User login

Widespread Erosions in Intertriginous Areas

The Diagnosis: Darier Disease

A clinical diagnosis of Darier disease was made from the skin findings of pruritic, malodorous, keratotic papules in a seborrheic distribution and pathognomonic nail dystrophy, along with a family history that demonstrated autosomal-dominant inheritance. The ulcerations were suspected to be caused by a superimposed herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the form of eczema herpeticum. The clinical diagnosis was later confirmed via punch biopsy. Pathology results demonstrated focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, which was consistent with Darier disease given the focal nature and lack of acanthosis. The patient’s father and sister also were confirmed to have Darier disease by an outside dermatologist.

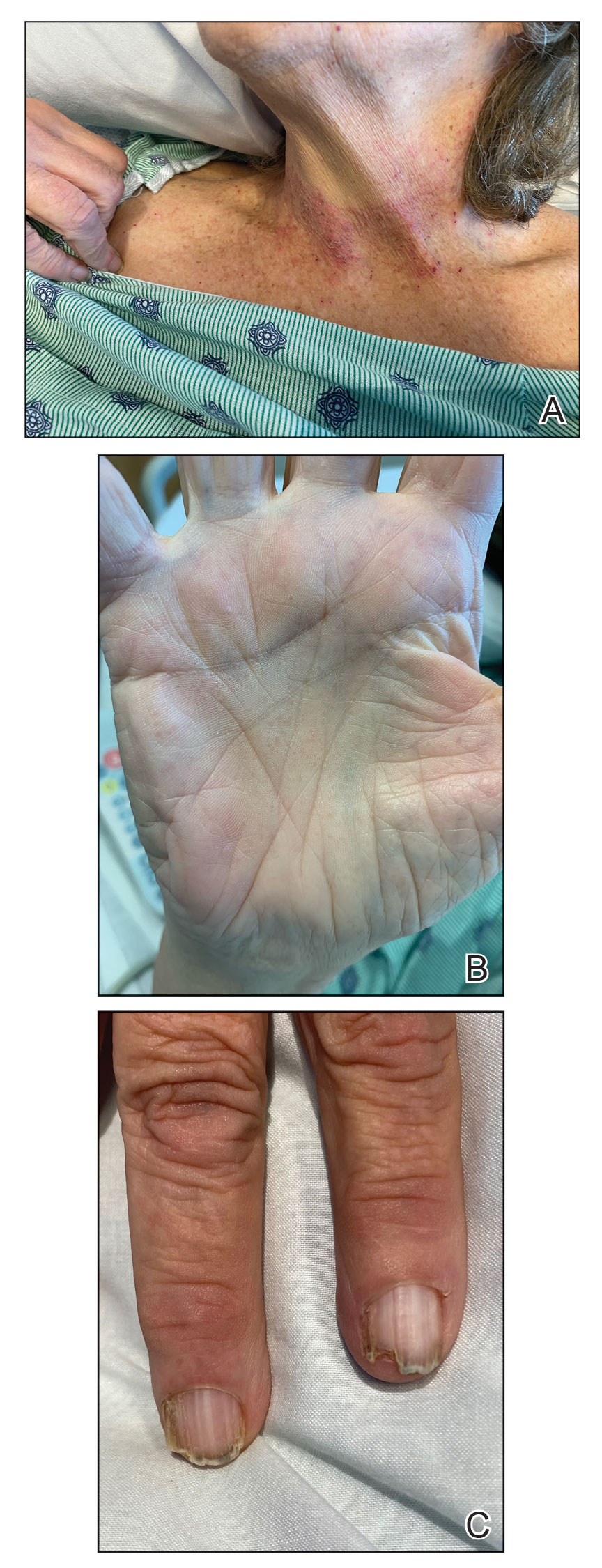

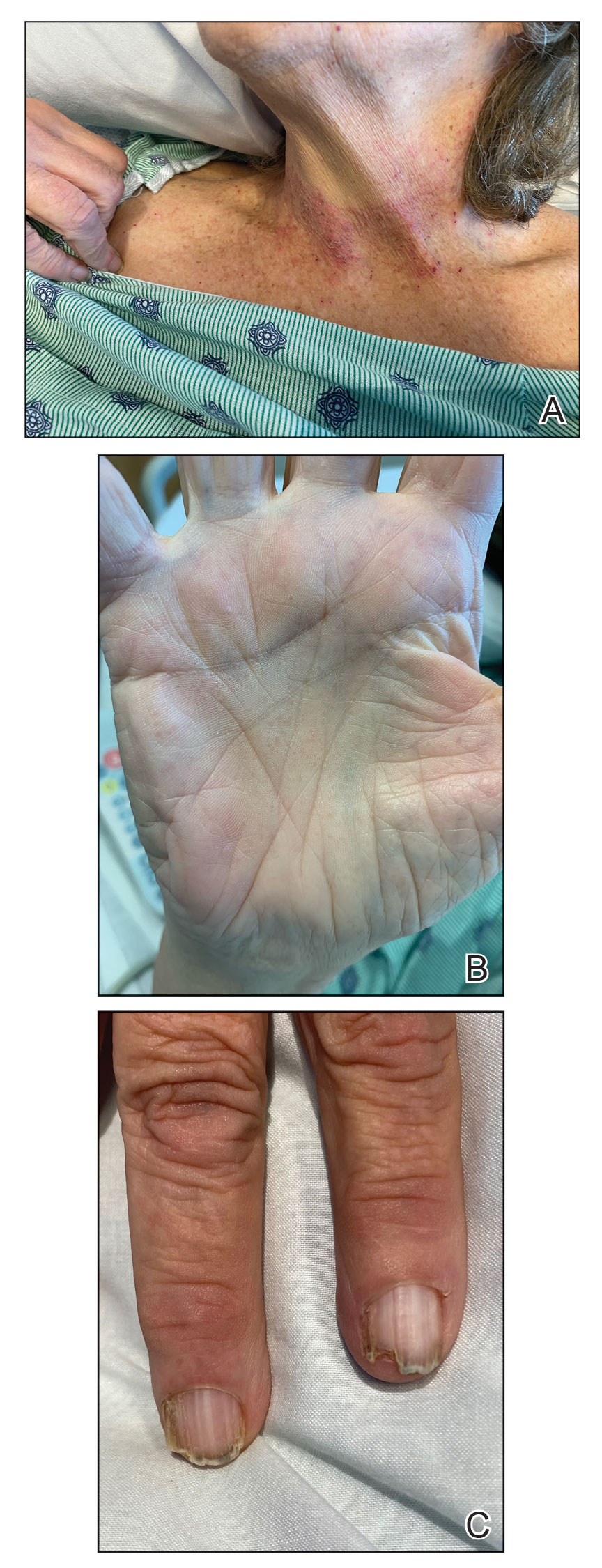

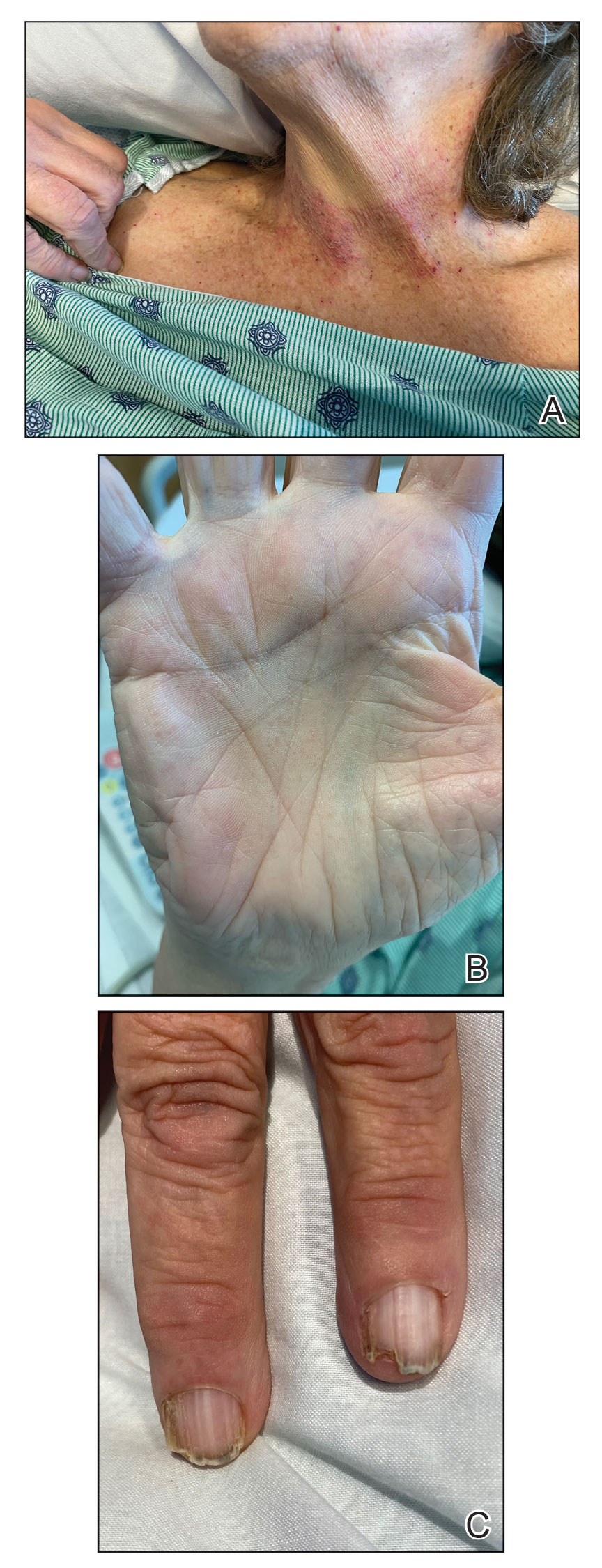

Darier disease is a rare keratinizing autosomaldominant genodermatosis that occurs due to a mutation in the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump that decreases cell adhesion between keratinocytes, leading to epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis and ultimately a disrupted skin barrier.1,2 Darier disease often presents in childhood and adolescence with papules in a seborrheic distribution on the central chest and back (Figure, A); the intertriginous folds also may be involved. Darier disease can manifest with palmoplantar pits (Figure, B), a cobblestonelike texture of the oral mucosa, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and nail findings with alternating red and white longitudinal streaks in the nail bed resembling a candy cane along with characteristic V nicking deformities of the nails themselves (Figure, C). Chronic flares may occur throughout one’s lifetime, with patients experiencing more symptoms in the summer months due to heat, sweat, and UV light exposure, as well as infections that irritate the skin and worsen dyskeratosis. Studies have revealed an association between Darier disease and neuropsychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.3,4

