User login

In COPD, tai chi confers long-term benefit

and seems to confer better long-term improvement, suggests a study published online in the journal CHEST®.

Following 12 weeks of participation in tai chi or pulmonary rehabilitation, patients improved in most of the measurements taken, although no significant between-group differences were observed at that time. However, further improvements were observed in the tai chi group 12 weeks after the intervention had ended. These improvements manifested as a statistically significant 4.5 between-group difference in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire points in favor of tai chi (P less than .001)

“This observation, supported also by improvements in dyspnea and exercise performance, suggests that tai chi could be substituted for PR [pulmonary rehabilitation] in the treatment of COPD with greater convenience for patients,” the researchers concluded.

SOURCE: Polkey MI et al. CHEST. 2018 May;153[5]:1116-24.

and seems to confer better long-term improvement, suggests a study published online in the journal CHEST®.

Following 12 weeks of participation in tai chi or pulmonary rehabilitation, patients improved in most of the measurements taken, although no significant between-group differences were observed at that time. However, further improvements were observed in the tai chi group 12 weeks after the intervention had ended. These improvements manifested as a statistically significant 4.5 between-group difference in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire points in favor of tai chi (P less than .001)

“This observation, supported also by improvements in dyspnea and exercise performance, suggests that tai chi could be substituted for PR [pulmonary rehabilitation] in the treatment of COPD with greater convenience for patients,” the researchers concluded.

SOURCE: Polkey MI et al. CHEST. 2018 May;153[5]:1116-24.

and seems to confer better long-term improvement, suggests a study published online in the journal CHEST®.

Following 12 weeks of participation in tai chi or pulmonary rehabilitation, patients improved in most of the measurements taken, although no significant between-group differences were observed at that time. However, further improvements were observed in the tai chi group 12 weeks after the intervention had ended. These improvements manifested as a statistically significant 4.5 between-group difference in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire points in favor of tai chi (P less than .001)

“This observation, supported also by improvements in dyspnea and exercise performance, suggests that tai chi could be substituted for PR [pulmonary rehabilitation] in the treatment of COPD with greater convenience for patients,” the researchers concluded.

SOURCE: Polkey MI et al. CHEST. 2018 May;153[5]:1116-24.

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST®

FDA: More COPD patients can use triple therapy

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new indication for the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) therapy fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol (Trelegy Ellipta), which allows physicians to prescribe the drug to a broader class of COPD patients, according to a statement from two pharmaceutical companies.

“Following the initial approval of Trelegy Ellipta in September, we have analysed the data from the IMPACT study and identified additional benefits that this important medicine offers patients with [COPD],” said Hal Barron, MD, chief scientific officer and president of research and development at GlaxoSmithKline, in the statement. “We are pleased that the robust data from the IMPACT study has enabled the expanded indication announced today and the FDA action has been taken so swiftly.”

The results of the IMPACT trial, which was the first study to compare a single-inhaler triple therapy with two dual therapies, were published on April 18 (N Engl J Med 2018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901).

This study randomized patients to 52 weeks of either triple inhaled therapy involving a once-daily combination of 100 mcg fluticasone furoate, 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium, and 25 mcg of vilanterol; or dual inhaled therapy involving either 100 mcg fluticasone furoate plus 25 mcg of vilanterol, or 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium plus 25 mcg of vilanterol.

After 1 year, the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations in the triple-therapy group was 0.91 per year, compared with 1.07 in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 1.21 in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. This translated to a 15% reduction with triple therapy compared with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol and a 25% reduction, compared with vilanterol-umeclidinium (P less than .001 for both).

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new indication for the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) therapy fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol (Trelegy Ellipta), which allows physicians to prescribe the drug to a broader class of COPD patients, according to a statement from two pharmaceutical companies.

“Following the initial approval of Trelegy Ellipta in September, we have analysed the data from the IMPACT study and identified additional benefits that this important medicine offers patients with [COPD],” said Hal Barron, MD, chief scientific officer and president of research and development at GlaxoSmithKline, in the statement. “We are pleased that the robust data from the IMPACT study has enabled the expanded indication announced today and the FDA action has been taken so swiftly.”

The results of the IMPACT trial, which was the first study to compare a single-inhaler triple therapy with two dual therapies, were published on April 18 (N Engl J Med 2018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901).

This study randomized patients to 52 weeks of either triple inhaled therapy involving a once-daily combination of 100 mcg fluticasone furoate, 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium, and 25 mcg of vilanterol; or dual inhaled therapy involving either 100 mcg fluticasone furoate plus 25 mcg of vilanterol, or 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium plus 25 mcg of vilanterol.

After 1 year, the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations in the triple-therapy group was 0.91 per year, compared with 1.07 in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 1.21 in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. This translated to a 15% reduction with triple therapy compared with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol and a 25% reduction, compared with vilanterol-umeclidinium (P less than .001 for both).

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new indication for the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) therapy fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol (Trelegy Ellipta), which allows physicians to prescribe the drug to a broader class of COPD patients, according to a statement from two pharmaceutical companies.

“Following the initial approval of Trelegy Ellipta in September, we have analysed the data from the IMPACT study and identified additional benefits that this important medicine offers patients with [COPD],” said Hal Barron, MD, chief scientific officer and president of research and development at GlaxoSmithKline, in the statement. “We are pleased that the robust data from the IMPACT study has enabled the expanded indication announced today and the FDA action has been taken so swiftly.”

The results of the IMPACT trial, which was the first study to compare a single-inhaler triple therapy with two dual therapies, were published on April 18 (N Engl J Med 2018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901).

This study randomized patients to 52 weeks of either triple inhaled therapy involving a once-daily combination of 100 mcg fluticasone furoate, 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium, and 25 mcg of vilanterol; or dual inhaled therapy involving either 100 mcg fluticasone furoate plus 25 mcg of vilanterol, or 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium plus 25 mcg of vilanterol.

After 1 year, the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations in the triple-therapy group was 0.91 per year, compared with 1.07 in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 1.21 in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. This translated to a 15% reduction with triple therapy compared with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol and a 25% reduction, compared with vilanterol-umeclidinium (P less than .001 for both).

Triple-therapy cuts COPD exacerbations

Triple therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) achieved reductions in moderate to severe exacerbations when compared with two kinds of dual therapy, in a study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial compared the outcomes of COPD patients using an inhaled therapy comprising a corticosteroid, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) with the outcomes of similar patients taking one of two other therapy combinations – a corticosteroid and a LABA, or a LABA and a LAMA. This trial – Informing the Pathway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) – included 10,355 patients with symptomatic COPD in 37 countries, according to David A. Lipson, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901).

The study randomized patients to 52 weeks of either triple inhaled therapy involving a once-daily combination of 100 mcg fluticasone furoate (a corticosteroid), 62.5 mcg of the LAMA umeclidinium and 25 mcg of the LABA vilanterol; or dual inhaled therapy involving either 100 mcg fluticasone furoate plus 25 mcg of vilanterol, or 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium plus 25 mcg of vilanterol.

After 1 year, the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations in the triple-therapy group was 0.91 per year, compared with 1.07 in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 1.21 in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. This translated to a 15% reduction with triple therapy compared with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol and a 25% reduction compared with vilanterol-umeclidinium (P less than .001 for both).

When the analysis was limited to severe exacerbations alone, the difference was significant only between the triple therapy, which GSK is marketing as Trelegy Ellipta, and the vilanterol-umeclidinium dual therapy.

Dr. Lipson, of GSK and the University of Pennsylvania, and his coauthors noted that their finding of a greater benefit with the glucocorticoid-containing dual-therapy compared with the LABA-LAMA vilanterol-umeclidinium combination contradicted the findings of the earlier FLAME trial. This was likely due to differences in patient populations and design, as all patients in the FLAME trial had a 1-month run-in treatment with the bronchodilator tiotropium, the researchers explained.

“Therefore any patients who would require an inhaled glucocorticoid may have had an increase in exacerbations and a decrease in lung function during the run-in period and would have been forced to leave the trial,” they wrote.

Patients with higher eosinophil levels seemed to do even better with triple therapy. In those with eosinophil levels of 150 cells per microliter or above, the annual rate of moderate to severe exacerbations was 0.95 with triple therapy, 1.08 with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol, and 1.39 with vilanterol-umeclidinium.

Triple therapy also was associated with a significantly longer time to first event and greater improvements in quality of life, compared with the dual therapies.

Overall, the adverse event profile of triple therapy was similar to that of dual therapy. Contrasting that finding were differences in the incidences of physician-diagnosed pneumonia between the treatment groups. Physician-diagnosed pneumonia was 53% higher among patients who received fluticasone furoate – either in dual or triple therapy combinations. Eight percent of patients in the triple therapy group experienced pneumonia, compared with 7% of patients in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 5% in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group.

All-cause mortality was significantly lower in patients who received the inhaled glucocorticoid, although the authors said this finding was “fragile” and needed further investigation.

The rate of discontinuation or withdrawal from the trial was 6% for the triple therapy group, 8% for the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group, and 9% for the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. The rates of serious adverse events in each group were 22%, 21%, and 23%, respectively.

At trial entry, 38% of patients were already receiving triple therapy and 29% were taking an inhaled glucocorticoid. The authors noted that any patients taking an inhaled glucocorticoid who were randomized to the vilanterol-umeclidinium group would have had to abruptly stop taking their inhaled glucocorticoids.

“It is unknown whether the abrupt discontinuation of inhaled glucocorticoids would have contributed to our finding of a lower rate of exacerbations in the inhaled glucocorticoid groups than in the LAMA-LABA group,” they wrote.

Fernando Martinez, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, said the study advanced the understanding of COPD management by addressing some key evidence gaps, in a statement issued by GSK.

“By comparing various combinations of effective medications in the same device the study clarifies which type of patient gains greatest benefit from each class of medicine,” Dr Martinez said in the statement. “As many patients experience frequent exacerbations or ‘flare ups,’ which can often result in hospitalization, these data will be highly relevant to patients and clinicians as they consider the optimal treatment.”

The study was funded by GSK, which manufactures Trelegy Ellipta triple therapy for COPD. Eight authors were employees of GSK and two were on advisory boards for the company. Seven authors declared funding from a range of pharmaceutical companies including GSK. One author had no conflicts of interest to declare.

SOURCE: Lipson D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901.

The data from the IMPACT study fills a gap in the evidence supporting a step-up from dual to triple inhaled therapy for COPD, which so far has been recommended only for patients with severe loss of lung function and those with frequent exacerbations despite maximum bronchodilator treatment. The study has the strengths of comparing the step-up to triple therapy with the GOLD guideline–recommended dual therapies and using the same dosages in the triple therapy as in the dual therapy

However, it is important to note that nearly 40% of patients enrolled in the trial were already being treated with triple therapy, 70% were receiving a glucocorticoid, and patients with a history of asthma were not excluded. This means patients assigned to the dual therapy without glucocorticoids would have had an abrupt cessation of their glucocorticoid therapy, which may explain a rapid surge in exacerbations in the first month and the lower rate of exacerbations in the dual-therapy group that did include glucocorticoids. The choice of patients for the study could potentially have artificially inflated the observed effectiveness of triple therapy over dual bronchodilator treatment.

As such, we suggest clinicians stick with the GOLD 2017 recommendations that escalation to triple therapy only occur after maximization of bronchodilator treatment.

Dr. Samy Suissa (PhD) is with the Center for Clinical Epidemiology at Lady Davis Institute–Jewish General Hospital, and the departments of epidemiology and biostatistics and medicine at McGill University, Montreal. Dr. Jeffrey M. Drazen is editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine. These comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1716802 ). Dr. Suissa declared personal fees and grants from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work.

The data from the IMPACT study fills a gap in the evidence supporting a step-up from dual to triple inhaled therapy for COPD, which so far has been recommended only for patients with severe loss of lung function and those with frequent exacerbations despite maximum bronchodilator treatment. The study has the strengths of comparing the step-up to triple therapy with the GOLD guideline–recommended dual therapies and using the same dosages in the triple therapy as in the dual therapy

However, it is important to note that nearly 40% of patients enrolled in the trial were already being treated with triple therapy, 70% were receiving a glucocorticoid, and patients with a history of asthma were not excluded. This means patients assigned to the dual therapy without glucocorticoids would have had an abrupt cessation of their glucocorticoid therapy, which may explain a rapid surge in exacerbations in the first month and the lower rate of exacerbations in the dual-therapy group that did include glucocorticoids. The choice of patients for the study could potentially have artificially inflated the observed effectiveness of triple therapy over dual bronchodilator treatment.

As such, we suggest clinicians stick with the GOLD 2017 recommendations that escalation to triple therapy only occur after maximization of bronchodilator treatment.

Dr. Samy Suissa (PhD) is with the Center for Clinical Epidemiology at Lady Davis Institute–Jewish General Hospital, and the departments of epidemiology and biostatistics and medicine at McGill University, Montreal. Dr. Jeffrey M. Drazen is editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine. These comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1716802 ). Dr. Suissa declared personal fees and grants from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work.

The data from the IMPACT study fills a gap in the evidence supporting a step-up from dual to triple inhaled therapy for COPD, which so far has been recommended only for patients with severe loss of lung function and those with frequent exacerbations despite maximum bronchodilator treatment. The study has the strengths of comparing the step-up to triple therapy with the GOLD guideline–recommended dual therapies and using the same dosages in the triple therapy as in the dual therapy

However, it is important to note that nearly 40% of patients enrolled in the trial were already being treated with triple therapy, 70% were receiving a glucocorticoid, and patients with a history of asthma were not excluded. This means patients assigned to the dual therapy without glucocorticoids would have had an abrupt cessation of their glucocorticoid therapy, which may explain a rapid surge in exacerbations in the first month and the lower rate of exacerbations in the dual-therapy group that did include glucocorticoids. The choice of patients for the study could potentially have artificially inflated the observed effectiveness of triple therapy over dual bronchodilator treatment.

As such, we suggest clinicians stick with the GOLD 2017 recommendations that escalation to triple therapy only occur after maximization of bronchodilator treatment.

Dr. Samy Suissa (PhD) is with the Center for Clinical Epidemiology at Lady Davis Institute–Jewish General Hospital, and the departments of epidemiology and biostatistics and medicine at McGill University, Montreal. Dr. Jeffrey M. Drazen is editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine. These comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1716802 ). Dr. Suissa declared personal fees and grants from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work.

Triple therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) achieved reductions in moderate to severe exacerbations when compared with two kinds of dual therapy, in a study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial compared the outcomes of COPD patients using an inhaled therapy comprising a corticosteroid, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) with the outcomes of similar patients taking one of two other therapy combinations – a corticosteroid and a LABA, or a LABA and a LAMA. This trial – Informing the Pathway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) – included 10,355 patients with symptomatic COPD in 37 countries, according to David A. Lipson, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901).

The study randomized patients to 52 weeks of either triple inhaled therapy involving a once-daily combination of 100 mcg fluticasone furoate (a corticosteroid), 62.5 mcg of the LAMA umeclidinium and 25 mcg of the LABA vilanterol; or dual inhaled therapy involving either 100 mcg fluticasone furoate plus 25 mcg of vilanterol, or 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium plus 25 mcg of vilanterol.

After 1 year, the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations in the triple-therapy group was 0.91 per year, compared with 1.07 in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 1.21 in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. This translated to a 15% reduction with triple therapy compared with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol and a 25% reduction compared with vilanterol-umeclidinium (P less than .001 for both).

When the analysis was limited to severe exacerbations alone, the difference was significant only between the triple therapy, which GSK is marketing as Trelegy Ellipta, and the vilanterol-umeclidinium dual therapy.

Dr. Lipson, of GSK and the University of Pennsylvania, and his coauthors noted that their finding of a greater benefit with the glucocorticoid-containing dual-therapy compared with the LABA-LAMA vilanterol-umeclidinium combination contradicted the findings of the earlier FLAME trial. This was likely due to differences in patient populations and design, as all patients in the FLAME trial had a 1-month run-in treatment with the bronchodilator tiotropium, the researchers explained.

“Therefore any patients who would require an inhaled glucocorticoid may have had an increase in exacerbations and a decrease in lung function during the run-in period and would have been forced to leave the trial,” they wrote.

Patients with higher eosinophil levels seemed to do even better with triple therapy. In those with eosinophil levels of 150 cells per microliter or above, the annual rate of moderate to severe exacerbations was 0.95 with triple therapy, 1.08 with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol, and 1.39 with vilanterol-umeclidinium.

Triple therapy also was associated with a significantly longer time to first event and greater improvements in quality of life, compared with the dual therapies.

Overall, the adverse event profile of triple therapy was similar to that of dual therapy. Contrasting that finding were differences in the incidences of physician-diagnosed pneumonia between the treatment groups. Physician-diagnosed pneumonia was 53% higher among patients who received fluticasone furoate – either in dual or triple therapy combinations. Eight percent of patients in the triple therapy group experienced pneumonia, compared with 7% of patients in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 5% in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group.

All-cause mortality was significantly lower in patients who received the inhaled glucocorticoid, although the authors said this finding was “fragile” and needed further investigation.

The rate of discontinuation or withdrawal from the trial was 6% for the triple therapy group, 8% for the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group, and 9% for the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. The rates of serious adverse events in each group were 22%, 21%, and 23%, respectively.

At trial entry, 38% of patients were already receiving triple therapy and 29% were taking an inhaled glucocorticoid. The authors noted that any patients taking an inhaled glucocorticoid who were randomized to the vilanterol-umeclidinium group would have had to abruptly stop taking their inhaled glucocorticoids.

“It is unknown whether the abrupt discontinuation of inhaled glucocorticoids would have contributed to our finding of a lower rate of exacerbations in the inhaled glucocorticoid groups than in the LAMA-LABA group,” they wrote.

Fernando Martinez, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, said the study advanced the understanding of COPD management by addressing some key evidence gaps, in a statement issued by GSK.

“By comparing various combinations of effective medications in the same device the study clarifies which type of patient gains greatest benefit from each class of medicine,” Dr Martinez said in the statement. “As many patients experience frequent exacerbations or ‘flare ups,’ which can often result in hospitalization, these data will be highly relevant to patients and clinicians as they consider the optimal treatment.”

The study was funded by GSK, which manufactures Trelegy Ellipta triple therapy for COPD. Eight authors were employees of GSK and two were on advisory boards for the company. Seven authors declared funding from a range of pharmaceutical companies including GSK. One author had no conflicts of interest to declare.

SOURCE: Lipson D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901.

Triple therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) achieved reductions in moderate to severe exacerbations when compared with two kinds of dual therapy, in a study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial compared the outcomes of COPD patients using an inhaled therapy comprising a corticosteroid, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) with the outcomes of similar patients taking one of two other therapy combinations – a corticosteroid and a LABA, or a LABA and a LAMA. This trial – Informing the Pathway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) – included 10,355 patients with symptomatic COPD in 37 countries, according to David A. Lipson, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901).

The study randomized patients to 52 weeks of either triple inhaled therapy involving a once-daily combination of 100 mcg fluticasone furoate (a corticosteroid), 62.5 mcg of the LAMA umeclidinium and 25 mcg of the LABA vilanterol; or dual inhaled therapy involving either 100 mcg fluticasone furoate plus 25 mcg of vilanterol, or 62.5 mcg of umeclidinium plus 25 mcg of vilanterol.

After 1 year, the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations in the triple-therapy group was 0.91 per year, compared with 1.07 in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 1.21 in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. This translated to a 15% reduction with triple therapy compared with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol and a 25% reduction compared with vilanterol-umeclidinium (P less than .001 for both).

When the analysis was limited to severe exacerbations alone, the difference was significant only between the triple therapy, which GSK is marketing as Trelegy Ellipta, and the vilanterol-umeclidinium dual therapy.

Dr. Lipson, of GSK and the University of Pennsylvania, and his coauthors noted that their finding of a greater benefit with the glucocorticoid-containing dual-therapy compared with the LABA-LAMA vilanterol-umeclidinium combination contradicted the findings of the earlier FLAME trial. This was likely due to differences in patient populations and design, as all patients in the FLAME trial had a 1-month run-in treatment with the bronchodilator tiotropium, the researchers explained.

“Therefore any patients who would require an inhaled glucocorticoid may have had an increase in exacerbations and a decrease in lung function during the run-in period and would have been forced to leave the trial,” they wrote.

Patients with higher eosinophil levels seemed to do even better with triple therapy. In those with eosinophil levels of 150 cells per microliter or above, the annual rate of moderate to severe exacerbations was 0.95 with triple therapy, 1.08 with fluticasone furoate–vilanterol, and 1.39 with vilanterol-umeclidinium.

Triple therapy also was associated with a significantly longer time to first event and greater improvements in quality of life, compared with the dual therapies.

Overall, the adverse event profile of triple therapy was similar to that of dual therapy. Contrasting that finding were differences in the incidences of physician-diagnosed pneumonia between the treatment groups. Physician-diagnosed pneumonia was 53% higher among patients who received fluticasone furoate – either in dual or triple therapy combinations. Eight percent of patients in the triple therapy group experienced pneumonia, compared with 7% of patients in the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group and 5% in the vilanterol-umeclidinium group.

All-cause mortality was significantly lower in patients who received the inhaled glucocorticoid, although the authors said this finding was “fragile” and needed further investigation.

The rate of discontinuation or withdrawal from the trial was 6% for the triple therapy group, 8% for the fluticasone furoate–vilanterol group, and 9% for the vilanterol-umeclidinium group. The rates of serious adverse events in each group were 22%, 21%, and 23%, respectively.

At trial entry, 38% of patients were already receiving triple therapy and 29% were taking an inhaled glucocorticoid. The authors noted that any patients taking an inhaled glucocorticoid who were randomized to the vilanterol-umeclidinium group would have had to abruptly stop taking their inhaled glucocorticoids.

“It is unknown whether the abrupt discontinuation of inhaled glucocorticoids would have contributed to our finding of a lower rate of exacerbations in the inhaled glucocorticoid groups than in the LAMA-LABA group,” they wrote.

Fernando Martinez, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, said the study advanced the understanding of COPD management by addressing some key evidence gaps, in a statement issued by GSK.

“By comparing various combinations of effective medications in the same device the study clarifies which type of patient gains greatest benefit from each class of medicine,” Dr Martinez said in the statement. “As many patients experience frequent exacerbations or ‘flare ups,’ which can often result in hospitalization, these data will be highly relevant to patients and clinicians as they consider the optimal treatment.”

The study was funded by GSK, which manufactures Trelegy Ellipta triple therapy for COPD. Eight authors were employees of GSK and two were on advisory boards for the company. Seven authors declared funding from a range of pharmaceutical companies including GSK. One author had no conflicts of interest to declare.

SOURCE: Lipson D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Triple COPD therapy shows fewer exacerbations than does dual therapy.

Major finding: Triple COPD therapy achieves a 15%-25% greater reduction in exacerbations compared with dual therapy.

Study details: Randomized controlled trial of 10,355 patients with symptomatic COPD.

Disclosures: The study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which manufactures Trelegy Ellipta triple therapy for COPD. Eight authors were employees of GlaxoSmithKline and two were on advisory boards for the company. Seven authors declared funding from a range of pharmaceutical companies including GlaxoSmithKline. One author had no conflicts of interest to declare.

Source: Lipson D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901.

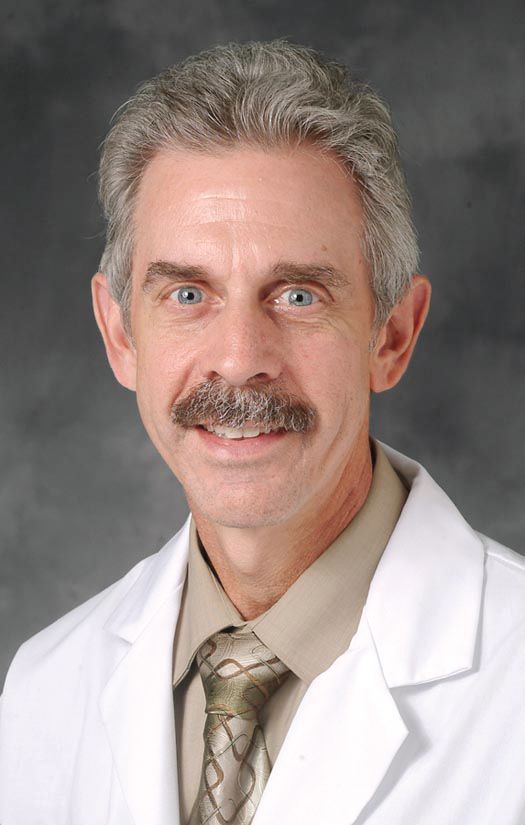

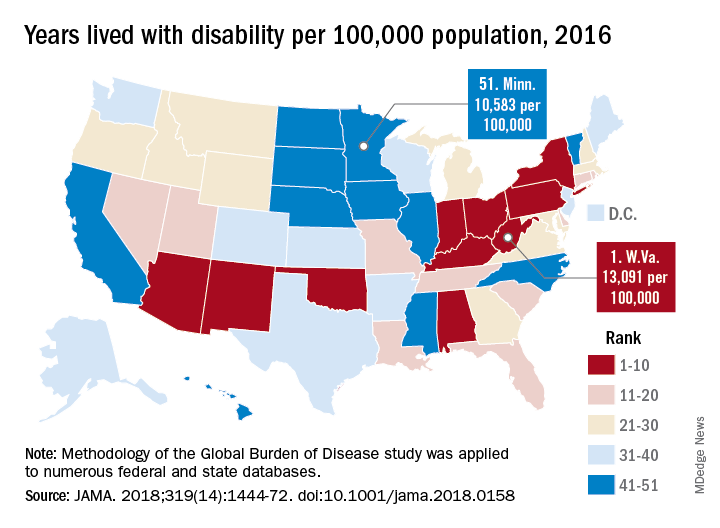

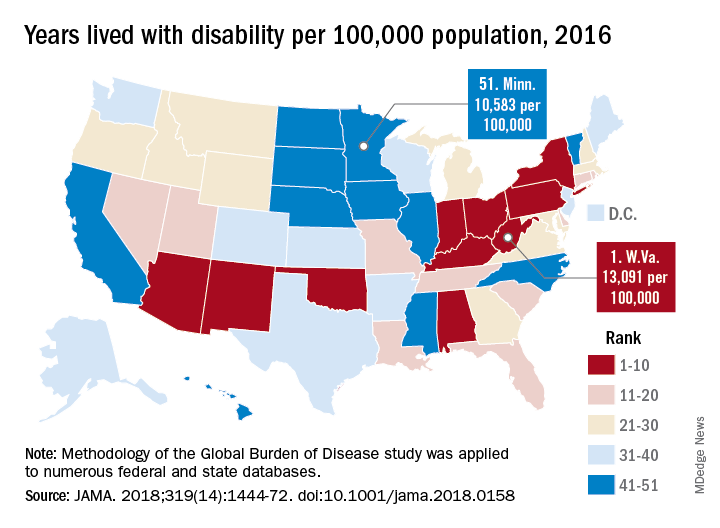

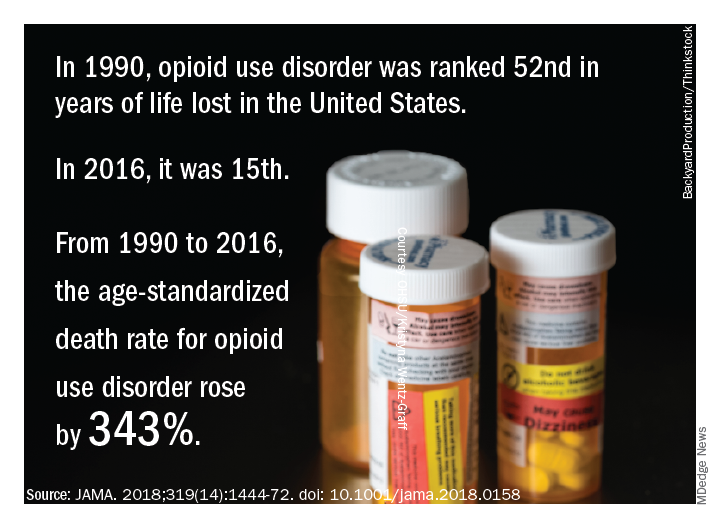

Life and health are not even across the U.S.

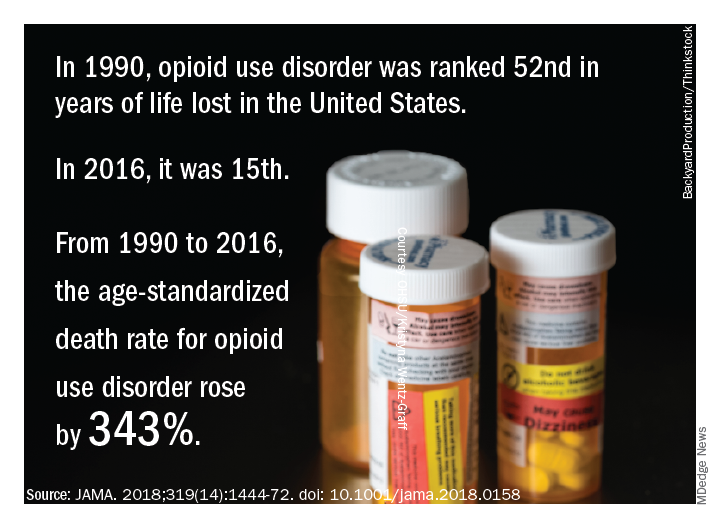

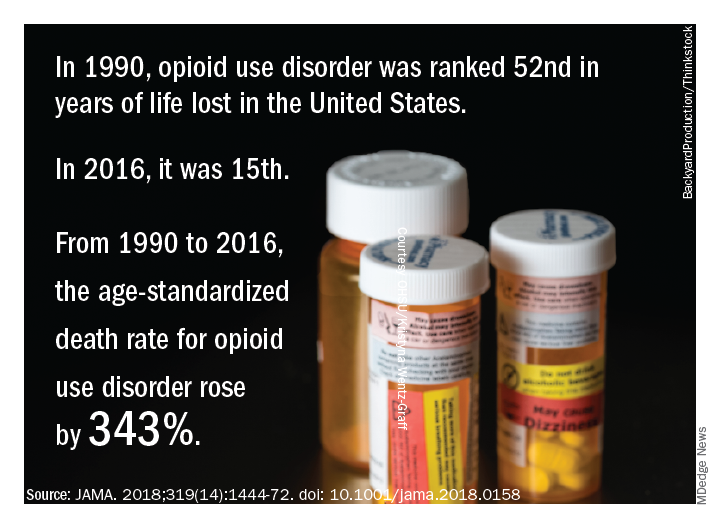

While U.S. death rates have declined overall, marked geographic disparities exist at the state level in burden of disease, injuries, and risk factors, according to a comprehensive analysis.

Life expectancy varies substantially, for example, ranging from a high of 81.3 years in Hawaii to a low of 74.7 years in Mississippi, according to results from the analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study (JAMA. 2018;319[14]:1444-72).

Previously decreasing death rates for adults have reversed in 19 states, according to the analysis, which covers the years 1990 to 2016.

Hardest hit were Kentucky, New Mexico, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wyoming, which had mortality increases of more than 10% among adults aged 20-55 years. Those increases were largely due to causes such as substance use disorders, self-harm, and cirrhosis, according to the US Burden of Disease Collaborators, who authored the report.

“These findings should be used to examine the causes of health variations and to plan, develop, and implement programs and policies to improve health overall and eliminate disparities in the United States,” the authors wrote.

Overall, U.S. death rates have declined from 745.2 per 100,000 persons in 1990 to 578.0 per 100,000 persons in 2016, according to the report.

Likewise, health outcomes throughout the United States have improved over time for some conditions, such as ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, and neonatal preterm complications, the report says.

However, those gains are offset by rising death rates due to drug-use disorders, chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and self-harm.

The three most important risk factors in the United States are high body mass index, smoking, and high fasting plasma glucose, the analysis showed. Of those risk factors, only smoking is decreasing, authors noted.

Many risk factors contributing to disparities in burden among states are amenable to medical treatment that emphasizes supportive behavioral and lifestyle changes, according to the authors.

“Expanding health coverage for certain conditions and medications should be considered and adopted to reduce burden,” they said.

Substance abuse disorders, cirrhosis, and self-harm, the causes of the mortality reversal in Kentucky, New Mexico, and other states, could be addressed via a wide range of interventions, according to the investigators.

Prevention programs could address the root causes of substance use and causes of relapse, while physicians can play a “major role” in addiction control through counseling of patients on pain control medication, they said.

Interventions to treat hepatitis C and decrease excessive alcohol consumption could help address cirrhosis, while for self-harm, the most promising approaches focus on restricting access to lethal means, they said, noting that a large proportion of U.S. suicides are due to firearms.

“While multiple strategies are available for dealing with these problems, they have not until very recently garnered attention,” investigators wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Some individual study collaborators reported disclosures related to Savient, Takeda, Crealta/Horizon, Regeneron, Allergan, and others.

SOURCE: The US Burden of Disease Collaborators. JAMA 2018;319(14):1444-72.

This report on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study data profoundly and powerfully illuminates U.S. health trends over time and by geography. There is much unfinished business for us, nationally and at the state level.

Clinicians and policy makers can use the rankings to evaluate why many individuals are still experiencing injury, disease, and deaths that are preventable; in doing so, the entire nation could move closely resemble a United States of health.

Clinicians could use the results to help guide patients through evidence-based disease prevention and early intervention, a strategy that has led to decreases in death due to cancer and cardiovascular disease over the past few decades.

At the same time, policy makers could use GBD 2016 results to reevaluate current national attitudes toward disease prevention.

Howard K. Koh, MD, MPH, is with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Anand K. Parekh, MD, MPH, is with the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. The comments above are derived from an editorial accompanying the report from the US Burden of Disease Collaborators ( JAMA. 2018;319[14]:1438-40 ). Dr. Koh and Dr. Parekh reported no conflicts of interest related to the editorial.

This report on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study data profoundly and powerfully illuminates U.S. health trends over time and by geography. There is much unfinished business for us, nationally and at the state level.

Clinicians and policy makers can use the rankings to evaluate why many individuals are still experiencing injury, disease, and deaths that are preventable; in doing so, the entire nation could move closely resemble a United States of health.

Clinicians could use the results to help guide patients through evidence-based disease prevention and early intervention, a strategy that has led to decreases in death due to cancer and cardiovascular disease over the past few decades.

At the same time, policy makers could use GBD 2016 results to reevaluate current national attitudes toward disease prevention.

Howard K. Koh, MD, MPH, is with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Anand K. Parekh, MD, MPH, is with the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. The comments above are derived from an editorial accompanying the report from the US Burden of Disease Collaborators ( JAMA. 2018;319[14]:1438-40 ). Dr. Koh and Dr. Parekh reported no conflicts of interest related to the editorial.

This report on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study data profoundly and powerfully illuminates U.S. health trends over time and by geography. There is much unfinished business for us, nationally and at the state level.

Clinicians and policy makers can use the rankings to evaluate why many individuals are still experiencing injury, disease, and deaths that are preventable; in doing so, the entire nation could move closely resemble a United States of health.

Clinicians could use the results to help guide patients through evidence-based disease prevention and early intervention, a strategy that has led to decreases in death due to cancer and cardiovascular disease over the past few decades.

At the same time, policy makers could use GBD 2016 results to reevaluate current national attitudes toward disease prevention.

Howard K. Koh, MD, MPH, is with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Anand K. Parekh, MD, MPH, is with the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. The comments above are derived from an editorial accompanying the report from the US Burden of Disease Collaborators ( JAMA. 2018;319[14]:1438-40 ). Dr. Koh and Dr. Parekh reported no conflicts of interest related to the editorial.

While U.S. death rates have declined overall, marked geographic disparities exist at the state level in burden of disease, injuries, and risk factors, according to a comprehensive analysis.

Life expectancy varies substantially, for example, ranging from a high of 81.3 years in Hawaii to a low of 74.7 years in Mississippi, according to results from the analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study (JAMA. 2018;319[14]:1444-72).

Previously decreasing death rates for adults have reversed in 19 states, according to the analysis, which covers the years 1990 to 2016.

Hardest hit were Kentucky, New Mexico, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wyoming, which had mortality increases of more than 10% among adults aged 20-55 years. Those increases were largely due to causes such as substance use disorders, self-harm, and cirrhosis, according to the US Burden of Disease Collaborators, who authored the report.

“These findings should be used to examine the causes of health variations and to plan, develop, and implement programs and policies to improve health overall and eliminate disparities in the United States,” the authors wrote.

Overall, U.S. death rates have declined from 745.2 per 100,000 persons in 1990 to 578.0 per 100,000 persons in 2016, according to the report.

Likewise, health outcomes throughout the United States have improved over time for some conditions, such as ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, and neonatal preterm complications, the report says.

However, those gains are offset by rising death rates due to drug-use disorders, chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and self-harm.

The three most important risk factors in the United States are high body mass index, smoking, and high fasting plasma glucose, the analysis showed. Of those risk factors, only smoking is decreasing, authors noted.

Many risk factors contributing to disparities in burden among states are amenable to medical treatment that emphasizes supportive behavioral and lifestyle changes, according to the authors.

“Expanding health coverage for certain conditions and medications should be considered and adopted to reduce burden,” they said.

Substance abuse disorders, cirrhosis, and self-harm, the causes of the mortality reversal in Kentucky, New Mexico, and other states, could be addressed via a wide range of interventions, according to the investigators.

Prevention programs could address the root causes of substance use and causes of relapse, while physicians can play a “major role” in addiction control through counseling of patients on pain control medication, they said.

Interventions to treat hepatitis C and decrease excessive alcohol consumption could help address cirrhosis, while for self-harm, the most promising approaches focus on restricting access to lethal means, they said, noting that a large proportion of U.S. suicides are due to firearms.

“While multiple strategies are available for dealing with these problems, they have not until very recently garnered attention,” investigators wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Some individual study collaborators reported disclosures related to Savient, Takeda, Crealta/Horizon, Regeneron, Allergan, and others.

SOURCE: The US Burden of Disease Collaborators. JAMA 2018;319(14):1444-72.

While U.S. death rates have declined overall, marked geographic disparities exist at the state level in burden of disease, injuries, and risk factors, according to a comprehensive analysis.

Life expectancy varies substantially, for example, ranging from a high of 81.3 years in Hawaii to a low of 74.7 years in Mississippi, according to results from the analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study (JAMA. 2018;319[14]:1444-72).

Previously decreasing death rates for adults have reversed in 19 states, according to the analysis, which covers the years 1990 to 2016.

Hardest hit were Kentucky, New Mexico, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wyoming, which had mortality increases of more than 10% among adults aged 20-55 years. Those increases were largely due to causes such as substance use disorders, self-harm, and cirrhosis, according to the US Burden of Disease Collaborators, who authored the report.

“These findings should be used to examine the causes of health variations and to plan, develop, and implement programs and policies to improve health overall and eliminate disparities in the United States,” the authors wrote.

Overall, U.S. death rates have declined from 745.2 per 100,000 persons in 1990 to 578.0 per 100,000 persons in 2016, according to the report.

Likewise, health outcomes throughout the United States have improved over time for some conditions, such as ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, and neonatal preterm complications, the report says.

However, those gains are offset by rising death rates due to drug-use disorders, chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and self-harm.

The three most important risk factors in the United States are high body mass index, smoking, and high fasting plasma glucose, the analysis showed. Of those risk factors, only smoking is decreasing, authors noted.

Many risk factors contributing to disparities in burden among states are amenable to medical treatment that emphasizes supportive behavioral and lifestyle changes, according to the authors.

“Expanding health coverage for certain conditions and medications should be considered and adopted to reduce burden,” they said.

Substance abuse disorders, cirrhosis, and self-harm, the causes of the mortality reversal in Kentucky, New Mexico, and other states, could be addressed via a wide range of interventions, according to the investigators.

Prevention programs could address the root causes of substance use and causes of relapse, while physicians can play a “major role” in addiction control through counseling of patients on pain control medication, they said.

Interventions to treat hepatitis C and decrease excessive alcohol consumption could help address cirrhosis, while for self-harm, the most promising approaches focus on restricting access to lethal means, they said, noting that a large proportion of U.S. suicides are due to firearms.

“While multiple strategies are available for dealing with these problems, they have not until very recently garnered attention,” investigators wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Some individual study collaborators reported disclosures related to Savient, Takeda, Crealta/Horizon, Regeneron, Allergan, and others.

SOURCE: The US Burden of Disease Collaborators. JAMA 2018;319(14):1444-72.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: While U.S. death rates have declined overall, marked geographic disparities exist at the state level in burden of disease, injuries, and risk factors.

Major finding: Life expectancy ranged from a high of 81.3 years in Hawaii to a low of 74.7 years in Mississippi, and previously decreasing death rates for adults have reversed in 19 states.

Study details: A U.S. state-level analysis of results from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study illustrating trends in diseases, injuries, risk factors, and deaths from 1990 to 2016.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Study authors reported disclosures related to Savient, Takeda, Crealta/Horizon, Regeneron, Allergan, and others.

Source: The US Burden of Disease Collaborators. JAMA 2018;319(14):1444-1472.

The outcomes of “GOLD 2017”

After the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease released updated recommendations for grading COPD patients’ level of disease in November of 2016, Imran Iftikhar, MD, tried to incorporate them into his practice, but he encountered problems.

For one thing, the new classification system, which became known as GOLD 2017, uncoupled spirometry results from the ABCD treatment algorithm. “I found it wasn’t really helping me in terms of prognostication or COPD management,” said Dr. Iftikhar, section chief of pulmonary and critical care at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Atlanta. “Although the purpose of the GOLD classification was not really meant for prognostication, most practicing physicians are frequently asked about prognosis by patients, and I am not sure if the 2017 reclassification really helps with that.”

The GOLD 2017 classification simplified the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging that was available from 2011 to 2015 from three variables (spirometry thresholds, exacerbation risk, and dyspnea scale) to two variables (exacerbation risk and dyspnea scale). In the 2017 report, authors of the new guidelines characterized forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) as “a poor predictor of disease status” and proposed that clinicians derive ABCD groups exclusively from patient symptoms and their exacerbations. FEV1 is an “important parameter at the population level” in predicting hospitalization and mortality, the authors wrote, but keeping results separate “acknowledges the limitations of FEV1 in making treatment decisions for individualized patient care and highlights the importance of patient symptoms and exacerbation risks in guiding therapies in COPD.”

According to Meilan Han, MD, MS, a member of the GOLD Science Committee, since release of the 2017 guidelines, “clinicians have indicated that they like the flexibility the system provides in separating spirometry, symptoms, and exacerbation risk as this more accurately reflects the heterogeneity we see in the COPD patient population.” Nevertheless, how this approach influences long-term outcomes remains unclear.

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, a pulmonologist with the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, described the GOLD 2017 criteria as “a good step forward” but said he wasn’t sure if the optimal or perfect tool exists for categorizing COPD patients’ level of disease.

“I think what we see is an effort to use all of these criteria to help us better treat our patients. I think ,” he said in an interview.

“All guidelines need to be modified as further research becomes available. I think that the frontiers of this area are going to be to incorporate new elements such as tobacco history, more emphasis on clinical signs and symptoms, and use of markers other than spirometry, such as eosinophil count, to categorize patients with COPD,” Dr. Ouellette added.

In an analysis of the GOLD 2017 criteria applied to 819 COPD patients in Spain and the United States, published online Nov. 3, 2017, in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Carlos Cabrera López, MD, and his colleagues concluded that the mortality risk was better predicted by the 2015 GOLD classification system than by the 2017 iteration (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.101164/rccm.201707-1363OC).

The distribution of Charlson index scores also changed. Whereas group D was higher than B in 2015, they became similar in the 2017 system. For her part, Dr. Han emphasized that the primary goal of the GOLD ABCD classification system is to categorize patients with respect to treatment groups. “Current therapy targets symptoms and exacerbations, which are the key current elements of the classification schema,” she said in an interview. “The results of the Cabrera Lopez analysis are not necessarily unexpected, as FEV1 is associated with mortality.”

In a prospective, multicenter analysis, Portuguese researchers compared the performance of GOLD 2011 and 2017 in terms of how 200 COPD patients were reclassified, the level of agreement between the two iterations, and the performance of each to predict future exacerbations (COPD. 2018 Feb;15[1]; 21-6). They found that about half of patients classified as GOLD D under the 2011 guidelines became classified as GOLD B when the 2017 version was used, and the extent of agreement between the two iterations was moderate (P less than .001). They also found that the two versions of the guidelines were equivalently effective at predicting exacerbations (69.7% vs. 67.6% in the 2011 and 2017 iterations, respectively). In addition, patients who met the criteria for a GOLD B grouping in the 2017 iteration exacerbated 17% more often and had a lower percent predicted post bronchodilator FEV1 than did those who met the criteria for a GOLD B classification under the 2011 guidelines.

Dr. Han, who is also an associate professor of medicine at the University of Michigan Hospital, acknowledged that GOLD 2017 has resulted in the reclassification of some previously group D patients as group B patients. “Our primary goal is to aid clinicians with the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD,” she said. “We look forward to additional data coming in from ongoing clinical trials that will provide longer term data to further refine treatment algorithms.”

In a recent study of more than 33,000 Danish patients older than age 30 with COPD, researchers led by Anne Gedebjerg, MD, found that the GOLD 2017 ABCD classification did not predict all-cause and respiratory mortality more accurately than previous GOLD iterations from 2007 and 2011. Area under the curve for all-cause mortality was 0.61 for GOLD 2007, 0.61 for GOLD 2011, and 0.63 for GOLD 2017, while the area under the curve for respiratory mortality was 0.64 for GOLD 2007, 0.63 for GOLD 2011, and 0.65 for GOLD 2017 (Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6[3]:204-12).

However, when the spirometric stages 1-4 were combined with the A to D groupings based on symptoms and exacerbations, the 2017 classification predicted mortality with greater accuracy, compared with previous iterations (P less than .0001). “My practice is very much like this paper,” Dr. Iftikhar said. “I use both the spirometric grade and the ABCD grouping to specify which ‘group’ and ‘grade’ my patient belongs to. I think future investigators need to combine ABCD with spirometry classification to see how we can improve the classification system.”

In a commentary published in the same issue of the Lancet Respiratory Medicine as the large Danish study, Joan B. Soriano, MD, PhD, wrote that the 2011 GOLD guideline’s collapse of four spirometric thresholds (greater than 80%, 50%-80%, 30%-50%, and less than 30%) into just two (greater than 50% or 50% or less) “reduced the system’s ability to inform and predict mortality from the short term up to 10 years” (Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6[3]:165-6).

Lung function remains the best available biomarker for life expectancy in both patients with COPD and the general population,” wrote Dr. Soriano, a respiratory medicine researcher based in Madrid, Spain.

Additional important outcomes

Dr. Ouellette noted that while mortality is an important outcome for COPD patients, it’s not the only outcome of interest. “In addition to [trying to] help people live longer, which is certainly a desirable goal, we also want to make people be able to be more functional during their life, have fewer hospitalizations, and have less of a need of other types of supportive medical care for worsening of their disease,” he said. “The fact that the current guidelines don’t improve mortality more than the previous ones may not be a negative thing. It may tell us that the previous guidelines already did a pretty good job of helping us to improve mortality.”

Dr. Ouellette was quick to add that none of inhaled drugs currently available to treat COPD have been conclusively shown to improve mortality. “The only things we know that improve mortality for COPD patients are quitting smoking and using oxygen if a patient meets predefined goals for oxygen,” he said. “So the fact that GOLD criteria doesn’t improve mortality shouldn’t make us think that it’s not a useful tool. We already know that the medicines may not help people live longer.”

Dr. Han pointed out that spirometry “is still used to further clarify the choice of therapy recommended based on the nature and degree of airflow obstruction in light of severity of patient symptoms. The data are still designed to be used in conjunction to personalize therapy for patients.”

She added that the GOLD Science Committee “welcomes additional data analyses so that future recommendations can be further refined.”

Dr. Han disclosed that she has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. She has also received in-kind research support from Novartis and Sunovion.

Dr. Iftikhar reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Ouellette is a member of CHEST® Physician’s editorial advisory board. He disclosed being part of a federally funded study being carried out by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

There was no industry involvement in the GOLD 2017 report, but many of its authors and board members had pharmaceutical company ties, and GOLD’s treatment advice relies on data from industry-sponsored studies.

After the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease released updated recommendations for grading COPD patients’ level of disease in November of 2016, Imran Iftikhar, MD, tried to incorporate them into his practice, but he encountered problems.

For one thing, the new classification system, which became known as GOLD 2017, uncoupled spirometry results from the ABCD treatment algorithm. “I found it wasn’t really helping me in terms of prognostication or COPD management,” said Dr. Iftikhar, section chief of pulmonary and critical care at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Atlanta. “Although the purpose of the GOLD classification was not really meant for prognostication, most practicing physicians are frequently asked about prognosis by patients, and I am not sure if the 2017 reclassification really helps with that.”

