User login

Bipolar disorder and substance abuse: Overcome the challenges of ‘dual diagnosis’ patients

After testing positive for cocaine on a recent court-mandated urine drug screen, Mr. M, age 49, is referred by his parole officer for psychiatric and substance abuse treatment. Mr. M has bipolar I disorder and alcohol, cocaine, and opioid dependence. He says he has been hospitalized or incarcerated at least once each year for the past 22 years. Mr. M has seen numerous psychiatrists as an outpatient, but rarely for more than 2 to 3 months and has not taken any psychotropics for more than 5 months.

Approximately 1 week before his recent urine drug screen, Mr. M became euphoric, stopped sleeping for several days, and spent $2,000 on cocaine and “escorts.” He reports that each day he smokes 30 cigarettes and drinks 1 pint of liquor and prefers to use cocaine and opiates by IV injection. Several years ago Mr. M was diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) but received no further workup or treatment. Although he denies manic or psychotic symptoms, Mr. M is observed speaking to unseen others in the waiting room and has difficulty remaining still during his interview. His chief concern is insomnia, stating, “Doc, I just need something to help me sleep.”

The high prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in persons with bipolar disorder (BD) is well documented.1,2 Up to 60% of bipolar patients develop an SUD at some point in their lives.3-5 Alcohol use disorders are particularly common among BD patients, with a lifetime prevalence of roughly 50%.2-5 Recent epidemiologic data indicate that 38% of persons with bipolar I disorder and 19% of those with bipolar II disorder meet criteria for alcohol dependence.5 Comorbid SUDs in patients with BD are associated with:

- poor treatment compliance

- longer and more frequent mood episodes

- more mixed episodes

- more hospitalizations

- more frequent suicide attempts.1,2

The impact of co-occurring SUDs on suicidality is particularly high among those with bipolar I disorder.6

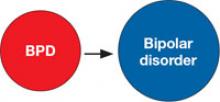

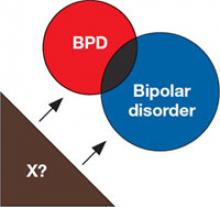

Frequently referred to as “dual diagnosis” conditions, co-occurring BD and SUDs may be more accurately envisioned as multi-morbid, rather than comorbid, illnesses. Data from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network suggest that 42% of BD patients have a lifetime history of ≥2 comorbid axis I disorders.7 Rates of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder are particularly high in BD patients with co-occurring SUDs.8,9 In addition, the presence of 1 SUD may mark the presence of other SUDs; for example, alcohol dependence is strongly associated with polysubstance abuse, especially in females with BD.8 Furthermore, medical comorbidities that impact treatment decisions also are highly prevalent in BD patients with comorbid SUDs.10 In particular, HCV rates are higher in persons with BD compared with the general population,11 and are >5 times as likely in bipolar patients with co-occurring SUDs.12

Unfortunately, limited treatment research guides clinical management of comorbid BD and SUDs.2,13,14 Clinical trials of medications for BD traditionally have excluded patients with SUDs, and persons with serious mental illness usually are ineligible for SUD treatment studies.13 Furthermore, the few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in persons with both illnesses have been constrained by relatively small sample sizes and low retention rates. In the absence of a definitive consensus for optimal treatment, this article outlines general clinical considerations and an integrated approach to assessing and managing this complex patient population.

Birds of a feather

Multiple hypotheses try to account for the high rate of SUDs in patients with BD (Table 1), but none fully explain the complex interaction observed clinically.14,15 Substance dependence and BD are chronic remitting/relapsing disorders with heterogeneous presentations and highly variable natural histories. As with SUDs, BD may go undiagnosed and untreated for years, coming to clinical attention only after substantial disease progression.16

The fluctuating illness course in BD and SUDs makes diagnosis and treatment difficult. Symptomatic periods often are interrupted by spontaneous remissions and longer—although usually temporary—periods of perceived control. Both BD and SUDs may be associated with profound mood instability, increased impulsivity, altered responsiveness to reward, and impaired executive function.17 Finally, the high degree of heritability in BD18 and many SUDs19 may make treatment engagement more difficult if either disorder is present in multiple family members because of:

- potential for greater clinical severity

- reduced psychosocial resources

- altered familial behavioral norms that may impede the patient’s recognition of illness.

Denial of illness is a critical symptom that may fluctuate with disease course in both disorders. Persons with BD or SUDs may be least likely to recognize that they are ill during periods of highest symptom severity. Accordingly, treatment adherence in patients with either disorder may be limited at baseline and decline further when the 2 illnesses co-occur.20

Involvement in the criminal justice system and medical comorbidities, particularly HCV, also complicate diagnosis and treatment of BD patients with SUDs. For more information about these topics, see Box1 and Box2.

Table 1

Why is substance abuse so prevalent among bipolar patients?

| Proposed hypothesis | Selected limitations of this hypothesis |

|---|---|

| Self-medication: substance abuse occurs as an attempt to regulate mood | High rates of substance use during euthymia; high prevalence of alcohol/depressant use during depressive phase, stimulant use during manic phase |

| Common neurobiologic or genetic risk factors | Specific evidence from linkage/association studies currently is lacking |

| Substance use occurs as a symptom of bipolar disorder | High percentage of patients with bipolar disorder do not have SUDs; there is a poor correlation of onset, course of bipolar, and SUD symptoms |

| Substance use unmasks bipolar disorder or a bipolar diathesis | Emergence of mania before SUD is common and predictive of more severe course of bipolar disorder |

| High comorbidity rates are an artifact of misdiagnosis based on overlapping symptoms and poor diagnostic boundaries | Very high prevalence of SUDs also is observed in longitudinal studies of patients initially hospitalized for mania |

| SUDs: substance use disorders | |

| Source: References 14,15 | |

Integrated clinical management

Assessment. Although not intended to be comprehensive, suggestions for routine assessment of patients with suspected SUDs and/or BD are listed in Table 2. Because clinicians may encounter dual diagnosis patients in general psychiatric clinics or specialty (addiction or mood disorder) clinics, it is useful to obtain a thorough substance use history in all patients with known or suspected BD as well as a thorough history of hypomania/mania and depression in all patients with addictive disorders. BD diagnoses by self-report or chart history in patients with SUDs should be considered cautiously because BD often is overdiagnosed in persons engaged in active substance abuse or experiencing withdrawal.21 If past or present mood symptoms and substance use have co-occurred, further focused assessment of mood symptoms before alcohol and drug use or during extended periods of abstinence are necessary to make the diagnosis of bipolar disorder with confidence. Family history of SUDs and/or BD are neither necessary nor sufficient for either diagnosis; however, collateral information from family or significant others could help make the diagnosis and may identify aids and obstacles to treatment planning and engagement.

When a patient’s clinical history strongly supports the diagnoses of BD and co-occurring SUDs, more detailed inquiry is warranted. Determining the patient’s age at onset of each disorder may have prognostic value because onset of mania before SUDs developed, especially in adolescence, may predict a more severe course of both illnesses.22 A complete alcohol use history should include routine questioning about past withdrawal. Previous withdrawal seizures in an actively drinking BD patient may tip the balance toward adding an anticonvulsant for mood stabilization. A thorough SUD history should elicit information about polysubstance abuse or dependence and include screening for injection drug use and other risk factors for HCV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), such as hypersexuality during manic or hypomanic episodes. Document the date of the last screening for HCV/ HIV in BD patients at high risk of infection. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all patients at high risk for HIV consider voluntary screening at least annually.23

Assess your patient’s historical and ongoing alcohol and other drug abuse at the initial visit, and continue to monitor substance use at all subsequent visits, especially in patients with HCV. When feasible, order urine drug screening and laboratory testing for alcohol use biomarkers such as carbohydrate-deficient transferrin and gamma-glutamyltransferase to supplement self-report data, especially in patients with poor insight or low motivation. Assess suicidal ideation and any changes in suicide risk factors at every visit.

