User login

Bilateral axillary rash

The FP diagnosed inverse psoriasis. Important clues that pointed to the diagnosis included the history of the rash not resolving with antifungal medications or after stopping use of deodorant (evidence that this was unlikely to be contact dermatitis), along with the fingernail pits.

Inverse psoriasis is found in the intertriginous areas of the axillae, groin, inframammary folds, and intergluteal fold. “Inverse” refers to the fact that the distribution is not on extensor surfaces, but in areas of body folds. Morphologically, the lesions have little to no visible scale and, therefore, are not easily recognized as psoriasis. The color is generally pink to red, but can be hyperpigmented in dark-skinned individuals.

Inverse psoriasis often mimics Candida and tinea infections; when antifungal medicines are not working, always consider inverse psoriasis. Not all erythematous plaques in the axillae are fungal. It helps to look for clues such as nail changes (such as the pits noted with this patient) or subtle plaques on the elbows, knees, or umbilicus to make the diagnosis of psoriasis.

Treatment consists of a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. The choice of vehicle can be based on patient preference; creams and ointments both work to treat inverse psoriasis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid (0.1% triamcinolone ointment) to be applied twice daily. Both the FP and the patient agreed that an ointment, rather than a cream, would be the better option. While the ointment can be greasy, creams often have an alcohol base and are thus more likely than a petrolatum ointment to sting.

The FP also checked for psoriasis risk factors and discovered that the patient was neither smoking nor drinking alcohol. However, the patient was overweight and agreed to improve her diet and exercise for reasonable weight loss.

At her follow-up 2 months later, the patient’s psoriasis was 90% better. She had also lost 5 pounds. While discussing treatment options, a joint decision was made to try a higher-potency topical steroid ointment with the goal of 100% clearance. The patient understood the risk of skin atrophy and was given instructions to return to the mid-potency steroid once the higher-potency steroid achieved satisfactory results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed inverse psoriasis. Important clues that pointed to the diagnosis included the history of the rash not resolving with antifungal medications or after stopping use of deodorant (evidence that this was unlikely to be contact dermatitis), along with the fingernail pits.

Inverse psoriasis is found in the intertriginous areas of the axillae, groin, inframammary folds, and intergluteal fold. “Inverse” refers to the fact that the distribution is not on extensor surfaces, but in areas of body folds. Morphologically, the lesions have little to no visible scale and, therefore, are not easily recognized as psoriasis. The color is generally pink to red, but can be hyperpigmented in dark-skinned individuals.

Inverse psoriasis often mimics Candida and tinea infections; when antifungal medicines are not working, always consider inverse psoriasis. Not all erythematous plaques in the axillae are fungal. It helps to look for clues such as nail changes (such as the pits noted with this patient) or subtle plaques on the elbows, knees, or umbilicus to make the diagnosis of psoriasis.

Treatment consists of a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. The choice of vehicle can be based on patient preference; creams and ointments both work to treat inverse psoriasis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid (0.1% triamcinolone ointment) to be applied twice daily. Both the FP and the patient agreed that an ointment, rather than a cream, would be the better option. While the ointment can be greasy, creams often have an alcohol base and are thus more likely than a petrolatum ointment to sting.

The FP also checked for psoriasis risk factors and discovered that the patient was neither smoking nor drinking alcohol. However, the patient was overweight and agreed to improve her diet and exercise for reasonable weight loss.

At her follow-up 2 months later, the patient’s psoriasis was 90% better. She had also lost 5 pounds. While discussing treatment options, a joint decision was made to try a higher-potency topical steroid ointment with the goal of 100% clearance. The patient understood the risk of skin atrophy and was given instructions to return to the mid-potency steroid once the higher-potency steroid achieved satisfactory results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed inverse psoriasis. Important clues that pointed to the diagnosis included the history of the rash not resolving with antifungal medications or after stopping use of deodorant (evidence that this was unlikely to be contact dermatitis), along with the fingernail pits.

Inverse psoriasis is found in the intertriginous areas of the axillae, groin, inframammary folds, and intergluteal fold. “Inverse” refers to the fact that the distribution is not on extensor surfaces, but in areas of body folds. Morphologically, the lesions have little to no visible scale and, therefore, are not easily recognized as psoriasis. The color is generally pink to red, but can be hyperpigmented in dark-skinned individuals.

Inverse psoriasis often mimics Candida and tinea infections; when antifungal medicines are not working, always consider inverse psoriasis. Not all erythematous plaques in the axillae are fungal. It helps to look for clues such as nail changes (such as the pits noted with this patient) or subtle plaques on the elbows, knees, or umbilicus to make the diagnosis of psoriasis.

Treatment consists of a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. The choice of vehicle can be based on patient preference; creams and ointments both work to treat inverse psoriasis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid (0.1% triamcinolone ointment) to be applied twice daily. Both the FP and the patient agreed that an ointment, rather than a cream, would be the better option. While the ointment can be greasy, creams often have an alcohol base and are thus more likely than a petrolatum ointment to sting.

The FP also checked for psoriasis risk factors and discovered that the patient was neither smoking nor drinking alcohol. However, the patient was overweight and agreed to improve her diet and exercise for reasonable weight loss.

At her follow-up 2 months later, the patient’s psoriasis was 90% better. She had also lost 5 pounds. While discussing treatment options, a joint decision was made to try a higher-potency topical steroid ointment with the goal of 100% clearance. The patient understood the risk of skin atrophy and was given instructions to return to the mid-potency steroid once the higher-potency steroid achieved satisfactory results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Blister on leg

The patient was given a diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum, a benign self-limited condition. Bullous diabeticorum is trauma-induced, painless blistering that typically occurs in an acral distribution in individuals with diabetes.

The differential diagnosis for bullous diseases is vast and includes such dangerous diseases as pemphigus vulgaris and toxic epidermal necrolysis. The Nikolsky sign and the Asboe-Hansen sign are both positive in pemphigus vulgaris and toxic epidermal necrolysis, and negative in bullosis diabeticorum.

- The Nikolsky sign is positive if the skin shears off when lateral pressure is applied to unblistered skin.

- The Asboe-Hansen sign is positive if the bullae extend to surrounding skin when vertical pressure is applied.

In this case, the bulla was drained with a sterile needle and no further bullae developed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sauceda AT, Usatine R. Bullous diseases--overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:784-789.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See Http://usatinemedia.com

The patient was given a diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum, a benign self-limited condition. Bullous diabeticorum is trauma-induced, painless blistering that typically occurs in an acral distribution in individuals with diabetes.

The differential diagnosis for bullous diseases is vast and includes such dangerous diseases as pemphigus vulgaris and toxic epidermal necrolysis. The Nikolsky sign and the Asboe-Hansen sign are both positive in pemphigus vulgaris and toxic epidermal necrolysis, and negative in bullosis diabeticorum.

- The Nikolsky sign is positive if the skin shears off when lateral pressure is applied to unblistered skin.

- The Asboe-Hansen sign is positive if the bullae extend to surrounding skin when vertical pressure is applied.

In this case, the bulla was drained with a sterile needle and no further bullae developed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sauceda AT, Usatine R. Bullous diseases--overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:784-789.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See Http://usatinemedia.com

The patient was given a diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum, a benign self-limited condition. Bullous diabeticorum is trauma-induced, painless blistering that typically occurs in an acral distribution in individuals with diabetes.

The differential diagnosis for bullous diseases is vast and includes such dangerous diseases as pemphigus vulgaris and toxic epidermal necrolysis. The Nikolsky sign and the Asboe-Hansen sign are both positive in pemphigus vulgaris and toxic epidermal necrolysis, and negative in bullosis diabeticorum.

- The Nikolsky sign is positive if the skin shears off when lateral pressure is applied to unblistered skin.

- The Asboe-Hansen sign is positive if the bullae extend to surrounding skin when vertical pressure is applied.

In this case, the bulla was drained with a sterile needle and no further bullae developed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sauceda AT, Usatine R. Bullous diseases--overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:784-789.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See Http://usatinemedia.com

Itchy rash during pregnancy

The FP diagnosed pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. PUPPP is usually diagnosed by its characteristic findings in the history and physical examination.

PUPPP typically presents as erythematous papules and plaques within striae (with periumbilical sparing) late in the third trimester. Extreme pruritus is a hallmark of PUPPP and is present in all patients. Abdominal striae are the most common initial symptoms. The lesions usually spread to the extremities and coalesce to form urticarial plaques.

