User login

Help your bipolar disorder patients remain employed

Mrs. S, age 34, worked as an office manager with responsibilities for more than 40 employees for 5 years. Starting in her mid 20s she had repeated periods of depression, binge drinking, and risk-taking that were treated ineffectively with antidepressants. Ultimately, she was fired from her job.

Eventually Mrs. S was diagnosed as bipolar and over time responded well to a mood-stabilizing regimen. She now desires to return to work, both for financial reasons and for the sense of accomplishment that comes from working. Initially, personnel managers review her résumé and tell her she would be bored by the routine nature of entry-level positions, or they offer her jobs with major responsibilities. She accepts a high-level position but soon leaves, feeling overwhelmed by the stress.

Bipolar disorder’s long-term course presents a therapeutic challenge when patients desire to remain employed, seek temporary or permanent disability status, or—most commonly—attempt to return to employment after a period of inability to work. As the experience of Mrs. S illustrates, previous capabilities that appear higher than the person’s present or recent work experience are a key issue to address in interpersonal therapy.

Evidence-based research is informative, but ultimately you must apply judgment and flexibility in setting and revising goals with the bipolar individual. Attention to the disorder’s core characteristics can help you equip patients for work that contributes to their pursuit of health.

Obstacles to employment

Role function. Bipolar disorder impairs family and social function in approximately one-half of persons with this diagnosis, a higher impairment rate than in persons with major depression.1

Cognitive function. Bipolar disorder patients have subtle sustained impairments in cognitive function, particularly working memory.2,3 These deficits—although generally much less severe than in persons with schizophrenia—contribute to workplace and educational difficulties.

Unstable mood. Some symptoms associated with elevated mood contribute to functional impairment. These are not limited to mania or hypomania but also can be prominent in mixed states and depression.

A study from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) found that two-thirds of 1,380 depressed bipolar I and II patients had ?1 concomitant symptoms principally associated with manic states. The most prominent were distractibility, pressured speech and thoughts, risky behavior, and agitation.4 Each of these—or, more often, all of these—can interfere with work responsibilities.

Circadian rhythm pattern. Sleep disturbances in bipolar disorder differ from those associated with other medical conditions. Bipolar patients’ tendency to increase their activity and interests in the evening may keep them awake into the early morning hours. Insufficient sleep and impaired daytime cognition and alertness related to idio syncratic circadian rhythms can interfere with job requirements.5 The structure of employment can help many bipolar patients maintain effective sleep patterns as well as waking activities (Box 1).

Some individuals recognize their disturbed activity pattern, but many view it simply as the way they approach a day. For the latter group, a sustained treatment effort is needed to help them recognize the adverse consequences of the pattern and develop a more effective daily routine.

Adverse treatment effects. Although important, this core medical issue is not central to the interpersonal focus of this article. The simple tolerability objective in prescribing medications—and less frequently therapies such as electroconvulsive treatment—is to avoid dosages that impair concentration, alertness, or motor speed and accuracy. Similarly, avoid medications that can cause physical changes noticeable to others—such as tremor, sleepiness, or significant weight gain—or adjust dosages to eliminate these side effects.

Work, defined as what we do to make a living, is useful for most individuals. For persons with bipolar disorder, work has additional benefits. Having a job aids in structuring their daily activities, which tend to be skewed by circadian rhythm-linked problems of inadequate sleep or sleep that starts too late and extends into the day. The routine expectations of a work schedule also can counteract the distractibility and unproductive multitasking common in some bipolar disorder patients.

These benefits are not guaranteed and vary considerably across occupational settings, but patients and family members readily understand this aspect of work. Its benefits can serve as an important impetus for patients to persist in efforts to attain employment, even in the face of obstacles.

Bipolar symptom domains

Anxiety is recognized as a separate and major domain in bipolar psychopathology,6 contributing strongly to poor outcomes. Although anxiety is somewhat more predominant in depression and mixed states, it is common in manic and recovered bipolar states as well.

Social anxiety and panic states appear to be most specifically associated with bipolar disorder.7 Because these types of anxiety entail excessive fearful responses, psychotherapeutic techniques including extinction approaches can be helpful.

Depression in bipolar disorder tends to manifest as slowed motor and cognitive function, which is likely to be evident in work situations. Additionally, loss of social interests—one of the most common and severe aspects of depression in bipolar disorders—is likely to be evident to coworkers and to negatively impact work effectiveness.

Irritability occurs most frequently in mixed bipolar states but also is characteristic of—though generally less intense in—depressed and manic clinical states. Even when strictly internal and subjective, irritability can reduce an individual’s confidence and work effectiveness. Expressed irritability, from minor annoyances to explosive outbursts, can have serious employment consequences, including termination.

Manic symptoms. The impulsivity that is common in bipolar mania can interfere with work. Acting without considering consequences, taking undue risks, or reaching conclusions on inadequate information can cause problems, including physical harm to self or coworkers. Excessive talking—usually associated with internally recognized racing thoughts—can be a nuisance when mild or problematic if it interferes with customer or coworker interactions.

Hyperactivity and increased energy may be perceived as behaviors that facilitate productivity at work (Box 2).8-10 The adaptive characteristics of many hypomanic states are infrequent or absent in depressive, manic, and mixed manic clinical states, however.

Psychosis is principally associated with manic episodes, but it can be a component of any symptomatic clinical state. Delusional ideas or persecutory thoughts are rarely compatible with a work environment, in part because of potential risks to others.

For some purposes, bipolar disease confers social and employment advantages. Common, frequently adaptive behavioral characteristics of hypomania include:

- perseverance

- high energy

- heightened perceptual sensitivity

- exuberance and playfulness

- optimism.

Increased energy and mild degrees of hyperactivity—as well as thinking along creative, multisystem lines—can benefit work productivity, customer interactions, and work group relations. Heightened confidence and social interests can be valuable in some sales and marketing activities.

Although these attitudes and behaviors can have constructive effects, patients need to understand their limits and destructive potential. This is not a straightforward issue, as patients may not have self-awareness of some adverse consequences of characteristics such as irritability, risk taking, or inappropriate sexual advances. A phenomenon little described in clinical literature but relatively common in biographical accounts of persons with bipolar disorder is that friends or coworkers may encourage, rationalize, and take advantage of an individual’s hypomanic energy, thwarting effective interventions.

Componential treatment

Bipolar disorder’s multiple symptom domains suggest a componential approach to treatment. It may be useful to convey this concept metaphorically to the patient. When working on a jigsaw puzzle, a section that has been put together can be largely left intact and attention turned to other sections of the puzzle. Similarly, once a particular bipolar component is well managed—whether via medication, lifestyle, attitudes, or combinations of these—that symptom is likely to remain stable, barring a new insult/stressor (such as a medical condition requiring drugs that interfere with the bipolar regimen).

If mood stabilizers control risky behavior, impulsivity, and affective lability, the regimen generally will remain effective. If residual or new problems develop in another area (such as anxiety, sleep cycle, or irritability), choose drug regimens and psychoeducation approaches that are compatible with the mood-stabilizing plan. This attitude toward treatment:

- is reassuring to most patients, who come to see a new or recurring problem in one domain as not inherently a harbinger of complete relapse

- can reduce patient- or clinician-initiated deletions and additions of medications in a regimen that has been established as effective.

Autobiographical accounts of persons with bipolar disorders can be useful in educating patients about the considerations presented here. Actress Patty Duke made these observations in describing the gradual development of an effective treatment for her severe bipolar disorder:

I work at not flying off the handle…and I’m much better at it. My general medical bills dropped by $50,000 a year since my bipolar diagnosis and treatment. Until then, I was always in the hospital for some phantom illness. I was there with real symptoms born of depression. I haven’t been in the hospital since I was diagnosed.

My recovery from manic-depression has been an evolution, not a sudden miracle. For someone who spent 50% of her life screaming and yelling about something, I am now down to, say, 5%.11

Psychosocial factors to consider

Stigma in the workplace. Although most coworkers are tolerant of and fair-minded about the functional difficulties common in symptomatic bipolar disorder, some will have biased, inaccurate views about psychiatric conditions. Advise bipolar individuals to make case-by-case decisions about whether to provide personal information to other employees and, if so, how much.

As with most medical conditions, the default choice will be to not discuss personal information in the workplace. Some coworkers, however, might appreciate learning of the bipolar condition (for example, a supervisor who seems empathic to an employee’s seeming stressed state).

Realistic expectations. Most clinicians recognize that relief from a syndromal bipolar state is achieved more quickly than a sustained recovered status in which symptoms are minimal. Attaining functional capacity in a normal range also lags, both in time and in the proportion of persons who ever achieve sustained good function.12 Patients, their families, and often employers may have unrealistic expectations about early resumption of work after a depressive or manic episode resolves.

Ethnic considerations. Some literature suggests ethnic differences in the initial presentation of bipolar disorder, with more severe manifestations in some populations particularly if psychosis is a component symptom.13 Additionally, some cultural views about stigma from illness can add to patients’ or family members’ reluctance to re-enter the workplace.

Socioeconomic status. Sometimes bipolar illness puts out of reach the occupational activities that an individual has previously undertaken or that are characteristic of the family’s experience and expectations. Resistance to a change in self-concept can add to the difficulty in successfully moving a patient to consider employment that is more routinized and less intellectual or decisional in nature (Box 3).14

Divergence in education vs work status. Persons with bipolar disorders often have substantial divergence between high educational attainment and lower work performance. When this is the case, all or most of the factors reviewed in this article probably have contributed. Mrs. S’s experience illustrates this aspect of our care for persons with bipolar disorders.

An employment barrier for some bipolar patients is that a brief, often long-past period of high intellectual or vocational performance serves as the benchmark for their capabilities. Patients with this characteristic resist revising their self-concept. Some treat the loss of this idealized image as an unfair consequence of their illness or society’s reaction to bipolar disorder. Their stubbornness tends to prevent realistic engagement socially or vocationally at levels that are presently feasible for them.

Resistance to change associated with this characteristic often is difficult to manage effectively with short, relatively infrequent medication-focused visits. Specific psychosocial interventions may be more effective.14

CASE CONTINUED: Finding a new balance

After leaving the stressful high-level job, Mrs. S next resolved to limit her search to half-time positions and took a job with limited responsibilities in a bookstore. Her work productivity was outstanding, but she became easily flustered when asked to assume additional responsibilities. Some of these required quick learning of new skills in inventory re-supply or interacting with dissatisfied customers.

As she became more confident and less fearful of being fired, Mrs. S talked with 2 supervisors about her illness management. This halted their well-intentioned efforts to promote her, based on their perception of her as talented and engaging.

Attention to these workplace issues took up approximately half of the time in her regular psychiatric appointments for more than 1 year. Through this process, Mrs. S developed increasingly effective insight into the complex mix of her accomplishments and resilience on one hand and her fluctuating social and vocational impairment on the other. She also recognized that subsyndromal symptoms continued at times, despite her overall good functional state. These insights and her greater self-confidence helped Mrs. S resolve and manage the divergences in her own and others’ perceptions of her capabilities and potential.

Related Resource

- Coping with depression or bipolar disorder at your job (patient information). Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. www.dbsalliance.org/site/PageServer?pagename=Employment_Information.

Disclosure

Dr. Bowden reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, et al. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(suppl 4):AS264-AS279.

2. Glahn D, Bearden CE, Barguil M, et al. The neurocognitive signature of psychotic bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:910-916.

3. Goodwin G, Martinez-Aran A, Glahn DC, et al. Cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: neurodevelopment or neurodegeneration? An ECNP expert meeting report. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2008;18:787-793.

4. Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Bowden CL, et al. Manic symptoms during depressive episodes in 1,380 patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):173-181.

5. Mansour HA, Wood J, Chowdari KV, et al. Circadian phase variation in bipolar I disorder. Chronobiol Int. 2005;22(3):571-584.

6. Feske U, Frank E, Mallinger AG, et al. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;57:956-962.

7. Mantere O, Melartin TK, Suominen K, et al. Difference in axis I and II comorbidities between bipolar I and II disorder and major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:584-593.

8. Bowden CL. Bipolar disorder and creativity. In: Shaw MP, Runco MA, eds. Creativity and affect. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corp; 1994:73-86.

9. Andreasen N, Powers S. Overinclusive thinking in mania and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;125:452-456.

10. Solovay MR, Shenton ME, Holzman PS. Comparative studies of thought disorders. I. Mania and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:13-20.

11. Duke P, Hochman G. A brilliant madness: living with manic-depressive illness. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1997.

12. Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, et al. The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:720-727.

13. Kennedy N, Boydell J, van Os J, et al. Ethnic differences in first clinical presentation of bipolar disorder: results from an epidemiological study. J Affect Dis. 2004;83:161-168.

14. Mikowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ. Bipolar disorder: a family-focused approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006.

Mrs. S, age 34, worked as an office manager with responsibilities for more than 40 employees for 5 years. Starting in her mid 20s she had repeated periods of depression, binge drinking, and risk-taking that were treated ineffectively with antidepressants. Ultimately, she was fired from her job.

Eventually Mrs. S was diagnosed as bipolar and over time responded well to a mood-stabilizing regimen. She now desires to return to work, both for financial reasons and for the sense of accomplishment that comes from working. Initially, personnel managers review her résumé and tell her she would be bored by the routine nature of entry-level positions, or they offer her jobs with major responsibilities. She accepts a high-level position but soon leaves, feeling overwhelmed by the stress.

Bipolar disorder’s long-term course presents a therapeutic challenge when patients desire to remain employed, seek temporary or permanent disability status, or—most commonly—attempt to return to employment after a period of inability to work. As the experience of Mrs. S illustrates, previous capabilities that appear higher than the person’s present or recent work experience are a key issue to address in interpersonal therapy.

Evidence-based research is informative, but ultimately you must apply judgment and flexibility in setting and revising goals with the bipolar individual. Attention to the disorder’s core characteristics can help you equip patients for work that contributes to their pursuit of health.

Obstacles to employment

Role function. Bipolar disorder impairs family and social function in approximately one-half of persons with this diagnosis, a higher impairment rate than in persons with major depression.1

Cognitive function. Bipolar disorder patients have subtle sustained impairments in cognitive function, particularly working memory.2,3 These deficits—although generally much less severe than in persons with schizophrenia—contribute to workplace and educational difficulties.

Unstable mood. Some symptoms associated with elevated mood contribute to functional impairment. These are not limited to mania or hypomania but also can be prominent in mixed states and depression.

A study from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) found that two-thirds of 1,380 depressed bipolar I and II patients had ?1 concomitant symptoms principally associated with manic states. The most prominent were distractibility, pressured speech and thoughts, risky behavior, and agitation.4 Each of these—or, more often, all of these—can interfere with work responsibilities.

Circadian rhythm pattern. Sleep disturbances in bipolar disorder differ from those associated with other medical conditions. Bipolar patients’ tendency to increase their activity and interests in the evening may keep them awake into the early morning hours. Insufficient sleep and impaired daytime cognition and alertness related to idio syncratic circadian rhythms can interfere with job requirements.5 The structure of employment can help many bipolar patients maintain effective sleep patterns as well as waking activities (Box 1).

Some individuals recognize their disturbed activity pattern, but many view it simply as the way they approach a day. For the latter group, a sustained treatment effort is needed to help them recognize the adverse consequences of the pattern and develop a more effective daily routine.

Adverse treatment effects. Although important, this core medical issue is not central to the interpersonal focus of this article. The simple tolerability objective in prescribing medications—and less frequently therapies such as electroconvulsive treatment—is to avoid dosages that impair concentration, alertness, or motor speed and accuracy. Similarly, avoid medications that can cause physical changes noticeable to others—such as tremor, sleepiness, or significant weight gain—or adjust dosages to eliminate these side effects.

Work, defined as what we do to make a living, is useful for most individuals. For persons with bipolar disorder, work has additional benefits. Having a job aids in structuring their daily activities, which tend to be skewed by circadian rhythm-linked problems of inadequate sleep or sleep that starts too late and extends into the day. The routine expectations of a work schedule also can counteract the distractibility and unproductive multitasking common in some bipolar disorder patients.

These benefits are not guaranteed and vary considerably across occupational settings, but patients and family members readily understand this aspect of work. Its benefits can serve as an important impetus for patients to persist in efforts to attain employment, even in the face of obstacles.

Bipolar symptom domains

Anxiety is recognized as a separate and major domain in bipolar psychopathology,6 contributing strongly to poor outcomes. Although anxiety is somewhat more predominant in depression and mixed states, it is common in manic and recovered bipolar states as well.

Social anxiety and panic states appear to be most specifically associated with bipolar disorder.7 Because these types of anxiety entail excessive fearful responses, psychotherapeutic techniques including extinction approaches can be helpful.

Depression in bipolar disorder tends to manifest as slowed motor and cognitive function, which is likely to be evident in work situations. Additionally, loss of social interests—one of the most common and severe aspects of depression in bipolar disorders—is likely to be evident to coworkers and to negatively impact work effectiveness.

Irritability occurs most frequently in mixed bipolar states but also is characteristic of—though generally less intense in—depressed and manic clinical states. Even when strictly internal and subjective, irritability can reduce an individual’s confidence and work effectiveness. Expressed irritability, from minor annoyances to explosive outbursts, can have serious employment consequences, including termination.

Manic symptoms. The impulsivity that is common in bipolar mania can interfere with work. Acting without considering consequences, taking undue risks, or reaching conclusions on inadequate information can cause problems, including physical harm to self or coworkers. Excessive talking—usually associated with internally recognized racing thoughts—can be a nuisance when mild or problematic if it interferes with customer or coworker interactions.

Hyperactivity and increased energy may be perceived as behaviors that facilitate productivity at work (Box 2).8-10 The adaptive characteristics of many hypomanic states are infrequent or absent in depressive, manic, and mixed manic clinical states, however.

Psychosis is principally associated with manic episodes, but it can be a component of any symptomatic clinical state. Delusional ideas or persecutory thoughts are rarely compatible with a work environment, in part because of potential risks to others.

For some purposes, bipolar disease confers social and employment advantages. Common, frequently adaptive behavioral characteristics of hypomania include:

- perseverance

- high energy

- heightened perceptual sensitivity

- exuberance and playfulness

- optimism.

Increased energy and mild degrees of hyperactivity—as well as thinking along creative, multisystem lines—can benefit work productivity, customer interactions, and work group relations. Heightened confidence and social interests can be valuable in some sales and marketing activities.

Although these attitudes and behaviors can have constructive effects, patients need to understand their limits and destructive potential. This is not a straightforward issue, as patients may not have self-awareness of some adverse consequences of characteristics such as irritability, risk taking, or inappropriate sexual advances. A phenomenon little described in clinical literature but relatively common in biographical accounts of persons with bipolar disorder is that friends or coworkers may encourage, rationalize, and take advantage of an individual’s hypomanic energy, thwarting effective interventions.

Componential treatment

Bipolar disorder’s multiple symptom domains suggest a componential approach to treatment. It may be useful to convey this concept metaphorically to the patient. When working on a jigsaw puzzle, a section that has been put together can be largely left intact and attention turned to other sections of the puzzle. Similarly, once a particular bipolar component is well managed—whether via medication, lifestyle, attitudes, or combinations of these—that symptom is likely to remain stable, barring a new insult/stressor (such as a medical condition requiring drugs that interfere with the bipolar regimen).

If mood stabilizers control risky behavior, impulsivity, and affective lability, the regimen generally will remain effective. If residual or new problems develop in another area (such as anxiety, sleep cycle, or irritability), choose drug regimens and psychoeducation approaches that are compatible with the mood-stabilizing plan. This attitude toward treatment:

- is reassuring to most patients, who come to see a new or recurring problem in one domain as not inherently a harbinger of complete relapse

- can reduce patient- or clinician-initiated deletions and additions of medications in a regimen that has been established as effective.

Autobiographical accounts of persons with bipolar disorders can be useful in educating patients about the considerations presented here. Actress Patty Duke made these observations in describing the gradual development of an effective treatment for her severe bipolar disorder:

I work at not flying off the handle…and I’m much better at it. My general medical bills dropped by $50,000 a year since my bipolar diagnosis and treatment. Until then, I was always in the hospital for some phantom illness. I was there with real symptoms born of depression. I haven’t been in the hospital since I was diagnosed.

My recovery from manic-depression has been an evolution, not a sudden miracle. For someone who spent 50% of her life screaming and yelling about something, I am now down to, say, 5%.11

Psychosocial factors to consider

Stigma in the workplace. Although most coworkers are tolerant of and fair-minded about the functional difficulties common in symptomatic bipolar disorder, some will have biased, inaccurate views about psychiatric conditions. Advise bipolar individuals to make case-by-case decisions about whether to provide personal information to other employees and, if so, how much.

As with most medical conditions, the default choice will be to not discuss personal information in the workplace. Some coworkers, however, might appreciate learning of the bipolar condition (for example, a supervisor who seems empathic to an employee’s seeming stressed state).

