User login

Progressing rash on boy’s trunk

The FP diagnosed pityriasis rosea based on clinical appearance, which included a herald patch (see arrow) that had preceded the eruption. (A herald patch—a solitary, oval, flesh-colored to salmon-colored lesion with scaling at the border—is seen in less than a quarter of pityriasis rosea cases.)

Pityriasis rosea is a papulosquamous eruption of unknown etiology. It occurs at all ages but is most commonly seen between the ages of 10 to 35. Peak incidence occurs between the ages of 20 to 29. Gender distribution is essentially equal.

Pityriasis rosea lesions vary from oval macules to slightly raised plaques (0.5 - 2 cm in size). They are salmon colored (or hyperpigmented in individuals with dark skin), and typically have a collarette of scaling at the border. There are no systemic symptoms, and itching occurs in about 25% of patients. The eruption resolves without treatment in 8 weeks in 80% of patients, but can last up to 3 to 5 months for some. A topical steroid or first-generation oral antihistamine can be prescribed to relieve pruritus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D, Usatine R. Pityriasis rosea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 896-900.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pityriasis rosea based on clinical appearance, which included a herald patch (see arrow) that had preceded the eruption. (A herald patch—a solitary, oval, flesh-colored to salmon-colored lesion with scaling at the border—is seen in less than a quarter of pityriasis rosea cases.)

Pityriasis rosea is a papulosquamous eruption of unknown etiology. It occurs at all ages but is most commonly seen between the ages of 10 to 35. Peak incidence occurs between the ages of 20 to 29. Gender distribution is essentially equal.

Pityriasis rosea lesions vary from oval macules to slightly raised plaques (0.5 - 2 cm in size). They are salmon colored (or hyperpigmented in individuals with dark skin), and typically have a collarette of scaling at the border. There are no systemic symptoms, and itching occurs in about 25% of patients. The eruption resolves without treatment in 8 weeks in 80% of patients, but can last up to 3 to 5 months for some. A topical steroid or first-generation oral antihistamine can be prescribed to relieve pruritus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D, Usatine R. Pityriasis rosea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 896-900.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pityriasis rosea based on clinical appearance, which included a herald patch (see arrow) that had preceded the eruption. (A herald patch—a solitary, oval, flesh-colored to salmon-colored lesion with scaling at the border—is seen in less than a quarter of pityriasis rosea cases.)

Pityriasis rosea is a papulosquamous eruption of unknown etiology. It occurs at all ages but is most commonly seen between the ages of 10 to 35. Peak incidence occurs between the ages of 20 to 29. Gender distribution is essentially equal.

Pityriasis rosea lesions vary from oval macules to slightly raised plaques (0.5 - 2 cm in size). They are salmon colored (or hyperpigmented in individuals with dark skin), and typically have a collarette of scaling at the border. There are no systemic symptoms, and itching occurs in about 25% of patients. The eruption resolves without treatment in 8 weeks in 80% of patients, but can last up to 3 to 5 months for some. A topical steroid or first-generation oral antihistamine can be prescribed to relieve pruritus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D, Usatine R. Pityriasis rosea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 896-900.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (His brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion, which can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than 10 years of age, with a peak incidence among African American boys. Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective. Oral fluconazole is typically administered at a dosage of 5 to 6 mg/kg/d for 3 to 6 weeks; an alternative regimen, 8 mg/kg once weekly for 8 to 12 weeks, is safe, effective, and associated with high compliance. Short-duration therapy with fluconazole 6 mg/kg/d for 2 weeks is also effective.

This patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks, his scalp lesions had completely resolved. The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

Adapted from: Kim K. Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:367-369

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (His brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion, which can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than 10 years of age, with a peak incidence among African American boys. Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective. Oral fluconazole is typically administered at a dosage of 5 to 6 mg/kg/d for 3 to 6 weeks; an alternative regimen, 8 mg/kg once weekly for 8 to 12 weeks, is safe, effective, and associated with high compliance. Short-duration therapy with fluconazole 6 mg/kg/d for 2 weeks is also effective.

This patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks, his scalp lesions had completely resolved. The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

Adapted from: Kim K. Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:367-369

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (His brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion, which can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than 10 years of age, with a peak incidence among African American boys. Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective. Oral fluconazole is typically administered at a dosage of 5 to 6 mg/kg/d for 3 to 6 weeks; an alternative regimen, 8 mg/kg once weekly for 8 to 12 weeks, is safe, effective, and associated with high compliance. Short-duration therapy with fluconazole 6 mg/kg/d for 2 weeks is also effective.

This patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks, his scalp lesions had completely resolved. The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

Adapted from: Kim K. Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:367-369

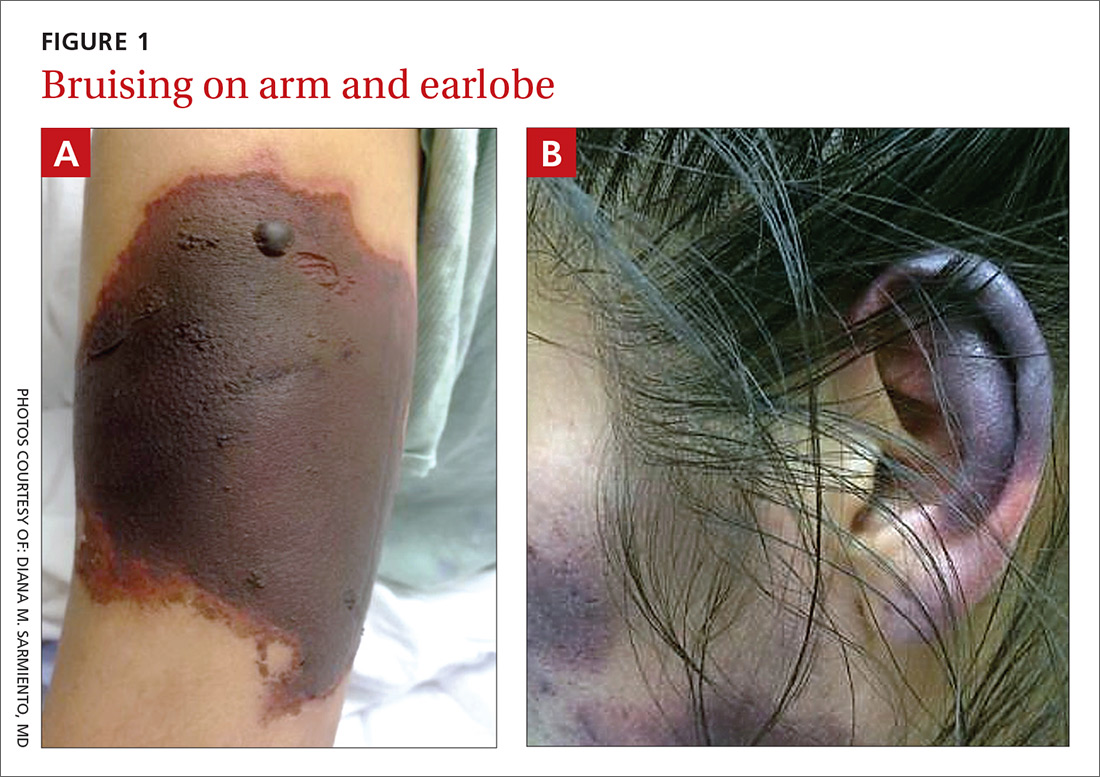

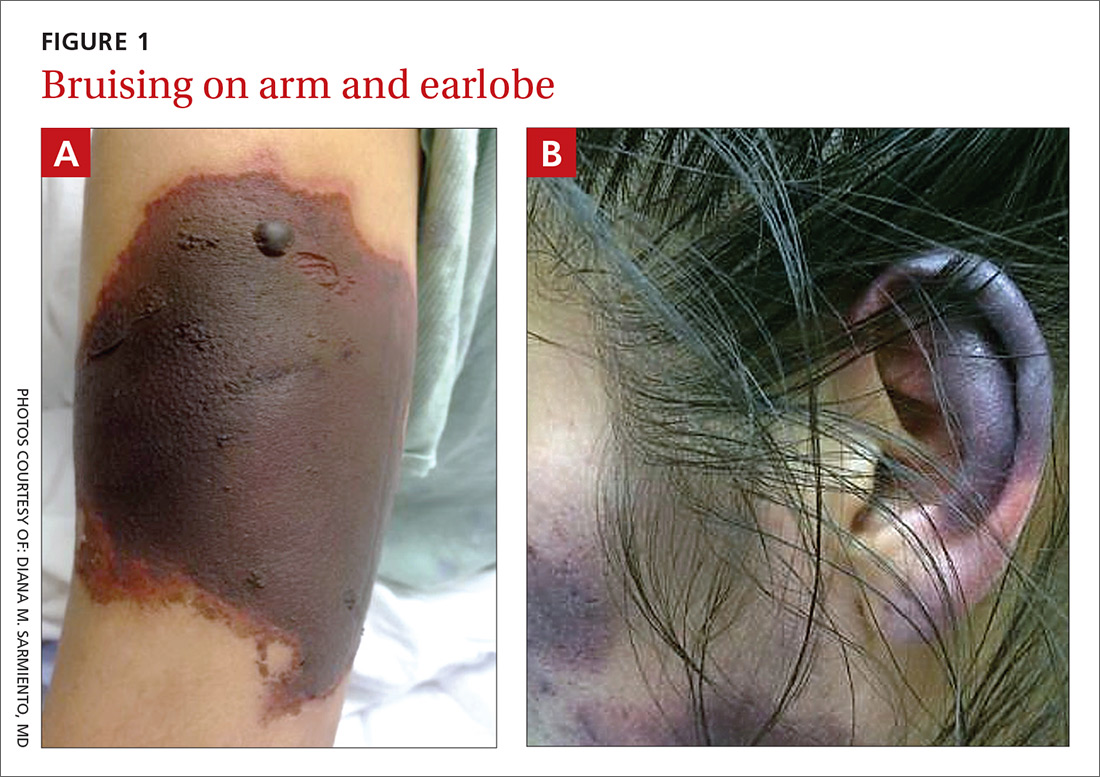

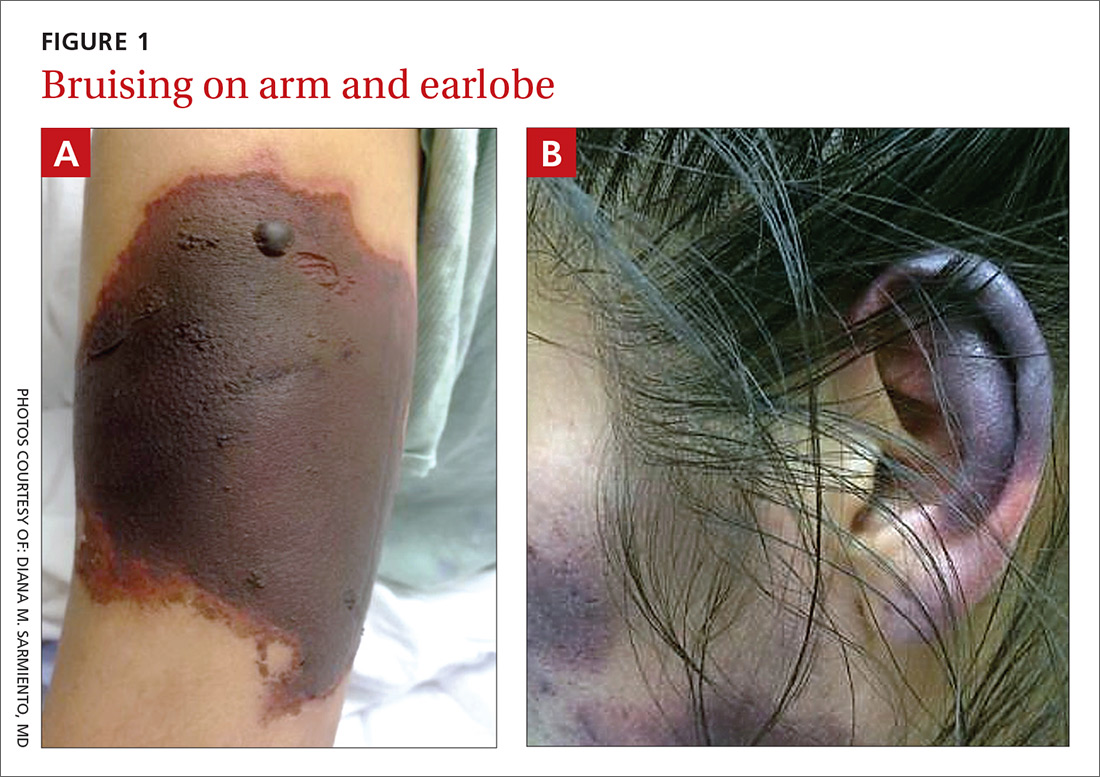

Bruises on the ears and body

Over the course of a month, this 34-year-old woman had sought care at our facility—and another—on 3 separate occasions for painful bruises (visits #1 and #3) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT; visit #2). The bruises first appeared acutely on her arms (FIGURE 1A), prompting her first visit to our ED and leading to a hospital stay. Several weeks later, the patient developed new bruise-like lesions on her earlobes (FIGURE 1B), face, trunk, and lower extremities. In between these 2 visits, the patient was seen in another ED (and admitted) for right upper extremity DVT and was started on enoxaparin, followed by warfarin.

The patient had no history of trauma, but did have a 7-year history of cocaine abuse. The initial bruises appeared one week after using cocaine from a different dealer.

On her most recent visit, her vitals and physical examination were unremarkable, apart from the skin findings. Her complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and urinalysis were unremarkable. On her previous admissions, the patient’s urine drug test had been positive for cocaine. She’d also tested positive for cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), and anticardiolipin IgM.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy

The patient was given a diagnosis of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy based on her history of cocaine use; the typical, painful palpable purpura with angulated borders and a necrotic center (retiform purpura); and positive immunologic markers.1-5 DVT has also been reported in association with levamisole-induced vasculopathy.6

Intended for livestock. Levamisole is a pharmaceutical agent typically used as an anthelmintic in livestock, but, since 2007, it has increasingly been found as an adulterant in cocaine.7 According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, 71% of cocaine tested in 2009 contained levamisole.7

Experts speculate that levamisole is used in the production process of cocaine to increase its volume and enhance its psychoactive effects.1-4 In humans, levamisole’s immunomodulatory properties were once used to treat various cancers and immunologic conditions, but it was withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to adverse effects.1,2,4 Severe adverse reactions associated with levamisole include agranulocytosis, vascular occlusive disease, and thrombotic vasculopathy with or without vasculitis.1,2

The incidence of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy is unknown. That said, it’s important to suspect the condition in cocaine users who present with retiform purpura. Earlobe lesions are characteristic, while involvement of other areas is variable.2-4

Differential includes other causes of purpura

A number of conditions make up the differential. While each of these presents with areas of skin necrosis or purpura, a thorough history can be revealing. Factors such as substance abuse, recent treatment with a vitamin K antagonist, or even a recent infection can be the key to making the diagnosis.

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis presents with large, irregular bullae that eventually become necrotic. It appears one to 10 days after treatment with a vitamin K antagonist and typically affects areas of the body with greater subcutaneous adipose tissue, including the breasts, thighs, buttocks, and penis. Microscopic examination reveals bland thrombi with no inflammation of the vessel wall.5

ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis includes microscopic polyangiitis, Wegner’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome. With these conditions, palpable purpuras are more commonly seen in areas that are dependent on, or affected by, venous stasis. Microscopic evaluation reveals leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perinuclear ANCA is more often positive than c-ANCA.5

Purpura fulminans is a medical emergency characterized by skin necrosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. It can rapidly lead to multi-organ failure. Microscopic evaluation reveals thrombotic occlusion of small- and medium-sized vessels. It affects neonates and children, and is associated with severe sepsis or an autoimmune response to an otherwise benign childhood infection. It may also be a symptom of hereditary protein C or protein S deficiency.8

Cholesterol emboli are more common in men ages 50 and older with atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, or tobacco use. Abrupt onset of livedo reticularis may be followed by retiform purpura, ulcers, nodules, and gangrene. Lesions most often appear on the distal lower extremities and buttocks. Systemic symptoms may include fever, weight loss, myalgia, and altered mental status. Multiple organ systems may be involved. Frozen sections reveal needle-shaped clefts and doubly-refractile crystals.5

Evolving skin lesions, relevant lab findings

Initially, patients with levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy will develop painful, palpable purpura with angulated borders and a necrotic center. The lesions can progress, though, to bullae, necrosis, or eschar formation.1,3,4

Patients with this condition frequently test positive for ANCA and, even more frequently, for c-ANCA, ANA, antiphospholipid antibodies, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Other immunologic markers for which patients may test positive include anti-cardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, anti-dsDNA, myeloperoxidase, and anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (also known as anti-Ro) antibodies.1-4

Natural progression of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy is generally benign. Most clinical signs and symptoms—as well as serologic manifestations—resolve without intervention after cessation of cocaine use. However, signs and symptoms may recur with subsequent exposure.

There is no specific therapy for levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy, but prednisone and other immunosuppressive agents can be used in patients with severe or systemic symptoms.1-4 Necrotic lesions and eschar formation may be complicated by infection and require debridement and/or skin grafts.

Our patient was discharged after a brief hospital stay, as she had no indication of systemic involvement and no new or worsening skin lesions. She was given wound care instructions and advised to stop using cocaine. The patient was counseled at bedside by a physician and given information on community resources (outpatient treatment, support groups, etc) by social services. However, the patient continued to use the substance and had several readmissions with worsening skin lesions complicated by secondary bacterial infection. She did not have systemic complications, but required antibiotics, multiple wound debridement sessions, and subsequent skin grafts.

CORRESPONDENCE

Yu Wah, MD, ABIHM, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Suite JJL 308, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

1. Gaertner EM, Switlyk SA. Dermatologic complications from levamisole-contaminated cocaine: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2014;93:102-106.

2. Strazzula L, Brown KK, Brieva JC, et al. Levamisole toxicity mimicking autoimmune disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:954-959.

3. Espinoza LR, Perez Alamino R. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: clinical and immunological spectrum. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:532-538.

4. Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia–a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

5. Wysong A, Venkatesan P. An approach to the patient with retiform purpura. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:151-172.

6. Wilson L, Hull C, Petersen M, et al. End organ damage in levamisole adulterated cocaine: More than just purpura and agranulocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB9.

7. US Department of Justice. National Drug Threat Assessment 2010. Impact of drugs on society. Available at: http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs38/38661/drugImpact.htm. Accessed July 26, 2017.

8. Chalmers E, Cooper P, Forman K, et al. Purpura fulminans: recognition, diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1066-1071.

Over the course of a month, this 34-year-old woman had sought care at our facility—and another—on 3 separate occasions for painful bruises (visits #1 and #3) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT; visit #2). The bruises first appeared acutely on her arms (FIGURE 1A), prompting her first visit to our ED and leading to a hospital stay. Several weeks later, the patient developed new bruise-like lesions on her earlobes (FIGURE 1B), face, trunk, and lower extremities. In between these 2 visits, the patient was seen in another ED (and admitted) for right upper extremity DVT and was started on enoxaparin, followed by warfarin.

The patient had no history of trauma, but did have a 7-year history of cocaine abuse. The initial bruises appeared one week after using cocaine from a different dealer.

On her most recent visit, her vitals and physical examination were unremarkable, apart from the skin findings. Her complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and urinalysis were unremarkable. On her previous admissions, the patient’s urine drug test had been positive for cocaine. She’d also tested positive for cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), and anticardiolipin IgM.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy

The patient was given a diagnosis of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy based on her history of cocaine use; the typical, painful palpable purpura with angulated borders and a necrotic center (retiform purpura); and positive immunologic markers.1-5 DVT has also been reported in association with levamisole-induced vasculopathy.6

Intended for livestock. Levamisole is a pharmaceutical agent typically used as an anthelmintic in livestock, but, since 2007, it has increasingly been found as an adulterant in cocaine.7 According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, 71% of cocaine tested in 2009 contained levamisole.7

Experts speculate that levamisole is used in the production process of cocaine to increase its volume and enhance its psychoactive effects.1-4 In humans, levamisole’s immunomodulatory properties were once used to treat various cancers and immunologic conditions, but it was withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to adverse effects.1,2,4 Severe adverse reactions associated with levamisole include agranulocytosis, vascular occlusive disease, and thrombotic vasculopathy with or without vasculitis.1,2

The incidence of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy is unknown. That said, it’s important to suspect the condition in cocaine users who present with retiform purpura. Earlobe lesions are characteristic, while involvement of other areas is variable.2-4

Differential includes other causes of purpura

A number of conditions make up the differential. While each of these presents with areas of skin necrosis or purpura, a thorough history can be revealing. Factors such as substance abuse, recent treatment with a vitamin K antagonist, or even a recent infection can be the key to making the diagnosis.

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis presents with large, irregular bullae that eventually become necrotic. It appears one to 10 days after treatment with a vitamin K antagonist and typically affects areas of the body with greater subcutaneous adipose tissue, including the breasts, thighs, buttocks, and penis. Microscopic examination reveals bland thrombi with no inflammation of the vessel wall.5

ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis includes microscopic polyangiitis, Wegner’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome. With these conditions, palpable purpuras are more commonly seen in areas that are dependent on, or affected by, venous stasis. Microscopic evaluation reveals leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perinuclear ANCA is more often positive than c-ANCA.5

Purpura fulminans is a medical emergency characterized by skin necrosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. It can rapidly lead to multi-organ failure. Microscopic evaluation reveals thrombotic occlusion of small- and medium-sized vessels. It affects neonates and children, and is associated with severe sepsis or an autoimmune response to an otherwise benign childhood infection. It may also be a symptom of hereditary protein C or protein S deficiency.8

Cholesterol emboli are more common in men ages 50 and older with atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, or tobacco use. Abrupt onset of livedo reticularis may be followed by retiform purpura, ulcers, nodules, and gangrene. Lesions most often appear on the distal lower extremities and buttocks. Systemic symptoms may include fever, weight loss, myalgia, and altered mental status. Multiple organ systems may be involved. Frozen sections reveal needle-shaped clefts and doubly-refractile crystals.5

Evolving skin lesions, relevant lab findings

Initially, patients with levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy will develop painful, palpable purpura with angulated borders and a necrotic center. The lesions can progress, though, to bullae, necrosis, or eschar formation.1,3,4

Patients with this condition frequently test positive for ANCA and, even more frequently, for c-ANCA, ANA, antiphospholipid antibodies, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Other immunologic markers for which patients may test positive include anti-cardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, anti-dsDNA, myeloperoxidase, and anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (also known as anti-Ro) antibodies.1-4

Natural progression of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy is generally benign. Most clinical signs and symptoms—as well as serologic manifestations—resolve without intervention after cessation of cocaine use. However, signs and symptoms may recur with subsequent exposure.

There is no specific therapy for levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy, but prednisone and other immunosuppressive agents can be used in patients with severe or systemic symptoms.1-4 Necrotic lesions and eschar formation may be complicated by infection and require debridement and/or skin grafts.

Our patient was discharged after a brief hospital stay, as she had no indication of systemic involvement and no new or worsening skin lesions. She was given wound care instructions and advised to stop using cocaine. The patient was counseled at bedside by a physician and given information on community resources (outpatient treatment, support groups, etc) by social services. However, the patient continued to use the substance and had several readmissions with worsening skin lesions complicated by secondary bacterial infection. She did not have systemic complications, but required antibiotics, multiple wound debridement sessions, and subsequent skin grafts.

CORRESPONDENCE

Yu Wah, MD, ABIHM, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Suite JJL 308, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

Over the course of a month, this 34-year-old woman had sought care at our facility—and another—on 3 separate occasions for painful bruises (visits #1 and #3) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT; visit #2). The bruises first appeared acutely on her arms (FIGURE 1A), prompting her first visit to our ED and leading to a hospital stay. Several weeks later, the patient developed new bruise-like lesions on her earlobes (FIGURE 1B), face, trunk, and lower extremities. In between these 2 visits, the patient was seen in another ED (and admitted) for right upper extremity DVT and was started on enoxaparin, followed by warfarin.

The patient had no history of trauma, but did have a 7-year history of cocaine abuse. The initial bruises appeared one week after using cocaine from a different dealer.

On her most recent visit, her vitals and physical examination were unremarkable, apart from the skin findings. Her complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and urinalysis were unremarkable. On her previous admissions, the patient’s urine drug test had been positive for cocaine. She’d also tested positive for cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), and anticardiolipin IgM.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy

The patient was given a diagnosis of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy based on her history of cocaine use; the typical, painful palpable purpura with angulated borders and a necrotic center (retiform purpura); and positive immunologic markers.1-5 DVT has also been reported in association with levamisole-induced vasculopathy.6

Intended for livestock. Levamisole is a pharmaceutical agent typically used as an anthelmintic in livestock, but, since 2007, it has increasingly been found as an adulterant in cocaine.7 According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, 71% of cocaine tested in 2009 contained levamisole.7

Experts speculate that levamisole is used in the production process of cocaine to increase its volume and enhance its psychoactive effects.1-4 In humans, levamisole’s immunomodulatory properties were once used to treat various cancers and immunologic conditions, but it was withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to adverse effects.1,2,4 Severe adverse reactions associated with levamisole include agranulocytosis, vascular occlusive disease, and thrombotic vasculopathy with or without vasculitis.1,2

The incidence of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy is unknown. That said, it’s important to suspect the condition in cocaine users who present with retiform purpura. Earlobe lesions are characteristic, while involvement of other areas is variable.2-4

Differential includes other causes of purpura

A number of conditions make up the differential. While each of these presents with areas of skin necrosis or purpura, a thorough history can be revealing. Factors such as substance abuse, recent treatment with a vitamin K antagonist, or even a recent infection can be the key to making the diagnosis.

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis presents with large, irregular bullae that eventually become necrotic. It appears one to 10 days after treatment with a vitamin K antagonist and typically affects areas of the body with greater subcutaneous adipose tissue, including the breasts, thighs, buttocks, and penis. Microscopic examination reveals bland thrombi with no inflammation of the vessel wall.5

ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis includes microscopic polyangiitis, Wegner’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome. With these conditions, palpable purpuras are more commonly seen in areas that are dependent on, or affected by, venous stasis. Microscopic evaluation reveals leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perinuclear ANCA is more often positive than c-ANCA.5

Purpura fulminans is a medical emergency characterized by skin necrosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. It can rapidly lead to multi-organ failure. Microscopic evaluation reveals thrombotic occlusion of small- and medium-sized vessels. It affects neonates and children, and is associated with severe sepsis or an autoimmune response to an otherwise benign childhood infection. It may also be a symptom of hereditary protein C or protein S deficiency.8

Cholesterol emboli are more common in men ages 50 and older with atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, or tobacco use. Abrupt onset of livedo reticularis may be followed by retiform purpura, ulcers, nodules, and gangrene. Lesions most often appear on the distal lower extremities and buttocks. Systemic symptoms may include fever, weight loss, myalgia, and altered mental status. Multiple organ systems may be involved. Frozen sections reveal needle-shaped clefts and doubly-refractile crystals.5

Evolving skin lesions, relevant lab findings

Initially, patients with levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy will develop painful, palpable purpura with angulated borders and a necrotic center. The lesions can progress, though, to bullae, necrosis, or eschar formation.1,3,4

Patients with this condition frequently test positive for ANCA and, even more frequently, for c-ANCA, ANA, antiphospholipid antibodies, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Other immunologic markers for which patients may test positive include anti-cardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, anti-dsDNA, myeloperoxidase, and anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (also known as anti-Ro) antibodies.1-4

Natural progression of levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy is generally benign. Most clinical signs and symptoms—as well as serologic manifestations—resolve without intervention after cessation of cocaine use. However, signs and symptoms may recur with subsequent exposure.

There is no specific therapy for levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculopathy, but prednisone and other immunosuppressive agents can be used in patients with severe or systemic symptoms.1-4 Necrotic lesions and eschar formation may be complicated by infection and require debridement and/or skin grafts.

Our patient was discharged after a brief hospital stay, as she had no indication of systemic involvement and no new or worsening skin lesions. She was given wound care instructions and advised to stop using cocaine. The patient was counseled at bedside by a physician and given information on community resources (outpatient treatment, support groups, etc) by social services. However, the patient continued to use the substance and had several readmissions with worsening skin lesions complicated by secondary bacterial infection. She did not have systemic complications, but required antibiotics, multiple wound debridement sessions, and subsequent skin grafts.

CORRESPONDENCE

Yu Wah, MD, ABIHM, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Suite JJL 308, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

1. Gaertner EM, Switlyk SA. Dermatologic complications from levamisole-contaminated cocaine: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2014;93:102-106.

2. Strazzula L, Brown KK, Brieva JC, et al. Levamisole toxicity mimicking autoimmune disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:954-959.

3. Espinoza LR, Perez Alamino R. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: clinical and immunological spectrum. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:532-538.

4. Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia–a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

5. Wysong A, Venkatesan P. An approach to the patient with retiform purpura. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:151-172.

6. Wilson L, Hull C, Petersen M, et al. End organ damage in levamisole adulterated cocaine: More than just purpura and agranulocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB9.

7. US Department of Justice. National Drug Threat Assessment 2010. Impact of drugs on society. Available at: http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs38/38661/drugImpact.htm. Accessed July 26, 2017.

8. Chalmers E, Cooper P, Forman K, et al. Purpura fulminans: recognition, diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1066-1071.

1. Gaertner EM, Switlyk SA. Dermatologic complications from levamisole-contaminated cocaine: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2014;93:102-106.

2. Strazzula L, Brown KK, Brieva JC, et al. Levamisole toxicity mimicking autoimmune disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:954-959.

3. Espinoza LR, Perez Alamino R. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: clinical and immunological spectrum. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:532-538.

4. Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia–a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

5. Wysong A, Venkatesan P. An approach to the patient with retiform purpura. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:151-172.

6. Wilson L, Hull C, Petersen M, et al. End organ damage in levamisole adulterated cocaine: More than just purpura and agranulocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB9.

7. US Department of Justice. National Drug Threat Assessment 2010. Impact of drugs on society. Available at: http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs38/38661/drugImpact.htm. Accessed July 26, 2017.

8. Chalmers E, Cooper P, Forman K, et al. Purpura fulminans: recognition, diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1066-1071.

Periorbital ecchymoses and breathlessness

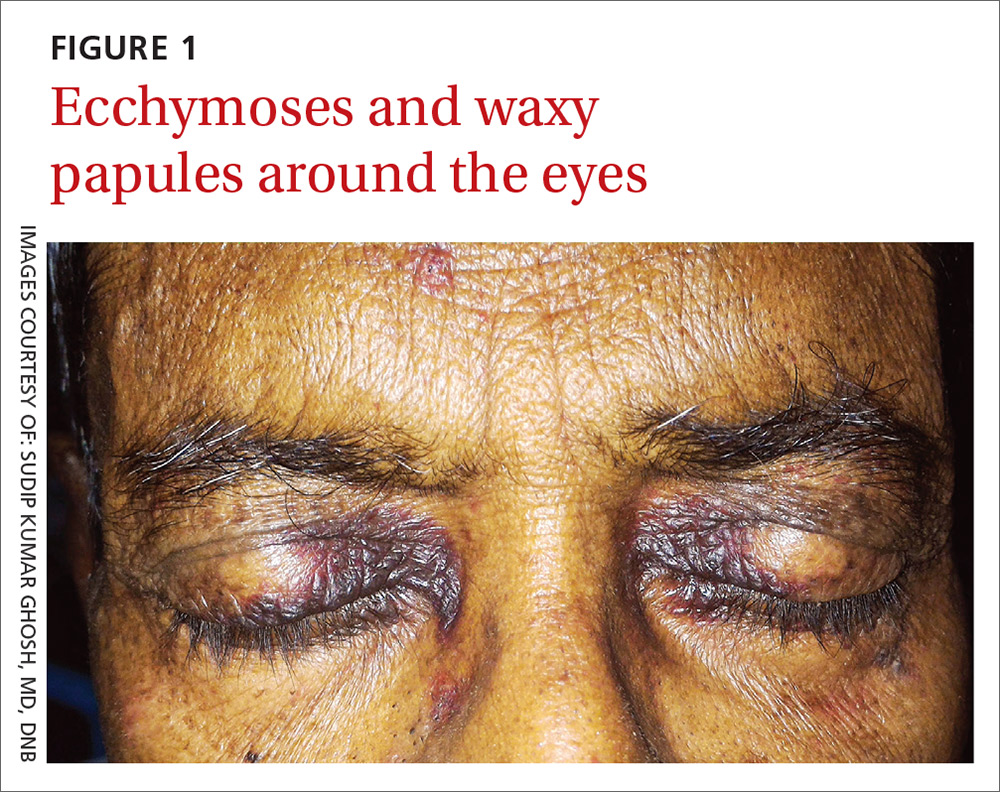

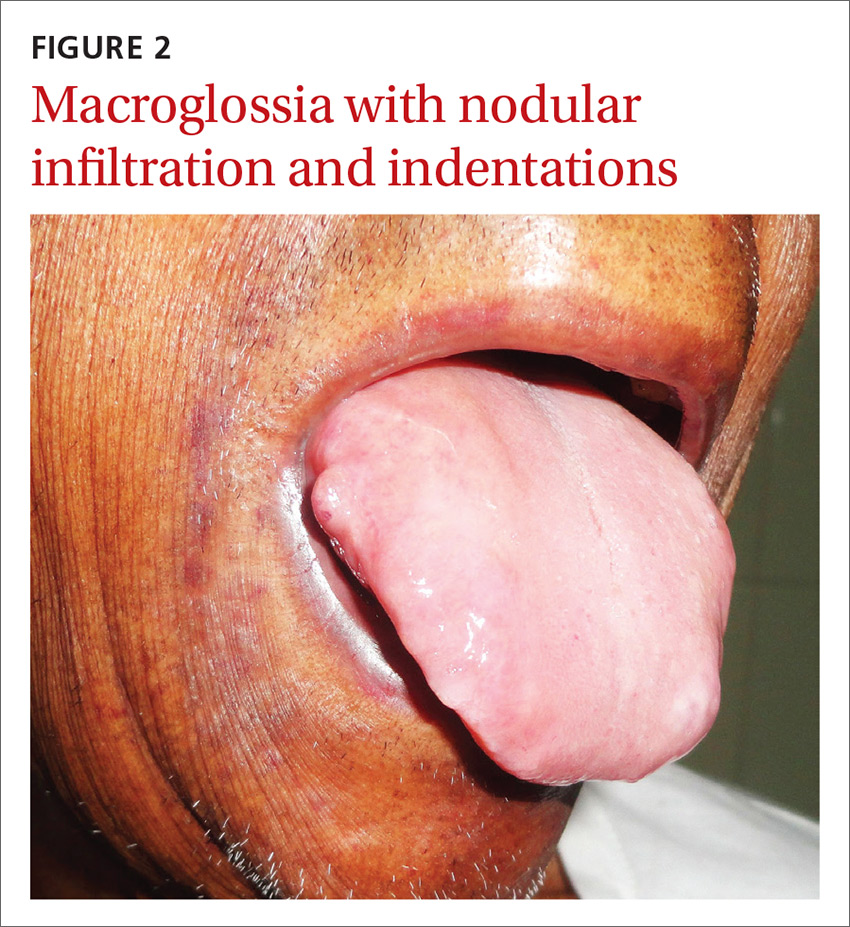

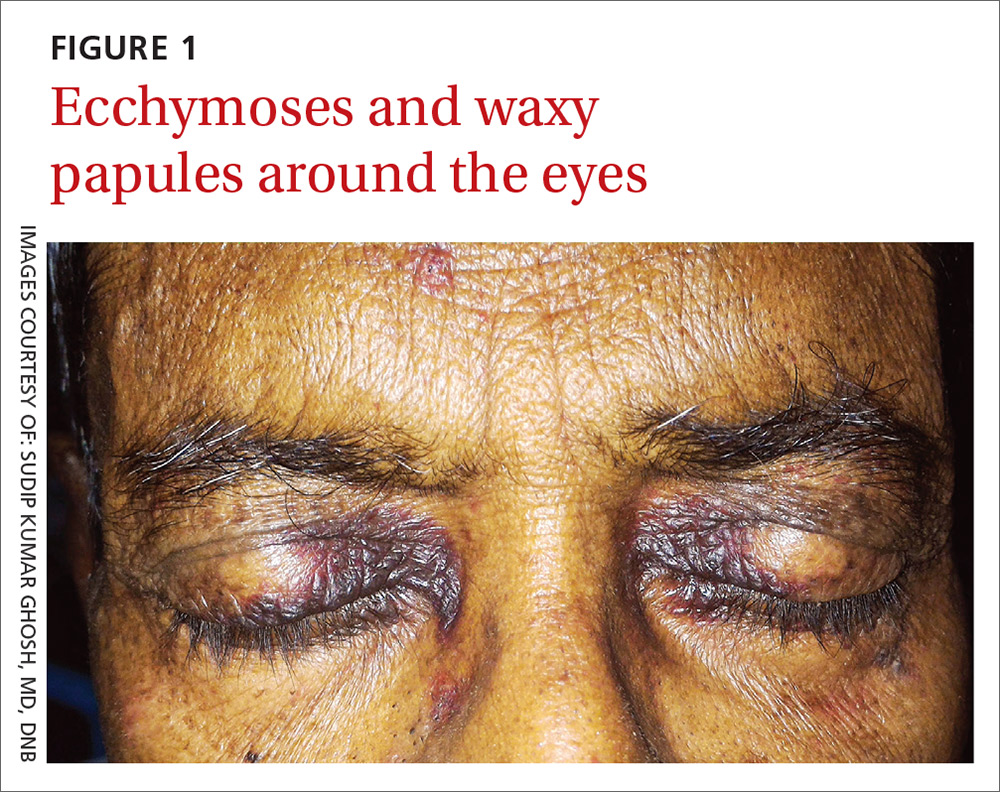

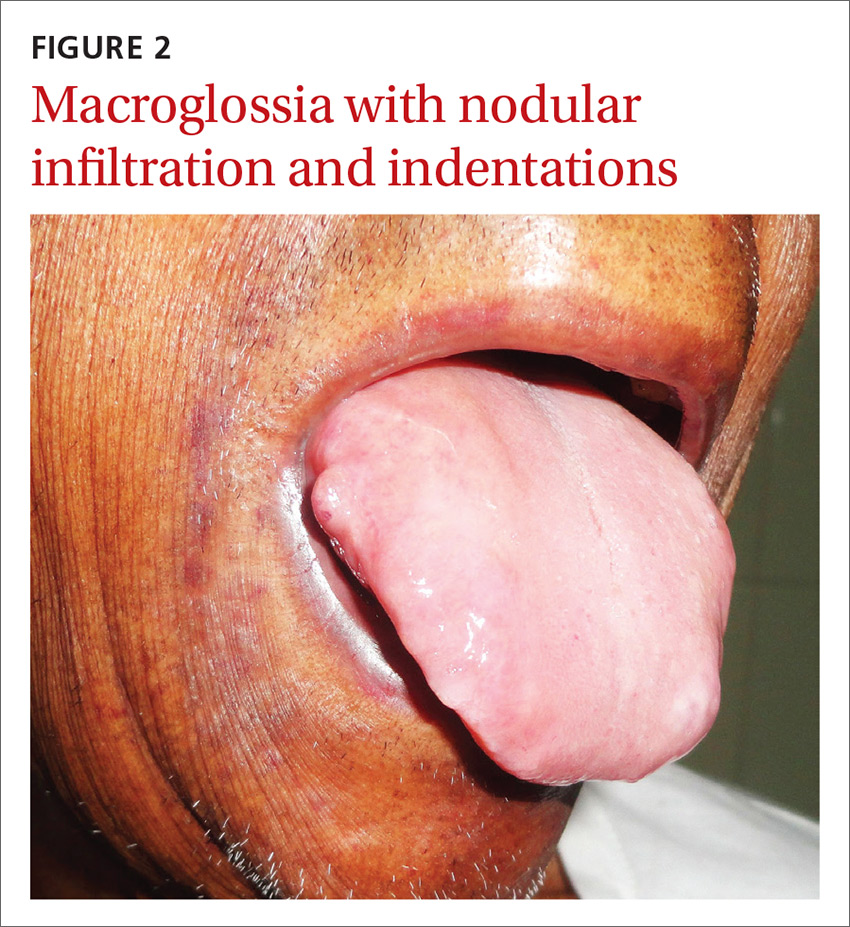

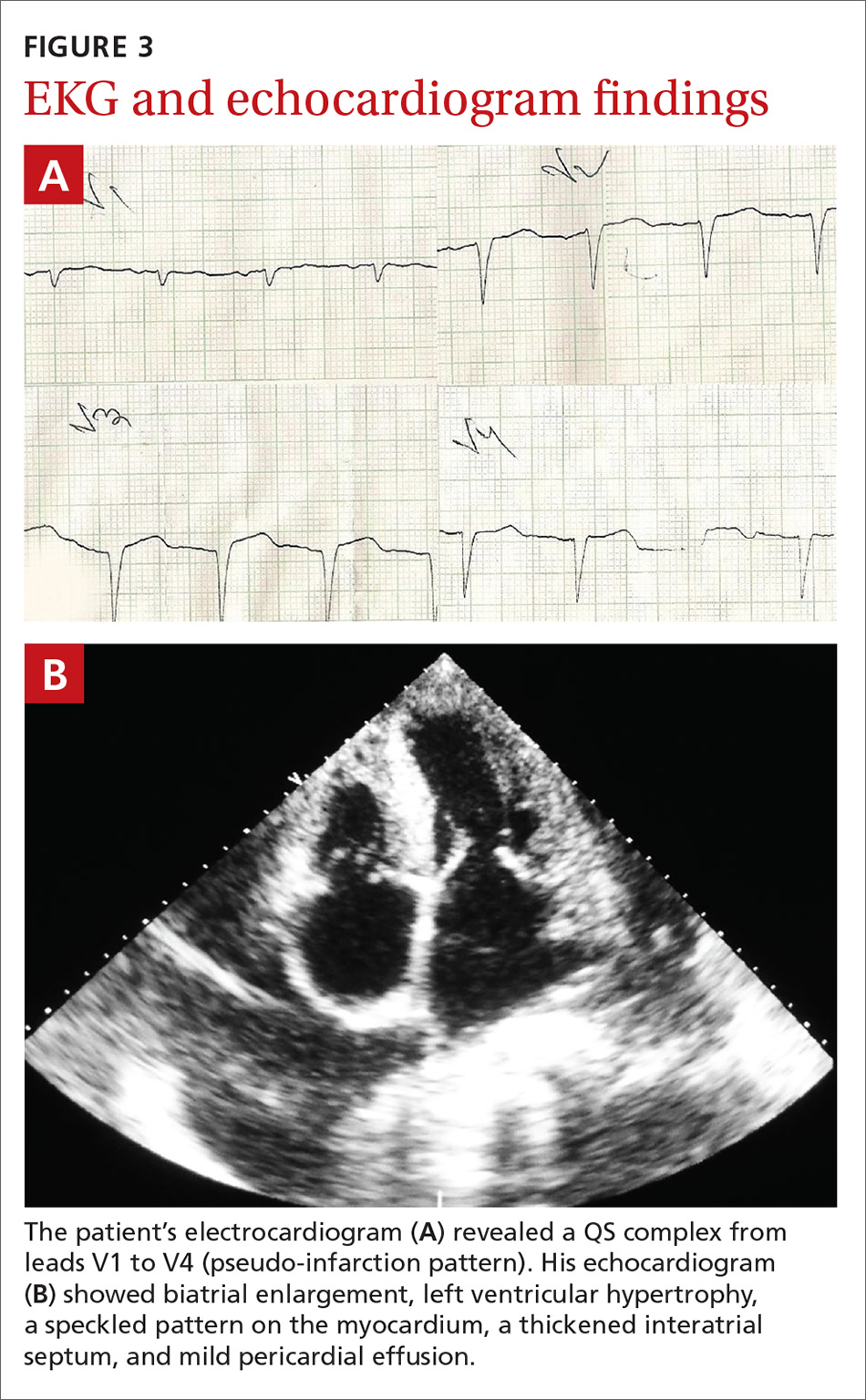

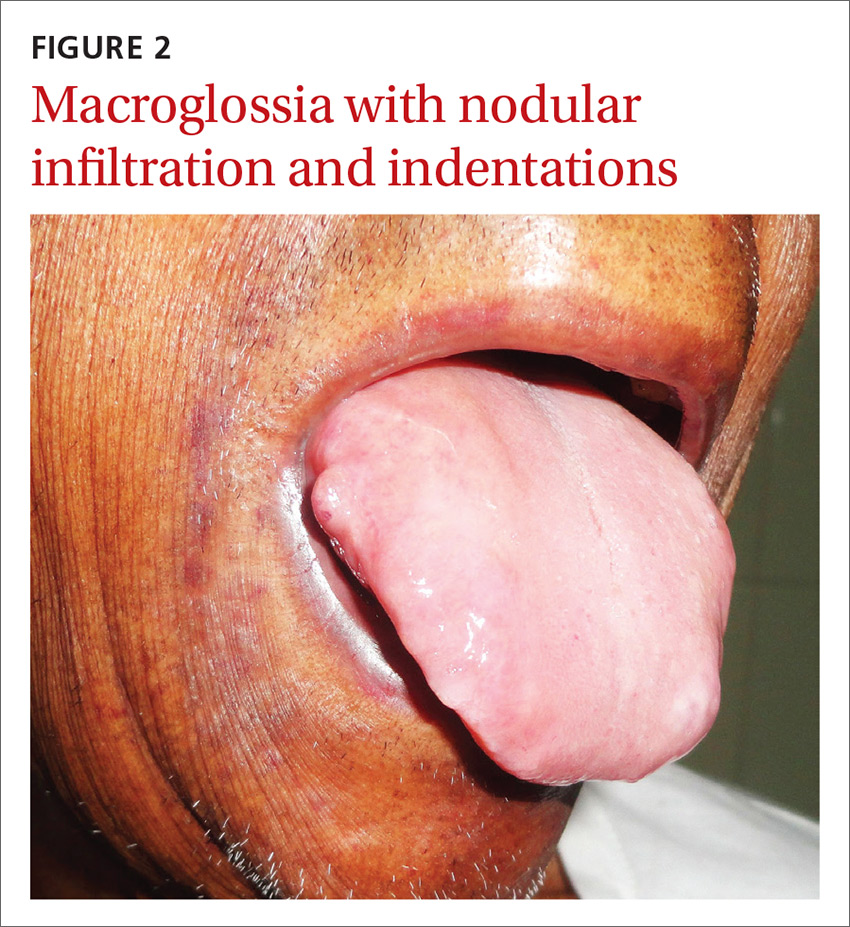

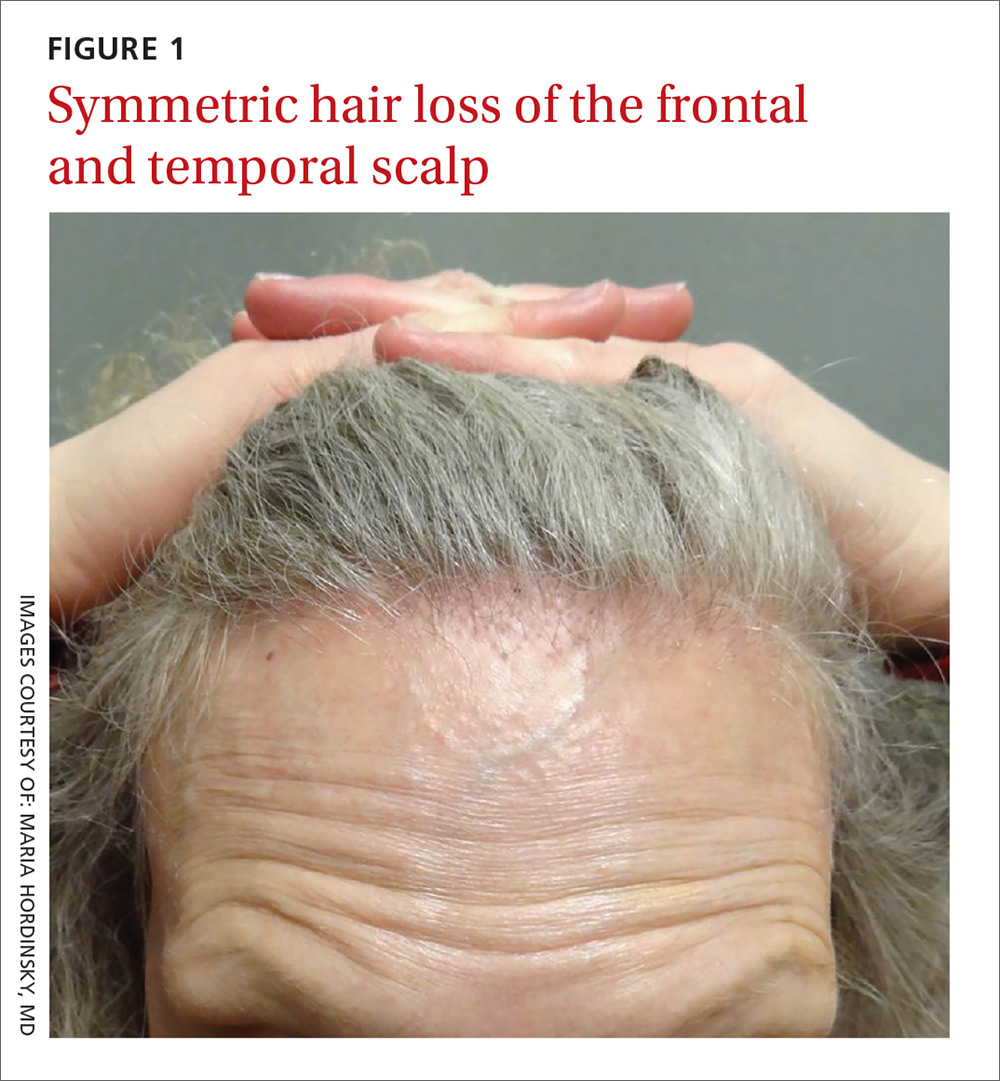

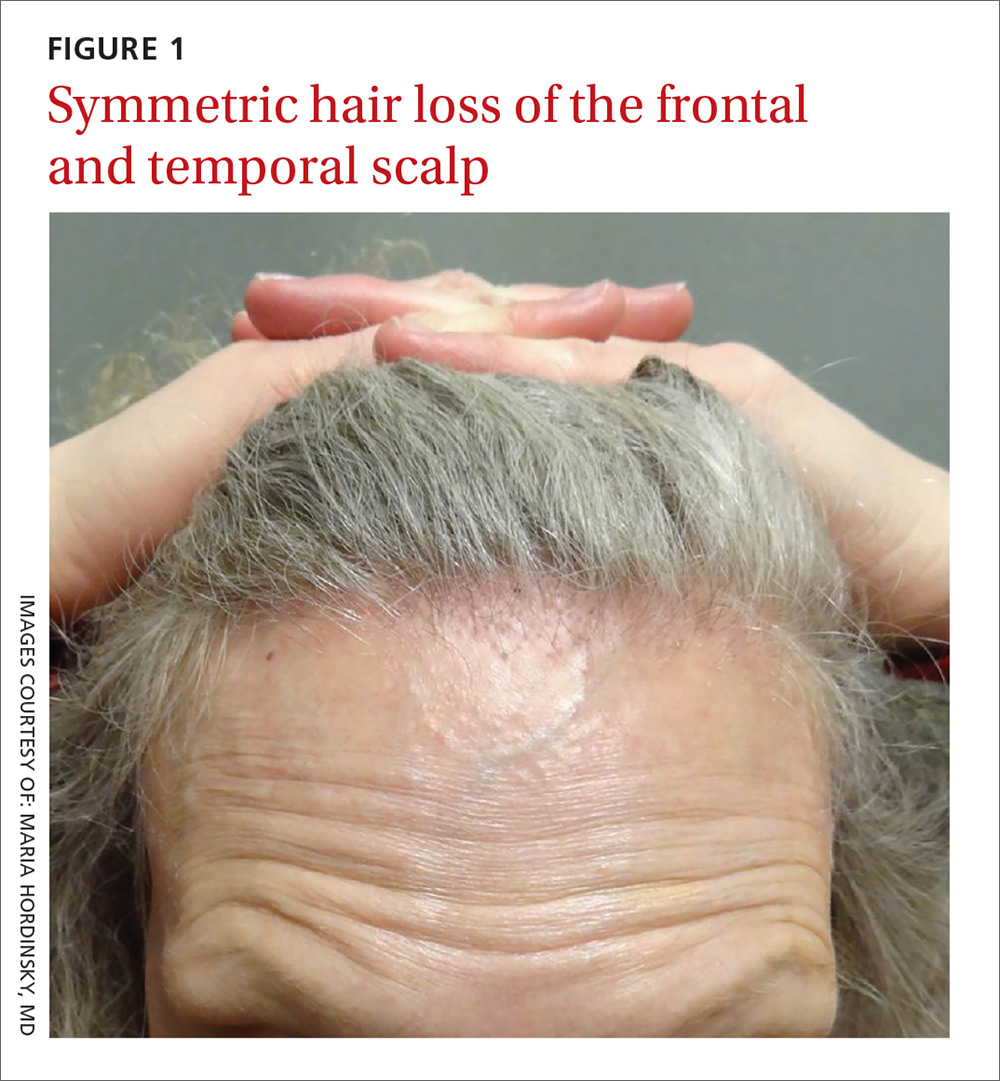

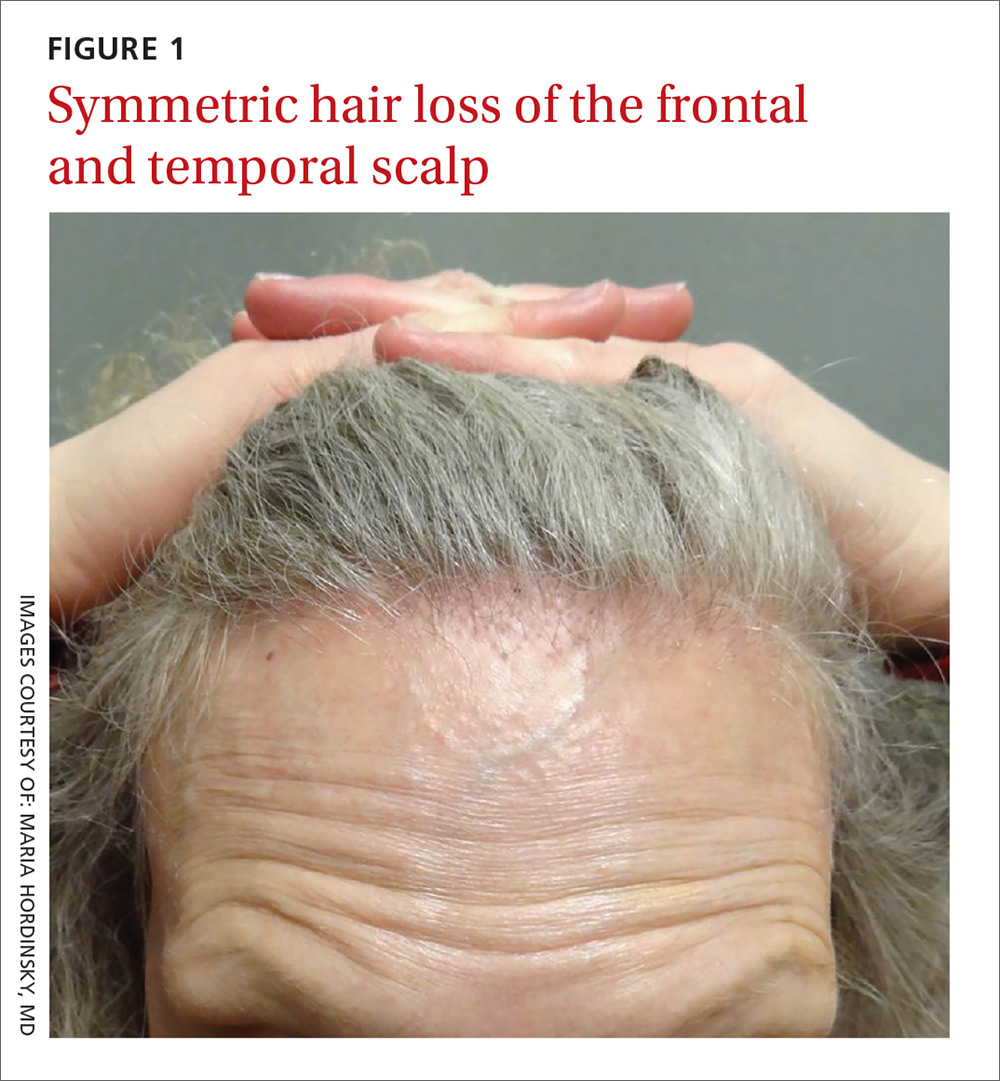

A 54-year-old man presented at our facility with a 3-month history of exertional breathlessness and purple blotches around his eyes. Examination revealed bilateral periorbital and perioral ecchymosis, purpuric spots along his waist, and waxy papules on his eyelids (FIGURE 1). In addition, the patient had macroglossia with nodular infiltration and irregular indentations at the lateral margin of his tongue (FIGURE 2).

The patient also had a raised jugular venous pressure and prominent atrial and ventricular waves. Further examination revealed a fourth heart sound over the left ventricular apex, as well as bilateral basal rales. All other systems were normal except for mild hepatomegaly.

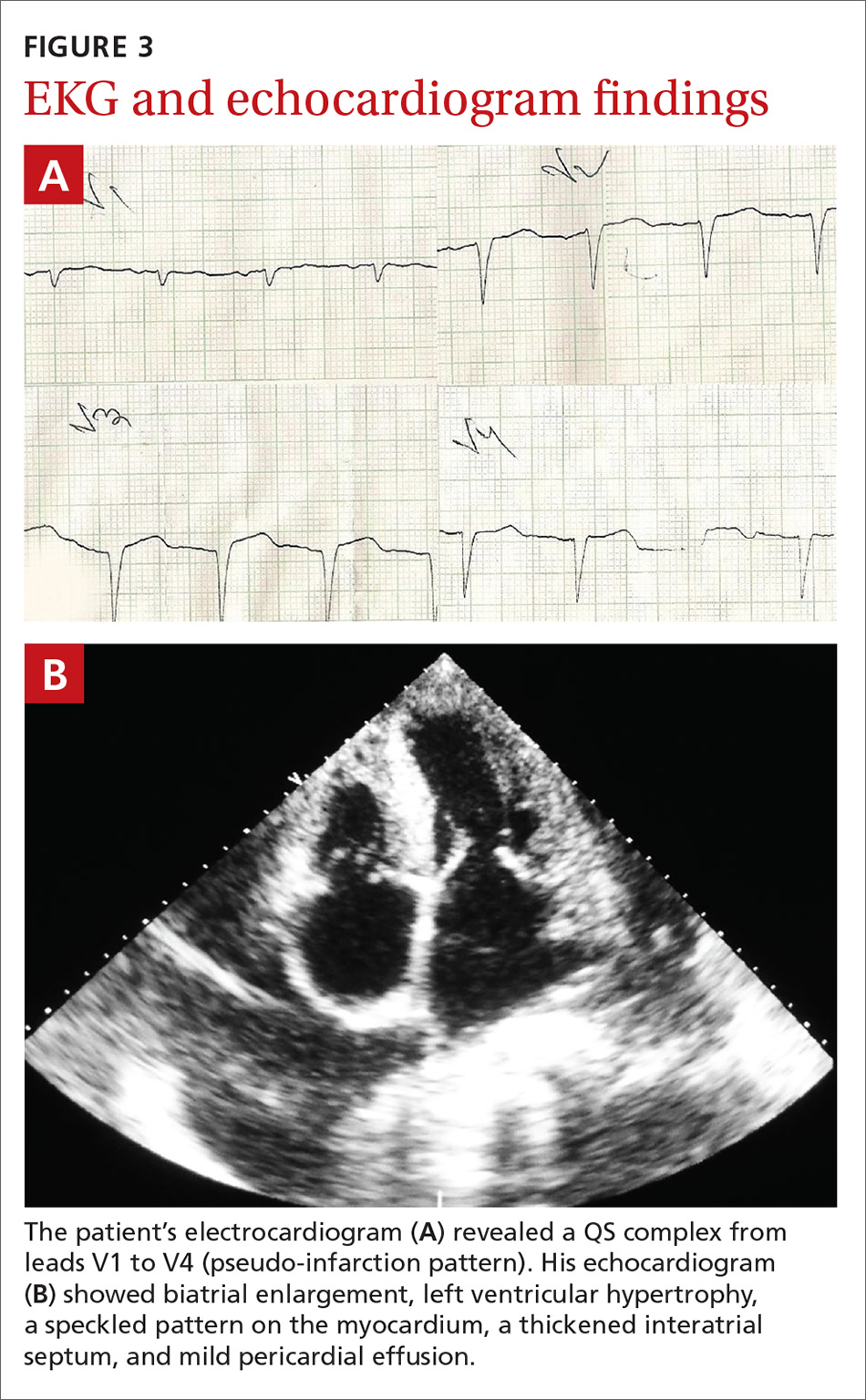

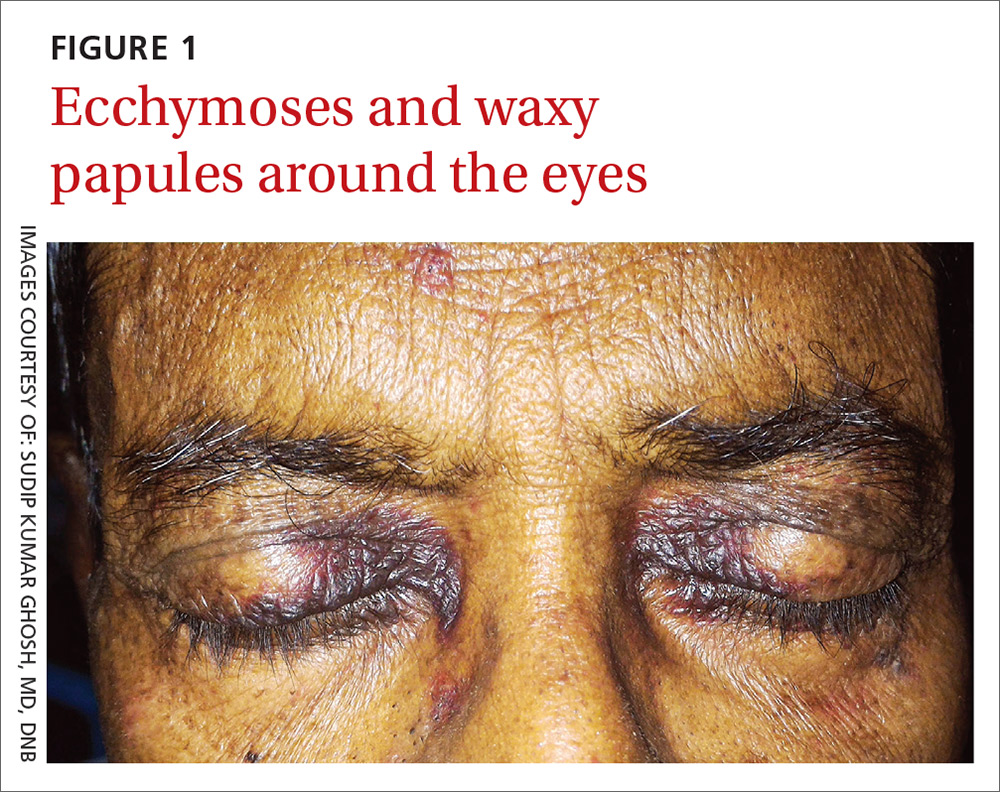

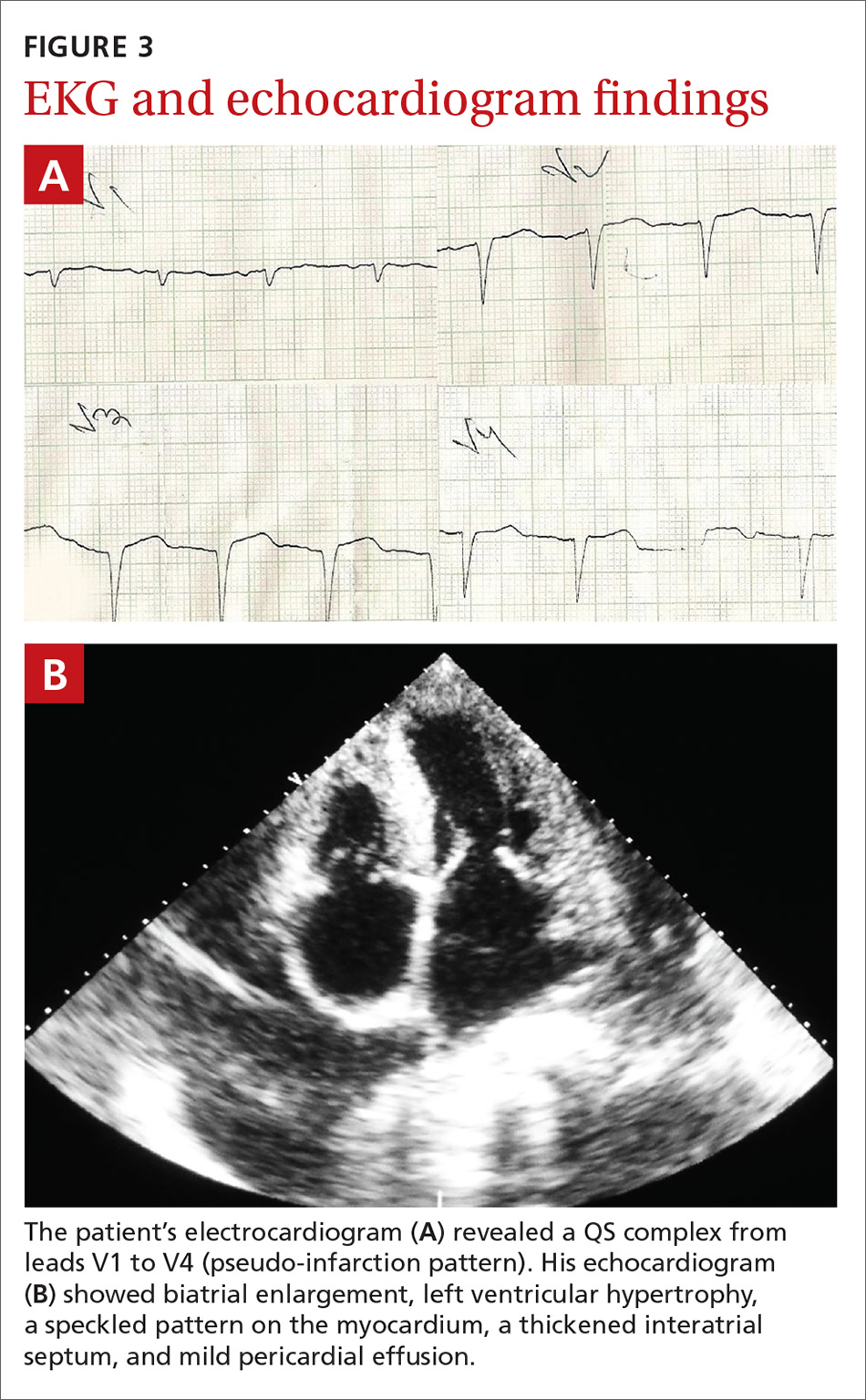

Routine hematologic and biochemical lab work was unremarkable. X-rays of the spine and skull were normal, but a chest x-ray showed mild cardiomegaly. An electrocardiogram (EKG) showed a QS complex from leads V1 to V4 (a pseudo-infarction pattern; FIGURE 3A). An echocardiogram showed biatrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 48%, a speckled pattern on the myocardium, a thickened interatrial septum, and mild pericardial effusion (FIGURE 3B).

A color Doppler revealed mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation with a restrictive pattern of mitral valve flow. Serum protein electrophoresis was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Primary systemic amyloidosis

A diagnosis of primary systemic amyloidosis was confirmed with histopathologic examination of the abdominal fat pad using Congo red stain. Clinical, imaging, and laboratory features supported this diagnosis.

Primary systemic amyloidosis (also known as light-chain amyloidosis) is the most common type of systemic amyloidosis, affecting an estimated 5 to 12 million people per year.1,2 It occurs when there is a buildup of the abnormal protein amyloid. Organs that may be affected include the heart, kidneys, skin, nerves, and liver. There are no clear environmental, racial, or genetic risk factors for this condition.

With primary systemic amyloidosis, the ecchymosis present around the eyes may also appear elsewhere on the body (pinch purpura). Other symptoms may include macroglossia; sensory and autonomic neuropathy; and concomitant renal, cardiac, and hepatic involvement. In elderly patients with these symptoms, myeloma-associated systemic amyloidosis should be ruled out.2 Histopathologic examination of the abdominal fat pad or rectum is usually diagnostic.

Systemic amyloidosis and the heart

In patients with symptoms of congestive heart failure, a finding of thick heart walls on echocardiogram may indicate cardiac amyloidosis, particularly if there is no other underlying heart disease that could explain such findings. An even stronger indicator is the additional finding of low-voltage complexes on EKG.3

Periorbital ecchymosis can be a sign of many conditions

Bilateral periorbital ecchymosis, also known as “raccoon eyes,” was an important clinical clue to the diagnosis in our patient, but multiple conditions should be considered when raccoon eyes are present.

Basal skull fracture occurs with a history of trauma. Clinical and radiologic signs of injuries can usually be found in other areas of the body.6

Periorbital cellulitis presents with unilateral erythematous periorbital swelling. A rapid increase in the patient’s temperature and swelling of tissue may occur. Movement of the extraocular muscles and visual acuity are usually normal.7

Blood dyscrasias usually involve a history of external bleeding.7 A thorough laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, platelet function tests, and a blood coagulation profile, is usually sufficient to exclude these cases.

A variety of treatment options

Clinicians have used angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, long-acting nitrates, vasodilators, and diuretics to treat cardiac amyloidosis with varying results. For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), ibutilide and amiodarone are useful antiarrhythmic drugs.3,8 In addition, experts recommend anticoagulation therapy with warfarin, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban for patients with AF because of the high risk of stroke.3,8 Symptomatic bradycardia and high-grade conduction-system disease usually require pacemaker implantation.

A guarded prognosis. The prognosis for patients with primary systemic amyloidosis is usually poor. Cardiac failure and renal failure are the major causes of death. The median survival time is 13 months, and only 5% of patients survive longer than 10 years.4,5

Our patient was prescribed furosemide 40 mg/d, ramipril 1.25 mg/d, and spironolactone 25 mg/d. Within a couple weeks, his symptoms improved. However, 3 months after being diagnosed, the patient succumbed to heart failure.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sudip Kumar Ghosh, MD, DNB, Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy, R. G. Kar Medical College, 1, Khudiram Bose Sarani, Kolkata, West Bengal 700004, India; [email protected].

1. Gertz MA. The classification and typing of amyloid deposits. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:787-789.

2. Sanchorawala V. Light-chain (AL) amyloidosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1331-1341.

3. Quarta CC, Kruger JL, Falk RH. Cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2012;126:e178-e182.

4. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Greipp PR, et al. A trial of three regimens for primary amyloidosis: colchicine alone, melphalan and prednisone, and melphalan, prednisone, and colchicine. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1202-1207.

5. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Greipp PR, et al. Long-term survival (10 years or more) in 30 patients with primary amyloidosis. Blood. 1999;93:1062-1066.

6. Somasundaram A, Laxton AW, Perrin RG. The clinical features of periorbital ecchymosis in a series of trauma patients. Injury. 2014;45:203-205.

7. Ghosh SK, Dutta A, Basu M. Raccoon eyes in a case of metastatic neuroblastoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:740-741.

8. Hassan W, Al-Sergani H, Mourad W, et al. Amyloid heart disease. New frontiers and insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:178-184.

A 54-year-old man presented at our facility with a 3-month history of exertional breathlessness and purple blotches around his eyes. Examination revealed bilateral periorbital and perioral ecchymosis, purpuric spots along his waist, and waxy papules on his eyelids (FIGURE 1). In addition, the patient had macroglossia with nodular infiltration and irregular indentations at the lateral margin of his tongue (FIGURE 2).

The patient also had a raised jugular venous pressure and prominent atrial and ventricular waves. Further examination revealed a fourth heart sound over the left ventricular apex, as well as bilateral basal rales. All other systems were normal except for mild hepatomegaly.

Routine hematologic and biochemical lab work was unremarkable. X-rays of the spine and skull were normal, but a chest x-ray showed mild cardiomegaly. An electrocardiogram (EKG) showed a QS complex from leads V1 to V4 (a pseudo-infarction pattern; FIGURE 3A). An echocardiogram showed biatrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 48%, a speckled pattern on the myocardium, a thickened interatrial septum, and mild pericardial effusion (FIGURE 3B).

A color Doppler revealed mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation with a restrictive pattern of mitral valve flow. Serum protein electrophoresis was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Primary systemic amyloidosis

A diagnosis of primary systemic amyloidosis was confirmed with histopathologic examination of the abdominal fat pad using Congo red stain. Clinical, imaging, and laboratory features supported this diagnosis.

Primary systemic amyloidosis (also known as light-chain amyloidosis) is the most common type of systemic amyloidosis, affecting an estimated 5 to 12 million people per year.1,2 It occurs when there is a buildup of the abnormal protein amyloid. Organs that may be affected include the heart, kidneys, skin, nerves, and liver. There are no clear environmental, racial, or genetic risk factors for this condition.

With primary systemic amyloidosis, the ecchymosis present around the eyes may also appear elsewhere on the body (pinch purpura). Other symptoms may include macroglossia; sensory and autonomic neuropathy; and concomitant renal, cardiac, and hepatic involvement. In elderly patients with these symptoms, myeloma-associated systemic amyloidosis should be ruled out.2 Histopathologic examination of the abdominal fat pad or rectum is usually diagnostic.

Systemic amyloidosis and the heart

In patients with symptoms of congestive heart failure, a finding of thick heart walls on echocardiogram may indicate cardiac amyloidosis, particularly if there is no other underlying heart disease that could explain such findings. An even stronger indicator is the additional finding of low-voltage complexes on EKG.3

Periorbital ecchymosis can be a sign of many conditions

Bilateral periorbital ecchymosis, also known as “raccoon eyes,” was an important clinical clue to the diagnosis in our patient, but multiple conditions should be considered when raccoon eyes are present.

Basal skull fracture occurs with a history of trauma. Clinical and radiologic signs of injuries can usually be found in other areas of the body.6

Periorbital cellulitis presents with unilateral erythematous periorbital swelling. A rapid increase in the patient’s temperature and swelling of tissue may occur. Movement of the extraocular muscles and visual acuity are usually normal.7

Blood dyscrasias usually involve a history of external bleeding.7 A thorough laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, platelet function tests, and a blood coagulation profile, is usually sufficient to exclude these cases.

A variety of treatment options

Clinicians have used angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, long-acting nitrates, vasodilators, and diuretics to treat cardiac amyloidosis with varying results. For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), ibutilide and amiodarone are useful antiarrhythmic drugs.3,8 In addition, experts recommend anticoagulation therapy with warfarin, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban for patients with AF because of the high risk of stroke.3,8 Symptomatic bradycardia and high-grade conduction-system disease usually require pacemaker implantation.

A guarded prognosis. The prognosis for patients with primary systemic amyloidosis is usually poor. Cardiac failure and renal failure are the major causes of death. The median survival time is 13 months, and only 5% of patients survive longer than 10 years.4,5

Our patient was prescribed furosemide 40 mg/d, ramipril 1.25 mg/d, and spironolactone 25 mg/d. Within a couple weeks, his symptoms improved. However, 3 months after being diagnosed, the patient succumbed to heart failure.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sudip Kumar Ghosh, MD, DNB, Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy, R. G. Kar Medical College, 1, Khudiram Bose Sarani, Kolkata, West Bengal 700004, India; [email protected].

A 54-year-old man presented at our facility with a 3-month history of exertional breathlessness and purple blotches around his eyes. Examination revealed bilateral periorbital and perioral ecchymosis, purpuric spots along his waist, and waxy papules on his eyelids (FIGURE 1). In addition, the patient had macroglossia with nodular infiltration and irregular indentations at the lateral margin of his tongue (FIGURE 2).

The patient also had a raised jugular venous pressure and prominent atrial and ventricular waves. Further examination revealed a fourth heart sound over the left ventricular apex, as well as bilateral basal rales. All other systems were normal except for mild hepatomegaly.

Routine hematologic and biochemical lab work was unremarkable. X-rays of the spine and skull were normal, but a chest x-ray showed mild cardiomegaly. An electrocardiogram (EKG) showed a QS complex from leads V1 to V4 (a pseudo-infarction pattern; FIGURE 3A). An echocardiogram showed biatrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 48%, a speckled pattern on the myocardium, a thickened interatrial septum, and mild pericardial effusion (FIGURE 3B).

A color Doppler revealed mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation with a restrictive pattern of mitral valve flow. Serum protein electrophoresis was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Primary systemic amyloidosis

A diagnosis of primary systemic amyloidosis was confirmed with histopathologic examination of the abdominal fat pad using Congo red stain. Clinical, imaging, and laboratory features supported this diagnosis.

Primary systemic amyloidosis (also known as light-chain amyloidosis) is the most common type of systemic amyloidosis, affecting an estimated 5 to 12 million people per year.1,2 It occurs when there is a buildup of the abnormal protein amyloid. Organs that may be affected include the heart, kidneys, skin, nerves, and liver. There are no clear environmental, racial, or genetic risk factors for this condition.

With primary systemic amyloidosis, the ecchymosis present around the eyes may also appear elsewhere on the body (pinch purpura). Other symptoms may include macroglossia; sensory and autonomic neuropathy; and concomitant renal, cardiac, and hepatic involvement. In elderly patients with these symptoms, myeloma-associated systemic amyloidosis should be ruled out.2 Histopathologic examination of the abdominal fat pad or rectum is usually diagnostic.

Systemic amyloidosis and the heart

In patients with symptoms of congestive heart failure, a finding of thick heart walls on echocardiogram may indicate cardiac amyloidosis, particularly if there is no other underlying heart disease that could explain such findings. An even stronger indicator is the additional finding of low-voltage complexes on EKG.3

Periorbital ecchymosis can be a sign of many conditions

Bilateral periorbital ecchymosis, also known as “raccoon eyes,” was an important clinical clue to the diagnosis in our patient, but multiple conditions should be considered when raccoon eyes are present.

Basal skull fracture occurs with a history of trauma. Clinical and radiologic signs of injuries can usually be found in other areas of the body.6

Periorbital cellulitis presents with unilateral erythematous periorbital swelling. A rapid increase in the patient’s temperature and swelling of tissue may occur. Movement of the extraocular muscles and visual acuity are usually normal.7

Blood dyscrasias usually involve a history of external bleeding.7 A thorough laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, platelet function tests, and a blood coagulation profile, is usually sufficient to exclude these cases.

A variety of treatment options

Clinicians have used angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, long-acting nitrates, vasodilators, and diuretics to treat cardiac amyloidosis with varying results. For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), ibutilide and amiodarone are useful antiarrhythmic drugs.3,8 In addition, experts recommend anticoagulation therapy with warfarin, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban for patients with AF because of the high risk of stroke.3,8 Symptomatic bradycardia and high-grade conduction-system disease usually require pacemaker implantation.

A guarded prognosis. The prognosis for patients with primary systemic amyloidosis is usually poor. Cardiac failure and renal failure are the major causes of death. The median survival time is 13 months, and only 5% of patients survive longer than 10 years.4,5

Our patient was prescribed furosemide 40 mg/d, ramipril 1.25 mg/d, and spironolactone 25 mg/d. Within a couple weeks, his symptoms improved. However, 3 months after being diagnosed, the patient succumbed to heart failure.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sudip Kumar Ghosh, MD, DNB, Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy, R. G. Kar Medical College, 1, Khudiram Bose Sarani, Kolkata, West Bengal 700004, India; [email protected].

1. Gertz MA. The classification and typing of amyloid deposits. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:787-789.

2. Sanchorawala V. Light-chain (AL) amyloidosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1331-1341.

3. Quarta CC, Kruger JL, Falk RH. Cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2012;126:e178-e182.

4. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Greipp PR, et al. A trial of three regimens for primary amyloidosis: colchicine alone, melphalan and prednisone, and melphalan, prednisone, and colchicine. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1202-1207.

5. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Greipp PR, et al. Long-term survival (10 years or more) in 30 patients with primary amyloidosis. Blood. 1999;93:1062-1066.

6. Somasundaram A, Laxton AW, Perrin RG. The clinical features of periorbital ecchymosis in a series of trauma patients. Injury. 2014;45:203-205.

7. Ghosh SK, Dutta A, Basu M. Raccoon eyes in a case of metastatic neuroblastoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:740-741.

8. Hassan W, Al-Sergani H, Mourad W, et al. Amyloid heart disease. New frontiers and insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:178-184.

1. Gertz MA. The classification and typing of amyloid deposits. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:787-789.

2. Sanchorawala V. Light-chain (AL) amyloidosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1331-1341.

3. Quarta CC, Kruger JL, Falk RH. Cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2012;126:e178-e182.

4. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Greipp PR, et al. A trial of three regimens for primary amyloidosis: colchicine alone, melphalan and prednisone, and melphalan, prednisone, and colchicine. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1202-1207.

5. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Greipp PR, et al. Long-term survival (10 years or more) in 30 patients with primary amyloidosis. Blood. 1999;93:1062-1066.

6. Somasundaram A, Laxton AW, Perrin RG. The clinical features of periorbital ecchymosis in a series of trauma patients. Injury. 2014;45:203-205.

7. Ghosh SK, Dutta A, Basu M. Raccoon eyes in a case of metastatic neuroblastoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:740-741.

8. Hassan W, Al-Sergani H, Mourad W, et al. Amyloid heart disease. New frontiers and insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:178-184.

Worsening rash

The FP suspected pustular psoriasis, which was confirmed by a dermatologist the patient saw the following day. The dermatologist confirmed this diagnosis by performing a 4-mm punch biopsy, which included an area of new pustules on the patient’s arm. When a rash is extensive, it’s best to biopsy new lesions from the upper body, rather than old lesions below the waist.

Pustular psoriasis can lead to confluent pustules, a condition in which the skin peels off in sheets, resulting in dehydration and a risk of sepsis. This is why you shouldn’t prescribe oral prednisone for any rash before you know that it’s not psoriasis. While oral prednisone may be an effective treatment for many types of dermatitis, it can exacerbate psoriasis (as it did with this patient), and is therefore not an effective or safe treatment for it.

Knowing that pustular psoriasis can become a dermatologic emergency, the FP prescribed oral cyclosporine for the most rapid result. The patient’s blood pressure and kidney function were normal, so it was only necessary for the FP to order baseline laboratory tests. At the follow-up appointment 2 days later, the patient’s condition was already improving and there were no new pustules. Her vital signs remained stable and the pathology report confirmed pustular psoriasis.

The dermatologist planned to transition the patient from cyclosporine to acitretin, determining it was safe to prescribe an oral retinoid. The patient’s hysterectomy 2 years earlier also eliminated concerns about acitretin’s teratogenic potency. The dermatologist prescribed acitretin with directions for the patient to begin taking it in one week, tapering off the cyclosporine once the pustular psoriasis was significantly better.

After a month, the patient was off of cyclosporine completely. Her skin was clear while using daily acitretin. Monitoring of lab tests did not show any adverse effects of the patient using these 2 potentially toxic medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected pustular psoriasis, which was confirmed by a dermatologist the patient saw the following day. The dermatologist confirmed this diagnosis by performing a 4-mm punch biopsy, which included an area of new pustules on the patient’s arm. When a rash is extensive, it’s best to biopsy new lesions from the upper body, rather than old lesions below the waist.

Pustular psoriasis can lead to confluent pustules, a condition in which the skin peels off in sheets, resulting in dehydration and a risk of sepsis. This is why you shouldn’t prescribe oral prednisone for any rash before you know that it’s not psoriasis. While oral prednisone may be an effective treatment for many types of dermatitis, it can exacerbate psoriasis (as it did with this patient), and is therefore not an effective or safe treatment for it.

Knowing that pustular psoriasis can become a dermatologic emergency, the FP prescribed oral cyclosporine for the most rapid result. The patient’s blood pressure and kidney function were normal, so it was only necessary for the FP to order baseline laboratory tests. At the follow-up appointment 2 days later, the patient’s condition was already improving and there were no new pustules. Her vital signs remained stable and the pathology report confirmed pustular psoriasis.

The dermatologist planned to transition the patient from cyclosporine to acitretin, determining it was safe to prescribe an oral retinoid. The patient’s hysterectomy 2 years earlier also eliminated concerns about acitretin’s teratogenic potency. The dermatologist prescribed acitretin with directions for the patient to begin taking it in one week, tapering off the cyclosporine once the pustular psoriasis was significantly better.

After a month, the patient was off of cyclosporine completely. Her skin was clear while using daily acitretin. Monitoring of lab tests did not show any adverse effects of the patient using these 2 potentially toxic medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected pustular psoriasis, which was confirmed by a dermatologist the patient saw the following day. The dermatologist confirmed this diagnosis by performing a 4-mm punch biopsy, which included an area of new pustules on the patient’s arm. When a rash is extensive, it’s best to biopsy new lesions from the upper body, rather than old lesions below the waist.

Pustular psoriasis can lead to confluent pustules, a condition in which the skin peels off in sheets, resulting in dehydration and a risk of sepsis. This is why you shouldn’t prescribe oral prednisone for any rash before you know that it’s not psoriasis. While oral prednisone may be an effective treatment for many types of dermatitis, it can exacerbate psoriasis (as it did with this patient), and is therefore not an effective or safe treatment for it.

Knowing that pustular psoriasis can become a dermatologic emergency, the FP prescribed oral cyclosporine for the most rapid result. The patient’s blood pressure and kidney function were normal, so it was only necessary for the FP to order baseline laboratory tests. At the follow-up appointment 2 days later, the patient’s condition was already improving and there were no new pustules. Her vital signs remained stable and the pathology report confirmed pustular psoriasis.

The dermatologist planned to transition the patient from cyclosporine to acitretin, determining it was safe to prescribe an oral retinoid. The patient’s hysterectomy 2 years earlier also eliminated concerns about acitretin’s teratogenic potency. The dermatologist prescribed acitretin with directions for the patient to begin taking it in one week, tapering off the cyclosporine once the pustular psoriasis was significantly better.

After a month, the patient was off of cyclosporine completely. Her skin was clear while using daily acitretin. Monitoring of lab tests did not show any adverse effects of the patient using these 2 potentially toxic medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash on abdomen

Based on the negative KOH and the nail pits, the FP made a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis. This condition can present in an annular pattern resembling tinea corporis. The combination of negative KOH and nail pits are enough to diagnose plaque psoriasis without a biopsy. Otherwise, a 4-mm punch biopsy of the area with erythema and scale would confirm the diagnosis.

Plaque psoriasis is typically treated using a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. Although repeated use of steroids in cases of atopic dermatitis can lead to skin atrophy, this is less common when treating psoriasis. If skin atrophy is still a concern, an alternative to topical steroids is a topical vitamin D preparation.

Vitamin D preparations are typically more expensive than steroids and require prior authorization, but there is one generic preparation (calcipotriene) that is more affordable than its brand-name counterparts. Another nonsystemic treatment to consider when treating plaque psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis is narrowband ultraviolet B therapy.

One risk factor for psoriasis is being overweight. In this case, the FP counseled the patient on weight loss. The FP then prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily (especially after bathing).

At a follow-up appointment a month later, there was about 70% clearance of the lesions. For the stubborn areas, the FP prescribed a higher-potency steroid, 0.05% clobetasol ointment, to be applied twice daily. As the cost of clobetasol has risen over the past 2 years, alternatives that may be covered by insurance include augmented betamethasone and halobetasol.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the negative KOH and the nail pits, the FP made a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis. This condition can present in an annular pattern resembling tinea corporis. The combination of negative KOH and nail pits are enough to diagnose plaque psoriasis without a biopsy. Otherwise, a 4-mm punch biopsy of the area with erythema and scale would confirm the diagnosis.

Plaque psoriasis is typically treated using a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. Although repeated use of steroids in cases of atopic dermatitis can lead to skin atrophy, this is less common when treating psoriasis. If skin atrophy is still a concern, an alternative to topical steroids is a topical vitamin D preparation.

Vitamin D preparations are typically more expensive than steroids and require prior authorization, but there is one generic preparation (calcipotriene) that is more affordable than its brand-name counterparts. Another nonsystemic treatment to consider when treating plaque psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis is narrowband ultraviolet B therapy.

One risk factor for psoriasis is being overweight. In this case, the FP counseled the patient on weight loss. The FP then prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily (especially after bathing).

At a follow-up appointment a month later, there was about 70% clearance of the lesions. For the stubborn areas, the FP prescribed a higher-potency steroid, 0.05% clobetasol ointment, to be applied twice daily. As the cost of clobetasol has risen over the past 2 years, alternatives that may be covered by insurance include augmented betamethasone and halobetasol.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the negative KOH and the nail pits, the FP made a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis. This condition can present in an annular pattern resembling tinea corporis. The combination of negative KOH and nail pits are enough to diagnose plaque psoriasis without a biopsy. Otherwise, a 4-mm punch biopsy of the area with erythema and scale would confirm the diagnosis.

Plaque psoriasis is typically treated using a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. Although repeated use of steroids in cases of atopic dermatitis can lead to skin atrophy, this is less common when treating psoriasis. If skin atrophy is still a concern, an alternative to topical steroids is a topical vitamin D preparation.

Vitamin D preparations are typically more expensive than steroids and require prior authorization, but there is one generic preparation (calcipotriene) that is more affordable than its brand-name counterparts. Another nonsystemic treatment to consider when treating plaque psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis is narrowband ultraviolet B therapy.

One risk factor for psoriasis is being overweight. In this case, the FP counseled the patient on weight loss. The FP then prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily (especially after bathing).

At a follow-up appointment a month later, there was about 70% clearance of the lesions. For the stubborn areas, the FP prescribed a higher-potency steroid, 0.05% clobetasol ointment, to be applied twice daily. As the cost of clobetasol has risen over the past 2 years, alternatives that may be covered by insurance include augmented betamethasone and halobetasol.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash and skin discoloration

The FP diagnosed plaque psoriasis as the cause of the erythema and scale. The FP suspected vitiligo or postinflammatory hypopigmentation as the cause of the discoloration. (It’s not unusual for patients with psoriasis to have vitiligo, as well.) The FP referred the patient to a dermatologist for a diagnosis, but never received feedback.

When diagnosing psoriasis, it’s crucial to determine if it’s accompanied by psoriatic arthritis. That’s because the presence of arthritis requires systemic therapy to prevent further joint damage. In this case, the patient denied having joint pain and morning stiffness.

Smoking tobacco and drinking excessive amounts of alcohol are both risk factors for psoriasis. The FP started treatment by discussing lifestyle changes and emphasizing the importance of abstinence from tobacco. While the patient wouldn’t set a quit date, he agreed to cut his intake down to half a pack of cigarettes a day. He also agreed to limit his consumption of alcohol to 2 beers a day. In addition, the FP prescribed a 454-g tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. The ointment is more effective, but some patients may prefer the less greasy feel of a cream.

At a follow-up appointment a year later, the patient’s plaque psoriasis was under better control. His hands, however, showed extensive depigmentation. This confirmed the diagnosis of vitiligo, but the patient was not bothered by the appearance of it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed plaque psoriasis as the cause of the erythema and scale. The FP suspected vitiligo or postinflammatory hypopigmentation as the cause of the discoloration. (It’s not unusual for patients with psoriasis to have vitiligo, as well.) The FP referred the patient to a dermatologist for a diagnosis, but never received feedback.

When diagnosing psoriasis, it’s crucial to determine if it’s accompanied by psoriatic arthritis. That’s because the presence of arthritis requires systemic therapy to prevent further joint damage. In this case, the patient denied having joint pain and morning stiffness.

Smoking tobacco and drinking excessive amounts of alcohol are both risk factors for psoriasis. The FP started treatment by discussing lifestyle changes and emphasizing the importance of abstinence from tobacco. While the patient wouldn’t set a quit date, he agreed to cut his intake down to half a pack of cigarettes a day. He also agreed to limit his consumption of alcohol to 2 beers a day. In addition, the FP prescribed a 454-g tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. The ointment is more effective, but some patients may prefer the less greasy feel of a cream.

At a follow-up appointment a year later, the patient’s plaque psoriasis was under better control. His hands, however, showed extensive depigmentation. This confirmed the diagnosis of vitiligo, but the patient was not bothered by the appearance of it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed plaque psoriasis as the cause of the erythema and scale. The FP suspected vitiligo or postinflammatory hypopigmentation as the cause of the discoloration. (It’s not unusual for patients with psoriasis to have vitiligo, as well.) The FP referred the patient to a dermatologist for a diagnosis, but never received feedback.

When diagnosing psoriasis, it’s crucial to determine if it’s accompanied by psoriatic arthritis. That’s because the presence of arthritis requires systemic therapy to prevent further joint damage. In this case, the patient denied having joint pain and morning stiffness.

Smoking tobacco and drinking excessive amounts of alcohol are both risk factors for psoriasis. The FP started treatment by discussing lifestyle changes and emphasizing the importance of abstinence from tobacco. While the patient wouldn’t set a quit date, he agreed to cut his intake down to half a pack of cigarettes a day. He also agreed to limit his consumption of alcohol to 2 beers a day. In addition, the FP prescribed a 454-g tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. The ointment is more effective, but some patients may prefer the less greasy feel of a cream.

At a follow-up appointment a year later, the patient’s plaque psoriasis was under better control. His hands, however, showed extensive depigmentation. This confirmed the diagnosis of vitiligo, but the patient was not bothered by the appearance of it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Hand pain and rash

The FP diagnosed psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis in this patient. The psoriatic arthritis had already caused swan neck deformities of multiple fingers, consistent with the mutilans subtype of psoriatic arthritis. The FP was aware that this patient needed to see a dermatologist and/or rheumatologist due to the severity of the arthritis.

Patients like this need systemic therapy with methotrexate, apremilast, or an anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha-inhibitor on an ongoing basis to both treat the arthritis and attempt to prevent further joint destruction. This will also treat the extensive plaque psoriasis that may accompany psoriatic arthritis. Most patients with psoriatic arthritis also have nail involvement (as did this patient), and it may respond to systemic treatment, as well.

Since systemic treatment is frequently outside the FP’s scope of practice, referral to a specialist is essential. The FP can, however, start topical therapy for the plaque psoriasis. This can be initiated with mid- to high-potency topical steroids.

It may be tempting to give a patient like this oral prednisone or an intramuscular steroid, but such therapy should be avoided because it can result in rebound pustular psoriasis. (These treatments do not work well enough to take the risk.)

In this case, the FP prescribed a 60-g tube of 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied to the worst areas, along with a 1-lb tub (454 g) of 0.1% triamcinolone to be applied to the other plaques. The patient was glad to receive treatment for his psoriasis and looked forward to seeing a specialist for treatment of his arthritis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis in this patient. The psoriatic arthritis had already caused swan neck deformities of multiple fingers, consistent with the mutilans subtype of psoriatic arthritis. The FP was aware that this patient needed to see a dermatologist and/or rheumatologist due to the severity of the arthritis.

Patients like this need systemic therapy with methotrexate, apremilast, or an anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha-inhibitor on an ongoing basis to both treat the arthritis and attempt to prevent further joint destruction. This will also treat the extensive plaque psoriasis that may accompany psoriatic arthritis. Most patients with psoriatic arthritis also have nail involvement (as did this patient), and it may respond to systemic treatment, as well.

Since systemic treatment is frequently outside the FP’s scope of practice, referral to a specialist is essential. The FP can, however, start topical therapy for the plaque psoriasis. This can be initiated with mid- to high-potency topical steroids.

It may be tempting to give a patient like this oral prednisone or an intramuscular steroid, but such therapy should be avoided because it can result in rebound pustular psoriasis. (These treatments do not work well enough to take the risk.)

In this case, the FP prescribed a 60-g tube of 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied to the worst areas, along with a 1-lb tub (454 g) of 0.1% triamcinolone to be applied to the other plaques. The patient was glad to receive treatment for his psoriasis and looked forward to seeing a specialist for treatment of his arthritis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis in this patient. The psoriatic arthritis had already caused swan neck deformities of multiple fingers, consistent with the mutilans subtype of psoriatic arthritis. The FP was aware that this patient needed to see a dermatologist and/or rheumatologist due to the severity of the arthritis.