User login

Territories now have U.S. majority of pregnant women with Zika

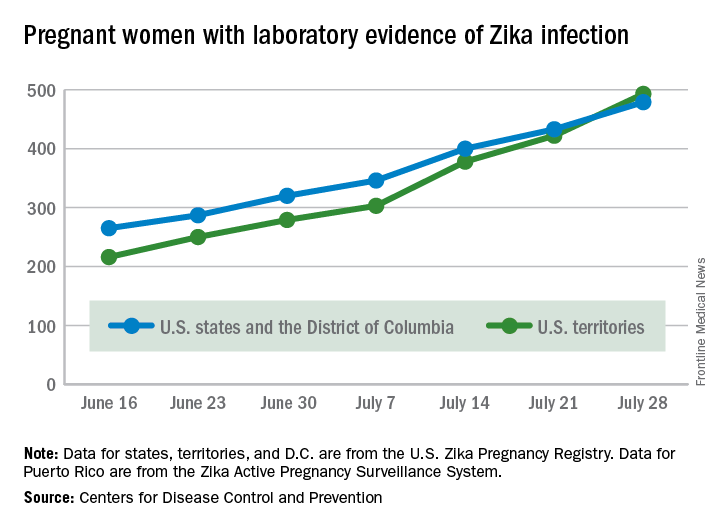

The total number of pregnant women with evidence of Zika virus infection reported in the U.S. territories surpassed that of the 50 states and the District of Columbia during the week ending July 28, 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 71 new cases of Zika in pregnant women reported in U.S. territories that week, bringing the total for the year to 493. The states and D.C. reported 46 new cases, for a total of 479 for the year, which puts the United States as a whole at 972 cases of confirmed Zika virus infection in pregnant women for 2016, the CDC reported Aug. 4.

Among the territories, the overwhelming majority of Zika cases are in Puerto Rico, which has reported 5,482 cases so far, compared with 44 in American Samoa and 22 in the U.S. Virgin Islands. In all, there have been 1,825 cases reported in the states and D.C., the CDC reported.

The territories, so far, have mostly avoided Zika-related pregnancy losses and birth defects, with only one case of pregnancy loss and no infants born with birth defects in 2016. Two more cases of infants born with birth defects were reported, however, in the states and D.C. for the week ending July 28, bringing the state/D.C. total to 15 for the year, but no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects were added to the six reported so far, the CDC announced.

“These outcomes occurred in pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection,” the CDC noted, and it is not known “whether they were caused by Zika virus infection or other factors.”

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The total number of pregnant women with evidence of Zika virus infection reported in the U.S. territories surpassed that of the 50 states and the District of Columbia during the week ending July 28, 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 71 new cases of Zika in pregnant women reported in U.S. territories that week, bringing the total for the year to 493. The states and D.C. reported 46 new cases, for a total of 479 for the year, which puts the United States as a whole at 972 cases of confirmed Zika virus infection in pregnant women for 2016, the CDC reported Aug. 4.

Among the territories, the overwhelming majority of Zika cases are in Puerto Rico, which has reported 5,482 cases so far, compared with 44 in American Samoa and 22 in the U.S. Virgin Islands. In all, there have been 1,825 cases reported in the states and D.C., the CDC reported.

The territories, so far, have mostly avoided Zika-related pregnancy losses and birth defects, with only one case of pregnancy loss and no infants born with birth defects in 2016. Two more cases of infants born with birth defects were reported, however, in the states and D.C. for the week ending July 28, bringing the state/D.C. total to 15 for the year, but no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects were added to the six reported so far, the CDC announced.

“These outcomes occurred in pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection,” the CDC noted, and it is not known “whether they were caused by Zika virus infection or other factors.”

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The total number of pregnant women with evidence of Zika virus infection reported in the U.S. territories surpassed that of the 50 states and the District of Columbia during the week ending July 28, 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 71 new cases of Zika in pregnant women reported in U.S. territories that week, bringing the total for the year to 493. The states and D.C. reported 46 new cases, for a total of 479 for the year, which puts the United States as a whole at 972 cases of confirmed Zika virus infection in pregnant women for 2016, the CDC reported Aug. 4.

Among the territories, the overwhelming majority of Zika cases are in Puerto Rico, which has reported 5,482 cases so far, compared with 44 in American Samoa and 22 in the U.S. Virgin Islands. In all, there have been 1,825 cases reported in the states and D.C., the CDC reported.

The territories, so far, have mostly avoided Zika-related pregnancy losses and birth defects, with only one case of pregnancy loss and no infants born with birth defects in 2016. Two more cases of infants born with birth defects were reported, however, in the states and D.C. for the week ending July 28, bringing the state/D.C. total to 15 for the year, but no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects were added to the six reported so far, the CDC announced.

“These outcomes occurred in pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection,” the CDC noted, and it is not known “whether they were caused by Zika virus infection or other factors.”

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

NIH launches trial of Zika vaccine candidate

A clinical trial to evaluate a candidate vaccine for Zika virus is underway, with preliminary results from the multisite phase I trial expected by the end of 2016.

Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, announced the trial and gave an update about other Zika virus vaccine development efforts during an Aug. 3 telephone briefing with reporters. The announcement came just days after the continental United States saw its first cases of local transmission of Zika virus in Florida.

The phase I clinical trial began on Aug. 2 and will evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of an investigational DNA vaccine for Zika virus. This vaccine is similar to one that early-stage trials have shown to be safe and immunogenic for West Nile virus, a flavivirus closely related to Zika. The Zika virus vaccine had promising preclinical results, Dr. Fauci said. “Preliminary immune responses that we’ve seen in a variety of animal models have been rather robust.”

The DNA vaccine uses a plasmid to deliver genes that code for specific Zika virus proteins. “When the plasmid expresses the envelope protein from the Zika virus, it does so in a way that mimics the virus,” provoking a host immune response that includes neutralizing antibodies and T cells, according to lead trial investigator Julie Ledgerwood, DO, chief of the clinical trials program at the NIAID’s Vaccine Research Center.

The phase I clinical trial will enroll 80 healthy volunteers, aged 18-35 years. All participants will receive the investigational Zika virus vaccine at their first visit, with vaccine delivery via a needle-free system that injects the vaccine directly into the deltoid muscle.

Forty participants will receive one additional dose of the vaccine, with half of those people receiving the additional dose at 8 weeks after the first vaccine, and the other half receiving the additional dose at 12 weeks after the first dose. The other 40 participants will receive two additional doses, with half receiving them at 4 and 8 weeks after the first vaccination, and the other half receiving the extra doses at 4 and 20 weeks. All participants will receive the same dose at each vaccination.

Participants will be asked to monitor their temperature daily for a week after each vaccine dose is received; they will also report any adverse events. The trial design provides for several follow-up visits to track safety and to measure immune response in 44 weeks of short-term follow-up. Additionally, two follow-up visits at 18 months and 2 years post vaccination will measure the durability of the immune response.

The clinical trial will be run at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., at Emory University in Atlanta, and at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore.

Initial safety and immune response data should be available by the end of 2016, Dr. Fauci said. If these data are promising, a phase II clinical trial will be launched in early 2017 in several Zika-endemic countries. The NIH has the in-house capability to manufacture the 2,500-5,000 doses of vaccine that the phase II trial is expected to require.

However, said Dr. Fauci, without congressional approval of additional funding for Zika virus vaccine efforts, the transition to a phase II clinical trial is far from certain. Interruption in funding would be “effectively impeding our smooth process on the vaccine development front,” he said. “When I say we are going to run out of money soon, I mean really soon.”

Dr. Fauci, in response to questions, said that he continues to be bullish on such platform-based approaches to vaccines. The DNA strategy, in particular, represents “a very convenient and easily scalable vaccine,” he said. “We are moving much more toward platform-based vaccines … because of their ease and convenience, and scaling up and rapidity.”

The scope of a vaccination program will depend on the endemicity of the virus in a given area, said Dr. Fauci. In an endemic area, “Ultimately, you want to get women of childbearing age, as well as their sexual partners,” he said. This means that target populations will be as young as possible, to make sure women and their partners are vaccinated by the time pregnancy becomes a possibility.

Other Zika virus vaccine development efforts underway at NIAID include a strategy that uses a live attenuated virus, an approach used for a dengue virus vaccine that is currently in a phase 3 clinical trial in Brazil, according to the agency’s website. Dengue and Zika are closely related viruses. Another investigational Zika virus vaccine uses genetic engineering to create a vaccine derived from vesicular stomatitis virus, which infects cattle. This strategy, also used in one approach to Ebola vaccination, is in the pre-clinical stage.

On Twitter @karioakes

A clinical trial to evaluate a candidate vaccine for Zika virus is underway, with preliminary results from the multisite phase I trial expected by the end of 2016.

Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, announced the trial and gave an update about other Zika virus vaccine development efforts during an Aug. 3 telephone briefing with reporters. The announcement came just days after the continental United States saw its first cases of local transmission of Zika virus in Florida.

The phase I clinical trial began on Aug. 2 and will evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of an investigational DNA vaccine for Zika virus. This vaccine is similar to one that early-stage trials have shown to be safe and immunogenic for West Nile virus, a flavivirus closely related to Zika. The Zika virus vaccine had promising preclinical results, Dr. Fauci said. “Preliminary immune responses that we’ve seen in a variety of animal models have been rather robust.”

The DNA vaccine uses a plasmid to deliver genes that code for specific Zika virus proteins. “When the plasmid expresses the envelope protein from the Zika virus, it does so in a way that mimics the virus,” provoking a host immune response that includes neutralizing antibodies and T cells, according to lead trial investigator Julie Ledgerwood, DO, chief of the clinical trials program at the NIAID’s Vaccine Research Center.

The phase I clinical trial will enroll 80 healthy volunteers, aged 18-35 years. All participants will receive the investigational Zika virus vaccine at their first visit, with vaccine delivery via a needle-free system that injects the vaccine directly into the deltoid muscle.

Forty participants will receive one additional dose of the vaccine, with half of those people receiving the additional dose at 8 weeks after the first vaccine, and the other half receiving the additional dose at 12 weeks after the first dose. The other 40 participants will receive two additional doses, with half receiving them at 4 and 8 weeks after the first vaccination, and the other half receiving the extra doses at 4 and 20 weeks. All participants will receive the same dose at each vaccination.

Participants will be asked to monitor their temperature daily for a week after each vaccine dose is received; they will also report any adverse events. The trial design provides for several follow-up visits to track safety and to measure immune response in 44 weeks of short-term follow-up. Additionally, two follow-up visits at 18 months and 2 years post vaccination will measure the durability of the immune response.

The clinical trial will be run at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., at Emory University in Atlanta, and at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore.

Initial safety and immune response data should be available by the end of 2016, Dr. Fauci said. If these data are promising, a phase II clinical trial will be launched in early 2017 in several Zika-endemic countries. The NIH has the in-house capability to manufacture the 2,500-5,000 doses of vaccine that the phase II trial is expected to require.

However, said Dr. Fauci, without congressional approval of additional funding for Zika virus vaccine efforts, the transition to a phase II clinical trial is far from certain. Interruption in funding would be “effectively impeding our smooth process on the vaccine development front,” he said. “When I say we are going to run out of money soon, I mean really soon.”

Dr. Fauci, in response to questions, said that he continues to be bullish on such platform-based approaches to vaccines. The DNA strategy, in particular, represents “a very convenient and easily scalable vaccine,” he said. “We are moving much more toward platform-based vaccines … because of their ease and convenience, and scaling up and rapidity.”

The scope of a vaccination program will depend on the endemicity of the virus in a given area, said Dr. Fauci. In an endemic area, “Ultimately, you want to get women of childbearing age, as well as their sexual partners,” he said. This means that target populations will be as young as possible, to make sure women and their partners are vaccinated by the time pregnancy becomes a possibility.

Other Zika virus vaccine development efforts underway at NIAID include a strategy that uses a live attenuated virus, an approach used for a dengue virus vaccine that is currently in a phase 3 clinical trial in Brazil, according to the agency’s website. Dengue and Zika are closely related viruses. Another investigational Zika virus vaccine uses genetic engineering to create a vaccine derived from vesicular stomatitis virus, which infects cattle. This strategy, also used in one approach to Ebola vaccination, is in the pre-clinical stage.

On Twitter @karioakes

A clinical trial to evaluate a candidate vaccine for Zika virus is underway, with preliminary results from the multisite phase I trial expected by the end of 2016.

Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, announced the trial and gave an update about other Zika virus vaccine development efforts during an Aug. 3 telephone briefing with reporters. The announcement came just days after the continental United States saw its first cases of local transmission of Zika virus in Florida.

The phase I clinical trial began on Aug. 2 and will evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of an investigational DNA vaccine for Zika virus. This vaccine is similar to one that early-stage trials have shown to be safe and immunogenic for West Nile virus, a flavivirus closely related to Zika. The Zika virus vaccine had promising preclinical results, Dr. Fauci said. “Preliminary immune responses that we’ve seen in a variety of animal models have been rather robust.”

The DNA vaccine uses a plasmid to deliver genes that code for specific Zika virus proteins. “When the plasmid expresses the envelope protein from the Zika virus, it does so in a way that mimics the virus,” provoking a host immune response that includes neutralizing antibodies and T cells, according to lead trial investigator Julie Ledgerwood, DO, chief of the clinical trials program at the NIAID’s Vaccine Research Center.

The phase I clinical trial will enroll 80 healthy volunteers, aged 18-35 years. All participants will receive the investigational Zika virus vaccine at their first visit, with vaccine delivery via a needle-free system that injects the vaccine directly into the deltoid muscle.

Forty participants will receive one additional dose of the vaccine, with half of those people receiving the additional dose at 8 weeks after the first vaccine, and the other half receiving the additional dose at 12 weeks after the first dose. The other 40 participants will receive two additional doses, with half receiving them at 4 and 8 weeks after the first vaccination, and the other half receiving the extra doses at 4 and 20 weeks. All participants will receive the same dose at each vaccination.

