User login

Abdominal myomectomy: Patient and surgical technique considerations

CASE Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

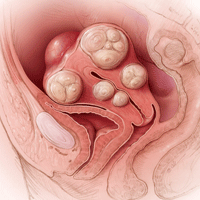

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to the office for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy.

Abdominal myomectomy: A good option for many women

Abdominal myomectomy is an underutilized procedure. With fibroids as the indication for surgery, 197,000 hysterectomies were performed in the United States in 2010, compared with approximately 40,000 myomectomies.1,2 Moreover, the rates of both laparoscopic and abdominal myomectomy have decreased following the controversial morcellation advisory issued by the US Food and Drug Administration.3

The differences in the hysterectomy and myomectomy rates might be explained by the many myths ascribed to myomectomy. Such myths include the beliefs that myomectomy, when compared with hysterectomy, is associated with greater risk of visceral injury, more blood loss, poor uterine healing, and high risk of fibroid recurrence, and that myomectomy is unlikely to improve patient symptoms.

Studies show, however, that these beliefs are wrong. The risk of needing treatment for new fibroid growth following myomectomy is low.4 Hysterectomy, compared with myomectomy for similar size uteri, is actually associated with a greater risk of injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters and with a greater risk of operative hemorrhage. Furthermore, hysterectomy (without oophorectomy) can be associated with early menopause in approximately 10% of women, while myomectomy does not alter ovarian hormones. (See “7 Myomectomy myths debunked,” which appeared in the February 2017 issue of OBG

For women who have serious medical problems (severe anemia, ureteral obstruction) due to uterine fibroids, surgery usually is necessary. In addition, women may request surgery for fibroid-associated quality-of-life concerns, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, or incontinence. In one prospective study, the authors found that when women were assessed 6 months after undergoing myomectomy, 75% reported experiencing a significant decrease in bothersome symptoms.7

Myomectomy may be considered even for women with large uterine fibroids who desire uterine conservation. In a systematic review of the perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy for fibroids, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 16 to 18 weeks, no difference was found in major morbidity rates.8 Investigators who studied 91 women with uterine size ranging from 16 to 36 weeks who underwent abdominal myomectomy reported 1 bowel injury, 1 bladder injury, and 1 reoperation for bowel obstruction; no women had conversion to hysterectomy.9

Since ObGyn residency training emphasizes hysterectomy techniques, many residents receive only limited exposure to myomectomy procedures. Increased exposure to and comfort with myomectomy surgical technique would encourage more gynecologists to offer this option to their patients who desire uterine conservation, including those who do not desire future childbearing.

Imaging techniques are essential in the preoperative evaluation

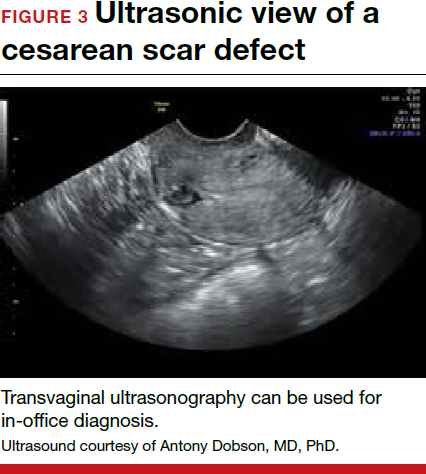

For women with fibroid-related symptoms who desire surgery with uterine preservation, determining the myomectomy approach (abdominal, laparoscopic/robotic, hysteroscopic) depends on accurate assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids. If abdominal myomectomy is planned because of uterine size, the presence of numerous fibroids, or patient choice, transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasonography usually is adequate for anticipating what will be found during surgery. Sonography is readily available and is the least costly imaging technique that can help differentiate fibroids from other pelvic pathology. Although small fibroids may not be seen on sonography, they can be palpated and removed at the time of open surgery.

If submucous fibroids need to be better defined, saline-infusion sonography can be performed. However, if laparoscopic/robotic myomectomy (which precludes accurate palpation during surgery) is being considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows the best assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids.10 When adenomyosis is considered in the differential diagnosis, MRI is an accurate way to determine its presence and helps in planning the best surgical procedure and approach.

Correct anemia before surgery

Women with fibroids may have anemia requiring correction before surgery to reduce the need for intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion. Mild iron deficiency anemia can be treated prior to surgery with oral elemental iron 150 to 200 mg per day. Vitamin C 1,000 mg per day helps to increase intestinal iron absorption. Three weeks of treatment with oral iron can increase hemoglobin concentration by 2 g/dL.

For more severe anemia or rapid correction of anemia, intravenous (IV) iron sucrose infusions, 200 mg infused over 2 hours and given 3 times per week for 3 weeks, can increase hemoglobin by 3 g/dL.11 In our ObGyn practice, hematologists manage iron infusions.

Read about abdominal incision technique

Abdominal incision technique

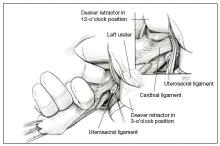

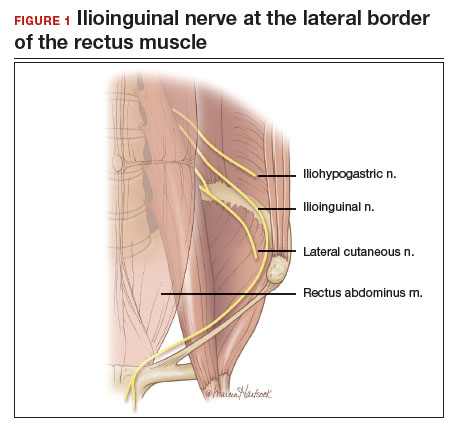

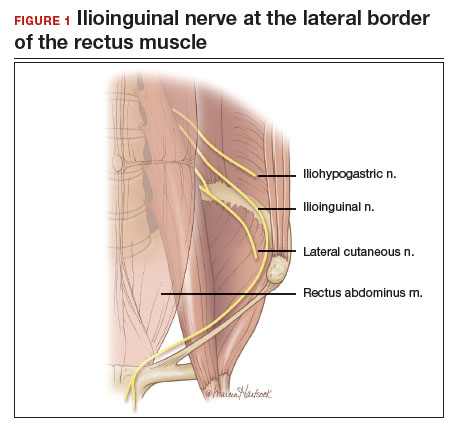

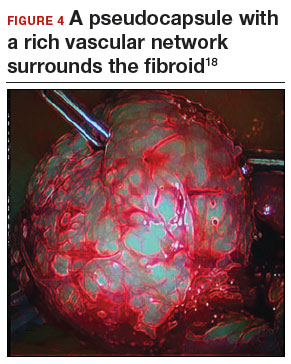

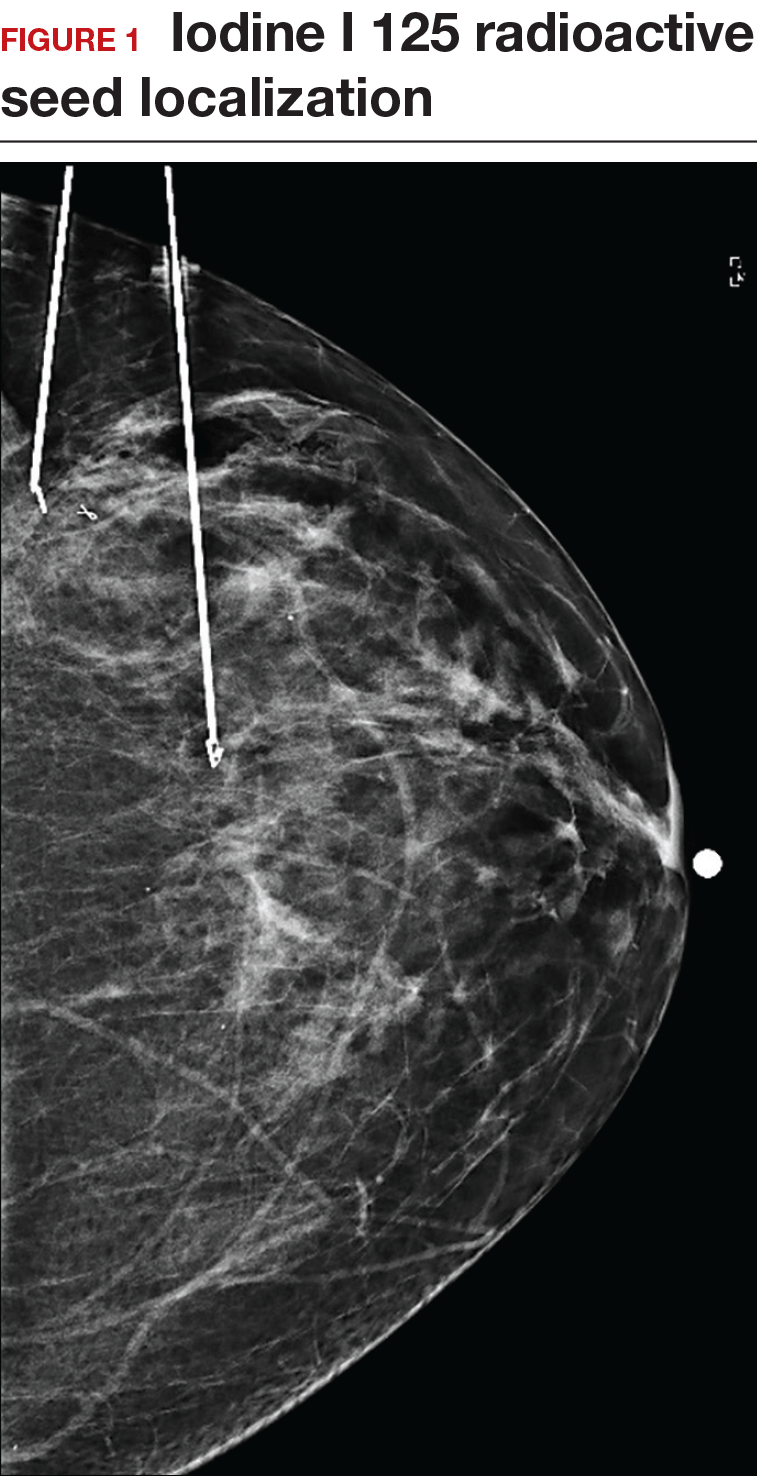

Even a large uterus with multiple fibroids usually can be managed through use of a transverse lower abdominal incision. Prior to reaching the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis, curve the fascial incision cephalad to avoid injury to the ileoinguinal nerves (FIGURE 1). Detaching the midline rectus fascia (linea alba) from the anterior abdominal wall, starting at the pubic symphysis and continuing up to the umbilicus, frees the rectus muscles and allows them to be easily separated (see VIDEO 1). Since fascia is not elastic, these 2 steps are important to allow more room to deliver the uterus through the incision.

Delivery of the uterus through the incision isolates the surgical field from the bowel, bladder, ureters, and pelvic nerves. Once the uterus is delivered, inspect and palpate it for fibroids. Identify the fundus and the position of the uterine cavity by locating both uterine cornua and imagining a straight line between them. It may be necessary to explore the endometrial cavity to look for and remove submucous fibroids. Then plan the necessary uterine incisions for removing all fibroids (see VIDEO 2).

Read about managing blood loss

4 approaches to managing intraoperative blood loss

In my practice, we employ misoprostol, tranexamic acid, vasopressin, and a uterine and ovarian vessel tourniquet to manage intraoperative blood loss.12 Although no data exist to show that using these methods together is advantageous, they have different mechanisms of action and no negative interactions.

Misoprostol 400 μg inserted vaginally 2 hours before surgery induces myometrial contraction and compression of the uterine vessels. This agent can reduce blood loss by 98 mL per case.12

Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, is given IV piggyback at the start of surgery at a dose of 10 mg/kg; it can reduce blood loss by 243 mL per case.12

Vasopressin 20 U in 100 mL normal saline, injected below the vascular pseudocapsule, causes vasoconstriction of capillaries and small arterioles and venules and can reduce blood loss by 246 mL per case.12 Intravascular injection should be avoided because rare cases of bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse have been reported.13 Using vasopressin to decrease blood loss during myomectomy is an off-label use of this drug.

Place a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment, including the infundibular pelvic ligaments. Tourniquet use is the most effective way to decrease blood loss during myomectomy, since it can reduce blood loss by 1,870 mL.12 For women who wish to preserve fertility, take care to ensure that the tourniquet does not compromise the tubes. For women who are certain they do not want to preserve fertility, discuss the possibility of performing bilateral salpingectomy to decrease the risk of subsequent tubal (“ovarian”) cancer.

Some surgeons incise the broad ligaments bilaterally and pass the tourniquet through the broad ligaments to avoid compromising blood flow to the ovaries. Occluding the utero- ovarian ligaments with bulldog clamps to control collateral blood flow from the ovarian artery has been described, but the clamps can tear these often enlarged and fragile uterine veins during manipulation of the uterus. Release the tourniquet every 15 to 30 minutes to allow reperfusion of the ovaries. In women with ovarian torsion lasting hours to days, the ovary has been found to resist hypoxia and recover function.14 Antral follicle counts of detorsed and contralateral normal ovaries following a mean of 13 hours of hypoxia are similar 3 months following detorsion.15

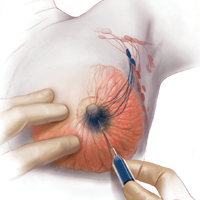

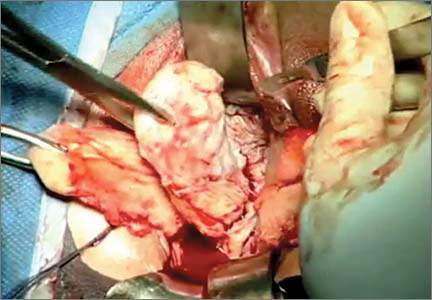

Consider blood salvage. For women with multiple or very large fibroids, consider using a salvage-type autologous blood transfusion device, which has been shown to reduce the need for heterologous blood transfusion.16 This device suctions blood from the operative field, mixes it with heparinized saline, and stores the blood in a canister (FIGURE 2). If the patient requires blood reinfusion, the stored blood is washed with saline, filtered, centrifuged, and given back to the patient intravenously. Blood salvage, or cell salvage, avoids the risks of infection and transfusion reaction, and the oxygen transport capacity of salvaged red blood cells is equal to or better than that of stored allogeneic red cells.

Additional surgical considerations

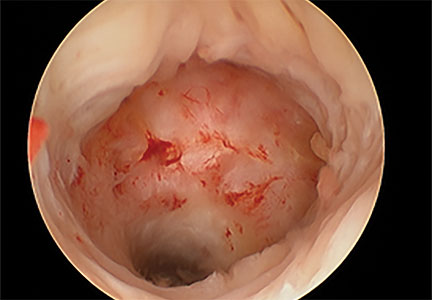

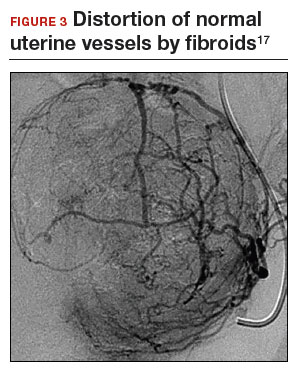

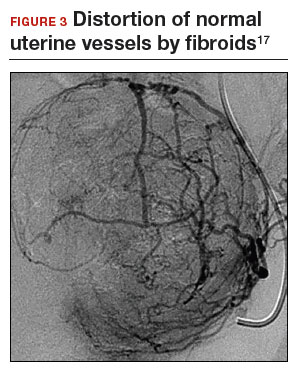

Previous teaching suggested that proper placement of the uterine incisions was an important factor in limiting blood loss. Some authors suggested that vertical uterine incisions would avoid injury to the ascending uterine vessels should inadvertent extension of the incision occur. Other authors proposed horizontal uterine incisions to avoid severing the arcuate vessels that branch off from the ascending uterine arteries and run transversely across the uterus. However, since fibroids distort the normal vascular architecture, it is not possible to entirely avoid severing vessels in the myometrium (FIGURE 3).17 Uterine incisions can therefore be made as needed based on the position of the fibroids and the need to avoid inadvertent extension to the ascending uterine vessels or cornua.17

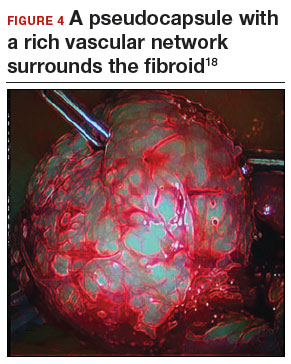

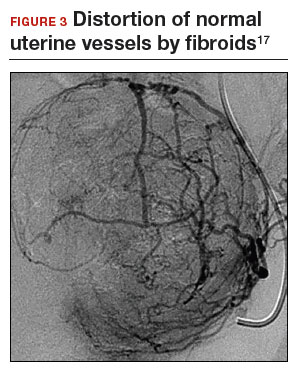

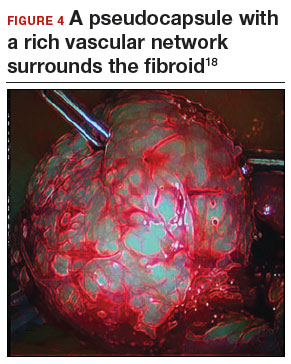

Fibroid anatomy and vascularity. Fibroids are entirely encased within the dense blood supply of a pseudocapsule (FIGURE 4),18 and no distinct “vascular pedicle” exists at the base of the fibroid.19 It is therefore important to extend the uterine incisions down through the entire pseudocapsule until the fibroid is clearly visible. This will identify a less vascular surgical plane, which is deeper than commonly recognized. Once the fibroid is reached, the pseudocapsule can be “wiped away” using a dry laparotomy sponge (see VIDEO 3). Staying under the pseudocapsule reduces bleeding and may preserve the tissue growth factors and neurotransmitters that are thought to promote wound healing.20

Adhesion prevention. Limiting the number of uterine incisions has been suggested as a way to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic adhesions. To extract fibroids that are distant from an incision, however, tunnels must be created within the myometrium, and this makes hemostasis within these defects difficult. In that blood increases the risk of adhesion formation, tunneling may be counterproductive. If tunneling incisions are avoided and hemostasis is secured immediately, the risk of adhesion formation should be lessened.

Therefore, make incisions directly over the fibroids. Remove only easily accessed fibroids and promptly close the defects to secure hemostasis. Multiple uterine incisions may be needed; adhesion barriers may help limit adhesion formation.21

On final removal of the tourniquet, carefully inspect for bleeding and perform any necessary re-suturing. We place a pain pump (ON-Q* Pain Relief System, Halyard Health, Inc) for pain management and close the abdominal incision in the standard manner.

Postoperative care: Manage pain, restore function

The pain pump infuser, attached to one soaker catheter above and one below the fascia, provides continuous infusion of bupivacaine to the incision at 4 mL per hour for 4 days. The pain pump greatly reduces the need for postoperative opioids.22 Use of a patient-controlled analgesia pump, with its associated adverse effects (sedation, need for oxygen saturation monitoring, slowing of bowel function) can thus be avoided. The patient’s residual pain is controlled with oral oxycodone or hydrocodone and scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In my practice, we use an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol designed to reduce postoperative surgical stress and expedite a return to baseline physiologic body functions.23 Excellent well-researched, evidence-based studies support the effectiveness of ERAS in gynecologic and general surgery procedures.24

Pre-emptive, preoperative analgesia (gabapentin and celecoxib) and end-of-case IV acetaminophen are given to reduce the inflammatory response and the need for postoperative opioids. Once it is confirmed that the patient is hemodynamically stable, add ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours on postoperative day 1. Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis includes ondansetron and dexamethasone at the end of surgery, avoidance of bowel edema with restriction of intraoperative and postoperative fluids (euvolemia), early oral feeding, and gum chewing. On the evening of surgery, the urinary catheter is removed to reduce the risk of bladder infection and facilitate ambulation. Encourage sitting at the bedside and early ambulation starting the evening of surgery to reduce risk of thromboembolism and to avoid skeletal muscle weakness and postoperative fatigue.

Most women are able to be discharged on postoperative day 2. They return to the office on postoperative day 5 for removal of the pain pump.

CASE Continued: Fibroids removed via abdominal myomectomy

We performed an abdominal myomectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. Nine fibroids—3 of which were not seen on MRI—ranging in size from 1 to 7 cm were removed. Intravaginal misoprostol, IV tranexamic acid, subserosal vasopressin, and a uterine vessel tourniquet limited the intraoperative blood loss to 225 mL. After surgery, a pain pump and ERAS protocol allowed the patient to be discharged on postoperative day 2, and she returned to the office on day 5 for removal of the pain pump. Oral pain medication was continued on an as-needed basis.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Stanley West, MD, for generously teaching him the surgical techniques for performing abdominal myomectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

- Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Stocks C, Steiner CA, Myers ER. Statistical brief 200. Procedures to treat benign uterine fibroids in hospital inpatient and hospital-based ambulatory surgery settings, 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb200-Procedures-Treat-Uterine-Fibroids.jsp. Published January 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- Stentz NC, Cooney L, Sammel MD, Shah DK. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) safety communication on morcellation on surgical practice and perioperative morbidity following myomectomy [abstract p300]. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3 suppl):e219.

- Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(4):539–543.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek JS, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Bogani G, Cliby WA, Aletti GD. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167–172.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- West S, Ruiz R, Parker WH. Abdominal myomectomy in women with very large uterine size. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):36–39.

- Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(2):350–357.

- Kim YH, Chung HH, Kang SB, Kim SC, Kim YT. Safety and usefulness of intravenous iron sucrose in the management of preoperative anemia in patients with menorrhagia: a phase IV, open-label, prospective, randomized study. Acta Haematol. 2009;121(1):37–41.

- Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS. Interventions to reduce haemorrhage during myomectomy for fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 15;(8):CD005355.

- Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):484–486.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, Admon D, Mashiach S, Carp H. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2599–2602.

- Yasa C, Dural O, Bastu E, Zorlu M, Demir O, Ugurlucan FG. Impact of laparoscopic ovarian detorsion on ovarian reserve. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(2):298–302.

- Yamada T, Ikeda A, Okamoto Y, Okamoto Y, Kanda T, Ueki M. Intraoperative blood salvage in abdominal simple total hysterectomy for uterine myoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):233–236.

- Discepola F, Valenti DA, Reinhold C, Tulandi T. Analysis of arterial blood vessels surrounding the myoma: relevance to myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1301–1303.

- Malavasi A, Cavalotti C, Nicolardi G, et al. The opioid neuropeptides in uterine fibroid pseudocapsules: a putative association with cervical integrity in human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(11):982–988.

- Walocha JA, Litwin JA, Miodonski AJ. Vascular system of intramural leiomyomata revealed by corrosion casting and scanning electron microscopy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):1088–1093.

- Tinelli A, Mynbaev OA, Sparic R, et al. Angiogenesis and vascularization of uterine leiomyoma: clinical value of pseudocapsule containing peptides and neurotransmitters [published online ahead of print March 22, 2016]. Curr Protein Pept Sci. doi:10.2174/1389203717666160322150338.

- Diamond MP. Reduction of adhesions after uterine myomectomy by Seprafilm membrane (HAL-F): a blinded, prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical study. Seprafilm Adhesion Study Group. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(6):904–910.

- Liu SS, Richman JM, Thirlby RC, Wu CL. Efficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):914–932.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):319–328.

CASE Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to the office for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy.

Abdominal myomectomy: A good option for many women

Abdominal myomectomy is an underutilized procedure. With fibroids as the indication for surgery, 197,000 hysterectomies were performed in the United States in 2010, compared with approximately 40,000 myomectomies.1,2 Moreover, the rates of both laparoscopic and abdominal myomectomy have decreased following the controversial morcellation advisory issued by the US Food and Drug Administration.3

The differences in the hysterectomy and myomectomy rates might be explained by the many myths ascribed to myomectomy. Such myths include the beliefs that myomectomy, when compared with hysterectomy, is associated with greater risk of visceral injury, more blood loss, poor uterine healing, and high risk of fibroid recurrence, and that myomectomy is unlikely to improve patient symptoms.

Studies show, however, that these beliefs are wrong. The risk of needing treatment for new fibroid growth following myomectomy is low.4 Hysterectomy, compared with myomectomy for similar size uteri, is actually associated with a greater risk of injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters and with a greater risk of operative hemorrhage. Furthermore, hysterectomy (without oophorectomy) can be associated with early menopause in approximately 10% of women, while myomectomy does not alter ovarian hormones. (See “7 Myomectomy myths debunked,” which appeared in the February 2017 issue of OBG

For women who have serious medical problems (severe anemia, ureteral obstruction) due to uterine fibroids, surgery usually is necessary. In addition, women may request surgery for fibroid-associated quality-of-life concerns, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, or incontinence. In one prospective study, the authors found that when women were assessed 6 months after undergoing myomectomy, 75% reported experiencing a significant decrease in bothersome symptoms.7

Myomectomy may be considered even for women with large uterine fibroids who desire uterine conservation. In a systematic review of the perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy for fibroids, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 16 to 18 weeks, no difference was found in major morbidity rates.8 Investigators who studied 91 women with uterine size ranging from 16 to 36 weeks who underwent abdominal myomectomy reported 1 bowel injury, 1 bladder injury, and 1 reoperation for bowel obstruction; no women had conversion to hysterectomy.9

Since ObGyn residency training emphasizes hysterectomy techniques, many residents receive only limited exposure to myomectomy procedures. Increased exposure to and comfort with myomectomy surgical technique would encourage more gynecologists to offer this option to their patients who desire uterine conservation, including those who do not desire future childbearing.

Imaging techniques are essential in the preoperative evaluation

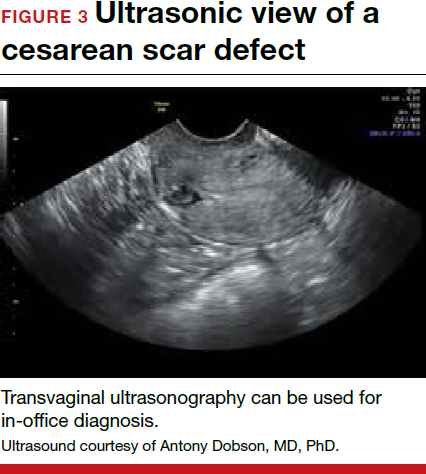

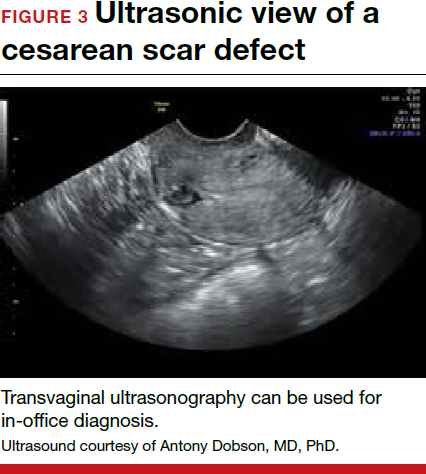

For women with fibroid-related symptoms who desire surgery with uterine preservation, determining the myomectomy approach (abdominal, laparoscopic/robotic, hysteroscopic) depends on accurate assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids. If abdominal myomectomy is planned because of uterine size, the presence of numerous fibroids, or patient choice, transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasonography usually is adequate for anticipating what will be found during surgery. Sonography is readily available and is the least costly imaging technique that can help differentiate fibroids from other pelvic pathology. Although small fibroids may not be seen on sonography, they can be palpated and removed at the time of open surgery.

If submucous fibroids need to be better defined, saline-infusion sonography can be performed. However, if laparoscopic/robotic myomectomy (which precludes accurate palpation during surgery) is being considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows the best assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids.10 When adenomyosis is considered in the differential diagnosis, MRI is an accurate way to determine its presence and helps in planning the best surgical procedure and approach.

Correct anemia before surgery

Women with fibroids may have anemia requiring correction before surgery to reduce the need for intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion. Mild iron deficiency anemia can be treated prior to surgery with oral elemental iron 150 to 200 mg per day. Vitamin C 1,000 mg per day helps to increase intestinal iron absorption. Three weeks of treatment with oral iron can increase hemoglobin concentration by 2 g/dL.

For more severe anemia or rapid correction of anemia, intravenous (IV) iron sucrose infusions, 200 mg infused over 2 hours and given 3 times per week for 3 weeks, can increase hemoglobin by 3 g/dL.11 In our ObGyn practice, hematologists manage iron infusions.

Read about abdominal incision technique

Abdominal incision technique

Even a large uterus with multiple fibroids usually can be managed through use of a transverse lower abdominal incision. Prior to reaching the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis, curve the fascial incision cephalad to avoid injury to the ileoinguinal nerves (FIGURE 1). Detaching the midline rectus fascia (linea alba) from the anterior abdominal wall, starting at the pubic symphysis and continuing up to the umbilicus, frees the rectus muscles and allows them to be easily separated (see VIDEO 1). Since fascia is not elastic, these 2 steps are important to allow more room to deliver the uterus through the incision.

Delivery of the uterus through the incision isolates the surgical field from the bowel, bladder, ureters, and pelvic nerves. Once the uterus is delivered, inspect and palpate it for fibroids. Identify the fundus and the position of the uterine cavity by locating both uterine cornua and imagining a straight line between them. It may be necessary to explore the endometrial cavity to look for and remove submucous fibroids. Then plan the necessary uterine incisions for removing all fibroids (see VIDEO 2).

Read about managing blood loss

4 approaches to managing intraoperative blood loss

In my practice, we employ misoprostol, tranexamic acid, vasopressin, and a uterine and ovarian vessel tourniquet to manage intraoperative blood loss.12 Although no data exist to show that using these methods together is advantageous, they have different mechanisms of action and no negative interactions.

Misoprostol 400 μg inserted vaginally 2 hours before surgery induces myometrial contraction and compression of the uterine vessels. This agent can reduce blood loss by 98 mL per case.12

Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, is given IV piggyback at the start of surgery at a dose of 10 mg/kg; it can reduce blood loss by 243 mL per case.12

Vasopressin 20 U in 100 mL normal saline, injected below the vascular pseudocapsule, causes vasoconstriction of capillaries and small arterioles and venules and can reduce blood loss by 246 mL per case.12 Intravascular injection should be avoided because rare cases of bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse have been reported.13 Using vasopressin to decrease blood loss during myomectomy is an off-label use of this drug.

Place a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment, including the infundibular pelvic ligaments. Tourniquet use is the most effective way to decrease blood loss during myomectomy, since it can reduce blood loss by 1,870 mL.12 For women who wish to preserve fertility, take care to ensure that the tourniquet does not compromise the tubes. For women who are certain they do not want to preserve fertility, discuss the possibility of performing bilateral salpingectomy to decrease the risk of subsequent tubal (“ovarian”) cancer.

Some surgeons incise the broad ligaments bilaterally and pass the tourniquet through the broad ligaments to avoid compromising blood flow to the ovaries. Occluding the utero- ovarian ligaments with bulldog clamps to control collateral blood flow from the ovarian artery has been described, but the clamps can tear these often enlarged and fragile uterine veins during manipulation of the uterus. Release the tourniquet every 15 to 30 minutes to allow reperfusion of the ovaries. In women with ovarian torsion lasting hours to days, the ovary has been found to resist hypoxia and recover function.14 Antral follicle counts of detorsed and contralateral normal ovaries following a mean of 13 hours of hypoxia are similar 3 months following detorsion.15

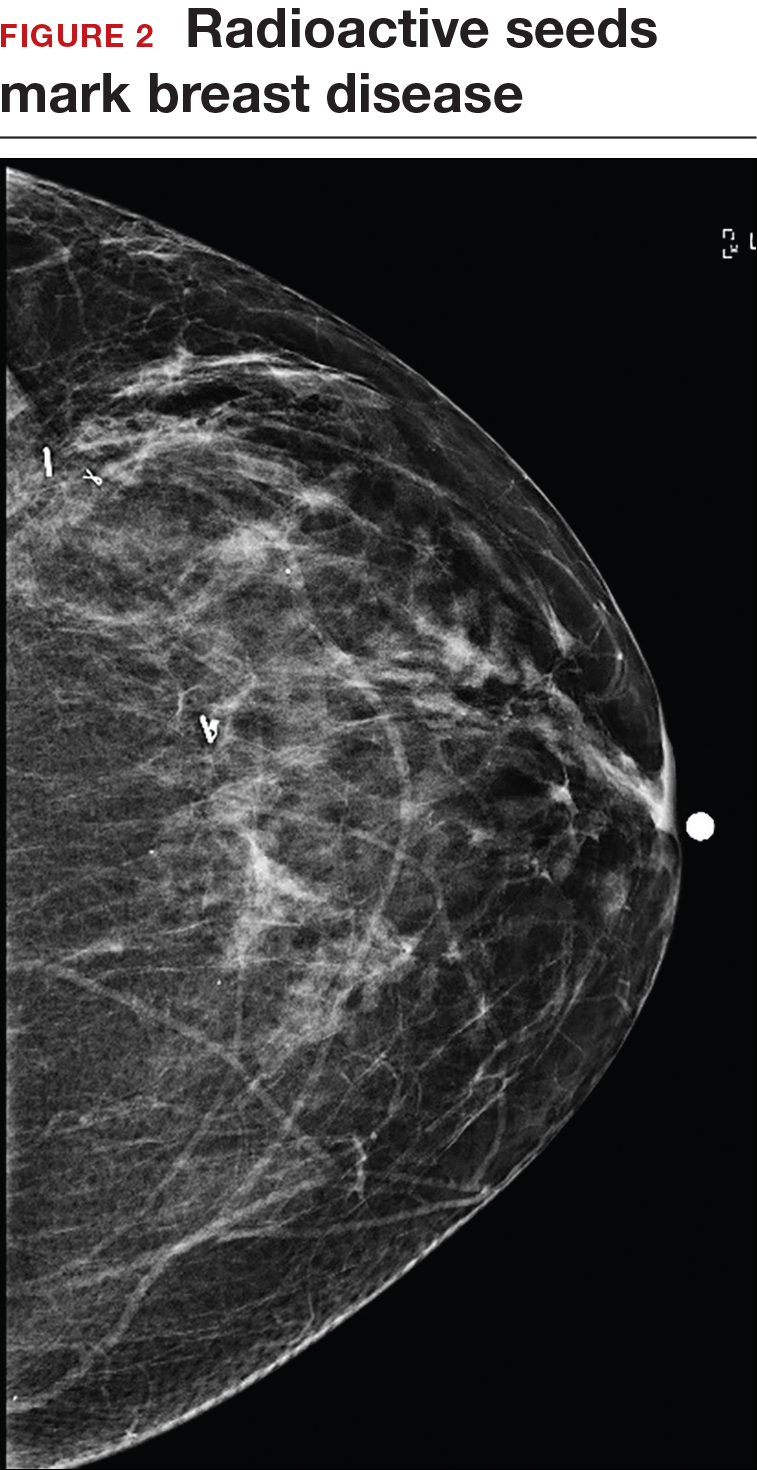

Consider blood salvage. For women with multiple or very large fibroids, consider using a salvage-type autologous blood transfusion device, which has been shown to reduce the need for heterologous blood transfusion.16 This device suctions blood from the operative field, mixes it with heparinized saline, and stores the blood in a canister (FIGURE 2). If the patient requires blood reinfusion, the stored blood is washed with saline, filtered, centrifuged, and given back to the patient intravenously. Blood salvage, or cell salvage, avoids the risks of infection and transfusion reaction, and the oxygen transport capacity of salvaged red blood cells is equal to or better than that of stored allogeneic red cells.

