User login

Why Aren’t Doctors Following Guidelines?

One recent paper in Clinical Pediatrics, for example, chronicled low adherence to the 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute lipid screening guidelines in primary-care settings.1 Another cautioned providers to “mind the (implementation) gap” in venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients.2 A third found that lower adherence to guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for acute coronary syndrome patients was significantly associated with higher bleeding and mortality rates.3

Both clinical trials and real-world studies have demonstrated that when guidelines are applied, patients do better, says William Lewis, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and director of the Heart & Vascular Center at MetroHealth in Cleveland. So why aren’t they followed more consistently?

Experts in both HM and other disciplines cite multiple obstacles. Lack of evidence, conflicting evidence, or lack of awareness about evidence can all conspire against the main goal of helping providers deliver consistent high-value care, says Christopher Moriates, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“In our day-to-day lives as hospitalists, for the vast majority probably of what we do there’s no clear guideline or there’s a guideline that doesn’t necessarily apply to the patient standing in front of me,” he says.

Even when a guideline is clear and relevant, other doctors say inadequate dissemination and implementation can still derail quality improvement efforts.

“A lot of what we do as physicians is what we learned in residency, and to incorporate the new data is difficult,” says Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Feldman believes many doctors have yet to integrate recently revised hypertension and cholesterol guidelines into their practice, for example. Some guidelines have proven more complex or controversial, limiting their adoption.

“I know I struggle to keep up with all of the guidelines, and I’m in a big academic center where people are talking about them all the time, and I’m working with residents who are talking about them all the time,” Dr. Feldman says.

Despite the remaining gaps, however, many researchers agree that momentum has built steadily over the past two decades toward a more systematic approach to creating solid evidence-based guidelines and integrating them into real-world decision making.

Emphasis on Evidence and Transparency

The term “evidence-based medicine” was coined in 1990 by Gordon Guyatt, MD, MSc, FRCPC, distinguished professor of medicine and clinical epidemiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. It’s played an active role in formulating guidelines for multiple organizations. The guideline-writing process, Dr. Guyatt says, once consisted of little more than self-selected clinicians sitting around a table.

“It used to be that a bunch of experts got together and decided and made the recommendations with very little in the way of a systematic process and certainly not evidence based,” he says.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center was among the pioneers pushing for a more systematic approach; the hospital began working on its own guidelines in 1995 and published the first of many the following year.

“We started evidence-based guidelines when the docs were still saying, ‘This is cookbook medicine. I don’t know if I want to do this or not,’” says Wendy Gerhardt, MSN, director of evidence-based decision making in the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s.

Some doctors also argued that clinical guidelines would stifle innovation, cramp their individual style, or intrude on their relationships with patients. Despite some lingering misgivings among clinicians, however, the process has gained considerable support. In 2000, an organization called the GRADE Working Group (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) began developing a new approach to raise the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

The group’s work led to a 2004 article in BMJ, and the journal subsequently published a six-part series about GRADE for clinicians.4 More recently, the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology also delved into the issue with a 15-part series detailing the GRADE methodology.5 Together, Dr. Guyatt says, the articles have become a go-to guide for guidelines and have helped solidify the focus on evidence.

Cincinnati Children’s and other institutions also have developed tools, and the Institute of Medicine has published guideline-writing standards.

“So it’s easier than it’s ever been to know whether or not you have a decent guideline in your hand,” Gerhardt says.

Likewise, medical organizations are more clearly explaining how they came up with different kinds of guidelines. Evidence-based and consensus guidelines aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, though consensus building is often used in the absence of high-quality evidence. Some organizations have limited the pool of evidence for guidelines to randomized controlled trial data.

“Unfortunately, for us in the real world, we actually have to make decisions even when there’s not enough data,” Dr. Feldman says.

Sometimes, the best available evidence may be observational studies, and some committees still try to reach a consensus based on that evidence and on the panelists’ professional opinions.

Dr. Guyatt agrees that it’s “absolutely not” true that evidence-based guidelines require randomized controlled trials. “What you need for any recommendation is a thorough review and summary of the best available evidence,” he says.

As part of each final document, Cincinnati Children’s details how it created the guideline, when the literature searches occurred, how the committee reached a consensus, and which panelists participated in the deliberations. The information, Gerhardt says, allows anyone else to “make some sensible decisions about whether or not it’s a guideline you want to use.”

Guideline-crafting institutions are also focusing more on the proper makeup of their panels. In general, Dr. Guyatt says, a panel with more than 10 people can be unwieldy. Guidelines that include many specific recommendations, however, may require multiple subsections, each with its own committee.

Dr. Guyatt is careful to note that, like many other experts, he has multiple potential conflicts of interest, such as working on the anti-thrombotic guidelines issued by the American College of Chest Physicians. Committees, he says, have become increasingly aware of how properly handling conflicts (financial or otherwise) can be critical in building and maintaining trust among clinicians and patients. One technique is to ensure that a diversity of opinions is reflected among a committee whose experts have various conflicts. If one expert’s company makes drug A, for example, then the committee also includes experts involved with drugs B or C. As an alternative, some committees have explicitly barred anyone with a conflict of interest from participating at all.

But experts often provide crucial input, Dr. Guyatt says, and several committees have adopted variations of a middle-ground approach. In an approach that he favors, all guideline-formulating panelists are conflict-free but begin their work by meeting with a separate group of experts who may have some conflicts but can help point out the main issues. The panelists then deliberate and write a draft of the recommendations, after which they meet again with the experts to receive feedback before finalizing the draft.

In a related approach, experts sit on the panel and discuss the evidence, but those with conflicts recuse themselves before the group votes on any recommendations. Delineating between discussions of the evidence and discussions of recommendations can be tricky, though, increasing the risk that a conflict of interest may influence the outcome. Even so, Dr. Guyatt says the model is still preferable to other alternatives.

Getting the Word Out

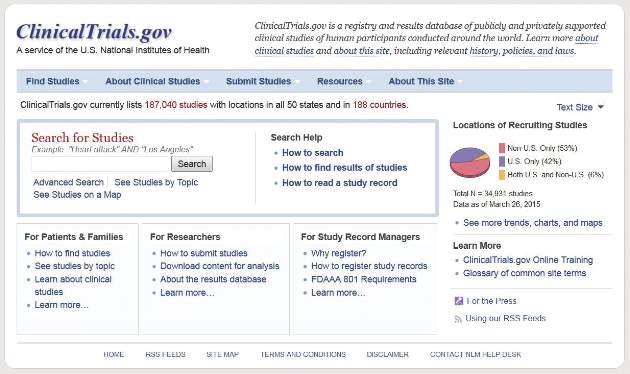

Once guidelines have been crafted and vetted, how can hospitalists get up to speed on them? Dr. Feldman’s favorite go-to source is Guideline.gov, a national guideline clearinghouse that he calls one of the best compendiums of available information. Especially helpful, he adds, are details such as how the guidelines were created.

To help maximize his time, he also uses tools like NEJM Journal Watch, which sends daily emails on noteworthy articles and weekend roundups of the most important studies.