The GOLD 2017 classification simplified the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging that was available from 2011 to 2015 from three variables (spirometry thresholds, exacerbation risk, and dyspnea scale) to two variables (exacerbation risk and dyspnea scale). In the 2017 report, authors of the new guidelines characterized forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) as “a poor predictor of disease status” and proposed that clinicians derive ABCD groups exclusively from patient symptoms and their exacerbations. FEV1 is an “important parameter at the population level” in predicting hospitalization and mortality, the authors wrote, but keeping results separate “acknowledges the limitations of FEV1 in making treatment decisions for individualized patient care and highlights the importance of patient symptoms and exacerbation risks in guiding therapies in COPD.”

According to Meilan Han, MD, MS, a member of the GOLD Science Committee, since release of the 2017 guidelines, “clinicians have indicated that they like the flexibility the system provides in separating spirometry, symptoms, and exacerbation risk as this more accurately reflects the heterogeneity we see in the COPD patient population.” Nevertheless, how this approach influences long-term outcomes remains unclear.

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, a pulmonologist with the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, described the GOLD 2017 criteria as “a good step forward” but said he wasn’t sure if the optimal or perfect tool exists for categorizing COPD patients’ level of disease.

“I think what we see is an effort to use all of these criteria to help us better treat our patients. I think ,” he said in an interview.

“All guidelines need to be modified as further research becomes available. I think that the frontiers of this area are going to be to incorporate new elements such as tobacco history, more emphasis on clinical signs and symptoms, and use of markers other than spirometry, such as eosinophil count, to categorize patients with COPD,” Dr. Ouellette added.

In an analysis of the GOLD 2017 criteria applied to 819 COPD patients in Spain and the United States, published online Nov. 3, 2017, in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Carlos Cabrera López, MD, and his colleagues concluded that the mortality risk was better predicted by the 2015 GOLD classification system than by the 2017 iteration (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.101164/rccm.201707-1363OC).

The distribution of Charlson index scores also changed. Whereas group D was higher than B in 2015, they became similar in the 2017 system. For her part, Dr. Han emphasized that the primary goal of the GOLD ABCD classification system is to categorize patients with respect to treatment groups. “Current therapy targets symptoms and exacerbations, which are the key current elements of the classification schema,” she said in an interview. “The results of the Cabrera Lopez analysis are not necessarily unexpected, as FEV1 is associated with mortality.”

In a prospective, multicenter analysis, Portuguese researchers compared the performance of GOLD 2011 and 2017 in terms of how 200 COPD patients were reclassified, the level of agreement between the two iterations, and the performance of each to predict future exacerbations (COPD. 2018 Feb;15[1]; 21-6). They found that about half of patients classified as GOLD D under the 2011 guidelines became classified as GOLD B when the 2017 version was used, and the extent of agreement between the two iterations was moderate (P less than .001). They also found that the two versions of the guidelines were equivalently effective at predicting exacerbations (69.7% vs. 67.6% in the 2011 and 2017 iterations, respectively). In addition, patients who met the criteria for a GOLD B grouping in the 2017 iteration exacerbated 17% more often and had a lower percent predicted post bronchodilator FEV1 than did those who met the criteria for a GOLD B classification under the 2011 guidelines.

Dr. Han, who is also an associate professor of medicine at the University of Michigan Hospital, acknowledged that GOLD 2017 has resulted in the reclassification of some previously group D patients as group B patients. “Our primary goal is to aid clinicians with the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD,” she said. “We look forward to additional data coming in from ongoing clinical trials that will provide longer term data to further refine treatment algorithms.”

In a recent study of more than 33,000 Danish patients older than age 30 with COPD, researchers led by Anne Gedebjerg, MD, found that the GOLD 2017 ABCD classification did not predict all-cause and respiratory mortality more accurately than previous GOLD iterations from 2007 and 2011. Area under the curve for all-cause mortality was 0.61 for GOLD 2007, 0.61 for GOLD 2011, and 0.63 for GOLD 2017, while the area under the curve for respiratory mortality was 0.64 for GOLD 2007, 0.63 for GOLD 2011, and 0.65 for GOLD 2017 (Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6[3]:204-12).

However, when the spirometric stages 1-4 were combined with the A to D groupings based on symptoms and exacerbations, the 2017 classification predicted mortality with greater accuracy, compared with previous iterations (P less than .0001). “My practice is very much like this paper,” Dr. Iftikhar said. “I use both the spirometric grade and the ABCD grouping to specify which ‘group’ and ‘grade’ my patient belongs to. I think future investigators need to combine ABCD with spirometry classification to see how we can improve the classification system.”

In a commentary published in the same issue of the Lancet Respiratory Medicine as the large Danish study, Joan B. Soriano, MD, PhD, wrote that the 2011 GOLD guideline’s collapse of four spirometric thresholds (greater than 80%, 50%-80%, 30%-50%, and less than 30%) into just two (greater than 50% or 50% or less) “reduced the system’s ability to inform and predict mortality from the short term up to 10 years” (Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6[3]:165-6).

Lung function remains the best available biomarker for life expectancy in both patients with COPD and the general population,” wrote Dr. Soriano, a respiratory medicine researcher based in Madrid, Spain.

Additional important outcomes

Dr. Ouellette noted that while mortality is an important outcome for COPD patients, it’s not the only outcome of interest. “In addition to [trying to] help people live longer, which is certainly a desirable goal, we also want to make people be able to be more functional during their life, have fewer hospitalizations, and have less of a need of other types of supportive medical care for worsening of their disease,” he said. “The fact that the current guidelines don’t improve mortality more than the previous ones may not be a negative thing. It may tell us that the previous guidelines already did a pretty good job of helping us to improve mortality.”

Dr. Ouellette was quick to add that none of inhaled drugs currently available to treat COPD have been conclusively shown to improve mortality. “The only things we know that improve mortality for COPD patients are quitting smoking and using oxygen if a patient meets predefined goals for oxygen,” he said. “So the fact that GOLD criteria doesn’t improve mortality shouldn’t make us think that it’s not a useful tool. We already know that the medicines may not help people live longer.”

Dr. Han pointed out that spirometry “is still used to further clarify the choice of therapy recommended based on the nature and degree of airflow obstruction in light of severity of patient symptoms. The data are still designed to be used in conjunction to personalize therapy for patients.”

She added that the GOLD Science Committee “welcomes additional data analyses so that future recommendations can be further refined.”

Dr. Han disclosed that she has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. She has also received in-kind research support from Novartis and Sunovion.

Dr. Iftikhar reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Ouellette is a member of CHEST® Physician’s editorial advisory board. He disclosed being part of a federally funded study being carried out by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

There was no industry involvement in the GOLD 2017 report, but many of its authors and board members had pharmaceutical company ties, and GOLD’s treatment advice relies on data from industry-sponsored studies.

After the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease released updated recommendations for grading COPD patients’ level of disease in November of 2016, Imran Iftikhar, MD, tried to incorporate them into his practice, but he encountered problems.

For one thing, the new classification system, which became known as GOLD 2017, uncoupled spirometry results from the ABCD treatment algorithm. “I found it wasn’t really helping me in terms of prognostication or COPD management,” said Dr. Iftikhar, section chief of pulmonary and critical care at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Atlanta. “Although the purpose of the GOLD classification was not really meant for prognostication, most practicing physicians are frequently asked about prognosis by patients, and I am not sure if the 2017 reclassification really helps with that.”

The GOLD 2017 classification simplified the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging that was available from 2011 to 2015 from three variables (spirometry thresholds, exacerbation risk, and dyspnea scale) to two variables (exacerbation risk and dyspnea scale). In the 2017 report, authors of the new guidelines characterized forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) as “a poor predictor of disease status” and proposed that clinicians derive ABCD groups exclusively from patient symptoms and their exacerbations. FEV1 is an “important parameter at the population level” in predicting hospitalization and mortality, the authors wrote, but keeping results separate “acknowledges the limitations of FEV1 in making treatment decisions for individualized patient care and highlights the importance of patient symptoms and exacerbation risks in guiding therapies in COPD.”

According to Meilan Han, MD, MS, a member of the GOLD Science Committee, since release of the 2017 guidelines, “clinicians have indicated that they like the flexibility the system provides in separating spirometry, symptoms, and exacerbation risk as this more accurately reflects the heterogeneity we see in the COPD patient population.” Nevertheless, how this approach influences long-term outcomes remains unclear.

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, a pulmonologist with the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, described the GOLD 2017 criteria as “a good step forward” but said he wasn’t sure if the optimal or perfect tool exists for categorizing COPD patients’ level of disease.

