User login

Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a serious and growing public health problem. In the United States an estimated 900,000 people are affected and more than 100,000 die from VTE or related complications each year. More than half of VTE events occur in association with hospitalization or major surgery; many are thought to be preventable.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),[6, 7, 8, 9] among other organizations, have identified VTE as a potentially preventable never event. Evidence‐based guidelines and resources exist to help support hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (HA‐VTE) prevention.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Harborview Medical Center, a tertiary referral center with more than 17,000 patients hospitalized annually, many requiring surgery, serves one of the highest‐risk populations for HA‐VTE development. Despite high rates of VTE prophylaxis in accordance with an established institutional guideline,[11, 12] VTE remains the most common hospital‐acquired condition in our institution.

OBJECTIVES

To improve the safety and care of all patients in our medical center and eliminate preventable HA‐VTE events, we set out to: (1) incorporate evidence‐based best practices in VTE prevention and treatment into current practice in alignment with institutional guidelines, (2) standardize the review process for all HA‐VTE events to identify opportunities for improvement, (3) utilize quality improvement (QI) analytics and information technology (IT) to actively improve our processes at the point of care, and (4) share process and outcome performance relating to VTE prevention transparently across our institution

METHODS

To prevent HA‐VTE, we employ a multifactorial strategy that includes designated clinical leadership, active engagement of all care team members, decision support tools embedded in the electronic health record (EHR), QI analytics, and retrospective and prospective reporting that provides ongoing measurement and analysis of the effectiveness of implemented interventions.

Setting/Patients

Harborview Medical Center, a 413‐bed academic tertiary referral center and the only level 1 adult and pediatric trauma and burn center for a 5‐state area, also serves as the primary safety‐net provider in the region. Harborview has centers of excellence in trauma, neurosciences, orthopedic and vascular surgery and rehabilitation, and is the only certified comprehensive stroke center in 5 states. With more than 17,000 admissions annually, including over 6000 trauma cases, HA‐VTE is a disease that spans critical and acute care settings and impacts patients on all clinical services. Harborview serves a population that is at extremely high risk for VTE as well as bleeding, particularly patients who have sustained central nervous system trauma or polytrauma.

Intervention

In 2010, at the request of the Harborview Medical Executive Board and Medical Director, we formed the Harborview VTE Task Force to assess VTE prevention practices across services and identify improvement opportunities for all hospitalized patients. This multidisciplinary team, co‐chaired by a hospitalist and trauma surgeon, includes representatives from trauma/general surgery, orthopedic surgery, hospital medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and QI. Task force members represent critical and acute care as well as the ambulatory setting. Additional stakeholders and local experts including IT directors and analysts, continuity of care nurses, and other clinical service representatives participate on an ad hoc basis.

Since its inception, the VTE Task Force has met monthly to review performance data and develop improvement initiatives. Initially we collaborated with experts across our health system to update an existing institutional VTE prophylaxis guideline to reflect current evidence‐based standards.[1, 3, 4, 5, 12] We met with all clinical services to ensure that the guidelines incorporated departmental best practices. These guidelines were integrated into our Cerner‐based (Cerner Corp., North Kansas City, MO) computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system to support accurate VTE risk assessment and appropriate ordering of prophylaxis.

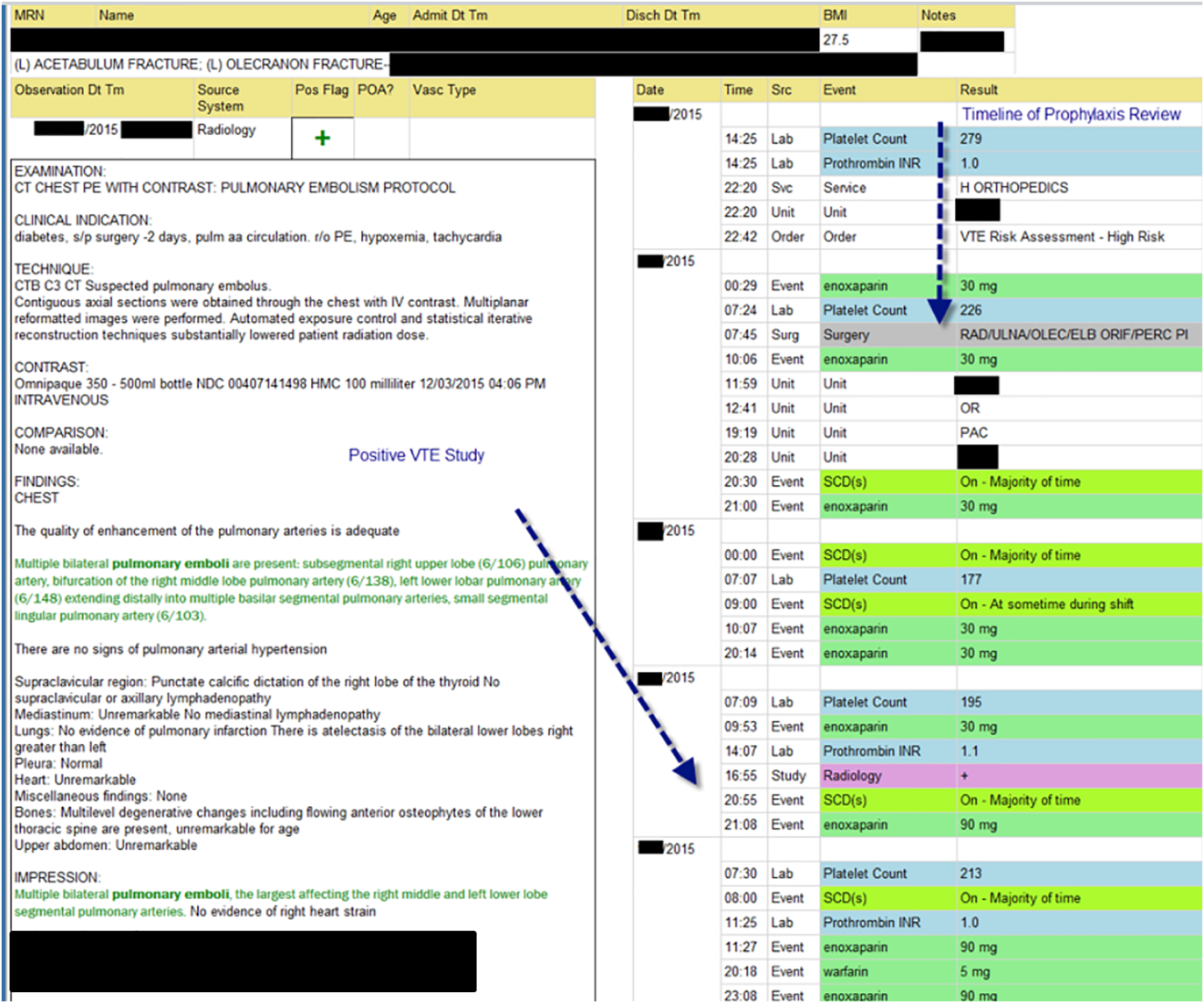

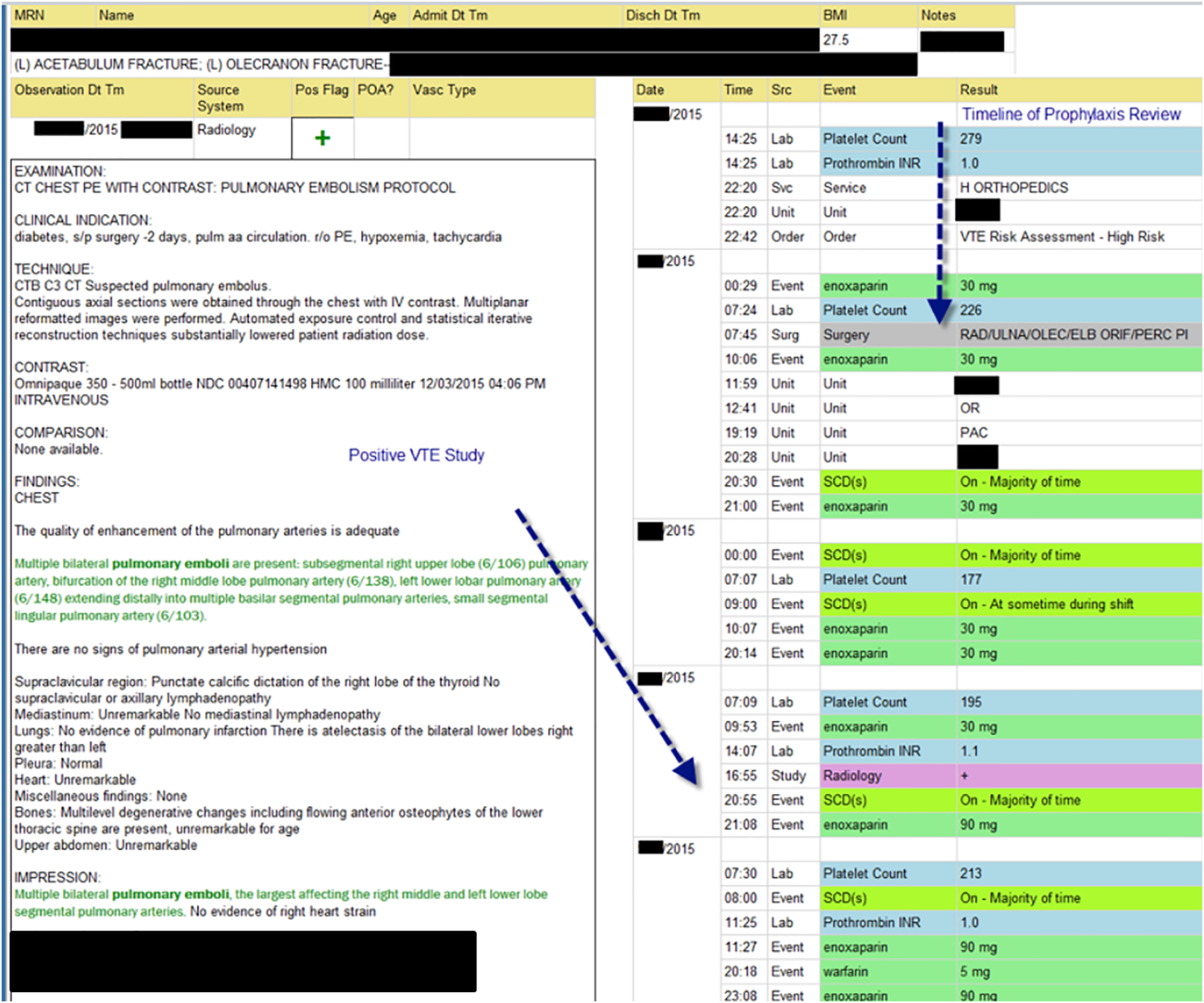

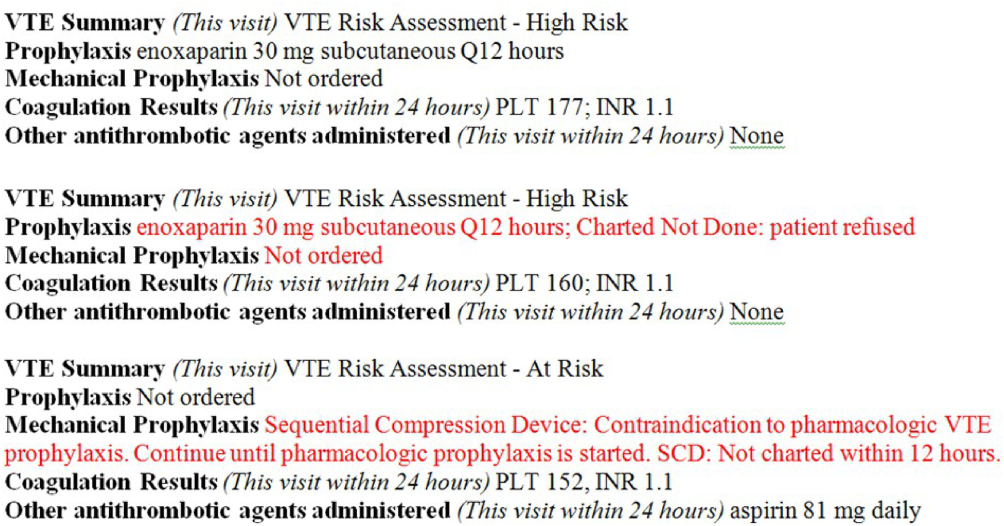

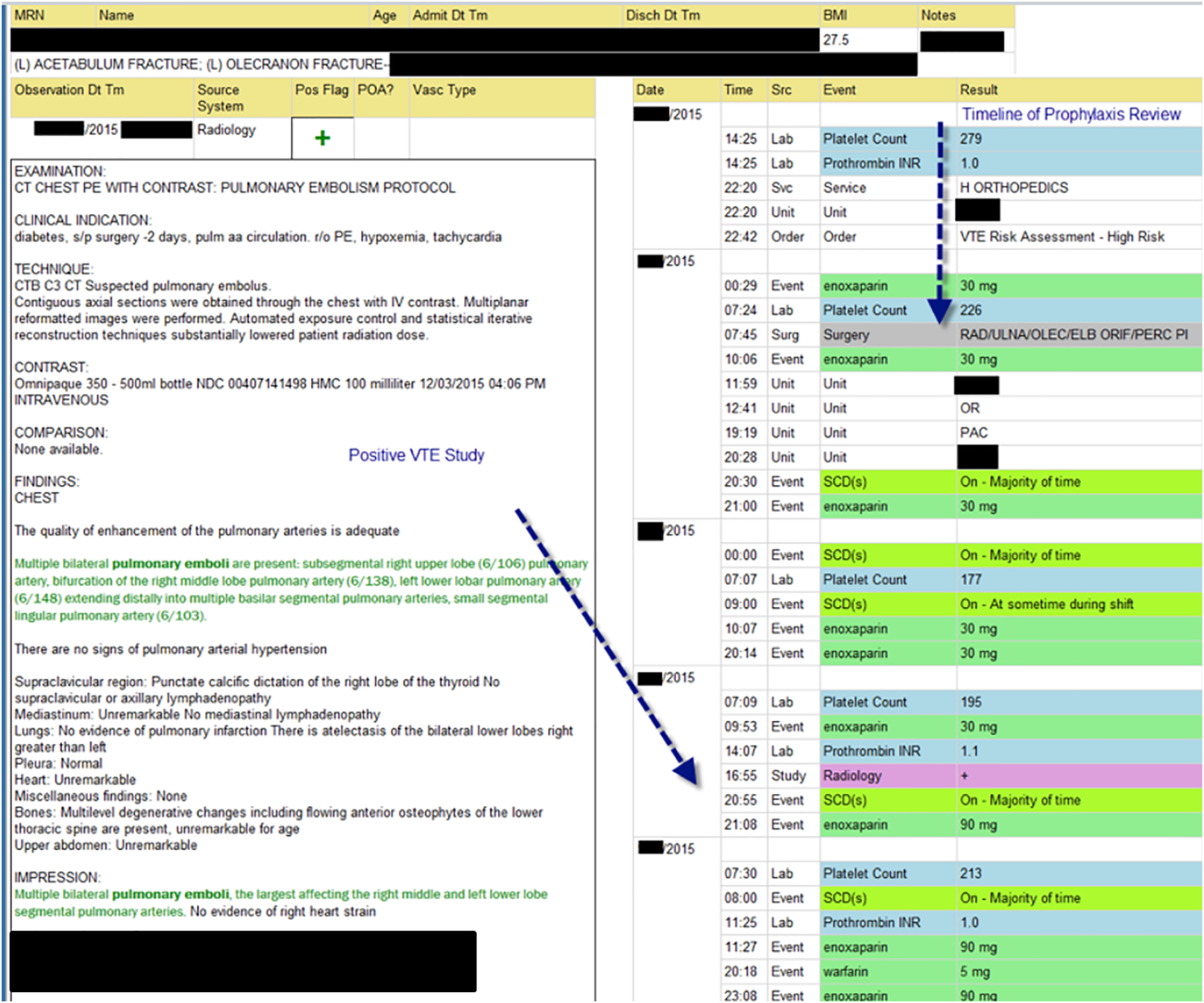

The VTE Task Force collaborated with QI programmers to develop an electronic tool, the Harborview VTE Tool (Figure 1),[13] that allows for efficient, standardized review of all HA‐VTE at monthly meetings. The tool uses word and phrase search capabilities to identify PEs and DVTs from imaging and vascular studies and links those events with pertinent demographic and clinical data from the EHR in a timeline. Information about VTE risk assigned by physicians in the CPOE system is extracted as well as specific VTE prophylaxis and treatment (drug, dose, timing of administration of medications, reason for doses being held, and orders for and application of mechanical prophylaxis). Using the VTE tool, the task force reviews each VTE event to assess the accuracy of VTE risk assignment, the appropriateness of prophylaxis received relative to guidelines, and the adequacy of VTE treatment and follow‐up. This tool has facilitated our review process, decreasing time from >30 minutes of manual chart review per event to several minutes. In recent months, a quality analyst has prescreened all VTEs prior to task force discussion to further improve efficiency. The tool allows the team to assess the case together and reach consensus regarding VTE prevention.

Prompt event reviews allow the task force to provide timely feedback about specific VTE events to physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Cases with potential opportunities for improvement are referred to a medical center‐wide QI committee for secondary review. Areas of opportunity identified are tracked and trended to direct ongoing system improvement cycles. In 2014, as a result of reviewing patient cases with VTE diagnosed after discharge, we began a similar review process to assess current practice and standardize prophylaxis across care transitions.

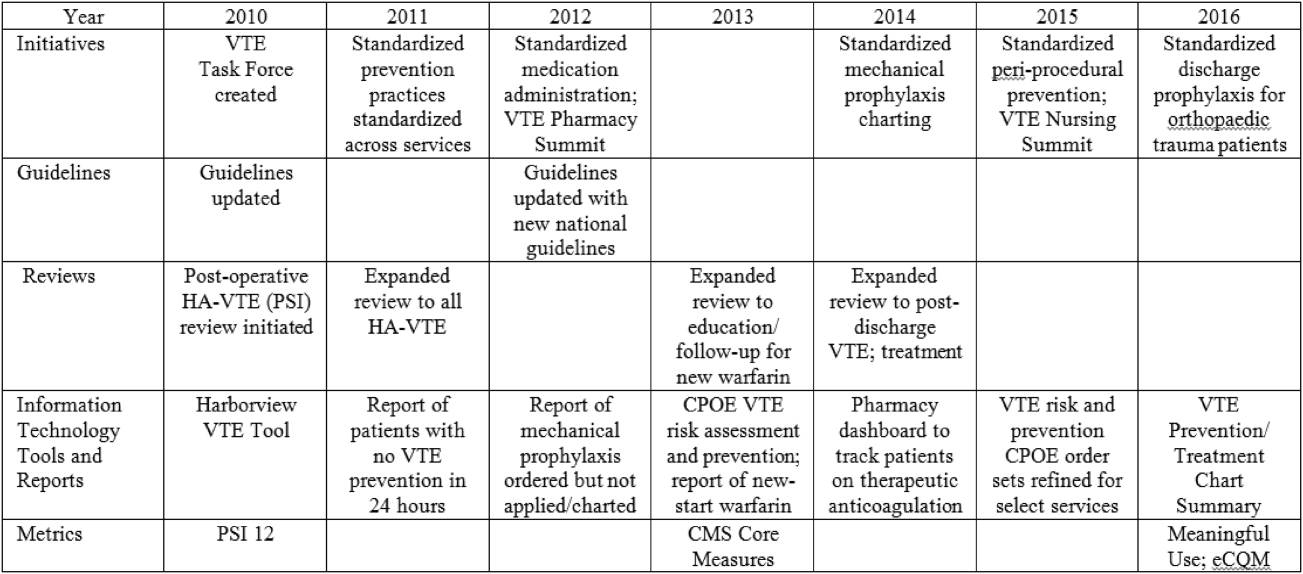

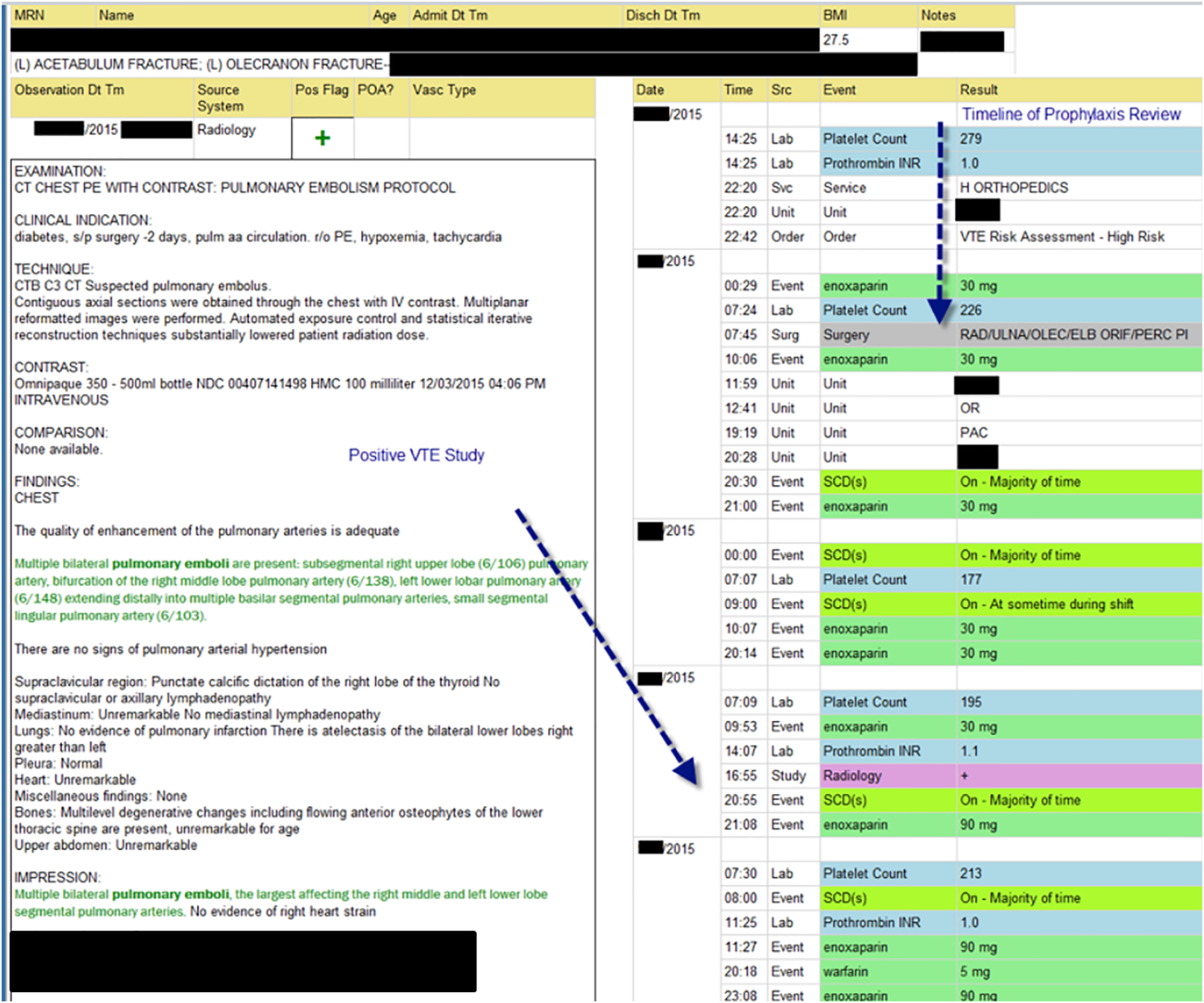

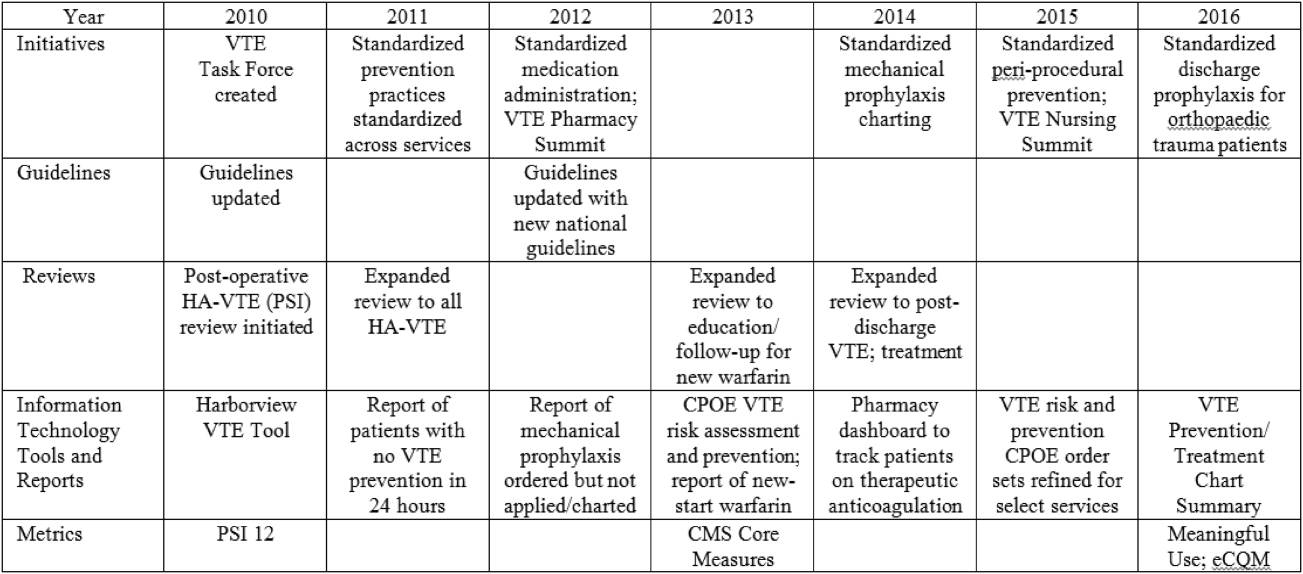

In response to opportunities identified from reviews, the VTE Task Force developed multiple reporting tools that provide real‐time, actionable information to clinicians at the bedside. Daily electronic lists highlight patients who have not received chemical or mechanical prophylaxis in 24 hours and are utilized by nursing, pharmacy, and physician groups. Patients receiving new start vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants are identified for pharmacists and discharge care coordinators to support early patient/family education and ensure appropriate follow‐up. Based on input from frontline providers, tools are continually refined to improve their clinical utility. A timeline of initiatives that the Harborview VTE Task Force has championed is outlined in Figure 2.

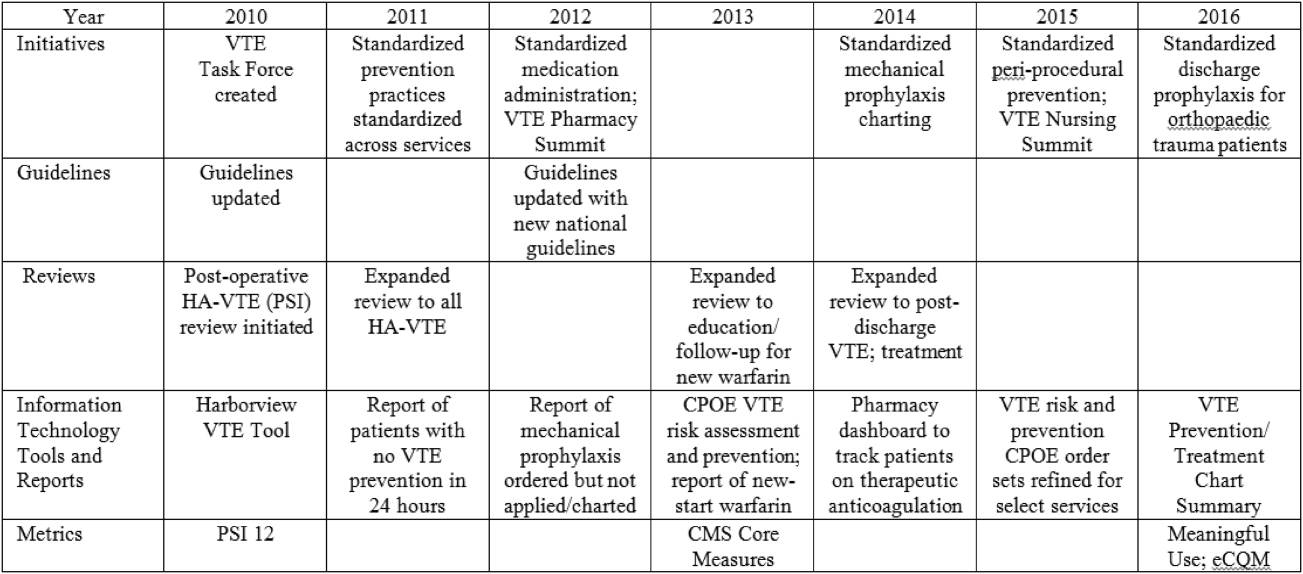

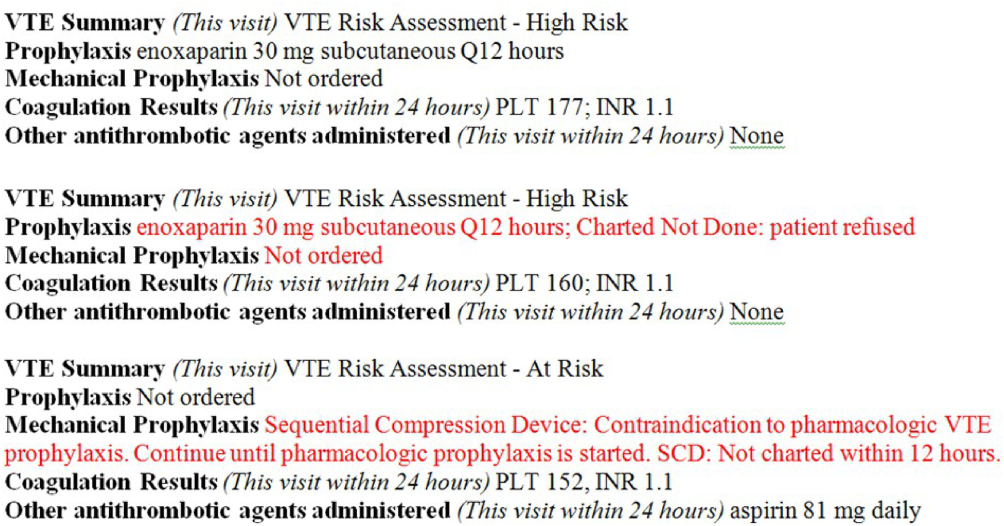

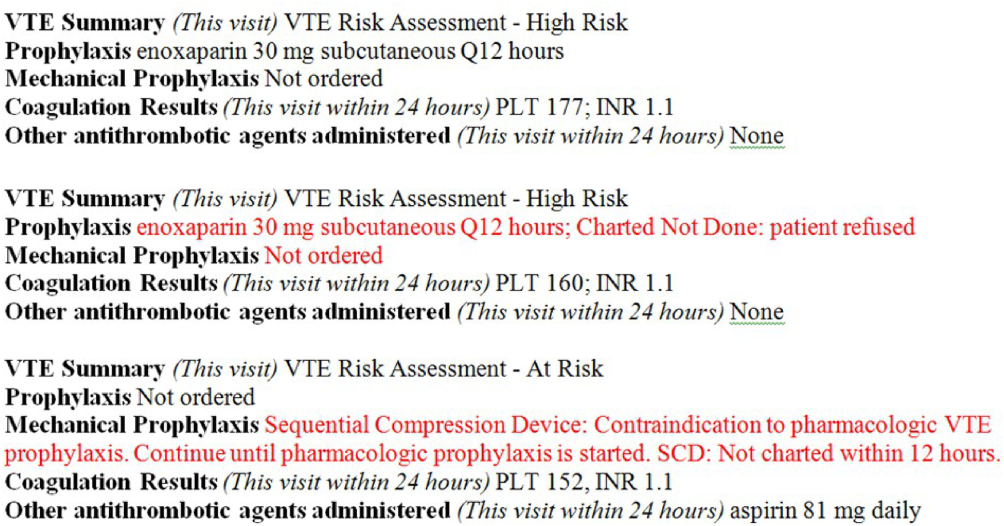

To bring HA‐VTE prevention information to the point of care, we developed a VTE Prevention/Treatment Summary within the EHR (Figure 3). Information about VTE risk assigned by the physician based on guidelines, current prophylaxis orders (pharmacologic/nonpharmacologic) and administration status, therapeutic anticoagulation and pertinent laboratory values are imported into a summary snapshot that can be accessed on demand by any member of the care team from within the patient's chart. The same data elements are being imbedded in resident physician and nursing handoff tools to highlight VTE prevention for all hospitalized patients and ensure optimal prophylaxis at transitions of care.

To emphasize Harborview's commitment to VTE prevention and ensure that care providers across the institution are aware of and engaged in this effort, we utilize our intranet to disseminate information in a fully transparent manner. Both process and outcome measures are available to all physicians and staff at service and unit levels on a Web‐based institutional dashboard. Data are updated monthly by QI analysts and improvement opportunities are highlighted in multiple fora. Descriptions of the quality metrics that are tracked are summarized in Table 1.

| Quality Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| |

| AHRQ PSI 12 | Cases of VTE not present on admission per 1000 surgical discharges with select operating room procedures |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐1 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an acute care area, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐2 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an intensive care unit or surgery date, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE 5 | Percent of patients with hospital acquired VTE discharged to home on warfarin who received education and written discharge instructions |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐6 | Percent of patients with hospital‐acquired VTE who received VTE prophylaxis prior to the event diagnosis |

MEASUREMENTS

Outcomes

Harborview benchmarks performance against hospitals nationally using the CMS Hospital Compare data and with peer academic institutions through Vizient data (Vizient, Irving, TX). To measure the impact of our initiatives, the task force began tracking postoperative VTE rates based on the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicator (PSI) 12 and expanded to include HA‐VTE rates for all hospitalized patients. We also report performance on Core Measure VTE‐6: incidence of potentially preventable VTE.

Process

We monitor VTE prophylaxis compliance based on the CMS Core Measures VTE‐1 and 2, random samples of acute and critical care patients without VTE. Internally, we measure compliance with guideline‐directed therapy for all HA‐VTE cases reviewed by the task force. With the upcoming retirement of the CMS chart‐abstracted measures, we are developing methods to track appropriate VTE prophylaxis provided to all eligible patients and will replace the sampled populations with this more expansive dataset. This approach will provide information for further improvements in VTE prophylaxis and act as an important step for success with the Electronic Clinical Quality Measures under the Meaningful Use program.

RESULTS

Our VTE prevention initiatives have resulted in improved compliance with our institutional guideline‐directed VTE prophylaxis and a decrease in HA‐VTE at our institution.

VTE Core Measures

Since the inception of VTE Core Measures in 2013, our annual performance on VTE‐1: prophylaxis for acute care patients has been above 95% and VTE‐2: prophylaxis for critical care patients has been above 98%. This performance has been consistently above the national mean for both measures (VTE‐1: 91% among Washington state hospitals and 93% nationally; VTE‐2: 95% among Washington state hospitals and 97% nationally). The CMS Hospital Compare current public reporting period is based on information collected from July 2014 through June 2015. Our internal performance for calendar year 2015 was 96% (289 of 302) for VTE‐1 and 98% (235 of 241) for VTE‐2.

Harborview has had zero potentially preventable VTE events (VTE‐6) compared with a reported national average of 4% since the inception of these measures in January 2013.

Guideline‐Directed VTE Prevention: Patients Diagnosed With HA‐VTE

The task force reviews each case to determine if the patient received guideline‐adherent prophylaxis on every day prior to the event. Patients with active bleeding or those with high bleeding risk should have mechanical prophylaxis ordered and applied until pharmacologic prophylaxis is appropriate. Any missed single dose of pharmacologic prophylaxis or missed day of applied mechanical prophylaxis is considered a possible opportunity for improvement, and the case is referred to the appropriate clinical service for additional review.

Since task force launch, the percent of all patients diagnosed with HA‐VTE who received guideline‐directed prophylaxis increased 7% from 86% (105 of 122) in 2012 to 92% (80 of 87) in the first 9 months of 2015. Of events with possible opportunities, most were deemed not to have been preventable. Some trauma patients were ineligible for pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis, some were prophylaxed according to the best available evidence, and some had risk factors (for example, active malignancy) only identified after the VTE event. The few remaining events highlighted opportunities regarding standardization of pharmacologic prophylaxis periprocedurally, documentation of application of mechanical prophylaxis, and communication of patient refusal of doses, all ongoing focus areas for improvement.

Reduction in HA‐VTE

Improved VTE prophylaxis has contributed to a 15% reduction in HA‐VTE in all hospitalized patients over 5 years from a rate of 7.5 events/1000 inpatients in 2011 to 6.4/1000 inpatients for the first 9 months of 2015. Among postoperative patients (AHRQ PSI 12), the rate of VTE decreased 21% from 11.7/1000 patients in 2011 to 9.3/1000 patients in the first 9 months of 2015.

Patient/Family Engagement

We further improved our processes to ensure that patients with HA‐VTE who discharge to home receive written discharge instructions for warfarin use (VTE‐5). In 2014, performance on this measure was 91% (51 of 56 eligible patients) and in 2015 performance improved to 96% (78 of 81 eligible patients) compared with a reported national average of 91%. Additionally, 97% (79 of 81) of patients who discharged home on warfarin after HA‐VTE now have outpatient anticoagulation follow‐up arranged prior to hospital discharge. We are developing new initiatives for patient and family education regarding direct oral anticoagulants.

Discussion/Conclusions

With interdisciplinary teamwork and use of QI analytics to drive transparency, we have improved VTE prevention and reduced rates of HA‐VTE. Harborview's HA‐VTE prevention initiative can be duplicated by other organizations given the structured nature of the intervention. The multidisciplinary approach, clinical presence of task force members, and support and engagement of senior clinical leadership have been key elements to our program's success. The existence of a standard institutional guideline based on evidence‐based national guidelines and incorporation of these standards into the EHR is vital. The VTE task force has consistently used QI analytics both for retrospective review and real‐time data feedback. Complete and easy accessibility and transparency of performance at the service and unit level supports accountability. Integration of the task force work into existing institutional QI structures has further led to improvements in patient safety.

Ongoing task force collaboration and communication with frontline providers and clinical departments has been critical to engagement and sustained improvements in VTE prevention and treatment. The work of the VTE task force represents the steadfast commitment of Harborview and our clinical staff to prevent preventable harm. This multidisciplinary effort has served as a model for other QI initiatives across our institution and health system.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):7S–47S.

- , , , . Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 suppl):S495–S501.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- , , , et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e227S–e277S.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core‐Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. AHRQ Publication No. 16‐0001‐EF. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/patient‐safety‐resources/resources/vtguide/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , . Preventing hospital‐acquired venous‐thromboembolism, a guide for effective quality improvement. Version 3.3. Venous Thromboembolism Quality Improvement Implementation Toolkit. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , , , , . Adherence to guideline‐directed venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical and surgical inpatients at 33 academic medical centers in the United States. Am J Med Qual. 2010;26(3):174–180.

- UW Medicine guidelines for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/anticoag/home. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- , , , , , . Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a descriptive study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):48–53.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a serious and growing public health problem. In the United States an estimated 900,000 people are affected and more than 100,000 die from VTE or related complications each year. More than half of VTE events occur in association with hospitalization or major surgery; many are thought to be preventable.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),[6, 7, 8, 9] among other organizations, have identified VTE as a potentially preventable never event. Evidence‐based guidelines and resources exist to help support hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (HA‐VTE) prevention.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Harborview Medical Center, a tertiary referral center with more than 17,000 patients hospitalized annually, many requiring surgery, serves one of the highest‐risk populations for HA‐VTE development. Despite high rates of VTE prophylaxis in accordance with an established institutional guideline,[11, 12] VTE remains the most common hospital‐acquired condition in our institution.

OBJECTIVES

To improve the safety and care of all patients in our medical center and eliminate preventable HA‐VTE events, we set out to: (1) incorporate evidence‐based best practices in VTE prevention and treatment into current practice in alignment with institutional guidelines, (2) standardize the review process for all HA‐VTE events to identify opportunities for improvement, (3) utilize quality improvement (QI) analytics and information technology (IT) to actively improve our processes at the point of care, and (4) share process and outcome performance relating to VTE prevention transparently across our institution

METHODS

To prevent HA‐VTE, we employ a multifactorial strategy that includes designated clinical leadership, active engagement of all care team members, decision support tools embedded in the electronic health record (EHR), QI analytics, and retrospective and prospective reporting that provides ongoing measurement and analysis of the effectiveness of implemented interventions.

Setting/Patients

Harborview Medical Center, a 413‐bed academic tertiary referral center and the only level 1 adult and pediatric trauma and burn center for a 5‐state area, also serves as the primary safety‐net provider in the region. Harborview has centers of excellence in trauma, neurosciences, orthopedic and vascular surgery and rehabilitation, and is the only certified comprehensive stroke center in 5 states. With more than 17,000 admissions annually, including over 6000 trauma cases, HA‐VTE is a disease that spans critical and acute care settings and impacts patients on all clinical services. Harborview serves a population that is at extremely high risk for VTE as well as bleeding, particularly patients who have sustained central nervous system trauma or polytrauma.

Intervention

In 2010, at the request of the Harborview Medical Executive Board and Medical Director, we formed the Harborview VTE Task Force to assess VTE prevention practices across services and identify improvement opportunities for all hospitalized patients. This multidisciplinary team, co‐chaired by a hospitalist and trauma surgeon, includes representatives from trauma/general surgery, orthopedic surgery, hospital medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and QI. Task force members represent critical and acute care as well as the ambulatory setting. Additional stakeholders and local experts including IT directors and analysts, continuity of care nurses, and other clinical service representatives participate on an ad hoc basis.

Since its inception, the VTE Task Force has met monthly to review performance data and develop improvement initiatives. Initially we collaborated with experts across our health system to update an existing institutional VTE prophylaxis guideline to reflect current evidence‐based standards.[1, 3, 4, 5, 12] We met with all clinical services to ensure that the guidelines incorporated departmental best practices. These guidelines were integrated into our Cerner‐based (Cerner Corp., North Kansas City, MO) computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system to support accurate VTE risk assessment and appropriate ordering of prophylaxis.

The VTE Task Force collaborated with QI programmers to develop an electronic tool, the Harborview VTE Tool (Figure 1),[13] that allows for efficient, standardized review of all HA‐VTE at monthly meetings. The tool uses word and phrase search capabilities to identify PEs and DVTs from imaging and vascular studies and links those events with pertinent demographic and clinical data from the EHR in a timeline. Information about VTE risk assigned by physicians in the CPOE system is extracted as well as specific VTE prophylaxis and treatment (drug, dose, timing of administration of medications, reason for doses being held, and orders for and application of mechanical prophylaxis). Using the VTE tool, the task force reviews each VTE event to assess the accuracy of VTE risk assignment, the appropriateness of prophylaxis received relative to guidelines, and the adequacy of VTE treatment and follow‐up. This tool has facilitated our review process, decreasing time from >30 minutes of manual chart review per event to several minutes. In recent months, a quality analyst has prescreened all VTEs prior to task force discussion to further improve efficiency. The tool allows the team to assess the case together and reach consensus regarding VTE prevention.

Prompt event reviews allow the task force to provide timely feedback about specific VTE events to physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Cases with potential opportunities for improvement are referred to a medical center‐wide QI committee for secondary review. Areas of opportunity identified are tracked and trended to direct ongoing system improvement cycles. In 2014, as a result of reviewing patient cases with VTE diagnosed after discharge, we began a similar review process to assess current practice and standardize prophylaxis across care transitions.

In response to opportunities identified from reviews, the VTE Task Force developed multiple reporting tools that provide real‐time, actionable information to clinicians at the bedside. Daily electronic lists highlight patients who have not received chemical or mechanical prophylaxis in 24 hours and are utilized by nursing, pharmacy, and physician groups. Patients receiving new start vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants are identified for pharmacists and discharge care coordinators to support early patient/family education and ensure appropriate follow‐up. Based on input from frontline providers, tools are continually refined to improve their clinical utility. A timeline of initiatives that the Harborview VTE Task Force has championed is outlined in Figure 2.

To bring HA‐VTE prevention information to the point of care, we developed a VTE Prevention/Treatment Summary within the EHR (Figure 3). Information about VTE risk assigned by the physician based on guidelines, current prophylaxis orders (pharmacologic/nonpharmacologic) and administration status, therapeutic anticoagulation and pertinent laboratory values are imported into a summary snapshot that can be accessed on demand by any member of the care team from within the patient's chart. The same data elements are being imbedded in resident physician and nursing handoff tools to highlight VTE prevention for all hospitalized patients and ensure optimal prophylaxis at transitions of care.

To emphasize Harborview's commitment to VTE prevention and ensure that care providers across the institution are aware of and engaged in this effort, we utilize our intranet to disseminate information in a fully transparent manner. Both process and outcome measures are available to all physicians and staff at service and unit levels on a Web‐based institutional dashboard. Data are updated monthly by QI analysts and improvement opportunities are highlighted in multiple fora. Descriptions of the quality metrics that are tracked are summarized in Table 1.

| Quality Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| |

| AHRQ PSI 12 | Cases of VTE not present on admission per 1000 surgical discharges with select operating room procedures |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐1 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an acute care area, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐2 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an intensive care unit or surgery date, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE 5 | Percent of patients with hospital acquired VTE discharged to home on warfarin who received education and written discharge instructions |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐6 | Percent of patients with hospital‐acquired VTE who received VTE prophylaxis prior to the event diagnosis |

MEASUREMENTS

Outcomes

Harborview benchmarks performance against hospitals nationally using the CMS Hospital Compare data and with peer academic institutions through Vizient data (Vizient, Irving, TX). To measure the impact of our initiatives, the task force began tracking postoperative VTE rates based on the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicator (PSI) 12 and expanded to include HA‐VTE rates for all hospitalized patients. We also report performance on Core Measure VTE‐6: incidence of potentially preventable VTE.

Process

We monitor VTE prophylaxis compliance based on the CMS Core Measures VTE‐1 and 2, random samples of acute and critical care patients without VTE. Internally, we measure compliance with guideline‐directed therapy for all HA‐VTE cases reviewed by the task force. With the upcoming retirement of the CMS chart‐abstracted measures, we are developing methods to track appropriate VTE prophylaxis provided to all eligible patients and will replace the sampled populations with this more expansive dataset. This approach will provide information for further improvements in VTE prophylaxis and act as an important step for success with the Electronic Clinical Quality Measures under the Meaningful Use program.

RESULTS

Our VTE prevention initiatives have resulted in improved compliance with our institutional guideline‐directed VTE prophylaxis and a decrease in HA‐VTE at our institution.

VTE Core Measures

Since the inception of VTE Core Measures in 2013, our annual performance on VTE‐1: prophylaxis for acute care patients has been above 95% and VTE‐2: prophylaxis for critical care patients has been above 98%. This performance has been consistently above the national mean for both measures (VTE‐1: 91% among Washington state hospitals and 93% nationally; VTE‐2: 95% among Washington state hospitals and 97% nationally). The CMS Hospital Compare current public reporting period is based on information collected from July 2014 through June 2015. Our internal performance for calendar year 2015 was 96% (289 of 302) for VTE‐1 and 98% (235 of 241) for VTE‐2.

Harborview has had zero potentially preventable VTE events (VTE‐6) compared with a reported national average of 4% since the inception of these measures in January 2013.

Guideline‐Directed VTE Prevention: Patients Diagnosed With HA‐VTE

The task force reviews each case to determine if the patient received guideline‐adherent prophylaxis on every day prior to the event. Patients with active bleeding or those with high bleeding risk should have mechanical prophylaxis ordered and applied until pharmacologic prophylaxis is appropriate. Any missed single dose of pharmacologic prophylaxis or missed day of applied mechanical prophylaxis is considered a possible opportunity for improvement, and the case is referred to the appropriate clinical service for additional review.

Since task force launch, the percent of all patients diagnosed with HA‐VTE who received guideline‐directed prophylaxis increased 7% from 86% (105 of 122) in 2012 to 92% (80 of 87) in the first 9 months of 2015. Of events with possible opportunities, most were deemed not to have been preventable. Some trauma patients were ineligible for pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis, some were prophylaxed according to the best available evidence, and some had risk factors (for example, active malignancy) only identified after the VTE event. The few remaining events highlighted opportunities regarding standardization of pharmacologic prophylaxis periprocedurally, documentation of application of mechanical prophylaxis, and communication of patient refusal of doses, all ongoing focus areas for improvement.

Reduction in HA‐VTE

Improved VTE prophylaxis has contributed to a 15% reduction in HA‐VTE in all hospitalized patients over 5 years from a rate of 7.5 events/1000 inpatients in 2011 to 6.4/1000 inpatients for the first 9 months of 2015. Among postoperative patients (AHRQ PSI 12), the rate of VTE decreased 21% from 11.7/1000 patients in 2011 to 9.3/1000 patients in the first 9 months of 2015.

Patient/Family Engagement

We further improved our processes to ensure that patients with HA‐VTE who discharge to home receive written discharge instructions for warfarin use (VTE‐5). In 2014, performance on this measure was 91% (51 of 56 eligible patients) and in 2015 performance improved to 96% (78 of 81 eligible patients) compared with a reported national average of 91%. Additionally, 97% (79 of 81) of patients who discharged home on warfarin after HA‐VTE now have outpatient anticoagulation follow‐up arranged prior to hospital discharge. We are developing new initiatives for patient and family education regarding direct oral anticoagulants.

Discussion/Conclusions

With interdisciplinary teamwork and use of QI analytics to drive transparency, we have improved VTE prevention and reduced rates of HA‐VTE. Harborview's HA‐VTE prevention initiative can be duplicated by other organizations given the structured nature of the intervention. The multidisciplinary approach, clinical presence of task force members, and support and engagement of senior clinical leadership have been key elements to our program's success. The existence of a standard institutional guideline based on evidence‐based national guidelines and incorporation of these standards into the EHR is vital. The VTE task force has consistently used QI analytics both for retrospective review and real‐time data feedback. Complete and easy accessibility and transparency of performance at the service and unit level supports accountability. Integration of the task force work into existing institutional QI structures has further led to improvements in patient safety.

Ongoing task force collaboration and communication with frontline providers and clinical departments has been critical to engagement and sustained improvements in VTE prevention and treatment. The work of the VTE task force represents the steadfast commitment of Harborview and our clinical staff to prevent preventable harm. This multidisciplinary effort has served as a model for other QI initiatives across our institution and health system.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a serious and growing public health problem. In the United States an estimated 900,000 people are affected and more than 100,000 die from VTE or related complications each year. More than half of VTE events occur in association with hospitalization or major surgery; many are thought to be preventable.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),[6, 7, 8, 9] among other organizations, have identified VTE as a potentially preventable never event. Evidence‐based guidelines and resources exist to help support hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (HA‐VTE) prevention.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Harborview Medical Center, a tertiary referral center with more than 17,000 patients hospitalized annually, many requiring surgery, serves one of the highest‐risk populations for HA‐VTE development. Despite high rates of VTE prophylaxis in accordance with an established institutional guideline,[11, 12] VTE remains the most common hospital‐acquired condition in our institution.

OBJECTIVES

To improve the safety and care of all patients in our medical center and eliminate preventable HA‐VTE events, we set out to: (1) incorporate evidence‐based best practices in VTE prevention and treatment into current practice in alignment with institutional guidelines, (2) standardize the review process for all HA‐VTE events to identify opportunities for improvement, (3) utilize quality improvement (QI) analytics and information technology (IT) to actively improve our processes at the point of care, and (4) share process and outcome performance relating to VTE prevention transparently across our institution

METHODS

To prevent HA‐VTE, we employ a multifactorial strategy that includes designated clinical leadership, active engagement of all care team members, decision support tools embedded in the electronic health record (EHR), QI analytics, and retrospective and prospective reporting that provides ongoing measurement and analysis of the effectiveness of implemented interventions.

Setting/Patients

Harborview Medical Center, a 413‐bed academic tertiary referral center and the only level 1 adult and pediatric trauma and burn center for a 5‐state area, also serves as the primary safety‐net provider in the region. Harborview has centers of excellence in trauma, neurosciences, orthopedic and vascular surgery and rehabilitation, and is the only certified comprehensive stroke center in 5 states. With more than 17,000 admissions annually, including over 6000 trauma cases, HA‐VTE is a disease that spans critical and acute care settings and impacts patients on all clinical services. Harborview serves a population that is at extremely high risk for VTE as well as bleeding, particularly patients who have sustained central nervous system trauma or polytrauma.

Intervention

In 2010, at the request of the Harborview Medical Executive Board and Medical Director, we formed the Harborview VTE Task Force to assess VTE prevention practices across services and identify improvement opportunities for all hospitalized patients. This multidisciplinary team, co‐chaired by a hospitalist and trauma surgeon, includes representatives from trauma/general surgery, orthopedic surgery, hospital medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and QI. Task force members represent critical and acute care as well as the ambulatory setting. Additional stakeholders and local experts including IT directors and analysts, continuity of care nurses, and other clinical service representatives participate on an ad hoc basis.

Since its inception, the VTE Task Force has met monthly to review performance data and develop improvement initiatives. Initially we collaborated with experts across our health system to update an existing institutional VTE prophylaxis guideline to reflect current evidence‐based standards.[1, 3, 4, 5, 12] We met with all clinical services to ensure that the guidelines incorporated departmental best practices. These guidelines were integrated into our Cerner‐based (Cerner Corp., North Kansas City, MO) computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system to support accurate VTE risk assessment and appropriate ordering of prophylaxis.

The VTE Task Force collaborated with QI programmers to develop an electronic tool, the Harborview VTE Tool (Figure 1),[13] that allows for efficient, standardized review of all HA‐VTE at monthly meetings. The tool uses word and phrase search capabilities to identify PEs and DVTs from imaging and vascular studies and links those events with pertinent demographic and clinical data from the EHR in a timeline. Information about VTE risk assigned by physicians in the CPOE system is extracted as well as specific VTE prophylaxis and treatment (drug, dose, timing of administration of medications, reason for doses being held, and orders for and application of mechanical prophylaxis). Using the VTE tool, the task force reviews each VTE event to assess the accuracy of VTE risk assignment, the appropriateness of prophylaxis received relative to guidelines, and the adequacy of VTE treatment and follow‐up. This tool has facilitated our review process, decreasing time from >30 minutes of manual chart review per event to several minutes. In recent months, a quality analyst has prescreened all VTEs prior to task force discussion to further improve efficiency. The tool allows the team to assess the case together and reach consensus regarding VTE prevention.

Prompt event reviews allow the task force to provide timely feedback about specific VTE events to physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Cases with potential opportunities for improvement are referred to a medical center‐wide QI committee for secondary review. Areas of opportunity identified are tracked and trended to direct ongoing system improvement cycles. In 2014, as a result of reviewing patient cases with VTE diagnosed after discharge, we began a similar review process to assess current practice and standardize prophylaxis across care transitions.

In response to opportunities identified from reviews, the VTE Task Force developed multiple reporting tools that provide real‐time, actionable information to clinicians at the bedside. Daily electronic lists highlight patients who have not received chemical or mechanical prophylaxis in 24 hours and are utilized by nursing, pharmacy, and physician groups. Patients receiving new start vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants are identified for pharmacists and discharge care coordinators to support early patient/family education and ensure appropriate follow‐up. Based on input from frontline providers, tools are continually refined to improve their clinical utility. A timeline of initiatives that the Harborview VTE Task Force has championed is outlined in Figure 2.

To bring HA‐VTE prevention information to the point of care, we developed a VTE Prevention/Treatment Summary within the EHR (Figure 3). Information about VTE risk assigned by the physician based on guidelines, current prophylaxis orders (pharmacologic/nonpharmacologic) and administration status, therapeutic anticoagulation and pertinent laboratory values are imported into a summary snapshot that can be accessed on demand by any member of the care team from within the patient's chart. The same data elements are being imbedded in resident physician and nursing handoff tools to highlight VTE prevention for all hospitalized patients and ensure optimal prophylaxis at transitions of care.

To emphasize Harborview's commitment to VTE prevention and ensure that care providers across the institution are aware of and engaged in this effort, we utilize our intranet to disseminate information in a fully transparent manner. Both process and outcome measures are available to all physicians and staff at service and unit levels on a Web‐based institutional dashboard. Data are updated monthly by QI analysts and improvement opportunities are highlighted in multiple fora. Descriptions of the quality metrics that are tracked are summarized in Table 1.

| Quality Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| |

| AHRQ PSI 12 | Cases of VTE not present on admission per 1000 surgical discharges with select operating room procedures |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐1 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an acute care area, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐2 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an intensive care unit or surgery date, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE 5 | Percent of patients with hospital acquired VTE discharged to home on warfarin who received education and written discharge instructions |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐6 | Percent of patients with hospital‐acquired VTE who received VTE prophylaxis prior to the event diagnosis |

MEASUREMENTS

Outcomes

Harborview benchmarks performance against hospitals nationally using the CMS Hospital Compare data and with peer academic institutions through Vizient data (Vizient, Irving, TX). To measure the impact of our initiatives, the task force began tracking postoperative VTE rates based on the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicator (PSI) 12 and expanded to include HA‐VTE rates for all hospitalized patients. We also report performance on Core Measure VTE‐6: incidence of potentially preventable VTE.

Process

We monitor VTE prophylaxis compliance based on the CMS Core Measures VTE‐1 and 2, random samples of acute and critical care patients without VTE. Internally, we measure compliance with guideline‐directed therapy for all HA‐VTE cases reviewed by the task force. With the upcoming retirement of the CMS chart‐abstracted measures, we are developing methods to track appropriate VTE prophylaxis provided to all eligible patients and will replace the sampled populations with this more expansive dataset. This approach will provide information for further improvements in VTE prophylaxis and act as an important step for success with the Electronic Clinical Quality Measures under the Meaningful Use program.

RESULTS

Our VTE prevention initiatives have resulted in improved compliance with our institutional guideline‐directed VTE prophylaxis and a decrease in HA‐VTE at our institution.

VTE Core Measures

Since the inception of VTE Core Measures in 2013, our annual performance on VTE‐1: prophylaxis for acute care patients has been above 95% and VTE‐2: prophylaxis for critical care patients has been above 98%. This performance has been consistently above the national mean for both measures (VTE‐1: 91% among Washington state hospitals and 93% nationally; VTE‐2: 95% among Washington state hospitals and 97% nationally). The CMS Hospital Compare current public reporting period is based on information collected from July 2014 through June 2015. Our internal performance for calendar year 2015 was 96% (289 of 302) for VTE‐1 and 98% (235 of 241) for VTE‐2.

Harborview has had zero potentially preventable VTE events (VTE‐6) compared with a reported national average of 4% since the inception of these measures in January 2013.

Guideline‐Directed VTE Prevention: Patients Diagnosed With HA‐VTE

The task force reviews each case to determine if the patient received guideline‐adherent prophylaxis on every day prior to the event. Patients with active bleeding or those with high bleeding risk should have mechanical prophylaxis ordered and applied until pharmacologic prophylaxis is appropriate. Any missed single dose of pharmacologic prophylaxis or missed day of applied mechanical prophylaxis is considered a possible opportunity for improvement, and the case is referred to the appropriate clinical service for additional review.

Since task force launch, the percent of all patients diagnosed with HA‐VTE who received guideline‐directed prophylaxis increased 7% from 86% (105 of 122) in 2012 to 92% (80 of 87) in the first 9 months of 2015. Of events with possible opportunities, most were deemed not to have been preventable. Some trauma patients were ineligible for pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis, some were prophylaxed according to the best available evidence, and some had risk factors (for example, active malignancy) only identified after the VTE event. The few remaining events highlighted opportunities regarding standardization of pharmacologic prophylaxis periprocedurally, documentation of application of mechanical prophylaxis, and communication of patient refusal of doses, all ongoing focus areas for improvement.

Reduction in HA‐VTE

Improved VTE prophylaxis has contributed to a 15% reduction in HA‐VTE in all hospitalized patients over 5 years from a rate of 7.5 events/1000 inpatients in 2011 to 6.4/1000 inpatients for the first 9 months of 2015. Among postoperative patients (AHRQ PSI 12), the rate of VTE decreased 21% from 11.7/1000 patients in 2011 to 9.3/1000 patients in the first 9 months of 2015.

Patient/Family Engagement

We further improved our processes to ensure that patients with HA‐VTE who discharge to home receive written discharge instructions for warfarin use (VTE‐5). In 2014, performance on this measure was 91% (51 of 56 eligible patients) and in 2015 performance improved to 96% (78 of 81 eligible patients) compared with a reported national average of 91%. Additionally, 97% (79 of 81) of patients who discharged home on warfarin after HA‐VTE now have outpatient anticoagulation follow‐up arranged prior to hospital discharge. We are developing new initiatives for patient and family education regarding direct oral anticoagulants.

Discussion/Conclusions

With interdisciplinary teamwork and use of QI analytics to drive transparency, we have improved VTE prevention and reduced rates of HA‐VTE. Harborview's HA‐VTE prevention initiative can be duplicated by other organizations given the structured nature of the intervention. The multidisciplinary approach, clinical presence of task force members, and support and engagement of senior clinical leadership have been key elements to our program's success. The existence of a standard institutional guideline based on evidence‐based national guidelines and incorporation of these standards into the EHR is vital. The VTE task force has consistently used QI analytics both for retrospective review and real‐time data feedback. Complete and easy accessibility and transparency of performance at the service and unit level supports accountability. Integration of the task force work into existing institutional QI structures has further led to improvements in patient safety.

Ongoing task force collaboration and communication with frontline providers and clinical departments has been critical to engagement and sustained improvements in VTE prevention and treatment. The work of the VTE task force represents the steadfast commitment of Harborview and our clinical staff to prevent preventable harm. This multidisciplinary effort has served as a model for other QI initiatives across our institution and health system.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):7S–47S.

- , , , . Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 suppl):S495–S501.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- , , , et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e227S–e277S.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core‐Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. AHRQ Publication No. 16‐0001‐EF. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/patient‐safety‐resources/resources/vtguide/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , . Preventing hospital‐acquired venous‐thromboembolism, a guide for effective quality improvement. Version 3.3. Venous Thromboembolism Quality Improvement Implementation Toolkit. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , , , , . Adherence to guideline‐directed venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical and surgical inpatients at 33 academic medical centers in the United States. Am J Med Qual. 2010;26(3):174–180.

- UW Medicine guidelines for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/anticoag/home. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- , , , , , . Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a descriptive study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):48–53.

- , , , et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):7S–47S.

- , , , . Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 suppl):S495–S501.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- , , , et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e227S–e277S.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core‐Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. AHRQ Publication No. 16‐0001‐EF. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/patient‐safety‐resources/resources/vtguide/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , . Preventing hospital‐acquired venous‐thromboembolism, a guide for effective quality improvement. Version 3.3. Venous Thromboembolism Quality Improvement Implementation Toolkit. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , , , , . Adherence to guideline‐directed venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical and surgical inpatients at 33 academic medical centers in the United States. Am J Med Qual. 2010;26(3):174–180.

- UW Medicine guidelines for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/anticoag/home. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- , , , , , . Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a descriptive study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):48–53.

© 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine

Improving VTE Prevention

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States among hospitalized patients.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] Although it may not be possible to completely eradicate VTE events,[7] chemical and/or mechanical prophylaxis can reduce VTE rates by up to 74% to 86%,[8, 9, 10] and meta‐analyses have demonstrated the benefit of VTE prophylaxis in the inpatient population.[11, 12] Despite evidence‐based guidelines regarding the appropriate type, duration, and dosing of prophylaxis, thromboprophylaxis has been found to be underutilized in the inpatient setting.[13, 14, 15]

Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH) historically performed poorly on VTE outcome measures. VTE in the surgical patient population was an especially glaring problem, as NMH was persistently found to be a risk‐adjusted poor performer in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (ACS‐NSQIP).

However, VTE outcome measures have been shown to be problematic due to their susceptibility to surveillance bias; that is, variation in the ordering of screening or diagnostic VTE imaging studies between hospitals leads to variable VTE rates (the more you look, the more you find).[16, 17, 18, 19] More vigilant hospitals that have a lower threshold to order an imaging study may find higher occurrences of VTE, and paradoxically be deemed a poor performer. Surveillance bias and the lack of validity of the VTE outcome measurement highlighted the importance of utilizing process‐of‐care measures in assessing hospital VTE prevention efforts.[20, 21] Thus, when the Joint Commission enacted 6 new VTE core process‐of‐care measures on January 1, 2013 to monitor hospital performance on VTE prophylaxis administration and VTE treatment (Table 1), NMH undertook a hospital‐wide quality‐improvement (QI) project utilizing the define‐measure‐analyze‐improve‐control (DMAIC) process improvement (PI) methodology to optimize their performance on these core measures as well as the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) SCIP‐VTE‐2 measure. In this article, we describe the QI effort undertaken at NMH to improve hospital‐level measure performance and the outcomes of this effort.

| VTE Measure | Measure Calculation | Description of Issues | Interventions | Preintervention Performance, % (N)* | Postintervention Performance, % (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

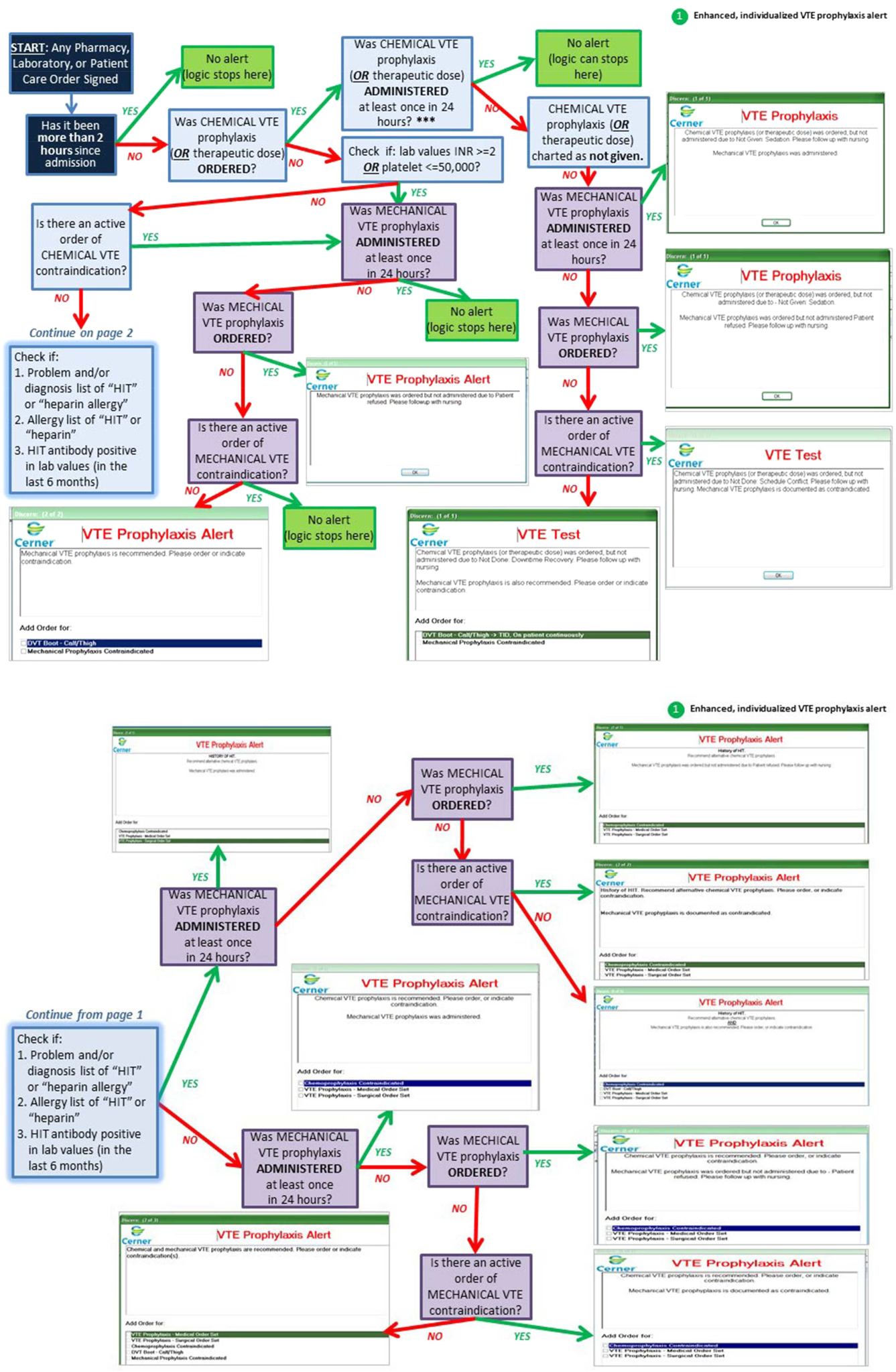

| VTE‐1: VTE PPX | Patients who received VTE prophylaxis or have documentation why no VTE prophylaxis was given | Missing documentation (both chemical and mechanical); prophylaxis ordered, but not administered; patient refusals and opportunity to increase patient education regarding prophylaxis | 1. Enhanced, individualized VTE prophylaxis alert: alert incorporated order, administration, mechanical PPX, lab exclusion and contraindication details | NMH: 86.6% (174) | NMH: 93.6% (162) |

| All patients | Undocumented contraindication reasons | 2. Nursing education initiative: back‐to‐basics VTE education initiative to help increase the administration of VTE prophylaxis and improve patient education resulting in fewer patient refusals and missed doses | NMH general surgery: 94.4% (34) | NMH general surgery: 97.6% (41) | |

| Inconsistent monitoring and patient education | 3. Updated VTE prophylaxis surgical and medicine order set: updated order listing, heparin TID setting and contraindications | NMH general medicine: 82.5% (115) | NMH general medicine: 90.2% (85) | ||

| VTE‐2: ICU VTE PPX | Patients who received VTE prophylaxis or have documentation why no VTE prophylaxis was given | See interventions 1 through 3 | NMH: 100% (58) | NMH: 95.8% (69) | |

| Patients directly admitted or transferred to the ICU | NMH general surgery: 100% (11) | NMH general surgery: 100% (10) | |||

| NMH general medicine: 100% (40) | NMH general medicine: 100% (51) | ||||

| VTE‐3: VTE patients with anticoagulation overlap therapy | Patients who received overlap therapy of parenteral anticoagulation and warfarin therapy | Gaps in documentation and administration of overlap therapy for 5 days | 4. Overlap therapy alert at discharge: document VTE on diagnosis list with alert to either (1) document reason for discontinuation of parental therapy or (2) prescribe parental anticoagulation during hospitalization or at discharge | NMH: 95.8% (159) | NMH: 100% (105) |

| Patients with confirmed VTE who received warfarin | 5. Overlap therapy alert during hospitalization: documentation alert on the day therapy discontinued | NMH general surgery: 85.7% (12) | NMH general surgery: 100% (16) | ||

| NMH general medicine: 97.0% (129) | NMH general medicine: 100% (79) | ||||

| VTE‐4: VTE patients receiving unfractionated dosages/platelet count monitoring by protocol or nomogram | Patients who have IV UFH therapy dosages and platelet counts monitored according to defined parameters such as a nomogram or protocol | Missing required language on IV UFH orders and order may not include preselected CBC order | 6. Updated heparin order sets: reminder to monitor platelet counts per nomogram and preselect CBC order | NMH: 73.7% (98) | NMH: 100% (74) |

| Patients with confirmed VTE receiving IV UFH therapy | NMH general surgery: 56.3% (7) | NMH general surgery: 100% (9) | |||

| NMH general medicine: 83.8% (88) | NMH general medicine: 100% (52) | ||||

| VTE‐5: VTE warfarin discharge instructions | Patients with documentation that they or their caregivers were given written discharge instructions or other educational material about warfarin | Discharge process is not standardized | 7. Warfarin Patient Education Task: automate nursing task for warfarin order set, check individual warfarin education excluding consult orders | NMH: 9.6% (12) | NMH: 87.5% (63) |

| Patients with confirmed VTE discharged on warfarin therapy | Patient education during hospitalization varies | 8. Warfarin dotphrase: new warfarin/Coumadin dotphrase aligned with department and core measure requirements | NMH general surgery: 0% (0) | NMH general surgery: 100% (11) | |

| No standardized process for initiating and tracking warfarin education during hospitalization | 9. Department Warfarin Instructions Phase II: update department warfarin language, automate warfarin education task | NMH general medicine: 11.3% (12) | NMH general medicine: 85.5% (50) | ||

| Warfarin special instructions for discharge is not aligned with the EMR dotphrase | 10. Physician Referral Order Update: Add follow‐up reason to order | ||||

| Follow‐up appointments are inconsistent | |||||

| VTE‐6: Incidence of potentially preventable VTE | Patients who received no VTE PPX prior to the VTE diagnostic test order date | Failure reasons related to other measures | NMH: 8% (8) | NMH: 2.4% (2) | |

| Patients who developed confirmed VTE during hospitalization | NMH general surgery: 6.7% (1) | NMH general surgery: 0% (0) | |||

| NMH general medicine: 13.5% (7) | NMH general medicine: 0% (0) | ||||

| SCIP‐VTE‐2 | Surgery patients who receive appropriate VTE prophylaxis within 24 hours prior to anesthesia start time to 24 hours after anesthesia end time | Standard enoxaparin administration time is 1300 and there is a gap between surgery end time to enoxaparin administration (i.e. patient may wait up to 23 hours for prophylaxis) | 11. Updated VTE prophylaxis‐surgical and medicine order set: added 1‐time and 2‐time heparin doses to enoxaparin order section | NMH: 99.5% (202) | NMH: 100% (104) |

| All selected surgery patients | NMH General Surgery: 98.5% (67) | NMH General Surgery: 100% (100) | |||

| NMH General Medicine: N/A | NMH General Medicine: N/A | ||||

| Additional interventions | Incomplete VTE prophylaxis information | 12. Updated IPC view | |||

| Inconsistent documentation across forms | 13. Updated ADL forms and iView nursing responses updated | ||||

| 14. Updated unit snapshot to mirror IPC view | |||||

| 15. Updated MPET: updated nursing task: standardize Not Given and Not Done Nursing Responses | |||||

METHODS

Setting

NMH is a tertiary referral and teaching hospital affiliated with the Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University. It is the flagship of Northwestern Medicine, which also includes 4 community hospitals, a dedicated women's hospital, and outpatient and urgent care centers.[22] NMH is an 885‐bed hospital with approximately 50,000 inpatients admitted annually. This project, to evaluate the outcomes of the NMH VTE QI initiative, was reviewed and approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board as an exempt activity.

Measures

The Joint Commission VTE measures were a product of the National Consensus Standards for the Prevention and Care of Deep Vein Thrombosis project between the Joint Commission and National Quality Forum (NQF). These 6 measures are endorsed by the NQF and aligned with the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services.[23] SCIP also has measures focusing on VTE prophylaxis. SCIP‐VTE‐2 focuses on prophylaxis in the perioperative period (the 24 hours prior to anesthesia start time to 24 hours postanesthesia end time). Specific measure definitions are in Table 1. All patients hospitalized at NMH were eligible for case abstraction; specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on measure specifics set forth by The Joint Commission and SCIP, and random cases were selected for abstraction utilizing the standard sampling methodology required for these measures. Case abstraction was performed by a nurse and validated by physicians.

The Intervention

Review of baseline performance on the core measures began in January 2013. Common failure points were identified first by electronic medical record (EMR) evaluation. Subsequently, focus groups with front‐line staff, close examination of EMR ordering logic for chemical and mechanical prophylaxis with the IT department, hospital floor observations, and evaluation of the patient education process during discharge were performed to further define the reasons for common failure points.

Fifteen data‐driven, focused interventions were then designed, pilot tested, and implemented throughout the hospital in May 2013, with iterative improvement of each component over the next 18 months (Table 1). This project utilized DMAIC PI methodology, and was carried out by a multidisciplinary team with representatives from the departments of surgery, internal medicine, anesthesia, gynecology, PI, clinical quality, pharmacy, analytics, information technology (IT), and nursing. Broadly, the 15 interventions consisted of (1) EMR alerts, (2) education initiatives, (3) new EMR order sets, and (4) other EMR changes.

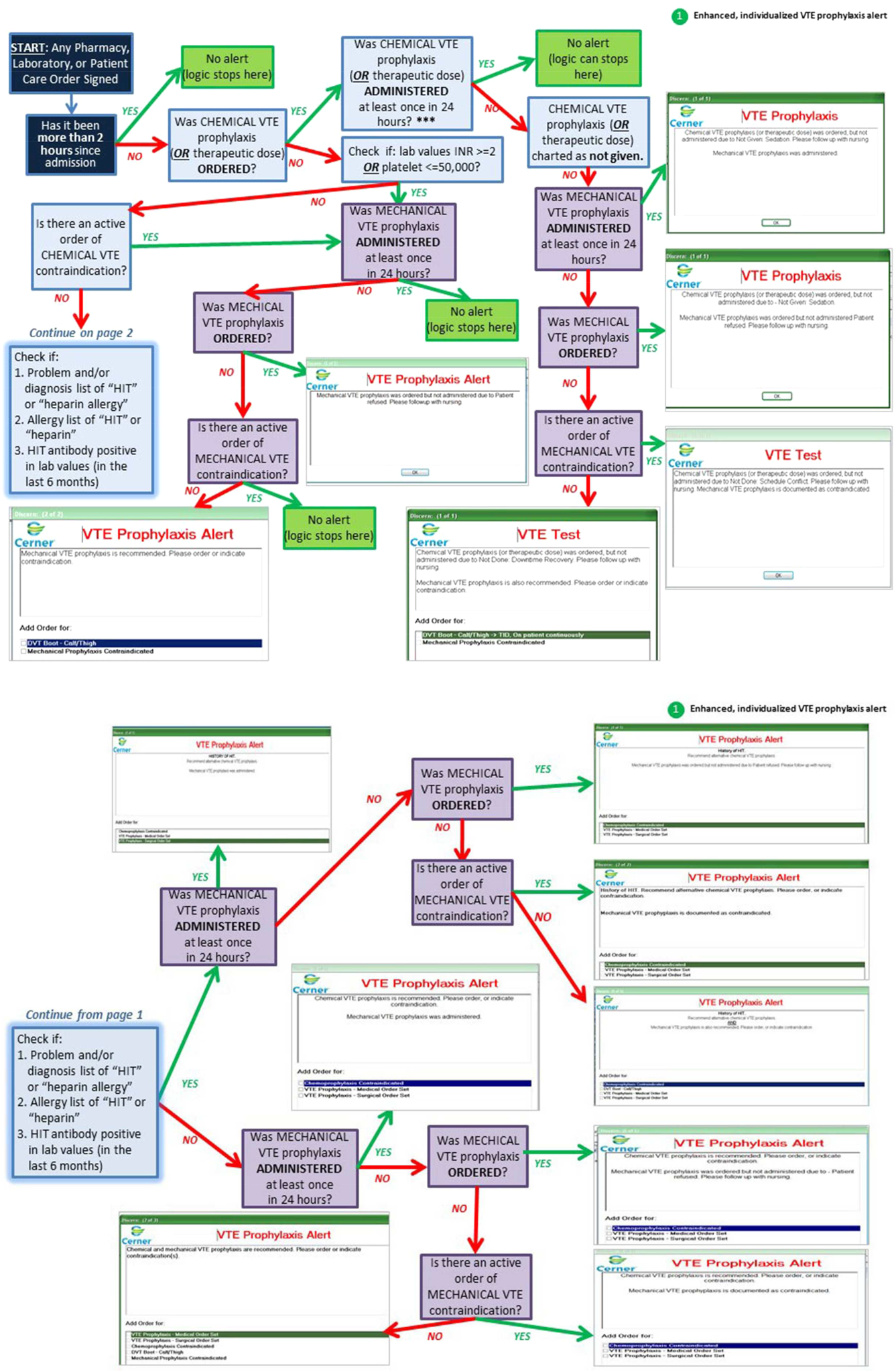

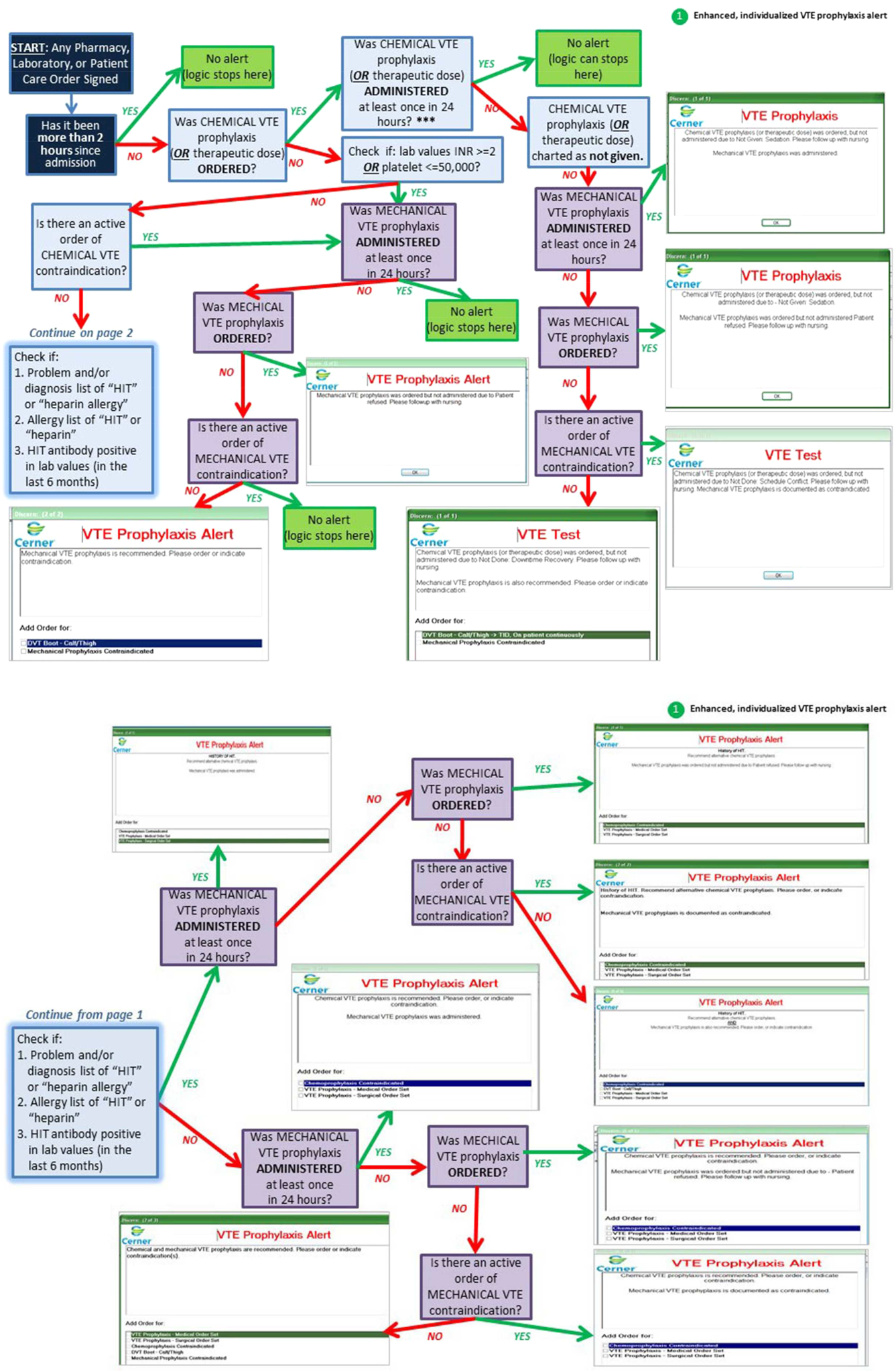

EMR Alerts

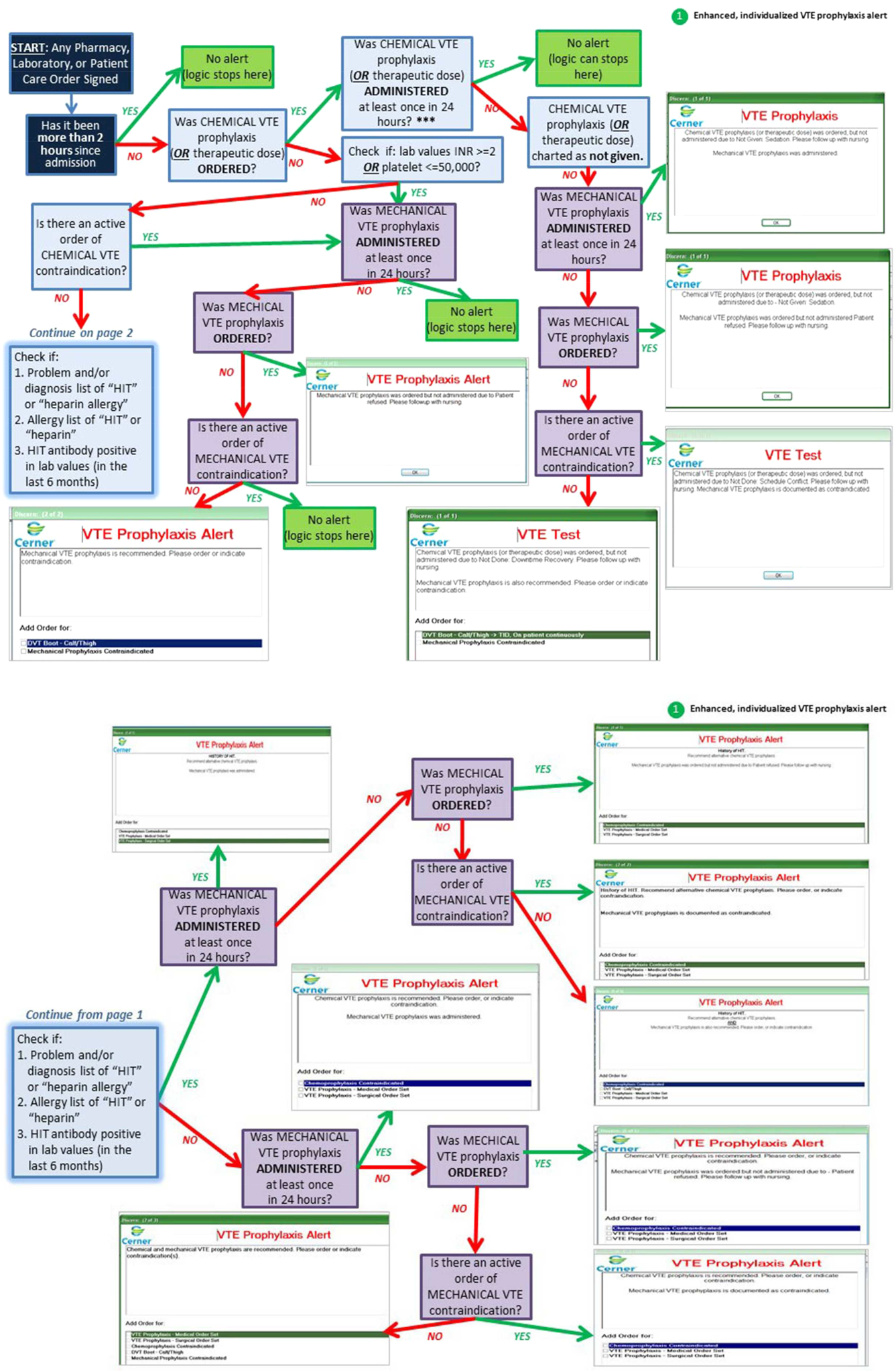

Novel provider alerts were built into NMH's inpatient EMR platform (Cerner PowerChart; Cerner Corp., North Kansas City, MO) to address common mistakes contributing to failures on VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) and VTE‐3 (overlap therapy). Although VTE‐1 failures were often multifactorial, missing documentation regarding reasons for no chemoprophylaxis given and failures to order chemoprophylaxis were 2 common drivers of failures. To address these 2 problems, a logic‐driven alert to force patient‐specific ordering of appropriate VTE prophylaxis was developed (Figure 1). VTE‐3 (overlap therapy) failures occurred due to clinician failure to order a full 5 days of overlap therapy when switching from parenteral anticoagulation to warfarin therapy; hence, to target VTE‐3 performance, new alerts reminding clinicians to meticulously order and document the overlap of parenteral VTE therapy and warfarin were developed. As part of the logic‐driven alert to improve patient‐specific ordering of appropriate VTE prophylaxis, we allowed for the inclusion of documentation of a contraindication to explain why VTE prophylaxis was not ordered.

Educational Initiatives

After consulting with attending physicians, residents, nurses, and practice managers at NMH to understand the potential drivers of VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) failures, a team of clinicians and PI experts held 2‐part interactive educational sessions with nurses to address knowledge deficits. The first part focused on general VTE education (eg, the significance of the problem nationwide as well as at NMH, general signs and symptoms of VTE, risk factors for VTE, and NMH‐specific failure rates for mechanical and chemoprophylaxis). The second portion used a myth‐busting approach, in which common misunderstandings that frequently impede VTE prophylaxis (eg, a patient capable of ambulating does not need sequential compression devices (SCDs), or SCDs cannot be applied to a patient with acute or chronic DVT) were discussed. Educational efforts also addressed VTE‐5 (warfarin discharge instructions) performance; although nurses provided patient education with regard to home warfarin use, the timing was inconsistent. The VTE‐5 education provided nurses with a standardized method and time for educating patients about postdischarge warfarin use. EMR changes ensured that when warfarin was ordered, warfarin education automatically populated the nurse's task list, reminding them to educate their patients prior to discharge.

New EMR Order Sets

Previously existing order sets often made it difficult for physicians to order the correct dosing and timing of VTE prophylaxis, document contraindications to prophylaxis, and lacked the appropriate laboratory orders with therapy orders. New order sets were designed to facilitate compliance with VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis), VTE‐4 (platelet monitoring), VTE‐5 (warfarin discharge instructions), and SCIP‐VTE‐2 (perioperative prophylaxis) by updating lab and medication order listings, dosing choices, prophylaxis contraindications, reminders to monitor platelet counts per nomogram, and physician follow‐up reasons. When we considered our hospital's specific local factors, we came to the conclusion that risk stratification would be a difficult strategy to apply effectively as a component of the new order sets, mainly due to barriers related to buy‐in from physicians and nurses.

Other EMR Changes

Other interventions targeted at specific issues were programmed into the EMR. For example, a shortcut (known as a dotphrase in Cerner PowerChart) for inserting warfarin instructions into patient care documentation was available to physicians, but was misaligned to the standard warfarin instructions. In addition, the physician responsible for following up on a patient's first outpatient international normalized ratio was often omitted from the discharge instructions, potentially leaving patients without a physician to adjust their dosing appropriately. Adding this physician information, as well as aligning and updating all discharge instructions, allowed for clear, consistent patient instructions for home warfarin use. Moreover, EMR forms used by physicians and forms used by nurses to check for VTE prophylaxis were inconsistent, thus leading to potential confusion between physicians and nurses. Accordingly, regularly used EMR forms (eg, the interdisciplinary plan of care, and the unit summary page or unit snapshot) were updated and standardized.

Control Mechanisms

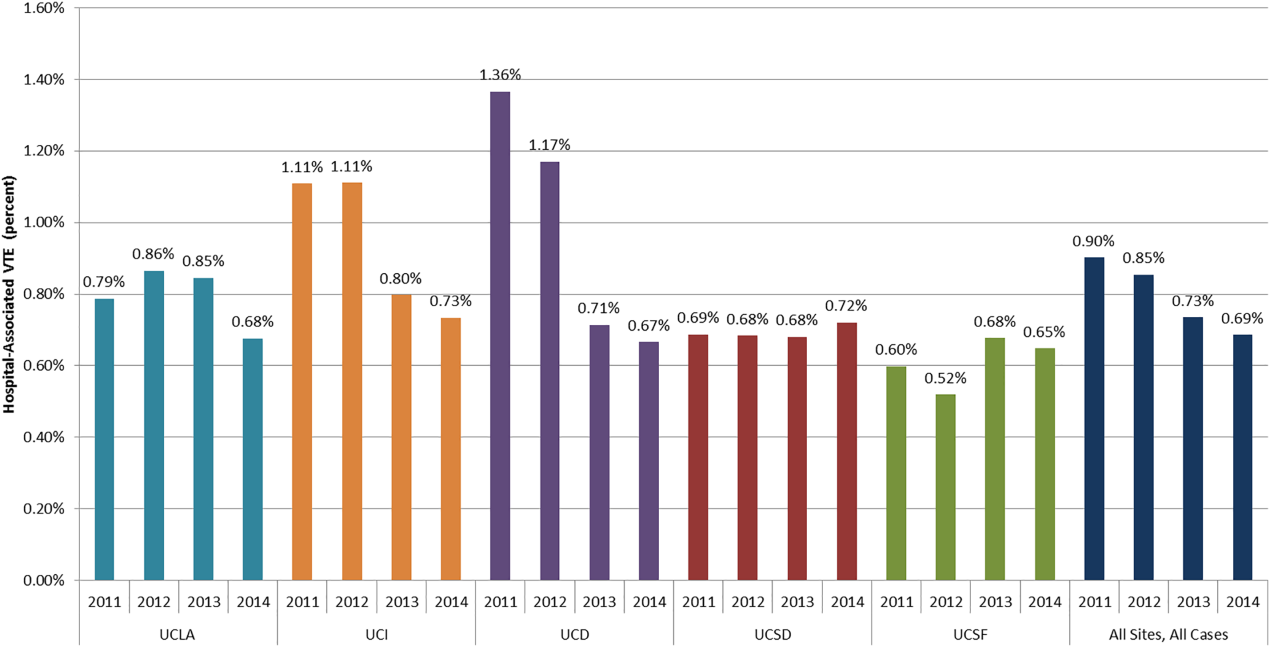

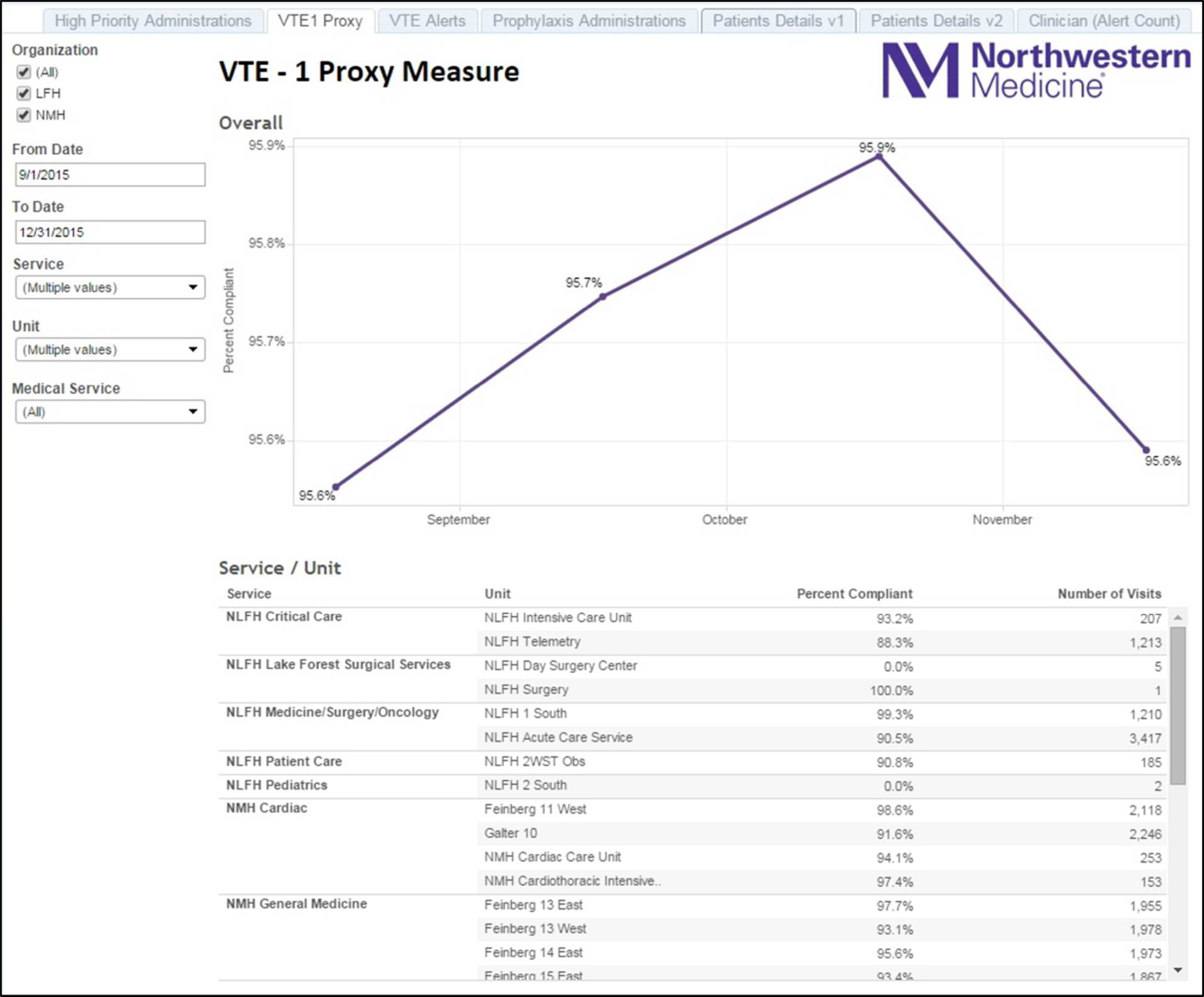

Concurrent with the implementation of the 15 interventions was the development of several control mechanisms to ensure sustained improvement. These mechanisms consisted of (1) an electronic proxy measure for VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) and (2) monitoring of clinician (including physicians, nurses, and midlevel providers) responses to the EMR alerts, and (3) a comprehensive EMR unit report (Figure 2).

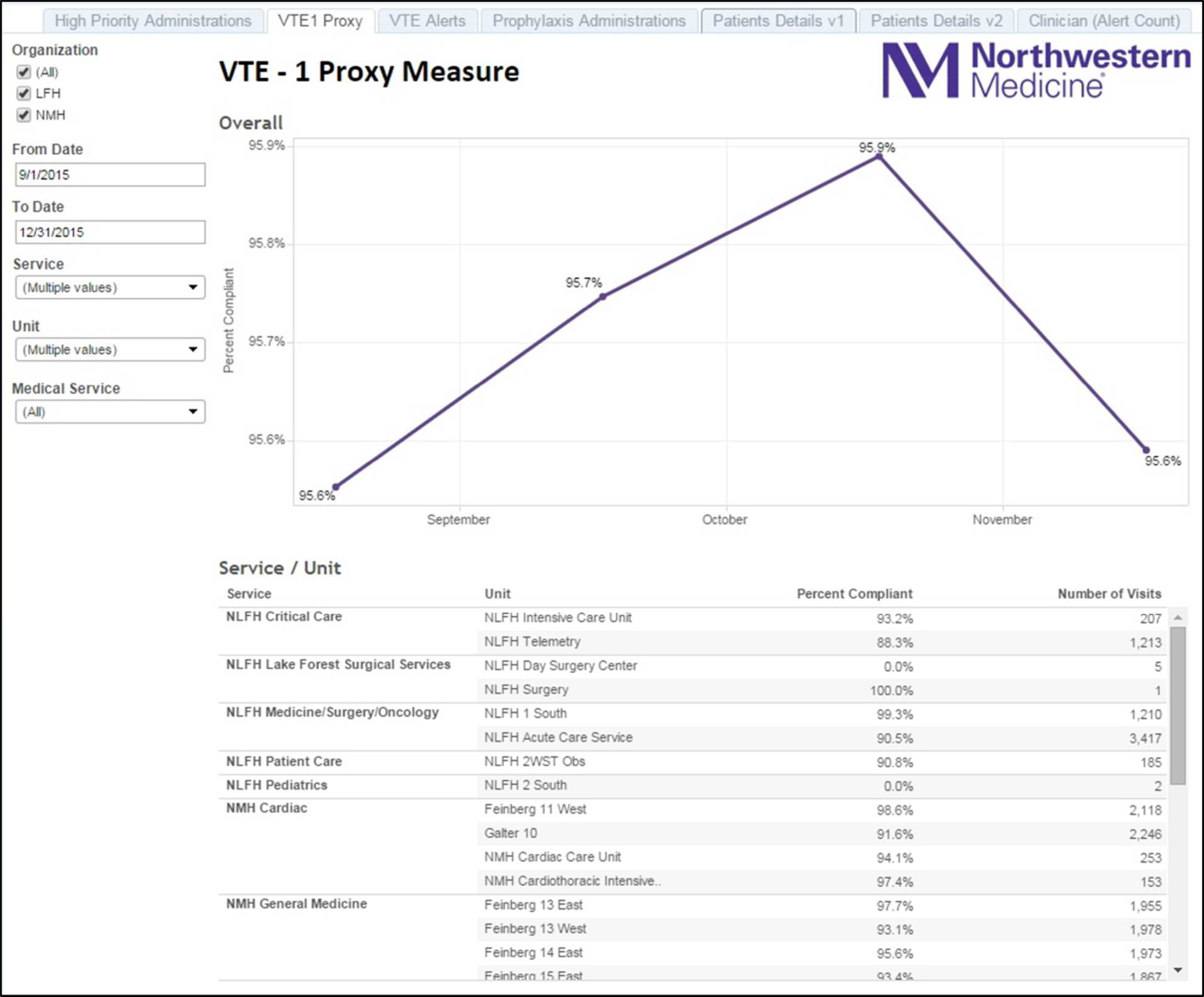

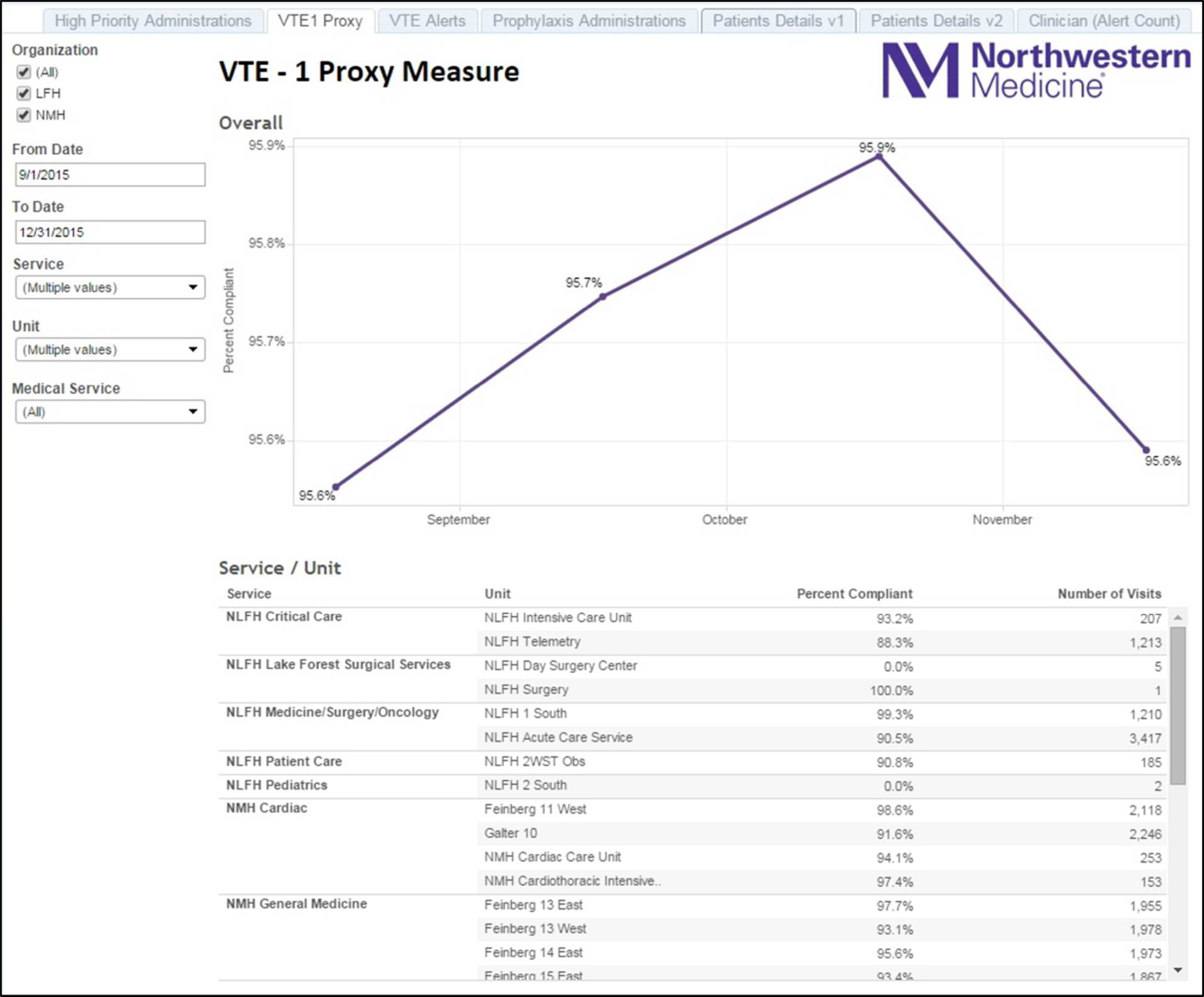

Proxy Measure

Because the Joint Commission core measures are abstracted from only a sample of cases, and a time lag existed between each failure on VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) to the time the QI team learned of the failure, a proxy measure was created. This proxy measure is used as a stand‐in for actual VTE‐1 measure performance, but is generated in real time and reflects performance throughout the entire hospital instead of a random sample of cases. Using the Northwestern Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW), the NMH analytics team created a report reflecting thromboprophylaxis administration on each hospital unit currently and over time. Performance could also be examined for each individual hospital service line. Being able to track longitudinal performance by unit and by service line enabled the QI team to understand trends in performance. Having the ability to examine patients who missed doses over the preceding few hours allowed unit leadership to proactively act upon the failures in a timely fashion, instead of waiting to receive their performance on the Joint Commission core measures.

Physician Alert Response Monitoring

Monitoring of clinical responses to EMR alerts was embedded as standard practice. Because alert fatigue is a documented unintended consequence of heavy reliance on EMR alerts,[24, 25] physicians and nurses who failed to respond to alerts regarding VTE prophylaxis were identified. Interventions targeted toward this group of nonresponders are currently being developed and tested.

EDW Unit Report

This report allows unit managers to track potential failures real time and act prior to a failure occurring (eg, missed chemoprophylaxis dose) through the NMH EDW (Figure 2). These reports contained detailed order and administration data at the individual patient, nurse, and physician levels. Missed doses of VTE chemoprophylaxis were immediately fed back to unit nursing managers who utilized the report to perform a rapid drilldown to identify the root cause(s) of the failure, and then rectify the failure while the patient was still hospitalized.

Statistical Analyses

Hospital performance on the VTE core measures and SCIP‐VTE‐2 was determined by trained nurse abstractors, who abstract cases randomly sampled by the University of HealthCare Consortium, and adjudicate findings as per the Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. Performance in the period prior to the QI intervention and in the period following the QI intervention was documented as proportions of abstracted cases found to be compliant with measure specifications. Differences between the pre‐ and postintervention periods were compared using a binomial test, with a P value <0.05 considered significant. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 1679 cases were abstracted to obtain core measure performance in the time period before the DMAIC intervention phase (January 1, 2013May 1, 2013), and 1424 cases were abstracted to obtain core measure performance in the time period after the DMAIC intervention phase (October 1, 2014April 1, 2015).

Overall NMH performance on measures VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) and VTE36 (overlap therapy, platelet monitoring, warfarin discharge instructions, hospital‐acquired [HA]‐VTE) improved significantly (P < 0.05) (Table 1). No improvement was seen on VTE‐2 (intensive care unit chemoprophylaxis) given that pre‐ and postintervention performance was 100%, which likely reflects previous hospital efforts to improve adherence to this measure. The percentage of patients who failed measure VTE‐6 (number of patients with HA‐VTE who did not have VTE prophylaxis ordered prior to diagnosis of their VTE) decreased from 8% to 2.4%, demonstrating improved VTE prevention prescribing habits in NMH providers rather than a change in VTE event rates (ie, if more patients receive prophylaxis, they cannot be included in the numerator). Performance on SCIP‐VTE‐2 (perioperative chemoprophylaxis) increased from 99.5% to 100% as well but did not reach significance given the baseline high performance.

Measure performance on the general surgery services was comparable to the general medical services, with 1 exception. VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) performance was lower both prior to and following the QI intervention on general medicine services (medicine: 82.5% to 90.2% vs surgery: 94.4% to 97.6%). Recent performance on the VTE‐1 proxy measure has proven to be stable between 95% and 97% on surgery services. Physician response to alerts has increased slightly among the NMH general medicine practitioners (15.2%19.1%) but has been stable among NMH general surgery providers.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that a formal DMAIC QI project taken on by a multidisciplinary team (including clinicians from multiple specialties as well as personnel from IT, nursing, analytics, and PI) can be successfully implemented and can result in marked improvement in VTE core process measure performance. We used a multifaceted approach undertaken by the NMH VTE QI team, utilizing 15 data‐driven interventions including EMR alerts, education initiatives, and new EMR order sets. These were combined with strong control mechanisms to sustain gains.

Previously published studies on VTE prophylaxis practices found that projects combining both passive (ie, helping clinicians to remember to risk‐assess their patients' for VTE) and active (ie, assisting clinicians in appropriate prescribing practices) strategies are the most successful.[26] Our improvement on VTE‐1 can be compared to previous studies examining changes in ordering rates of VTE prophylaxis. Other QI projects that featured a combination of interventions observed similar significant increases in prophylaxis ordering.[27, 28] Our improvement on VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) was significant, although the difference between pre‐ and postintervention performance varied by service type (general surgery vs general medicine vs other). The small increment of improvement on surgical services was likely attributable to a high baseline performance. Prior to 2013, surgically focused VTE prophylaxis QI efforts spurred by poor ACS‐NSQIP performance proved to be successful, thus resulting in high surgical prophylaxis rates at the outset of the hospital‐wide VTE DMAIC project.

One of the most significant unanticipated barriers to improving performance on VTE‐1 (chemoprophylaxis) included the different hospital subcultures on the medical floors as compared to the surgical floors. The surgical floors had higher rates of compliance with VTE‐1 than the general medicine floors both before and after the QI interventions. When the root causes were explored, the medical floors were found to have different ordering and administration patterns. These, in part, stemmed from differing guidelines[29] and standards in the literature regarding VTE prophylaxis for medical and surgical patients. Multiple discussions within the multidisciplinary QI team and with each involved department were held, focusing on the data regarding safe care in medical patients at low risk for a VTE. Subsequent EMR alerts alterations reflected the internal medicine VTE prophylaxis recommendations for medical patients, allowing that low‐risk patients could be assessed by the provider and given as a reason for foregoing VTE prophylaxis.

Barriers to VTE prophylaxis administration were encountered on the nursing front as well. Floor observations illustrated that chemoprophylaxis injections were often offered as an optional medication. Patients, when given the choice of receiving an injection or not, would understandably choose to forgo their heparin or enoxaparin shot. This missed dose was then documented as a patient refusal. This may not be a problem unique to NMH; 1 study demonstrated that almost 12% of chemoprophylaxis doses may not be administered, and a frequent reason may be due to patient refusal.[30] The lack of patient education regarding the importance of receiving chemical prophylaxis was an improvement opportunity at both the nursing and physician level. Not only did physicians and nurses take the responsibility to educate patients on the importance of receiving the proper prophylaxis, but nursing managers were made responsible for acting on missed doses that were listed on the real‐time performance reports for their units. Missed prophylaxis doses thus became an actionable item instead of an acceptable occurrence.