“It is a way of at least trying to keep up with what’s going on,” he says. Similarly, he adds, ACP Journal Club provides summaries of important new articles, The Hospitalist can help highlight important guidelines that affect HM, and CME meetings or online modules like SHMconsults.com can help doctors keep pace.

For the past decade, Dr. Guyatt has worked with another popular tool, a guideline-disseminating service called UpToDate. Many alternatives exist, such as DynaMed Plus.

“I think you just need to pick away,” Dr. Feldman says. “You need to decide that as a physician, as a lifelong learner, that you are going to do something that is going to keep you up-to-date. There are many ways of doing it. You just have to decide what you’re going to do and commit to it.”

Researchers are helping out by studying how to present new guidelines in ways that engage doctors and improve patient outcomes. Another trend is to make guidelines routinely accessible not only in electronic medical records but also on tablets and smartphones. Lisa Shieh, MD, PhD, FHM, a hospitalist and clinical professor of medicine at Stanford University Medical Center, has studied how best-practice alerts, or BPAs, impact adherence to guidelines covering the appropriate use of blood products. Dr. Shieh, who splits her time between quality improvement and hospital medicine, says getting new information and guidelines into clinicians’ hands can be a logistical challenge.

“At Stanford, we had a huge official campaign around the guidelines, and that did make some impact, but it wasn’t huge in improving appropriate blood use,” she says. When the medial center set up a BPA through the electronic medical record system, however, both overall and inappropriate blood use declined significantly. In fact, the percentage of providers ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count above 8 g/dL dropped from 60% to 25%.6

One difference maker, Dr. Shieh says, was providing education at the moment a doctor actually ordered blood. To avoid alert fatigue, the “smart BPA” fires only if a doctor tries to order blood and the patient’s hemoglobin is greater than 7 or 8 g/dL, depending on the diagnosis. If the doctor still wants to transfuse, the system requests a clinical indication for the exception.

Despite the clear improvement in appropriate use, the team wanted to understand why 25% of providers were still ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count greater than 8 despite the triggered BPA and whether additional interventions could yield further improvements. Through their study, the researchers documented several reasons for the continued ordering. In some cases, the system failed to properly document actual or potential bleeding as an indicator. In other cases, the ordering reflected a lack of consensus on the guidelines in fields like hematology and oncology.

One of the most intriguing reasons, though, was that residents often did the ordering at the behest of an attending who might have never seen the BPA.

“It’s not actually reaching the audience making the decision; it might be reaching the audience that’s just carrying out the order,” Dr. Shieh says.

The insight, she says, may provide an opportunity to talk with attending physicians who may not have completely bought into the guidelines and to involve the entire team in the decision-making process.

Hospitalists, she says, can play a vital role in guideline development and implementation, especially for strategies that include BPAs.

“I think they’re the perfect group to help use this technology wisely because they are at the front lines taking care of patients so they’ll know the best workflow of when these alerts fire and maybe which ones happen the most often,” Dr. Shieh says. “I think this is a fantastic opportunity to get more hospitalists involved in designing these alerts and collaborating with the IT folks.”

Even with widespread buy-in from providers, guidelines may not reach their full potential without a careful consideration of patients’ values and concerns. Experts say joint deliberations and discussions are especially important for guidelines that are complicated, controversial, or carrying potential risks that must be weighed against the benefits.

Some of the conversations are easy, with well-defined risks and benefits and clear patient preferences, but others must traverse vast tracts of gray area. Fortunately, Dr. Feldman says, more tools also are becoming available for this kind of shared decision making. Some use pictorial representations to help patients understand the potential outcomes of alternative courses of action or inaction.

“Sometimes, that pictorial representation is worth the 1,000 words that we wouldn’t be able to adequately describe otherwise,” he says.

Similarly, Cincinnati Children’s has developed tools to help to ease the shared decision-making process.

“We look where there’s equivocal evidence or no evidence and have developed tools that help the clinician have that conversation with the family and then have them informed enough that they can actually weigh in on what they want,” Gerhardt says. One end product is a card or trifold pamphlet that might help parents understand the benefits and side effects of alternate strategies.

“Typically, in medicine, we’re used to telling people what needs to be done,” she says. “So shared decision making is kind of a different thing for clinicians to engage in.” TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

- Valle CW, Binns HJ, Quadri-Sheriff M, Benuck I, Patel A. Physicians’ lack of adherence to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines for pediatric lipid screening. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(12):1200-1205.

- Maynard G, Jenkins IH, Merli GJ. Venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients: mind the (implementation) gap. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):582-588.

- Mehta RH, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Doing the right things and doing them the right way: association between hospital guideline adherence, dosing safety, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131(11):980-987.

- GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490

- Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726-735.

- 6. Chen JH, Fang DZ, Tim Goodnough L, Evans KH, Lee Porter M, Shieh L. Why providers transfuse blood products outside recommended guidelines in spite of integrated electronic best practice alerts. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):1-7.

One recent paper in Clinical Pediatrics, for example, chronicled low adherence to the 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute lipid screening guidelines in primary-care settings.1 Another cautioned providers to “mind the (implementation) gap” in venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients.2 A third found that lower adherence to guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for acute coronary syndrome patients was significantly associated with higher bleeding and mortality rates.3

Both clinical trials and real-world studies have demonstrated that when guidelines are applied, patients do better, says William Lewis, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and director of the Heart & Vascular Center at MetroHealth in Cleveland. So why aren’t they followed more consistently?

Experts in both HM and other disciplines cite multiple obstacles. Lack of evidence, conflicting evidence, or lack of awareness about evidence can all conspire against the main goal of helping providers deliver consistent high-value care, says Christopher Moriates, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“In our day-to-day lives as hospitalists, for the vast majority probably of what we do there’s no clear guideline or there’s a guideline that doesn’t necessarily apply to the patient standing in front of me,” he says.

Even when a guideline is clear and relevant, other doctors say inadequate dissemination and implementation can still derail quality improvement efforts.

“A lot of what we do as physicians is what we learned in residency, and to incorporate the new data is difficult,” says Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Feldman believes many doctors have yet to integrate recently revised hypertension and cholesterol guidelines into their practice, for example. Some guidelines have proven more complex or controversial, limiting their adoption.

“I know I struggle to keep up with all of the guidelines, and I’m in a big academic center where people are talking about them all the time, and I’m working with residents who are talking about them all the time,” Dr. Feldman says.

Despite the remaining gaps, however, many researchers agree that momentum has built steadily over the past two decades toward a more systematic approach to creating solid evidence-based guidelines and integrating them into real-world decision making.

Emphasis on Evidence and Transparency

The term “evidence-based medicine” was coined in 1990 by Gordon Guyatt, MD, MSc, FRCPC, distinguished professor of medicine and clinical epidemiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. It’s played an active role in formulating guidelines for multiple organizations. The guideline-writing process, Dr. Guyatt says, once consisted of little more than self-selected clinicians sitting around a table.

“It used to be that a bunch of experts got together and decided and made the recommendations with very little in the way of a systematic process and certainly not evidence based,” he says.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center was among the pioneers pushing for a more systematic approach; the hospital began working on its own guidelines in 1995 and published the first of many the following year.

