User login

CDC updates Zika recommendations on preventing sex transmission

Federal health officials are advising men who have possibly been exposed to Zika virus to practice safe sex and delay plans for conception for at least 6 months after exposure.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its recommendations for preventing sexual transmission of the Zika virus and its preconception guidance, extending the time frame that men should abstain from unprotected sex to prevent transmission.

Previously, only symptomatic men were advised to wait 6 months before trying to conceive a child, while asymptomatic men had to wait only 8 weeks from last possible exposure. Now, men who have been exposed to the virus should either abstain from sex or use a condom to prevent sexual transmission of the disease for at least 6 months, even if they are asymptomatic. Men who are trying to have a child with their partner should also wait at least 6 months.

For now, recommendations for women have not been changed. Women who have been exposed to Zika virus should wait at least 8 weeks after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible exposure to the virus before attempting to conceive. Women who do not plan to become pregnant but live in, or travel to, Zika-endemic regions should either abstain from sex or use the best possible protection available to them (MMWR. 2016 Sep 30. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6539e1).

“Two new reports describe one presumed and one more definitive case of sexual transmission from men with asymptomatic Zika virus infection to female sex partners,” Emily E. Peterson, MD, of the CDC’s Zika response team, and her colleagues wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “Among reported cases of sexually transmitted Zika virus infection, the longest reported period between sexual contact that might have transmitted Zika virus and symptom onset was 32-41 days (based on an incubation period of 3-12 days).”

Zika virus can be transmitted through either vaginal, anal, or oral sexual intercourse. While Zika virus RNA decreases over time after the infection passes, it can linger in semen for as long as 188 days after symptom onset, according to the CDC.

For nonpregnant women, Zika virus RNA has been detected in serum for up to 13 days post-onset of symptoms, and for 58 days in whole blood samples. For pregnant women, it can be detected in serum for as long as 10 weeks after the onset of symptoms.

“Detection of Zika virus RNA in blood might not indicate the presence of infectious virus, and thus the potential risk for maternal-fetal Zika virus transmission periconceptionally is unknown,” the researchers wrote.

Federal health officials are advising men who have possibly been exposed to Zika virus to practice safe sex and delay plans for conception for at least 6 months after exposure.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its recommendations for preventing sexual transmission of the Zika virus and its preconception guidance, extending the time frame that men should abstain from unprotected sex to prevent transmission.

Previously, only symptomatic men were advised to wait 6 months before trying to conceive a child, while asymptomatic men had to wait only 8 weeks from last possible exposure. Now, men who have been exposed to the virus should either abstain from sex or use a condom to prevent sexual transmission of the disease for at least 6 months, even if they are asymptomatic. Men who are trying to have a child with their partner should also wait at least 6 months.

For now, recommendations for women have not been changed. Women who have been exposed to Zika virus should wait at least 8 weeks after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible exposure to the virus before attempting to conceive. Women who do not plan to become pregnant but live in, or travel to, Zika-endemic regions should either abstain from sex or use the best possible protection available to them (MMWR. 2016 Sep 30. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6539e1).

“Two new reports describe one presumed and one more definitive case of sexual transmission from men with asymptomatic Zika virus infection to female sex partners,” Emily E. Peterson, MD, of the CDC’s Zika response team, and her colleagues wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “Among reported cases of sexually transmitted Zika virus infection, the longest reported period between sexual contact that might have transmitted Zika virus and symptom onset was 32-41 days (based on an incubation period of 3-12 days).”

Zika virus can be transmitted through either vaginal, anal, or oral sexual intercourse. While Zika virus RNA decreases over time after the infection passes, it can linger in semen for as long as 188 days after symptom onset, according to the CDC.

For nonpregnant women, Zika virus RNA has been detected in serum for up to 13 days post-onset of symptoms, and for 58 days in whole blood samples. For pregnant women, it can be detected in serum for as long as 10 weeks after the onset of symptoms.

“Detection of Zika virus RNA in blood might not indicate the presence of infectious virus, and thus the potential risk for maternal-fetal Zika virus transmission periconceptionally is unknown,” the researchers wrote.

Federal health officials are advising men who have possibly been exposed to Zika virus to practice safe sex and delay plans for conception for at least 6 months after exposure.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its recommendations for preventing sexual transmission of the Zika virus and its preconception guidance, extending the time frame that men should abstain from unprotected sex to prevent transmission.

Previously, only symptomatic men were advised to wait 6 months before trying to conceive a child, while asymptomatic men had to wait only 8 weeks from last possible exposure. Now, men who have been exposed to the virus should either abstain from sex or use a condom to prevent sexual transmission of the disease for at least 6 months, even if they are asymptomatic. Men who are trying to have a child with their partner should also wait at least 6 months.

For now, recommendations for women have not been changed. Women who have been exposed to Zika virus should wait at least 8 weeks after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible exposure to the virus before attempting to conceive. Women who do not plan to become pregnant but live in, or travel to, Zika-endemic regions should either abstain from sex or use the best possible protection available to them (MMWR. 2016 Sep 30. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6539e1).

“Two new reports describe one presumed and one more definitive case of sexual transmission from men with asymptomatic Zika virus infection to female sex partners,” Emily E. Peterson, MD, of the CDC’s Zika response team, and her colleagues wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “Among reported cases of sexually transmitted Zika virus infection, the longest reported period between sexual contact that might have transmitted Zika virus and symptom onset was 32-41 days (based on an incubation period of 3-12 days).”

Zika virus can be transmitted through either vaginal, anal, or oral sexual intercourse. While Zika virus RNA decreases over time after the infection passes, it can linger in semen for as long as 188 days after symptom onset, according to the CDC.

For nonpregnant women, Zika virus RNA has been detected in serum for up to 13 days post-onset of symptoms, and for 58 days in whole blood samples. For pregnant women, it can be detected in serum for as long as 10 weeks after the onset of symptoms.

“Detection of Zika virus RNA in blood might not indicate the presence of infectious virus, and thus the potential risk for maternal-fetal Zika virus transmission periconceptionally is unknown,” the researchers wrote.

FROM MMWR

Postnatally acquired Zika infection in children usually mild

The clinical course of postnatally acquired Zika virus disease in children younger than 18 years is mild and rarely results in severe illness or death, reported Alyson Goodman, MD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta.

There were a total of 158 confirmed or probable postnatally acquired Zika virus disease cases among children younger than 18 years reported to the CDC in the United States between January 2015 and July 2016, wrote researchers in a case series that described the epidemiology, clinical findings, and outcomes of the cases (MMWR. 2016 Sep 30;65:1-4).

The cases were reported in 30 d ifferent states, and the states with the highest numbers of reported cases were Florida (23%), New York (11%), and California (9%). All patients acquired Zika virus infections during travel to a location where mosquito-borne transmission had been documented, according to researchers.

The median patient age was 14 years, the majority of the patients were female (56%), and five patients were pregnant.

Of Zika’s four primary clinical signs and symptoms, 82% of the pediatric population had a rash, 55% had a fever, 29% had conjunctivitis, and 28% had arthralgia, with 70% of the children presenting with two or more of these symptoms.

