User login

2016 Medicare fee schedule: What should you know?

The comments are in and shaping of the final Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for 2016 rests now in the hands of officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What are the key provisions doctors need to know about to practice successfully in 2016? Experts gave their opinions in a webinar sponsored by the American Health Lawyers Association (AHLA).

Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS)

CMS proposes to audit not only physician participants, but also vendors who submit quality measure data on behalf of doctors, under the 2016 proposed fee schedule. The agency recommends that vendors make available contact information for each eligible practitioner on behalf of whom it submits data and retain data submitted to CMS for PQRS for 7 years.

Doctors who fail to report on nine quality measures for PQRS will not automatically face trouble, according to Daniel F. Shay, a health law attorney in Philadelphia. In general, individual physicians in PQRS must report on at least nine measures covering three National Quality Strategy (NQS) domains for at least 50% of their Medicare patient base. But if fewer than nine measures are reported, physicians have the chance to explain themselves.

“In some cases, a practice may not have at least nine measures that apply to it, Mr. Shay said. “The [eligible practitioner] would then be able to report on fewer than nine measures, but would be subject to the measure application validity process, which basically means CMS audits the provider to prove they couldn’t have reported on all of the required measures.”

Also, CMS proposes extending participation in PQRS to doctors who practice in critical access hospitals, according to the 2016 proposed fee schedule. PQRS is a voluntary quality reporting program that applies adjustments to payments based on benchmarks. CMS is suggesting that physicians who practice in certain critical access hospitals now have the option to participate in the program – such doctors were previously excluded.

Incident to service

When overseeing care that is “incident to” service, CMS proposes that billing physicians also act as supervising physicians. The proposal could significantly impact group practices who do not typically use that structure, said Washington health law attorney Julie E. Kass during the AHLA webinar.

Incident to is defined as services furnished incident to a physician’s professional services over the course of a patient’s diagnosis or treatment. Medicare pays for services rendered by employees of a physician only when all “incident to” criteria are met. Those criteria include that services rendered by nonphysicians are under the direct supervision of a physician physically in the same office suite. In the proposed 2016 rule, CMS seeks to clarify that the billing physician must be the same physician who supervises the ancillary personnel. Previously, group practices may have billed under the provider who ordered the treatment, according to Ms. Kass.

“It sounds simple, but then you put it into the context of what happens in a real life practice,” she said. “I think a lot of practices, in operationalizing this rule, have generally used the ordering physician as the physician who billed for the service without paying a lot of attention to who was the actual supervising physician.”

Group practices may want to rethink how they bill for incident to services, and ensure the billing physician is the one who supervises the treatment, she advised.

The Stark Law

Proposed changes to regulations implementing the Stark Law could make it easier for physicians to hire new nonphysician providers (NPP) to provide primary care. Under the fee schedule proposal, hospitals would be allowed to assist in the recruitment of health professionals for physician practices. Currently, hospitals may not because remuneration could be considered a compensation relationship between the hospital and physician practice. The proposed change aims to promote care team collaboration and help curb primary care shortages.

The exception would permit recruitment assistance and retention payment from a hospital, rural health clinic, or federally qualified health center to a physician practice to employ an NPP. However, the NPP would have to be a bona fide employee of the physician practice and provide primary care services. CMS defines an NPP as a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, or certified nurse-midwife. CMS is also recommending a cap on the total remuneration and duration of assistance provided.

The limits aim to “make sure the physicians have skin in the game in bringing in the NPP,” Ms. Kass said. “It’s not all going to be the burden of hospital to provide recruiting assistance, but rather the physician has to need and want the NPP enough to be willing to bring them in as well without total support and assistance.”

Value-Based Payment Modifier Program

CMS proposes a new way to determine the extent of payment cuts and bonuses in the Value-Based Payment Modifier program. The program evaluates the performance of solo practitioners and groups on the quality and cost of care they provide to fee-for-service Medicare patients.

In 2016, the agency proposes to adjust payments based on the size of the participating group and to determine that size by reviewing claims data and its Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS)-generated list. CMS would apply whichever number is lower in PECOS or claims data.

Now is a good time for doctors to check their PECOS data to ensure the information is accurate and up to date, Mr. Shay recommended.

As many expected, the Value-Based Payment Modifier is slowly expanding to encompass more physicians. Beginning Jan. 1, 2015, the value modifier was applied to physician payments under the fee schedule for groups of 100 or more. In January 2016, it will be applied to physician payments for doctors in groups of 10 or more. In 2017, the modifier will apply to solo practitioners and physicians in groups of two or more. (All modifiers are based on performance periods 2 years prior.)

PQRS will continue to play a central role in the Value-Based Payment Modifier system, Mr. Shay added. CMS is proposing to use the PQRS reporting period for 2016 as the basis for the 2018 value modifier. The agency will draw from the group reporting option and individual EP reporting mechanisms proposed for 2016.

“We’re seeing just more interconnection between these two systems,” Mr. Shay said.

Physician Compare

Physicians should expect to have more information about their performance reported to the Physician Compare website under the proposed 2016 fee schedule. The site already continues information on physician education, location, group affiliations, and status in quality programs. CMS now wants to include performance rates on 2015 PQRS cardiovascular disease prevention measures for doctors who report them, in support of the Million Hearts program. Additionally, CMS proposes that groups receiving a pay increase under the Value-Based Payment Modifier Program report the data to the website. Doctors also would continue reporting information about patient experiences under the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS) survey program. The surveys are designed to capture a patient’s experience receiving care from their physician.

Mr. Shay noted that one concern with the Physician Compare website is that doctors have little recourse to challenge information on the site. Physicians have only a 30-day window to review information about themselves and correct errors.

“There is no formal appeals mechanism for the website,” Mr. Shay.

CMS is currently reviewing feedback and comments submitted about the proposed physician fee schedule before issuing the final schedule, usually in November.

On Twitter @legal_med

The comments are in and shaping of the final Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for 2016 rests now in the hands of officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What are the key provisions doctors need to know about to practice successfully in 2016? Experts gave their opinions in a webinar sponsored by the American Health Lawyers Association (AHLA).

Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS)

CMS proposes to audit not only physician participants, but also vendors who submit quality measure data on behalf of doctors, under the 2016 proposed fee schedule. The agency recommends that vendors make available contact information for each eligible practitioner on behalf of whom it submits data and retain data submitted to CMS for PQRS for 7 years.

Doctors who fail to report on nine quality measures for PQRS will not automatically face trouble, according to Daniel F. Shay, a health law attorney in Philadelphia. In general, individual physicians in PQRS must report on at least nine measures covering three National Quality Strategy (NQS) domains for at least 50% of their Medicare patient base. But if fewer than nine measures are reported, physicians have the chance to explain themselves.

“In some cases, a practice may not have at least nine measures that apply to it, Mr. Shay said. “The [eligible practitioner] would then be able to report on fewer than nine measures, but would be subject to the measure application validity process, which basically means CMS audits the provider to prove they couldn’t have reported on all of the required measures.”

Also, CMS proposes extending participation in PQRS to doctors who practice in critical access hospitals, according to the 2016 proposed fee schedule. PQRS is a voluntary quality reporting program that applies adjustments to payments based on benchmarks. CMS is suggesting that physicians who practice in certain critical access hospitals now have the option to participate in the program – such doctors were previously excluded.