The skin barrier is compromised in patients with Darier disease, thereby making secondary infection more likely to occur. Polymerase chain reaction swabs of our patient’s purulent ulcerations were positive for HSV type 1, further strengthening a diagnosis of secondary eczema herpeticum, which occurs when patients have widespread HSV superinfecting pre-existing skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, and Hailey-Hailey disease.5-7 The lesions are characterized by a monomorphic eruption of umbilicated vesicles on an erythematous base. Lesions can progress to punched-out ulcers and erosions with hemorrhagic crusts that coalesce, forming scalloped borders, similar to our patient’s presentation.8

Hailey-Hailey disease, a genodermatosis that alters calcium signaling with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, was unlikely in our patient due to the presence of nail abnormalities and palmar pits that are characteristic of Darier disease. From a purely histopathologic standpoint, Grover disease was considered with skin biopsy demonstrating acantholytic dyskeratosis but was not compatible with the clinical context. Furthermore, trials of antibiotics with group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus coverage failed in our patient, and she lacked systemic symptoms that would be supportive of a cellulitis diagnosis. The punched-out lesions suggested that an isolated exacerbation of atopic dermatitis was not sufficient to explain all of the clinical findings.

Eczema herpeticum must be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with underlying Darier disease and widespread ulcerations. Our patient had more recent punched-out ulcerations in the intertriginous regions, with other areas showing later stages of confluent ulcers with scalloped borders. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of eczema herpeticum combined with severe Darier disease can lead to increased risk for hospitalization and rarely fatality.8,9

Our patient was started on intravenous acyclovir until the lesions crusted and then was transitioned to a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir given the widespread distribution. The Darier disease itself was managed with topical steroids and a zinc oxide barrier, serving as protectants to pathogens through microscopic breaks in the skin. Our patient also had a mild case of candidal intertrigo that was exacerbated by obesity and managed with topical ketoconazole. Gabapentin, hydromorphone, and acetaminophen were used for pain. She was discharged 10 days after admission with substantial improvement of both the HSV lesions and the irritation from her Darier disease. At follow-up visits 20 days later and again 6 months after discharge, she had been feeling well without any HSV flares.

The eczema herpeticum likely arose from our patient’s chronic skin barrier impairment attributed to Darier disease, leading to the cutaneous inoculation of HSV. Our patient and her family members had never been evaluated by a dermatologist until late in life during this hospitalization. Medication compliance with a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir and topical steroids is vital to prevent flares of both eczema herpeticum and Darier disease, respectively. This case highlights the importance of dermatology consultation for complex cutaneous findings, as delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

- Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304020-00003

- Dhitavat J, Cobbold C, Leslie N, et al. Impaired trafficking of the desmoplakins in cultured Darier’s disease keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1349-1355. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12557.x

- Nakamura T, Kazuno AA, Nakajima K, et al. Loss of function mutations in ATP2A2 and psychoses: a case report and literature survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:342-350. doi:10.1111/pcn.12395

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Hemani SA, Edmond MB, Jaggi P, et al. Frequency and clinical features associated with eczema herpeticum in hospitalized children with presumed atopic dermatitis skin infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:263-266. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002542

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347-350. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Nikkels AF, Beauthier F, Quatresooz P, et al. Fatal herpes simplex virus infection in Darier disease under corticotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:293-297.

- Vogt KA, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in patients with Darier disease: a 20-year retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:481-484. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.001

The Diagnosis: Darier Disease

A clinical diagnosis of Darier disease was made from the skin findings of pruritic, malodorous, keratotic papules in a seborrheic distribution and pathognomonic nail dystrophy, along with a family history that demonstrated autosomal-dominant inheritance. The ulcerations were suspected to be caused by a superimposed herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the form of eczema herpeticum. The clinical diagnosis was later confirmed via punch biopsy. Pathology results demonstrated focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, which was consistent with Darier disease given the focal nature and lack of acanthosis. The patient’s father and sister also were confirmed to have Darier disease by an outside dermatologist.

Darier disease is a rare keratinizing autosomaldominant genodermatosis that occurs due to a mutation in the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump that decreases cell adhesion between keratinocytes, leading to epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis and ultimately a disrupted skin barrier.1,2 Darier disease often presents in childhood and adolescence with papules in a seborrheic distribution on the central chest and back (Figure, A); the intertriginous folds also may be involved. Darier disease can manifest with palmoplantar pits (Figure, B), a cobblestonelike texture of the oral mucosa, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and nail findings with alternating red and white longitudinal streaks in the nail bed resembling a candy cane along with characteristic V nicking deformities of the nails themselves (Figure, C). Chronic flares may occur throughout one’s lifetime, with patients experiencing more symptoms in the summer months due to heat, sweat, and UV light exposure, as well as infections that irritate the skin and worsen dyskeratosis. Studies have revealed an association between Darier disease and neuropsychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.3,4

The skin barrier is compromised in patients with Darier disease, thereby making secondary infection more likely to occur. Polymerase chain reaction swabs of our patient’s purulent ulcerations were positive for HSV type 1, further strengthening a diagnosis of secondary eczema herpeticum, which occurs when patients have widespread HSV superinfecting pre-existing skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, and Hailey-Hailey disease.5-7 The lesions are characterized by a monomorphic eruption of umbilicated vesicles on an erythematous base. Lesions can progress to punched-out ulcers and erosions with hemorrhagic crusts that coalesce, forming scalloped borders, similar to our patient’s presentation.8

Hailey-Hailey disease, a genodermatosis that alters calcium signaling with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, was unlikely in our patient due to the presence of nail abnormalities and palmar pits that are characteristic of Darier disease. From a purely histopathologic standpoint, Grover disease was considered with skin biopsy demonstrating acantholytic dyskeratosis but was not compatible with the clinical context. Furthermore, trials of antibiotics with group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus coverage failed in our patient, and she lacked systemic symptoms that would be supportive of a cellulitis diagnosis. The punched-out lesions suggested that an isolated exacerbation of atopic dermatitis was not sufficient to explain all of the clinical findings.

Eczema herpeticum must be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with underlying Darier disease and widespread ulcerations. Our patient had more recent punched-out ulcerations in the intertriginous regions, with other areas showing later stages of confluent ulcers with scalloped borders. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of eczema herpeticum combined with severe Darier disease can lead to increased risk for hospitalization and rarely fatality.8,9

Our patient was started on intravenous acyclovir until the lesions crusted and then was transitioned to a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir given the widespread distribution. The Darier disease itself was managed with topical steroids and a zinc oxide barrier, serving as protectants to pathogens through microscopic breaks in the skin. Our patient also had a mild case of candidal intertrigo that was exacerbated by obesity and managed with topical ketoconazole. Gabapentin, hydromorphone, and acetaminophen were used for pain. She was discharged 10 days after admission with substantial improvement of both the HSV lesions and the irritation from her Darier disease. At follow-up visits 20 days later and again 6 months after discharge, she had been feeling well without any HSV flares.

The eczema herpeticum likely arose from our patient’s chronic skin barrier impairment attributed to Darier disease, leading to the cutaneous inoculation of HSV. Our patient and her family members had never been evaluated by a dermatologist until late in life during this hospitalization. Medication compliance with a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir and topical steroids is vital to prevent flares of both eczema herpeticum and Darier disease, respectively. This case highlights the importance of dermatology consultation for complex cutaneous findings, as delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

The Diagnosis: Darier Disease

A clinical diagnosis of Darier disease was made from the skin findings of pruritic, malodorous, keratotic papules in a seborrheic distribution and pathognomonic nail dystrophy, along with a family history that demonstrated autosomal-dominant inheritance. The ulcerations were suspected to be caused by a superimposed herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the form of eczema herpeticum. The clinical diagnosis was later confirmed via punch biopsy. Pathology results demonstrated focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, which was consistent with Darier disease given the focal nature and lack of acanthosis. The patient’s father and sister also were confirmed to have Darier disease by an outside dermatologist.