Only two children were hospitalized because of their infections. No children were reported to have meningitis, encephalitis, or Guillain-Barré syndrome, and no patients with Zika virus infection died, researchers reported.

This data “corroborates previously published reports suggesting that the clinical course of Zika virus disease is typically mild in children, as it is in adults,” Dr. Goodman and her associates wrote.

Severe disease and death in children with postnatally acquired Zika virus infection are rare, the researchers pointed out, but they encouraged physicians to consider a Zika virus disease diagnosis for children with the four common symptoms and who reside in or traveled to an area with active Zika virus transmission. All Zika virus disease cases should be reported to state health departments.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

The clinical course of postnatally acquired Zika virus disease in children younger than 18 years is mild and rarely results in severe illness or death, reported Alyson Goodman, MD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta.

There were a total of 158 confirmed or probable postnatally acquired Zika virus disease cases among children younger than 18 years reported to the CDC in the United States between January 2015 and July 2016, wrote researchers in a case series that described the epidemiology, clinical findings, and outcomes of the cases (MMWR. 2016 Sep 30;65:1-4).

The cases were reported in 30 d ifferent states, and the states with the highest numbers of reported cases were Florida (23%), New York (11%), and California (9%). All patients acquired Zika virus infections during travel to a location where mosquito-borne transmission had been documented, according to researchers.

The median patient age was 14 years, the majority of the patients were female (56%), and five patients were pregnant.

Of Zika’s four primary clinical signs and symptoms, 82% of the pediatric population had a rash, 55% had a fever, 29% had conjunctivitis, and 28% had arthralgia, with 70% of the children presenting with two or more of these symptoms.

Only two children were hospitalized because of their infections. No children were reported to have meningitis, encephalitis, or Guillain-Barré syndrome, and no patients with Zika virus infection died, researchers reported.

This data “corroborates previously published reports suggesting that the clinical course of Zika virus disease is typically mild in children, as it is in adults,” Dr. Goodman and her associates wrote.

Severe disease and death in children with postnatally acquired Zika virus infection are rare, the researchers pointed out, but they encouraged physicians to consider a Zika virus disease diagnosis for children with the four common symptoms and who reside in or traveled to an area with active Zika virus transmission. All Zika virus disease cases should be reported to state health departments.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

The clinical course of postnatally acquired Zika virus disease in children younger than 18 years is mild and rarely results in severe illness or death, reported Alyson Goodman, MD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta.

There were a total of 158 confirmed or probable postnatally acquired Zika virus disease cases among children younger than 18 years reported to the CDC in the United States between January 2015 and July 2016, wrote researchers in a case series that described the epidemiology, clinical findings, and outcomes of the cases (MMWR. 2016 Sep 30;65:1-4).

The cases were reported in 30 d ifferent states, and the states with the highest numbers of reported cases were Florida (23%), New York (11%), and California (9%). All patients acquired Zika virus infections during travel to a location where mosquito-borne transmission had been documented, according to researchers.

The median patient age was 14 years, the majority of the patients were female (56%), and five patients were pregnant.

Of Zika’s four primary clinical signs and symptoms, 82% of the pediatric population had a rash, 55% had a fever, 29% had conjunctivitis, and 28% had arthralgia, with 70% of the children presenting with two or more of these symptoms.

Only two children were hospitalized because of their infections. No children were reported to have meningitis, encephalitis, or Guillain-Barré syndrome, and no patients with Zika virus infection died, researchers reported.

This data “corroborates previously published reports suggesting that the clinical course of Zika virus disease is typically mild in children, as it is in adults,” Dr. Goodman and her associates wrote.

Severe disease and death in children with postnatally acquired Zika virus infection are rare, the researchers pointed out, but they encouraged physicians to consider a Zika virus disease diagnosis for children with the four common symptoms and who reside in or traveled to an area with active Zika virus transmission. All Zika virus disease cases should be reported to state health departments.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point: Postnatally acquired Zika virus disease in children younger than 18 years is mild and rarely results in severe illness or death.

Major finding: Only two children were hospitalized because of their infections, and no children died.

Data source: Case series of 158 confirmed or probable postnatally acquired Zika virus disease cases among children.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the CDC. Author disclosures were not reported.

New chikungunya diagnostic assay proves quick, effective

A reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification (RT-RPA) assay was able to quickly and effectively identify chikungunya virus (CHIKV), according to a study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Using chikungunya virus RNA samples, the RT-RPA assay detected down to 80 genome copies per reaction within 15 minutes, a time period four to six times faster than other molecular diagnostic techniques, such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In a sensitivity test involving all chikungunya serotypes and various alphaviruses, flaviviruses, and one phlebovirus, the RT-RPA assay identified all virus genotypes, with the only cross-reaction occurring with O’nyong’nyong virus.

In a test involving 58 plasma samples of suspected chikungunya fever from a trial in Thailand, two real-time RT-PCR tests identified 36 out of 58 samples (62%) as positive for chikungunya. The RT-RPA test successfully detected the virus in all 36 positive samples and did not detect the virus in any of the negative samples, giving a sensitivity and specificity of 100%.

“The CHIKV RPA assay presented here is a promising tool for CHIKV diagnostics at the point of need,” the investigators wrote. “Integration into a multimer or multiplex assay for simultaneous and differential detection of CHIKV, Dengue virus, and Zika virus, as well as an internal positive control would improve outbreak investigations, since the three viruses induce the same clinical picture upon infection and increasingly cocirculate in many parts of the world.”

Find the full study in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004953).

A reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification (RT-RPA) assay was able to quickly and effectively identify chikungunya virus (CHIKV), according to a study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Using chikungunya virus RNA samples, the RT-RPA assay detected down to 80 genome copies per reaction within 15 minutes, a time period four to six times faster than other molecular diagnostic techniques, such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In a sensitivity test involving all chikungunya serotypes and various alphaviruses, flaviviruses, and one phlebovirus, the RT-RPA assay identified all virus genotypes, with the only cross-reaction occurring with O’nyong’nyong virus.

In a test involving 58 plasma samples of suspected chikungunya fever from a trial in Thailand, two real-time RT-PCR tests identified 36 out of 58 samples (62%) as positive for chikungunya. The RT-RPA test successfully detected the virus in all 36 positive samples and did not detect the virus in any of the negative samples, giving a sensitivity and specificity of 100%.

“The CHIKV RPA assay presented here is a promising tool for CHIKV diagnostics at the point of need,” the investigators wrote. “Integration into a multimer or multiplex assay for simultaneous and differential detection of CHIKV, Dengue virus, and Zika virus, as well as an internal positive control would improve outbreak investigations, since the three viruses induce the same clinical picture upon infection and increasingly cocirculate in many parts of the world.”

Find the full study in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004953).

A reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification (RT-RPA) assay was able to quickly and effectively identify chikungunya virus (CHIKV), according to a study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Using chikungunya virus RNA samples, the RT-RPA assay detected down to 80 genome copies per reaction within 15 minutes, a time period four to six times faster than other molecular diagnostic techniques, such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In a sensitivity test involving all chikungunya serotypes and various alphaviruses, flaviviruses, and one phlebovirus, the RT-RPA assay identified all virus genotypes, with the only cross-reaction occurring with O’nyong’nyong virus.

In a test involving 58 plasma samples of suspected chikungunya fever from a trial in Thailand, two real-time RT-PCR tests identified 36 out of 58 samples (62%) as positive for chikungunya. The RT-RPA test successfully detected the virus in all 36 positive samples and did not detect the virus in any of the negative samples, giving a sensitivity and specificity of 100%.

“The CHIKV RPA assay presented here is a promising tool for CHIKV diagnostics at the point of need,” the investigators wrote. “Integration into a multimer or multiplex assay for simultaneous and differential detection of CHIKV, Dengue virus, and Zika virus, as well as an internal positive control would improve outbreak investigations, since the three viruses induce the same clinical picture upon infection and increasingly cocirculate in many parts of the world.”

Find the full study in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004953).

FROM PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES

Congress sends Zika funding bill to President

In a move that narrowly avoids a government shutdown, Congress has passed a long-awaited bill that keeps the government afloat and provides $1.1 billion in funding to combat the Zika virus.

The House cleared H.R. 5325 late Sept. 28 by a 342-85 tally, following a 72-26 vote by the Senate earlier in the day. The final package, which keeps the government operating through Dec. 9, also includes $37 million for opioid addiction and $500 million for flooding in Louisiana. The White House has indicated that President Obama will sign the bill into law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists praised Congress for passing the long-delayed comprehensive Zika funding package.

“Congress has finally treated Zika like the emergency it is and shown the American people that it is capable of rising above partisanship for the health of its citizens,” Thomas Gellhaus, MD, ACOG president, said in a statement. “ACOG stands with peer organizations and government agencies in the fight to prevent and respond to the Zika virus and support the care and treatment of all people affected by it. ... The fight against the spread of Zika cannot be won without the resources to support responsive and proactive solutions. This comprehensive funding package is essential to our success and the health of women and babies.”

The bill’s passage caps months of fiery debate within Congress over what to include in the measure. The bill stalled earlier this week largely over whether to direct funds to Flint, Mich., to deal with the crisis over lead-tainted water. Leaders agreed to provide aid to Flint residents in a separate water projects bill. Legislators will address final approval of the Flint measure in December.

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million would go to Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas. The remainder of the funding would be used to prevent, prepare for, and respond to Zika; health conditions related to such virus; and other vector-borne diseases, domestically and internationally.

If signed by the President, the money would also go toward developing necessary countermeasures and vaccines, including the development and purchase of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and necessary medical supplies. Additionally, the funding would aid research on the virology, natural history, and pathogenesis of the Zika virus infection and preclinical and clinical development of vaccines and other medical countermeasures for the Zika virus.

The American Medical Association expressed relief that Congress had finally taken action to provide resources for fighting Zika.

“It has been clear over the past several months that the U.S. has needed additional resources to combat the Zika virus,” AMA president Andrew W. Gurman, MD, said in a statement. “With the threat of the virus continuing to loom, this funding will help protect more people – particularly pregnant women and their children – from the virus’s lasting negative health effects.”

On Twitter @legal_med

In a move that narrowly avoids a government shutdown, Congress has passed a long-awaited bill that keeps the government afloat and provides $1.1 billion in funding to combat the Zika virus.

The House cleared H.R. 5325 late Sept. 28 by a 342-85 tally, following a 72-26 vote by the Senate earlier in the day. The final package, which keeps the government operating through Dec. 9, also includes $37 million for opioid addiction and $500 million for flooding in Louisiana. The White House has indicated that President Obama will sign the bill into law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists praised Congress for passing the long-delayed comprehensive Zika funding package.

“Congress has finally treated Zika like the emergency it is and shown the American people that it is capable of rising above partisanship for the health of its citizens,” Thomas Gellhaus, MD, ACOG president, said in a statement. “ACOG stands with peer organizations and government agencies in the fight to prevent and respond to the Zika virus and support the care and treatment of all people affected by it. ... The fight against the spread of Zika cannot be won without the resources to support responsive and proactive solutions. This comprehensive funding package is essential to our success and the health of women and babies.”

The bill’s passage caps months of fiery debate within Congress over what to include in the measure. The bill stalled earlier this week largely over whether to direct funds to Flint, Mich., to deal with the crisis over lead-tainted water. Leaders agreed to provide aid to Flint residents in a separate water projects bill. Legislators will address final approval of the Flint measure in December.

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million would go to Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas. The remainder of the funding would be used to prevent, prepare for, and respond to Zika; health conditions related to such virus; and other vector-borne diseases, domestically and internationally.

If signed by the President, the money would also go toward developing necessary countermeasures and vaccines, including the development and purchase of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and necessary medical supplies. Additionally, the funding would aid research on the virology, natural history, and pathogenesis of the Zika virus infection and preclinical and clinical development of vaccines and other medical countermeasures for the Zika virus.

The American Medical Association expressed relief that Congress had finally taken action to provide resources for fighting Zika.

“It has been clear over the past several months that the U.S. has needed additional resources to combat the Zika virus,” AMA president Andrew W. Gurman, MD, said in a statement. “With the threat of the virus continuing to loom, this funding will help protect more people – particularly pregnant women and their children – from the virus’s lasting negative health effects.”

On Twitter @legal_med

In a move that narrowly avoids a government shutdown, Congress has passed a long-awaited bill that keeps the government afloat and provides $1.1 billion in funding to combat the Zika virus.

The House cleared H.R. 5325 late Sept. 28 by a 342-85 tally, following a 72-26 vote by the Senate earlier in the day. The final package, which keeps the government operating through Dec. 9, also includes $37 million for opioid addiction and $500 million for flooding in Louisiana. The White House has indicated that President Obama will sign the bill into law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists praised Congress for passing the long-delayed comprehensive Zika funding package.

“Congress has finally treated Zika like the emergency it is and shown the American people that it is capable of rising above partisanship for the health of its citizens,” Thomas Gellhaus, MD, ACOG president, said in a statement. “ACOG stands with peer organizations and government agencies in the fight to prevent and respond to the Zika virus and support the care and treatment of all people affected by it. ... The fight against the spread of Zika cannot be won without the resources to support responsive and proactive solutions. This comprehensive funding package is essential to our success and the health of women and babies.”

The bill’s passage caps months of fiery debate within Congress over what to include in the measure. The bill stalled earlier this week largely over whether to direct funds to Flint, Mich., to deal with the crisis over lead-tainted water. Leaders agreed to provide aid to Flint residents in a separate water projects bill. Legislators will address final approval of the Flint measure in December.

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million would go to Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas. The remainder of the funding would be used to prevent, prepare for, and respond to Zika; health conditions related to such virus; and other vector-borne diseases, domestically and internationally.

If signed by the President, the money would also go toward developing necessary countermeasures and vaccines, including the development and purchase of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and necessary medical supplies. Additionally, the funding would aid research on the virology, natural history, and pathogenesis of the Zika virus infection and preclinical and clinical development of vaccines and other medical countermeasures for the Zika virus.

The American Medical Association expressed relief that Congress had finally taken action to provide resources for fighting Zika.

