User login

FDA approves first dedicated bifurcation device to treat coronary bifurcation lesions

Tryton Medical announced on March 6 that the Food and Drug Administration has approved Tryton Side Branch Stent for the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions involving large side branches, becoming the first dedicated bifurcation device to receive regulatory approval in the U.S.

In a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial, treatment with the Tryton Side Branch Stent in the intended population of patients with large side branches (stent greater than 2.5mm) reduced the need for additional bailout stenting (0.7% vs. 5.6%, P = .02). It led to significantly lower side branch percent diameter stenosis at a 9-month follow-up (30.4% vs. 40.6%, P = .004) when compared with provisional stenting. The analysis also showed comparable major adverse cardiovascular events and myocardial infarction rates when compared with provisional stenting at 3 years.

“Treatment of complex lesions at the site of a bifurcation has historically been inconsistent, with results varying depending on the procedure and the experience of the interventionist,” said Aaron Kaplan, MD, Professor of Medicine at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and Chief Medical Officer of Tryton Medical, in a press release. “A predictable bifurcation solution helps alleviate some of the stress in these procedures by limiting variability and reducing the need for bailout stenting. This important FDA decision could have a profound impact on treatment protocols and guidelines for significant bifurcation lesions in the years ahead.”

There have been no randomized studies to compare the results of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with coronary artery bypass grafting in a bifurcation-only patient population. But this new device should benefit results from treatment using PCI.

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. in both men and women, and often results in bifurcation. Provisional stenting of the main branch is the current standard of care, but in many cases the side branch is not stented, leaving it vulnerable to complications like occlusion requiring bailout stenting.

Read more on Tryton Side Branch Stent on Tryton’s website.

Tryton Medical announced on March 6 that the Food and Drug Administration has approved Tryton Side Branch Stent for the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions involving large side branches, becoming the first dedicated bifurcation device to receive regulatory approval in the U.S.

In a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial, treatment with the Tryton Side Branch Stent in the intended population of patients with large side branches (stent greater than 2.5mm) reduced the need for additional bailout stenting (0.7% vs. 5.6%, P = .02). It led to significantly lower side branch percent diameter stenosis at a 9-month follow-up (30.4% vs. 40.6%, P = .004) when compared with provisional stenting. The analysis also showed comparable major adverse cardiovascular events and myocardial infarction rates when compared with provisional stenting at 3 years.

“Treatment of complex lesions at the site of a bifurcation has historically been inconsistent, with results varying depending on the procedure and the experience of the interventionist,” said Aaron Kaplan, MD, Professor of Medicine at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and Chief Medical Officer of Tryton Medical, in a press release. “A predictable bifurcation solution helps alleviate some of the stress in these procedures by limiting variability and reducing the need for bailout stenting. This important FDA decision could have a profound impact on treatment protocols and guidelines for significant bifurcation lesions in the years ahead.”

There have been no randomized studies to compare the results of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with coronary artery bypass grafting in a bifurcation-only patient population. But this new device should benefit results from treatment using PCI.

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. in both men and women, and often results in bifurcation. Provisional stenting of the main branch is the current standard of care, but in many cases the side branch is not stented, leaving it vulnerable to complications like occlusion requiring bailout stenting.

Read more on Tryton Side Branch Stent on Tryton’s website.

Tryton Medical announced on March 6 that the Food and Drug Administration has approved Tryton Side Branch Stent for the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions involving large side branches, becoming the first dedicated bifurcation device to receive regulatory approval in the U.S.

In a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial, treatment with the Tryton Side Branch Stent in the intended population of patients with large side branches (stent greater than 2.5mm) reduced the need for additional bailout stenting (0.7% vs. 5.6%, P = .02). It led to significantly lower side branch percent diameter stenosis at a 9-month follow-up (30.4% vs. 40.6%, P = .004) when compared with provisional stenting. The analysis also showed comparable major adverse cardiovascular events and myocardial infarction rates when compared with provisional stenting at 3 years.

“Treatment of complex lesions at the site of a bifurcation has historically been inconsistent, with results varying depending on the procedure and the experience of the interventionist,” said Aaron Kaplan, MD, Professor of Medicine at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and Chief Medical Officer of Tryton Medical, in a press release. “A predictable bifurcation solution helps alleviate some of the stress in these procedures by limiting variability and reducing the need for bailout stenting. This important FDA decision could have a profound impact on treatment protocols and guidelines for significant bifurcation lesions in the years ahead.”

There have been no randomized studies to compare the results of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with coronary artery bypass grafting in a bifurcation-only patient population. But this new device should benefit results from treatment using PCI.

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. in both men and women, and often results in bifurcation. Provisional stenting of the main branch is the current standard of care, but in many cases the side branch is not stented, leaving it vulnerable to complications like occlusion requiring bailout stenting.

Read more on Tryton Side Branch Stent on Tryton’s website.

The percutaneous mitral valve replacement pipe dream

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Percutaneous mitral valve replacement is unlikely to ever catch on in any way remotely approaching that of transcatheter aortic valve replacement for the treatment of aortic stenosis, Blase A. Carabello, MD, predicted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We’ve spent $2 billion looking for methods of percutaneous mitral valve replacement, and yet, I have to wonder if that makes any sense,” said Dr. Carabello, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C.

“If repair is superior to replacement in primary MR [mitral regurgitation], which I think we all agree is true, and you don’t need to get rid of every last molecule of blood going backward across the mitral valve when you’ve got a good left ventricle, then a percutaneous replacement in primary MR would have only the niche of patients who are inoperable and whose leaflets can’t be grabbed by the MitraClip or some new percutaneous device down the road. And, in secondary MR, it doesn’t seem to matter whether you replace or repair the valve, so why not just repair it with a clip?” he argued.

Numerous nonrandomized studies have invariably demonstrated superior survival for surgical repair versus replacement in patients with primary MR.

“There’s never going to be a randomized controlled trial of repair versus replacement; there’s no equipoise there. We all believe that, in primary MR, repair is superior to replacement. There are no data anywhere to suggest the opposite. It’s essentially sacrosanct,” according to the cardiologist.

In contrast, a major randomized trial of surgical repair versus replacement has been conducted in patients with severe secondary MR. This NIH-funded study conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network found no difference in survival between the two groups (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 28; 374[4]:344-53). That’s not a surprising result, Dr. Carabello said, since the underlying cause of this type of valve disease is a sick left ventricle. But, since surgical repair entails less morbidity than replacement – and a percutaneous repair with a leaflet-grasping device such as the MitraClip is simpler and safer than a surgical repair – it seems likely that the future treatment for secondary MR will be a percutaneous device, he said.

That future could depend upon the results of the ongoing COAPT trial (Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy), in which the MitraClip is being studied as an alternative to surgical repair for significant secondary MR. The MitraClip, which doesn’t entail a concomitant annuloplasty, is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration only for patients with primary, degenerative mitral regurgitation not amenable to surgical repair. But, if COAPT yields positive results, the role of the MitraClip will greatly expand.

An intriguing and poorly understood difference exists in the significance of residual mitral regurgitation following surgical repair as opposed to percutaneous MitraClip repair, Dr. Carabello observed.

“I go to the OR a lot, and I know of no surgeon [who] will leave 2+ MR behind. Most surgeons won’t leave 1+ MR behind. They’ll put the patient back on the pump to repair even mild residual MR, accepting only trace MR or zero before they leave the OR because they know that the best predictor of a failed mitral repair is the presence of residual MR in the OR,” he said.

In contrast, following successful deployment of the MitraClip most patients are left with 1-2+ MR. Yet, as was demonstrated in the 5-year results of the randomized EVEREST II trial (Endovascular Valve Edge-to-Edge Repair Study), this residual MR wasn’t a harbinger of poor outcomes long-term (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 29;66[25]:2844-54).