Darier disease is a rare keratinizing autosomaldominant genodermatosis that occurs due to a mutation in the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump that decreases cell adhesion between keratinocytes, leading to epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis and ultimately a disrupted skin barrier.1,2 Darier disease often presents in childhood and adolescence with papules in a seborrheic distribution on the central chest and back (Figure, A); the intertriginous folds also may be involved. Darier disease can manifest with palmoplantar pits (Figure, B), a cobblestonelike texture of the oral mucosa, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and nail findings with alternating red and white longitudinal streaks in the nail bed resembling a candy cane along with characteristic V nicking deformities of the nails themselves (Figure, C). Chronic flares may occur throughout one’s lifetime, with patients experiencing more symptoms in the summer months due to heat, sweat, and UV light exposure, as well as infections that irritate the skin and worsen dyskeratosis. Studies have revealed an association between Darier disease and neuropsychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.3,4

The skin barrier is compromised in patients with Darier disease, thereby making secondary infection more likely to occur. Polymerase chain reaction swabs of our patient’s purulent ulcerations were positive for HSV type 1, further strengthening a diagnosis of secondary eczema herpeticum, which occurs when patients have widespread HSV superinfecting pre-existing skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, and Hailey-Hailey disease.5-7 The lesions are characterized by a monomorphic eruption of umbilicated vesicles on an erythematous base. Lesions can progress to punched-out ulcers and erosions with hemorrhagic crusts that coalesce, forming scalloped borders, similar to our patient’s presentation.8

Hailey-Hailey disease, a genodermatosis that alters calcium signaling with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, was unlikely in our patient due to the presence of nail abnormalities and palmar pits that are characteristic of Darier disease. From a purely histopathologic standpoint, Grover disease was considered with skin biopsy demonstrating acantholytic dyskeratosis but was not compatible with the clinical context. Furthermore, trials of antibiotics with group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus coverage failed in our patient, and she lacked systemic symptoms that would be supportive of a cellulitis diagnosis. The punched-out lesions suggested that an isolated exacerbation of atopic dermatitis was not sufficient to explain all of the clinical findings.

Eczema herpeticum must be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with underlying Darier disease and widespread ulcerations. Our patient had more recent punched-out ulcerations in the intertriginous regions, with other areas showing later stages of confluent ulcers with scalloped borders. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of eczema herpeticum combined with severe Darier disease can lead to increased risk for hospitalization and rarely fatality.8,9

Our patient was started on intravenous acyclovir until the lesions crusted and then was transitioned to a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir given the widespread distribution. The Darier disease itself was managed with topical steroids and a zinc oxide barrier, serving as protectants to pathogens through microscopic breaks in the skin. Our patient also had a mild case of candidal intertrigo that was exacerbated by obesity and managed with topical ketoconazole. Gabapentin, hydromorphone, and acetaminophen were used for pain. She was discharged 10 days after admission with substantial improvement of both the HSV lesions and the irritation from her Darier disease. At follow-up visits 20 days later and again 6 months after discharge, she had been feeling well without any HSV flares.

The eczema herpeticum likely arose from our patient’s chronic skin barrier impairment attributed to Darier disease, leading to the cutaneous inoculation of HSV. Our patient and her family members had never been evaluated by a dermatologist until late in life during this hospitalization. Medication compliance with a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir and topical steroids is vital to prevent flares of both eczema herpeticum and Darier disease, respectively. This case highlights the importance of dermatology consultation for complex cutaneous findings, as delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

- Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304020-00003

- Dhitavat J, Cobbold C, Leslie N, et al. Impaired trafficking of the desmoplakins in cultured Darier’s disease keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1349-1355. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12557.x

- Nakamura T, Kazuno AA, Nakajima K, et al. Loss of function mutations in ATP2A2 and psychoses: a case report and literature survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:342-350. doi:10.1111/pcn.12395

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Hemani SA, Edmond MB, Jaggi P, et al. Frequency and clinical features associated with eczema herpeticum in hospitalized children with presumed atopic dermatitis skin infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:263-266. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002542

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347-350. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Nikkels AF, Beauthier F, Quatresooz P, et al. Fatal herpes simplex virus infection in Darier disease under corticotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:293-297.

- Vogt KA, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in patients with Darier disease: a 20-year retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:481-484. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.001

- Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304020-00003

- Dhitavat J, Cobbold C, Leslie N, et al. Impaired trafficking of the desmoplakins in cultured Darier’s disease keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1349-1355. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12557.x

- Nakamura T, Kazuno AA, Nakajima K, et al. Loss of function mutations in ATP2A2 and psychoses: a case report and literature survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:342-350. doi:10.1111/pcn.12395

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Hemani SA, Edmond MB, Jaggi P, et al. Frequency and clinical features associated with eczema herpeticum in hospitalized children with presumed atopic dermatitis skin infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:263-266. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002542

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347-350. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Nikkels AF, Beauthier F, Quatresooz P, et al. Fatal herpes simplex virus infection in Darier disease under corticotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:293-297.

- Vogt KA, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in patients with Darier disease: a 20-year retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:481-484. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.001

A 72-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with painful, erythematic, pruritic, and purulent lesions in intertriginous regions including the inframammary, infra-abdominal, and inguinal folds with a burning sensation of 1 week’s duration. Her medical history was notable for obesity and major depressive disorder. She was empirically treated for cellulitis, but there was no improvement with cefazolin or clindamycin. Dermatology was consulted. Physical examination revealed gray-brown, slightly umbilicated papules in the inframammary region that were malodorous upon lifting the folds. Grouped, punched-out ulcerations with scalloped borders were superimposed onto these papules. Further examination revealed a macerated erythematous plaque in the infra-abdominal and inguinal regions with punched-out ulcers. Hemecrusted papules were observed in seborrheic areas including the anterior neck, hairline, and trunk. Few subtle keratotic pits were localized on the palms. She reported similar flares in the past but never saw a dermatologist and noted that her father and sister had similar papules in a seborrheic distribution. Nail abnormalities included red and white alternating subungual streaks with irregular texture including V nicking of the distal nails.

DRESS Syndrome: How to Approach Systemic Workup, Treatment, and Long-term Follow-up