Additional surgical considerations

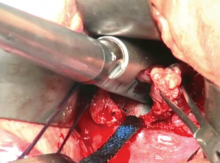

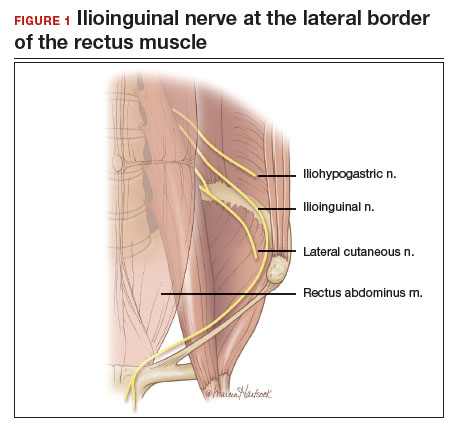

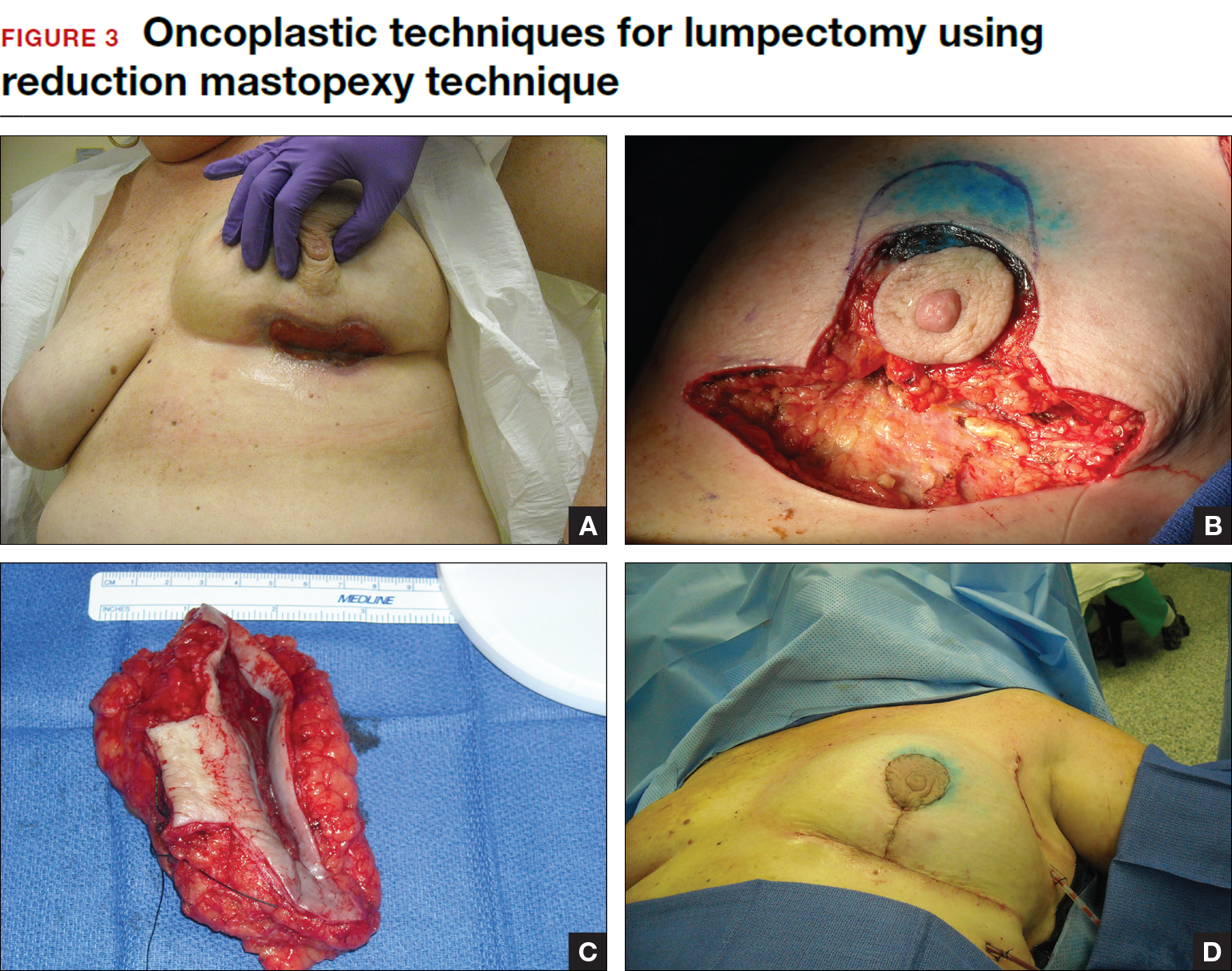

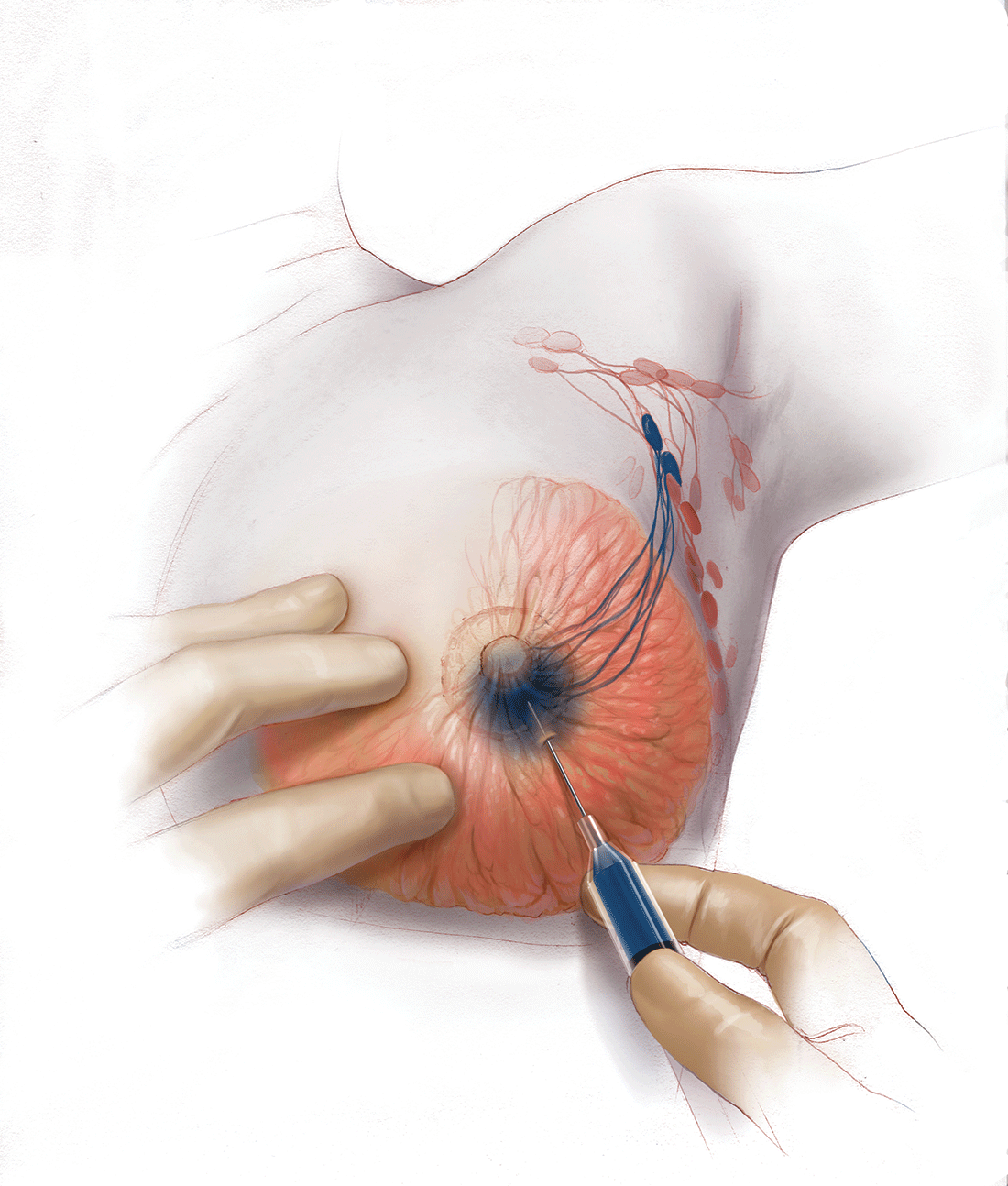

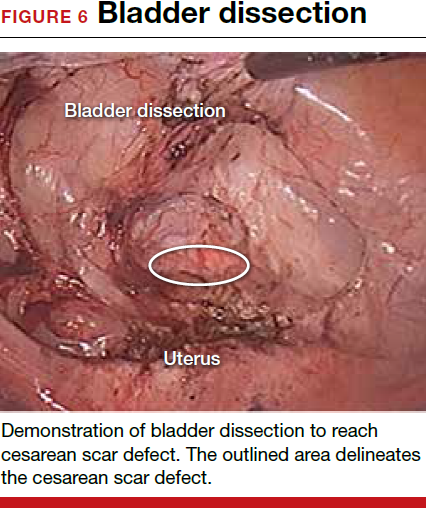

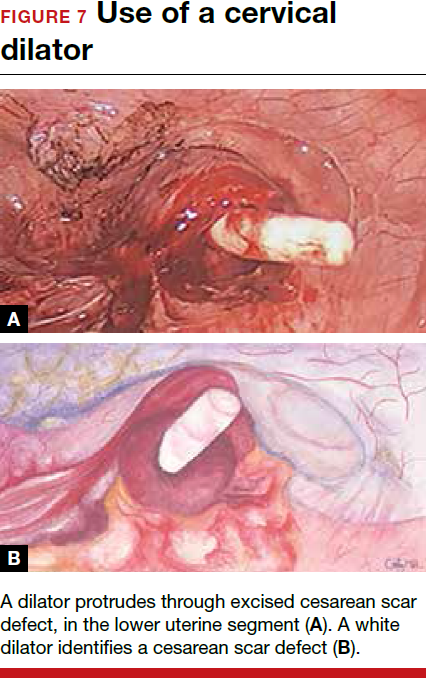

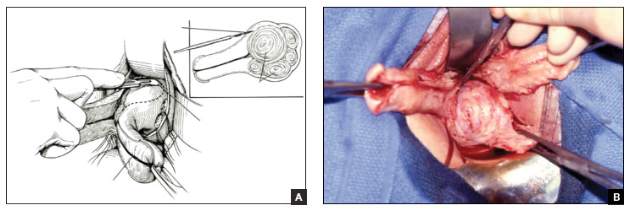

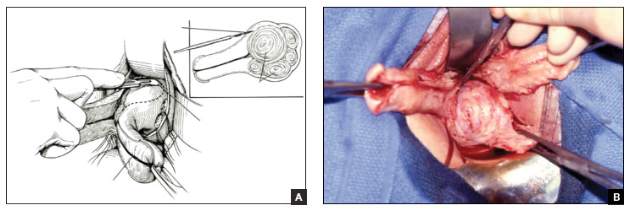

Previous teaching suggested that proper placement of the uterine incisions was an important factor in limiting blood loss. Some authors suggested that vertical uterine incisions would avoid injury to the ascending uterine vessels should inadvertent extension of the incision occur. Other authors proposed horizontal uterine incisions to avoid severing the arcuate vessels that branch off from the ascending uterine arteries and run transversely across the uterus. However, since fibroids distort the normal vascular architecture, it is not possible to entirely avoid severing vessels in the myometrium (FIGURE 3).17 Uterine incisions can therefore be made as needed based on the position of the fibroids and the need to avoid inadvertent extension to the ascending uterine vessels or cornua.17

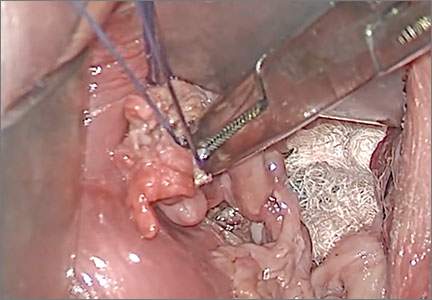

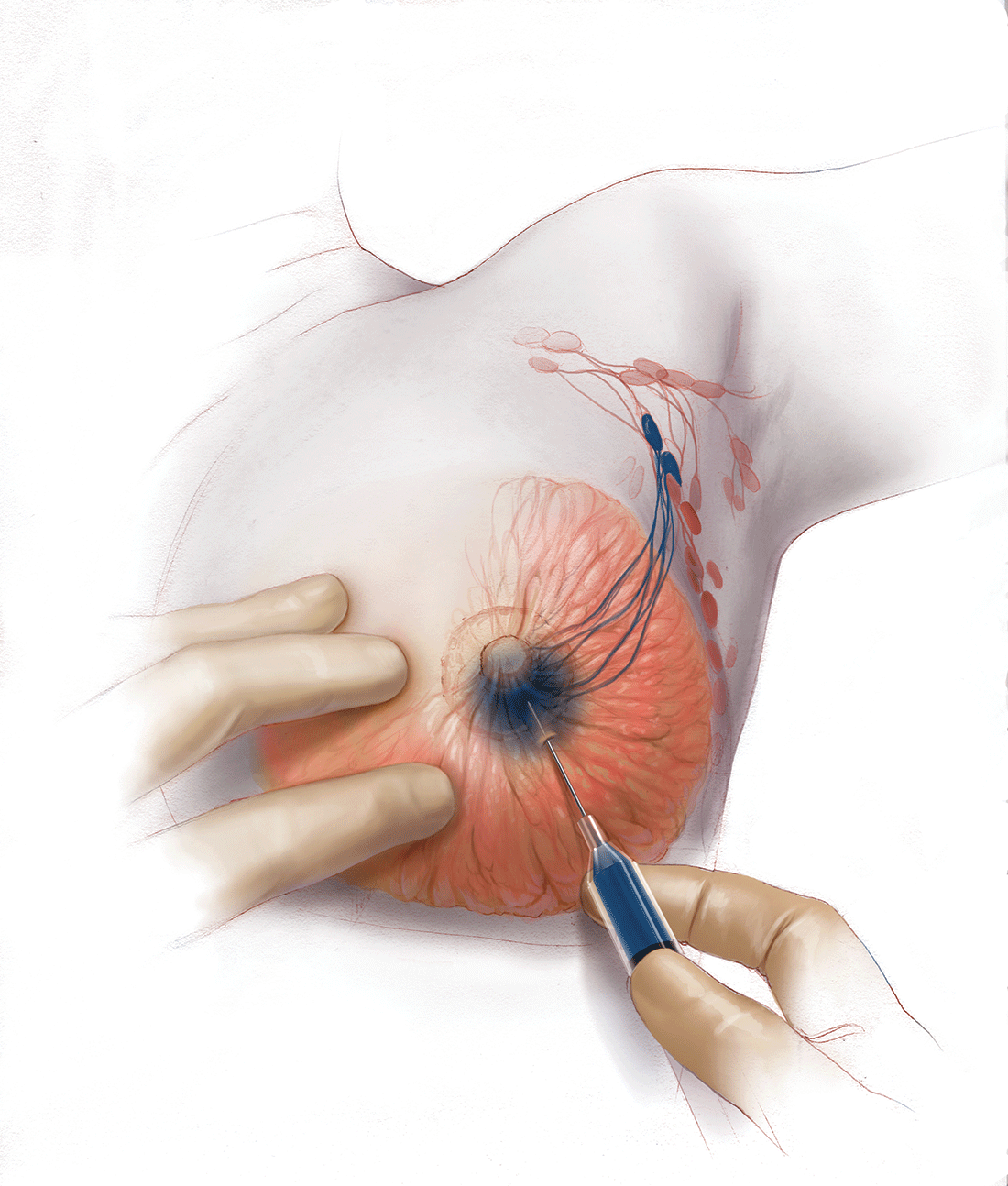

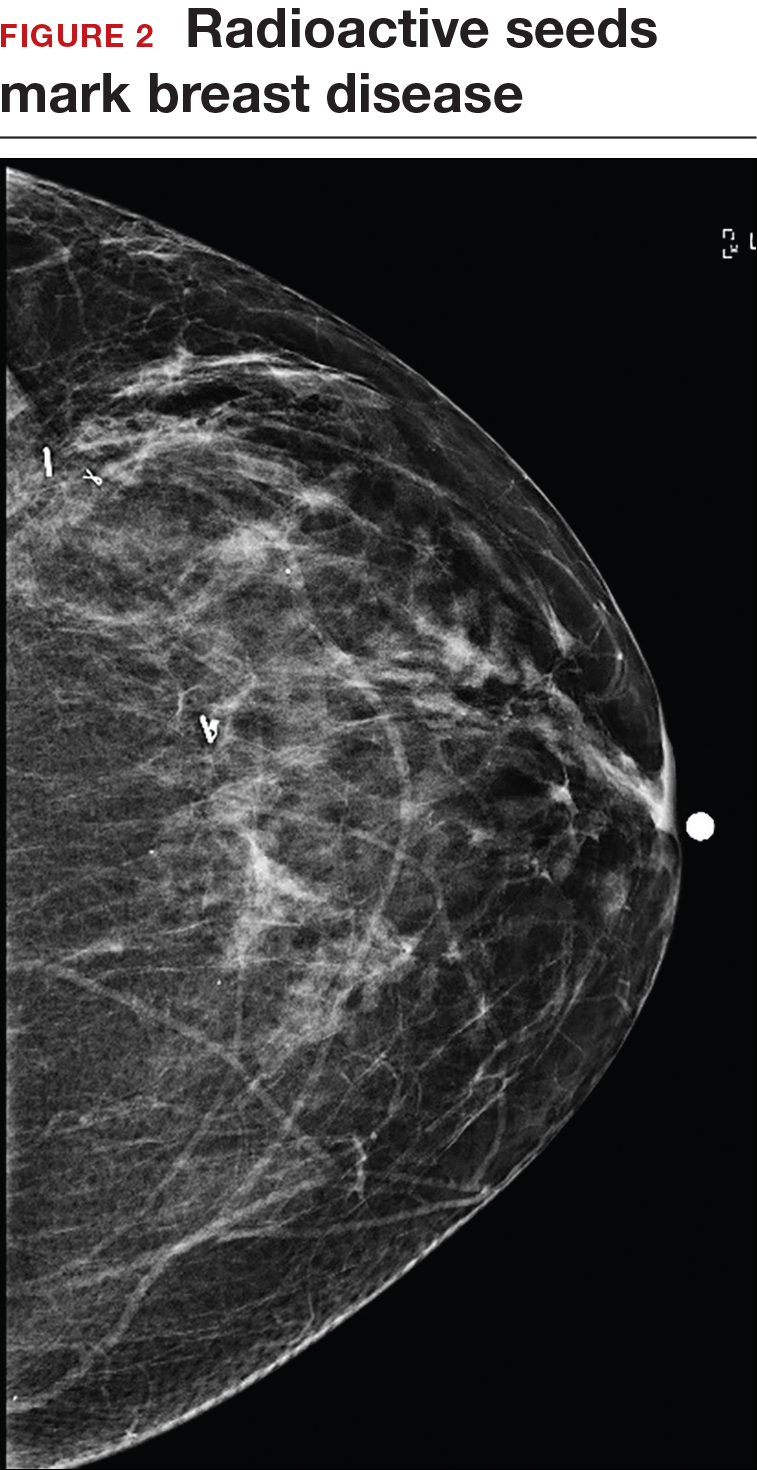

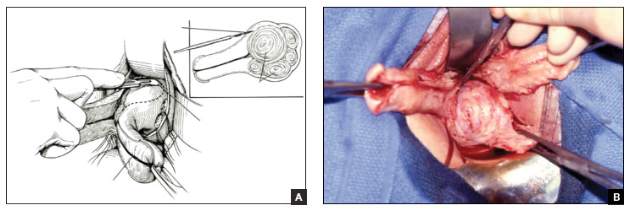

Fibroid anatomy and vascularity. Fibroids are entirely encased within the dense blood supply of a pseudocapsule (FIGURE 4),18 and no distinct “vascular pedicle” exists at the base of the fibroid.19 It is therefore important to extend the uterine incisions down through the entire pseudocapsule until the fibroid is clearly visible. This will identify a less vascular surgical plane, which is deeper than commonly recognized. Once the fibroid is reached, the pseudocapsule can be “wiped away” using a dry laparotomy sponge (see VIDEO 3). Staying under the pseudocapsule reduces bleeding and may preserve the tissue growth factors and neurotransmitters that are thought to promote wound healing.20

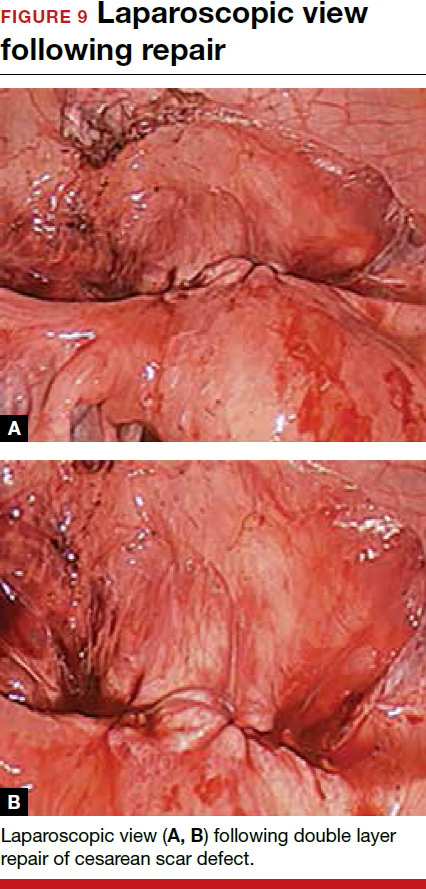

Adhesion prevention. Limiting the number of uterine incisions has been suggested as a way to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic adhesions. To extract fibroids that are distant from an incision, however, tunnels must be created within the myometrium, and this makes hemostasis within these defects difficult. In that blood increases the risk of adhesion formation, tunneling may be counterproductive. If tunneling incisions are avoided and hemostasis is secured immediately, the risk of adhesion formation should be lessened.

Therefore, make incisions directly over the fibroids. Remove only easily accessed fibroids and promptly close the defects to secure hemostasis. Multiple uterine incisions may be needed; adhesion barriers may help limit adhesion formation.21

On final removal of the tourniquet, carefully inspect for bleeding and perform any necessary re-suturing. We place a pain pump (ON-Q* Pain Relief System, Halyard Health, Inc) for pain management and close the abdominal incision in the standard manner.

Postoperative care: Manage pain, restore function

The pain pump infuser, attached to one soaker catheter above and one below the fascia, provides continuous infusion of bupivacaine to the incision at 4 mL per hour for 4 days. The pain pump greatly reduces the need for postoperative opioids.22 Use of a patient-controlled analgesia pump, with its associated adverse effects (sedation, need for oxygen saturation monitoring, slowing of bowel function) can thus be avoided. The patient’s residual pain is controlled with oral oxycodone or hydrocodone and scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In my practice, we use an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol designed to reduce postoperative surgical stress and expedite a return to baseline physiologic body functions.23 Excellent well-researched, evidence-based studies support the effectiveness of ERAS in gynecologic and general surgery procedures.24

Pre-emptive, preoperative analgesia (gabapentin and celecoxib) and end-of-case IV acetaminophen are given to reduce the inflammatory response and the need for postoperative opioids. Once it is confirmed that the patient is hemodynamically stable, add ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours on postoperative day 1. Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis includes ondansetron and dexamethasone at the end of surgery, avoidance of bowel edema with restriction of intraoperative and postoperative fluids (euvolemia), early oral feeding, and gum chewing. On the evening of surgery, the urinary catheter is removed to reduce the risk of bladder infection and facilitate ambulation. Encourage sitting at the bedside and early ambulation starting the evening of surgery to reduce risk of thromboembolism and to avoid skeletal muscle weakness and postoperative fatigue.

Most women are able to be discharged on postoperative day 2. They return to the office on postoperative day 5 for removal of the pain pump.

CASE Continued: Fibroids removed via abdominal myomectomy

We performed an abdominal myomectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. Nine fibroids—3 of which were not seen on MRI—ranging in size from 1 to 7 cm were removed. Intravaginal misoprostol, IV tranexamic acid, subserosal vasopressin, and a uterine vessel tourniquet limited the intraoperative blood loss to 225 mL. After surgery, a pain pump and ERAS protocol allowed the patient to be discharged on postoperative day 2, and she returned to the office on day 5 for removal of the pain pump. Oral pain medication was continued on an as-needed basis.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Stanley West, MD, for generously teaching him the surgical techniques for performing abdominal myomectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to the office for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy.

Abdominal myomectomy: A good option for many women

Abdominal myomectomy is an underutilized procedure. With fibroids as the indication for surgery, 197,000 hysterectomies were performed in the United States in 2010, compared with approximately 40,000 myomectomies.1,2 Moreover, the rates of both laparoscopic and abdominal myomectomy have decreased following the controversial morcellation advisory issued by the US Food and Drug Administration.3

The differences in the hysterectomy and myomectomy rates might be explained by the many myths ascribed to myomectomy. Such myths include the beliefs that myomectomy, when compared with hysterectomy, is associated with greater risk of visceral injury, more blood loss, poor uterine healing, and high risk of fibroid recurrence, and that myomectomy is unlikely to improve patient symptoms.