“I think what we see is an effort to use all of these criteria to help us better treat our patients. I think ,” he said in an interview.

“All guidelines need to be modified as further research becomes available. I think that the frontiers of this area are going to be to incorporate new elements such as tobacco history, more emphasis on clinical signs and symptoms, and use of markers other than spirometry, such as eosinophil count, to categorize patients with COPD,” Dr. Ouellette added.

In an analysis of the GOLD 2017 criteria applied to 819 COPD patients in Spain and the United States, published online Nov. 3, 2017, in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Carlos Cabrera López, MD, and his colleagues concluded that the mortality risk was better predicted by the 2015 GOLD classification system than by the 2017 iteration (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.101164/rccm.201707-1363OC).

The distribution of Charlson index scores also changed. Whereas group D was higher than B in 2015, they became similar in the 2017 system. For her part, Dr. Han emphasized that the primary goal of the GOLD ABCD classification system is to categorize patients with respect to treatment groups. “Current therapy targets symptoms and exacerbations, which are the key current elements of the classification schema,” she said in an interview. “The results of the Cabrera Lopez analysis are not necessarily unexpected, as FEV1 is associated with mortality.”

In a prospective, multicenter analysis, Portuguese researchers compared the performance of GOLD 2011 and 2017 in terms of how 200 COPD patients were reclassified, the level of agreement between the two iterations, and the performance of each to predict future exacerbations (COPD. 2018 Feb;15[1]; 21-6). They found that about half of patients classified as GOLD D under the 2011 guidelines became classified as GOLD B when the 2017 version was used, and the extent of agreement between the two iterations was moderate (P less than .001). They also found that the two versions of the guidelines were equivalently effective at predicting exacerbations (69.7% vs. 67.6% in the 2011 and 2017 iterations, respectively). In addition, patients who met the criteria for a GOLD B grouping in the 2017 iteration exacerbated 17% more often and had a lower percent predicted post bronchodilator FEV1 than did those who met the criteria for a GOLD B classification under the 2011 guidelines.

Dr. Han, who is also an associate professor of medicine at the University of Michigan Hospital, acknowledged that GOLD 2017 has resulted in the reclassification of some previously group D patients as group B patients. “Our primary goal is to aid clinicians with the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD,” she said. “We look forward to additional data coming in from ongoing clinical trials that will provide longer term data to further refine treatment algorithms.”

In a recent study of more than 33,000 Danish patients older than age 30 with COPD, researchers led by Anne Gedebjerg, MD, found that the GOLD 2017 ABCD classification did not predict all-cause and respiratory mortality more accurately than previous GOLD iterations from 2007 and 2011. Area under the curve for all-cause mortality was 0.61 for GOLD 2007, 0.61 for GOLD 2011, and 0.63 for GOLD 2017, while the area under the curve for respiratory mortality was 0.64 for GOLD 2007, 0.63 for GOLD 2011, and 0.65 for GOLD 2017 (Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6[3]:204-12).

However, when the spirometric stages 1-4 were combined with the A to D groupings based on symptoms and exacerbations, the 2017 classification predicted mortality with greater accuracy, compared with previous iterations (P less than .0001). “My practice is very much like this paper,” Dr. Iftikhar said. “I use both the spirometric grade and the ABCD grouping to specify which ‘group’ and ‘grade’ my patient belongs to. I think future investigators need to combine ABCD with spirometry classification to see how we can improve the classification system.”

In a commentary published in the same issue of the Lancet Respiratory Medicine as the large Danish study, Joan B. Soriano, MD, PhD, wrote that the 2011 GOLD guideline’s collapse of four spirometric thresholds (greater than 80%, 50%-80%, 30%-50%, and less than 30%) into just two (greater than 50% or 50% or less) “reduced the system’s ability to inform and predict mortality from the short term up to 10 years” (Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6[3]:165-6).

Lung function remains the best available biomarker for life expectancy in both patients with COPD and the general population,” wrote Dr. Soriano, a respiratory medicine researcher based in Madrid, Spain.

Additional important outcomes

Dr. Ouellette noted that while mortality is an important outcome for COPD patients, it’s not the only outcome of interest. “In addition to [trying to] help people live longer, which is certainly a desirable goal, we also want to make people be able to be more functional during their life, have fewer hospitalizations, and have less of a need of other types of supportive medical care for worsening of their disease,” he said. “The fact that the current guidelines don’t improve mortality more than the previous ones may not be a negative thing. It may tell us that the previous guidelines already did a pretty good job of helping us to improve mortality.”

Dr. Ouellette was quick to add that none of inhaled drugs currently available to treat COPD have been conclusively shown to improve mortality. “The only things we know that improve mortality for COPD patients are quitting smoking and using oxygen if a patient meets predefined goals for oxygen,” he said. “So the fact that GOLD criteria doesn’t improve mortality shouldn’t make us think that it’s not a useful tool. We already know that the medicines may not help people live longer.”

Dr. Han pointed out that spirometry “is still used to further clarify the choice of therapy recommended based on the nature and degree of airflow obstruction in light of severity of patient symptoms. The data are still designed to be used in conjunction to personalize therapy for patients.”

She added that the GOLD Science Committee “welcomes additional data analyses so that future recommendations can be further refined.”

Dr. Han disclosed that she has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. She has also received in-kind research support from Novartis and Sunovion.

Dr. Iftikhar reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Ouellette is a member of CHEST® Physician’s editorial advisory board. He disclosed being part of a federally funded study being carried out by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

There was no industry involvement in the GOLD 2017 report, but many of its authors and board members had pharmaceutical company ties, and GOLD’s treatment advice relies on data from industry-sponsored studies.

Good definitions, research lacking for COPD-asthma overlap

ORLANDO – to give clinicians data they can actually use.

The topic is even more pressing given the growing interest and research into biological treatments for asthma and consideration of their possible use in COPD, experts said at the joint congress of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the World Asthma Organization. Their remarks came in what was ostensibly a “debate” on whether ACOS is a distinct entity requiring special treatment but largely turned into a discussion about gaps in knowledge on the topic.

“The problem here is that it has not been defined in a way that everyone agrees on – that does create a problem because, if there’s no consensus on the diagnostic criteria, then it may be difficult to study this overlap,” said Donald Tashkin, MD, director of the pulmonary function laboratories at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Because there is no agreement on how to diagnose ACOS, it hasn’t been studied with respect to its responsiveness to different treatment options.”R. Stokes Peebles Jr., MD, professor of allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said that, although the number of published articles on ACOS has skyrocketed over the last several years, review articles have outnumbered original research articles.

There is disagreement in published definitions: One set of definitions includes a criterion of fractional exhaled nitric oxide not seen in any other definitions, whereas some other definitions require a history of smoking while others don’t, he said.

“How does one manage a disease without a definition and without clinical studies? It’s impossible for me to know,” Dr. Peebles said.

Jeffrey Drazen, MD, the Distinguished Parker B. Francis Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, also lamented the polar nature of the research.

“We all treat patients in the middle, everybody does, all the time – and we would love more guidance,” he said. “One of the reasons the number of articles has gone up is that there have been lots of case definitions. But we can’t get consensus. So who do we have to bring to the table to get a consensus definition so we can get the funding we need from the drug companies or governmental bodies to do the research that we all want?”

Dr. Tashkin said the way forward could be to draw on the points of consensus that do exist on certain criteria.

Dr. Peebles said an international panel is needed to draw up a consensus guideline, with the panel including both pulmonologists and allergists – “people experienced with clinical trials, who take care of a lot of patients.”

ORLANDO – to give clinicians data they can actually use.

The topic is even more pressing given the growing interest and research into biological treatments for asthma and consideration of their possible use in COPD, experts said at the joint congress of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the World Asthma Organization. Their remarks came in what was ostensibly a “debate” on whether ACOS is a distinct entity requiring special treatment but largely turned into a discussion about gaps in knowledge on the topic.

“The problem here is that it has not been defined in a way that everyone agrees on – that does create a problem because, if there’s no consensus on the diagnostic criteria, then it may be difficult to study this overlap,” said Donald Tashkin, MD, director of the pulmonary function laboratories at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Because there is no agreement on how to diagnose ACOS, it hasn’t been studied with respect to its responsiveness to different treatment options.”R. Stokes Peebles Jr., MD, professor of allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said that, although the number of published articles on ACOS has skyrocketed over the last several years, review articles have outnumbered original research articles.