User login

Sores on left arm

The FP noted that a pattern seemed to start on the patient’s second finger and spread up his arm. He considered that this skin disease might be secondary to sporotrichosis (a deep fungal infection, also referred to as rose gardener’s disease).

Sporotrichosis typically spreads up the arm from an inoculation of the hand from a scratch of a rose thorn. The ulcers partially resemble pyoderma gangrenosum, but the edges are neither undermined nor the color of gun metal. While sporotrichosis may be spread to humans through injuries while working with rose bushes, many other plants and animals can carry the organism Sporothrix schenckii.

The FP decided to offer a definitive diagnosis with a fungal culture since sporotrichosis treatment would require months of an oral antifungal agent. Obtaining a fungal culture would require a punch biopsy because the Sporothrix schenckii grows deeply in the tissue and is not reliably found on the skin surface. The mother and patient consented to the procedure and the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on the edge of the largest ulcer on the arm. The specimen was placed in a sterile urine culture cup on sterile gauze with some saline (preservative free). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

It is important to note that that if the specimen had been sent in standard formalin, a culture could not be performed and histology could miss the dead organism. Clinical suspicion for sporotrichosis was so high in this case that the FP prescribed oral itraconazole 200 mg daily for the next 2 weeks while awaiting the fungal culture result.

The fungal culture grew out Sporothrix schenckii. The FP prescribed itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months and planned to continue the therapy until at least 2 to 4 weeks after the lesions had healed. With monthly follow-up visits, the itraconazole treatment lasted 5 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted that a pattern seemed to start on the patient’s second finger and spread up his arm. He considered that this skin disease might be secondary to sporotrichosis (a deep fungal infection, also referred to as rose gardener’s disease).

Sporotrichosis typically spreads up the arm from an inoculation of the hand from a scratch of a rose thorn. The ulcers partially resemble pyoderma gangrenosum, but the edges are neither undermined nor the color of gun metal. While sporotrichosis may be spread to humans through injuries while working with rose bushes, many other plants and animals can carry the organism Sporothrix schenckii.

The FP decided to offer a definitive diagnosis with a fungal culture since sporotrichosis treatment would require months of an oral antifungal agent. Obtaining a fungal culture would require a punch biopsy because the Sporothrix schenckii grows deeply in the tissue and is not reliably found on the skin surface. The mother and patient consented to the procedure and the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on the edge of the largest ulcer on the arm. The specimen was placed in a sterile urine culture cup on sterile gauze with some saline (preservative free). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

It is important to note that that if the specimen had been sent in standard formalin, a culture could not be performed and histology could miss the dead organism. Clinical suspicion for sporotrichosis was so high in this case that the FP prescribed oral itraconazole 200 mg daily for the next 2 weeks while awaiting the fungal culture result.

The fungal culture grew out Sporothrix schenckii. The FP prescribed itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months and planned to continue the therapy until at least 2 to 4 weeks after the lesions had healed. With monthly follow-up visits, the itraconazole treatment lasted 5 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted that a pattern seemed to start on the patient’s second finger and spread up his arm. He considered that this skin disease might be secondary to sporotrichosis (a deep fungal infection, also referred to as rose gardener’s disease).

Sporotrichosis typically spreads up the arm from an inoculation of the hand from a scratch of a rose thorn. The ulcers partially resemble pyoderma gangrenosum, but the edges are neither undermined nor the color of gun metal. While sporotrichosis may be spread to humans through injuries while working with rose bushes, many other plants and animals can carry the organism Sporothrix schenckii.

The FP decided to offer a definitive diagnosis with a fungal culture since sporotrichosis treatment would require months of an oral antifungal agent. Obtaining a fungal culture would require a punch biopsy because the Sporothrix schenckii grows deeply in the tissue and is not reliably found on the skin surface. The mother and patient consented to the procedure and the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on the edge of the largest ulcer on the arm. The specimen was placed in a sterile urine culture cup on sterile gauze with some saline (preservative free). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

It is important to note that that if the specimen had been sent in standard formalin, a culture could not be performed and histology could miss the dead organism. Clinical suspicion for sporotrichosis was so high in this case that the FP prescribed oral itraconazole 200 mg daily for the next 2 weeks while awaiting the fungal culture result.

The fungal culture grew out Sporothrix schenckii. The FP prescribed itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months and planned to continue the therapy until at least 2 to 4 weeks after the lesions had healed. With monthly follow-up visits, the itraconazole treatment lasted 5 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Multiple skin ulcers

The FP noted the deep ulcers with gun-metal (violet blue coloration) undermined borders. The edge of the upper left corner of the suprapubic ulcer also had a cribriform pattern (pierced with holes like swiss cheese). The FP’s differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) and a deep fungal infection.

The FP was aware that it could take months before the patient could be seen be a dermatologist, so he offered to perform a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of the ulcer. (Note that the correct location for a biopsy of an ulcer is on the edge, not in the middle). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathologist found a dense neutrophilic infiltrate and stated that this supported the diagnosis of PG. No fungal elements were seen with a Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain. PG is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis, without a known cause, that is sometimes seen with inflammatory bowel disease.

The FP called a local dermatologist, and they decided to start the patient on oral prednisone until she could be seen in the dermatologist’s office. The dermatologist stated that she would be considering oral cyclosporine, oral dapsone, or injectable biologic agents as steroid sparing agents to treat the PG.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted the deep ulcers with gun-metal (violet blue coloration) undermined borders. The edge of the upper left corner of the suprapubic ulcer also had a cribriform pattern (pierced with holes like swiss cheese). The FP’s differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) and a deep fungal infection.