“It has been clear over the past several months that the U.S. has needed additional resources to combat the Zika virus,” AMA president Andrew W. Gurman, MD, said in a statement. “With the threat of the virus continuing to loom, this funding will help protect more people – particularly pregnant women and their children – from the virus’s lasting negative health effects.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Nonsexual secondary Zika virus case confirmed in Utah

The first case of nonsexual secondary Zika virus transmission has occurred in the United States, according to a research letter published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We report a rapidly progressive, fatal [Zika virus] infection acquired outside the United States and secondary local transmission in the absence of known risk factors,” wrote the authors of the report, led by Sankar Swaminathan, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The individual infected via secondary transmission, dubbed Patient Two in the report, is suspected to have contracted the disease from Patient One, a 73-year-old man who visited the southwestern coast of Mexico – a known hotbed of Zika virus – for a 3-week trip before returning to the United States. Eight days after returning, Patient One was admitted to a Salt Lake City hospital with symptoms consistent with a flavivirus infection and told doctors that he had been bitten by mosquitoes during his trip (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610613).

After undergoing tourniquet and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of dengue shock syndrome was made, but Patient One’s condition continued to deteriorate rapidly. Patient One died 4 days after initial hospitalization; real-time PCR assay confirmed Zika virus infection shortly thereafter.

Patient Two came into contact with Patient One during the latter’s hospitalization, reporting that he “assisted a nurse in repositioning Patient One in bed without using gloves,” according to the report. Patient Two began experiencing conjunctivitis, fever, myalgia, and a maculopapular rash on his face 5 days after Patient One died. The rash resolved itself after 7 days, and while PCR analysis of Patient Two’s serum was negative for Zika, his urinalysis was positive.

Because Patient Two had not traveled to a Zika-endemic area within 9 months of experiencing Zika-like symptoms and had not engaged in sexual intercourse with anyone who traveled to a Zika-endemic area, the authors conclude that he contracted the disease from contact with Patient One. The authors posit that, given the high levels of viremia in Patient One, the Zika virus could have been transmitted to Patient Two via sweat or tears, which Patient Two came into contact with while not wearing gloves. Local transmission via Aedis aegypti mosquito bite was highly unlikely to be the cause of transmission because of the lack of such mosquitoes in the Salt Lake City area.

“These two cases illustrate several important points,” the authors concluded. “The spectrum of those at risk for fulminant [Zika virus] infection may be broader than previously recognized, and those who are not severely immunocompromised or chronically ill may nevertheless be at risk for fatal infection.”

The first case of nonsexual secondary Zika virus transmission has occurred in the United States, according to a research letter published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We report a rapidly progressive, fatal [Zika virus] infection acquired outside the United States and secondary local transmission in the absence of known risk factors,” wrote the authors of the report, led by Sankar Swaminathan, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The individual infected via secondary transmission, dubbed Patient Two in the report, is suspected to have contracted the disease from Patient One, a 73-year-old man who visited the southwestern coast of Mexico – a known hotbed of Zika virus – for a 3-week trip before returning to the United States. Eight days after returning, Patient One was admitted to a Salt Lake City hospital with symptoms consistent with a flavivirus infection and told doctors that he had been bitten by mosquitoes during his trip (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610613).

After undergoing tourniquet and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of dengue shock syndrome was made, but Patient One’s condition continued to deteriorate rapidly. Patient One died 4 days after initial hospitalization; real-time PCR assay confirmed Zika virus infection shortly thereafter.

Patient Two came into contact with Patient One during the latter’s hospitalization, reporting that he “assisted a nurse in repositioning Patient One in bed without using gloves,” according to the report. Patient Two began experiencing conjunctivitis, fever, myalgia, and a maculopapular rash on his face 5 days after Patient One died. The rash resolved itself after 7 days, and while PCR analysis of Patient Two’s serum was negative for Zika, his urinalysis was positive.

Because Patient Two had not traveled to a Zika-endemic area within 9 months of experiencing Zika-like symptoms and had not engaged in sexual intercourse with anyone who traveled to a Zika-endemic area, the authors conclude that he contracted the disease from contact with Patient One. The authors posit that, given the high levels of viremia in Patient One, the Zika virus could have been transmitted to Patient Two via sweat or tears, which Patient Two came into contact with while not wearing gloves. Local transmission via Aedis aegypti mosquito bite was highly unlikely to be the cause of transmission because of the lack of such mosquitoes in the Salt Lake City area.

“These two cases illustrate several important points,” the authors concluded. “The spectrum of those at risk for fulminant [Zika virus] infection may be broader than previously recognized, and those who are not severely immunocompromised or chronically ill may nevertheless be at risk for fatal infection.”

The first case of nonsexual secondary Zika virus transmission has occurred in the United States, according to a research letter published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We report a rapidly progressive, fatal [Zika virus] infection acquired outside the United States and secondary local transmission in the absence of known risk factors,” wrote the authors of the report, led by Sankar Swaminathan, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The individual infected via secondary transmission, dubbed Patient Two in the report, is suspected to have contracted the disease from Patient One, a 73-year-old man who visited the southwestern coast of Mexico – a known hotbed of Zika virus – for a 3-week trip before returning to the United States. Eight days after returning, Patient One was admitted to a Salt Lake City hospital with symptoms consistent with a flavivirus infection and told doctors that he had been bitten by mosquitoes during his trip (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610613).

After undergoing tourniquet and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of dengue shock syndrome was made, but Patient One’s condition continued to deteriorate rapidly. Patient One died 4 days after initial hospitalization; real-time PCR assay confirmed Zika virus infection shortly thereafter.

Patient Two came into contact with Patient One during the latter’s hospitalization, reporting that he “assisted a nurse in repositioning Patient One in bed without using gloves,” according to the report. Patient Two began experiencing conjunctivitis, fever, myalgia, and a maculopapular rash on his face 5 days after Patient One died. The rash resolved itself after 7 days, and while PCR analysis of Patient Two’s serum was negative for Zika, his urinalysis was positive.

Because Patient Two had not traveled to a Zika-endemic area within 9 months of experiencing Zika-like symptoms and had not engaged in sexual intercourse with anyone who traveled to a Zika-endemic area, the authors conclude that he contracted the disease from contact with Patient One. The authors posit that, given the high levels of viremia in Patient One, the Zika virus could have been transmitted to Patient Two via sweat or tears, which Patient Two came into contact with while not wearing gloves. Local transmission via Aedis aegypti mosquito bite was highly unlikely to be the cause of transmission because of the lack of such mosquitoes in the Salt Lake City area.

“These two cases illustrate several important points,” the authors concluded. “The spectrum of those at risk for fulminant [Zika virus] infection may be broader than previously recognized, and those who are not severely immunocompromised or chronically ill may nevertheless be at risk for fatal infection.”

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

VIDEO: Consider chikungunya for unexplained seronegative arthritis

LAS VEGAS – When rheumatologists consider a differential diagnosis that includes seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, they should also consider chikungunya, according to Len Calabrese, DO.

The patient who presents with weeks to months of unexplained arthralgia and perhaps arthritis and a negative autoimmune panel deserves consideration of chikungunya or another arbovirus, said Dr. Calabrese, speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases held by the Global Academy for Medical Education.

Among the mosquito-borne arboviruses now in play in the Western Hemisphere, chikungunya is particularly likely to cause long-lasting and sometimes debilitating joint pain weeks and even months after initial infection.

An alphavirus, chikungunya virus makes most affected individuals quite ill, and serum IgG and IgM titers persist long after infection. Testing is straightforward, as long as the virus is a candidate diagnosis, Dr. Calabrese said.

In addition to obtaining an accurate travel history, said Dr. Calabrese, physicians should consider the possibility of autochthonous transmission, which occurs when an infected individual who returns from an endemic area is bitten by mosquitoes once home. Flares of autochthonous transmission can result in pockets of locally heavy transmission far from the zones where chikungunya usually resides.

Dr. Calabrese is chair of clinical immunology and chair of osteopathic research and education at the Cleveland Clinic, and he reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – When rheumatologists consider a differential diagnosis that includes seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, they should also consider chikungunya, according to Len Calabrese, DO.

The patient who presents with weeks to months of unexplained arthralgia and perhaps arthritis and a negative autoimmune panel deserves consideration of chikungunya or another arbovirus, said Dr. Calabrese, speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases held by the Global Academy for Medical Education.

Among the mosquito-borne arboviruses now in play in the Western Hemisphere, chikungunya is particularly likely to cause long-lasting and sometimes debilitating joint pain weeks and even months after initial infection.

An alphavirus, chikungunya virus makes most affected individuals quite ill, and serum IgG and IgM titers persist long after infection. Testing is straightforward, as long as the virus is a candidate diagnosis, Dr. Calabrese said.

In addition to obtaining an accurate travel history, said Dr. Calabrese, physicians should consider the possibility of autochthonous transmission, which occurs when an infected individual who returns from an endemic area is bitten by mosquitoes once home. Flares of autochthonous transmission can result in pockets of locally heavy transmission far from the zones where chikungunya usually resides.

Dr. Calabrese is chair of clinical immunology and chair of osteopathic research and education at the Cleveland Clinic, and he reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – When rheumatologists consider a differential diagnosis that includes seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, they should also consider chikungunya, according to Len Calabrese, DO.

The patient who presents with weeks to months of unexplained arthralgia and perhaps arthritis and a negative autoimmune panel deserves consideration of chikungunya or another arbovirus, said Dr. Calabrese, speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases held by the Global Academy for Medical Education.

Among the mosquito-borne arboviruses now in play in the Western Hemisphere, chikungunya is particularly likely to cause long-lasting and sometimes debilitating joint pain weeks and even months after initial infection.

An alphavirus, chikungunya virus makes most affected individuals quite ill, and serum IgG and IgM titers persist long after infection. Testing is straightforward, as long as the virus is a candidate diagnosis, Dr. Calabrese said.

In addition to obtaining an accurate travel history, said Dr. Calabrese, physicians should consider the possibility of autochthonous transmission, which occurs when an infected individual who returns from an endemic area is bitten by mosquitoes once home. Flares of autochthonous transmission can result in pockets of locally heavy transmission far from the zones where chikungunya usually resides.

Dr. Calabrese is chair of clinical immunology and chair of osteopathic research and education at the Cleveland Clinic, and he reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ANNUAL PERSPECTIVES IN RHEUMATIC DISEASES

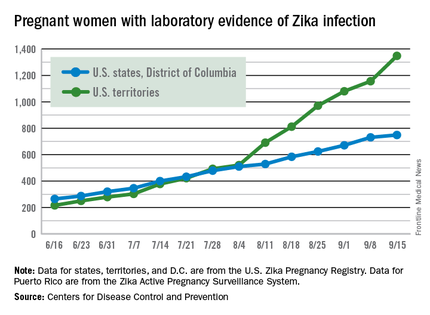

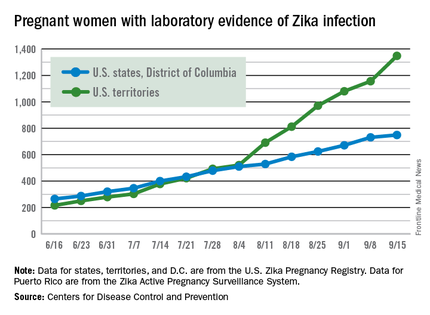

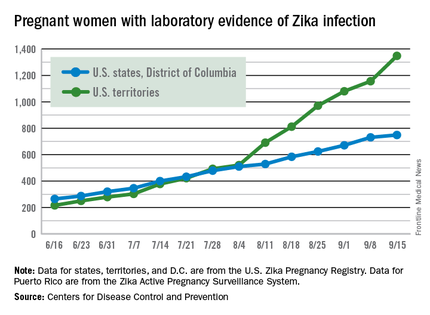

Zika cases in pregnant women hit new weekly high

The weekly number of pregnant women in the United States with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection topped 200 for the first time during the week ending Sept. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With the 50 states and the District of Columbia reporting 18 new cases for the week and the U.S. territories reporting 192, there were 210 more pregnant women with Zika for the week ending Sept. 15, the CDC reported Sept. 22. The previous weekly high had been 199 for the week ending Aug. 25.

The CDC also reported two new cases of liveborn infants – both in the 50 states and D.C. – with Zika-related birth defects. No infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported in the territories for the week, and there were no new reports of pregnancy losses related to Zika. The number of pregnancy losses holds at six for the year so far, but the number of U.S. liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects is now 21, with 20 cases in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

There were 182 new cases of Zika infection reported among all Americans in the states/D.C. for the week ending Sept. 21, along with 2,083 new cases in the territories – almost all in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC noted Sept. 22. The U.S. total for 2015-2016 is 23,135 cases: 3,358 reported in the states/D.C. and 19,777 in the territories. Puerto Rico represents 98% of the territorial total, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

The weekly number of pregnant women in the United States with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection topped 200 for the first time during the week ending Sept. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With the 50 states and the District of Columbia reporting 18 new cases for the week and the U.S. territories reporting 192, there were 210 more pregnant women with Zika for the week ending Sept. 15, the CDC reported Sept. 22. The previous weekly high had been 199 for the week ending Aug. 25.

The CDC also reported two new cases of liveborn infants – both in the 50 states and D.C. – with Zika-related birth defects. No infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported in the territories for the week, and there were no new reports of pregnancy losses related to Zika. The number of pregnancy losses holds at six for the year so far, but the number of U.S. liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects is now 21, with 20 cases in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

There were 182 new cases of Zika infection reported among all Americans in the states/D.C. for the week ending Sept. 21, along with 2,083 new cases in the territories – almost all in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC noted Sept. 22. The U.S. total for 2015-2016 is 23,135 cases: 3,358 reported in the states/D.C. and 19,777 in the territories. Puerto Rico represents 98% of the territorial total, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

The weekly number of pregnant women in the United States with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection topped 200 for the first time during the week ending Sept. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With the 50 states and the District of Columbia reporting 18 new cases for the week and the U.S. territories reporting 192, there were 210 more pregnant women with Zika for the week ending Sept. 15, the CDC reported Sept. 22. The previous weekly high had been 199 for the week ending Aug. 25.

The CDC also reported two new cases of liveborn infants – both in the 50 states and D.C. – with Zika-related birth defects. No infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported in the territories for the week, and there were no new reports of pregnancy losses related to Zika. The number of pregnancy losses holds at six for the year so far, but the number of U.S. liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects is now 21, with 20 cases in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

There were 182 new cases of Zika infection reported among all Americans in the states/D.C. for the week ending Sept. 21, along with 2,083 new cases in the territories – almost all in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC noted Sept. 22. The U.S. total for 2015-2016 is 23,135 cases: 3,358 reported in the states/D.C. and 19,777 in the territories. Puerto Rico represents 98% of the territorial total, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

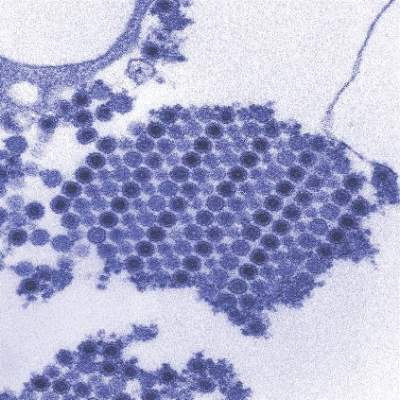

Two novel DNA Zika virus vaccines set for human trials

The search is on for clinical trial participants to help verify whether two genetically based vaccines that lowered Zika virus viremia in infected primates will be effective in humans.

Although much is still unknown about the pathogenesis, immunity, and transmission of the flavivirus, its devastating effects mean developing a vaccine is imperative, wrote Kimberly A. Dowd, PhD, a virologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and her colleagues in a paper published online in Science.

According to Dr. Dowd and her coauthors, the quickest path to a Zika vaccine is to start with what is already known about flaviviruses and to avoid unnecessary bureaucracy.

“Advantages of DNA vaccines include the ability to rapidly test multiple candidate antigen designs, rapidly produce GMP material, and established safety profile in humans, and a relatively straightforward regulatory pathway into clinical evaluation,” Dr. Dowd and her colleagues wrote. The study details the results of two Zika vaccine candidates tested in primates. The clinical trial will now test these vaccines’ efficacy in humans (Science. 2016 Sept 22. doi: 10.1126/science.aai3197).

Starting with insights gained from DNA-based testing for a West Nile virus vaccine that showed vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies are associated with protection from flavivirus-mediated disease, and data showing that a single vaccine antigen will protect against all strains of Zika virus, Dr. Dowd and her coinvestigators developed two DNA-based vaccines that successfully bound to Zika subviral particles in infected mice. Then they tested the vaccines in rhesus macaques.

Six animals were injected with either 1 mg of VRC5283 at 0 and 4 weeks. Another six were injected with 4 mg of either VRC5283 or VRC5288 at 0 or 4 weeks. Another six were injected with a single 1-mg dose of VRC5288 at week 0. After the initial DNA dose, all animals were found to have detectable binding and neutralizing antibody activity, peaking at week 3. Compared with controls given the CMV-immediate early-promoter–containing vector VRC8400, all study animals had a significantly higher neutralizing antibody response (P = .022). The group given the single dose of VRC5288 had significantly lower neutralizing antibody titers, compared with macaques given two doses of either vaccine (P = .022).

Across the groups given two doses of either vaccine, there were no significant differences between titer levels, suggesting that both vaccine candidates elicit substantial Zika virus–specific neutralizing antibodies in primates. More to the point was that 8 weeks after immunization, when all animals in the study were challenged subcutaneously with the virus, viremia levels in the 18 total macaques given two doses of either amount and of either vaccine were undetectable in all but 1. Compared with controls, that had peak viral loads on day 3 or 4, the six animals given one dose of 1 mg VRC5288 were viremic on day 3, but at a significantly reduced rate (P = .041).

Taking into account one animal in the VRC5288 two-dose 4-mg group that had viral load blips above background on days 3 and 7, as well as the lowest titer levels of all the test animals, the investigators determined that 70% protection from Zika virus viremia would be possible if certain titer levels could be achieved.

Whether waning or incomplete immunity could lead to enhanced flavivirus disease is a concern when developing correct vaccination dosage, the investigators said. However, despite some breakthrough infection in the group given the single 1 mg dose of VRC5288, the animals’ illness remained subclinical, there were no signs of replication, and their viremia levels were lower than in unvaccinated controls.

Now, all eyes are on how the vaccines compare with one another while researchers try to establish an adequate serologic correlate of sterilizing immunity in humans. According to Dr. Dowd and her colleagues, the phase I trial is being designed in parallel with other trials looking into a purified, protein-based whole-inactivated Zika virus vaccine, as well as other antigens, delivery methods, and combination vaccines.

The multipronged approach improves the likelihood that enough immunogenicity data can be gathered and translated into a successful intervention for the women of child-bearing age most affected by the Zika virus, and the general population at large, Dr. Dowd and her colleagues concluded.

The research was supported by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; start-up funding from the department of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University; and federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, NIH. One of the coauthors also reported funding from Leidos Biomedical Research.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The search is on for clinical trial participants to help verify whether two genetically based vaccines that lowered Zika virus viremia in infected primates will be effective in humans.

Although much is still unknown about the pathogenesis, immunity, and transmission of the flavivirus, its devastating effects mean developing a vaccine is imperative, wrote Kimberly A. Dowd, PhD, a virologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and her colleagues in a paper published online in Science.

According to Dr. Dowd and her coauthors, the quickest path to a Zika vaccine is to start with what is already known about flaviviruses and to avoid unnecessary bureaucracy.

“Advantages of DNA vaccines include the ability to rapidly test multiple candidate antigen designs, rapidly produce GMP material, and established safety profile in humans, and a relatively straightforward regulatory pathway into clinical evaluation,” Dr. Dowd and her colleagues wrote. The study details the results of two Zika vaccine candidates tested in primates. The clinical trial will now test these vaccines’ efficacy in humans (Science. 2016 Sept 22. doi: 10.1126/science.aai3197).

Starting with insights gained from DNA-based testing for a West Nile virus vaccine that showed vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies are associated with protection from flavivirus-mediated disease, and data showing that a single vaccine antigen will protect against all strains of Zika virus, Dr. Dowd and her coinvestigators developed two DNA-based vaccines that successfully bound to Zika subviral particles in infected mice. Then they tested the vaccines in rhesus macaques.

Six animals were injected with either 1 mg of VRC5283 at 0 and 4 weeks. Another six were injected with 4 mg of either VRC5283 or VRC5288 at 0 or 4 weeks. Another six were injected with a single 1-mg dose of VRC5288 at week 0. After the initial DNA dose, all animals were found to have detectable binding and neutralizing antibody activity, peaking at week 3. Compared with controls given the CMV-immediate early-promoter–containing vector VRC8400, all study animals had a significantly higher neutralizing antibody response (P = .022). The group given the single dose of VRC5288 had significantly lower neutralizing antibody titers, compared with macaques given two doses of either vaccine (P = .022).

Across the groups given two doses of either vaccine, there were no significant differences between titer levels, suggesting that both vaccine candidates elicit substantial Zika virus–specific neutralizing antibodies in primates. More to the point was that 8 weeks after immunization, when all animals in the study were challenged subcutaneously with the virus, viremia levels in the 18 total macaques given two doses of either amount and of either vaccine were undetectable in all but 1. Compared with controls, that had peak viral loads on day 3 or 4, the six animals given one dose of 1 mg VRC5288 were viremic on day 3, but at a significantly reduced rate (P = .041).

Taking into account one animal in the VRC5288 two-dose 4-mg group that had viral load blips above background on days 3 and 7, as well as the lowest titer levels of all the test animals, the investigators determined that 70% protection from Zika virus viremia would be possible if certain titer levels could be achieved.

Whether waning or incomplete immunity could lead to enhanced flavivirus disease is a concern when developing correct vaccination dosage, the investigators said. However, despite some breakthrough infection in the group given the single 1 mg dose of VRC5288, the animals’ illness remained subclinical, there were no signs of replication, and their viremia levels were lower than in unvaccinated controls.

Now, all eyes are on how the vaccines compare with one another while researchers try to establish an adequate serologic correlate of sterilizing immunity in humans. According to Dr. Dowd and her colleagues, the phase I trial is being designed in parallel with other trials looking into a purified, protein-based whole-inactivated Zika virus vaccine, as well as other antigens, delivery methods, and combination vaccines.

The multipronged approach improves the likelihood that enough immunogenicity data can be gathered and translated into a successful intervention for the women of child-bearing age most affected by the Zika virus, and the general population at large, Dr. Dowd and her colleagues concluded.

The research was supported by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; start-up funding from the department of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University; and federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, NIH. One of the coauthors also reported funding from Leidos Biomedical Research.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The search is on for clinical trial participants to help verify whether two genetically based vaccines that lowered Zika virus viremia in infected primates will be effective in humans.

Although much is still unknown about the pathogenesis, immunity, and transmission of the flavivirus, its devastating effects mean developing a vaccine is imperative, wrote Kimberly A. Dowd, PhD, a virologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and her colleagues in a paper published online in Science.

According to Dr. Dowd and her coauthors, the quickest path to a Zika vaccine is to start with what is already known about flaviviruses and to avoid unnecessary bureaucracy.

“Advantages of DNA vaccines include the ability to rapidly test multiple candidate antigen designs, rapidly produce GMP material, and established safety profile in humans, and a relatively straightforward regulatory pathway into clinical evaluation,” Dr. Dowd and her colleagues wrote. The study details the results of two Zika vaccine candidates tested in primates. The clinical trial will now test these vaccines’ efficacy in humans (Science. 2016 Sept 22. doi: 10.1126/science.aai3197).

Starting with insights gained from DNA-based testing for a West Nile virus vaccine that showed vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies are associated with protection from flavivirus-mediated disease, and data showing that a single vaccine antigen will protect against all strains of Zika virus, Dr. Dowd and her coinvestigators developed two DNA-based vaccines that successfully bound to Zika subviral particles in infected mice. Then they tested the vaccines in rhesus macaques.

Six animals were injected with either 1 mg of VRC5283 at 0 and 4 weeks. Another six were injected with 4 mg of either VRC5283 or VRC5288 at 0 or 4 weeks. Another six were injected with a single 1-mg dose of VRC5288 at week 0. After the initial DNA dose, all animals were found to have detectable binding and neutralizing antibody activity, peaking at week 3. Compared with controls given the CMV-immediate early-promoter–containing vector VRC8400, all study animals had a significantly higher neutralizing antibody response (P = .022). The group given the single dose of VRC5288 had significantly lower neutralizing antibody titers, compared with macaques given two doses of either vaccine (P = .022).

Across the groups given two doses of either vaccine, there were no significant differences between titer levels, suggesting that both vaccine candidates elicit substantial Zika virus–specific neutralizing antibodies in primates. More to the point was that 8 weeks after immunization, when all animals in the study were challenged subcutaneously with the virus, viremia levels in the 18 total macaques given two doses of either amount and of either vaccine were undetectable in all but 1. Compared with controls, that had peak viral loads on day 3 or 4, the six animals given one dose of 1 mg VRC5288 were viremic on day 3, but at a significantly reduced rate (P = .041).

Taking into account one animal in the VRC5288 two-dose 4-mg group that had viral load blips above background on days 3 and 7, as well as the lowest titer levels of all the test animals, the investigators determined that 70% protection from Zika virus viremia would be possible if certain titer levels could be achieved.

Whether waning or incomplete immunity could lead to enhanced flavivirus disease is a concern when developing correct vaccination dosage, the investigators said. However, despite some breakthrough infection in the group given the single 1 mg dose of VRC5288, the animals’ illness remained subclinical, there were no signs of replication, and their viremia levels were lower than in unvaccinated controls.

Now, all eyes are on how the vaccines compare with one another while researchers try to establish an adequate serologic correlate of sterilizing immunity in humans. According to Dr. Dowd and her colleagues, the phase I trial is being designed in parallel with other trials looking into a purified, protein-based whole-inactivated Zika virus vaccine, as well as other antigens, delivery methods, and combination vaccines.

The multipronged approach improves the likelihood that enough immunogenicity data can be gathered and translated into a successful intervention for the women of child-bearing age most affected by the Zika virus, and the general population at large, Dr. Dowd and her colleagues concluded.

The research was supported by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; start-up funding from the department of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University; and federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, NIH. One of the coauthors also reported funding from Leidos Biomedical Research.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM SCIENCE

Key clinical point: A DNA vaccination could be a successful approach to protect against Zika virus infection.

Major finding: Two DNA vaccines with efficacy against the Zika virus in primates are set to begin testing in humans.

Data source: Animal trials of two DNA-based Zika virus vaccines in infected mice and rhesus macaques.

Disclosures: The research was supported by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; start-up funding from the department of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University; and federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, NIH. One of the coauthors also reported funding from Leidos Biomedical Research.

Case-control study points to Zika virus as cause of microcephaly

A new study from Brazil demonstrates that microcephaly is strongly associated with congenital Zika virus infections, offering case-control evidence of a causal relationship.

“This is the first case-control study to examine the association between Zika virus and microcephaly using molecular and serological analysis to identify Zika virus in cases and controls at the time of birth,” Thalia Velho Barreto de Araújo, PhD, of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, said in a statement. “Our findings suggest that Zika virus should be officially added to the list of congenital infections alongside toxoplasmosis, syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes. However, many questions still remain to be answered including the role of previous dengue infection.”

In April, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly, following a systematic review of the available Zika virus research.

In the current study, the investigators looked for cases of infants born with microcephaly at eight public hospitals in Pernambuco, a state in northeastern Brazil. Thirty-two such cases were included for analysis, along with 62 controls. All infants in the study were born between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30318-8).

Zika-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were conducted on serum from both microcephaly and control infants, and cerebrospinal fluid samples only from infants with microcephaly. Mothers underwent serum testing for Zika virus and dengue virus via plaque reduction neutralization assay testing. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were then calculated to determine the association between congenital Zika virus and microcephaly.

Of the 30 women who gave birth to infants with microcephaly, 24 (80%) had Zika virus infections, compared with 39 of the 61 women (64%) in the control group (P = .12). Additionally, while 13 of the 32 infants born with microcephaly had Zika virus infections confirmed by laboratory testing, none of the infants in the control group had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection.

A total of 7 out 27 infants with microcephaly who underwent CT scans showed signs of brain abnormalities, suggesting that “congenital Zika virus syndrome can be present in neonates with microcephaly and no radiological brain abnormalities,” according to the investigators.

While the study is still ongoing, the investigators called for more research to assess other potential risk factors and to confirm the strength of association in a larger sample size, as well as to gauge the significance and role of previous dengue infections in the mothers.

The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study from Brazil demonstrates that microcephaly is strongly associated with congenital Zika virus infections, offering case-control evidence of a causal relationship.

“This is the first case-control study to examine the association between Zika virus and microcephaly using molecular and serological analysis to identify Zika virus in cases and controls at the time of birth,” Thalia Velho Barreto de Araújo, PhD, of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, said in a statement. “Our findings suggest that Zika virus should be officially added to the list of congenital infections alongside toxoplasmosis, syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes. However, many questions still remain to be answered including the role of previous dengue infection.”

In April, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly, following a systematic review of the available Zika virus research.

In the current study, the investigators looked for cases of infants born with microcephaly at eight public hospitals in Pernambuco, a state in northeastern Brazil. Thirty-two such cases were included for analysis, along with 62 controls. All infants in the study were born between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30318-8).

Zika-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were conducted on serum from both microcephaly and control infants, and cerebrospinal fluid samples only from infants with microcephaly. Mothers underwent serum testing for Zika virus and dengue virus via plaque reduction neutralization assay testing. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were then calculated to determine the association between congenital Zika virus and microcephaly.

Of the 30 women who gave birth to infants with microcephaly, 24 (80%) had Zika virus infections, compared with 39 of the 61 women (64%) in the control group (P = .12). Additionally, while 13 of the 32 infants born with microcephaly had Zika virus infections confirmed by laboratory testing, none of the infants in the control group had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection.

A total of 7 out 27 infants with microcephaly who underwent CT scans showed signs of brain abnormalities, suggesting that “congenital Zika virus syndrome can be present in neonates with microcephaly and no radiological brain abnormalities,” according to the investigators.

While the study is still ongoing, the investigators called for more research to assess other potential risk factors and to confirm the strength of association in a larger sample size, as well as to gauge the significance and role of previous dengue infections in the mothers.

The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study from Brazil demonstrates that microcephaly is strongly associated with congenital Zika virus infections, offering case-control evidence of a causal relationship.

“This is the first case-control study to examine the association between Zika virus and microcephaly using molecular and serological analysis to identify Zika virus in cases and controls at the time of birth,” Thalia Velho Barreto de Araújo, PhD, of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, said in a statement. “Our findings suggest that Zika virus should be officially added to the list of congenital infections alongside toxoplasmosis, syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes. However, many questions still remain to be answered including the role of previous dengue infection.”

In April, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly, following a systematic review of the available Zika virus research.

In the current study, the investigators looked for cases of infants born with microcephaly at eight public hospitals in Pernambuco, a state in northeastern Brazil. Thirty-two such cases were included for analysis, along with 62 controls. All infants in the study were born between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30318-8).

Zika-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were conducted on serum from both microcephaly and control infants, and cerebrospinal fluid samples only from infants with microcephaly. Mothers underwent serum testing for Zika virus and dengue virus via plaque reduction neutralization assay testing. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were then calculated to determine the association between congenital Zika virus and microcephaly.

Of the 30 women who gave birth to infants with microcephaly, 24 (80%) had Zika virus infections, compared with 39 of the 61 women (64%) in the control group (P = .12). Additionally, while 13 of the 32 infants born with microcephaly had Zika virus infections confirmed by laboratory testing, none of the infants in the control group had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection.

A total of 7 out 27 infants with microcephaly who underwent CT scans showed signs of brain abnormalities, suggesting that “congenital Zika virus syndrome can be present in neonates with microcephaly and no radiological brain abnormalities,” according to the investigators.

While the study is still ongoing, the investigators called for more research to assess other potential risk factors and to confirm the strength of association in a larger sample size, as well as to gauge the significance and role of previous dengue infections in the mothers.

The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: The current microcephaly epidemic is a result of congenital Zika virus infection.

Major finding: In total, 41% of infants born with microcephaly had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection, compared with none of the infants in the control group.

Data source: Prospective, ongoing case-control study of 32 microcephaly cases and 62 controls at eight hospitals in Brazil between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

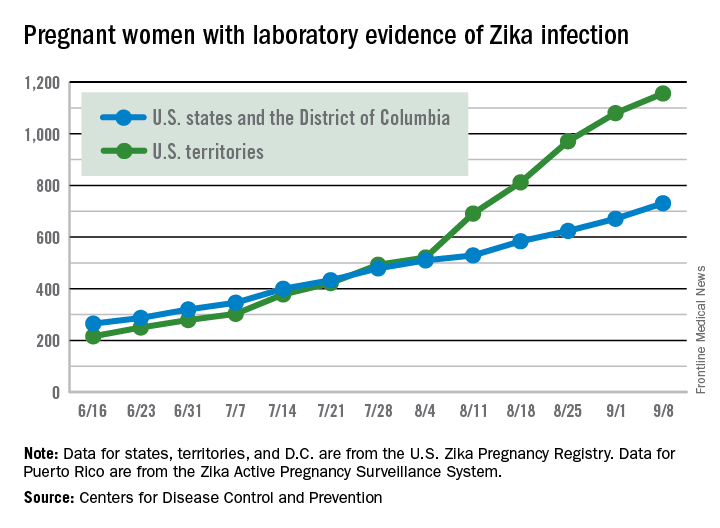

Number of Zika-infected pregnancies jumps in states/D.C.

There were 60 more pregnant women in the 50 states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 8, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That is the largest weekly increase yet among that population, and it brings the total number of Zika-infected pregnant women to 731 in the 50 states and D.C. so far in 2016. The U.S. territories reported 76 new cases for the week ending Sept. 8, for a territorial total of 1,156 and a combined U.S. total of 1,887 pregnant women with Zika virus, the CDC reported Sept. 15.

For the second week in a row, a liveborn infant with Zika-related birth defects was born in the 50 states/D.C. The total is now 19 for the year: 18 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories. There were no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects, so the number holds at six for the year: five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

There were 60 more pregnant women in the 50 states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 8, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That is the largest weekly increase yet among that population, and it brings the total number of Zika-infected pregnant women to 731 in the 50 states and D.C. so far in 2016. The U.S. territories reported 76 new cases for the week ending Sept. 8, for a territorial total of 1,156 and a combined U.S. total of 1,887 pregnant women with Zika virus, the CDC reported Sept. 15.

For the second week in a row, a liveborn infant with Zika-related birth defects was born in the 50 states/D.C. The total is now 19 for the year: 18 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories. There were no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects, so the number holds at six for the year: five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.