“We started evidence-based guidelines when the docs were still saying, ‘This is cookbook medicine. I don’t know if I want to do this or not,’” says Wendy Gerhardt, MSN, director of evidence-based decision making in the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s.

Some doctors also argued that clinical guidelines would stifle innovation, cramp their individual style, or intrude on their relationships with patients. Despite some lingering misgivings among clinicians, however, the process has gained considerable support. In 2000, an organization called the GRADE Working Group (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) began developing a new approach to raise the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

The group’s work led to a 2004 article in BMJ, and the journal subsequently published a six-part series about GRADE for clinicians.4 More recently, the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology also delved into the issue with a 15-part series detailing the GRADE methodology.5 Together, Dr. Guyatt says, the articles have become a go-to guide for guidelines and have helped solidify the focus on evidence.

Cincinnati Children’s and other institutions also have developed tools, and the Institute of Medicine has published guideline-writing standards.

“So it’s easier than it’s ever been to know whether or not you have a decent guideline in your hand,” Gerhardt says.

Likewise, medical organizations are more clearly explaining how they came up with different kinds of guidelines. Evidence-based and consensus guidelines aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, though consensus building is often used in the absence of high-quality evidence. Some organizations have limited the pool of evidence for guidelines to randomized controlled trial data.

“Unfortunately, for us in the real world, we actually have to make decisions even when there’s not enough data,” Dr. Feldman says.

Sometimes, the best available evidence may be observational studies, and some committees still try to reach a consensus based on that evidence and on the panelists’ professional opinions.

Dr. Guyatt agrees that it’s “absolutely not” true that evidence-based guidelines require randomized controlled trials. “What you need for any recommendation is a thorough review and summary of the best available evidence,” he says.

As part of each final document, Cincinnati Children’s details how it created the guideline, when the literature searches occurred, how the committee reached a consensus, and which panelists participated in the deliberations. The information, Gerhardt says, allows anyone else to “make some sensible decisions about whether or not it’s a guideline you want to use.”

Guideline-crafting institutions are also focusing more on the proper makeup of their panels. In general, Dr. Guyatt says, a panel with more than 10 people can be unwieldy. Guidelines that include many specific recommendations, however, may require multiple subsections, each with its own committee.

Dr. Guyatt is careful to note that, like many other experts, he has multiple potential conflicts of interest, such as working on the anti-thrombotic guidelines issued by the American College of Chest Physicians. Committees, he says, have become increasingly aware of how properly handling conflicts (financial or otherwise) can be critical in building and maintaining trust among clinicians and patients. One technique is to ensure that a diversity of opinions is reflected among a committee whose experts have various conflicts. If one expert’s company makes drug A, for example, then the committee also includes experts involved with drugs B or C. As an alternative, some committees have explicitly barred anyone with a conflict of interest from participating at all.

But experts often provide crucial input, Dr. Guyatt says, and several committees have adopted variations of a middle-ground approach. In an approach that he favors, all guideline-formulating panelists are conflict-free but begin their work by meeting with a separate group of experts who may have some conflicts but can help point out the main issues. The panelists then deliberate and write a draft of the recommendations, after which they meet again with the experts to receive feedback before finalizing the draft.

In a related approach, experts sit on the panel and discuss the evidence, but those with conflicts recuse themselves before the group votes on any recommendations. Delineating between discussions of the evidence and discussions of recommendations can be tricky, though, increasing the risk that a conflict of interest may influence the outcome. Even so, Dr. Guyatt says the model is still preferable to other alternatives.

Getting the Word Out

Once guidelines have been crafted and vetted, how can hospitalists get up to speed on them? Dr. Feldman’s favorite go-to source is Guideline.gov, a national guideline clearinghouse that he calls one of the best compendiums of available information. Especially helpful, he adds, are details such as how the guidelines were created.

To help maximize his time, he also uses tools like NEJM Journal Watch, which sends daily emails on noteworthy articles and weekend roundups of the most important studies.

“It is a way of at least trying to keep up with what’s going on,” he says. Similarly, he adds, ACP Journal Club provides summaries of important new articles, The Hospitalist can help highlight important guidelines that affect HM, and CME meetings or online modules like SHMconsults.com can help doctors keep pace.

For the past decade, Dr. Guyatt has worked with another popular tool, a guideline-disseminating service called UpToDate. Many alternatives exist, such as DynaMed Plus.

“I think you just need to pick away,” Dr. Feldman says. “You need to decide that as a physician, as a lifelong learner, that you are going to do something that is going to keep you up-to-date. There are many ways of doing it. You just have to decide what you’re going to do and commit to it.”

Researchers are helping out by studying how to present new guidelines in ways that engage doctors and improve patient outcomes. Another trend is to make guidelines routinely accessible not only in electronic medical records but also on tablets and smartphones. Lisa Shieh, MD, PhD, FHM, a hospitalist and clinical professor of medicine at Stanford University Medical Center, has studied how best-practice alerts, or BPAs, impact adherence to guidelines covering the appropriate use of blood products. Dr. Shieh, who splits her time between quality improvement and hospital medicine, says getting new information and guidelines into clinicians’ hands can be a logistical challenge.

“At Stanford, we had a huge official campaign around the guidelines, and that did make some impact, but it wasn’t huge in improving appropriate blood use,” she says. When the medial center set up a BPA through the electronic medical record system, however, both overall and inappropriate blood use declined significantly. In fact, the percentage of providers ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count above 8 g/dL dropped from 60% to 25%.6

One difference maker, Dr. Shieh says, was providing education at the moment a doctor actually ordered blood. To avoid alert fatigue, the “smart BPA” fires only if a doctor tries to order blood and the patient’s hemoglobin is greater than 7 or 8 g/dL, depending on the diagnosis. If the doctor still wants to transfuse, the system requests a clinical indication for the exception.

Despite the clear improvement in appropriate use, the team wanted to understand why 25% of providers were still ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count greater than 8 despite the triggered BPA and whether additional interventions could yield further improvements. Through their study, the researchers documented several reasons for the continued ordering. In some cases, the system failed to properly document actual or potential bleeding as an indicator. In other cases, the ordering reflected a lack of consensus on the guidelines in fields like hematology and oncology.

One of the most intriguing reasons, though, was that residents often did the ordering at the behest of an attending who might have never seen the BPA.

“It’s not actually reaching the audience making the decision; it might be reaching the audience that’s just carrying out the order,” Dr. Shieh says.

The insight, she says, may provide an opportunity to talk with attending physicians who may not have completely bought into the guidelines and to involve the entire team in the decision-making process.

Hospitalists, she says, can play a vital role in guideline development and implementation, especially for strategies that include BPAs.

“I think they’re the perfect group to help use this technology wisely because they are at the front lines taking care of patients so they’ll know the best workflow of when these alerts fire and maybe which ones happen the most often,” Dr. Shieh says. “I think this is a fantastic opportunity to get more hospitalists involved in designing these alerts and collaborating with the IT folks.”

Even with widespread buy-in from providers, guidelines may not reach their full potential without a careful consideration of patients’ values and concerns. Experts say joint deliberations and discussions are especially important for guidelines that are complicated, controversial, or carrying potential risks that must be weighed against the benefits.

Some of the conversations are easy, with well-defined risks and benefits and clear patient preferences, but others must traverse vast tracts of gray area. Fortunately, Dr. Feldman says, more tools also are becoming available for this kind of shared decision making. Some use pictorial representations to help patients understand the potential outcomes of alternative courses of action or inaction.

“Sometimes, that pictorial representation is worth the 1,000 words that we wouldn’t be able to adequately describe otherwise,” he says.

Similarly, Cincinnati Children’s has developed tools to help to ease the shared decision-making process.

“We look where there’s equivocal evidence or no evidence and have developed tools that help the clinician have that conversation with the family and then have them informed enough that they can actually weigh in on what they want,” Gerhardt says. One end product is a card or trifold pamphlet that might help parents understand the benefits and side effects of alternate strategies.

“Typically, in medicine, we’re used to telling people what needs to be done,” she says. “So shared decision making is kind of a different thing for clinicians to engage in.” TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

- Valle CW, Binns HJ, Quadri-Sheriff M, Benuck I, Patel A. Physicians’ lack of adherence to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines for pediatric lipid screening. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(12):1200-1205.

- Maynard G, Jenkins IH, Merli GJ. Venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients: mind the (implementation) gap. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):582-588.

- Mehta RH, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Doing the right things and doing them the right way: association between hospital guideline adherence, dosing safety, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131(11):980-987.

- GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490

- Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726-735.

- 6. Chen JH, Fang DZ, Tim Goodnough L, Evans KH, Lee Porter M, Shieh L. Why providers transfuse blood products outside recommended guidelines in spite of integrated electronic best practice alerts. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):1-7.

One recent paper in Clinical Pediatrics, for example, chronicled low adherence to the 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute lipid screening guidelines in primary-care settings.1 Another cautioned providers to “mind the (implementation) gap” in venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients.2 A third found that lower adherence to guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for acute coronary syndrome patients was significantly associated with higher bleeding and mortality rates.3

Both clinical trials and real-world studies have demonstrated that when guidelines are applied, patients do better, says William Lewis, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and director of the Heart & Vascular Center at MetroHealth in Cleveland. So why aren’t they followed more consistently?

Experts in both HM and other disciplines cite multiple obstacles. Lack of evidence, conflicting evidence, or lack of awareness about evidence can all conspire against the main goal of helping providers deliver consistent high-value care, says Christopher Moriates, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“In our day-to-day lives as hospitalists, for the vast majority probably of what we do there’s no clear guideline or there’s a guideline that doesn’t necessarily apply to the patient standing in front of me,” he says.

Even when a guideline is clear and relevant, other doctors say inadequate dissemination and implementation can still derail quality improvement efforts.

“A lot of what we do as physicians is what we learned in residency, and to incorporate the new data is difficult,” says Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Feldman believes many doctors have yet to integrate recently revised hypertension and cholesterol guidelines into their practice, for example. Some guidelines have proven more complex or controversial, limiting their adoption.

“I know I struggle to keep up with all of the guidelines, and I’m in a big academic center where people are talking about them all the time, and I’m working with residents who are talking about them all the time,” Dr. Feldman says.

Despite the remaining gaps, however, many researchers agree that momentum has built steadily over the past two decades toward a more systematic approach to creating solid evidence-based guidelines and integrating them into real-world decision making.

Emphasis on Evidence and Transparency

The term “evidence-based medicine” was coined in 1990 by Gordon Guyatt, MD, MSc, FRCPC, distinguished professor of medicine and clinical epidemiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. It’s played an active role in formulating guidelines for multiple organizations. The guideline-writing process, Dr. Guyatt says, once consisted of little more than self-selected clinicians sitting around a table.

“It used to be that a bunch of experts got together and decided and made the recommendations with very little in the way of a systematic process and certainly not evidence based,” he says.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center was among the pioneers pushing for a more systematic approach; the hospital began working on its own guidelines in 1995 and published the first of many the following year.

“We started evidence-based guidelines when the docs were still saying, ‘This is cookbook medicine. I don’t know if I want to do this or not,’” says Wendy Gerhardt, MSN, director of evidence-based decision making in the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s.

Some doctors also argued that clinical guidelines would stifle innovation, cramp their individual style, or intrude on their relationships with patients. Despite some lingering misgivings among clinicians, however, the process has gained considerable support. In 2000, an organization called the GRADE Working Group (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) began developing a new approach to raise the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

The group’s work led to a 2004 article in BMJ, and the journal subsequently published a six-part series about GRADE for clinicians.4 More recently, the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology also delved into the issue with a 15-part series detailing the GRADE methodology.5 Together, Dr. Guyatt says, the articles have become a go-to guide for guidelines and have helped solidify the focus on evidence.

Cincinnati Children’s and other institutions also have developed tools, and the Institute of Medicine has published guideline-writing standards.

“So it’s easier than it’s ever been to know whether or not you have a decent guideline in your hand,” Gerhardt says.

Likewise, medical organizations are more clearly explaining how they came up with different kinds of guidelines. Evidence-based and consensus guidelines aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, though consensus building is often used in the absence of high-quality evidence. Some organizations have limited the pool of evidence for guidelines to randomized controlled trial data.

“Unfortunately, for us in the real world, we actually have to make decisions even when there’s not enough data,” Dr. Feldman says.

Sometimes, the best available evidence may be observational studies, and some committees still try to reach a consensus based on that evidence and on the panelists’ professional opinions.

Dr. Guyatt agrees that it’s “absolutely not” true that evidence-based guidelines require randomized controlled trials. “What you need for any recommendation is a thorough review and summary of the best available evidence,” he says.

As part of each final document, Cincinnati Children’s details how it created the guideline, when the literature searches occurred, how the committee reached a consensus, and which panelists participated in the deliberations. The information, Gerhardt says, allows anyone else to “make some sensible decisions about whether or not it’s a guideline you want to use.”

Guideline-crafting institutions are also focusing more on the proper makeup of their panels. In general, Dr. Guyatt says, a panel with more than 10 people can be unwieldy. Guidelines that include many specific recommendations, however, may require multiple subsections, each with its own committee.

Dr. Guyatt is careful to note that, like many other experts, he has multiple potential conflicts of interest, such as working on the anti-thrombotic guidelines issued by the American College of Chest Physicians. Committees, he says, have become increasingly aware of how properly handling conflicts (financial or otherwise) can be critical in building and maintaining trust among clinicians and patients. One technique is to ensure that a diversity of opinions is reflected among a committee whose experts have various conflicts. If one expert’s company makes drug A, for example, then the committee also includes experts involved with drugs B or C. As an alternative, some committees have explicitly barred anyone with a conflict of interest from participating at all.

But experts often provide crucial input, Dr. Guyatt says, and several committees have adopted variations of a middle-ground approach. In an approach that he favors, all guideline-formulating panelists are conflict-free but begin their work by meeting with a separate group of experts who may have some conflicts but can help point out the main issues. The panelists then deliberate and write a draft of the recommendations, after which they meet again with the experts to receive feedback before finalizing the draft.

In a related approach, experts sit on the panel and discuss the evidence, but those with conflicts recuse themselves before the group votes on any recommendations. Delineating between discussions of the evidence and discussions of recommendations can be tricky, though, increasing the risk that a conflict of interest may influence the outcome. Even so, Dr. Guyatt says the model is still preferable to other alternatives.

Getting the Word Out

Once guidelines have been crafted and vetted, how can hospitalists get up to speed on them? Dr. Feldman’s favorite go-to source is Guideline.gov, a national guideline clearinghouse that he calls one of the best compendiums of available information. Especially helpful, he adds, are details such as how the guidelines were created.

To help maximize his time, he also uses tools like NEJM Journal Watch, which sends daily emails on noteworthy articles and weekend roundups of the most important studies.

“It is a way of at least trying to keep up with what’s going on,” he says. Similarly, he adds, ACP Journal Club provides summaries of important new articles, The Hospitalist can help highlight important guidelines that affect HM, and CME meetings or online modules like SHMconsults.com can help doctors keep pace.

For the past decade, Dr. Guyatt has worked with another popular tool, a guideline-disseminating service called UpToDate. Many alternatives exist, such as DynaMed Plus.

“I think you just need to pick away,” Dr. Feldman says. “You need to decide that as a physician, as a lifelong learner, that you are going to do something that is going to keep you up-to-date. There are many ways of doing it. You just have to decide what you’re going to do and commit to it.”

Researchers are helping out by studying how to present new guidelines in ways that engage doctors and improve patient outcomes. Another trend is to make guidelines routinely accessible not only in electronic medical records but also on tablets and smartphones. Lisa Shieh, MD, PhD, FHM, a hospitalist and clinical professor of medicine at Stanford University Medical Center, has studied how best-practice alerts, or BPAs, impact adherence to guidelines covering the appropriate use of blood products. Dr. Shieh, who splits her time between quality improvement and hospital medicine, says getting new information and guidelines into clinicians’ hands can be a logistical challenge.

“At Stanford, we had a huge official campaign around the guidelines, and that did make some impact, but it wasn’t huge in improving appropriate blood use,” she says. When the medial center set up a BPA through the electronic medical record system, however, both overall and inappropriate blood use declined significantly. In fact, the percentage of providers ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count above 8 g/dL dropped from 60% to 25%.6

One difference maker, Dr. Shieh says, was providing education at the moment a doctor actually ordered blood. To avoid alert fatigue, the “smart BPA” fires only if a doctor tries to order blood and the patient’s hemoglobin is greater than 7 or 8 g/dL, depending on the diagnosis. If the doctor still wants to transfuse, the system requests a clinical indication for the exception.

Despite the clear improvement in appropriate use, the team wanted to understand why 25% of providers were still ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count greater than 8 despite the triggered BPA and whether additional interventions could yield further improvements. Through their study, the researchers documented several reasons for the continued ordering. In some cases, the system failed to properly document actual or potential bleeding as an indicator. In other cases, the ordering reflected a lack of consensus on the guidelines in fields like hematology and oncology.

One of the most intriguing reasons, though, was that residents often did the ordering at the behest of an attending who might have never seen the BPA.

“It’s not actually reaching the audience making the decision; it might be reaching the audience that’s just carrying out the order,” Dr. Shieh says.

The insight, she says, may provide an opportunity to talk with attending physicians who may not have completely bought into the guidelines and to involve the entire team in the decision-making process.

Hospitalists, she says, can play a vital role in guideline development and implementation, especially for strategies that include BPAs.

“I think they’re the perfect group to help use this technology wisely because they are at the front lines taking care of patients so they’ll know the best workflow of when these alerts fire and maybe which ones happen the most often,” Dr. Shieh says. “I think this is a fantastic opportunity to get more hospitalists involved in designing these alerts and collaborating with the IT folks.”

Even with widespread buy-in from providers, guidelines may not reach their full potential without a careful consideration of patients’ values and concerns. Experts say joint deliberations and discussions are especially important for guidelines that are complicated, controversial, or carrying potential risks that must be weighed against the benefits.

Some of the conversations are easy, with well-defined risks and benefits and clear patient preferences, but others must traverse vast tracts of gray area. Fortunately, Dr. Feldman says, more tools also are becoming available for this kind of shared decision making. Some use pictorial representations to help patients understand the potential outcomes of alternative courses of action or inaction.

“Sometimes, that pictorial representation is worth the 1,000 words that we wouldn’t be able to adequately describe otherwise,” he says.

Similarly, Cincinnati Children’s has developed tools to help to ease the shared decision-making process.

“We look where there’s equivocal evidence or no evidence and have developed tools that help the clinician have that conversation with the family and then have them informed enough that they can actually weigh in on what they want,” Gerhardt says. One end product is a card or trifold pamphlet that might help parents understand the benefits and side effects of alternate strategies.

“Typically, in medicine, we’re used to telling people what needs to be done,” she says. “So shared decision making is kind of a different thing for clinicians to engage in.” TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

- Valle CW, Binns HJ, Quadri-Sheriff M, Benuck I, Patel A. Physicians’ lack of adherence to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines for pediatric lipid screening. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(12):1200-1205.

- Maynard G, Jenkins IH, Merli GJ. Venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients: mind the (implementation) gap. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):582-588.

- Mehta RH, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Doing the right things and doing them the right way: association between hospital guideline adherence, dosing safety, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131(11):980-987.

- GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490

- Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726-735.

- 6. Chen JH, Fang DZ, Tim Goodnough L, Evans KH, Lee Porter M, Shieh L. Why providers transfuse blood products outside recommended guidelines in spite of integrated electronic best practice alerts. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):1-7.

A Quick Lesson on Bundled Payments

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has too many new payment models for a practicing doctor to keep up with them all. But there are three that I think are most important for hospitalists to know something about: hospital value-based purchasing, MACRA-related models, and bundled payments. Here, I’ll focus on the latter, which unlike the first two, influences payment to both hospitals and physicians (as well as other providers).

Bundles for Different Diagnoses

Bundled payment programs are the most visible of CMS’s episode payment models (EPMs). There are currently voluntary bundle models (called Bundled Payments for Care Improvement, or BPCI) across many different diagnoses. And in some locales, there is a mandatory bundle program for hip and knee replacements that began in March 2016 (called Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement, or CCJR or just CJR).

These programs are set to expand significantly in the next few years. The Surgical Hip and Femur Fracture Treatment (SHFFT) becomes active in 2017 in some locales. It will essentially add hip and femur fractures requiring surgery to the existing CJR program. New bundles for acute myocardial infarction, either managed medically or with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary bypass surgery will become mandatory in some parts of the country beginning July 2017.

How the Programs Work

CMS totals all Medicare dollars paid per patient historically for the relevant bundle. This includes payments to the hospital (e.g., the DRG payment) and all fees paid to physicians, therapists, visiting nurses, skilled nursing facilities, etc., from the time of hospital admission through 90 days after discharge. It then sets a target spend (or price) for that diagnosis that is about 3% below the historical average. Because it is based on the past track record of a hospital and its market (or region), the price will vary from place to place.

If, going forward, the Medicare spend for each patient is below the target, CMS pays that amount to the hospital. But if the spend is above the target, the hospital pays some or all of that amount to CMS. Presumably, hospitals will have negotiated with others, such as physicians, how such an “upside” or penalty payment will be divided between them.

It’s worth noting that all parties continue to bill, and are paid by Medicare, via the same fee-for-service arrangements currently in place. It is only at the time of a “true up” that an upside is paid or penalty assessed. And hospitals are eligible for upside payments only if they perform above a threshold on a few quality and patient satisfaction metrics.

The details of these programs are incredibly complicated, and I’m intentionally providing a very simple description of them here. I think that nearly all practicing clinicians should not try to learn and keep up with all of the precise details. They change often! Instead, it’s best to focus on the big picture only and rely on others at the hospital to keep track of the details.

Ways to Lower the Spend

These programs are intended to provide a significant financial incentive to find lower-cost ways to care for patients while still ensuring good care. Any successful effort to lower the cost should start by analyzing just what Medicare spends on each element of care over the more than 90 days each patient is in the bundle. For example, for hip and knee replacement patients, nearly half of the spend goes toward post-hospital services such as a skilled nursing facility and home nursing visits. So the best opportunity to reduce the spend may be to reduce utilization of these services where appropriate.

For patients in the bundles for coronary artery bypass grafting and acute myocardial infarction treated with PCI, only about 10% of the total spend goes to post-hospital services. For these, it might be more effective to focus cost reductions on other things.

Each organization will need to make its own decisions regarding where to focus cost-reduction efforts across the bundle. For many of us, that will mean moving away from a focus on traditional hospitalist-related cost-containment efforts like length of stay or pharmacy costs and instead looking at the bigger picture, including use of post-hospital services.

Some Things to Watch

I expect there will be a number of side effects of these payment models that hospitalists will care about. Doctors in different specialties, for example, might change their minds about whether they want to serve as attending physicians for “bundle patients.” One scenario is that if orthopedists have an opportunity to realize a significant financial upside, they may prefer to serve as attendings for hip fracture patients rather than leaving to hospitalists financially important decisions such as whether patients are discharged to a skilled nursing facility or home. We’ll just have to see how that plays out and be prepared to advocate for our position if different from other specialties.

Successful performance in bundles requires effective coordination of care across settings, and I’m hopeful this will benefit patients. Hospitals and skilled nursing facilities, for example, will need to work together more effectively to curb unnecessary days in the facilities and to reduce readmissions. Many hospitals have already begun developing a preferred network of skilled nursing facilities for referrals that is based on demonstrating good care and low returns to the hospital. Your hospital has probably already started doing this work even if you haven’t heard about it yet.

For me, one of the most concerning outcomes of bundles is the negotiations between providers regarding how an upside or penalty is to be shared among them. I suspect this won’t be contentious initially, but as the dollars at stake grow, it could lead to increasingly stressful negotiations and relationships.

And, lastly, like any payment model, bundles are “gameable,” especially bundles for medical diagnoses such as congestive heart failure or pneumonia, which can be gamed by lowering the threshold for admitting less-sick patients to inpatient status. The spend for these patients, who are less likely to require expensive post-hospital services or be readmitted, will lower the average spend in the bundle, increasing the chance of an upside payment for the providers. TH

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has too many new payment models for a practicing doctor to keep up with them all. But there are three that I think are most important for hospitalists to know something about: hospital value-based purchasing, MACRA-related models, and bundled payments. Here, I’ll focus on the latter, which unlike the first two, influences payment to both hospitals and physicians (as well as other providers).

Bundles for Different Diagnoses

Bundled payment programs are the most visible of CMS’s episode payment models (EPMs). There are currently voluntary bundle models (called Bundled Payments for Care Improvement, or BPCI) across many different diagnoses. And in some locales, there is a mandatory bundle program for hip and knee replacements that began in March 2016 (called Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement, or CCJR or just CJR).

These programs are set to expand significantly in the next few years. The Surgical Hip and Femur Fracture Treatment (SHFFT) becomes active in 2017 in some locales. It will essentially add hip and femur fractures requiring surgery to the existing CJR program. New bundles for acute myocardial infarction, either managed medically or with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary bypass surgery will become mandatory in some parts of the country beginning July 2017.

How the Programs Work

CMS totals all Medicare dollars paid per patient historically for the relevant bundle. This includes payments to the hospital (e.g., the DRG payment) and all fees paid to physicians, therapists, visiting nurses, skilled nursing facilities, etc., from the time of hospital admission through 90 days after discharge. It then sets a target spend (or price) for that diagnosis that is about 3% below the historical average. Because it is based on the past track record of a hospital and its market (or region), the price will vary from place to place.

If, going forward, the Medicare spend for each patient is below the target, CMS pays that amount to the hospital. But if the spend is above the target, the hospital pays some or all of that amount to CMS. Presumably, hospitals will have negotiated with others, such as physicians, how such an “upside” or penalty payment will be divided between them.

It’s worth noting that all parties continue to bill, and are paid by Medicare, via the same fee-for-service arrangements currently in place. It is only at the time of a “true up” that an upside is paid or penalty assessed. And hospitals are eligible for upside payments only if they perform above a threshold on a few quality and patient satisfaction metrics.

The details of these programs are incredibly complicated, and I’m intentionally providing a very simple description of them here. I think that nearly all practicing clinicians should not try to learn and keep up with all of the precise details. They change often! Instead, it’s best to focus on the big picture only and rely on others at the hospital to keep track of the details.

Ways to Lower the Spend

These programs are intended to provide a significant financial incentive to find lower-cost ways to care for patients while still ensuring good care. Any successful effort to lower the cost should start by analyzing just what Medicare spends on each element of care over the more than 90 days each patient is in the bundle. For example, for hip and knee replacement patients, nearly half of the spend goes toward post-hospital services such as a skilled nursing facility and home nursing visits. So the best opportunity to reduce the spend may be to reduce utilization of these services where appropriate.

For patients in the bundles for coronary artery bypass grafting and acute myocardial infarction treated with PCI, only about 10% of the total spend goes to post-hospital services. For these, it might be more effective to focus cost reductions on other things.

Each organization will need to make its own decisions regarding where to focus cost-reduction efforts across the bundle. For many of us, that will mean moving away from a focus on traditional hospitalist-related cost-containment efforts like length of stay or pharmacy costs and instead looking at the bigger picture, including use of post-hospital services.

Some Things to Watch

I expect there will be a number of side effects of these payment models that hospitalists will care about. Doctors in different specialties, for example, might change their minds about whether they want to serve as attending physicians for “bundle patients.” One scenario is that if orthopedists have an opportunity to realize a significant financial upside, they may prefer to serve as attendings for hip fracture patients rather than leaving to hospitalists financially important decisions such as whether patients are discharged to a skilled nursing facility or home. We’ll just have to see how that plays out and be prepared to advocate for our position if different from other specialties.

Successful performance in bundles requires effective coordination of care across settings, and I’m hopeful this will benefit patients. Hospitals and skilled nursing facilities, for example, will need to work together more effectively to curb unnecessary days in the facilities and to reduce readmissions. Many hospitals have already begun developing a preferred network of skilled nursing facilities for referrals that is based on demonstrating good care and low returns to the hospital. Your hospital has probably already started doing this work even if you haven’t heard about it yet.

For me, one of the most concerning outcomes of bundles is the negotiations between providers regarding how an upside or penalty is to be shared among them. I suspect this won’t be contentious initially, but as the dollars at stake grow, it could lead to increasingly stressful negotiations and relationships.

And, lastly, like any payment model, bundles are “gameable,” especially bundles for medical diagnoses such as congestive heart failure or pneumonia, which can be gamed by lowering the threshold for admitting less-sick patients to inpatient status. The spend for these patients, who are less likely to require expensive post-hospital services or be readmitted, will lower the average spend in the bundle, increasing the chance of an upside payment for the providers. TH

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has too many new payment models for a practicing doctor to keep up with them all. But there are three that I think are most important for hospitalists to know something about: hospital value-based purchasing, MACRA-related models, and bundled payments. Here, I’ll focus on the latter, which unlike the first two, influences payment to both hospitals and physicians (as well as other providers).

Bundles for Different Diagnoses

Bundled payment programs are the most visible of CMS’s episode payment models (EPMs). There are currently voluntary bundle models (called Bundled Payments for Care Improvement, or BPCI) across many different diagnoses. And in some locales, there is a mandatory bundle program for hip and knee replacements that began in March 2016 (called Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement, or CCJR or just CJR).

These programs are set to expand significantly in the next few years. The Surgical Hip and Femur Fracture Treatment (SHFFT) becomes active in 2017 in some locales. It will essentially add hip and femur fractures requiring surgery to the existing CJR program. New bundles for acute myocardial infarction, either managed medically or with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary bypass surgery will become mandatory in some parts of the country beginning July 2017.

How the Programs Work

CMS totals all Medicare dollars paid per patient historically for the relevant bundle. This includes payments to the hospital (e.g., the DRG payment) and all fees paid to physicians, therapists, visiting nurses, skilled nursing facilities, etc., from the time of hospital admission through 90 days after discharge. It then sets a target spend (or price) for that diagnosis that is about 3% below the historical average. Because it is based on the past track record of a hospital and its market (or region), the price will vary from place to place.

If, going forward, the Medicare spend for each patient is below the target, CMS pays that amount to the hospital. But if the spend is above the target, the hospital pays some or all of that amount to CMS. Presumably, hospitals will have negotiated with others, such as physicians, how such an “upside” or penalty payment will be divided between them.

It’s worth noting that all parties continue to bill, and are paid by Medicare, via the same fee-for-service arrangements currently in place. It is only at the time of a “true up” that an upside is paid or penalty assessed. And hospitals are eligible for upside payments only if they perform above a threshold on a few quality and patient satisfaction metrics.

The details of these programs are incredibly complicated, and I’m intentionally providing a very simple description of them here. I think that nearly all practicing clinicians should not try to learn and keep up with all of the precise details. They change often! Instead, it’s best to focus on the big picture only and rely on others at the hospital to keep track of the details.

Ways to Lower the Spend

These programs are intended to provide a significant financial incentive to find lower-cost ways to care for patients while still ensuring good care. Any successful effort to lower the cost should start by analyzing just what Medicare spends on each element of care over the more than 90 days each patient is in the bundle. For example, for hip and knee replacement patients, nearly half of the spend goes toward post-hospital services such as a skilled nursing facility and home nursing visits. So the best opportunity to reduce the spend may be to reduce utilization of these services where appropriate.

For patients in the bundles for coronary artery bypass grafting and acute myocardial infarction treated with PCI, only about 10% of the total spend goes to post-hospital services. For these, it might be more effective to focus cost reductions on other things.

Each organization will need to make its own decisions regarding where to focus cost-reduction efforts across the bundle. For many of us, that will mean moving away from a focus on traditional hospitalist-related cost-containment efforts like length of stay or pharmacy costs and instead looking at the bigger picture, including use of post-hospital services.

Some Things to Watch

I expect there will be a number of side effects of these payment models that hospitalists will care about. Doctors in different specialties, for example, might change their minds about whether they want to serve as attending physicians for “bundle patients.” One scenario is that if orthopedists have an opportunity to realize a significant financial upside, they may prefer to serve as attendings for hip fracture patients rather than leaving to hospitalists financially important decisions such as whether patients are discharged to a skilled nursing facility or home. We’ll just have to see how that plays out and be prepared to advocate for our position if different from other specialties.

Successful performance in bundles requires effective coordination of care across settings, and I’m hopeful this will benefit patients. Hospitals and skilled nursing facilities, for example, will need to work together more effectively to curb unnecessary days in the facilities and to reduce readmissions. Many hospitals have already begun developing a preferred network of skilled nursing facilities for referrals that is based on demonstrating good care and low returns to the hospital. Your hospital has probably already started doing this work even if you haven’t heard about it yet.

For me, one of the most concerning outcomes of bundles is the negotiations between providers regarding how an upside or penalty is to be shared among them. I suspect this won’t be contentious initially, but as the dollars at stake grow, it could lead to increasingly stressful negotiations and relationships.

And, lastly, like any payment model, bundles are “gameable,” especially bundles for medical diagnoses such as congestive heart failure or pneumonia, which can be gamed by lowering the threshold for admitting less-sick patients to inpatient status. The spend for these patients, who are less likely to require expensive post-hospital services or be readmitted, will lower the average spend in the bundle, increasing the chance of an upside payment for the providers. TH

What to Know about CMS’s New Emergency Preparedness Requirements

Are you ready?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released new emergency preparedness requirements to ensure that providers and suppliers are duly prepared to adequately serve their community during disasters or emergencies. These requirements were stimulated by unexpected and catastrophic events, such as the September 11 terrorist attacks, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and innumerable natural disasters (tornados, floods, and hurricanes, to name a few). The CMS final rule issued “requirements that establish a comprehensive, consistent, flexible, and dynamic regulatory approach to emergency preparedness and response that incorporates the lessons learned from the past, combined with the proven best practices of the present.” In the rule, CMS outlines three essential guiding principles that any healthcare facility or supplier would need to preserve in the event of a disaster:

- Safeguard human resources.

- Maintain business continuity.

- Protect physical resources.

4 Ways to Be Prepared

What does having a comprehensive disaster preparedness program mean for hospitalists, regardless of site of practice? CMS recommends having four key elements for an adequate program:

1. Perform a risk assessment that focuses on the capacities and capabilities that are critical for a full spectrum of types of emergencies or disasters. This risk assessment should take into consideration the type and location of the facility as well as the disasters that are most likely to occur in its area. It should include at a minimum “care-related emergencies; equipment and power failures; interruptions in communications, including cyber attacks; loss of a portion or all of a facility; and interruptions in the normal supply of essentials, such as water and food.”

2. Develop and implement policies and procedures that support the emergency plan. Hospitalists should know about organizational policies and procedures that support the implementation of the emergency plan and how their team is factored into that plan.

3. Develop and maintain a communication plan that also complies with state and federal law. All the preparations in the world can be crippled without a robust and clear communication plan. The facility must have primary and backup mechanisms to contact providers, staff, and personnel in a timely fashion; this should include mechanisms to repeatedly update providers as the event evolves so that everyone knows what they are supposed to be doing and when.

4. Develop and maintain a training and testing program for all personnel. This includes onboarding and annual refreshers, including drills and exercises that test the plan and identify any gaps in performance. Hospitalists will undoubtedly be key members in developing, implementing, and receiving such critical training.

Expectations

There isn’t a single U.S. healthcare facility or provider that will not be affected by these provisions. An estimated 72,000 healthcare providers and suppliers (from nursing homes to dialysis facilities to home health agencies) will be expected to comply with these requirements within about a year.

In addition to hospitals, CMS also extended the requirements to many types of facilities and suppliers so that such providers can more likely stay open and provide care during disasters and emergencies, or at least can resume operations as soon as possible, to provide the very best ongoing care to the affected community. In most of these scenarios, the need for complex and varied care goes up, not down, further exacerbating gaps in basic care if ambulatory facilities and home care providers are unavailable.

CMS does acknowledge that these requirements will be more difficult to execute in facilities that previously did not have requirements or in smaller facilities with more limited resources. It also acknowledges that the cost of implementation could reach up to $279 million, which some argue is actually an underestimation. Despite these challenges, it is hard to argue against basic disaster preparedness for any healthcare facility or provider as a standard and positive business practice. While most acute-care hospitals have long had disaster preparedness plans and programs, gaps in these programs have become readily apparent during natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy. CMS also stresses the need for a community approach to planning and implementation and that there is no reason during planning, or during an actual event, that facilities should operate in isolation but rather train and respond together as a community.

As hospitalists, regardless of site of practice, we should all be involved in at least understanding, if not developing and implementing, these basic requirements in our facilities. It is without a doubt that hospitalists will be a core group of physicians who will be called upon to serve within or outside healthcare facilities in the event of a disaster or emergency. In fact, in most recent disasters, we already have. It is better, of course, to be prepared and ready to serve than unprepared and regretful.

Reference

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Emergency Preparedness Requirements for Medicare and Medicaid Participating Providers and Suppliers. Federal Register website. Accessed October 6, 2016.

Are you ready?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released new emergency preparedness requirements to ensure that providers and suppliers are duly prepared to adequately serve their community during disasters or emergencies. These requirements were stimulated by unexpected and catastrophic events, such as the September 11 terrorist attacks, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and innumerable natural disasters (tornados, floods, and hurricanes, to name a few). The CMS final rule issued “requirements that establish a comprehensive, consistent, flexible, and dynamic regulatory approach to emergency preparedness and response that incorporates the lessons learned from the past, combined with the proven best practices of the present.” In the rule, CMS outlines three essential guiding principles that any healthcare facility or supplier would need to preserve in the event of a disaster:

- Safeguard human resources.

- Maintain business continuity.

- Protect physical resources.

4 Ways to Be Prepared

What does having a comprehensive disaster preparedness program mean for hospitalists, regardless of site of practice? CMS recommends having four key elements for an adequate program:

1. Perform a risk assessment that focuses on the capacities and capabilities that are critical for a full spectrum of types of emergencies or disasters. This risk assessment should take into consideration the type and location of the facility as well as the disasters that are most likely to occur in its area. It should include at a minimum “care-related emergencies; equipment and power failures; interruptions in communications, including cyber attacks; loss of a portion or all of a facility; and interruptions in the normal supply of essentials, such as water and food.”

2. Develop and implement policies and procedures that support the emergency plan. Hospitalists should know about organizational policies and procedures that support the implementation of the emergency plan and how their team is factored into that plan.

3. Develop and maintain a communication plan that also complies with state and federal law. All the preparations in the world can be crippled without a robust and clear communication plan. The facility must have primary and backup mechanisms to contact providers, staff, and personnel in a timely fashion; this should include mechanisms to repeatedly update providers as the event evolves so that everyone knows what they are supposed to be doing and when.

4. Develop and maintain a training and testing program for all personnel. This includes onboarding and annual refreshers, including drills and exercises that test the plan and identify any gaps in performance. Hospitalists will undoubtedly be key members in developing, implementing, and receiving such critical training.

Expectations

There isn’t a single U.S. healthcare facility or provider that will not be affected by these provisions. An estimated 72,000 healthcare providers and suppliers (from nursing homes to dialysis facilities to home health agencies) will be expected to comply with these requirements within about a year.

In addition to hospitals, CMS also extended the requirements to many types of facilities and suppliers so that such providers can more likely stay open and provide care during disasters and emergencies, or at least can resume operations as soon as possible, to provide the very best ongoing care to the affected community. In most of these scenarios, the need for complex and varied care goes up, not down, further exacerbating gaps in basic care if ambulatory facilities and home care providers are unavailable.

CMS does acknowledge that these requirements will be more difficult to execute in facilities that previously did not have requirements or in smaller facilities with more limited resources. It also acknowledges that the cost of implementation could reach up to $279 million, which some argue is actually an underestimation. Despite these challenges, it is hard to argue against basic disaster preparedness for any healthcare facility or provider as a standard and positive business practice. While most acute-care hospitals have long had disaster preparedness plans and programs, gaps in these programs have become readily apparent during natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy. CMS also stresses the need for a community approach to planning and implementation and that there is no reason during planning, or during an actual event, that facilities should operate in isolation but rather train and respond together as a community.

As hospitalists, regardless of site of practice, we should all be involved in at least understanding, if not developing and implementing, these basic requirements in our facilities. It is without a doubt that hospitalists will be a core group of physicians who will be called upon to serve within or outside healthcare facilities in the event of a disaster or emergency. In fact, in most recent disasters, we already have. It is better, of course, to be prepared and ready to serve than unprepared and regretful.

Reference

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Emergency Preparedness Requirements for Medicare and Medicaid Participating Providers and Suppliers. Federal Register website. Accessed October 6, 2016.

Are you ready?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released new emergency preparedness requirements to ensure that providers and suppliers are duly prepared to adequately serve their community during disasters or emergencies. These requirements were stimulated by unexpected and catastrophic events, such as the September 11 terrorist attacks, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and innumerable natural disasters (tornados, floods, and hurricanes, to name a few). The CMS final rule issued “requirements that establish a comprehensive, consistent, flexible, and dynamic regulatory approach to emergency preparedness and response that incorporates the lessons learned from the past, combined with the proven best practices of the present.” In the rule, CMS outlines three essential guiding principles that any healthcare facility or supplier would need to preserve in the event of a disaster:

- Safeguard human resources.

- Maintain business continuity.

- Protect physical resources.

4 Ways to Be Prepared

What does having a comprehensive disaster preparedness program mean for hospitalists, regardless of site of practice? CMS recommends having four key elements for an adequate program:

1. Perform a risk assessment that focuses on the capacities and capabilities that are critical for a full spectrum of types of emergencies or disasters. This risk assessment should take into consideration the type and location of the facility as well as the disasters that are most likely to occur in its area. It should include at a minimum “care-related emergencies; equipment and power failures; interruptions in communications, including cyber attacks; loss of a portion or all of a facility; and interruptions in the normal supply of essentials, such as water and food.”

2. Develop and implement policies and procedures that support the emergency plan. Hospitalists should know about organizational policies and procedures that support the implementation of the emergency plan and how their team is factored into that plan.