DRESS Syndrome: Clinical Myths and Pearls

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

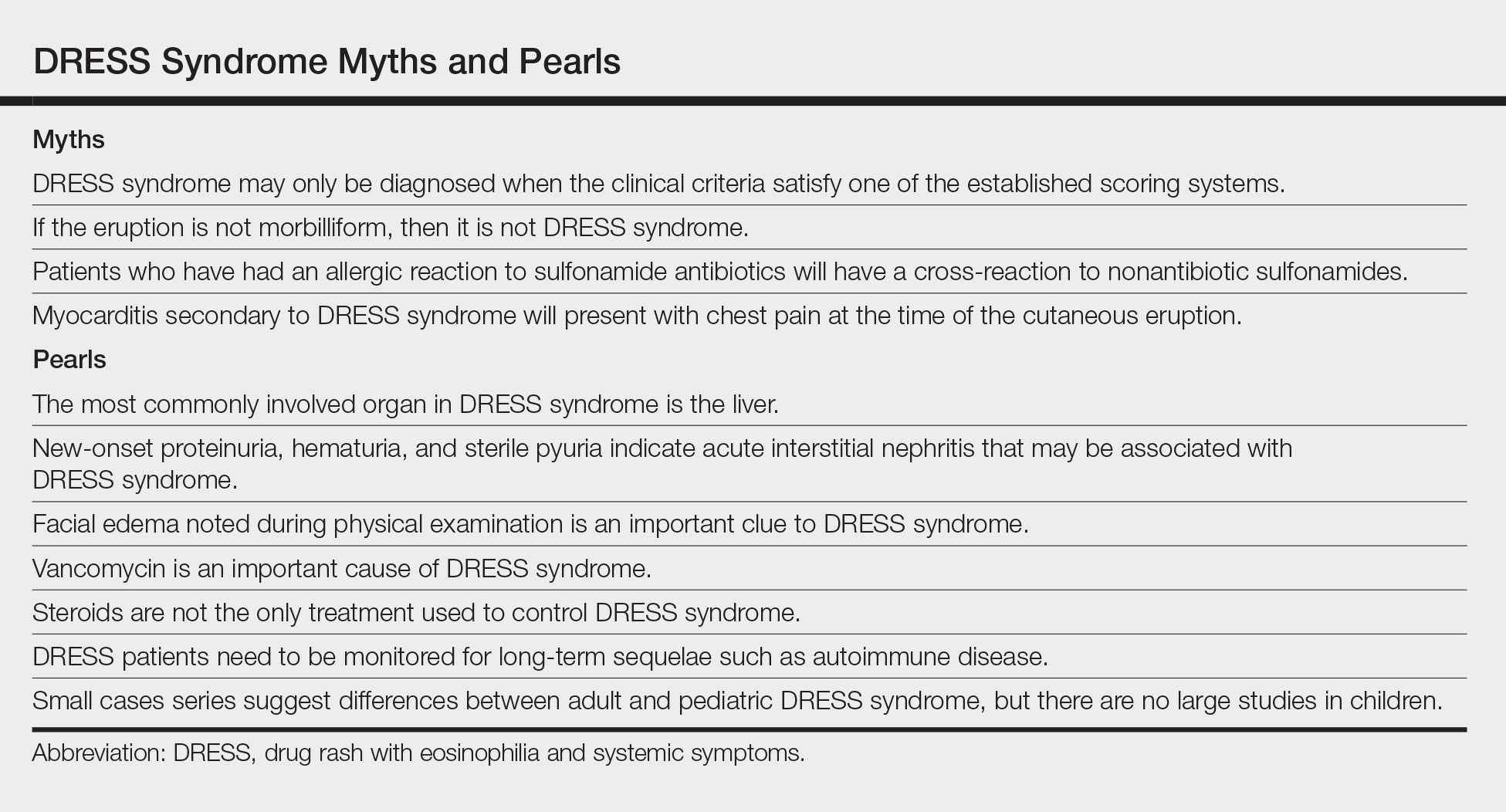

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

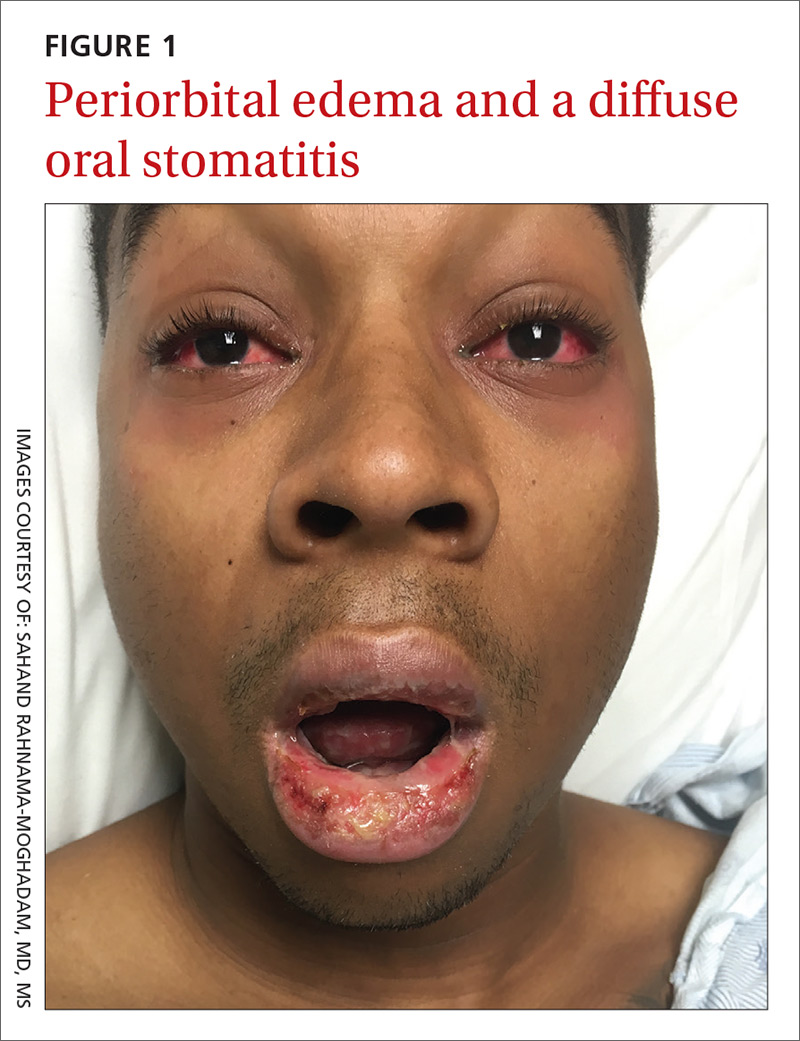

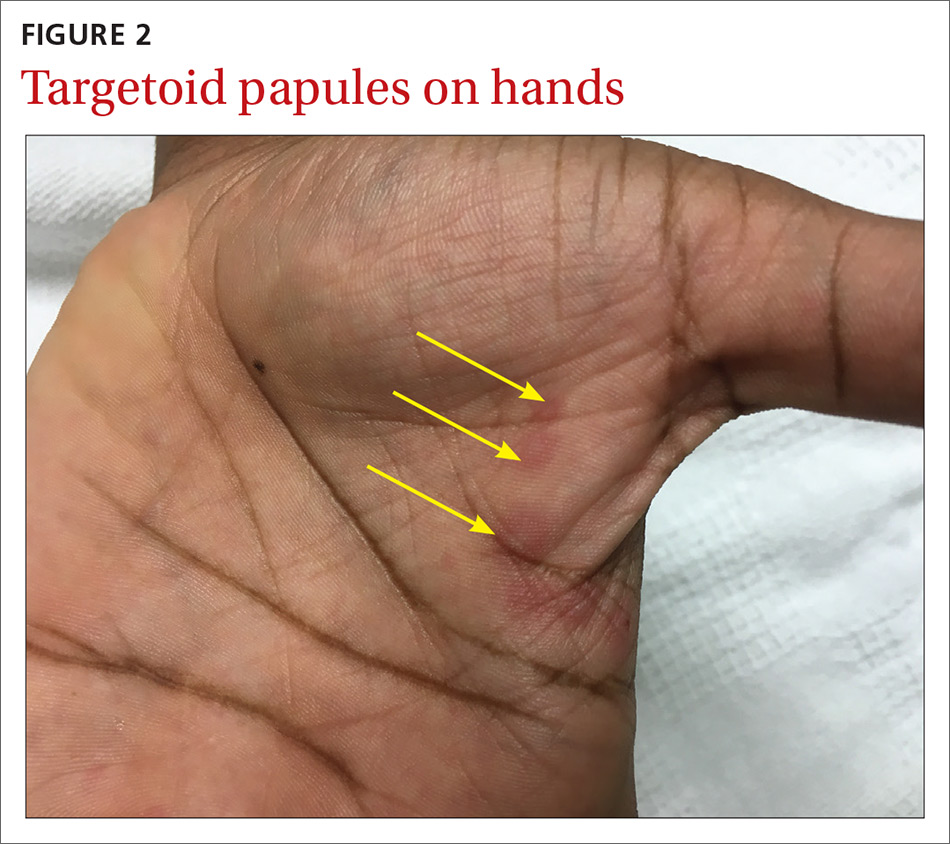

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13

Myth: Patients who have had an allergic reaction to sulfonamide antibiotics will have a cross-reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides.

A common question is, if a patient has had a prior allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, then are nonantibiotic sulfones such as a sulfonylurea, thiazide diuretic, or furosemide likely to cause a a cross-reaction? In one study (N=969), only 9.9% of patients with a prior sulfone antibiotic allergy developed hypersensitivity when exposed to a nonantibiotic sulfone, which is thought to be due to an overall increased propensity for hypersensitivity rather than a true cross-reaction. In fact, the risk for developing a hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (14.0% [717/5115]) was higher than the risk for developing a reaction from a nonantibiotic sulfone among these patients.14 This study bolsters the argument that if there are other potential culprit medications and the time course for a patient’s nonantibiotic sulfone is not consistent with the timeline for DRESS syndrome, it may be beneficial to look for a different causative agent.

Pearl: Vancomycin is an important cause of DRESS syndrome.

Guidelines for treating endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection recommend intravenous vancomycin for 4 to 6 weeks.15 This duration is within the relevant time frame of exposure for the development of DRESS syndrome de novo.

One case series noted that 37.5% (12/32) of DRESS syndrome cases in a 3-year period were caused by vancomycin, which notably was the most common medication associated with DRESS syndrome.16 There were caveats to this case series in that no standardized drug causality score was used and the sample size over the 3-year period was small; however, the increased use (and misuse) of antibiotics and perhaps increased recognition of rash in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics may play a role if vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome is indeed becoming more common.

Myth: Myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome will present with chest pain at the time of the cutaneous eruption.

Few patients with DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis actually are symptomatic during their hospitalization.4 In asymptomatic patients, the primary team and consultants should be vigilant for the potential of subclinical myocarditis or the possibility of developing cardiac involvement after discharge, as myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome may present any time from rash onset up to 4 months later.4 Therefore, DRESS patients should be especially attentive to any new cardiac symptoms and notify their provider if any develop.

Although no standard cardiac screening guidelines exist for DRESS syndrome, some have recommended that baseline cardiac screening tests including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, and echocardiogram be considered at the time of diagnosis.5 If any testing is abnormal, DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis should be suspected and an endomyocardial biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, may be necessary.4 If the cardiac screening tests are normal, some investigators recommend serial outpatient echocardiograms for all DRESS patients, even those who remain asymptomatic.17 An alternative is an empiric approach in which a thorough review of systems is performed and testing is done if patients develop symptoms that are concerning for myocarditis.

Pearl: Steroids are not the only treatment used to control DRESS syndrome.

A prolonged taper of systemic steroids is the first-line treatment of DRESS syndrome. Steroids at the equivalent of 1 to 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) of prednisone typically are used. For severe and/or recalcitrant DRESS syndrome, 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) typically is used, and less than 1 mg/kg daily may be used for mini-DRESS syndrome.

Clinical improvement of DRESS syndrome has been demonstrated in several case reports with intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis.18-21 Each of these therapies typically were initiated as second-line therapeutic agents when initial treatment with steroids failed. It is important to note that large prospective studies regarding these treatments are lacking; however, there have been case reports of acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis that did not respond to the combination of steroids and cyclosporine.4,22

Although there have been successful case reports using intravenous immunoglobulin, a 2012 prospective open-label clinical trial reported notable side effects in 5 of 6 (83.3%) patients with only 1 of 6 (16.6%) achieving the primary end point of control of fever/symptoms at day 7 and clinical remission without steroids on day 30.23

Pearl: DRESS patients need to be monitored for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disease.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as a delayed complication of DRESS syndrome, including autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.24-26 Incidence rates of autoimmunity following DRESS syndrome range from 3% to 5% among small case series.24,25

Autoimmune thyroiditis, which may present as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or painless thyroiditis, is the most common autoimmune disorder to develop in DRESS patients and appears from several weeks to up to 3 years after DRESS.24 Therefore, all DRESS patients should be monitored longitudinally for several years for signs or symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune condition.5,24,26

Because no guidelines exist regarding serial monitoring for autoimmune sequelae, it may be reasonable to check thyroid function tests at the time of diagnosis and regularly for at least 2 years after diagnosis.5 Alternatively, clinicians may consider an empiric approach to laboratory testing that is guided by the development of clinical symptoms.

Pearl: Small cases series suggest differences between adult and pediatric DRESS syndrome, but there are no large studies in children.

Small case series have suggested there may be noteworthy differences between DRESS syndrome in adults and children. Although human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) positivity in DRESS syndrome in adults may be as high as 80%, 13% of pediatric patients in one cohort tested positive for HHV-6, though the study size was limited at 29 total patients.27 In children, DRESS syndrome secondary to antibiotics was associated with a shorter latency time as compared to cases secondary to nonantibiotics. In contrast to the typical 2- to 6-week timeline, Sasidharanpillai et al28 reported an average onset 5.8 days after drug administration in antibiotic-associated DRESS syndrome compared to 23.9 days for anticonvulsants, though this study only included 11 total patients. Other reports have suggested a similar trend.27

The role of HHV-6 positivity in pediatric DRESS syndrome and its influence on prognosis remains unclear. One study showed a worse prognosis for pediatric patients with positive HHV-6 antibodies.27 However, with such a small sample size—only 4 HHV-6–positive patients of 29 pediatric DRESS cases—larger studies are needed to better characterize the relationship between HHV-6 positivity and prognosis.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med, 2011;124:588-597.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Intarasupht J, Kanchanomai A, Leelasattakul W, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and mortality outcome in the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients with cardiac involvement. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1187-1191.

- Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, et al. A review of DRESS-associated myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E229-E236.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-693.e14; quiz 706-708.

- Lee T, Lee YS, Yoon SY, et al. Characteristics of liver injury in drug-induced systemic hypersensitivity reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:407-415.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422-428.

- Walsh S, Diaz-Cano S, Higgins E, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? a review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:149-162.

- Matsuda H, Saito K, Takayanagi Y, et al. Pustular-type drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to carbamazepine with systemic muscle involvement. J Dermatol. 2013;40:118-122.

- Wolf R, Davidovici B, Matz H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms versus Stevens-Johnson Syndrome—a case that indicates a stumbling block in the current classification. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:308-310.

- Kumar A, Goldfarb JW, Bittner EA. A case of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome complicating airway management. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:295-298.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1628-1635.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:E26-E46.

- Lam BD, Miller MM, Sutton AV, et al. Vancomycin and DRESS: a retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-975.

- Eppenberger M, Hack D, Ammann P, et al. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis with dramatic response to steroid therapy: the central role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow-up. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:326-330.

- Kirchhof MG, Wong A, Dutz JP. Cyclosporine treatment of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1254-1257.

- Singer EM, Wanat KA, Rosenbach MA. A case of recalcitrant DRESS syndrome with multiple autoimmune sequelae treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:494-495.

- Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, et al. Management of psychotropic drug-induced DRESS syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:787-801.

- Alexander T, Iglesia E, Park Y, et al. Severe DRESS syndrome managed with therapeutic plasma exchange. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E945-E949.

- Daoulah A, Alqahtani AA, Ocheltree SR, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 56-year-old female patient treated with sulfasalazine. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:638.e1-638.e3.

- Joly P, Janela B, Tetart F, et al. Poor benefit/risk balance of intravenous immunoglobulins in DRESS. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:543-544.

- Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42:276-282.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:721-728.

- Matta JM, Flores SM, Cherit JD. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and its relation with autoimmunity in a reference center in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:30-33.

- Ahluwalia J, Abuabara K, Perman MJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 involvement in paediatric drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1090-1095.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13

Myth: Patients who have had an allergic reaction to sulfonamide antibiotics will have a cross-reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides.

A common question is, if a patient has had a prior allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, then are nonantibiotic sulfones such as a sulfonylurea, thiazide diuretic, or furosemide likely to cause a a cross-reaction? In one study (N=969), only 9.9% of patients with a prior sulfone antibiotic allergy developed hypersensitivity when exposed to a nonantibiotic sulfone, which is thought to be due to an overall increased propensity for hypersensitivity rather than a true cross-reaction. In fact, the risk for developing a hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (14.0% [717/5115]) was higher than the risk for developing a reaction from a nonantibiotic sulfone among these patients.14 This study bolsters the argument that if there are other potential culprit medications and the time course for a patient’s nonantibiotic sulfone is not consistent with the timeline for DRESS syndrome, it may be beneficial to look for a different causative agent.

Pearl: Vancomycin is an important cause of DRESS syndrome.

Guidelines for treating endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection recommend intravenous vancomycin for 4 to 6 weeks.15 This duration is within the relevant time frame of exposure for the development of DRESS syndrome de novo.

One case series noted that 37.5% (12/32) of DRESS syndrome cases in a 3-year period were caused by vancomycin, which notably was the most common medication associated with DRESS syndrome.16 There were caveats to this case series in that no standardized drug causality score was used and the sample size over the 3-year period was small; however, the increased use (and misuse) of antibiotics and perhaps increased recognition of rash in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics may play a role if vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome is indeed becoming more common.

Myth: Myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome will present with chest pain at the time of the cutaneous eruption.

Few patients with DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis actually are symptomatic during their hospitalization.4 In asymptomatic patients, the primary team and consultants should be vigilant for the potential of subclinical myocarditis or the possibility of developing cardiac involvement after discharge, as myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome may present any time from rash onset up to 4 months later.4 Therefore, DRESS patients should be especially attentive to any new cardiac symptoms and notify their provider if any develop.

Although no standard cardiac screening guidelines exist for DRESS syndrome, some have recommended that baseline cardiac screening tests including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, and echocardiogram be considered at the time of diagnosis.5 If any testing is abnormal, DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis should be suspected and an endomyocardial biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, may be necessary.4 If the cardiac screening tests are normal, some investigators recommend serial outpatient echocardiograms for all DRESS patients, even those who remain asymptomatic.17 An alternative is an empiric approach in which a thorough review of systems is performed and testing is done if patients develop symptoms that are concerning for myocarditis.

Pearl: Steroids are not the only treatment used to control DRESS syndrome.

A prolonged taper of systemic steroids is the first-line treatment of DRESS syndrome. Steroids at the equivalent of 1 to 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) of prednisone typically are used. For severe and/or recalcitrant DRESS syndrome, 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) typically is used, and less than 1 mg/kg daily may be used for mini-DRESS syndrome.

Clinical improvement of DRESS syndrome has been demonstrated in several case reports with intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis.18-21 Each of these therapies typically were initiated as second-line therapeutic agents when initial treatment with steroids failed. It is important to note that large prospective studies regarding these treatments are lacking; however, there have been case reports of acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis that did not respond to the combination of steroids and cyclosporine.4,22

Although there have been successful case reports using intravenous immunoglobulin, a 2012 prospective open-label clinical trial reported notable side effects in 5 of 6 (83.3%) patients with only 1 of 6 (16.6%) achieving the primary end point of control of fever/symptoms at day 7 and clinical remission without steroids on day 30.23

Pearl: DRESS patients need to be monitored for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disease.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as a delayed complication of DRESS syndrome, including autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.24-26 Incidence rates of autoimmunity following DRESS syndrome range from 3% to 5% among small case series.24,25

Autoimmune thyroiditis, which may present as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or painless thyroiditis, is the most common autoimmune disorder to develop in DRESS patients and appears from several weeks to up to 3 years after DRESS.24 Therefore, all DRESS patients should be monitored longitudinally for several years for signs or symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune condition.5,24,26

Because no guidelines exist regarding serial monitoring for autoimmune sequelae, it may be reasonable to check thyroid function tests at the time of diagnosis and regularly for at least 2 years after diagnosis.5 Alternatively, clinicians may consider an empiric approach to laboratory testing that is guided by the development of clinical symptoms.

Pearl: Small cases series suggest differences between adult and pediatric DRESS syndrome, but there are no large studies in children.

Small case series have suggested there may be noteworthy differences between DRESS syndrome in adults and children. Although human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) positivity in DRESS syndrome in adults may be as high as 80%, 13% of pediatric patients in one cohort tested positive for HHV-6, though the study size was limited at 29 total patients.27 In children, DRESS syndrome secondary to antibiotics was associated with a shorter latency time as compared to cases secondary to nonantibiotics. In contrast to the typical 2- to 6-week timeline, Sasidharanpillai et al28 reported an average onset 5.8 days after drug administration in antibiotic-associated DRESS syndrome compared to 23.9 days for anticonvulsants, though this study only included 11 total patients. Other reports have suggested a similar trend.27

The role of HHV-6 positivity in pediatric DRESS syndrome and its influence on prognosis remains unclear. One study showed a worse prognosis for pediatric patients with positive HHV-6 antibodies.27 However, with such a small sample size—only 4 HHV-6–positive patients of 29 pediatric DRESS cases—larger studies are needed to better characterize the relationship between HHV-6 positivity and prognosis.

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13

Myth: Patients who have had an allergic reaction to sulfonamide antibiotics will have a cross-reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides.

A common question is, if a patient has had a prior allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, then are nonantibiotic sulfones such as a sulfonylurea, thiazide diuretic, or furosemide likely to cause a a cross-reaction? In one study (N=969), only 9.9% of patients with a prior sulfone antibiotic allergy developed hypersensitivity when exposed to a nonantibiotic sulfone, which is thought to be due to an overall increased propensity for hypersensitivity rather than a true cross-reaction. In fact, the risk for developing a hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (14.0% [717/5115]) was higher than the risk for developing a reaction from a nonantibiotic sulfone among these patients.14 This study bolsters the argument that if there are other potential culprit medications and the time course for a patient’s nonantibiotic sulfone is not consistent with the timeline for DRESS syndrome, it may be beneficial to look for a different causative agent.

Pearl: Vancomycin is an important cause of DRESS syndrome.

Guidelines for treating endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection recommend intravenous vancomycin for 4 to 6 weeks.15 This duration is within the relevant time frame of exposure for the development of DRESS syndrome de novo.

One case series noted that 37.5% (12/32) of DRESS syndrome cases in a 3-year period were caused by vancomycin, which notably was the most common medication associated with DRESS syndrome.16 There were caveats to this case series in that no standardized drug causality score was used and the sample size over the 3-year period was small; however, the increased use (and misuse) of antibiotics and perhaps increased recognition of rash in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics may play a role if vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome is indeed becoming more common.

Myth: Myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome will present with chest pain at the time of the cutaneous eruption.

Few patients with DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis actually are symptomatic during their hospitalization.4 In asymptomatic patients, the primary team and consultants should be vigilant for the potential of subclinical myocarditis or the possibility of developing cardiac involvement after discharge, as myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome may present any time from rash onset up to 4 months later.4 Therefore, DRESS patients should be especially attentive to any new cardiac symptoms and notify their provider if any develop.

Although no standard cardiac screening guidelines exist for DRESS syndrome, some have recommended that baseline cardiac screening tests including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, and echocardiogram be considered at the time of diagnosis.5 If any testing is abnormal, DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis should be suspected and an endomyocardial biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, may be necessary.4 If the cardiac screening tests are normal, some investigators recommend serial outpatient echocardiograms for all DRESS patients, even those who remain asymptomatic.17 An alternative is an empiric approach in which a thorough review of systems is performed and testing is done if patients develop symptoms that are concerning for myocarditis.

Pearl: Steroids are not the only treatment used to control DRESS syndrome.

A prolonged taper of systemic steroids is the first-line treatment of DRESS syndrome. Steroids at the equivalent of 1 to 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) of prednisone typically are used. For severe and/or recalcitrant DRESS syndrome, 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) typically is used, and less than 1 mg/kg daily may be used for mini-DRESS syndrome.

Clinical improvement of DRESS syndrome has been demonstrated in several case reports with intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis.18-21 Each of these therapies typically were initiated as second-line therapeutic agents when initial treatment with steroids failed. It is important to note that large prospective studies regarding these treatments are lacking; however, there have been case reports of acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis that did not respond to the combination of steroids and cyclosporine.4,22

Although there have been successful case reports using intravenous immunoglobulin, a 2012 prospective open-label clinical trial reported notable side effects in 5 of 6 (83.3%) patients with only 1 of 6 (16.6%) achieving the primary end point of control of fever/symptoms at day 7 and clinical remission without steroids on day 30.23

Pearl: DRESS patients need to be monitored for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disease.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as a delayed complication of DRESS syndrome, including autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.24-26 Incidence rates of autoimmunity following DRESS syndrome range from 3% to 5% among small case series.24,25

Autoimmune thyroiditis, which may present as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or painless thyroiditis, is the most common autoimmune disorder to develop in DRESS patients and appears from several weeks to up to 3 years after DRESS.24 Therefore, all DRESS patients should be monitored longitudinally for several years for signs or symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune condition.5,24,26

Because no guidelines exist regarding serial monitoring for autoimmune sequelae, it may be reasonable to check thyroid function tests at the time of diagnosis and regularly for at least 2 years after diagnosis.5 Alternatively, clinicians may consider an empiric approach to laboratory testing that is guided by the development of clinical symptoms.

Pearl: Small cases series suggest differences between adult and pediatric DRESS syndrome, but there are no large studies in children.

Small case series have suggested there may be noteworthy differences between DRESS syndrome in adults and children. Although human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) positivity in DRESS syndrome in adults may be as high as 80%, 13% of pediatric patients in one cohort tested positive for HHV-6, though the study size was limited at 29 total patients.27 In children, DRESS syndrome secondary to antibiotics was associated with a shorter latency time as compared to cases secondary to nonantibiotics. In contrast to the typical 2- to 6-week timeline, Sasidharanpillai et al28 reported an average onset 5.8 days after drug administration in antibiotic-associated DRESS syndrome compared to 23.9 days for anticonvulsants, though this study only included 11 total patients. Other reports have suggested a similar trend.27

The role of HHV-6 positivity in pediatric DRESS syndrome and its influence on prognosis remains unclear. One study showed a worse prognosis for pediatric patients with positive HHV-6 antibodies.27 However, with such a small sample size—only 4 HHV-6–positive patients of 29 pediatric DRESS cases—larger studies are needed to better characterize the relationship between HHV-6 positivity and prognosis.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med, 2011;124:588-597.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Intarasupht J, Kanchanomai A, Leelasattakul W, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and mortality outcome in the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients with cardiac involvement. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1187-1191.

- Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, et al. A review of DRESS-associated myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E229-E236.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-693.e14; quiz 706-708.

- Lee T, Lee YS, Yoon SY, et al. Characteristics of liver injury in drug-induced systemic hypersensitivity reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:407-415.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422-428.

- Walsh S, Diaz-Cano S, Higgins E, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? a review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:149-162.

- Matsuda H, Saito K, Takayanagi Y, et al. Pustular-type drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to carbamazepine with systemic muscle involvement. J Dermatol. 2013;40:118-122.

- Wolf R, Davidovici B, Matz H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms versus Stevens-Johnson Syndrome—a case that indicates a stumbling block in the current classification. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:308-310.

- Kumar A, Goldfarb JW, Bittner EA. A case of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome complicating airway management. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:295-298.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1628-1635.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:E26-E46.

- Lam BD, Miller MM, Sutton AV, et al. Vancomycin and DRESS: a retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-975.

- Eppenberger M, Hack D, Ammann P, et al. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis with dramatic response to steroid therapy: the central role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow-up. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:326-330.

- Kirchhof MG, Wong A, Dutz JP. Cyclosporine treatment of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1254-1257.

- Singer EM, Wanat KA, Rosenbach MA. A case of recalcitrant DRESS syndrome with multiple autoimmune sequelae treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:494-495.

- Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, et al. Management of psychotropic drug-induced DRESS syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:787-801.

- Alexander T, Iglesia E, Park Y, et al. Severe DRESS syndrome managed with therapeutic plasma exchange. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E945-E949.

- Daoulah A, Alqahtani AA, Ocheltree SR, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 56-year-old female patient treated with sulfasalazine. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:638.e1-638.e3.

- Joly P, Janela B, Tetart F, et al. Poor benefit/risk balance of intravenous immunoglobulins in DRESS. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:543-544.

- Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42:276-282.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:721-728.

- Matta JM, Flores SM, Cherit JD. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and its relation with autoimmunity in a reference center in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:30-33.

- Ahluwalia J, Abuabara K, Perman MJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 involvement in paediatric drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1090-1095.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med, 2011;124:588-597.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Intarasupht J, Kanchanomai A, Leelasattakul W, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and mortality outcome in the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients with cardiac involvement. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1187-1191.

- Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, et al. A review of DRESS-associated myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E229-E236.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-693.e14; quiz 706-708.

- Lee T, Lee YS, Yoon SY, et al. Characteristics of liver injury in drug-induced systemic hypersensitivity reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:407-415.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422-428.

- Walsh S, Diaz-Cano S, Higgins E, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? a review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:149-162.

- Matsuda H, Saito K, Takayanagi Y, et al. Pustular-type drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to carbamazepine with systemic muscle involvement. J Dermatol. 2013;40:118-122.

- Wolf R, Davidovici B, Matz H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms versus Stevens-Johnson Syndrome—a case that indicates a stumbling block in the current classification. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:308-310.

- Kumar A, Goldfarb JW, Bittner EA. A case of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome complicating airway management. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:295-298.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1628-1635.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:E26-E46.

- Lam BD, Miller MM, Sutton AV, et al. Vancomycin and DRESS: a retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-975.

- Eppenberger M, Hack D, Ammann P, et al. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis with dramatic response to steroid therapy: the central role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow-up. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:326-330.

- Kirchhof MG, Wong A, Dutz JP. Cyclosporine treatment of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1254-1257.

- Singer EM, Wanat KA, Rosenbach MA. A case of recalcitrant DRESS syndrome with multiple autoimmune sequelae treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:494-495.

- Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, et al. Management of psychotropic drug-induced DRESS syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:787-801.

- Alexander T, Iglesia E, Park Y, et al. Severe DRESS syndrome managed with therapeutic plasma exchange. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E945-E949.

- Daoulah A, Alqahtani AA, Ocheltree SR, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 56-year-old female patient treated with sulfasalazine. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:638.e1-638.e3.

- Joly P, Janela B, Tetart F, et al. Poor benefit/risk balance of intravenous immunoglobulins in DRESS. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:543-544.

- Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42:276-282.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:721-728.

- Matta JM, Flores SM, Cherit JD. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and its relation with autoimmunity in a reference center in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:30-33.

- Ahluwalia J, Abuabara K, Perman MJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 involvement in paediatric drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1090-1095.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

Practice Points

- Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome) is a clinical diagnosis, and incomplete forms may not meet formal criteria-based diagnosis.

- Although DRESS syndrome typically has a morbilliform eruption, different rash morphologies may be observed.

- The myocarditis of DRESS syndrome may not present with chest pain; a high index of suspicion is warranted.

- Autoimmune sequelae are more frequent in patients who have had an episode of DRESS syndrome.

A sheep in wolf’s clothing?

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

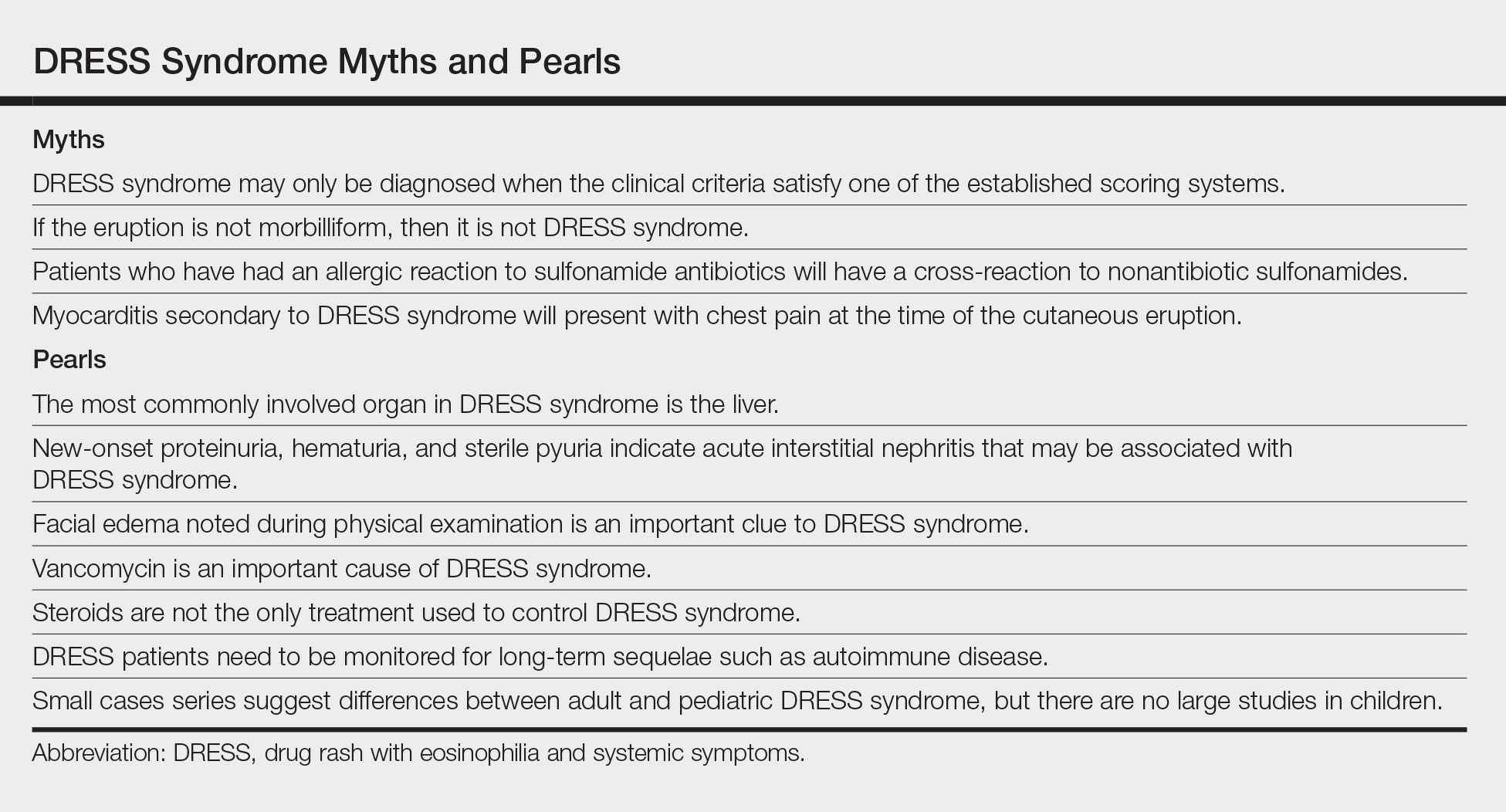

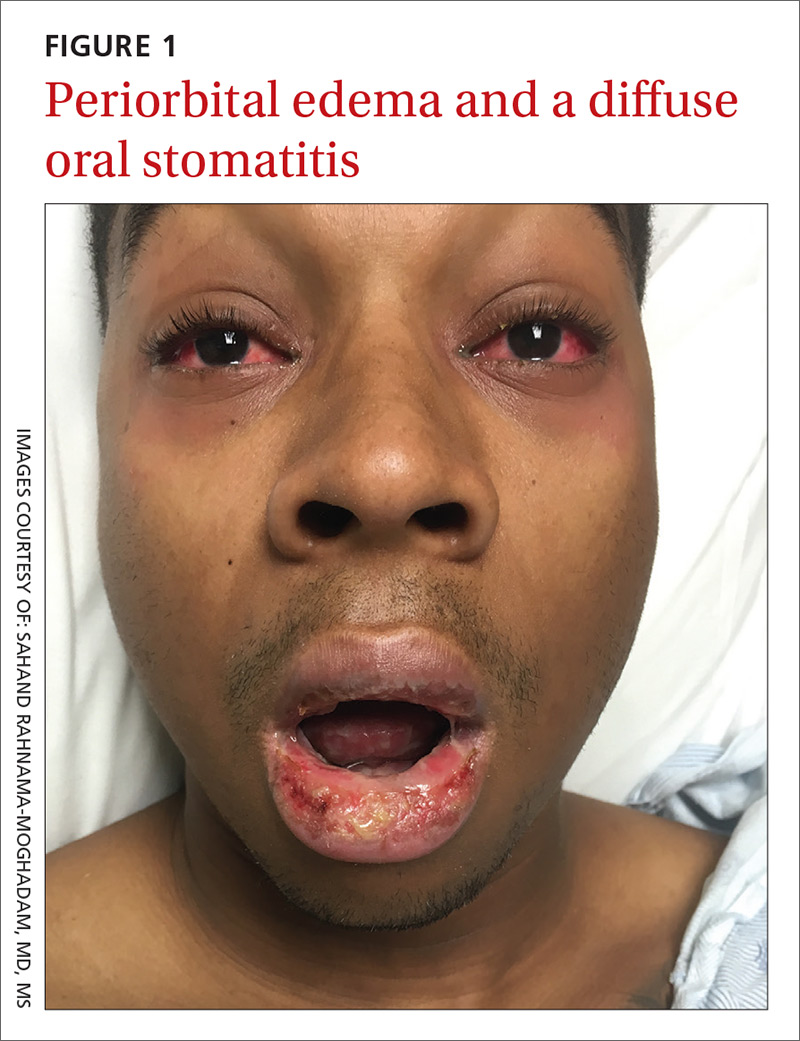

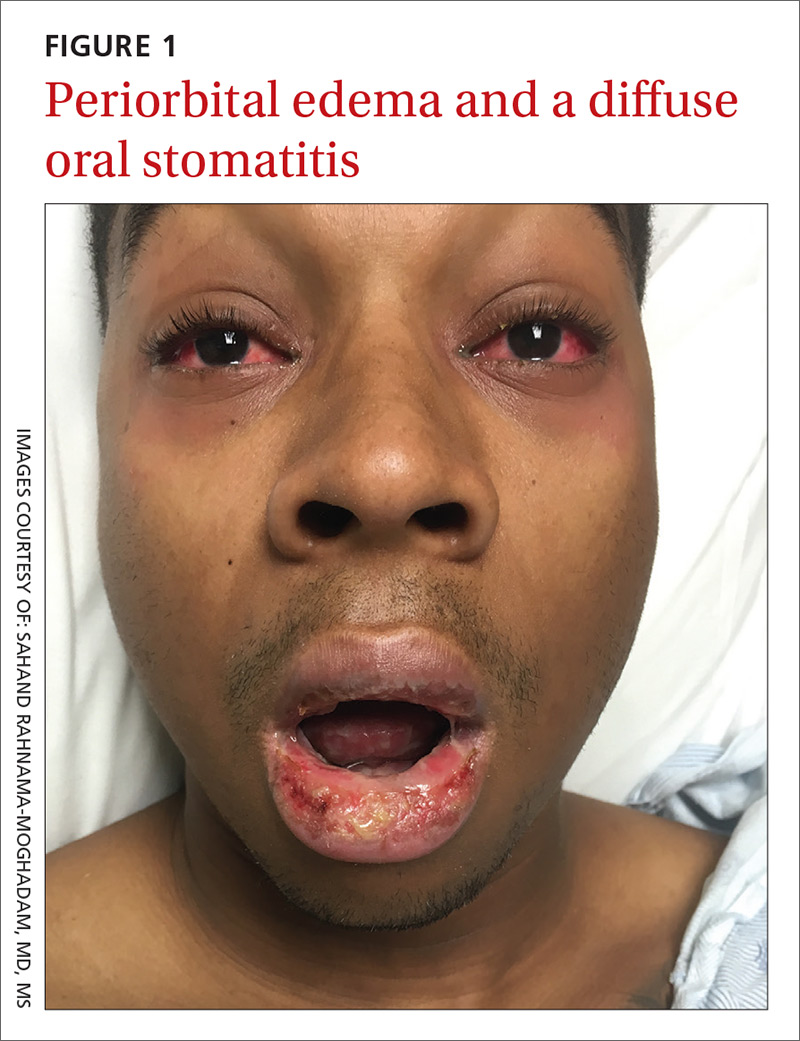

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

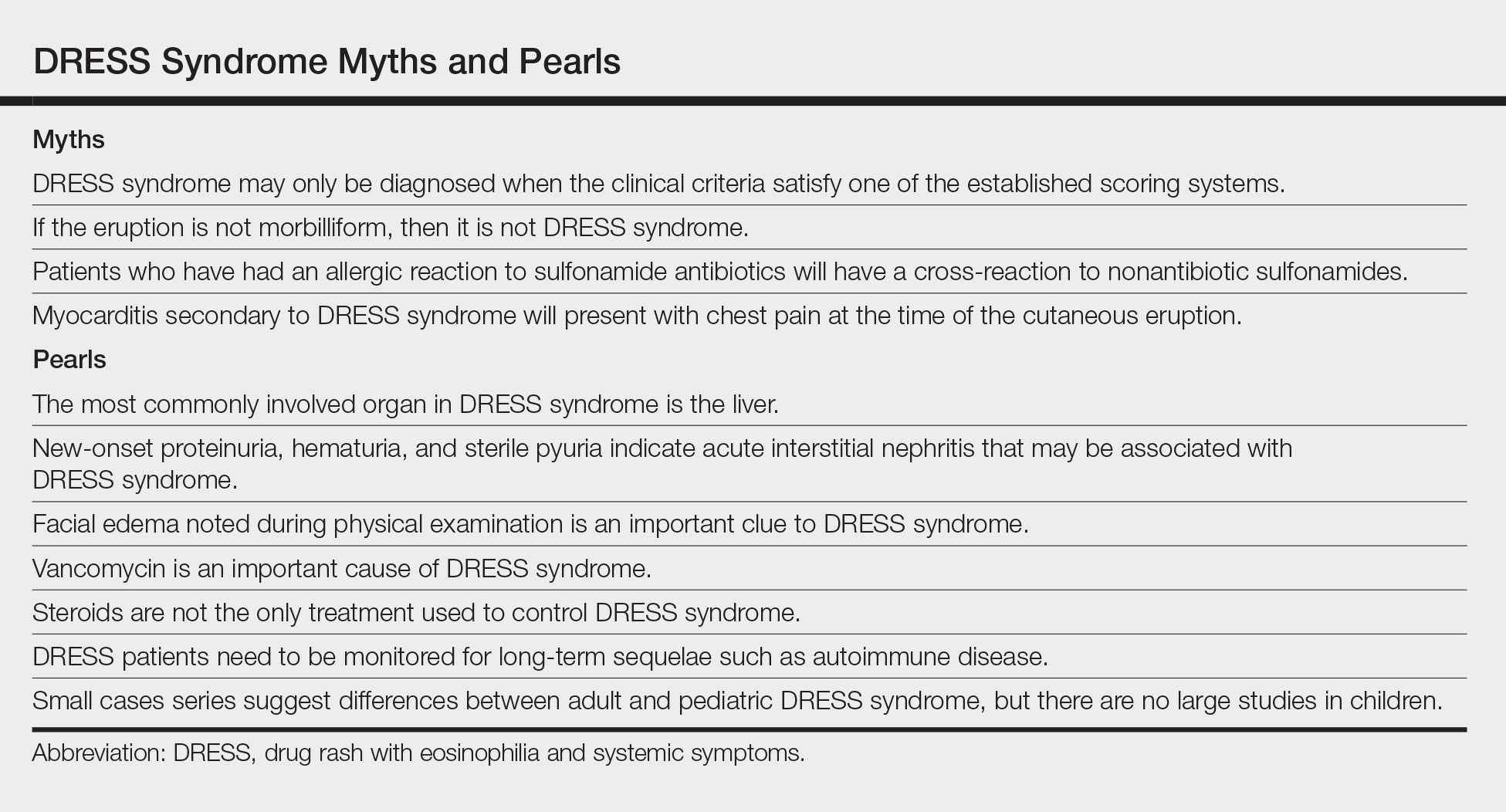

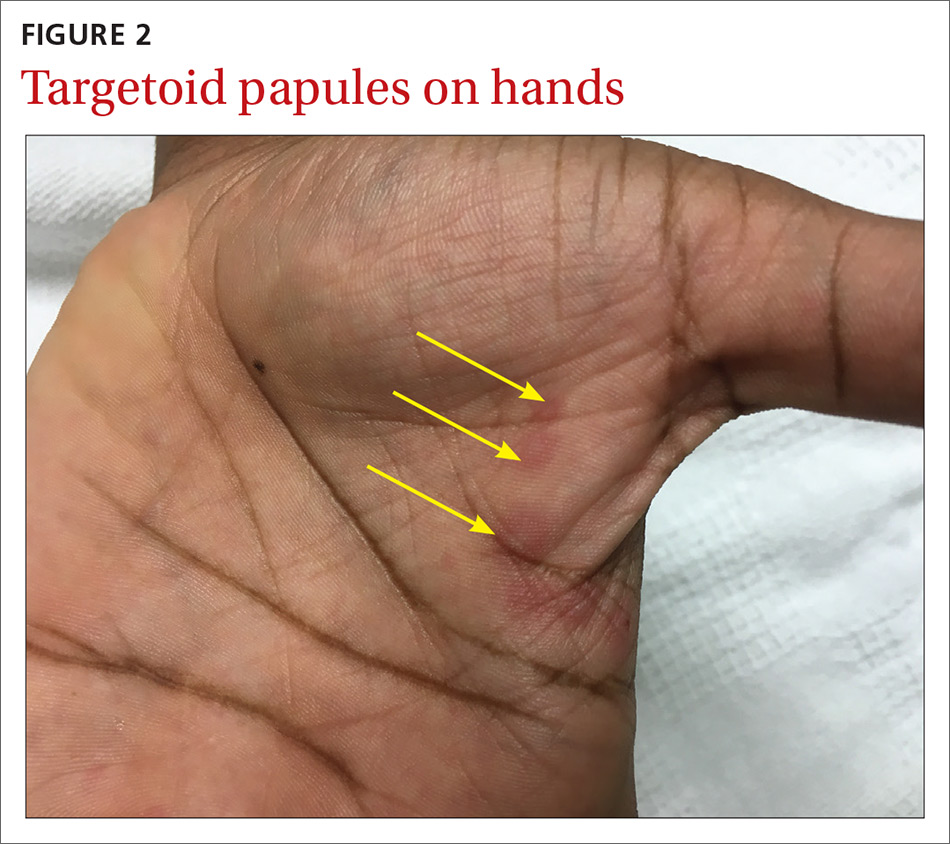

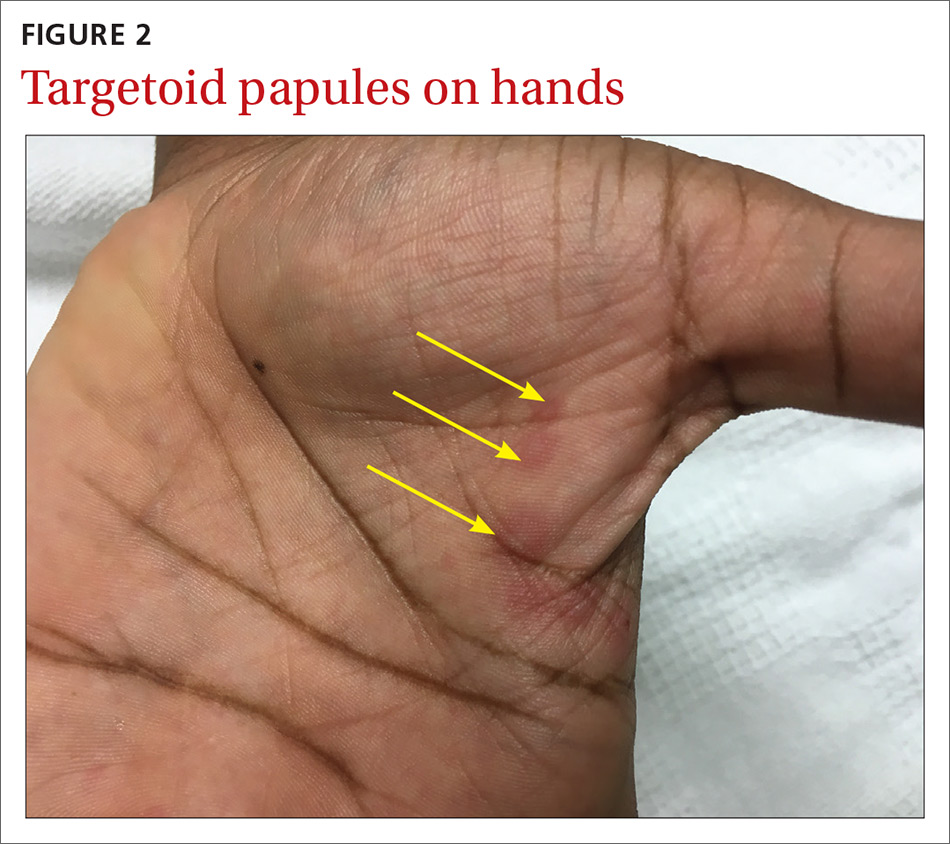

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis