User login

Novel chip system could improve preclinical drug studies

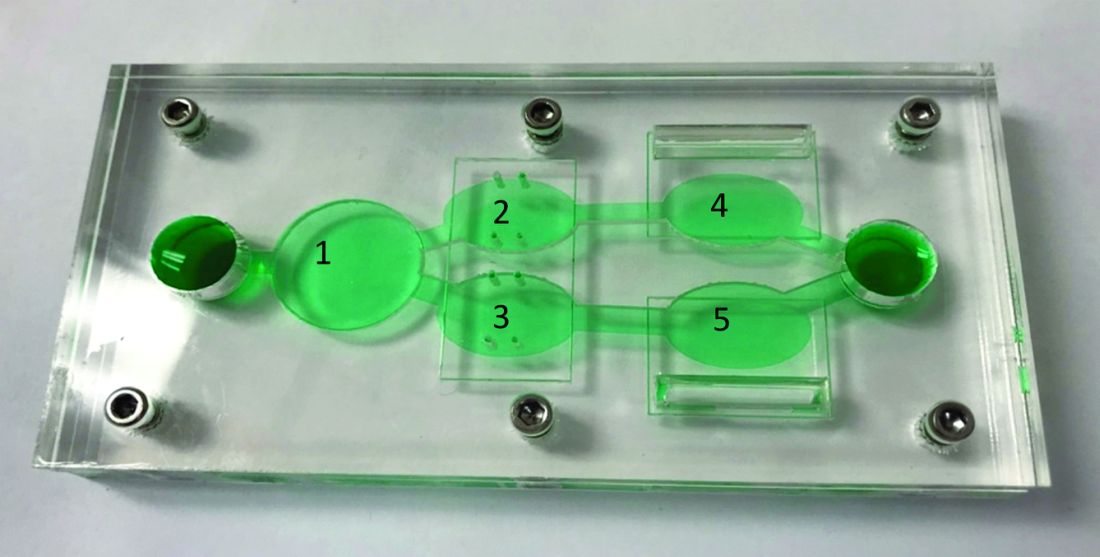

A novel multiorgan body-on-a-chip system shows promise to improve the preclinical evaluation of various anticancer therapies, investigators report.

“Initially, organ-on-a-chip systems were designed for specific applications with limited ability for reconfiguration and typically with cells from a single organ,” wrote Christopher W. McAleer, PhD, of Hesperos Inc., Orlando, and colleagues. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

“To address these issues, a reconfigurable body-on-a-chip system was developed with the capacity to house multiple organ-like tissue constructs,” the authors explained.

The researchers used two different system configurations to evaluate the off-target organ toxicities, metabolism, and efficacy of diclofenac and imatinib (system 1), in addition to tamoxifen (system 2). Both therapies were combined with verapamil in the study.

In system 1, cancer-derived bone marrow cells were cultured with primary hepatocytes, and were analyzed for anti-leukemic activity. In this configuration, both imatinib and diclofenac showed cytostatic activity on cancer progression in the bone marrow cells.

“Liver viability was not affected by imatinib; however, diclofenac reduced liver viability by 30%,” the researchers wrote.

System 2 included a wide variety of cell-lines, including primary hepatocytes, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, a multidrug-resistant vulva cancer line, and a non-multidrug-resistant breast cancer line.

In this configuration, tamoxifen monotherapy and tamoxifen coadministered with verapamil resulted in off-target cardiac toxicities, but did not alter cell viability.

“These systems demonstrate the utility of a human cell–based in vitro culture system to evaluate both on-target efficacy and off-target toxicity for parent drugs and their metabolites,” Dr. McAleer and colleagues wrote.

The researchers acknowledged that the dosing parameters used in the model were acute. As a result, chronic, low-dose treatment strategies may reflect clinical conditions more accurately.

“These systems can augment and reduce the use of animals and increase the efficiency of drug evaluations in preclinical studies,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Hesperos Internal Development funds, the NIH, and Roche. The authors reported financial affiliations with Hesperos and Roche.

SOURCE: McAleer CW et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1386.

A novel multiorgan body-on-a-chip system shows promise to improve the preclinical evaluation of various anticancer therapies, investigators report.

“Initially, organ-on-a-chip systems were designed for specific applications with limited ability for reconfiguration and typically with cells from a single organ,” wrote Christopher W. McAleer, PhD, of Hesperos Inc., Orlando, and colleagues. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

“To address these issues, a reconfigurable body-on-a-chip system was developed with the capacity to house multiple organ-like tissue constructs,” the authors explained.

The researchers used two different system configurations to evaluate the off-target organ toxicities, metabolism, and efficacy of diclofenac and imatinib (system 1), in addition to tamoxifen (system 2). Both therapies were combined with verapamil in the study.

In system 1, cancer-derived bone marrow cells were cultured with primary hepatocytes, and were analyzed for anti-leukemic activity. In this configuration, both imatinib and diclofenac showed cytostatic activity on cancer progression in the bone marrow cells.

“Liver viability was not affected by imatinib; however, diclofenac reduced liver viability by 30%,” the researchers wrote.

System 2 included a wide variety of cell-lines, including primary hepatocytes, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, a multidrug-resistant vulva cancer line, and a non-multidrug-resistant breast cancer line.

In this configuration, tamoxifen monotherapy and tamoxifen coadministered with verapamil resulted in off-target cardiac toxicities, but did not alter cell viability.

“These systems demonstrate the utility of a human cell–based in vitro culture system to evaluate both on-target efficacy and off-target toxicity for parent drugs and their metabolites,” Dr. McAleer and colleagues wrote.

The researchers acknowledged that the dosing parameters used in the model were acute. As a result, chronic, low-dose treatment strategies may reflect clinical conditions more accurately.

“These systems can augment and reduce the use of animals and increase the efficiency of drug evaluations in preclinical studies,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Hesperos Internal Development funds, the NIH, and Roche. The authors reported financial affiliations with Hesperos and Roche.

SOURCE: McAleer CW et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1386.

A novel multiorgan body-on-a-chip system shows promise to improve the preclinical evaluation of various anticancer therapies, investigators report.

“Initially, organ-on-a-chip systems were designed for specific applications with limited ability for reconfiguration and typically with cells from a single organ,” wrote Christopher W. McAleer, PhD, of Hesperos Inc., Orlando, and colleagues. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

“To address these issues, a reconfigurable body-on-a-chip system was developed with the capacity to house multiple organ-like tissue constructs,” the authors explained.

The researchers used two different system configurations to evaluate the off-target organ toxicities, metabolism, and efficacy of diclofenac and imatinib (system 1), in addition to tamoxifen (system 2). Both therapies were combined with verapamil in the study.

In system 1, cancer-derived bone marrow cells were cultured with primary hepatocytes, and were analyzed for anti-leukemic activity. In this configuration, both imatinib and diclofenac showed cytostatic activity on cancer progression in the bone marrow cells.

“Liver viability was not affected by imatinib; however, diclofenac reduced liver viability by 30%,” the researchers wrote.

System 2 included a wide variety of cell-lines, including primary hepatocytes, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, a multidrug-resistant vulva cancer line, and a non-multidrug-resistant breast cancer line.

In this configuration, tamoxifen monotherapy and tamoxifen coadministered with verapamil resulted in off-target cardiac toxicities, but did not alter cell viability.

“These systems demonstrate the utility of a human cell–based in vitro culture system to evaluate both on-target efficacy and off-target toxicity for parent drugs and their metabolites,” Dr. McAleer and colleagues wrote.

The researchers acknowledged that the dosing parameters used in the model were acute. As a result, chronic, low-dose treatment strategies may reflect clinical conditions more accurately.

“These systems can augment and reduce the use of animals and increase the efficiency of drug evaluations in preclinical studies,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Hesperos Internal Development funds, the NIH, and Roche. The authors reported financial affiliations with Hesperos and Roche.

SOURCE: McAleer CW et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1386.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A novel multiorgan body-on-a-chip system shows promise to improve the preclinical evaluation of anticancer therapies.

Major finding: Overall, results support the utility of the system to assess both off-target toxicity and on-target efficacy for various anticancer drugs.

Study details: A study exploring the utility of a multi-organ-on-a-chip system to assess safety and effectiveness of anticancer therapies in the preclinical setting.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Hesperos Internal Development funds, the NIH, and Roche. The authors reported financial affiliations with Hesperos and Roche.

Source: McAleer CW et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1386.

PALOMA-3 biomarker analysis: Liquid biopsy could ID progression risk

CHICAGO – Tumor protein 53 (TP53) mutation, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) amplification, and tumor purity in plasma each predict early progression on palbociclib and/or fulvestrant in patients with advanced estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) breast cancer, according to genomic analyses of PALOMA-3 trial data.

Overall, the presence of one or more of these genomic changes identified 131 out of 310 patients from the phase 3 trial who had baseline samples available, Ben O’Leary, MBBS, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“So, a significant minority of patients – 42.3% – potentially who fall into a more poor-prognosis group,” said Dr. O’Leary of the Institute of Cancer Research at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London.

The findings suggest that a “liquid biopsy” at the start of treatment could identify patients at risk for progression.

The PALOMA-3 trial randomized 521 patients with ER+, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative advanced breast cancer who had previously progressed on endocrine therapy 2:1 to CDK4/CDK6 inhibition with palbociclib plus fulvestrant (P+F) or placebo plus fulvestrant (F), and it showed that adding palbociclib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) (N Engl J Med. Jul 16 2015;373:209-19).

For the current analysis, the investigators assessed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in baseline plasma samples from 459 study participants in an effort to identify genomic biomarkers for progression, to examine the association between baseline tumor fraction and clinical outcome, and to explore differences in predictive markers by treatment arm. A custom amplicon-sequencing analysis was performed to look for mutations in 17 different relevant genes, and another was used to estimate tumor fraction by looking at about 800 common germline single-nucleotide polymorphisms and to assess copy-number gain in the amplification status in 11 different genes, Dr. O’Leary said.

Results for mutations and circulating nucleic acids were available in 203 and 107 patients from the P+F and F groups, respectively, and on multivariable analysis of all 310 patients (including palbociclib as a variable in the model and with ctDNA fraction as a continuous variable), higher baseline tumor purity in plasma was associated with highly significantly worse PFS (HR 1.2 per 10% increase in purity), and baseline TP53 mutation and FGFR1 amplification each were associated with significantly shorter PFS (HRs, 1.8 and 2.9, respectively).

“[It is] very important to note ... that we did look specifically for interaction between our genomic changes and treatment, and we didn’t find any evidence of a significant interaction, so these genomic markers [are] prognostic rather than predictive in terms of the two treatment arms of the trial,” he said.

A survival analysis showed a median PFS of 3.7 vs. 12.7 months in patients with vs. without TP53 mutation in the P+F arm, and 1.8 vs. 5.4 months, respectively, in the F arm, with similar HRs of 2.0 and 2.3 in the arms, respectively.

“Even in the [P+F] arm, you see almost half of the patients with a TP53 mutation ... have relapsed by 2 months, the earliest clinical assessment in the trial,” he noted.

For FGFR1, the PFS was 3.9 vs. 12 months with vs. without amplification in the P+F arms, and 1.8 vs. 5.8 months, respectively in th F arm, with HRs of 3.4 and 3.6, respectively.

These findings are notable because markers of early progression on endocrine therapy in combination with CDK4/6 inhibitors remain limited – despite the key role of these combinations in treating ER+ advanced breast cancer, Dr. O’Leary explained.

“Although many patients derive a great deal of benefit from these combinations, there are a subset of patients who will relapse relatively early, and ... we don’t have an established means of identifying those patients at the present,” he said. “From the technical perspective, liquid biopsies have emerged in recent years as a promising means of genotyping patients’ cancers from circulating tumor DNA, and in addition, the overall level of circulating tumor DNA – the fractional purity – has been associated with poor prognosis, specifically in the triple-negative breast cancer setting.”

The results, which require independent validation, could potentially inform future clinical trials of CDK4/6 inhibitor combinations in advanced ER+ breast cancer to identify a high-risk group of patients who require escalation of therapy, he concluded.

Dr. O’Leary reported receiving research funding from Pfizer to his institution.

SOURCE: O’Leary B et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 1010.

CHICAGO – Tumor protein 53 (TP53) mutation, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) amplification, and tumor purity in plasma each predict early progression on palbociclib and/or fulvestrant in patients with advanced estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) breast cancer, according to genomic analyses of PALOMA-3 trial data.

Overall, the presence of one or more of these genomic changes identified 131 out of 310 patients from the phase 3 trial who had baseline samples available, Ben O’Leary, MBBS, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“So, a significant minority of patients – 42.3% – potentially who fall into a more poor-prognosis group,” said Dr. O’Leary of the Institute of Cancer Research at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London.

The findings suggest that a “liquid biopsy” at the start of treatment could identify patients at risk for progression.

The PALOMA-3 trial randomized 521 patients with ER+, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative advanced breast cancer who had previously progressed on endocrine therapy 2:1 to CDK4/CDK6 inhibition with palbociclib plus fulvestrant (P+F) or placebo plus fulvestrant (F), and it showed that adding palbociclib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) (N Engl J Med. Jul 16 2015;373:209-19).

For the current analysis, the investigators assessed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in baseline plasma samples from 459 study participants in an effort to identify genomic biomarkers for progression, to examine the association between baseline tumor fraction and clinical outcome, and to explore differences in predictive markers by treatment arm. A custom amplicon-sequencing analysis was performed to look for mutations in 17 different relevant genes, and another was used to estimate tumor fraction by looking at about 800 common germline single-nucleotide polymorphisms and to assess copy-number gain in the amplification status in 11 different genes, Dr. O’Leary said.

Results for mutations and circulating nucleic acids were available in 203 and 107 patients from the P+F and F groups, respectively, and on multivariable analysis of all 310 patients (including palbociclib as a variable in the model and with ctDNA fraction as a continuous variable), higher baseline tumor purity in plasma was associated with highly significantly worse PFS (HR 1.2 per 10% increase in purity), and baseline TP53 mutation and FGFR1 amplification each were associated with significantly shorter PFS (HRs, 1.8 and 2.9, respectively).

“[It is] very important to note ... that we did look specifically for interaction between our genomic changes and treatment, and we didn’t find any evidence of a significant interaction, so these genomic markers [are] prognostic rather than predictive in terms of the two treatment arms of the trial,” he said.

A survival analysis showed a median PFS of 3.7 vs. 12.7 months in patients with vs. without TP53 mutation in the P+F arm, and 1.8 vs. 5.4 months, respectively, in the F arm, with similar HRs of 2.0 and 2.3 in the arms, respectively.

“Even in the [P+F] arm, you see almost half of the patients with a TP53 mutation ... have relapsed by 2 months, the earliest clinical assessment in the trial,” he noted.

For FGFR1, the PFS was 3.9 vs. 12 months with vs. without amplification in the P+F arms, and 1.8 vs. 5.8 months, respectively in th F arm, with HRs of 3.4 and 3.6, respectively.

These findings are notable because markers of early progression on endocrine therapy in combination with CDK4/6 inhibitors remain limited – despite the key role of these combinations in treating ER+ advanced breast cancer, Dr. O’Leary explained.

“Although many patients derive a great deal of benefit from these combinations, there are a subset of patients who will relapse relatively early, and ... we don’t have an established means of identifying those patients at the present,” he said. “From the technical perspective, liquid biopsies have emerged in recent years as a promising means of genotyping patients’ cancers from circulating tumor DNA, and in addition, the overall level of circulating tumor DNA – the fractional purity – has been associated with poor prognosis, specifically in the triple-negative breast cancer setting.”

The results, which require independent validation, could potentially inform future clinical trials of CDK4/6 inhibitor combinations in advanced ER+ breast cancer to identify a high-risk group of patients who require escalation of therapy, he concluded.

Dr. O’Leary reported receiving research funding from Pfizer to his institution.

SOURCE: O’Leary B et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 1010.

CHICAGO – Tumor protein 53 (TP53) mutation, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) amplification, and tumor purity in plasma each predict early progression on palbociclib and/or fulvestrant in patients with advanced estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) breast cancer, according to genomic analyses of PALOMA-3 trial data.

Overall, the presence of one or more of these genomic changes identified 131 out of 310 patients from the phase 3 trial who had baseline samples available, Ben O’Leary, MBBS, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“So, a significant minority of patients – 42.3% – potentially who fall into a more poor-prognosis group,” said Dr. O’Leary of the Institute of Cancer Research at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London.

The findings suggest that a “liquid biopsy” at the start of treatment could identify patients at risk for progression.

The PALOMA-3 trial randomized 521 patients with ER+, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative advanced breast cancer who had previously progressed on endocrine therapy 2:1 to CDK4/CDK6 inhibition with palbociclib plus fulvestrant (P+F) or placebo plus fulvestrant (F), and it showed that adding palbociclib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) (N Engl J Med. Jul 16 2015;373:209-19).

For the current analysis, the investigators assessed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in baseline plasma samples from 459 study participants in an effort to identify genomic biomarkers for progression, to examine the association between baseline tumor fraction and clinical outcome, and to explore differences in predictive markers by treatment arm. A custom amplicon-sequencing analysis was performed to look for mutations in 17 different relevant genes, and another was used to estimate tumor fraction by looking at about 800 common germline single-nucleotide polymorphisms and to assess copy-number gain in the amplification status in 11 different genes, Dr. O’Leary said.

Results for mutations and circulating nucleic acids were available in 203 and 107 patients from the P+F and F groups, respectively, and on multivariable analysis of all 310 patients (including palbociclib as a variable in the model and with ctDNA fraction as a continuous variable), higher baseline tumor purity in plasma was associated with highly significantly worse PFS (HR 1.2 per 10% increase in purity), and baseline TP53 mutation and FGFR1 amplification each were associated with significantly shorter PFS (HRs, 1.8 and 2.9, respectively).

“[It is] very important to note ... that we did look specifically for interaction between our genomic changes and treatment, and we didn’t find any evidence of a significant interaction, so these genomic markers [are] prognostic rather than predictive in terms of the two treatment arms of the trial,” he said.

A survival analysis showed a median PFS of 3.7 vs. 12.7 months in patients with vs. without TP53 mutation in the P+F arm, and 1.8 vs. 5.4 months, respectively, in the F arm, with similar HRs of 2.0 and 2.3 in the arms, respectively.

“Even in the [P+F] arm, you see almost half of the patients with a TP53 mutation ... have relapsed by 2 months, the earliest clinical assessment in the trial,” he noted.

For FGFR1, the PFS was 3.9 vs. 12 months with vs. without amplification in the P+F arms, and 1.8 vs. 5.8 months, respectively in th F arm, with HRs of 3.4 and 3.6, respectively.

These findings are notable because markers of early progression on endocrine therapy in combination with CDK4/6 inhibitors remain limited – despite the key role of these combinations in treating ER+ advanced breast cancer, Dr. O’Leary explained.

“Although many patients derive a great deal of benefit from these combinations, there are a subset of patients who will relapse relatively early, and ... we don’t have an established means of identifying those patients at the present,” he said. “From the technical perspective, liquid biopsies have emerged in recent years as a promising means of genotyping patients’ cancers from circulating tumor DNA, and in addition, the overall level of circulating tumor DNA – the fractional purity – has been associated with poor prognosis, specifically in the triple-negative breast cancer setting.”

The results, which require independent validation, could potentially inform future clinical trials of CDK4/6 inhibitor combinations in advanced ER+ breast cancer to identify a high-risk group of patients who require escalation of therapy, he concluded.

Dr. O’Leary reported receiving research funding from Pfizer to his institution.

SOURCE: O’Leary B et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 1010.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2019

Niraparib-pembrolizumab combo finds niche in breast, ovarian cancers

The strategy of simultaneously exploiting deficient DNA damage repair and unleashing the immune response could expand treatment options for hard-to-treat breast and ovarian cancers, findings of the TOPACIO/KEYNOTE-162 trial suggest.

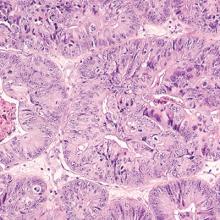

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma share a number of genomic features, including a high frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 inactivation (Nature. 2012;490:61-70), as well as potential immunoreactivity (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:40-50).

The open-label, single-arm phase 1/2 trial therefore tested the combination of niraparib (Zejula), an oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), an antibody to programmed death 1 (PD-1), among more than 100 patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC or recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma. Patients were enrolled irrespective of BRCA mutation status or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression.

Main results, reported in JAMA Oncology, showed that the combination was safe, and about a fifth of patients with each type of cancer had an objective response. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was about 2 months in those with TNBC overall (although it exceeded 8 months in the subset with a tumor BRCA mutation) and about 3 months in those with ovarian cancer.

TNBC cohort

Investigators led by Shaveta Vinayak, MD, of the division of oncology at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Seattle, studied 55 patients with TNBC treated with niraparib-pembrolizumab in the trial.

In the efficacy-evaluable population of 47 patients, the objective response rate (ORR) was 21%, and the disease control rate (DCR) was 49%. With a median duration of follow-up of 14.8 months, the median duration of response was not reached.

Activity of the combination varied by tumor BRCA mutation status. Compared with counterparts having BRCA wild-type tumors, patients having tumors with BRCA mutations had a numerically higher ORR (47% vs. 11%), DCR (80% vs. 33%), and PFS (8.3 vs. 2.1 months).

Some 18% of patients had treatment-related anemia, 15% thrombocytopenia, and 7% fatigue. In addition, 15% of patients had immune-related adverse events, with 4% having grade 3 immune-related adverse events.

“Combination niraparib plus pembrolizumab provides promising antitumor activity in patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC, with numerically higher response rates in those with tumor BRCA mutations,” Dr. Vinayak and colleagues conclude. “The combination therapy was safe with a tolerable safety profile, warranting further investigation.”

Ovarian cancer cohort

Investigators led by Panagiotis A. Konstantinopoulos, MD, PhD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, department of medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, studied 62 patients with ovarian carcinoma treated with niraparib-pembrolizumab in the trial.

In the efficacy-evaluable population of 60 patients, the ORR was 18% and the DCR was 65%. The ORRs were similar regardless of patients’ platinum-based chemotherapy sensitivity, previous bevacizumab treatment, or tumor BRCA or homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) biomarker status.

With a median duration of follow-up of 12.4 months, the median duration of response was not reached, ranging from 4.2 to roughly 14.5 months. Median progression-free survival was 3.4 months.

The leading treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or higher in this cohort were anemia (21%) and thrombocytopenia (9%). In addition, 19% of patients had immune-related adverse events, with 9% having grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events.

“Niraparib in combination with pembrolizumab is tolerable, with promising antitumor activity for patients with ovarian carcinoma who have limited treatment options regardless of platinum status, biomarker status, or prior treatment with bevacizumab,” Dr. Konstantinopoulos and colleagues conclude. “Responses in patients without tumor BRCA mutations or non-HRD cancers were higher than expected with either agent as monotherapy.”

Dr. Vinayak disclosed receiving clinical trial funding from TESARO; serving on an advisory board for TESARO; and serving on an advisory board for OncoSec Medical (uncompensated). Dr. Konstantinopoulos disclosed serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck. The trial was supported by TESARO: a GSK company and Merck, and in part by Stand Up to Cancer (a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation); the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Alliance; and National Ovarian Cancer Coalition Dream Team Translational Research.

SOURCE: Vinayak A et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1029. Konstantinopoulos PA et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1048.

“Targeting DNA repair and immune checkpoint pathways has emerged as an important concept in cancer therapy, well supported by preclinical and clinical data in ovarian cancer and TNBC. However, there are some limitations to the two studies presented herein,” maintain editorialists Kunle Odunsi, MD, PhD, and Tanja Pejovic, MD, PhD.

Patients varied considerably with respect to number of prior chemotherapy regimens, they elaborate. Also, there may have been some misclassification of patients into DNA damage repair (DDR) groups, and small sample sizes precluded rigorous subgroup analyses.

“Because DDR and, by extension, tumor mutational burden and PD-L1 status do not fully explain the effects of the combination of PARP inhibitors and anti–PD-1 therapy, additional predictive biomarkers based on tumor intrinsic or adaptive mechanisms of resistance are needed for both cancer types,” the editorialists contend. In particular, knowledge of the tumor microenvironment could be used to tailor therapy for individual patients.

“The TOPACIO clinical studies are clearly steps in the right direction for patients with [platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma] and TNBC,” they conclude. “However, larger confirmatory randomized clinical trials are needed that use panels of integrated biomarkers that would allow identification of patients most likely to respond.”

Dr. Odunsi is the deputy director and chair of the department of gynecologic oncology, executive director of the Center for Immunotherapy, and co-leader of the Tumor Immunology and Immunotherapy Research Program–Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y. Dr. Pejovic is associate professor, division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics & gynecology, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Ore. These remarks are adapted from a related editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1009 ).

“Targeting DNA repair and immune checkpoint pathways has emerged as an important concept in cancer therapy, well supported by preclinical and clinical data in ovarian cancer and TNBC. However, there are some limitations to the two studies presented herein,” maintain editorialists Kunle Odunsi, MD, PhD, and Tanja Pejovic, MD, PhD.

Patients varied considerably with respect to number of prior chemotherapy regimens, they elaborate. Also, there may have been some misclassification of patients into DNA damage repair (DDR) groups, and small sample sizes precluded rigorous subgroup analyses.

“Because DDR and, by extension, tumor mutational burden and PD-L1 status do not fully explain the effects of the combination of PARP inhibitors and anti–PD-1 therapy, additional predictive biomarkers based on tumor intrinsic or adaptive mechanisms of resistance are needed for both cancer types,” the editorialists contend. In particular, knowledge of the tumor microenvironment could be used to tailor therapy for individual patients.

“The TOPACIO clinical studies are clearly steps in the right direction for patients with [platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma] and TNBC,” they conclude. “However, larger confirmatory randomized clinical trials are needed that use panels of integrated biomarkers that would allow identification of patients most likely to respond.”

Dr. Odunsi is the deputy director and chair of the department of gynecologic oncology, executive director of the Center for Immunotherapy, and co-leader of the Tumor Immunology and Immunotherapy Research Program–Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y. Dr. Pejovic is associate professor, division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics & gynecology, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Ore. These remarks are adapted from a related editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1009 ).

“Targeting DNA repair and immune checkpoint pathways has emerged as an important concept in cancer therapy, well supported by preclinical and clinical data in ovarian cancer and TNBC. However, there are some limitations to the two studies presented herein,” maintain editorialists Kunle Odunsi, MD, PhD, and Tanja Pejovic, MD, PhD.

Patients varied considerably with respect to number of prior chemotherapy regimens, they elaborate. Also, there may have been some misclassification of patients into DNA damage repair (DDR) groups, and small sample sizes precluded rigorous subgroup analyses.

“Because DDR and, by extension, tumor mutational burden and PD-L1 status do not fully explain the effects of the combination of PARP inhibitors and anti–PD-1 therapy, additional predictive biomarkers based on tumor intrinsic or adaptive mechanisms of resistance are needed for both cancer types,” the editorialists contend. In particular, knowledge of the tumor microenvironment could be used to tailor therapy for individual patients.

“The TOPACIO clinical studies are clearly steps in the right direction for patients with [platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma] and TNBC,” they conclude. “However, larger confirmatory randomized clinical trials are needed that use panels of integrated biomarkers that would allow identification of patients most likely to respond.”

Dr. Odunsi is the deputy director and chair of the department of gynecologic oncology, executive director of the Center for Immunotherapy, and co-leader of the Tumor Immunology and Immunotherapy Research Program–Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y. Dr. Pejovic is associate professor, division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics & gynecology, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Ore. These remarks are adapted from a related editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1009 ).

The strategy of simultaneously exploiting deficient DNA damage repair and unleashing the immune response could expand treatment options for hard-to-treat breast and ovarian cancers, findings of the TOPACIO/KEYNOTE-162 trial suggest.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma share a number of genomic features, including a high frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 inactivation (Nature. 2012;490:61-70), as well as potential immunoreactivity (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:40-50).

The open-label, single-arm phase 1/2 trial therefore tested the combination of niraparib (Zejula), an oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), an antibody to programmed death 1 (PD-1), among more than 100 patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC or recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma. Patients were enrolled irrespective of BRCA mutation status or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression.

Main results, reported in JAMA Oncology, showed that the combination was safe, and about a fifth of patients with each type of cancer had an objective response. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was about 2 months in those with TNBC overall (although it exceeded 8 months in the subset with a tumor BRCA mutation) and about 3 months in those with ovarian cancer.

TNBC cohort

Investigators led by Shaveta Vinayak, MD, of the division of oncology at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Seattle, studied 55 patients with TNBC treated with niraparib-pembrolizumab in the trial.

In the efficacy-evaluable population of 47 patients, the objective response rate (ORR) was 21%, and the disease control rate (DCR) was 49%. With a median duration of follow-up of 14.8 months, the median duration of response was not reached.

Activity of the combination varied by tumor BRCA mutation status. Compared with counterparts having BRCA wild-type tumors, patients having tumors with BRCA mutations had a numerically higher ORR (47% vs. 11%), DCR (80% vs. 33%), and PFS (8.3 vs. 2.1 months).

Some 18% of patients had treatment-related anemia, 15% thrombocytopenia, and 7% fatigue. In addition, 15% of patients had immune-related adverse events, with 4% having grade 3 immune-related adverse events.

“Combination niraparib plus pembrolizumab provides promising antitumor activity in patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC, with numerically higher response rates in those with tumor BRCA mutations,” Dr. Vinayak and colleagues conclude. “The combination therapy was safe with a tolerable safety profile, warranting further investigation.”

Ovarian cancer cohort

Investigators led by Panagiotis A. Konstantinopoulos, MD, PhD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, department of medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, studied 62 patients with ovarian carcinoma treated with niraparib-pembrolizumab in the trial.

In the efficacy-evaluable population of 60 patients, the ORR was 18% and the DCR was 65%. The ORRs were similar regardless of patients’ platinum-based chemotherapy sensitivity, previous bevacizumab treatment, or tumor BRCA or homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) biomarker status.

With a median duration of follow-up of 12.4 months, the median duration of response was not reached, ranging from 4.2 to roughly 14.5 months. Median progression-free survival was 3.4 months.

The leading treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or higher in this cohort were anemia (21%) and thrombocytopenia (9%). In addition, 19% of patients had immune-related adverse events, with 9% having grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events.

“Niraparib in combination with pembrolizumab is tolerable, with promising antitumor activity for patients with ovarian carcinoma who have limited treatment options regardless of platinum status, biomarker status, or prior treatment with bevacizumab,” Dr. Konstantinopoulos and colleagues conclude. “Responses in patients without tumor BRCA mutations or non-HRD cancers were higher than expected with either agent as monotherapy.”

Dr. Vinayak disclosed receiving clinical trial funding from TESARO; serving on an advisory board for TESARO; and serving on an advisory board for OncoSec Medical (uncompensated). Dr. Konstantinopoulos disclosed serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck. The trial was supported by TESARO: a GSK company and Merck, and in part by Stand Up to Cancer (a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation); the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Alliance; and National Ovarian Cancer Coalition Dream Team Translational Research.

SOURCE: Vinayak A et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1029. Konstantinopoulos PA et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1048.

The strategy of simultaneously exploiting deficient DNA damage repair and unleashing the immune response could expand treatment options for hard-to-treat breast and ovarian cancers, findings of the TOPACIO/KEYNOTE-162 trial suggest.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma share a number of genomic features, including a high frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 inactivation (Nature. 2012;490:61-70), as well as potential immunoreactivity (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:40-50).

The open-label, single-arm phase 1/2 trial therefore tested the combination of niraparib (Zejula), an oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), an antibody to programmed death 1 (PD-1), among more than 100 patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC or recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma. Patients were enrolled irrespective of BRCA mutation status or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression.

Main results, reported in JAMA Oncology, showed that the combination was safe, and about a fifth of patients with each type of cancer had an objective response. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was about 2 months in those with TNBC overall (although it exceeded 8 months in the subset with a tumor BRCA mutation) and about 3 months in those with ovarian cancer.

TNBC cohort

Investigators led by Shaveta Vinayak, MD, of the division of oncology at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Seattle, studied 55 patients with TNBC treated with niraparib-pembrolizumab in the trial.

In the efficacy-evaluable population of 47 patients, the objective response rate (ORR) was 21%, and the disease control rate (DCR) was 49%. With a median duration of follow-up of 14.8 months, the median duration of response was not reached.

Activity of the combination varied by tumor BRCA mutation status. Compared with counterparts having BRCA wild-type tumors, patients having tumors with BRCA mutations had a numerically higher ORR (47% vs. 11%), DCR (80% vs. 33%), and PFS (8.3 vs. 2.1 months).

Some 18% of patients had treatment-related anemia, 15% thrombocytopenia, and 7% fatigue. In addition, 15% of patients had immune-related adverse events, with 4% having grade 3 immune-related adverse events.

“Combination niraparib plus pembrolizumab provides promising antitumor activity in patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC, with numerically higher response rates in those with tumor BRCA mutations,” Dr. Vinayak and colleagues conclude. “The combination therapy was safe with a tolerable safety profile, warranting further investigation.”

Ovarian cancer cohort

Investigators led by Panagiotis A. Konstantinopoulos, MD, PhD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, department of medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, studied 62 patients with ovarian carcinoma treated with niraparib-pembrolizumab in the trial.

In the efficacy-evaluable population of 60 patients, the ORR was 18% and the DCR was 65%. The ORRs were similar regardless of patients’ platinum-based chemotherapy sensitivity, previous bevacizumab treatment, or tumor BRCA or homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) biomarker status.

With a median duration of follow-up of 12.4 months, the median duration of response was not reached, ranging from 4.2 to roughly 14.5 months. Median progression-free survival was 3.4 months.

The leading treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or higher in this cohort were anemia (21%) and thrombocytopenia (9%). In addition, 19% of patients had immune-related adverse events, with 9% having grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events.

“Niraparib in combination with pembrolizumab is tolerable, with promising antitumor activity for patients with ovarian carcinoma who have limited treatment options regardless of platinum status, biomarker status, or prior treatment with bevacizumab,” Dr. Konstantinopoulos and colleagues conclude. “Responses in patients without tumor BRCA mutations or non-HRD cancers were higher than expected with either agent as monotherapy.”

Dr. Vinayak disclosed receiving clinical trial funding from TESARO; serving on an advisory board for TESARO; and serving on an advisory board for OncoSec Medical (uncompensated). Dr. Konstantinopoulos disclosed serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck. The trial was supported by TESARO: a GSK company and Merck, and in part by Stand Up to Cancer (a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation); the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Alliance; and National Ovarian Cancer Coalition Dream Team Translational Research.

SOURCE: Vinayak A et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1029. Konstantinopoulos PA et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1048.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

TAILORx: Clinical data add value to recurrence score

CHICAGO – , according to a secondary analysis of data from the practice-changing TAILORx study.

Specifically, tumor size and histology-based risk stratification improves the prediction of disease-free survival and distant recurrence, and – for some patient groups – chemotherapy benefit, Joseph A. Sparano, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Combining these tools could help determine whether endocrine therapy (ET) alone or ET with adjuvant chemotherapy is the best treatment approach for a given patient, said Dr. Sparano, professor of medicine and obstetrics, gynecology, and women’s health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

The phase 3 TAILORx study established that ET alone is noninferior to adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) plus ET in patients with early breast cancer and RS of 11-25, and that ET alone has some benefit over ET+CT in women aged 50 years and younger with RS of 16-25, he explained.

Those findings were presented at the 2018 ASCO annual meeting and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The current analysis focused on the integration of clinical and genomic features for prognosis, and the results were published online June 3 in a corresponding article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The totality of the data, including TAILORx and the prior prospective validation studies, indicate that assessment of genomic risk with the 21-gene recurrence score provides complementary prognostic information to pathologic features, and is also predictive of a large chemotherapy benefit if the recurrence score is greater than 25, or lack thereof if 25 or lower,” he said.

However, there is a three-way interaction between age, RS, and CT use, which results in an absolute CT benefit in women aged 50 or younger of about 2% for RS of 16-20, and about 7% for RS of 21-25, he added.

“Assessment of clinical risk using pathological features also provides prognostic information that doesn’t correlate well with the recurrence score, therefore it stands to reason that integration of clinical and genomic risk offers the potential for greater precision in prognosis and, ultimately, guiding the use of adjuvant therapy,” he said.

Clinical risk for this analysis was assessed using a binary clinical risk categorization employed in the MINDACT trial and calibrated to greater than 92% 10-year breast cancer-specific survival for ET alone based on Adjuvant! version 8.0. Low-grade tumors up to 3 cm, intermediate-grade tumors up to 2 cm, and high-grade tumors up to 1 cm were categorized as low clinical risk (LCR), and all others not meeting these criteria were categorized as high clinical risk (HCR), he explained.

Of 9,427 patients included in the analysis, 70% had LCR and 30% had HCR.

“For distant recurrence, high clinical risk was associated with a 2.5- to 3-fold higher recurrence rate for those with a recurrence score of 11 or higher, and in a multivariate model for distant recurrence in the [group with a] recurrence score of 11-25, high clinical risk was independently associated with a 2.4-fold higher recurrence risk,” he said. “Continuous recurrence score also provided significant prognostic information, with each 1-unit increase associated with an 8% higher distant recurrence risk.”

For the overall population, clinical risk added significant prognostic information to the RS for both distant recurrence and disease-free survival, and stratification by age showed that among women over age 50 years, the hazard ratios for distant recurrence ranged from 2.20 to 2.36, and did not substantially vary by age or RS, he said.

However, for the overall population, adding clinical risk to the RS did not improve prediction of chemotherapy benefit.

“This was also true for the two-thirds of women who were over 50 years of age. For the remaining women 50 or younger, there was a trend favoring chemo, irrespective of clinical risk, though not significant – a finding consistent with the treatment interaction previously described,” he said.

Finally, the absolute differences in 9-year distant recurrence rates by clinical risk stratified by age, RS, and CT use showed an absolute 4%-6% higher distant recurrence risk for HCR vs. LCR among those over age 50 with RS of 0-25 irrespective of CT use, and a 13% difference for those with RS of 26-100 who were treated with CT.

“For those 50 or younger, clinical risk had no impact on recurrence if the RS was 0-10. For RS of 11-25, the difference was about 9% with endocrine therapy alone, and 2% with chemo plus ET, reflecting absolute chemo benefit in younger women who had high clinical risk,” he said, adding that for those with RS of 26-100, there was a 9% higher absolute recurrence rate in the HCR vs. LCR population.

“We therefore further evaluated absolute differences in distance recurrence rates associated with chemotherapy use in women 50 and younger with RS of 16-25, further stratified by RS and clinical risk,” he said, noting that when not stratified by clinical risk, as reported in the primary analysis, the absolute CT benefit was 1.6% for RS of 16-20, and 6.5% for RS of 21-25.

When stratified by clinical risk, the absolute CT benefit ranged from 6% to 9% in those with RS of 21-25, irrespective of clinical risk, and in those with RS of 16-20 and HCR.

“This accounted for 51% of patients with RS of 16-25,” he said. “However, there was no demonstrable chemo benefit for those with LCR and RS of 16-20, who accounted for the remaining 49%.”

Additional analysis looking at age at diagnosis and CT benefit showed a benefit in premenopausal women aged 46-50 years (but not postmenopausal women), a trend toward benefit in those aged 41-45 years, and no benefit in those aged 40 years and younger, who are less likely to develop premature menopause as a consequence of cytotoxic CT.

“In addition, we saw no consistent effect favoring chemotherapy in older women. Taken together, these findings suggest the chemo benefit observed for the RS 16-25 group may, in fact, be due to a castration effect associated with cytotoxic therapy rather than an effect in eradicating micrometastatic disease,” Dr. Sparano said.

Applying this framework to the TAILORx study population categorized 68% of those aged 50 years and younger into a low integrated risk group with less than 5% risk of distant recurrence. This included all patients with RS of 0-10 irrespective of clinical risk (14% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 1.8% or less), and all with RS of 11-25 and LCR (54% of the patient population, 4.7% distant recurrence rate).

In contrast, 25% fell into the high integrated risk group (greater than 10% distant recurrence risk), including those with RS of 11-25 and HCR (17% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 12.3%), and RS of 26-100 and HCR (8% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 15.2%).

“This framework encompasses 93% of all TAILORx subjects, with the remaining 7% having a distant recurrence risk of between 5% and 10%,” he said.

Overall, the primary results of TAILORx remain unchanged based on this secondary analysis as the addition of clinical risk did not predict CT benefit in the RS 11-25 group, he noted.

“However, for women 50 and under and RS 16-25, integrated risk distinguished 50% who derived no chemo benefit from the 50% who derived an absolute benefit of approximately 6%-9% – a level that is higher than an unselected population,” he said, reiterating that the absolute CT benefit was greater in premenopausal women aged 45-50 with RS 16-25, suggesting that the absolute CR benefit seen in younger women in TAILORx may be due to an endocrine effect.

“Integrated risk clearly provides greater prognostic precision and may have clinical utility; the prognostic precision afforded by the integrated risk model is superior to that by the use of clinical or genomic features alone, and in addition, the genomic assay also provides predictive information for chemo benefit that is not captured by clinical features alone,” he concluded.

As an example of the potential clinical utility of this integrated approach for guiding treatment in women aged 50 years or younger, he presented “a highly stratified integrated risk assessment model” separating TAILORx patients into low integrated risk (58% of the study population) and high integrated risk (31% of the study population).

In the low integrated risk patients with RS of 0-10 and any clinical risk level, or with RS of 11-25 and LCR, tamoxifen alone appears adequate, he said.

In those with high integrated risk and RS of 16-25 with HCR, ovarian function suppression plus an aromatase inhibitor (OFS/AI) could be considered as an alternative to chemo, and in those with high integrated risk, RS of 26-100, and HCR who have not developed chemotherapy-induced menopause, ovarian function suppression and an AI could be added to chemotherapy.

“Indeed, data from the SOFT and TEXT trials indicate that patients with a high RS risk experienced an absolute improvement of up to 10%-15% in 5-year breast cancer–free interval with an OFS/AI, compared with tamoxifen, whereas improvement was minimal in those at lowest risk, supporting the strategy of using integrated clinical and genomic risk to select for ovarian function suppression plus an AI,” he said.

During a discussion of the findings and how they might impact practice, Vered Stearns, MD, an oncology professor and codirector of the Breast Cancer Program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that in her practice she will “carefully select women for whom genomic assay [use] is appropriate.

“I will also assess clinical risk and RS to inform recommendations for chemotherapy use, and possibly appropriate endocrine agents in select populations,” she said.

Dr. Stearns further noted that the interaction between RS and age as reported by Dr. Sparano is exploratory and should be interpreted with caution as the majority of those aged 50 and younger received tamoxifen alone and the question remains as to whether they would have received similar benefits from ovarian suppression and tamoxifen/AI instead of chemo-endocrine therapy.

“Indeed, indirect hypotheses from other studies suggest that may be the case,” she said, adding that these women may be offered ovarian suppression and tamoxifen or AI based on the SOFT and TEXT results.

“TAILORx remains a rich resource for new explorations, new biomarkers, new models, and new machine learning opportunities,” she said.

TAILORx was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sparano reported stock ownership, a consulting role, and research funding from several pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Stearns reported consulting or advisory roles with Iridium Therapeutics; research funding from Abbvie, Biocept, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, and Puma Biotechnology; and an “other relationship” with Immunomedics.

SOURCE: Sparano JA et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 503.

CHICAGO – , according to a secondary analysis of data from the practice-changing TAILORx study.

Specifically, tumor size and histology-based risk stratification improves the prediction of disease-free survival and distant recurrence, and – for some patient groups – chemotherapy benefit, Joseph A. Sparano, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Combining these tools could help determine whether endocrine therapy (ET) alone or ET with adjuvant chemotherapy is the best treatment approach for a given patient, said Dr. Sparano, professor of medicine and obstetrics, gynecology, and women’s health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

The phase 3 TAILORx study established that ET alone is noninferior to adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) plus ET in patients with early breast cancer and RS of 11-25, and that ET alone has some benefit over ET+CT in women aged 50 years and younger with RS of 16-25, he explained.

Those findings were presented at the 2018 ASCO annual meeting and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The current analysis focused on the integration of clinical and genomic features for prognosis, and the results were published online June 3 in a corresponding article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The totality of the data, including TAILORx and the prior prospective validation studies, indicate that assessment of genomic risk with the 21-gene recurrence score provides complementary prognostic information to pathologic features, and is also predictive of a large chemotherapy benefit if the recurrence score is greater than 25, or lack thereof if 25 or lower,” he said.

However, there is a three-way interaction between age, RS, and CT use, which results in an absolute CT benefit in women aged 50 or younger of about 2% for RS of 16-20, and about 7% for RS of 21-25, he added.

“Assessment of clinical risk using pathological features also provides prognostic information that doesn’t correlate well with the recurrence score, therefore it stands to reason that integration of clinical and genomic risk offers the potential for greater precision in prognosis and, ultimately, guiding the use of adjuvant therapy,” he said.

Clinical risk for this analysis was assessed using a binary clinical risk categorization employed in the MINDACT trial and calibrated to greater than 92% 10-year breast cancer-specific survival for ET alone based on Adjuvant! version 8.0. Low-grade tumors up to 3 cm, intermediate-grade tumors up to 2 cm, and high-grade tumors up to 1 cm were categorized as low clinical risk (LCR), and all others not meeting these criteria were categorized as high clinical risk (HCR), he explained.

Of 9,427 patients included in the analysis, 70% had LCR and 30% had HCR.

“For distant recurrence, high clinical risk was associated with a 2.5- to 3-fold higher recurrence rate for those with a recurrence score of 11 or higher, and in a multivariate model for distant recurrence in the [group with a] recurrence score of 11-25, high clinical risk was independently associated with a 2.4-fold higher recurrence risk,” he said. “Continuous recurrence score also provided significant prognostic information, with each 1-unit increase associated with an 8% higher distant recurrence risk.”

For the overall population, clinical risk added significant prognostic information to the RS for both distant recurrence and disease-free survival, and stratification by age showed that among women over age 50 years, the hazard ratios for distant recurrence ranged from 2.20 to 2.36, and did not substantially vary by age or RS, he said.

However, for the overall population, adding clinical risk to the RS did not improve prediction of chemotherapy benefit.

“This was also true for the two-thirds of women who were over 50 years of age. For the remaining women 50 or younger, there was a trend favoring chemo, irrespective of clinical risk, though not significant – a finding consistent with the treatment interaction previously described,” he said.

Finally, the absolute differences in 9-year distant recurrence rates by clinical risk stratified by age, RS, and CT use showed an absolute 4%-6% higher distant recurrence risk for HCR vs. LCR among those over age 50 with RS of 0-25 irrespective of CT use, and a 13% difference for those with RS of 26-100 who were treated with CT.

“For those 50 or younger, clinical risk had no impact on recurrence if the RS was 0-10. For RS of 11-25, the difference was about 9% with endocrine therapy alone, and 2% with chemo plus ET, reflecting absolute chemo benefit in younger women who had high clinical risk,” he said, adding that for those with RS of 26-100, there was a 9% higher absolute recurrence rate in the HCR vs. LCR population.

“We therefore further evaluated absolute differences in distance recurrence rates associated with chemotherapy use in women 50 and younger with RS of 16-25, further stratified by RS and clinical risk,” he said, noting that when not stratified by clinical risk, as reported in the primary analysis, the absolute CT benefit was 1.6% for RS of 16-20, and 6.5% for RS of 21-25.

When stratified by clinical risk, the absolute CT benefit ranged from 6% to 9% in those with RS of 21-25, irrespective of clinical risk, and in those with RS of 16-20 and HCR.

“This accounted for 51% of patients with RS of 16-25,” he said. “However, there was no demonstrable chemo benefit for those with LCR and RS of 16-20, who accounted for the remaining 49%.”

Additional analysis looking at age at diagnosis and CT benefit showed a benefit in premenopausal women aged 46-50 years (but not postmenopausal women), a trend toward benefit in those aged 41-45 years, and no benefit in those aged 40 years and younger, who are less likely to develop premature menopause as a consequence of cytotoxic CT.

“In addition, we saw no consistent effect favoring chemotherapy in older women. Taken together, these findings suggest the chemo benefit observed for the RS 16-25 group may, in fact, be due to a castration effect associated with cytotoxic therapy rather than an effect in eradicating micrometastatic disease,” Dr. Sparano said.

Applying this framework to the TAILORx study population categorized 68% of those aged 50 years and younger into a low integrated risk group with less than 5% risk of distant recurrence. This included all patients with RS of 0-10 irrespective of clinical risk (14% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 1.8% or less), and all with RS of 11-25 and LCR (54% of the patient population, 4.7% distant recurrence rate).

In contrast, 25% fell into the high integrated risk group (greater than 10% distant recurrence risk), including those with RS of 11-25 and HCR (17% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 12.3%), and RS of 26-100 and HCR (8% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 15.2%).

“This framework encompasses 93% of all TAILORx subjects, with the remaining 7% having a distant recurrence risk of between 5% and 10%,” he said.

Overall, the primary results of TAILORx remain unchanged based on this secondary analysis as the addition of clinical risk did not predict CT benefit in the RS 11-25 group, he noted.

“However, for women 50 and under and RS 16-25, integrated risk distinguished 50% who derived no chemo benefit from the 50% who derived an absolute benefit of approximately 6%-9% – a level that is higher than an unselected population,” he said, reiterating that the absolute CT benefit was greater in premenopausal women aged 45-50 with RS 16-25, suggesting that the absolute CR benefit seen in younger women in TAILORx may be due to an endocrine effect.

“Integrated risk clearly provides greater prognostic precision and may have clinical utility; the prognostic precision afforded by the integrated risk model is superior to that by the use of clinical or genomic features alone, and in addition, the genomic assay also provides predictive information for chemo benefit that is not captured by clinical features alone,” he concluded.

As an example of the potential clinical utility of this integrated approach for guiding treatment in women aged 50 years or younger, he presented “a highly stratified integrated risk assessment model” separating TAILORx patients into low integrated risk (58% of the study population) and high integrated risk (31% of the study population).

In the low integrated risk patients with RS of 0-10 and any clinical risk level, or with RS of 11-25 and LCR, tamoxifen alone appears adequate, he said.

In those with high integrated risk and RS of 16-25 with HCR, ovarian function suppression plus an aromatase inhibitor (OFS/AI) could be considered as an alternative to chemo, and in those with high integrated risk, RS of 26-100, and HCR who have not developed chemotherapy-induced menopause, ovarian function suppression and an AI could be added to chemotherapy.

“Indeed, data from the SOFT and TEXT trials indicate that patients with a high RS risk experienced an absolute improvement of up to 10%-15% in 5-year breast cancer–free interval with an OFS/AI, compared with tamoxifen, whereas improvement was minimal in those at lowest risk, supporting the strategy of using integrated clinical and genomic risk to select for ovarian function suppression plus an AI,” he said.

During a discussion of the findings and how they might impact practice, Vered Stearns, MD, an oncology professor and codirector of the Breast Cancer Program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that in her practice she will “carefully select women for whom genomic assay [use] is appropriate.

“I will also assess clinical risk and RS to inform recommendations for chemotherapy use, and possibly appropriate endocrine agents in select populations,” she said.

Dr. Stearns further noted that the interaction between RS and age as reported by Dr. Sparano is exploratory and should be interpreted with caution as the majority of those aged 50 and younger received tamoxifen alone and the question remains as to whether they would have received similar benefits from ovarian suppression and tamoxifen/AI instead of chemo-endocrine therapy.

“Indeed, indirect hypotheses from other studies suggest that may be the case,” she said, adding that these women may be offered ovarian suppression and tamoxifen or AI based on the SOFT and TEXT results.

“TAILORx remains a rich resource for new explorations, new biomarkers, new models, and new machine learning opportunities,” she said.

TAILORx was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sparano reported stock ownership, a consulting role, and research funding from several pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Stearns reported consulting or advisory roles with Iridium Therapeutics; research funding from Abbvie, Biocept, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, and Puma Biotechnology; and an “other relationship” with Immunomedics.

SOURCE: Sparano JA et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 503.

CHICAGO – , according to a secondary analysis of data from the practice-changing TAILORx study.

Specifically, tumor size and histology-based risk stratification improves the prediction of disease-free survival and distant recurrence, and – for some patient groups – chemotherapy benefit, Joseph A. Sparano, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Combining these tools could help determine whether endocrine therapy (ET) alone or ET with adjuvant chemotherapy is the best treatment approach for a given patient, said Dr. Sparano, professor of medicine and obstetrics, gynecology, and women’s health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

The phase 3 TAILORx study established that ET alone is noninferior to adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) plus ET in patients with early breast cancer and RS of 11-25, and that ET alone has some benefit over ET+CT in women aged 50 years and younger with RS of 16-25, he explained.

Those findings were presented at the 2018 ASCO annual meeting and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The current analysis focused on the integration of clinical and genomic features for prognosis, and the results were published online June 3 in a corresponding article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The totality of the data, including TAILORx and the prior prospective validation studies, indicate that assessment of genomic risk with the 21-gene recurrence score provides complementary prognostic information to pathologic features, and is also predictive of a large chemotherapy benefit if the recurrence score is greater than 25, or lack thereof if 25 or lower,” he said.

However, there is a three-way interaction between age, RS, and CT use, which results in an absolute CT benefit in women aged 50 or younger of about 2% for RS of 16-20, and about 7% for RS of 21-25, he added.

“Assessment of clinical risk using pathological features also provides prognostic information that doesn’t correlate well with the recurrence score, therefore it stands to reason that integration of clinical and genomic risk offers the potential for greater precision in prognosis and, ultimately, guiding the use of adjuvant therapy,” he said.

Clinical risk for this analysis was assessed using a binary clinical risk categorization employed in the MINDACT trial and calibrated to greater than 92% 10-year breast cancer-specific survival for ET alone based on Adjuvant! version 8.0. Low-grade tumors up to 3 cm, intermediate-grade tumors up to 2 cm, and high-grade tumors up to 1 cm were categorized as low clinical risk (LCR), and all others not meeting these criteria were categorized as high clinical risk (HCR), he explained.

Of 9,427 patients included in the analysis, 70% had LCR and 30% had HCR.

“For distant recurrence, high clinical risk was associated with a 2.5- to 3-fold higher recurrence rate for those with a recurrence score of 11 or higher, and in a multivariate model for distant recurrence in the [group with a] recurrence score of 11-25, high clinical risk was independently associated with a 2.4-fold higher recurrence risk,” he said. “Continuous recurrence score also provided significant prognostic information, with each 1-unit increase associated with an 8% higher distant recurrence risk.”

For the overall population, clinical risk added significant prognostic information to the RS for both distant recurrence and disease-free survival, and stratification by age showed that among women over age 50 years, the hazard ratios for distant recurrence ranged from 2.20 to 2.36, and did not substantially vary by age or RS, he said.

However, for the overall population, adding clinical risk to the RS did not improve prediction of chemotherapy benefit.

“This was also true for the two-thirds of women who were over 50 years of age. For the remaining women 50 or younger, there was a trend favoring chemo, irrespective of clinical risk, though not significant – a finding consistent with the treatment interaction previously described,” he said.

Finally, the absolute differences in 9-year distant recurrence rates by clinical risk stratified by age, RS, and CT use showed an absolute 4%-6% higher distant recurrence risk for HCR vs. LCR among those over age 50 with RS of 0-25 irrespective of CT use, and a 13% difference for those with RS of 26-100 who were treated with CT.

“For those 50 or younger, clinical risk had no impact on recurrence if the RS was 0-10. For RS of 11-25, the difference was about 9% with endocrine therapy alone, and 2% with chemo plus ET, reflecting absolute chemo benefit in younger women who had high clinical risk,” he said, adding that for those with RS of 26-100, there was a 9% higher absolute recurrence rate in the HCR vs. LCR population.

“We therefore further evaluated absolute differences in distance recurrence rates associated with chemotherapy use in women 50 and younger with RS of 16-25, further stratified by RS and clinical risk,” he said, noting that when not stratified by clinical risk, as reported in the primary analysis, the absolute CT benefit was 1.6% for RS of 16-20, and 6.5% for RS of 21-25.

When stratified by clinical risk, the absolute CT benefit ranged from 6% to 9% in those with RS of 21-25, irrespective of clinical risk, and in those with RS of 16-20 and HCR.

“This accounted for 51% of patients with RS of 16-25,” he said. “However, there was no demonstrable chemo benefit for those with LCR and RS of 16-20, who accounted for the remaining 49%.”

Additional analysis looking at age at diagnosis and CT benefit showed a benefit in premenopausal women aged 46-50 years (but not postmenopausal women), a trend toward benefit in those aged 41-45 years, and no benefit in those aged 40 years and younger, who are less likely to develop premature menopause as a consequence of cytotoxic CT.

“In addition, we saw no consistent effect favoring chemotherapy in older women. Taken together, these findings suggest the chemo benefit observed for the RS 16-25 group may, in fact, be due to a castration effect associated with cytotoxic therapy rather than an effect in eradicating micrometastatic disease,” Dr. Sparano said.

Applying this framework to the TAILORx study population categorized 68% of those aged 50 years and younger into a low integrated risk group with less than 5% risk of distant recurrence. This included all patients with RS of 0-10 irrespective of clinical risk (14% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 1.8% or less), and all with RS of 11-25 and LCR (54% of the patient population, 4.7% distant recurrence rate).

In contrast, 25% fell into the high integrated risk group (greater than 10% distant recurrence risk), including those with RS of 11-25 and HCR (17% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 12.3%), and RS of 26-100 and HCR (8% of the patient population; distant recurrence rate 15.2%).

“This framework encompasses 93% of all TAILORx subjects, with the remaining 7% having a distant recurrence risk of between 5% and 10%,” he said.

Overall, the primary results of TAILORx remain unchanged based on this secondary analysis as the addition of clinical risk did not predict CT benefit in the RS 11-25 group, he noted.

“However, for women 50 and under and RS 16-25, integrated risk distinguished 50% who derived no chemo benefit from the 50% who derived an absolute benefit of approximately 6%-9% – a level that is higher than an unselected population,” he said, reiterating that the absolute CT benefit was greater in premenopausal women aged 45-50 with RS 16-25, suggesting that the absolute CR benefit seen in younger women in TAILORx may be due to an endocrine effect.

“Integrated risk clearly provides greater prognostic precision and may have clinical utility; the prognostic precision afforded by the integrated risk model is superior to that by the use of clinical or genomic features alone, and in addition, the genomic assay also provides predictive information for chemo benefit that is not captured by clinical features alone,” he concluded.

As an example of the potential clinical utility of this integrated approach for guiding treatment in women aged 50 years or younger, he presented “a highly stratified integrated risk assessment model” separating TAILORx patients into low integrated risk (58% of the study population) and high integrated risk (31% of the study population).

In the low integrated risk patients with RS of 0-10 and any clinical risk level, or with RS of 11-25 and LCR, tamoxifen alone appears adequate, he said.

In those with high integrated risk and RS of 16-25 with HCR, ovarian function suppression plus an aromatase inhibitor (OFS/AI) could be considered as an alternative to chemo, and in those with high integrated risk, RS of 26-100, and HCR who have not developed chemotherapy-induced menopause, ovarian function suppression and an AI could be added to chemotherapy.

“Indeed, data from the SOFT and TEXT trials indicate that patients with a high RS risk experienced an absolute improvement of up to 10%-15% in 5-year breast cancer–free interval with an OFS/AI, compared with tamoxifen, whereas improvement was minimal in those at lowest risk, supporting the strategy of using integrated clinical and genomic risk to select for ovarian function suppression plus an AI,” he said.

During a discussion of the findings and how they might impact practice, Vered Stearns, MD, an oncology professor and codirector of the Breast Cancer Program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that in her practice she will “carefully select women for whom genomic assay [use] is appropriate.

“I will also assess clinical risk and RS to inform recommendations for chemotherapy use, and possibly appropriate endocrine agents in select populations,” she said.

Dr. Stearns further noted that the interaction between RS and age as reported by Dr. Sparano is exploratory and should be interpreted with caution as the majority of those aged 50 and younger received tamoxifen alone and the question remains as to whether they would have received similar benefits from ovarian suppression and tamoxifen/AI instead of chemo-endocrine therapy.

“Indeed, indirect hypotheses from other studies suggest that may be the case,” she said, adding that these women may be offered ovarian suppression and tamoxifen or AI based on the SOFT and TEXT results.

“TAILORx remains a rich resource for new explorations, new biomarkers, new models, and new machine learning opportunities,” she said.

TAILORx was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sparano reported stock ownership, a consulting role, and research funding from several pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Stearns reported consulting or advisory roles with Iridium Therapeutics; research funding from Abbvie, Biocept, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, and Puma Biotechnology; and an “other relationship” with Immunomedics.

SOURCE: Sparano JA et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 503.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2019

FDA approves trastuzumab-anns for HER2-positive breast, gastric cancer

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Amgen’s trastuzumab-anns as a trastuzumab biosimilar for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer and gastric cancer.

This biosimilar, to be marketed as Kanjinti, is the fifth trastuzumab biosimilar to be approved by the agency, according to the FDA.

Approval was based in part on the LILAC study, which demonstrated that the biosimilar, previously called ABP-980, had similar efficacy and comparable cardiac safety with trastuzumab.

In the phase 3 study, 725 patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer were randomized to neoadjuvant treatment with trastuzumab-anns or trastuzumab, plus paclitaxel, for four cycles following four cycles of chemotherapy. The primary pathological complete response endpoint was achieved in 48% of those in the biosimilar arm, compared with 40.5% in the trastuzumab arm. Patients then went on to receive adjuvant treatment with ABP 980 or trastuzumab every 3 weeks for up to 1 year following surgery.

Grade 3 or worse adverse events during the neoadjuvant phase occurred in 15% of patients in the ABP 980 group and 14% in the trastuzumab group. The most frequent grade 3 event in both study arms was neutropenia. In the adjuvant phase, grade 3 or worse adverse events occurred in 9% of those continuing ABP 980 and in 6% of those continuing trastuzumab. The most frequent events in both arms were infections, infestations, and neutropenia.

Trastuzumab-anns is indicated for adjuvant treatment of HER2-overexpressing node positive or node negative breast cancer, first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer, and first-line treatment of patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. The FDA indicates patients should be selected based on an FDA-approved companion diagnostic for a trastuzumab product.

The biosimilar includes a boxed warning for cardiomyopathy, infusion reactions, embryo-fetal toxicity, and pulmonary toxicity.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Amgen’s trastuzumab-anns as a trastuzumab biosimilar for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer and gastric cancer.

This biosimilar, to be marketed as Kanjinti, is the fifth trastuzumab biosimilar to be approved by the agency, according to the FDA.

Approval was based in part on the LILAC study, which demonstrated that the biosimilar, previously called ABP-980, had similar efficacy and comparable cardiac safety with trastuzumab.