User login

Rash with weakness

The FP diagnosed dermatomyositis based on the patient’s proximal muscle weakness along with the typical shawl sign (erythema and scale over the shawl distribution) seen in the top image and the Gottron papules (erythematous and scaling papules over the dorsum of the fingers) and holster sign (erythema and scale over the lateral hip region) seen in the bottom image.

The FP started the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d and topical steroids for the affected areas. Laboratory exams showed an elevated creatinine kinase and mildly elevated antinuclear antibodies (typical for dermatomyositis). The FP also started the patient on oral prednisone 40 mg/d while putting in referrals for Dermatology and Rheumatology.

Two weeks later, the patient felt stronger and the rash had faded. Dermatology saw her first and started her on a steroid-sparing agent, methotrexate, with plans to taper her prednisone to lower doses over time. As underlying malignancy may precipitate dermatomyositis, the patient was screened for internal cancers—especially ovarian cancer. Fortunately, the mammogram, Pap smear, colonoscopy, and thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography scans all were normal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Buckley J, Burks M, Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1194-1203.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP diagnosed dermatomyositis based on the patient’s proximal muscle weakness along with the typical shawl sign (erythema and scale over the shawl distribution) seen in the top image and the Gottron papules (erythematous and scaling papules over the dorsum of the fingers) and holster sign (erythema and scale over the lateral hip region) seen in the bottom image.

The FP started the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d and topical steroids for the affected areas. Laboratory exams showed an elevated creatinine kinase and mildly elevated antinuclear antibodies (typical for dermatomyositis). The FP also started the patient on oral prednisone 40 mg/d while putting in referrals for Dermatology and Rheumatology.

Two weeks later, the patient felt stronger and the rash had faded. Dermatology saw her first and started her on a steroid-sparing agent, methotrexate, with plans to taper her prednisone to lower doses over time. As underlying malignancy may precipitate dermatomyositis, the patient was screened for internal cancers—especially ovarian cancer. Fortunately, the mammogram, Pap smear, colonoscopy, and thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography scans all were normal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Buckley J, Burks M, Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1194-1203.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP diagnosed dermatomyositis based on the patient’s proximal muscle weakness along with the typical shawl sign (erythema and scale over the shawl distribution) seen in the top image and the Gottron papules (erythematous and scaling papules over the dorsum of the fingers) and holster sign (erythema and scale over the lateral hip region) seen in the bottom image.

The FP started the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d and topical steroids for the affected areas. Laboratory exams showed an elevated creatinine kinase and mildly elevated antinuclear antibodies (typical for dermatomyositis). The FP also started the patient on oral prednisone 40 mg/d while putting in referrals for Dermatology and Rheumatology.

Two weeks later, the patient felt stronger and the rash had faded. Dermatology saw her first and started her on a steroid-sparing agent, methotrexate, with plans to taper her prednisone to lower doses over time. As underlying malignancy may precipitate dermatomyositis, the patient was screened for internal cancers—especially ovarian cancer. Fortunately, the mammogram, Pap smear, colonoscopy, and thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography scans all were normal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Buckley J, Burks M, Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1194-1203.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Scars and color changes on face

The FP recognized the scarring, skin atrophy, erythema and hyperpigmentation in the malar distribution as discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Upon examination, the FP noted similar patterns (with the addition of hypopigmentation) in the conchal bowls of both pinna. This was confirmatory for the DLE diagnosis (AKA chronic cutaneous lupus). (If in doubt, a 4-mm punch biopsy could be performed on the lesions of the face.) Without the lesions in the ears, sarcoidosis might have been considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis of DLE to the patient and ordered testing for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), a complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel. All the labs were normal, and the ANA was negative, which confirmed that this was not a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients with only DLE generally have negative or low-titer ANA titers.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine. The FP in this case started the patient on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid and topical triamcinolone 0.1% applied twice daily to the erythematous portions of the cheeks for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient’s skin looked less red and inflamed and she was happy with the improved appearance of her skin. Patients on hydroxychloroquine need a baseline eye exam by an ophthalmologist and then yearly exams after 5 years of therapy to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux, EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP recognized the scarring, skin atrophy, erythema and hyperpigmentation in the malar distribution as discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Upon examination, the FP noted similar patterns (with the addition of hypopigmentation) in the conchal bowls of both pinna. This was confirmatory for the DLE diagnosis (AKA chronic cutaneous lupus). (If in doubt, a 4-mm punch biopsy could be performed on the lesions of the face.) Without the lesions in the ears, sarcoidosis might have been considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis of DLE to the patient and ordered testing for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), a complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel. All the labs were normal, and the ANA was negative, which confirmed that this was not a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients with only DLE generally have negative or low-titer ANA titers.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine. The FP in this case started the patient on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid and topical triamcinolone 0.1% applied twice daily to the erythematous portions of the cheeks for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient’s skin looked less red and inflamed and she was happy with the improved appearance of her skin. Patients on hydroxychloroquine need a baseline eye exam by an ophthalmologist and then yearly exams after 5 years of therapy to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux, EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP recognized the scarring, skin atrophy, erythema and hyperpigmentation in the malar distribution as discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Upon examination, the FP noted similar patterns (with the addition of hypopigmentation) in the conchal bowls of both pinna. This was confirmatory for the DLE diagnosis (AKA chronic cutaneous lupus). (If in doubt, a 4-mm punch biopsy could be performed on the lesions of the face.) Without the lesions in the ears, sarcoidosis might have been considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis of DLE to the patient and ordered testing for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), a complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel. All the labs were normal, and the ANA was negative, which confirmed that this was not a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients with only DLE generally have negative or low-titer ANA titers.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine. The FP in this case started the patient on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid and topical triamcinolone 0.1% applied twice daily to the erythematous portions of the cheeks for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient’s skin looked less red and inflamed and she was happy with the improved appearance of her skin. Patients on hydroxychloroquine need a baseline eye exam by an ophthalmologist and then yearly exams after 5 years of therapy to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux, EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

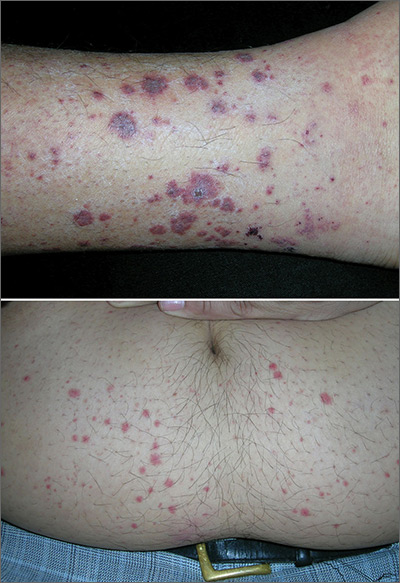

Marks on lower leg

The FP suspected that this was lichen aureus (a type of capillaritis that causes a pigmented purpuric dermatosis). Capillaritis is characterized by extravasation of erythrocytes in the skin with marked hemosiderin deposition. It is not palpable. Lichen aureus is a localized and often well circumscribed pigmented purpuric dermatosis that is seen in younger patients. It often occurs on the leg(s) but can be seen on other parts of the body.

Dermoscopy can help to visualize the red or pink dots with a brown background that represent inflamed capillaries with surrounding hemosiderin deposits.

In this case, the FP used his dermatoscope and could see pink dots with a brown background. He explained that this was sufficient to make the diagnosis of lichen aureus but gave the patient a choice to get a biopsy to confirm the clinical impression. The patient preferred to avoid the biopsy and accepted the diagnosis.

There is no proven beneficial therapy for lichen aureus or other types of capillaritis. Fortunately, it is benign and carries no associated health risks. The FP offered triamcinolone cream 0.1% to be applied once to twice daily, but did not promise that it would make the spots go away. The patient wanted to try something, so she accepted the prescription. No follow-up appointment was needed, but the FP did let the patient know that if the condition worsened, further evaluation, including a biopsy, could be performed in the future. The patient was seen a year later for a well woman exam and stated that the rash resolved about 6 months after she’d sought treatment for it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine, R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected that this was lichen aureus (a type of capillaritis that causes a pigmented purpuric dermatosis). Capillaritis is characterized by extravasation of erythrocytes in the skin with marked hemosiderin deposition. It is not palpable. Lichen aureus is a localized and often well circumscribed pigmented purpuric dermatosis that is seen in younger patients. It often occurs on the leg(s) but can be seen on other parts of the body.

Dermoscopy can help to visualize the red or pink dots with a brown background that represent inflamed capillaries with surrounding hemosiderin deposits.

In this case, the FP used his dermatoscope and could see pink dots with a brown background. He explained that this was sufficient to make the diagnosis of lichen aureus but gave the patient a choice to get a biopsy to confirm the clinical impression. The patient preferred to avoid the biopsy and accepted the diagnosis.

There is no proven beneficial therapy for lichen aureus or other types of capillaritis. Fortunately, it is benign and carries no associated health risks. The FP offered triamcinolone cream 0.1% to be applied once to twice daily, but did not promise that it would make the spots go away. The patient wanted to try something, so she accepted the prescription. No follow-up appointment was needed, but the FP did let the patient know that if the condition worsened, further evaluation, including a biopsy, could be performed in the future. The patient was seen a year later for a well woman exam and stated that the rash resolved about 6 months after she’d sought treatment for it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine, R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected that this was lichen aureus (a type of capillaritis that causes a pigmented purpuric dermatosis). Capillaritis is characterized by extravasation of erythrocytes in the skin with marked hemosiderin deposition. It is not palpable. Lichen aureus is a localized and often well circumscribed pigmented purpuric dermatosis that is seen in younger patients. It often occurs on the leg(s) but can be seen on other parts of the body.

Dermoscopy can help to visualize the red or pink dots with a brown background that represent inflamed capillaries with surrounding hemosiderin deposits.

In this case, the FP used his dermatoscope and could see pink dots with a brown background. He explained that this was sufficient to make the diagnosis of lichen aureus but gave the patient a choice to get a biopsy to confirm the clinical impression. The patient preferred to avoid the biopsy and accepted the diagnosis.

There is no proven beneficial therapy for lichen aureus or other types of capillaritis. Fortunately, it is benign and carries no associated health risks. The FP offered triamcinolone cream 0.1% to be applied once to twice daily, but did not promise that it would make the spots go away. The patient wanted to try something, so she accepted the prescription. No follow-up appointment was needed, but the FP did let the patient know that if the condition worsened, further evaluation, including a biopsy, could be performed in the future. The patient was seen a year later for a well woman exam and stated that the rash resolved about 6 months after she’d sought treatment for it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine, R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

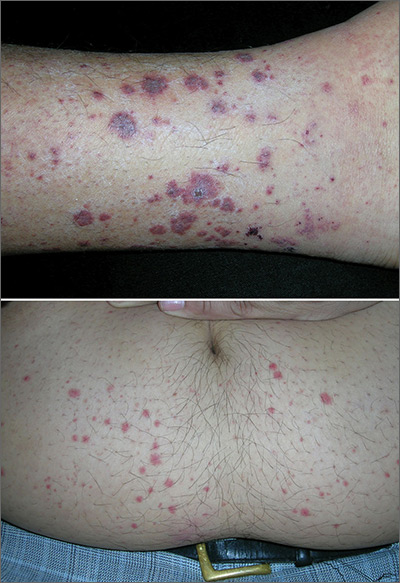

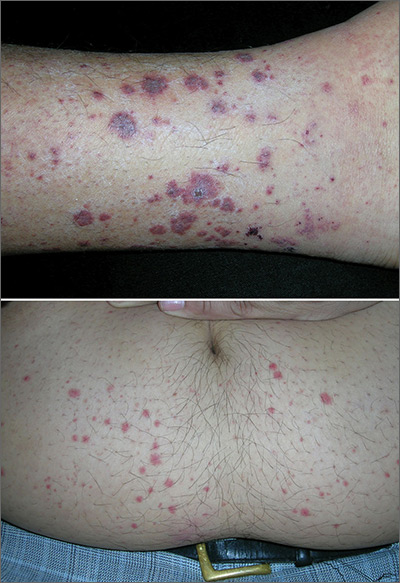

Rash on lower legs and abdomen

The FP suspected leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) and, with the patient’s consent, performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on a well-developed lesion on the abdomen. Biopsies on the abdomen heal faster than the legs and may provide a better specimen to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LCV. This is the most commonly seen form of small vessel vasculitis. LCV causes acute inflammation and necrosis of venules in the dermis. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes break apart into fragments. The purpura begins as asymptomatic localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that become palpable.

Discrete lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities, but they may occur on any dependent area. Small lesions may itch and be painful, but nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be more painful. Lesions appear in crops, last for 1 to 4 weeks, and may heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience a single episode caused by a drug reaction or viral infection or have multiple episodes associated with rheumatologic diseases. LCV usually is self-limited and confined to the skin.

To make the diagnosis, look for the presence of 3 or more of the following:

- age > 16 years;

- use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms;

- palpable purpura;

- maculopapular rash; and

- neutrophils around an arteriole or venule in a biopsy of a skin lesion.

In this case, the use of ibuprofen was the most likely precipitating event. Blood and urine tests did not show any renal or other organ system involvement. The patient was warned to not use ibuprofen in the future and that acetaminophen is a safer option for him. He was given topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% to apply twice daily for symptomatic relief. In this case, oral prednisone was not prescribed because the numerous potential adverse effects of prednisone outweighed the benefits. The vasculitis resolved in 4 weeks without any sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) and, with the patient’s consent, performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on a well-developed lesion on the abdomen. Biopsies on the abdomen heal faster than the legs and may provide a better specimen to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LCV. This is the most commonly seen form of small vessel vasculitis. LCV causes acute inflammation and necrosis of venules in the dermis. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes break apart into fragments. The purpura begins as asymptomatic localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that become palpable.

Discrete lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities, but they may occur on any dependent area. Small lesions may itch and be painful, but nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be more painful. Lesions appear in crops, last for 1 to 4 weeks, and may heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience a single episode caused by a drug reaction or viral infection or have multiple episodes associated with rheumatologic diseases. LCV usually is self-limited and confined to the skin.

To make the diagnosis, look for the presence of 3 or more of the following:

- age > 16 years;

- use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms;

- palpable purpura;

- maculopapular rash; and

- neutrophils around an arteriole or venule in a biopsy of a skin lesion.

In this case, the use of ibuprofen was the most likely precipitating event. Blood and urine tests did not show any renal or other organ system involvement. The patient was warned to not use ibuprofen in the future and that acetaminophen is a safer option for him. He was given topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% to apply twice daily for symptomatic relief. In this case, oral prednisone was not prescribed because the numerous potential adverse effects of prednisone outweighed the benefits. The vasculitis resolved in 4 weeks without any sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) and, with the patient’s consent, performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on a well-developed lesion on the abdomen. Biopsies on the abdomen heal faster than the legs and may provide a better specimen to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LCV. This is the most commonly seen form of small vessel vasculitis. LCV causes acute inflammation and necrosis of venules in the dermis. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes break apart into fragments. The purpura begins as asymptomatic localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that become palpable.

Discrete lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities, but they may occur on any dependent area. Small lesions may itch and be painful, but nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be more painful. Lesions appear in crops, last for 1 to 4 weeks, and may heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience a single episode caused by a drug reaction or viral infection or have multiple episodes associated with rheumatologic diseases. LCV usually is self-limited and confined to the skin.

To make the diagnosis, look for the presence of 3 or more of the following:

- age > 16 years;

- use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms;

- palpable purpura;

- maculopapular rash; and

- neutrophils around an arteriole or venule in a biopsy of a skin lesion.

In this case, the use of ibuprofen was the most likely precipitating event. Blood and urine tests did not show any renal or other organ system involvement. The patient was warned to not use ibuprofen in the future and that acetaminophen is a safer option for him. He was given topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% to apply twice daily for symptomatic relief. In this case, oral prednisone was not prescribed because the numerous potential adverse effects of prednisone outweighed the benefits. The vasculitis resolved in 4 weeks without any sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Left ear pain

The FP suspected cutaneous vasculitis of the ear caused by levamisole-adulterated cocaine.

Levamisole is an antihelminthic drug approved for veterinary purposes. In the past, the drug had been used as an immune modulator in autoimmune disorders, but no longer is considered safe for human use, as it can cause agranulocytosis. Sellers around the world often lace cocaine with levamisole because it boosts the profits and potentiates the psychoactive effects of the cocaine. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been reported many times in the literature.

Levamisole-associated vasculitis presents with ear purpura, retiform (like a net) purpura of the trunk or extremities, and neutropenia. Patients will test positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA). This cutaneous vasculitis also may present on the nose or face. There are reports of cocaine/levamisole-associated autoimmune syndrome involving agranulocytosis and cutaneous vasculitis.

The patient tested positive for pANCA, as was expected. The FP told her to discontinue her cocaine use, as she ran the risk of worse manifestations. She refused any treatment for her drug use and stated she could stop it on her own. The FP referred the patient to Dermatology, but the vasculitis was barely visible by the time she was seen. Convincing the patient not to use cocaine again remained the only treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jon Karnes, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected cutaneous vasculitis of the ear caused by levamisole-adulterated cocaine.

Levamisole is an antihelminthic drug approved for veterinary purposes. In the past, the drug had been used as an immune modulator in autoimmune disorders, but no longer is considered safe for human use, as it can cause agranulocytosis. Sellers around the world often lace cocaine with levamisole because it boosts the profits and potentiates the psychoactive effects of the cocaine. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been reported many times in the literature.

Levamisole-associated vasculitis presents with ear purpura, retiform (like a net) purpura of the trunk or extremities, and neutropenia. Patients will test positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA). This cutaneous vasculitis also may present on the nose or face. There are reports of cocaine/levamisole-associated autoimmune syndrome involving agranulocytosis and cutaneous vasculitis.

The patient tested positive for pANCA, as was expected. The FP told her to discontinue her cocaine use, as she ran the risk of worse manifestations. She refused any treatment for her drug use and stated she could stop it on her own. The FP referred the patient to Dermatology, but the vasculitis was barely visible by the time she was seen. Convincing the patient not to use cocaine again remained the only treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jon Karnes, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected cutaneous vasculitis of the ear caused by levamisole-adulterated cocaine.

Levamisole is an antihelminthic drug approved for veterinary purposes. In the past, the drug had been used as an immune modulator in autoimmune disorders, but no longer is considered safe for human use, as it can cause agranulocytosis. Sellers around the world often lace cocaine with levamisole because it boosts the profits and potentiates the psychoactive effects of the cocaine. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been reported many times in the literature.

Levamisole-associated vasculitis presents with ear purpura, retiform (like a net) purpura of the trunk or extremities, and neutropenia. Patients will test positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA). This cutaneous vasculitis also may present on the nose or face. There are reports of cocaine/levamisole-associated autoimmune syndrome involving agranulocytosis and cutaneous vasculitis.

The patient tested positive for pANCA, as was expected. The FP told her to discontinue her cocaine use, as she ran the risk of worse manifestations. She refused any treatment for her drug use and stated she could stop it on her own. The FP referred the patient to Dermatology, but the vasculitis was barely visible by the time she was seen. Convincing the patient not to use cocaine again remained the only treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jon Karnes, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Rash on the thigh

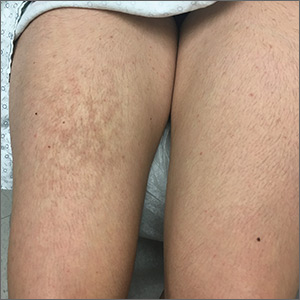

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected]

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected]

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected]

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

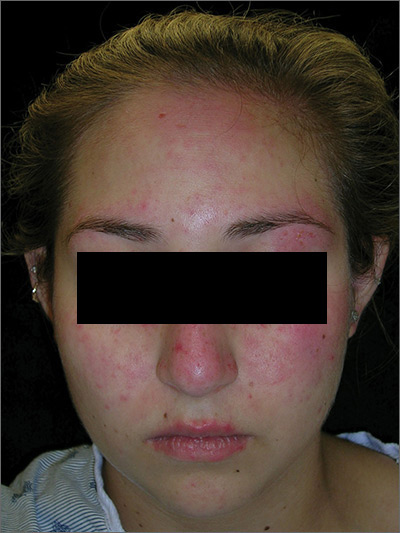

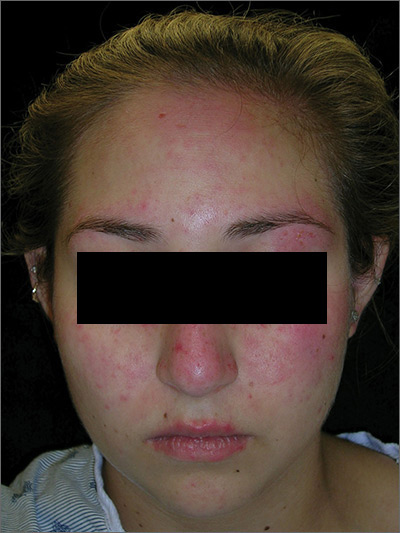

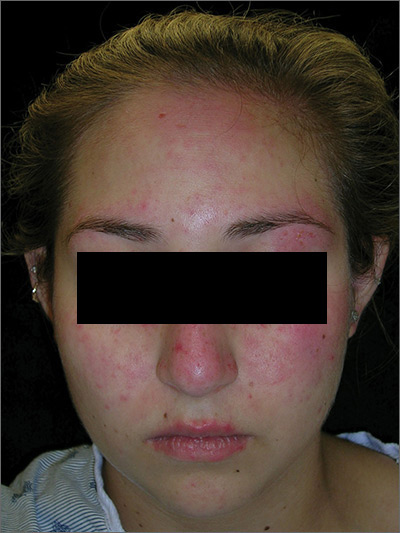

Rash on face, chest, upper arms, and thighs

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Tender nodules after leprosy Tx

The treating physicians believed that the patient had developed erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), based on the tender nodules that are characteristic of this treatment reaction. The CDC was again consulted and representatives there agreed.

ENL is a known as a Type 2 reaction to the treatment for leprosy. Management involves the use of oral prednisone, which may be needed for a prolonged time. The antibiotics used to treat leprosy should not be stopped, as ENL is not an allergic reaction. It is due to the destruction of bacilli and the immune response to the release of bacterial antigens.

The patient was transferred to a leprosy hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for further management. The prednisone was not sufficient, and he required further treatment with thalidomide. After 2 years of treatment, he appeared to be free of leprosy and no longer had the ENL.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the third edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The treating physicians believed that the patient had developed erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), based on the tender nodules that are characteristic of this treatment reaction. The CDC was again consulted and representatives there agreed.

ENL is a known as a Type 2 reaction to the treatment for leprosy. Management involves the use of oral prednisone, which may be needed for a prolonged time. The antibiotics used to treat leprosy should not be stopped, as ENL is not an allergic reaction. It is due to the destruction of bacilli and the immune response to the release of bacterial antigens.

The patient was transferred to a leprosy hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for further management. The prednisone was not sufficient, and he required further treatment with thalidomide. After 2 years of treatment, he appeared to be free of leprosy and no longer had the ENL.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the third edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The treating physicians believed that the patient had developed erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), based on the tender nodules that are characteristic of this treatment reaction. The CDC was again consulted and representatives there agreed.

ENL is a known as a Type 2 reaction to the treatment for leprosy. Management involves the use of oral prednisone, which may be needed for a prolonged time. The antibiotics used to treat leprosy should not be stopped, as ENL is not an allergic reaction. It is due to the destruction of bacilli and the immune response to the release of bacterial antigens.

The patient was transferred to a leprosy hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for further management. The prednisone was not sufficient, and he required further treatment with thalidomide. After 2 years of treatment, he appeared to be free of leprosy and no longer had the ENL.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the third edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

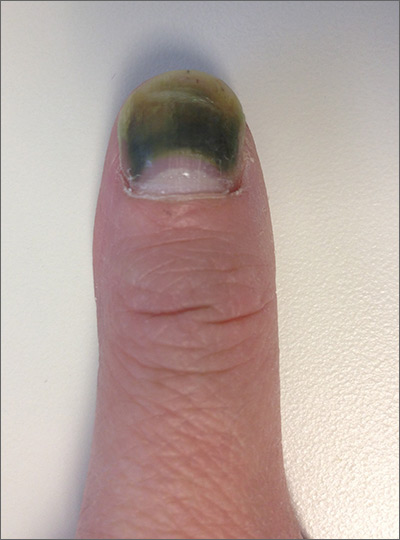

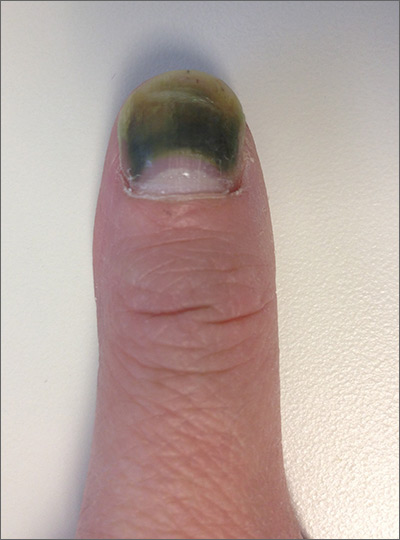

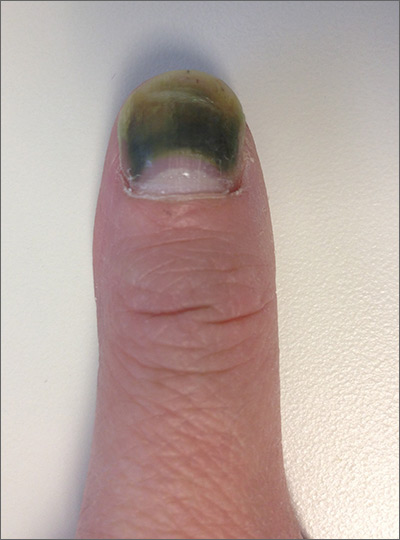

Green thumbnail

The patient was given a diagnosis of green nail syndrome (GNS), an infection of the nail bed caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These bacteria produce pyocyanin, a blue-green pigment that discolors the nail. GNS often occurs in patients with prior nail problems, such as onychomycosis, onycholysis, trauma, chronic paronychia, or psoriasis.

Nail disease disrupts the integumentary barrier and allows a portal of entry for bacteria. Scanning electron microscopy of patients with GNS has shown that fungal infections create tunnel-like structures in the nail keratin, and P aeruginosa can grow in these spaces. Nails with prior nail disease that are chronically exposed to moisture are at greatest risk of developing GNS, and it is typical for only one nail to be involved.

It’s likely that this patient’s earlier nail problem had been a case of onycholysis, based on her description of a “spongy” nail bed and loose nail. This created a favorable environment for an infection by allowing moisture and bacteria to infiltrate the space. The patient also acknowledged that she washed dishes by hand and bathed her young children. This frequent soaking of her hands likely helped to provide a moist environment in which P aeruginosa could thrive. In addition, onycholysis is associated with hypothyroidism, which the patient also had.

GNS can be diagnosed by clinical observation and characteristic pigmentation along with an appropriate patient history. Nail discoloration, or chromonychia, can present in a variety of colors. Nail findings may represent an isolated disease or provide an important clinical clue to other systemic diseases. The specific shade of discoloration helps to differentiate the underlying pathology. Culture of the nail bed may be helpful if bacterial resistance or co-infection with fungal organisms is suspected. GNS is often painless, but may be accompanied by mild tenderness of the nail.

The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 10 days, plus bleach soaks (1 part bleach to 4 parts water) twice a day. She also was advised to wear gloves for household tasks that involved immersing her hands in water, and to dry her finger with a hair dryer after bathing.

This case was adapted from: Gish D, Romero BJ. Green fingernail. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:E7-E9.

The patient was given a diagnosis of green nail syndrome (GNS), an infection of the nail bed caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These bacteria produce pyocyanin, a blue-green pigment that discolors the nail. GNS often occurs in patients with prior nail problems, such as onychomycosis, onycholysis, trauma, chronic paronychia, or psoriasis.

Nail disease disrupts the integumentary barrier and allows a portal of entry for bacteria. Scanning electron microscopy of patients with GNS has shown that fungal infections create tunnel-like structures in the nail keratin, and P aeruginosa can grow in these spaces. Nails with prior nail disease that are chronically exposed to moisture are at greatest risk of developing GNS, and it is typical for only one nail to be involved.

It’s likely that this patient’s earlier nail problem had been a case of onycholysis, based on her description of a “spongy” nail bed and loose nail. This created a favorable environment for an infection by allowing moisture and bacteria to infiltrate the space. The patient also acknowledged that she washed dishes by hand and bathed her young children. This frequent soaking of her hands likely helped to provide a moist environment in which P aeruginosa could thrive. In addition, onycholysis is associated with hypothyroidism, which the patient also had.

GNS can be diagnosed by clinical observation and characteristic pigmentation along with an appropriate patient history. Nail discoloration, or chromonychia, can present in a variety of colors. Nail findings may represent an isolated disease or provide an important clinical clue to other systemic diseases. The specific shade of discoloration helps to differentiate the underlying pathology. Culture of the nail bed may be helpful if bacterial resistance or co-infection with fungal organisms is suspected. GNS is often painless, but may be accompanied by mild tenderness of the nail.

The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 10 days, plus bleach soaks (1 part bleach to 4 parts water) twice a day. She also was advised to wear gloves for household tasks that involved immersing her hands in water, and to dry her finger with a hair dryer after bathing.

This case was adapted from: Gish D, Romero BJ. Green fingernail. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:E7-E9.

The patient was given a diagnosis of green nail syndrome (GNS), an infection of the nail bed caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These bacteria produce pyocyanin, a blue-green pigment that discolors the nail. GNS often occurs in patients with prior nail problems, such as onychomycosis, onycholysis, trauma, chronic paronychia, or psoriasis.

Nail disease disrupts the integumentary barrier and allows a portal of entry for bacteria. Scanning electron microscopy of patients with GNS has shown that fungal infections create tunnel-like structures in the nail keratin, and P aeruginosa can grow in these spaces. Nails with prior nail disease that are chronically exposed to moisture are at greatest risk of developing GNS, and it is typical for only one nail to be involved.

It’s likely that this patient’s earlier nail problem had been a case of onycholysis, based on her description of a “spongy” nail bed and loose nail. This created a favorable environment for an infection by allowing moisture and bacteria to infiltrate the space. The patient also acknowledged that she washed dishes by hand and bathed her young children. This frequent soaking of her hands likely helped to provide a moist environment in which P aeruginosa could thrive. In addition, onycholysis is associated with hypothyroidism, which the patient also had.

GNS can be diagnosed by clinical observation and characteristic pigmentation along with an appropriate patient history. Nail discoloration, or chromonychia, can present in a variety of colors. Nail findings may represent an isolated disease or provide an important clinical clue to other systemic diseases. The specific shade of discoloration helps to differentiate the underlying pathology. Culture of the nail bed may be helpful if bacterial resistance or co-infection with fungal organisms is suspected. GNS is often painless, but may be accompanied by mild tenderness of the nail.

The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 10 days, plus bleach soaks (1 part bleach to 4 parts water) twice a day. She also was advised to wear gloves for household tasks that involved immersing her hands in water, and to dry her finger with a hair dryer after bathing.

This case was adapted from: Gish D, Romero BJ. Green fingernail. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:E7-E9.