The FP was aware that it could take months before the patient could be seen be a dermatologist, so he offered to perform a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of the ulcer. (Note that the correct location for a biopsy of an ulcer is on the edge, not in the middle). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathologist found a dense neutrophilic infiltrate and stated that this supported the diagnosis of PG. No fungal elements were seen with a Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain. PG is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis, without a known cause, that is sometimes seen with inflammatory bowel disease.

The FP called a local dermatologist, and they decided to start the patient on oral prednisone until she could be seen in the dermatologist’s office. The dermatologist stated that she would be considering oral cyclosporine, oral dapsone, or injectable biologic agents as steroid sparing agents to treat the PG.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted the deep ulcers with gun-metal (violet blue coloration) undermined borders. The edge of the upper left corner of the suprapubic ulcer also had a cribriform pattern (pierced with holes like swiss cheese). The FP’s differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) and a deep fungal infection.

The FP was aware that it could take months before the patient could be seen be a dermatologist, so he offered to perform a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of the ulcer. (Note that the correct location for a biopsy of an ulcer is on the edge, not in the middle). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathologist found a dense neutrophilic infiltrate and stated that this supported the diagnosis of PG. No fungal elements were seen with a Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain. PG is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis, without a known cause, that is sometimes seen with inflammatory bowel disease.

The FP called a local dermatologist, and they decided to start the patient on oral prednisone until she could be seen in the dermatologist’s office. The dermatologist stated that she would be considering oral cyclosporine, oral dapsone, or injectable biologic agents as steroid sparing agents to treat the PG.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful ulcers on forehead

Based on the areas of necrosis, the FP suspected that a brown recluse spider bite caused the lesions. He suspected that the whole area of swelling and erythema was the bite reaction, and the 3 ulcerated areas were the regions of necrosis (often there is only 1 central area). The FP considered cellulitis as part of the differential diagnosis and debated whether to prescribe an antibiotic.

While the patient and FP believed that the most likely diagnosis was a spider bite, they were not completely certain of this diagnosis because the patient never saw the spider. Therefore, the patient requested an antibiotic in case this was a bacterial infection. A bacterial culture of the ulcer was performed and the patient was given a 5-day course of oral cephalexin 500 mg 4 times a day.

The FP recommended over-the-counter oral diphenhydramine to be taken around the clock as tolerated along with ibuprofen at mealtimes. The FP kept in contact with the patient by phone and improvement was noted daily. The bacterial culture came back negative, and the lesions all healed with time.

Spider bites can be difficult to diagnose as many lesions are blamed on spiders without evidence of a bite or spider. Conversely, spider bites may be missed as the spider is not typically available for easy identification. To this day, the FP and patient believe these lesions were the work of a brown recluse spider.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the areas of necrosis, the FP suspected that a brown recluse spider bite caused the lesions. He suspected that the whole area of swelling and erythema was the bite reaction, and the 3 ulcerated areas were the regions of necrosis (often there is only 1 central area). The FP considered cellulitis as part of the differential diagnosis and debated whether to prescribe an antibiotic.

While the patient and FP believed that the most likely diagnosis was a spider bite, they were not completely certain of this diagnosis because the patient never saw the spider. Therefore, the patient requested an antibiotic in case this was a bacterial infection. A bacterial culture of the ulcer was performed and the patient was given a 5-day course of oral cephalexin 500 mg 4 times a day.

The FP recommended over-the-counter oral diphenhydramine to be taken around the clock as tolerated along with ibuprofen at mealtimes. The FP kept in contact with the patient by phone and improvement was noted daily. The bacterial culture came back negative, and the lesions all healed with time.

Spider bites can be difficult to diagnose as many lesions are blamed on spiders without evidence of a bite or spider. Conversely, spider bites may be missed as the spider is not typically available for easy identification. To this day, the FP and patient believe these lesions were the work of a brown recluse spider.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the areas of necrosis, the FP suspected that a brown recluse spider bite caused the lesions. He suspected that the whole area of swelling and erythema was the bite reaction, and the 3 ulcerated areas were the regions of necrosis (often there is only 1 central area). The FP considered cellulitis as part of the differential diagnosis and debated whether to prescribe an antibiotic.

While the patient and FP believed that the most likely diagnosis was a spider bite, they were not completely certain of this diagnosis because the patient never saw the spider. Therefore, the patient requested an antibiotic in case this was a bacterial infection. A bacterial culture of the ulcer was performed and the patient was given a 5-day course of oral cephalexin 500 mg 4 times a day.

The FP recommended over-the-counter oral diphenhydramine to be taken around the clock as tolerated along with ibuprofen at mealtimes. The FP kept in contact with the patient by phone and improvement was noted daily. The bacterial culture came back negative, and the lesions all healed with time.

Spider bites can be difficult to diagnose as many lesions are blamed on spiders without evidence of a bite or spider. Conversely, spider bites may be missed as the spider is not typically available for easy identification. To this day, the FP and patient believe these lesions were the work of a brown recluse spider.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

