User login

Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp

An 8-year-old boy was brought by his family to our clinic for treatment of 2 pruritic, inflammatory masses on his scalp. He’d had the masses for one month, and they hadn’t responded to an unknown treatment administered at a health center in Afghanistan. The edematous lesions were ulcerated with a crust, and had a diameter of approximately 6 cm and 4 cm on the frontal and occipital scalp, respectively (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

The boy also had a well-demarcated, erythematous macule with scales on his face, but no other symptoms. The boy’s brother and sister also complained of pruritic, erythematous papules on their arms and faces. The family denied raising or having any recent contact with animals.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Tinea capitis and erythema nodosum

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (The patient’s brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.) Our patient’s diagnosis was confirmed when he rapidly responded to treatment with the antifungal fluconazole. After the first week of this treatment, he complained of tender, erythematous nodules on the anterior surface of his lower legs, which we diagnosed as erythema nodosum (FIGURE 2).

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion. The kerion can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.1

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than age 10 years, with a peak incidence among African American boys.2 Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.2

Differential diagnosis includes bacterial infections, psoriasis

Bacterial infections can cause abscesses or carbuncles on the scalp with tender and fluctuant changes that can also be accompanied by fever. However, because our patient was afebrile and relatively well, and the scalp lesions were nontender and without pus, a bacterial infection was unlikely.

Scalp psoriasis appears as raised, erythematous, dry and scaly patches, and not as inflammatory boggy masses (as was observed in our patient).

Skin cancer such as squamous cell carcinoma can present as erythematous, crusted, or scaly patches on sun-exposed skin. However, our patient’s lesions were too large to be malignant.4 In addition, skin cancer is rare in children.4

Oral antifungal medications are usually first-line treatment

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective.5-6

Erythema nodosum usually resolves without treatment, but should be observed until the underlying cause is treated.3

Our patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. After 2 weeks of treatment with oral fluconazole, he had hairless lesions on his scalp (FIGURE 3). The tender, erythematous nodules on his legs resolved spontaneously. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and our patient’s scalp lesions completely resolved after 6 weeks.

The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kyoungwoo Kim, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital, 9, Mareunnae-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul 100-032, Republic of Korea; [email protected]

1. Sohnle P. Dermatophytosis. In: Murphy J, Friedman H, Bendinelli M, eds. Fungal Infections and Immune Responses: Springer US;1993:2747.

2. Kao GF. Tinea capitis: Overview. Medscape Web site. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1091351-overview#showall. Accessed May 5, 2015.

3. Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

4. Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

5. Kakourou T, Uksal U; European Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Guidelines for the management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:226-228.

6. González U, Seaton T, Bergus G, et al. Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD004685.

7. Gupta AK, Dlova N, Taborda P, et al. Once weekly fluconazole is effective in children in the treatment of tinea capitis: a prospective, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:965-968.

8. Gupta AK, Adam P, Hofstader SL, et al. Intermittent short duration therapy with fluconazole is effective for tinea capitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:304-306.

An 8-year-old boy was brought by his family to our clinic for treatment of 2 pruritic, inflammatory masses on his scalp. He’d had the masses for one month, and they hadn’t responded to an unknown treatment administered at a health center in Afghanistan. The edematous lesions were ulcerated with a crust, and had a diameter of approximately 6 cm and 4 cm on the frontal and occipital scalp, respectively (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

The boy also had a well-demarcated, erythematous macule with scales on his face, but no other symptoms. The boy’s brother and sister also complained of pruritic, erythematous papules on their arms and faces. The family denied raising or having any recent contact with animals.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Tinea capitis and erythema nodosum

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (The patient’s brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.) Our patient’s diagnosis was confirmed when he rapidly responded to treatment with the antifungal fluconazole. After the first week of this treatment, he complained of tender, erythematous nodules on the anterior surface of his lower legs, which we diagnosed as erythema nodosum (FIGURE 2).

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion. The kerion can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.1

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than age 10 years, with a peak incidence among African American boys.2 Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.2

Differential diagnosis includes bacterial infections, psoriasis

Bacterial infections can cause abscesses or carbuncles on the scalp with tender and fluctuant changes that can also be accompanied by fever. However, because our patient was afebrile and relatively well, and the scalp lesions were nontender and without pus, a bacterial infection was unlikely.

Scalp psoriasis appears as raised, erythematous, dry and scaly patches, and not as inflammatory boggy masses (as was observed in our patient).

Skin cancer such as squamous cell carcinoma can present as erythematous, crusted, or scaly patches on sun-exposed skin. However, our patient’s lesions were too large to be malignant.4 In addition, skin cancer is rare in children.4

Oral antifungal medications are usually first-line treatment

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective.5-6

Erythema nodosum usually resolves without treatment, but should be observed until the underlying cause is treated.3

Our patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. After 2 weeks of treatment with oral fluconazole, he had hairless lesions on his scalp (FIGURE 3). The tender, erythematous nodules on his legs resolved spontaneously. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and our patient’s scalp lesions completely resolved after 6 weeks.

The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kyoungwoo Kim, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital, 9, Mareunnae-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul 100-032, Republic of Korea; [email protected]

An 8-year-old boy was brought by his family to our clinic for treatment of 2 pruritic, inflammatory masses on his scalp. He’d had the masses for one month, and they hadn’t responded to an unknown treatment administered at a health center in Afghanistan. The edematous lesions were ulcerated with a crust, and had a diameter of approximately 6 cm and 4 cm on the frontal and occipital scalp, respectively (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

The boy also had a well-demarcated, erythematous macule with scales on his face, but no other symptoms. The boy’s brother and sister also complained of pruritic, erythematous papules on their arms and faces. The family denied raising or having any recent contact with animals.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Tinea capitis and erythema nodosum

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (The patient’s brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.) Our patient’s diagnosis was confirmed when he rapidly responded to treatment with the antifungal fluconazole. After the first week of this treatment, he complained of tender, erythematous nodules on the anterior surface of his lower legs, which we diagnosed as erythema nodosum (FIGURE 2).

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion. The kerion can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.1

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than age 10 years, with a peak incidence among African American boys.2 Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.2

Differential diagnosis includes bacterial infections, psoriasis

Bacterial infections can cause abscesses or carbuncles on the scalp with tender and fluctuant changes that can also be accompanied by fever. However, because our patient was afebrile and relatively well, and the scalp lesions were nontender and without pus, a bacterial infection was unlikely.

Scalp psoriasis appears as raised, erythematous, dry and scaly patches, and not as inflammatory boggy masses (as was observed in our patient).

Skin cancer such as squamous cell carcinoma can present as erythematous, crusted, or scaly patches on sun-exposed skin. However, our patient’s lesions were too large to be malignant.4 In addition, skin cancer is rare in children.4

Oral antifungal medications are usually first-line treatment

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective.5-6

Erythema nodosum usually resolves without treatment, but should be observed until the underlying cause is treated.3

Our patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. After 2 weeks of treatment with oral fluconazole, he had hairless lesions on his scalp (FIGURE 3). The tender, erythematous nodules on his legs resolved spontaneously. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and our patient’s scalp lesions completely resolved after 6 weeks.

The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kyoungwoo Kim, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital, 9, Mareunnae-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul 100-032, Republic of Korea; [email protected]

1. Sohnle P. Dermatophytosis. In: Murphy J, Friedman H, Bendinelli M, eds. Fungal Infections and Immune Responses: Springer US;1993:2747.

2. Kao GF. Tinea capitis: Overview. Medscape Web site. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1091351-overview#showall. Accessed May 5, 2015.

3. Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

4. Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

5. Kakourou T, Uksal U; European Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Guidelines for the management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:226-228.

6. González U, Seaton T, Bergus G, et al. Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD004685.

7. Gupta AK, Dlova N, Taborda P, et al. Once weekly fluconazole is effective in children in the treatment of tinea capitis: a prospective, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:965-968.

8. Gupta AK, Adam P, Hofstader SL, et al. Intermittent short duration therapy with fluconazole is effective for tinea capitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:304-306.

1. Sohnle P. Dermatophytosis. In: Murphy J, Friedman H, Bendinelli M, eds. Fungal Infections and Immune Responses: Springer US;1993:2747.

2. Kao GF. Tinea capitis: Overview. Medscape Web site. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1091351-overview#showall. Accessed May 5, 2015.

3. Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

4. Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

5. Kakourou T, Uksal U; European Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Guidelines for the management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:226-228.

6. González U, Seaton T, Bergus G, et al. Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD004685.

7. Gupta AK, Dlova N, Taborda P, et al. Once weekly fluconazole is effective in children in the treatment of tinea capitis: a prospective, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:965-968.

8. Gupta AK, Adam P, Hofstader SL, et al. Intermittent short duration therapy with fluconazole is effective for tinea capitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:304-306.

Tender, swollen elbow

The FP suspected that the patient had septic olecranon bursitis and he was particularly concerned about the patient’s immunosuppressed status. Aspiration of the bursa demonstrated a yellow-green fluid with white cells and bacteria seen under light microscopy. The FP admitted the patient to the hospital for IV vancomycin and sent the fluid for culture. The laboratory reported gram-positive cocci on the Gram stain.

Olecranon bursitis can be aseptic—from repetitive trauma or systemic disease—or septic, most commonly from gram-positive bacteria.

Bursal fluid findings can help differentiate septic from aseptic olecranon bursitis.

- The white blood cell (WBC) count is >30,000 in septic bursitis and <28,000 in aseptic bursitis. However, an elevated WBC count is also seen in rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

- Neutrophils are seen in septic bursitis; monocytes are seen in aseptic bursitis.

- Glucose is <50% of serum glucose in septic bursitis. It is >70% of serum glucose in aseptic bursitis.

- Gram-positive organisms are found on the Gram stain in septic bursitis.

Aseptic olecranon bursitis is treated with an elbow pad, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ice. Septic olecranon bursitis is treated with drainage and antibiotics. Septic bursitis should be treated until the fluid is sterile. Some experts recommend re-aspiration after 4 to 5 days of antibiotics and continuing antibiotics for 5 days after the fluid is sterile.

In this case, the patient was doing better 3 days after being admitted. The culture was reported as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The organism was sensitive to doxycycline and the patient was sent home on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily to complete a 2-week course of antibiotics.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Olecranon bursitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:596-600.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that the patient had septic olecranon bursitis and he was particularly concerned about the patient’s immunosuppressed status. Aspiration of the bursa demonstrated a yellow-green fluid with white cells and bacteria seen under light microscopy. The FP admitted the patient to the hospital for IV vancomycin and sent the fluid for culture. The laboratory reported gram-positive cocci on the Gram stain.

Olecranon bursitis can be aseptic—from repetitive trauma or systemic disease—or septic, most commonly from gram-positive bacteria.

Bursal fluid findings can help differentiate septic from aseptic olecranon bursitis.

- The white blood cell (WBC) count is >30,000 in septic bursitis and <28,000 in aseptic bursitis. However, an elevated WBC count is also seen in rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

- Neutrophils are seen in septic bursitis; monocytes are seen in aseptic bursitis.

- Glucose is <50% of serum glucose in septic bursitis. It is >70% of serum glucose in aseptic bursitis.

- Gram-positive organisms are found on the Gram stain in septic bursitis.

Aseptic olecranon bursitis is treated with an elbow pad, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ice. Septic olecranon bursitis is treated with drainage and antibiotics. Septic bursitis should be treated until the fluid is sterile. Some experts recommend re-aspiration after 4 to 5 days of antibiotics and continuing antibiotics for 5 days after the fluid is sterile.

In this case, the patient was doing better 3 days after being admitted. The culture was reported as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The organism was sensitive to doxycycline and the patient was sent home on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily to complete a 2-week course of antibiotics.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Olecranon bursitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:596-600.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that the patient had septic olecranon bursitis and he was particularly concerned about the patient’s immunosuppressed status. Aspiration of the bursa demonstrated a yellow-green fluid with white cells and bacteria seen under light microscopy. The FP admitted the patient to the hospital for IV vancomycin and sent the fluid for culture. The laboratory reported gram-positive cocci on the Gram stain.

Olecranon bursitis can be aseptic—from repetitive trauma or systemic disease—or septic, most commonly from gram-positive bacteria.

Bursal fluid findings can help differentiate septic from aseptic olecranon bursitis.

- The white blood cell (WBC) count is >30,000 in septic bursitis and <28,000 in aseptic bursitis. However, an elevated WBC count is also seen in rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

- Neutrophils are seen in septic bursitis; monocytes are seen in aseptic bursitis.

- Glucose is <50% of serum glucose in septic bursitis. It is >70% of serum glucose in aseptic bursitis.

- Gram-positive organisms are found on the Gram stain in septic bursitis.

Aseptic olecranon bursitis is treated with an elbow pad, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ice. Septic olecranon bursitis is treated with drainage and antibiotics. Septic bursitis should be treated until the fluid is sterile. Some experts recommend re-aspiration after 4 to 5 days of antibiotics and continuing antibiotics for 5 days after the fluid is sterile.

In this case, the patient was doing better 3 days after being admitted. The culture was reported as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The organism was sensitive to doxycycline and the patient was sent home on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily to complete a 2-week course of antibiotics.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Olecranon bursitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:596-600.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Severely swollen finger

The patient was told that this was an attack of gout, based on the x-rays that showed several tophi (monosodium urate deposits) in the soft tissue over the third distal interphalangeal joint. Subchondral bone destruction was also seen as typical punched out lesions under the tophi.

The patient was treated with oral colchicine for the acute attack and then sent to Rheumatology for further management. Her serum uric acid level was also elevated, as expected.

Photos courtesy of JM Geiderman, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Smith M. Gout. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:590-595.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The patient was told that this was an attack of gout, based on the x-rays that showed several tophi (monosodium urate deposits) in the soft tissue over the third distal interphalangeal joint. Subchondral bone destruction was also seen as typical punched out lesions under the tophi.

The patient was treated with oral colchicine for the acute attack and then sent to Rheumatology for further management. Her serum uric acid level was also elevated, as expected.

Photos courtesy of JM Geiderman, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Smith M. Gout. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:590-595.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The patient was told that this was an attack of gout, based on the x-rays that showed several tophi (monosodium urate deposits) in the soft tissue over the third distal interphalangeal joint. Subchondral bone destruction was also seen as typical punched out lesions under the tophi.

The patient was treated with oral colchicine for the acute attack and then sent to Rheumatology for further management. Her serum uric acid level was also elevated, as expected.

Photos courtesy of JM Geiderman, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Smith M. Gout. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:590-595.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Red rash and finger deformities

The family physician (FP) diagnosed plaque psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis mutilans in this patient, a severe, deforming type of arthritis that usually affects joints in the hands and feet.

His psoriatic arthritis had caused swan-neck deformities with involvement of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Both hands were involved, but the patient’s right hand was worse. Radiographs of the hands showed periarticular erosions with new bone formation.

The patient was clearly disabled based on the severe deformities of his hands. Appropriate treatment to prevent progression of the mutilating arthritis would require systemic medications that need monitoring with blood tests (and health insurance to afford the medications and lab tests).

The FP treated the patient with topical steroids and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at the shelter clinic. The patient was given information about seeing a caseworker the following morning. Choices for therapy included methotrexate and the new biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Ankylosing spondylitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:580-584.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) diagnosed plaque psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis mutilans in this patient, a severe, deforming type of arthritis that usually affects joints in the hands and feet.

His psoriatic arthritis had caused swan-neck deformities with involvement of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Both hands were involved, but the patient’s right hand was worse. Radiographs of the hands showed periarticular erosions with new bone formation.

The patient was clearly disabled based on the severe deformities of his hands. Appropriate treatment to prevent progression of the mutilating arthritis would require systemic medications that need monitoring with blood tests (and health insurance to afford the medications and lab tests).

The FP treated the patient with topical steroids and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at the shelter clinic. The patient was given information about seeing a caseworker the following morning. Choices for therapy included methotrexate and the new biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Ankylosing spondylitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:580-584.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) diagnosed plaque psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis mutilans in this patient, a severe, deforming type of arthritis that usually affects joints in the hands and feet.

His psoriatic arthritis had caused swan-neck deformities with involvement of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Both hands were involved, but the patient’s right hand was worse. Radiographs of the hands showed periarticular erosions with new bone formation.

The patient was clearly disabled based on the severe deformities of his hands. Appropriate treatment to prevent progression of the mutilating arthritis would require systemic medications that need monitoring with blood tests (and health insurance to afford the medications and lab tests).

The FP treated the patient with topical steroids and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at the shelter clinic. The patient was given information about seeing a caseworker the following morning. Choices for therapy included methotrexate and the new biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Ankylosing spondylitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:580-584.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Lumps on forearm

The FP recognized that this was a case of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with rheumatoid nodules. She ordered bilateral hand x-rays and referred the patient to rheumatology. The patient was told that rheumatoid nodules are not harmful and surgery wasn’t recommended. The FP also ordered appropriate blood tests to confirm the impression of RA, which included:

- a rheumatoid factor (RF) test (positive in many connective tissue, neoplastic, and infectious diseases; positive in 70% of RA patients)

- an anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) test (high specificity for RA: Often present before definitive diagnosis can be made; presence predicts arthritis development)

- C-reactive protein (CRP) >0.7 pg/mL, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >30 mm/h

- complete blood count (indicators of RA: normocytic or microcytic anemia, thrombocytosis)

The 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria uses a scoring system to identify patients with RA. A score of ≥6/10 meets the criteria.

- joint involvement: 1 large joint (0 points); 2 to 10 large joints (1 point); 1 to 3 small joints with or without large joints (2 points); 4 to 10 small joints with or without large joints (3 points); more than 10 joints with at least 1 small joint (5 points)

- serology: Negative RF and ACPA (0 points); low positive RF or ACPA (2 points); high positive RF or ACPA (3 points)

- acute-phase reactants: Normal CRP and ESR (0 points); abnormal CRP or ESR (1 point)

- duration of symptoms: <6 weeks (0 points); ≥6 weeks (1 point)

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:575-579.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that this was a case of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with rheumatoid nodules. She ordered bilateral hand x-rays and referred the patient to rheumatology. The patient was told that rheumatoid nodules are not harmful and surgery wasn’t recommended. The FP also ordered appropriate blood tests to confirm the impression of RA, which included:

- a rheumatoid factor (RF) test (positive in many connective tissue, neoplastic, and infectious diseases; positive in 70% of RA patients)

- an anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) test (high specificity for RA: Often present before definitive diagnosis can be made; presence predicts arthritis development)

- C-reactive protein (CRP) >0.7 pg/mL, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >30 mm/h

- complete blood count (indicators of RA: normocytic or microcytic anemia, thrombocytosis)

The 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria uses a scoring system to identify patients with RA. A score of ≥6/10 meets the criteria.

- joint involvement: 1 large joint (0 points); 2 to 10 large joints (1 point); 1 to 3 small joints with or without large joints (2 points); 4 to 10 small joints with or without large joints (3 points); more than 10 joints with at least 1 small joint (5 points)

- serology: Negative RF and ACPA (0 points); low positive RF or ACPA (2 points); high positive RF or ACPA (3 points)

- acute-phase reactants: Normal CRP and ESR (0 points); abnormal CRP or ESR (1 point)

- duration of symptoms: <6 weeks (0 points); ≥6 weeks (1 point)

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:575-579.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that this was a case of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with rheumatoid nodules. She ordered bilateral hand x-rays and referred the patient to rheumatology. The patient was told that rheumatoid nodules are not harmful and surgery wasn’t recommended. The FP also ordered appropriate blood tests to confirm the impression of RA, which included:

- a rheumatoid factor (RF) test (positive in many connective tissue, neoplastic, and infectious diseases; positive in 70% of RA patients)

- an anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) test (high specificity for RA: Often present before definitive diagnosis can be made; presence predicts arthritis development)

- C-reactive protein (CRP) >0.7 pg/mL, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >30 mm/h

- complete blood count (indicators of RA: normocytic or microcytic anemia, thrombocytosis)

The 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria uses a scoring system to identify patients with RA. A score of ≥6/10 meets the criteria.

- joint involvement: 1 large joint (0 points); 2 to 10 large joints (1 point); 1 to 3 small joints with or without large joints (2 points); 4 to 10 small joints with or without large joints (3 points); more than 10 joints with at least 1 small joint (5 points)

- serology: Negative RF and ACPA (0 points); low positive RF or ACPA (2 points); high positive RF or ACPA (3 points)

- acute-phase reactants: Normal CRP and ESR (0 points); abnormal CRP or ESR (1 point)

- duration of symptoms: <6 weeks (0 points); ≥6 weeks (1 point)

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:575-579.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash and fever in a 14-month-old girl

A 14-MONTH-OLD GIRL was brought to our medical center with a widespread pruritic eruption and fever that she’d had for 2 days. She had a temperature of 103.2° F, heart rate of 166 beats/min, respiratory rate of 32 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation level of 100%.

On physical examination, the toddler was active, appeared well-nourished, and was not in acute distress. She had ill-defined, polycyclic, urticarial plaques with subtle, purpuric, dusky-appearing changes distributed widely over her face, trunk, and extremities (FIGURE 1A AND 1B). She had no signs of arthritis and did not exhibit an antalgic gait. She was otherwise healthy and had no personal or family history of connective tissue disease.

Lab results showed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (16 mm/hr) and mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count: 109,000/mcL). Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid tests were unremarkable. Nine days earlier, the toddler had been diagnosed with otitis media and prescribed oral amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/d taken in 2 doses.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

Based on the appearance of the plaques and the recent history of amoxicillin use, we diagnosed urticaria multiforme (UM) in this patient. UM is a benign, self-limited, cutaneous, histamine-dependent, hypersensitivity reaction that occurs predominantly among patients ages 4 months to 4 years.1

In UM, the eruption typically occurs one to 3 days after a viral infection or the administration of certain medications.2 A low-grade fever may or may not precede the eruption, and symptoms are usually limited to pruritus. Small urticarial papules and plaques initially appear and then coalesce to form blanching, erythematous, annular, polycyclic wheals.

Unlike “ordinary” acute urticaria, which is characterized by round or oval-shaped erythematous, edematous papules and plaques, UM plaques will have annular, gyrate, serpiginous, polycyclic, and/or target lesions with ecchymotic or dusky-appearing centers.1,3 Individual UM lesions typically last less than 24 hours, while the disease itself can persist for 2 to 12 days, until all lesions heal and the skin returns to normal.2

The diagnosis of UM is a clinical one. When a patient presents with urticarial lesions, ask about the timing of rash onset and the duration of individual lesions. Also ask whether the patient has had a fever, dermatographism, acral edema, or other symptoms, such as arthralgias and myalgias.2

Although a biopsy is typically not performed on this type of lesion, the histology will be the same as that seen in ordinary acute urticaria: dermal edema with some perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.3

Differential Dx includes serum sickness-like reaction, EM

Patients with serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR) will have a more severe clinical presentation than those with UM, characterized by a high-grade fever, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, and arthralgia.2 Also, the time between viral infection/medication administration and onset of eruption is greater in SSLR: 7 to 21 days, as opposed to one to 3 days in UM.1 In addition, the individual lesions of UM only last about a day, whereas the plaques of SSLR can last from a few days to a few weeks.

Patients with erythema multiforme (EM) will complain of pain and burning, rather than itching.2 Both mucosal surfaces and skin may be involved, with typical targetoid lesions often distributed acrally.2 Overlying blistering or necrosis of the epidermis is commonly seen in EM, and like SSLR, the plaques are fixed, rather than transient. Although the plaques of UM, SSLR, and EM can all contain a dusky center, the lesions of SSLR and EM usually resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is typically not seen in UM.1,2

Stop the offending drug, start an antihistamine

Treatment for UM involves discontinuing the offending medication and inhibiting the effects of histamine release. The combination of second-generation antihistamines (eg, cetirizine, fexofenadine, or loratadine) every morning and first-generation antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine) at night for pruritus is the mainstay of treatment.1,2 Acetaminophen can be used for mild fever; however, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided because these medications may worsen the urticarial eruption.4

Our patient had already finished her course of amoxicillin when she first presented with the rash, so we prescribed an oral antihistamine—cetirizine 5 mg BID. Six days after rash onset, when mother and child returned for follow-up, the patient’s lesions had completely resolved. There was no residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which confirmed the diagnosis of UM.

We advised the mother that her daughter was allergic to amoxicillin and told her to avoid it in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Bowen, MD, Dermatology Clinic, 2200 Bergquist Dr, STE 1, JBSA-Lackland, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Mathur AN, Mathes TF. Urticaria mimickers in children. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:467-475.

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part I. Cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:541-555.

4. Sánchez-Borges M, Caballero-Fonseca F, Capriles-Hulett A, et al. Aspirin-exacerbated cutaneous disease (AECD) is a distinct subphenotype of chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:698-701.

A 14-MONTH-OLD GIRL was brought to our medical center with a widespread pruritic eruption and fever that she’d had for 2 days. She had a temperature of 103.2° F, heart rate of 166 beats/min, respiratory rate of 32 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation level of 100%.

On physical examination, the toddler was active, appeared well-nourished, and was not in acute distress. She had ill-defined, polycyclic, urticarial plaques with subtle, purpuric, dusky-appearing changes distributed widely over her face, trunk, and extremities (FIGURE 1A AND 1B). She had no signs of arthritis and did not exhibit an antalgic gait. She was otherwise healthy and had no personal or family history of connective tissue disease.

Lab results showed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (16 mm/hr) and mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count: 109,000/mcL). Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid tests were unremarkable. Nine days earlier, the toddler had been diagnosed with otitis media and prescribed oral amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/d taken in 2 doses.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

Based on the appearance of the plaques and the recent history of amoxicillin use, we diagnosed urticaria multiforme (UM) in this patient. UM is a benign, self-limited, cutaneous, histamine-dependent, hypersensitivity reaction that occurs predominantly among patients ages 4 months to 4 years.1

In UM, the eruption typically occurs one to 3 days after a viral infection or the administration of certain medications.2 A low-grade fever may or may not precede the eruption, and symptoms are usually limited to pruritus. Small urticarial papules and plaques initially appear and then coalesce to form blanching, erythematous, annular, polycyclic wheals.

Unlike “ordinary” acute urticaria, which is characterized by round or oval-shaped erythematous, edematous papules and plaques, UM plaques will have annular, gyrate, serpiginous, polycyclic, and/or target lesions with ecchymotic or dusky-appearing centers.1,3 Individual UM lesions typically last less than 24 hours, while the disease itself can persist for 2 to 12 days, until all lesions heal and the skin returns to normal.2

The diagnosis of UM is a clinical one. When a patient presents with urticarial lesions, ask about the timing of rash onset and the duration of individual lesions. Also ask whether the patient has had a fever, dermatographism, acral edema, or other symptoms, such as arthralgias and myalgias.2

Although a biopsy is typically not performed on this type of lesion, the histology will be the same as that seen in ordinary acute urticaria: dermal edema with some perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.3

Differential Dx includes serum sickness-like reaction, EM

Patients with serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR) will have a more severe clinical presentation than those with UM, characterized by a high-grade fever, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, and arthralgia.2 Also, the time between viral infection/medication administration and onset of eruption is greater in SSLR: 7 to 21 days, as opposed to one to 3 days in UM.1 In addition, the individual lesions of UM only last about a day, whereas the plaques of SSLR can last from a few days to a few weeks.

Patients with erythema multiforme (EM) will complain of pain and burning, rather than itching.2 Both mucosal surfaces and skin may be involved, with typical targetoid lesions often distributed acrally.2 Overlying blistering or necrosis of the epidermis is commonly seen in EM, and like SSLR, the plaques are fixed, rather than transient. Although the plaques of UM, SSLR, and EM can all contain a dusky center, the lesions of SSLR and EM usually resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is typically not seen in UM.1,2

Stop the offending drug, start an antihistamine

Treatment for UM involves discontinuing the offending medication and inhibiting the effects of histamine release. The combination of second-generation antihistamines (eg, cetirizine, fexofenadine, or loratadine) every morning and first-generation antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine) at night for pruritus is the mainstay of treatment.1,2 Acetaminophen can be used for mild fever; however, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided because these medications may worsen the urticarial eruption.4

Our patient had already finished her course of amoxicillin when she first presented with the rash, so we prescribed an oral antihistamine—cetirizine 5 mg BID. Six days after rash onset, when mother and child returned for follow-up, the patient’s lesions had completely resolved. There was no residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which confirmed the diagnosis of UM.

We advised the mother that her daughter was allergic to amoxicillin and told her to avoid it in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Bowen, MD, Dermatology Clinic, 2200 Bergquist Dr, STE 1, JBSA-Lackland, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

A 14-MONTH-OLD GIRL was brought to our medical center with a widespread pruritic eruption and fever that she’d had for 2 days. She had a temperature of 103.2° F, heart rate of 166 beats/min, respiratory rate of 32 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation level of 100%.

On physical examination, the toddler was active, appeared well-nourished, and was not in acute distress. She had ill-defined, polycyclic, urticarial plaques with subtle, purpuric, dusky-appearing changes distributed widely over her face, trunk, and extremities (FIGURE 1A AND 1B). She had no signs of arthritis and did not exhibit an antalgic gait. She was otherwise healthy and had no personal or family history of connective tissue disease.

Lab results showed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (16 mm/hr) and mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count: 109,000/mcL). Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid tests were unremarkable. Nine days earlier, the toddler had been diagnosed with otitis media and prescribed oral amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/d taken in 2 doses.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

Based on the appearance of the plaques and the recent history of amoxicillin use, we diagnosed urticaria multiforme (UM) in this patient. UM is a benign, self-limited, cutaneous, histamine-dependent, hypersensitivity reaction that occurs predominantly among patients ages 4 months to 4 years.1

In UM, the eruption typically occurs one to 3 days after a viral infection or the administration of certain medications.2 A low-grade fever may or may not precede the eruption, and symptoms are usually limited to pruritus. Small urticarial papules and plaques initially appear and then coalesce to form blanching, erythematous, annular, polycyclic wheals.

Unlike “ordinary” acute urticaria, which is characterized by round or oval-shaped erythematous, edematous papules and plaques, UM plaques will have annular, gyrate, serpiginous, polycyclic, and/or target lesions with ecchymotic or dusky-appearing centers.1,3 Individual UM lesions typically last less than 24 hours, while the disease itself can persist for 2 to 12 days, until all lesions heal and the skin returns to normal.2

The diagnosis of UM is a clinical one. When a patient presents with urticarial lesions, ask about the timing of rash onset and the duration of individual lesions. Also ask whether the patient has had a fever, dermatographism, acral edema, or other symptoms, such as arthralgias and myalgias.2

Although a biopsy is typically not performed on this type of lesion, the histology will be the same as that seen in ordinary acute urticaria: dermal edema with some perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.3

Differential Dx includes serum sickness-like reaction, EM

Patients with serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR) will have a more severe clinical presentation than those with UM, characterized by a high-grade fever, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, and arthralgia.2 Also, the time between viral infection/medication administration and onset of eruption is greater in SSLR: 7 to 21 days, as opposed to one to 3 days in UM.1 In addition, the individual lesions of UM only last about a day, whereas the plaques of SSLR can last from a few days to a few weeks.

Patients with erythema multiforme (EM) will complain of pain and burning, rather than itching.2 Both mucosal surfaces and skin may be involved, with typical targetoid lesions often distributed acrally.2 Overlying blistering or necrosis of the epidermis is commonly seen in EM, and like SSLR, the plaques are fixed, rather than transient. Although the plaques of UM, SSLR, and EM can all contain a dusky center, the lesions of SSLR and EM usually resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is typically not seen in UM.1,2

Stop the offending drug, start an antihistamine

Treatment for UM involves discontinuing the offending medication and inhibiting the effects of histamine release. The combination of second-generation antihistamines (eg, cetirizine, fexofenadine, or loratadine) every morning and first-generation antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine) at night for pruritus is the mainstay of treatment.1,2 Acetaminophen can be used for mild fever; however, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided because these medications may worsen the urticarial eruption.4

Our patient had already finished her course of amoxicillin when she first presented with the rash, so we prescribed an oral antihistamine—cetirizine 5 mg BID. Six days after rash onset, when mother and child returned for follow-up, the patient’s lesions had completely resolved. There was no residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which confirmed the diagnosis of UM.

We advised the mother that her daughter was allergic to amoxicillin and told her to avoid it in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Bowen, MD, Dermatology Clinic, 2200 Bergquist Dr, STE 1, JBSA-Lackland, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Mathur AN, Mathes TF. Urticaria mimickers in children. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:467-475.

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part I. Cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:541-555.

4. Sánchez-Borges M, Caballero-Fonseca F, Capriles-Hulett A, et al. Aspirin-exacerbated cutaneous disease (AECD) is a distinct subphenotype of chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:698-701.

1. Mathur AN, Mathes TF. Urticaria mimickers in children. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:467-475.

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part I. Cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:541-555.

4. Sánchez-Borges M, Caballero-Fonseca F, Capriles-Hulett A, et al. Aspirin-exacerbated cutaneous disease (AECD) is a distinct subphenotype of chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:698-701.

Pleuritic chest pain and globus pharyngeus

A 22-year-old woman with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and childhood asthma came to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of a cramping, substernal, pleuritic chest pain she’d had for a week and the feeling of a “lump in her throat” that made it difficult and painful for her to swallow. The patient’s vital signs were normal and her substernal chest pain was reproducible with palpation. An anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray (CXR) was unremarkable.

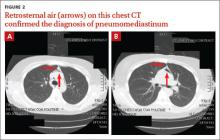

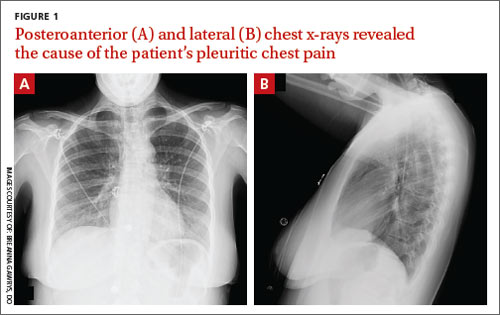

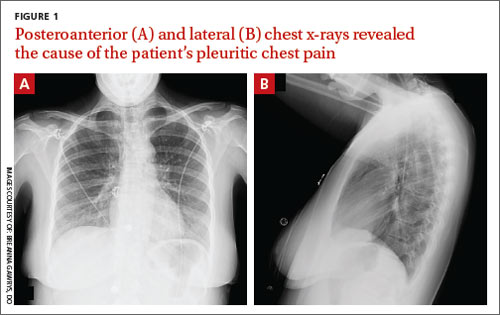

A “GI cocktail” (lidocaine, Mylanta and Donnatal), ketorolac, morphine, and lorazepam were administered in the ED, but did not provide the patient with any relief. She was admitted to the hospital to rule out acute coronary syndrome and was kept NPO overnight. A repeat CXR with posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views was also obtained (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pneumomediastinum

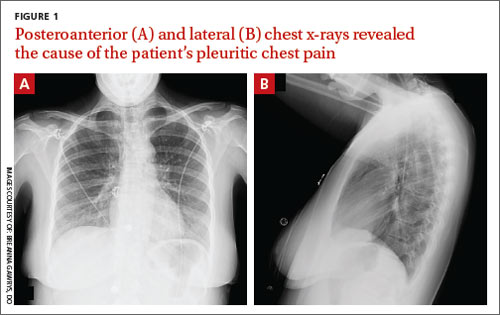

The PA and lateral view CXRs revealed the presence of retrosternal air, suggesting the patient had pneumomediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest also showed retrosternal air (FIGURE 2A AND 2B, arrows) and confirmed this diagnosis. To rule out esophageal perforation, the team ordered Gastrografin and barium swallow studies. The patient was kept NPO until both studies were confirmed to be negative.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by Hamman’s sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Differential diagnosis includes inflammatory conditions

The differential diagnosis for pneumomediastinum includes pericarditis, mediastinitis, Boerhaave syndrome, and acute coronary syndrome.

Pericarditis. In a patient with inflammation of the pericardium, you would hear reduced heart sounds and observe electrocardiogram (EKG) changes (eg, diffuse ST elevation in acute pericarditis). These signs typically would not be present in a patient with pneumomediastinum.1

Mediastinitis. Patients with mediastinitis—inflammation of the mediastinum—are more likely to have hypotension and shock.1

Boerhaave syndrome, or spontaneous esophageal perforation, has a similar presentation to pneumomediastinum but is more likely to be accompanied by hypotension and shock. Additionally, there would be extravasation of the contrast agent during swallow studies.2

Acute coronary syndrome is also part of the differential. However, in ACS, you would see ST changes on the patient’s EKG and elevated cardiac enzymes.1

Lateral x-rays are especially useful in making the diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

For most patients, rest and pain control are key

Because pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home.

If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation. If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3 Gastrografin swallow studies are the preferred initial study.3 A barium swallow study is more sensitive, but has a higher risk of causing pneumomediastinitis if an esophageal perforation is present.2

If the swallow study reveals a perforation, surgical decompression and antibiotics may be necessary.1,4,5

Our patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in pneumomediastinum. Once our patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged home after a 3-day hospitalization with close follow-up. One week later, she had no further complaints and her pain had almost entirely resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Breanna Gawrys, DO, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039–2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057.

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334.

4. Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110-1114.

5. Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:67-75.

A 22-year-old woman with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and childhood asthma came to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of a cramping, substernal, pleuritic chest pain she’d had for a week and the feeling of a “lump in her throat” that made it difficult and painful for her to swallow. The patient’s vital signs were normal and her substernal chest pain was reproducible with palpation. An anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray (CXR) was unremarkable.

A “GI cocktail” (lidocaine, Mylanta and Donnatal), ketorolac, morphine, and lorazepam were administered in the ED, but did not provide the patient with any relief. She was admitted to the hospital to rule out acute coronary syndrome and was kept NPO overnight. A repeat CXR with posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views was also obtained (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pneumomediastinum

The PA and lateral view CXRs revealed the presence of retrosternal air, suggesting the patient had pneumomediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest also showed retrosternal air (FIGURE 2A AND 2B, arrows) and confirmed this diagnosis. To rule out esophageal perforation, the team ordered Gastrografin and barium swallow studies. The patient was kept NPO until both studies were confirmed to be negative.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by Hamman’s sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Differential diagnosis includes inflammatory conditions

The differential diagnosis for pneumomediastinum includes pericarditis, mediastinitis, Boerhaave syndrome, and acute coronary syndrome.

Pericarditis. In a patient with inflammation of the pericardium, you would hear reduced heart sounds and observe electrocardiogram (EKG) changes (eg, diffuse ST elevation in acute pericarditis). These signs typically would not be present in a patient with pneumomediastinum.1

Mediastinitis. Patients with mediastinitis—inflammation of the mediastinum—are more likely to have hypotension and shock.1

Boerhaave syndrome, or spontaneous esophageal perforation, has a similar presentation to pneumomediastinum but is more likely to be accompanied by hypotension and shock. Additionally, there would be extravasation of the contrast agent during swallow studies.2

Acute coronary syndrome is also part of the differential. However, in ACS, you would see ST changes on the patient’s EKG and elevated cardiac enzymes.1

Lateral x-rays are especially useful in making the diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

For most patients, rest and pain control are key

Because pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home.

If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation. If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3 Gastrografin swallow studies are the preferred initial study.3 A barium swallow study is more sensitive, but has a higher risk of causing pneumomediastinitis if an esophageal perforation is present.2

If the swallow study reveals a perforation, surgical decompression and antibiotics may be necessary.1,4,5

Our patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in pneumomediastinum. Once our patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged home after a 3-day hospitalization with close follow-up. One week later, she had no further complaints and her pain had almost entirely resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Breanna Gawrys, DO, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

A 22-year-old woman with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and childhood asthma came to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of a cramping, substernal, pleuritic chest pain she’d had for a week and the feeling of a “lump in her throat” that made it difficult and painful for her to swallow. The patient’s vital signs were normal and her substernal chest pain was reproducible with palpation. An anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray (CXR) was unremarkable.

A “GI cocktail” (lidocaine, Mylanta and Donnatal), ketorolac, morphine, and lorazepam were administered in the ED, but did not provide the patient with any relief. She was admitted to the hospital to rule out acute coronary syndrome and was kept NPO overnight. A repeat CXR with posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views was also obtained (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pneumomediastinum

The PA and lateral view CXRs revealed the presence of retrosternal air, suggesting the patient had pneumomediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest also showed retrosternal air (FIGURE 2A AND 2B, arrows) and confirmed this diagnosis. To rule out esophageal perforation, the team ordered Gastrografin and barium swallow studies. The patient was kept NPO until both studies were confirmed to be negative.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by Hamman’s sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Differential diagnosis includes inflammatory conditions

The differential diagnosis for pneumomediastinum includes pericarditis, mediastinitis, Boerhaave syndrome, and acute coronary syndrome.

Pericarditis. In a patient with inflammation of the pericardium, you would hear reduced heart sounds and observe electrocardiogram (EKG) changes (eg, diffuse ST elevation in acute pericarditis). These signs typically would not be present in a patient with pneumomediastinum.1

Mediastinitis. Patients with mediastinitis—inflammation of the mediastinum—are more likely to have hypotension and shock.1

Boerhaave syndrome, or spontaneous esophageal perforation, has a similar presentation to pneumomediastinum but is more likely to be accompanied by hypotension and shock. Additionally, there would be extravasation of the contrast agent during swallow studies.2

Acute coronary syndrome is also part of the differential. However, in ACS, you would see ST changes on the patient’s EKG and elevated cardiac enzymes.1

Lateral x-rays are especially useful in making the diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

For most patients, rest and pain control are key

Because pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home.

If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation. If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3 Gastrografin swallow studies are the preferred initial study.3 A barium swallow study is more sensitive, but has a higher risk of causing pneumomediastinitis if an esophageal perforation is present.2

If the swallow study reveals a perforation, surgical decompression and antibiotics may be necessary.1,4,5

Our patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in pneumomediastinum. Once our patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged home after a 3-day hospitalization with close follow-up. One week later, she had no further complaints and her pain had almost entirely resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE

Breanna Gawrys, DO, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039–2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057.

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334.

4. Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110-1114.

5. Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:67-75.

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039–2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057.

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334.

4. Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110-1114.

5. Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:67-75.

Alopecia with pustules

The patient was given a diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans (FD), a highly inflammatory form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. The term scarring alopecia refers to the fact that the follicular epithelium has been replaced by connective tissue, ultimately resulting in permanent hair loss. Affected areas commonly include the vertex and occipital scalp. Common symptoms include pain, itching, burning, and occasionally spontaneous bleeding or discharge of purulent material.

FD generally occurs in young and middle-aged African Americans with a slight predominance in males, but can occur in any ethnic group at any age. The etiology is not fully understood; however, scalp colonization with Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as a contributing factor. Some reports suggest that patients may have an altered host immune response and/or genetic predisposition for the condition.

Two scalp biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. One biopsy should be processed for standard horizontal sectioning, but the second biopsy should be bisected vertically, with half sent for histologic examination and the other half for tissue culture (fungal and bacterial).

Primary treatment is aimed at eliminating S aureus colonization, often with oral antibiotic therapy. Adjunctive topical and intralesional corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation and provide relief from itching, burning, and pain.

In this case, the patient was prescribed oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, as well as clobetasol 0.05% topical solution, to be applied to the affected area in the morning and evening. The patient’s symptoms improved within 2 months. The plan was to wean him off doxycycline over a 6-month period and then transition him to topical clindamycin solution twice daily.

Adapted from: Moss TA, Beachkofsky TM, Almquist SF, et al. Alopecia with perifollicular papules and pustules. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:95-98.

The patient was given a diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans (FD), a highly inflammatory form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. The term scarring alopecia refers to the fact that the follicular epithelium has been replaced by connective tissue, ultimately resulting in permanent hair loss. Affected areas commonly include the vertex and occipital scalp. Common symptoms include pain, itching, burning, and occasionally spontaneous bleeding or discharge of purulent material.

FD generally occurs in young and middle-aged African Americans with a slight predominance in males, but can occur in any ethnic group at any age. The etiology is not fully understood; however, scalp colonization with Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as a contributing factor. Some reports suggest that patients may have an altered host immune response and/or genetic predisposition for the condition.

Two scalp biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. One biopsy should be processed for standard horizontal sectioning, but the second biopsy should be bisected vertically, with half sent for histologic examination and the other half for tissue culture (fungal and bacterial).

Primary treatment is aimed at eliminating S aureus colonization, often with oral antibiotic therapy. Adjunctive topical and intralesional corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation and provide relief from itching, burning, and pain.

In this case, the patient was prescribed oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, as well as clobetasol 0.05% topical solution, to be applied to the affected area in the morning and evening. The patient’s symptoms improved within 2 months. The plan was to wean him off doxycycline over a 6-month period and then transition him to topical clindamycin solution twice daily.

Adapted from: Moss TA, Beachkofsky TM, Almquist SF, et al. Alopecia with perifollicular papules and pustules. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:95-98.

The patient was given a diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans (FD), a highly inflammatory form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. The term scarring alopecia refers to the fact that the follicular epithelium has been replaced by connective tissue, ultimately resulting in permanent hair loss. Affected areas commonly include the vertex and occipital scalp. Common symptoms include pain, itching, burning, and occasionally spontaneous bleeding or discharge of purulent material.

FD generally occurs in young and middle-aged African Americans with a slight predominance in males, but can occur in any ethnic group at any age. The etiology is not fully understood; however, scalp colonization with Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as a contributing factor. Some reports suggest that patients may have an altered host immune response and/or genetic predisposition for the condition.

Two scalp biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. One biopsy should be processed for standard horizontal sectioning, but the second biopsy should be bisected vertically, with half sent for histologic examination and the other half for tissue culture (fungal and bacterial).

Primary treatment is aimed at eliminating S aureus colonization, often with oral antibiotic therapy. Adjunctive topical and intralesional corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation and provide relief from itching, burning, and pain.

In this case, the patient was prescribed oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, as well as clobetasol 0.05% topical solution, to be applied to the affected area in the morning and evening. The patient’s symptoms improved within 2 months. The plan was to wean him off doxycycline over a 6-month period and then transition him to topical clindamycin solution twice daily.

Adapted from: Moss TA, Beachkofsky TM, Almquist SF, et al. Alopecia with perifollicular papules and pustules. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:95-98.

Elbow swelling

The FP recognized that this was a case of bilateral olecranon bursitis, and that the patient’s left arm was most affected.