Treatment. No biologic therapies have been FDA-approved for treating patients with co-occurring BD and SUDs. Comorbid SUDs in BD patients—as well as rapid cycling and mixed mood episodes, both of which are more common in patients with comorbid SUDs—predict poor response to lithium.17 However, the evidence base for optimal pharmacotherapy remains extremely limited. Published double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs in persons with BD and co-morbid SUDs are limited to only 1 trial each of lithium, carbamazepine, quetiapine, and naltrexone, and 2 comparisons of lithium plus divalproex vs lithium alone (Table 3).24-29

Salloum et al24 reported that bipolar I disorder patients with alcohol dependence who received divalproex plus lithium as maintenance treatment had fewer heavy drinking days and fewer drinks per heavy drinking day than those receiving lithium plus placebo. However, the addition of divalproex did not improve manic or depressive symptoms, and depression remission rates remained relatively low in both groups. A recent 6-month study comparing lithium vs lithium plus divalproex in patients with SUDs and rapid-cycling BD found no additional benefit of divalproex over lithium monotherapy in retention, mood, or substance use outcomes.28 However, modest evidence that anticonvulsants such as valproic acid and carbamazepine may help treat acute alcohol withdrawal2 could support their preferential use as mood stabilizers over lithium in actively drinking BD patients.

Research underscores the difficulty in keeping dual diagnosis patients in treatment. Salloum et al24 reported that only one-third of randomized subjects completed the 24-week study. In the Kemp study,28 79% of 149 recruited subjects failed to complete the lead-in stabilization phase. Of the 31 remaining subjects who were randomized to lithium or lithium/divalproex combination, only 8 (26% of those randomized, 5% of those recruited) completed the 6-month trial.

Substance abuse is associated with significantly decreased treatment adherence in persons with BD20 and may affect medication choice. For example, caution may be warranted in the use of lamotrigine in substance-abusing patients with poor adherence because re-titration from the starting dose is recommended if the medicine has been missed for a consecutive period exceeding 5 half-lives of the drug.30

Notable progress has been made in developing psychosocial treatments for comorbid SUDs and BD. Integrated group therapy has been designed to address the 2 disorders simultaneously by emphasizing the relationship between the disorders and highlighting similarities in cognitive and behavioral change that promote recovery in both.31 In a recent well-controlled RCT, this approach reduced alcohol and other drug use to approximately one-half the levels observed in those who received only group drug counseling.31

Research suggests that an integrated approach that encompasses psychiatric, medical, psychosocial, and legal dimensions simultaneously may be most effective. For patients such as Mr. M, this would include aggressively treating mood symptoms while employing motivational interviewing techniques to improve engagement in substance dependence treatment. If possible, involving family members, parole officials, housing agencies, and other public assistance workers in the treatment plan may increase treatment adherence and reduce loss of contact during illness exacerbations. Stabilization of substance use and psychiatric morbidity should be accompanied by timely evaluation of HCV and other medical comorbidities in order to improve long-term prognosis.

Table 2

Assessing patients you suspect have comorbid BD and SUDs

| Initial assessment |

|---|

Thorough substance use history in all patients with known or suspected bipolar disorder:

|

Thorough evaluation of any history of hypomania/mania and depression in all patients with known or suspected SUDs:

|

| Assess risk factors, screening status for hepatitis C, HIV |

| Obtain collateral information from family and significant others if feasible and appropriate |

| Detailed assessment of suicide risk |

| Follow-up assessments |

| Substance use since last visit by self-report |

| Consider UDS, CDT, GGT |

| Medication adherence |

| Detailed assessment of suicide risk |

| BD: bipolar disorder; CDT: carbohydrate-deficient transferrin; GGT: gamma-glutamyltransferase; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; SUDs: substance use disorders; UDS: urine drug screen |

Table 3

Pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and co-occurring SUDs

| Study | Diagnoses/N* | Medications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salloum et al, 200524 | BD I, alcohol dependence. N=59 [20] | Divalproex + lithium vs lithium, 24 weeks | Decreased number of heavy drinking days, fewer drinks per heavy drinking day |

| Geller et al, 199825 | BD I, BP II, MDD (adolescents); alcohol, cannabis abuse. N=25 [21] | Lithium, 6 weeks | Decreased cannabis-positive urine drug screen (lithium > placebo) |

| Brady et al, 200226 | BD I, BD II, cyclothymia; cocaine dependence. N=57 | Carbamazepine, 12 weeks | Trend toward longer time to cocaine use |

| Brown et al, 200827 | BD I, BD II; N=102 | Quetiapine, 12 weeks | Decreased HAM-D scores (quetiapine > placebo) |

| Kemp et al, 200928 | BD I, BD II, rapid cycling; alcohol, cannabis, cocaine abuse or dependence. N=31 [8] | Divalproex + lithium vs lithium, 6 months | No group differences |

| Brown et al, 200929 | BD I, BD II; alcohol dependence. N=50 [26] | Naltrexone, 12 weeks | Trend toward increased probability of no drinking days |

| * N=number of subjects randomized to double-blind treatment. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of subjects who completed all study visits (when reported) | |||

| BD: bipolar disorder; HAM-D: 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MDD: major depressive disorder; SUDs: substance use disorders | |||

Related Resources

- International Society for Bipolar Disorders. www.isbd.org.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. www.niaaa.nih.gov.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. www.nida.nih.gov.

Drug Brand Names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Divalproex/valproic acid • Depakote

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid

- Naltrexone • ReVia

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

Disclosure

Dr. Tolliver receives research grant funding from Forest Laboratories and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Neither source influenced the content or submission of this manuscript.

A recent analysis of data from >65,000 veterans found bipolar patients with comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs) were 7 times more likely to have hepatitis C virus (HCV) than patients with no serious mental illness.a Matthews and colleagues found that 29.6% of persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) and SUDs tested positive for HCV—roughly 5 times the relative risk of patients without either diagnosis.b The high prevalence of HCV in patients with comorbid BD and SUDs may be the result of injection drug use, increased risky sexual behavior while manic or intoxicated, or both.

HCV has multiple treatment implications for these patients. Alcohol abuse and dependence are the most common SUDs that co-occur with BD,c-e and patients with HCV who drink alcohol excessively have more severe hepatic fibrosis, accelerated disease progression, and higher rates of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma than HCV patients who do not drink.f Medications commonly used to treat BD or alcohol dependence may have adverse effects on the liver and require more careful monitoring in the presence of HCV infection. For example, valproic acid has been reported to improve drinking outcomes in alcohol-dependent patients with BDg but has been associated with higher rates of marked hepatic transaminase elevation in patients with HCV infection compared with those without HCV.h Marked elevation of hepatic transaminases may be observed in HCV-infected individuals treated with other medications such as lithium or antidepressants,h and valproic acid use is not an absolute contraindication in HCV patients. Nevertheless, the effects of valproic acid in HCV-infected BD patients who drink alcohol are unknown and therefore cautious and frequent monitoring of hepatic enzymes are warranted in this population.

Finally, both SUDs and BD complicate HCV treatment. In a database review of >113,000 veterans with HCV infection, Butt and colleagues found that individuals with BD accounted for 10.4% of the HCV-infected sample but only 5% of those who received HCV treatment.i Similarly, patients with alcohol abuse or dependence made up 44.3% of the HCV-infected sample but only 28.9% of those who received HCV treatment.

Because the rate of liver biopsy in untreated patients was low, the decision not to treat appeared to be based more often on other criteria. This is not surprising; pegylated interferon-alfa—the most effective treatment for chronic HCV—has been associated with multiple neuropsychiatric symptoms observed in BD, including depression, mania, psychosis, and suicidal ideation.j Emergence of severe psychiatric complications usually results in permanent discontinuation of interferon treatment. Likewise, the presence of alcohol abuse or other SUDs is a strong negative predictor of interferon treatment response and retention and generally has been considered a relative contraindication for interferon initiation.f

References

a. Himelhoch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:30-37.

b. Matthews AM, Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, et al. Hepatitis C testing and infection rates in bipolar patients with and without comorbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:266-270.

c. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

d. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830-842.

e. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543-552.

f. Bhattacharya R, Shuhart M. Hepatitis C and alcohol. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:242-252.

g. Salloum IM, Cornelius JR, Daley DC, et al. Efficacy of valproate maintenance in patients with bipolar disorder and alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:37-45.

h. Felker BL, Sloan KL, Dominitz JA, et al. The safety of valproic acid use for patients with hepatitis C infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:174-178.

i. Butt AA, Justice AC, Skanderson M, et al. Rate and predictors of treatment prescription for hepatitis C. Gut. 2006;56:385-389.

j. Onyike CU, Bonner JO, Lyketsos CG, et al. Mania during treatment of chronic hepatitis C with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:429-435.

Long recognized to be more prevalent in forensic populations, bipolar disorder (BD) is especially overrepresented among those with repeat arrests and incarcerations. In a recent study of >79,000 inmates incarcerated in Texas in 2006 and 2007, those with BD were 3.3 times more likely to have had ≥4 previous incarcerations.k

Comorbid substance use disorder (SUD) is a significant risk factor for criminal arrest. For example, in a Los Angeles County (CA) sample of inmates with BD, 75.8% had co-occurring SUDs, compared with 18.5% in a comparison group of hospitalized BD patients.l The association of SUDs with arrest is especially high in females with BD. In the Los Angeles sample mentioned above, incarcerated bipolar women were >38 times more likely to have a SUD than a comparison group of female patients treated in the community.m

References

k. Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, et al. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:103-109.

l. Quanbeck CD, Stone DC, Scott CL, et al. Clinical and legal correlates of inmates with bipolar disorder at time of criminal arrest. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:198-203.

m. McDermott BE, Quanbeck CD, Frye MA. Comorbid substance use disorder in women with bipolar disorder is associated with criminal arrest. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(5):536-540.

1. Levin FR, Hennessey G. Bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:738-748.

2. Frye MA, Salloum IM. Bipolar disorder and comorbid alcoholism: prevalence rate and treatment considerations. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:677-685.

3. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

4. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830-842.

5. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543-552.

6. Sublette EM, Carballo JJ, Moreno C, et al. Substance use disorders and suicide attempts in bipolar subtypes. J Psychiatric Res. 2009;43:230-238.

7. McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, et al. Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:420-426.

8. Frye MA, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, et al. Gender differences in prevalence, risk, and clinical correlates of alcoholism comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:883-889.

9. Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222-2229.

10. Perron BE, Howard MO, Nienhuis JK, et al. Prevalence and burden of general medical conditions among adults with bipolar I disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1407-1415.

11. Himelhoch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:30-37.

12. Matthews AM, Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, et al. Hepatitis C testing and infection rates in bipolar patients with and without comorbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:266-270.

13. Singh JB, Zarate CA. Pharmacological treatment of psychiatric comorbidity in bipolar disorder: a review of controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:696-709.

14. Vornik LA, Brown ES. Management of comorbid bipolar disorder and substance abuse. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):24-30.

15. Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clin Psych Rev. 2000;20:191-206.

16. Berk M, Dodd S, Callaly P, et al. History of illness prior to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;103:181-186.

17. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

18. McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, et al. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:497-502.

19. Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, et al. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance abuse disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:929-937.

20. Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, et al. Medication compliance among patients with bipolar disorder and substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:172-174.

21. Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Callahan AM, et al. Overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder among substance use disorder inpatients with mood instability. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1751-1757.

22. Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, et al. Alcoholism in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness: familial illness, course of illness, and the primary-secondary distinction. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:365-372.

23. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health care settings. MMWR. 2006;55(RR14):1-17.

24. Salloum IM, Cornelius JR, Daley DC, et al. Efficacy of valproate maintenance in patients with bipolar disorder and alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:37-45.

25. Geller B, Cooper TB, Sun K, et al. Double-blind and placebo-controlled study of lithium for adolescent bipolar disorders with secondary substance dependency. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):171-178.

26. Brady KT, Sonne SC, Malcolm RJ, et al. Carbamazepine in the treatment of cocaine dependence: subtyping by affective disorder. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:276-285.

27. Brown ES, Garza M, Carmody TJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled add-on trial of quetiapine in outpatients with bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:701-705.

28. Kemp DE, Gao K, Ganocy S, et al. A 6-month, double-blind, maintenance trial of lithium monotherapy versus the combination of lithium and divalproex for rapid-cycling bipolar disorder and co-occurring substance abuse or dependence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:113-121.

29. Brown ES, Carmody TJ, Schmitz JM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of naltrexone in outpatients with bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;3:1863-1869.

30. Lamictal [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2009.

31. Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Kolodziej MR, et al. A randomized trial of integrated group therapy versus group drug counseling for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:100-107.

After testing positive for cocaine on a recent court-mandated urine drug screen, Mr. M, age 49, is referred by his parole officer for psychiatric and substance abuse treatment. Mr. M has bipolar I disorder and alcohol, cocaine, and opioid dependence. He says he has been hospitalized or incarcerated at least once each year for the past 22 years. Mr. M has seen numerous psychiatrists as an outpatient, but rarely for more than 2 to 3 months and has not taken any psychotropics for more than 5 months.

Approximately 1 week before his recent urine drug screen, Mr. M became euphoric, stopped sleeping for several days, and spent $2,000 on cocaine and “escorts.” He reports that each day he smokes 30 cigarettes and drinks 1 pint of liquor and prefers to use cocaine and opiates by IV injection. Several years ago Mr. M was diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) but received no further workup or treatment. Although he denies manic or psychotic symptoms, Mr. M is observed speaking to unseen others in the waiting room and has difficulty remaining still during his interview. His chief concern is insomnia, stating, “Doc, I just need something to help me sleep.”

The high prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in persons with bipolar disorder (BD) is well documented.1,2 Up to 60% of bipolar patients develop an SUD at some point in their lives.3-5 Alcohol use disorders are particularly common among BD patients, with a lifetime prevalence of roughly 50%.2-5 Recent epidemiologic data indicate that 38% of persons with bipolar I disorder and 19% of those with bipolar II disorder meet criteria for alcohol dependence.5 Comorbid SUDs in patients with BD are associated with:

- poor treatment compliance

- longer and more frequent mood episodes

- more mixed episodes

- more hospitalizations

- more frequent suicide attempts.1,2

The impact of co-occurring SUDs on suicidality is particularly high among those with bipolar I disorder.6

Frequently referred to as “dual diagnosis” conditions, co-occurring BD and SUDs may be more accurately envisioned as multi-morbid, rather than comorbid, illnesses. Data from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network suggest that 42% of BD patients have a lifetime history of ≥2 comorbid axis I disorders.7 Rates of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder are particularly high in BD patients with co-occurring SUDs.8,9 In addition, the presence of 1 SUD may mark the presence of other SUDs; for example, alcohol dependence is strongly associated with polysubstance abuse, especially in females with BD.8 Furthermore, medical comorbidities that impact treatment decisions also are highly prevalent in BD patients with comorbid SUDs.10 In particular, HCV rates are higher in persons with BD compared with the general population,11 and are >5 times as likely in bipolar patients with co-occurring SUDs.12

Unfortunately, limited treatment research guides clinical management of comorbid BD and SUDs.2,13,14 Clinical trials of medications for BD traditionally have excluded patients with SUDs, and persons with serious mental illness usually are ineligible for SUD treatment studies.13 Furthermore, the few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in persons with both illnesses have been constrained by relatively small sample sizes and low retention rates. In the absence of a definitive consensus for optimal treatment, this article outlines general clinical considerations and an integrated approach to assessing and managing this complex patient population.

Birds of a feather

Multiple hypotheses try to account for the high rate of SUDs in patients with BD (Table 1), but none fully explain the complex interaction observed clinically.14,15 Substance dependence and BD are chronic remitting/relapsing disorders with heterogeneous presentations and highly variable natural histories. As with SUDs, BD may go undiagnosed and untreated for years, coming to clinical attention only after substantial disease progression.16

The fluctuating illness course in BD and SUDs makes diagnosis and treatment difficult. Symptomatic periods often are interrupted by spontaneous remissions and longer—although usually temporary—periods of perceived control. Both BD and SUDs may be associated with profound mood instability, increased impulsivity, altered responsiveness to reward, and impaired executive function.17 Finally, the high degree of heritability in BD18 and many SUDs19 may make treatment engagement more difficult if either disorder is present in multiple family members because of:

- potential for greater clinical severity

- reduced psychosocial resources

- altered familial behavioral norms that may impede the patient’s recognition of illness.

Denial of illness is a critical symptom that may fluctuate with disease course in both disorders. Persons with BD or SUDs may be least likely to recognize that they are ill during periods of highest symptom severity. Accordingly, treatment adherence in patients with either disorder may be limited at baseline and decline further when the 2 illnesses co-occur.20

Involvement in the criminal justice system and medical comorbidities, particularly HCV, also complicate diagnosis and treatment of BD patients with SUDs. For more information about these topics, see Box1 and Box2.

Table 1

Why is substance abuse so prevalent among bipolar patients?

| Proposed hypothesis | Selected limitations of this hypothesis |

|---|---|

| Self-medication: substance abuse occurs as an attempt to regulate mood | High rates of substance use during euthymia; high prevalence of alcohol/depressant use during depressive phase, stimulant use during manic phase |

| Common neurobiologic or genetic risk factors | Specific evidence from linkage/association studies currently is lacking |

| Substance use occurs as a symptom of bipolar disorder | High percentage of patients with bipolar disorder do not have SUDs; there is a poor correlation of onset, course of bipolar, and SUD symptoms |

| Substance use unmasks bipolar disorder or a bipolar diathesis | Emergence of mania before SUD is common and predictive of more severe course of bipolar disorder |

| High comorbidity rates are an artifact of misdiagnosis based on overlapping symptoms and poor diagnostic boundaries | Very high prevalence of SUDs also is observed in longitudinal studies of patients initially hospitalized for mania |

| SUDs: substance use disorders | |

| Source: References 14,15 | |

Integrated clinical management

Assessment. Although not intended to be comprehensive, suggestions for routine assessment of patients with suspected SUDs and/or BD are listed in Table 2. Because clinicians may encounter dual diagnosis patients in general psychiatric clinics or specialty (addiction or mood disorder) clinics, it is useful to obtain a thorough substance use history in all patients with known or suspected BD as well as a thorough history of hypomania/mania and depression in all patients with addictive disorders. BD diagnoses by self-report or chart history in patients with SUDs should be considered cautiously because BD often is overdiagnosed in persons engaged in active substance abuse or experiencing withdrawal.21 If past or present mood symptoms and substance use have co-occurred, further focused assessment of mood symptoms before alcohol and drug use or during extended periods of abstinence are necessary to make the diagnosis of bipolar disorder with confidence. Family history of SUDs and/or BD are neither necessary nor sufficient for either diagnosis; however, collateral information from family or significant others could help make the diagnosis and may identify aids and obstacles to treatment planning and engagement.

When a patient’s clinical history strongly supports the diagnoses of BD and co-occurring SUDs, more detailed inquiry is warranted. Determining the patient’s age at onset of each disorder may have prognostic value because onset of mania before SUDs developed, especially in adolescence, may predict a more severe course of both illnesses.22 A complete alcohol use history should include routine questioning about past withdrawal. Previous withdrawal seizures in an actively drinking BD patient may tip the balance toward adding an anticonvulsant for mood stabilization. A thorough SUD history should elicit information about polysubstance abuse or dependence and include screening for injection drug use and other risk factors for HCV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), such as hypersexuality during manic or hypomanic episodes. Document the date of the last screening for HCV/ HIV in BD patients at high risk of infection. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all patients at high risk for HIV consider voluntary screening at least annually.23

Assess your patient’s historical and ongoing alcohol and other drug abuse at the initial visit, and continue to monitor substance use at all subsequent visits, especially in patients with HCV. When feasible, order urine drug screening and laboratory testing for alcohol use biomarkers such as carbohydrate-deficient transferrin and gamma-glutamyltransferase to supplement self-report data, especially in patients with poor insight or low motivation. Assess suicidal ideation and any changes in suicide risk factors at every visit.

Treatment. No biologic therapies have been FDA-approved for treating patients with co-occurring BD and SUDs. Comorbid SUDs in BD patients—as well as rapid cycling and mixed mood episodes, both of which are more common in patients with comorbid SUDs—predict poor response to lithium.17 However, the evidence base for optimal pharmacotherapy remains extremely limited. Published double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs in persons with BD and co-morbid SUDs are limited to only 1 trial each of lithium, carbamazepine, quetiapine, and naltrexone, and 2 comparisons of lithium plus divalproex vs lithium alone (Table 3).24-29

Salloum et al24 reported that bipolar I disorder patients with alcohol dependence who received divalproex plus lithium as maintenance treatment had fewer heavy drinking days and fewer drinks per heavy drinking day than those receiving lithium plus placebo. However, the addition of divalproex did not improve manic or depressive symptoms, and depression remission rates remained relatively low in both groups. A recent 6-month study comparing lithium vs lithium plus divalproex in patients with SUDs and rapid-cycling BD found no additional benefit of divalproex over lithium monotherapy in retention, mood, or substance use outcomes.28 However, modest evidence that anticonvulsants such as valproic acid and carbamazepine may help treat acute alcohol withdrawal2 could support their preferential use as mood stabilizers over lithium in actively drinking BD patients.

Research underscores the difficulty in keeping dual diagnosis patients in treatment. Salloum et al24 reported that only one-third of randomized subjects completed the 24-week study. In the Kemp study,28 79% of 149 recruited subjects failed to complete the lead-in stabilization phase. Of the 31 remaining subjects who were randomized to lithium or lithium/divalproex combination, only 8 (26% of those randomized, 5% of those recruited) completed the 6-month trial.

Substance abuse is associated with significantly decreased treatment adherence in persons with BD20 and may affect medication choice. For example, caution may be warranted in the use of lamotrigine in substance-abusing patients with poor adherence because re-titration from the starting dose is recommended if the medicine has been missed for a consecutive period exceeding 5 half-lives of the drug.30

Notable progress has been made in developing psychosocial treatments for comorbid SUDs and BD. Integrated group therapy has been designed to address the 2 disorders simultaneously by emphasizing the relationship between the disorders and highlighting similarities in cognitive and behavioral change that promote recovery in both.31 In a recent well-controlled RCT, this approach reduced alcohol and other drug use to approximately one-half the levels observed in those who received only group drug counseling.31

Research suggests that an integrated approach that encompasses psychiatric, medical, psychosocial, and legal dimensions simultaneously may be most effective. For patients such as Mr. M, this would include aggressively treating mood symptoms while employing motivational interviewing techniques to improve engagement in substance dependence treatment. If possible, involving family members, parole officials, housing agencies, and other public assistance workers in the treatment plan may increase treatment adherence and reduce loss of contact during illness exacerbations. Stabilization of substance use and psychiatric morbidity should be accompanied by timely evaluation of HCV and other medical comorbidities in order to improve long-term prognosis.

Table 2

Assessing patients you suspect have comorbid BD and SUDs

| Initial assessment |

|---|

Thorough substance use history in all patients with known or suspected bipolar disorder:

|

Thorough evaluation of any history of hypomania/mania and depression in all patients with known or suspected SUDs:

|

| Assess risk factors, screening status for hepatitis C, HIV |

| Obtain collateral information from family and significant others if feasible and appropriate |

| Detailed assessment of suicide risk |

| Follow-up assessments |

| Substance use since last visit by self-report |

| Consider UDS, CDT, GGT |

| Medication adherence |

| Detailed assessment of suicide risk |

| BD: bipolar disorder; CDT: carbohydrate-deficient transferrin; GGT: gamma-glutamyltransferase; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; SUDs: substance use disorders; UDS: urine drug screen |

Table 3

Pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and co-occurring SUDs

| Study | Diagnoses/N* | Medications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salloum et al, 200524 | BD I, alcohol dependence. N=59 [20] | Divalproex + lithium vs lithium, 24 weeks | Decreased number of heavy drinking days, fewer drinks per heavy drinking day |

| Geller et al, 199825 | BD I, BP II, MDD (adolescents); alcohol, cannabis abuse. N=25 [21] | Lithium, 6 weeks | Decreased cannabis-positive urine drug screen (lithium > placebo) |

| Brady et al, 200226 | BD I, BD II, cyclothymia; cocaine dependence. N=57 | Carbamazepine, 12 weeks | Trend toward longer time to cocaine use |

| Brown et al, 200827 | BD I, BD II; N=102 | Quetiapine, 12 weeks | Decreased HAM-D scores (quetiapine > placebo) |

| Kemp et al, 200928 | BD I, BD II, rapid cycling; alcohol, cannabis, cocaine abuse or dependence. N=31 [8] | Divalproex + lithium vs lithium, 6 months | No group differences |

| Brown et al, 200929 | BD I, BD II; alcohol dependence. N=50 [26] | Naltrexone, 12 weeks | Trend toward increased probability of no drinking days |

| * N=number of subjects randomized to double-blind treatment. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of subjects who completed all study visits (when reported) | |||

| BD: bipolar disorder; HAM-D: 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MDD: major depressive disorder; SUDs: substance use disorders | |||

Related Resources

- International Society for Bipolar Disorders. www.isbd.org.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. www.niaaa.nih.gov.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. www.nida.nih.gov.

Drug Brand Names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Divalproex/valproic acid • Depakote

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid

- Naltrexone • ReVia

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

Disclosure

Dr. Tolliver receives research grant funding from Forest Laboratories and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Neither source influenced the content or submission of this manuscript.

A recent analysis of data from >65,000 veterans found bipolar patients with comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs) were 7 times more likely to have hepatitis C virus (HCV) than patients with no serious mental illness.a Matthews and colleagues found that 29.6% of persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) and SUDs tested positive for HCV—roughly 5 times the relative risk of patients without either diagnosis.b The high prevalence of HCV in patients with comorbid BD and SUDs may be the result of injection drug use, increased risky sexual behavior while manic or intoxicated, or both.

HCV has multiple treatment implications for these patients. Alcohol abuse and dependence are the most common SUDs that co-occur with BD,c-e and patients with HCV who drink alcohol excessively have more severe hepatic fibrosis, accelerated disease progression, and higher rates of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma than HCV patients who do not drink.f Medications commonly used to treat BD or alcohol dependence may have adverse effects on the liver and require more careful monitoring in the presence of HCV infection. For example, valproic acid has been reported to improve drinking outcomes in alcohol-dependent patients with BDg but has been associated with higher rates of marked hepatic transaminase elevation in patients with HCV infection compared with those without HCV.h Marked elevation of hepatic transaminases may be observed in HCV-infected individuals treated with other medications such as lithium or antidepressants,h and valproic acid use is not an absolute contraindication in HCV patients. Nevertheless, the effects of valproic acid in HCV-infected BD patients who drink alcohol are unknown and therefore cautious and frequent monitoring of hepatic enzymes are warranted in this population.

Finally, both SUDs and BD complicate HCV treatment. In a database review of >113,000 veterans with HCV infection, Butt and colleagues found that individuals with BD accounted for 10.4% of the HCV-infected sample but only 5% of those who received HCV treatment.i Similarly, patients with alcohol abuse or dependence made up 44.3% of the HCV-infected sample but only 28.9% of those who received HCV treatment.

Because the rate of liver biopsy in untreated patients was low, the decision not to treat appeared to be based more often on other criteria. This is not surprising; pegylated interferon-alfa—the most effective treatment for chronic HCV—has been associated with multiple neuropsychiatric symptoms observed in BD, including depression, mania, psychosis, and suicidal ideation.j Emergence of severe psychiatric complications usually results in permanent discontinuation of interferon treatment. Likewise, the presence of alcohol abuse or other SUDs is a strong negative predictor of interferon treatment response and retention and generally has been considered a relative contraindication for interferon initiation.f

References

a. Himelhoch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:30-37.

b. Matthews AM, Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, et al. Hepatitis C testing and infection rates in bipolar patients with and without comorbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:266-270.

c. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

d. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830-842.

e. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543-552.

f. Bhattacharya R, Shuhart M. Hepatitis C and alcohol. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:242-252.

g. Salloum IM, Cornelius JR, Daley DC, et al. Efficacy of valproate maintenance in patients with bipolar disorder and alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:37-45.

h. Felker BL, Sloan KL, Dominitz JA, et al. The safety of valproic acid use for patients with hepatitis C infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:174-178.

i. Butt AA, Justice AC, Skanderson M, et al. Rate and predictors of treatment prescription for hepatitis C. Gut. 2006;56:385-389.

j. Onyike CU, Bonner JO, Lyketsos CG, et al. Mania during treatment of chronic hepatitis C with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:429-435.

Long recognized to be more prevalent in forensic populations, bipolar disorder (BD) is especially overrepresented among those with repeat arrests and incarcerations. In a recent study of >79,000 inmates incarcerated in Texas in 2006 and 2007, those with BD were 3.3 times more likely to have had ≥4 previous incarcerations.k

Comorbid substance use disorder (SUD) is a significant risk factor for criminal arrest. For example, in a Los Angeles County (CA) sample of inmates with BD, 75.8% had co-occurring SUDs, compared with 18.5% in a comparison group of hospitalized BD patients.l The association of SUDs with arrest is especially high in females with BD. In the Los Angeles sample mentioned above, incarcerated bipolar women were >38 times more likely to have a SUD than a comparison group of female patients treated in the community.m

References

k. Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, et al. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:103-109.

l. Quanbeck CD, Stone DC, Scott CL, et al. Clinical and legal correlates of inmates with bipolar disorder at time of criminal arrest. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:198-203.

m. McDermott BE, Quanbeck CD, Frye MA. Comorbid substance use disorder in women with bipolar disorder is associated with criminal arrest. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(5):536-540.

After testing positive for cocaine on a recent court-mandated urine drug screen, Mr. M, age 49, is referred by his parole officer for psychiatric and substance abuse treatment. Mr. M has bipolar I disorder and alcohol, cocaine, and opioid dependence. He says he has been hospitalized or incarcerated at least once each year for the past 22 years. Mr. M has seen numerous psychiatrists as an outpatient, but rarely for more than 2 to 3 months and has not taken any psychotropics for more than 5 months.

Approximately 1 week before his recent urine drug screen, Mr. M became euphoric, stopped sleeping for several days, and spent $2,000 on cocaine and “escorts.” He reports that each day he smokes 30 cigarettes and drinks 1 pint of liquor and prefers to use cocaine and opiates by IV injection. Several years ago Mr. M was diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) but received no further workup or treatment. Although he denies manic or psychotic symptoms, Mr. M is observed speaking to unseen others in the waiting room and has difficulty remaining still during his interview. His chief concern is insomnia, stating, “Doc, I just need something to help me sleep.”

The high prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in persons with bipolar disorder (BD) is well documented.1,2 Up to 60% of bipolar patients develop an SUD at some point in their lives.3-5 Alcohol use disorders are particularly common among BD patients, with a lifetime prevalence of roughly 50%.2-5 Recent epidemiologic data indicate that 38% of persons with bipolar I disorder and 19% of those with bipolar II disorder meet criteria for alcohol dependence.5 Comorbid SUDs in patients with BD are associated with:

- poor treatment compliance

- longer and more frequent mood episodes

- more mixed episodes

- more hospitalizations

- more frequent suicide attempts.1,2

The impact of co-occurring SUDs on suicidality is particularly high among those with bipolar I disorder.6

Frequently referred to as “dual diagnosis” conditions, co-occurring BD and SUDs may be more accurately envisioned as multi-morbid, rather than comorbid, illnesses. Data from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network suggest that 42% of BD patients have a lifetime history of ≥2 comorbid axis I disorders.7 Rates of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder are particularly high in BD patients with co-occurring SUDs.8,9 In addition, the presence of 1 SUD may mark the presence of other SUDs; for example, alcohol dependence is strongly associated with polysubstance abuse, especially in females with BD.8 Furthermore, medical comorbidities that impact treatment decisions also are highly prevalent in BD patients with comorbid SUDs.10 In particular, HCV rates are higher in persons with BD compared with the general population,11 and are >5 times as likely in bipolar patients with co-occurring SUDs.12

Unfortunately, limited treatment research guides clinical management of comorbid BD and SUDs.2,13,14 Clinical trials of medications for BD traditionally have excluded patients with SUDs, and persons with serious mental illness usually are ineligible for SUD treatment studies.13 Furthermore, the few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in persons with both illnesses have been constrained by relatively small sample sizes and low retention rates. In the absence of a definitive consensus for optimal treatment, this article outlines general clinical considerations and an integrated approach to assessing and managing this complex patient population.

Birds of a feather

Multiple hypotheses try to account for the high rate of SUDs in patients with BD (Table 1), but none fully explain the complex interaction observed clinically.14,15 Substance dependence and BD are chronic remitting/relapsing disorders with heterogeneous presentations and highly variable natural histories. As with SUDs, BD may go undiagnosed and untreated for years, coming to clinical attention only after substantial disease progression.16

The fluctuating illness course in BD and SUDs makes diagnosis and treatment difficult. Symptomatic periods often are interrupted by spontaneous remissions and longer—although usually temporary—periods of perceived control. Both BD and SUDs may be associated with profound mood instability, increased impulsivity, altered responsiveness to reward, and impaired executive function.17 Finally, the high degree of heritability in BD18 and many SUDs19 may make treatment engagement more difficult if either disorder is present in multiple family members because of:

- potential for greater clinical severity

- reduced psychosocial resources

- altered familial behavioral norms that may impede the patient’s recognition of illness.

Denial of illness is a critical symptom that may fluctuate with disease course in both disorders. Persons with BD or SUDs may be least likely to recognize that they are ill during periods of highest symptom severity. Accordingly, treatment adherence in patients with either disorder may be limited at baseline and decline further when the 2 illnesses co-occur.20

Involvement in the criminal justice system and medical comorbidities, particularly HCV, also complicate diagnosis and treatment of BD patients with SUDs. For more information about these topics, see Box1 and Box2.

Table 1

Why is substance abuse so prevalent among bipolar patients?

| Proposed hypothesis | Selected limitations of this hypothesis |

|---|---|

| Self-medication: substance abuse occurs as an attempt to regulate mood | High rates of substance use during euthymia; high prevalence of alcohol/depressant use during depressive phase, stimulant use during manic phase |

| Common neurobiologic or genetic risk factors | Specific evidence from linkage/association studies currently is lacking |

| Substance use occurs as a symptom of bipolar disorder | High percentage of patients with bipolar disorder do not have SUDs; there is a poor correlation of onset, course of bipolar, and SUD symptoms |

| Substance use unmasks bipolar disorder or a bipolar diathesis | Emergence of mania before SUD is common and predictive of more severe course of bipolar disorder |

| High comorbidity rates are an artifact of misdiagnosis based on overlapping symptoms and poor diagnostic boundaries | Very high prevalence of SUDs also is observed in longitudinal studies of patients initially hospitalized for mania |

| SUDs: substance use disorders | |

| Source: References 14,15 | |

Integrated clinical management

Assessment. Although not intended to be comprehensive, suggestions for routine assessment of patients with suspected SUDs and/or BD are listed in Table 2. Because clinicians may encounter dual diagnosis patients in general psychiatric clinics or specialty (addiction or mood disorder) clinics, it is useful to obtain a thorough substance use history in all patients with known or suspected BD as well as a thorough history of hypomania/mania and depression in all patients with addictive disorders. BD diagnoses by self-report or chart history in patients with SUDs should be considered cautiously because BD often is overdiagnosed in persons engaged in active substance abuse or experiencing withdrawal.21 If past or present mood symptoms and substance use have co-occurred, further focused assessment of mood symptoms before alcohol and drug use or during extended periods of abstinence are necessary to make the diagnosis of bipolar disorder with confidence. Family history of SUDs and/or BD are neither necessary nor sufficient for either diagnosis; however, collateral information from family or significant others could help make the diagnosis and may identify aids and obstacles to treatment planning and engagement.

When a patient’s clinical history strongly supports the diagnoses of BD and co-occurring SUDs, more detailed inquiry is warranted. Determining the patient’s age at onset of each disorder may have prognostic value because onset of mania before SUDs developed, especially in adolescence, may predict a more severe course of both illnesses.22 A complete alcohol use history should include routine questioning about past withdrawal. Previous withdrawal seizures in an actively drinking BD patient may tip the balance toward adding an anticonvulsant for mood stabilization. A thorough SUD history should elicit information about polysubstance abuse or dependence and include screening for injection drug use and other risk factors for HCV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), such as hypersexuality during manic or hypomanic episodes. Document the date of the last screening for HCV/ HIV in BD patients at high risk of infection. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all patients at high risk for HIV consider voluntary screening at least annually.23

Assess your patient’s historical and ongoing alcohol and other drug abuse at the initial visit, and continue to monitor substance use at all subsequent visits, especially in patients with HCV. When feasible, order urine drug screening and laboratory testing for alcohol use biomarkers such as carbohydrate-deficient transferrin and gamma-glutamyltransferase to supplement self-report data, especially in patients with poor insight or low motivation. Assess suicidal ideation and any changes in suicide risk factors at every visit.

Treatment. No biologic therapies have been FDA-approved for treating patients with co-occurring BD and SUDs. Comorbid SUDs in BD patients—as well as rapid cycling and mixed mood episodes, both of which are more common in patients with comorbid SUDs—predict poor response to lithium.17 However, the evidence base for optimal pharmacotherapy remains extremely limited. Published double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs in persons with BD and co-morbid SUDs are limited to only 1 trial each of lithium, carbamazepine, quetiapine, and naltrexone, and 2 comparisons of lithium plus divalproex vs lithium alone (Table 3).24-29

Salloum et al24 reported that bipolar I disorder patients with alcohol dependence who received divalproex plus lithium as maintenance treatment had fewer heavy drinking days and fewer drinks per heavy drinking day than those receiving lithium plus placebo. However, the addition of divalproex did not improve manic or depressive symptoms, and depression remission rates remained relatively low in both groups. A recent 6-month study comparing lithium vs lithium plus divalproex in patients with SUDs and rapid-cycling BD found no additional benefit of divalproex over lithium monotherapy in retention, mood, or substance use outcomes.28 However, modest evidence that anticonvulsants such as valproic acid and carbamazepine may help treat acute alcohol withdrawal2 could support their preferential use as mood stabilizers over lithium in actively drinking BD patients.

Research underscores the difficulty in keeping dual diagnosis patients in treatment. Salloum et al24 reported that only one-third of randomized subjects completed the 24-week study. In the Kemp study,28 79% of 149 recruited subjects failed to complete the lead-in stabilization phase. Of the 31 remaining subjects who were randomized to lithium or lithium/divalproex combination, only 8 (26% of those randomized, 5% of those recruited) completed the 6-month trial.

Substance abuse is associated with significantly decreased treatment adherence in persons with BD20 and may affect medication choice. For example, caution may be warranted in the use of lamotrigine in substance-abusing patients with poor adherence because re-titration from the starting dose is recommended if the medicine has been missed for a consecutive period exceeding 5 half-lives of the drug.30

Notable progress has been made in developing psychosocial treatments for comorbid SUDs and BD. Integrated group therapy has been designed to address the 2 disorders simultaneously by emphasizing the relationship between the disorders and highlighting similarities in cognitive and behavioral change that promote recovery in both.31 In a recent well-controlled RCT, this approach reduced alcohol and other drug use to approximately one-half the levels observed in those who received only group drug counseling.31

Research suggests that an integrated approach that encompasses psychiatric, medical, psychosocial, and legal dimensions simultaneously may be most effective. For patients such as Mr. M, this would include aggressively treating mood symptoms while employing motivational interviewing techniques to improve engagement in substance dependence treatment. If possible, involving family members, parole officials, housing agencies, and other public assistance workers in the treatment plan may increase treatment adherence and reduce loss of contact during illness exacerbations. Stabilization of substance use and psychiatric morbidity should be accompanied by timely evaluation of HCV and other medical comorbidities in order to improve long-term prognosis.

Table 2

Assessing patients you suspect have comorbid BD and SUDs

| Initial assessment |

|---|

Thorough substance use history in all patients with known or suspected bipolar disorder:

|

Thorough evaluation of any history of hypomania/mania and depression in all patients with known or suspected SUDs:

|

| Assess risk factors, screening status for hepatitis C, HIV |

| Obtain collateral information from family and significant others if feasible and appropriate |

| Detailed assessment of suicide risk |

| Follow-up assessments |

| Substance use since last visit by self-report |

| Consider UDS, CDT, GGT |

| Medication adherence |

| Detailed assessment of suicide risk |

| BD: bipolar disorder; CDT: carbohydrate-deficient transferrin; GGT: gamma-glutamyltransferase; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; SUDs: substance use disorders; UDS: urine drug screen |

Table 3

Pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and co-occurring SUDs

| Study | Diagnoses/N* | Medications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salloum et al, 200524 | BD I, alcohol dependence. N=59 [20] | Divalproex + lithium vs lithium, 24 weeks | Decreased number of heavy drinking days, fewer drinks per heavy drinking day |

| Geller et al, 199825 | BD I, BP II, MDD (adolescents); alcohol, cannabis abuse. N=25 [21] | Lithium, 6 weeks | Decreased cannabis-positive urine drug screen (lithium > placebo) |

| Brady et al, 200226 | BD I, BD II, cyclothymia; cocaine dependence. N=57 | Carbamazepine, 12 weeks | Trend toward longer time to cocaine use |

| Brown et al, 200827 | BD I, BD II; N=102 | Quetiapine, 12 weeks | Decreased HAM-D scores (quetiapine > placebo) |

| Kemp et al, 200928 | BD I, BD II, rapid cycling; alcohol, cannabis, cocaine abuse or dependence. N=31 [8] | Divalproex + lithium vs lithium, 6 months | No group differences |

| Brown et al, 200929 | BD I, BD II; alcohol dependence. N=50 [26] | Naltrexone, 12 weeks | Trend toward increased probability of no drinking days |

| * N=number of subjects randomized to double-blind treatment. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of subjects who completed all study visits (when reported) | |||

| BD: bipolar disorder; HAM-D: 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MDD: major depressive disorder; SUDs: substance use disorders | |||

Related Resources

- International Society for Bipolar Disorders. www.isbd.org.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. www.niaaa.nih.gov.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. www.nida.nih.gov.

Drug Brand Names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Divalproex/valproic acid • Depakote

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Lithobid

- Naltrexone • ReVia

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

Disclosure

Dr. Tolliver receives research grant funding from Forest Laboratories and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Neither source influenced the content or submission of this manuscript.

A recent analysis of data from >65,000 veterans found bipolar patients with comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs) were 7 times more likely to have hepatitis C virus (HCV) than patients with no serious mental illness.a Matthews and colleagues found that 29.6% of persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) and SUDs tested positive for HCV—roughly 5 times the relative risk of patients without either diagnosis.b The high prevalence of HCV in patients with comorbid BD and SUDs may be the result of injection drug use, increased risky sexual behavior while manic or intoxicated, or both.

HCV has multiple treatment implications for these patients. Alcohol abuse and dependence are the most common SUDs that co-occur with BD,c-e and patients with HCV who drink alcohol excessively have more severe hepatic fibrosis, accelerated disease progression, and higher rates of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma than HCV patients who do not drink.f Medications commonly used to treat BD or alcohol dependence may have adverse effects on the liver and require more careful monitoring in the presence of HCV infection. For example, valproic acid has been reported to improve drinking outcomes in alcohol-dependent patients with BDg but has been associated with higher rates of marked hepatic transaminase elevation in patients with HCV infection compared with those without HCV.h Marked elevation of hepatic transaminases may be observed in HCV-infected individuals treated with other medications such as lithium or antidepressants,h and valproic acid use is not an absolute contraindication in HCV patients. Nevertheless, the effects of valproic acid in HCV-infected BD patients who drink alcohol are unknown and therefore cautious and frequent monitoring of hepatic enzymes are warranted in this population.

Finally, both SUDs and BD complicate HCV treatment. In a database review of >113,000 veterans with HCV infection, Butt and colleagues found that individuals with BD accounted for 10.4% of the HCV-infected sample but only 5% of those who received HCV treatment.i Similarly, patients with alcohol abuse or dependence made up 44.3% of the HCV-infected sample but only 28.9% of those who received HCV treatment.

Because the rate of liver biopsy in untreated patients was low, the decision not to treat appeared to be based more often on other criteria. This is not surprising; pegylated interferon-alfa—the most effective treatment for chronic HCV—has been associated with multiple neuropsychiatric symptoms observed in BD, including depression, mania, psychosis, and suicidal ideation.j Emergence of severe psychiatric complications usually results in permanent discontinuation of interferon treatment. Likewise, the presence of alcohol abuse or other SUDs is a strong negative predictor of interferon treatment response and retention and generally has been considered a relative contraindication for interferon initiation.f

References

a. Himelhoch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:30-37.

b. Matthews AM, Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, et al. Hepatitis C testing and infection rates in bipolar patients with and without comorbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:266-270.

c. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

d. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830-842.

e. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543-552.

f. Bhattacharya R, Shuhart M. Hepatitis C and alcohol. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:242-252.

g. Salloum IM, Cornelius JR, Daley DC, et al. Efficacy of valproate maintenance in patients with bipolar disorder and alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:37-45.

h. Felker BL, Sloan KL, Dominitz JA, et al. The safety of valproic acid use for patients with hepatitis C infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:174-178.

i. Butt AA, Justice AC, Skanderson M, et al. Rate and predictors of treatment prescription for hepatitis C. Gut. 2006;56:385-389.

j. Onyike CU, Bonner JO, Lyketsos CG, et al. Mania during treatment of chronic hepatitis C with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:429-435.

Long recognized to be more prevalent in forensic populations, bipolar disorder (BD) is especially overrepresented among those with repeat arrests and incarcerations. In a recent study of >79,000 inmates incarcerated in Texas in 2006 and 2007, those with BD were 3.3 times more likely to have had ≥4 previous incarcerations.k

Comorbid substance use disorder (SUD) is a significant risk factor for criminal arrest. For example, in a Los Angeles County (CA) sample of inmates with BD, 75.8% had co-occurring SUDs, compared with 18.5% in a comparison group of hospitalized BD patients.l The association of SUDs with arrest is especially high in females with BD. In the Los Angeles sample mentioned above, incarcerated bipolar women were >38 times more likely to have a SUD than a comparison group of female patients treated in the community.m

References

k. Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, et al. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:103-109.

l. Quanbeck CD, Stone DC, Scott CL, et al. Clinical and legal correlates of inmates with bipolar disorder at time of criminal arrest. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:198-203.

m. McDermott BE, Quanbeck CD, Frye MA. Comorbid substance use disorder in women with bipolar disorder is associated with criminal arrest. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(5):536-540.

1. Levin FR, Hennessey G. Bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:738-748.

2. Frye MA, Salloum IM. Bipolar disorder and comorbid alcoholism: prevalence rate and treatment considerations. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:677-685.

3. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807-816.

4. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830-842.

5. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543-552.

6. Sublette EM, Carballo JJ, Moreno C, et al. Substance use disorders and suicide attempts in bipolar subtypes. J Psychiatric Res. 2009;43:230-238.

7. McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, et al. Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:420-426.

8. Frye MA, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, et al. Gender differences in prevalence, risk, and clinical correlates of alcoholism comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:883-889.

9. Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222-2229.

10. Perron BE, Howard MO, Nienhuis JK, et al. Prevalence and burden of general medical conditions among adults with bipolar I disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1407-1415.

11. Himelhoch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:30-37.

12. Matthews AM, Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, et al. Hepatitis C testing and infection rates in bipolar patients with and without comorbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:266-270.

13. Singh JB, Zarate CA. Pharmacological treatment of psychiatric comorbidity in bipolar disorder: a review of controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:696-709.

14. Vornik LA, Brown ES. Management of comorbid bipolar disorder and substance abuse. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):24-30.

15. Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clin Psych Rev. 2000;20:191-206.

16. Berk M, Dodd S, Callaly P, et al. History of illness prior to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;103:181-186.

17. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

18. McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, et al. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:497-502.

19. Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, et al. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance abuse disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:929-937.

20. Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, et al. Medication compliance among patients with bipolar disorder and substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:172-174.

21. Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Callahan AM, et al. Overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder among substance use disorder inpatients with mood instability. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1751-1757.

22. Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, et al. Alcoholism in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness: familial illness, course of illness, and the primary-secondary distinction. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:365-372.

23. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health care settings. MMWR. 2006;55(RR14):1-17.

24. Salloum IM, Cornelius JR, Daley DC, et al. Efficacy of valproate maintenance in patients with bipolar disorder and alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:37-45.

25. Geller B, Cooper TB, Sun K, et al. Double-blind and placebo-controlled study of lithium for adolescent bipolar disorders with secondary substance dependency. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):171-178.

26. Brady KT, Sonne SC, Malcolm RJ, et al. Carbamazepine in the treatment of cocaine dependence: subtyping by affective disorder. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:276-285.

27. Brown ES, Garza M, Carmody TJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled add-on trial of quetiapine in outpatients with bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:701-705.

28. Kemp DE, Gao K, Ganocy S, et al. A 6-month, double-blind, maintenance trial of lithium monotherapy versus the combination of lithium and divalproex for rapid-cycling bipolar disorder and co-occurring substance abuse or dependence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:113-121.

29. Brown ES, Carmody TJ, Schmitz JM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of naltrexone in outpatients with bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;3:1863-1869.

30. Lamictal [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2009.

31. Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Kolodziej MR, et al. A randomized trial of integrated group therapy versus group drug counseling for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:100-107.