General measures such as cool baths, frequent application of emollients, wet soaks, or cool packs applied to the skin provide some symptomatic relief. First-line pharmacologic therapy consists of topical steroids and oral antihistamines to alleviate symptoms.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid, 0.1% triamcinolone cream twice daily (pregnancy class B). The patient was given the choice of steroid vehicle and chose the cream over the ointment. Both vehicles work to treat PUPPP, but the one that will work best is the one the patient will actually use.

The FP also recommended over-the-counter diphenhydramine 25 mg for additional symptomatic relief of pruritus (pregnancy class B). At her following prenatal visit, the patient’s symptoms were about 80% better and she was tolerating the pruritus. She was relieved to learn that this condition would resolve after pregnancy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 467-470.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. PUPPP is usually diagnosed by its characteristic findings in the history and physical examination.

PUPPP typically presents as erythematous papules and plaques within striae (with periumbilical sparing) late in the third trimester. Extreme pruritus is a hallmark of PUPPP and is present in all patients. Abdominal striae are the most common initial symptoms. The lesions usually spread to the extremities and coalesce to form urticarial plaques.

General measures such as cool baths, frequent application of emollients, wet soaks, or cool packs applied to the skin provide some symptomatic relief. First-line pharmacologic therapy consists of topical steroids and oral antihistamines to alleviate symptoms.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid, 0.1% triamcinolone cream twice daily (pregnancy class B). The patient was given the choice of steroid vehicle and chose the cream over the ointment. Both vehicles work to treat PUPPP, but the one that will work best is the one the patient will actually use.

The FP also recommended over-the-counter diphenhydramine 25 mg for additional symptomatic relief of pruritus (pregnancy class B). At her following prenatal visit, the patient’s symptoms were about 80% better and she was tolerating the pruritus. She was relieved to learn that this condition would resolve after pregnancy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 467-470.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. PUPPP is usually diagnosed by its characteristic findings in the history and physical examination.

PUPPP typically presents as erythematous papules and plaques within striae (with periumbilical sparing) late in the third trimester. Extreme pruritus is a hallmark of PUPPP and is present in all patients. Abdominal striae are the most common initial symptoms. The lesions usually spread to the extremities and coalesce to form urticarial plaques.

General measures such as cool baths, frequent application of emollients, wet soaks, or cool packs applied to the skin provide some symptomatic relief. First-line pharmacologic therapy consists of topical steroids and oral antihistamines to alleviate symptoms.

In this case, the FP prescribed a mid-potency topical corticosteroid, 0.1% triamcinolone cream twice daily (pregnancy class B). The patient was given the choice of steroid vehicle and chose the cream over the ointment. Both vehicles work to treat PUPPP, but the one that will work best is the one the patient will actually use.

The FP also recommended over-the-counter diphenhydramine 25 mg for additional symptomatic relief of pruritus (pregnancy class B). At her following prenatal visit, the patient’s symptoms were about 80% better and she was tolerating the pruritus. She was relieved to learn that this condition would resolve after pregnancy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 467-470.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Brown patch on infant

The FP diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa. If urticaria pigmentosa is suspected, it is helpful to stroke the lesion with a fingernail or the wooden end of a cotton-tipped applicator. This induces erythema and a wheal that is confined to the stroked site within the lesion—a positive Darier sign.

Urticaria pigmentosa is a form of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), in which there are too many mast cells in the skin. More serious forms of MCAS in adults include systemic mastocytosis and cutaneous mastocytosis. Urticaria pigmentosa is a self-limiting problem in young children that rarely causes sufficient symptoms to warrant treatment.

In this case, the FP assured the mother that this was not dangerous and would go away over time on its own. The FP wrote down the name of the condition for the mother and explained to her that if she noticed any changes or new symptoms, she should return for further evaluation and treatment. The mother was satisfied with this explanation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Urticaria and angioedema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 863-870.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa. If urticaria pigmentosa is suspected, it is helpful to stroke the lesion with a fingernail or the wooden end of a cotton-tipped applicator. This induces erythema and a wheal that is confined to the stroked site within the lesion—a positive Darier sign.

Urticaria pigmentosa is a form of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), in which there are too many mast cells in the skin. More serious forms of MCAS in adults include systemic mastocytosis and cutaneous mastocytosis. Urticaria pigmentosa is a self-limiting problem in young children that rarely causes sufficient symptoms to warrant treatment.

In this case, the FP assured the mother that this was not dangerous and would go away over time on its own. The FP wrote down the name of the condition for the mother and explained to her that if she noticed any changes or new symptoms, she should return for further evaluation and treatment. The mother was satisfied with this explanation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Urticaria and angioedema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 863-870.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa. If urticaria pigmentosa is suspected, it is helpful to stroke the lesion with a fingernail or the wooden end of a cotton-tipped applicator. This induces erythema and a wheal that is confined to the stroked site within the lesion—a positive Darier sign.

Urticaria pigmentosa is a form of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), in which there are too many mast cells in the skin. More serious forms of MCAS in adults include systemic mastocytosis and cutaneous mastocytosis. Urticaria pigmentosa is a self-limiting problem in young children that rarely causes sufficient symptoms to warrant treatment.

In this case, the FP assured the mother that this was not dangerous and would go away over time on its own. The FP wrote down the name of the condition for the mother and explained to her that if she noticed any changes or new symptoms, she should return for further evaluation and treatment. The mother was satisfied with this explanation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Urticaria and angioedema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 863-870.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash in HIV-positive man

Taking into consideration the patient’s 2 predisposing risk factors (AIDS and dementia), the FP diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis. The FP also noted seborrheic dermatitis on the scalp. The scalp is frequently involved in cases of seborrheic dermatitis on the face.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common, chronic, relapsing dermatitis affecting sebum-rich areas of the body. Its presentation may vary from mild erythema to greasy scale, and rarely, to erythroderma. Patients with seborrheic dermatitis may be colonized with certain species of lipophilic yeast of the genus Malassezia (also known as Pityrosporum). Malassezia, however, is considered normal skin flora because it is also found in unaffected people.

Some evidence suggests that an overgrowth of Malassezia may produce different irritants or metabolites on affected skin, leading to inflammation. It’s postulated that an overgrowth of Malassezia leads to the inflammatory dermatitis in seborrhea.

The goals of treatment are to diminish the fungal overgrowth and treat the inflammatory response. Thus, the mainstay of treatment is ongoing topical antifungals in shampoos and other preparations, along with a topical steroid to treat the inflammation.

The FP prescribed 2% ketoconazole shampoo to be used twice weekly and suggested that a selenium-containing shampoo be used on the other days of the week, as well as a 2.5% hydrocortisone cream to be applied twice daily to the face until the dermatitis resolved. The FP also prescribed a topical antifungal, cyclopirox 1% cream, to be applied twice daily on an ongoing basis to keep the Malassezia under control. At a one-month follow-up, the patient’s skin and scalp were cleared.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hancock M, Bae Y, Usatine R. Seborrheic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 871-877.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Taking into consideration the patient’s 2 predisposing risk factors (AIDS and dementia), the FP diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis. The FP also noted seborrheic dermatitis on the scalp. The scalp is frequently involved in cases of seborrheic dermatitis on the face.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common, chronic, relapsing dermatitis affecting sebum-rich areas of the body. Its presentation may vary from mild erythema to greasy scale, and rarely, to erythroderma. Patients with seborrheic dermatitis may be colonized with certain species of lipophilic yeast of the genus Malassezia (also known as Pityrosporum). Malassezia, however, is considered normal skin flora because it is also found in unaffected people.

Some evidence suggests that an overgrowth of Malassezia may produce different irritants or metabolites on affected skin, leading to inflammation. It’s postulated that an overgrowth of Malassezia leads to the inflammatory dermatitis in seborrhea.

The goals of treatment are to diminish the fungal overgrowth and treat the inflammatory response. Thus, the mainstay of treatment is ongoing topical antifungals in shampoos and other preparations, along with a topical steroid to treat the inflammation.

The FP prescribed 2% ketoconazole shampoo to be used twice weekly and suggested that a selenium-containing shampoo be used on the other days of the week, as well as a 2.5% hydrocortisone cream to be applied twice daily to the face until the dermatitis resolved. The FP also prescribed a topical antifungal, cyclopirox 1% cream, to be applied twice daily on an ongoing basis to keep the Malassezia under control. At a one-month follow-up, the patient’s skin and scalp were cleared.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hancock M, Bae Y, Usatine R. Seborrheic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 871-877.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Taking into consideration the patient’s 2 predisposing risk factors (AIDS and dementia), the FP diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis. The FP also noted seborrheic dermatitis on the scalp. The scalp is frequently involved in cases of seborrheic dermatitis on the face.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common, chronic, relapsing dermatitis affecting sebum-rich areas of the body. Its presentation may vary from mild erythema to greasy scale, and rarely, to erythroderma. Patients with seborrheic dermatitis may be colonized with certain species of lipophilic yeast of the genus Malassezia (also known as Pityrosporum). Malassezia, however, is considered normal skin flora because it is also found in unaffected people.

Some evidence suggests that an overgrowth of Malassezia may produce different irritants or metabolites on affected skin, leading to inflammation. It’s postulated that an overgrowth of Malassezia leads to the inflammatory dermatitis in seborrhea.

The goals of treatment are to diminish the fungal overgrowth and treat the inflammatory response. Thus, the mainstay of treatment is ongoing topical antifungals in shampoos and other preparations, along with a topical steroid to treat the inflammation.

The FP prescribed 2% ketoconazole shampoo to be used twice weekly and suggested that a selenium-containing shampoo be used on the other days of the week, as well as a 2.5% hydrocortisone cream to be applied twice daily to the face until the dermatitis resolved. The FP also prescribed a topical antifungal, cyclopirox 1% cream, to be applied twice daily on an ongoing basis to keep the Malassezia under control. At a one-month follow-up, the patient’s skin and scalp were cleared.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hancock M, Bae Y, Usatine R. Seborrheic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 871-877.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

A sheep in wolf’s clothing?

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

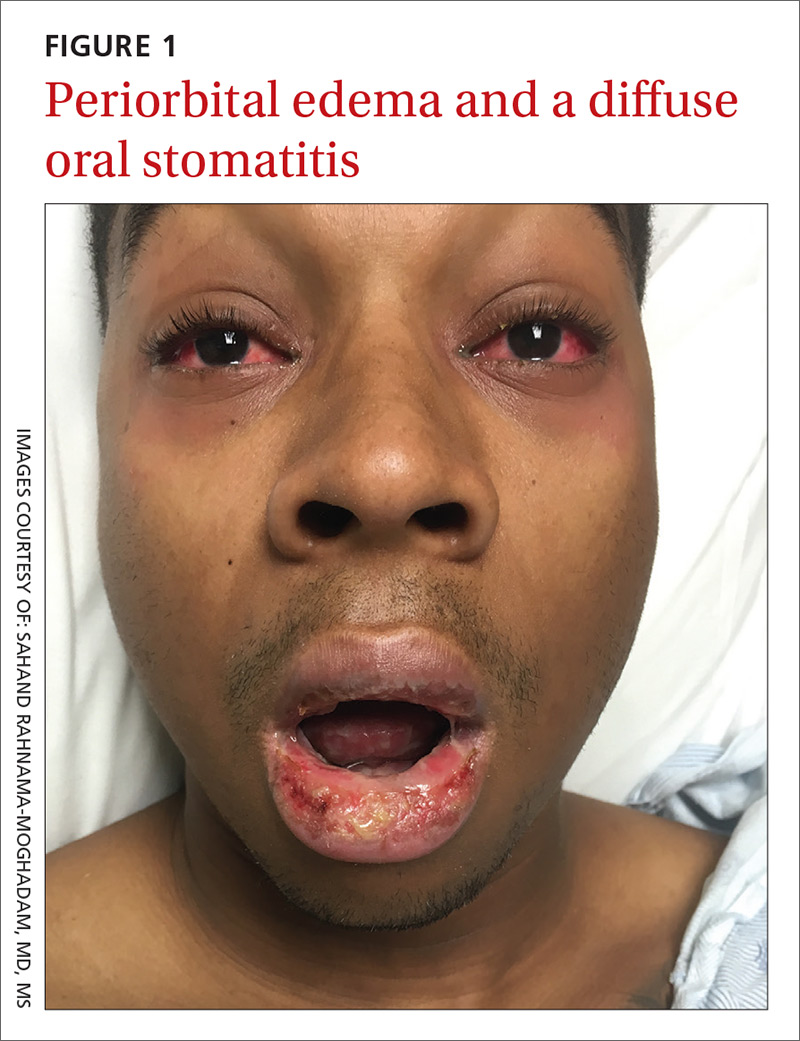

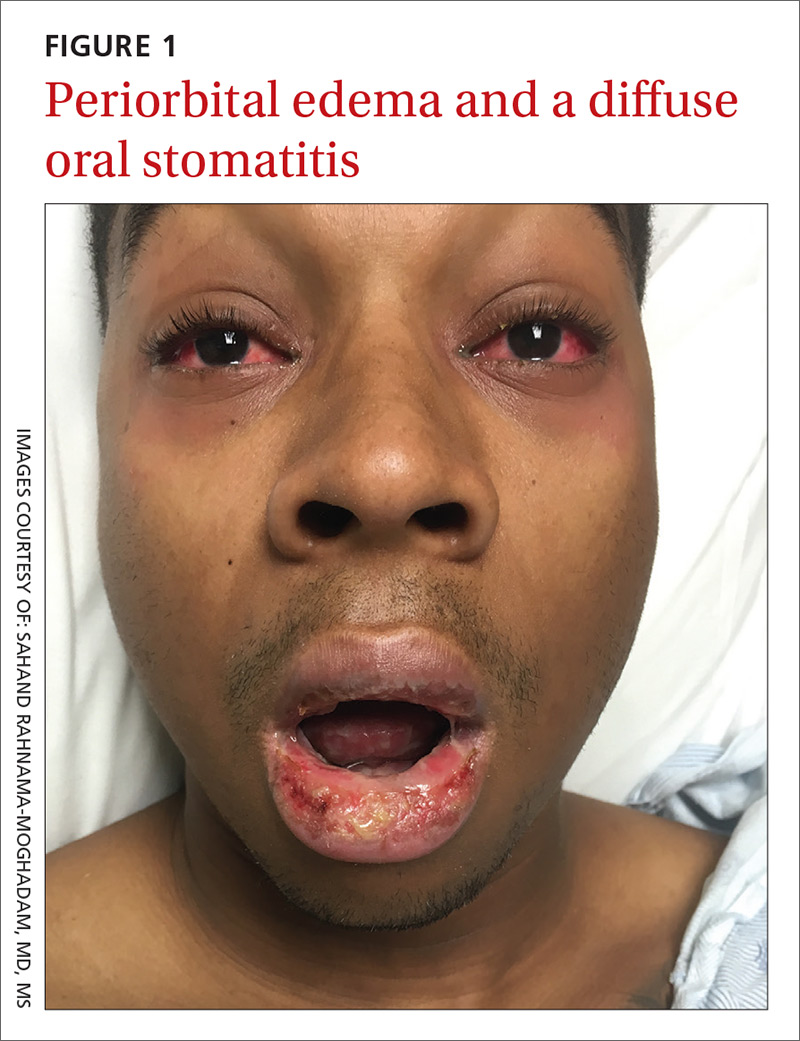

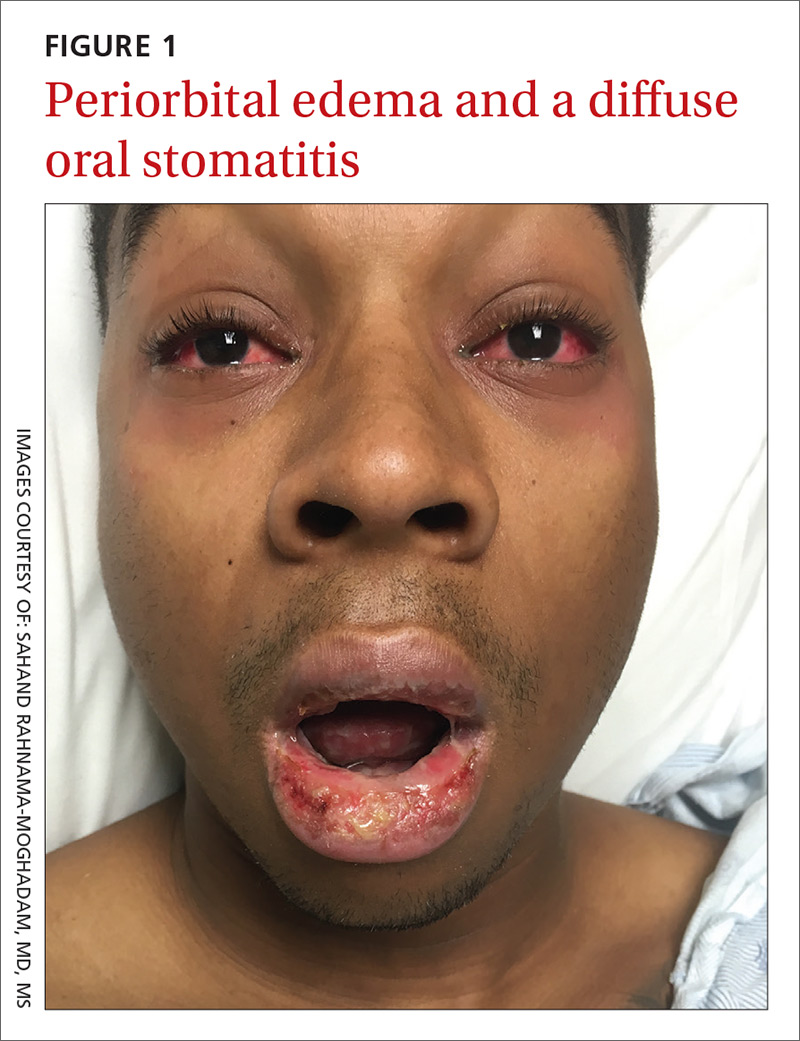

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

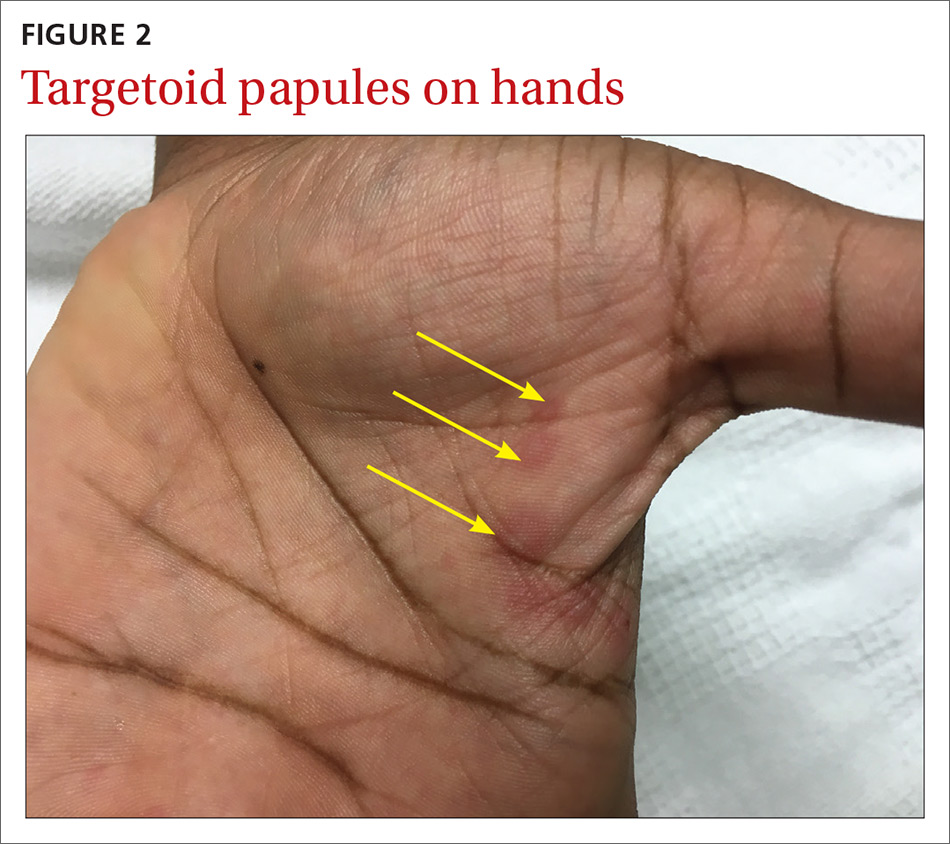

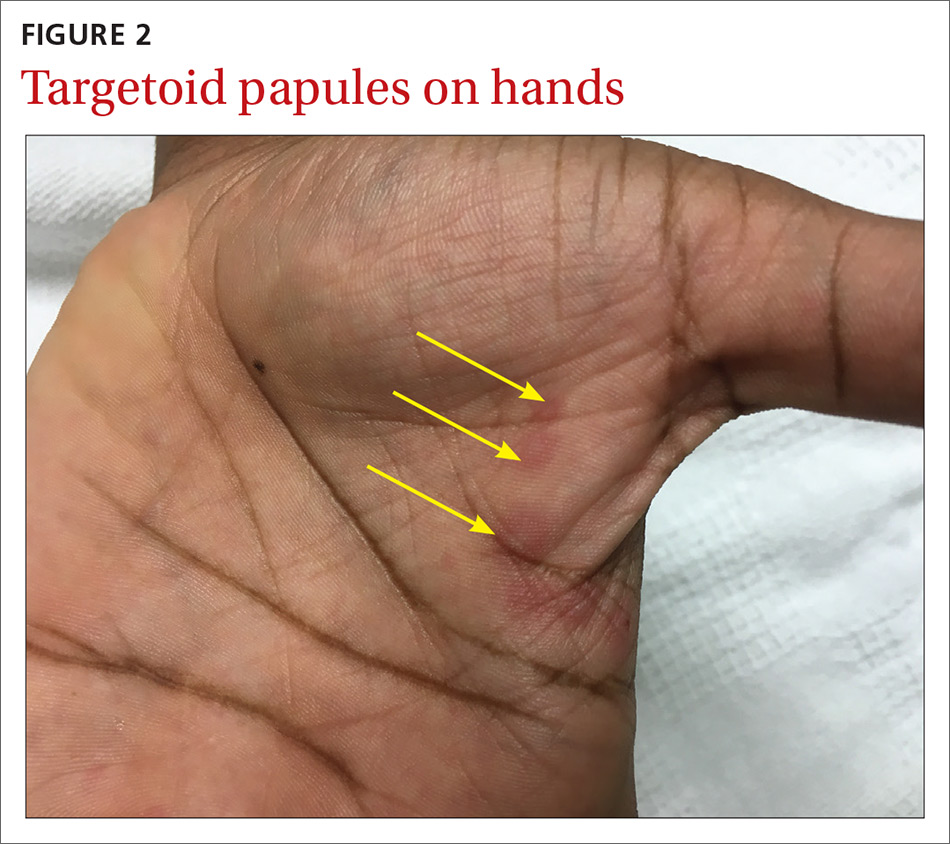

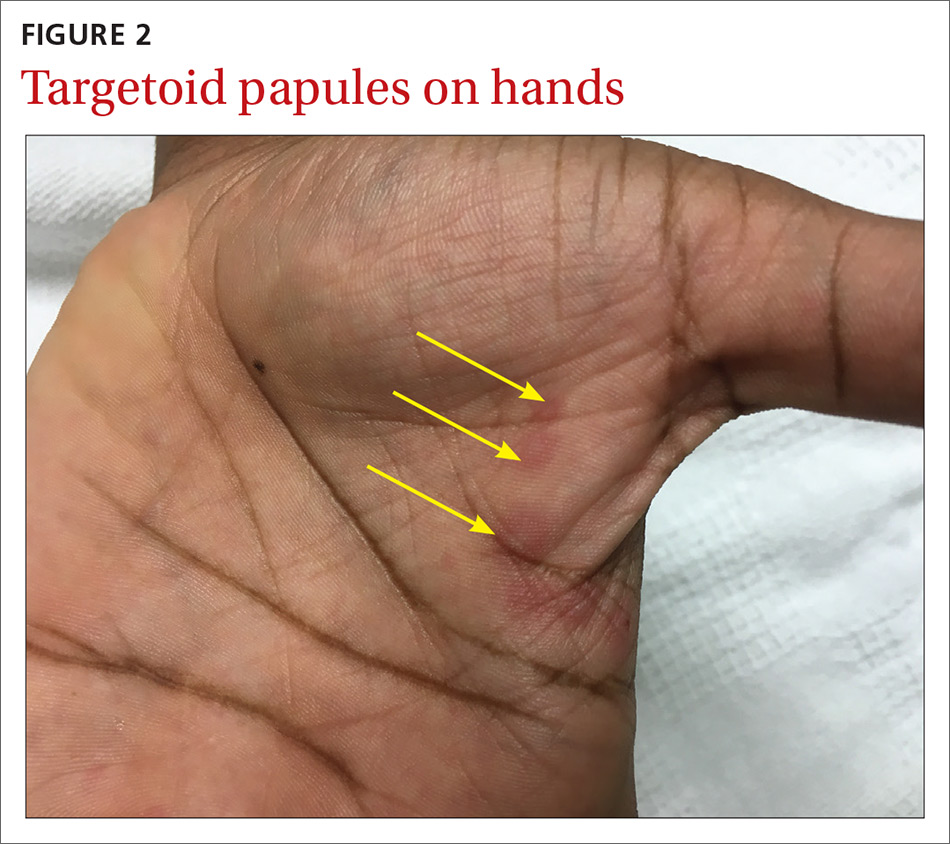

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; [email protected].