Realistic expectations. Most clinicians recognize that relief from a syndromal bipolar state is achieved more quickly than a sustained recovered status in which symptoms are minimal. Attaining functional capacity in a normal range also lags, both in time and in the proportion of persons who ever achieve sustained good function.12 Patients, their families, and often employers may have unrealistic expectations about early resumption of work after a depressive or manic episode resolves.

Ethnic considerations. Some literature suggests ethnic differences in the initial presentation of bipolar disorder, with more severe manifestations in some populations particularly if psychosis is a component symptom.13 Additionally, some cultural views about stigma from illness can add to patients’ or family members’ reluctance to re-enter the workplace.

Socioeconomic status. Sometimes bipolar illness puts out of reach the occupational activities that an individual has previously undertaken or that are characteristic of the family’s experience and expectations. Resistance to a change in self-concept can add to the difficulty in successfully moving a patient to consider employment that is more routinized and less intellectual or decisional in nature (Box 3).14

Divergence in education vs work status. Persons with bipolar disorders often have substantial divergence between high educational attainment and lower work performance. When this is the case, all or most of the factors reviewed in this article probably have contributed. Mrs. S’s experience illustrates this aspect of our care for persons with bipolar disorders.

An employment barrier for some bipolar patients is that a brief, often long-past period of high intellectual or vocational performance serves as the benchmark for their capabilities. Patients with this characteristic resist revising their self-concept. Some treat the loss of this idealized image as an unfair consequence of their illness or society’s reaction to bipolar disorder. Their stubbornness tends to prevent realistic engagement socially or vocationally at levels that are presently feasible for them.

Resistance to change associated with this characteristic often is difficult to manage effectively with short, relatively infrequent medication-focused visits. Specific psychosocial interventions may be more effective.14

CASE CONTINUED: Finding a new balance

After leaving the stressful high-level job, Mrs. S next resolved to limit her search to half-time positions and took a job with limited responsibilities in a bookstore. Her work productivity was outstanding, but she became easily flustered when asked to assume additional responsibilities. Some of these required quick learning of new skills in inventory re-supply or interacting with dissatisfied customers.

As she became more confident and less fearful of being fired, Mrs. S talked with 2 supervisors about her illness management. This halted their well-intentioned efforts to promote her, based on their perception of her as talented and engaging.

Attention to these workplace issues took up approximately half of the time in her regular psychiatric appointments for more than 1 year. Through this process, Mrs. S developed increasingly effective insight into the complex mix of her accomplishments and resilience on one hand and her fluctuating social and vocational impairment on the other. She also recognized that subsyndromal symptoms continued at times, despite her overall good functional state. These insights and her greater self-confidence helped Mrs. S resolve and manage the divergences in her own and others’ perceptions of her capabilities and potential.

Related Resource

- Coping with depression or bipolar disorder at your job (patient information). Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. www.dbsalliance.org/site/PageServer?pagename=Employment_Information.

Disclosure

Dr. Bowden reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Mrs. S, age 34, worked as an office manager with responsibilities for more than 40 employees for 5 years. Starting in her mid 20s she had repeated periods of depression, binge drinking, and risk-taking that were treated ineffectively with antidepressants. Ultimately, she was fired from her job.

Eventually Mrs. S was diagnosed as bipolar and over time responded well to a mood-stabilizing regimen. She now desires to return to work, both for financial reasons and for the sense of accomplishment that comes from working. Initially, personnel managers review her résumé and tell her she would be bored by the routine nature of entry-level positions, or they offer her jobs with major responsibilities. She accepts a high-level position but soon leaves, feeling overwhelmed by the stress.

Bipolar disorder’s long-term course presents a therapeutic challenge when patients desire to remain employed, seek temporary or permanent disability status, or—most commonly—attempt to return to employment after a period of inability to work. As the experience of Mrs. S illustrates, previous capabilities that appear higher than the person’s present or recent work experience are a key issue to address in interpersonal therapy.

Evidence-based research is informative, but ultimately you must apply judgment and flexibility in setting and revising goals with the bipolar individual. Attention to the disorder’s core characteristics can help you equip patients for work that contributes to their pursuit of health.

Obstacles to employment

Role function. Bipolar disorder impairs family and social function in approximately one-half of persons with this diagnosis, a higher impairment rate than in persons with major depression.1

Cognitive function. Bipolar disorder patients have subtle sustained impairments in cognitive function, particularly working memory.2,3 These deficits—although generally much less severe than in persons with schizophrenia—contribute to workplace and educational difficulties.

Unstable mood. Some symptoms associated with elevated mood contribute to functional impairment. These are not limited to mania or hypomania but also can be prominent in mixed states and depression.

A study from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) found that two-thirds of 1,380 depressed bipolar I and II patients had ?1 concomitant symptoms principally associated with manic states. The most prominent were distractibility, pressured speech and thoughts, risky behavior, and agitation.4 Each of these—or, more often, all of these—can interfere with work responsibilities.

Circadian rhythm pattern. Sleep disturbances in bipolar disorder differ from those associated with other medical conditions. Bipolar patients’ tendency to increase their activity and interests in the evening may keep them awake into the early morning hours. Insufficient sleep and impaired daytime cognition and alertness related to idio syncratic circadian rhythms can interfere with job requirements.5 The structure of employment can help many bipolar patients maintain effective sleep patterns as well as waking activities (Box 1).

Some individuals recognize their disturbed activity pattern, but many view it simply as the way they approach a day. For the latter group, a sustained treatment effort is needed to help them recognize the adverse consequences of the pattern and develop a more effective daily routine.

Adverse treatment effects. Although important, this core medical issue is not central to the interpersonal focus of this article. The simple tolerability objective in prescribing medications—and less frequently therapies such as electroconvulsive treatment—is to avoid dosages that impair concentration, alertness, or motor speed and accuracy. Similarly, avoid medications that can cause physical changes noticeable to others—such as tremor, sleepiness, or significant weight gain—or adjust dosages to eliminate these side effects.

Work, defined as what we do to make a living, is useful for most individuals. For persons with bipolar disorder, work has additional benefits. Having a job aids in structuring their daily activities, which tend to be skewed by circadian rhythm-linked problems of inadequate sleep or sleep that starts too late and extends into the day. The routine expectations of a work schedule also can counteract the distractibility and unproductive multitasking common in some bipolar disorder patients.

These benefits are not guaranteed and vary considerably across occupational settings, but patients and family members readily understand this aspect of work. Its benefits can serve as an important impetus for patients to persist in efforts to attain employment, even in the face of obstacles.

Bipolar symptom domains

Anxiety is recognized as a separate and major domain in bipolar psychopathology,6 contributing strongly to poor outcomes. Although anxiety is somewhat more predominant in depression and mixed states, it is common in manic and recovered bipolar states as well.

Social anxiety and panic states appear to be most specifically associated with bipolar disorder.7 Because these types of anxiety entail excessive fearful responses, psychotherapeutic techniques including extinction approaches can be helpful.

Depression in bipolar disorder tends to manifest as slowed motor and cognitive function, which is likely to be evident in work situations. Additionally, loss of social interests—one of the most common and severe aspects of depression in bipolar disorders—is likely to be evident to coworkers and to negatively impact work effectiveness.

Irritability occurs most frequently in mixed bipolar states but also is characteristic of—though generally less intense in—depressed and manic clinical states. Even when strictly internal and subjective, irritability can reduce an individual’s confidence and work effectiveness. Expressed irritability, from minor annoyances to explosive outbursts, can have serious employment consequences, including termination.

Manic symptoms. The impulsivity that is common in bipolar mania can interfere with work. Acting without considering consequences, taking undue risks, or reaching conclusions on inadequate information can cause problems, including physical harm to self or coworkers. Excessive talking—usually associated with internally recognized racing thoughts—can be a nuisance when mild or problematic if it interferes with customer or coworker interactions.

Hyperactivity and increased energy may be perceived as behaviors that facilitate productivity at work (Box 2).8-10 The adaptive characteristics of many hypomanic states are infrequent or absent in depressive, manic, and mixed manic clinical states, however.

Psychosis is principally associated with manic episodes, but it can be a component of any symptomatic clinical state. Delusional ideas or persecutory thoughts are rarely compatible with a work environment, in part because of potential risks to others.

For some purposes, bipolar disease confers social and employment advantages. Common, frequently adaptive behavioral characteristics of hypomania include:

- perseverance

- high energy

- heightened perceptual sensitivity

- exuberance and playfulness

- optimism.

Increased energy and mild degrees of hyperactivity—as well as thinking along creative, multisystem lines—can benefit work productivity, customer interactions, and work group relations. Heightened confidence and social interests can be valuable in some sales and marketing activities.

Although these attitudes and behaviors can have constructive effects, patients need to understand their limits and destructive potential. This is not a straightforward issue, as patients may not have self-awareness of some adverse consequences of characteristics such as irritability, risk taking, or inappropriate sexual advances. A phenomenon little described in clinical literature but relatively common in biographical accounts of persons with bipolar disorder is that friends or coworkers may encourage, rationalize, and take advantage of an individual’s hypomanic energy, thwarting effective interventions.

Componential treatment

Bipolar disorder’s multiple symptom domains suggest a componential approach to treatment. It may be useful to convey this concept metaphorically to the patient. When working on a jigsaw puzzle, a section that has been put together can be largely left intact and attention turned to other sections of the puzzle. Similarly, once a particular bipolar component is well managed—whether via medication, lifestyle, attitudes, or combinations of these—that symptom is likely to remain stable, barring a new insult/stressor (such as a medical condition requiring drugs that interfere with the bipolar regimen).

If mood stabilizers control risky behavior, impulsivity, and affective lability, the regimen generally will remain effective. If residual or new problems develop in another area (such as anxiety, sleep cycle, or irritability), choose drug regimens and psychoeducation approaches that are compatible with the mood-stabilizing plan. This attitude toward treatment:

- is reassuring to most patients, who come to see a new or recurring problem in one domain as not inherently a harbinger of complete relapse

- can reduce patient- or clinician-initiated deletions and additions of medications in a regimen that has been established as effective.

Autobiographical accounts of persons with bipolar disorders can be useful in educating patients about the considerations presented here. Actress Patty Duke made these observations in describing the gradual development of an effective treatment for her severe bipolar disorder:

I work at not flying off the handle…and I’m much better at it. My general medical bills dropped by $50,000 a year since my bipolar diagnosis and treatment. Until then, I was always in the hospital for some phantom illness. I was there with real symptoms born of depression. I haven’t been in the hospital since I was diagnosed.

My recovery from manic-depression has been an evolution, not a sudden miracle. For someone who spent 50% of her life screaming and yelling about something, I am now down to, say, 5%.11

Psychosocial factors to consider

Stigma in the workplace. Although most coworkers are tolerant of and fair-minded about the functional difficulties common in symptomatic bipolar disorder, some will have biased, inaccurate views about psychiatric conditions. Advise bipolar individuals to make case-by-case decisions about whether to provide personal information to other employees and, if so, how much.

As with most medical conditions, the default choice will be to not discuss personal information in the workplace. Some coworkers, however, might appreciate learning of the bipolar condition (for example, a supervisor who seems empathic to an employee’s seeming stressed state).

Realistic expectations. Most clinicians recognize that relief from a syndromal bipolar state is achieved more quickly than a sustained recovered status in which symptoms are minimal. Attaining functional capacity in a normal range also lags, both in time and in the proportion of persons who ever achieve sustained good function.12 Patients, their families, and often employers may have unrealistic expectations about early resumption of work after a depressive or manic episode resolves.

Ethnic considerations. Some literature suggests ethnic differences in the initial presentation of bipolar disorder, with more severe manifestations in some populations particularly if psychosis is a component symptom.13 Additionally, some cultural views about stigma from illness can add to patients’ or family members’ reluctance to re-enter the workplace.

Socioeconomic status. Sometimes bipolar illness puts out of reach the occupational activities that an individual has previously undertaken or that are characteristic of the family’s experience and expectations. Resistance to a change in self-concept can add to the difficulty in successfully moving a patient to consider employment that is more routinized and less intellectual or decisional in nature (Box 3).14

Divergence in education vs work status. Persons with bipolar disorders often have substantial divergence between high educational attainment and lower work performance. When this is the case, all or most of the factors reviewed in this article probably have contributed. Mrs. S’s experience illustrates this aspect of our care for persons with bipolar disorders.

An employment barrier for some bipolar patients is that a brief, often long-past period of high intellectual or vocational performance serves as the benchmark for their capabilities. Patients with this characteristic resist revising their self-concept. Some treat the loss of this idealized image as an unfair consequence of their illness or society’s reaction to bipolar disorder. Their stubbornness tends to prevent realistic engagement socially or vocationally at levels that are presently feasible for them.

Resistance to change associated with this characteristic often is difficult to manage effectively with short, relatively infrequent medication-focused visits. Specific psychosocial interventions may be more effective.14

CASE CONTINUED: Finding a new balance

After leaving the stressful high-level job, Mrs. S next resolved to limit her search to half-time positions and took a job with limited responsibilities in a bookstore. Her work productivity was outstanding, but she became easily flustered when asked to assume additional responsibilities. Some of these required quick learning of new skills in inventory re-supply or interacting with dissatisfied customers.

As she became more confident and less fearful of being fired, Mrs. S talked with 2 supervisors about her illness management. This halted their well-intentioned efforts to promote her, based on their perception of her as talented and engaging.

Attention to these workplace issues took up approximately half of the time in her regular psychiatric appointments for more than 1 year. Through this process, Mrs. S developed increasingly effective insight into the complex mix of her accomplishments and resilience on one hand and her fluctuating social and vocational impairment on the other. She also recognized that subsyndromal symptoms continued at times, despite her overall good functional state. These insights and her greater self-confidence helped Mrs. S resolve and manage the divergences in her own and others’ perceptions of her capabilities and potential.

Related Resource

- Coping with depression or bipolar disorder at your job (patient information). Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. www.dbsalliance.org/site/PageServer?pagename=Employment_Information.

Disclosure

Dr. Bowden reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, et al. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(suppl 4):AS264-AS279.

2. Glahn D, Bearden CE, Barguil M, et al. The neurocognitive signature of psychotic bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:910-916.

3. Goodwin G, Martinez-Aran A, Glahn DC, et al. Cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: neurodevelopment or neurodegeneration? An ECNP expert meeting report. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2008;18:787-793.

4. Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Bowden CL, et al. Manic symptoms during depressive episodes in 1,380 patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):173-181.

5. Mansour HA, Wood J, Chowdari KV, et al. Circadian phase variation in bipolar I disorder. Chronobiol Int. 2005;22(3):571-584.

6. Feske U, Frank E, Mallinger AG, et al. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;57:956-962.

7. Mantere O, Melartin TK, Suominen K, et al. Difference in axis I and II comorbidities between bipolar I and II disorder and major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:584-593.

8. Bowden CL. Bipolar disorder and creativity. In: Shaw MP, Runco MA, eds. Creativity and affect. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corp; 1994:73-86.

9. Andreasen N, Powers S. Overinclusive thinking in mania and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;125:452-456.

10. Solovay MR, Shenton ME, Holzman PS. Comparative studies of thought disorders. I. Mania and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:13-20.

11. Duke P, Hochman G. A brilliant madness: living with manic-depressive illness. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1997.

12. Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, et al. The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:720-727.

13. Kennedy N, Boydell J, van Os J, et al. Ethnic differences in first clinical presentation of bipolar disorder: results from an epidemiological study. J Affect Dis. 2004;83:161-168.

14. Mikowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ. Bipolar disorder: a family-focused approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006.

1. Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, et al. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(suppl 4):AS264-AS279.

2. Glahn D, Bearden CE, Barguil M, et al. The neurocognitive signature of psychotic bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:910-916.

3. Goodwin G, Martinez-Aran A, Glahn DC, et al. Cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: neurodevelopment or neurodegeneration? An ECNP expert meeting report. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2008;18:787-793.

4. Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Bowden CL, et al. Manic symptoms during depressive episodes in 1,380 patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):173-181.

5. Mansour HA, Wood J, Chowdari KV, et al. Circadian phase variation in bipolar I disorder. Chronobiol Int. 2005;22(3):571-584.

6. Feske U, Frank E, Mallinger AG, et al. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;57:956-962.

7. Mantere O, Melartin TK, Suominen K, et al. Difference in axis I and II comorbidities between bipolar I and II disorder and major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:584-593.

8. Bowden CL. Bipolar disorder and creativity. In: Shaw MP, Runco MA, eds. Creativity and affect. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corp; 1994:73-86.

9. Andreasen N, Powers S. Overinclusive thinking in mania and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;125:452-456.

10. Solovay MR, Shenton ME, Holzman PS. Comparative studies of thought disorders. I. Mania and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:13-20.

11. Duke P, Hochman G. A brilliant madness: living with manic-depressive illness. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1997.

12. Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, et al. The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:720-727.

13. Kennedy N, Boydell J, van Os J, et al. Ethnic differences in first clinical presentation of bipolar disorder: results from an epidemiological study. J Affect Dis. 2004;83:161-168.

14. Mikowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ. Bipolar disorder: a family-focused approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006.

Tips to differentiate bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder

Unipolar depression or "soft" bipolar disorder? Tips to avoid misdiagnosis

Controversies in bipolar disorder: Trust evidence or experience?

Today’s buzzword in health care is evidence-based medicine. Most clinicians would agree that evidence from clinical research should guide decisions about treating bipolar disorder. In theory, randomized controlled trials should tell us how to manage bipolar patients and achieve therapeutic success. page 40.)

We rarely have encountered a patient with postpartum depression or psychosis who does not have a history of (often undiagnosed and untreated) recurrent mood episodes. For most of these patients, a mood stabilizer may be a better choice than an antidepressant.

The role of thyroid hormones

Adding a thyroid hormone—usually liothyronine—to an antidepressant has been demonstrated to accelerate, page 47.)

Atypical depression and the bipolar spectrum

Depressive episodes are considered either “typical” (a category that includes melancholic depression—in DSM-IV-TR, major depression with melancholic features) or “atypical” (in DSM-IV-TR, major depression with atypical features). Atypical features were originally associated with response to monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants, whereas non atypical depression was thought more likely to respond to tricyclic antidepressants.34 The depression of bipolar disorder is usually atypical ( Box 4 ), especially in patients with softer variants of the illness.35

We believe that depressed patients with atypical symptoms aggregate into groups according to the presence, severity, and character of interdepressive manic or hypomanic episodes. Some patients experience recurrent depressive episodes with intervening euthymia (recurrent major depression), whereas others experience depressive episodes punctuated by brief subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Patients in these groups occasionally tolerate or even benefit from cautiously managed antidepressant monotherapy. Patients with atypical depressive episodes alternating with frank hypomanic, manic, mixed, or manic-psychotic episodes usually require a mood stabilizer and may benefit from cotreatment with an atypical antipsychotic.

Akiskol and Benazzi35 suggest that atypical depression may be a subtype of the bipolar spectrum. Our experience suggests that the bipolar spectrum is a continuum of degrees of risk for mood instability in persons with recurrent atypical depression.

DSM-IV-TR defines atypical depression as depression characterized by mood reactivity and at least 2 of these 4 features:

- hypersomnia

- increased appetite or weight gain

- leaden paralysis

- sensitivity to interpersonal rejection.

The term ‘hypersomnia’ is misleading. Many of these patients do not sleep excessively because work or school attendance prevents oversleeping. Instead, they experience an increased sleep requirement manifested by difficulty getting up in the morning and increased daytime sleepiness.

Increased appetite and weight gain (hyperphagia) often are present, but almost as often our patients report no change in appetite or weight or even anorexia and weight loss.

We rarely see a condition one would term ‘leaden paralysis.’ We also find that ‘sensitivity to interpersonal rejection’ is too narrow a construct. Our patients with atypical depression experience increased sensitivity to every stressor in their lives—work, school, family, and social stressors—not just interpersonal rejection.

Related resources

- Lieber AL. Bipolar spectrum disorder: an overview of the soft bipolar spectrum. www.psycom.net/depression.central.lieber.html.

- Phelps J. Why am I still depressed? Recognizing and managing the ups and downs of bipolar II and soft bipolar disorder. www.psycheducation.org.

- Maier T. Evidence-based psychiatry: understanding the limitations of a method. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):325.

Drug brand names

- Liothyronine • Cytomel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Goldberg JF. What constitutes evidence-based pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder? Part 1: First-line treatments. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1982-1983.

2. Goldberg JF. What constitutes evidence-based pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder? Part 2: Complex presentations and clinical context. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:495-496.

3. Levine R, Fink M. Why evidence-based medicine cannot be applied to psychiatry. Psychiatric Times. 2008;25(4):10.

4. Akiskol HS, Benazzi F. The DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories of recurrent [major] depressive and bipolar II disorders: evidence that they lie on a dimensional spectrum. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:45-54.

5. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:3–27.

6. Hirschfeld RMA, Lewis L, Vornik L. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(2):161-167.

7. Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, et al. Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1005-1010.

8. Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:565-569.

9. Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:804-808.

10. Gijsman HF, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, et al. Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;161:1537-1547.

11. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:134-144.

12. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1711-1722.

13. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1252-1262.

14. Akiskol HS. Developmental pathways to bipolarity: are juvenile-onset depressions pre-bipolar? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(6):754-763.

15. Geller B, Zimmerman B, Williams M, et al. Bipolar disorder at prospective follow-up of adults who had prepubertal major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:125-127.

16. Food and Drug Administration: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Revisions to product labeling. Available at: http://www.FDA.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/default.htm. Accessed January 12, 2009.

17. McElroy S, Strakowski S, West S, et al. Phenomenology of adolescent and adult mania in hospitalized patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:44-49.

18. Olfson M, Marcus SC. A case-control study of antidepressants and attempted suicide during early phase treatment of major depressive episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:425-432.

19. Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Havens JR, et al. Psychosis in bipolar disorder: phenomenology and impact on morbidity and course of illness. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:263-269.

20. Jones I, Craddock N. Familiarity of the puerperal trigger in bipolar disorder: results of a family study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:913-917.

21. Chaudron LH, Pies RW. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1284-1292.

22. Wisner KL, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH. Psychiatric episodes in women and young children. J Affect Disord. 1995;34:1-11.

23. Sharma V. A cautionary note on the use of antidepressants in postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:411-414.

24. O’Malley S. “Are you there alone?” The unspeakable crime of Andrea Yates. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2004.

25. Altshuler LL, Bauer M, Frye MA, et al. Does thyroid supplementation accelerate tricyclic antidepressant response? A review and meta-analysis of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1617-1622.

26. Joffe RT. The use of thyroid supplements to augment antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;59:26-29.

27. Cooper-Kazaz R, Apter JT, Cohen R, et al. Combined treatment with sertraline and liothyronine in major depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:679-688.

28. Gold MS, Pottash AL, Extein I. Hypothyroidism and depression: evidence from complete thyroid function evaluation. JAMA. 1981;245:28-31.

29. Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Post RM, et al. High rate of autoimmune thyroiditis in bipolar disorder: lack of association with lithium exposure. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:305-311.

30. Szuba MP, Amsterdam JD. Rapid antidepressant response after nocturnal TRH administration in patients with bipolar I and bipolar type II major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:325-330.

31. Extein I, Pottash AL, Gold MS. Does subclinical hypothyroidism predispose to tricyclic-induced rapid mood cycles? J Clin Psychiatry. 1982;43:32-33.

32. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Endocr Prac. 2002;8:457-469.

33. El-Mallakh RS, Karippott A. Antidepressant-associated chronic irritable dysphoria (ACID) in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:267-272.

34. Henkl V, Mergl R, Antje-Kathrin A, et al. Treatment of depression with atypical features: a meta-analytic approach. Psychiatry Res. 2006;141(1):89-101.

35. Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Lattanzi D, et al. The high prevalence of “soft” bipolar (II) features in atypical depression. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(2):63-71.

Today’s buzzword in health care is evidence-based medicine. Most clinicians would agree that evidence from clinical research should guide decisions about treating bipolar disorder. In theory, randomized controlled trials should tell us how to manage bipolar patients and achieve therapeutic success. page 40.)

We rarely have encountered a patient with postpartum depression or psychosis who does not have a history of (often undiagnosed and untreated) recurrent mood episodes. For most of these patients, a mood stabilizer may be a better choice than an antidepressant.

The role of thyroid hormones

Adding a thyroid hormone—usually liothyronine—to an antidepressant has been demonstrated to accelerate, page 47.)

Atypical depression and the bipolar spectrum

Depressive episodes are considered either “typical” (a category that includes melancholic depression—in DSM-IV-TR, major depression with melancholic features) or “atypical” (in DSM-IV-TR, major depression with atypical features). Atypical features were originally associated with response to monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants, whereas non atypical depression was thought more likely to respond to tricyclic antidepressants.34 The depression of bipolar disorder is usually atypical ( Box 4 ), especially in patients with softer variants of the illness.35

We believe that depressed patients with atypical symptoms aggregate into groups according to the presence, severity, and character of interdepressive manic or hypomanic episodes. Some patients experience recurrent depressive episodes with intervening euthymia (recurrent major depression), whereas others experience depressive episodes punctuated by brief subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Patients in these groups occasionally tolerate or even benefit from cautiously managed antidepressant monotherapy. Patients with atypical depressive episodes alternating with frank hypomanic, manic, mixed, or manic-psychotic episodes usually require a mood stabilizer and may benefit from cotreatment with an atypical antipsychotic.

Akiskol and Benazzi35 suggest that atypical depression may be a subtype of the bipolar spectrum. Our experience suggests that the bipolar spectrum is a continuum of degrees of risk for mood instability in persons with recurrent atypical depression.

DSM-IV-TR defines atypical depression as depression characterized by mood reactivity and at least 2 of these 4 features:

- hypersomnia

- increased appetite or weight gain

- leaden paralysis

- sensitivity to interpersonal rejection.

The term ‘hypersomnia’ is misleading. Many of these patients do not sleep excessively because work or school attendance prevents oversleeping. Instead, they experience an increased sleep requirement manifested by difficulty getting up in the morning and increased daytime sleepiness.

Increased appetite and weight gain (hyperphagia) often are present, but almost as often our patients report no change in appetite or weight or even anorexia and weight loss.

We rarely see a condition one would term ‘leaden paralysis.’ We also find that ‘sensitivity to interpersonal rejection’ is too narrow a construct. Our patients with atypical depression experience increased sensitivity to every stressor in their lives—work, school, family, and social stressors—not just interpersonal rejection.

Related resources

- Lieber AL. Bipolar spectrum disorder: an overview of the soft bipolar spectrum. www.psycom.net/depression.central.lieber.html.

- Phelps J. Why am I still depressed? Recognizing and managing the ups and downs of bipolar II and soft bipolar disorder. www.psycheducation.org.

- Maier T. Evidence-based psychiatry: understanding the limitations of a method. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):325.

Drug brand names

- Liothyronine • Cytomel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Today’s buzzword in health care is evidence-based medicine. Most clinicians would agree that evidence from clinical research should guide decisions about treating bipolar disorder. In theory, randomized controlled trials should tell us how to manage bipolar patients and achieve therapeutic success. page 40.)

We rarely have encountered a patient with postpartum depression or psychosis who does not have a history of (often undiagnosed and untreated) recurrent mood episodes. For most of these patients, a mood stabilizer may be a better choice than an antidepressant.

The role of thyroid hormones

Adding a thyroid hormone—usually liothyronine—to an antidepressant has been demonstrated to accelerate, page 47.)

Atypical depression and the bipolar spectrum

Depressive episodes are considered either “typical” (a category that includes melancholic depression—in DSM-IV-TR, major depression with melancholic features) or “atypical” (in DSM-IV-TR, major depression with atypical features). Atypical features were originally associated with response to monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants, whereas non atypical depression was thought more likely to respond to tricyclic antidepressants.34 The depression of bipolar disorder is usually atypical ( Box 4 ), especially in patients with softer variants of the illness.35

We believe that depressed patients with atypical symptoms aggregate into groups according to the presence, severity, and character of interdepressive manic or hypomanic episodes. Some patients experience recurrent depressive episodes with intervening euthymia (recurrent major depression), whereas others experience depressive episodes punctuated by brief subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Patients in these groups occasionally tolerate or even benefit from cautiously managed antidepressant monotherapy. Patients with atypical depressive episodes alternating with frank hypomanic, manic, mixed, or manic-psychotic episodes usually require a mood stabilizer and may benefit from cotreatment with an atypical antipsychotic.

Akiskol and Benazzi35 suggest that atypical depression may be a subtype of the bipolar spectrum. Our experience suggests that the bipolar spectrum is a continuum of degrees of risk for mood instability in persons with recurrent atypical depression.

DSM-IV-TR defines atypical depression as depression characterized by mood reactivity and at least 2 of these 4 features:

- hypersomnia

- increased appetite or weight gain

- leaden paralysis

- sensitivity to interpersonal rejection.

The term ‘hypersomnia’ is misleading. Many of these patients do not sleep excessively because work or school attendance prevents oversleeping. Instead, they experience an increased sleep requirement manifested by difficulty getting up in the morning and increased daytime sleepiness.

Increased appetite and weight gain (hyperphagia) often are present, but almost as often our patients report no change in appetite or weight or even anorexia and weight loss.

We rarely see a condition one would term ‘leaden paralysis.’ We also find that ‘sensitivity to interpersonal rejection’ is too narrow a construct. Our patients with atypical depression experience increased sensitivity to every stressor in their lives—work, school, family, and social stressors—not just interpersonal rejection.

Related resources

- Lieber AL. Bipolar spectrum disorder: an overview of the soft bipolar spectrum. www.psycom.net/depression.central.lieber.html.

- Phelps J. Why am I still depressed? Recognizing and managing the ups and downs of bipolar II and soft bipolar disorder. www.psycheducation.org.

- Maier T. Evidence-based psychiatry: understanding the limitations of a method. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):325.

Drug brand names

- Liothyronine • Cytomel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Goldberg JF. What constitutes evidence-based pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder? Part 1: First-line treatments. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1982-1983.

2. Goldberg JF. What constitutes evidence-based pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder? Part 2: Complex presentations and clinical context. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:495-496.

3. Levine R, Fink M. Why evidence-based medicine cannot be applied to psychiatry. Psychiatric Times. 2008;25(4):10.

4. Akiskol HS, Benazzi F. The DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories of recurrent [major] depressive and bipolar II disorders: evidence that they lie on a dimensional spectrum. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:45-54.

5. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:3–27.

6. Hirschfeld RMA, Lewis L, Vornik L. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(2):161-167.

7. Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, et al. Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1005-1010.

8. Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:565-569.

9. Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:804-808.

10. Gijsman HF, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, et al. Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;161:1537-1547.

11. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:134-144.

12. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1711-1722.

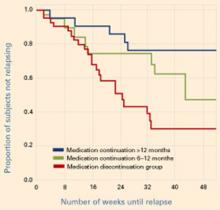

13. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1252-1262.

14. Akiskol HS. Developmental pathways to bipolarity: are juvenile-onset depressions pre-bipolar? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(6):754-763.

15. Geller B, Zimmerman B, Williams M, et al. Bipolar disorder at prospective follow-up of adults who had prepubertal major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:125-127.

16. Food and Drug Administration: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Revisions to product labeling. Available at: http://www.FDA.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/default.htm. Accessed January 12, 2009.

17. McElroy S, Strakowski S, West S, et al. Phenomenology of adolescent and adult mania in hospitalized patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:44-49.

18. Olfson M, Marcus SC. A case-control study of antidepressants and attempted suicide during early phase treatment of major depressive episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:425-432.

19. Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Havens JR, et al. Psychosis in bipolar disorder: phenomenology and impact on morbidity and course of illness. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:263-269.

20. Jones I, Craddock N. Familiarity of the puerperal trigger in bipolar disorder: results of a family study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:913-917.

21. Chaudron LH, Pies RW. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1284-1292.

22. Wisner KL, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH. Psychiatric episodes in women and young children. J Affect Disord. 1995;34:1-11.

23. Sharma V. A cautionary note on the use of antidepressants in postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:411-414.

24. O’Malley S. “Are you there alone?” The unspeakable crime of Andrea Yates. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2004.

25. Altshuler LL, Bauer M, Frye MA, et al. Does thyroid supplementation accelerate tricyclic antidepressant response? A review and meta-analysis of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1617-1622.

26. Joffe RT. The use of thyroid supplements to augment antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;59:26-29.

27. Cooper-Kazaz R, Apter JT, Cohen R, et al. Combined treatment with sertraline and liothyronine in major depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:679-688.

28. Gold MS, Pottash AL, Extein I. Hypothyroidism and depression: evidence from complete thyroid function evaluation. JAMA. 1981;245:28-31.

29. Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Post RM, et al. High rate of autoimmune thyroiditis in bipolar disorder: lack of association with lithium exposure. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:305-311.

30. Szuba MP, Amsterdam JD. Rapid antidepressant response after nocturnal TRH administration in patients with bipolar I and bipolar type II major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:325-330.

31. Extein I, Pottash AL, Gold MS. Does subclinical hypothyroidism predispose to tricyclic-induced rapid mood cycles? J Clin Psychiatry. 1982;43:32-33.

32. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Endocr Prac. 2002;8:457-469.

33. El-Mallakh RS, Karippott A. Antidepressant-associated chronic irritable dysphoria (ACID) in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:267-272.

34. Henkl V, Mergl R, Antje-Kathrin A, et al. Treatment of depression with atypical features: a meta-analytic approach. Psychiatry Res. 2006;141(1):89-101.

35. Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Lattanzi D, et al. The high prevalence of “soft” bipolar (II) features in atypical depression. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(2):63-71.

1. Goldberg JF. What constitutes evidence-based pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder? Part 1: First-line treatments. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1982-1983.

2. Goldberg JF. What constitutes evidence-based pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder? Part 2: Complex presentations and clinical context. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:495-496.

3. Levine R, Fink M. Why evidence-based medicine cannot be applied to psychiatry. Psychiatric Times. 2008;25(4):10.

4. Akiskol HS, Benazzi F. The DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories of recurrent [major] depressive and bipolar II disorders: evidence that they lie on a dimensional spectrum. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:45-54.

5. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:3–27.

6. Hirschfeld RMA, Lewis L, Vornik L. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(2):161-167.

7. Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, et al. Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1005-1010.

8. Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:565-569.

9. Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:804-808.

10. Gijsman HF, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, et al. Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;161:1537-1547.

11. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:134-144.

12. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1711-1722.

13. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al. Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1252-1262.

14. Akiskol HS. Developmental pathways to bipolarity: are juvenile-onset depressions pre-bipolar? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(6):754-763.

15. Geller B, Zimmerman B, Williams M, et al. Bipolar disorder at prospective follow-up of adults who had prepubertal major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:125-127.

16. Food and Drug Administration: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Revisions to product labeling. Available at: http://www.FDA.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/default.htm. Accessed January 12, 2009.