Participants will be asked to monitor their temperature daily for a week after each vaccine dose is received; they will also report any adverse events. The trial design provides for several follow-up visits to track safety and to measure immune response in 44 weeks of short-term follow-up. Additionally, two follow-up visits at 18 months and 2 years post vaccination will measure the durability of the immune response.

The clinical trial will be run at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., at Emory University in Atlanta, and at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore.

Initial safety and immune response data should be available by the end of 2016, Dr. Fauci said. If these data are promising, a phase II clinical trial will be launched in early 2017 in several Zika-endemic countries. The NIH has the in-house capability to manufacture the 2,500-5,000 doses of vaccine that the phase II trial is expected to require.

However, said Dr. Fauci, without congressional approval of additional funding for Zika virus vaccine efforts, the transition to a phase II clinical trial is far from certain. Interruption in funding would be “effectively impeding our smooth process on the vaccine development front,” he said. “When I say we are going to run out of money soon, I mean really soon.”

Dr. Fauci, in response to questions, said that he continues to be bullish on such platform-based approaches to vaccines. The DNA strategy, in particular, represents “a very convenient and easily scalable vaccine,” he said. “We are moving much more toward platform-based vaccines … because of their ease and convenience, and scaling up and rapidity.”

The scope of a vaccination program will depend on the endemicity of the virus in a given area, said Dr. Fauci. In an endemic area, “Ultimately, you want to get women of childbearing age, as well as their sexual partners,” he said. This means that target populations will be as young as possible, to make sure women and their partners are vaccinated by the time pregnancy becomes a possibility.

Other Zika virus vaccine development efforts underway at NIAID include a strategy that uses a live attenuated virus, an approach used for a dengue virus vaccine that is currently in a phase 3 clinical trial in Brazil, according to the agency’s website. Dengue and Zika are closely related viruses. Another investigational Zika virus vaccine uses genetic engineering to create a vaccine derived from vesicular stomatitis virus, which infects cattle. This strategy, also used in one approach to Ebola vaccination, is in the pre-clinical stage.

On Twitter @karioakes

Zika virus RNA detected in serum beyond previously estimated time frame

Zika virus RNA was detected in the serum of five pregnant women beyond previously estimated time frames, according to a new case series study.

“This report adds to the existing evidence that Zika virus RNA in serum may be detected longer than previously expected, an observation now reported among at least eight pregnant women,” reported Dr. Dana Meaney-Delman of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, and her colleagues wrote. (Obstet Gynecol. 2016. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001625).

Five pregnant women who had traveled to or lived in one or more countries with active Zika virus transmission and had prolonged detection of Zika virus RNA in serum were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, an enhanced surveillance initiative developed by the CDC to collect information on maternal exposure history, clinical presentation, laboratory testing, prenatal imaging, pregnancy screening and complications, fetal and neonatal outcomes, and infant development through the first year of life.

Prolonged detection was defined as the presence of Zika virus RNA detected in serum by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction at 14 or more days after symptom onset for symptomatic pregnant women or 21 or more days after last possible exposure to Zika virus for asymptomatic pregnant women. A previous study reported a mean Zika viral RNA duration of 9.9 days, with 14 days being the longest duration of Zika virus RNA detection in a nonpregnant person.

Among the four symptomatic pregnant women, Zika virus RNA was detected in the serum at 17, 23, 44, and 46 days following symptom onset. In the one asymptomatic pregnant woman, Zika virus RNA was detected in serum at 53 days after her travel from an area with active Zika transmission.

Among the five pregnancies, one is ongoing, one was aborted and the fetus tested positive for fetal Zika virus infection, and three resulted in live births of healthy neonates with no reported abnormalities.

“Several questions remain regarding the findings of prolonged detection of Zika virus RNA. Most notably, the duration of Zika virus RNA in serum requires further investigation to determine whether there is a correlation between prolonged viral RNA detection and the presence of infectious virus,” the researchers wrote.

Read the study results here.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Zika virus RNA was detected in the serum of five pregnant women beyond previously estimated time frames, according to a new case series study.

“This report adds to the existing evidence that Zika virus RNA in serum may be detected longer than previously expected, an observation now reported among at least eight pregnant women,” reported Dr. Dana Meaney-Delman of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, and her colleagues wrote. (Obstet Gynecol. 2016. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001625).

Five pregnant women who had traveled to or lived in one or more countries with active Zika virus transmission and had prolonged detection of Zika virus RNA in serum were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, an enhanced surveillance initiative developed by the CDC to collect information on maternal exposure history, clinical presentation, laboratory testing, prenatal imaging, pregnancy screening and complications, fetal and neonatal outcomes, and infant development through the first year of life.

Prolonged detection was defined as the presence of Zika virus RNA detected in serum by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction at 14 or more days after symptom onset for symptomatic pregnant women or 21 or more days after last possible exposure to Zika virus for asymptomatic pregnant women. A previous study reported a mean Zika viral RNA duration of 9.9 days, with 14 days being the longest duration of Zika virus RNA detection in a nonpregnant person.

Among the four symptomatic pregnant women, Zika virus RNA was detected in the serum at 17, 23, 44, and 46 days following symptom onset. In the one asymptomatic pregnant woman, Zika virus RNA was detected in serum at 53 days after her travel from an area with active Zika transmission.

Among the five pregnancies, one is ongoing, one was aborted and the fetus tested positive for fetal Zika virus infection, and three resulted in live births of healthy neonates with no reported abnormalities.

“Several questions remain regarding the findings of prolonged detection of Zika virus RNA. Most notably, the duration of Zika virus RNA in serum requires further investigation to determine whether there is a correlation between prolonged viral RNA detection and the presence of infectious virus,” the researchers wrote.

Read the study results here.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Zika virus RNA was detected in the serum of five pregnant women beyond previously estimated time frames, according to a new case series study.

“This report adds to the existing evidence that Zika virus RNA in serum may be detected longer than previously expected, an observation now reported among at least eight pregnant women,” reported Dr. Dana Meaney-Delman of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, and her colleagues wrote. (Obstet Gynecol. 2016. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001625).

Five pregnant women who had traveled to or lived in one or more countries with active Zika virus transmission and had prolonged detection of Zika virus RNA in serum were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, an enhanced surveillance initiative developed by the CDC to collect information on maternal exposure history, clinical presentation, laboratory testing, prenatal imaging, pregnancy screening and complications, fetal and neonatal outcomes, and infant development through the first year of life.

Prolonged detection was defined as the presence of Zika virus RNA detected in serum by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction at 14 or more days after symptom onset for symptomatic pregnant women or 21 or more days after last possible exposure to Zika virus for asymptomatic pregnant women. A previous study reported a mean Zika viral RNA duration of 9.9 days, with 14 days being the longest duration of Zika virus RNA detection in a nonpregnant person.

Among the four symptomatic pregnant women, Zika virus RNA was detected in the serum at 17, 23, 44, and 46 days following symptom onset. In the one asymptomatic pregnant woman, Zika virus RNA was detected in serum at 53 days after her travel from an area with active Zika transmission.

Among the five pregnancies, one is ongoing, one was aborted and the fetus tested positive for fetal Zika virus infection, and three resulted in live births of healthy neonates with no reported abnormalities.

“Several questions remain regarding the findings of prolonged detection of Zika virus RNA. Most notably, the duration of Zika virus RNA in serum requires further investigation to determine whether there is a correlation between prolonged viral RNA detection and the presence of infectious virus,” the researchers wrote.

Read the study results here.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

As Zika looms, are LARCs the answer?

In U.S. states where mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission is possible, adult women at risk for unintended pregnancy and sexually active high school girls are primarily using moderately effective and less effective contraceptive methods, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) – considered a highly effective method – are used by fewer than a quarter of nonpregnant women, about one-third of recently postpartum women, and fewer than one-tenth of sexually active high school girls, according to a report published Aug. 2 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530e2).

With locally transmitted cases of Zika virus infection increasing rapidly in Florida, the CDC is urging that the full range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be readily available and accessible to women who want to avoid or delay pregnancy.

“Given low rates of LARC use, states can implement strategies to remove barriers to the access and availability of LARC including high device costs, limited provider reimbursement, lack of training for providers serving women and adolescents on insertion and removal of LARC, provider lack of knowledge and misperceptions about LARC, limited availability of youth-friendly services that address adolescent confidentiality concerns, inadequate client-centered counseling, and low consumer awareness of the range of contraceptive methods available,” the CDC scientists wrote in the MMWR report.

Among nonpregnant women and recently postpartum women, the proportion not using any contraception ranged from 3.5% to 34.3%. Among sexually active high school girls, the proportion using no contraception ranged from 7.3% to 22.8%. The estimates of contraceptive use are based on 2011-2013 and 2015 survey data from four state-based surveillance systems.

The full MMWR report is available here.

On Twitter @maryellenny

In U.S. states where mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission is possible, adult women at risk for unintended pregnancy and sexually active high school girls are primarily using moderately effective and less effective contraceptive methods, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) – considered a highly effective method – are used by fewer than a quarter of nonpregnant women, about one-third of recently postpartum women, and fewer than one-tenth of sexually active high school girls, according to a report published Aug. 2 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530e2).

With locally transmitted cases of Zika virus infection increasing rapidly in Florida, the CDC is urging that the full range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be readily available and accessible to women who want to avoid or delay pregnancy.

“Given low rates of LARC use, states can implement strategies to remove barriers to the access and availability of LARC including high device costs, limited provider reimbursement, lack of training for providers serving women and adolescents on insertion and removal of LARC, provider lack of knowledge and misperceptions about LARC, limited availability of youth-friendly services that address adolescent confidentiality concerns, inadequate client-centered counseling, and low consumer awareness of the range of contraceptive methods available,” the CDC scientists wrote in the MMWR report.

Among nonpregnant women and recently postpartum women, the proportion not using any contraception ranged from 3.5% to 34.3%. Among sexually active high school girls, the proportion using no contraception ranged from 7.3% to 22.8%. The estimates of contraceptive use are based on 2011-2013 and 2015 survey data from four state-based surveillance systems.

The full MMWR report is available here.

On Twitter @maryellenny

In U.S. states where mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission is possible, adult women at risk for unintended pregnancy and sexually active high school girls are primarily using moderately effective and less effective contraceptive methods, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) – considered a highly effective method – are used by fewer than a quarter of nonpregnant women, about one-third of recently postpartum women, and fewer than one-tenth of sexually active high school girls, according to a report published Aug. 2 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530e2).

With locally transmitted cases of Zika virus infection increasing rapidly in Florida, the CDC is urging that the full range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be readily available and accessible to women who want to avoid or delay pregnancy.

“Given low rates of LARC use, states can implement strategies to remove barriers to the access and availability of LARC including high device costs, limited provider reimbursement, lack of training for providers serving women and adolescents on insertion and removal of LARC, provider lack of knowledge and misperceptions about LARC, limited availability of youth-friendly services that address adolescent confidentiality concerns, inadequate client-centered counseling, and low consumer awareness of the range of contraceptive methods available,” the CDC scientists wrote in the MMWR report.

Among nonpregnant women and recently postpartum women, the proportion not using any contraception ranged from 3.5% to 34.3%. Among sexually active high school girls, the proportion using no contraception ranged from 7.3% to 22.8%. The estimates of contraceptive use are based on 2011-2013 and 2015 survey data from four state-based surveillance systems.

The full MMWR report is available here.

On Twitter @maryellenny

FROM MMWR

CDC warns pregnant women to avoid Miami neighborhood due to Zika risk

Health officials in Florida have identified 10 new cases of locally transmitted Zika virus infections in the neighborhood just north of downtown Miami where four other cases were reported earlier.

Persistent mosquito populations in southern Florida are the leading cause of the disease’s growing incursion into the continental United States, according to Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This suggests that there is a risk of continued, active transmission of Zika in that area,” Dr. Frieden said Aug. 1 during a press call regarding the discovery of new cases by Florida officials.

The CDC is issuing new recommendations for people who either have visited, are currently visiting, or plan to visit this Miami neighborhood at any point after June 15, the earliest known date on which the infected individuals could have been exposed to the virus.

Women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant are advised to stay away from the neighborhood north of downtown Miami. Women who live in or around Miami, and who either are or plan to become pregnant, should take steps to protect themselves from mosquitoes. Individuals living in Miami should take precautions to prevent transmitting the disease sexually.

Additionally, the CDC is sending an Emergency Response Team to Florida to assist with efforts to quell the mosquito population and spread awareness about Zika virus prevention.

“These experts include individuals with extensive experience in Zika, in addressing pregnancy and birth defects, in mosquito control, in laboratory science, and community engagement,” Dr. Frieden said.

Dr. Frieden reiterated that controlling the local mosquito population is one of the most effective ways to stop ongoing Zika virus transmission. However, current efforts are being hampered by several factors, including small bodies of standing water near which mosquitoes are breeding, the inherent difficulty in killing this species of mosquito, and the possibility that the Aedes aegypti mosquito is resistant to the insecticides being used.

Vector control experts will work with health officials on the ground in Miami to conduct resistance testing on local mosquitoes, in order to confirm whether the insecticides are working. These tests could be done after just 1 week, but may take 3 or more weeks. Further discussion is also ongoing to determine other ways of bringing down the mosquito population.

“What we know about Zika is scary [but] in some ways, what we don’t know about Zika is even more unsettling,” said Dr. Frieden, who added that “at CDC, more than 1,600 of our experts have been working since January to learn more about Zika and protect the health of pregnant women and others.”

Health officials in Florida have identified 10 new cases of locally transmitted Zika virus infections in the neighborhood just north of downtown Miami where four other cases were reported earlier.

Persistent mosquito populations in southern Florida are the leading cause of the disease’s growing incursion into the continental United States, according to Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This suggests that there is a risk of continued, active transmission of Zika in that area,” Dr. Frieden said Aug. 1 during a press call regarding the discovery of new cases by Florida officials.

The CDC is issuing new recommendations for people who either have visited, are currently visiting, or plan to visit this Miami neighborhood at any point after June 15, the earliest known date on which the infected individuals could have been exposed to the virus.

Women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant are advised to stay away from the neighborhood north of downtown Miami. Women who live in or around Miami, and who either are or plan to become pregnant, should take steps to protect themselves from mosquitoes. Individuals living in Miami should take precautions to prevent transmitting the disease sexually.

Additionally, the CDC is sending an Emergency Response Team to Florida to assist with efforts to quell the mosquito population and spread awareness about Zika virus prevention.

“These experts include individuals with extensive experience in Zika, in addressing pregnancy and birth defects, in mosquito control, in laboratory science, and community engagement,” Dr. Frieden said.

Dr. Frieden reiterated that controlling the local mosquito population is one of the most effective ways to stop ongoing Zika virus transmission. However, current efforts are being hampered by several factors, including small bodies of standing water near which mosquitoes are breeding, the inherent difficulty in killing this species of mosquito, and the possibility that the Aedes aegypti mosquito is resistant to the insecticides being used.

Vector control experts will work with health officials on the ground in Miami to conduct resistance testing on local mosquitoes, in order to confirm whether the insecticides are working. These tests could be done after just 1 week, but may take 3 or more weeks. Further discussion is also ongoing to determine other ways of bringing down the mosquito population.

“What we know about Zika is scary [but] in some ways, what we don’t know about Zika is even more unsettling,” said Dr. Frieden, who added that “at CDC, more than 1,600 of our experts have been working since January to learn more about Zika and protect the health of pregnant women and others.”

Health officials in Florida have identified 10 new cases of locally transmitted Zika virus infections in the neighborhood just north of downtown Miami where four other cases were reported earlier.

Persistent mosquito populations in southern Florida are the leading cause of the disease’s growing incursion into the continental United States, according to Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This suggests that there is a risk of continued, active transmission of Zika in that area,” Dr. Frieden said Aug. 1 during a press call regarding the discovery of new cases by Florida officials.

The CDC is issuing new recommendations for people who either have visited, are currently visiting, or plan to visit this Miami neighborhood at any point after June 15, the earliest known date on which the infected individuals could have been exposed to the virus.

Women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant are advised to stay away from the neighborhood north of downtown Miami. Women who live in or around Miami, and who either are or plan to become pregnant, should take steps to protect themselves from mosquitoes. Individuals living in Miami should take precautions to prevent transmitting the disease sexually.

Additionally, the CDC is sending an Emergency Response Team to Florida to assist with efforts to quell the mosquito population and spread awareness about Zika virus prevention.

“These experts include individuals with extensive experience in Zika, in addressing pregnancy and birth defects, in mosquito control, in laboratory science, and community engagement,” Dr. Frieden said.

Dr. Frieden reiterated that controlling the local mosquito population is one of the most effective ways to stop ongoing Zika virus transmission. However, current efforts are being hampered by several factors, including small bodies of standing water near which mosquitoes are breeding, the inherent difficulty in killing this species of mosquito, and the possibility that the Aedes aegypti mosquito is resistant to the insecticides being used.

Vector control experts will work with health officials on the ground in Miami to conduct resistance testing on local mosquitoes, in order to confirm whether the insecticides are working. These tests could be done after just 1 week, but may take 3 or more weeks. Further discussion is also ongoing to determine other ways of bringing down the mosquito population.

“What we know about Zika is scary [but] in some ways, what we don’t know about Zika is even more unsettling,” said Dr. Frieden, who added that “at CDC, more than 1,600 of our experts have been working since January to learn more about Zika and protect the health of pregnant women and others.”

CDC confirms first cases of locally transmitted Zika in continental U.S.

Four cases of Zika virus infection in Florida have been confirmed as the first cases of local transmission of the Zika virus in the continental United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced.

“As we have anticipated, Zika is now here,” CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, said during a conference call with the media. “These cases are not unexpected [as] we’ve been saying for months, based on our experiences with chikungunya virus and dengue – which are viruses spread by the same mosquitoes that spread Zika – that individual cases and potentially small clusters of Zika are possible in the U.S.”

The cases in question occurred within several blocks of each other in Miami. The individuals were infected in early July, became symptomatic within a few days, and were diagnosed a few days later. Frieden explained that the CDC is proceeding as though these are confirmed cases of local mosquito-borne transmission, which he emphasized is not the same as simply confirming that a person has Zika virus infection.

“We’ve been working closely with Florida and we’ve been impressed by the comprehensiveness of their investigation,” Dr. Frieden said.

Since these cases became diagnosed, Florida officials have implemented “aggressive” mosquito control protocols, which include trying to significantly reduce the local mosquito population by spraying both adult and larval mosquitoes. Dr. Frieden reiterated that killing mosquitoes is one of the most effective ways to ensure local transmission does not occur. Screening of travelers coming into Florida has also been ramped up. Teams are also going door-to-door to eliminate any standing water that may be harboring mosquitoes.

“We’re coordinating closely with Florida, and will continue to support their efforts to assess the situation on a daily basis,” he said.

To reduce the chances of an individual contracting the virus through mosquitos, the CDC continues recommending mosquito repellent; wearing clothing that covers as much of the body as possible; avoiding any areas with still water; and staying in rooms that have air conditioning, fans, or mosquito nets.

“We have been working with state and local governments to prepare for the likelihood of local mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission in the continental United States and Hawaii,” said Lyle R. Petersen, MD, MPH, Director of the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases and Incident Manager for the CDC’s Zika Response efforts, in a statement. “We anticipate that there may be additional cases of ‘homegrown’ Zika in the coming weeks. Our top priority is to protect pregnant women from the potentially devastating harm caused by Zika.”

To combat the growing domestic Zika burden, the American Public Health Association called on Congress to allocate more funding, saying that the lack of Congressional support is directly leading to the disease’s incursion into the United States.

“Sadly, we knew this outcome was probable with each passing day that Congress failed to fund Zika protection and response [and] now Congress has adjourned for summer recess.” said Georges C. Benjamin, MD, Executive Director of the APHA, adding that “when Congress comes back in September, it must make sending bipartisan Zika legislation to the president a top priority.”

The American Medical Association echoed that position. “This should be a wake up call to Congress and the Administration that they must resolve their differences and immediately make the necessary resources available for our country to combat the growing threat of the virus,” Andrew W. Gurman, MD, AMA President, said in a statement.

The announcement of locally transmitted Zika virus cases in the continental U.S. comes on the heels of the CDC’s latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, which found that cases of Zika virus have increased dramatically in Puerto Rico. There have been 5,582 individuals diagnosed with Zika virus so far in 2016, as of July 7. That figure includes 672 pregnant women, with the rate of positive tests increasing from just 14% in February to 64% in June, according to the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530e1).

“Puerto Rico is in the midst of a Zika epidemic. The virus is silently and rapidly spreading in Puerto Rico,” Dr. Peterson said in a separate statement. “This could lead to hundreds of infants being born with microcephaly or other birth defects in the coming year. We must do all we can to protect pregnant women from Zika and to prepare to care for infants born with microcephaly.”

Four cases of Zika virus infection in Florida have been confirmed as the first cases of local transmission of the Zika virus in the continental United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced.

“As we have anticipated, Zika is now here,” CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, said during a conference call with the media. “These cases are not unexpected [as] we’ve been saying for months, based on our experiences with chikungunya virus and dengue – which are viruses spread by the same mosquitoes that spread Zika – that individual cases and potentially small clusters of Zika are possible in the U.S.”

The cases in question occurred within several blocks of each other in Miami. The individuals were infected in early July, became symptomatic within a few days, and were diagnosed a few days later. Frieden explained that the CDC is proceeding as though these are confirmed cases of local mosquito-borne transmission, which he emphasized is not the same as simply confirming that a person has Zika virus infection.

“We’ve been working closely with Florida and we’ve been impressed by the comprehensiveness of their investigation,” Dr. Frieden said.

Since these cases became diagnosed, Florida officials have implemented “aggressive” mosquito control protocols, which include trying to significantly reduce the local mosquito population by spraying both adult and larval mosquitoes. Dr. Frieden reiterated that killing mosquitoes is one of the most effective ways to ensure local transmission does not occur. Screening of travelers coming into Florida has also been ramped up. Teams are also going door-to-door to eliminate any standing water that may be harboring mosquitoes.

“We’re coordinating closely with Florida, and will continue to support their efforts to assess the situation on a daily basis,” he said.

To reduce the chances of an individual contracting the virus through mosquitos, the CDC continues recommending mosquito repellent; wearing clothing that covers as much of the body as possible; avoiding any areas with still water; and staying in rooms that have air conditioning, fans, or mosquito nets.

“We have been working with state and local governments to prepare for the likelihood of local mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission in the continental United States and Hawaii,” said Lyle R. Petersen, MD, MPH, Director of the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases and Incident Manager for the CDC’s Zika Response efforts, in a statement. “We anticipate that there may be additional cases of ‘homegrown’ Zika in the coming weeks. Our top priority is to protect pregnant women from the potentially devastating harm caused by Zika.”

To combat the growing domestic Zika burden, the American Public Health Association called on Congress to allocate more funding, saying that the lack of Congressional support is directly leading to the disease’s incursion into the United States.

“Sadly, we knew this outcome was probable with each passing day that Congress failed to fund Zika protection and response [and] now Congress has adjourned for summer recess.” said Georges C. Benjamin, MD, Executive Director of the APHA, adding that “when Congress comes back in September, it must make sending bipartisan Zika legislation to the president a top priority.”

The American Medical Association echoed that position. “This should be a wake up call to Congress and the Administration that they must resolve their differences and immediately make the necessary resources available for our country to combat the growing threat of the virus,” Andrew W. Gurman, MD, AMA President, said in a statement.

The announcement of locally transmitted Zika virus cases in the continental U.S. comes on the heels of the CDC’s latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, which found that cases of Zika virus have increased dramatically in Puerto Rico. There have been 5,582 individuals diagnosed with Zika virus so far in 2016, as of July 7. That figure includes 672 pregnant women, with the rate of positive tests increasing from just 14% in February to 64% in June, according to the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530e1).

“Puerto Rico is in the midst of a Zika epidemic. The virus is silently and rapidly spreading in Puerto Rico,” Dr. Peterson said in a separate statement. “This could lead to hundreds of infants being born with microcephaly or other birth defects in the coming year. We must do all we can to protect pregnant women from Zika and to prepare to care for infants born with microcephaly.”

Four cases of Zika virus infection in Florida have been confirmed as the first cases of local transmission of the Zika virus in the continental United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced.

“As we have anticipated, Zika is now here,” CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, said during a conference call with the media. “These cases are not unexpected [as] we’ve been saying for months, based on our experiences with chikungunya virus and dengue – which are viruses spread by the same mosquitoes that spread Zika – that individual cases and potentially small clusters of Zika are possible in the U.S.”

The cases in question occurred within several blocks of each other in Miami. The individuals were infected in early July, became symptomatic within a few days, and were diagnosed a few days later. Frieden explained that the CDC is proceeding as though these are confirmed cases of local mosquito-borne transmission, which he emphasized is not the same as simply confirming that a person has Zika virus infection.

“We’ve been working closely with Florida and we’ve been impressed by the comprehensiveness of their investigation,” Dr. Frieden said.

Since these cases became diagnosed, Florida officials have implemented “aggressive” mosquito control protocols, which include trying to significantly reduce the local mosquito population by spraying both adult and larval mosquitoes. Dr. Frieden reiterated that killing mosquitoes is one of the most effective ways to ensure local transmission does not occur. Screening of travelers coming into Florida has also been ramped up. Teams are also going door-to-door to eliminate any standing water that may be harboring mosquitoes.

“We’re coordinating closely with Florida, and will continue to support their efforts to assess the situation on a daily basis,” he said.

To reduce the chances of an individual contracting the virus through mosquitos, the CDC continues recommending mosquito repellent; wearing clothing that covers as much of the body as possible; avoiding any areas with still water; and staying in rooms that have air conditioning, fans, or mosquito nets.

“We have been working with state and local governments to prepare for the likelihood of local mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission in the continental United States and Hawaii,” said Lyle R. Petersen, MD, MPH, Director of the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases and Incident Manager for the CDC’s Zika Response efforts, in a statement. “We anticipate that there may be additional cases of ‘homegrown’ Zika in the coming weeks. Our top priority is to protect pregnant women from the potentially devastating harm caused by Zika.”

To combat the growing domestic Zika burden, the American Public Health Association called on Congress to allocate more funding, saying that the lack of Congressional support is directly leading to the disease’s incursion into the United States.

“Sadly, we knew this outcome was probable with each passing day that Congress failed to fund Zika protection and response [and] now Congress has adjourned for summer recess.” said Georges C. Benjamin, MD, Executive Director of the APHA, adding that “when Congress comes back in September, it must make sending bipartisan Zika legislation to the president a top priority.”

The American Medical Association echoed that position. “This should be a wake up call to Congress and the Administration that they must resolve their differences and immediately make the necessary resources available for our country to combat the growing threat of the virus,” Andrew W. Gurman, MD, AMA President, said in a statement.

The announcement of locally transmitted Zika virus cases in the continental U.S. comes on the heels of the CDC’s latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, which found that cases of Zika virus have increased dramatically in Puerto Rico. There have been 5,582 individuals diagnosed with Zika virus so far in 2016, as of July 7. That figure includes 672 pregnant women, with the rate of positive tests increasing from just 14% in February to 64% in June, according to the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530e1).

“Puerto Rico is in the midst of a Zika epidemic. The virus is silently and rapidly spreading in Puerto Rico,” Dr. Peterson said in a separate statement. “This could lead to hundreds of infants being born with microcephaly or other birth defects in the coming year. We must do all we can to protect pregnant women from Zika and to prepare to care for infants born with microcephaly.”

Skin rash in recent traveler? Think dengue fever

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.

Of the RNA virus serotypes 1-4, type 1 (DENV1) is the most common, and DENV2 and 3 are the most severe, but up to 40% of cases are asymptomatic, he noted, adding that the virus has an incubation period of 2-8 days. When symptoms occur, they are representative of acute febrile illness, and may include headache, high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain, and fatigue. A faint, itchy, macular rash commonly occurs at 2-6 days into the illness. According to the World Health Organization, a probable dengue fever case includes acute febrile illness and at least two of either headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations, leukopenia, or supportive serology.

“Sometimes the nose bleeds, the gums bleed, and there is bruising in the patient,” Dr. Martinez said. “Most important are retro-orbital pain and hemorrhagic manifestations, but also supportive serology.”

About 1% of patients progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome during the critical phase (days 4-7) of illness. This is most likely in those with serotypes 2 and 3, but can occur with all serotypes. Warning signs of such severe disease include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, pleural effusion or ascites, and of particular importance – mucosal bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

By the WHO definition, a diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever requires the presence of fever for at least 2-7 days, hemorrhagic tendencies, thrombocytopenia, and evidence and signs of plasma leakage; dengue shock syndrome requires these, as well as evidence of circulatory failure, such as rapid and weak pulse, narrow pulse pressure, hypotension, and shock.

It is important to maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever, particularly in anyone who has traveled to an endemic area in the 2 weeks before presentation. Serologic tests are important to detect anti-dengue antibodies. IgG is important, because its presence could suggest recurrent infection and thus the potential for severe disease, Dr. Martinez said. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for detection in the first 4-5 days of infection, and the NS1 rapid test can be positive on the first day, he noted.

The differential diagnosis for dengue fever is broad, and can include chikungunya fever, malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, drug eruption, and Zika fever.

Management of dengue fever includes bed rest, liquids, and mosquito net isolation to prevent re-infection, as more severe disease can occur after re-infection. Acetaminophen can be used for pain relief; aspirin should be avoided due to risk of bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

Hospitalization and supportive care are required for those with dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Intensive care unit admission may be required.

Of note, a vaccine against dengue fever has shown promise in phase III trials. The vaccine has been approved in Mexico and Brazil, but not yet in the U.S.

Dr Martinez reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.

Of the RNA virus serotypes 1-4, type 1 (DENV1) is the most common, and DENV2 and 3 are the most severe, but up to 40% of cases are asymptomatic, he noted, adding that the virus has an incubation period of 2-8 days. When symptoms occur, they are representative of acute febrile illness, and may include headache, high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain, and fatigue. A faint, itchy, macular rash commonly occurs at 2-6 days into the illness. According to the World Health Organization, a probable dengue fever case includes acute febrile illness and at least two of either headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations, leukopenia, or supportive serology.

“Sometimes the nose bleeds, the gums bleed, and there is bruising in the patient,” Dr. Martinez said. “Most important are retro-orbital pain and hemorrhagic manifestations, but also supportive serology.”

About 1% of patients progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome during the critical phase (days 4-7) of illness. This is most likely in those with serotypes 2 and 3, but can occur with all serotypes. Warning signs of such severe disease include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, pleural effusion or ascites, and of particular importance – mucosal bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

By the WHO definition, a diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever requires the presence of fever for at least 2-7 days, hemorrhagic tendencies, thrombocytopenia, and evidence and signs of plasma leakage; dengue shock syndrome requires these, as well as evidence of circulatory failure, such as rapid and weak pulse, narrow pulse pressure, hypotension, and shock.

It is important to maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever, particularly in anyone who has traveled to an endemic area in the 2 weeks before presentation. Serologic tests are important to detect anti-dengue antibodies. IgG is important, because its presence could suggest recurrent infection and thus the potential for severe disease, Dr. Martinez said. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for detection in the first 4-5 days of infection, and the NS1 rapid test can be positive on the first day, he noted.

The differential diagnosis for dengue fever is broad, and can include chikungunya fever, malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, drug eruption, and Zika fever.

Management of dengue fever includes bed rest, liquids, and mosquito net isolation to prevent re-infection, as more severe disease can occur after re-infection. Acetaminophen can be used for pain relief; aspirin should be avoided due to risk of bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

Hospitalization and supportive care are required for those with dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Intensive care unit admission may be required.

Of note, a vaccine against dengue fever has shown promise in phase III trials. The vaccine has been approved in Mexico and Brazil, but not yet in the U.S.

Dr Martinez reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.

Of the RNA virus serotypes 1-4, type 1 (DENV1) is the most common, and DENV2 and 3 are the most severe, but up to 40% of cases are asymptomatic, he noted, adding that the virus has an incubation period of 2-8 days. When symptoms occur, they are representative of acute febrile illness, and may include headache, high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain, and fatigue. A faint, itchy, macular rash commonly occurs at 2-6 days into the illness. According to the World Health Organization, a probable dengue fever case includes acute febrile illness and at least two of either headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations, leukopenia, or supportive serology.

“Sometimes the nose bleeds, the gums bleed, and there is bruising in the patient,” Dr. Martinez said. “Most important are retro-orbital pain and hemorrhagic manifestations, but also supportive serology.”

About 1% of patients progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome during the critical phase (days 4-7) of illness. This is most likely in those with serotypes 2 and 3, but can occur with all serotypes. Warning signs of such severe disease include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, pleural effusion or ascites, and of particular importance – mucosal bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

By the WHO definition, a diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever requires the presence of fever for at least 2-7 days, hemorrhagic tendencies, thrombocytopenia, and evidence and signs of plasma leakage; dengue shock syndrome requires these, as well as evidence of circulatory failure, such as rapid and weak pulse, narrow pulse pressure, hypotension, and shock.

It is important to maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever, particularly in anyone who has traveled to an endemic area in the 2 weeks before presentation. Serologic tests are important to detect anti-dengue antibodies. IgG is important, because its presence could suggest recurrent infection and thus the potential for severe disease, Dr. Martinez said. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for detection in the first 4-5 days of infection, and the NS1 rapid test can be positive on the first day, he noted.

The differential diagnosis for dengue fever is broad, and can include chikungunya fever, malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, drug eruption, and Zika fever.

Management of dengue fever includes bed rest, liquids, and mosquito net isolation to prevent re-infection, as more severe disease can occur after re-infection. Acetaminophen can be used for pain relief; aspirin should be avoided due to risk of bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

Hospitalization and supportive care are required for those with dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Intensive care unit admission may be required.

Of note, a vaccine against dengue fever has shown promise in phase III trials. The vaccine has been approved in Mexico and Brazil, but not yet in the U.S.

