User login

Just 20 minutes of vigorous activity daily benefits teens

Vigorous physical activity for 20 minutes a day was enough to maximize cardiorespiratory benefits in adolescents, based on data from more than 300 individuals.

Current recommendations for physical activity in children and adolescents from the World Health Organization call for moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) for an average of 60 minutes a day for physical and mental health; however, guidance on how much physical activity teens need to maximize cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) has not been determined, Samuel Joseph Burden, BMedSci, of John Radcliffe Hospital Oxford (England), and colleagues wrote.

“Although data in young people are limited, adult studies have shown that regular, brief vigorous physical activity is highly effective at improving health markers, including CRF, which is also an important marker of health in youth,” the researchers wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers examined the associations between physical activity intensity and maximal CRF. The study population included 339 adolescents aged 13-14 years who were evaluated during the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 school years. Participants wore wrist accelerometers to measure the intensity of physical activity and participated in 20-meter shuttle runs to demonstrate CRF. The researchers used partial multivariable linear regression to assess variables at different intensities including moderate physical activity (MPA), light physical activity (LPA), and sedentary time, as well as vigorous physical activity (VPA).

The wrist monitors measured the intensities of physical activity based on the bandpass-filtered followed by Euclidean norm metric (BFEN), a validated metric. “Previously validated thresholds for BFEN were used to determine the average duration of daily physical activity at each intensity: 0.1 g for LPA, 0.314 g for MPA, and 0.998 g for VPA,” the researchers wrote. Physical activity below the threshold for LPA was categorized as sedentary time.

Participants wore the accelerometers for 1 week; value recording included at least 3 weekdays and 1 weekend day, and each valid day required more than 6 hours of awake time.

Overall, VPA for up to 20 minutes was significantly associated with improved CRF. However, the benefits on CRF plateaued after that time, and longer duration of VPA was not associated with significantly greater improvements in CRF. Neither MPA nor LPA were associated with any improvements in CRF.

Participants who engaged in an average of 14 minutes (range, 12-17 minutes) of VPA per day met the median CRF.

The researchers also conducted independent t tests to assess differences in VPA at different CRF thresholds.

Those in the highest quartile of VPA had CRF z scores 1.03 higher, compared with those in the lower quartiles.

Given that current PA guidelines involve a combination of moderate and vigorous PA that could be met by MPA with no VPA, the current findings have public health implications for improving CRF in adolescents, the researchers wrote.

Even with MPA as an option, most adolescents fail to meet the recommendations of at least 60 minutes of MVPA, they said. “One possible reason is that this duration is quite long, requiring a daily time commitment that some may find difficult to maintain. A shorter target of 20 minutes might be easier to schedule daily and a focus on VPA would simplify messages about the intensity of activity that is likely to improve CRF.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from only two schools in the United Kingdom, which may limit generalizability, and future research would ideally include a more direct assessment of VO2 max, the researchers wrote. However, the results were strengthened by the large and diverse study population, including teens with a wide range of body mass index as well as CRF.

Future research is needed to test whether interventions based on a target of 20 minutes of VPA creates significant improvements in adolescent cardiometabolic health, the researchers concluded.

Any activity has value for sedentary teens

The current study suggests that counseling teens about physical activity may be less challenging for clinicians if optimal cardiorespiratory benefits can be reached with shorter bouts of activity, Michele LaBotz, MD, of Intermed Sports Medicine, South Portland, Maine, and Sarah Hoffman, DO, of Tufts University, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The results have two key implications for pediatricians, the authors said. First, “optimal CRF can be achieved with much shorter periods of activity than previously recommended.” Second, “current ‘moderate to vigorous’ PA recommendations may not be sufficient to improve CRF in adolescents, if achieved through moderate activity only.”

However, the editorialists emphasized that, although shorter periods of higher-intensity exercise reduce the time burden for teens and families, specific education is needed to explain the extra effort involved in exercising vigorously enough for cardiorespiratory benefits.

Patients can be counseled that activity is vigorous when they start to sweat, their face gets red, and they feel short of breath and unable to talk during activity,” they explained. These sensations may be new and uncomfortable for children and teens who have been quite sedentary or used to low-intensity activity. Dr. LaBotz and Dr. Hoffman advised pediatricians to counsel patients to build intensity gradually, with “exercise snacks,” that involve several minutes of activity that become more challenging over time.

“Exercise snacks can include anything that elevates the heart rate for a minute or more, such as running up and down the stairs a few times; chasing the dog around the backyard; or just putting on some music and dancing hard,” the editorialists wrote.

“Some exercise is better than none, and extrapolating from adult data, the biggest benefit likely occurs when we can help our most sedentary and least fit patients become a bit more active, even if it falls short of currently recommended levels,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to various researchers from the British Heart Foundation, the Elizabeth Casson Trust, the U.K. National Institute of Health Research, the Professor Nigel Groome Studentship scheme (Oxford Brookes University), and the U.K. Department of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Vigorous physical activity for 20 minutes a day was enough to maximize cardiorespiratory benefits in adolescents, based on data from more than 300 individuals.

Current recommendations for physical activity in children and adolescents from the World Health Organization call for moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) for an average of 60 minutes a day for physical and mental health; however, guidance on how much physical activity teens need to maximize cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) has not been determined, Samuel Joseph Burden, BMedSci, of John Radcliffe Hospital Oxford (England), and colleagues wrote.

“Although data in young people are limited, adult studies have shown that regular, brief vigorous physical activity is highly effective at improving health markers, including CRF, which is also an important marker of health in youth,” the researchers wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers examined the associations between physical activity intensity and maximal CRF. The study population included 339 adolescents aged 13-14 years who were evaluated during the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 school years. Participants wore wrist accelerometers to measure the intensity of physical activity and participated in 20-meter shuttle runs to demonstrate CRF. The researchers used partial multivariable linear regression to assess variables at different intensities including moderate physical activity (MPA), light physical activity (LPA), and sedentary time, as well as vigorous physical activity (VPA).

The wrist monitors measured the intensities of physical activity based on the bandpass-filtered followed by Euclidean norm metric (BFEN), a validated metric. “Previously validated thresholds for BFEN were used to determine the average duration of daily physical activity at each intensity: 0.1 g for LPA, 0.314 g for MPA, and 0.998 g for VPA,” the researchers wrote. Physical activity below the threshold for LPA was categorized as sedentary time.

Participants wore the accelerometers for 1 week; value recording included at least 3 weekdays and 1 weekend day, and each valid day required more than 6 hours of awake time.

Overall, VPA for up to 20 minutes was significantly associated with improved CRF. However, the benefits on CRF plateaued after that time, and longer duration of VPA was not associated with significantly greater improvements in CRF. Neither MPA nor LPA were associated with any improvements in CRF.

Participants who engaged in an average of 14 minutes (range, 12-17 minutes) of VPA per day met the median CRF.

The researchers also conducted independent t tests to assess differences in VPA at different CRF thresholds.

Those in the highest quartile of VPA had CRF z scores 1.03 higher, compared with those in the lower quartiles.

Given that current PA guidelines involve a combination of moderate and vigorous PA that could be met by MPA with no VPA, the current findings have public health implications for improving CRF in adolescents, the researchers wrote.

Even with MPA as an option, most adolescents fail to meet the recommendations of at least 60 minutes of MVPA, they said. “One possible reason is that this duration is quite long, requiring a daily time commitment that some may find difficult to maintain. A shorter target of 20 minutes might be easier to schedule daily and a focus on VPA would simplify messages about the intensity of activity that is likely to improve CRF.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from only two schools in the United Kingdom, which may limit generalizability, and future research would ideally include a more direct assessment of VO2 max, the researchers wrote. However, the results were strengthened by the large and diverse study population, including teens with a wide range of body mass index as well as CRF.

Future research is needed to test whether interventions based on a target of 20 minutes of VPA creates significant improvements in adolescent cardiometabolic health, the researchers concluded.

Any activity has value for sedentary teens

The current study suggests that counseling teens about physical activity may be less challenging for clinicians if optimal cardiorespiratory benefits can be reached with shorter bouts of activity, Michele LaBotz, MD, of Intermed Sports Medicine, South Portland, Maine, and Sarah Hoffman, DO, of Tufts University, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The results have two key implications for pediatricians, the authors said. First, “optimal CRF can be achieved with much shorter periods of activity than previously recommended.” Second, “current ‘moderate to vigorous’ PA recommendations may not be sufficient to improve CRF in adolescents, if achieved through moderate activity only.”

However, the editorialists emphasized that, although shorter periods of higher-intensity exercise reduce the time burden for teens and families, specific education is needed to explain the extra effort involved in exercising vigorously enough for cardiorespiratory benefits.

Patients can be counseled that activity is vigorous when they start to sweat, their face gets red, and they feel short of breath and unable to talk during activity,” they explained. These sensations may be new and uncomfortable for children and teens who have been quite sedentary or used to low-intensity activity. Dr. LaBotz and Dr. Hoffman advised pediatricians to counsel patients to build intensity gradually, with “exercise snacks,” that involve several minutes of activity that become more challenging over time.

“Exercise snacks can include anything that elevates the heart rate for a minute or more, such as running up and down the stairs a few times; chasing the dog around the backyard; or just putting on some music and dancing hard,” the editorialists wrote.

“Some exercise is better than none, and extrapolating from adult data, the biggest benefit likely occurs when we can help our most sedentary and least fit patients become a bit more active, even if it falls short of currently recommended levels,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to various researchers from the British Heart Foundation, the Elizabeth Casson Trust, the U.K. National Institute of Health Research, the Professor Nigel Groome Studentship scheme (Oxford Brookes University), and the U.K. Department of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Vigorous physical activity for 20 minutes a day was enough to maximize cardiorespiratory benefits in adolescents, based on data from more than 300 individuals.

Current recommendations for physical activity in children and adolescents from the World Health Organization call for moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) for an average of 60 minutes a day for physical and mental health; however, guidance on how much physical activity teens need to maximize cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) has not been determined, Samuel Joseph Burden, BMedSci, of John Radcliffe Hospital Oxford (England), and colleagues wrote.

“Although data in young people are limited, adult studies have shown that regular, brief vigorous physical activity is highly effective at improving health markers, including CRF, which is also an important marker of health in youth,” the researchers wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers examined the associations between physical activity intensity and maximal CRF. The study population included 339 adolescents aged 13-14 years who were evaluated during the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 school years. Participants wore wrist accelerometers to measure the intensity of physical activity and participated in 20-meter shuttle runs to demonstrate CRF. The researchers used partial multivariable linear regression to assess variables at different intensities including moderate physical activity (MPA), light physical activity (LPA), and sedentary time, as well as vigorous physical activity (VPA).

The wrist monitors measured the intensities of physical activity based on the bandpass-filtered followed by Euclidean norm metric (BFEN), a validated metric. “Previously validated thresholds for BFEN were used to determine the average duration of daily physical activity at each intensity: 0.1 g for LPA, 0.314 g for MPA, and 0.998 g for VPA,” the researchers wrote. Physical activity below the threshold for LPA was categorized as sedentary time.

Participants wore the accelerometers for 1 week; value recording included at least 3 weekdays and 1 weekend day, and each valid day required more than 6 hours of awake time.

Overall, VPA for up to 20 minutes was significantly associated with improved CRF. However, the benefits on CRF plateaued after that time, and longer duration of VPA was not associated with significantly greater improvements in CRF. Neither MPA nor LPA were associated with any improvements in CRF.

Participants who engaged in an average of 14 minutes (range, 12-17 minutes) of VPA per day met the median CRF.

The researchers also conducted independent t tests to assess differences in VPA at different CRF thresholds.

Those in the highest quartile of VPA had CRF z scores 1.03 higher, compared with those in the lower quartiles.

Given that current PA guidelines involve a combination of moderate and vigorous PA that could be met by MPA with no VPA, the current findings have public health implications for improving CRF in adolescents, the researchers wrote.

Even with MPA as an option, most adolescents fail to meet the recommendations of at least 60 minutes of MVPA, they said. “One possible reason is that this duration is quite long, requiring a daily time commitment that some may find difficult to maintain. A shorter target of 20 minutes might be easier to schedule daily and a focus on VPA would simplify messages about the intensity of activity that is likely to improve CRF.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from only two schools in the United Kingdom, which may limit generalizability, and future research would ideally include a more direct assessment of VO2 max, the researchers wrote. However, the results were strengthened by the large and diverse study population, including teens with a wide range of body mass index as well as CRF.

Future research is needed to test whether interventions based on a target of 20 minutes of VPA creates significant improvements in adolescent cardiometabolic health, the researchers concluded.

Any activity has value for sedentary teens

The current study suggests that counseling teens about physical activity may be less challenging for clinicians if optimal cardiorespiratory benefits can be reached with shorter bouts of activity, Michele LaBotz, MD, of Intermed Sports Medicine, South Portland, Maine, and Sarah Hoffman, DO, of Tufts University, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The results have two key implications for pediatricians, the authors said. First, “optimal CRF can be achieved with much shorter periods of activity than previously recommended.” Second, “current ‘moderate to vigorous’ PA recommendations may not be sufficient to improve CRF in adolescents, if achieved through moderate activity only.”

However, the editorialists emphasized that, although shorter periods of higher-intensity exercise reduce the time burden for teens and families, specific education is needed to explain the extra effort involved in exercising vigorously enough for cardiorespiratory benefits.

Patients can be counseled that activity is vigorous when they start to sweat, their face gets red, and they feel short of breath and unable to talk during activity,” they explained. These sensations may be new and uncomfortable for children and teens who have been quite sedentary or used to low-intensity activity. Dr. LaBotz and Dr. Hoffman advised pediatricians to counsel patients to build intensity gradually, with “exercise snacks,” that involve several minutes of activity that become more challenging over time.

“Exercise snacks can include anything that elevates the heart rate for a minute or more, such as running up and down the stairs a few times; chasing the dog around the backyard; or just putting on some music and dancing hard,” the editorialists wrote.

“Some exercise is better than none, and extrapolating from adult data, the biggest benefit likely occurs when we can help our most sedentary and least fit patients become a bit more active, even if it falls short of currently recommended levels,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to various researchers from the British Heart Foundation, the Elizabeth Casson Trust, the U.K. National Institute of Health Research, the Professor Nigel Groome Studentship scheme (Oxford Brookes University), and the U.K. Department of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Asian American teens have highest rate of suicidal ideation

NEW ORLEANS – In an unexpected finding, researchers discovered that According to a weighted analysis, 24% of Asian Americans reported thinking about or planning suicide vs. 22% of Whites and Blacks and 20% of Hispanics (P < .01).

“We were shocked,” said study lead author Esha Hansoti, MD, who conducted the research at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and is now a psychiatry resident at Zucker Hillside Hospital Northwell/Hofstra in Glen Oaks, NY. The findings were released at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Dr. Hansoti and colleagues launched the analysis in light of sparse research into Asian American mental health, she said. Even within this population, she said, mental illness “tends to be overlooked” and discussion of the topic may be considered taboo.

For the new study, researchers analyzed the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, conducted biennially by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which had more than 13,000 participants in grades 9-12.

A weighted bivariate analysis of 618 Asian American adolescents – adjusted for age, sex, and depressive symptoms – found no statistically significant impact on suicidal ideation by gender, age, substance use, sexual/physical dating violence, or fluency in English.

However, several groups had a statistically significant higher risk, including victims of forced sexual intercourse and those who were threatened or bullied at school.

Those who didn’t get mostly A grades were also at high risk: Adolescents with mostly Ds and Fs were more likely to have acknowledged suicidal ideation than those with mostly As (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.2).

Gays and lesbians (AOR = 7.9 vs. heterosexuals), and bisexuals (AOR = 5.2 vs. heterosexuals) also showed sharply higher rates of suicidal ideation.

It’s not clear why Asian American adolescents may be at higher risk of suicidal ideation. The survey was completed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which spawned bigotry against people of Asian descent and an ongoing outbreak of high-profile violence against Asian Americans across the country.

Dr. Hansoti noted that Asian Americans face the pressures to live up to the standards of being a “model minority.” In addition, “very few Asian American adolescents are taken to a therapist, and few mental health providers are Asian Americans.”

She urged fellow psychiatrists “to remember that our perceptions of Asian Americans might hinder some of the diagnoses we could be making. Be thoughtful about how their ethnicity and race affects their presentation and their own perception of their illness.”

She added that Asian Americans may experience mental illness and anxiety “more somatically and physically than emotionally.”

In an interview, Anne Saw, PhD, associate professor of clinical-community psychology at DePaul University, Chicago, said the findings are “helpful for corroborating other studies identifying risk factors of suicidal ideation among Asian American adolescents. Since this research utilizes the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, these findings can be compared with risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents from other racial/ethnic backgrounds to pinpoint general as well as specific risk factors, thus informing how we can tailor interventions for specific groups.”

According to Dr. Saw, while it’s clear that suicide is a leading cause of death among Asian American adolescents, it’s still unknown which specific subgroups other than girls and LGBTIA+ individuals are especially vulnerable and which culturally tailored interventions are most effective for decreasing suicide risk.

“Psychiatrists should understand that risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in Asian American adolescents are multifaceted and require careful attention and intervention across different environments,” she said.

No funding and no disclosures were reported.

NEW ORLEANS – In an unexpected finding, researchers discovered that According to a weighted analysis, 24% of Asian Americans reported thinking about or planning suicide vs. 22% of Whites and Blacks and 20% of Hispanics (P < .01).

“We were shocked,” said study lead author Esha Hansoti, MD, who conducted the research at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and is now a psychiatry resident at Zucker Hillside Hospital Northwell/Hofstra in Glen Oaks, NY. The findings were released at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Dr. Hansoti and colleagues launched the analysis in light of sparse research into Asian American mental health, she said. Even within this population, she said, mental illness “tends to be overlooked” and discussion of the topic may be considered taboo.

For the new study, researchers analyzed the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, conducted biennially by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which had more than 13,000 participants in grades 9-12.

A weighted bivariate analysis of 618 Asian American adolescents – adjusted for age, sex, and depressive symptoms – found no statistically significant impact on suicidal ideation by gender, age, substance use, sexual/physical dating violence, or fluency in English.

However, several groups had a statistically significant higher risk, including victims of forced sexual intercourse and those who were threatened or bullied at school.

Those who didn’t get mostly A grades were also at high risk: Adolescents with mostly Ds and Fs were more likely to have acknowledged suicidal ideation than those with mostly As (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.2).

Gays and lesbians (AOR = 7.9 vs. heterosexuals), and bisexuals (AOR = 5.2 vs. heterosexuals) also showed sharply higher rates of suicidal ideation.

It’s not clear why Asian American adolescents may be at higher risk of suicidal ideation. The survey was completed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which spawned bigotry against people of Asian descent and an ongoing outbreak of high-profile violence against Asian Americans across the country.

Dr. Hansoti noted that Asian Americans face the pressures to live up to the standards of being a “model minority.” In addition, “very few Asian American adolescents are taken to a therapist, and few mental health providers are Asian Americans.”

She urged fellow psychiatrists “to remember that our perceptions of Asian Americans might hinder some of the diagnoses we could be making. Be thoughtful about how their ethnicity and race affects their presentation and their own perception of their illness.”

She added that Asian Americans may experience mental illness and anxiety “more somatically and physically than emotionally.”

In an interview, Anne Saw, PhD, associate professor of clinical-community psychology at DePaul University, Chicago, said the findings are “helpful for corroborating other studies identifying risk factors of suicidal ideation among Asian American adolescents. Since this research utilizes the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, these findings can be compared with risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents from other racial/ethnic backgrounds to pinpoint general as well as specific risk factors, thus informing how we can tailor interventions for specific groups.”

According to Dr. Saw, while it’s clear that suicide is a leading cause of death among Asian American adolescents, it’s still unknown which specific subgroups other than girls and LGBTIA+ individuals are especially vulnerable and which culturally tailored interventions are most effective for decreasing suicide risk.

“Psychiatrists should understand that risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in Asian American adolescents are multifaceted and require careful attention and intervention across different environments,” she said.

No funding and no disclosures were reported.

NEW ORLEANS – In an unexpected finding, researchers discovered that According to a weighted analysis, 24% of Asian Americans reported thinking about or planning suicide vs. 22% of Whites and Blacks and 20% of Hispanics (P < .01).

“We were shocked,” said study lead author Esha Hansoti, MD, who conducted the research at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and is now a psychiatry resident at Zucker Hillside Hospital Northwell/Hofstra in Glen Oaks, NY. The findings were released at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Dr. Hansoti and colleagues launched the analysis in light of sparse research into Asian American mental health, she said. Even within this population, she said, mental illness “tends to be overlooked” and discussion of the topic may be considered taboo.

For the new study, researchers analyzed the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, conducted biennially by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which had more than 13,000 participants in grades 9-12.

A weighted bivariate analysis of 618 Asian American adolescents – adjusted for age, sex, and depressive symptoms – found no statistically significant impact on suicidal ideation by gender, age, substance use, sexual/physical dating violence, or fluency in English.

However, several groups had a statistically significant higher risk, including victims of forced sexual intercourse and those who were threatened or bullied at school.

Those who didn’t get mostly A grades were also at high risk: Adolescents with mostly Ds and Fs were more likely to have acknowledged suicidal ideation than those with mostly As (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.2).

Gays and lesbians (AOR = 7.9 vs. heterosexuals), and bisexuals (AOR = 5.2 vs. heterosexuals) also showed sharply higher rates of suicidal ideation.

It’s not clear why Asian American adolescents may be at higher risk of suicidal ideation. The survey was completed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which spawned bigotry against people of Asian descent and an ongoing outbreak of high-profile violence against Asian Americans across the country.

Dr. Hansoti noted that Asian Americans face the pressures to live up to the standards of being a “model minority.” In addition, “very few Asian American adolescents are taken to a therapist, and few mental health providers are Asian Americans.”

She urged fellow psychiatrists “to remember that our perceptions of Asian Americans might hinder some of the diagnoses we could be making. Be thoughtful about how their ethnicity and race affects their presentation and their own perception of their illness.”

She added that Asian Americans may experience mental illness and anxiety “more somatically and physically than emotionally.”

In an interview, Anne Saw, PhD, associate professor of clinical-community psychology at DePaul University, Chicago, said the findings are “helpful for corroborating other studies identifying risk factors of suicidal ideation among Asian American adolescents. Since this research utilizes the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, these findings can be compared with risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents from other racial/ethnic backgrounds to pinpoint general as well as specific risk factors, thus informing how we can tailor interventions for specific groups.”

According to Dr. Saw, while it’s clear that suicide is a leading cause of death among Asian American adolescents, it’s still unknown which specific subgroups other than girls and LGBTIA+ individuals are especially vulnerable and which culturally tailored interventions are most effective for decreasing suicide risk.

“Psychiatrists should understand that risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in Asian American adolescents are multifaceted and require careful attention and intervention across different environments,” she said.

No funding and no disclosures were reported.

AT APA 2022

Youth with bipolar disorder at high risk of eating disorders

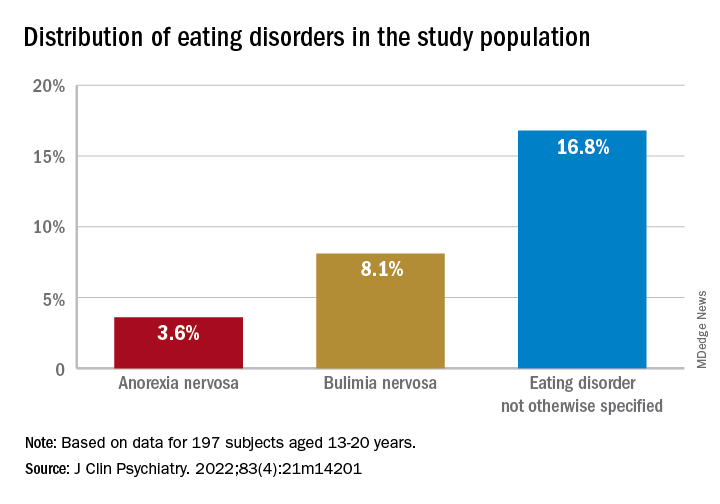

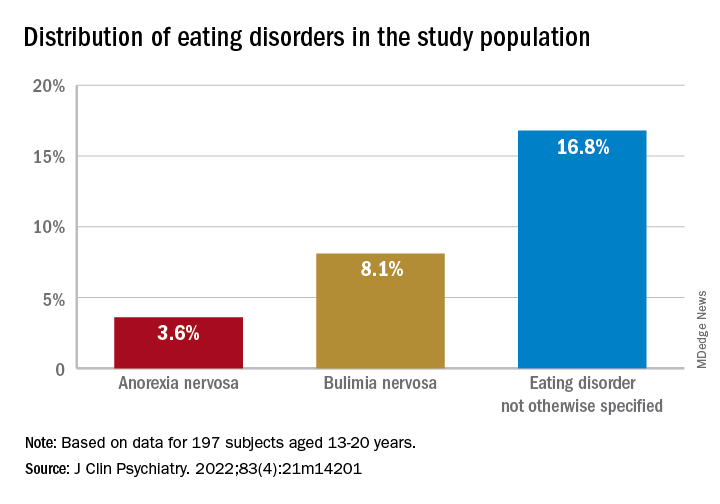

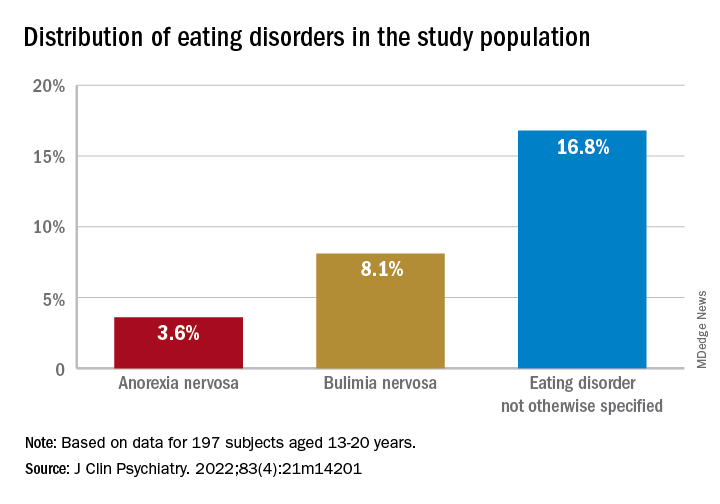

Investigators studied close to 200 youth with BD and found that more than 25% had a lifetime ED, which included anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and an ED not otherwise specified (NOS).

Those with comorbid EDs were more likely to be female and to have BD-II subtype. Their presentations were also more complicated and included a history of suicidality, additional psychiatric conditions, smoking, and a history of sexual abuse, as well as more severe depression and emotional instability.

“We think the take-home message is that, in addition to other more recognized psychiatric comorbidities, youth with BD are also vulnerable to developing EDs. Thus, clinicians should be routinely monitoring for eating, appetite, and body image disturbances when working with this population,” lead author Diana Khoubaeva, research analyst at the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, and senior author Benjamin Goldstein, MD, PhD, director of the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, wrote in an e-mail to this news organization.

“Given the more complicated clinical picture of youth with co-occurring BD and EDs, this combination warrants careful attention,” the investigators note.

The study was published online May 11 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Lack of research

“From the existing literature, we learned that EDs are not uncommon in individuals with BD, and that they are often associated with a more severe clinical profile,” say the researchers. “However, the majority of these studies have been limited to adult samples, and there was a real scarcity of studies that examined this co-occurrence in youth.”

This is “surprising” because EDs often have their onset in adolescence, so the researchers decided to explore the issue in their “fairly large sample of youth with BD.”

To investigate the issue, the researchers studied 197 youth (aged 13-20 years) with a diagnosis of BD (BD-I, BD-II, or BD-NOS) who were recruited between 2009 and 2017 (mean [standard deviation] age, 16.69 [1.50] years; 67.5% female).

ED diagnoses included both current and lifetime AN, BN, and ED-NOS. The researchers used the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) to determine the diagnosis of BD.

They also collected information about comorbid psychiatric disorders, as well as substance use disorders and cigarette smoking. The Life Problems Inventory (LPI) was used to identify dimensional borderline personality traits.

Information about physical and sexual abuse, suicidal ideation, nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), and affect regulation were obtained from other measurement tools. Participants’ height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index.

Neurobiological and environmental factors

Of the total sample, 24.84% had received a diagnosis of ED in their lifetime.

Moreover, 28.9% had a lifetime history of binge eating. Of these, 17.7% also had been diagnosed with an ED.

Participants with BD-II were significantly more likely than those with BD-I to report both current and lifetime BN. There were no significant differences by BD subtype in AN, ED-NOS, or binge eating.

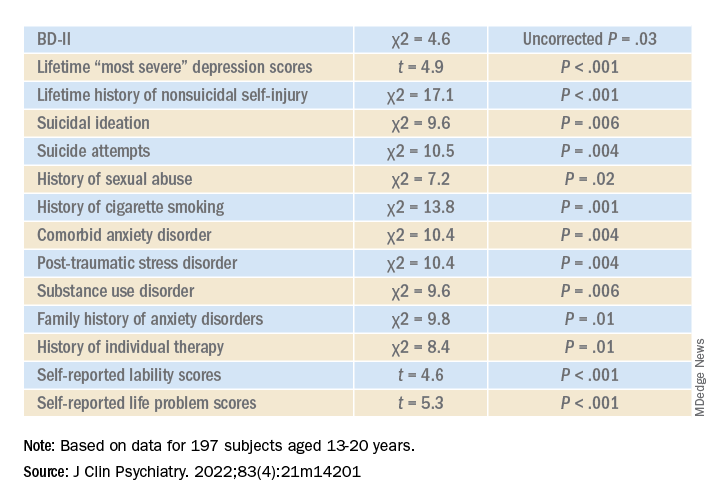

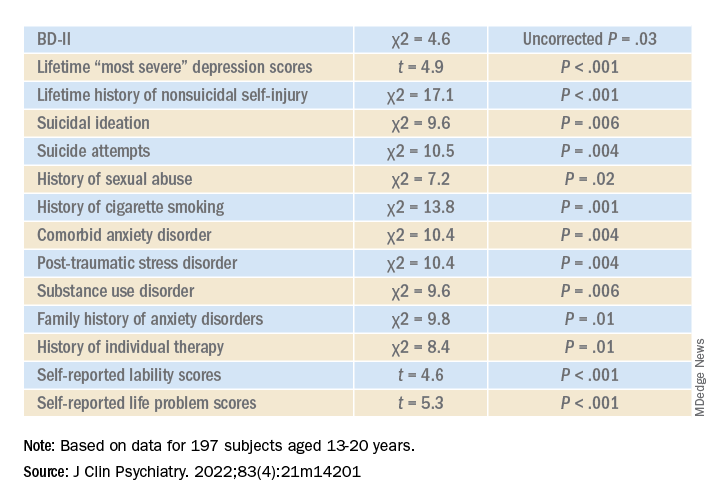

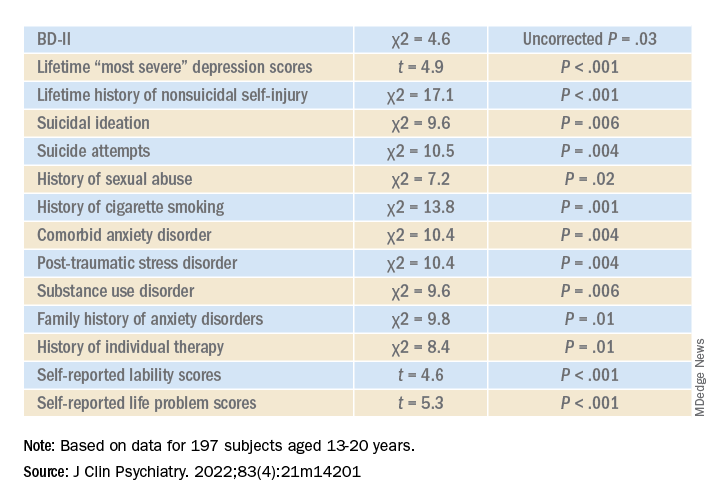

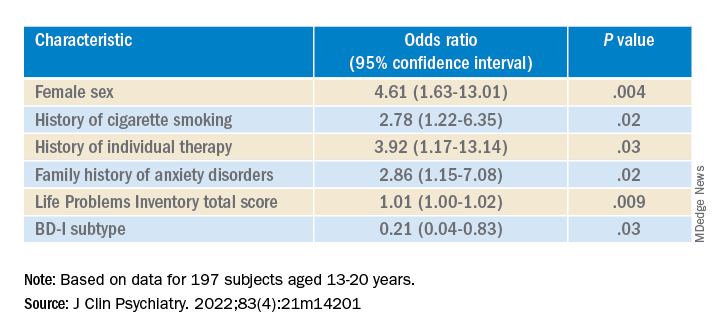

Higher correlates of clinical characteristics, psychiatric morbidity, treatment history, and dimensional traits in those with vs. those without an ED are detailed in the accompanying table.

The ED group scored significantly higher on all LPI scores, including impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, identity confusion, and interpersonal problems, compared to those without an ED. They also were less likely to report lifetime lithium use (chi2 = 7.9, P = .01).

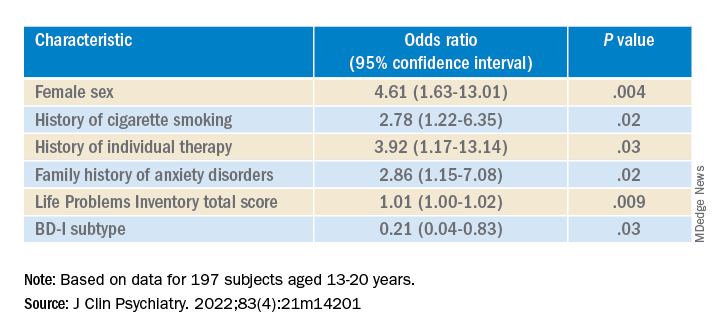

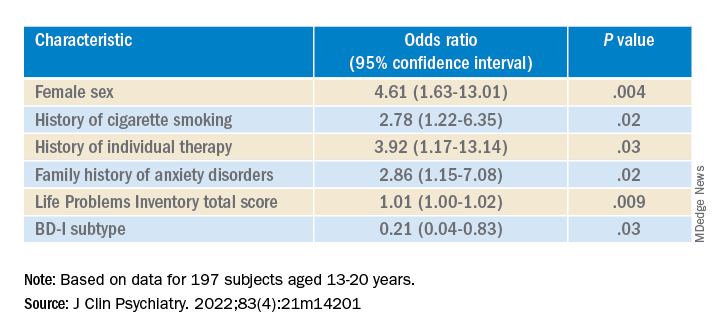

Multivariate analysis revealed that lifetime EDs were significantly associated with female sex, history of cigarette smoking, history of individual therapy, family history of anxiety, and LPI total score and were negatively associated with BD-I subtype.

“The comorbidity [between EDs and BD] could be driven by both neurobiological and environmental factors,” Dr. Khoubaeva and Dr. Goldstein noted. EDs and BD “are both illnesses that are fundamentally linked with dysfunction in reward systems – that is, there are imbalances in terms of too much or too little reward seeking.”

They added that individuals affected by these conditions have “ongoing challenges with instability of emotions and ability to manage emotions; and eating too much or too little can be a manifestation of coping with emotions.”

In addition, medications commonly used to treat BD “are known to have side effects such as weight/appetite/metabolic changes, which may make it harder to regulate eating, and which may exacerbate preexisting body image challenges.”

The researchers recommend implementing trauma-informed care, assessing and addressing suicidality and self-injury, and prioritizing therapies that target emotional dysregulation, such as dialectical behavioral therapy.

‘Clarion call’

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, said the study is “the first of its kind to comprehensively characterize the prevalence of ED in youth living with BD.

“It could be hypothesized that EDs have overlapping domain disturbances of cognitive dysfunction, such as executive function and impulse control, as well as cognitive reward processes,” said Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study.

“The data are a clarion call for clinicians to routinely screen for EDs in youth with BD and, when present, to be aware of the greater complexity, severity, and risk in this patient subpopulation. The higher prevalence of ED in youth with BD-II is an additional reminder of the severity, morbidity, and complexity of BD-II,” Dr. McIntyre said.

The study received no direct funding. It was supported by philanthropic donations to the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder and the CAMH Discovery Fund. Dr. Goldstein reports grant support from Brain Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health, and the departments of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. He also acknowledges his position as RBC investments chair in Children›s Mental Health and Developmental Psychopathology at CAMH, a joint Hospital-University chair among the University of Toronto, CAMH, and the CAMH Foundation. Ms. Khoubaeva reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC); speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied close to 200 youth with BD and found that more than 25% had a lifetime ED, which included anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and an ED not otherwise specified (NOS).

Those with comorbid EDs were more likely to be female and to have BD-II subtype. Their presentations were also more complicated and included a history of suicidality, additional psychiatric conditions, smoking, and a history of sexual abuse, as well as more severe depression and emotional instability.

“We think the take-home message is that, in addition to other more recognized psychiatric comorbidities, youth with BD are also vulnerable to developing EDs. Thus, clinicians should be routinely monitoring for eating, appetite, and body image disturbances when working with this population,” lead author Diana Khoubaeva, research analyst at the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, and senior author Benjamin Goldstein, MD, PhD, director of the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, wrote in an e-mail to this news organization.

“Given the more complicated clinical picture of youth with co-occurring BD and EDs, this combination warrants careful attention,” the investigators note.

The study was published online May 11 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Lack of research

“From the existing literature, we learned that EDs are not uncommon in individuals with BD, and that they are often associated with a more severe clinical profile,” say the researchers. “However, the majority of these studies have been limited to adult samples, and there was a real scarcity of studies that examined this co-occurrence in youth.”

This is “surprising” because EDs often have their onset in adolescence, so the researchers decided to explore the issue in their “fairly large sample of youth with BD.”

To investigate the issue, the researchers studied 197 youth (aged 13-20 years) with a diagnosis of BD (BD-I, BD-II, or BD-NOS) who were recruited between 2009 and 2017 (mean [standard deviation] age, 16.69 [1.50] years; 67.5% female).

ED diagnoses included both current and lifetime AN, BN, and ED-NOS. The researchers used the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) to determine the diagnosis of BD.

They also collected information about comorbid psychiatric disorders, as well as substance use disorders and cigarette smoking. The Life Problems Inventory (LPI) was used to identify dimensional borderline personality traits.

Information about physical and sexual abuse, suicidal ideation, nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), and affect regulation were obtained from other measurement tools. Participants’ height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index.

Neurobiological and environmental factors

Of the total sample, 24.84% had received a diagnosis of ED in their lifetime.

Moreover, 28.9% had a lifetime history of binge eating. Of these, 17.7% also had been diagnosed with an ED.

Participants with BD-II were significantly more likely than those with BD-I to report both current and lifetime BN. There were no significant differences by BD subtype in AN, ED-NOS, or binge eating.

Higher correlates of clinical characteristics, psychiatric morbidity, treatment history, and dimensional traits in those with vs. those without an ED are detailed in the accompanying table.

The ED group scored significantly higher on all LPI scores, including impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, identity confusion, and interpersonal problems, compared to those without an ED. They also were less likely to report lifetime lithium use (chi2 = 7.9, P = .01).

Multivariate analysis revealed that lifetime EDs were significantly associated with female sex, history of cigarette smoking, history of individual therapy, family history of anxiety, and LPI total score and were negatively associated with BD-I subtype.

“The comorbidity [between EDs and BD] could be driven by both neurobiological and environmental factors,” Dr. Khoubaeva and Dr. Goldstein noted. EDs and BD “are both illnesses that are fundamentally linked with dysfunction in reward systems – that is, there are imbalances in terms of too much or too little reward seeking.”

They added that individuals affected by these conditions have “ongoing challenges with instability of emotions and ability to manage emotions; and eating too much or too little can be a manifestation of coping with emotions.”

In addition, medications commonly used to treat BD “are known to have side effects such as weight/appetite/metabolic changes, which may make it harder to regulate eating, and which may exacerbate preexisting body image challenges.”

The researchers recommend implementing trauma-informed care, assessing and addressing suicidality and self-injury, and prioritizing therapies that target emotional dysregulation, such as dialectical behavioral therapy.

‘Clarion call’

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, said the study is “the first of its kind to comprehensively characterize the prevalence of ED in youth living with BD.

“It could be hypothesized that EDs have overlapping domain disturbances of cognitive dysfunction, such as executive function and impulse control, as well as cognitive reward processes,” said Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study.

“The data are a clarion call for clinicians to routinely screen for EDs in youth with BD and, when present, to be aware of the greater complexity, severity, and risk in this patient subpopulation. The higher prevalence of ED in youth with BD-II is an additional reminder of the severity, morbidity, and complexity of BD-II,” Dr. McIntyre said.

The study received no direct funding. It was supported by philanthropic donations to the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder and the CAMH Discovery Fund. Dr. Goldstein reports grant support from Brain Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health, and the departments of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. He also acknowledges his position as RBC investments chair in Children›s Mental Health and Developmental Psychopathology at CAMH, a joint Hospital-University chair among the University of Toronto, CAMH, and the CAMH Foundation. Ms. Khoubaeva reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC); speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied close to 200 youth with BD and found that more than 25% had a lifetime ED, which included anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and an ED not otherwise specified (NOS).

Those with comorbid EDs were more likely to be female and to have BD-II subtype. Their presentations were also more complicated and included a history of suicidality, additional psychiatric conditions, smoking, and a history of sexual abuse, as well as more severe depression and emotional instability.

“We think the take-home message is that, in addition to other more recognized psychiatric comorbidities, youth with BD are also vulnerable to developing EDs. Thus, clinicians should be routinely monitoring for eating, appetite, and body image disturbances when working with this population,” lead author Diana Khoubaeva, research analyst at the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, and senior author Benjamin Goldstein, MD, PhD, director of the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, wrote in an e-mail to this news organization.

“Given the more complicated clinical picture of youth with co-occurring BD and EDs, this combination warrants careful attention,” the investigators note.

The study was published online May 11 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Lack of research

“From the existing literature, we learned that EDs are not uncommon in individuals with BD, and that they are often associated with a more severe clinical profile,” say the researchers. “However, the majority of these studies have been limited to adult samples, and there was a real scarcity of studies that examined this co-occurrence in youth.”

This is “surprising” because EDs often have their onset in adolescence, so the researchers decided to explore the issue in their “fairly large sample of youth with BD.”

To investigate the issue, the researchers studied 197 youth (aged 13-20 years) with a diagnosis of BD (BD-I, BD-II, or BD-NOS) who were recruited between 2009 and 2017 (mean [standard deviation] age, 16.69 [1.50] years; 67.5% female).

ED diagnoses included both current and lifetime AN, BN, and ED-NOS. The researchers used the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) to determine the diagnosis of BD.

They also collected information about comorbid psychiatric disorders, as well as substance use disorders and cigarette smoking. The Life Problems Inventory (LPI) was used to identify dimensional borderline personality traits.

Information about physical and sexual abuse, suicidal ideation, nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), and affect regulation were obtained from other measurement tools. Participants’ height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index.

Neurobiological and environmental factors

Of the total sample, 24.84% had received a diagnosis of ED in their lifetime.

Moreover, 28.9% had a lifetime history of binge eating. Of these, 17.7% also had been diagnosed with an ED.

Participants with BD-II were significantly more likely than those with BD-I to report both current and lifetime BN. There were no significant differences by BD subtype in AN, ED-NOS, or binge eating.

Higher correlates of clinical characteristics, psychiatric morbidity, treatment history, and dimensional traits in those with vs. those without an ED are detailed in the accompanying table.

The ED group scored significantly higher on all LPI scores, including impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, identity confusion, and interpersonal problems, compared to those without an ED. They also were less likely to report lifetime lithium use (chi2 = 7.9, P = .01).

Multivariate analysis revealed that lifetime EDs were significantly associated with female sex, history of cigarette smoking, history of individual therapy, family history of anxiety, and LPI total score and were negatively associated with BD-I subtype.

“The comorbidity [between EDs and BD] could be driven by both neurobiological and environmental factors,” Dr. Khoubaeva and Dr. Goldstein noted. EDs and BD “are both illnesses that are fundamentally linked with dysfunction in reward systems – that is, there are imbalances in terms of too much or too little reward seeking.”

They added that individuals affected by these conditions have “ongoing challenges with instability of emotions and ability to manage emotions; and eating too much or too little can be a manifestation of coping with emotions.”

In addition, medications commonly used to treat BD “are known to have side effects such as weight/appetite/metabolic changes, which may make it harder to regulate eating, and which may exacerbate preexisting body image challenges.”

The researchers recommend implementing trauma-informed care, assessing and addressing suicidality and self-injury, and prioritizing therapies that target emotional dysregulation, such as dialectical behavioral therapy.

‘Clarion call’

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, said the study is “the first of its kind to comprehensively characterize the prevalence of ED in youth living with BD.

“It could be hypothesized that EDs have overlapping domain disturbances of cognitive dysfunction, such as executive function and impulse control, as well as cognitive reward processes,” said Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study.

“The data are a clarion call for clinicians to routinely screen for EDs in youth with BD and, when present, to be aware of the greater complexity, severity, and risk in this patient subpopulation. The higher prevalence of ED in youth with BD-II is an additional reminder of the severity, morbidity, and complexity of BD-II,” Dr. McIntyre said.

The study received no direct funding. It was supported by philanthropic donations to the Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder and the CAMH Discovery Fund. Dr. Goldstein reports grant support from Brain Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health, and the departments of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. He also acknowledges his position as RBC investments chair in Children›s Mental Health and Developmental Psychopathology at CAMH, a joint Hospital-University chair among the University of Toronto, CAMH, and the CAMH Foundation. Ms. Khoubaeva reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC); speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Alcohol, degraded sleep related in young adults

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – Sleep and alcohol consumption in young adults seems to follow a “vicious cycle,” as one observer called it. and those who went to bed earlier and slept longer tended to drink less the next day, a study of drinking and sleeping habits in 21- to 29-year-olds found.

“Sleep is a potential factor that we could intervene on to really identify how to improve drinking behaviors among young adults,” David Reichenberger, a graduate student at Penn State University, University Park, said in an interview after he presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This is one of the few studies of alcohol consumption and sleep patterns that used an objective measure of alcohol consumption, Mr. Reichenberger said. The study evaluated sleep and alcohol consumption patterns in 222 regularly drinking young adults over 6 consecutive days. Study participants completed morning smartphone-based questionnaires, reporting their previous night’s bedtime, sleep duration, sleep quality, and number of drinks consumed. They also wore an alcohol monitor that continuously measured their transdermal alcohol consumption (TAC).

The study analyzed the data using two sets of multilevel models: A linear model that looked at how each drinking predictor was associated with each sleep variable and a Poisson model to determine how sleep predicted next-day alcohol use.

“We found that higher average peak TAC – that is, how intoxicated they got – was associated with a 19-minute later bedtime among young adults,” Mr. Reichenberger said. “Later bedtimes were then associated with a 26% greater TAC among those adults” (P < .02).

Patterns of alcohol consumption and sleep

On days when participants recorded a higher peak TAC, bedtime was delayed, sleep duration was shorter, and subjective sleep quality was worse, he said. However, none of the sleep variables predicted next-day peak TAC.

“We found an association between the duration of the drinking episode and later bedtimes among young adults,” he added. “And on days when the drinking episodes were longer, subsequent sleep was delayed and sleep quality was worse. But we also found that after nights when they had a later bedtime, next-day drinking episodes were about 7% longer.”

Conversely, young adults who had earlier bedtimes and longer sleep durations tended to consume fewer drinks and they achieved lower intoxication levels the next day, Mr. Reichenberger said.

Between-person results showed that young adults who tended to go to bed later drank on average 24% more the next day (P < .01). Also, each extra hour of sleep was associated with a 14% decrease in drinking the next day (P < .03).

Participants who drank more went to bed on average 12-19 minutes later (P < .01) and slept 5 fewer minutes (P < .01). Within-person results showed that on nights when participants drank more than usual they went to bed 8-13 minutes later (P < .01), slept 2-4 fewer minutes (P < .03), and had worse sleep quality (P < .01).

Mr. Reichenberger acknowledged one limitation of the study: Measuring sleep and alcohol consumption patterns over 6 days might not be long enough. Future studies should address that.

A ‘vicious cycle’

Hans P.A. Van Dongen, PhD, director of the Sleep and Performance Research Center at Washington State University, Spokane, said in an interview that the findings imply a “vicious cycle” between sleep and alcohol consumption. “You create a problem and then it perpetuates itself or reinforces itself.”

In older adults, alcohol tends to act as a “sleep aid,” Dr. Van Dongen noted. “Then it disrupts their sleep later on and then the next night they need to use the sleep aid again because they had a really poor night and they’re tired and they want to fall asleep.”

He added: “I think what is new here is that’s not very likely the mechanism that they’re using alcohol as a sleep aid in younger adults that we see in older adults, so I think there is a new element to it. Now does anybody know how that works exactly? No, that’s the next thing.”

The Penn State study identifies “a signal there that needs to be followed up on,” Dr. Van Dongen said. “There’s something nature’s trying to tell us but it’s not exactly clear what it’s trying to tell us.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse provided funding for the study. Mr. Reichenberger has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Van Dongen has no disclosures to report.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – Sleep and alcohol consumption in young adults seems to follow a “vicious cycle,” as one observer called it. and those who went to bed earlier and slept longer tended to drink less the next day, a study of drinking and sleeping habits in 21- to 29-year-olds found.

“Sleep is a potential factor that we could intervene on to really identify how to improve drinking behaviors among young adults,” David Reichenberger, a graduate student at Penn State University, University Park, said in an interview after he presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This is one of the few studies of alcohol consumption and sleep patterns that used an objective measure of alcohol consumption, Mr. Reichenberger said. The study evaluated sleep and alcohol consumption patterns in 222 regularly drinking young adults over 6 consecutive days. Study participants completed morning smartphone-based questionnaires, reporting their previous night’s bedtime, sleep duration, sleep quality, and number of drinks consumed. They also wore an alcohol monitor that continuously measured their transdermal alcohol consumption (TAC).

The study analyzed the data using two sets of multilevel models: A linear model that looked at how each drinking predictor was associated with each sleep variable and a Poisson model to determine how sleep predicted next-day alcohol use.

“We found that higher average peak TAC – that is, how intoxicated they got – was associated with a 19-minute later bedtime among young adults,” Mr. Reichenberger said. “Later bedtimes were then associated with a 26% greater TAC among those adults” (P < .02).

Patterns of alcohol consumption and sleep

On days when participants recorded a higher peak TAC, bedtime was delayed, sleep duration was shorter, and subjective sleep quality was worse, he said. However, none of the sleep variables predicted next-day peak TAC.

“We found an association between the duration of the drinking episode and later bedtimes among young adults,” he added. “And on days when the drinking episodes were longer, subsequent sleep was delayed and sleep quality was worse. But we also found that after nights when they had a later bedtime, next-day drinking episodes were about 7% longer.”

Conversely, young adults who had earlier bedtimes and longer sleep durations tended to consume fewer drinks and they achieved lower intoxication levels the next day, Mr. Reichenberger said.

Between-person results showed that young adults who tended to go to bed later drank on average 24% more the next day (P < .01). Also, each extra hour of sleep was associated with a 14% decrease in drinking the next day (P < .03).

Participants who drank more went to bed on average 12-19 minutes later (P < .01) and slept 5 fewer minutes (P < .01). Within-person results showed that on nights when participants drank more than usual they went to bed 8-13 minutes later (P < .01), slept 2-4 fewer minutes (P < .03), and had worse sleep quality (P < .01).

Mr. Reichenberger acknowledged one limitation of the study: Measuring sleep and alcohol consumption patterns over 6 days might not be long enough. Future studies should address that.

A ‘vicious cycle’

Hans P.A. Van Dongen, PhD, director of the Sleep and Performance Research Center at Washington State University, Spokane, said in an interview that the findings imply a “vicious cycle” between sleep and alcohol consumption. “You create a problem and then it perpetuates itself or reinforces itself.”

In older adults, alcohol tends to act as a “sleep aid,” Dr. Van Dongen noted. “Then it disrupts their sleep later on and then the next night they need to use the sleep aid again because they had a really poor night and they’re tired and they want to fall asleep.”

He added: “I think what is new here is that’s not very likely the mechanism that they’re using alcohol as a sleep aid in younger adults that we see in older adults, so I think there is a new element to it. Now does anybody know how that works exactly? No, that’s the next thing.”

The Penn State study identifies “a signal there that needs to be followed up on,” Dr. Van Dongen said. “There’s something nature’s trying to tell us but it’s not exactly clear what it’s trying to tell us.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse provided funding for the study. Mr. Reichenberger has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Van Dongen has no disclosures to report.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – Sleep and alcohol consumption in young adults seems to follow a “vicious cycle,” as one observer called it. and those who went to bed earlier and slept longer tended to drink less the next day, a study of drinking and sleeping habits in 21- to 29-year-olds found.

“Sleep is a potential factor that we could intervene on to really identify how to improve drinking behaviors among young adults,” David Reichenberger, a graduate student at Penn State University, University Park, said in an interview after he presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This is one of the few studies of alcohol consumption and sleep patterns that used an objective measure of alcohol consumption, Mr. Reichenberger said. The study evaluated sleep and alcohol consumption patterns in 222 regularly drinking young adults over 6 consecutive days. Study participants completed morning smartphone-based questionnaires, reporting their previous night’s bedtime, sleep duration, sleep quality, and number of drinks consumed. They also wore an alcohol monitor that continuously measured their transdermal alcohol consumption (TAC).

The study analyzed the data using two sets of multilevel models: A linear model that looked at how each drinking predictor was associated with each sleep variable and a Poisson model to determine how sleep predicted next-day alcohol use.

“We found that higher average peak TAC – that is, how intoxicated they got – was associated with a 19-minute later bedtime among young adults,” Mr. Reichenberger said. “Later bedtimes were then associated with a 26% greater TAC among those adults” (P < .02).

Patterns of alcohol consumption and sleep

On days when participants recorded a higher peak TAC, bedtime was delayed, sleep duration was shorter, and subjective sleep quality was worse, he said. However, none of the sleep variables predicted next-day peak TAC.

“We found an association between the duration of the drinking episode and later bedtimes among young adults,” he added. “And on days when the drinking episodes were longer, subsequent sleep was delayed and sleep quality was worse. But we also found that after nights when they had a later bedtime, next-day drinking episodes were about 7% longer.”

Conversely, young adults who had earlier bedtimes and longer sleep durations tended to consume fewer drinks and they achieved lower intoxication levels the next day, Mr. Reichenberger said.

Between-person results showed that young adults who tended to go to bed later drank on average 24% more the next day (P < .01). Also, each extra hour of sleep was associated with a 14% decrease in drinking the next day (P < .03).

Participants who drank more went to bed on average 12-19 minutes later (P < .01) and slept 5 fewer minutes (P < .01). Within-person results showed that on nights when participants drank more than usual they went to bed 8-13 minutes later (P < .01), slept 2-4 fewer minutes (P < .03), and had worse sleep quality (P < .01).

Mr. Reichenberger acknowledged one limitation of the study: Measuring sleep and alcohol consumption patterns over 6 days might not be long enough. Future studies should address that.

A ‘vicious cycle’

Hans P.A. Van Dongen, PhD, director of the Sleep and Performance Research Center at Washington State University, Spokane, said in an interview that the findings imply a “vicious cycle” between sleep and alcohol consumption. “You create a problem and then it perpetuates itself or reinforces itself.”

In older adults, alcohol tends to act as a “sleep aid,” Dr. Van Dongen noted. “Then it disrupts their sleep later on and then the next night they need to use the sleep aid again because they had a really poor night and they’re tired and they want to fall asleep.”

He added: “I think what is new here is that’s not very likely the mechanism that they’re using alcohol as a sleep aid in younger adults that we see in older adults, so I think there is a new element to it. Now does anybody know how that works exactly? No, that’s the next thing.”

The Penn State study identifies “a signal there that needs to be followed up on,” Dr. Van Dongen said. “There’s something nature’s trying to tell us but it’s not exactly clear what it’s trying to tell us.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse provided funding for the study. Mr. Reichenberger has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Van Dongen has no disclosures to report.

At SLEEP 2022

Trans teens less likely to commit acts of sexual violence, says new study

Transgender and nonbinary adolescents are twice as likely to experience sexual violence as their cisgendered peers but are less likely to attempt rape or commit sexual assault, researchers have found.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, is among the first on the sexual violence that trans, nonbinary, and other gender nonconforming adolescents experience. Previous studies have focused on adults.

“In the busy world of clinical care, it is essential that clinicians be aware of potential disparities their patients are navigating,” said Michele Ybarra, PhD, MPH, president and research director of the Center for Innovative Public Health Research, San Clemente, California, who led the study. “This includes sexual violence victimization for gender minority youth and the need to talk about consent and boundaries for youth of all genders.”

Dr. Ybarra said that while clinicians may be aware that transgender young people face stigma, discrimination, and bullying, they may not be aware that trans youth are also the targets of sexual violence.

Studies indicate that health care providers and communities have significant misconceptions about sexually explicit behavior among trans and nonbinary teens. Misconceptions can lead to discrimination, resulting in higher rates of drug abuse, dropping out of school, suicide, and homelessness.

Dr. Ybarra and her colleagues surveyed 911 trans, nonbinary, or questioning youth on Instagram and Facebook through a collaboration with Growing Up With Media, a national longitudinal survey designed to investigate sexual violence during adolescence.

They also surveyed 3,282 cisgender persons aged 14-16 years who were recruited to the study between June 2018 and March 2020. The term “cisgender” refers to youth who identify with their gender at birth.

The questionnaires asked teens about gender identity, race, economic status, and support systems at home. Factors associated with not experiencing sexual violence included having a strong network of friends, family, and educators; involvement in the community; and having people close who affirm their gender identity.

More than three-fourths (78%) of youth surveyed identified as cisgender, 13.9% identified as questioning, and 7.9% identified as transgender.

Roughly two-thirds (67%) of transgender adolescents said they had experienced serious sexual violence, 73% reported experiencing violence in their communities, and 63% said they had been exposed to aggressive behavior. In contrast, 6.7% of trans youth said they had ever committed sexual violence, while 7.4% of cisgender teens surveyed, or 243 students, said they had done so.

“The relative lack of visibility of gender minority youth in sexual violence research is unacceptable,” Dr. Ybarra told this news organization. “To be counted, one needs to be seen. We aimed to start addressing this exclusion with the current study.”

The findings provide a lens into the levels of sexual violence that LGBTQIA+ youth experience and an opportunity to provide more inclusive care, according to Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, FSAHM, Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics, director of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, and medical director of community and population health at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study.

“There are unfortunately pervasive and harmful stereotypes in our society about the ‘sexual deviancy’ attributed to LGBTQIA+ individuals,” Dr. Miller told this news organization. “This study adds to the research literature that counters and challenges these harmful – and inaccurate – perceptions.”

Dr. Miller said clinicians can help this population by offering youth accurate information about relevant support and services, including how to help a friend.

Programs that providers could incorporate include gender transformative approaches, which guide youth to examine gender norms and inequities and that develop leadership skills.

Such programs are more common outside the United States and have been shown to decrease LGBTQIA+ youth exposure to sexual violence, she said.

Dr. Miller said more research is needed to understand the contexts in which gender minority youth experience sexual violence to guide prevention efforts: “We need to move beyond individual-focused interventions to considering community-level interventions to create safer and more inclusive spaces for all youth.”

Dr. Miller has received royalties for writing content for UptoDate Wolters Kluwer outside of the current study. Dr. Ybarra has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender and nonbinary adolescents are twice as likely to experience sexual violence as their cisgendered peers but are less likely to attempt rape or commit sexual assault, researchers have found.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, is among the first on the sexual violence that trans, nonbinary, and other gender nonconforming adolescents experience. Previous studies have focused on adults.

“In the busy world of clinical care, it is essential that clinicians be aware of potential disparities their patients are navigating,” said Michele Ybarra, PhD, MPH, president and research director of the Center for Innovative Public Health Research, San Clemente, California, who led the study. “This includes sexual violence victimization for gender minority youth and the need to talk about consent and boundaries for youth of all genders.”

Dr. Ybarra said that while clinicians may be aware that transgender young people face stigma, discrimination, and bullying, they may not be aware that trans youth are also the targets of sexual violence.

Studies indicate that health care providers and communities have significant misconceptions about sexually explicit behavior among trans and nonbinary teens. Misconceptions can lead to discrimination, resulting in higher rates of drug abuse, dropping out of school, suicide, and homelessness.

Dr. Ybarra and her colleagues surveyed 911 trans, nonbinary, or questioning youth on Instagram and Facebook through a collaboration with Growing Up With Media, a national longitudinal survey designed to investigate sexual violence during adolescence.

They also surveyed 3,282 cisgender persons aged 14-16 years who were recruited to the study between June 2018 and March 2020. The term “cisgender” refers to youth who identify with their gender at birth.

The questionnaires asked teens about gender identity, race, economic status, and support systems at home. Factors associated with not experiencing sexual violence included having a strong network of friends, family, and educators; involvement in the community; and having people close who affirm their gender identity.

More than three-fourths (78%) of youth surveyed identified as cisgender, 13.9% identified as questioning, and 7.9% identified as transgender.

Roughly two-thirds (67%) of transgender adolescents said they had experienced serious sexual violence, 73% reported experiencing violence in their communities, and 63% said they had been exposed to aggressive behavior. In contrast, 6.7% of trans youth said they had ever committed sexual violence, while 7.4% of cisgender teens surveyed, or 243 students, said they had done so.

“The relative lack of visibility of gender minority youth in sexual violence research is unacceptable,” Dr. Ybarra told this news organization. “To be counted, one needs to be seen. We aimed to start addressing this exclusion with the current study.”

The findings provide a lens into the levels of sexual violence that LGBTQIA+ youth experience and an opportunity to provide more inclusive care, according to Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, FSAHM, Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics, director of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, and medical director of community and population health at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study.

“There are unfortunately pervasive and harmful stereotypes in our society about the ‘sexual deviancy’ attributed to LGBTQIA+ individuals,” Dr. Miller told this news organization. “This study adds to the research literature that counters and challenges these harmful – and inaccurate – perceptions.”

Dr. Miller said clinicians can help this population by offering youth accurate information about relevant support and services, including how to help a friend.

Programs that providers could incorporate include gender transformative approaches, which guide youth to examine gender norms and inequities and that develop leadership skills.

Such programs are more common outside the United States and have been shown to decrease LGBTQIA+ youth exposure to sexual violence, she said.

Dr. Miller said more research is needed to understand the contexts in which gender minority youth experience sexual violence to guide prevention efforts: “We need to move beyond individual-focused interventions to considering community-level interventions to create safer and more inclusive spaces for all youth.”

Dr. Miller has received royalties for writing content for UptoDate Wolters Kluwer outside of the current study. Dr. Ybarra has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender and nonbinary adolescents are twice as likely to experience sexual violence as their cisgendered peers but are less likely to attempt rape or commit sexual assault, researchers have found.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, is among the first on the sexual violence that trans, nonbinary, and other gender nonconforming adolescents experience. Previous studies have focused on adults.

“In the busy world of clinical care, it is essential that clinicians be aware of potential disparities their patients are navigating,” said Michele Ybarra, PhD, MPH, president and research director of the Center for Innovative Public Health Research, San Clemente, California, who led the study. “This includes sexual violence victimization for gender minority youth and the need to talk about consent and boundaries for youth of all genders.”

Dr. Ybarra said that while clinicians may be aware that transgender young people face stigma, discrimination, and bullying, they may not be aware that trans youth are also the targets of sexual violence.

Studies indicate that health care providers and communities have significant misconceptions about sexually explicit behavior among trans and nonbinary teens. Misconceptions can lead to discrimination, resulting in higher rates of drug abuse, dropping out of school, suicide, and homelessness.

Dr. Ybarra and her colleagues surveyed 911 trans, nonbinary, or questioning youth on Instagram and Facebook through a collaboration with Growing Up With Media, a national longitudinal survey designed to investigate sexual violence during adolescence.

They also surveyed 3,282 cisgender persons aged 14-16 years who were recruited to the study between June 2018 and March 2020. The term “cisgender” refers to youth who identify with their gender at birth.

The questionnaires asked teens about gender identity, race, economic status, and support systems at home. Factors associated with not experiencing sexual violence included having a strong network of friends, family, and educators; involvement in the community; and having people close who affirm their gender identity.

More than three-fourths (78%) of youth surveyed identified as cisgender, 13.9% identified as questioning, and 7.9% identified as transgender.