User login

Tender swellings on legs

Based on the physical exam findings, the FP diagnosed erythema nodosum (EN) in this patient. He considered doing a punch biopsy down to the fat to prove that this was a panniculus, but realized that this was a classic presentation of EN. The lesions of EN are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. These lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful.

The FP sought to consider the cause, and questioned the patient further about medications and other symptoms; however, he was unable to uncover any likely “suspects.” He then drew labs for a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid and QuantiFERON TB gold tests. He started the patient on ibuprofen 400 mg tid with meals for the pain and inflammation.

On a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, all of the lab results were normal and the patient was about 50% improved. At this time, the FP obtained a chest x-ray to look for any evidence of sarcoidosis. The x-ray was also normal. (About half of all cases of EN are idiopathic, so the normal results were not surprising.) By the third visit the patient was 90% better and was happy to keep taking the ibuprofen to see if this would resolve completely.

After 6 weeks of treatment, there were no more tender erythematous nodules. All that remained was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient was happy with these results and understood that she should return if the EN came back.

Photo courtesy of Hanuš Rozsypal, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the physical exam findings, the FP diagnosed erythema nodosum (EN) in this patient. He considered doing a punch biopsy down to the fat to prove that this was a panniculus, but realized that this was a classic presentation of EN. The lesions of EN are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. These lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful.

The FP sought to consider the cause, and questioned the patient further about medications and other symptoms; however, he was unable to uncover any likely “suspects.” He then drew labs for a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid and QuantiFERON TB gold tests. He started the patient on ibuprofen 400 mg tid with meals for the pain and inflammation.

On a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, all of the lab results were normal and the patient was about 50% improved. At this time, the FP obtained a chest x-ray to look for any evidence of sarcoidosis. The x-ray was also normal. (About half of all cases of EN are idiopathic, so the normal results were not surprising.) By the third visit the patient was 90% better and was happy to keep taking the ibuprofen to see if this would resolve completely.

After 6 weeks of treatment, there were no more tender erythematous nodules. All that remained was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient was happy with these results and understood that she should return if the EN came back.

Photo courtesy of Hanuš Rozsypal, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the physical exam findings, the FP diagnosed erythema nodosum (EN) in this patient. He considered doing a punch biopsy down to the fat to prove that this was a panniculus, but realized that this was a classic presentation of EN. The lesions of EN are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. These lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful.

The FP sought to consider the cause, and questioned the patient further about medications and other symptoms; however, he was unable to uncover any likely “suspects.” He then drew labs for a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid and QuantiFERON TB gold tests. He started the patient on ibuprofen 400 mg tid with meals for the pain and inflammation.

On a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, all of the lab results were normal and the patient was about 50% improved. At this time, the FP obtained a chest x-ray to look for any evidence of sarcoidosis. The x-ray was also normal. (About half of all cases of EN are idiopathic, so the normal results were not surprising.) By the third visit the patient was 90% better and was happy to keep taking the ibuprofen to see if this would resolve completely.

After 6 weeks of treatment, there were no more tender erythematous nodules. All that remained was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient was happy with these results and understood that she should return if the EN came back.

Photo courtesy of Hanuš Rozsypal, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Peeling skin with chills

The physician thought that this was most likely toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). He was in a small hospital without a burn unit, so he drew baseline labs and blood cultures, and started to give intravenous fluids to treat the dehydration.

TEN is on the most severe side of a spectrum of disorders that includes erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). Erythema multiforme is diagnosed when < 10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when between 10% and 30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. Drugs that are most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN include sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. In this case, the amoxicillin was the likely culprit.

The physician waited until the patient was hemodynamically stable before transferring her to the closest city hospital where a dermatologist could manage her care. The dermatologist agreed with the diagnosis of TEN and continued supportive care. While the hospital did not have intravenous immunoglobulin or cyclosporine on hand, the health care team was able to provide the necessary supportive care. The patient survived, and she was warned to never take any type of penicillin again.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The physician thought that this was most likely toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). He was in a small hospital without a burn unit, so he drew baseline labs and blood cultures, and started to give intravenous fluids to treat the dehydration.

TEN is on the most severe side of a spectrum of disorders that includes erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). Erythema multiforme is diagnosed when < 10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when between 10% and 30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. Drugs that are most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN include sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. In this case, the amoxicillin was the likely culprit.

The physician waited until the patient was hemodynamically stable before transferring her to the closest city hospital where a dermatologist could manage her care. The dermatologist agreed with the diagnosis of TEN and continued supportive care. While the hospital did not have intravenous immunoglobulin or cyclosporine on hand, the health care team was able to provide the necessary supportive care. The patient survived, and she was warned to never take any type of penicillin again.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The physician thought that this was most likely toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). He was in a small hospital without a burn unit, so he drew baseline labs and blood cultures, and started to give intravenous fluids to treat the dehydration.

TEN is on the most severe side of a spectrum of disorders that includes erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). Erythema multiforme is diagnosed when < 10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when between 10% and 30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. Drugs that are most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN include sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. In this case, the amoxicillin was the likely culprit.

The physician waited until the patient was hemodynamically stable before transferring her to the closest city hospital where a dermatologist could manage her care. The dermatologist agreed with the diagnosis of TEN and continued supportive care. While the hospital did not have intravenous immunoglobulin or cyclosporine on hand, the health care team was able to provide the necessary supportive care. The patient survived, and she was warned to never take any type of penicillin again.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash on both palms

The FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption on his palms. In this case, the EM was due to the herpes simplex outbreak on the patient’s lips (herpes labialis) that had occurred about a week earlier.

EM is a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in ≥ 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that cold sores were due to herpes simplex and most oral HSV is due to HSV1 infection. He acknowledged that he experienced cold sores about every 2 months that were usually related to stress or exposure to intense sunlight. The FP recommended that the patient avoid intense sunlight (midday sun avoidance; wearing sunscreen and hats) and use lip protection with at least an SPF of 15. As the lip lesions were > 90% healed, there was no reason for the FP to prescribe an antiviral agent. The FP did, however, offer a prescription for valacyclovir to be used at the first signs of an oral herpes outbreak to avoid another case of EM (2000 mg by mouth every 12 hours x 2 doses). For symptomatic relief of the EM, the physician prescribed a 15 g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied to the lesions twice daily.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption on his palms. In this case, the EM was due to the herpes simplex outbreak on the patient’s lips (herpes labialis) that had occurred about a week earlier.

EM is a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in ≥ 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that cold sores were due to herpes simplex and most oral HSV is due to HSV1 infection. He acknowledged that he experienced cold sores about every 2 months that were usually related to stress or exposure to intense sunlight. The FP recommended that the patient avoid intense sunlight (midday sun avoidance; wearing sunscreen and hats) and use lip protection with at least an SPF of 15. As the lip lesions were > 90% healed, there was no reason for the FP to prescribe an antiviral agent. The FP did, however, offer a prescription for valacyclovir to be used at the first signs of an oral herpes outbreak to avoid another case of EM (2000 mg by mouth every 12 hours x 2 doses). For symptomatic relief of the EM, the physician prescribed a 15 g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied to the lesions twice daily.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption on his palms. In this case, the EM was due to the herpes simplex outbreak on the patient’s lips (herpes labialis) that had occurred about a week earlier.

EM is a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in ≥ 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that cold sores were due to herpes simplex and most oral HSV is due to HSV1 infection. He acknowledged that he experienced cold sores about every 2 months that were usually related to stress or exposure to intense sunlight. The FP recommended that the patient avoid intense sunlight (midday sun avoidance; wearing sunscreen and hats) and use lip protection with at least an SPF of 15. As the lip lesions were > 90% healed, there was no reason for the FP to prescribe an antiviral agent. The FP did, however, offer a prescription for valacyclovir to be used at the first signs of an oral herpes outbreak to avoid another case of EM (2000 mg by mouth every 12 hours x 2 doses). For symptomatic relief of the EM, the physician prescribed a 15 g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied to the lesions twice daily.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Facial swelling in an adolescent

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

Multiple hyperpigmented papules and plaques

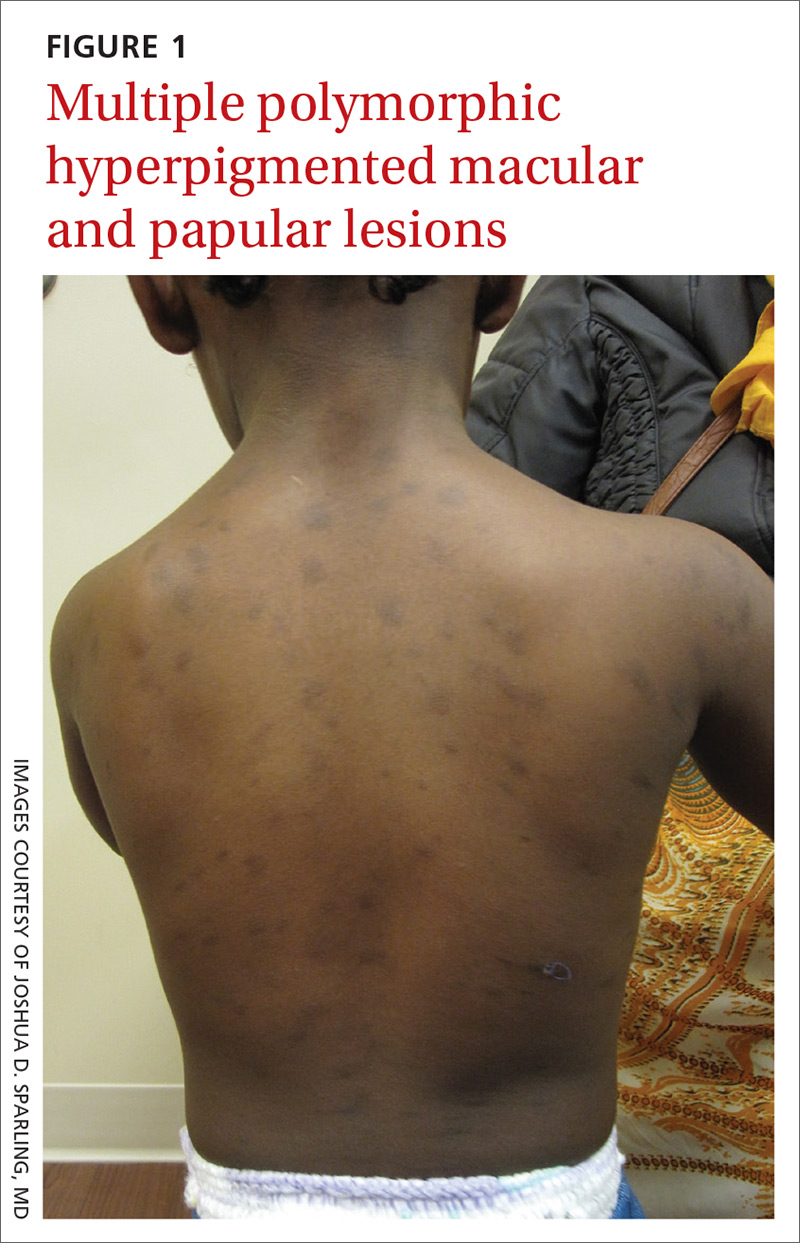

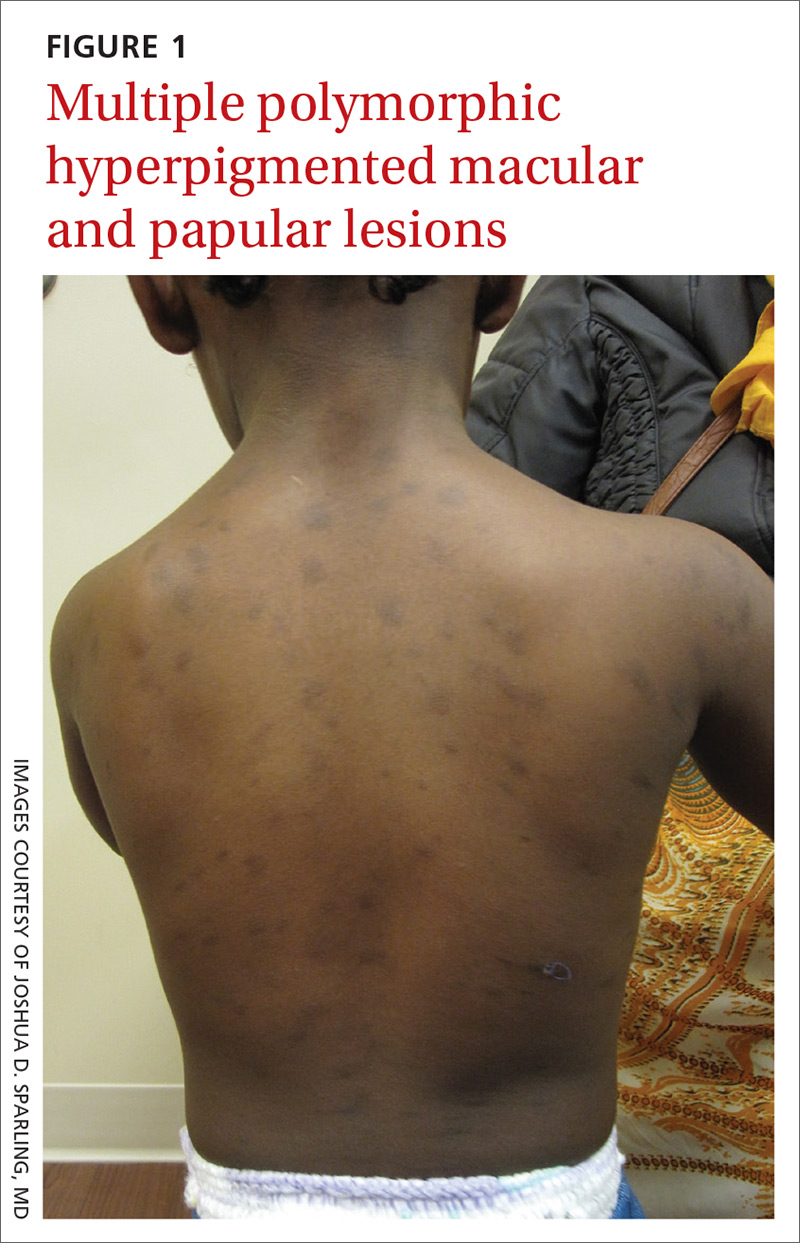

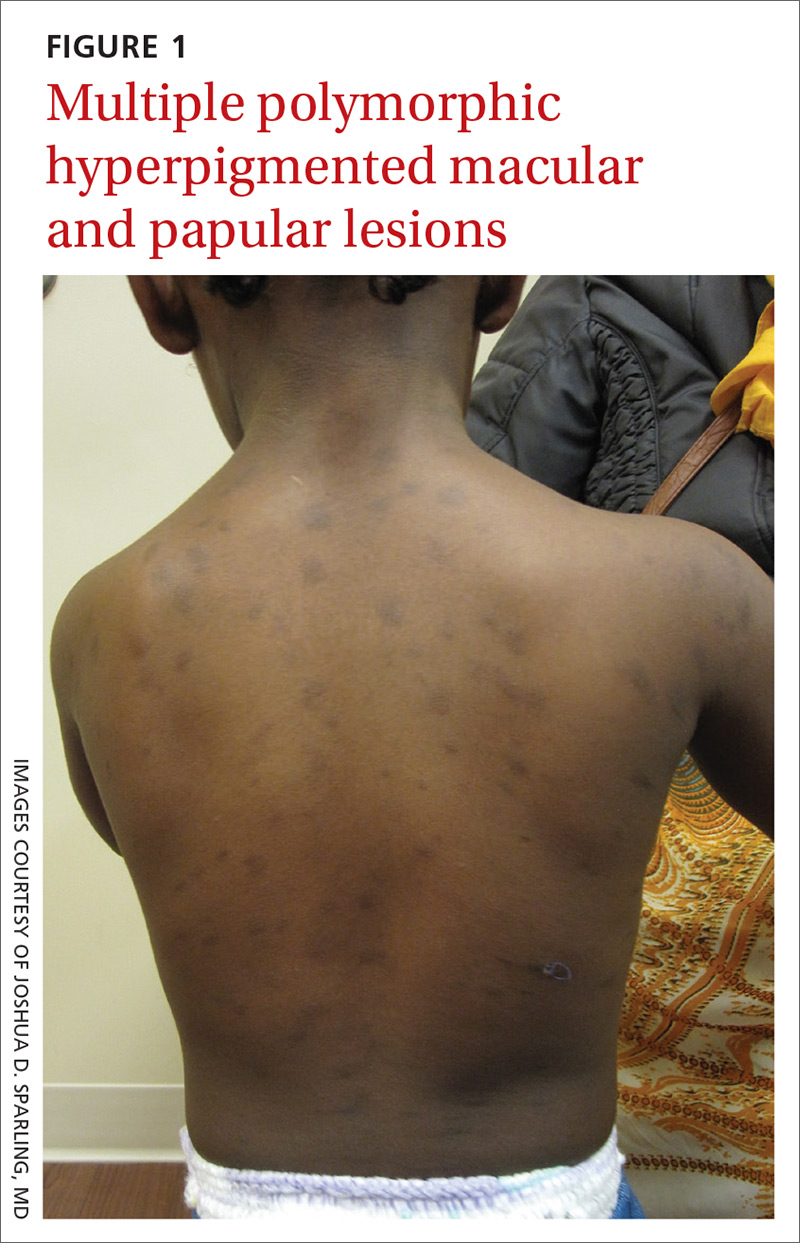

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

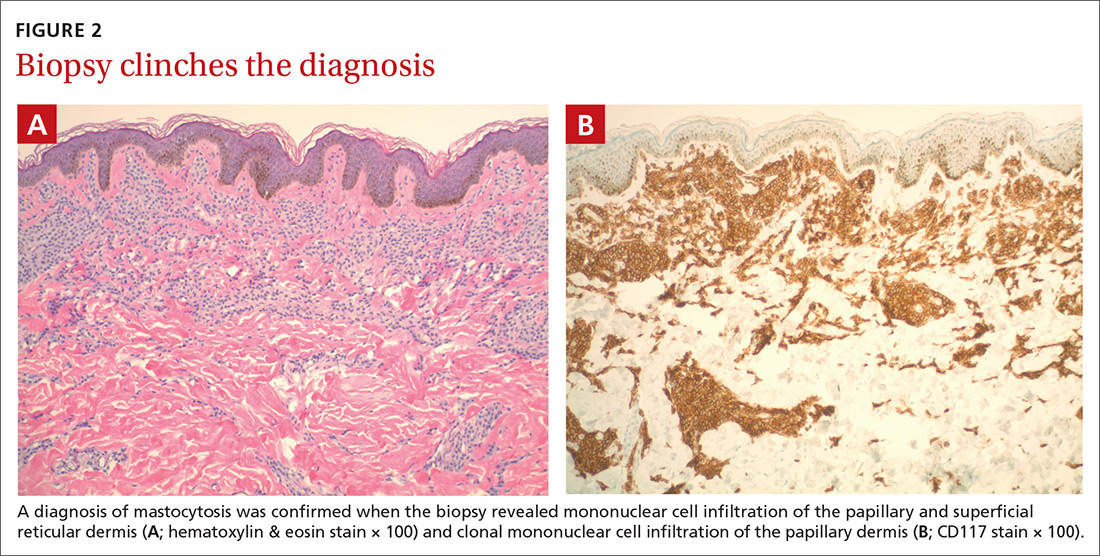

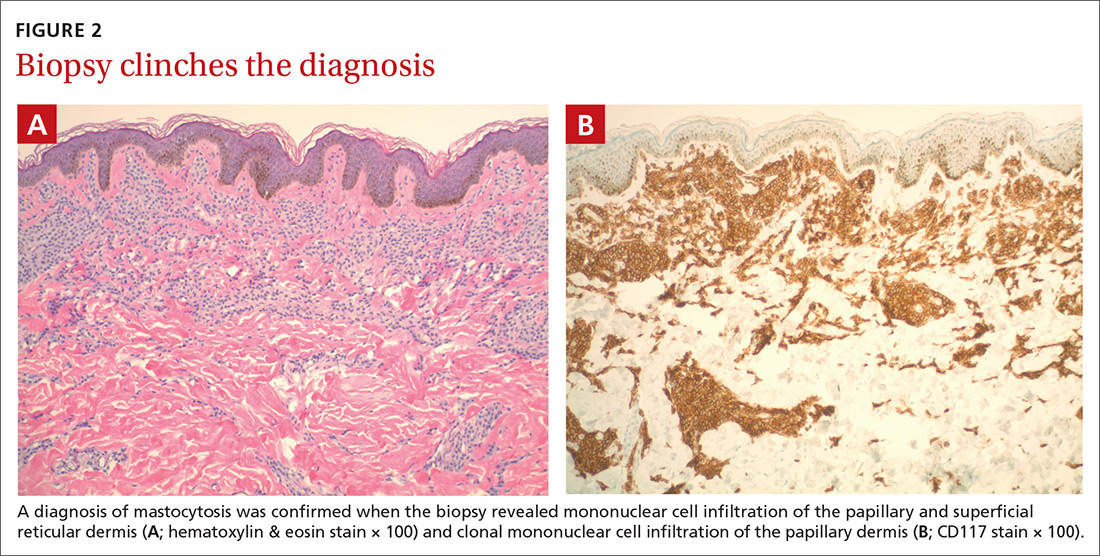

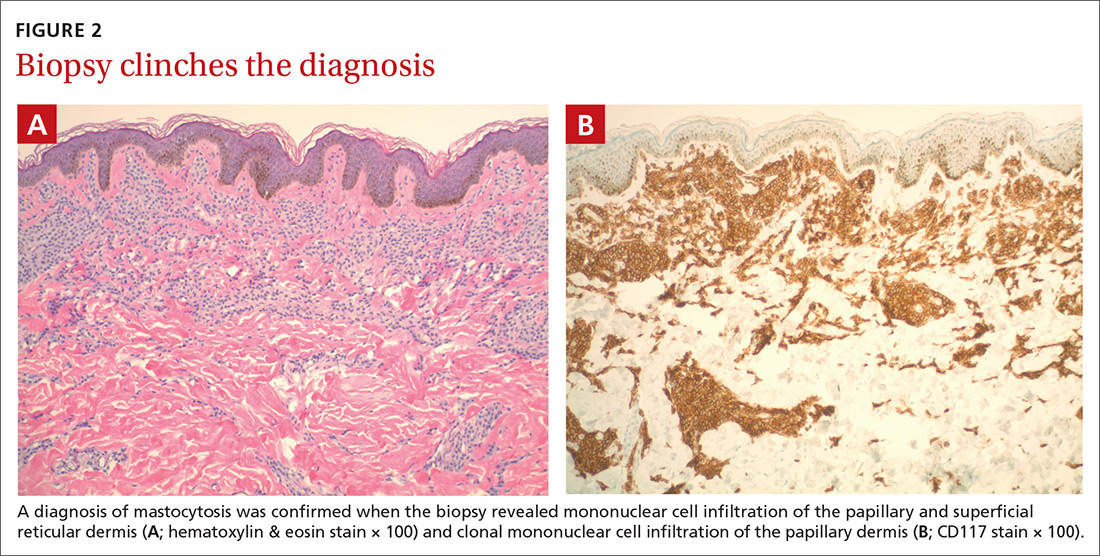

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

Rash with fever and shortness of breath

The skin biopsy confirmed toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), possibly secondary to one of the antibiotics he’d been given upon hospital admission. The health care team suspected that the patient had Stevens-Johns Syndrome when he sought care and that it had evolved into TEN. Both diseases are life-threatening and require intensive in-hospital care.

TEN is part of a spectrum of disorders that includes erythema multiforme (< 10% of the body surface is involved); SJS/TEN (10%-30% involvement with erythematous or pruritic macules, widespread blisters on the trunk and face, and erosions of ≥ 1 mucous membranes); and TEN (> 30% involvement).

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN include sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Fifty percent of SJS/TEN cases have no identifiable cause. Not all SJS is secondary to drug exposure, but it is the job of the clinician to investigate this cause and stop any suspicious medications.

In this case, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was discontinued immediately and the patient was transferred to a burn unit and given intravenous gamma-globulin 1 g/kg for 3 days. Fortunately, the patient survived with intensive supportive care in the burn unit. The exfoliation of > 30% of the skin is like a large secondary burn, and a burn unit is the optimal location for lifesaving measures.

Photo courtesy of Robert T. Gilson, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The skin biopsy confirmed toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), possibly secondary to one of the antibiotics he’d been given upon hospital admission. The health care team suspected that the patient had Stevens-Johns Syndrome when he sought care and that it had evolved into TEN. Both diseases are life-threatening and require intensive in-hospital care.

TEN is part of a spectrum of disorders that includes erythema multiforme (< 10% of the body surface is involved); SJS/TEN (10%-30% involvement with erythematous or pruritic macules, widespread blisters on the trunk and face, and erosions of ≥ 1 mucous membranes); and TEN (> 30% involvement).

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN include sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Fifty percent of SJS/TEN cases have no identifiable cause. Not all SJS is secondary to drug exposure, but it is the job of the clinician to investigate this cause and stop any suspicious medications.

In this case, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was discontinued immediately and the patient was transferred to a burn unit and given intravenous gamma-globulin 1 g/kg for 3 days. Fortunately, the patient survived with intensive supportive care in the burn unit. The exfoliation of > 30% of the skin is like a large secondary burn, and a burn unit is the optimal location for lifesaving measures.

Photo courtesy of Robert T. Gilson, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The skin biopsy confirmed toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), possibly secondary to one of the antibiotics he’d been given upon hospital admission. The health care team suspected that the patient had Stevens-Johns Syndrome when he sought care and that it had evolved into TEN. Both diseases are life-threatening and require intensive in-hospital care.

TEN is part of a spectrum of disorders that includes erythema multiforme (< 10% of the body surface is involved); SJS/TEN (10%-30% involvement with erythematous or pruritic macules, widespread blisters on the trunk and face, and erosions of ≥ 1 mucous membranes); and TEN (> 30% involvement).

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN include sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Fifty percent of SJS/TEN cases have no identifiable cause. Not all SJS is secondary to drug exposure, but it is the job of the clinician to investigate this cause and stop any suspicious medications.

In this case, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was discontinued immediately and the patient was transferred to a burn unit and given intravenous gamma-globulin 1 g/kg for 3 days. Fortunately, the patient survived with intensive supportive care in the burn unit. The exfoliation of > 30% of the skin is like a large secondary burn, and a burn unit is the optimal location for lifesaving measures.

Photo courtesy of Robert T. Gilson, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash on elbows and hands

Based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption, the FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient. He also diagnosed genital herpes simplex in the crusting stage and suspected that it was the inciting event for the EM.

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that she had genital herpes simplex but remembered having sores in the genital area that preceded the similar rash a year earlier. This was a case of recurrent EM responding to recurrent herpes simplex.

The patient suspected that she had genital herpes simplex on and off for the past 10 years but lacked health insurance, so she never visited a doctor for treatment. She recently obtained health insurance and was willing to be tested for other sexually transmitted diseases. She also wanted to have a test done to confirm this was herpes simplex. The FP explained that it was unlikely that an antiviral agent would help the current case of herpes simplex and the associated EM because of the late timing, but antiviral medication could help to prevent further outbreaks and decrease transmission to her husband.

The patient was enthusiastic to start valacyclovir 500 mg/d for prophylaxis. For symptomatic relief, the FP prescribed a 30-g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone appointment and instructed the patient to apply it to the EM twice daily. The patient was sent for blood tests for syphilis and HIV; fortunately, both came back negative. The herpes simplex PCR test was positive for HSV2.

On a 1-week follow-up visit, the skin lesions were resolving, and the patient had no further symptoms. The patient said she understood that she should refrain from sexual intercourse if she developed lesions while on prophylaxis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption, the FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient. He also diagnosed genital herpes simplex in the crusting stage and suspected that it was the inciting event for the EM.

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that she had genital herpes simplex but remembered having sores in the genital area that preceded the similar rash a year earlier. This was a case of recurrent EM responding to recurrent herpes simplex.

The patient suspected that she had genital herpes simplex on and off for the past 10 years but lacked health insurance, so she never visited a doctor for treatment. She recently obtained health insurance and was willing to be tested for other sexually transmitted diseases. She also wanted to have a test done to confirm this was herpes simplex. The FP explained that it was unlikely that an antiviral agent would help the current case of herpes simplex and the associated EM because of the late timing, but antiviral medication could help to prevent further outbreaks and decrease transmission to her husband.

The patient was enthusiastic to start valacyclovir 500 mg/d for prophylaxis. For symptomatic relief, the FP prescribed a 30-g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone appointment and instructed the patient to apply it to the EM twice daily. The patient was sent for blood tests for syphilis and HIV; fortunately, both came back negative. The herpes simplex PCR test was positive for HSV2.

On a 1-week follow-up visit, the skin lesions were resolving, and the patient had no further symptoms. The patient said she understood that she should refrain from sexual intercourse if she developed lesions while on prophylaxis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption, the FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient. He also diagnosed genital herpes simplex in the crusting stage and suspected that it was the inciting event for the EM.

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that she had genital herpes simplex but remembered having sores in the genital area that preceded the similar rash a year earlier. This was a case of recurrent EM responding to recurrent herpes simplex.

The patient suspected that she had genital herpes simplex on and off for the past 10 years but lacked health insurance, so she never visited a doctor for treatment. She recently obtained health insurance and was willing to be tested for other sexually transmitted diseases. She also wanted to have a test done to confirm this was herpes simplex. The FP explained that it was unlikely that an antiviral agent would help the current case of herpes simplex and the associated EM because of the late timing, but antiviral medication could help to prevent further outbreaks and decrease transmission to her husband.

The patient was enthusiastic to start valacyclovir 500 mg/d for prophylaxis. For symptomatic relief, the FP prescribed a 30-g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone appointment and instructed the patient to apply it to the EM twice daily. The patient was sent for blood tests for syphilis and HIV; fortunately, both came back negative. The herpes simplex PCR test was positive for HSV2.

On a 1-week follow-up visit, the skin lesions were resolving, and the patient had no further symptoms. The patient said she understood that she should refrain from sexual intercourse if she developed lesions while on prophylaxis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash over homemade tattoo

Although the FP had never seen anything like this before, he was aware that dyes in tattoos could cause an allergic reaction. His research also suggested that sarcoidosis could occur in a tattoo, so this was part of his differential diagnosis written on the pathology form. He suggested a 4 mm punch biopsy to determine what was going on.

(See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology came back consistent with sarcoidosis. On the follow-up visit, the FP explained the diagnosis and suggested that the patient have a chest x-ray. The chest x-ray showed bilateral hilar adenopathy consistent with stage I sarcoidosis. The FP prescribed a 15-g tube of 0.05% clobetasol to treat the lesion and referred the patient to Dermatology and Pulmonology.

When the patient visited Dermatology 2 months later, most of the sarcoid plaques were flat but some remained raised and pruritic. The dermatologist offered intralesional triamcinolone for the stubborn plaques, and the patient consented. This intralesional steroid in conjunction with the topical steroid provided a good result that treated the itching and flattened the lesions. The remaining tattoo and color of the skin were not normal, but the patient was happy with the result. She had no pulmonary symptoms, and her pulmonary function tests showed a mild decrease in her diffusing capacity. She continued to see the dermatologist and pulmonologist for ongoing care of her sarcoidosis.

Photo courtesy of Amor Khachemoune, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Bae E, Bae Y, Sarabi K, et al. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1153-1160.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Although the FP had never seen anything like this before, he was aware that dyes in tattoos could cause an allergic reaction. His research also suggested that sarcoidosis could occur in a tattoo, so this was part of his differential diagnosis written on the pathology form. He suggested a 4 mm punch biopsy to determine what was going on.

(See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology came back consistent with sarcoidosis. On the follow-up visit, the FP explained the diagnosis and suggested that the patient have a chest x-ray. The chest x-ray showed bilateral hilar adenopathy consistent with stage I sarcoidosis. The FP prescribed a 15-g tube of 0.05% clobetasol to treat the lesion and referred the patient to Dermatology and Pulmonology.

When the patient visited Dermatology 2 months later, most of the sarcoid plaques were flat but some remained raised and pruritic. The dermatologist offered intralesional triamcinolone for the stubborn plaques, and the patient consented. This intralesional steroid in conjunction with the topical steroid provided a good result that treated the itching and flattened the lesions. The remaining tattoo and color of the skin were not normal, but the patient was happy with the result. She had no pulmonary symptoms, and her pulmonary function tests showed a mild decrease in her diffusing capacity. She continued to see the dermatologist and pulmonologist for ongoing care of her sarcoidosis.

Photo courtesy of Amor Khachemoune, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Bae E, Bae Y, Sarabi K, et al. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1153-1160.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Although the FP had never seen anything like this before, he was aware that dyes in tattoos could cause an allergic reaction. His research also suggested that sarcoidosis could occur in a tattoo, so this was part of his differential diagnosis written on the pathology form. He suggested a 4 mm punch biopsy to determine what was going on.

(See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology came back consistent with sarcoidosis. On the follow-up visit, the FP explained the diagnosis and suggested that the patient have a chest x-ray. The chest x-ray showed bilateral hilar adenopathy consistent with stage I sarcoidosis. The FP prescribed a 15-g tube of 0.05% clobetasol to treat the lesion and referred the patient to Dermatology and Pulmonology.

When the patient visited Dermatology 2 months later, most of the sarcoid plaques were flat but some remained raised and pruritic. The dermatologist offered intralesional triamcinolone for the stubborn plaques, and the patient consented. This intralesional steroid in conjunction with the topical steroid provided a good result that treated the itching and flattened the lesions. The remaining tattoo and color of the skin were not normal, but the patient was happy with the result. She had no pulmonary symptoms, and her pulmonary function tests showed a mild decrease in her diffusing capacity. She continued to see the dermatologist and pulmonologist for ongoing care of her sarcoidosis.

Photo courtesy of Amor Khachemoune, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Bae E, Bae Y, Sarabi K, et al. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1153-1160.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Lesions on face, arms, and legs