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.

2. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

3. Dinulos JG. What’s new with common, uncommon and rare rashes in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:261-266.

4. Meyer Sauteur PM, Goetschel P, Lautenschlager S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and mucositis–part of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome spectrum. J Dtsh Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:740-746.

5. Figueira-Coelho J, Lourenço S, Pires AC, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:399-403.

6. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

7. Zipitis CS, Thalange N. Intravenous immunoglobulins for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with minimal skin manifestations. Eur J Pediatr.2007;166:585-588.

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; [email protected].

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; [email protected].

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.

2. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

3. Dinulos JG. What’s new with common, uncommon and rare rashes in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:261-266.

4. Meyer Sauteur PM, Goetschel P, Lautenschlager S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and mucositis–part of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome spectrum. J Dtsh Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:740-746.

5. Figueira-Coelho J, Lourenço S, Pires AC, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:399-403.

6. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

7. Zipitis CS, Thalange N. Intravenous immunoglobulins for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with minimal skin manifestations. Eur J Pediatr.2007;166:585-588.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.

2. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

3. Dinulos JG. What’s new with common, uncommon and rare rashes in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:261-266.

4. Meyer Sauteur PM, Goetschel P, Lautenschlager S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and mucositis–part of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome spectrum. J Dtsh Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:740-746.

5. Figueira-Coelho J, Lourenço S, Pires AC, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:399-403.

6. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

7. Zipitis CS, Thalange N. Intravenous immunoglobulins for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with minimal skin manifestations. Eur J Pediatr.2007;166:585-588.

Recalcitrant genital papules

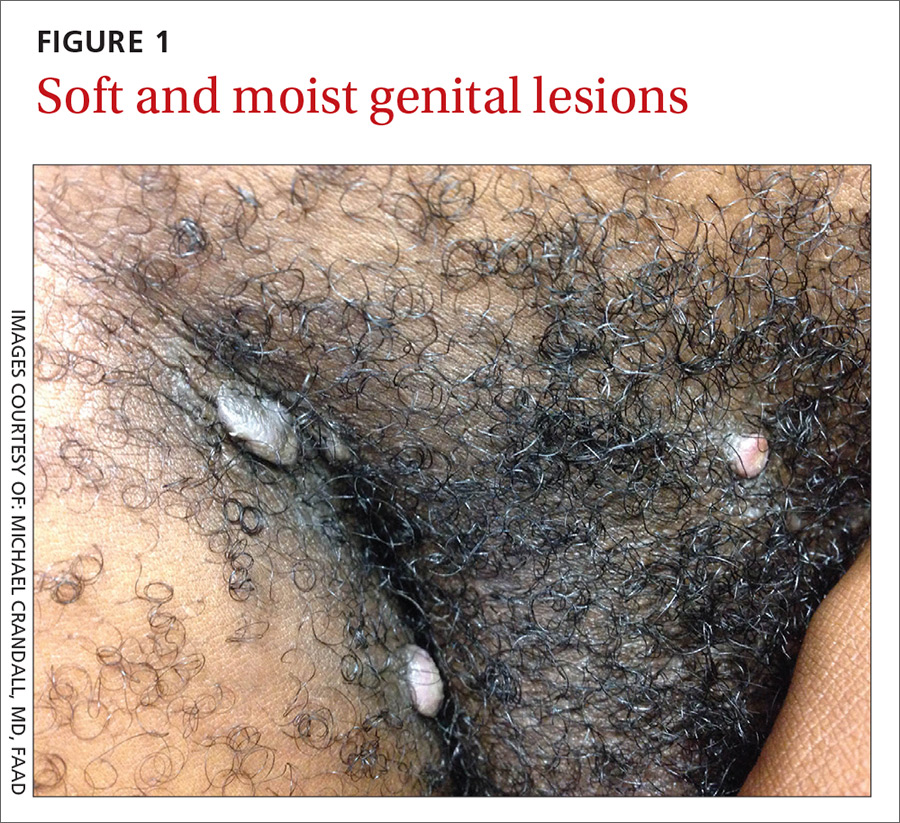

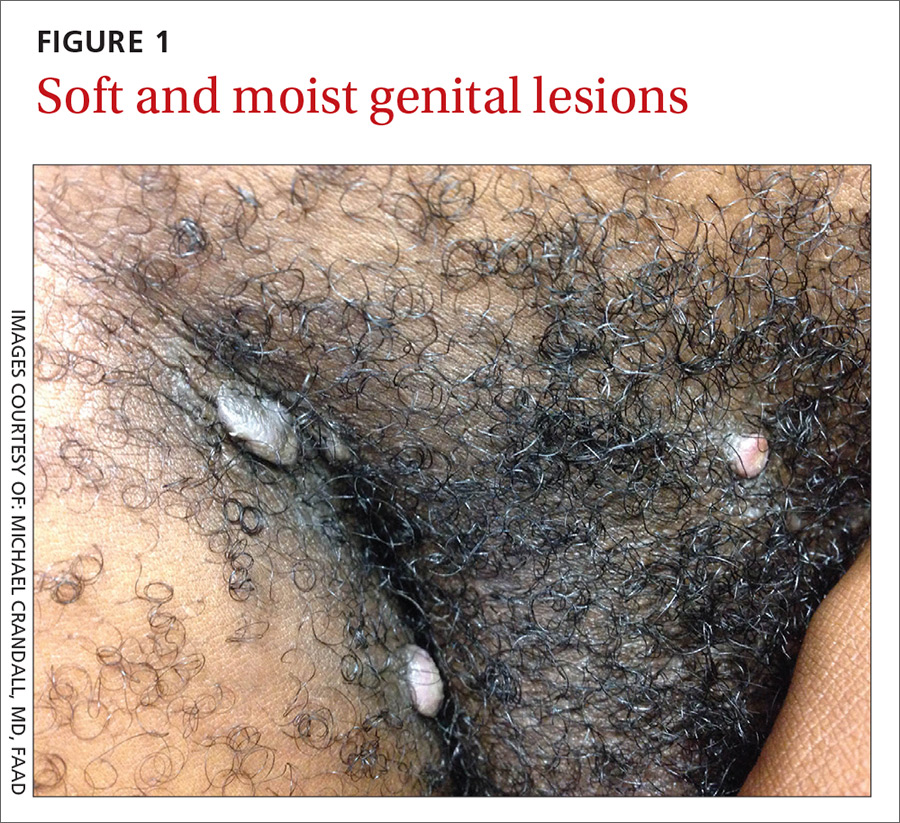

A 21-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of painless genital and perianal lesions. The patient reported having unprotected sex in recent months, but had no prior history of oral, penile, or anal mucosal lesions or ulcers. He was not on any medications or immunosuppressive agents and noted that the lesions did not represent a recurrence. He also reported a nonspecific, asymptomatic rash on his trunk and extremities that had been present for an unknown period of time.

The patient indicated that his primary care physician had looked at the genital/perianal lesions and told him they were genital warts. Previous treatments included an over-the-counter wart medication, cryotherapy, and a course of imiquimod, but none had helped.

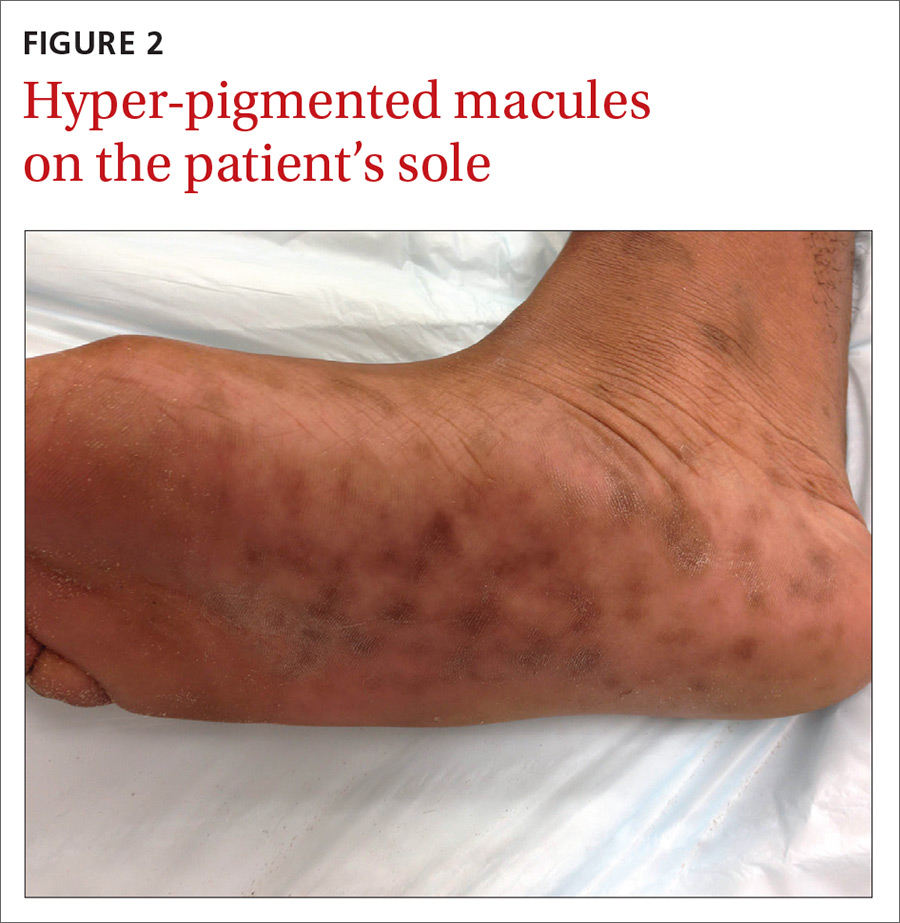

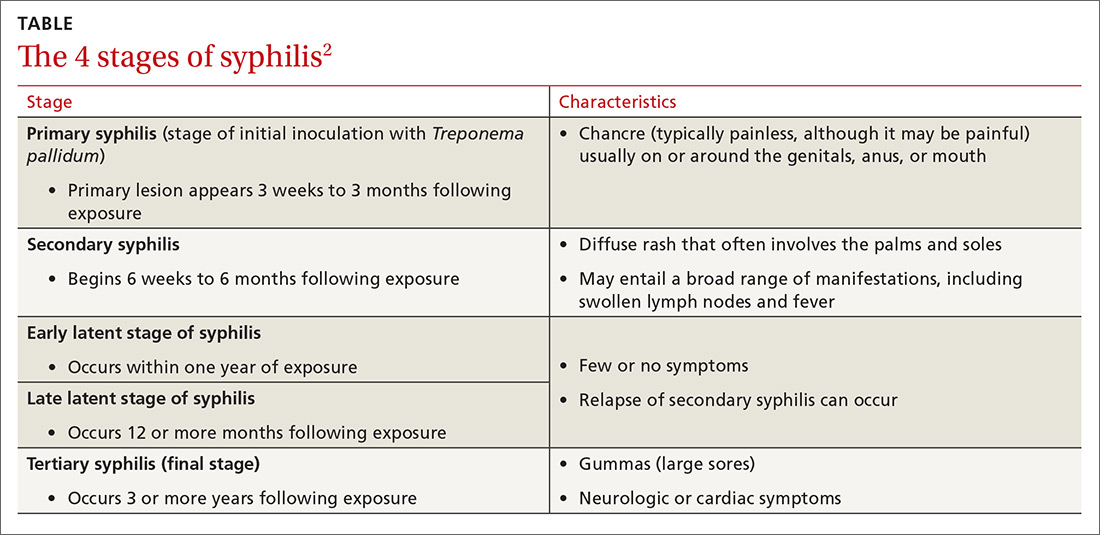

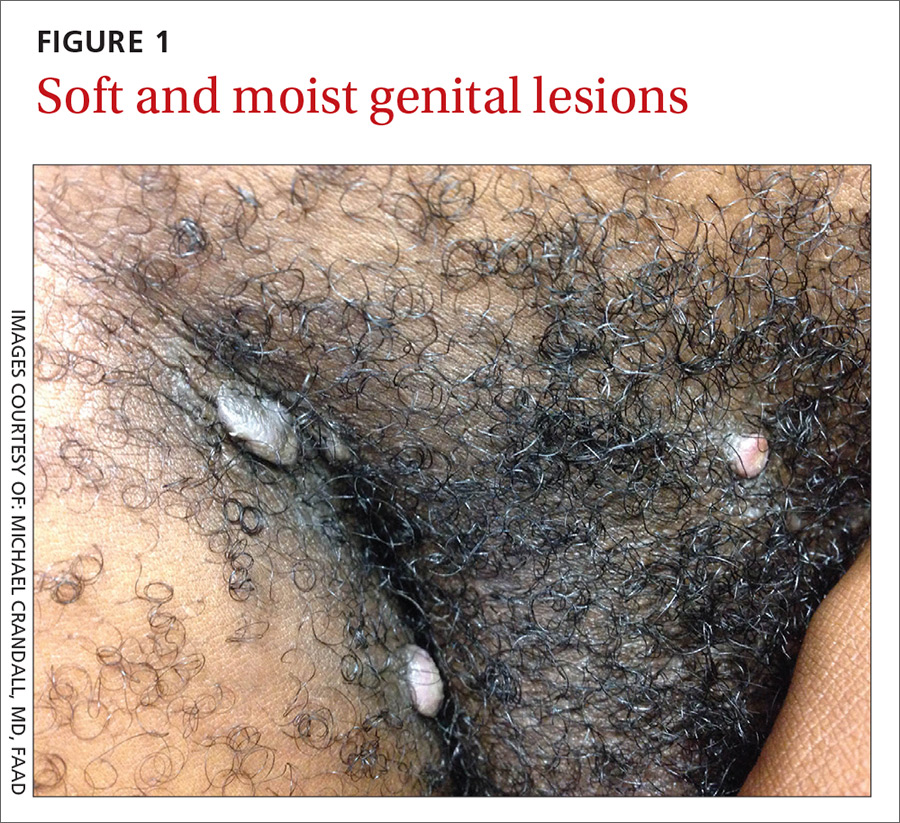

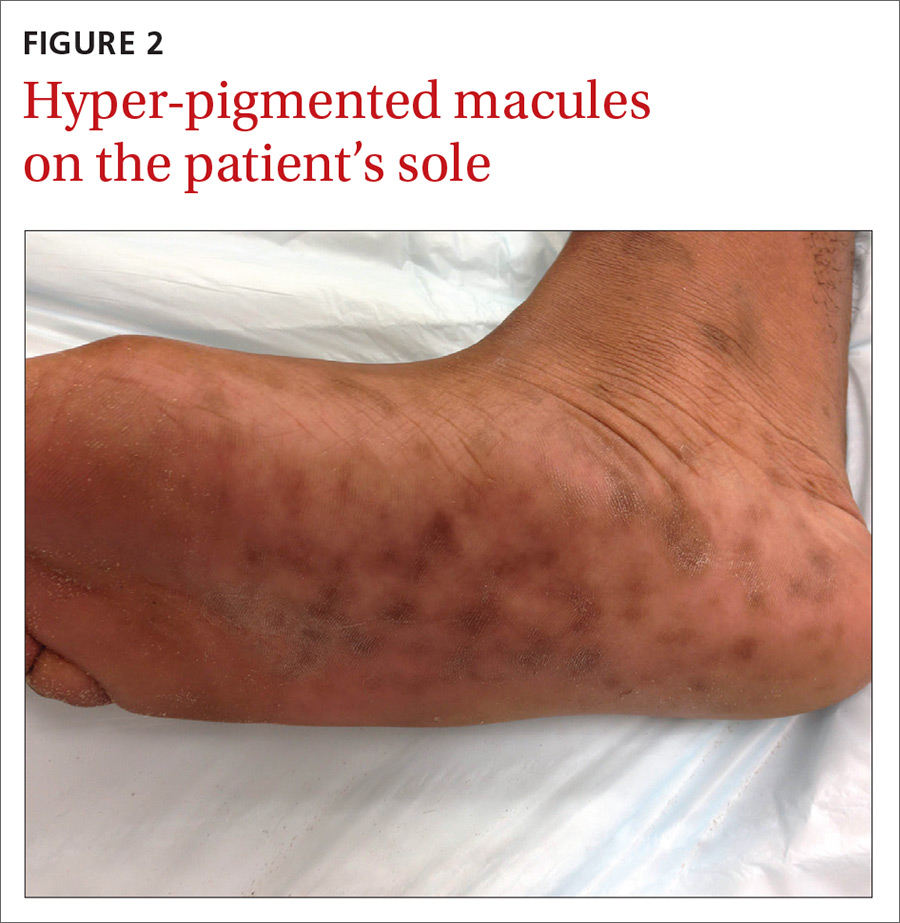

The physical examination revealed multiple soft, moist, beefy papules and plaques around the genital area (FIGURE 1) and perianal region. In addition, there were multiple hyper-pigmented macules on the patient’s palms and soles (FIGURE 2), and reticulated, patchy eruptions on his arms, chest (FIGURE 3), and back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

The appearance of the genital and perianal lesions was consistent with condylomata lata—a cutaneous sign of secondary syphilis—rather than genital warts. The presence of a rash on the patient’s trunk and extremities further supported this diagnosis. We did a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and a Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test; we also tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient’s RPR titer was 1:128, and the T pallidum antibody test came back positive. HIV-1 and HIV-2 serology were negative.

Appearance of the lesions was a giveaway. Condylomata lata are flat-topped, broad papules that are usually located on folds of moist skin (particularly the genitals and anus), and have a smooth, gray, moist surface. Although they can be lobulated, they do not have the classic digitate projections that are characteristic of genital warts. A nonpruritic, symmetric, “raw ham”-colored papular eruption on a patient’s trunk, palms, and soles is also characteristic of secondary syphilis.1 In this case, the reticular pattern on the patient’s chest represented the commonly seen lenticular rash of secondary syphilis.

Cutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis contain numerous spirochetes (T pallidum) and are highly infectious. Systemic symptoms of secondary syphilis may include fatigue, generalized lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, myalgia, pharyngitis, and headache.

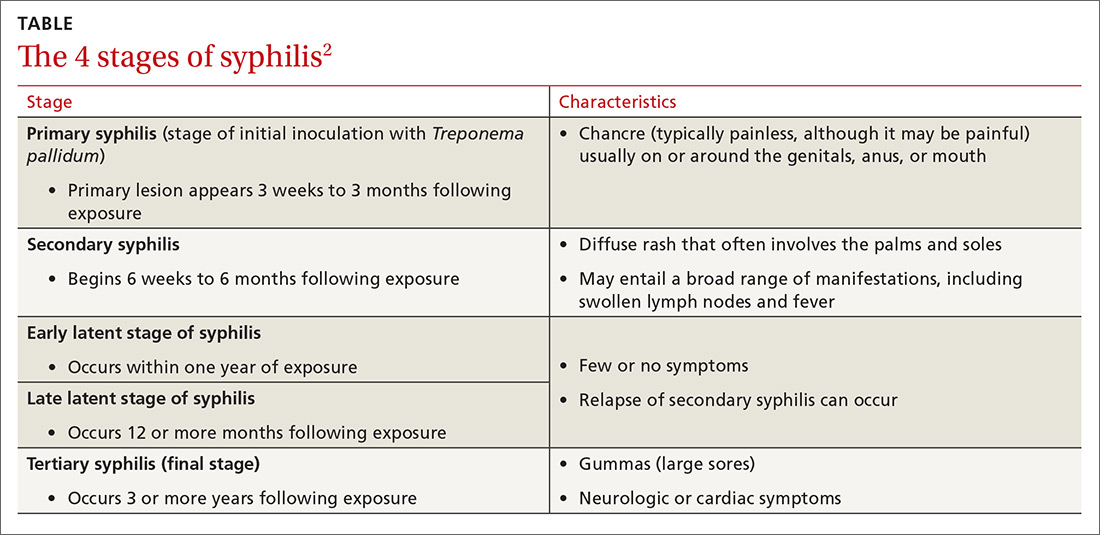

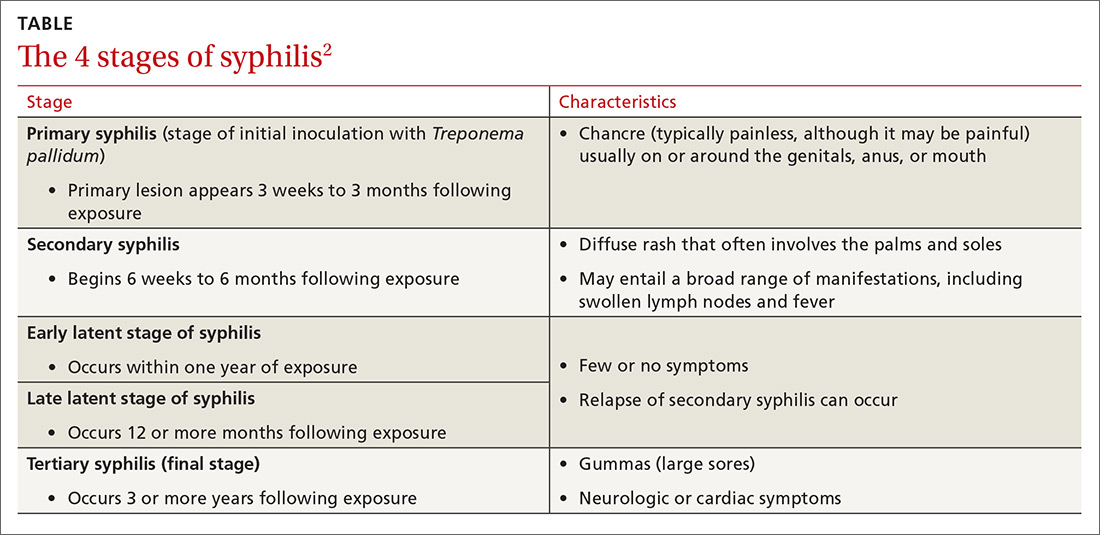

Some patients may report having a recent chancre—a painless, self-limiting ulcer in the genital area—which is characteristic of primary syphilis (see “Single nontender ulcer on the glans,” J Fam Pract. 2017;66:253-255). For more on the stages of syphilis, see the TABLE2. Our patient did not remember ever having a chancre.

Increase in cases. Rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased in the past decade. In 2014, approximately 20,000 syphilis cases were reported—a record high since 1994.3 Men who have sex with men are particularly affected; however, increases in infection rates have also been noted in women and across people of all ages and ethnicities.3

Rule out other causes of genital lesions

Condyloma acuminata, commonly called genital warts, are localized human papilloma virus (HPV) infections that appear as discrete, gray to pale pink, lobulated papules that may coalesce to form a large, cauliflower-like mass. They are sexually transmitted and commonly involve the genital and anal areas. While physicians may confuse condylomata lata with genital warts, diffuse skin rashes and constitutional symptoms are not usually seen with genital warts.4

Fordyce spots are small, whitish, raised papules on the glans or the shaft of the penis or the vulva of the vagina. They may also appear on the lips and oral mucosa. They are a result of prominent sebaceous glands and are harmless. They are not infectious or sexually transmitted.5,6

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an uncommon sexually transmitted disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. It is characterized by genital papules or ulcers, followed by bilateral, suppurative, inguinal adenitis known as buboes. The buboes may breakdown, form multiple fistulous openings, and discharge purulent material.6

Acute HIV may present with flu-like symptoms and well-circumscribed maculopapular rashes on the face, neck, and upper trunk. The palms and soles may also be affected. Patients with HIV may also develop genital plaque-like lesions from herpes simplex virus-2, genital warts from HPV, molluscum contagiosum, and, not uncommonly, anogenital malignancies.7,8

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) is a disorder that occurs predominantly in young adults and teenagers, with cosmetically displeasing brown scaling macules that may coalesce to form patches or plaques affecting the neck, chest, back, and axillae. It is often mistaken for tinea versicolor.9 In this case, the eruption on the chest closely resembled CARP, but a diagnosis of CARP would not have explained the genital lesions.

Confirm diagnosis with treponemal tests

Syphilis is often a clinical diagnosis with pathologic confirmation. Patients suspected of having syphilis should be screened with nontreponemal tests, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or the RPR test, which become positive within 3 weeks of developing primary syphilis.