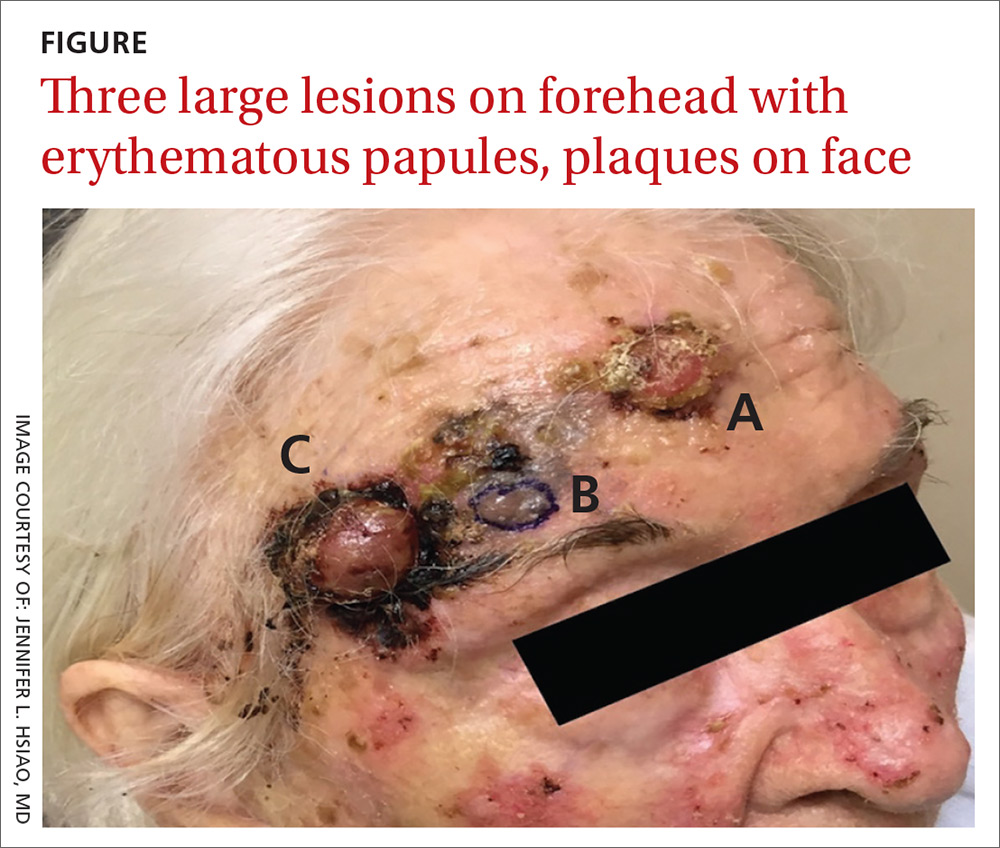

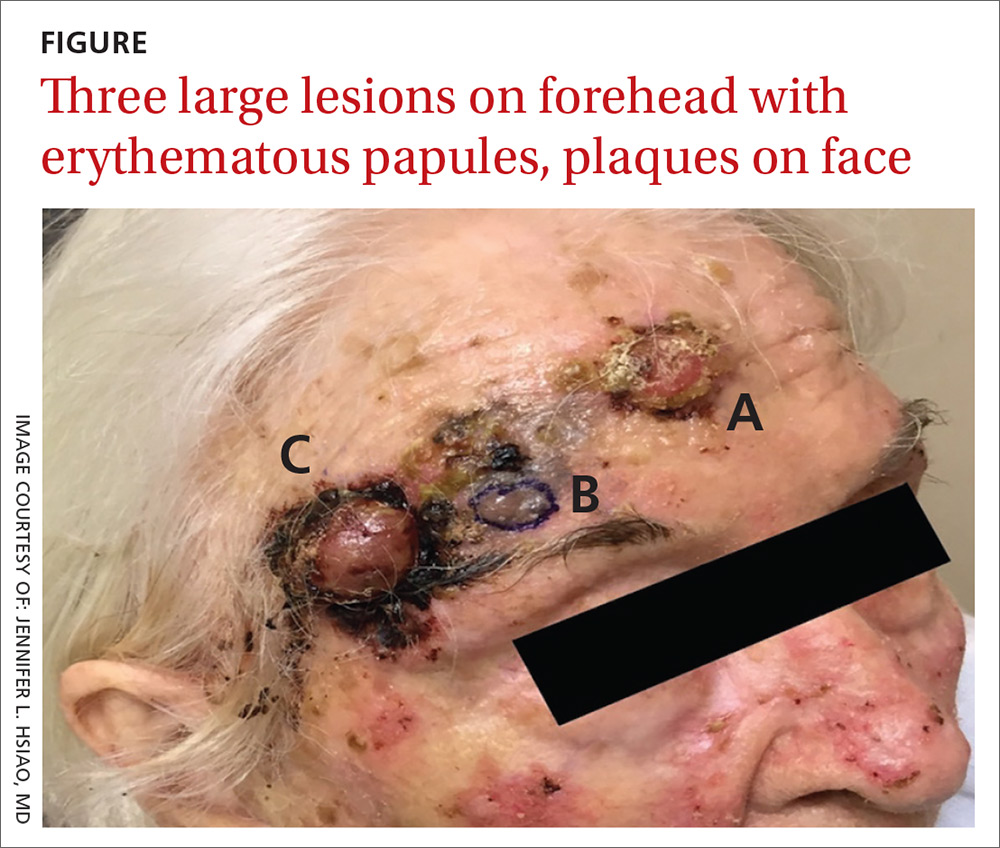

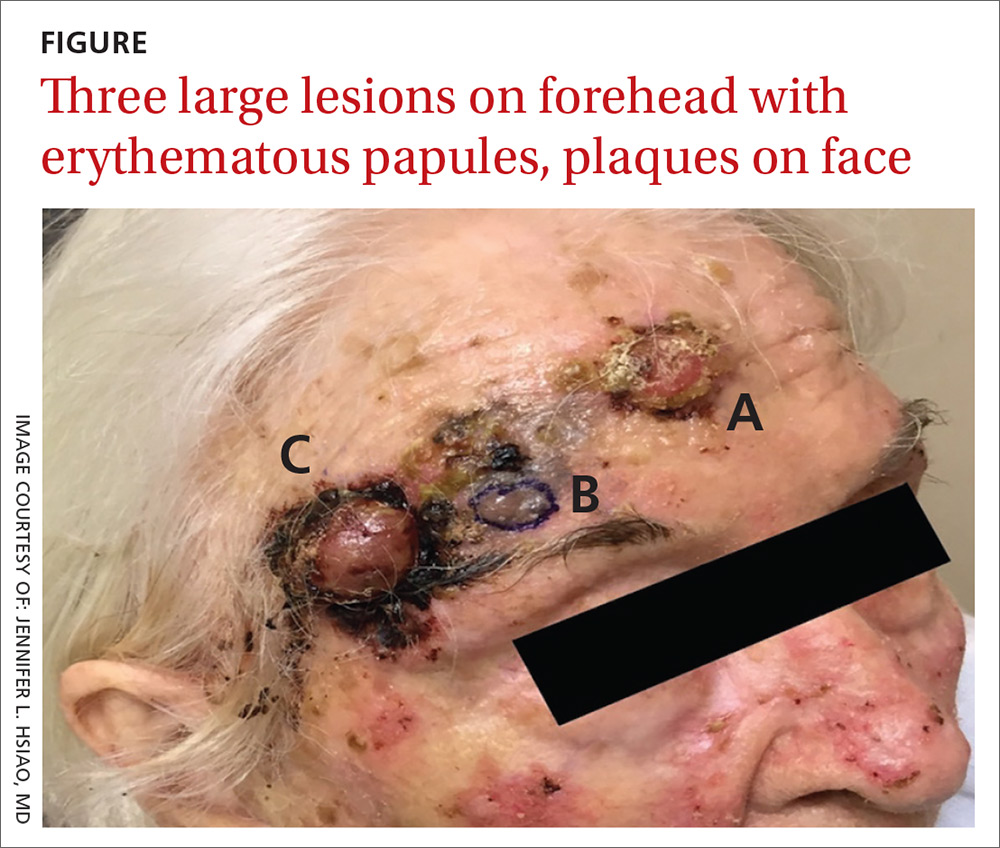

Rapidly growing lesions on the forehead

A 97-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented to our clinic from an assisted living facility with a several-month history of rapidly growing forehead lesions. She denied symptoms, other than some bleeding and crusting, but was concerned about their appearance. She reported a notable history of sun exposure.

The patient had 3 confluent, but distinct, lesions on her forehead: an erythematous crateriform nodule with overlying hyperkeratotic scale (FIGURE, Lesion A); a nodular hyperpigmented plaque with irregular color and borders (Lesion B); and a pearly well-vascularized erythematous nodule with surrounding hemorrhagic crust (Lesion C).

She also had scattered, thin, gritty pink papules and plaques on the face that were thought to be actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers based on clinical morphology; however, the patient deferred workup and treatment of these lesions to focus on the forehead lesions. The decision was made to biopsy all 3 clinical morphologies seen. The risks and benefits of biopsy were reviewed with the patient and her daughter, and they opted to proceed. The areas were anesthetized with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000; 3 shave biopsies were performed. Hemostasis was obtained with electrodesiccation.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Skin cancer

A histopathology report revealed that Lesion A was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), Lesion B was a melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 1.2 mm, and Lesion C was basal cell carcinoma (BCC). It is unusual to have a patient present with BCC, SCC, and melanoma concurrently in the same anatomic region.

Two of the lesions were nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC). BCC is the most common NMSC in the United States, affecting more than 3.3 million people per year.1 Although there are several subtypes of BCC with varying clinical presentations, the most classic appearance is a pearly papule with or without surface telangiectasias.2

SCC has an incidence of 200,000 to 400,000 cases per year in the United States and the lifetime risk is 9% to 14% in men and 4% to 9% in women.3 SCC most commonly presents as a hyperkeratotic papule or plaque.2 Lesions suspicious for SCC and BCC should be biopsied and the diagnosis confirmed by histopathologic analysis. These NMSCs are locally destructive, but rarely metastatic with a generally good prognosis. The standard treatment for both is surgical excision with consideration for other treatment modalities, such as topical therapies, chemotherapy, and radiation, depending on tumor characteristics as well as whether the patient is a good surgical candidate.1,3

Melanoma is rising in incidence each year, with nearly 100,000 new cases expected in the United States this year.4 It is the leading cause of skin cancer related mortality.5 The most common suspicious lesions are variably pigmented macules with irregular borders. Biopsy and subsequent histopathologic analysis will confirm the diagnosis.

When a lesion is clinically suspicious for melanoma, it is particularly important to consider an excisional biopsy to allow for proper staging.5 Examples of appropriate excisional biopsies include elliptical excisions, punch biopsies, and deep shave biopsies.5 Definitive treatment involves a wider and deeper excision with histologically confirmed clear margins.5

Continue to: This case required a multidisciplinary team

This case required a multidisciplinary team

The patient was cleared for surgery; however, after the patient held her warfarin in preparation for the resection, she suffered a left frontal operculum infarction. At this point, she was re-evaluated by her head and neck physician, cardiologist, and anesthesiologist. Consensus was reached that the patient was at high perioperative risk for morbidity and mortality, and surgical intervention was no longer considered a viable option.

The patient then opted for palliative radiation therapy to all 3 lesions, with the understanding that the local control offered by radiotherapy would be inferior to what resection would provide for the melanoma lesion. Although not curative, radiotherapy was expected to provide local symptom relief for the melanoma, consistent with the patient’s palliative goals of care. In the past, melanoma was thought to be resistant to radiation, but recent evidence suggests that it may be at least partially susceptible to hypofractionated courses of radiation.6

Radiation oncology recommended a 6 to 15 fraction regimen and she had a good clinical response with > 50% decrease in the size of all 3 lesions along with cessation of bleeding.

The take-home lesson. The findings in this case serve as an important reminder to biopsy lesions with varying morphologies—even when they are in close proximity to one another. Foregoing any of the biopsies in this case would have led to a missed diagnosis, which has implications for optimal management and treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, 2020 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 510, Santa Monica, CA 90404; [email protected]

1. Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:540-559.

2. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

3. Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:560-578.

4. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

5. Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:208-250.