Studies show, however, that these beliefs are wrong. The risk of needing treatment for new fibroid growth following myomectomy is low.4 Hysterectomy, compared with myomectomy for similar size uteri, is actually associated with a greater risk of injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters and with a greater risk of operative hemorrhage. Furthermore, hysterectomy (without oophorectomy) can be associated with early menopause in approximately 10% of women, while myomectomy does not alter ovarian hormones. (See “7 Myomectomy myths debunked,” which appeared in the February 2017 issue of OBG

For women who have serious medical problems (severe anemia, ureteral obstruction) due to uterine fibroids, surgery usually is necessary. In addition, women may request surgery for fibroid-associated quality-of-life concerns, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, or incontinence. In one prospective study, the authors found that when women were assessed 6 months after undergoing myomectomy, 75% reported experiencing a significant decrease in bothersome symptoms.7

Myomectomy may be considered even for women with large uterine fibroids who desire uterine conservation. In a systematic review of the perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy for fibroids, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 16 to 18 weeks, no difference was found in major morbidity rates.8 Investigators who studied 91 women with uterine size ranging from 16 to 36 weeks who underwent abdominal myomectomy reported 1 bowel injury, 1 bladder injury, and 1 reoperation for bowel obstruction; no women had conversion to hysterectomy.9

Since ObGyn residency training emphasizes hysterectomy techniques, many residents receive only limited exposure to myomectomy procedures. Increased exposure to and comfort with myomectomy surgical technique would encourage more gynecologists to offer this option to their patients who desire uterine conservation, including those who do not desire future childbearing.

Imaging techniques are essential in the preoperative evaluation

For women with fibroid-related symptoms who desire surgery with uterine preservation, determining the myomectomy approach (abdominal, laparoscopic/robotic, hysteroscopic) depends on accurate assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids. If abdominal myomectomy is planned because of uterine size, the presence of numerous fibroids, or patient choice, transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasonography usually is adequate for anticipating what will be found during surgery. Sonography is readily available and is the least costly imaging technique that can help differentiate fibroids from other pelvic pathology. Although small fibroids may not be seen on sonography, they can be palpated and removed at the time of open surgery.

If submucous fibroids need to be better defined, saline-infusion sonography can be performed. However, if laparoscopic/robotic myomectomy (which precludes accurate palpation during surgery) is being considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows the best assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids.10 When adenomyosis is considered in the differential diagnosis, MRI is an accurate way to determine its presence and helps in planning the best surgical procedure and approach.

Correct anemia before surgery

Women with fibroids may have anemia requiring correction before surgery to reduce the need for intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion. Mild iron deficiency anemia can be treated prior to surgery with oral elemental iron 150 to 200 mg per day. Vitamin C 1,000 mg per day helps to increase intestinal iron absorption. Three weeks of treatment with oral iron can increase hemoglobin concentration by 2 g/dL.

For more severe anemia or rapid correction of anemia, intravenous (IV) iron sucrose infusions, 200 mg infused over 2 hours and given 3 times per week for 3 weeks, can increase hemoglobin by 3 g/dL.11 In our ObGyn practice, hematologists manage iron infusions.

Read about abdominal incision technique

Abdominal incision technique

Even a large uterus with multiple fibroids usually can be managed through use of a transverse lower abdominal incision. Prior to reaching the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis, curve the fascial incision cephalad to avoid injury to the ileoinguinal nerves (FIGURE 1). Detaching the midline rectus fascia (linea alba) from the anterior abdominal wall, starting at the pubic symphysis and continuing up to the umbilicus, frees the rectus muscles and allows them to be easily separated (see VIDEO 1). Since fascia is not elastic, these 2 steps are important to allow more room to deliver the uterus through the incision.

Delivery of the uterus through the incision isolates the surgical field from the bowel, bladder, ureters, and pelvic nerves. Once the uterus is delivered, inspect and palpate it for fibroids. Identify the fundus and the position of the uterine cavity by locating both uterine cornua and imagining a straight line between them. It may be necessary to explore the endometrial cavity to look for and remove submucous fibroids. Then plan the necessary uterine incisions for removing all fibroids (see VIDEO 2).

Read about managing blood loss

4 approaches to managing intraoperative blood loss

In my practice, we employ misoprostol, tranexamic acid, vasopressin, and a uterine and ovarian vessel tourniquet to manage intraoperative blood loss.12 Although no data exist to show that using these methods together is advantageous, they have different mechanisms of action and no negative interactions.

Misoprostol 400 μg inserted vaginally 2 hours before surgery induces myometrial contraction and compression of the uterine vessels. This agent can reduce blood loss by 98 mL per case.12

Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, is given IV piggyback at the start of surgery at a dose of 10 mg/kg; it can reduce blood loss by 243 mL per case.12

Vasopressin 20 U in 100 mL normal saline, injected below the vascular pseudocapsule, causes vasoconstriction of capillaries and small arterioles and venules and can reduce blood loss by 246 mL per case.12 Intravascular injection should be avoided because rare cases of bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse have been reported.13 Using vasopressin to decrease blood loss during myomectomy is an off-label use of this drug.

Place a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment, including the infundibular pelvic ligaments. Tourniquet use is the most effective way to decrease blood loss during myomectomy, since it can reduce blood loss by 1,870 mL.12 For women who wish to preserve fertility, take care to ensure that the tourniquet does not compromise the tubes. For women who are certain they do not want to preserve fertility, discuss the possibility of performing bilateral salpingectomy to decrease the risk of subsequent tubal (“ovarian”) cancer.

Some surgeons incise the broad ligaments bilaterally and pass the tourniquet through the broad ligaments to avoid compromising blood flow to the ovaries. Occluding the utero- ovarian ligaments with bulldog clamps to control collateral blood flow from the ovarian artery has been described, but the clamps can tear these often enlarged and fragile uterine veins during manipulation of the uterus. Release the tourniquet every 15 to 30 minutes to allow reperfusion of the ovaries. In women with ovarian torsion lasting hours to days, the ovary has been found to resist hypoxia and recover function.14 Antral follicle counts of detorsed and contralateral normal ovaries following a mean of 13 hours of hypoxia are similar 3 months following detorsion.15

Consider blood salvage. For women with multiple or very large fibroids, consider using a salvage-type autologous blood transfusion device, which has been shown to reduce the need for heterologous blood transfusion.16 This device suctions blood from the operative field, mixes it with heparinized saline, and stores the blood in a canister (FIGURE 2). If the patient requires blood reinfusion, the stored blood is washed with saline, filtered, centrifuged, and given back to the patient intravenously. Blood salvage, or cell salvage, avoids the risks of infection and transfusion reaction, and the oxygen transport capacity of salvaged red blood cells is equal to or better than that of stored allogeneic red cells.

Additional surgical considerations

Previous teaching suggested that proper placement of the uterine incisions was an important factor in limiting blood loss. Some authors suggested that vertical uterine incisions would avoid injury to the ascending uterine vessels should inadvertent extension of the incision occur. Other authors proposed horizontal uterine incisions to avoid severing the arcuate vessels that branch off from the ascending uterine arteries and run transversely across the uterus. However, since fibroids distort the normal vascular architecture, it is not possible to entirely avoid severing vessels in the myometrium (FIGURE 3).17 Uterine incisions can therefore be made as needed based on the position of the fibroids and the need to avoid inadvertent extension to the ascending uterine vessels or cornua.17

Fibroid anatomy and vascularity. Fibroids are entirely encased within the dense blood supply of a pseudocapsule (FIGURE 4),18 and no distinct “vascular pedicle” exists at the base of the fibroid.19 It is therefore important to extend the uterine incisions down through the entire pseudocapsule until the fibroid is clearly visible. This will identify a less vascular surgical plane, which is deeper than commonly recognized. Once the fibroid is reached, the pseudocapsule can be “wiped away” using a dry laparotomy sponge (see VIDEO 3). Staying under the pseudocapsule reduces bleeding and may preserve the tissue growth factors and neurotransmitters that are thought to promote wound healing.20

Adhesion prevention. Limiting the number of uterine incisions has been suggested as a way to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic adhesions. To extract fibroids that are distant from an incision, however, tunnels must be created within the myometrium, and this makes hemostasis within these defects difficult. In that blood increases the risk of adhesion formation, tunneling may be counterproductive. If tunneling incisions are avoided and hemostasis is secured immediately, the risk of adhesion formation should be lessened.

Therefore, make incisions directly over the fibroids. Remove only easily accessed fibroids and promptly close the defects to secure hemostasis. Multiple uterine incisions may be needed; adhesion barriers may help limit adhesion formation.21

On final removal of the tourniquet, carefully inspect for bleeding and perform any necessary re-suturing. We place a pain pump (ON-Q* Pain Relief System, Halyard Health, Inc) for pain management and close the abdominal incision in the standard manner.

Postoperative care: Manage pain, restore function

The pain pump infuser, attached to one soaker catheter above and one below the fascia, provides continuous infusion of bupivacaine to the incision at 4 mL per hour for 4 days. The pain pump greatly reduces the need for postoperative opioids.22 Use of a patient-controlled analgesia pump, with its associated adverse effects (sedation, need for oxygen saturation monitoring, slowing of bowel function) can thus be avoided. The patient’s residual pain is controlled with oral oxycodone or hydrocodone and scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In my practice, we use an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol designed to reduce postoperative surgical stress and expedite a return to baseline physiologic body functions.23 Excellent well-researched, evidence-based studies support the effectiveness of ERAS in gynecologic and general surgery procedures.24

Pre-emptive, preoperative analgesia (gabapentin and celecoxib) and end-of-case IV acetaminophen are given to reduce the inflammatory response and the need for postoperative opioids. Once it is confirmed that the patient is hemodynamically stable, add ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours on postoperative day 1. Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis includes ondansetron and dexamethasone at the end of surgery, avoidance of bowel edema with restriction of intraoperative and postoperative fluids (euvolemia), early oral feeding, and gum chewing. On the evening of surgery, the urinary catheter is removed to reduce the risk of bladder infection and facilitate ambulation. Encourage sitting at the bedside and early ambulation starting the evening of surgery to reduce risk of thromboembolism and to avoid skeletal muscle weakness and postoperative fatigue.

Most women are able to be discharged on postoperative day 2. They return to the office on postoperative day 5 for removal of the pain pump.

CASE Continued: Fibroids removed via abdominal myomectomy

We performed an abdominal myomectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. Nine fibroids—3 of which were not seen on MRI—ranging in size from 1 to 7 cm were removed. Intravaginal misoprostol, IV tranexamic acid, subserosal vasopressin, and a uterine vessel tourniquet limited the intraoperative blood loss to 225 mL. After surgery, a pain pump and ERAS protocol allowed the patient to be discharged on postoperative day 2, and she returned to the office on day 5 for removal of the pain pump. Oral pain medication was continued on an as-needed basis.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Stanley West, MD, for generously teaching him the surgical techniques for performing abdominal myomectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

- Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Stocks C, Steiner CA, Myers ER. Statistical brief 200. Procedures to treat benign uterine fibroids in hospital inpatient and hospital-based ambulatory surgery settings, 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb200-Procedures-Treat-Uterine-Fibroids.jsp. Published January 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- Stentz NC, Cooney L, Sammel MD, Shah DK. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) safety communication on morcellation on surgical practice and perioperative morbidity following myomectomy [abstract p300]. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3 suppl):e219.

- Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(4):539–543.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek JS, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Bogani G, Cliby WA, Aletti GD. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167–172.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- West S, Ruiz R, Parker WH. Abdominal myomectomy in women with very large uterine size. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):36–39.

- Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(2):350–357.

- Kim YH, Chung HH, Kang SB, Kim SC, Kim YT. Safety and usefulness of intravenous iron sucrose in the management of preoperative anemia in patients with menorrhagia: a phase IV, open-label, prospective, randomized study. Acta Haematol. 2009;121(1):37–41.

- Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS. Interventions to reduce haemorrhage during myomectomy for fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 15;(8):CD005355.

- Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):484–486.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, Admon D, Mashiach S, Carp H. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2599–2602.

- Yasa C, Dural O, Bastu E, Zorlu M, Demir O, Ugurlucan FG. Impact of laparoscopic ovarian detorsion on ovarian reserve. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(2):298–302.

- Yamada T, Ikeda A, Okamoto Y, Okamoto Y, Kanda T, Ueki M. Intraoperative blood salvage in abdominal simple total hysterectomy for uterine myoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):233–236.

- Discepola F, Valenti DA, Reinhold C, Tulandi T. Analysis of arterial blood vessels surrounding the myoma: relevance to myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1301–1303.

- Malavasi A, Cavalotti C, Nicolardi G, et al. The opioid neuropeptides in uterine fibroid pseudocapsules: a putative association with cervical integrity in human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(11):982–988.

- Walocha JA, Litwin JA, Miodonski AJ. Vascular system of intramural leiomyomata revealed by corrosion casting and scanning electron microscopy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):1088–1093.

- Tinelli A, Mynbaev OA, Sparic R, et al. Angiogenesis and vascularization of uterine leiomyoma: clinical value of pseudocapsule containing peptides and neurotransmitters [published online ahead of print March 22, 2016]. Curr Protein Pept Sci. doi:10.2174/1389203717666160322150338.

- Diamond MP. Reduction of adhesions after uterine myomectomy by Seprafilm membrane (HAL-F): a blinded, prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical study. Seprafilm Adhesion Study Group. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(6):904–910.

- Liu SS, Richman JM, Thirlby RC, Wu CL. Efficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):914–932.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):319–328.

- Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

- Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Stocks C, Steiner CA, Myers ER. Statistical brief 200. Procedures to treat benign uterine fibroids in hospital inpatient and hospital-based ambulatory surgery settings, 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb200-Procedures-Treat-Uterine-Fibroids.jsp. Published January 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- Stentz NC, Cooney L, Sammel MD, Shah DK. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) safety communication on morcellation on surgical practice and perioperative morbidity following myomectomy [abstract p300]. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3 suppl):e219.

- Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(4):539–543.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek JS, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Bogani G, Cliby WA, Aletti GD. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167–172.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- West S, Ruiz R, Parker WH. Abdominal myomectomy in women with very large uterine size. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):36–39.

- Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(2):350–357.

- Kim YH, Chung HH, Kang SB, Kim SC, Kim YT. Safety and usefulness of intravenous iron sucrose in the management of preoperative anemia in patients with menorrhagia: a phase IV, open-label, prospective, randomized study. Acta Haematol. 2009;121(1):37–41.

- Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS. Interventions to reduce haemorrhage during myomectomy for fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 15;(8):CD005355.

- Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):484–486.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, Admon D, Mashiach S, Carp H. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2599–2602.

- Yasa C, Dural O, Bastu E, Zorlu M, Demir O, Ugurlucan FG. Impact of laparoscopic ovarian detorsion on ovarian reserve. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(2):298–302.

- Yamada T, Ikeda A, Okamoto Y, Okamoto Y, Kanda T, Ueki M. Intraoperative blood salvage in abdominal simple total hysterectomy for uterine myoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):233–236.

- Discepola F, Valenti DA, Reinhold C, Tulandi T. Analysis of arterial blood vessels surrounding the myoma: relevance to myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1301–1303.

- Malavasi A, Cavalotti C, Nicolardi G, et al. The opioid neuropeptides in uterine fibroid pseudocapsules: a putative association with cervical integrity in human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(11):982–988.

- Walocha JA, Litwin JA, Miodonski AJ. Vascular system of intramural leiomyomata revealed by corrosion casting and scanning electron microscopy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):1088–1093.

- Tinelli A, Mynbaev OA, Sparic R, et al. Angiogenesis and vascularization of uterine leiomyoma: clinical value of pseudocapsule containing peptides and neurotransmitters [published online ahead of print March 22, 2016]. Curr Protein Pept Sci. doi:10.2174/1389203717666160322150338.

- Diamond MP. Reduction of adhesions after uterine myomectomy by Seprafilm membrane (HAL-F): a blinded, prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical study. Seprafilm Adhesion Study Group. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(6):904–910.

- Liu SS, Richman JM, Thirlby RC, Wu CL. Efficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):914–932.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):319–328.

7 Myomectomy myths debunked

Fibroids are extremely common and can be detected in 60% of African American women and 40% of white women by age 35. By age 50, more than 80% of African American women and almost 70% of white women have fibroids. Although most women with fibroids are relatively asymptomatic, women who have bothersome symptoms, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, urinary frequency, pelvic or abdominal pressure, or pain, account for nearly 30% of all gynecologic admissions in the United States. The cost of fibroid-related care, including surgery, hospital admissions, outpatient visits, and medications, is estimated at $4 to $9 billion per year.1 In addition, each woman seeking treatment for fibroid-related symptoms incurs an expense of $4,500 to $30,000 for lost work or disability every year.1

Many treatment options, including medical therapy and noninvasive procedures, are now available for women with symptomatic fibroids. For women who require surgical treatment, however, hysterectomy is often recommended. Fibroid-related hysterectomy currently accounts for 45% of all hysterectomies, or approximately 195,700 per year. Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical management guidelines state that myomectomy is a safe and effective alternative to hysterectomy for treatment of women with symptomatic fibroids, only 30,000 myomectomies (abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted approaches) are performed each year.2 Why is this? One reason may be that, although many women wish to have uterus-preserving treatment, they often feel that doctors are too quick to recommend hysterectomy as the first—and sometimes only—treatment option for fibroids.3

CASE: Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents for a third opinion regarding her heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy. Both her regular gynecologist and the second gynecologist she consulted recommended hysterectomy as the first, and only, treatment option. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. The patient’s other gynecologists advised her that a myomectomy would be a “bloody operation,” would leave her uterus looking like Swiss cheese, and is not appropriate for women who have completed childbearing.

The patient asks if myomectomy could be considered in her situation. How would you advise her regarding myomectomy as an alternative to hysterectomy?

Organ conservation is important

In 1931, prominent British gynecologic surgeon Victor Bonney said, “Since cure without deformity or loss of function must ever be surgery’s highest ideal, the general proposition that myomectomy is a greater surgical achievement is incontestable.”4 As current hysterectomy and myomectomy rates indicate, however, we are not attempting organ conservation very often.

Other specialties almost never remove an entire organ for benign growths. Using breast cancer surgery as an admirable paradigm, consider that in the early 20th century the standard treatment for breast cancer was a Halsted radical mastectomy with axial lymphadenectomy. By the 1930s, this disfiguring operation was replaced by simple mastectomy and radiation, and by the 1970s, by lumpectomy and lymphadenectomy. Currently, lumpectomy and sentinel node sampling is the standard of care for early stage breast cancer. This is an excellent example of “minimally invasive surgery,” a term fostered by gynecologists. And, these organ-preservingsurgeries are performed for women with cancer, not a benign condition like fibroids.

Although our approach to hysterectomy has evolved with the increasing use of laparoscopic or robotic assistance, removal of the entire uterus nevertheless remains the surgical goal. I think this narrow view of surgical options is a disservice to our patients.

Many of us were taught that myomectomy was associated with more complications and more blood loss than hysterectomy. We were taught that the uterus had no function other than childbearing and that removing the uterus had no adverse health effects. The dogma suggested that myomectomy preserved a uterus that looked like Swiss cheese and would not heal properly and that the risk of fibroid recurrence was high. These beliefs, however, are myths, which are discussed and debunked below. In second and third installments for this series on myomectomy, I present steps for successful abdominal and laparoscopic technique.

Read myths on hysterectomy, myomectomy, and fibroids

MYTH #1: Hysterectomy is safer than myomectomy

Myomectomy is performed within the confines of the uterus and myometrium, with only infrequent occasion to operate near the ureters, uterine vessels, bowel, or bladder. Therefore, it should not be surprising that studies show that fewer complications occur with myomectomy than with hysterectomy.

A retrospective review of 197 women who had myomectomy and 197 women who underwent hysterectomy with similar uterine size (14 vs 15 weeks) reported that 13% (n = 26) of women in the hysterectomy group experienced complications, including 1 bladder injury, 1 ureteral injury, and 3 bowel injuries; 8 women had an ileus and 6 women had a pelvic abscess.5 Only 5% (n = 11) of the myomectomy patients had complications, including 1 bladder injury; 2 women had reoperation for small bowel obstruction, and 6 women had an ileus. The risks of febrile morbidity, unintended surgical procedure, life-threatening events, and rehospitalization were similar for both groups.

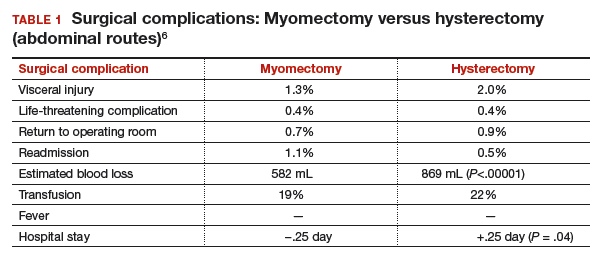

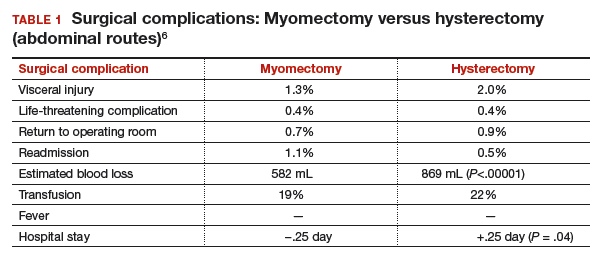

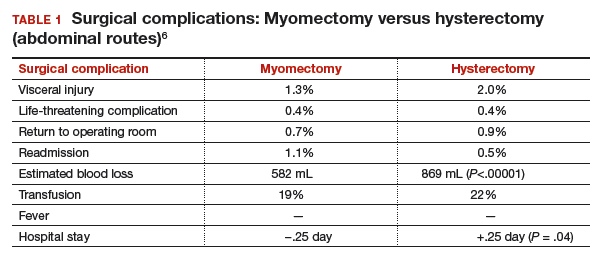

Authors of a recent systematic review of 6 studies, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 18 weeks, found higher rates of visceral injury and longer hospital stays for women who had a hysterectomy compared with those who had a myomectomy (TABLE 1).6

MYTH #2: Myomectomy is associated with more surgical blood loss than hysterectomy

In the previously cited study of 197 women treated with myomectomy and 197 women treated with hysterectomy, the estimated blood loss was greater in the hysterectomy group (484 mL) than in the myomectomy group (227 mL). When uterine size was corrected for, blood loss was no greater for myomectomy than for hysterectomy.5 The risk of hemorrhage (>500 mL blood loss) was greater in the hysterectomy group (14.2% vs 9.6%). Authors of the recent meta-analysis also found that the rate of transfusion was higher in the hysterectomy cohort. Tourniquets, misoprostol, vasopressin, and tranexamic acid all have been shown to significantly decrease surgical blood loss. (These treatments will be discussed in the next installment of this article series.)

MYTH #3: A uterus will look like Swiss cheese after a myomectomy

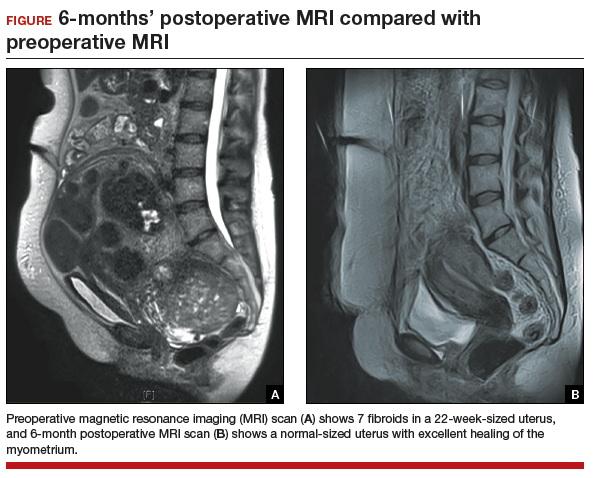

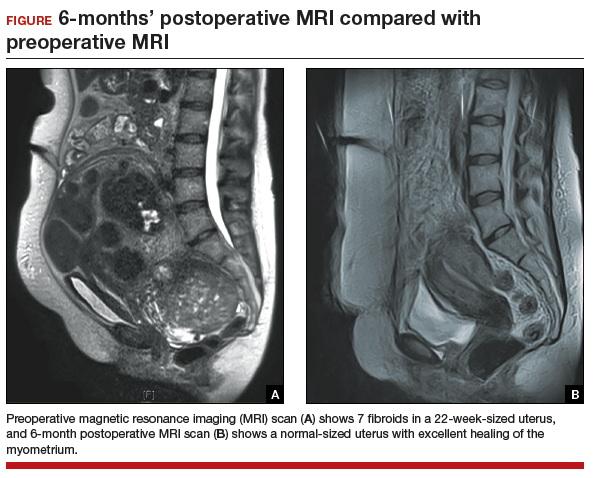

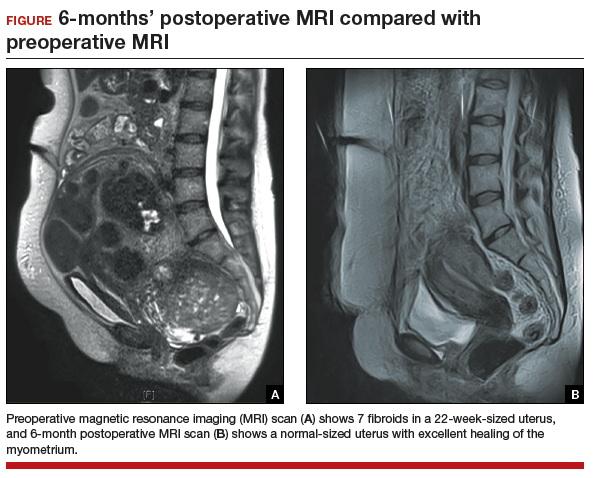

The uterus heals remarkably well after myomectomy. Three months following laparoscopic myomectomy, 3-dimensional Doppler ultrasonography demonstrated complete myometrial healing and normal blood flow to the uterus.7 In a study of women undergoing abdominal myomectomy, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium showed complete healing of the myometrium and normal myometrial perfusion by 3 months.8 This study also found that, after removal of 65 g to 380 g of fibroids, the uterine volume 3 months after surgery was 65 mL, essentially equivalent to the normal volume of a uterus without fibroids (57 mL).8 See FIGURE for MRI scans of the uterus before and after myomectomy.

MYTH #4: Fibroids will just grow back after myomectomy

Once a fibroid is completely removed surgically, it does not grow back. The risk of new fibroid growth depends on the number of fibroids originally removed and the amount of time until menopause, when fibroids reduce in size and symptoms usually resolve. Given that the prevalence of fibroids is nearly 80% by age 50, studies measuring the detection of new fibroid growth of 1 cm on ultrasound imaging overstate the problem.9 What is likely a more important consideration for women is whether, following myomectomy, they will need another procedure for new fibroid-related symptoms.

Results of a meta-analysis of 872 women in 7 studies with 10- to 25-year follow-up indicated that 89% of women did not require another surgery.10 In another study, authors found that, over an average follow-up of 7.6 years, a second surgery occurred in 11% of the women who had 1 fibroid initially removed and for 26% of women who had multiple fibroids initially removed.11 In another study of 92 women who had either abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy after age 45and who were followed for an average of 30 months, only 1 woman (1%) required a hysterectomy for fibroid-related symptoms.12 That patient had growth of a fibroid that was present but was not removed at her initial laparoscopic myomectomy.

Read myths 5–7 on ovarian conservation, fibroid growth, and symptom improvement

MYTH #5: Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation does not change hormone levels

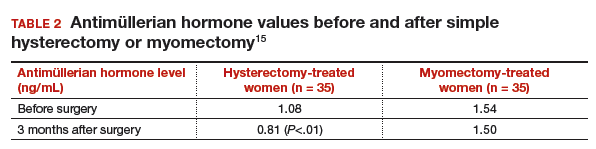

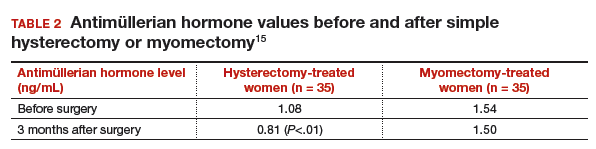

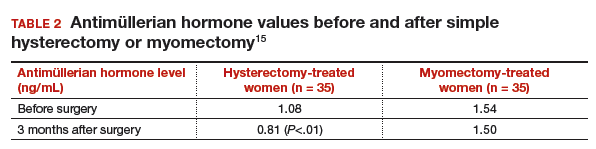

Following hysterectomy with ovarian conservation, some women begin menopause earlier than age-matched women who have not undergone any surgery.13 Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation prior to age 50 has been associated with a significant increase in the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.14 In a prospective longitudinal study, antimüllerian hormone (AMH) levels were persistently decreased following hysterectomy despite ovarian conservation.15 However, 3 months after myomectomy, no such changes in AMH levels were seen (TABLE 2).15

Early natural menopause has been associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease and death, and bilateral oophorectomy has been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, lung cancer, colon cancer, anxiety, and depression. Although taking estrogen might obviate these adverse health effects, the majority of women who receive a prescription for estrogen following surgery are no longer taking it 5 years later.

MYTH #6: Fibroid growth in a premenopausal patient means cancer may be present

While most fibroids grow slowly, rapid growth of benign fibroids is very common. Using computerized analysis of a group of 72 women having serial MRI scans, investigators found that 34% of benign fibroids increased more than 20% in volume over 6 months.16 In premenopausal women, “rapid uterine growth” almost never indicates presence of uterine sarcoma. One study reported only 1 sarcoma among 371 women operated on for rapid growth of presumed fibroids.17 Using current criteria from the World Health Organization to determine the pathologic diagnosis, however, that 1 woman was determined to have had an atypical leiomyoma. Therefore, the prevalence of leiomyosarcoma in that study approached zero. In addition, in the 198 women who had a 6-week increase in uterine size over 1 year (one published definition of rapid growth), no sarcomas were found.17

Because of recent concern about leiomyosarcoma and morcellation of fibroids, some gynecologists have reverted to advising women that growing fibroids might be cancer and that hysterectomy is recommended. However, there is no evidence that fibroid growth is a sign of leiomyosarcoma in premenopausal women. Leiomyosarcoma should strongly be considered in a postmenopausal woman on no hormone therapy who has growth of a presumed fibroid.

MYTH #7: Myomectomy will not improve symptoms

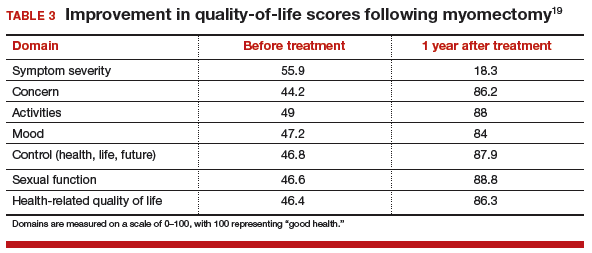

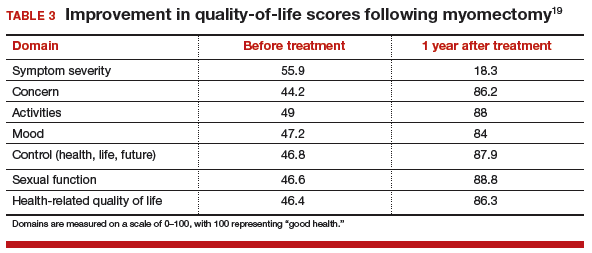

Fibroid-related symptoms can be significant; women who undergo hysterectomy because of fibroid-related symptoms have significantly worse scores on the 36-Item Short-Form Survey (SF-36) quality-of-life questionnaire than women diagnosed with hypertension, heart disease, chronic lung disease, or arthritis.18

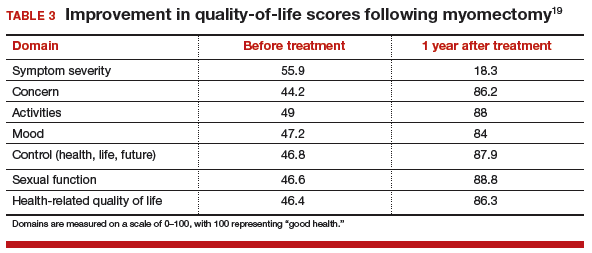

For women with fibroid-related symptoms, myomectomy has been shown to improve quality of life. A study of 72 women showed that SF-36 scores improved significantly following myomectomy (TABLE 3, page 48).19 In another study that used the European Quality of Life Five-Dimension Scale and Visual Analog Scale, 95 women had significant improvement in quality of life (P<.001) following laparoscopic myomectomy.20

For some women, hysterectomy may have an impact on emotional quality of life. Some women report decreased sexual desire after hysterectomy. They worry that partners will see them as “not whole” and less desirable. Some women expect that hysterectomy will lead to depression, crying, lack of sexual desire, and vaginal dryness.21 No such changes have been reported for women having myomectomy.

CASE Continued: Third consult leads patient to schedule surgical procedure

After reviewing the patient’s symptoms, examination, and ultrasound results, we advise the patient that abdominal myomectomy is indeed appropriate and feasible in her case. She schedules surgery for the following month.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):211.e1–e9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387–400.

- Borah BJ, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Stewart EA. The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):319.e1–e20.

- Bonney V. The technique and results of myomectomy. Lancet. 1931;217(5604):171-177.

- Sawin SW, Pilevsky ND, Berlin JA, Barnhart KT. Comparability of perioperative morbidity between abdominal myomectomy and hysterectomy for women with uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1448–1455.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- Chang WC, Chang DY, Huang SC, et al. Use of three-dimensional ultrasonography in the evaluation of uterine perfusion and healing after laparoscopic myomectomy. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1110–1115.

- Tsuji S, Takahashi K, Imaoka I, Sugimura K, Miyazaki K, Noda Y. MRI evaluation of the uterine structure after myomectomy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61(2):106–110.

- Sudik R, Husch K, Steller J, Daume E. Fertility and pregnancy outcome after myomectomy in sterility patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65(2):209–214.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C, Babaki-Fard K, Dubuisson JB. Recurrence of leiomyomata after myomectomy. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6(6):595–602.

- Malone, LJ. Myomectomy: recurrence after removal of solitary and multiple myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1969;34(2):200–203.

- Kim DH, Kim ML, Song T, Kim MK, Yoon BS, Seong SJ. Is myomectomy in women aged 45 years and older an effective option? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:57–60.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, Stewart AW. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112(7):956–962.

- Ingelsson E, Lundholm C, Johansson AL, Altman D. Hysterectomy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(6):745–750.

- Wang HY, Quan S, Zhang RL, et al. Comparison of serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels following hysterectomy and myomectomy for benign gynaecological conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171(2):368–371.

- Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(50):19887–19892.

- Parker W, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(3):414–418.

- Rowe MK, Kanouse DE, Mittman BS, Bernstein SJ. Quality of life among women undergoing hysterectomies. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(6):915–921.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Radosa JC, Radosa CG, Mavrova R, et al. Postoperative quality of life and sexual function in premenopausal women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy for symptomatic fibroids: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;29;11(11):e0166659.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, Shelton AJ, Lees E, Goode J. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(suppl 2):39S–50S.

Fibroids are extremely common and can be detected in 60% of African American women and 40% of white women by age 35. By age 50, more than 80% of African American women and almost 70% of white women have fibroids. Although most women with fibroids are relatively asymptomatic, women who have bothersome symptoms, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, urinary frequency, pelvic or abdominal pressure, or pain, account for nearly 30% of all gynecologic admissions in the United States. The cost of fibroid-related care, including surgery, hospital admissions, outpatient visits, and medications, is estimated at $4 to $9 billion per year.1 In addition, each woman seeking treatment for fibroid-related symptoms incurs an expense of $4,500 to $30,000 for lost work or disability every year.1

Many treatment options, including medical therapy and noninvasive procedures, are now available for women with symptomatic fibroids. For women who require surgical treatment, however, hysterectomy is often recommended. Fibroid-related hysterectomy currently accounts for 45% of all hysterectomies, or approximately 195,700 per year. Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical management guidelines state that myomectomy is a safe and effective alternative to hysterectomy for treatment of women with symptomatic fibroids, only 30,000 myomectomies (abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted approaches) are performed each year.2 Why is this? One reason may be that, although many women wish to have uterus-preserving treatment, they often feel that doctors are too quick to recommend hysterectomy as the first—and sometimes only—treatment option for fibroids.3

CASE: Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy