versus 26.4% of those in the placebo group (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.96; P = .01).

The researchers also reported significant interactions on both co-primary outcomes for the type of incision, “suggesting that stronger and statistically significant effects among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery as opposed to nonthoracoscopic surgery,” Dr. Conen said.

Patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery treated with colchicine had a reduced risk for clinically important AFib (n = 2,397; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.77), but colchicine treatment increased the risk in patients having open surgery (n = 784; HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.07-2.35; P for interaction < .0001).

There was a beneficial effect on MINS with colchicine among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), but no effect was seen among those having open surgery (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.87-1.53; P for interaction = .041).

Low-risk patients

Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, Montreal Heart Institute and Université de Montréal, was the invited discussant for the COP-AF presentation and congratulated the researchers on “a job well done.”

He made the point that the risk for perioperative AFib has decreased substantially with the greater use of thoracoscopic rather than open surgical approaches. The population of this trial was relatively young, with an average age of 68 years; the presence of concomitant CVD was low, at about 9%; by design, patients with previous AFib were excluded; and only about 20% of patients had surgery with an open approach.

“So that population of patients were probably at relatively low risk of atrial fibrillation, and sure enough, the incidence of perioperative AFib in that population at 7.5% was lower than the assumed rate in the statistical powering of the study at 9%,” Dr. Tardif noted.

The post-hoc analyses showed a “nominally significant effect on the composite of MINS and AFib; however, that combination is fairly difficult to justify given the different pathophysiology and clinical consequences of both outcomes,” he pointed out.

The incidence of postoperative MI as a secondary outcome was low, less than 1%, as was the incidence of postoperative stroke in that study, Dr. Tardif added. “Given the link between presence of blood in the pericardium as a trigger for AFib, it would be interesting to know the incidence of perioperative pericarditis in COP-AF.”

In conclusion, he said, “when trying to put these results into the bigger picture of colchicine in cardiovascular disease, I believe we need large, well-powered clinical trials to determine the value of colchicine to reduce the risk of AFib after cardiac surgery and after catheter ablation,” Dr. Tardif said.

“We all know that colchicine represents the first line of therapy for the treatment of acute and recurrent pericarditis, and finally, low-dose colchicine, at a lower dose than was used in COP-AF, 0.5 mg once daily, is the first anti-inflammatory agent approved by both U.S. FDA and Health Canada to reduce the risk of atherothombotic events in patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease], I believe offering a new pillar of treatment for the prevention of ischemic events in such patients.”

Session co-moderator Franz Weidinger, MD, Landstrasse Clinic, Vienna, Austria, called the COP-AF results “very important” but also noted that they show “the challenge of doing well-powered randomized trials these days when we have patients so well treated for a wide array of cardiovascular disease.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); Accelerating Clinical Trials Consortium; Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan for the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario; Population Health Research Institute; Hamilton Health Sciences; Division of Cardiology at McMaster University, Canada; Hanela Foundation, Switzerland; and General Research Fund, Research Grants Council, Hong Kong. Dr. Conen reports receiving research grants from CIHR, speaker fees from Servier outside the current study, and advisory board fees from Roche Diagnostics and Trimedics outside the current study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Trends were seen with reductions in events, but these did not reach significance. However, benefit was seen in a post-hoc analysis looking at a composite of both of those endpoints, the researchers note, as well as a composite of vascular death, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important perioperative AFib, the researchers report.

“We interpret that as there is a trend that is promising, a trend that needs to be further explored,” lead author David Conen, MD, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “We think that further studies are needed to tease out which patients can benefit from colchicine and in what setting it can be used.”

Treatment was safe, with no effect on the risk for sepsis or infection, but it did cause an increase in noninfectious diarrhea. “These events were mostly benign and did not increase length of stay, and only one patient was readmitted because of diarrhea,” Dr. Conen noted.

Results of the COP-AF trial were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, Amsterdam, and published online in The Lancet .

Inflammation and perioperative AFib

AFib and MINS are common complications in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery, Dr. Conen explained. The literature suggests AFib occurs in about 10% and MINS in about 20% of these patients, “and patients with these complications have a much higher risk of additional complications, such as stroke or MI [myocardial infarction],” Dr. Conen said.

Both disorders are associated with high levels of inflammatory biomarkers, so they set out to test colchicine, a well-known anti-inflammatory drug used in higher doses to treat common clinical disorders, such as gout and pericarditis. Small, randomized trials had shown it reduced the incidence of perioperative AFib after cardiac surgery, he noted.

Low-dose colchicine (LoDoCo, Agepha Pharma) was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk for MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, or death in patients with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It was approved on the basis of the LoDoCo 2 trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease and the COLCOT trial in patients with recent MI.

COP-AF was a randomized trial, conducted at 45 sites in 11 countries, and enrolled 3,209 patients aged 55 years or older (51.6% male) undergoing major noncardiac thoracic surgery. Patients were excluded if they had previous AFib, had any contraindications to colchicine, or required colchicine on a clinical basis.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive oral colchicine at a dose of 0.5 mg twice daily (1,608 patients) or placebo (1,601 patients). Treatment was begun within 4 hours before surgery and continued for 10 days. Health care providers and patients, as well as data collectors and adjudicators, were blinded to treatment assignment.

The co-primary outcomes were clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS over 14 days of follow-up. The trial was originally looking only at clinically important AFib, Dr. Conen noted, but after the publication of LoDoCo 2 and COLCOT, “MINS was added as an independent co-primary outcome,” requiring more patients to achieve adequate power.

The main safety outcomes were a composite of sepsis or infection, along with noninfectious diarrhea.

Clinically important AFib was defined as AFib that results in angina, heart failure, or symptomatic hypotension or required treatment with a rate-controlling drug, antiarrhythmic drug, or electrical cardioversion. “This definition was chosen because of its prognostic relevance, and to avoid adding short, asymptomatic AFib episodes of uncertain clinical relevance to the primary outcome,” Dr. Conen said during his presentation.

MINS was defined as an MI or any postoperative troponin elevation that was judged by an adjudication panel to be of ischemic origin.

At 14 days, there was no significant difference between groups on either of the co-primary end points.

No significant differences but positive trends were similarly seen in secondary outcomes of a composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MINS, and nonfatal stroke; the composite of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke; MINS not fulfilling the fourth universal definition of MI; or MI.

There were no differences in time to chest tube removal, days in hospital, nights in the step-down unit, or nights in the intensive care unit.

In terms of safety, there was no difference between groups on sepsis or infection, which occurred in 6.4% of patients in the colchicine group and 5.2% of those in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.66).

Noninfectious diarrhea was more common with colchicine, with 134 events (8.3%) versus 38 with placebo (2.4%), for an HR of 3.64 (95% CI, 2.54-5.22).

“In two post hoc analyses, colchicine significantly reduced the composite of the two co-primary outcomes,” Dr. Conen noted in his presentation. Clinically important perioperative AFib or MINS occurred in 22.4% in the colchicine group and 25.9% in the placebo group (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02).

“Colchicine also significantly reduced the composite of vascular mortality, nonfatal MINS, nonfatal stroke, and clinically important AFib,” he said; 22.6% of patients in the colchicine group had one of these events versus 26.4% of those in the placebo group (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.96; P = .01).

The researchers also reported significant interactions on both co-primary outcomes for the type of incision, “suggesting that stronger and statistically significant effects among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery as opposed to nonthoracoscopic surgery,” Dr. Conen said.

Patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery treated with colchicine had a reduced risk for clinically important AFib (n = 2,397; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36-0.77), but colchicine treatment increased the risk in patients having open surgery (n = 784; HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.07-2.35; P for interaction < .0001).

There was a beneficial effect on MINS with colchicine among patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), but no effect was seen among those having open surgery (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.87-1.53; P for interaction = .041).

Low-risk patients

Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, Montreal Heart Institute and Université de Montréal, was the invited discussant for the COP-AF presentation and congratulated the researchers on “a job well done.”

He made the point that the risk for perioperative AFib has decreased substantially with the greater use of thoracoscopic rather than open surgical approaches. The population of this trial was relatively young, with an average age of 68 years; the presence of concomitant CVD was low, at about 9%; by design, patients with previous AFib were excluded; and only about 20% of patients had surgery with an open approach.

“So that population of patients were probably at relatively low risk of atrial fibrillation, and sure enough, the incidence of perioperative AFib in that population at 7.5% was lower than the assumed rate in the statistical powering of the study at 9%,” Dr. Tardif noted.

The post-hoc analyses showed a “nominally significant effect on the composite of MINS and AFib; however, that combination is fairly difficult to justify given the different pathophysiology and clinical consequences of both outcomes,” he pointed out.

The incidence of postoperative MI as a secondary outcome was low, less than 1%, as was the incidence of postoperative stroke in that study, Dr. Tardif added. “Given the link between presence of blood in the pericardium as a trigger for AFib, it would be interesting to know the incidence of perioperative pericarditis in COP-AF.”

In conclusion, he said, “when trying to put these results into the bigger picture of colchicine in cardiovascular disease, I believe we need large, well-powered clinical trials to determine the value of colchicine to reduce the risk of AFib after cardiac surgery and after catheter ablation,” Dr. Tardif said.

“We all know that colchicine represents the first line of therapy for the treatment of acute and recurrent pericarditis, and finally, low-dose colchicine, at a lower dose than was used in COP-AF, 0.5 mg once daily, is the first anti-inflammatory agent approved by both U.S. FDA and Health Canada to reduce the risk of atherothombotic events in patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease], I believe offering a new pillar of treatment for the prevention of ischemic events in such patients.”

Session co-moderator Franz Weidinger, MD, Landstrasse Clinic, Vienna, Austria, called the COP-AF results “very important” but also noted that they show “the challenge of doing well-powered randomized trials these days when we have patients so well treated for a wide array of cardiovascular disease.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); Accelerating Clinical Trials Consortium; Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan for the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario; Population Health Research Institute; Hamilton Health Sciences; Division of Cardiology at McMaster University, Canada; Hanela Foundation, Switzerland; and General Research Fund, Research Grants Council, Hong Kong. Dr. Conen reports receiving research grants from CIHR, speaker fees from Servier outside the current study, and advisory board fees from Roche Diagnostics and Trimedics outside the current study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2023

ESC backs SGLT2 inhibitor plus GLP-1 in diabetes with high CVD risk

AMSTERDAM – The era of guidelines that recommended treatment with either a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor or a glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established cardiovascular disease (CVD) ended with new recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology that call for starting both classes simultaneously.

said Darren K. McGuire, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The society’s new guidelines for managing CVD in patients with diabetes, released on Aug. 25 and presented in several sessions at the Congress, also break with the past by calling for starting treatment with both an SGLT-2 inhibitor and a GLP-1 receptor agonist without regard to a person’s existing level of glucose control, including their current and target hemoglobin A1c levels, and regardless of background therapy, added Dr. McGuire, a cardiologist and professor at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and a member of the ESC panel that wrote the new guidelines.

Instead, the new guidance calls for starting both drug classes promptly in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic CVD.

Both the previous ESC guidelines from 2019 as well as the current Standards of Care for 2023 document from the American Diabetes Association call for using one class or the other, but they hedge on combined treatment as discretionary.

Different mechanisms mean additive benefits

“With increasing numbers of patients with type 2 diabetes in trials for SGLT-2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists who were also on the other drug class, we’ve done large, stratified analyses that suggest no treatment-effect modification” when people received agents from both drug classes, Dr. McGuire explained in an interview. “While we don’t understand the mechanisms of action of these drugs for CVD, we’ve become very confident that they use different mechanisms” that appear to have at least partially additive effects.

“Their benefits for CVD risk reduction are completely independent of their glucose effects. They are cardiology drugs,” Dr. McGuire added.

The new ESC guidelines highlight two other clinical settings where people with type 2 diabetes should receive an SGLT-2 inhibitor regardless of their existing level of glucose control and any other medical treatment: people with heart failure and people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) based on a depressed estimated glomerular filtration rate and an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Nephropathy was considered by the ESC’s guideline panel to confer risk that is similar to that of established atherosclerotic CVD, Dr. McGuire said.

The guidelines also, for the first time for ESC recommendations, made treatment with finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) a class 1 level A recommendation for people with type 2 diabetes and CKD.

SCORE2-Diabetes risk estimator

Another major change in the new ESC guideline revision is introduction of a CVD risk calculator intended to estimate the risk among people with type 2 diabetes but without established CVD, heart failure, or CKD.

Called the SCORE2-Diabetes risk estimator, it calculates a person’s 10-year risk for CVD and includes adjustment based on the European region where a person lives; it also tallies different risk levels for women and for men.

The researchers who developed the SCORE2-Diabetes calculator used data from nearly 230,000 people to devise the tool and then validated it with data from an additional 217,000 Europeans with type 2 diabetes.

Key features of the calculator include its use of routinely collected clinical values, such as age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, serum cholesterol levels, age at diabetes diagnosis, hemoglobin A1c level, and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

“For the first time we have a clear score to categorize risk” in people with type 2 diabetes and identify who needs more aggressive treatment to prevent CVD development,” said Emanuele Di Angelantonio, MD, PhD, deputy director of the cardiovascular epidemiology unit at the University of Cambridge (England).

The guidelines say that people who have a low (< 5%) or moderate (5%-9%) 10-year risk for CVD are possible candidates for metformin treatment. Those with high (10%-19%) or very high (≥ 20%) risk are possible candidates for treatment with metformin and/or an SGLT-2 inhibitor and/or a GLP-1 receptor agonist, said Dr. Di Angelantonio during his talk at the congress on the new risk score.

“The risk score is a good addition” because it estimates future CVD risk better and more systematically than usual practice, which generally relies on no systematic tool, said Naveed Sattar, PhD, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow (Scotland) and also a member of the guideline-writing panel.

The new risk score “is a reasonable way” to identify people without CVD but at elevated risk who might benefit from treatment with a relatively expensive drug, such as an SGLT-2 inhibitor, Dr. Sattar said in an interview. “It doesn’t rely on any fancy biomarkers or imaging, and it takes about 30 seconds to calculate. It’s not perfect, but it gets the job done,” and it will increase the number of people with type 2 diabetes who will receive an SGLT-2 inhibitor, he predicted.

Dr. McGuire has been a consultant to Altimmune, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Intercept, Lexion, Lilly, Merck, New Amsterdam, and Pfizer. Dr. Di Angelantonio had no disclosures. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AMSTERDAM – The era of guidelines that recommended treatment with either a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor or a glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established cardiovascular disease (CVD) ended with new recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology that call for starting both classes simultaneously.

said Darren K. McGuire, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The society’s new guidelines for managing CVD in patients with diabetes, released on Aug. 25 and presented in several sessions at the Congress, also break with the past by calling for starting treatment with both an SGLT-2 inhibitor and a GLP-1 receptor agonist without regard to a person’s existing level of glucose control, including their current and target hemoglobin A1c levels, and regardless of background therapy, added Dr. McGuire, a cardiologist and professor at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and a member of the ESC panel that wrote the new guidelines.

Instead, the new guidance calls for starting both drug classes promptly in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic CVD.

Both the previous ESC guidelines from 2019 as well as the current Standards of Care for 2023 document from the American Diabetes Association call for using one class or the other, but they hedge on combined treatment as discretionary.

Different mechanisms mean additive benefits

“With increasing numbers of patients with type 2 diabetes in trials for SGLT-2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists who were also on the other drug class, we’ve done large, stratified analyses that suggest no treatment-effect modification” when people received agents from both drug classes, Dr. McGuire explained in an interview. “While we don’t understand the mechanisms of action of these drugs for CVD, we’ve become very confident that they use different mechanisms” that appear to have at least partially additive effects.

“Their benefits for CVD risk reduction are completely independent of their glucose effects. They are cardiology drugs,” Dr. McGuire added.

The new ESC guidelines highlight two other clinical settings where people with type 2 diabetes should receive an SGLT-2 inhibitor regardless of their existing level of glucose control and any other medical treatment: people with heart failure and people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) based on a depressed estimated glomerular filtration rate and an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Nephropathy was considered by the ESC’s guideline panel to confer risk that is similar to that of established atherosclerotic CVD, Dr. McGuire said.

The guidelines also, for the first time for ESC recommendations, made treatment with finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) a class 1 level A recommendation for people with type 2 diabetes and CKD.

SCORE2-Diabetes risk estimator

Another major change in the new ESC guideline revision is introduction of a CVD risk calculator intended to estimate the risk among people with type 2 diabetes but without established CVD, heart failure, or CKD.

Called the SCORE2-Diabetes risk estimator, it calculates a person’s 10-year risk for CVD and includes adjustment based on the European region where a person lives; it also tallies different risk levels for women and for men.

The researchers who developed the SCORE2-Diabetes calculator used data from nearly 230,000 people to devise the tool and then validated it with data from an additional 217,000 Europeans with type 2 diabetes.

Key features of the calculator include its use of routinely collected clinical values, such as age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, serum cholesterol levels, age at diabetes diagnosis, hemoglobin A1c level, and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

“For the first time we have a clear score to categorize risk” in people with type 2 diabetes and identify who needs more aggressive treatment to prevent CVD development,” said Emanuele Di Angelantonio, MD, PhD, deputy director of the cardiovascular epidemiology unit at the University of Cambridge (England).

The guidelines say that people who have a low (< 5%) or moderate (5%-9%) 10-year risk for CVD are possible candidates for metformin treatment. Those with high (10%-19%) or very high (≥ 20%) risk are possible candidates for treatment with metformin and/or an SGLT-2 inhibitor and/or a GLP-1 receptor agonist, said Dr. Di Angelantonio during his talk at the congress on the new risk score.

“The risk score is a good addition” because it estimates future CVD risk better and more systematically than usual practice, which generally relies on no systematic tool, said Naveed Sattar, PhD, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow (Scotland) and also a member of the guideline-writing panel.

The new risk score “is a reasonable way” to identify people without CVD but at elevated risk who might benefit from treatment with a relatively expensive drug, such as an SGLT-2 inhibitor, Dr. Sattar said in an interview. “It doesn’t rely on any fancy biomarkers or imaging, and it takes about 30 seconds to calculate. It’s not perfect, but it gets the job done,” and it will increase the number of people with type 2 diabetes who will receive an SGLT-2 inhibitor, he predicted.

Dr. McGuire has been a consultant to Altimmune, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Intercept, Lexion, Lilly, Merck, New Amsterdam, and Pfizer. Dr. Di Angelantonio had no disclosures. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AMSTERDAM – The era of guidelines that recommended treatment with either a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor or a glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established cardiovascular disease (CVD) ended with new recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology that call for starting both classes simultaneously.

said Darren K. McGuire, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The society’s new guidelines for managing CVD in patients with diabetes, released on Aug. 25 and presented in several sessions at the Congress, also break with the past by calling for starting treatment with both an SGLT-2 inhibitor and a GLP-1 receptor agonist without regard to a person’s existing level of glucose control, including their current and target hemoglobin A1c levels, and regardless of background therapy, added Dr. McGuire, a cardiologist and professor at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and a member of the ESC panel that wrote the new guidelines.

Instead, the new guidance calls for starting both drug classes promptly in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic CVD.

Both the previous ESC guidelines from 2019 as well as the current Standards of Care for 2023 document from the American Diabetes Association call for using one class or the other, but they hedge on combined treatment as discretionary.

Different mechanisms mean additive benefits

“With increasing numbers of patients with type 2 diabetes in trials for SGLT-2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists who were also on the other drug class, we’ve done large, stratified analyses that suggest no treatment-effect modification” when people received agents from both drug classes, Dr. McGuire explained in an interview. “While we don’t understand the mechanisms of action of these drugs for CVD, we’ve become very confident that they use different mechanisms” that appear to have at least partially additive effects.

“Their benefits for CVD risk reduction are completely independent of their glucose effects. They are cardiology drugs,” Dr. McGuire added.

The new ESC guidelines highlight two other clinical settings where people with type 2 diabetes should receive an SGLT-2 inhibitor regardless of their existing level of glucose control and any other medical treatment: people with heart failure and people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) based on a depressed estimated glomerular filtration rate and an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Nephropathy was considered by the ESC’s guideline panel to confer risk that is similar to that of established atherosclerotic CVD, Dr. McGuire said.

The guidelines also, for the first time for ESC recommendations, made treatment with finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) a class 1 level A recommendation for people with type 2 diabetes and CKD.

SCORE2-Diabetes risk estimator

Another major change in the new ESC guideline revision is introduction of a CVD risk calculator intended to estimate the risk among people with type 2 diabetes but without established CVD, heart failure, or CKD.

Called the SCORE2-Diabetes risk estimator, it calculates a person’s 10-year risk for CVD and includes adjustment based on the European region where a person lives; it also tallies different risk levels for women and for men.

The researchers who developed the SCORE2-Diabetes calculator used data from nearly 230,000 people to devise the tool and then validated it with data from an additional 217,000 Europeans with type 2 diabetes.

Key features of the calculator include its use of routinely collected clinical values, such as age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, serum cholesterol levels, age at diabetes diagnosis, hemoglobin A1c level, and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

“For the first time we have a clear score to categorize risk” in people with type 2 diabetes and identify who needs more aggressive treatment to prevent CVD development,” said Emanuele Di Angelantonio, MD, PhD, deputy director of the cardiovascular epidemiology unit at the University of Cambridge (England).

The guidelines say that people who have a low (< 5%) or moderate (5%-9%) 10-year risk for CVD are possible candidates for metformin treatment. Those with high (10%-19%) or very high (≥ 20%) risk are possible candidates for treatment with metformin and/or an SGLT-2 inhibitor and/or a GLP-1 receptor agonist, said Dr. Di Angelantonio during his talk at the congress on the new risk score.

“The risk score is a good addition” because it estimates future CVD risk better and more systematically than usual practice, which generally relies on no systematic tool, said Naveed Sattar, PhD, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow (Scotland) and also a member of the guideline-writing panel.

The new risk score “is a reasonable way” to identify people without CVD but at elevated risk who might benefit from treatment with a relatively expensive drug, such as an SGLT-2 inhibitor, Dr. Sattar said in an interview. “It doesn’t rely on any fancy biomarkers or imaging, and it takes about 30 seconds to calculate. It’s not perfect, but it gets the job done,” and it will increase the number of people with type 2 diabetes who will receive an SGLT-2 inhibitor, he predicted.

Dr. McGuire has been a consultant to Altimmune, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Intercept, Lexion, Lilly, Merck, New Amsterdam, and Pfizer. Dr. Di Angelantonio had no disclosures. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ESC CONGRESS 2023

Liraglutide fixes learning limit tied to insulin resistance

A single injection of the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide led to short-term normalization of associative learning in people with obesity and insulin resistance, a finding that suggests say the authors of a recent report in Nature Metabolism.

“We demonstrated that dopamine-driven associative learning about external sensory cues crucially depends on metabolic signaling,” said Marc Tittgemeyer, PhD, professor at the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research in Cologne, Germany, and senior author of the study. Study participants with impaired insulin sensitivity “exhibited a reduced amplitude of behavioral updating that was normalized” by a single subcutaneous injection of 0.6 mg of liraglutide (the starting daily dose for liraglutide for weight loss, available as Saxenda, Novo Nordisk) given the evening before testing.

The findings, from 30 adults with normal insulin sensitivity and normal weight and 24 adults with impaired insulin sensitivity and obesity, suggest that metabolic signals, particularly ones that promote energy restoration in a setting of energy deprivation caused by insulin or a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, “profoundly influence neuronal processing,” said Dr. Tittgemeyer. The findings suggest that impaired metabolic signaling such as occurs with insulin resistance in people with obesity can cause deficiencies in associative learning.

‘Liraglutide can normalize learning of associations’

“We show that in people with obesity, disrupted circuit mechanisms lead to impaired learning about sensory associations,” Dr. Tittgemeyer said in an interview. “The information provided by sensory systems that the brain must interpret to select a behavioral response are ‘off tune’ ” in these individuals.

“This is rather consequential for understanding food-intake behaviors. Modern obesity treatments, such as liraglutide, can normalize learning of associations and thereby render people susceptible again for sensory signals and make them more prone to react to subliminal interactions, such as weight-normalizing diets and conscious eating,” he added.

The normalization in associative learning that one dose of liraglutide produced in people with obesity “fits with studies showing that these drugs restore a normal feeling of satiety, causing people to eat less and therefore lose weight,” he explained.

Dr. Tittgemeyer noted that this effect is likely shared by other agents in the GLP-1 receptor agonist class, such as semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Novo Nordisk) but is likely not an effect when agents agonize receptors to other nutrient-stimulated hormones such as glucagon and the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide.

The findings “show that liraglutide restores associative learning in participants with greater insulin resistance,” a “highly relevant” discovery, commented Nils B. Kroemer, PhD, head of the section of medical psychology at the University of Bonn, Germany, who was not involved with this research, in a written statement.

The study run by Dr. Tittgemeyer and his associates included 54 healthy adult volunteers whom they assessed for insulin sensitivity with their homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. The researchers divided the cohort into groups; one group included 24 people with impaired insulin sensitivity, and one included 30 with normal insulin sensitivity. The average body mass index (BMI) of the normal sensitivity group was about 24 kg/m2; in the insulin-resistant subgroup, BMI averaged about 33 kg/m2.

The associative learning task tested the ability of participants to learn associations between auditory cues (a high or low tone) and a subsequent visual outcome (a picture of a face or a house). During each associative learning session, participants also underwent functional MRI of the brain.

Liraglutide treatment leveled learning

The results showed that the learning rate was significantly lower in the subgroup with impaired insulin sensitivity, compared with those with normal insulin sensitivity following treatment with a placebo injection. This indicates a decreased adaptation of learning to predictability variations in individuals with impaired insulin sensitivity.

In contrast, treatment with a single dose of liraglutide significantly enhanced the learning rate in the group with impaired insulin sensitivity but significantly reduced the learning rate in the group with normal insulin sensitivity. Liraglutide’s effect was twice as large in the group with impaired insulin sensitivity than in the group with normal insulin sensitivity, and these opposing effects of liraglutide resulted in a convergence of the two groups’ adaptive learning rates so that there wasn’t any significant between-group difference following liraglutide treatment.

After analyzing the functional MRI data along with the learning results, the researchers concluded that liraglutide normalized learning in individuals with impaired insulin sensitivity by enhancing adaptive prediction error encoding in the brain’s ventral striatum and mesocortical projection sites.

This apparent ability of GLP-1 analogues to correct this learning deficit in people with impaired insulin sensitivity and obesity has implications regarding potential benefit for people with other pathologies characterized by impaired dopaminergic function and associated with metabolic impairments, such as psychosis, Parkinson’s disease, and depression, the researchers say.

“The fascinating thing about GLP-1 receptor agonists is that they have an additional mechanism that relates to anti-inflammatory effects, especially for alleviating cell stress,” said Dr. Tittgemeyer. “Many ongoing clinical trials are assessing their effects in neuropsychiatric diseases,” he noted.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Tittgemyer and most of his coauthors had no disclosures. One coauthor had several disclosures, which are detailed in the report. Dr. Kroemer had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A single injection of the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide led to short-term normalization of associative learning in people with obesity and insulin resistance, a finding that suggests say the authors of a recent report in Nature Metabolism.

“We demonstrated that dopamine-driven associative learning about external sensory cues crucially depends on metabolic signaling,” said Marc Tittgemeyer, PhD, professor at the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research in Cologne, Germany, and senior author of the study. Study participants with impaired insulin sensitivity “exhibited a reduced amplitude of behavioral updating that was normalized” by a single subcutaneous injection of 0.6 mg of liraglutide (the starting daily dose for liraglutide for weight loss, available as Saxenda, Novo Nordisk) given the evening before testing.

The findings, from 30 adults with normal insulin sensitivity and normal weight and 24 adults with impaired insulin sensitivity and obesity, suggest that metabolic signals, particularly ones that promote energy restoration in a setting of energy deprivation caused by insulin or a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, “profoundly influence neuronal processing,” said Dr. Tittgemeyer. The findings suggest that impaired metabolic signaling such as occurs with insulin resistance in people with obesity can cause deficiencies in associative learning.

‘Liraglutide can normalize learning of associations’

“We show that in people with obesity, disrupted circuit mechanisms lead to impaired learning about sensory associations,” Dr. Tittgemeyer said in an interview. “The information provided by sensory systems that the brain must interpret to select a behavioral response are ‘off tune’ ” in these individuals.

“This is rather consequential for understanding food-intake behaviors. Modern obesity treatments, such as liraglutide, can normalize learning of associations and thereby render people susceptible again for sensory signals and make them more prone to react to subliminal interactions, such as weight-normalizing diets and conscious eating,” he added.

The normalization in associative learning that one dose of liraglutide produced in people with obesity “fits with studies showing that these drugs restore a normal feeling of satiety, causing people to eat less and therefore lose weight,” he explained.

Dr. Tittgemeyer noted that this effect is likely shared by other agents in the GLP-1 receptor agonist class, such as semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Novo Nordisk) but is likely not an effect when agents agonize receptors to other nutrient-stimulated hormones such as glucagon and the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide.

The findings “show that liraglutide restores associative learning in participants with greater insulin resistance,” a “highly relevant” discovery, commented Nils B. Kroemer, PhD, head of the section of medical psychology at the University of Bonn, Germany, who was not involved with this research, in a written statement.

The study run by Dr. Tittgemeyer and his associates included 54 healthy adult volunteers whom they assessed for insulin sensitivity with their homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. The researchers divided the cohort into groups; one group included 24 people with impaired insulin sensitivity, and one included 30 with normal insulin sensitivity. The average body mass index (BMI) of the normal sensitivity group was about 24 kg/m2; in the insulin-resistant subgroup, BMI averaged about 33 kg/m2.

The associative learning task tested the ability of participants to learn associations between auditory cues (a high or low tone) and a subsequent visual outcome (a picture of a face or a house). During each associative learning session, participants also underwent functional MRI of the brain.

Liraglutide treatment leveled learning

The results showed that the learning rate was significantly lower in the subgroup with impaired insulin sensitivity, compared with those with normal insulin sensitivity following treatment with a placebo injection. This indicates a decreased adaptation of learning to predictability variations in individuals with impaired insulin sensitivity.

In contrast, treatment with a single dose of liraglutide significantly enhanced the learning rate in the group with impaired insulin sensitivity but significantly reduced the learning rate in the group with normal insulin sensitivity. Liraglutide’s effect was twice as large in the group with impaired insulin sensitivity than in the group with normal insulin sensitivity, and these opposing effects of liraglutide resulted in a convergence of the two groups’ adaptive learning rates so that there wasn’t any significant between-group difference following liraglutide treatment.

After analyzing the functional MRI data along with the learning results, the researchers concluded that liraglutide normalized learning in individuals with impaired insulin sensitivity by enhancing adaptive prediction error encoding in the brain’s ventral striatum and mesocortical projection sites.

This apparent ability of GLP-1 analogues to correct this learning deficit in people with impaired insulin sensitivity and obesity has implications regarding potential benefit for people with other pathologies characterized by impaired dopaminergic function and associated with metabolic impairments, such as psychosis, Parkinson’s disease, and depression, the researchers say.

“The fascinating thing about GLP-1 receptor agonists is that they have an additional mechanism that relates to anti-inflammatory effects, especially for alleviating cell stress,” said Dr. Tittgemeyer. “Many ongoing clinical trials are assessing their effects in neuropsychiatric diseases,” he noted.