Incident to service

When overseeing care that is “incident to” service, CMS proposes that billing physicians also act as supervising physicians. The proposal could significantly impact group practices who do not typically use that structure, said Washington health law attorney Julie E. Kass during the AHLA webinar.

Incident to is defined as services furnished incident to a physician’s professional services over the course of a patient’s diagnosis or treatment. Medicare pays for services rendered by employees of a physician only when all “incident to” criteria are met. Those criteria include that services rendered by nonphysicians are under the direct supervision of a physician physically in the same office suite. In the proposed 2016 rule, CMS seeks to clarify that the billing physician must be the same physician who supervises the ancillary personnel. Previously, group practices may have billed under the provider who ordered the treatment, according to Ms. Kass.

“It sounds simple, but then you put it into the context of what happens in a real life practice,” she said. “I think a lot of practices, in operationalizing this rule, have generally used the ordering physician as the physician who billed for the service without paying a lot of attention to who was the actual supervising physician.”

Group practices may want to rethink how they bill for incident to services, and ensure the billing physician is the one who supervises the treatment, she advised.

The Stark Law

Proposed changes to regulations implementing the Stark Law could make it easier for physicians to hire new nonphysician providers (NPP) to provide primary care. Under the fee schedule proposal, hospitals would be allowed to assist in the recruitment of health professionals for physician practices. Currently, hospitals may not because remuneration could be considered a compensation relationship between the hospital and physician practice. The proposed change aims to promote care team collaboration and help curb primary care shortages.

The exception would permit recruitment assistance and retention payment from a hospital, rural health clinic, or federally qualified health center to a physician practice to employ an NPP. However, the NPP would have to be a bona fide employee of the physician practice and provide primary care services. CMS defines an NPP as a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, or certified nurse-midwife. CMS is also recommending a cap on the total remuneration and duration of assistance provided.

The limits aim to “make sure the physicians have skin in the game in bringing in the NPP,” Ms. Kass said. “It’s not all going to be the burden of hospital to provide recruiting assistance, but rather the physician has to need and want the NPP enough to be willing to bring them in as well without total support and assistance.”

Value-Based Payment Modifier Program

CMS proposes a new way to determine the extent of payment cuts and bonuses in the Value-Based Payment Modifier program. The program evaluates the performance of solo practitioners and groups on the quality and cost of care they provide to fee-for-service Medicare patients.

In 2016, the agency proposes to adjust payments based on the size of the participating group and to determine that size by reviewing claims data and its Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS)-generated list. CMS would apply whichever number is lower in PECOS or claims data.

Now is a good time for doctors to check their PECOS data to ensure the information is accurate and up to date, Mr. Shay recommended.

As many expected, the Value-Based Payment Modifier is slowly expanding to encompass more physicians. Beginning Jan. 1, 2015, the value modifier was applied to physician payments under the fee schedule for groups of 100 or more. In January 2016, it will be applied to physician payments for doctors in groups of 10 or more. In 2017, the modifier will apply to solo practitioners and physicians in groups of two or more. (All modifiers are based on performance periods 2 years prior.)

PQRS will continue to play a central role in the Value-Based Payment Modifier system, Mr. Shay added. CMS is proposing to use the PQRS reporting period for 2016 as the basis for the 2018 value modifier. The agency will draw from the group reporting option and individual EP reporting mechanisms proposed for 2016.

“We’re seeing just more interconnection between these two systems,” Mr. Shay said.

Physician Compare

Physicians should expect to have more information about their performance reported to the Physician Compare website under the proposed 2016 fee schedule. The site already continues information on physician education, location, group affiliations, and status in quality programs. CMS now wants to include performance rates on 2015 PQRS cardiovascular disease prevention measures for doctors who report them, in support of the Million Hearts program. Additionally, CMS proposes that groups receiving a pay increase under the Value-Based Payment Modifier Program report the data to the website. Doctors also would continue reporting information about patient experiences under the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS) survey program. The surveys are designed to capture a patient’s experience receiving care from their physician.

Mr. Shay noted that one concern with the Physician Compare website is that doctors have little recourse to challenge information on the site. Physicians have only a 30-day window to review information about themselves and correct errors.

“There is no formal appeals mechanism for the website,” Mr. Shay.

CMS is currently reviewing feedback and comments submitted about the proposed physician fee schedule before issuing the final schedule, usually in November.

On Twitter @legal_med

The comments are in and shaping of the final Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for 2016 rests now in the hands of officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What are the key provisions doctors need to know about to practice successfully in 2016? Experts gave their opinions in a webinar sponsored by the American Health Lawyers Association (AHLA).

Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS)

CMS proposes to audit not only physician participants, but also vendors who submit quality measure data on behalf of doctors, under the 2016 proposed fee schedule. The agency recommends that vendors make available contact information for each eligible practitioner on behalf of whom it submits data and retain data submitted to CMS for PQRS for 7 years.

Doctors who fail to report on nine quality measures for PQRS will not automatically face trouble, according to Daniel F. Shay, a health law attorney in Philadelphia. In general, individual physicians in PQRS must report on at least nine measures covering three National Quality Strategy (NQS) domains for at least 50% of their Medicare patient base. But if fewer than nine measures are reported, physicians have the chance to explain themselves.

“In some cases, a practice may not have at least nine measures that apply to it, Mr. Shay said. “The [eligible practitioner] would then be able to report on fewer than nine measures, but would be subject to the measure application validity process, which basically means CMS audits the provider to prove they couldn’t have reported on all of the required measures.”

Also, CMS proposes extending participation in PQRS to doctors who practice in critical access hospitals, according to the 2016 proposed fee schedule. PQRS is a voluntary quality reporting program that applies adjustments to payments based on benchmarks. CMS is suggesting that physicians who practice in certain critical access hospitals now have the option to participate in the program – such doctors were previously excluded.

Incident to service

When overseeing care that is “incident to” service, CMS proposes that billing physicians also act as supervising physicians. The proposal could significantly impact group practices who do not typically use that structure, said Washington health law attorney Julie E. Kass during the AHLA webinar.

Incident to is defined as services furnished incident to a physician’s professional services over the course of a patient’s diagnosis or treatment. Medicare pays for services rendered by employees of a physician only when all “incident to” criteria are met. Those criteria include that services rendered by nonphysicians are under the direct supervision of a physician physically in the same office suite. In the proposed 2016 rule, CMS seeks to clarify that the billing physician must be the same physician who supervises the ancillary personnel. Previously, group practices may have billed under the provider who ordered the treatment, according to Ms. Kass.

“It sounds simple, but then you put it into the context of what happens in a real life practice,” she said. “I think a lot of practices, in operationalizing this rule, have generally used the ordering physician as the physician who billed for the service without paying a lot of attention to who was the actual supervising physician.”

Group practices may want to rethink how they bill for incident to services, and ensure the billing physician is the one who supervises the treatment, she advised.

The Stark Law

Proposed changes to regulations implementing the Stark Law could make it easier for physicians to hire new nonphysician providers (NPP) to provide primary care. Under the fee schedule proposal, hospitals would be allowed to assist in the recruitment of health professionals for physician practices. Currently, hospitals may not because remuneration could be considered a compensation relationship between the hospital and physician practice. The proposed change aims to promote care team collaboration and help curb primary care shortages.

The exception would permit recruitment assistance and retention payment from a hospital, rural health clinic, or federally qualified health center to a physician practice to employ an NPP. However, the NPP would have to be a bona fide employee of the physician practice and provide primary care services. CMS defines an NPP as a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, or certified nurse-midwife. CMS is also recommending a cap on the total remuneration and duration of assistance provided.

The limits aim to “make sure the physicians have skin in the game in bringing in the NPP,” Ms. Kass said. “It’s not all going to be the burden of hospital to provide recruiting assistance, but rather the physician has to need and want the NPP enough to be willing to bring them in as well without total support and assistance.”

Value-Based Payment Modifier Program

CMS proposes a new way to determine the extent of payment cuts and bonuses in the Value-Based Payment Modifier program. The program evaluates the performance of solo practitioners and groups on the quality and cost of care they provide to fee-for-service Medicare patients.

In 2016, the agency proposes to adjust payments based on the size of the participating group and to determine that size by reviewing claims data and its Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS)-generated list. CMS would apply whichever number is lower in PECOS or claims data.

Now is a good time for doctors to check their PECOS data to ensure the information is accurate and up to date, Mr. Shay recommended.

As many expected, the Value-Based Payment Modifier is slowly expanding to encompass more physicians. Beginning Jan. 1, 2015, the value modifier was applied to physician payments under the fee schedule for groups of 100 or more. In January 2016, it will be applied to physician payments for doctors in groups of 10 or more. In 2017, the modifier will apply to solo practitioners and physicians in groups of two or more. (All modifiers are based on performance periods 2 years prior.)

PQRS will continue to play a central role in the Value-Based Payment Modifier system, Mr. Shay added. CMS is proposing to use the PQRS reporting period for 2016 as the basis for the 2018 value modifier. The agency will draw from the group reporting option and individual EP reporting mechanisms proposed for 2016.

“We’re seeing just more interconnection between these two systems,” Mr. Shay said.

Physician Compare

Physicians should expect to have more information about their performance reported to the Physician Compare website under the proposed 2016 fee schedule. The site already continues information on physician education, location, group affiliations, and status in quality programs. CMS now wants to include performance rates on 2015 PQRS cardiovascular disease prevention measures for doctors who report them, in support of the Million Hearts program. Additionally, CMS proposes that groups receiving a pay increase under the Value-Based Payment Modifier Program report the data to the website. Doctors also would continue reporting information about patient experiences under the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS) survey program. The surveys are designed to capture a patient’s experience receiving care from their physician.

Mr. Shay noted that one concern with the Physician Compare website is that doctors have little recourse to challenge information on the site. Physicians have only a 30-day window to review information about themselves and correct errors.

“There is no formal appeals mechanism for the website,” Mr. Shay.

CMS is currently reviewing feedback and comments submitted about the proposed physician fee schedule before issuing the final schedule, usually in November.

On Twitter @legal_med

ICD-10 testers recommend certified coders, lighter loads for October

The advice from those who have already tried coding with ICD-10? Hire a certified coder if you don’t have one on staff already.

“If a physician office doesn’t have a certified coder, it should,” according to Penny Osmon Bahr, director of Avastone Health Solutions, who took part in the final International Classification of Disease, tenth revision, “end-to-end” test conducted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid in July. “That’s just plain and simple.”

Ms. Osmon Bahr described coding as “the pulse point of how data are really consumed,” whether via ICD-10 or part of value-based contracting, research on patient outcomes, or incentives being driven by the CMS. “It takes coders to ensure that the data that is going out truly represents your patient population and the patients that you are treating.”

Some physician practices “haven’t invested in education for staff to become knowledgeable in coding or certified in coding. That could be a struggle as the world continues to evolve.”

Another bit of advice: Scale back on the number of patient visits you book in October. That will give extra time to learn and incorporate ICD-10 into work flows.

“One of the things that we’ve encouraged our physicians to do is they need to lighten their schedules in October to prepare for ICD-10 to make sure they are completing the documentation that’s needed and coding with the current codes,” Lori Albano, manager of EDI development and support with practice management and EHR software vendor Nextgen Healthcare of Atlanta. “So maybe the first 2 weeks they lighten [appointments] by 20%” and then set up a specific schedule to ramp back up to full capacity.

Ms. Albano also recommended a focused approach to learning new codes to help avoid being overwhelmed.

“Take the top 50-100 ICD-9 codes that you currently use and become familiar with those ICD-10 codes and the documentation required to support them,” she said. “Start documenting on that level now.”

Ms. Osmon Bahr also stressed thorough documentation.

“You always want to tell the most specific story about your patient that you can,” she said, based on the greater number and specificity of the ICD-10 code set.

Ms. Osmon Bahr and Ms. Albano both spoke positively of the experience of testing and said that CMS appears ready to make the transition. The agency announced on Aug. 28 that its final round of end-to-end testing found no new issues and that no CMS front-end issues led to claims rejections. Previous issues in prior test rounds have been resolved, the agency noted.

The advice from those who have already tried coding with ICD-10? Hire a certified coder if you don’t have one on staff already.

“If a physician office doesn’t have a certified coder, it should,” according to Penny Osmon Bahr, director of Avastone Health Solutions, who took part in the final International Classification of Disease, tenth revision, “end-to-end” test conducted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid in July. “That’s just plain and simple.”

Ms. Osmon Bahr described coding as “the pulse point of how data are really consumed,” whether via ICD-10 or part of value-based contracting, research on patient outcomes, or incentives being driven by the CMS. “It takes coders to ensure that the data that is going out truly represents your patient population and the patients that you are treating.”

Some physician practices “haven’t invested in education for staff to become knowledgeable in coding or certified in coding. That could be a struggle as the world continues to evolve.”

Another bit of advice: Scale back on the number of patient visits you book in October. That will give extra time to learn and incorporate ICD-10 into work flows.

“One of the things that we’ve encouraged our physicians to do is they need to lighten their schedules in October to prepare for ICD-10 to make sure they are completing the documentation that’s needed and coding with the current codes,” Lori Albano, manager of EDI development and support with practice management and EHR software vendor Nextgen Healthcare of Atlanta. “So maybe the first 2 weeks they lighten [appointments] by 20%” and then set up a specific schedule to ramp back up to full capacity.

Ms. Albano also recommended a focused approach to learning new codes to help avoid being overwhelmed.

“Take the top 50-100 ICD-9 codes that you currently use and become familiar with those ICD-10 codes and the documentation required to support them,” she said. “Start documenting on that level now.”

Ms. Osmon Bahr also stressed thorough documentation.

“You always want to tell the most specific story about your patient that you can,” she said, based on the greater number and specificity of the ICD-10 code set.

Ms. Osmon Bahr and Ms. Albano both spoke positively of the experience of testing and said that CMS appears ready to make the transition. The agency announced on Aug. 28 that its final round of end-to-end testing found no new issues and that no CMS front-end issues led to claims rejections. Previous issues in prior test rounds have been resolved, the agency noted.

The advice from those who have already tried coding with ICD-10? Hire a certified coder if you don’t have one on staff already.

“If a physician office doesn’t have a certified coder, it should,” according to Penny Osmon Bahr, director of Avastone Health Solutions, who took part in the final International Classification of Disease, tenth revision, “end-to-end” test conducted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid in July. “That’s just plain and simple.”

Ms. Osmon Bahr described coding as “the pulse point of how data are really consumed,” whether via ICD-10 or part of value-based contracting, research on patient outcomes, or incentives being driven by the CMS. “It takes coders to ensure that the data that is going out truly represents your patient population and the patients that you are treating.”

Some physician practices “haven’t invested in education for staff to become knowledgeable in coding or certified in coding. That could be a struggle as the world continues to evolve.”

Another bit of advice: Scale back on the number of patient visits you book in October. That will give extra time to learn and incorporate ICD-10 into work flows.

“One of the things that we’ve encouraged our physicians to do is they need to lighten their schedules in October to prepare for ICD-10 to make sure they are completing the documentation that’s needed and coding with the current codes,” Lori Albano, manager of EDI development and support with practice management and EHR software vendor Nextgen Healthcare of Atlanta. “So maybe the first 2 weeks they lighten [appointments] by 20%” and then set up a specific schedule to ramp back up to full capacity.

Ms. Albano also recommended a focused approach to learning new codes to help avoid being overwhelmed.

“Take the top 50-100 ICD-9 codes that you currently use and become familiar with those ICD-10 codes and the documentation required to support them,” she said. “Start documenting on that level now.”

Ms. Osmon Bahr also stressed thorough documentation.

“You always want to tell the most specific story about your patient that you can,” she said, based on the greater number and specificity of the ICD-10 code set.

Ms. Osmon Bahr and Ms. Albano both spoke positively of the experience of testing and said that CMS appears ready to make the transition. The agency announced on Aug. 28 that its final round of end-to-end testing found no new issues and that no CMS front-end issues led to claims rejections. Previous issues in prior test rounds have been resolved, the agency noted.

PQRS: Window is short to dispute the 2% pay cut

Assessments are complete, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has determined which physician practices will face a pay cut – officially, a “downward payment adjustment” – for failing to comply with the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). Doctors have just 2 months to challenge findings that they believe were made in error to spare themselves a cut in 2016.

The pay cut will apply to individual eligible practitioners and PQRS group practices that did not satisfactorily report data on quality measures in 2014. The 2% cut will be applied to all Part B covered services, according to a Sept. 9 CMS announcement.

To learn whether they are subject to the cut, physicians can review their 2014 PQRS feedback reports, which became available Sept. 8. The reports apply to doctors who submitted quality data in calendar year 2014. Feedback reports for 2015 will be available approximately this time next year.

To challenge PQRS determinations, physicians can submit an informal review between Sept. 9 and Nov. 9 and request that the CMS reevaluate incentive eligibility and adjustment determinations. Those requests can be made through the quality reporting portal. Physicians who request a review will be contacted via email of a final decision by the CMS within 90 days of their request. All decisions will be final and there will be no further review or appeal, according to the CMS.

It should not be surprising that physicians who did not satisfactorily comply with PQRS will see a 2% pay cut next year, said David Harlow, a health law and policy attorney based in Newton, Mass. What’s unusual, however, is that the informal review process does not include an avenue for an independent evaluation, Mr. Harlow said.

“It’s CMS reviewing a CMS decision,” he said in an interview. “From a provider perspective, there might be some skepticism about the independence of that review. CMS says this is not something that is subject to further administrative or judicial review. So there’s not an appeal.”

Mr. Harlow said that he would not be surprised if physician organizations advocate for further judicial relief in the process. CMS has previously provided avenues for administrative or judicial appeals of its decisions in other programs, he noted.

In its announcement, the agency outlined the ways in which physicians could have avoided the coming pay cut. This included reporting nine measures across three domains for 50% of Medicare patients, completing the GPRO Web Interface, or reporting at least one registry measures group for 20 patients, at least 11 of whom were Medicare Part B patients. Additionally, doctors could have reported three measures across one domain for 50% of Medicare patients, or satisfactorily participated in a qualified clinical data registry.

On Twitter @legal_med

Assessments are complete, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has determined which physician practices will face a pay cut – officially, a “downward payment adjustment” – for failing to comply with the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). Doctors have just 2 months to challenge findings that they believe were made in error to spare themselves a cut in 2016.

The pay cut will apply to individual eligible practitioners and PQRS group practices that did not satisfactorily report data on quality measures in 2014. The 2% cut will be applied to all Part B covered services, according to a Sept. 9 CMS announcement.

To learn whether they are subject to the cut, physicians can review their 2014 PQRS feedback reports, which became available Sept. 8. The reports apply to doctors who submitted quality data in calendar year 2014. Feedback reports for 2015 will be available approximately this time next year.

To challenge PQRS determinations, physicians can submit an informal review between Sept. 9 and Nov. 9 and request that the CMS reevaluate incentive eligibility and adjustment determinations. Those requests can be made through the quality reporting portal. Physicians who request a review will be contacted via email of a final decision by the CMS within 90 days of their request. All decisions will be final and there will be no further review or appeal, according to the CMS.

It should not be surprising that physicians who did not satisfactorily comply with PQRS will see a 2% pay cut next year, said David Harlow, a health law and policy attorney based in Newton, Mass. What’s unusual, however, is that the informal review process does not include an avenue for an independent evaluation, Mr. Harlow said.

“It’s CMS reviewing a CMS decision,” he said in an interview. “From a provider perspective, there might be some skepticism about the independence of that review. CMS says this is not something that is subject to further administrative or judicial review. So there’s not an appeal.”

Mr. Harlow said that he would not be surprised if physician organizations advocate for further judicial relief in the process. CMS has previously provided avenues for administrative or judicial appeals of its decisions in other programs, he noted.

In its announcement, the agency outlined the ways in which physicians could have avoided the coming pay cut. This included reporting nine measures across three domains for 50% of Medicare patients, completing the GPRO Web Interface, or reporting at least one registry measures group for 20 patients, at least 11 of whom were Medicare Part B patients. Additionally, doctors could have reported three measures across one domain for 50% of Medicare patients, or satisfactorily participated in a qualified clinical data registry.

On Twitter @legal_med

Assessments are complete, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has determined which physician practices will face a pay cut – officially, a “downward payment adjustment” – for failing to comply with the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). Doctors have just 2 months to challenge findings that they believe were made in error to spare themselves a cut in 2016.

The pay cut will apply to individual eligible practitioners and PQRS group practices that did not satisfactorily report data on quality measures in 2014. The 2% cut will be applied to all Part B covered services, according to a Sept. 9 CMS announcement.

To learn whether they are subject to the cut, physicians can review their 2014 PQRS feedback reports, which became available Sept. 8. The reports apply to doctors who submitted quality data in calendar year 2014. Feedback reports for 2015 will be available approximately this time next year.

To challenge PQRS determinations, physicians can submit an informal review between Sept. 9 and Nov. 9 and request that the CMS reevaluate incentive eligibility and adjustment determinations. Those requests can be made through the quality reporting portal. Physicians who request a review will be contacted via email of a final decision by the CMS within 90 days of their request. All decisions will be final and there will be no further review or appeal, according to the CMS.

It should not be surprising that physicians who did not satisfactorily comply with PQRS will see a 2% pay cut next year, said David Harlow, a health law and policy attorney based in Newton, Mass. What’s unusual, however, is that the informal review process does not include an avenue for an independent evaluation, Mr. Harlow said.

“It’s CMS reviewing a CMS decision,” he said in an interview. “From a provider perspective, there might be some skepticism about the independence of that review. CMS says this is not something that is subject to further administrative or judicial review. So there’s not an appeal.”

Mr. Harlow said that he would not be surprised if physician organizations advocate for further judicial relief in the process. CMS has previously provided avenues for administrative or judicial appeals of its decisions in other programs, he noted.

In its announcement, the agency outlined the ways in which physicians could have avoided the coming pay cut. This included reporting nine measures across three domains for 50% of Medicare patients, completing the GPRO Web Interface, or reporting at least one registry measures group for 20 patients, at least 11 of whom were Medicare Part B patients. Additionally, doctors could have reported three measures across one domain for 50% of Medicare patients, or satisfactorily participated in a qualified clinical data registry.

On Twitter @legal_med

Hospitalists' Role in Improving Patient Experience: A Baldridge Winner's Perspective

Understanding and improving the patient care experience has become a vital component of delivering high quality care. According to a new survey of American Society for Quality (ASQ) healthcare quality experts, more than 80% of respondents said improving communications between caregivers and patients and easing access to treatment across the entire continuum of care should be top priorities for improving patient experience. For Hill Country Memorial (HCM) in Fredericksburg, Texas, winner of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, accomplishing this kind of top-level patient experience performance involved engaging physicians—particularly hospitalists—using voice of the customer (VOC) input.

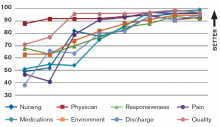

HCM did not achieve overnight success, however; instead, the facility achieved year-over-year improvement in finance and growth, patient experience, quality of care, and workforce environment and engagement (see Figure 1).

HCM developed a systematic VOC input-to-action process in which listening and learning methods during annual planning led them to institute a hospitalist program. Results included:

- Improved access to primary care, achieved by increasing the physicians’ hours of availability in their clinics, and improved work-life balance, enhancing engagement and alignment of the medical staff and HCM;

- Reductions in delays in admissions, discharges, and length of stay; and

- Real-time review and management of clinical data, not just during the daily rounding as had been done previously.

One of the major hurdles in the way of achieving patient satisfaction, according to the ASQ patient experience survey, is care that is fragmented and uncoordinated because of communication issues. HCM has overcome those hurdles using strategies such as a daily afternoon huddle in which hospitalists meet with a multidisciplinary team so that everyone understands patient action plans and current concerns. The process of discharge planning begins in these huddles so that more complex issues are initiated on day one of the hospital stay.

A new rounding communication process, called GIFT for greet, inform, find out, and time, has dramatically improved patient satisfaction and engagement. GIFT enables hospitalists to greet a patient with a personal introduction and an explanation of their position and responsibilities. Hospitalists always sit while engaging the patient, and they make it a point to acknowledge not only the patient but everyone present in the room. Personalized “baseball cards” featuring the hospitalist’s background, including personal interests and hobbies, are handed out to patients or family members. Hospitalists take time to inform the patient and appropriate family members and caregivers of all diagnostic test results and the clinical response of treatment to date. Treatment plans and further diagnostic tests or procedures are discussed. A report of all consultants who have joined or will be joining in the care, along with their roles in the treatment planned, is fully vetted.

One key to a successful patient experience is discovering the concerns of the patient, family members, friends, and caregivers. Emotional issues become as important as the physical needs of the patient; these are openly addressed. Ask not “What’s the matter?” but instead “What matters to you?”

Timing the hospitalist’s return to see the patient and the anticipated date of transition of care is the last item in the rounding interaction. The date should be as accurate as possible to reduce patient anxiety and help the patient understand that the hospitalist really cares.

The hospitalist program has also strengthened the relationship between nurses and physicians. Nurses know the hospitalists’ practice patterns well, which allows them to help manage patient interactions and minimize patient anxiety and frustration. The physician-patient relationship is reinforced when nurse leaders include hospitalist satisfaction questions during daily rounding to identify concerns that can be clarified or resolved in real time.

The systematic VOC approach has enabled HCM to design, manage, and improve its key work process at multiple levels of the organization. These processes are reviewed and refined periodically to respond to the changing healthcare environment and stay focused on creating value for customers.

Chip Caldwell is chairman of Caldwell Butler, a firm specializing in coaching organizations to achieve world class performance in margin improvement, patient experience, physician/clinical enterprise, and capacity optimization. Jayne Pope, MBA, RN, is CEO of Hill Country Memorial Hospital in Fredericksburg, Texas. James Partin, MD, is CMO at Hill Country Memorial.

Understanding and improving the patient care experience has become a vital component of delivering high quality care. According to a new survey of American Society for Quality (ASQ) healthcare quality experts, more than 80% of respondents said improving communications between caregivers and patients and easing access to treatment across the entire continuum of care should be top priorities for improving patient experience. For Hill Country Memorial (HCM) in Fredericksburg, Texas, winner of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, accomplishing this kind of top-level patient experience performance involved engaging physicians—particularly hospitalists—using voice of the customer (VOC) input.

HCM did not achieve overnight success, however; instead, the facility achieved year-over-year improvement in finance and growth, patient experience, quality of care, and workforce environment and engagement (see Figure 1).

HCM developed a systematic VOC input-to-action process in which listening and learning methods during annual planning led them to institute a hospitalist program. Results included:

- Improved access to primary care, achieved by increasing the physicians’ hours of availability in their clinics, and improved work-life balance, enhancing engagement and alignment of the medical staff and HCM;

- Reductions in delays in admissions, discharges, and length of stay; and

- Real-time review and management of clinical data, not just during the daily rounding as had been done previously.

One of the major hurdles in the way of achieving patient satisfaction, according to the ASQ patient experience survey, is care that is fragmented and uncoordinated because of communication issues. HCM has overcome those hurdles using strategies such as a daily afternoon huddle in which hospitalists meet with a multidisciplinary team so that everyone understands patient action plans and current concerns. The process of discharge planning begins in these huddles so that more complex issues are initiated on day one of the hospital stay.

A new rounding communication process, called GIFT for greet, inform, find out, and time, has dramatically improved patient satisfaction and engagement. GIFT enables hospitalists to greet a patient with a personal introduction and an explanation of their position and responsibilities. Hospitalists always sit while engaging the patient, and they make it a point to acknowledge not only the patient but everyone present in the room. Personalized “baseball cards” featuring the hospitalist’s background, including personal interests and hobbies, are handed out to patients or family members. Hospitalists take time to inform the patient and appropriate family members and caregivers of all diagnostic test results and the clinical response of treatment to date. Treatment plans and further diagnostic tests or procedures are discussed. A report of all consultants who have joined or will be joining in the care, along with their roles in the treatment planned, is fully vetted.

One key to a successful patient experience is discovering the concerns of the patient, family members, friends, and caregivers. Emotional issues become as important as the physical needs of the patient; these are openly addressed. Ask not “What’s the matter?” but instead “What matters to you?”

Timing the hospitalist’s return to see the patient and the anticipated date of transition of care is the last item in the rounding interaction. The date should be as accurate as possible to reduce patient anxiety and help the patient understand that the hospitalist really cares.

The hospitalist program has also strengthened the relationship between nurses and physicians. Nurses know the hospitalists’ practice patterns well, which allows them to help manage patient interactions and minimize patient anxiety and frustration. The physician-patient relationship is reinforced when nurse leaders include hospitalist satisfaction questions during daily rounding to identify concerns that can be clarified or resolved in real time.

The systematic VOC approach has enabled HCM to design, manage, and improve its key work process at multiple levels of the organization. These processes are reviewed and refined periodically to respond to the changing healthcare environment and stay focused on creating value for customers.

Chip Caldwell is chairman of Caldwell Butler, a firm specializing in coaching organizations to achieve world class performance in margin improvement, patient experience, physician/clinical enterprise, and capacity optimization. Jayne Pope, MBA, RN, is CEO of Hill Country Memorial Hospital in Fredericksburg, Texas. James Partin, MD, is CMO at Hill Country Memorial.

Understanding and improving the patient care experience has become a vital component of delivering high quality care. According to a new survey of American Society for Quality (ASQ) healthcare quality experts, more than 80% of respondents said improving communications between caregivers and patients and easing access to treatment across the entire continuum of care should be top priorities for improving patient experience. For Hill Country Memorial (HCM) in Fredericksburg, Texas, winner of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, accomplishing this kind of top-level patient experience performance involved engaging physicians—particularly hospitalists—using voice of the customer (VOC) input.

HCM did not achieve overnight success, however; instead, the facility achieved year-over-year improvement in finance and growth, patient experience, quality of care, and workforce environment and engagement (see Figure 1).

HCM developed a systematic VOC input-to-action process in which listening and learning methods during annual planning led them to institute a hospitalist program. Results included:

- Improved access to primary care, achieved by increasing the physicians’ hours of availability in their clinics, and improved work-life balance, enhancing engagement and alignment of the medical staff and HCM;

- Reductions in delays in admissions, discharges, and length of stay; and

- Real-time review and management of clinical data, not just during the daily rounding as had been done previously.

One of the major hurdles in the way of achieving patient satisfaction, according to the ASQ patient experience survey, is care that is fragmented and uncoordinated because of communication issues. HCM has overcome those hurdles using strategies such as a daily afternoon huddle in which hospitalists meet with a multidisciplinary team so that everyone understands patient action plans and current concerns. The process of discharge planning begins in these huddles so that more complex issues are initiated on day one of the hospital stay.

A new rounding communication process, called GIFT for greet, inform, find out, and time, has dramatically improved patient satisfaction and engagement. GIFT enables hospitalists to greet a patient with a personal introduction and an explanation of their position and responsibilities. Hospitalists always sit while engaging the patient, and they make it a point to acknowledge not only the patient but everyone present in the room. Personalized “baseball cards” featuring the hospitalist’s background, including personal interests and hobbies, are handed out to patients or family members. Hospitalists take time to inform the patient and appropriate family members and caregivers of all diagnostic test results and the clinical response of treatment to date. Treatment plans and further diagnostic tests or procedures are discussed. A report of all consultants who have joined or will be joining in the care, along with their roles in the treatment planned, is fully vetted.

One key to a successful patient experience is discovering the concerns of the patient, family members, friends, and caregivers. Emotional issues become as important as the physical needs of the patient; these are openly addressed. Ask not “What’s the matter?” but instead “What matters to you?”

Timing the hospitalist’s return to see the patient and the anticipated date of transition of care is the last item in the rounding interaction. The date should be as accurate as possible to reduce patient anxiety and help the patient understand that the hospitalist really cares.

The hospitalist program has also strengthened the relationship between nurses and physicians. Nurses know the hospitalists’ practice patterns well, which allows them to help manage patient interactions and minimize patient anxiety and frustration. The physician-patient relationship is reinforced when nurse leaders include hospitalist satisfaction questions during daily rounding to identify concerns that can be clarified or resolved in real time.

The systematic VOC approach has enabled HCM to design, manage, and improve its key work process at multiple levels of the organization. These processes are reviewed and refined periodically to respond to the changing healthcare environment and stay focused on creating value for customers.

Chip Caldwell is chairman of Caldwell Butler, a firm specializing in coaching organizations to achieve world class performance in margin improvement, patient experience, physician/clinical enterprise, and capacity optimization. Jayne Pope, MBA, RN, is CEO of Hill Country Memorial Hospital in Fredericksburg, Texas. James Partin, MD, is CMO at Hill Country Memorial.

Clinical Care Conundrums Provide Learning Potential for Hospitalists

At A Glance

Series: Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts

Title: Clinical Care Conundrums: Challenging Diagnoses in Hospital Medicine

Edited by: James C. Pile, Thomas E. Baudendistel, Brian Harte

Series Editors: Scott Flanders, Sanjay Saint

Pages: 208

Clinical Care Conundrums is written in 22 chapters, each discussing a clinical case presentation in a format similar to the series by the same name, published frequently in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

An expert clinician’s approach to the “clinical conundrums” is disclosed using the presentation of an actual patient case in a prototypical “morning report” style. As in a patient care situation, sequential pieces of information are provided to the expert clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus of each case is the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the commentator.

Excerpt

“Clinicians rely heavily on diagnostic test information, yet diagnostic tests are also susceptible to error. About 18% of critical laboratory results are judged nonrepresentative of the patient’s clinical condition after a chart review. …CT scans have 1.7% misinterpretation rate. Pathologic discrepancies occur in 11%-19% of cancer biopsy specimens. These data should remind clinicians to question…”

Each case provides great learning potential, not only in the unusual presentation of common diseases or more typical presentations of unusual diseases, but also in discussions of the possibilities in differential diagnoses. The range of information is wide. Readers are taken through discussions of conditions infrequently encountered but potentially fatal in the event of missed or delayed diagnosis, such as strongyloides hyperinfection, a condition that we are reminded is not always accompanied by eosinophilia. Some discussions of the more common conditions include:

- Evaluation of confusion;

- Etiologies of cirrhosis;

- Malignancies associated with hypercalcemia; and

- Work-up for new-onset seizures.

My interest remained high throughout the book, because I never knew what to expect. For example, a patient presenting with acute chest pain caused by esophageal perforation resulting in delayed diagnosis might follow the index case presentation of Whipple’s disease. We are also reminded that, despite the insistence of Gregory House, MD, (Dr. House is the titular character from the television series “House”) that “it’s never lupus,” it sometimes is actually lupus. A couple of interesting lupus cases are presented in a realistically perplexing manner, followed by beneficial discussion.

Analysis

The real value in this book lies in continued reminders of how and why clinicians make diagnostic errors. In fact, an early chapter in the book deals explicitly with improving diagnostic safety.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, reminds us in the introductory chapter that diagnostic errors comprise nearly one in five preventable adverse events. Until recently, diagnostic errors have been given relatively little attention, most likely because they are difficult to measure and harder to fix.

As hospital-based providers, the more awareness we have about the “anatomy and physiology” of both good and faulty decision making, the more likely we are to make better decisions. This book can be a crucial resource for any hospital-based care provider.

Dr. Lindsey is medical director of hospital-based physician services at Hospital Corporation of America (HCA).

At A Glance

Series: Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts

Title: Clinical Care Conundrums: Challenging Diagnoses in Hospital Medicine

Edited by: James C. Pile, Thomas E. Baudendistel, Brian Harte

Series Editors: Scott Flanders, Sanjay Saint

Pages: 208

Clinical Care Conundrums is written in 22 chapters, each discussing a clinical case presentation in a format similar to the series by the same name, published frequently in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

An expert clinician’s approach to the “clinical conundrums” is disclosed using the presentation of an actual patient case in a prototypical “morning report” style. As in a patient care situation, sequential pieces of information are provided to the expert clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus of each case is the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the commentator.

Excerpt

“Clinicians rely heavily on diagnostic test information, yet diagnostic tests are also susceptible to error. About 18% of critical laboratory results are judged nonrepresentative of the patient’s clinical condition after a chart review. …CT scans have 1.7% misinterpretation rate. Pathologic discrepancies occur in 11%-19% of cancer biopsy specimens. These data should remind clinicians to question…”

Each case provides great learning potential, not only in the unusual presentation of common diseases or more typical presentations of unusual diseases, but also in discussions of the possibilities in differential diagnoses. The range of information is wide. Readers are taken through discussions of conditions infrequently encountered but potentially fatal in the event of missed or delayed diagnosis, such as strongyloides hyperinfection, a condition that we are reminded is not always accompanied by eosinophilia. Some discussions of the more common conditions include:

- Evaluation of confusion;

- Etiologies of cirrhosis;

- Malignancies associated with hypercalcemia; and

- Work-up for new-onset seizures.

My interest remained high throughout the book, because I never knew what to expect. For example, a patient presenting with acute chest pain caused by esophageal perforation resulting in delayed diagnosis might follow the index case presentation of Whipple’s disease. We are also reminded that, despite the insistence of Gregory House, MD, (Dr. House is the titular character from the television series “House”) that “it’s never lupus,” it sometimes is actually lupus. A couple of interesting lupus cases are presented in a realistically perplexing manner, followed by beneficial discussion.

Analysis

The real value in this book lies in continued reminders of how and why clinicians make diagnostic errors. In fact, an early chapter in the book deals explicitly with improving diagnostic safety.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, reminds us in the introductory chapter that diagnostic errors comprise nearly one in five preventable adverse events. Until recently, diagnostic errors have been given relatively little attention, most likely because they are difficult to measure and harder to fix.

As hospital-based providers, the more awareness we have about the “anatomy and physiology” of both good and faulty decision making, the more likely we are to make better decisions. This book can be a crucial resource for any hospital-based care provider.

Dr. Lindsey is medical director of hospital-based physician services at Hospital Corporation of America (HCA).

At A Glance

Series: Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts

Title: Clinical Care Conundrums: Challenging Diagnoses in Hospital Medicine

Edited by: James C. Pile, Thomas E. Baudendistel, Brian Harte

Series Editors: Scott Flanders, Sanjay Saint

Pages: 208

Clinical Care Conundrums is written in 22 chapters, each discussing a clinical case presentation in a format similar to the series by the same name, published frequently in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

An expert clinician’s approach to the “clinical conundrums” is disclosed using the presentation of an actual patient case in a prototypical “morning report” style. As in a patient care situation, sequential pieces of information are provided to the expert clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus of each case is the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the commentator.

Excerpt

“Clinicians rely heavily on diagnostic test information, yet diagnostic tests are also susceptible to error. About 18% of critical laboratory results are judged nonrepresentative of the patient’s clinical condition after a chart review. …CT scans have 1.7% misinterpretation rate. Pathologic discrepancies occur in 11%-19% of cancer biopsy specimens. These data should remind clinicians to question…”

Each case provides great learning potential, not only in the unusual presentation of common diseases or more typical presentations of unusual diseases, but also in discussions of the possibilities in differential diagnoses. The range of information is wide. Readers are taken through discussions of conditions infrequently encountered but potentially fatal in the event of missed or delayed diagnosis, such as strongyloides hyperinfection, a condition that we are reminded is not always accompanied by eosinophilia. Some discussions of the more common conditions include:

- Evaluation of confusion;

- Etiologies of cirrhosis;

- Malignancies associated with hypercalcemia; and

- Work-up for new-onset seizures.

My interest remained high throughout the book, because I never knew what to expect. For example, a patient presenting with acute chest pain caused by esophageal perforation resulting in delayed diagnosis might follow the index case presentation of Whipple’s disease. We are also reminded that, despite the insistence of Gregory House, MD, (Dr. House is the titular character from the television series “House”) that “it’s never lupus,” it sometimes is actually lupus. A couple of interesting lupus cases are presented in a realistically perplexing manner, followed by beneficial discussion.

Analysis

The real value in this book lies in continued reminders of how and why clinicians make diagnostic errors. In fact, an early chapter in the book deals explicitly with improving diagnostic safety.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, reminds us in the introductory chapter that diagnostic errors comprise nearly one in five preventable adverse events. Until recently, diagnostic errors have been given relatively little attention, most likely because they are difficult to measure and harder to fix.

As hospital-based providers, the more awareness we have about the “anatomy and physiology” of both good and faulty decision making, the more likely we are to make better decisions. This book can be a crucial resource for any hospital-based care provider.

Dr. Lindsey is medical director of hospital-based physician services at Hospital Corporation of America (HCA).

Hospitalist-Led Quality Initiatives Plentiful at Community Hospitals

Community hospitals offer multiple opportunities for hospitalists to become involved in both quality assurance and quality improvement. To help steer the right approach and avoid possible missteps, it’s important to acknowledge the differences between the community and academic settings, according to two medical directors with whom we spoke.

For example, in the rural, 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital where Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, SFHM, is medical director for hospital-based quality, cost effectiveness is king.

“We live on a thin margin, and being sure we provide cost-effective care is the difference between having adequate nursing and not,” he says. It’s a critical difference from academic institutions, he notes, where “there is protected time to do QI, research, and administrative tasks.”

Dr. Ferrance advises those interested in tackling quality projects to “make sure that the project is tied to quality measures and that you’re being cognizant of the cost impact.”

Although much of the work around quality assurance and quality improvement in the community hospital setting is being tackled by nonphysician administrative partners, “those people are usually more than happy to develop a physician partner,” says Colleen A. McCoy, MD, PhD, medical director for hospital medicine at Williamsport (Pa.) Regional Medical Center, a part of the Susquehanna Health System.

“The idea is to look for quality projects where there is a quantifiable financial payoff to the hospital,” she says. That could be a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) core measure or helping to rewrite an order set for new inpatient guidelines on stroke, as Dr. McCoy did at her hospital.

First Order of Business

Dr. McCoy has been actively engaged in quality initiatives since she joined Williams-port in 2012. She cautions new hospitalists to spend the first six months at their new job developing a reputation for clinical excellence and attention to detail.

“Having a reputation that is respected clinically opens many doors,” she says. As generalists, hospitalists interact with a wider variety of staff than specialists. This leads to broad early exposure to a diverse group of decision makers in your institution. “As a hospitalist, you can get a lot of credibility in your organization much sooner than, for example, a young cardiologist or a young gastroenterologist,” she notes.

It is also important for new hospitalists to be mindful of their position in the organization and to watch how their institutions work and operate, so that when they propose a project they are not doing so from a critical standpoint.

“Unrequested input is often seen as criticism,” she says.

Dr. Ferrance agrees. “It’s always a good idea to make sure we focus on processes and not on people in the process.”

Meeting the Mark

“If you want to leapfrog into doing things quickly, you have to be very savvy about the cost impact of your quality improvement,” continues Dr. McCoy. She and Dr. Ferrance advise those just getting started to consider tackling core measures that are reported to CMS or to identify other quality improvement projects that can be financially quantified.

Early on at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital, Dr. Ferrance participated in root cause analyses and developed (at that time) paper-based standard order sets with quality measures attached to them.

Because of her attention to detail during her orientation at Williamsport, Dr. McCoy, who had been a clinical instructor at Emory University and worked for Kaiser Permanente, quickly spotted some necessary omissions regarding DVT prophylaxis. She helped rewrite the ICU admission order sets, inserting a query for DVT prophylaxis. That one intervention helped to increase compliance on a CMS core measure.

Assess Advancement Ops

Is your community hospital open to QI projects? Dr. McCoy says candidates should ask direct questions during job interviews to assess a prospective employer’s approach to quality. She suggests two fair questions:

- Is it possible, within my first two years here as a junior staff member, to participate in a QI project?

- If I were successful in that venture, is this organization open and able to give me more opportunities in that field?

It is key for the medical director to know who in the administrative organization of the hospital would really appreciate a physician partner or physician champion for new projects. If young hospitalists are interested in such projects, they should make that known to their medical directors.

“Having the senior person in your group make a connection with your [administrative] partner is how things get done in the community medical center,” Dr. McCoy says.

Dr. Ferrance’s HM group comprises four physicians and one nurse practitioner, so “there are plenty of QI projects to go around.”

“I would be more than happy to give them [junior staff hospitalists] any QI project they are interested in taking on,” he adds. “With medicine evolving as it does, we need to revisit processes every two to three years.” For example, drug shortages and cost increases often necessitate formulary cutbacks and the need for a change in administration protocols.

When selecting a QI project, it pays to stay ahead of the game, Dr. McCoy says. She encourages hospitalists to be aware of the next core measures and volunteer to help develop guidelines. She helped create a new protocol for inpatient tissue plasminogen activator (tPa) evaluation for acute stroke, which was a recent recommendation for stroke center certification. This approach was key in helping Williamsport retain its accreditation as a stroke center. The hospital has garnered multiple accolades from the Joint Commission, U.S. News and World Report, and other reporting agencies.

“The community setting is a much smaller world than academia,” she says. But smaller can be good for one’s career advancement. “If you hit a project out of the park and it makes your hospital look better, you can very quickly get a promotion or an increase in other opportunities. These types of projects may lead to the hospital asking, ‘Have you thought about being director of the hospital medicine group or taking a leadership role in hospital operations?’”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Community hospitals offer multiple opportunities for hospitalists to become involved in both quality assurance and quality improvement. To help steer the right approach and avoid possible missteps, it’s important to acknowledge the differences between the community and academic settings, according to two medical directors with whom we spoke.

For example, in the rural, 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital where Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, SFHM, is medical director for hospital-based quality, cost effectiveness is king.

“We live on a thin margin, and being sure we provide cost-effective care is the difference between having adequate nursing and not,” he says. It’s a critical difference from academic institutions, he notes, where “there is protected time to do QI, research, and administrative tasks.”

Dr. Ferrance advises those interested in tackling quality projects to “make sure that the project is tied to quality measures and that you’re being cognizant of the cost impact.”

Although much of the work around quality assurance and quality improvement in the community hospital setting is being tackled by nonphysician administrative partners, “those people are usually more than happy to develop a physician partner,” says Colleen A. McCoy, MD, PhD, medical director for hospital medicine at Williamsport (Pa.) Regional Medical Center, a part of the Susquehanna Health System.

“The idea is to look for quality projects where there is a quantifiable financial payoff to the hospital,” she says. That could be a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) core measure or helping to rewrite an order set for new inpatient guidelines on stroke, as Dr. McCoy did at her hospital.

First Order of Business

Dr. McCoy has been actively engaged in quality initiatives since she joined Williams-port in 2012. She cautions new hospitalists to spend the first six months at their new job developing a reputation for clinical excellence and attention to detail.

“Having a reputation that is respected clinically opens many doors,” she says. As generalists, hospitalists interact with a wider variety of staff than specialists. This leads to broad early exposure to a diverse group of decision makers in your institution. “As a hospitalist, you can get a lot of credibility in your organization much sooner than, for example, a young cardiologist or a young gastroenterologist,” she notes.

It is also important for new hospitalists to be mindful of their position in the organization and to watch how their institutions work and operate, so that when they propose a project they are not doing so from a critical standpoint.

“Unrequested input is often seen as criticism,” she says.

Dr. Ferrance agrees. “It’s always a good idea to make sure we focus on processes and not on people in the process.”

Meeting the Mark

“If you want to leapfrog into doing things quickly, you have to be very savvy about the cost impact of your quality improvement,” continues Dr. McCoy. She and Dr. Ferrance advise those just getting started to consider tackling core measures that are reported to CMS or to identify other quality improvement projects that can be financially quantified.

Early on at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital, Dr. Ferrance participated in root cause analyses and developed (at that time) paper-based standard order sets with quality measures attached to them.

Because of her attention to detail during her orientation at Williamsport, Dr. McCoy, who had been a clinical instructor at Emory University and worked for Kaiser Permanente, quickly spotted some necessary omissions regarding DVT prophylaxis. She helped rewrite the ICU admission order sets, inserting a query for DVT prophylaxis. That one intervention helped to increase compliance on a CMS core measure.

Assess Advancement Ops

Is your community hospital open to QI projects? Dr. McCoy says candidates should ask direct questions during job interviews to assess a prospective employer’s approach to quality. She suggests two fair questions:

- Is it possible, within my first two years here as a junior staff member, to participate in a QI project?

- If I were successful in that venture, is this organization open and able to give me more opportunities in that field?

It is key for the medical director to know who in the administrative organization of the hospital would really appreciate a physician partner or physician champion for new projects. If young hospitalists are interested in such projects, they should make that known to their medical directors.

“Having the senior person in your group make a connection with your [administrative] partner is how things get done in the community medical center,” Dr. McCoy says.

Dr. Ferrance’s HM group comprises four physicians and one nurse practitioner, so “there are plenty of QI projects to go around.”

“I would be more than happy to give them [junior staff hospitalists] any QI project they are interested in taking on,” he adds. “With medicine evolving as it does, we need to revisit processes every two to three years.” For example, drug shortages and cost increases often necessitate formulary cutbacks and the need for a change in administration protocols.

When selecting a QI project, it pays to stay ahead of the game, Dr. McCoy says. She encourages hospitalists to be aware of the next core measures and volunteer to help develop guidelines. She helped create a new protocol for inpatient tissue plasminogen activator (tPa) evaluation for acute stroke, which was a recent recommendation for stroke center certification. This approach was key in helping Williamsport retain its accreditation as a stroke center. The hospital has garnered multiple accolades from the Joint Commission, U.S. News and World Report, and other reporting agencies.

“The community setting is a much smaller world than academia,” she says. But smaller can be good for one’s career advancement. “If you hit a project out of the park and it makes your hospital look better, you can very quickly get a promotion or an increase in other opportunities. These types of projects may lead to the hospital asking, ‘Have you thought about being director of the hospital medicine group or taking a leadership role in hospital operations?’”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Community hospitals offer multiple opportunities for hospitalists to become involved in both quality assurance and quality improvement. To help steer the right approach and avoid possible missteps, it’s important to acknowledge the differences between the community and academic settings, according to two medical directors with whom we spoke.

For example, in the rural, 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital where Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, SFHM, is medical director for hospital-based quality, cost effectiveness is king.

“We live on a thin margin, and being sure we provide cost-effective care is the difference between having adequate nursing and not,” he says. It’s a critical difference from academic institutions, he notes, where “there is protected time to do QI, research, and administrative tasks.”

Dr. Ferrance advises those interested in tackling quality projects to “make sure that the project is tied to quality measures and that you’re being cognizant of the cost impact.”