Dr Martinez reported having no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AAD SUMMER ACADEMY 2016

United States up to 855 cases of Zika in pregnant women

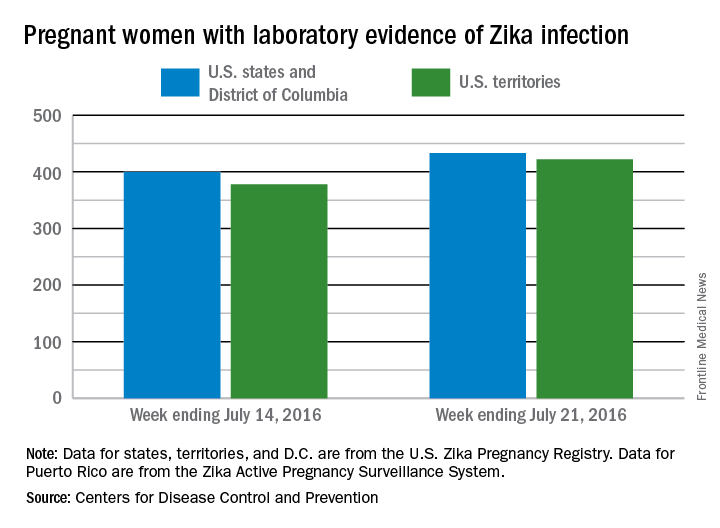

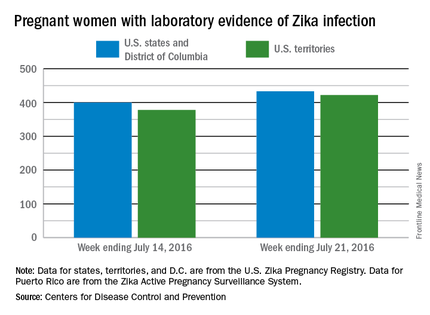

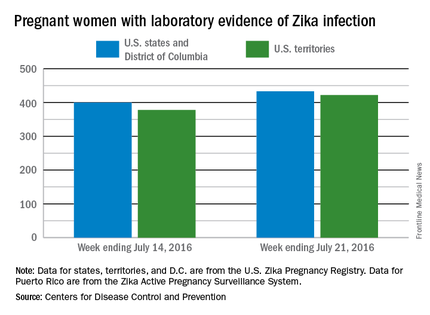

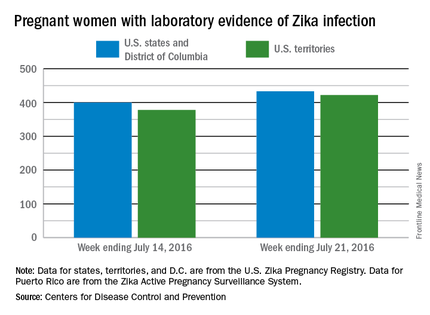

There was one live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects and 77 new cases of Zika among pregnant women reported during the week ending July 21, 2016, in the United States, but no additional Zika-related pregnancy losses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases bring the totals to 13 infants born with birth defects and 855 pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection. All of the infants with birth defects so far were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, which is where six of the seven Zika-related pregnancy losses occurred. There has been only one pregnancy loss in the U.S. territories, but the territories account for almost half (422) of the 855 pregnant women with Zika infection. Of the 77 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 44 occurred in the territories and 33 were in the states, the CDC reported July 28.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

There was one live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects and 77 new cases of Zika among pregnant women reported during the week ending July 21, 2016, in the United States, but no additional Zika-related pregnancy losses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases bring the totals to 13 infants born with birth defects and 855 pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection. All of the infants with birth defects so far were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, which is where six of the seven Zika-related pregnancy losses occurred. There has been only one pregnancy loss in the U.S. territories, but the territories account for almost half (422) of the 855 pregnant women with Zika infection. Of the 77 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 44 occurred in the territories and 33 were in the states, the CDC reported July 28.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

There was one live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects and 77 new cases of Zika among pregnant women reported during the week ending July 21, 2016, in the United States, but no additional Zika-related pregnancy losses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases bring the totals to 13 infants born with birth defects and 855 pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection. All of the infants with birth defects so far were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, which is where six of the seven Zika-related pregnancy losses occurred. There has been only one pregnancy loss in the U.S. territories, but the territories account for almost half (422) of the 855 pregnant women with Zika infection. Of the 77 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 44 occurred in the territories and 33 were in the states, the CDC reported July 28.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Risk of Zika virus remains low at Olympics

People attending the 2016 Summer Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro stand a low risk of contracting or spreading the Zika virus, says a new report in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Attendance at the Rio Olympics is estimated to be between 350,000 and 500,000, according to the report – written by Albert I. Ko, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn. and his colleagues – and in the worst-case scenario, the projected likelihood of infection will be between 1 in 56,300 and 1 in 6,200. This means that, at most, 80 people attending the games will contract the Zika virus (95% confidence interval, 63-98), while the lower bound of the estimate is a mere 6 individuals (95% CI, 2-12). Furthermore, only 1-16 individuals (95% CI, 0-4 and 9-24, respectively) of infected individuals are expected to be symptomatic (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 26. doi: 10.7326/M16-1628).

Data from the 2014 FIFA World Cup tournament – which also took place in Brazil – estimates that 53.3% of attendees will come from one of eight countries or regions: United States, Canada, Europe, Oceania, Japan, South Korea, and Israel, all of which are locations where mosquito-borne disease transmission rates are expected to be low. Individuals who contract Zika virus and take it back home with them are expected to number between 3 (95% CI, 0-7) and 37 (95% CI, 25-49), mainly because the Zika virus is only expected to take 9.9 days to naturally clear any infected individual.

“Most of the remaining travelers (30.2% of the total) are expected to return to Latin American countries already experiencing autochthonous ZIKV transmission, contributing 9.0 (0.0 to 29.7) to 116.0 (59.4 to 188.1) additional person-days of viremia,” the report states. “This effect is negligible relative to prevalent infections caused by ongoing transmission in these countries.”

Recently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also announced that chances of acquiring the Zika virus are low for those attending the 2016 Summer Olympics, and that only individuals from a small number of countries have any real danger of introducing the disease into a previously unaffected and potentially dangerous climate.

Sexual transmission of Zika virus remains a risk, however, the Annals report notes. People are urged to use condoms or abstain from sex during the Olympics in order to mitigate the risk of spreading the disease. Additionally, women who attend the games are best advised to delay getting pregnant for several weeks, if not months, after returning home. Women who are already pregnant should not attend the games, and everyone who attends the Olympics should wear mosquito repellent, long-sleeve shirts and pants, and use either a fan or a mosquito net in their hotel rooms to avoid getting bitten.

Dr. Ko and his coauthors declared no conflicts of interest.

People attending the 2016 Summer Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro stand a low risk of contracting or spreading the Zika virus, says a new report in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Attendance at the Rio Olympics is estimated to be between 350,000 and 500,000, according to the report – written by Albert I. Ko, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn. and his colleagues – and in the worst-case scenario, the projected likelihood of infection will be between 1 in 56,300 and 1 in 6,200. This means that, at most, 80 people attending the games will contract the Zika virus (95% confidence interval, 63-98), while the lower bound of the estimate is a mere 6 individuals (95% CI, 2-12). Furthermore, only 1-16 individuals (95% CI, 0-4 and 9-24, respectively) of infected individuals are expected to be symptomatic (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 26. doi: 10.7326/M16-1628).

Data from the 2014 FIFA World Cup tournament – which also took place in Brazil – estimates that 53.3% of attendees will come from one of eight countries or regions: United States, Canada, Europe, Oceania, Japan, South Korea, and Israel, all of which are locations where mosquito-borne disease transmission rates are expected to be low. Individuals who contract Zika virus and take it back home with them are expected to number between 3 (95% CI, 0-7) and 37 (95% CI, 25-49), mainly because the Zika virus is only expected to take 9.9 days to naturally clear any infected individual.