Diagnosis is confirmed with specific treponemal testing, such as with a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay or the T pallidum particle agglutination test. HIV testing is recommended for all patients with syphilis.

Penicillin G is the mainstay of treatment

Proper selection of penicillin is paramount in the treatment of syphilis. Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis are treated with an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. Patients with late latent or latent syphilis of unknown duration are treated with 3 doses of the same injection at weekly intervals, totaling 7.2 million units of benzathine penicillin G.10 Certain penicillin preparations (eg, combinations of benzathine penicillin and procaine penicillin) are not appropriate treatments because they do not provide adequate amounts of the antibiotic.

Watch for this reaction. Approximately 30% of patients following penicillin treatment for spirochete infection develop a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR).11 JHR is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever, chills, myalgia, tachycardia, vasodilatation with flushing, exacerbated maculopapular skin rash, or mild hypotension. Care for JHR is generally supportive.

Our patient received an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. His skin eruption and condylomata lata lesions were completely resolved at follow-up 6 months later.

As recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,10 our patient’s RPR titers were repeated at 6 months and again at 12 months to verify a four-fold decline, indicating successful treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Bartels, MD, General Medicine, Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, 100 Brewster Blvd., Camp Lejeune, NC 28547; [email protected].

1. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Secondary syphilis. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:348-350.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis—CDC Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed May 31, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis. November 17, 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 30, 2017.

4. Karnes JB, Usatine RP. Management of external genital warts. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:312-318.

5. DuVivier A. Disorders of the sebaceous, sweat and apocrine glands. In: DuVivier A. Atlas of Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2013:326-330.

6. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:90-92.

7. Altman K, Vanness E, Westergaard RP. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus: a clinical update. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:464.

8. Maurer TA. Dermatologic manifestations of HIV infection. Top HIV Med. 2005;13:149-154.

9. Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:505-508.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf#. Accessed June 8, 2017.

11. Yang CJ, Lee NY, Lin YH, et al. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after penicillin therapy among patients with syphilis in the era of the hiv infection epidemic: incidence and risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:976-979.

A 21-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of painless genital and perianal lesions. The patient reported having unprotected sex in recent months, but had no prior history of oral, penile, or anal mucosal lesions or ulcers. He was not on any medications or immunosuppressive agents and noted that the lesions did not represent a recurrence. He also reported a nonspecific, asymptomatic rash on his trunk and extremities that had been present for an unknown period of time.

The patient indicated that his primary care physician had looked at the genital/perianal lesions and told him they were genital warts. Previous treatments included an over-the-counter wart medication, cryotherapy, and a course of imiquimod, but none had helped.

The physical examination revealed multiple soft, moist, beefy papules and plaques around the genital area (FIGURE 1) and perianal region. In addition, there were multiple hyper-pigmented macules on the patient’s palms and soles (FIGURE 2), and reticulated, patchy eruptions on his arms, chest (FIGURE 3), and back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

The appearance of the genital and perianal lesions was consistent with condylomata lata—a cutaneous sign of secondary syphilis—rather than genital warts. The presence of a rash on the patient’s trunk and extremities further supported this diagnosis. We did a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and a Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test; we also tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient’s RPR titer was 1:128, and the T pallidum antibody test came back positive. HIV-1 and HIV-2 serology were negative.

Appearance of the lesions was a giveaway. Condylomata lata are flat-topped, broad papules that are usually located on folds of moist skin (particularly the genitals and anus), and have a smooth, gray, moist surface. Although they can be lobulated, they do not have the classic digitate projections that are characteristic of genital warts. A nonpruritic, symmetric, “raw ham”-colored papular eruption on a patient’s trunk, palms, and soles is also characteristic of secondary syphilis.1 In this case, the reticular pattern on the patient’s chest represented the commonly seen lenticular rash of secondary syphilis.

Cutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis contain numerous spirochetes (T pallidum) and are highly infectious. Systemic symptoms of secondary syphilis may include fatigue, generalized lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, myalgia, pharyngitis, and headache.

Some patients may report having a recent chancre—a painless, self-limiting ulcer in the genital area—which is characteristic of primary syphilis (see “Single nontender ulcer on the glans,” J Fam Pract. 2017;66:253-255). For more on the stages of syphilis, see the TABLE2. Our patient did not remember ever having a chancre.

Increase in cases. Rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased in the past decade. In 2014, approximately 20,000 syphilis cases were reported—a record high since 1994.3 Men who have sex with men are particularly affected; however, increases in infection rates have also been noted in women and across people of all ages and ethnicities.3

Rule out other causes of genital lesions

Condyloma acuminata, commonly called genital warts, are localized human papilloma virus (HPV) infections that appear as discrete, gray to pale pink, lobulated papules that may coalesce to form a large, cauliflower-like mass. They are sexually transmitted and commonly involve the genital and anal areas. While physicians may confuse condylomata lata with genital warts, diffuse skin rashes and constitutional symptoms are not usually seen with genital warts.4

Fordyce spots are small, whitish, raised papules on the glans or the shaft of the penis or the vulva of the vagina. They may also appear on the lips and oral mucosa. They are a result of prominent sebaceous glands and are harmless. They are not infectious or sexually transmitted.5,6

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an uncommon sexually transmitted disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. It is characterized by genital papules or ulcers, followed by bilateral, suppurative, inguinal adenitis known as buboes. The buboes may breakdown, form multiple fistulous openings, and discharge purulent material.6

Acute HIV may present with flu-like symptoms and well-circumscribed maculopapular rashes on the face, neck, and upper trunk. The palms and soles may also be affected. Patients with HIV may also develop genital plaque-like lesions from herpes simplex virus-2, genital warts from HPV, molluscum contagiosum, and, not uncommonly, anogenital malignancies.7,8

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) is a disorder that occurs predominantly in young adults and teenagers, with cosmetically displeasing brown scaling macules that may coalesce to form patches or plaques affecting the neck, chest, back, and axillae. It is often mistaken for tinea versicolor.9 In this case, the eruption on the chest closely resembled CARP, but a diagnosis of CARP would not have explained the genital lesions.

Confirm diagnosis with treponemal tests

Syphilis is often a clinical diagnosis with pathologic confirmation. Patients suspected of having syphilis should be screened with nontreponemal tests, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or the RPR test, which become positive within 3 weeks of developing primary syphilis.

Diagnosis is confirmed with specific treponemal testing, such as with a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay or the T pallidum particle agglutination test. HIV testing is recommended for all patients with syphilis.

Penicillin G is the mainstay of treatment

Proper selection of penicillin is paramount in the treatment of syphilis. Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis are treated with an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. Patients with late latent or latent syphilis of unknown duration are treated with 3 doses of the same injection at weekly intervals, totaling 7.2 million units of benzathine penicillin G.10 Certain penicillin preparations (eg, combinations of benzathine penicillin and procaine penicillin) are not appropriate treatments because they do not provide adequate amounts of the antibiotic.

Watch for this reaction. Approximately 30% of patients following penicillin treatment for spirochete infection develop a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR).11 JHR is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever, chills, myalgia, tachycardia, vasodilatation with flushing, exacerbated maculopapular skin rash, or mild hypotension. Care for JHR is generally supportive.

Our patient received an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. His skin eruption and condylomata lata lesions were completely resolved at follow-up 6 months later.

As recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,10 our patient’s RPR titers were repeated at 6 months and again at 12 months to verify a four-fold decline, indicating successful treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Bartels, MD, General Medicine, Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, 100 Brewster Blvd., Camp Lejeune, NC 28547; [email protected].

A 21-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of painless genital and perianal lesions. The patient reported having unprotected sex in recent months, but had no prior history of oral, penile, or anal mucosal lesions or ulcers. He was not on any medications or immunosuppressive agents and noted that the lesions did not represent a recurrence. He also reported a nonspecific, asymptomatic rash on his trunk and extremities that had been present for an unknown period of time.

The patient indicated that his primary care physician had looked at the genital/perianal lesions and told him they were genital warts. Previous treatments included an over-the-counter wart medication, cryotherapy, and a course of imiquimod, but none had helped.

The physical examination revealed multiple soft, moist, beefy papules and plaques around the genital area (FIGURE 1) and perianal region. In addition, there were multiple hyper-pigmented macules on the patient’s palms and soles (FIGURE 2), and reticulated, patchy eruptions on his arms, chest (FIGURE 3), and back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis