User login

Number of malpractice payments down 28% since 2004

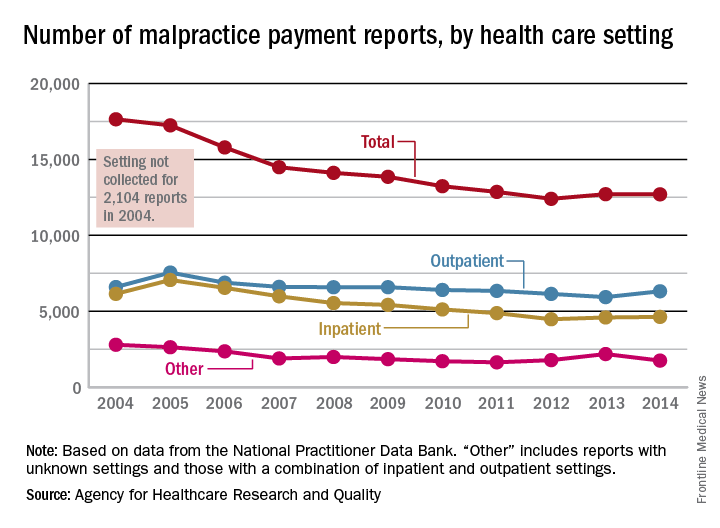

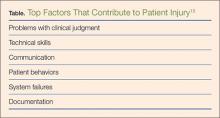

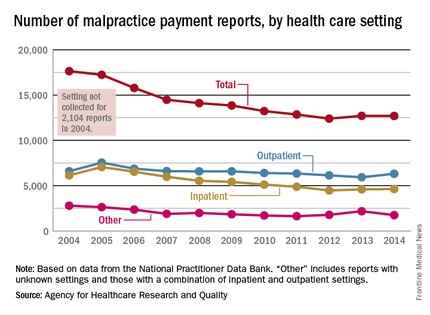

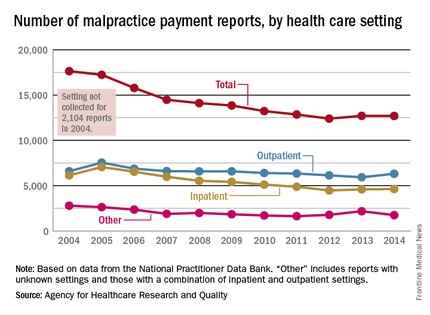

The annual number of medical malpractice payment reports fell 28% from 2004 to 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The total number of medical malpractice payment reports (MMPRs) for 2014 was 12,699, a decrease of 28% since 2004, when there were 17,641. The total had gone down every year until a slight increase in 2013, but the number held steady in 2014, the AHRQ reported in the Chartbook on Patient Safety.

Since 2004, MMPRs related to inpatient settings have been dropping slightly faster than outpatient-related MMPRs, with the exception, again, of 2013, when the number of inpatient MMPRs went up while the outpatient total dropped. Both types went up in 2014, but the category of “other” – reports related to unknown settings and those from a combination of the two – dropped in 2014 to keep the overall number from going up again, data from the National Practitioner Data Bank show.

Looking at the types of allegation leading to MMPRs, treatment was highest, accounting for 27.4% of the total from 2004 to 2014, with diagnosis right behind at 27.1%, followed by surgery at 23.5% and obstetrics at 6.7%. Medication-related cases represented 5.3% of all MMPRs over that period, the AHRQ noted.

The annual number of medical malpractice payment reports fell 28% from 2004 to 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The total number of medical malpractice payment reports (MMPRs) for 2014 was 12,699, a decrease of 28% since 2004, when there were 17,641. The total had gone down every year until a slight increase in 2013, but the number held steady in 2014, the AHRQ reported in the Chartbook on Patient Safety.

Since 2004, MMPRs related to inpatient settings have been dropping slightly faster than outpatient-related MMPRs, with the exception, again, of 2013, when the number of inpatient MMPRs went up while the outpatient total dropped. Both types went up in 2014, but the category of “other” – reports related to unknown settings and those from a combination of the two – dropped in 2014 to keep the overall number from going up again, data from the National Practitioner Data Bank show.

Looking at the types of allegation leading to MMPRs, treatment was highest, accounting for 27.4% of the total from 2004 to 2014, with diagnosis right behind at 27.1%, followed by surgery at 23.5% and obstetrics at 6.7%. Medication-related cases represented 5.3% of all MMPRs over that period, the AHRQ noted.

The annual number of medical malpractice payment reports fell 28% from 2004 to 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The total number of medical malpractice payment reports (MMPRs) for 2014 was 12,699, a decrease of 28% since 2004, when there were 17,641. The total had gone down every year until a slight increase in 2013, but the number held steady in 2014, the AHRQ reported in the Chartbook on Patient Safety.

Since 2004, MMPRs related to inpatient settings have been dropping slightly faster than outpatient-related MMPRs, with the exception, again, of 2013, when the number of inpatient MMPRs went up while the outpatient total dropped. Both types went up in 2014, but the category of “other” – reports related to unknown settings and those from a combination of the two – dropped in 2014 to keep the overall number from going up again, data from the National Practitioner Data Bank show.

Looking at the types of allegation leading to MMPRs, treatment was highest, accounting for 27.4% of the total from 2004 to 2014, with diagnosis right behind at 27.1%, followed by surgery at 23.5% and obstetrics at 6.7%. Medication-related cases represented 5.3% of all MMPRs over that period, the AHRQ noted.

Hospital computerized physician order entry systems often miss prescribing errors

Medical errors are estimated to be the third-highest cause of death in the country. Experts and patient safety advocates are trying to change that. But at least one of the tools that has been considered a fix isn’t yet working as well as it should, suggests a report released April 7.

That’s according to the Leapfrog Group, a nonprofit organization known for rating hospitals on patient safety. Leapfrog conducted a voluntary survey of almost 1,800 hospitals to determine how many use computerized-physician-order-entry systems to make sure patients are prescribed and receive the correct drugs, and that medications won’t cause harm.

The takeaway? While a vast majority of hospitals surveyed had some kind of computer-based medication system in place, the systems still fall short in catching possible problems.

“These systems are not always catching the potential errors inherent in prescribing,” said Erica Mobley, Leapfrog’s director of development and communications.

Almost 40 percent of potentially harmful drug orders weren’t flagged as dangerous by the systems, Leapfrog found. These included medication orders for the wrong condition or in the wrong dose based on things like a patient’s size, other illnesses or likely drug interactions.

Meanwhile, systems missed about 13 percent of errors that could have killed patients.

According to 2015 figures from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, about 1 of every 20 patients in hospitals suffers harm because of medications. Of those, the agency estimates, half are avoidable.

Meanwhile, in a push to improve patient safety and health care quality, the federal government has been encouraging hospitals to adopt electronic health records – particularly with medication ordering systems – thanks to parts of the 2009 stimulus package and 2010 health reform. But there has been pushback from many doctors and advocates, who say design issues can make the software difficult to use or even counterproductive.

The Leapfrog survey – which is not peer-reviewed – asked participating hospitals to use “dummy patients” to test their system, Mobley said. Participants would put in information for fake patients and submit a set of medication orders to see which ones got flagged. Mistakes might include orders prescribing an adult dosage to a child, for instance.

The results are “alarming,” said Helen Haskell, a prominent patient safety advocate. “It shows that the technology is not as foolproof as we would like to think.”

But it’s difficult to know how many of those missed errors result in actual harm, Mobley acknowledged. Ordering the wrong medication can be inconvenient or problematic. But it isn’t always dangerous. And, for those that are, hospitals may have other safeguards in place to catch mistakes before they actually hurt patients. “It really does vary significantly by hospital,” she said.

The survey, Mobley suggested, underscores the need for hospitals and patients to be vigilant when it comes to overseeing their medications. For hospitals, that means instituting “checks and balances” – system-wide initiatives like requiring manual reviews of a patient’s drugs, on top of the computer checks.

And hospitals are increasingly taking such steps to make medication errors less common, said Jesse Pines, who directs the Office for Clinical Practice Innovation at George Washington University, Washington, and is a professor of emergency medicine. Technology is also improving, so medication ordering systems should get better, he added.

“Technology exists to help with detecting medical errors at the point of when you’re entering drug orders in the hospital or health care settings,” he said. “But they’re not perfect. They still need a lot of work.”

Patients, meanwhile, should make sure to have someone with them when they go into the hospital, who can check out what drugs they’re being prescribed, Mobley said.

“It’s absolutely critical that whenever the patient or somebody with them notices that this maze [of medications] looks slightly different from what’s been done in the past, they ask about that,” she said.

But even with that vigilance, Haskell said, “your knowledge is not infinite – so there’s a limit to what patients can do.”

Hospitals can try to customize their medication ordering systems to do things like identify frequently ordered drugs or better match the patients they’re likely to treat.

How well they do at adapting the software can also play a role in how good hospitals are at catching and preventing mistakes when it comes to ordering medications, said Raj Ratwani, who researches health care safety and is the scientific director for MedStar Health’s National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare in Washington. To that end, hospitals and safety experts should figure out what are the best practices when it comes to customizing tools like medication ordering software.

A number of Leapfrog’s surveys have come under scrutiny from some hospitals, who question their methodology and metrics. Here, Mobley said, the survey may inflate the number of hospitals with a computer-based medication ordering system. But when it comes to how effective the systems are, the findings are unsurprising, both Haskell and Ratwani said.

“What these findings indicate – and what many other researchers have shown – is that computerized physician order entry is effective at reducing adverse drug events,” Ratwani said. “What we also know…is these electronic health record systems are complex.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

On Twitter @Shefalil

Medical errors are estimated to be the third-highest cause of death in the country. Experts and patient safety advocates are trying to change that. But at least one of the tools that has been considered a fix isn’t yet working as well as it should, suggests a report released April 7.

That’s according to the Leapfrog Group, a nonprofit organization known for rating hospitals on patient safety. Leapfrog conducted a voluntary survey of almost 1,800 hospitals to determine how many use computerized-physician-order-entry systems to make sure patients are prescribed and receive the correct drugs, and that medications won’t cause harm.

The takeaway? While a vast majority of hospitals surveyed had some kind of computer-based medication system in place, the systems still fall short in catching possible problems.

“These systems are not always catching the potential errors inherent in prescribing,” said Erica Mobley, Leapfrog’s director of development and communications.

Almost 40 percent of potentially harmful drug orders weren’t flagged as dangerous by the systems, Leapfrog found. These included medication orders for the wrong condition or in the wrong dose based on things like a patient’s size, other illnesses or likely drug interactions.

Meanwhile, systems missed about 13 percent of errors that could have killed patients.

According to 2015 figures from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, about 1 of every 20 patients in hospitals suffers harm because of medications. Of those, the agency estimates, half are avoidable.

Meanwhile, in a push to improve patient safety and health care quality, the federal government has been encouraging hospitals to adopt electronic health records – particularly with medication ordering systems – thanks to parts of the 2009 stimulus package and 2010 health reform. But there has been pushback from many doctors and advocates, who say design issues can make the software difficult to use or even counterproductive.

The Leapfrog survey – which is not peer-reviewed – asked participating hospitals to use “dummy patients” to test their system, Mobley said. Participants would put in information for fake patients and submit a set of medication orders to see which ones got flagged. Mistakes might include orders prescribing an adult dosage to a child, for instance.

The results are “alarming,” said Helen Haskell, a prominent patient safety advocate. “It shows that the technology is not as foolproof as we would like to think.”

But it’s difficult to know how many of those missed errors result in actual harm, Mobley acknowledged. Ordering the wrong medication can be inconvenient or problematic. But it isn’t always dangerous. And, for those that are, hospitals may have other safeguards in place to catch mistakes before they actually hurt patients. “It really does vary significantly by hospital,” she said.

The survey, Mobley suggested, underscores the need for hospitals and patients to be vigilant when it comes to overseeing their medications. For hospitals, that means instituting “checks and balances” – system-wide initiatives like requiring manual reviews of a patient’s drugs, on top of the computer checks.

And hospitals are increasingly taking such steps to make medication errors less common, said Jesse Pines, who directs the Office for Clinical Practice Innovation at George Washington University, Washington, and is a professor of emergency medicine. Technology is also improving, so medication ordering systems should get better, he added.

“Technology exists to help with detecting medical errors at the point of when you’re entering drug orders in the hospital or health care settings,” he said. “But they’re not perfect. They still need a lot of work.”

Patients, meanwhile, should make sure to have someone with them when they go into the hospital, who can check out what drugs they’re being prescribed, Mobley said.

“It’s absolutely critical that whenever the patient or somebody with them notices that this maze [of medications] looks slightly different from what’s been done in the past, they ask about that,” she said.

But even with that vigilance, Haskell said, “your knowledge is not infinite – so there’s a limit to what patients can do.”

Hospitals can try to customize their medication ordering systems to do things like identify frequently ordered drugs or better match the patients they’re likely to treat.

How well they do at adapting the software can also play a role in how good hospitals are at catching and preventing mistakes when it comes to ordering medications, said Raj Ratwani, who researches health care safety and is the scientific director for MedStar Health’s National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare in Washington. To that end, hospitals and safety experts should figure out what are the best practices when it comes to customizing tools like medication ordering software.

A number of Leapfrog’s surveys have come under scrutiny from some hospitals, who question their methodology and metrics. Here, Mobley said, the survey may inflate the number of hospitals with a computer-based medication ordering system. But when it comes to how effective the systems are, the findings are unsurprising, both Haskell and Ratwani said.

“What these findings indicate – and what many other researchers have shown – is that computerized physician order entry is effective at reducing adverse drug events,” Ratwani said. “What we also know…is these electronic health record systems are complex.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

On Twitter @Shefalil

Medical errors are estimated to be the third-highest cause of death in the country. Experts and patient safety advocates are trying to change that. But at least one of the tools that has been considered a fix isn’t yet working as well as it should, suggests a report released April 7.

That’s according to the Leapfrog Group, a nonprofit organization known for rating hospitals on patient safety. Leapfrog conducted a voluntary survey of almost 1,800 hospitals to determine how many use computerized-physician-order-entry systems to make sure patients are prescribed and receive the correct drugs, and that medications won’t cause harm.

The takeaway? While a vast majority of hospitals surveyed had some kind of computer-based medication system in place, the systems still fall short in catching possible problems.

“These systems are not always catching the potential errors inherent in prescribing,” said Erica Mobley, Leapfrog’s director of development and communications.

Almost 40 percent of potentially harmful drug orders weren’t flagged as dangerous by the systems, Leapfrog found. These included medication orders for the wrong condition or in the wrong dose based on things like a patient’s size, other illnesses or likely drug interactions.

Meanwhile, systems missed about 13 percent of errors that could have killed patients.

According to 2015 figures from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, about 1 of every 20 patients in hospitals suffers harm because of medications. Of those, the agency estimates, half are avoidable.

Meanwhile, in a push to improve patient safety and health care quality, the federal government has been encouraging hospitals to adopt electronic health records – particularly with medication ordering systems – thanks to parts of the 2009 stimulus package and 2010 health reform. But there has been pushback from many doctors and advocates, who say design issues can make the software difficult to use or even counterproductive.

The Leapfrog survey – which is not peer-reviewed – asked participating hospitals to use “dummy patients” to test their system, Mobley said. Participants would put in information for fake patients and submit a set of medication orders to see which ones got flagged. Mistakes might include orders prescribing an adult dosage to a child, for instance.

The results are “alarming,” said Helen Haskell, a prominent patient safety advocate. “It shows that the technology is not as foolproof as we would like to think.”

But it’s difficult to know how many of those missed errors result in actual harm, Mobley acknowledged. Ordering the wrong medication can be inconvenient or problematic. But it isn’t always dangerous. And, for those that are, hospitals may have other safeguards in place to catch mistakes before they actually hurt patients. “It really does vary significantly by hospital,” she said.

The survey, Mobley suggested, underscores the need for hospitals and patients to be vigilant when it comes to overseeing their medications. For hospitals, that means instituting “checks and balances” – system-wide initiatives like requiring manual reviews of a patient’s drugs, on top of the computer checks.

And hospitals are increasingly taking such steps to make medication errors less common, said Jesse Pines, who directs the Office for Clinical Practice Innovation at George Washington University, Washington, and is a professor of emergency medicine. Technology is also improving, so medication ordering systems should get better, he added.

“Technology exists to help with detecting medical errors at the point of when you’re entering drug orders in the hospital or health care settings,” he said. “But they’re not perfect. They still need a lot of work.”

Patients, meanwhile, should make sure to have someone with them when they go into the hospital, who can check out what drugs they’re being prescribed, Mobley said.

“It’s absolutely critical that whenever the patient or somebody with them notices that this maze [of medications] looks slightly different from what’s been done in the past, they ask about that,” she said.

But even with that vigilance, Haskell said, “your knowledge is not infinite – so there’s a limit to what patients can do.”

Hospitals can try to customize their medication ordering systems to do things like identify frequently ordered drugs or better match the patients they’re likely to treat.

How well they do at adapting the software can also play a role in how good hospitals are at catching and preventing mistakes when it comes to ordering medications, said Raj Ratwani, who researches health care safety and is the scientific director for MedStar Health’s National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare in Washington. To that end, hospitals and safety experts should figure out what are the best practices when it comes to customizing tools like medication ordering software.

A number of Leapfrog’s surveys have come under scrutiny from some hospitals, who question their methodology and metrics. Here, Mobley said, the survey may inflate the number of hospitals with a computer-based medication ordering system. But when it comes to how effective the systems are, the findings are unsurprising, both Haskell and Ratwani said.

“What these findings indicate – and what many other researchers have shown – is that computerized physician order entry is effective at reducing adverse drug events,” Ratwani said. “What we also know…is these electronic health record systems are complex.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

On Twitter @Shefalil

SURVEY: Telemedicine high priority, but reimbursement remains challenging

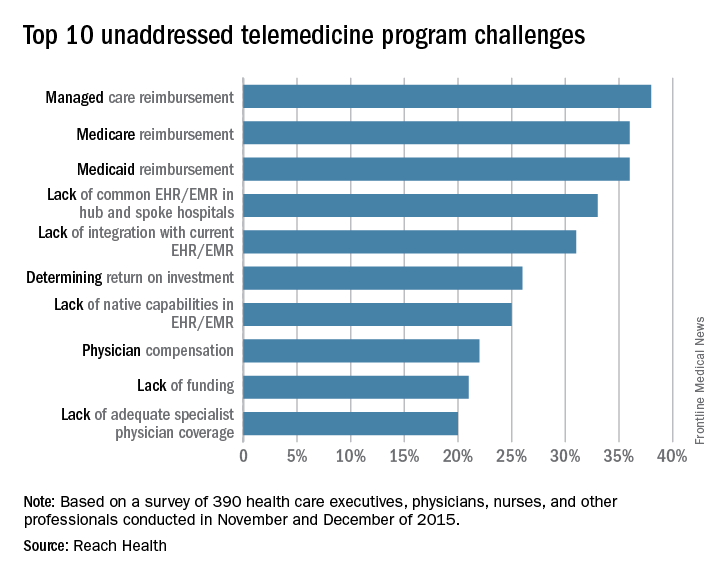

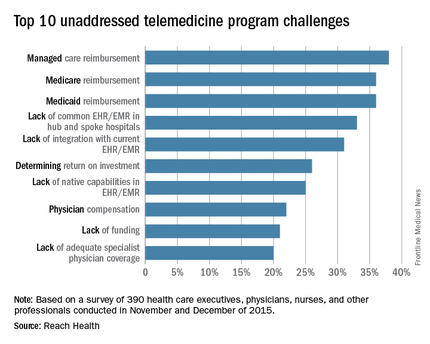

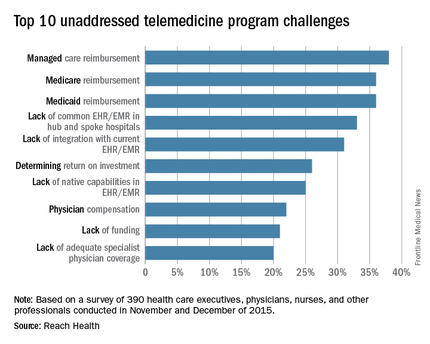

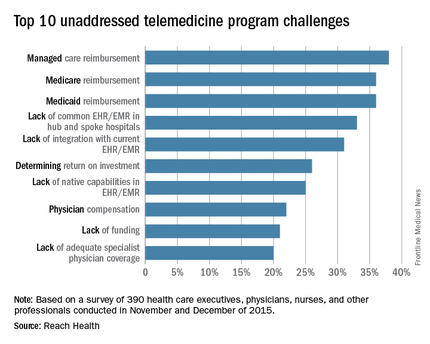

Nearly two-thirds of health care providers rank telemedicine as a top priority in 2016, a 10% increase from last year, according to a survey.

Telemedicine software company REACH Health surveyed 390 U.S. health care professionals between November 2015 and December 2015, including physicians, nurses, and health care executives. Participants answered questions related to their objectives, challenges, telemedicine program models, and management structures, among other inquiries.

Of those polled, 96% of respondents said improving patient outcome was a top objective in developing telemedicine programs, according to the survey. Increasing patient convenience (87%) and improving patient engagement (86%) also rated highly. Other objectives included providing remote and rural patients with access to specialists (83%) and improving leverage of limited physician resources (81%). Percentages do not equal 100% because respondents could choose more than one objective.

The maturity of telemedicine programs varied widely depending on care setting. In general, settings requiring highly specialized treatment had more mature telemedicine programs than those requiring more generalized treatment. Stroke, neurology, and psychiatric/behavioral health settings had the most mature telemedicine programs, according to the survey.

Reimbursement ranked as the top barrier to telemedicine. Respondents rated private plan payment as the No. 1 challenge (38%), followed by Medicare reimbursement (36%) and Medicaid reimbursement (36%). Electronic health record incapabilities and liability risks also ranked as primary challenges.

“Telemedicine reimbursement poses the primary obstacle to success, but EMR-related challenges are persistent and widely noted in the survey,” Steve McGraw, president and CEO of REACH Health said in a statement. “There is clearly a high demand in the industry for EMR integration, specifically the two-way flow of individual data elements between telemedicine platforms and EMR systems.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Nearly two-thirds of health care providers rank telemedicine as a top priority in 2016, a 10% increase from last year, according to a survey.

Telemedicine software company REACH Health surveyed 390 U.S. health care professionals between November 2015 and December 2015, including physicians, nurses, and health care executives. Participants answered questions related to their objectives, challenges, telemedicine program models, and management structures, among other inquiries.

Of those polled, 96% of respondents said improving patient outcome was a top objective in developing telemedicine programs, according to the survey. Increasing patient convenience (87%) and improving patient engagement (86%) also rated highly. Other objectives included providing remote and rural patients with access to specialists (83%) and improving leverage of limited physician resources (81%). Percentages do not equal 100% because respondents could choose more than one objective.

The maturity of telemedicine programs varied widely depending on care setting. In general, settings requiring highly specialized treatment had more mature telemedicine programs than those requiring more generalized treatment. Stroke, neurology, and psychiatric/behavioral health settings had the most mature telemedicine programs, according to the survey.

Reimbursement ranked as the top barrier to telemedicine. Respondents rated private plan payment as the No. 1 challenge (38%), followed by Medicare reimbursement (36%) and Medicaid reimbursement (36%). Electronic health record incapabilities and liability risks also ranked as primary challenges.

“Telemedicine reimbursement poses the primary obstacle to success, but EMR-related challenges are persistent and widely noted in the survey,” Steve McGraw, president and CEO of REACH Health said in a statement. “There is clearly a high demand in the industry for EMR integration, specifically the two-way flow of individual data elements between telemedicine platforms and EMR systems.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Nearly two-thirds of health care providers rank telemedicine as a top priority in 2016, a 10% increase from last year, according to a survey.

Telemedicine software company REACH Health surveyed 390 U.S. health care professionals between November 2015 and December 2015, including physicians, nurses, and health care executives. Participants answered questions related to their objectives, challenges, telemedicine program models, and management structures, among other inquiries.

Of those polled, 96% of respondents said improving patient outcome was a top objective in developing telemedicine programs, according to the survey. Increasing patient convenience (87%) and improving patient engagement (86%) also rated highly. Other objectives included providing remote and rural patients with access to specialists (83%) and improving leverage of limited physician resources (81%). Percentages do not equal 100% because respondents could choose more than one objective.

The maturity of telemedicine programs varied widely depending on care setting. In general, settings requiring highly specialized treatment had more mature telemedicine programs than those requiring more generalized treatment. Stroke, neurology, and psychiatric/behavioral health settings had the most mature telemedicine programs, according to the survey.

Reimbursement ranked as the top barrier to telemedicine. Respondents rated private plan payment as the No. 1 challenge (38%), followed by Medicare reimbursement (36%) and Medicaid reimbursement (36%). Electronic health record incapabilities and liability risks also ranked as primary challenges.

“Telemedicine reimbursement poses the primary obstacle to success, but EMR-related challenges are persistent and widely noted in the survey,” Steve McGraw, president and CEO of REACH Health said in a statement. “There is clearly a high demand in the industry for EMR integration, specifically the two-way flow of individual data elements between telemedicine platforms and EMR systems.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Administrators Share Strategies for High-Performing Hospitalist Groups at HM16

In November, Barbara Weisenbach took a new job as practice manager for the hospitalist group at Northwest Hospital in Seattle. She’s an experienced administrator but as for hospital medicine, not so much. And she is the group’s first full-fledged practice manager—as in, she’s not a physician taking on admin responsibilities and seeing a partial census.

She’s doing a lot of reshaping and a lot of learning, she said, standing outside Room 10 of the San Diego Convention Center, where a daylong pre-course on practice management was being held at SHM’s annual meeting.

“There have been a lot of business things that have been overlooked and not addressed ever before,” she said.

The pre-course, “The Highly Effective Hospital Medicine Group: Using SHM’s Key Characteristics to Drive Performance,” was led by John Nelson, MD, MHM, and Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, and offered one useful lesson after another, Weisenbach said.

“One of the most practical portions of the session this morning was about dashboards, which is something I’m currently working on and could definitely use some insight,” Weisenbach said, adding that a list of metrics a dashboard should include and general guidelines on effective dashboards were things she’ll find useful in her own implementation.

The pre-course expanded on the key principles and traits for effective groups, including effective leadership, engaged hospitalists, adequate resources, alignment with the hospital, and care coordination across settings.

HM16 also included two and a half days of practice management sessions. Plus, management themes were woven through workshops and sprinkled into other sessions.

In one session on handling change, presenters used a surfing analogy: Like a surfer’s intensity just before riding a wave, a laser focus is called for when the moment arrives to execute change.

“Get ready for the ride,” said Steve Behnke, MD, president of Columbus, Ohio–based MedOne Hospital Physicians.

He discussed details of introducing the electronic health record system Epic at their group. There was 18 months of planning involving the practice’s whole operational team, then a doubling of the staffing ratios when the system went live, followed by catered lunches to gather feedback and identify problems.

Presenters emphasized the idea of agility in responding to obstacles and realizing that change affects everyone. Successful change, they said, involves seeing the process from all perspectives and leaders should expect resistance.

“Court them. Listen to them. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve done that,” said Dea Robinson, MA, MedOne’s vice president of operations. “Just listening and giving a platform.”

Back at the pre-course, Dr. Nelson, a hospital medicine consultant, talked about the importance of effective leadership.

“An effective group leader is a really key element of a successful group,” said The Hospitalist’s resident practice management columnist. “I’ve worked on-site with many hundreds of hospitalist groups around the country. There’s pretty good correlation between the effectiveness of the leader and the success of the group overall. But a good leader alone is not enough.”

He added that there are too “few leaders to go around.”

A good leader is an active one, he said, adding with funny-because-it’s-true humor that a lot of leaders say their main job is to make the schedule. Good leaders, he said, need to be focused on making the group high-functioning, should be available for administrative work even when not on a clinical shift, and must be able to delegate.

Another critical ingredient for a successful group, he said, is having engaged frontline hospitalists. Reviews need to be meaningful, and meetings should be held regularly with attendance essentially mandatory. Meetings, he said, might need a “tune-up,” with actual voting, written agendas, minutes taken, and group problem-solving above one-way information.

Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, on care coordination, said the relationship with primary care physicians is crucial though difficult.

“I think we have to go out of our way to build relationships,” he said. “And we don’t have occasion to see them, so we need to figure out a way to get to know our community.”

He suggested:

- Having dedicated transcriptionists for hospitalists,

- Tracking the rate at which discharge summaries are generated within 24 hours,

- Making sure PCPs know how to reach hospitalists, and

- Scheduling events—perhaps an annual event—for meeting PCPs and skill-nursing facility healthcare professionals.

It was clear that, in a field whose dimensions seem to be changing all the time, practice management remained a top interest at HM16. Robert Clothier, RN, a practice manager for the hospitalist group at ThedaCare in Wisconsin, recently switched from managing a cardiology clinic. He said there were huge differences in hospital medicine.

“The profession is growing so fast, and really nobody knows where the end is,” he said. “I can’t even think of anything where you could say, ‘Well, no, they’ll never do that.’ It’s endless. That’s going to be hardest thing. People are going to be pulling on us, and leadership from the hospital is going to be saying, ‘You guys need to do this.’

“So how can I control what we pick, and how can I make sure that we have the resources to do it?” TH

In November, Barbara Weisenbach took a new job as practice manager for the hospitalist group at Northwest Hospital in Seattle. She’s an experienced administrator but as for hospital medicine, not so much. And she is the group’s first full-fledged practice manager—as in, she’s not a physician taking on admin responsibilities and seeing a partial census.

She’s doing a lot of reshaping and a lot of learning, she said, standing outside Room 10 of the San Diego Convention Center, where a daylong pre-course on practice management was being held at SHM’s annual meeting.

“There have been a lot of business things that have been overlooked and not addressed ever before,” she said.

The pre-course, “The Highly Effective Hospital Medicine Group: Using SHM’s Key Characteristics to Drive Performance,” was led by John Nelson, MD, MHM, and Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, and offered one useful lesson after another, Weisenbach said.

“One of the most practical portions of the session this morning was about dashboards, which is something I’m currently working on and could definitely use some insight,” Weisenbach said, adding that a list of metrics a dashboard should include and general guidelines on effective dashboards were things she’ll find useful in her own implementation.

The pre-course expanded on the key principles and traits for effective groups, including effective leadership, engaged hospitalists, adequate resources, alignment with the hospital, and care coordination across settings.

HM16 also included two and a half days of practice management sessions. Plus, management themes were woven through workshops and sprinkled into other sessions.

In one session on handling change, presenters used a surfing analogy: Like a surfer’s intensity just before riding a wave, a laser focus is called for when the moment arrives to execute change.

“Get ready for the ride,” said Steve Behnke, MD, president of Columbus, Ohio–based MedOne Hospital Physicians.

He discussed details of introducing the electronic health record system Epic at their group. There was 18 months of planning involving the practice’s whole operational team, then a doubling of the staffing ratios when the system went live, followed by catered lunches to gather feedback and identify problems.

Presenters emphasized the idea of agility in responding to obstacles and realizing that change affects everyone. Successful change, they said, involves seeing the process from all perspectives and leaders should expect resistance.

“Court them. Listen to them. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve done that,” said Dea Robinson, MA, MedOne’s vice president of operations. “Just listening and giving a platform.”

Back at the pre-course, Dr. Nelson, a hospital medicine consultant, talked about the importance of effective leadership.

“An effective group leader is a really key element of a successful group,” said The Hospitalist’s resident practice management columnist. “I’ve worked on-site with many hundreds of hospitalist groups around the country. There’s pretty good correlation between the effectiveness of the leader and the success of the group overall. But a good leader alone is not enough.”

He added that there are too “few leaders to go around.”

A good leader is an active one, he said, adding with funny-because-it’s-true humor that a lot of leaders say their main job is to make the schedule. Good leaders, he said, need to be focused on making the group high-functioning, should be available for administrative work even when not on a clinical shift, and must be able to delegate.

Another critical ingredient for a successful group, he said, is having engaged frontline hospitalists. Reviews need to be meaningful, and meetings should be held regularly with attendance essentially mandatory. Meetings, he said, might need a “tune-up,” with actual voting, written agendas, minutes taken, and group problem-solving above one-way information.

Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, on care coordination, said the relationship with primary care physicians is crucial though difficult.

“I think we have to go out of our way to build relationships,” he said. “And we don’t have occasion to see them, so we need to figure out a way to get to know our community.”

He suggested:

- Having dedicated transcriptionists for hospitalists,

- Tracking the rate at which discharge summaries are generated within 24 hours,

- Making sure PCPs know how to reach hospitalists, and

- Scheduling events—perhaps an annual event—for meeting PCPs and skill-nursing facility healthcare professionals.

It was clear that, in a field whose dimensions seem to be changing all the time, practice management remained a top interest at HM16. Robert Clothier, RN, a practice manager for the hospitalist group at ThedaCare in Wisconsin, recently switched from managing a cardiology clinic. He said there were huge differences in hospital medicine.

“The profession is growing so fast, and really nobody knows where the end is,” he said. “I can’t even think of anything where you could say, ‘Well, no, they’ll never do that.’ It’s endless. That’s going to be hardest thing. People are going to be pulling on us, and leadership from the hospital is going to be saying, ‘You guys need to do this.’

“So how can I control what we pick, and how can I make sure that we have the resources to do it?” TH

In November, Barbara Weisenbach took a new job as practice manager for the hospitalist group at Northwest Hospital in Seattle. She’s an experienced administrator but as for hospital medicine, not so much. And she is the group’s first full-fledged practice manager—as in, she’s not a physician taking on admin responsibilities and seeing a partial census.

She’s doing a lot of reshaping and a lot of learning, she said, standing outside Room 10 of the San Diego Convention Center, where a daylong pre-course on practice management was being held at SHM’s annual meeting.

“There have been a lot of business things that have been overlooked and not addressed ever before,” she said.

The pre-course, “The Highly Effective Hospital Medicine Group: Using SHM’s Key Characteristics to Drive Performance,” was led by John Nelson, MD, MHM, and Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, and offered one useful lesson after another, Weisenbach said.

“One of the most practical portions of the session this morning was about dashboards, which is something I’m currently working on and could definitely use some insight,” Weisenbach said, adding that a list of metrics a dashboard should include and general guidelines on effective dashboards were things she’ll find useful in her own implementation.

The pre-course expanded on the key principles and traits for effective groups, including effective leadership, engaged hospitalists, adequate resources, alignment with the hospital, and care coordination across settings.

HM16 also included two and a half days of practice management sessions. Plus, management themes were woven through workshops and sprinkled into other sessions.

In one session on handling change, presenters used a surfing analogy: Like a surfer’s intensity just before riding a wave, a laser focus is called for when the moment arrives to execute change.

“Get ready for the ride,” said Steve Behnke, MD, president of Columbus, Ohio–based MedOne Hospital Physicians.

He discussed details of introducing the electronic health record system Epic at their group. There was 18 months of planning involving the practice’s whole operational team, then a doubling of the staffing ratios when the system went live, followed by catered lunches to gather feedback and identify problems.

Presenters emphasized the idea of agility in responding to obstacles and realizing that change affects everyone. Successful change, they said, involves seeing the process from all perspectives and leaders should expect resistance.

“Court them. Listen to them. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve done that,” said Dea Robinson, MA, MedOne’s vice president of operations. “Just listening and giving a platform.”

Back at the pre-course, Dr. Nelson, a hospital medicine consultant, talked about the importance of effective leadership.

“An effective group leader is a really key element of a successful group,” said The Hospitalist’s resident practice management columnist. “I’ve worked on-site with many hundreds of hospitalist groups around the country. There’s pretty good correlation between the effectiveness of the leader and the success of the group overall. But a good leader alone is not enough.”

He added that there are too “few leaders to go around.”

A good leader is an active one, he said, adding with funny-because-it’s-true humor that a lot of leaders say their main job is to make the schedule. Good leaders, he said, need to be focused on making the group high-functioning, should be available for administrative work even when not on a clinical shift, and must be able to delegate.

Another critical ingredient for a successful group, he said, is having engaged frontline hospitalists. Reviews need to be meaningful, and meetings should be held regularly with attendance essentially mandatory. Meetings, he said, might need a “tune-up,” with actual voting, written agendas, minutes taken, and group problem-solving above one-way information.

Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, on care coordination, said the relationship with primary care physicians is crucial though difficult.

“I think we have to go out of our way to build relationships,” he said. “And we don’t have occasion to see them, so we need to figure out a way to get to know our community.”

He suggested:

- Having dedicated transcriptionists for hospitalists,

- Tracking the rate at which discharge summaries are generated within 24 hours,

- Making sure PCPs know how to reach hospitalists, and

- Scheduling events—perhaps an annual event—for meeting PCPs and skill-nursing facility healthcare professionals.

It was clear that, in a field whose dimensions seem to be changing all the time, practice management remained a top interest at HM16. Robert Clothier, RN, a practice manager for the hospitalist group at ThedaCare in Wisconsin, recently switched from managing a cardiology clinic. He said there were huge differences in hospital medicine.

“The profession is growing so fast, and really nobody knows where the end is,” he said. “I can’t even think of anything where you could say, ‘Well, no, they’ll never do that.’ It’s endless. That’s going to be hardest thing. People are going to be pulling on us, and leadership from the hospital is going to be saying, ‘You guys need to do this.’

“So how can I control what we pick, and how can I make sure that we have the resources to do it?” TH

Could value-based care raise False Claims Act liability?

As you begin to consider the switch to value-based care systems, be sure to safeguard against risks that could fuel false claims scrutiny by the government, legal experts advise.

A primary consideration is arrangements that include shared savings through coordinated care, said George B. Breen, a Washington-based health law attorney. For example, he said that the Stark Law could be implicated if a physician within a shared savings model receives a bonus payment for referring patients to specific providers. The Stark Law prohibits a physician from referring Medicare patients for designated health services to an entity with which the physician has a financial relationship.

“While there are a number of exceptions and safe harbors which would validate any such relationship, it’s something that needs to be thought through” from the start, Mr. Breen said in an interview. “You have to look at each factual circumstance separately because each is fact and circumstance dependent.”

The Anti-Kickback Statute also could come into play if value-based arrangements generate renumeration. The Anti-Kickback Statute prohibits offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving anything of value to induce or reward referrals or generate federal health care program business. Exceptions to the statute can be applied and should also be examined during arrangement development, Mr. Breen said.

Data collection and reporting also may present a problem, according to Seattle-based health law attorney Robert G. Homchick. Inaccurate data that become the basis for quality-based payments could lead to overpayment liability and indirect False Claims Act (FCA) exposure, he said.

In addition, “If the facts support that you were acting with intentional or deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard for how the data were gathered and reported that supported your value-based comp kicker, there could be direct False Claims Act liability,” Mr. Homchick said in an interview.

But Mr. Homchick stressed there are still many unknowns when it comes to how data-driven measurements will unfold.

“With MACRA, this is such a moving target as to exactly what type of data is going to form the basis for the metrics, and how the data need to be gathered and reported,” he said. “Many of those issues are still in play or still being developed at the agency level in terms of regulatory guidance.”

Current lawsuit could influence future cases

While it is too early to know every legal theory that could intersect with quality-based care, legal experts are closely watching a case that could offer insight into future claims.

In Duffy v. Lawrence Memorial Hospital, a former employee turned whistle-blower alleges that the Lawrence, Kan.–based hospital inflated its performance scores under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program to increase federal incentive payments. Hospital leaders deny they falsified data and claim the allegations are based on the whistle-blower’s “improper understanding of acceptable reporting times for patient arrival,” according the hospital’s court response. The FCA lawsuit is before the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas.

Notably, the government has declined to intervene in the lawsuit twice, Mr. Breen said. The case is continuing without government intervention, a trend that has become more common in recent years, he said. In 2015, whistle-blower cases in which U.S. Department of Justice declined to intervene led to $1.1 billion in recoveries for the government and $335 million in rewards for whistle-blowers, according to government data.

Mr. Homchick called the Lawrence Memorial lawsuit “troubling.”

“Providers are struggling with the complexity of the reporting requirements imposed by the layers of value-based payment programs implemented by both government and private payers,” he said. “The Lawrence Memorial case illustrates that the whistle-blower community will likely exploit the inevitable mistakes or missteps of providers attempting to comply with the increasingly byzantine quality-reporting requirements.”

The outcome of the Lawrence Memorial case could influence similar lawsuits involving value-based programs, Mr. Breen said.

“I think this theory that there is some false reporting, or false certification, is a theory that you will see being pursed in connection with some of these quality-based programs,” Mr. Breen said.

Early steps can curb legal risk

Asking questions and being proactive as new value-based models develop is key to mitigating legal dangers, experts said.

Ensure that new arrangements are analyzed for fraud and abuse risk exposure before finalizing, Mr. Breen advised.

“Have a comfort level about the arrangement” that’s being entered into, he added, and “have those arrangements vetted.”

Pay attention to data, added Michael E. Paulhus, an Atlanta-based health law attorney who specializes in FCA cases.

“The more data they collect, the more the government is paying attention to where you are in the range,” he said in an interview. “If you stick out on either end, that would be a risk profile that, as a physician, I would want to know. I would want to know where I sit in the data.”

When making reports regarding quality measures, include such reports in internal audits as part of regular compliance efforts, the experts suggested.

In addition, seek out resources early that can help prepare the practice for new quality-based regulations, Mr. Homchick said.

“There will be guidance coming out [regarding] eligibility for these value-based incentives,” he said. “That will require you and your staff to really pay attention and seek out resources and guidance to try to do this right. If you have the bandwidth to get out ahead of this, that would certainly be the best approach.”

On Twitter @legal_med

As you begin to consider the switch to value-based care systems, be sure to safeguard against risks that could fuel false claims scrutiny by the government, legal experts advise.

A primary consideration is arrangements that include shared savings through coordinated care, said George B. Breen, a Washington-based health law attorney. For example, he said that the Stark Law could be implicated if a physician within a shared savings model receives a bonus payment for referring patients to specific providers. The Stark Law prohibits a physician from referring Medicare patients for designated health services to an entity with which the physician has a financial relationship.

“While there are a number of exceptions and safe harbors which would validate any such relationship, it’s something that needs to be thought through” from the start, Mr. Breen said in an interview. “You have to look at each factual circumstance separately because each is fact and circumstance dependent.”

The Anti-Kickback Statute also could come into play if value-based arrangements generate renumeration. The Anti-Kickback Statute prohibits offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving anything of value to induce or reward referrals or generate federal health care program business. Exceptions to the statute can be applied and should also be examined during arrangement development, Mr. Breen said.

Data collection and reporting also may present a problem, according to Seattle-based health law attorney Robert G. Homchick. Inaccurate data that become the basis for quality-based payments could lead to overpayment liability and indirect False Claims Act (FCA) exposure, he said.

In addition, “If the facts support that you were acting with intentional or deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard for how the data were gathered and reported that supported your value-based comp kicker, there could be direct False Claims Act liability,” Mr. Homchick said in an interview.

But Mr. Homchick stressed there are still many unknowns when it comes to how data-driven measurements will unfold.

“With MACRA, this is such a moving target as to exactly what type of data is going to form the basis for the metrics, and how the data need to be gathered and reported,” he said. “Many of those issues are still in play or still being developed at the agency level in terms of regulatory guidance.”

Current lawsuit could influence future cases

While it is too early to know every legal theory that could intersect with quality-based care, legal experts are closely watching a case that could offer insight into future claims.

In Duffy v. Lawrence Memorial Hospital, a former employee turned whistle-blower alleges that the Lawrence, Kan.–based hospital inflated its performance scores under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program to increase federal incentive payments. Hospital leaders deny they falsified data and claim the allegations are based on the whistle-blower’s “improper understanding of acceptable reporting times for patient arrival,” according the hospital’s court response. The FCA lawsuit is before the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas.

Notably, the government has declined to intervene in the lawsuit twice, Mr. Breen said. The case is continuing without government intervention, a trend that has become more common in recent years, he said. In 2015, whistle-blower cases in which U.S. Department of Justice declined to intervene led to $1.1 billion in recoveries for the government and $335 million in rewards for whistle-blowers, according to government data.

Mr. Homchick called the Lawrence Memorial lawsuit “troubling.”

“Providers are struggling with the complexity of the reporting requirements imposed by the layers of value-based payment programs implemented by both government and private payers,” he said. “The Lawrence Memorial case illustrates that the whistle-blower community will likely exploit the inevitable mistakes or missteps of providers attempting to comply with the increasingly byzantine quality-reporting requirements.”

The outcome of the Lawrence Memorial case could influence similar lawsuits involving value-based programs, Mr. Breen said.

“I think this theory that there is some false reporting, or false certification, is a theory that you will see being pursed in connection with some of these quality-based programs,” Mr. Breen said.

Early steps can curb legal risk

Asking questions and being proactive as new value-based models develop is key to mitigating legal dangers, experts said.

Ensure that new arrangements are analyzed for fraud and abuse risk exposure before finalizing, Mr. Breen advised.

“Have a comfort level about the arrangement” that’s being entered into, he added, and “have those arrangements vetted.”

Pay attention to data, added Michael E. Paulhus, an Atlanta-based health law attorney who specializes in FCA cases.

“The more data they collect, the more the government is paying attention to where you are in the range,” he said in an interview. “If you stick out on either end, that would be a risk profile that, as a physician, I would want to know. I would want to know where I sit in the data.”

When making reports regarding quality measures, include such reports in internal audits as part of regular compliance efforts, the experts suggested.

In addition, seek out resources early that can help prepare the practice for new quality-based regulations, Mr. Homchick said.

“There will be guidance coming out [regarding] eligibility for these value-based incentives,” he said. “That will require you and your staff to really pay attention and seek out resources and guidance to try to do this right. If you have the bandwidth to get out ahead of this, that would certainly be the best approach.”

On Twitter @legal_med

As you begin to consider the switch to value-based care systems, be sure to safeguard against risks that could fuel false claims scrutiny by the government, legal experts advise.

A primary consideration is arrangements that include shared savings through coordinated care, said George B. Breen, a Washington-based health law attorney. For example, he said that the Stark Law could be implicated if a physician within a shared savings model receives a bonus payment for referring patients to specific providers. The Stark Law prohibits a physician from referring Medicare patients for designated health services to an entity with which the physician has a financial relationship.

“While there are a number of exceptions and safe harbors which would validate any such relationship, it’s something that needs to be thought through” from the start, Mr. Breen said in an interview. “You have to look at each factual circumstance separately because each is fact and circumstance dependent.”

The Anti-Kickback Statute also could come into play if value-based arrangements generate renumeration. The Anti-Kickback Statute prohibits offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving anything of value to induce or reward referrals or generate federal health care program business. Exceptions to the statute can be applied and should also be examined during arrangement development, Mr. Breen said.

Data collection and reporting also may present a problem, according to Seattle-based health law attorney Robert G. Homchick. Inaccurate data that become the basis for quality-based payments could lead to overpayment liability and indirect False Claims Act (FCA) exposure, he said.

In addition, “If the facts support that you were acting with intentional or deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard for how the data were gathered and reported that supported your value-based comp kicker, there could be direct False Claims Act liability,” Mr. Homchick said in an interview.

But Mr. Homchick stressed there are still many unknowns when it comes to how data-driven measurements will unfold.

“With MACRA, this is such a moving target as to exactly what type of data is going to form the basis for the metrics, and how the data need to be gathered and reported,” he said. “Many of those issues are still in play or still being developed at the agency level in terms of regulatory guidance.”

Current lawsuit could influence future cases

While it is too early to know every legal theory that could intersect with quality-based care, legal experts are closely watching a case that could offer insight into future claims.

In Duffy v. Lawrence Memorial Hospital, a former employee turned whistle-blower alleges that the Lawrence, Kan.–based hospital inflated its performance scores under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program to increase federal incentive payments. Hospital leaders deny they falsified data and claim the allegations are based on the whistle-blower’s “improper understanding of acceptable reporting times for patient arrival,” according the hospital’s court response. The FCA lawsuit is before the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas.

Notably, the government has declined to intervene in the lawsuit twice, Mr. Breen said. The case is continuing without government intervention, a trend that has become more common in recent years, he said. In 2015, whistle-blower cases in which U.S. Department of Justice declined to intervene led to $1.1 billion in recoveries for the government and $335 million in rewards for whistle-blowers, according to government data.

Mr. Homchick called the Lawrence Memorial lawsuit “troubling.”

“Providers are struggling with the complexity of the reporting requirements imposed by the layers of value-based payment programs implemented by both government and private payers,” he said. “The Lawrence Memorial case illustrates that the whistle-blower community will likely exploit the inevitable mistakes or missteps of providers attempting to comply with the increasingly byzantine quality-reporting requirements.”

The outcome of the Lawrence Memorial case could influence similar lawsuits involving value-based programs, Mr. Breen said.

“I think this theory that there is some false reporting, or false certification, is a theory that you will see being pursed in connection with some of these quality-based programs,” Mr. Breen said.

Early steps can curb legal risk

Asking questions and being proactive as new value-based models develop is key to mitigating legal dangers, experts said.

Ensure that new arrangements are analyzed for fraud and abuse risk exposure before finalizing, Mr. Breen advised.

“Have a comfort level about the arrangement” that’s being entered into, he added, and “have those arrangements vetted.”

Pay attention to data, added Michael E. Paulhus, an Atlanta-based health law attorney who specializes in FCA cases.

“The more data they collect, the more the government is paying attention to where you are in the range,” he said in an interview. “If you stick out on either end, that would be a risk profile that, as a physician, I would want to know. I would want to know where I sit in the data.”

When making reports regarding quality measures, include such reports in internal audits as part of regular compliance efforts, the experts suggested.

In addition, seek out resources early that can help prepare the practice for new quality-based regulations, Mr. Homchick said.

“There will be guidance coming out [regarding] eligibility for these value-based incentives,” he said. “That will require you and your staff to really pay attention and seek out resources and guidance to try to do this right. If you have the bandwidth to get out ahead of this, that would certainly be the best approach.”

On Twitter @legal_med

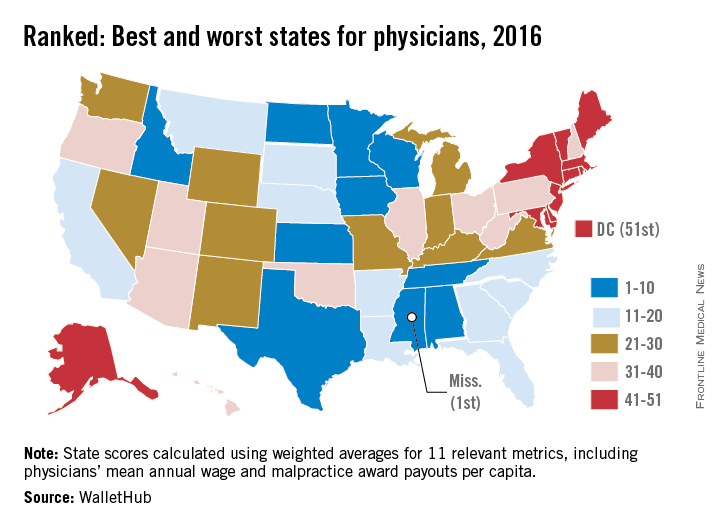

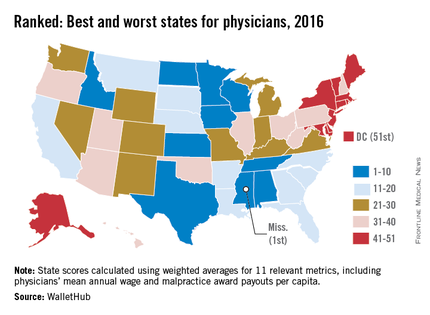

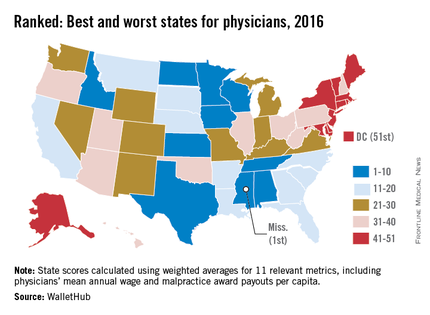

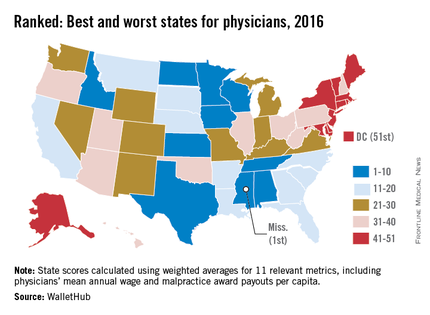

What are the best, worst states for physicians?

Should your future include a move to the South? A new report finds that Mississippi ranks as the best state to practice medicine, while the District of Columbia and New York are the least doctor-friendly areas in the United States.

The survey, conducted by personal finance website WalletHub, compares all 50 states and D.C. across 11 metrics, including physician starting salary, medical malpractice climate, provider competition, and annual wages – adjusted for cost of living. Data was derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Missouri Economic Research & Information Center, among other sources.

Researchers gave each metric a value between 0 and 100 and then calculated an overall score for each state using the weighted average across all metrics. Behind Mississippi, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota ranked among the best states to practice medicine, according to the report. Rhode Island, Maryland, and Connecticut ranked among the worst, just slightly better than New York and D.C.

“There are an abundance of differences in terms of the working environments faced by doctors across the nation,” WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez said in an interview. “The results, while not too surprising, may certainly be eye opening for many new or soon-to-be doctors. Doctors should understand what they’re signing up for in terms of wages, malpractice rates, and job security when they move to another state to practice.”

View the entire WalletHub analysis here.

On Twitter @legal_med

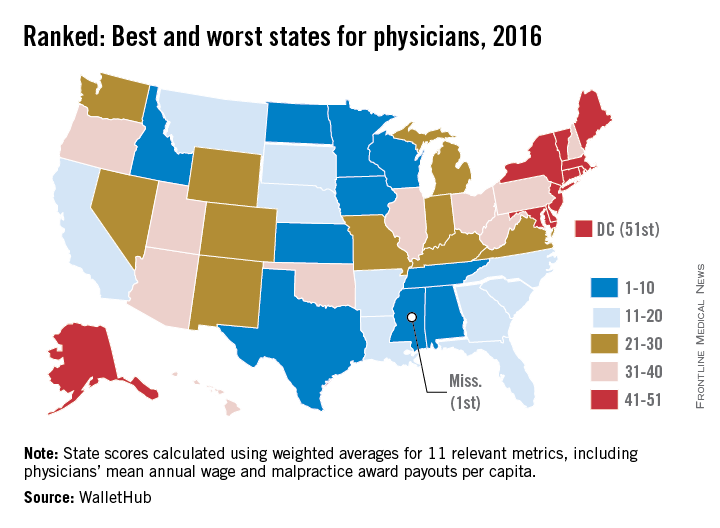

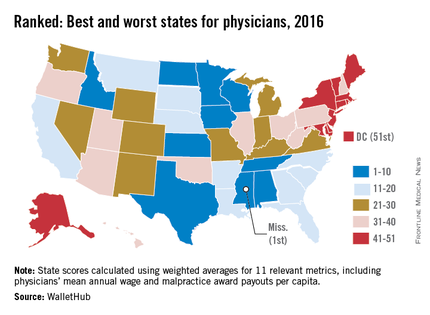

Should your future include a move to the South? A new report finds that Mississippi ranks as the best state to practice medicine, while the District of Columbia and New York are the least doctor-friendly areas in the United States.

The survey, conducted by personal finance website WalletHub, compares all 50 states and D.C. across 11 metrics, including physician starting salary, medical malpractice climate, provider competition, and annual wages – adjusted for cost of living. Data was derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Missouri Economic Research & Information Center, among other sources.

Researchers gave each metric a value between 0 and 100 and then calculated an overall score for each state using the weighted average across all metrics. Behind Mississippi, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota ranked among the best states to practice medicine, according to the report. Rhode Island, Maryland, and Connecticut ranked among the worst, just slightly better than New York and D.C.

“There are an abundance of differences in terms of the working environments faced by doctors across the nation,” WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez said in an interview. “The results, while not too surprising, may certainly be eye opening for many new or soon-to-be doctors. Doctors should understand what they’re signing up for in terms of wages, malpractice rates, and job security when they move to another state to practice.”

View the entire WalletHub analysis here.

On Twitter @legal_med

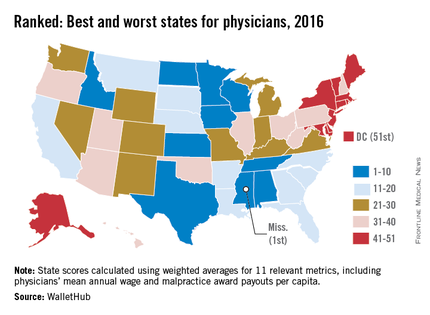

Should your future include a move to the South? A new report finds that Mississippi ranks as the best state to practice medicine, while the District of Columbia and New York are the least doctor-friendly areas in the United States.

The survey, conducted by personal finance website WalletHub, compares all 50 states and D.C. across 11 metrics, including physician starting salary, medical malpractice climate, provider competition, and annual wages – adjusted for cost of living. Data was derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Missouri Economic Research & Information Center, among other sources.

Researchers gave each metric a value between 0 and 100 and then calculated an overall score for each state using the weighted average across all metrics. Behind Mississippi, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota ranked among the best states to practice medicine, according to the report. Rhode Island, Maryland, and Connecticut ranked among the worst, just slightly better than New York and D.C.

“There are an abundance of differences in terms of the working environments faced by doctors across the nation,” WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez said in an interview. “The results, while not too surprising, may certainly be eye opening for many new or soon-to-be doctors. Doctors should understand what they’re signing up for in terms of wages, malpractice rates, and job security when they move to another state to practice.”

View the entire WalletHub analysis here.

On Twitter @legal_med

What are the best, worst states for physicians?

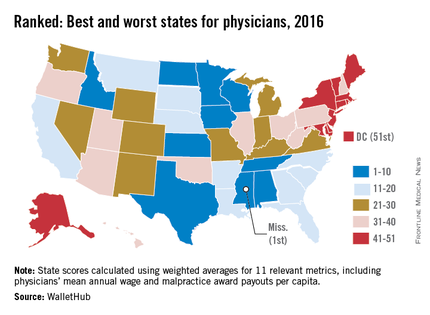

Should your future include a move to the South? A new report finds that Mississippi ranks as the best state to practice medicine, while the District of Columbia and New York are the least doctor-friendly areas in the United States.

The survey, conducted by personal finance website WalletHub, compares all 50 states and D.C. across 11 metrics, including physician starting salary, medical malpractice climate, provider competition, and annual wages – adjusted for cost of living. Data was derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Missouri Economic Research & Information Center, among other sources.

Researchers gave each metric a value between 0 and 100 and then calculated an overall score for each state using the weighted average across all metrics. Behind Mississippi, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota ranked among the best states to practice medicine, according to the report. Rhode Island, Maryland, and Connecticut ranked among the worst, just slightly better than New York and D.C.

“There are an abundance of differences in terms of the working environments faced by doctors across the nation,” WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez said in an interview. “The results, while not too surprising, may certainly be eye opening for many new or soon-to-be doctors. Doctors should understand what they’re signing up for in terms of wages, malpractice rates, and job security when they move to another state to practice.”

View the entire WalletHub analysis here.

On Twitter @legal_med

Should your future include a move to the South? A new report finds that Mississippi ranks as the best state to practice medicine, while the District of Columbia and New York are the least doctor-friendly areas in the United States.

The survey, conducted by personal finance website WalletHub, compares all 50 states and D.C. across 11 metrics, including physician starting salary, medical malpractice climate, provider competition, and annual wages – adjusted for cost of living. Data was derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Missouri Economic Research & Information Center, among other sources.

Researchers gave each metric a value between 0 and 100 and then calculated an overall score for each state using the weighted average across all metrics. Behind Mississippi, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota ranked among the best states to practice medicine, according to the report. Rhode Island, Maryland, and Connecticut ranked among the worst, just slightly better than New York and D.C.

“There are an abundance of differences in terms of the working environments faced by doctors across the nation,” WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez said in an interview. “The results, while not too surprising, may certainly be eye opening for many new or soon-to-be doctors. Doctors should understand what they’re signing up for in terms of wages, malpractice rates, and job security when they move to another state to practice.”

View the entire WalletHub analysis here.

On Twitter @legal_med

Should your future include a move to the South? A new report finds that Mississippi ranks as the best state to practice medicine, while the District of Columbia and New York are the least doctor-friendly areas in the United States.

The survey, conducted by personal finance website WalletHub, compares all 50 states and D.C. across 11 metrics, including physician starting salary, medical malpractice climate, provider competition, and annual wages – adjusted for cost of living. Data was derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Missouri Economic Research & Information Center, among other sources.

Researchers gave each metric a value between 0 and 100 and then calculated an overall score for each state using the weighted average across all metrics. Behind Mississippi, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota ranked among the best states to practice medicine, according to the report. Rhode Island, Maryland, and Connecticut ranked among the worst, just slightly better than New York and D.C.

“There are an abundance of differences in terms of the working environments faced by doctors across the nation,” WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez said in an interview. “The results, while not too surprising, may certainly be eye opening for many new or soon-to-be doctors. Doctors should understand what they’re signing up for in terms of wages, malpractice rates, and job security when they move to another state to practice.”

View the entire WalletHub analysis here.

On Twitter @legal_med

Allegations: Current Trends in Medical Malpractice, Part 2

Most medical malpractice cases are still resolved in a courtroom—typically after years of preparation and personal torment. Yet, overall rates of paid medical malpractice claims among all physicians have been steadily decreasing over the past two decades, with reports showing decreases of 30% to 50% in paid claims since 2000.1-3 At the same time, while median payments and insurance premiums continued to increase until the mid-2000s, they now appear to have plateaued.1

None of these changes occurred in isolation. More than 30 states now have caps on noneconomic or total damages.2 As noted in part 1, since 2000, some states have enacted comprehensive tort reform.4 However, whether these changes in malpractice patterns can be attributed directly to specific policy changes remains a hotly contested issue.

Malpractice Risk in Emergency Medicine

To what extent do the trends in medical malpractice apply to emergency medicine (EM)? While emergency physicians’ (EPs’) perception of malpractice risk ranks higher than any other medical specialty,5 in a review of a large sample of malpractice claims from 1991 through 2005, EPs ranked in the middle among specialties with respect to annual risk of a malpractice claim.6 Moreover, the annual risk of a claim for EPs is just under 8%, compared to 7.4% for all physicians. Yet, for neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery—the specialties with the highest overall risk of malpractice claims—the annual risk approaches 20%.6 Regarding payout statistics, less than one-fifth of the claims against EPs resulted in payment.6 In a review of a separate insurance database of closed claims, EPs were named as the primary defendant in only 19% of cases.7

Despite the discrepancies between perceived risk and absolute risk of malpractice claims among EPs, malpractice lawsuits continue to affect the practice of EM. This is evidenced in several surveys, in which the majority of EP participants admitted to practicing “defensive medicine” by ordering tests that were felt to be unnecessary and did so in response to perceived malpractice risk.8-10 Perceived risk also accounts for the significant variation in decision-making in the ED with respect to diagnostic testing and hospitalization of patients.11 One would expect that lowering malpractice risk would result in less so-called unnecessary testing, but whether or not this is truly the case remains to be seen.

Effects of Malpractice Reform

A study by Waxman et al12 on the effects of significant malpractice tort reform in ED care in Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina found no difference in rates of imaging studies, charges, or patient admissions. Furthermore, legislation reform did not increase plaintiff onus to prove proximate “gross negligence” rather than simply a breach from “reasonably skillful and careful” medicine.12 These findings suggest that perception of malpractice risk might simply be serving as a proxy for physicians’ underlying risk tolerance, and be less subject to influence by external forces.

Areas Associated With Malpractice Risk

A number of closed-claim databases attempted to identify the characteristics of patient encounters that can lead to malpractice claims, including patient conditions and sources of error. Diagnostic errors have consistently been found to be the leading cause of malpractice claims, accounting for 28% to 65% of claims, followed by inappropriate management of medical treatment and improper performance of a procedure.7,13-16 A January 2016 benchmarking system report by CRICO Strategies found that 30% of 23,658 medical malpractice claims filed between 2009 through 2013 cited failures in communication as a factor.17 The report also revealed that among these failed communications, those that occurred between health care providers are more likely to result in payout compared to miscommunications between providers and patients.17 This report further noted 70% to 80% of claims closed without payment.7,16 Closed claims were significantly more likely to involve serious injuries or death.7,18 Leading conditions that resulted in claims include myocardial infarction, nonspecific chest pain, symptoms involving the abdomen or pelvis, appendicitis, and orthopedic injuries.7,13,16

Diagnostic Errors

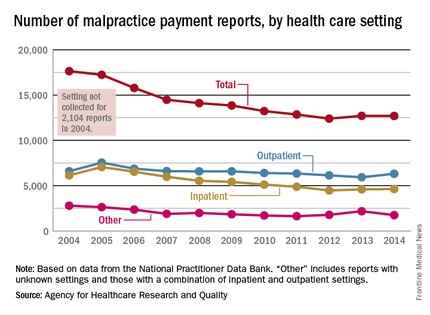

Errors in diagnosis have been attributed to multiple factors in the ED. The two most common factors were failure to order tests and failure to perform an adequate history and physical examination, both of which contribute to rationalization of the practice of defensive medicine under the current tort system.13 Other significant factors associated with errors in diagnosis include misinterpretation of test results or imaging studies and failure to obtain an appropriate consultation. Processes contributing to each of these potential errors include mistakes in judgment, lack of knowledge, miscommunication, and insufficient documentation (Table).15

Strategies for Reducing Malpractice Risk

In part 1, we listed several strategies EPs could adopt to help reduce malpractice risk. In this section, we will discuss in further detail how these strategies help mitigate malpractice claims.

Patient Communication

Open communication with patients is paramount in reducing the risk of a malpractice allegation. Patients are more likely to become angry or frustrated if they sense a physician is not listening to or addressing their concerns. These patients are in turn more likely to file a complaint if they are harmed or experience a bad outcome during their stay in the ED.

Situations in which patients are unable to provide pertinent information also place the EP at significant risk, as the provider must make decisions without full knowledge of the case. Communication with potential resources such as nursing home staff, the patient’s family, and emergency medical service providers to obtain additional information can help reduce risk.

Of course, when evaluating and treating patients, the EP should always take the time to listen to the patient’s concerns during the encounter to ensure his or her needs have been addressed. In the event of a patient allegation or complaint, the EP should make the effort to explore and de-escalate the situation before the patient is discharged.

Discharge Care and Instructions

According to CRICO, premature discharge as a factor in medical malpractice liability results from inadequate assessment and missed opportunities in 41% of diagnosis-related ED cases.16 The following situation illustrates a brief example of such a missed opportunity: A provider makes a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in a patient presenting with fever and abdominal pain but whose urinalysis is suspect for contamination and in whom no pelvic examination was performed to rule out other etiologies. When the same patient later returns to the ED with worse abdominal pain, a sterile urine culture invalidates the diagnosis of UTI, and further evaluation leads to a final diagnosis of ruptured appendix.

Prior to discharging any patient, the EP should provide clear and concise at-home care instructions in a manner in which the patient can understand. Clear instructions on how the patient is to manage his or her care after discharge are vital, and failure to do so in terms the patient can understand can create problems if a harmful result occurs. This is especially important in patients with whom there is a communication barrier—eg, language barrier, hearing impairment, cognitive deficit, intoxication, or violent or irrational behavior. In these situations, the EP should always take advantage of available resources and tools such as language lines, interpreters, discharge planners, psychiatric staff, and supportive family members to help reconcile any communication barriers. These measures will in turn optimize patient outcome and reduce the risk of a later malpractice allegation.

Board Certification

All physicians should maintain their respective board certification and specialty training requirements. Efforts in this area help providers to stay up to date in current practice standards and new developments, thus reducing one’s risk of incurring a malpractice claim.