User login

Recurring rash on neck and axilla

The FP initially treated the area with topical ketoconazole cream, which stung, but partially improved the patient’s symptoms. Because the rash persisted, the FP performed a punch biopsy, which showed widespread epidermal acantholysis or separation of epidermal cells. This is a hallmark of pemphigus vulgaris and benign familial pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease).

Hailey-Hailey disease is an uncommon autosomal dominant inherited blistering disorder that affects connecting proteins in the epidermis, which is why histology overlaps with pemphigus. Symptoms may not present until the second or third decade of life and often occur in flexural or high friction areas, including the axilla and inguinal folds. Any skin injury may trigger a flare, including sunburn, infections, heavy sweating, or friction from clothes. Bacterial overgrowth or colonization can cause a bad odor and social isolation in severe cases.

The differential diagnosis of axillary skin disorders is broad and includes irritant contact dermatitis, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, candida intertrigo, and psoriasis. Clinical clues that favor Hailey-Hailey disease include fragile vesicles or pustules at the periphery and small focal erosions. The family history is helpful but not always known.

Some patients require topical therapy sequentially, in combination, or personalized through trial and error that addresses the inflammation, bacterial overgrowth, and fungal disease. Patients also may require long-term doxycycline therapy to suppress flares. Most patients will benefit from at least prn use of topical steroids for inflammation. Addressing sweating with topical aluminum chloride or botulinum injections can be beneficial. Low dose naltrexone, as well as afamelanotide, has shown promise in a few small case series.

The patient in this case improved with topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment bid and systemic doxycycline 100 mg bid for 2 weeks. However, he continued to require occasional rounds of oral doxycycline with flares.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The FP initially treated the area with topical ketoconazole cream, which stung, but partially improved the patient’s symptoms. Because the rash persisted, the FP performed a punch biopsy, which showed widespread epidermal acantholysis or separation of epidermal cells. This is a hallmark of pemphigus vulgaris and benign familial pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease).

Hailey-Hailey disease is an uncommon autosomal dominant inherited blistering disorder that affects connecting proteins in the epidermis, which is why histology overlaps with pemphigus. Symptoms may not present until the second or third decade of life and often occur in flexural or high friction areas, including the axilla and inguinal folds. Any skin injury may trigger a flare, including sunburn, infections, heavy sweating, or friction from clothes. Bacterial overgrowth or colonization can cause a bad odor and social isolation in severe cases.

The differential diagnosis of axillary skin disorders is broad and includes irritant contact dermatitis, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, candida intertrigo, and psoriasis. Clinical clues that favor Hailey-Hailey disease include fragile vesicles or pustules at the periphery and small focal erosions. The family history is helpful but not always known.

Some patients require topical therapy sequentially, in combination, or personalized through trial and error that addresses the inflammation, bacterial overgrowth, and fungal disease. Patients also may require long-term doxycycline therapy to suppress flares. Most patients will benefit from at least prn use of topical steroids for inflammation. Addressing sweating with topical aluminum chloride or botulinum injections can be beneficial. Low dose naltrexone, as well as afamelanotide, has shown promise in a few small case series.

The patient in this case improved with topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment bid and systemic doxycycline 100 mg bid for 2 weeks. However, he continued to require occasional rounds of oral doxycycline with flares.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The FP initially treated the area with topical ketoconazole cream, which stung, but partially improved the patient’s symptoms. Because the rash persisted, the FP performed a punch biopsy, which showed widespread epidermal acantholysis or separation of epidermal cells. This is a hallmark of pemphigus vulgaris and benign familial pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease).

Hailey-Hailey disease is an uncommon autosomal dominant inherited blistering disorder that affects connecting proteins in the epidermis, which is why histology overlaps with pemphigus. Symptoms may not present until the second or third decade of life and often occur in flexural or high friction areas, including the axilla and inguinal folds. Any skin injury may trigger a flare, including sunburn, infections, heavy sweating, or friction from clothes. Bacterial overgrowth or colonization can cause a bad odor and social isolation in severe cases.

The differential diagnosis of axillary skin disorders is broad and includes irritant contact dermatitis, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, candida intertrigo, and psoriasis. Clinical clues that favor Hailey-Hailey disease include fragile vesicles or pustules at the periphery and small focal erosions. The family history is helpful but not always known.

Some patients require topical therapy sequentially, in combination, or personalized through trial and error that addresses the inflammation, bacterial overgrowth, and fungal disease. Patients also may require long-term doxycycline therapy to suppress flares. Most patients will benefit from at least prn use of topical steroids for inflammation. Addressing sweating with topical aluminum chloride or botulinum injections can be beneficial. Low dose naltrexone, as well as afamelanotide, has shown promise in a few small case series.

The patient in this case improved with topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment bid and systemic doxycycline 100 mg bid for 2 weeks. However, he continued to require occasional rounds of oral doxycycline with flares.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Chronic blistering rash on hands

A 60-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chronic, recurrent pruritic rash on his hands and neck. He noted that the rash developed into blisters, which he would pick until they scabbed over. The rash only manifested on sun-exposed areas.

The patient did not take any medications. He admitted to drinking alcohol (4 beers/d on average) and had roughly a 50-pack year history of smoking. There was no family history of similar symptoms.

On physical exam, we noted erosions and ulcerations with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of his hands, along with milia on the knuckle pads (FIGURE 1A). Further skin examination revealed hypopigmented scars on his shoulders and lower extremities bilaterally, with hypertrichosis of the cheeks (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

Based on the clinical presentation and the patient’s history of smoking and alcohol consumption, we suspected that this was a case of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). Laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, iron studies, and liver function tests, were ordered. These revealed elevated levels of serum alanine transaminase (116 IU/L; reference range, 20-60 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (184 IU/L; reference range, 6-34 IU/L in men), and ferritin (1594 ng/mL; reference range, 12-300 ng/mL in men), consistent with PCT. Total porphyrins were then measured and found to be elevated (128.5 mcg/dL; reference range, 0 to 1 mcg/dL), which confirmed the diagnosis. Further testing revealed that the patient was positive for both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus infection.

While PCT is the most common porphyria worldwide, it is nonetheless a rare disorder that results from deficient activity (< 20% of normal) of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), the fifth enzyme in the heme synthetic pathway.1,2 It is typically (~75% cases) an acquired disorder of mid- to late adulthood and more commonly affects males.1 In the remainder of cases, patients have a genetic predisposition—a mutation of the UROD or HFE gene. Patients with a genetic predisposition may present earlier.2,3 Susceptibility factors for both forms of PCT include chronic alcohol use, HCV and/or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, estrogen therapy, and a history of chronic/heavy smoking.1,4

Cutaneous manifestations of PCT are caused by the accumulation of porphyrins, which are photo-oxidized in the skin.1 Findings include photosensitivity, skin fragility, blistering, scarring, hypo- or hyperpigmentation, and milia in sun-exposed areas, such as the dorsum of the hands, forearms, face, ears, neck, and feet.1,2 Hypertrichosis can occur, particularly on the cheeks and forearms.1 Elevated transaminases often accompany cutaneous findings, due to porphyrin accumulation in hepatocytes and the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol, HCV infection, or iron overload.5 Iron overload, in part due to dysregulation of hepcidin, can lead to increased serum ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation.1

Differential includes autoimmune and autosomal conditions

Diseases that manifest with blistering, elevated porphyrins or porphyrin precursors, and iron overload should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder that occurs when antibodies attack hemidesmosomes in the epidermis. It commonly manifests in the elderly and classically presents with tense bullae, typically on the trunk, abdomen, and proximal extremities. Serologic testing and biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.6

Continue to: Pseudoporphyria...

Pseudoporphyria has a similar presentation to PCT but with no abnormalities in porphyrin metabolism. Risk factors include UV radiation exposure; use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, and retinoids; chronic renal failure; and hemodialysis.7

Acute intermittent porphyria is an autosomal dominant disorder due to deficiency of porphobilinogen deaminase, a heme biosynthetic enzyme. Clinical manifestations usually arise in adulthood and include neurovisceral attacks (eg, abdominal pain, vomiting, muscle weakness). Diagnosis during an acute attack can be made by measuring urinary 5-aminolaevulinc acid and porphobilinogen.1

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder most commonly due to mutations in the HFE gene. Patients typically have iron overload and abnormal liver function test results. The main cutaneous finding is skin hyperpigmentation. Patients also may develop diabetes mellitus, arthropathy, cardiac disease, and hypopituitarism, although most are diagnosed with asymptomatic disease following routine laboratory studies.8

Confirm the diagnosis with total porphyrin measurement

The preferred initial test to confirm the diagnosis of PCT is measurement of plasma or urine total porphyrins, which will be elevated.1 Further testing is then performed to discern PCT from the other, less common cutaneous porphyrias.1 If needed, biopsy can be done to exclude other diagnoses. Testing for HIV and viral hepatitis infection may be performed when clinical suspicion is high.1 Testing for UROD and HFE mutations may also be advised.1

Treatment choice is guided by iron levels

For patients with normal iron levels, low-dose hydroxychloroquine 100 mg or chloroquine 125 mg twice per week can be used until restoration of normal plasma or urine porphyrin levels has been achieved for several months.1 For those with iron excess (serum ferritin > 600 ng/dL), repeat phlebotomy is the preferred treatment; a unit of blood (350-500 mL) is typically removed, as tolerated, until iron stores return to normal.1 In severe cases of PCT, these therapies can be used in combination.1 Clinical remission with these methods can be expected within 6 to 9 months.9

Continue to: In addition...

In addition, it is important to provide patient education regarding proper sun protection and risk factor modification.1 Underlying HIV and viral hepatitis infection should be managed appropriately by the relevant specialists.

Our patient was counseled on proper sun protection and encouraged to cease alcohol consumption and smoking. We subsequently referred him to Hepatology for the treatment of his liver disease. Given that the patient’s ferritin level was so high (1594 ng/mL), serial phlebotomy was initiated twice monthly until levels reached the lower limit of normal. He was also started on direct-acting antiviral therapy with Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) for 12 weeks for treatment of his HCV and is currently in remission.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher G. Bazewicz, MD, Department of Dermatology, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

2. Méndez M, Poblete-Gutiérrez P, García-Bravo M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of familial porphyria cutanea tarda in Spain: characterization of 10 novel mutations in the UROD gene. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:501-507.

3. Brady JJ, Jackson HA, Roberts AG, et al. Co-inheritance of mutations in the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and hemochromatosis genes accelerates the onset of porphyria cutanea tarda. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:868-874.

4. Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, et al. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:297-302, 302.e1.

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Alonso A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:689-692.

6. Di Zenzo G, Della Torre R, Zambruno G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: from the clinic to the bench. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:3-16.

7. Green JJ, Manders SM. Pseudoporphyria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:100-108.

8. Crownover BK, Covey CJ. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:183-190.

9. Sarkany RP. The management of porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:225-232.

A 60-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chronic, recurrent pruritic rash on his hands and neck. He noted that the rash developed into blisters, which he would pick until they scabbed over. The rash only manifested on sun-exposed areas.

The patient did not take any medications. He admitted to drinking alcohol (4 beers/d on average) and had roughly a 50-pack year history of smoking. There was no family history of similar symptoms.

On physical exam, we noted erosions and ulcerations with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of his hands, along with milia on the knuckle pads (FIGURE 1A). Further skin examination revealed hypopigmented scars on his shoulders and lower extremities bilaterally, with hypertrichosis of the cheeks (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

Based on the clinical presentation and the patient’s history of smoking and alcohol consumption, we suspected that this was a case of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). Laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, iron studies, and liver function tests, were ordered. These revealed elevated levels of serum alanine transaminase (116 IU/L; reference range, 20-60 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (184 IU/L; reference range, 6-34 IU/L in men), and ferritin (1594 ng/mL; reference range, 12-300 ng/mL in men), consistent with PCT. Total porphyrins were then measured and found to be elevated (128.5 mcg/dL; reference range, 0 to 1 mcg/dL), which confirmed the diagnosis. Further testing revealed that the patient was positive for both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus infection.

While PCT is the most common porphyria worldwide, it is nonetheless a rare disorder that results from deficient activity (< 20% of normal) of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), the fifth enzyme in the heme synthetic pathway.1,2 It is typically (~75% cases) an acquired disorder of mid- to late adulthood and more commonly affects males.1 In the remainder of cases, patients have a genetic predisposition—a mutation of the UROD or HFE gene. Patients with a genetic predisposition may present earlier.2,3 Susceptibility factors for both forms of PCT include chronic alcohol use, HCV and/or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, estrogen therapy, and a history of chronic/heavy smoking.1,4

Cutaneous manifestations of PCT are caused by the accumulation of porphyrins, which are photo-oxidized in the skin.1 Findings include photosensitivity, skin fragility, blistering, scarring, hypo- or hyperpigmentation, and milia in sun-exposed areas, such as the dorsum of the hands, forearms, face, ears, neck, and feet.1,2 Hypertrichosis can occur, particularly on the cheeks and forearms.1 Elevated transaminases often accompany cutaneous findings, due to porphyrin accumulation in hepatocytes and the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol, HCV infection, or iron overload.5 Iron overload, in part due to dysregulation of hepcidin, can lead to increased serum ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation.1

Differential includes autoimmune and autosomal conditions

Diseases that manifest with blistering, elevated porphyrins or porphyrin precursors, and iron overload should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder that occurs when antibodies attack hemidesmosomes in the epidermis. It commonly manifests in the elderly and classically presents with tense bullae, typically on the trunk, abdomen, and proximal extremities. Serologic testing and biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.6

Continue to: Pseudoporphyria...

Pseudoporphyria has a similar presentation to PCT but with no abnormalities in porphyrin metabolism. Risk factors include UV radiation exposure; use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, and retinoids; chronic renal failure; and hemodialysis.7

Acute intermittent porphyria is an autosomal dominant disorder due to deficiency of porphobilinogen deaminase, a heme biosynthetic enzyme. Clinical manifestations usually arise in adulthood and include neurovisceral attacks (eg, abdominal pain, vomiting, muscle weakness). Diagnosis during an acute attack can be made by measuring urinary 5-aminolaevulinc acid and porphobilinogen.1

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder most commonly due to mutations in the HFE gene. Patients typically have iron overload and abnormal liver function test results. The main cutaneous finding is skin hyperpigmentation. Patients also may develop diabetes mellitus, arthropathy, cardiac disease, and hypopituitarism, although most are diagnosed with asymptomatic disease following routine laboratory studies.8

Confirm the diagnosis with total porphyrin measurement

The preferred initial test to confirm the diagnosis of PCT is measurement of plasma or urine total porphyrins, which will be elevated.1 Further testing is then performed to discern PCT from the other, less common cutaneous porphyrias.1 If needed, biopsy can be done to exclude other diagnoses. Testing for HIV and viral hepatitis infection may be performed when clinical suspicion is high.1 Testing for UROD and HFE mutations may also be advised.1

Treatment choice is guided by iron levels

For patients with normal iron levels, low-dose hydroxychloroquine 100 mg or chloroquine 125 mg twice per week can be used until restoration of normal plasma or urine porphyrin levels has been achieved for several months.1 For those with iron excess (serum ferritin > 600 ng/dL), repeat phlebotomy is the preferred treatment; a unit of blood (350-500 mL) is typically removed, as tolerated, until iron stores return to normal.1 In severe cases of PCT, these therapies can be used in combination.1 Clinical remission with these methods can be expected within 6 to 9 months.9

Continue to: In addition...

In addition, it is important to provide patient education regarding proper sun protection and risk factor modification.1 Underlying HIV and viral hepatitis infection should be managed appropriately by the relevant specialists.

Our patient was counseled on proper sun protection and encouraged to cease alcohol consumption and smoking. We subsequently referred him to Hepatology for the treatment of his liver disease. Given that the patient’s ferritin level was so high (1594 ng/mL), serial phlebotomy was initiated twice monthly until levels reached the lower limit of normal. He was also started on direct-acting antiviral therapy with Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) for 12 weeks for treatment of his HCV and is currently in remission.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher G. Bazewicz, MD, Department of Dermatology, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

A 60-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chronic, recurrent pruritic rash on his hands and neck. He noted that the rash developed into blisters, which he would pick until they scabbed over. The rash only manifested on sun-exposed areas.

The patient did not take any medications. He admitted to drinking alcohol (4 beers/d on average) and had roughly a 50-pack year history of smoking. There was no family history of similar symptoms.

On physical exam, we noted erosions and ulcerations with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of his hands, along with milia on the knuckle pads (FIGURE 1A). Further skin examination revealed hypopigmented scars on his shoulders and lower extremities bilaterally, with hypertrichosis of the cheeks (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

Based on the clinical presentation and the patient’s history of smoking and alcohol consumption, we suspected that this was a case of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). Laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, iron studies, and liver function tests, were ordered. These revealed elevated levels of serum alanine transaminase (116 IU/L; reference range, 20-60 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (184 IU/L; reference range, 6-34 IU/L in men), and ferritin (1594 ng/mL; reference range, 12-300 ng/mL in men), consistent with PCT. Total porphyrins were then measured and found to be elevated (128.5 mcg/dL; reference range, 0 to 1 mcg/dL), which confirmed the diagnosis. Further testing revealed that the patient was positive for both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus infection.

While PCT is the most common porphyria worldwide, it is nonetheless a rare disorder that results from deficient activity (< 20% of normal) of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), the fifth enzyme in the heme synthetic pathway.1,2 It is typically (~75% cases) an acquired disorder of mid- to late adulthood and more commonly affects males.1 In the remainder of cases, patients have a genetic predisposition—a mutation of the UROD or HFE gene. Patients with a genetic predisposition may present earlier.2,3 Susceptibility factors for both forms of PCT include chronic alcohol use, HCV and/or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, estrogen therapy, and a history of chronic/heavy smoking.1,4

Cutaneous manifestations of PCT are caused by the accumulation of porphyrins, which are photo-oxidized in the skin.1 Findings include photosensitivity, skin fragility, blistering, scarring, hypo- or hyperpigmentation, and milia in sun-exposed areas, such as the dorsum of the hands, forearms, face, ears, neck, and feet.1,2 Hypertrichosis can occur, particularly on the cheeks and forearms.1 Elevated transaminases often accompany cutaneous findings, due to porphyrin accumulation in hepatocytes and the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol, HCV infection, or iron overload.5 Iron overload, in part due to dysregulation of hepcidin, can lead to increased serum ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation.1

Differential includes autoimmune and autosomal conditions

Diseases that manifest with blistering, elevated porphyrins or porphyrin precursors, and iron overload should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder that occurs when antibodies attack hemidesmosomes in the epidermis. It commonly manifests in the elderly and classically presents with tense bullae, typically on the trunk, abdomen, and proximal extremities. Serologic testing and biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.6

Continue to: Pseudoporphyria...

Pseudoporphyria has a similar presentation to PCT but with no abnormalities in porphyrin metabolism. Risk factors include UV radiation exposure; use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, and retinoids; chronic renal failure; and hemodialysis.7

Acute intermittent porphyria is an autosomal dominant disorder due to deficiency of porphobilinogen deaminase, a heme biosynthetic enzyme. Clinical manifestations usually arise in adulthood and include neurovisceral attacks (eg, abdominal pain, vomiting, muscle weakness). Diagnosis during an acute attack can be made by measuring urinary 5-aminolaevulinc acid and porphobilinogen.1

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder most commonly due to mutations in the HFE gene. Patients typically have iron overload and abnormal liver function test results. The main cutaneous finding is skin hyperpigmentation. Patients also may develop diabetes mellitus, arthropathy, cardiac disease, and hypopituitarism, although most are diagnosed with asymptomatic disease following routine laboratory studies.8

Confirm the diagnosis with total porphyrin measurement

The preferred initial test to confirm the diagnosis of PCT is measurement of plasma or urine total porphyrins, which will be elevated.1 Further testing is then performed to discern PCT from the other, less common cutaneous porphyrias.1 If needed, biopsy can be done to exclude other diagnoses. Testing for HIV and viral hepatitis infection may be performed when clinical suspicion is high.1 Testing for UROD and HFE mutations may also be advised.1

Treatment choice is guided by iron levels

For patients with normal iron levels, low-dose hydroxychloroquine 100 mg or chloroquine 125 mg twice per week can be used until restoration of normal plasma or urine porphyrin levels has been achieved for several months.1 For those with iron excess (serum ferritin > 600 ng/dL), repeat phlebotomy is the preferred treatment; a unit of blood (350-500 mL) is typically removed, as tolerated, until iron stores return to normal.1 In severe cases of PCT, these therapies can be used in combination.1 Clinical remission with these methods can be expected within 6 to 9 months.9

Continue to: In addition...

In addition, it is important to provide patient education regarding proper sun protection and risk factor modification.1 Underlying HIV and viral hepatitis infection should be managed appropriately by the relevant specialists.

Our patient was counseled on proper sun protection and encouraged to cease alcohol consumption and smoking. We subsequently referred him to Hepatology for the treatment of his liver disease. Given that the patient’s ferritin level was so high (1594 ng/mL), serial phlebotomy was initiated twice monthly until levels reached the lower limit of normal. He was also started on direct-acting antiviral therapy with Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) for 12 weeks for treatment of his HCV and is currently in remission.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher G. Bazewicz, MD, Department of Dermatology, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

2. Méndez M, Poblete-Gutiérrez P, García-Bravo M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of familial porphyria cutanea tarda in Spain: characterization of 10 novel mutations in the UROD gene. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:501-507.

3. Brady JJ, Jackson HA, Roberts AG, et al. Co-inheritance of mutations in the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and hemochromatosis genes accelerates the onset of porphyria cutanea tarda. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:868-874.

4. Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, et al. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:297-302, 302.e1.

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Alonso A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:689-692.

6. Di Zenzo G, Della Torre R, Zambruno G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: from the clinic to the bench. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:3-16.

7. Green JJ, Manders SM. Pseudoporphyria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:100-108.

8. Crownover BK, Covey CJ. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:183-190.

9. Sarkany RP. The management of porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:225-232.

1. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

2. Méndez M, Poblete-Gutiérrez P, García-Bravo M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of familial porphyria cutanea tarda in Spain: characterization of 10 novel mutations in the UROD gene. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:501-507.

3. Brady JJ, Jackson HA, Roberts AG, et al. Co-inheritance of mutations in the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and hemochromatosis genes accelerates the onset of porphyria cutanea tarda. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:868-874.

4. Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, et al. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:297-302, 302.e1.

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Alonso A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:689-692.

6. Di Zenzo G, Della Torre R, Zambruno G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: from the clinic to the bench. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:3-16.

7. Green JJ, Manders SM. Pseudoporphyria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:100-108.

8. Crownover BK, Covey CJ. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:183-190.

9. Sarkany RP. The management of porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:225-232.

Red patches and thin plaques on feet

The FP conducted a physical exam and noticed bilateral dorsal foot dermatitis with occasional small vesicles and lichenified papules, which was suggestive of chronic contact or irritant dermatitis. The patient’s favorite pair of boots offered another clue as to the most likely contact allergens. (The boots were leather, and leather is treated with tanning agents and dyes.) A biopsy was not performed but would be expected to show spongiosis with some degree of lichenification (thickening of the dermis)—a sign of the acute on chronic nature of this process. The diagnosis of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis was made empirically.

The differential diagnosis for rashes on the feet can be broad and includes common tinea pedis, pitted keratolysis, stasis dermatitis, psoriasis, eczemas of various types, keratoderma, and contact dermatitis.

Many patients misconstrue that materials they use every day are exempt from becoming allergens. In counseling patients about this, point out that contact allergens often arise from repeated exposure. For example, dentists often develop dental amalgam allergies, hair professionals develop hair dye allergies, and machinists commonly develop cutting oil allergies. These reactions can and do occur years into their use.

The patient was started on topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment bid for 3 weeks, which provided quick relief and cleared his feet of the patches and plaques. He continued to wear his boots until contact allergy patch testing was performed in the office over a series of 3 days. This revealed an allergy to chromium, a common leather tanning agent. The patient was advised to avoid leather products including jackets, car upholstery, and gloves. After he carefully chose different footwear without a leather insole or tongue, the patient required no further therapy and remained clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The FP conducted a physical exam and noticed bilateral dorsal foot dermatitis with occasional small vesicles and lichenified papules, which was suggestive of chronic contact or irritant dermatitis. The patient’s favorite pair of boots offered another clue as to the most likely contact allergens. (The boots were leather, and leather is treated with tanning agents and dyes.) A biopsy was not performed but would be expected to show spongiosis with some degree of lichenification (thickening of the dermis)—a sign of the acute on chronic nature of this process. The diagnosis of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis was made empirically.

The differential diagnosis for rashes on the feet can be broad and includes common tinea pedis, pitted keratolysis, stasis dermatitis, psoriasis, eczemas of various types, keratoderma, and contact dermatitis.

Many patients misconstrue that materials they use every day are exempt from becoming allergens. In counseling patients about this, point out that contact allergens often arise from repeated exposure. For example, dentists often develop dental amalgam allergies, hair professionals develop hair dye allergies, and machinists commonly develop cutting oil allergies. These reactions can and do occur years into their use.

The patient was started on topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment bid for 3 weeks, which provided quick relief and cleared his feet of the patches and plaques. He continued to wear his boots until contact allergy patch testing was performed in the office over a series of 3 days. This revealed an allergy to chromium, a common leather tanning agent. The patient was advised to avoid leather products including jackets, car upholstery, and gloves. After he carefully chose different footwear without a leather insole or tongue, the patient required no further therapy and remained clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The FP conducted a physical exam and noticed bilateral dorsal foot dermatitis with occasional small vesicles and lichenified papules, which was suggestive of chronic contact or irritant dermatitis. The patient’s favorite pair of boots offered another clue as to the most likely contact allergens. (The boots were leather, and leather is treated with tanning agents and dyes.) A biopsy was not performed but would be expected to show spongiosis with some degree of lichenification (thickening of the dermis)—a sign of the acute on chronic nature of this process. The diagnosis of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis was made empirically.

The differential diagnosis for rashes on the feet can be broad and includes common tinea pedis, pitted keratolysis, stasis dermatitis, psoriasis, eczemas of various types, keratoderma, and contact dermatitis.

Many patients misconstrue that materials they use every day are exempt from becoming allergens. In counseling patients about this, point out that contact allergens often arise from repeated exposure. For example, dentists often develop dental amalgam allergies, hair professionals develop hair dye allergies, and machinists commonly develop cutting oil allergies. These reactions can and do occur years into their use.

The patient was started on topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment bid for 3 weeks, which provided quick relief and cleared his feet of the patches and plaques. He continued to wear his boots until contact allergy patch testing was performed in the office over a series of 3 days. This revealed an allergy to chromium, a common leather tanning agent. The patient was advised to avoid leather products including jackets, car upholstery, and gloves. After he carefully chose different footwear without a leather insole or tongue, the patient required no further therapy and remained clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

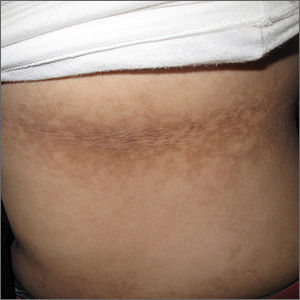

Dark patches around the trunk

The FP noticed a lacy net-like or reticulate appearance and thin brown papules to warty plaques over the trunk and recognized this condition as confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP). A potassium hydroxide (KOH) test of a skin scraping failed to reveal yeast forms or hyphae. The FP determined that a biopsy was not necessary for diagnosis due to the distinct clinical appearance and negative KOH test. However, a biopsy could have distinguished this presentation from similar appearing disorders, including acanthosis nigricans and pityriasis versicolor.

CARP is an uncommon disorder of keratinization that affects adolescents and young adults, and is more common in Caucasians. A classic presentation involves the neck, chest, and abdomen. The differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans and pityriasis versicolor, as well as more rare disorders that include Darier disease and keratosis follicularis.

There appears to be an association between the disorder and weight (specifically, being overweight). In addition, some familial cases have been reported.

Most recently, Dietzia papillomatosis, a gram-positive actinomycete has been implicated as a likely cause, which supports antibiotic therapy as the first-line approach. Minocycline 50 mg bid for 6 weeks clears the papules and plaques for most patients. Azithromycin and clarithromycin are alternatives, with various dosing strategies lasting 6 to 12 weeks. Complete clearance may take months to more than a year. About 15% of patients will experience recurrence.

This patient was treated with minocycline 50 mg bid for 12 weeks, a more common strategy at the time she was diagnosed. This led to complete clearance at 3 months, and she remained clear a year after beginning treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The FP noticed a lacy net-like or reticulate appearance and thin brown papules to warty plaques over the trunk and recognized this condition as confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP). A potassium hydroxide (KOH) test of a skin scraping failed to reveal yeast forms or hyphae. The FP determined that a biopsy was not necessary for diagnosis due to the distinct clinical appearance and negative KOH test. However, a biopsy could have distinguished this presentation from similar appearing disorders, including acanthosis nigricans and pityriasis versicolor.

CARP is an uncommon disorder of keratinization that affects adolescents and young adults, and is more common in Caucasians. A classic presentation involves the neck, chest, and abdomen. The differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans and pityriasis versicolor, as well as more rare disorders that include Darier disease and keratosis follicularis.

There appears to be an association between the disorder and weight (specifically, being overweight). In addition, some familial cases have been reported.

Most recently, Dietzia papillomatosis, a gram-positive actinomycete has been implicated as a likely cause, which supports antibiotic therapy as the first-line approach. Minocycline 50 mg bid for 6 weeks clears the papules and plaques for most patients. Azithromycin and clarithromycin are alternatives, with various dosing strategies lasting 6 to 12 weeks. Complete clearance may take months to more than a year. About 15% of patients will experience recurrence.

This patient was treated with minocycline 50 mg bid for 12 weeks, a more common strategy at the time she was diagnosed. This led to complete clearance at 3 months, and she remained clear a year after beginning treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The FP noticed a lacy net-like or reticulate appearance and thin brown papules to warty plaques over the trunk and recognized this condition as confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP). A potassium hydroxide (KOH) test of a skin scraping failed to reveal yeast forms or hyphae. The FP determined that a biopsy was not necessary for diagnosis due to the distinct clinical appearance and negative KOH test. However, a biopsy could have distinguished this presentation from similar appearing disorders, including acanthosis nigricans and pityriasis versicolor.

CARP is an uncommon disorder of keratinization that affects adolescents and young adults, and is more common in Caucasians. A classic presentation involves the neck, chest, and abdomen. The differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans and pityriasis versicolor, as well as more rare disorders that include Darier disease and keratosis follicularis.

There appears to be an association between the disorder and weight (specifically, being overweight). In addition, some familial cases have been reported.

Most recently, Dietzia papillomatosis, a gram-positive actinomycete has been implicated as a likely cause, which supports antibiotic therapy as the first-line approach. Minocycline 50 mg bid for 6 weeks clears the papules and plaques for most patients. Azithromycin and clarithromycin are alternatives, with various dosing strategies lasting 6 to 12 weeks. Complete clearance may take months to more than a year. About 15% of patients will experience recurrence.

This patient was treated with minocycline 50 mg bid for 12 weeks, a more common strategy at the time she was diagnosed. This led to complete clearance at 3 months, and she remained clear a year after beginning treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Skin changes on abdomen

The FP suspected that the child had morphea because the skin was somewhat firm and thickened, and there was hypo- and hyperpigmentation.

Morphea is a localized type of scleroderma and may be seen in children. Fortunately, it does not involve the internal organs. There are no blood tests needed for the diagnosis and antinuclear antibodies should be normal. While a punch biopsy could be considered in less obvious cases in older children, it is probably unnecessary to put a 5-year-old child through the trauma of a biopsy.

The FP referred the child to a dermatologist to confirm the diagnosis and initiate treatment. Typical treatments include topical mid- to high-potency steroids and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1204-1212.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected that the child had morphea because the skin was somewhat firm and thickened, and there was hypo- and hyperpigmentation.

Morphea is a localized type of scleroderma and may be seen in children. Fortunately, it does not involve the internal organs. There are no blood tests needed for the diagnosis and antinuclear antibodies should be normal. While a punch biopsy could be considered in less obvious cases in older children, it is probably unnecessary to put a 5-year-old child through the trauma of a biopsy.

The FP referred the child to a dermatologist to confirm the diagnosis and initiate treatment. Typical treatments include topical mid- to high-potency steroids and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1204-1212.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected that the child had morphea because the skin was somewhat firm and thickened, and there was hypo- and hyperpigmentation.

Morphea is a localized type of scleroderma and may be seen in children. Fortunately, it does not involve the internal organs. There are no blood tests needed for the diagnosis and antinuclear antibodies should be normal. While a punch biopsy could be considered in less obvious cases in older children, it is probably unnecessary to put a 5-year-old child through the trauma of a biopsy.

The FP referred the child to a dermatologist to confirm the diagnosis and initiate treatment. Typical treatments include topical mid- to high-potency steroids and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1204-1212.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Telangiectasias with tight skin

The FP suspected that the patient had CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias) syndrome also known as limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (LcSSc). He examined her arms and found that she had firm nodules around the elbows consistent with calcinosis. Further history revealed Raynaud's phenomenon. This clinched the diagnosis of CREST syndrome. The FP ordered blood tests, a chest x-ray (CXR), and pulmonary function tests to determine if there was pulmonary involvement and to learn more about possible systemic effects of her disease.

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) is characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by variable tissue fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs. Systemic sclerosis can be diffuse or limited to the skin and adjacent tissues (LcSSc). Patients with LcSSc usually have skin sclerosis that is restricted to the hands and, to a lesser extent, the face and neck.

The patient’s antinuclear antibody test was positive with a speckled nucleolar staining pattern, which is a common finding in systemic sclerosis. Her CXR showed evidence of interstitial lung disease with a ground glass pattern. Her pulmonary function test showed a diminished diffusion capacity. Pulmonary disease is seen in all types of systemic sclerosis and not diagnostic for one type. The patient was referred to Rheumatology for further diagnosis and management.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1204-1212.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected that the patient had CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias) syndrome also known as limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (LcSSc). He examined her arms and found that she had firm nodules around the elbows consistent with calcinosis. Further history revealed Raynaud's phenomenon. This clinched the diagnosis of CREST syndrome. The FP ordered blood tests, a chest x-ray (CXR), and pulmonary function tests to determine if there was pulmonary involvement and to learn more about possible systemic effects of her disease.

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) is characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by variable tissue fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs. Systemic sclerosis can be diffuse or limited to the skin and adjacent tissues (LcSSc). Patients with LcSSc usually have skin sclerosis that is restricted to the hands and, to a lesser extent, the face and neck.

The patient’s antinuclear antibody test was positive with a speckled nucleolar staining pattern, which is a common finding in systemic sclerosis. Her CXR showed evidence of interstitial lung disease with a ground glass pattern. Her pulmonary function test showed a diminished diffusion capacity. Pulmonary disease is seen in all types of systemic sclerosis and not diagnostic for one type. The patient was referred to Rheumatology for further diagnosis and management.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1204-1212.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected that the patient had CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias) syndrome also known as limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (LcSSc). He examined her arms and found that she had firm nodules around the elbows consistent with calcinosis. Further history revealed Raynaud's phenomenon. This clinched the diagnosis of CREST syndrome. The FP ordered blood tests, a chest x-ray (CXR), and pulmonary function tests to determine if there was pulmonary involvement and to learn more about possible systemic effects of her disease.

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) is characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by variable tissue fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs. Systemic sclerosis can be diffuse or limited to the skin and adjacent tissues (LcSSc). Patients with LcSSc usually have skin sclerosis that is restricted to the hands and, to a lesser extent, the face and neck.

The patient’s antinuclear antibody test was positive with a speckled nucleolar staining pattern, which is a common finding in systemic sclerosis. Her CXR showed evidence of interstitial lung disease with a ground glass pattern. Her pulmonary function test showed a diminished diffusion capacity. Pulmonary disease is seen in all types of systemic sclerosis and not diagnostic for one type. The patient was referred to Rheumatology for further diagnosis and management.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1204-1212.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Persistent rash on the sole

A 52-year-old Chinese woman presented to a tertiary hospital in Singapore with a 3-month history of persistent and intermittently painful rashes over her right calf and foot (FIGURE). The patient had pancytopenia due to ongoing chemotherapy for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. She was systemically well and denied other dermatoses. Examination demonstrated scattered crops of tense hemorrhagic vesicles, each surrounded by a livid purpuric base, over the right plantar aspect of the foot, with areas of eschar over the right medial hallux. No allodynia, hyperaesthesia, or lymphadenopathy was noted.

A punch biopsy of an intact vesicle was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis:

Herpes zoster

Histopathologic examination showed full-thickness epidermal necrosis with ballooning degeneration resulting in an intra-epidermal blister. Multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear moulding were seen within the blister cavity. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (GMS), acid-fast, and Gram stains were negative. Granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgM, and C3 were seen intramurally. DNA analysis of vesicular fluid was positive for varicella zoster virus (VZV). A diagnosis of herpes zoster (HZ) of the right S1 dermatome with primary obliterative vasculitis was established.

Immunocompromised people—those who have impaired T-cell immunity (eg, recipients of organ or hematopoietic stem-cell transplants), take immunosuppressive therapy, or have lymphoma, leukemia, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection—have an increased risk for HZ. For example, in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), HZ uniquely manifests as recurrent shingles. An estimated 20% to 30% of HIV-infected patients will have more than 1 episode of HZ, which may involve the same or different dermatomes.1,2 Furthermore, HZ in this population is more commonly associated with atypical presentations.3

What an atypical presentation may look like

In immunocompromised patients, HZ may present with atypical cutaneous manifestations or with atypical generalized symptoms.

Atypical cutaneous manifestations, as in disseminated zoster, manifest with multiple hyperkeratotic papules (3-20 mm in diameter) that follow no dermatomal pattern. These lesions may be chronic, persisting for months or years, and may be associated with acyclovir-resistant strains of VZV.2,3 Another dermatologic variant is ecthymatous VZV, which manifests with multiple large (10-30 mm) punched-out ulcerations with a central black eschar and a peripheral rim of vesicles.4 Viral folliculitis—in which infection is limited to the hair follicle, with no associated blisters—has also been reported in atypical HZ.5

Our patient presented with hemorrhagic vesicles mimicking vasculitic lesions, which had persisted over a 3-month period with intermittent localized pain. It has been proposed that in atypical presentations, the reactivated VZV spreads transaxonally from adjacent nerves to the outermost adventitial layer of the arterial wall, leading to a vasculitic appearance of the vesicles.6 Viral-induced vasculitis may also result either directly from infection of the blood vessels or secondary to vascular damage from an inflammatory immune complex–mediated reaction, cell-mediated hypersensitivity, or inflammation due to immune dysregulation.7,8

Continue to: Differential includes vesiculobullous conditions

Differential includes vesiculobullous conditions

There are several important items to consider in the differential.

Cutaneous vasculitis, in severe cases, may manifest with vesicles or bullae that resemble the lesions seen in HZ. However, its unilateral nature and distribution distinguish it.

Angioinvasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients may manifest with scattered ulceronecrotic lesions to purpuric vesiculobullous dermatoses.9 However, no fungal organisms were seen on GMS staining of the biopsied tissue.

Atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease tends to affect adults and is associated with Coxsackievirus A6 infection.10 It may manifest as generalized vesiculobullous exanthem resembling varicella. The chronic nature and restricted extent of the patient’s rash made this diagnosis unlikely.

Successful management depends on timely identification

Although most cases of HZ can be diagnosed clinically, atypical rashes may require a biopsy and direct immunofluorescence assay for VZV antigen or a polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assay for VZV DNA in cells from the base of blisters. Therefore, it is important to consider the diagnosis of HZ in immunocompromised patients presenting with an atypical rash to avoid misdiagnosis and costly testing.

Continue to: Our patient was treated...

Our patient was treated with oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times/day for 10 days, with prompt resolution of her rash.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joel Hua-Liang Lim, MBBS, MRCP, MMed, 1 Mandalay Road, Singapore 308205; [email protected]

1. LeBoit PE, Limova M, Yen TS, et al. Chronic verrucous varicella-zoster virus infection in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): histologic and molecular biologic findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:1-7.

2. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

3. Weinberg JM, Mysliwiec A, Turiansky GW, et al. Viral folliculitis: atypical presentations of herpes simplex, herpes zoster, and molluscum contagiosum. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:983-986.

4. Gilson IH, Barnett JH, Conant MA, et al. Disseminated ecthymatous herpes varicella zoster virus infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:637-642.

5. Løkke BJ, Weismann K, Mathiesen L, et al. Atypical varicella-zoster infection in AIDS. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:123-125.

6. Uhoda I, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Varicella-zoster virus vasculitis: a case of recurrent varicella without epidermal involvement. Dermatology. 2000;200:173-175.

7. Teng GG, Chatham WW. Vasculitis related to viral and other microbial agents. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:226-243.

8. Nagel MA, Gilden D. Developments in varicella zoster virus vasculopathy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:12.

9. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2010;36:1-53.

10. Lott JP, Liu K, Landry M-L, et al. Atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:736-741.

A 52-year-old Chinese woman presented to a tertiary hospital in Singapore with a 3-month history of persistent and intermittently painful rashes over her right calf and foot (FIGURE). The patient had pancytopenia due to ongoing chemotherapy for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. She was systemically well and denied other dermatoses. Examination demonstrated scattered crops of tense hemorrhagic vesicles, each surrounded by a livid purpuric base, over the right plantar aspect of the foot, with areas of eschar over the right medial hallux. No allodynia, hyperaesthesia, or lymphadenopathy was noted.

A punch biopsy of an intact vesicle was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis:

Herpes zoster

Histopathologic examination showed full-thickness epidermal necrosis with ballooning degeneration resulting in an intra-epidermal blister. Multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear moulding were seen within the blister cavity. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (GMS), acid-fast, and Gram stains were negative. Granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgM, and C3 were seen intramurally. DNA analysis of vesicular fluid was positive for varicella zoster virus (VZV). A diagnosis of herpes zoster (HZ) of the right S1 dermatome with primary obliterative vasculitis was established.

Immunocompromised people—those who have impaired T-cell immunity (eg, recipients of organ or hematopoietic stem-cell transplants), take immunosuppressive therapy, or have lymphoma, leukemia, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection—have an increased risk for HZ. For example, in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), HZ uniquely manifests as recurrent shingles. An estimated 20% to 30% of HIV-infected patients will have more than 1 episode of HZ, which may involve the same or different dermatomes.1,2 Furthermore, HZ in this population is more commonly associated with atypical presentations.3

What an atypical presentation may look like

In immunocompromised patients, HZ may present with atypical cutaneous manifestations or with atypical generalized symptoms.

Atypical cutaneous manifestations, as in disseminated zoster, manifest with multiple hyperkeratotic papules (3-20 mm in diameter) that follow no dermatomal pattern. These lesions may be chronic, persisting for months or years, and may be associated with acyclovir-resistant strains of VZV.2,3 Another dermatologic variant is ecthymatous VZV, which manifests with multiple large (10-30 mm) punched-out ulcerations with a central black eschar and a peripheral rim of vesicles.4 Viral folliculitis—in which infection is limited to the hair follicle, with no associated blisters—has also been reported in atypical HZ.5

Our patient presented with hemorrhagic vesicles mimicking vasculitic lesions, which had persisted over a 3-month period with intermittent localized pain. It has been proposed that in atypical presentations, the reactivated VZV spreads transaxonally from adjacent nerves to the outermost adventitial layer of the arterial wall, leading to a vasculitic appearance of the vesicles.6 Viral-induced vasculitis may also result either directly from infection of the blood vessels or secondary to vascular damage from an inflammatory immune complex–mediated reaction, cell-mediated hypersensitivity, or inflammation due to immune dysregulation.7,8

Continue to: Differential includes vesiculobullous conditions

Differential includes vesiculobullous conditions

There are several important items to consider in the differential.

Cutaneous vasculitis, in severe cases, may manifest with vesicles or bullae that resemble the lesions seen in HZ. However, its unilateral nature and distribution distinguish it.

Angioinvasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients may manifest with scattered ulceronecrotic lesions to purpuric vesiculobullous dermatoses.9 However, no fungal organisms were seen on GMS staining of the biopsied tissue.

Atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease tends to affect adults and is associated with Coxsackievirus A6 infection.10 It may manifest as generalized vesiculobullous exanthem resembling varicella. The chronic nature and restricted extent of the patient’s rash made this diagnosis unlikely.

Successful management depends on timely identification

Although most cases of HZ can be diagnosed clinically, atypical rashes may require a biopsy and direct immunofluorescence assay for VZV antigen or a polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assay for VZV DNA in cells from the base of blisters. Therefore, it is important to consider the diagnosis of HZ in immunocompromised patients presenting with an atypical rash to avoid misdiagnosis and costly testing.

Continue to: Our patient was treated...

Our patient was treated with oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times/day for 10 days, with prompt resolution of her rash.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joel Hua-Liang Lim, MBBS, MRCP, MMed, 1 Mandalay Road, Singapore 308205; [email protected]

A 52-year-old Chinese woman presented to a tertiary hospital in Singapore with a 3-month history of persistent and intermittently painful rashes over her right calf and foot (FIGURE). The patient had pancytopenia due to ongoing chemotherapy for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. She was systemically well and denied other dermatoses. Examination demonstrated scattered crops of tense hemorrhagic vesicles, each surrounded by a livid purpuric base, over the right plantar aspect of the foot, with areas of eschar over the right medial hallux. No allodynia, hyperaesthesia, or lymphadenopathy was noted.

A punch biopsy of an intact vesicle was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis:

Herpes zoster

Histopathologic examination showed full-thickness epidermal necrosis with ballooning degeneration resulting in an intra-epidermal blister. Multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear moulding were seen within the blister cavity. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (GMS), acid-fast, and Gram stains were negative. Granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgM, and C3 were seen intramurally. DNA analysis of vesicular fluid was positive for varicella zoster virus (VZV). A diagnosis of herpes zoster (HZ) of the right S1 dermatome with primary obliterative vasculitis was established.

Immunocompromised people—those who have impaired T-cell immunity (eg, recipients of organ or hematopoietic stem-cell transplants), take immunosuppressive therapy, or have lymphoma, leukemia, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection—have an increased risk for HZ. For example, in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), HZ uniquely manifests as recurrent shingles. An estimated 20% to 30% of HIV-infected patients will have more than 1 episode of HZ, which may involve the same or different dermatomes.1,2 Furthermore, HZ in this population is more commonly associated with atypical presentations.3

What an atypical presentation may look like

In immunocompromised patients, HZ may present with atypical cutaneous manifestations or with atypical generalized symptoms.

Atypical cutaneous manifestations, as in disseminated zoster, manifest with multiple hyperkeratotic papules (3-20 mm in diameter) that follow no dermatomal pattern. These lesions may be chronic, persisting for months or years, and may be associated with acyclovir-resistant strains of VZV.2,3 Another dermatologic variant is ecthymatous VZV, which manifests with multiple large (10-30 mm) punched-out ulcerations with a central black eschar and a peripheral rim of vesicles.4 Viral folliculitis—in which infection is limited to the hair follicle, with no associated blisters—has also been reported in atypical HZ.5

Our patient presented with hemorrhagic vesicles mimicking vasculitic lesions, which had persisted over a 3-month period with intermittent localized pain. It has been proposed that in atypical presentations, the reactivated VZV spreads transaxonally from adjacent nerves to the outermost adventitial layer of the arterial wall, leading to a vasculitic appearance of the vesicles.6 Viral-induced vasculitis may also result either directly from infection of the blood vessels or secondary to vascular damage from an inflammatory immune complex–mediated reaction, cell-mediated hypersensitivity, or inflammation due to immune dysregulation.7,8

Continue to: Differential includes vesiculobullous conditions

Differential includes vesiculobullous conditions

There are several important items to consider in the differential.

Cutaneous vasculitis, in severe cases, may manifest with vesicles or bullae that resemble the lesions seen in HZ. However, its unilateral nature and distribution distinguish it.

Angioinvasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients may manifest with scattered ulceronecrotic lesions to purpuric vesiculobullous dermatoses.9 However, no fungal organisms were seen on GMS staining of the biopsied tissue.

Atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease tends to affect adults and is associated with Coxsackievirus A6 infection.10 It may manifest as generalized vesiculobullous exanthem resembling varicella. The chronic nature and restricted extent of the patient’s rash made this diagnosis unlikely.

Successful management depends on timely identification

Although most cases of HZ can be diagnosed clinically, atypical rashes may require a biopsy and direct immunofluorescence assay for VZV antigen or a polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assay for VZV DNA in cells from the base of blisters. Therefore, it is important to consider the diagnosis of HZ in immunocompromised patients presenting with an atypical rash to avoid misdiagnosis and costly testing.

Continue to: Our patient was treated...

Our patient was treated with oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times/day for 10 days, with prompt resolution of her rash.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joel Hua-Liang Lim, MBBS, MRCP, MMed, 1 Mandalay Road, Singapore 308205; [email protected]

1. LeBoit PE, Limova M, Yen TS, et al. Chronic verrucous varicella-zoster virus infection in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): histologic and molecular biologic findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:1-7.

2. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

3. Weinberg JM, Mysliwiec A, Turiansky GW, et al. Viral folliculitis: atypical presentations of herpes simplex, herpes zoster, and molluscum contagiosum. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:983-986.

4. Gilson IH, Barnett JH, Conant MA, et al. Disseminated ecthymatous herpes varicella zoster virus infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:637-642.

5. Løkke BJ, Weismann K, Mathiesen L, et al. Atypical varicella-zoster infection in AIDS. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:123-125.

6. Uhoda I, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Varicella-zoster virus vasculitis: a case of recurrent varicella without epidermal involvement. Dermatology. 2000;200:173-175.

7. Teng GG, Chatham WW. Vasculitis related to viral and other microbial agents. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:226-243.

8. Nagel MA, Gilden D. Developments in varicella zoster virus vasculopathy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:12.

9. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2010;36:1-53.

10. Lott JP, Liu K, Landry M-L, et al. Atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:736-741.

1. LeBoit PE, Limova M, Yen TS, et al. Chronic verrucous varicella-zoster virus infection in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): histologic and molecular biologic findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:1-7.

2. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

3. Weinberg JM, Mysliwiec A, Turiansky GW, et al. Viral folliculitis: atypical presentations of herpes simplex, herpes zoster, and molluscum contagiosum. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:983-986.

4. Gilson IH, Barnett JH, Conant MA, et al. Disseminated ecthymatous herpes varicella zoster virus infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:637-642.

5. Løkke BJ, Weismann K, Mathiesen L, et al. Atypical varicella-zoster infection in AIDS. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:123-125.

6. Uhoda I, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Varicella-zoster virus vasculitis: a case of recurrent varicella without epidermal involvement. Dermatology. 2000;200:173-175.

7. Teng GG, Chatham WW. Vasculitis related to viral and other microbial agents. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:226-243.

8. Nagel MA, Gilden D. Developments in varicella zoster virus vasculopathy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:12.

9. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2010;36:1-53.

10. Lott JP, Liu K, Landry M-L, et al. Atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:736-741.

Painful ulcers on gingiva, tongue, and buccal mucosa

A 29-year-old man with no prior history of mouth sores abruptly developed many 1- to 1.5-mm blisters on the gingiva (FIGURE 1A),tongue (FIGURE 1B), and buccal mucosa (FIGURE 1C), which evolved into small erosions accompanied by a low-grade fever 5 days prior to presentation. The patient had no history of any dermatologic conditions or systemic illnesses and was taking no medication.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute primary herpetic gingivostomatitis

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the causative agent for acute primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.1 HSV-1 is primarily responsible for oral mucosal infections, while HSV-2 is implicated in most genital and cutaneous lower body lesions.1 Herpetic gingivostomatitis often presents as a sudden vesiculoulcerative eruption anywhere in the mouth, including the perioral skin, vermillion border, gingiva, tongue, or buccal mucosa.2 Associated symptoms include malaise, headache, fever, and cervical lymphadenopathy; however, most occurrences are subclinical or asymptomatic.2

A diagnosis that’s more common in children. Primary HSV occurs in people who have not previously been exposed to the virus. While it is an infection that classically presents in childhood, it is not limited to this group. Manifestations often are more severe in adults.1

Following an incubation period of a few days to 3 weeks, the primary infection typically lasts 10 to 14 days.1,2 Recurrence is highly variable and generally less severe than primary infection, with grouped vesicles often recurring in the same spot with each recurrence on the vermillion border of the lip. Triggers for reactivation include immunosuppression, pregnancy, fever, UV radiation, or trauma.1,2

Differential includes other conditions with mucosal lesions

Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis must be distinguished from other disease processes that cause ulcerative mucosal lesions.

Aphthous stomatitis (canker sores) is the most common ulcerative disease of the oral mucosa.3 It presents as painful, punched-out, shallow ulcers with a yellowish gray pseudomembranous center and surrounding erythema.3 No definitive etiology has been established; however, aphthae often occur after trauma.

Continue to: Herpangina...

Herpangina is caused by coxsackie A virus and primarily is seen in infants and children younger than 5.4 The papulovesicular lesions primarily affect the posterior oral cavity, including the soft palate, anterior tonsillar pillars, and uvula.4

Allergic contact dermatitis is precipitated by contact with an allergen and presents with pain or pruritus. Lesions are erythematous with vesicles, erosions, ulcers, or hyperkeratosis that gradually resolve after withdrawal of the causative allergen.5

Pemphigus vulgaris. Oral ulcerations of the buccal mucosa and gingiva are the first manifestation of pemphigus vulgaris in the majority of patients, with skin blisters occurring months to years later over areas exposed to frictional stress.6 Skin sloughs may be seen in response to frictional stress (Nikolsky sign).6

The new Dx gold standard is PCR

Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis usually is diagnosed by history and hallmark clinical signs and symptoms.1 In this case, our patient presented with a sudden eruption of painful blisters on multiple areas of the oral mucosa associated with fever. The diagnosis can be confirmed by viral culture, serology with anti-HSV IgM and IgG, Tzanck preparation, immunofluorescence, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).1 Viral culture has been the gold standard for mucosal HSV diagnosis; however, PCR is emerging as the new gold standard because of its unrivaled sensitivity, specificity, and rapid turnaround time.7,8 Specimens for PCR are submitted using a swab of infected cells placed in the same viral transport medium used for HSV cultures.

Our patient’s culture was positive for HSV-1.

Continue to: Prompt use of antivirals is key

Prompt use of antivirals is key

Treatment of acute HSV gingivostomatitis involves symptomatic management with topical anesthetics, oral analgesics, and normal saline rinses.1 Acyclovir is an established therapy; however, it has poor bioavailability and gastrointestinal absorption.1 Valacyclovir has improved bioavailability and is well tolerated.1 For primary herpes gingivostomatitis, we favor 1 g twice daily for 7 days.1 Our patient responded well to this valacyclovir regimen and healed completely in 1 week.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, 2500 N State St, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Ajar AH, Chauvin PJ. Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis in adults: a review of 13 cases, including diagnosis and management. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:247-251.

2. George AK, Anil S. Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis associated with herpes simplex virus 2: report of a case. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6:99-102.

3. Akintoye SO, Greenburg MS. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Dent Clin N Am. 2014;58:281-297.

4. Scott LA, Stone MS. Viral exanthems. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:4.

5. Feller L, Wood NH, Khammissa RA, et al. Review: allergic contact stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017;123:559-565.

6. Bascones-Martinez A, Munoz-Corcuera M, Bascones-Ilundain C, et al. Oral manifestations of pemphigus vulgaris: clinical presentation, differential diagnosis and management. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2010;1:112.

7. LeGoff J, Péré H, Bélec L. Diagnosis of genital herpes simplex virus infection in the clinical laboratory. Virol J. 2014;11:83.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HSV infections. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/herpes.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed September 26, 2019.