“You would have expected, with that much residual MR, there would be a perpetually increasing failure rate over time, but that didn’t happen. In Everest II, there was an early failure rate for percutaneous repair, where the MitraClip didn’t work and those patients required surgical mitral valve repair. But, after the first 6 months, the failure rate for the clip was exactly the same as the surgical failure rate, even though, with the clip, you start with more MR to begin with,” the cardiologist noted.

The MitraClip procedure is modeled after the surgical Alfieri double-orifice end-to-end stitch technique, which has been shown to have durable results when performed in conjunction with an annuloplasty ring for primary MR.

“The MitraClip essentially joins the valve in the middle the way the Alfieri stitch does, but it doesn’t appear to behave the same way. Why is that? Maybe the clip does something different than the Alfieri stitch on which it was modeled. Maybe that bar in the middle of the mitral valve does something in terms of scarring or stabilization that we don’t know about yet,” he speculated.

As for the prospects for percutaneous mitral valve replacement, Dr. Carabello said that this type of procedure “is a very difficult thing to do, and so far, has been met with a fair amount of failure. It’ll be very interesting to see what percentage of market share it gets 10 years down the road. My prediction is that, for mitral regurgitation, repair is always going to be it.”

Dr. Carabello reported serving on a data safety monitoring board for Edwards Lifesciences.

The author provides valuable insight into how the definition of “success” of a procedure can change depending on the approach to the problem. While the gold standard of open mitral valve repair is 1+ regurgitation or less, those promoting percutaneous valve replacement are willing to accept long term 1+ to 2+ regurgitation. New technology and innovation is critical in medicine, provided the results are at least equivalent or superior to the standard techniques.

The author provides valuable insight into how the definition of “success” of a procedure can change depending on the approach to the problem. While the gold standard of open mitral valve repair is 1+ regurgitation or less, those promoting percutaneous valve replacement are willing to accept long term 1+ to 2+ regurgitation. New technology and innovation is critical in medicine, provided the results are at least equivalent or superior to the standard techniques.

The author provides valuable insight into how the definition of “success” of a procedure can change depending on the approach to the problem. While the gold standard of open mitral valve repair is 1+ regurgitation or less, those promoting percutaneous valve replacement are willing to accept long term 1+ to 2+ regurgitation. New technology and innovation is critical in medicine, provided the results are at least equivalent or superior to the standard techniques.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Percutaneous mitral valve replacement is unlikely to ever catch on in any way remotely approaching that of transcatheter aortic valve replacement for the treatment of aortic stenosis, Blase A. Carabello, MD, predicted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We’ve spent $2 billion looking for methods of percutaneous mitral valve replacement, and yet, I have to wonder if that makes any sense,” said Dr. Carabello, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C.

“If repair is superior to replacement in primary MR [mitral regurgitation], which I think we all agree is true, and you don’t need to get rid of every last molecule of blood going backward across the mitral valve when you’ve got a good left ventricle, then a percutaneous replacement in primary MR would have only the niche of patients who are inoperable and whose leaflets can’t be grabbed by the MitraClip or some new percutaneous device down the road. And, in secondary MR, it doesn’t seem to matter whether you replace or repair the valve, so why not just repair it with a clip?” he argued.

Numerous nonrandomized studies have invariably demonstrated superior survival for surgical repair versus replacement in patients with primary MR.

“There’s never going to be a randomized controlled trial of repair versus replacement; there’s no equipoise there. We all believe that, in primary MR, repair is superior to replacement. There are no data anywhere to suggest the opposite. It’s essentially sacrosanct,” according to the cardiologist.

In contrast, a major randomized trial of surgical repair versus replacement has been conducted in patients with severe secondary MR. This NIH-funded study conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network found no difference in survival between the two groups (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 28; 374[4]:344-53). That’s not a surprising result, Dr. Carabello said, since the underlying cause of this type of valve disease is a sick left ventricle. But, since surgical repair entails less morbidity than replacement – and a percutaneous repair with a leaflet-grasping device such as the MitraClip is simpler and safer than a surgical repair – it seems likely that the future treatment for secondary MR will be a percutaneous device, he said.

That future could depend upon the results of the ongoing COAPT trial (Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy), in which the MitraClip is being studied as an alternative to surgical repair for significant secondary MR. The MitraClip, which doesn’t entail a concomitant annuloplasty, is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration only for patients with primary, degenerative mitral regurgitation not amenable to surgical repair. But, if COAPT yields positive results, the role of the MitraClip will greatly expand.

An intriguing and poorly understood difference exists in the significance of residual mitral regurgitation following surgical repair as opposed to percutaneous MitraClip repair, Dr. Carabello observed.

“I go to the OR a lot, and I know of no surgeon [who] will leave 2+ MR behind. Most surgeons won’t leave 1+ MR behind. They’ll put the patient back on the pump to repair even mild residual MR, accepting only trace MR or zero before they leave the OR because they know that the best predictor of a failed mitral repair is the presence of residual MR in the OR,” he said.

In contrast, following successful deployment of the MitraClip most patients are left with 1-2+ MR. Yet, as was demonstrated in the 5-year results of the randomized EVEREST II trial (Endovascular Valve Edge-to-Edge Repair Study), this residual MR wasn’t a harbinger of poor outcomes long-term (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 29;66[25]:2844-54).

“You would have expected, with that much residual MR, there would be a perpetually increasing failure rate over time, but that didn’t happen. In Everest II, there was an early failure rate for percutaneous repair, where the MitraClip didn’t work and those patients required surgical mitral valve repair. But, after the first 6 months, the failure rate for the clip was exactly the same as the surgical failure rate, even though, with the clip, you start with more MR to begin with,” the cardiologist noted.

The MitraClip procedure is modeled after the surgical Alfieri double-orifice end-to-end stitch technique, which has been shown to have durable results when performed in conjunction with an annuloplasty ring for primary MR.

“The MitraClip essentially joins the valve in the middle the way the Alfieri stitch does, but it doesn’t appear to behave the same way. Why is that? Maybe the clip does something different than the Alfieri stitch on which it was modeled. Maybe that bar in the middle of the mitral valve does something in terms of scarring or stabilization that we don’t know about yet,” he speculated.

As for the prospects for percutaneous mitral valve replacement, Dr. Carabello said that this type of procedure “is a very difficult thing to do, and so far, has been met with a fair amount of failure. It’ll be very interesting to see what percentage of market share it gets 10 years down the road. My prediction is that, for mitral regurgitation, repair is always going to be it.”

Dr. Carabello reported serving on a data safety monitoring board for Edwards Lifesciences.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Percutaneous mitral valve replacement is unlikely to ever catch on in any way remotely approaching that of transcatheter aortic valve replacement for the treatment of aortic stenosis, Blase A. Carabello, MD, predicted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We’ve spent $2 billion looking for methods of percutaneous mitral valve replacement, and yet, I have to wonder if that makes any sense,” said Dr. Carabello, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C.

“If repair is superior to replacement in primary MR [mitral regurgitation], which I think we all agree is true, and you don’t need to get rid of every last molecule of blood going backward across the mitral valve when you’ve got a good left ventricle, then a percutaneous replacement in primary MR would have only the niche of patients who are inoperable and whose leaflets can’t be grabbed by the MitraClip or some new percutaneous device down the road. And, in secondary MR, it doesn’t seem to matter whether you replace or repair the valve, so why not just repair it with a clip?” he argued.

Numerous nonrandomized studies have invariably demonstrated superior survival for surgical repair versus replacement in patients with primary MR.

“There’s never going to be a randomized controlled trial of repair versus replacement; there’s no equipoise there. We all believe that, in primary MR, repair is superior to replacement. There are no data anywhere to suggest the opposite. It’s essentially sacrosanct,” according to the cardiologist.

In contrast, a major randomized trial of surgical repair versus replacement has been conducted in patients with severe secondary MR. This NIH-funded study conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network found no difference in survival between the two groups (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 28; 374[4]:344-53). That’s not a surprising result, Dr. Carabello said, since the underlying cause of this type of valve disease is a sick left ventricle. But, since surgical repair entails less morbidity than replacement – and a percutaneous repair with a leaflet-grasping device such as the MitraClip is simpler and safer than a surgical repair – it seems likely that the future treatment for secondary MR will be a percutaneous device, he said.

That future could depend upon the results of the ongoing COAPT trial (Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy), in which the MitraClip is being studied as an alternative to surgical repair for significant secondary MR. The MitraClip, which doesn’t entail a concomitant annuloplasty, is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration only for patients with primary, degenerative mitral regurgitation not amenable to surgical repair. But, if COAPT yields positive results, the role of the MitraClip will greatly expand.

An intriguing and poorly understood difference exists in the significance of residual mitral regurgitation following surgical repair as opposed to percutaneous MitraClip repair, Dr. Carabello observed.

“I go to the OR a lot, and I know of no surgeon [who] will leave 2+ MR behind. Most surgeons won’t leave 1+ MR behind. They’ll put the patient back on the pump to repair even mild residual MR, accepting only trace MR or zero before they leave the OR because they know that the best predictor of a failed mitral repair is the presence of residual MR in the OR,” he said.

In contrast, following successful deployment of the MitraClip most patients are left with 1-2+ MR. Yet, as was demonstrated in the 5-year results of the randomized EVEREST II trial (Endovascular Valve Edge-to-Edge Repair Study), this residual MR wasn’t a harbinger of poor outcomes long-term (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 29;66[25]:2844-54).

“You would have expected, with that much residual MR, there would be a perpetually increasing failure rate over time, but that didn’t happen. In Everest II, there was an early failure rate for percutaneous repair, where the MitraClip didn’t work and those patients required surgical mitral valve repair. But, after the first 6 months, the failure rate for the clip was exactly the same as the surgical failure rate, even though, with the clip, you start with more MR to begin with,” the cardiologist noted.

The MitraClip procedure is modeled after the surgical Alfieri double-orifice end-to-end stitch technique, which has been shown to have durable results when performed in conjunction with an annuloplasty ring for primary MR.

“The MitraClip essentially joins the valve in the middle the way the Alfieri stitch does, but it doesn’t appear to behave the same way. Why is that? Maybe the clip does something different than the Alfieri stitch on which it was modeled. Maybe that bar in the middle of the mitral valve does something in terms of scarring or stabilization that we don’t know about yet,” he speculated.

As for the prospects for percutaneous mitral valve replacement, Dr. Carabello said that this type of procedure “is a very difficult thing to do, and so far, has been met with a fair amount of failure. It’ll be very interesting to see what percentage of market share it gets 10 years down the road. My prediction is that, for mitral regurgitation, repair is always going to be it.”

Dr. Carabello reported serving on a data safety monitoring board for Edwards Lifesciences.

Prediction: LVADs will rule end-stage heart failure

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Multifaceted progress in mechanical circulatory support as long-term therapy in end-stage heart failure is happening at a brisk pace, Y. Joseph C. Woo, MD, reported at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

declared Dr. Woo, professor and chair of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University.

That’s quite a prediction, especially considering the source: Stanford is where the late Dr. Norman Shumway – widely considered “the father of heart transplantation” – performed the first adult heart transplant in the United States in 1968.

Dr. Woo was coauthor of an American Heart Association policy statement on the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States, which forecast a 25% increase in heart failure between 2010 and 2030 (Circulation. 2011 Mar 1;123[8]:933-44). There is simply no way that heart transplantation can begin to meet the projected growing need for effective therapy in patients with end-stage disease.

Here’s what Dr. Woo sees as the future of MCS:

Minimally invasive implantation

At Stanford, LVAD implantations are now routinely done off-pump on a beating heart.

“We clamp only when there is a sound reason, like the presence of left ventricular thrombus, where you run the risk of embolization without the cross clamp,” the surgeon said.

Concomitant valvular surgery

At Stanford and other centers of excellence, surgeons perform additional procedures as warranted while they implant an LVAD, including atrial fibrillation ablation, revascularization of the right heart coronaries, patent foramen ovale closure, and repair of the tricuspid, pulmonic, or aortic valves.

Enhanced right ventricular management

Survival is greatly impaired if a patient with an LVAD later requires the addition of a right ventricular assist device. This realization has led to the development of multiple preoperative risk scoring systems by the Stanford group (Ann Thorac Surg. 2013 Sep;96[3]:857-63) and others, including investigators at the Deutsche Herzzentrum Berlin, the world’s busiest heart transplant center. The purpose is to identify upfront those patients who are likely to later develop right heart failure so they can receive biventricular MCS from the start.

Adjunctive biologic therapies

Intramyocardial injection of 25 million allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cells during LVAD implantation appeared to be safe and showed a promising efficacy signal in a 30-patient, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, National Institutes of Health–sponsored proof of concept study in which Dr. Woo was a coinvestigator (Circulation. 2014 Jun 3;129[22]:2287-96).

The goal of this research effort is to provide a cell therapy assist to the LVAD as a bridge to recovery of left ventricular function such that the device might eventually no longer be needed, he explained.

These cells are immune privileged. They can be transplanted into recipients without need for immunosuppressive therapy or HLA matching, basically as an off the shelf product. Rather than transforming into cardiomyocytes, it appears that the mechanism by which the donor cells enhance cardiac performance in heart failure is via secretion of a shower of growth and angiogenic factors.

Based upon the encouraging results of the initial study, a 90-patient, phase II, double-blind clinical trial is underway. In order to better evaluate efficacy, this time the patients will receive 150 million mesenchymal precursor cells rather than 25 million.

New technologies

The developmental pipeline is chock full of MCS devices. The trend is to go smaller and simpler. HeartWare is developing a miniaturized version of its approved continuous flow centrifugal force LVAD. The ReliantHeart aVAD, an intraventricular device less than 2.5 cm in diameter, is approved in Europe and under study in the U.S. The Thoratec HeartMate III is a smaller version of the HeartMate II, which is FDA-approved as destination therapy. And the Circulite Synergy micropump, designed to provide partial circulatory support to patients who don’t require a full-force LVAD, is the size of a AA battery.

Dr. Woo reported having no financial conflicts.

[email protected]

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Multifaceted progress in mechanical circulatory support as long-term therapy in end-stage heart failure is happening at a brisk pace, Y. Joseph C. Woo, MD, reported at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

declared Dr. Woo, professor and chair of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University.

That’s quite a prediction, especially considering the source: Stanford is where the late Dr. Norman Shumway – widely considered “the father of heart transplantation” – performed the first adult heart transplant in the United States in 1968.

Dr. Woo was coauthor of an American Heart Association policy statement on the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States, which forecast a 25% increase in heart failure between 2010 and 2030 (Circulation. 2011 Mar 1;123[8]:933-44). There is simply no way that heart transplantation can begin to meet the projected growing need for effective therapy in patients with end-stage disease.

Here’s what Dr. Woo sees as the future of MCS:

Minimally invasive implantation

At Stanford, LVAD implantations are now routinely done off-pump on a beating heart.

“We clamp only when there is a sound reason, like the presence of left ventricular thrombus, where you run the risk of embolization without the cross clamp,” the surgeon said.

Concomitant valvular surgery

At Stanford and other centers of excellence, surgeons perform additional procedures as warranted while they implant an LVAD, including atrial fibrillation ablation, revascularization of the right heart coronaries, patent foramen ovale closure, and repair of the tricuspid, pulmonic, or aortic valves.

Enhanced right ventricular management

Survival is greatly impaired if a patient with an LVAD later requires the addition of a right ventricular assist device. This realization has led to the development of multiple preoperative risk scoring systems by the Stanford group (Ann Thorac Surg. 2013 Sep;96[3]:857-63) and others, including investigators at the Deutsche Herzzentrum Berlin, the world’s busiest heart transplant center. The purpose is to identify upfront those patients who are likely to later develop right heart failure so they can receive biventricular MCS from the start.

Adjunctive biologic therapies

Intramyocardial injection of 25 million allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cells during LVAD implantation appeared to be safe and showed a promising efficacy signal in a 30-patient, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, National Institutes of Health–sponsored proof of concept study in which Dr. Woo was a coinvestigator (Circulation. 2014 Jun 3;129[22]:2287-96).

The goal of this research effort is to provide a cell therapy assist to the LVAD as a bridge to recovery of left ventricular function such that the device might eventually no longer be needed, he explained.

These cells are immune privileged. They can be transplanted into recipients without need for immunosuppressive therapy or HLA matching, basically as an off the shelf product. Rather than transforming into cardiomyocytes, it appears that the mechanism by which the donor cells enhance cardiac performance in heart failure is via secretion of a shower of growth and angiogenic factors.

Based upon the encouraging results of the initial study, a 90-patient, phase II, double-blind clinical trial is underway. In order to better evaluate efficacy, this time the patients will receive 150 million mesenchymal precursor cells rather than 25 million.

New technologies

The developmental pipeline is chock full of MCS devices. The trend is to go smaller and simpler. HeartWare is developing a miniaturized version of its approved continuous flow centrifugal force LVAD. The ReliantHeart aVAD, an intraventricular device less than 2.5 cm in diameter, is approved in Europe and under study in the U.S. The Thoratec HeartMate III is a smaller version of the HeartMate II, which is FDA-approved as destination therapy. And the Circulite Synergy micropump, designed to provide partial circulatory support to patients who don’t require a full-force LVAD, is the size of a AA battery.

Dr. Woo reported having no financial conflicts.

[email protected]

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Multifaceted progress in mechanical circulatory support as long-term therapy in end-stage heart failure is happening at a brisk pace, Y. Joseph C. Woo, MD, reported at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

declared Dr. Woo, professor and chair of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University.

That’s quite a prediction, especially considering the source: Stanford is where the late Dr. Norman Shumway – widely considered “the father of heart transplantation” – performed the first adult heart transplant in the United States in 1968.

Dr. Woo was coauthor of an American Heart Association policy statement on the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States, which forecast a 25% increase in heart failure between 2010 and 2030 (Circulation. 2011 Mar 1;123[8]:933-44). There is simply no way that heart transplantation can begin to meet the projected growing need for effective therapy in patients with end-stage disease.

Here’s what Dr. Woo sees as the future of MCS:

Minimally invasive implantation

At Stanford, LVAD implantations are now routinely done off-pump on a beating heart.

“We clamp only when there is a sound reason, like the presence of left ventricular thrombus, where you run the risk of embolization without the cross clamp,” the surgeon said.

Concomitant valvular surgery

At Stanford and other centers of excellence, surgeons perform additional procedures as warranted while they implant an LVAD, including atrial fibrillation ablation, revascularization of the right heart coronaries, patent foramen ovale closure, and repair of the tricuspid, pulmonic, or aortic valves.

Enhanced right ventricular management

Survival is greatly impaired if a patient with an LVAD later requires the addition of a right ventricular assist device. This realization has led to the development of multiple preoperative risk scoring systems by the Stanford group (Ann Thorac Surg. 2013 Sep;96[3]:857-63) and others, including investigators at the Deutsche Herzzentrum Berlin, the world’s busiest heart transplant center. The purpose is to identify upfront those patients who are likely to later develop right heart failure so they can receive biventricular MCS from the start.

Adjunctive biologic therapies

Intramyocardial injection of 25 million allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cells during LVAD implantation appeared to be safe and showed a promising efficacy signal in a 30-patient, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, National Institutes of Health–sponsored proof of concept study in which Dr. Woo was a coinvestigator (Circulation. 2014 Jun 3;129[22]:2287-96).

The goal of this research effort is to provide a cell therapy assist to the LVAD as a bridge to recovery of left ventricular function such that the device might eventually no longer be needed, he explained.

These cells are immune privileged. They can be transplanted into recipients without need for immunosuppressive therapy or HLA matching, basically as an off the shelf product. Rather than transforming into cardiomyocytes, it appears that the mechanism by which the donor cells enhance cardiac performance in heart failure is via secretion of a shower of growth and angiogenic factors.

Based upon the encouraging results of the initial study, a 90-patient, phase II, double-blind clinical trial is underway. In order to better evaluate efficacy, this time the patients will receive 150 million mesenchymal precursor cells rather than 25 million.

New technologies

The developmental pipeline is chock full of MCS devices. The trend is to go smaller and simpler. HeartWare is developing a miniaturized version of its approved continuous flow centrifugal force LVAD. The ReliantHeart aVAD, an intraventricular device less than 2.5 cm in diameter, is approved in Europe and under study in the U.S. The Thoratec HeartMate III is a smaller version of the HeartMate II, which is FDA-approved as destination therapy. And the Circulite Synergy micropump, designed to provide partial circulatory support to patients who don’t require a full-force LVAD, is the size of a AA battery.

Dr. Woo reported having no financial conflicts.

[email protected]

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Watch and wait often better than resecting in ground-glass opacities

Three years of follow-up is adequate for partially solid ground-glass opacity lesions that do not progress, while pure ground-glass opacity lesions that show no progression may require further follow-up care, a study suggests.

The results of the study strengthen the argument for taking a “watch and wait” approach, and raise the question of whether patient outcomes can be improved without more precise diagnostic criteria, said study author Shigei Sawada, MD, PhD, a researcher at the Shikoku Cancer Center in Matsuyama, Japan, and his colleagues. They drew these conclusions from performing a long-term outcome investigation of 226 patients with pure or mixed ground-glass opacity lesions shown by CT imaging to be 3 cm or less in diameter.

Once established that the disease has stabilized in a pure or mixed ground-glass opacity lesion, “the frequency of CT examinations could probably be reduced or ... discontinued,” the investigators wrote. The study is published online in Chest (2017;151[2]:308-15).

Because ground-glass opacities often can remain unchanged for years, reflexively choosing resection can result in a patient’s being overtreated. Meanwhile, the use of increasingly accurate imaging technology likely means detection rates of such lesions will continue to increase, leaving clinicians to wonder about optimal management protocols, particularly since several guidance documents include differing recommendations on the timing of surveillance CTs for patients with stable disease.

The study includes 10-15 years of follow-up data on the 226 patients, registered between 2000 and 2005. Across the study, there were nearly twice as many women as men, all with an average age of 61 years. About a quarter had multiple ground-glass opacities; about a quarter also had partially consolidated lesions. Of the 124 patients who’d had resections, all but one was stage IA. The most prominent histologic subtype was adenocarcinoma in situ in 63 patients, followed by 39 patients with minimally invasive adenocarcinomas, and 19 with lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas. Five patients had papillary-predominant adenocarcinomas.

Roughly one-quarter of the cohort did not receive follow-up examinations after 68 months, as their lesions either remained stable or were shown to have reduced in size. Another 45 continued to undergo follow-up examinations.

After initial detection of a pure ground-glass opacity, the CT examination schedule was every 3, 6, and 12 months, and then annually. After detection of a mixed ground-glass opacity, a CT examination was given every 3 months for the first year, then reduced to every 6 months thereafter. In patients with stable disease, the individual clinicians determined whether to obtain additional CT follow-up imaging.

A ground-glass lesion was determined to have progressed if the diameter increased, as it did in about a third of patients; or, if there was new or increased consolidation, as there was in about two-thirds of patients. The table of consolidation/tumor ratios (CTR) used included CTR zero, also referred to as a pure ground-glass lesion; CTR 1-25; CTR 26-50; and CTR equal to or greater than 51. When there were multiple lesions, the largest one detected was the target.

All cases of patients with a CTR of more than zero were identified within 3 years, while 13.6% of patients with a CTR of zero required more than 3 years to identify tumor growth. Aggressive cancer was detected in 4% of patients with a CTR of zero and in 70% of those with a CTR greater than 25% (P less than .001). Aggressive cancer was seen in 46% of those with consolidation/tumor ratios that increased during follow-up and in 8% of those whose tumors increased in diameter (P less than .007). After about 10 years of follow-up after resection, 1.6% of cancers recurred.

There were two deaths from lung cancer among the study’s patients. The first, a 54-year-old man, had an acinar-predominant adenocarcinoma, 5 mm in diameter with a consolidation/tumor ratio of 0.75 that increased during follow-up. The recurrence developed in the mediastinal lymph nodes 51 months after resection surgery. The second patient had a papillary-predominant adenocarcinoma appearing as a pure ground-glass opacity 27 mm in diameter. The consolidation/tumor ratio also increased during follow-up, with recurrences in the bone and mediastinal lymph nodes at 30 months post resectioning.

Neither patient was re-biopsied, and both were diagnosed according to CT imaging alone. There were 13 other patient deaths from non–lung cancer related causes.

Given the 3-year timespan necessary to detect tumor growth in all but the CTR zero group, and the study’s size and long-term nature, the investigators concluded that a follow-up period of 3 years for patients with part-solid lesions “should be adequate.”

By contrast, CHEST recommends CT scans be done for at least 3 years in patients with pure ground-glass lesions and between 3 and 5 years in the other CTR groups with nodules measuring 8 mm or less. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline advises low-dose CT scanning until a patient is no longer eligible for definitive treatment.

Dr. Sawada and his colleagues did not use an exact criterion for tumor growth in their study, such as a precise ratio of increase in size or consolidation, in part because at the time of the study the most common form of CT evaluation was visual inspection; they reported that tumors exhibiting growth most commonly increased between 2 and 3 mm in either size or consolidation. “Evaluations based on visual inspections can be imprecise, and different physicians may arrive at different judgments,” the investigators wrote. “However, [the use of] computer-aided diagnosis systems are not yet commonly applied in clinical practice.”

Although imaging should have guided the decision to resect, according to Dr. Sawada and his coauthors, two-thirds of patients in the study were given the procedure even though their lesions were not shown by CT scans to have progressed. This was done either at the patient’s request, or per the clinical judgment of a physician.

Also becoming more specific about changing CTRs would be helpful in developing management protocols, according to Dr. Detterbeck. “In my opinion, we need to start factoring in the rate of change. A gradual 2 mm increase in size over a period of 5 years may not be an appropriate trigger for resection.”

Neither the investigators nor the editorial writer had any relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Eric Gartman, MD, FCCP, comments: This study provides further support that the biology of ground-glass and part-solid nodules is different than fully solid nodules – and we should not be in a rush to resect these lesions. While the recommendations are likely to evolve over time as more information becomes available, this conservative approach toward nonsolid nodules is currently adopted in the Lung-RADS guidelines.

Eric Gartman, MD, FCCP, comments: This study provides further support that the biology of ground-glass and part-solid nodules is different than fully solid nodules – and we should not be in a rush to resect these lesions. While the recommendations are likely to evolve over time as more information becomes available, this conservative approach toward nonsolid nodules is currently adopted in the Lung-RADS guidelines.

Eric Gartman, MD, FCCP, comments: This study provides further support that the biology of ground-glass and part-solid nodules is different than fully solid nodules – and we should not be in a rush to resect these lesions. While the recommendations are likely to evolve over time as more information becomes available, this conservative approach toward nonsolid nodules is currently adopted in the Lung-RADS guidelines.

Three years of follow-up is adequate for partially solid ground-glass opacity lesions that do not progress, while pure ground-glass opacity lesions that show no progression may require further follow-up care, a study suggests.

The results of the study strengthen the argument for taking a “watch and wait” approach, and raise the question of whether patient outcomes can be improved without more precise diagnostic criteria, said study author Shigei Sawada, MD, PhD, a researcher at the Shikoku Cancer Center in Matsuyama, Japan, and his colleagues. They drew these conclusions from performing a long-term outcome investigation of 226 patients with pure or mixed ground-glass opacity lesions shown by CT imaging to be 3 cm or less in diameter.

Once established that the disease has stabilized in a pure or mixed ground-glass opacity lesion, “the frequency of CT examinations could probably be reduced or ... discontinued,” the investigators wrote. The study is published online in Chest (2017;151[2]:308-15).

Because ground-glass opacities often can remain unchanged for years, reflexively choosing resection can result in a patient’s being overtreated. Meanwhile, the use of increasingly accurate imaging technology likely means detection rates of such lesions will continue to increase, leaving clinicians to wonder about optimal management protocols, particularly since several guidance documents include differing recommendations on the timing of surveillance CTs for patients with stable disease.

The study includes 10-15 years of follow-up data on the 226 patients, registered between 2000 and 2005. Across the study, there were nearly twice as many women as men, all with an average age of 61 years. About a quarter had multiple ground-glass opacities; about a quarter also had partially consolidated lesions. Of the 124 patients who’d had resections, all but one was stage IA. The most prominent histologic subtype was adenocarcinoma in situ in 63 patients, followed by 39 patients with minimally invasive adenocarcinomas, and 19 with lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas. Five patients had papillary-predominant adenocarcinomas.

Roughly one-quarter of the cohort did not receive follow-up examinations after 68 months, as their lesions either remained stable or were shown to have reduced in size. Another 45 continued to undergo follow-up examinations.

After initial detection of a pure ground-glass opacity, the CT examination schedule was every 3, 6, and 12 months, and then annually. After detection of a mixed ground-glass opacity, a CT examination was given every 3 months for the first year, then reduced to every 6 months thereafter. In patients with stable disease, the individual clinicians determined whether to obtain additional CT follow-up imaging.

A ground-glass lesion was determined to have progressed if the diameter increased, as it did in about a third of patients; or, if there was new or increased consolidation, as there was in about two-thirds of patients. The table of consolidation/tumor ratios (CTR) used included CTR zero, also referred to as a pure ground-glass lesion; CTR 1-25; CTR 26-50; and CTR equal to or greater than 51. When there were multiple lesions, the largest one detected was the target.

All cases of patients with a CTR of more than zero were identified within 3 years, while 13.6% of patients with a CTR of zero required more than 3 years to identify tumor growth. Aggressive cancer was detected in 4% of patients with a CTR of zero and in 70% of those with a CTR greater than 25% (P less than .001). Aggressive cancer was seen in 46% of those with consolidation/tumor ratios that increased during follow-up and in 8% of those whose tumors increased in diameter (P less than .007). After about 10 years of follow-up after resection, 1.6% of cancers recurred.

There were two deaths from lung cancer among the study’s patients. The first, a 54-year-old man, had an acinar-predominant adenocarcinoma, 5 mm in diameter with a consolidation/tumor ratio of 0.75 that increased during follow-up. The recurrence developed in the mediastinal lymph nodes 51 months after resection surgery. The second patient had a papillary-predominant adenocarcinoma appearing as a pure ground-glass opacity 27 mm in diameter. The consolidation/tumor ratio also increased during follow-up, with recurrences in the bone and mediastinal lymph nodes at 30 months post resectioning.

Neither patient was re-biopsied, and both were diagnosed according to CT imaging alone. There were 13 other patient deaths from non–lung cancer related causes.

Given the 3-year timespan necessary to detect tumor growth in all but the CTR zero group, and the study’s size and long-term nature, the investigators concluded that a follow-up period of 3 years for patients with part-solid lesions “should be adequate.”

By contrast, CHEST recommends CT scans be done for at least 3 years in patients with pure ground-glass lesions and between 3 and 5 years in the other CTR groups with nodules measuring 8 mm or less. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline advises low-dose CT scanning until a patient is no longer eligible for definitive treatment.

Dr. Sawada and his colleagues did not use an exact criterion for tumor growth in their study, such as a precise ratio of increase in size or consolidation, in part because at the time of the study the most common form of CT evaluation was visual inspection; they reported that tumors exhibiting growth most commonly increased between 2 and 3 mm in either size or consolidation. “Evaluations based on visual inspections can be imprecise, and different physicians may arrive at different judgments,” the investigators wrote. “However, [the use of] computer-aided diagnosis systems are not yet commonly applied in clinical practice.”

Although imaging should have guided the decision to resect, according to Dr. Sawada and his coauthors, two-thirds of patients in the study were given the procedure even though their lesions were not shown by CT scans to have progressed. This was done either at the patient’s request, or per the clinical judgment of a physician.

Also becoming more specific about changing CTRs would be helpful in developing management protocols, according to Dr. Detterbeck. “In my opinion, we need to start factoring in the rate of change. A gradual 2 mm increase in size over a period of 5 years may not be an appropriate trigger for resection.”

Neither the investigators nor the editorial writer had any relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Three years of follow-up is adequate for partially solid ground-glass opacity lesions that do not progress, while pure ground-glass opacity lesions that show no progression may require further follow-up care, a study suggests.

The results of the study strengthen the argument for taking a “watch and wait” approach, and raise the question of whether patient outcomes can be improved without more precise diagnostic criteria, said study author Shigei Sawada, MD, PhD, a researcher at the Shikoku Cancer Center in Matsuyama, Japan, and his colleagues. They drew these conclusions from performing a long-term outcome investigation of 226 patients with pure or mixed ground-glass opacity lesions shown by CT imaging to be 3 cm or less in diameter.

Once established that the disease has stabilized in a pure or mixed ground-glass opacity lesion, “the frequency of CT examinations could probably be reduced or ... discontinued,” the investigators wrote. The study is published online in Chest (2017;151[2]:308-15).

Because ground-glass opacities often can remain unchanged for years, reflexively choosing resection can result in a patient’s being overtreated. Meanwhile, the use of increasingly accurate imaging technology likely means detection rates of such lesions will continue to increase, leaving clinicians to wonder about optimal management protocols, particularly since several guidance documents include differing recommendations on the timing of surveillance CTs for patients with stable disease.

The study includes 10-15 years of follow-up data on the 226 patients, registered between 2000 and 2005. Across the study, there were nearly twice as many women as men, all with an average age of 61 years. About a quarter had multiple ground-glass opacities; about a quarter also had partially consolidated lesions. Of the 124 patients who’d had resections, all but one was stage IA. The most prominent histologic subtype was adenocarcinoma in situ in 63 patients, followed by 39 patients with minimally invasive adenocarcinomas, and 19 with lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas. Five patients had papillary-predominant adenocarcinomas.

Roughly one-quarter of the cohort did not receive follow-up examinations after 68 months, as their lesions either remained stable or were shown to have reduced in size. Another 45 continued to undergo follow-up examinations.

After initial detection of a pure ground-glass opacity, the CT examination schedule was every 3, 6, and 12 months, and then annually. After detection of a mixed ground-glass opacity, a CT examination was given every 3 months for the first year, then reduced to every 6 months thereafter. In patients with stable disease, the individual clinicians determined whether to obtain additional CT follow-up imaging.

A ground-glass lesion was determined to have progressed if the diameter increased, as it did in about a third of patients; or, if there was new or increased consolidation, as there was in about two-thirds of patients. The table of consolidation/tumor ratios (CTR) used included CTR zero, also referred to as a pure ground-glass lesion; CTR 1-25; CTR 26-50; and CTR equal to or greater than 51. When there were multiple lesions, the largest one detected was the target.

All cases of patients with a CTR of more than zero were identified within 3 years, while 13.6% of patients with a CTR of zero required more than 3 years to identify tumor growth. Aggressive cancer was detected in 4% of patients with a CTR of zero and in 70% of those with a CTR greater than 25% (P less than .001). Aggressive cancer was seen in 46% of those with consolidation/tumor ratios that increased during follow-up and in 8% of those whose tumors increased in diameter (P less than .007). After about 10 years of follow-up after resection, 1.6% of cancers recurred.

There were two deaths from lung cancer among the study’s patients. The first, a 54-year-old man, had an acinar-predominant adenocarcinoma, 5 mm in diameter with a consolidation/tumor ratio of 0.75 that increased during follow-up. The recurrence developed in the mediastinal lymph nodes 51 months after resection surgery. The second patient had a papillary-predominant adenocarcinoma appearing as a pure ground-glass opacity 27 mm in diameter. The consolidation/tumor ratio also increased during follow-up, with recurrences in the bone and mediastinal lymph nodes at 30 months post resectioning.

Neither patient was re-biopsied, and both were diagnosed according to CT imaging alone. There were 13 other patient deaths from non–lung cancer related causes.

Given the 3-year timespan necessary to detect tumor growth in all but the CTR zero group, and the study’s size and long-term nature, the investigators concluded that a follow-up period of 3 years for patients with part-solid lesions “should be adequate.”

By contrast, CHEST recommends CT scans be done for at least 3 years in patients with pure ground-glass lesions and between 3 and 5 years in the other CTR groups with nodules measuring 8 mm or less. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline advises low-dose CT scanning until a patient is no longer eligible for definitive treatment.

Dr. Sawada and his colleagues did not use an exact criterion for tumor growth in their study, such as a precise ratio of increase in size or consolidation, in part because at the time of the study the most common form of CT evaluation was visual inspection; they reported that tumors exhibiting growth most commonly increased between 2 and 3 mm in either size or consolidation. “Evaluations based on visual inspections can be imprecise, and different physicians may arrive at different judgments,” the investigators wrote. “However, [the use of] computer-aided diagnosis systems are not yet commonly applied in clinical practice.”

Although imaging should have guided the decision to resect, according to Dr. Sawada and his coauthors, two-thirds of patients in the study were given the procedure even though their lesions were not shown by CT scans to have progressed. This was done either at the patient’s request, or per the clinical judgment of a physician.

Also becoming more specific about changing CTRs would be helpful in developing management protocols, according to Dr. Detterbeck. “In my opinion, we need to start factoring in the rate of change. A gradual 2 mm increase in size over a period of 5 years may not be an appropriate trigger for resection.”

Neither the investigators nor the editorial writer had any relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 226 patients with ground-glass opacity lesions 3 cm or less in size, 124 had resection, 57 required no further follow-up, and 45 continue to receive follow-up.

Data source: Long-term study of 226 patients with pure or mixed ground-glass opacities of 3 cm or less given regular CT imaging between 2000 and 2005.

Disclosures: Neither the investigators nor the editorial writer had any relevant disclosures.

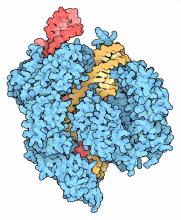

Will genome editing advance animal-to-human transplantation?

Advances in gene editing are pushing the possibility of raising pigs for organs that may be transplanted into humans with immunosuppression regimens comparable to those now used in human-to-human transplants, coauthors James Butler, MD, and A. Joseph Tector, MD, PhD, stated in an expert opinion in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:488-92).

Developments in genome editing could bring new approaches to management of cardiopulmonary diseases, Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector noted. “Recently, cardiac-specific and lung-specific applications have been described, which will allow for the rapid creation of new models of heart and lung disease,” they said. Specifically, they noted gene targeting might eventually offer a way to treat challenging genetic problems “like the heterogeneous nature of nonsquamous cell lung cancer.”

Dr. Butler is with the department of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and Dr. Tector is with the department of surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

CRISPR technology has been used in developing multiple gene knockout pigs and neutralizing three separate porcine genes that encode human xenoantigens in a single reaction, leading to efficient methods for creating pigs with multiple genetic modifications.

According to the website of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Mass., where researchers perfected the system to work in eukaryotes, CRISPR works by using short RNA sequences designed by researchers to guide the system to matching sequences of DNA. When the target DNA is found, Cas9 – one of the enzymes produced by the CRISPR system – binds to the DNA and cuts it, shutting the targeted gene off.

“By facilitating high-throughput model creation, CRISPR has elucidated which modifications are necessary and which are not; despite the ability to alter many loci concurrently, recent evidence has implicated three porcine genes that are responsible for the majority of human-antiporcine humoral immunity,” Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector wrote.

Those genes are the Gal[alpha]1-3 epitope (Gal-alpha), CMAH and B4GaINT2 genes. “Each of these three genes is expressed in pigs but has been evolutionarily silenced in humans,” the coauthors added.

While CRISPR genome editing has yet to reach its full potential, researchers and clinicians should pay attention, according to Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector.

More recent modifications of CRISPR technology have shown promise in not just knocking out or turning off specific genes, but rather guiding directed replacement of genes with researcher-designed substitutes. This can enable permanent transformation of functional genes with altered behavior, according to the Broad Institute website.

Dr. Tector disclosed he has received funding from United Therapeutics and founded Xenobridge with patents for xenotransplantation. Dr. Butler has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CRISPR and CRISPR-associated proteins have emerged as effective genome editing techniques that may lead to cardiac and lung models and possibly xenotransplantation, Ari A. Mennander, MD, PhD, of the Tampere (Finland) University Heart Hospital, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:492).

The concept Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector discuss involves not using antibodies to ameliorate porcine antibodies that cause rejection in humans, but rather reengineering the genetic composition of pigs to eliminate those antibodies. “According to the wildest of dreams, these genes affecting porcine glycan expression may be silenced, and the human–antiporcine humoral immunity is controlled down to the level comparable with human allograft rejection,” Dr. Mennander said.

However, such a breakthrough carries with it consequences, Dr. Mennander said. “Should one worry about the induction of zoonosis, as well as the ethical aspects of transplanting the patient a whole organ of a pig? Would even a successful xenotransplant program seriously compete with artificial hearts or allografts?” Embracing the method too early would open its advocates to ridicule, he said.

“We are to applaud the researchers for ever-lasting and exemplary enthusiasm for a futuristic new surgical solution; the future may lie as much in current clinical solutions as in innovative discoveries based on persistent scientific experiments,” Dr. Mennander said.

Dr. Mennander had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CRISPR and CRISPR-associated proteins have emerged as effective genome editing techniques that may lead to cardiac and lung models and possibly xenotransplantation, Ari A. Mennander, MD, PhD, of the Tampere (Finland) University Heart Hospital, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:492).

The concept Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector discuss involves not using antibodies to ameliorate porcine antibodies that cause rejection in humans, but rather reengineering the genetic composition of pigs to eliminate those antibodies. “According to the wildest of dreams, these genes affecting porcine glycan expression may be silenced, and the human–antiporcine humoral immunity is controlled down to the level comparable with human allograft rejection,” Dr. Mennander said.

However, such a breakthrough carries with it consequences, Dr. Mennander said. “Should one worry about the induction of zoonosis, as well as the ethical aspects of transplanting the patient a whole organ of a pig? Would even a successful xenotransplant program seriously compete with artificial hearts or allografts?” Embracing the method too early would open its advocates to ridicule, he said.

“We are to applaud the researchers for ever-lasting and exemplary enthusiasm for a futuristic new surgical solution; the future may lie as much in current clinical solutions as in innovative discoveries based on persistent scientific experiments,” Dr. Mennander said.

Dr. Mennander had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CRISPR and CRISPR-associated proteins have emerged as effective genome editing techniques that may lead to cardiac and lung models and possibly xenotransplantation, Ari A. Mennander, MD, PhD, of the Tampere (Finland) University Heart Hospital, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:492).

The concept Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector discuss involves not using antibodies to ameliorate porcine antibodies that cause rejection in humans, but rather reengineering the genetic composition of pigs to eliminate those antibodies. “According to the wildest of dreams, these genes affecting porcine glycan expression may be silenced, and the human–antiporcine humoral immunity is controlled down to the level comparable with human allograft rejection,” Dr. Mennander said.

However, such a breakthrough carries with it consequences, Dr. Mennander said. “Should one worry about the induction of zoonosis, as well as the ethical aspects of transplanting the patient a whole organ of a pig? Would even a successful xenotransplant program seriously compete with artificial hearts or allografts?” Embracing the method too early would open its advocates to ridicule, he said.

“We are to applaud the researchers for ever-lasting and exemplary enthusiasm for a futuristic new surgical solution; the future may lie as much in current clinical solutions as in innovative discoveries based on persistent scientific experiments,” Dr. Mennander said.

Dr. Mennander had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Advances in gene editing are pushing the possibility of raising pigs for organs that may be transplanted into humans with immunosuppression regimens comparable to those now used in human-to-human transplants, coauthors James Butler, MD, and A. Joseph Tector, MD, PhD, stated in an expert opinion in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:488-92).

Developments in genome editing could bring new approaches to management of cardiopulmonary diseases, Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector noted. “Recently, cardiac-specific and lung-specific applications have been described, which will allow for the rapid creation of new models of heart and lung disease,” they said. Specifically, they noted gene targeting might eventually offer a way to treat challenging genetic problems “like the heterogeneous nature of nonsquamous cell lung cancer.”

Dr. Butler is with the department of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and Dr. Tector is with the department of surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

CRISPR technology has been used in developing multiple gene knockout pigs and neutralizing three separate porcine genes that encode human xenoantigens in a single reaction, leading to efficient methods for creating pigs with multiple genetic modifications.

According to the website of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Mass., where researchers perfected the system to work in eukaryotes, CRISPR works by using short RNA sequences designed by researchers to guide the system to matching sequences of DNA. When the target DNA is found, Cas9 – one of the enzymes produced by the CRISPR system – binds to the DNA and cuts it, shutting the targeted gene off.

“By facilitating high-throughput model creation, CRISPR has elucidated which modifications are necessary and which are not; despite the ability to alter many loci concurrently, recent evidence has implicated three porcine genes that are responsible for the majority of human-antiporcine humoral immunity,” Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector wrote.

Those genes are the Gal[alpha]1-3 epitope (Gal-alpha), CMAH and B4GaINT2 genes. “Each of these three genes is expressed in pigs but has been evolutionarily silenced in humans,” the coauthors added.

While CRISPR genome editing has yet to reach its full potential, researchers and clinicians should pay attention, according to Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector.

More recent modifications of CRISPR technology have shown promise in not just knocking out or turning off specific genes, but rather guiding directed replacement of genes with researcher-designed substitutes. This can enable permanent transformation of functional genes with altered behavior, according to the Broad Institute website.

Dr. Tector disclosed he has received funding from United Therapeutics and founded Xenobridge with patents for xenotransplantation. Dr. Butler has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Advances in gene editing are pushing the possibility of raising pigs for organs that may be transplanted into humans with immunosuppression regimens comparable to those now used in human-to-human transplants, coauthors James Butler, MD, and A. Joseph Tector, MD, PhD, stated in an expert opinion in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:488-92).

Developments in genome editing could bring new approaches to management of cardiopulmonary diseases, Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector noted. “Recently, cardiac-specific and lung-specific applications have been described, which will allow for the rapid creation of new models of heart and lung disease,” they said. Specifically, they noted gene targeting might eventually offer a way to treat challenging genetic problems “like the heterogeneous nature of nonsquamous cell lung cancer.”

Dr. Butler is with the department of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and Dr. Tector is with the department of surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

CRISPR technology has been used in developing multiple gene knockout pigs and neutralizing three separate porcine genes that encode human xenoantigens in a single reaction, leading to efficient methods for creating pigs with multiple genetic modifications.

According to the website of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Mass., where researchers perfected the system to work in eukaryotes, CRISPR works by using short RNA sequences designed by researchers to guide the system to matching sequences of DNA. When the target DNA is found, Cas9 – one of the enzymes produced by the CRISPR system – binds to the DNA and cuts it, shutting the targeted gene off.

“By facilitating high-throughput model creation, CRISPR has elucidated which modifications are necessary and which are not; despite the ability to alter many loci concurrently, recent evidence has implicated three porcine genes that are responsible for the majority of human-antiporcine humoral immunity,” Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector wrote.

Those genes are the Gal[alpha]1-3 epitope (Gal-alpha), CMAH and B4GaINT2 genes. “Each of these three genes is expressed in pigs but has been evolutionarily silenced in humans,” the coauthors added.

While CRISPR genome editing has yet to reach its full potential, researchers and clinicians should pay attention, according to Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector.

More recent modifications of CRISPR technology have shown promise in not just knocking out or turning off specific genes, but rather guiding directed replacement of genes with researcher-designed substitutes. This can enable permanent transformation of functional genes with altered behavior, according to the Broad Institute website.

Dr. Tector disclosed he has received funding from United Therapeutics and founded Xenobridge with patents for xenotransplantation. Dr. Butler has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Key clinical point: CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing is advancing the creation of animal models for xenotransplantation into humans.

Major finding: Genome editing tools are moving xenotransplantation models quickly toward potential treatments for cardiopulmonary disease.

Data source: Expert opinion with literature review.

Disclosures: Dr. Tector disclosed he has received funding from United Therapeutics and founded Xenobridge with patents for xenotransplantation. Dr. Butler reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Moderate stenosis in coronary arteries grows severe over time

HOUSTON – Most nongrafted, moderately stenosed coronary arteries progress to severe stenosis or occlusion in the long term, results from a large, long-term study have shown.

“Not uncommonly, patients referred for coronary surgery have one or more coronary arteries with only moderate stenosis,” Joseph F. Sabik III, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“There is controversy as to whether arteries with only moderate stenosis should be grafted during coronary surgery, and if it should be grafted, with what conduit?” For example, the Fractional Flow Reserve-Guided PCI versus Medical Therapy in Stable Coronary Disease study, known as FAME, suggests not intervening on moderate stenosis, since stenting non–ischemia-producing lesions led to worse outcomes (N Engl J Med. 2012 Sep 13;367:991-1001). However, Dr. Sabik, who chairs the department of surgery at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, and his associates recently reported that grafting moderately stenosed coronary arteries during surgical revascularization is not harmful and can be beneficial by improving survival if an internal thoracic artery graft is used (J. Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2016 Mar;151[3]:806-11).

In an effort to determine how grafting moderately stenosed coronary arteries influences native-vessel disease progression, and whether grafting may be protective from late ischemia, Dr. Sabik and his associates evaluated the medical records of 55,567 patients who underwent primary isolated coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery at the Cleveland Clinic from 1972 to 2011. Of the 55,567 patients, 1,902 had a single coronary artery with angiographically moderate stenosis (defined as a narrowing of 50%-69%) and results of at least one postoperative angiogram available. Of these moderately stenosed coronary arteries (MSCAs), 488 were not grafted, 385 were internal thoracic artery (ITA)–grafted, and 1,028 were saphenous vein (SV)–grafted. At follow-up angiograms, information about disease progression was available for 488 nongrafted, 371 ITA-grafted, and 957 SV-grafted MSCAs, and patency information was available for 376 ITA and 1,016 SV grafts to these MSCAs. Grafts were considered patent if they were not occluded. Severe occlusion was defined as a narrowing of more than 70%.

The researchers found that at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, native-vessel disease progressed from moderate to severe stenosis/occlusion in 32%, 52%, 66%, and 72% of nongrafted MSCAs, respectively; in 55%, 73%, 84%, and 87% of ITA-grafted MSCAs, and in 67%, 82%, 90%, and 92% of SV-grafted MSCAs. After Dr. Sabik and his associates adjusted for patient characteristics, disease progression in MSCAs was significantly higher with ITA and SV grafting, compared with nongrafting (odds ratios, 3.6 and 9.9, respectively). At 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, occlusion in grafts to MSCAs was 8%, 9%, 11%, and 15%, respectively, for ITA grafts and 13%, 32%, 46%, and 56% for SV grafts. At these same time points, protection from myocardial ischemia in ITA-grafted vs. nongrafted MSCAs was 29%, 47%, 59%, and 61%.

“Our opinion is you that shouldn’t ignore moderate lesions,” Dr. Sabik, surgeon-in-chief and vice president for surgical operations for the University Hospitals system, said in an interview at the meeting. “Although it may not help that patient over the next short period of time, over their lifespan it will. What works for intervention doesn’t necessarily mean it’s right for bypass surgery. If you have a vessel that’s only moderately stenosed you should at least consider grafting it, because moderate lesions progress over time. Bypassing it helps people live longer when you use an internal thoracic artery graft, because they are likely to remain patent. You always have to individualize the therapy, but the key is to use your grafts in the best way possible.”

Dr. Sabik disclosed that he has received research grants from Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, and Edwards Lifesciences.

HOUSTON – Most nongrafted, moderately stenosed coronary arteries progress to severe stenosis or occlusion in the long term, results from a large, long-term study have shown.

“Not uncommonly, patients referred for coronary surgery have one or more coronary arteries with only moderate stenosis,” Joseph F. Sabik III, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“There is controversy as to whether arteries with only moderate stenosis should be grafted during coronary surgery, and if it should be grafted, with what conduit?” For example, the Fractional Flow Reserve-Guided PCI versus Medical Therapy in Stable Coronary Disease study, known as FAME, suggests not intervening on moderate stenosis, since stenting non–ischemia-producing lesions led to worse outcomes (N Engl J Med. 2012 Sep 13;367:991-1001). However, Dr. Sabik, who chairs the department of surgery at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, and his associates recently reported that grafting moderately stenosed coronary arteries during surgical revascularization is not harmful and can be beneficial by improving survival if an internal thoracic artery graft is used (J. Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2016 Mar;151[3]:806-11).