User login

CNS stimulant is first drug approved for binge-eating disorder

Lisdexamfetamine, the central nervous system stimulant marketed as Vyvanse, has been approved for treating binge-eating disorder in adults and is the first drug approved for this indication, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Jan. 30.

Approval was based on the results of two studies of 724 adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder. The studies found that the number of days per week participants engaged in binge-eating behavior decreased among those on Vyvanse, compared with those on placebo. Those on the drug also had fewer obsessive-compulsive binge-eating behaviors. Dry mouth, insomnia, increased heart rate, jitteriness, constipation, and anxiety were among the most common adverse effects associated with the drug in the studies.

This approval “provides physicians and patients with an effective option to help curb episodes of binge eating,” Dr. Mitchell Mathis, director of the division of psychiatry products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the statement. “Binge eating can cause serious health problems and difficulties with work, home, and social life.”

Lisdexamfetamine was first approved in 2007 as a treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in patients aged 6 years and older, and is a Schedule II controlled substance because of its high potential for abuse and dependence.

Prescriptions for the drug are dispensed with a Medication Guide, which provides information about its use and risks. “The most serious risks include psychiatric problems and heart complications, including sudden death in people who have heart problems or heart defects, and stroke and heart attack in adults. Central nervous system stimulants, like Vyvanse, may cause psychotic or manic symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusional thinking, or mania, even in individuals without a prior history of psychotic illness,” the FDA statement said.

Vyvanse, manufactured by Shire US, has not been studied as a weight loss agent “and is not approved for, or recommended for, weight loss,” according to the statement.

Serious adverse events thought to be associated with Vyvanse should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088.

Lisdexamfetamine, the central nervous system stimulant marketed as Vyvanse, has been approved for treating binge-eating disorder in adults and is the first drug approved for this indication, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Jan. 30.

Approval was based on the results of two studies of 724 adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder. The studies found that the number of days per week participants engaged in binge-eating behavior decreased among those on Vyvanse, compared with those on placebo. Those on the drug also had fewer obsessive-compulsive binge-eating behaviors. Dry mouth, insomnia, increased heart rate, jitteriness, constipation, and anxiety were among the most common adverse effects associated with the drug in the studies.

This approval “provides physicians and patients with an effective option to help curb episodes of binge eating,” Dr. Mitchell Mathis, director of the division of psychiatry products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the statement. “Binge eating can cause serious health problems and difficulties with work, home, and social life.”

Lisdexamfetamine was first approved in 2007 as a treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in patients aged 6 years and older, and is a Schedule II controlled substance because of its high potential for abuse and dependence.

Prescriptions for the drug are dispensed with a Medication Guide, which provides information about its use and risks. “The most serious risks include psychiatric problems and heart complications, including sudden death in people who have heart problems or heart defects, and stroke and heart attack in adults. Central nervous system stimulants, like Vyvanse, may cause psychotic or manic symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusional thinking, or mania, even in individuals without a prior history of psychotic illness,” the FDA statement said.

Vyvanse, manufactured by Shire US, has not been studied as a weight loss agent “and is not approved for, or recommended for, weight loss,” according to the statement.

Serious adverse events thought to be associated with Vyvanse should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088.

Lisdexamfetamine, the central nervous system stimulant marketed as Vyvanse, has been approved for treating binge-eating disorder in adults and is the first drug approved for this indication, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Jan. 30.

Approval was based on the results of two studies of 724 adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder. The studies found that the number of days per week participants engaged in binge-eating behavior decreased among those on Vyvanse, compared with those on placebo. Those on the drug also had fewer obsessive-compulsive binge-eating behaviors. Dry mouth, insomnia, increased heart rate, jitteriness, constipation, and anxiety were among the most common adverse effects associated with the drug in the studies.

This approval “provides physicians and patients with an effective option to help curb episodes of binge eating,” Dr. Mitchell Mathis, director of the division of psychiatry products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the statement. “Binge eating can cause serious health problems and difficulties with work, home, and social life.”

Lisdexamfetamine was first approved in 2007 as a treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in patients aged 6 years and older, and is a Schedule II controlled substance because of its high potential for abuse and dependence.

Prescriptions for the drug are dispensed with a Medication Guide, which provides information about its use and risks. “The most serious risks include psychiatric problems and heart complications, including sudden death in people who have heart problems or heart defects, and stroke and heart attack in adults. Central nervous system stimulants, like Vyvanse, may cause psychotic or manic symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusional thinking, or mania, even in individuals without a prior history of psychotic illness,” the FDA statement said.

Vyvanse, manufactured by Shire US, has not been studied as a weight loss agent “and is not approved for, or recommended for, weight loss,” according to the statement.

Serious adverse events thought to be associated with Vyvanse should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088.

FDA approves vagal blocking device for obesity

A novel implantable device that delivers electrical pulses to the intra-abdominal vagus nerve has been approved for treatment of obesity in adults, providing a less invasive alternative to bariatric surgery.

The Maestro Rechargeable System is “the first weight loss treatment device that targets the nerve pathway between the brain and the stomach that controls feelings of hunger and fullness,” according to the Food and Drug Administration statement released Jan. 14. The last device approved by the FDA for treatment of obesity was the Realize gastric band, in September 2007.

The device is approved for adults aged 18 and older with a body mass index of at least 40-45 kg/m2, or at least 35-39.9 kg/m2 with a related health condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol levels, who have tried to lose weight in a supervised weight management program within the past 5 years.

The system includes a rechargeable electrical pulse generator implanted into the lateral chest wall, connected to two electrical leads placed around the abdominal vagus nerve via a laparoscopic procedure. “It works by sending intermittent electrical pulses to the trunks in the abdominal vagus nerve, which is involved in regulating stomach emptying and signaling to the brain that the stomach feels empty or full,” the FDA statement said, adding: “Although it is known that the electric stimulation blocks nerve activity between the brain and the stomach, the specific mechanisms for weight loss due to use of the device are unknown.”

The manufacturer, EnteroMedics, refers to the treatment as “VBLOC therapy,” delivered by the Maestro System. The company expects that the device will be available this year “on a limited basis” at select Bariatric Centers of Excellence in the United States, according to a statement issued by EnteroMedics on Jan. 14.

FDA approval was based on the results of the ReCharge study of 233 patients with a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2; the device was activated in 157 patients, and the remaining patients had the device implanted but it was not activated and they served as controls.

After 12 months, those with the activated device lost 8.5% more excess weight than did the controls. Among those who had the device activated, almost 53% lost at least 20% of their excess weight and 38% lost at least 35% of their excess weight, according to the FDA.

The study did not meet the primary effectiveness endpoint, which was that those on active treatment would lose at least 10% more excess weight than would the controls. However, the majority of an FDA advisory panel that reviewed the data at a meeting in June 2014 supported approval, agreeing that the benefits outweighed the risks for the proposed indication. Panelists cited the fact that the study safety endpoint was met and that the device was effective in helping some people lose weight.

The FDA statement said the decision to approve the device was based on the panel’s recommendation, the study results, and an FDA survey of patient preferences for obesity devices, which found that “a group of patients would accept risks associated with this surgically implanted device for the amounts of weight loss expected to be provided by the device.”

As a condition for approval, EnteroMedics is required to conduct a 5-year postmarketing study that will collect safety and effectiveness data in at least 100 patients, including weight loss, adverse events, surgical revisions and explants and changes in obesity-related comorbidities, according to the FDA.

Serious adverse events in the ReCharge study were nausea, pain at the neuroregulator site, vomiting, and surgical complications; other adverse events were heartburn, problems swallowing, belching, mild nausea, and chest pain, the FDA noted.

The EnteroMedics statement says that contraindications for VBLOC therapy include liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, esophageal varices or an uncorrectable, clinically significant hiatal hernia; patients for whom magnetic resonance imaging or diathermy use is planned; patients at high risk for surgical complications; and patients who have permanently implanted, electrically-powered medical devices or gastrointestinal devices or prostheses, such as pacemakers, implanted defibrillators, or neurostimulators.

A novel implantable device that delivers electrical pulses to the intra-abdominal vagus nerve has been approved for treatment of obesity in adults, providing a less invasive alternative to bariatric surgery.

The Maestro Rechargeable System is “the first weight loss treatment device that targets the nerve pathway between the brain and the stomach that controls feelings of hunger and fullness,” according to the Food and Drug Administration statement released Jan. 14. The last device approved by the FDA for treatment of obesity was the Realize gastric band, in September 2007.

The device is approved for adults aged 18 and older with a body mass index of at least 40-45 kg/m2, or at least 35-39.9 kg/m2 with a related health condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol levels, who have tried to lose weight in a supervised weight management program within the past 5 years.

The system includes a rechargeable electrical pulse generator implanted into the lateral chest wall, connected to two electrical leads placed around the abdominal vagus nerve via a laparoscopic procedure. “It works by sending intermittent electrical pulses to the trunks in the abdominal vagus nerve, which is involved in regulating stomach emptying and signaling to the brain that the stomach feels empty or full,” the FDA statement said, adding: “Although it is known that the electric stimulation blocks nerve activity between the brain and the stomach, the specific mechanisms for weight loss due to use of the device are unknown.”

The manufacturer, EnteroMedics, refers to the treatment as “VBLOC therapy,” delivered by the Maestro System. The company expects that the device will be available this year “on a limited basis” at select Bariatric Centers of Excellence in the United States, according to a statement issued by EnteroMedics on Jan. 14.

FDA approval was based on the results of the ReCharge study of 233 patients with a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2; the device was activated in 157 patients, and the remaining patients had the device implanted but it was not activated and they served as controls.

After 12 months, those with the activated device lost 8.5% more excess weight than did the controls. Among those who had the device activated, almost 53% lost at least 20% of their excess weight and 38% lost at least 35% of their excess weight, according to the FDA.

The study did not meet the primary effectiveness endpoint, which was that those on active treatment would lose at least 10% more excess weight than would the controls. However, the majority of an FDA advisory panel that reviewed the data at a meeting in June 2014 supported approval, agreeing that the benefits outweighed the risks for the proposed indication. Panelists cited the fact that the study safety endpoint was met and that the device was effective in helping some people lose weight.

The FDA statement said the decision to approve the device was based on the panel’s recommendation, the study results, and an FDA survey of patient preferences for obesity devices, which found that “a group of patients would accept risks associated with this surgically implanted device for the amounts of weight loss expected to be provided by the device.”

As a condition for approval, EnteroMedics is required to conduct a 5-year postmarketing study that will collect safety and effectiveness data in at least 100 patients, including weight loss, adverse events, surgical revisions and explants and changes in obesity-related comorbidities, according to the FDA.

Serious adverse events in the ReCharge study were nausea, pain at the neuroregulator site, vomiting, and surgical complications; other adverse events were heartburn, problems swallowing, belching, mild nausea, and chest pain, the FDA noted.

The EnteroMedics statement says that contraindications for VBLOC therapy include liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, esophageal varices or an uncorrectable, clinically significant hiatal hernia; patients for whom magnetic resonance imaging or diathermy use is planned; patients at high risk for surgical complications; and patients who have permanently implanted, electrically-powered medical devices or gastrointestinal devices or prostheses, such as pacemakers, implanted defibrillators, or neurostimulators.

A novel implantable device that delivers electrical pulses to the intra-abdominal vagus nerve has been approved for treatment of obesity in adults, providing a less invasive alternative to bariatric surgery.

The Maestro Rechargeable System is “the first weight loss treatment device that targets the nerve pathway between the brain and the stomach that controls feelings of hunger and fullness,” according to the Food and Drug Administration statement released Jan. 14. The last device approved by the FDA for treatment of obesity was the Realize gastric band, in September 2007.

The device is approved for adults aged 18 and older with a body mass index of at least 40-45 kg/m2, or at least 35-39.9 kg/m2 with a related health condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol levels, who have tried to lose weight in a supervised weight management program within the past 5 years.

The system includes a rechargeable electrical pulse generator implanted into the lateral chest wall, connected to two electrical leads placed around the abdominal vagus nerve via a laparoscopic procedure. “It works by sending intermittent electrical pulses to the trunks in the abdominal vagus nerve, which is involved in regulating stomach emptying and signaling to the brain that the stomach feels empty or full,” the FDA statement said, adding: “Although it is known that the electric stimulation blocks nerve activity between the brain and the stomach, the specific mechanisms for weight loss due to use of the device are unknown.”

The manufacturer, EnteroMedics, refers to the treatment as “VBLOC therapy,” delivered by the Maestro System. The company expects that the device will be available this year “on a limited basis” at select Bariatric Centers of Excellence in the United States, according to a statement issued by EnteroMedics on Jan. 14.

FDA approval was based on the results of the ReCharge study of 233 patients with a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2; the device was activated in 157 patients, and the remaining patients had the device implanted but it was not activated and they served as controls.

After 12 months, those with the activated device lost 8.5% more excess weight than did the controls. Among those who had the device activated, almost 53% lost at least 20% of their excess weight and 38% lost at least 35% of their excess weight, according to the FDA.

The study did not meet the primary effectiveness endpoint, which was that those on active treatment would lose at least 10% more excess weight than would the controls. However, the majority of an FDA advisory panel that reviewed the data at a meeting in June 2014 supported approval, agreeing that the benefits outweighed the risks for the proposed indication. Panelists cited the fact that the study safety endpoint was met and that the device was effective in helping some people lose weight.

The FDA statement said the decision to approve the device was based on the panel’s recommendation, the study results, and an FDA survey of patient preferences for obesity devices, which found that “a group of patients would accept risks associated with this surgically implanted device for the amounts of weight loss expected to be provided by the device.”

As a condition for approval, EnteroMedics is required to conduct a 5-year postmarketing study that will collect safety and effectiveness data in at least 100 patients, including weight loss, adverse events, surgical revisions and explants and changes in obesity-related comorbidities, according to the FDA.

Serious adverse events in the ReCharge study were nausea, pain at the neuroregulator site, vomiting, and surgical complications; other adverse events were heartburn, problems swallowing, belching, mild nausea, and chest pain, the FDA noted.

The EnteroMedics statement says that contraindications for VBLOC therapy include liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, esophageal varices or an uncorrectable, clinically significant hiatal hernia; patients for whom magnetic resonance imaging or diathermy use is planned; patients at high risk for surgical complications; and patients who have permanently implanted, electrically-powered medical devices or gastrointestinal devices or prostheses, such as pacemakers, implanted defibrillators, or neurostimulators.

Bariatric surgery linked to lower mortality

Obese patients in the Veterans Administration health system who underwent bariatric surgery had lower all-cause mortality 5 and 10 years after the procedure than did matched patients who didn’t have bariatric surgery, according to a report published online Jan. 5 in JAMA.

In a retrospective cohort study of severely obese VA patients across the country, 2,500 who underwent bariatric surgery during 2000-2011 were matched for body mass index (BMI), age, sex, diabetes status, race, and area of residence with 7,462 who did not. The mean age of the study participants was 52-53 years, and the mean BMI was 46-47, said Dr. David E. Arterburn of the Group Health Research Institute and the University of Washington, both in Seattle, and his associates.

During a mean follow-up of approximately 7 years, there were 263 deaths in the surgical group and 1,277 in the control group. Estimated all-cause mortality was 6.4% at 5 years and 13.8% at 10 years for surgical patients, compared with 10.4% and 23.9%, respectively, for control subjects. Bariatric surgery was not associated with any difference in mortality for the first year of follow-up but was associated with lower mortality at 1-5 years (hazard ratio, 0.45) and at 5 or more years (HR, 0.47) of follow-up, the investigators said (JAMA 2015 January 5 [doi:10.1001;jama.2014.16968]). Over time, the association between bariatric surgery and lower mortality did not change even though criteria for patient selection and types of bariatric procedures did. And the association remained robust across several subgroups of patients, including patients who did and patients who did not have diabetes.

This VA study population was predominantly male and middle-aged, so the findings expand the evidence of bariatric surgery’s mortality benefit beyond that observed in previous studies of predominantly younger, female populations, Dr. Arterburn and his associates said.

This was a retrospective, nonrandomized, observational study, so the association identified between bariatric surgery and improved mortality cannot be considered causal on the basis of these results. “Only randomized clinical trials could provide definitive evidence that bariatric surgery improves survival,” but large enough RCTs would be very difficult to conduct and prohibitively expensive. So, at least for the present, both clinicians and patient must rely on observational research results such as those from this study to inform their treatment decisions regarding bariatric surgery, the investigators added.

Obese patients in the Veterans Administration health system who underwent bariatric surgery had lower all-cause mortality 5 and 10 years after the procedure than did matched patients who didn’t have bariatric surgery, according to a report published online Jan. 5 in JAMA.

In a retrospective cohort study of severely obese VA patients across the country, 2,500 who underwent bariatric surgery during 2000-2011 were matched for body mass index (BMI), age, sex, diabetes status, race, and area of residence with 7,462 who did not. The mean age of the study participants was 52-53 years, and the mean BMI was 46-47, said Dr. David E. Arterburn of the Group Health Research Institute and the University of Washington, both in Seattle, and his associates.

During a mean follow-up of approximately 7 years, there were 263 deaths in the surgical group and 1,277 in the control group. Estimated all-cause mortality was 6.4% at 5 years and 13.8% at 10 years for surgical patients, compared with 10.4% and 23.9%, respectively, for control subjects. Bariatric surgery was not associated with any difference in mortality for the first year of follow-up but was associated with lower mortality at 1-5 years (hazard ratio, 0.45) and at 5 or more years (HR, 0.47) of follow-up, the investigators said (JAMA 2015 January 5 [doi:10.1001;jama.2014.16968]). Over time, the association between bariatric surgery and lower mortality did not change even though criteria for patient selection and types of bariatric procedures did. And the association remained robust across several subgroups of patients, including patients who did and patients who did not have diabetes.

This VA study population was predominantly male and middle-aged, so the findings expand the evidence of bariatric surgery’s mortality benefit beyond that observed in previous studies of predominantly younger, female populations, Dr. Arterburn and his associates said.

This was a retrospective, nonrandomized, observational study, so the association identified between bariatric surgery and improved mortality cannot be considered causal on the basis of these results. “Only randomized clinical trials could provide definitive evidence that bariatric surgery improves survival,” but large enough RCTs would be very difficult to conduct and prohibitively expensive. So, at least for the present, both clinicians and patient must rely on observational research results such as those from this study to inform their treatment decisions regarding bariatric surgery, the investigators added.

Obese patients in the Veterans Administration health system who underwent bariatric surgery had lower all-cause mortality 5 and 10 years after the procedure than did matched patients who didn’t have bariatric surgery, according to a report published online Jan. 5 in JAMA.

In a retrospective cohort study of severely obese VA patients across the country, 2,500 who underwent bariatric surgery during 2000-2011 were matched for body mass index (BMI), age, sex, diabetes status, race, and area of residence with 7,462 who did not. The mean age of the study participants was 52-53 years, and the mean BMI was 46-47, said Dr. David E. Arterburn of the Group Health Research Institute and the University of Washington, both in Seattle, and his associates.

During a mean follow-up of approximately 7 years, there were 263 deaths in the surgical group and 1,277 in the control group. Estimated all-cause mortality was 6.4% at 5 years and 13.8% at 10 years for surgical patients, compared with 10.4% and 23.9%, respectively, for control subjects. Bariatric surgery was not associated with any difference in mortality for the first year of follow-up but was associated with lower mortality at 1-5 years (hazard ratio, 0.45) and at 5 or more years (HR, 0.47) of follow-up, the investigators said (JAMA 2015 January 5 [doi:10.1001;jama.2014.16968]). Over time, the association between bariatric surgery and lower mortality did not change even though criteria for patient selection and types of bariatric procedures did. And the association remained robust across several subgroups of patients, including patients who did and patients who did not have diabetes.

This VA study population was predominantly male and middle-aged, so the findings expand the evidence of bariatric surgery’s mortality benefit beyond that observed in previous studies of predominantly younger, female populations, Dr. Arterburn and his associates said.

This was a retrospective, nonrandomized, observational study, so the association identified between bariatric surgery and improved mortality cannot be considered causal on the basis of these results. “Only randomized clinical trials could provide definitive evidence that bariatric surgery improves survival,” but large enough RCTs would be very difficult to conduct and prohibitively expensive. So, at least for the present, both clinicians and patient must rely on observational research results such as those from this study to inform their treatment decisions regarding bariatric surgery, the investigators added.

Key clinical point: Obese patients who underwent bariatric surgery had lower mortality at 5 and 10 years, compared with matched control subjects.

Major finding: Estimated all-cause mortality was 6.4% at 5 years and 13.8% at 10 years for surgical patients, compared with 10.4% and 23.9%, respectively, for control subjects.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of mortality among 2,500 VA patients who had bariatric surgery during 2000-2011 and 7,462 matched patients who didn’t have the surgery.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Arterburn’s associates reported ties to Apollo Endosurgery, Bariatric Fusion, Cooper Surgical, Covidien, Daiichi Sankyo, and Amgen.

Diabetes drug liraglutide approved for weight loss indication

Liraglutide has been approved as a weight loss agent for people who are obese and for people who are overweight and have at least one weight-related comorbidity, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 23.

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist is approved as an adjunct to a reduced calorie diet and increased physical activity in obese adults with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater and in overweight adults with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater and at least one weight-related condition such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

Liraglutide, which is administered subcutaneously, was first approved in 2010 as a treatment for type 2 diabetes and is marketed for that indication as Victoza. Liraglutide will be marketed as Saxenda for the weight loss indication “and should not be used in combination with any other drug belonging to this class, including Victoza,” the FDA statement said. The liraglutide dose in Saxenda will be 3 mg; the dose in Victoza is 1.8 mg.

Approval for the weight loss indication was based on three studies of about 4,800 obese and overweight patients, who also received counseling about a reduced calorie diet and regular physical activity. In one study of patients who did not have diabetes, 62% of those on liraglutide and 34% of those on placebo lost at least 5% of their body weight over the course of a year. In another study of patients with type 2 diabetes, 49% of those on liraglutide and 16% of those on placebo lost at least 5% of their body weight in 1 year. Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, and hypoglycemia were among the common adverse events associated with treatment, according to the FDA.

“Patients using Saxenda should be evaluated after 16 weeks to determine if the treatment is working,” the FDA statement said. “If a patient has not lost at least 4% of baseline body weight, Saxenda should be discontinued as it is unlikely that the patient will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.”

Approval of Saxenda includes a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), which outlines a plan to inform health care professionals about the risks associated with liraglutide. The drug’s label includes a boxed warning about cases of thyroid C-cell tumors associated with the drug in rat studies, with a recommendation that the drug not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or by those with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. The manufacturer also is required to conduct several postmarketing studies, including a registry and at least 15 years of follow-up for MTC cases among patients treated with the drug.

Pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and renal impairment are among the serious adverse events associated with the drug, which “can also raise heart rate and should be discontinued in patients who experience a sustained increase in resting heart rate,” the FDA statement said.

Liraglutide is manufactured by Novo Nordisk.

Liraglutide has been approved as a weight loss agent for people who are obese and for people who are overweight and have at least one weight-related comorbidity, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 23.

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist is approved as an adjunct to a reduced calorie diet and increased physical activity in obese adults with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater and in overweight adults with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater and at least one weight-related condition such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

Liraglutide, which is administered subcutaneously, was first approved in 2010 as a treatment for type 2 diabetes and is marketed for that indication as Victoza. Liraglutide will be marketed as Saxenda for the weight loss indication “and should not be used in combination with any other drug belonging to this class, including Victoza,” the FDA statement said. The liraglutide dose in Saxenda will be 3 mg; the dose in Victoza is 1.8 mg.

Approval for the weight loss indication was based on three studies of about 4,800 obese and overweight patients, who also received counseling about a reduced calorie diet and regular physical activity. In one study of patients who did not have diabetes, 62% of those on liraglutide and 34% of those on placebo lost at least 5% of their body weight over the course of a year. In another study of patients with type 2 diabetes, 49% of those on liraglutide and 16% of those on placebo lost at least 5% of their body weight in 1 year. Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, and hypoglycemia were among the common adverse events associated with treatment, according to the FDA.

“Patients using Saxenda should be evaluated after 16 weeks to determine if the treatment is working,” the FDA statement said. “If a patient has not lost at least 4% of baseline body weight, Saxenda should be discontinued as it is unlikely that the patient will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.”

Approval of Saxenda includes a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), which outlines a plan to inform health care professionals about the risks associated with liraglutide. The drug’s label includes a boxed warning about cases of thyroid C-cell tumors associated with the drug in rat studies, with a recommendation that the drug not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or by those with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. The manufacturer also is required to conduct several postmarketing studies, including a registry and at least 15 years of follow-up for MTC cases among patients treated with the drug.

Pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and renal impairment are among the serious adverse events associated with the drug, which “can also raise heart rate and should be discontinued in patients who experience a sustained increase in resting heart rate,” the FDA statement said.

Liraglutide is manufactured by Novo Nordisk.

Liraglutide has been approved as a weight loss agent for people who are obese and for people who are overweight and have at least one weight-related comorbidity, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 23.

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist is approved as an adjunct to a reduced calorie diet and increased physical activity in obese adults with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater and in overweight adults with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater and at least one weight-related condition such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

Liraglutide, which is administered subcutaneously, was first approved in 2010 as a treatment for type 2 diabetes and is marketed for that indication as Victoza. Liraglutide will be marketed as Saxenda for the weight loss indication “and should not be used in combination with any other drug belonging to this class, including Victoza,” the FDA statement said. The liraglutide dose in Saxenda will be 3 mg; the dose in Victoza is 1.8 mg.

Approval for the weight loss indication was based on three studies of about 4,800 obese and overweight patients, who also received counseling about a reduced calorie diet and regular physical activity. In one study of patients who did not have diabetes, 62% of those on liraglutide and 34% of those on placebo lost at least 5% of their body weight over the course of a year. In another study of patients with type 2 diabetes, 49% of those on liraglutide and 16% of those on placebo lost at least 5% of their body weight in 1 year. Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, and hypoglycemia were among the common adverse events associated with treatment, according to the FDA.

“Patients using Saxenda should be evaluated after 16 weeks to determine if the treatment is working,” the FDA statement said. “If a patient has not lost at least 4% of baseline body weight, Saxenda should be discontinued as it is unlikely that the patient will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.”

Approval of Saxenda includes a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), which outlines a plan to inform health care professionals about the risks associated with liraglutide. The drug’s label includes a boxed warning about cases of thyroid C-cell tumors associated with the drug in rat studies, with a recommendation that the drug not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or by those with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. The manufacturer also is required to conduct several postmarketing studies, including a registry and at least 15 years of follow-up for MTC cases among patients treated with the drug.

Pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and renal impairment are among the serious adverse events associated with the drug, which “can also raise heart rate and should be discontinued in patients who experience a sustained increase in resting heart rate,” the FDA statement said.

Liraglutide is manufactured by Novo Nordisk.

Early nasoenteric feeding not beneficial in acute pancreatitis

Early nasoenteric tube feeding was not superior to an oral diet introduced at 72 hours in decreasing infection or death among patients with acute pancreatitis who were at high risk for complications, according to a report published online Nov. 20 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most current American and European guidelines recommend routine early enteral feeding for such patients. But “the methodologic quality of the trials that form the basis for these recommendations has been criticized ... [and] large, high-quality, randomized controlled trials that show an improved outcome with early enteral feeding are lacking,” said Dr. Olaf J. Bakker of the department of surgery, University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) Medical Center, and his associates in the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group.

The researchers compared the two feeding approaches in the Pancreatitis, Very Early Compared with Selective Delayed Start of Enteral Feeding (PYTHON) study, a randomized, controlled superiority trial involving 208 patients treated at six university medical centers and 13 large teaching hospitals in the Netherlands.

The participants were adults with a first episode of acute pancreatitis who were judged to be at high risk for complications when they presented to emergency departments. They were randomly assigned to receive either nasoenteric tube feeding initiated within 24 hours (102 patients in the early group), or oral feeding beginning at 72 hours (106 patients in the on-demand group) that was switched to nasoenteric tube feeding only if the oral intake was insufficient or not tolerated.

The primary endpoint of the study – a composite of major infection or death within 6 months – occurred in 30% of patients in the early group and 27% in the on-demand group, which did not demonstrate superiority.

“These findings do not support clinical guidelines recommending the early start of nasoenteric tube feeding in all patients with acute pancreatitis in order to reduce the risks of infection and death,” Dr. Bakker and his associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1983-93).

The rationale for early enteral feeding is that its trophic effect would stabilize the integrity of the gut mucosa, reducing inflammation and susceptibility to infection. In the study, however, early enteral feeding did not reduce any of the variables indicating inflammation, the investigators noted.

“A feeding tube frequently causes discomfort, excessive gagging, or esophagitis and is often dislodged or becomes obstructed,” so avoiding tube feeding when possible would reduce both patient discomfort and costs, the investigators added.

The PYTHON study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the ZonMw Health Care Efficiency Research Program, and Nutricia. Dr. Bakker reported having no financial disclosures; two of his associates had numerous ties to industry sources.

Early nasoenteric tube feeding was not superior to an oral diet introduced at 72 hours in decreasing infection or death among patients with acute pancreatitis who were at high risk for complications, according to a report published online Nov. 20 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most current American and European guidelines recommend routine early enteral feeding for such patients. But “the methodologic quality of the trials that form the basis for these recommendations has been criticized ... [and] large, high-quality, randomized controlled trials that show an improved outcome with early enteral feeding are lacking,” said Dr. Olaf J. Bakker of the department of surgery, University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) Medical Center, and his associates in the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group.

The researchers compared the two feeding approaches in the Pancreatitis, Very Early Compared with Selective Delayed Start of Enteral Feeding (PYTHON) study, a randomized, controlled superiority trial involving 208 patients treated at six university medical centers and 13 large teaching hospitals in the Netherlands.

The participants were adults with a first episode of acute pancreatitis who were judged to be at high risk for complications when they presented to emergency departments. They were randomly assigned to receive either nasoenteric tube feeding initiated within 24 hours (102 patients in the early group), or oral feeding beginning at 72 hours (106 patients in the on-demand group) that was switched to nasoenteric tube feeding only if the oral intake was insufficient or not tolerated.

The primary endpoint of the study – a composite of major infection or death within 6 months – occurred in 30% of patients in the early group and 27% in the on-demand group, which did not demonstrate superiority.

“These findings do not support clinical guidelines recommending the early start of nasoenteric tube feeding in all patients with acute pancreatitis in order to reduce the risks of infection and death,” Dr. Bakker and his associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1983-93).

The rationale for early enteral feeding is that its trophic effect would stabilize the integrity of the gut mucosa, reducing inflammation and susceptibility to infection. In the study, however, early enteral feeding did not reduce any of the variables indicating inflammation, the investigators noted.

“A feeding tube frequently causes discomfort, excessive gagging, or esophagitis and is often dislodged or becomes obstructed,” so avoiding tube feeding when possible would reduce both patient discomfort and costs, the investigators added.

The PYTHON study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the ZonMw Health Care Efficiency Research Program, and Nutricia. Dr. Bakker reported having no financial disclosures; two of his associates had numerous ties to industry sources.

Early nasoenteric tube feeding was not superior to an oral diet introduced at 72 hours in decreasing infection or death among patients with acute pancreatitis who were at high risk for complications, according to a report published online Nov. 20 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most current American and European guidelines recommend routine early enteral feeding for such patients. But “the methodologic quality of the trials that form the basis for these recommendations has been criticized ... [and] large, high-quality, randomized controlled trials that show an improved outcome with early enteral feeding are lacking,” said Dr. Olaf J. Bakker of the department of surgery, University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) Medical Center, and his associates in the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group.

The researchers compared the two feeding approaches in the Pancreatitis, Very Early Compared with Selective Delayed Start of Enteral Feeding (PYTHON) study, a randomized, controlled superiority trial involving 208 patients treated at six university medical centers and 13 large teaching hospitals in the Netherlands.

The participants were adults with a first episode of acute pancreatitis who were judged to be at high risk for complications when they presented to emergency departments. They were randomly assigned to receive either nasoenteric tube feeding initiated within 24 hours (102 patients in the early group), or oral feeding beginning at 72 hours (106 patients in the on-demand group) that was switched to nasoenteric tube feeding only if the oral intake was insufficient or not tolerated.

The primary endpoint of the study – a composite of major infection or death within 6 months – occurred in 30% of patients in the early group and 27% in the on-demand group, which did not demonstrate superiority.

“These findings do not support clinical guidelines recommending the early start of nasoenteric tube feeding in all patients with acute pancreatitis in order to reduce the risks of infection and death,” Dr. Bakker and his associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1983-93).

The rationale for early enteral feeding is that its trophic effect would stabilize the integrity of the gut mucosa, reducing inflammation and susceptibility to infection. In the study, however, early enteral feeding did not reduce any of the variables indicating inflammation, the investigators noted.

“A feeding tube frequently causes discomfort, excessive gagging, or esophagitis and is often dislodged or becomes obstructed,” so avoiding tube feeding when possible would reduce both patient discomfort and costs, the investigators added.

The PYTHON study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the ZonMw Health Care Efficiency Research Program, and Nutricia. Dr. Bakker reported having no financial disclosures; two of his associates had numerous ties to industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Early nasoenteric tube feeding was not superior to an oral diet at 72 hours in acute high-risk pancreatitis.

Major finding: The primary endpoint of the study – a composite of major infection or death within 6 months – occurred in 30% of patients who received early nasoenteric tube feeding and 27% who received an oral diet at 72 hours.

Data source: A multicenter, randomized, controlled superiority trial involving 208 adults with acute, high-risk pancreatitis who were followed for 6 months.

Disclosures: The PYTHON study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the ZonMw Health Care Efficiency Research Program, and Nutricia. Dr. Bakker reported having no financial disclosures; two of his associates had numerous ties to industry sources.

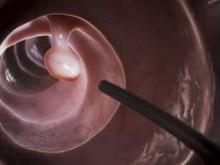

Intragastric balloons offer weight loss surgery alternative

BOSTON – Moderately obese patients who either don’t want or don’t qualify for bariatric surgery may be able to benefit from a reversible procedure using an investigational intragastric balloon.

In a randomized controlled trial, patients with a body mass index (BMI) from 30 to 40 kg/m2 who were assigned to receive a dual intragastric balloon (ReShape Duo) plus a diet and exercise regimen lost 25% of their excess weight, compared with only 11% of patients assigned to undergo a sham procedure plus diet and exercise, reported Dr. Jaime Ponce, medical director for the Bariatric Surgery program at Hamilton Medical Center in Dalton, Ga., and Memorial Hospital in Chattanooga, Tenn.

“The ReShape procedure is a reversible intervention that can be used in patients with BMI from 30 to 40 who are not ready for surgery or did not qualify for surgery. It was effective, as it showed a 2.2 times greater weight loss, compared with the diet group,” he said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

At 48 weeks, patients sustained on average 65% of the weight loss they had achieved at week 24, he said.

Two-chamber device

The dual intragastric balloon consists of two silicone balloons connected by a flexible shaft to provide migration resistance. The deflated device is inserted over a guide wire into the stomach in a transoral endoscopic procedure. Once in place, the device is inflated with a saline and methylene blue solution by a powered pump, up to a total volume of 750 to 900 cc. The mean duration of the procedure is 8 minutes Dr. Ponce said.

Barring problems, the device is left in place for 6 months and is then emptied, captured with a standard endoscopic snare, and removed, a process that takes a mean of 14 minutes.

Dr. Ponce and colleagues enrolled obese adults with a BMD from 30 to 40 kg/m2 and one or more obesity-related comorbidities to undergo either balloon insertion, diet and exercise (187 patients), or a sham procedure plus diet and exercise (139).

All patients had monthly counseling on diet and exercise as per obesity management guidelines from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute published in 2000.

The participants were blinded to treatment assignment for 24 weeks, at which time patients in the diet group could exit the study or, if they wished, receive the balloon and continue in the study for an additional 24 weeks. Patients who initially received the balloon remained in the study and continued diet and exercise during the same 24 weeks.

Balloons were successfully inserted in 99.6% of cases, and all inserted balloons were retrieved successfully. Three patients had serious adverse events related to retrieval: one case of pneumonia requiring hospitalization and antibiotics, one contained perforation of the cervical esophagus, also requiring hospitalization and antibiotics, and one proximal esophageal mucosal tear requiring hemostatic clips.

The trial met its primary endpoint of a greater than 7.5% difference between the balloon and control groups, with balloon receivers having a mean excess weight loss of 25.1%, compared with 11.3% for controls (P = .0041) in an intention to treat analysis, and 27.9% vs. 12.3%, respectively, in patients who completed the study (P = .0007).

At 48 weeks, patients initially assigned to receive the balloon had significant improvements in hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol levels (HDL up, LDL down), systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and waist and hip circumference.

Among all implanted participants, 11.6% had mild to moderate nausea and vomiting on day 3, which gradually declined over the study. In addition, 34.1% had abdominal pain they rated as mild to moderate on a visual analog scale,

The safety analysis, including all 264 patients who received the balloon initially or at week 24, showed no deaths, balloon migration, obstructions, or required surgeries. Most adverse events were gastrointestinal in nature, mild to moderate, and resolved within the first 30 days.

Investigators saw gastric ulcers in 93 of the 264 patients who received the balloon. They determined the cause to be the distal tip of the device contacting the incisural wall, where more than 95% of the ulcers were observed. The manufacturer made minor changes to lower the profile of the tip and make it smoother and softer, resulting a “dramatically reduced ulcer rate and size,” Dr. Ponce said.

In all, 15% of the balloons were retrieved early, 6% after 2 months, associated with ulcers, and 9% within 2 months of insertions because of device intolerance. The authors found shorter patients had significantly fewer problems when the balloons were inflated with 750 cc rather than 900 cc.

The balloons spontaneously deflated in 6% of participants, signaled by the presence of blue-green urine in about two-thirds of these patients. All of the devices in these cases were successfully retrieved without problems, Dr. Ponce said.

Dr. Manoel P. Galvao Neto of the Gastro Obeso Center in São Paulo, Brazil, the invited discussant, commented that the study was well designed and carried out, with a clear methodology and frank assessment of adverse events, and it met all of its primary endpoints.

Excretable balloon

In a separate pilot study, eight patients who swallowed a limited-duration, self-emptying balloon (Elipse) that is excreted through the bowel lost an average of 12% of excess body weight, reported Dr. Evzen Machytka of the department of clinical studies at the University of Ostrava, Czech Republic.

For the trial, investigators used a custom device designed to self-deflate in 6 weeks. The device is packaged in a capsule and is attached to a thin capillary tube. The patient swallows the balloon without endoscopy or anesthesia. The capsule dissolves quickly, and when gastric positioning of the balloon is confirmed with x-rays, the balloon is then filled with 450 mL saline, in a process that takes approximately 15 minutes.

After a prespecified time (6 weeks, in the case of the trial, 3 months in the device intended for market) a self-releasing valve opens, the balloon empties and is then excreted normally, Dr. Machytka said.

In the pilot trial, all eight balloons were safely excreted. One had deflated early because of a manufacturing defect, and one asymptomatic patient withdrew from the study because she “no longer enjoyed eating.” In both cases, the balloons were punctured via endoscopy but not retrieved, and were excreted normally in the stool 4 days later.

The investigators hope to receive marketing approval for the device in 2015, Dr. Machytka said.

BOSTON – Moderately obese patients who either don’t want or don’t qualify for bariatric surgery may be able to benefit from a reversible procedure using an investigational intragastric balloon.

In a randomized controlled trial, patients with a body mass index (BMI) from 30 to 40 kg/m2 who were assigned to receive a dual intragastric balloon (ReShape Duo) plus a diet and exercise regimen lost 25% of their excess weight, compared with only 11% of patients assigned to undergo a sham procedure plus diet and exercise, reported Dr. Jaime Ponce, medical director for the Bariatric Surgery program at Hamilton Medical Center in Dalton, Ga., and Memorial Hospital in Chattanooga, Tenn.

“The ReShape procedure is a reversible intervention that can be used in patients with BMI from 30 to 40 who are not ready for surgery or did not qualify for surgery. It was effective, as it showed a 2.2 times greater weight loss, compared with the diet group,” he said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

At 48 weeks, patients sustained on average 65% of the weight loss they had achieved at week 24, he said.

Two-chamber device

The dual intragastric balloon consists of two silicone balloons connected by a flexible shaft to provide migration resistance. The deflated device is inserted over a guide wire into the stomach in a transoral endoscopic procedure. Once in place, the device is inflated with a saline and methylene blue solution by a powered pump, up to a total volume of 750 to 900 cc. The mean duration of the procedure is 8 minutes Dr. Ponce said.

Barring problems, the device is left in place for 6 months and is then emptied, captured with a standard endoscopic snare, and removed, a process that takes a mean of 14 minutes.

Dr. Ponce and colleagues enrolled obese adults with a BMD from 30 to 40 kg/m2 and one or more obesity-related comorbidities to undergo either balloon insertion, diet and exercise (187 patients), or a sham procedure plus diet and exercise (139).

All patients had monthly counseling on diet and exercise as per obesity management guidelines from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute published in 2000.

The participants were blinded to treatment assignment for 24 weeks, at which time patients in the diet group could exit the study or, if they wished, receive the balloon and continue in the study for an additional 24 weeks. Patients who initially received the balloon remained in the study and continued diet and exercise during the same 24 weeks.

Balloons were successfully inserted in 99.6% of cases, and all inserted balloons were retrieved successfully. Three patients had serious adverse events related to retrieval: one case of pneumonia requiring hospitalization and antibiotics, one contained perforation of the cervical esophagus, also requiring hospitalization and antibiotics, and one proximal esophageal mucosal tear requiring hemostatic clips.

The trial met its primary endpoint of a greater than 7.5% difference between the balloon and control groups, with balloon receivers having a mean excess weight loss of 25.1%, compared with 11.3% for controls (P = .0041) in an intention to treat analysis, and 27.9% vs. 12.3%, respectively, in patients who completed the study (P = .0007).

At 48 weeks, patients initially assigned to receive the balloon had significant improvements in hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol levels (HDL up, LDL down), systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and waist and hip circumference.

Among all implanted participants, 11.6% had mild to moderate nausea and vomiting on day 3, which gradually declined over the study. In addition, 34.1% had abdominal pain they rated as mild to moderate on a visual analog scale,

The safety analysis, including all 264 patients who received the balloon initially or at week 24, showed no deaths, balloon migration, obstructions, or required surgeries. Most adverse events were gastrointestinal in nature, mild to moderate, and resolved within the first 30 days.

Investigators saw gastric ulcers in 93 of the 264 patients who received the balloon. They determined the cause to be the distal tip of the device contacting the incisural wall, where more than 95% of the ulcers were observed. The manufacturer made minor changes to lower the profile of the tip and make it smoother and softer, resulting a “dramatically reduced ulcer rate and size,” Dr. Ponce said.

In all, 15% of the balloons were retrieved early, 6% after 2 months, associated with ulcers, and 9% within 2 months of insertions because of device intolerance. The authors found shorter patients had significantly fewer problems when the balloons were inflated with 750 cc rather than 900 cc.

The balloons spontaneously deflated in 6% of participants, signaled by the presence of blue-green urine in about two-thirds of these patients. All of the devices in these cases were successfully retrieved without problems, Dr. Ponce said.

Dr. Manoel P. Galvao Neto of the Gastro Obeso Center in São Paulo, Brazil, the invited discussant, commented that the study was well designed and carried out, with a clear methodology and frank assessment of adverse events, and it met all of its primary endpoints.

Excretable balloon

In a separate pilot study, eight patients who swallowed a limited-duration, self-emptying balloon (Elipse) that is excreted through the bowel lost an average of 12% of excess body weight, reported Dr. Evzen Machytka of the department of clinical studies at the University of Ostrava, Czech Republic.

For the trial, investigators used a custom device designed to self-deflate in 6 weeks. The device is packaged in a capsule and is attached to a thin capillary tube. The patient swallows the balloon without endoscopy or anesthesia. The capsule dissolves quickly, and when gastric positioning of the balloon is confirmed with x-rays, the balloon is then filled with 450 mL saline, in a process that takes approximately 15 minutes.

After a prespecified time (6 weeks, in the case of the trial, 3 months in the device intended for market) a self-releasing valve opens, the balloon empties and is then excreted normally, Dr. Machytka said.

In the pilot trial, all eight balloons were safely excreted. One had deflated early because of a manufacturing defect, and one asymptomatic patient withdrew from the study because she “no longer enjoyed eating.” In both cases, the balloons were punctured via endoscopy but not retrieved, and were excreted normally in the stool 4 days later.

The investigators hope to receive marketing approval for the device in 2015, Dr. Machytka said.

BOSTON – Moderately obese patients who either don’t want or don’t qualify for bariatric surgery may be able to benefit from a reversible procedure using an investigational intragastric balloon.

In a randomized controlled trial, patients with a body mass index (BMI) from 30 to 40 kg/m2 who were assigned to receive a dual intragastric balloon (ReShape Duo) plus a diet and exercise regimen lost 25% of their excess weight, compared with only 11% of patients assigned to undergo a sham procedure plus diet and exercise, reported Dr. Jaime Ponce, medical director for the Bariatric Surgery program at Hamilton Medical Center in Dalton, Ga., and Memorial Hospital in Chattanooga, Tenn.

“The ReShape procedure is a reversible intervention that can be used in patients with BMI from 30 to 40 who are not ready for surgery or did not qualify for surgery. It was effective, as it showed a 2.2 times greater weight loss, compared with the diet group,” he said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

At 48 weeks, patients sustained on average 65% of the weight loss they had achieved at week 24, he said.

Two-chamber device

The dual intragastric balloon consists of two silicone balloons connected by a flexible shaft to provide migration resistance. The deflated device is inserted over a guide wire into the stomach in a transoral endoscopic procedure. Once in place, the device is inflated with a saline and methylene blue solution by a powered pump, up to a total volume of 750 to 900 cc. The mean duration of the procedure is 8 minutes Dr. Ponce said.

Barring problems, the device is left in place for 6 months and is then emptied, captured with a standard endoscopic snare, and removed, a process that takes a mean of 14 minutes.

Dr. Ponce and colleagues enrolled obese adults with a BMD from 30 to 40 kg/m2 and one or more obesity-related comorbidities to undergo either balloon insertion, diet and exercise (187 patients), or a sham procedure plus diet and exercise (139).

All patients had monthly counseling on diet and exercise as per obesity management guidelines from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute published in 2000.

The participants were blinded to treatment assignment for 24 weeks, at which time patients in the diet group could exit the study or, if they wished, receive the balloon and continue in the study for an additional 24 weeks. Patients who initially received the balloon remained in the study and continued diet and exercise during the same 24 weeks.

Balloons were successfully inserted in 99.6% of cases, and all inserted balloons were retrieved successfully. Three patients had serious adverse events related to retrieval: one case of pneumonia requiring hospitalization and antibiotics, one contained perforation of the cervical esophagus, also requiring hospitalization and antibiotics, and one proximal esophageal mucosal tear requiring hemostatic clips.

The trial met its primary endpoint of a greater than 7.5% difference between the balloon and control groups, with balloon receivers having a mean excess weight loss of 25.1%, compared with 11.3% for controls (P = .0041) in an intention to treat analysis, and 27.9% vs. 12.3%, respectively, in patients who completed the study (P = .0007).

At 48 weeks, patients initially assigned to receive the balloon had significant improvements in hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol levels (HDL up, LDL down), systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and waist and hip circumference.

Among all implanted participants, 11.6% had mild to moderate nausea and vomiting on day 3, which gradually declined over the study. In addition, 34.1% had abdominal pain they rated as mild to moderate on a visual analog scale,

The safety analysis, including all 264 patients who received the balloon initially or at week 24, showed no deaths, balloon migration, obstructions, or required surgeries. Most adverse events were gastrointestinal in nature, mild to moderate, and resolved within the first 30 days.

Investigators saw gastric ulcers in 93 of the 264 patients who received the balloon. They determined the cause to be the distal tip of the device contacting the incisural wall, where more than 95% of the ulcers were observed. The manufacturer made minor changes to lower the profile of the tip and make it smoother and softer, resulting a “dramatically reduced ulcer rate and size,” Dr. Ponce said.

In all, 15% of the balloons were retrieved early, 6% after 2 months, associated with ulcers, and 9% within 2 months of insertions because of device intolerance. The authors found shorter patients had significantly fewer problems when the balloons were inflated with 750 cc rather than 900 cc.

The balloons spontaneously deflated in 6% of participants, signaled by the presence of blue-green urine in about two-thirds of these patients. All of the devices in these cases were successfully retrieved without problems, Dr. Ponce said.

Dr. Manoel P. Galvao Neto of the Gastro Obeso Center in São Paulo, Brazil, the invited discussant, commented that the study was well designed and carried out, with a clear methodology and frank assessment of adverse events, and it met all of its primary endpoints.

Excretable balloon

In a separate pilot study, eight patients who swallowed a limited-duration, self-emptying balloon (Elipse) that is excreted through the bowel lost an average of 12% of excess body weight, reported Dr. Evzen Machytka of the department of clinical studies at the University of Ostrava, Czech Republic.

For the trial, investigators used a custom device designed to self-deflate in 6 weeks. The device is packaged in a capsule and is attached to a thin capillary tube. The patient swallows the balloon without endoscopy or anesthesia. The capsule dissolves quickly, and when gastric positioning of the balloon is confirmed with x-rays, the balloon is then filled with 450 mL saline, in a process that takes approximately 15 minutes.

After a prespecified time (6 weeks, in the case of the trial, 3 months in the device intended for market) a self-releasing valve opens, the balloon empties and is then excreted normally, Dr. Machytka said.

In the pilot trial, all eight balloons were safely excreted. One had deflated early because of a manufacturing defect, and one asymptomatic patient withdrew from the study because she “no longer enjoyed eating.” In both cases, the balloons were punctured via endoscopy but not retrieved, and were excreted normally in the stool 4 days later.

The investigators hope to receive marketing approval for the device in 2015, Dr. Machytka said.

AT OBESITY WEEK 2014

Key clinical point: Intragastric balloons provide a temporary reversible alternative to bariatric surgery procedures.

Major finding: ReShape Duo plus a diet and exercise regimen was associated with a 25% loss of excess weight, compared with 11% for controls.

Data source: Randomized single-blinded study in 326 obese adults.

Disclosures: Dr. Ponce’s study was supported by ReShape Medical. Dr. Ponce is a clinical trial investigator and consultant to the company. Dr. Machytka’s study was supported by Allurion Technologies. He is principal investigator and receives travel support from the company. Dr. Neto reported having no relevant disclosures.

Bariatric surgery’s long-term durability, complications still unknown

The greatest research need regarding bariatric surgery is the critical lack of information about long-term durability and complications of the procedures, according to a report published online Nov. 4 in JAMA Surgery.

Bariatric surgery “results in greater weight loss than nonsurgical treatment,” but that crucial information about long-term outcomes – “at least 10 years’ worth” – is still missing, said Dr. Bruce M. Wolfe of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Steven H. Belle, Ph.D., of the epidemiology department, University of Pittsburgh. They were speaking at a symposium sponsored by the National Institute of Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to review the best available evidence on bariatric surgery outcomes from the most recent large observational studies and randomized clinical trials.

Very large multicenter, randomized, controlled trials are the best type of study to provide this information but are prohibitively expensive, especially given the difficulty retaining participants in weight-loss studies. Any such trial would require very large numbers of treatment centers and patients to generate results that were adequately powered and generalizable, they wrote (JAMA Surg. 2014 Nov. 4 [doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2440]).

Future research must address the substantial variability in weight loss after bariatric surgery, as well as the equally substantial variability in its effect on diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and psychological and psychosocial issues. And long-term gastrointestinal complications must be a specific focus because these procedures alter the GI anatomy, and adverse effects may take many years to manifest.

“In summary, bariatric surgery offers the potential to address the morbidity and mortality of the obesity epidemic, but important research questions remain unresolved,” according to Dr. Wolfe and Dr. Belle.

The symposium was convened by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s division of cardiovascular sciences. Dr. Wolfe reported serving as a research consultant to EnteroMedics.

The greatest research need regarding bariatric surgery is the critical lack of information about long-term durability and complications of the procedures, according to a report published online Nov. 4 in JAMA Surgery.

Bariatric surgery “results in greater weight loss than nonsurgical treatment,” but that crucial information about long-term outcomes – “at least 10 years’ worth” – is still missing, said Dr. Bruce M. Wolfe of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Steven H. Belle, Ph.D., of the epidemiology department, University of Pittsburgh. They were speaking at a symposium sponsored by the National Institute of Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to review the best available evidence on bariatric surgery outcomes from the most recent large observational studies and randomized clinical trials.

Very large multicenter, randomized, controlled trials are the best type of study to provide this information but are prohibitively expensive, especially given the difficulty retaining participants in weight-loss studies. Any such trial would require very large numbers of treatment centers and patients to generate results that were adequately powered and generalizable, they wrote (JAMA Surg. 2014 Nov. 4 [doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2440]).

Future research must address the substantial variability in weight loss after bariatric surgery, as well as the equally substantial variability in its effect on diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and psychological and psychosocial issues. And long-term gastrointestinal complications must be a specific focus because these procedures alter the GI anatomy, and adverse effects may take many years to manifest.

“In summary, bariatric surgery offers the potential to address the morbidity and mortality of the obesity epidemic, but important research questions remain unresolved,” according to Dr. Wolfe and Dr. Belle.

The symposium was convened by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s division of cardiovascular sciences. Dr. Wolfe reported serving as a research consultant to EnteroMedics.

The greatest research need regarding bariatric surgery is the critical lack of information about long-term durability and complications of the procedures, according to a report published online Nov. 4 in JAMA Surgery.

Bariatric surgery “results in greater weight loss than nonsurgical treatment,” but that crucial information about long-term outcomes – “at least 10 years’ worth” – is still missing, said Dr. Bruce M. Wolfe of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Steven H. Belle, Ph.D., of the epidemiology department, University of Pittsburgh. They were speaking at a symposium sponsored by the National Institute of Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to review the best available evidence on bariatric surgery outcomes from the most recent large observational studies and randomized clinical trials.

Very large multicenter, randomized, controlled trials are the best type of study to provide this information but are prohibitively expensive, especially given the difficulty retaining participants in weight-loss studies. Any such trial would require very large numbers of treatment centers and patients to generate results that were adequately powered and generalizable, they wrote (JAMA Surg. 2014 Nov. 4 [doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2440]).

Future research must address the substantial variability in weight loss after bariatric surgery, as well as the equally substantial variability in its effect on diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and psychological and psychosocial issues. And long-term gastrointestinal complications must be a specific focus because these procedures alter the GI anatomy, and adverse effects may take many years to manifest.

“In summary, bariatric surgery offers the potential to address the morbidity and mortality of the obesity epidemic, but important research questions remain unresolved,” according to Dr. Wolfe and Dr. Belle.

The symposium was convened by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s division of cardiovascular sciences. Dr. Wolfe reported serving as a research consultant to EnteroMedics.

Key clinical point: The long-term durability and complications of bariatric surgery remain unknown because research is lacking.

Major finding: Crucial information about long-term outcomes – “at least 10 years’ worth” – is still missing.

Data source: A report from a National Institutes of Health symposium reviewing the best available evidence regarding bariatric surgery outcomes.

Disclosures: The symposium was convened by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s division of cardiovascular sciences. Dr. Wolfe reported serving as a research consultant to EnteroMedics.

Efficacy, not tolerability, of bowel prep is primary

The efficacy, not the tolerability, of bowel cleansing is the primary concern in patients undergoing colonoscopy, because of the substantial adverse consequences of inadequate bowel preparation, according to a consensus report published simultaneously in Gastroenterology, the American Journal of Gastroenterology, and Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

As many as 20%-25% of all colonoscopies reportedly have inadequate bowel cleansing, which is associated with lower rates of lesion detection, longer procedure times, and increased electrocautery risks, in addition to the excess costs and risks of repeat procedures. “Efficacy should be a higher priority than tolerability, [so] the choice of a bowel-cleansing regimen should be based on cleansing efficacy first and patient tolerability second,” said Dr. David A. Johnson of Eastern Veterans Administration Medical School, Norfolk (Va.) and his associates on the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.

The USMSTF comprised representatives from the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Gastroenterological Association, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, who compiled recommendations and wrote this report based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature concerning bowel preparation from 1980 to the present.

When selecting a bowel-cleansing regimen for patients, physicians should consider the patient’s medical history, medications, and, if applicable, the adequacy of bowel preparation for previous colonoscopies. High-quality evidence shows that a split-dose regimen of 4 liters of polyethylene glycol–electrolyte lavage solution (PEG-ELS) provides superior bowel cleansing to other doses and solutions. The second dose ideally should begin 4-6 hours and conclude at least 2 hours before the procedure time. However, same-day regimens are acceptable, especially for patients scheduled for an afternoon colonoscopy.

Using a split-dose regimen allows some flexibility with the diet on the day before the procedure. Instead of ingesting only clear liquids, patients can consume either a full liquid or a low-residue diet for part or all of the day preceding colonoscopy, which improves their tolerance of the bowel preparation.

Over-the-counter, nonapproved (by the FDA) bowel-cleansing agents have widely varying efficacy, ranging from adequate to excellent. They generally are safe, but “caution is required when using these agents in certain populations” such as patients with chronic kidney disease. The routine use of adjunctive agents intended to enhance purgation or visualization of the mucosa is not recommended, Dr. Johnson and his associates said (Gastroenterology 2014;147:903-24).

At present, the evidence is insufficient to allow recommendation of specific bowel-preparation regimens for special patient populations such as the elderly, children and adolescents, people with inflammatory bowel disease, patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, and people with spinal cord injury. However, sodium phosphate preparations should be avoided in the elderly, children, and people with IBD. Additional bowel purgatives can be considered for patients at risk for inadequate preparation, such as those with a history of constipation, those using opioids or other constipating medications, those who have undergone previous colon resection, and those with spinal cord injury.

The report also includes recommendations concerning patient education, the risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation, assessing the adequacy of bowel preparation before and during the procedure, and salvage options for cases in which preparation is inadequate. It is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.002.