User login

More cuts to physician payment ahead

In July, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the 2024 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) proposed rule on proposed policy changes for Medicare payments. The proposed rule contains 2,883 pages of proposals for physician, hospital outpatient department, and ambulatory surgery center (ASC) payments for calendar year 2024. For gastroenterologists, there was good news and bad news.

Medicare physician payments have been cut each year for the better part of a decade, with additional cuts proposed for 2024.

According to the American Medical Assocition, Medicare physician payment has already declined 26% in the last 22 years when adjusting for inflation, and that’s before factoring in the proposed cuts for 2024. Physicians are one of the only health care providers without an automatic inflationary increase, the AMA reports.

AGA opposes additional cuts to physician payments and will continue to advocate to stop them. AGA and many other specialty societies support H.R. 2474, the Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act. This bill would provide a permanent, annual update equal to the increase in the Medicare Economic Index, which is how the government measures inflation in medical practice. We will continue to advocate for permanent positive annual inflation updates, which would allow physicians to invest in their practices and implement new strategies to provide high-value care.

But in some positive news from the 2024 Medicare PFS, the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and the ASC proposed rules include increased hospital outpatient departments and ASC payments, continued telemedicine reimbursement and coverage through 2024, and a second one-year delay in changes to rules governing split/shared visits. Specifically:

OPPS Conversion Factor: The proposed CY 2024 Medicare conversion factor for outpatient hospital departments is $87.488, an increase of 2.8%, for hospitals that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

ASC Conversion Factor: The proposed CY 2024 Ambulatory Surgical Center conversion factor is $53.397, an increase of 2.8%, for ASCs that meet applicable quality reporting requirements. The AGA and our sister societies continue to urge CMS to reduce this gap in the ASC facility fees, when compared to the outpatient hospital facility rates, which are estimated to be a roughly 48% differential in CY 2024.

Telehealth: CMS proposes to continue reimbursing telehealth services at current levels through 2024. Payment for audio-only evaluation and management (E/M) codes will continue at parity with follow-up in-person visits as it has throughout the pandemic. Additionally, CMS is implementing telehealth flexibilities that were included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2023 by allowing telehealth visits to originate at any site in the United States. This will allow patients throughout the country to maintain access to needed telehealth services without facing the logistical and safety challenges that can surround in-person visits. CMS is proposing to pay telehealth services at the nonfacility payment rate, which is the same rate as in-person office visits, lift the frequency limits on telehealth visits for subsequent hospital and skilled nursing facility visits, and allow direct supervision to be provided virtually.

Split (or shared) visits: CMS has proposed a second one-year delay to its proposed split/shared visits policy. The original proposal required that the billing provider in split/shared visits be whoever spent more than half of the total time with the patient (making time the only way to define substantive portion). CMS plans to delay that through at least Dec. 31, 2024. In the interim, practices can continue to use one of the three key components (history, exam, or medical decision-making) or more than half of the total time spent to determine who can bill for the visit. The GI societies will continue to advocate for appropriate reimbursement to align with new team-based models of care delivery.

Notably, the split (or shared) visits policy was also delayed in 2023 because of widespread concerns and feedback that the policy would disrupt team-based care and care delivery in the hospital setting. The American Medical Association CPT editorial panel, the body responsible for creating and maintaining CPT codes, has approved revisions to E/M guidelines that may help address some of CMS’s concerns.

For more information on issues affecting gastroenterologists in the 2024 Medicare PFS and OPPS/ASC proposed rules, visit the AGA news website.

Dr. Garcia serves as an advisor to the AGA AMA Relative-value Update Committee. She is clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is director of the neurogastroenterology and motility laboratory in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, and associate chief medical information officer in ambulatory care at Stanford Health Care.

In July, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the 2024 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) proposed rule on proposed policy changes for Medicare payments. The proposed rule contains 2,883 pages of proposals for physician, hospital outpatient department, and ambulatory surgery center (ASC) payments for calendar year 2024. For gastroenterologists, there was good news and bad news.

Medicare physician payments have been cut each year for the better part of a decade, with additional cuts proposed for 2024.

According to the American Medical Assocition, Medicare physician payment has already declined 26% in the last 22 years when adjusting for inflation, and that’s before factoring in the proposed cuts for 2024. Physicians are one of the only health care providers without an automatic inflationary increase, the AMA reports.

AGA opposes additional cuts to physician payments and will continue to advocate to stop them. AGA and many other specialty societies support H.R. 2474, the Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act. This bill would provide a permanent, annual update equal to the increase in the Medicare Economic Index, which is how the government measures inflation in medical practice. We will continue to advocate for permanent positive annual inflation updates, which would allow physicians to invest in their practices and implement new strategies to provide high-value care.

But in some positive news from the 2024 Medicare PFS, the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and the ASC proposed rules include increased hospital outpatient departments and ASC payments, continued telemedicine reimbursement and coverage through 2024, and a second one-year delay in changes to rules governing split/shared visits. Specifically:

OPPS Conversion Factor: The proposed CY 2024 Medicare conversion factor for outpatient hospital departments is $87.488, an increase of 2.8%, for hospitals that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

ASC Conversion Factor: The proposed CY 2024 Ambulatory Surgical Center conversion factor is $53.397, an increase of 2.8%, for ASCs that meet applicable quality reporting requirements. The AGA and our sister societies continue to urge CMS to reduce this gap in the ASC facility fees, when compared to the outpatient hospital facility rates, which are estimated to be a roughly 48% differential in CY 2024.

Telehealth: CMS proposes to continue reimbursing telehealth services at current levels through 2024. Payment for audio-only evaluation and management (E/M) codes will continue at parity with follow-up in-person visits as it has throughout the pandemic. Additionally, CMS is implementing telehealth flexibilities that were included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2023 by allowing telehealth visits to originate at any site in the United States. This will allow patients throughout the country to maintain access to needed telehealth services without facing the logistical and safety challenges that can surround in-person visits. CMS is proposing to pay telehealth services at the nonfacility payment rate, which is the same rate as in-person office visits, lift the frequency limits on telehealth visits for subsequent hospital and skilled nursing facility visits, and allow direct supervision to be provided virtually.

Split (or shared) visits: CMS has proposed a second one-year delay to its proposed split/shared visits policy. The original proposal required that the billing provider in split/shared visits be whoever spent more than half of the total time with the patient (making time the only way to define substantive portion). CMS plans to delay that through at least Dec. 31, 2024. In the interim, practices can continue to use one of the three key components (history, exam, or medical decision-making) or more than half of the total time spent to determine who can bill for the visit. The GI societies will continue to advocate for appropriate reimbursement to align with new team-based models of care delivery.

Notably, the split (or shared) visits policy was also delayed in 2023 because of widespread concerns and feedback that the policy would disrupt team-based care and care delivery in the hospital setting. The American Medical Association CPT editorial panel, the body responsible for creating and maintaining CPT codes, has approved revisions to E/M guidelines that may help address some of CMS’s concerns.

For more information on issues affecting gastroenterologists in the 2024 Medicare PFS and OPPS/ASC proposed rules, visit the AGA news website.

Dr. Garcia serves as an advisor to the AGA AMA Relative-value Update Committee. She is clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is director of the neurogastroenterology and motility laboratory in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, and associate chief medical information officer in ambulatory care at Stanford Health Care.

In July, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the 2024 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) proposed rule on proposed policy changes for Medicare payments. The proposed rule contains 2,883 pages of proposals for physician, hospital outpatient department, and ambulatory surgery center (ASC) payments for calendar year 2024. For gastroenterologists, there was good news and bad news.

Medicare physician payments have been cut each year for the better part of a decade, with additional cuts proposed for 2024.

According to the American Medical Assocition, Medicare physician payment has already declined 26% in the last 22 years when adjusting for inflation, and that’s before factoring in the proposed cuts for 2024. Physicians are one of the only health care providers without an automatic inflationary increase, the AMA reports.

AGA opposes additional cuts to physician payments and will continue to advocate to stop them. AGA and many other specialty societies support H.R. 2474, the Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act. This bill would provide a permanent, annual update equal to the increase in the Medicare Economic Index, which is how the government measures inflation in medical practice. We will continue to advocate for permanent positive annual inflation updates, which would allow physicians to invest in their practices and implement new strategies to provide high-value care.

But in some positive news from the 2024 Medicare PFS, the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and the ASC proposed rules include increased hospital outpatient departments and ASC payments, continued telemedicine reimbursement and coverage through 2024, and a second one-year delay in changes to rules governing split/shared visits. Specifically:

OPPS Conversion Factor: The proposed CY 2024 Medicare conversion factor for outpatient hospital departments is $87.488, an increase of 2.8%, for hospitals that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

ASC Conversion Factor: The proposed CY 2024 Ambulatory Surgical Center conversion factor is $53.397, an increase of 2.8%, for ASCs that meet applicable quality reporting requirements. The AGA and our sister societies continue to urge CMS to reduce this gap in the ASC facility fees, when compared to the outpatient hospital facility rates, which are estimated to be a roughly 48% differential in CY 2024.

Telehealth: CMS proposes to continue reimbursing telehealth services at current levels through 2024. Payment for audio-only evaluation and management (E/M) codes will continue at parity with follow-up in-person visits as it has throughout the pandemic. Additionally, CMS is implementing telehealth flexibilities that were included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2023 by allowing telehealth visits to originate at any site in the United States. This will allow patients throughout the country to maintain access to needed telehealth services without facing the logistical and safety challenges that can surround in-person visits. CMS is proposing to pay telehealth services at the nonfacility payment rate, which is the same rate as in-person office visits, lift the frequency limits on telehealth visits for subsequent hospital and skilled nursing facility visits, and allow direct supervision to be provided virtually.

Split (or shared) visits: CMS has proposed a second one-year delay to its proposed split/shared visits policy. The original proposal required that the billing provider in split/shared visits be whoever spent more than half of the total time with the patient (making time the only way to define substantive portion). CMS plans to delay that through at least Dec. 31, 2024. In the interim, practices can continue to use one of the three key components (history, exam, or medical decision-making) or more than half of the total time spent to determine who can bill for the visit. The GI societies will continue to advocate for appropriate reimbursement to align with new team-based models of care delivery.

Notably, the split (or shared) visits policy was also delayed in 2023 because of widespread concerns and feedback that the policy would disrupt team-based care and care delivery in the hospital setting. The American Medical Association CPT editorial panel, the body responsible for creating and maintaining CPT codes, has approved revisions to E/M guidelines that may help address some of CMS’s concerns.

For more information on issues affecting gastroenterologists in the 2024 Medicare PFS and OPPS/ASC proposed rules, visit the AGA news website.

Dr. Garcia serves as an advisor to the AGA AMA Relative-value Update Committee. She is clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is director of the neurogastroenterology and motility laboratory in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, and associate chief medical information officer in ambulatory care at Stanford Health Care.

The 2021 proposed Medicare fee schedule: Can the payment cuts be avoided?

Payment cuts to nearly all of medicine, including gastroenterology, could be in store beginning Jan. 1, 2021. Physicians may also face elimination of some services the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services granted temporary access to during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic according to CMS’s recently released policy and payment recommendations. These proposals could be implemented as physician practices are still recovering financially from states’ temporary ban on elective surgeries from March through May 2020 in response to the public health emergency (PHE) and continuing to deal with the clinical and financial challenges of the pandemic.

In early August, CMS proposed a number of changes for 2021 that affect physicians. There’s plenty of good, bad, and ugly in this proposed rule.

Let’s start with two positives (The good):

Medicare proposes to maintain the current values for colonoscopy with biopsy (45385) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy (43239). Despite a recent reevaluation of these codes in 2016 and 2014, respectively, Medicare conceded to Anthem’s suggestion that the procedures were not overvalued and needed another evaluation. The AGA and our sister societies’ data affirmed the current values and Medicare proposed to maintain them in 2021.

Medicare proposes to increase the price for scope video system equipment (ES031) from $36,306 to $70,673.38 and the suction machine (Gomco) (EQ235) from $1,981.66 to $3,195.85, phased in over 2 years. This will provide a small increase in the practice expense value for all GI endoscopy procedures. Since CMS began conducting a review of scope systems in 2017, the AGA and our sister societies have successfully worked to convince the Agency to increase its payment for GI endoscopes and associated equipment by providing invoices. We are pleased Medicare is updating these items to reflect more accurate costs.

Now onto items that could negatively affect the practice of gastroenterology.

The bad

Medicare proposes to stop covering and paying for telephone evaluation and management (E/M) visits as soon as the COVID-19 PHE expires. After originally denying that Medicare beneficiaries had trouble accessing video E/M visits and refusing to cover existing telephone (audio only) E/M codes 99441-99443, the agency responded to enormous pressure from AGA and other specialties and added the codes to its covered telehealth services list, setting the payment equal to office/outpatient established patient E/M codes 99212-99214 during the PHE. Telephone E/M has been a vital lifeline, allowing Medicare beneficiaries who don’t have a smart phone or reliable internet connection to access needed E/M services, while allowing them to stay safe at home during the PHE. There is evidence that our most vulnerable patients have the greatest need for telephone visits to advance their care.1

Medicare’s proposal to stop covering and paying for telephone E/M visits as soon as the COVID-19 PHE expires, while disappointing, is not surprising because of the agency’s reluctance to admit they were needed in the first place. The agency believes that creating a new code for audio-only patient interactions similar to the virtual check-in code G2012 but for a longer unit of time and with an accordingly higher value will suffice. Physicians appreciate that E/M delivered via telephone is not the same as a check-in call to a patient, and the care provided requires similar time, effort, and cognitive load as video visits. The AGA and our sister societies plan to object to Medicare’s proposal to treat these services as “check-ins” with slightly higher payment and will continue to advocate for permanent coverage of the telephone E/M CPT codes and payment parity with in-person E/M visits.

The ugly

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) conversion factor, the basis of Medicare payments, is proposed to be cut almost 11% percent from $36.09 in 2020 to $32.26 in 2021.

How it happened

Medicare agreed to implement coding and valuation changes to office and outpatient E/M codes (99202-99205, 99211-99215) in 2021 as recommended by the American Medical Association and widely supported by specialty societies. E/M services account for about 40% of all Medicare spending annually, which magnifies the impact of any changes to their relative value units (RVUs). By law, payment increases that occur from new work RVUs must be offset by a reduction, referred to as a budget-neutral adjustment, applied to offset the increase in total spending on the MPFS.2

CMS explained in the 2021 MPFS proposed rule, “If revisions to the RVUs cause expenditures for the year to change by more than $20 million, we make adjustments to ensure that expenditures do not increase or decrease by more than $20 million.” Medicare calculated that the corresponding adjustment to the conversion factor for 2021 needed to fall by nearly 11% to achieve budget neutrality. Because gastroenterologists report a significant portion of E/M in addition to performing procedures, the overall estimated impact is –5% of all reimbursement from Medicare.

What you can do

Visit the AGA Advocacy Action Center at https://gastro.quorum.us/AGAactioncenter/ and select “Fight back against CMS’s cuts to specialty care payments” to tell your lawmakers to stop these cuts and preserve care for patients by waiving Medicare’s budget neutrality requirements for E/M adjustments.

You can also use the AGA’s Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Calculator tool to determine the effect of the proposed cuts.3 By contacting AGA staff, Leslie Narramore, at [email protected] with the overall effect on your practice, you can help AGA use these data as we work with the physician community to urge Congress to prevent these payment cuts.

What AGA is doing

The AGA and our sister societies have joined the AMA and others in urging Congress and CMS to waive budget-neutrality rules for the implementation of the changes in E/M services effective 2021. We also joined with AMA and over 100 specialty societies in a letter asking Secretary of Health & Human Services Alex Azar that the agency use its authority under the public health emergency declaration to waive budget neutrality for the changes, given these difficult times for practices across the country.

What next steps to take

The AGA and our sister societies are developing comment letters in response to the proposals in the 2021 MPFS proposed rule. Medicare plans to publish its final decisions for 2021 in December. Please do your part by visiting the AGA Advocacy Action Center at https://gastro.quorum.us/AGAactioncenter/ to tell your lawmakers to stop the proposed 2021 payment cuts and preserve care for patients by waiving Medicare’s budget-neutrality requirements for E/M adjustments.

References

1. Serper M et al. Positive early patient and clinician experience with telemedicine in an academic gastroenterology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 18]. Gastroenterology. 2020;S0016-5085(20)34834-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.034.

2. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.

3. https://gastro.org/news/prepare-for-and-help-prevent-2021-medicare-cuts-to-gi/.

Dr. Gangarosa is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, and chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; Dr. Mehta is associate chief innovation officer at Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, a gastroenterologist, assistant professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine, senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, affiliated faculty member at the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, and AGA RUC Adviser. They have no conflicts of interest.

Payment cuts to nearly all of medicine, including gastroenterology, could be in store beginning Jan. 1, 2021. Physicians may also face elimination of some services the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services granted temporary access to during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic according to CMS’s recently released policy and payment recommendations. These proposals could be implemented as physician practices are still recovering financially from states’ temporary ban on elective surgeries from March through May 2020 in response to the public health emergency (PHE) and continuing to deal with the clinical and financial challenges of the pandemic.

In early August, CMS proposed a number of changes for 2021 that affect physicians. There’s plenty of good, bad, and ugly in this proposed rule.

Let’s start with two positives (The good):

Medicare proposes to maintain the current values for colonoscopy with biopsy (45385) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy (43239). Despite a recent reevaluation of these codes in 2016 and 2014, respectively, Medicare conceded to Anthem’s suggestion that the procedures were not overvalued and needed another evaluation. The AGA and our sister societies’ data affirmed the current values and Medicare proposed to maintain them in 2021.

Medicare proposes to increase the price for scope video system equipment (ES031) from $36,306 to $70,673.38 and the suction machine (Gomco) (EQ235) from $1,981.66 to $3,195.85, phased in over 2 years. This will provide a small increase in the practice expense value for all GI endoscopy procedures. Since CMS began conducting a review of scope systems in 2017, the AGA and our sister societies have successfully worked to convince the Agency to increase its payment for GI endoscopes and associated equipment by providing invoices. We are pleased Medicare is updating these items to reflect more accurate costs.

Now onto items that could negatively affect the practice of gastroenterology.

The bad

Medicare proposes to stop covering and paying for telephone evaluation and management (E/M) visits as soon as the COVID-19 PHE expires. After originally denying that Medicare beneficiaries had trouble accessing video E/M visits and refusing to cover existing telephone (audio only) E/M codes 99441-99443, the agency responded to enormous pressure from AGA and other specialties and added the codes to its covered telehealth services list, setting the payment equal to office/outpatient established patient E/M codes 99212-99214 during the PHE. Telephone E/M has been a vital lifeline, allowing Medicare beneficiaries who don’t have a smart phone or reliable internet connection to access needed E/M services, while allowing them to stay safe at home during the PHE. There is evidence that our most vulnerable patients have the greatest need for telephone visits to advance their care.1

Medicare’s proposal to stop covering and paying for telephone E/M visits as soon as the COVID-19 PHE expires, while disappointing, is not surprising because of the agency’s reluctance to admit they were needed in the first place. The agency believes that creating a new code for audio-only patient interactions similar to the virtual check-in code G2012 but for a longer unit of time and with an accordingly higher value will suffice. Physicians appreciate that E/M delivered via telephone is not the same as a check-in call to a patient, and the care provided requires similar time, effort, and cognitive load as video visits. The AGA and our sister societies plan to object to Medicare’s proposal to treat these services as “check-ins” with slightly higher payment and will continue to advocate for permanent coverage of the telephone E/M CPT codes and payment parity with in-person E/M visits.

The ugly

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) conversion factor, the basis of Medicare payments, is proposed to be cut almost 11% percent from $36.09 in 2020 to $32.26 in 2021.

How it happened

Medicare agreed to implement coding and valuation changes to office and outpatient E/M codes (99202-99205, 99211-99215) in 2021 as recommended by the American Medical Association and widely supported by specialty societies. E/M services account for about 40% of all Medicare spending annually, which magnifies the impact of any changes to their relative value units (RVUs). By law, payment increases that occur from new work RVUs must be offset by a reduction, referred to as a budget-neutral adjustment, applied to offset the increase in total spending on the MPFS.2

CMS explained in the 2021 MPFS proposed rule, “If revisions to the RVUs cause expenditures for the year to change by more than $20 million, we make adjustments to ensure that expenditures do not increase or decrease by more than $20 million.” Medicare calculated that the corresponding adjustment to the conversion factor for 2021 needed to fall by nearly 11% to achieve budget neutrality. Because gastroenterologists report a significant portion of E/M in addition to performing procedures, the overall estimated impact is –5% of all reimbursement from Medicare.

What you can do

Visit the AGA Advocacy Action Center at https://gastro.quorum.us/AGAactioncenter/ and select “Fight back against CMS’s cuts to specialty care payments” to tell your lawmakers to stop these cuts and preserve care for patients by waiving Medicare’s budget neutrality requirements for E/M adjustments.

You can also use the AGA’s Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Calculator tool to determine the effect of the proposed cuts.3 By contacting AGA staff, Leslie Narramore, at [email protected] with the overall effect on your practice, you can help AGA use these data as we work with the physician community to urge Congress to prevent these payment cuts.

What AGA is doing

The AGA and our sister societies have joined the AMA and others in urging Congress and CMS to waive budget-neutrality rules for the implementation of the changes in E/M services effective 2021. We also joined with AMA and over 100 specialty societies in a letter asking Secretary of Health & Human Services Alex Azar that the agency use its authority under the public health emergency declaration to waive budget neutrality for the changes, given these difficult times for practices across the country.

What next steps to take

The AGA and our sister societies are developing comment letters in response to the proposals in the 2021 MPFS proposed rule. Medicare plans to publish its final decisions for 2021 in December. Please do your part by visiting the AGA Advocacy Action Center at https://gastro.quorum.us/AGAactioncenter/ to tell your lawmakers to stop the proposed 2021 payment cuts and preserve care for patients by waiving Medicare’s budget-neutrality requirements for E/M adjustments.

References

1. Serper M et al. Positive early patient and clinician experience with telemedicine in an academic gastroenterology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 18]. Gastroenterology. 2020;S0016-5085(20)34834-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.034.

2. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.

3. https://gastro.org/news/prepare-for-and-help-prevent-2021-medicare-cuts-to-gi/.

Dr. Gangarosa is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, and chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; Dr. Mehta is associate chief innovation officer at Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, a gastroenterologist, assistant professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine, senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, affiliated faculty member at the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, and AGA RUC Adviser. They have no conflicts of interest.

Payment cuts to nearly all of medicine, including gastroenterology, could be in store beginning Jan. 1, 2021. Physicians may also face elimination of some services the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services granted temporary access to during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic according to CMS’s recently released policy and payment recommendations. These proposals could be implemented as physician practices are still recovering financially from states’ temporary ban on elective surgeries from March through May 2020 in response to the public health emergency (PHE) and continuing to deal with the clinical and financial challenges of the pandemic.

In early August, CMS proposed a number of changes for 2021 that affect physicians. There’s plenty of good, bad, and ugly in this proposed rule.

Let’s start with two positives (The good):

Medicare proposes to maintain the current values for colonoscopy with biopsy (45385) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy (43239). Despite a recent reevaluation of these codes in 2016 and 2014, respectively, Medicare conceded to Anthem’s suggestion that the procedures were not overvalued and needed another evaluation. The AGA and our sister societies’ data affirmed the current values and Medicare proposed to maintain them in 2021.

Medicare proposes to increase the price for scope video system equipment (ES031) from $36,306 to $70,673.38 and the suction machine (Gomco) (EQ235) from $1,981.66 to $3,195.85, phased in over 2 years. This will provide a small increase in the practice expense value for all GI endoscopy procedures. Since CMS began conducting a review of scope systems in 2017, the AGA and our sister societies have successfully worked to convince the Agency to increase its payment for GI endoscopes and associated equipment by providing invoices. We are pleased Medicare is updating these items to reflect more accurate costs.

Now onto items that could negatively affect the practice of gastroenterology.

The bad

Medicare proposes to stop covering and paying for telephone evaluation and management (E/M) visits as soon as the COVID-19 PHE expires. After originally denying that Medicare beneficiaries had trouble accessing video E/M visits and refusing to cover existing telephone (audio only) E/M codes 99441-99443, the agency responded to enormous pressure from AGA and other specialties and added the codes to its covered telehealth services list, setting the payment equal to office/outpatient established patient E/M codes 99212-99214 during the PHE. Telephone E/M has been a vital lifeline, allowing Medicare beneficiaries who don’t have a smart phone or reliable internet connection to access needed E/M services, while allowing them to stay safe at home during the PHE. There is evidence that our most vulnerable patients have the greatest need for telephone visits to advance their care.1

Medicare’s proposal to stop covering and paying for telephone E/M visits as soon as the COVID-19 PHE expires, while disappointing, is not surprising because of the agency’s reluctance to admit they were needed in the first place. The agency believes that creating a new code for audio-only patient interactions similar to the virtual check-in code G2012 but for a longer unit of time and with an accordingly higher value will suffice. Physicians appreciate that E/M delivered via telephone is not the same as a check-in call to a patient, and the care provided requires similar time, effort, and cognitive load as video visits. The AGA and our sister societies plan to object to Medicare’s proposal to treat these services as “check-ins” with slightly higher payment and will continue to advocate for permanent coverage of the telephone E/M CPT codes and payment parity with in-person E/M visits.

The ugly

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) conversion factor, the basis of Medicare payments, is proposed to be cut almost 11% percent from $36.09 in 2020 to $32.26 in 2021.

How it happened

Medicare agreed to implement coding and valuation changes to office and outpatient E/M codes (99202-99205, 99211-99215) in 2021 as recommended by the American Medical Association and widely supported by specialty societies. E/M services account for about 40% of all Medicare spending annually, which magnifies the impact of any changes to their relative value units (RVUs). By law, payment increases that occur from new work RVUs must be offset by a reduction, referred to as a budget-neutral adjustment, applied to offset the increase in total spending on the MPFS.2

CMS explained in the 2021 MPFS proposed rule, “If revisions to the RVUs cause expenditures for the year to change by more than $20 million, we make adjustments to ensure that expenditures do not increase or decrease by more than $20 million.” Medicare calculated that the corresponding adjustment to the conversion factor for 2021 needed to fall by nearly 11% to achieve budget neutrality. Because gastroenterologists report a significant portion of E/M in addition to performing procedures, the overall estimated impact is –5% of all reimbursement from Medicare.

What you can do

Visit the AGA Advocacy Action Center at https://gastro.quorum.us/AGAactioncenter/ and select “Fight back against CMS’s cuts to specialty care payments” to tell your lawmakers to stop these cuts and preserve care for patients by waiving Medicare’s budget neutrality requirements for E/M adjustments.

You can also use the AGA’s Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Calculator tool to determine the effect of the proposed cuts.3 By contacting AGA staff, Leslie Narramore, at [email protected] with the overall effect on your practice, you can help AGA use these data as we work with the physician community to urge Congress to prevent these payment cuts.

What AGA is doing

The AGA and our sister societies have joined the AMA and others in urging Congress and CMS to waive budget-neutrality rules for the implementation of the changes in E/M services effective 2021. We also joined with AMA and over 100 specialty societies in a letter asking Secretary of Health & Human Services Alex Azar that the agency use its authority under the public health emergency declaration to waive budget neutrality for the changes, given these difficult times for practices across the country.

What next steps to take

The AGA and our sister societies are developing comment letters in response to the proposals in the 2021 MPFS proposed rule. Medicare plans to publish its final decisions for 2021 in December. Please do your part by visiting the AGA Advocacy Action Center at https://gastro.quorum.us/AGAactioncenter/ to tell your lawmakers to stop the proposed 2021 payment cuts and preserve care for patients by waiving Medicare’s budget-neutrality requirements for E/M adjustments.

References

1. Serper M et al. Positive early patient and clinician experience with telemedicine in an academic gastroenterology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 18]. Gastroenterology. 2020;S0016-5085(20)34834-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.034.

2. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.

3. https://gastro.org/news/prepare-for-and-help-prevent-2021-medicare-cuts-to-gi/.

Dr. Gangarosa is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, and chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; Dr. Mehta is associate chief innovation officer at Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, a gastroenterologist, assistant professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine, senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, affiliated faculty member at the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, and AGA RUC Adviser. They have no conflicts of interest.

Prepare for major changes to E/M coding starting in 2021

Evaluation and Management (E/M) coding and guidelines are about to undergo the most significant changes since their implementation in the 1990s. For now, the changes are limited to new and established outpatient visits (CPT codes 99202-99205, 99211-99215) and will take place as of Jan. 1, 2021. Changes to all E/M codes are anticipated in the coming years.

The changes to the new and established office/outpatient codes will impact everyone in health care who assigns codes, manages health information, or pays claims including physicians and qualified health professionals, coders, health information managers, payers, health systems, and hospitals. The American Medical Association (AMA) has already released a preview of the CPT 2021 changes as well as free E/M education modules. They are planning to release more educational resources in the near future.

Why were changes needed?

The AMA developed the 2021 E/M changes in response to interest from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in reducing physician burden, simplifying documentation requirements, and making changes to payments for the E/M codes. CMS’s initial proposal was to collapse office visit E/M levels 2-5 to a single payment. While the new rates would have provided a modest increase for level 2 and 3 E/M codes, they would have cut reimbursement for the top-level codes by more than 50%. There was concern that these changes would adversely affect physicians caring for complex patients across medical specialties. There was an outcry from the physician community opposing CMS’s proposal, and the agency agreed to get more input from the public before moving forward.

The AMA worked with stakeholders, including the AGA and our sister GI societies, to create E/M guidelines that decrease documentation requirements while also continuing to differentiate payment based on complexity of care. CMS announced in the 2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) final rule that it would adopt the AMA’s proposal as well as their recommended relative values for 2021 CPT E/M codes. Of note, there will be modest payment increases for most office E/M codes beginning Jan. 1, 2021, which may benefit those who manage patients with complex conditions.

In sum, what are the 2021 E/M changes

While there will be many changes to office/outpatient E/M visits, the most significant are deletion of code 99201 (Level 1 new patient visit), addition of a 15-minute prolonged services code that can be reported with 99205 and 99215, and the following restructuring of office visit code selection:

1. Elimination of history and physical as elements for code selection: While obtaining a pertinent history and performing a relevant physical exam are clinically necessary and contribute to both time and medical decision making, these elements will not factor in to code selection. Instead, the code level will be determined solely by medical decision making or time.

2. Choice of using medical decision making (MDM) or total time as the basis of E/M level documentation:

- MDM. While there will still be three MDM subcomponents (number/complexity of problems, data, and risk), extensive edits were made to the ways in which these elements are defined and tallied.

- Time. The definition of time is now minimum time, not typical time or “face-to-face” time. Minimum time represents total physician/qualified health care professional time on the date of service. This redefinition of time allows Medicare to better recognize the work involved in non–face-to-face services like care coordination and record review. Of note, these definitions only apply when code selection is based on time and not MDM.

3. Modification of the criteria for MDM: The current CMS Table of Risk was used as a foundation for designing the revised required elements for MDM.

- Terms. Removed ambiguous terms (e.g., “mild”) and defined previously ambiguous concepts (e.g., “acute or chronic illness with systemic symptoms”).

- Definitions. Defined important terms, such as “independent historian.”

- Data elements. Re-defined the data elements to move away from simply adding up tasks to focusing on how those tasks affect the management of the patient (e.g., independent interpretation of a test performed by another provider and/or discussion of test interpretation with another physician).

CMS also plans to add a new Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) add-on code as of Jan. 1, 2021, that can be used to recognize additional resource costs that are inherent in treating complex patients.

- GPCX1 - Visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single, serious, or complex chronic condition. (Add-on code, list separately in addition to office/outpatient evaluation and management visit, new or established.).

GPC1X can be reported with all levels of E/M office/outpatient codes in which care of a patient’s single, serious, or complex chronic condition is the focus. CMS plans to reimburse GPC1X at 0.33 RVUs (about $12).

Who do these changes apply to?

The changes to the E/M office/outpatient CPT codes and guidelines for new and established patients apply to all traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid, and all commercial payers. E/M HCPCS codes apply to Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans, and Medicaid only; commercial payers are not required to accept HCPCS codes.

What should you do?

Visit the AMA E/M Microsite; there you will find the AMA’s early release of the 2021 E/M coding and guideline changes, the AMA E/M learning module and future resources on the use of time and MDM that are expected to be released in March.

AMA E/M Microsite: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt/cpt-evaluation-and-management

2021 E/M changes: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

AMA E/M learning module: https://edhub.ama-assn.org/interactive/18057429

AMA MDM table: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf

Connect with your coders and/or medical billing company to create a plan for training physicians and staff to ensure a smooth transition on Jan. 1, 2021.

Contact your Electronic Health Records (EHR) vendor to confirm the system your practice uses will be ready to implement the new E/M coding and guidelines changes on Jan. 1, 2021.

Run an analysis using the new E/M office/outpatient payment rates recommended by the AMA for 2021 (https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/ruc-recommendations-minutes-voting) for each of your practice’s contracted payers to determine if your practice will benefit from the new rates. While CMS has proposed to accept the AMA recommended rates, this will not be finalized until CMS publishes the 2021 proposed rule in early July 2020.

Once CMS confirms its decision, reach out to your payers to negotiate implementing the new E/M rates starting in 2021.

With changes this big, we encourage you to prepare early. Watch for more information on the 2021 E/M changes in Washington Insider and AGA eDigest.

Dr. Kuo is the AGA’s Advisor to the AMA CPT Editorial Panel and a member of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee’s (PMEC) Coverage and Reimbursement Subcommittee (CRS) and assistant professor of medicine and gastroenterology, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Dr. Losurdo is the AGA’s Alternate Advisor to the AMA CPT Editorial Panel, a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and Managing Partner and medical director of Illinois Gastroenterology Group, Elgin, Ill.; Dr. Mehta is the AGA’s advisor to the AMA RVS Update Committee (RUC), a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and Dr. Garcia is the AGA’s Alternate Advisor to the AMA RUC, a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and assistant professor of medicine and gastroenterology at Stanford (Calif.) University. There were no conflicts of interest.

Evaluation and Management (E/M) coding and guidelines are about to undergo the most significant changes since their implementation in the 1990s. For now, the changes are limited to new and established outpatient visits (CPT codes 99202-99205, 99211-99215) and will take place as of Jan. 1, 2021. Changes to all E/M codes are anticipated in the coming years.

The changes to the new and established office/outpatient codes will impact everyone in health care who assigns codes, manages health information, or pays claims including physicians and qualified health professionals, coders, health information managers, payers, health systems, and hospitals. The American Medical Association (AMA) has already released a preview of the CPT 2021 changes as well as free E/M education modules. They are planning to release more educational resources in the near future.

Why were changes needed?

The AMA developed the 2021 E/M changes in response to interest from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in reducing physician burden, simplifying documentation requirements, and making changes to payments for the E/M codes. CMS’s initial proposal was to collapse office visit E/M levels 2-5 to a single payment. While the new rates would have provided a modest increase for level 2 and 3 E/M codes, they would have cut reimbursement for the top-level codes by more than 50%. There was concern that these changes would adversely affect physicians caring for complex patients across medical specialties. There was an outcry from the physician community opposing CMS’s proposal, and the agency agreed to get more input from the public before moving forward.

The AMA worked with stakeholders, including the AGA and our sister GI societies, to create E/M guidelines that decrease documentation requirements while also continuing to differentiate payment based on complexity of care. CMS announced in the 2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) final rule that it would adopt the AMA’s proposal as well as their recommended relative values for 2021 CPT E/M codes. Of note, there will be modest payment increases for most office E/M codes beginning Jan. 1, 2021, which may benefit those who manage patients with complex conditions.

In sum, what are the 2021 E/M changes

While there will be many changes to office/outpatient E/M visits, the most significant are deletion of code 99201 (Level 1 new patient visit), addition of a 15-minute prolonged services code that can be reported with 99205 and 99215, and the following restructuring of office visit code selection:

1. Elimination of history and physical as elements for code selection: While obtaining a pertinent history and performing a relevant physical exam are clinically necessary and contribute to both time and medical decision making, these elements will not factor in to code selection. Instead, the code level will be determined solely by medical decision making or time.

2. Choice of using medical decision making (MDM) or total time as the basis of E/M level documentation:

- MDM. While there will still be three MDM subcomponents (number/complexity of problems, data, and risk), extensive edits were made to the ways in which these elements are defined and tallied.

- Time. The definition of time is now minimum time, not typical time or “face-to-face” time. Minimum time represents total physician/qualified health care professional time on the date of service. This redefinition of time allows Medicare to better recognize the work involved in non–face-to-face services like care coordination and record review. Of note, these definitions only apply when code selection is based on time and not MDM.

3. Modification of the criteria for MDM: The current CMS Table of Risk was used as a foundation for designing the revised required elements for MDM.

- Terms. Removed ambiguous terms (e.g., “mild”) and defined previously ambiguous concepts (e.g., “acute or chronic illness with systemic symptoms”).

- Definitions. Defined important terms, such as “independent historian.”

- Data elements. Re-defined the data elements to move away from simply adding up tasks to focusing on how those tasks affect the management of the patient (e.g., independent interpretation of a test performed by another provider and/or discussion of test interpretation with another physician).

CMS also plans to add a new Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) add-on code as of Jan. 1, 2021, that can be used to recognize additional resource costs that are inherent in treating complex patients.

- GPCX1 - Visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single, serious, or complex chronic condition. (Add-on code, list separately in addition to office/outpatient evaluation and management visit, new or established.).

GPC1X can be reported with all levels of E/M office/outpatient codes in which care of a patient’s single, serious, or complex chronic condition is the focus. CMS plans to reimburse GPC1X at 0.33 RVUs (about $12).

Who do these changes apply to?

The changes to the E/M office/outpatient CPT codes and guidelines for new and established patients apply to all traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid, and all commercial payers. E/M HCPCS codes apply to Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans, and Medicaid only; commercial payers are not required to accept HCPCS codes.

What should you do?

Visit the AMA E/M Microsite; there you will find the AMA’s early release of the 2021 E/M coding and guideline changes, the AMA E/M learning module and future resources on the use of time and MDM that are expected to be released in March.

AMA E/M Microsite: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt/cpt-evaluation-and-management

2021 E/M changes: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

AMA E/M learning module: https://edhub.ama-assn.org/interactive/18057429

AMA MDM table: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf

Connect with your coders and/or medical billing company to create a plan for training physicians and staff to ensure a smooth transition on Jan. 1, 2021.

Contact your Electronic Health Records (EHR) vendor to confirm the system your practice uses will be ready to implement the new E/M coding and guidelines changes on Jan. 1, 2021.

Run an analysis using the new E/M office/outpatient payment rates recommended by the AMA for 2021 (https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/ruc-recommendations-minutes-voting) for each of your practice’s contracted payers to determine if your practice will benefit from the new rates. While CMS has proposed to accept the AMA recommended rates, this will not be finalized until CMS publishes the 2021 proposed rule in early July 2020.

Once CMS confirms its decision, reach out to your payers to negotiate implementing the new E/M rates starting in 2021.

With changes this big, we encourage you to prepare early. Watch for more information on the 2021 E/M changes in Washington Insider and AGA eDigest.

Dr. Kuo is the AGA’s Advisor to the AMA CPT Editorial Panel and a member of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee’s (PMEC) Coverage and Reimbursement Subcommittee (CRS) and assistant professor of medicine and gastroenterology, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Dr. Losurdo is the AGA’s Alternate Advisor to the AMA CPT Editorial Panel, a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and Managing Partner and medical director of Illinois Gastroenterology Group, Elgin, Ill.; Dr. Mehta is the AGA’s advisor to the AMA RVS Update Committee (RUC), a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and Dr. Garcia is the AGA’s Alternate Advisor to the AMA RUC, a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and assistant professor of medicine and gastroenterology at Stanford (Calif.) University. There were no conflicts of interest.

Evaluation and Management (E/M) coding and guidelines are about to undergo the most significant changes since their implementation in the 1990s. For now, the changes are limited to new and established outpatient visits (CPT codes 99202-99205, 99211-99215) and will take place as of Jan. 1, 2021. Changes to all E/M codes are anticipated in the coming years.

The changes to the new and established office/outpatient codes will impact everyone in health care who assigns codes, manages health information, or pays claims including physicians and qualified health professionals, coders, health information managers, payers, health systems, and hospitals. The American Medical Association (AMA) has already released a preview of the CPT 2021 changes as well as free E/M education modules. They are planning to release more educational resources in the near future.

Why were changes needed?

The AMA developed the 2021 E/M changes in response to interest from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in reducing physician burden, simplifying documentation requirements, and making changes to payments for the E/M codes. CMS’s initial proposal was to collapse office visit E/M levels 2-5 to a single payment. While the new rates would have provided a modest increase for level 2 and 3 E/M codes, they would have cut reimbursement for the top-level codes by more than 50%. There was concern that these changes would adversely affect physicians caring for complex patients across medical specialties. There was an outcry from the physician community opposing CMS’s proposal, and the agency agreed to get more input from the public before moving forward.

The AMA worked with stakeholders, including the AGA and our sister GI societies, to create E/M guidelines that decrease documentation requirements while also continuing to differentiate payment based on complexity of care. CMS announced in the 2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) final rule that it would adopt the AMA’s proposal as well as their recommended relative values for 2021 CPT E/M codes. Of note, there will be modest payment increases for most office E/M codes beginning Jan. 1, 2021, which may benefit those who manage patients with complex conditions.

In sum, what are the 2021 E/M changes

While there will be many changes to office/outpatient E/M visits, the most significant are deletion of code 99201 (Level 1 new patient visit), addition of a 15-minute prolonged services code that can be reported with 99205 and 99215, and the following restructuring of office visit code selection:

1. Elimination of history and physical as elements for code selection: While obtaining a pertinent history and performing a relevant physical exam are clinically necessary and contribute to both time and medical decision making, these elements will not factor in to code selection. Instead, the code level will be determined solely by medical decision making or time.

2. Choice of using medical decision making (MDM) or total time as the basis of E/M level documentation:

- MDM. While there will still be three MDM subcomponents (number/complexity of problems, data, and risk), extensive edits were made to the ways in which these elements are defined and tallied.

- Time. The definition of time is now minimum time, not typical time or “face-to-face” time. Minimum time represents total physician/qualified health care professional time on the date of service. This redefinition of time allows Medicare to better recognize the work involved in non–face-to-face services like care coordination and record review. Of note, these definitions only apply when code selection is based on time and not MDM.

3. Modification of the criteria for MDM: The current CMS Table of Risk was used as a foundation for designing the revised required elements for MDM.

- Terms. Removed ambiguous terms (e.g., “mild”) and defined previously ambiguous concepts (e.g., “acute or chronic illness with systemic symptoms”).

- Definitions. Defined important terms, such as “independent historian.”

- Data elements. Re-defined the data elements to move away from simply adding up tasks to focusing on how those tasks affect the management of the patient (e.g., independent interpretation of a test performed by another provider and/or discussion of test interpretation with another physician).

CMS also plans to add a new Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) add-on code as of Jan. 1, 2021, that can be used to recognize additional resource costs that are inherent in treating complex patients.

- GPCX1 - Visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single, serious, or complex chronic condition. (Add-on code, list separately in addition to office/outpatient evaluation and management visit, new or established.).

GPC1X can be reported with all levels of E/M office/outpatient codes in which care of a patient’s single, serious, or complex chronic condition is the focus. CMS plans to reimburse GPC1X at 0.33 RVUs (about $12).

Who do these changes apply to?

The changes to the E/M office/outpatient CPT codes and guidelines for new and established patients apply to all traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid, and all commercial payers. E/M HCPCS codes apply to Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans, and Medicaid only; commercial payers are not required to accept HCPCS codes.

What should you do?

Visit the AMA E/M Microsite; there you will find the AMA’s early release of the 2021 E/M coding and guideline changes, the AMA E/M learning module and future resources on the use of time and MDM that are expected to be released in March.

AMA E/M Microsite: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt/cpt-evaluation-and-management

2021 E/M changes: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

AMA E/M learning module: https://edhub.ama-assn.org/interactive/18057429

AMA MDM table: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf

Connect with your coders and/or medical billing company to create a plan for training physicians and staff to ensure a smooth transition on Jan. 1, 2021.

Contact your Electronic Health Records (EHR) vendor to confirm the system your practice uses will be ready to implement the new E/M coding and guidelines changes on Jan. 1, 2021.

Run an analysis using the new E/M office/outpatient payment rates recommended by the AMA for 2021 (https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/ruc-recommendations-minutes-voting) for each of your practice’s contracted payers to determine if your practice will benefit from the new rates. While CMS has proposed to accept the AMA recommended rates, this will not be finalized until CMS publishes the 2021 proposed rule in early July 2020.

Once CMS confirms its decision, reach out to your payers to negotiate implementing the new E/M rates starting in 2021.

With changes this big, we encourage you to prepare early. Watch for more information on the 2021 E/M changes in Washington Insider and AGA eDigest.

Dr. Kuo is the AGA’s Advisor to the AMA CPT Editorial Panel and a member of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee’s (PMEC) Coverage and Reimbursement Subcommittee (CRS) and assistant professor of medicine and gastroenterology, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Dr. Losurdo is the AGA’s Alternate Advisor to the AMA CPT Editorial Panel, a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and Managing Partner and medical director of Illinois Gastroenterology Group, Elgin, Ill.; Dr. Mehta is the AGA’s advisor to the AMA RVS Update Committee (RUC), a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and Dr. Garcia is the AGA’s Alternate Advisor to the AMA RUC, a member of the AGA PMEC’s CRS, and assistant professor of medicine and gastroenterology at Stanford (Calif.) University. There were no conflicts of interest.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

The Medicare Access and Chips Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is now law; it passed with bipartisan, virtually unanimous support in both chambers of Congress. MACRA replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate formula for physician reimbursement and replaced it with a pathway to value-based payment. This law will alter our practices more than the Affordable Care Act and to an extent not seen since the passage of the original Medicare Act. Practices that continue to hang on to our traditional colonoscopy-based fee-for-service reimbursement model will increasingly be marginalized (or discounted) by Medicare, commercial payers, and regional health systems. To thrive in the coming decade, innovative practices will move toward alternative payment models. Many practices have risk-linked bundled payments for colonoscopy, but this step is only for the interim. Long-term success will come to practices that understand the implications of episode payments, specialty medical homes, and total cost of care. Do not wait for the finances to magically appear – start now to build infrastructure. In this month’s article, Dr. Mehta provides a detailed description of how a practice might construct a bundled payment for a common inpatient disorder. No one is paying for this yet, but it will come. Now is not the time to be a “WIMP” (Gastroenterology. 2016;150:295-9).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. This payment model aims to improve the value of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries for hip and knee replacement surgery during the inpatient stay and 90-day period after discharge by holding hospitals accountable for cost and quality.1 It includes hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the United States and marks the first time that a postacute bundled payment model is mandatory for traditional Medicare patients. Although this may not seem to be relevant for gastroenterology, it marks an important signal by CMS that there will likely be more episode-payment models in the future.

Gastroenterologists have not been primary drivers or participants in these models, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage is included as 1 of the 48 clinical conditions for the postacute bundled payment program. In addition, CMS recently announced that clinical episode-based payment for GI hemorrhage will be included in hospital inpatient quality reporting (IQR) for fiscal year 2019.4 This is an opportunity for the field of gastroenterology to take a leadership role in an alternate payment model as it has for colonoscopy bundled payment,5 but it requires an understanding of the history of postacute bundled payments and the opportunities for and challenges to applying this model to GI hemorrhage. In this article, I will describe insights from our health system’s experience in evaluating different postacute bundled payment programs and participating in a GI bundled payment program.

Inpatient and postacute bundled payments

A bundled payment refers to a situation in which hospitals and physicians are incentivized to coordinate care for an episode of care across the continuum and eliminate unnecessary spending. In 1983, Medicare initiated a type of bundled payment for Part A spending on inpatient hospital care by creating prospective payment that is based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). This was a response to the rising cost of inpatient care resulting from retrospective payment that is based on hospital charges. Because hospitals would get paid the same amount for similar conditions, it resulted in shortened length of stay and reduction in the rise of inpatient costs, along with no measurable impact on quality of care.6 This was followed by prospective payment for outpatient hospital fees and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Medicare built on this by bundling physician and hospital fees through demonstration projects in coronary artery bypass graft surgery from 1991 to 1996 and orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery from 2009 to 2012, both resulting in reduced costs and no measurable impact on quality.

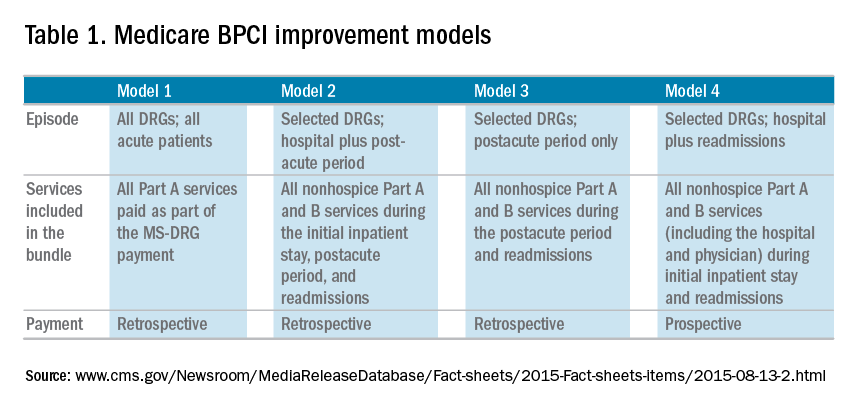

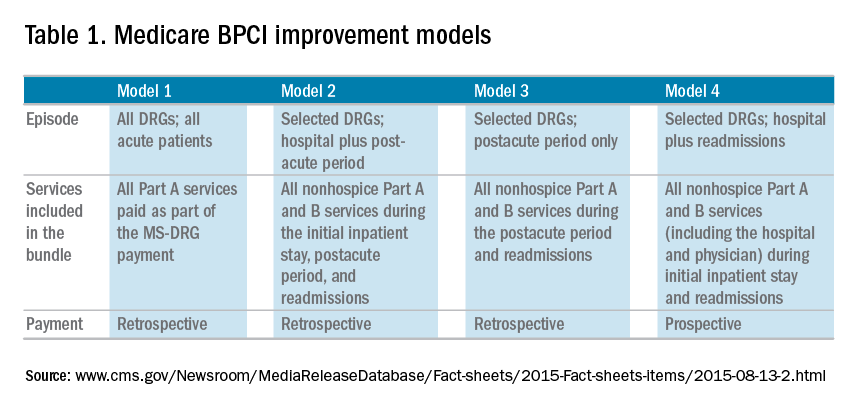

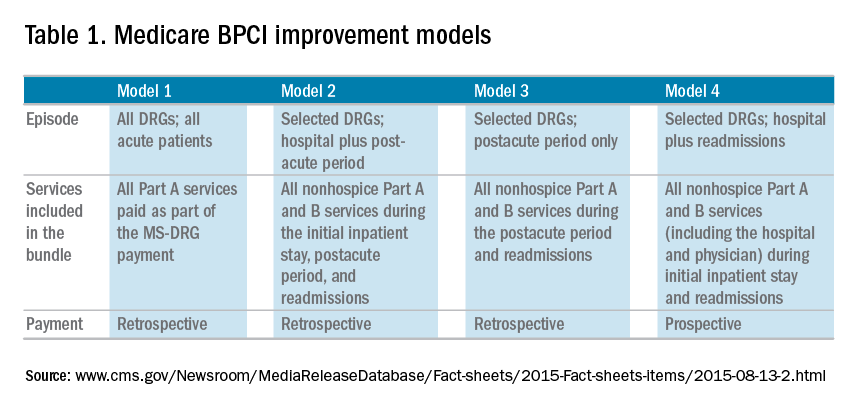

The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program built on these results in 2013 by expanding to include Part A and B services rendered up to 90 days after discharge, and as of January 2016, it includes 1,574 participants across the country. On a voluntary basis, hospitals, physician groups, and postacute providers and conveners were able to participate in 1 of 4 bundled payment models that were anchored on an inpatient for any of 48 clinical conditions that were based on MS-DRG (Table 1).

• Model 1 defined the episode as the inpatient hospital stay and bundled the facility and physician fees, similar to prior demonstration projects.

• Model 2 is a retrospective bundled payment for Part A and B services in the inpatient hospital stay and up to 90 days after discharge.

• Model 3 is a retrospective model that starts after hospital discharge and includes up to 90 days. (Models 1-3 maintain the current payment structure and retrospectively compare the actual reimbursement with target values that are based on historical data for that hospital with a 2%-3% payment reduction.)

• Model 4 makes a single, prospectively determined global payment to a hospital that encompasses all services during the hospital stay.

Opportunities in inpatient and postacute bundled payments

Participation in bundled payments requires a new set of analytic and organizational capabilities.

• The first step is to identify the patient population on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and to measure the current cost of care through external claims data and internal hospital data. This includes payments for hospital inpatient services, physician fees, postacute care, readmissions, other Part B services, and home health services. The biggest opportunity for postacute bundles is shifting site of service from postacute care to lower-cost settings and reducing readmission rates.

• Subsequently, they need to identify areas of opportunity to reduce expenditure, while also demonstrating consistent or improved quality and outcomes.

• On the basis of this, the team can identify variation in care within the cohort and in comparison with benchmarks across the country.

• After identifying areas of opportunity, the team needs to develop strategies to improve value such as care pathways, information technology tools, care coordination, and remote services.

Of the 48 clinical conditions in BPCI, 4 could be described as related to GI: esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders (Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Group [MS-DRG] 391, 392); gastrointestinal hemorrhage (MS-DRG 377, 378, 379); gastrointestinal obstruction (MS-DRG 388, 389, 390); and major bowel procedure (MS-DRG 329, 330, 331). After evaluating the GI bundles, it was apparent that these were created for billing purposes and were not clinically intuitive, which is why our institution immediately excluded the broad category of esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders. GI obstruction and major bowel surgery relate to the care of gastroenterologists, but surgeons are typically primary drivers of care for these patients. Thus, we believed that GI hemorrhage was most appropriate because gastroenterologists drive care for this condition, and there is substantial evidence about established guidelines and pathways during this episode.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

We built a multidisciplinary team of physicians, data analysts, clinical documentation specialists, and care managers to start developing a plan for improving the value of care in this population. This included data about readmissions and site of postacute care for this population, which were supplemented by chart review of financial outliers and readmissions. We quickly learned about some of the challenges to medical bundles and the GI hemorrhage bundle in particular. It is difficult to identify these patients early in the hospital stay because inclusion is based on a billing code. Many of these patients also have cardiovascular disease, cancer, or cirrhosis, which makes it hard to identify which patients will end up with primary GI hemorrhage coding until after the patient is discharged. They are also on many different inpatient services; in our hospital, there were at least 12 different admitting services. In addition, almost one-third of the patients actually had an admission before this hospitalization, often for different clinical conditions.

Most importantly, it was very challenging to develop protocols to improve the value of care in this population. Most of the patients had many comorbid conditions, so a GI hemorrhage pathway alone would not be sufficient to alter care. The two main areas of opportunity for cost savings in postacute bundled payments are postacute site of service and readmissions, both of which are hard to change for medical GI patients. For medical patients, they have many comorbidities before admission, so postacute site of service is typically driven by which site they were admitted from. This is different from surgical patients who are in SNF or rehabilitation facilities for limited time frames, and there may be more discretion to shift to lower cost settings. In addition, readmissions have not been studied much in GI hemorrhage, so it is not clear how to improve them. On the basis of these factors and the limited sample size for this condition, our health system opted to stop taking financial risk for this population.

Future opportunities for gastroenterology

However, the latest CMS Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule describes the implementation of a new quality metric for hospital IQR called the Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-Based Payment. This would hold hospitals accountable for the cost of care for GI hemorrhage admissions plus the 90 days after discharge, similar to model 2 of BPCI. This announcement, as well as the launch of mandatory orthopedic bundles, demonstrates that hospital reimbursement is shifting toward an expansion of bundled payments to include the postacute time frame. This is manifested in postacute bundles, episode-based payment, and readmission penalties. This reignited our GI hemorrhage episode team’s efforts, but with a broader purpose.

Gastroenterologists can take a leadership role in responding to episode-based payments as a way for us to demonstrate value in our collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and payers. The focus on cardiovascular disease as part of readmission penalties and core measures has allowed our cardiology colleagues to partner closely with service lines, learn about episode-based care, and garner resources to build and lead disease and episode teams. Because patients do not fit into the different clinical areas in mutually exclusive categories, we will need to collaborate with other specialties to care for the overlap with other conditions. Many heart failure and myocardial infarction patients will get readmitted for GI hemorrhage, and many GI hemorrhage patients will have concomitant cardiovascular disease or cancer. This suggests that future strategies need to integrate efforts of service lines and that there is greater opportunity for gastroenterologists than just the GI bundles.

Gastroenterologists should also participate in a proactive way. Any new payment mechanism will have some flaws in implementation, so it is more important to do what is right from a clinical standpoint rather than focusing too much on the specific billing code or payment model. These models are evolving, and we have an opportunity to have impact on future implementation. This starts with identifying and including patients from a clinical perspective rather than focusing on specific insurance types that participate in bundled payments. Some examples to improve the value of care in GI hemorrhage include creating evidence-based care pathways that span the episode of care, structured documentation after endoscopy for risk stratification, integrating pathways into the workflow of providers through the electronic health record, and increased coordination between specialties across the continuum of care. Other diagnoses that might be included in future bundles include cirrhosis, bowel obstruction, and inflammatory bowel disease. We can also learn from successful efforts in other clinical specialties that have identified variations in care and implemented a multi-modal strategy to improving care and measuring impact.

References

1. Mechanic, R.E. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment: Is it ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373[14]:1291-3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. January 26, 2015. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

3. Patel, K., Presser, E., George, M., et al. Shifting away from fee-for-service: Alternative approaches to payment in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14[4]:497-506.

4. Medicare FY 2016 IPPS final rule. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2016-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

5. Ketover, S.R. Bundled payment for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11[5]:454-7.

6. Coulam, R.F., Gaumer, G.L. Medicare’s prospective payment system: a critical appraisal. Health Care Financ Rev Annu Suppl. 1991:45-77.

Dr. Mehta is in the division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The author discloses no conflicts of interest.