6. Vuong W, Lin J, Wei RL. Palliative radiotherapy for skin malignancies. Ann Palliat Med. 2017;6:165-172.

A 97-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented to our clinic from an assisted living facility with a several-month history of rapidly growing forehead lesions. She denied symptoms, other than some bleeding and crusting, but was concerned about their appearance. She reported a notable history of sun exposure.

The patient had 3 confluent, but distinct, lesions on her forehead: an erythematous crateriform nodule with overlying hyperkeratotic scale (FIGURE, Lesion A); a nodular hyperpigmented plaque with irregular color and borders (Lesion B); and a pearly well-vascularized erythematous nodule with surrounding hemorrhagic crust (Lesion C).

She also had scattered, thin, gritty pink papules and plaques on the face that were thought to be actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers based on clinical morphology; however, the patient deferred workup and treatment of these lesions to focus on the forehead lesions. The decision was made to biopsy all 3 clinical morphologies seen. The risks and benefits of biopsy were reviewed with the patient and her daughter, and they opted to proceed. The areas were anesthetized with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000; 3 shave biopsies were performed. Hemostasis was obtained with electrodesiccation.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Skin cancer

A histopathology report revealed that Lesion A was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), Lesion B was a melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 1.2 mm, and Lesion C was basal cell carcinoma (BCC). It is unusual to have a patient present with BCC, SCC, and melanoma concurrently in the same anatomic region.

Two of the lesions were nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC). BCC is the most common NMSC in the United States, affecting more than 3.3 million people per year.1 Although there are several subtypes of BCC with varying clinical presentations, the most classic appearance is a pearly papule with or without surface telangiectasias.2

SCC has an incidence of 200,000 to 400,000 cases per year in the United States and the lifetime risk is 9% to 14% in men and 4% to 9% in women.3 SCC most commonly presents as a hyperkeratotic papule or plaque.2 Lesions suspicious for SCC and BCC should be biopsied and the diagnosis confirmed by histopathologic analysis. These NMSCs are locally destructive, but rarely metastatic with a generally good prognosis. The standard treatment for both is surgical excision with consideration for other treatment modalities, such as topical therapies, chemotherapy, and radiation, depending on tumor characteristics as well as whether the patient is a good surgical candidate.1,3

Melanoma is rising in incidence each year, with nearly 100,000 new cases expected in the United States this year.4 It is the leading cause of skin cancer related mortality.5 The most common suspicious lesions are variably pigmented macules with irregular borders. Biopsy and subsequent histopathologic analysis will confirm the diagnosis.

When a lesion is clinically suspicious for melanoma, it is particularly important to consider an excisional biopsy to allow for proper staging.5 Examples of appropriate excisional biopsies include elliptical excisions, punch biopsies, and deep shave biopsies.5 Definitive treatment involves a wider and deeper excision with histologically confirmed clear margins.5

Continue to: This case required a multidisciplinary team

This case required a multidisciplinary team

The patient was cleared for surgery; however, after the patient held her warfarin in preparation for the resection, she suffered a left frontal operculum infarction. At this point, she was re-evaluated by her head and neck physician, cardiologist, and anesthesiologist. Consensus was reached that the patient was at high perioperative risk for morbidity and mortality, and surgical intervention was no longer considered a viable option.

The patient then opted for palliative radiation therapy to all 3 lesions, with the understanding that the local control offered by radiotherapy would be inferior to what resection would provide for the melanoma lesion. Although not curative, radiotherapy was expected to provide local symptom relief for the melanoma, consistent with the patient’s palliative goals of care. In the past, melanoma was thought to be resistant to radiation, but recent evidence suggests that it may be at least partially susceptible to hypofractionated courses of radiation.6

Radiation oncology recommended a 6 to 15 fraction regimen and she had a good clinical response with > 50% decrease in the size of all 3 lesions along with cessation of bleeding.

The take-home lesson. The findings in this case serve as an important reminder to biopsy lesions with varying morphologies—even when they are in close proximity to one another. Foregoing any of the biopsies in this case would have led to a missed diagnosis, which has implications for optimal management and treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, 2020 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 510, Santa Monica, CA 90404; [email protected]

A 97-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented to our clinic from an assisted living facility with a several-month history of rapidly growing forehead lesions. She denied symptoms, other than some bleeding and crusting, but was concerned about their appearance. She reported a notable history of sun exposure.

The patient had 3 confluent, but distinct, lesions on her forehead: an erythematous crateriform nodule with overlying hyperkeratotic scale (FIGURE, Lesion A); a nodular hyperpigmented plaque with irregular color and borders (Lesion B); and a pearly well-vascularized erythematous nodule with surrounding hemorrhagic crust (Lesion C).

She also had scattered, thin, gritty pink papules and plaques on the face that were thought to be actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers based on clinical morphology; however, the patient deferred workup and treatment of these lesions to focus on the forehead lesions. The decision was made to biopsy all 3 clinical morphologies seen. The risks and benefits of biopsy were reviewed with the patient and her daughter, and they opted to proceed. The areas were anesthetized with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000; 3 shave biopsies were performed. Hemostasis was obtained with electrodesiccation.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Skin cancer

A histopathology report revealed that Lesion A was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), Lesion B was a melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 1.2 mm, and Lesion C was basal cell carcinoma (BCC). It is unusual to have a patient present with BCC, SCC, and melanoma concurrently in the same anatomic region.

Two of the lesions were nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC). BCC is the most common NMSC in the United States, affecting more than 3.3 million people per year.1 Although there are several subtypes of BCC with varying clinical presentations, the most classic appearance is a pearly papule with or without surface telangiectasias.2

SCC has an incidence of 200,000 to 400,000 cases per year in the United States and the lifetime risk is 9% to 14% in men and 4% to 9% in women.3 SCC most commonly presents as a hyperkeratotic papule or plaque.2 Lesions suspicious for SCC and BCC should be biopsied and the diagnosis confirmed by histopathologic analysis. These NMSCs are locally destructive, but rarely metastatic with a generally good prognosis. The standard treatment for both is surgical excision with consideration for other treatment modalities, such as topical therapies, chemotherapy, and radiation, depending on tumor characteristics as well as whether the patient is a good surgical candidate.1,3

Melanoma is rising in incidence each year, with nearly 100,000 new cases expected in the United States this year.4 It is the leading cause of skin cancer related mortality.5 The most common suspicious lesions are variably pigmented macules with irregular borders. Biopsy and subsequent histopathologic analysis will confirm the diagnosis.

When a lesion is clinically suspicious for melanoma, it is particularly important to consider an excisional biopsy to allow for proper staging.5 Examples of appropriate excisional biopsies include elliptical excisions, punch biopsies, and deep shave biopsies.5 Definitive treatment involves a wider and deeper excision with histologically confirmed clear margins.5

Continue to: This case required a multidisciplinary team

This case required a multidisciplinary team

The patient was cleared for surgery; however, after the patient held her warfarin in preparation for the resection, she suffered a left frontal operculum infarction. At this point, she was re-evaluated by her head and neck physician, cardiologist, and anesthesiologist. Consensus was reached that the patient was at high perioperative risk for morbidity and mortality, and surgical intervention was no longer considered a viable option.

The patient then opted for palliative radiation therapy to all 3 lesions, with the understanding that the local control offered by radiotherapy would be inferior to what resection would provide for the melanoma lesion. Although not curative, radiotherapy was expected to provide local symptom relief for the melanoma, consistent with the patient’s palliative goals of care. In the past, melanoma was thought to be resistant to radiation, but recent evidence suggests that it may be at least partially susceptible to hypofractionated courses of radiation.6

Radiation oncology recommended a 6 to 15 fraction regimen and she had a good clinical response with > 50% decrease in the size of all 3 lesions along with cessation of bleeding.

The take-home lesson. The findings in this case serve as an important reminder to biopsy lesions with varying morphologies—even when they are in close proximity to one another. Foregoing any of the biopsies in this case would have led to a missed diagnosis, which has implications for optimal management and treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, 2020 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 510, Santa Monica, CA 90404; [email protected]

1. Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:540-559.

2. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

3. Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:560-578.

4. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

5. Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:208-250.

6. Vuong W, Lin J, Wei RL. Palliative radiotherapy for skin malignancies. Ann Palliat Med. 2017;6:165-172.

1. Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:540-559.

2. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

3. Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:560-578.

4. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

5. Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:208-250.

6. Vuong W, Lin J, Wei RL. Palliative radiotherapy for skin malignancies. Ann Palliat Med. 2017;6:165-172.

Ulcers on lower leg

The FP recognized this as classic pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)—a challenging condition to treat and not within the typical scope of practice for an FP. Nonhealing, well-defined leg ulcers in a person with Crohn's disease (or any type of inflammatory bowel disease) are often seen with PG. Pathergy—the development of an exaggerated injury following minor trauma—is known to occur with PG.

The FP also noted the violet-blue coloration around the borders of the ulcers, which is referred to as a “gun-metal border.” He considered doing a biopsy on the edge of the ulcer to rule out other conditions and to see if there was a neutrophilic infiltrate that is typically seen with PG. However, the FP realized that pathergy could be stimulated by a biopsy, so he decided to refer the patient to Dermatology.

Knowing that the patient might have to wait a few months to see a dermatologist, the FP consulted online sources and prescribed topical clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily as an initial therapy. This was not successful, so after a phone consult with the dermatologist, the FP added oral prednisone 40 mg/d for the next 2 weeks until the dermatologist could see the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as classic pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)—a challenging condition to treat and not within the typical scope of practice for an FP. Nonhealing, well-defined leg ulcers in a person with Crohn's disease (or any type of inflammatory bowel disease) are often seen with PG. Pathergy—the development of an exaggerated injury following minor trauma—is known to occur with PG.

The FP also noted the violet-blue coloration around the borders of the ulcers, which is referred to as a “gun-metal border.” He considered doing a biopsy on the edge of the ulcer to rule out other conditions and to see if there was a neutrophilic infiltrate that is typically seen with PG. However, the FP realized that pathergy could be stimulated by a biopsy, so he decided to refer the patient to Dermatology.

Knowing that the patient might have to wait a few months to see a dermatologist, the FP consulted online sources and prescribed topical clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily as an initial therapy. This was not successful, so after a phone consult with the dermatologist, the FP added oral prednisone 40 mg/d for the next 2 weeks until the dermatologist could see the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as classic pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)—a challenging condition to treat and not within the typical scope of practice for an FP. Nonhealing, well-defined leg ulcers in a person with Crohn's disease (or any type of inflammatory bowel disease) are often seen with PG. Pathergy—the development of an exaggerated injury following minor trauma—is known to occur with PG.

The FP also noted the violet-blue coloration around the borders of the ulcers, which is referred to as a “gun-metal border.” He considered doing a biopsy on the edge of the ulcer to rule out other conditions and to see if there was a neutrophilic infiltrate that is typically seen with PG. However, the FP realized that pathergy could be stimulated by a biopsy, so he decided to refer the patient to Dermatology.

Knowing that the patient might have to wait a few months to see a dermatologist, the FP consulted online sources and prescribed topical clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily as an initial therapy. This was not successful, so after a phone consult with the dermatologist, the FP added oral prednisone 40 mg/d for the next 2 weeks until the dermatologist could see the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Generalized rash following ankle ulceration

At the hospital, the physicians noted that there were no lesions on the mucous membranes of the patient’s eyes, ears, nose, mouth or anus and his vital signs were within normal limits. He was empirically treated with 1 dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. During the previous episode, he said the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin. Based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the history of similar lesions that appeared following previous treatment with TMP-SMX, the physician diagnosed disseminated fixed-drug eruption in this patient.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with this patient). The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.

This diagnosis usually is made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. A skin biopsy may be performed to confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise.

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches.

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like this patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days.

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption. He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

This case was adapted from: Bucher J, Rahnama-Moghadam S, Osswald S. Generalized rash follows ankle ulceration. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:489-491.

At the hospital, the physicians noted that there were no lesions on the mucous membranes of the patient’s eyes, ears, nose, mouth or anus and his vital signs were within normal limits. He was empirically treated with 1 dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. During the previous episode, he said the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin. Based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the history of similar lesions that appeared following previous treatment with TMP-SMX, the physician diagnosed disseminated fixed-drug eruption in this patient.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with this patient). The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.

This diagnosis usually is made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. A skin biopsy may be performed to confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise.

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches.

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like this patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days.

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption. He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

This case was adapted from: Bucher J, Rahnama-Moghadam S, Osswald S. Generalized rash follows ankle ulceration. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:489-491.

At the hospital, the physicians noted that there were no lesions on the mucous membranes of the patient’s eyes, ears, nose, mouth or anus and his vital signs were within normal limits. He was empirically treated with 1 dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. During the previous episode, he said the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin. Based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the history of similar lesions that appeared following previous treatment with TMP-SMX, the physician diagnosed disseminated fixed-drug eruption in this patient.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with this patient). The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.

This diagnosis usually is made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. A skin biopsy may be performed to confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise.

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches.

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like this patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days.

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption. He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

This case was adapted from: Bucher J, Rahnama-Moghadam S, Osswald S. Generalized rash follows ankle ulceration. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:489-491.

Geometric rash on arms and legs

The FP thought this looked like granuloma annulare (GA) but had never seen so many lesions on a patient. Some lesions were not round (more oval or elongated), while others were not completely enclosed geometric shapes (with breaks in the multiple ring patterns). However, all of the lesions were slightly raised with erythema and no scale. (The FP also considered tinea corporis, but ruled it out because there was no scale.)

He consulted some Internet resources and was convinced that this was disseminated GA. The greatest risk factor for this somewhat mysterious disease of unknown origin is female gender. It is also often associated with diabetes, but diabetes is not the cause.

Although intralesional steroids work when treating disseminated GA, this approach is not realistic for widespread disease. A number of options have been studied and reported in small series or case reports. The FP presented various options to the patient, and together they decided to try pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily for systemic treatment. Pentoxifylline is approved for claudication and has few adverse effects or risks. While this treatment is off-label for GA, there are no FDA approved treatments.

During a follow-up visit 1 month later, the number of lesions had been reduced by half. The FP continued treating the patient with pentoxifylline with the hope of achieving full resolution.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mauskar M, Usatine R. Granuloma annulare. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1141-1146.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP thought this looked like granuloma annulare (GA) but had never seen so many lesions on a patient. Some lesions were not round (more oval or elongated), while others were not completely enclosed geometric shapes (with breaks in the multiple ring patterns). However, all of the lesions were slightly raised with erythema and no scale. (The FP also considered tinea corporis, but ruled it out because there was no scale.)

He consulted some Internet resources and was convinced that this was disseminated GA. The greatest risk factor for this somewhat mysterious disease of unknown origin is female gender. It is also often associated with diabetes, but diabetes is not the cause.

Although intralesional steroids work when treating disseminated GA, this approach is not realistic for widespread disease. A number of options have been studied and reported in small series or case reports. The FP presented various options to the patient, and together they decided to try pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily for systemic treatment. Pentoxifylline is approved for claudication and has few adverse effects or risks. While this treatment is off-label for GA, there are no FDA approved treatments.

During a follow-up visit 1 month later, the number of lesions had been reduced by half. The FP continued treating the patient with pentoxifylline with the hope of achieving full resolution.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mauskar M, Usatine R. Granuloma annulare. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1141-1146.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP thought this looked like granuloma annulare (GA) but had never seen so many lesions on a patient. Some lesions were not round (more oval or elongated), while others were not completely enclosed geometric shapes (with breaks in the multiple ring patterns). However, all of the lesions were slightly raised with erythema and no scale. (The FP also considered tinea corporis, but ruled it out because there was no scale.)

He consulted some Internet resources and was convinced that this was disseminated GA. The greatest risk factor for this somewhat mysterious disease of unknown origin is female gender. It is also often associated with diabetes, but diabetes is not the cause.

Although intralesional steroids work when treating disseminated GA, this approach is not realistic for widespread disease. A number of options have been studied and reported in small series or case reports. The FP presented various options to the patient, and together they decided to try pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily for systemic treatment. Pentoxifylline is approved for claudication and has few adverse effects or risks. While this treatment is off-label for GA, there are no FDA approved treatments.

During a follow-up visit 1 month later, the number of lesions had been reduced by half. The FP continued treating the patient with pentoxifylline with the hope of achieving full resolution.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mauskar M, Usatine R. Granuloma annulare. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1141-1146.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Raised lesion on hand

The FP diagnosed granuloma annulare (GA) in this patient, based on the typical clinical appearance of a raised ring on the back of the hand with no scale.

GA is a common benign cutaneous, inflammatory disorder of unknown origin. It affects twice as many women as men. It features annular lesions that have raised borders and are skin-colored to erythematous. The rings may become hyperpigmented and often feature a central depression. These lesions are typically 1 to 5 cm wide. Although the classical appearance of GA is annular, the rings may not always be complete. Most importantly, there is no scaling, which one would expect to see in tinea infections, also known as “ringworm.”

The most common form of granuloma annulare is localized, as it was in this case. It typically presents on the dorsal surfaces of extremities, especially of the hands and feet. When the presentation is classic, there is no need for a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

The most effective treatment for local disease is intralesional triamcinolone (5mg/mL). (See Watch & Learn: Intralesional injections.) The FP offered this treatment to the patient, and she tolerated the procedure well. The GA resolved over the weeks that followed with some faint hypopigmentation that lasted for several months. The patient was happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mauskar M, Usatine R. Granuloma annulare. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1141-1146.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed granuloma annulare (GA) in this patient, based on the typical clinical appearance of a raised ring on the back of the hand with no scale.

GA is a common benign cutaneous, inflammatory disorder of unknown origin. It affects twice as many women as men. It features annular lesions that have raised borders and are skin-colored to erythematous. The rings may become hyperpigmented and often feature a central depression. These lesions are typically 1 to 5 cm wide. Although the classical appearance of GA is annular, the rings may not always be complete. Most importantly, there is no scaling, which one would expect to see in tinea infections, also known as “ringworm.”

The most common form of granuloma annulare is localized, as it was in this case. It typically presents on the dorsal surfaces of extremities, especially of the hands and feet. When the presentation is classic, there is no need for a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

The most effective treatment for local disease is intralesional triamcinolone (5mg/mL). (See Watch & Learn: Intralesional injections.) The FP offered this treatment to the patient, and she tolerated the procedure well. The GA resolved over the weeks that followed with some faint hypopigmentation that lasted for several months. The patient was happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mauskar M, Usatine R. Granuloma annulare. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1141-1146.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed granuloma annulare (GA) in this patient, based on the typical clinical appearance of a raised ring on the back of the hand with no scale.

GA is a common benign cutaneous, inflammatory disorder of unknown origin. It affects twice as many women as men. It features annular lesions that have raised borders and are skin-colored to erythematous. The rings may become hyperpigmented and often feature a central depression. These lesions are typically 1 to 5 cm wide. Although the classical appearance of GA is annular, the rings may not always be complete. Most importantly, there is no scaling, which one would expect to see in tinea infections, also known as “ringworm.”

The most common form of granuloma annulare is localized, as it was in this case. It typically presents on the dorsal surfaces of extremities, especially of the hands and feet. When the presentation is classic, there is no need for a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

The most effective treatment for local disease is intralesional triamcinolone (5mg/mL). (See Watch & Learn: Intralesional injections.) The FP offered this treatment to the patient, and she tolerated the procedure well. The GA resolved over the weeks that followed with some faint hypopigmentation that lasted for several months. The patient was happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mauskar M, Usatine R. Granuloma annulare. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1141-1146.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Widespread hyperpigmented plaques

The differential diagnosis included psoriasis, drug eruption, and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A drug eruption could have been due to an over-the-counter medication or supplement, so the lack of improvement from stopping the antihypertensive medication did not rule out this diagnosis. Psoriasis does not always show erythema in persons of color, but these plaques were not typical of psoriasis. (There also were some flat patches that were even less typical of psoriasis.)

The FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on one of the hyperpigmented plaques on the abdomen. A 4-mm punch biopsy is generally an ideal method for determining the cause of an unknown skin rash, and it is usually better to choose a lesion on the upper body rather than below the waist if the rash is widespread. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also prescribed a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment for symptomatic relief as this could help any of the possible diagnoses being considered. The pathology report came back as mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The patient was sent to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and treatment. Mycosis fungoides can have both patches and plaques and frequently involves the trunk more than the extremities (which was the situation in this case). It is important to consider uncommon diagnoses like this in the differential when the initial diagnosis does not appear to be responding to treatment or there is something atypical about the presentation of an expected diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The differential diagnosis included psoriasis, drug eruption, and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A drug eruption could have been due to an over-the-counter medication or supplement, so the lack of improvement from stopping the antihypertensive medication did not rule out this diagnosis. Psoriasis does not always show erythema in persons of color, but these plaques were not typical of psoriasis. (There also were some flat patches that were even less typical of psoriasis.)

The FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on one of the hyperpigmented plaques on the abdomen. A 4-mm punch biopsy is generally an ideal method for determining the cause of an unknown skin rash, and it is usually better to choose a lesion on the upper body rather than below the waist if the rash is widespread. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also prescribed a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment for symptomatic relief as this could help any of the possible diagnoses being considered. The pathology report came back as mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The patient was sent to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and treatment. Mycosis fungoides can have both patches and plaques and frequently involves the trunk more than the extremities (which was the situation in this case). It is important to consider uncommon diagnoses like this in the differential when the initial diagnosis does not appear to be responding to treatment or there is something atypical about the presentation of an expected diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The differential diagnosis included psoriasis, drug eruption, and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A drug eruption could have been due to an over-the-counter medication or supplement, so the lack of improvement from stopping the antihypertensive medication did not rule out this diagnosis. Psoriasis does not always show erythema in persons of color, but these plaques were not typical of psoriasis. (There also were some flat patches that were even less typical of psoriasis.)

The FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on one of the hyperpigmented plaques on the abdomen. A 4-mm punch biopsy is generally an ideal method for determining the cause of an unknown skin rash, and it is usually better to choose a lesion on the upper body rather than below the waist if the rash is widespread. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also prescribed a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment for symptomatic relief as this could help any of the possible diagnoses being considered. The pathology report came back as mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The patient was sent to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and treatment. Mycosis fungoides can have both patches and plaques and frequently involves the trunk more than the extremities (which was the situation in this case). It is important to consider uncommon diagnoses like this in the differential when the initial diagnosis does not appear to be responding to treatment or there is something atypical about the presentation of an expected diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com