User login

Is genetic testing valuable in the clinical management of epilepsy?

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

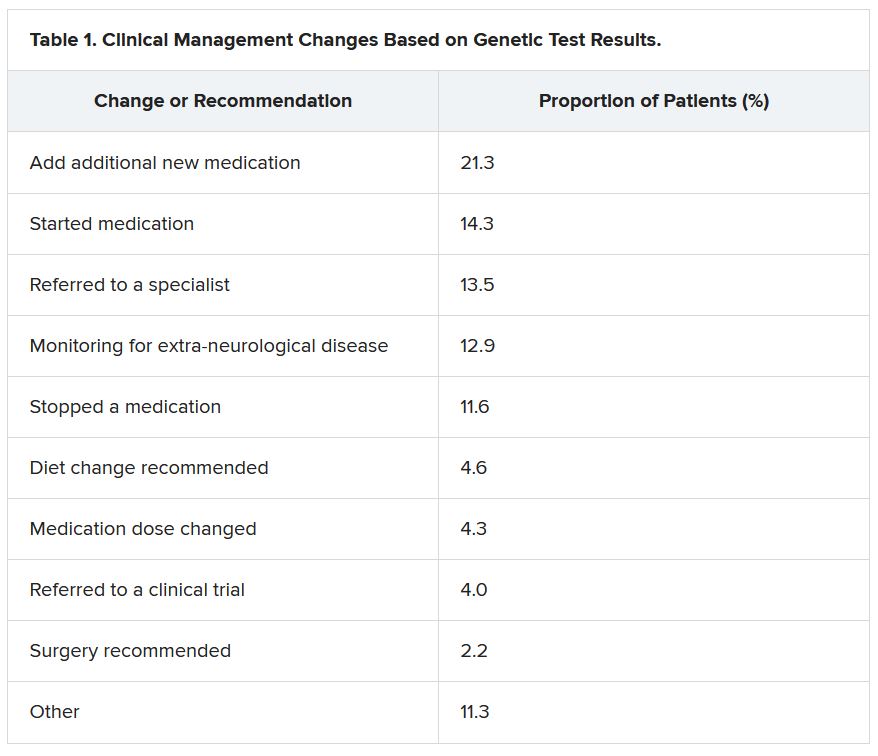

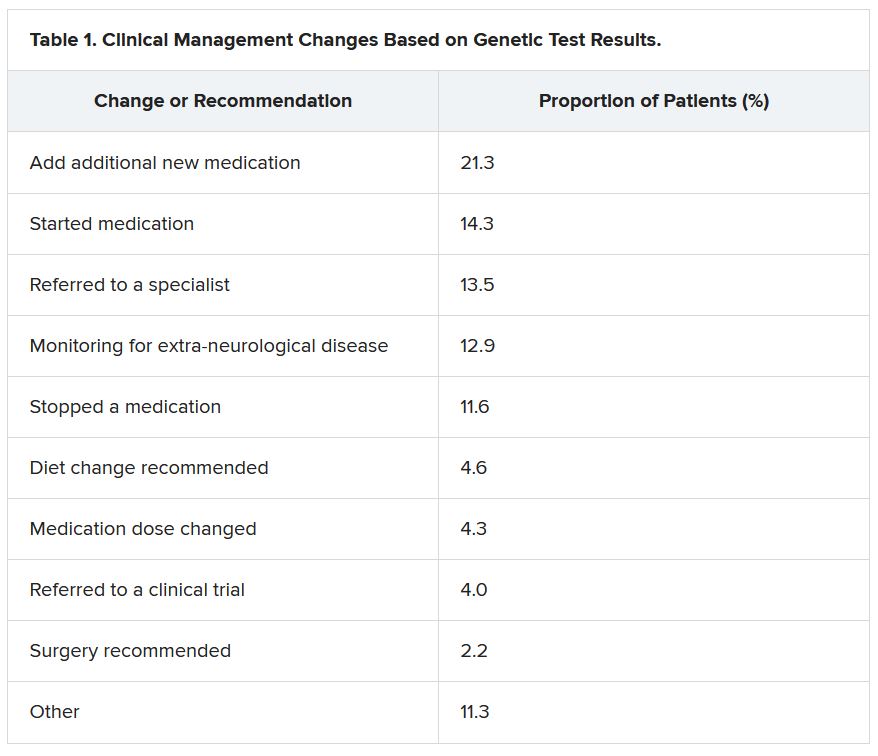

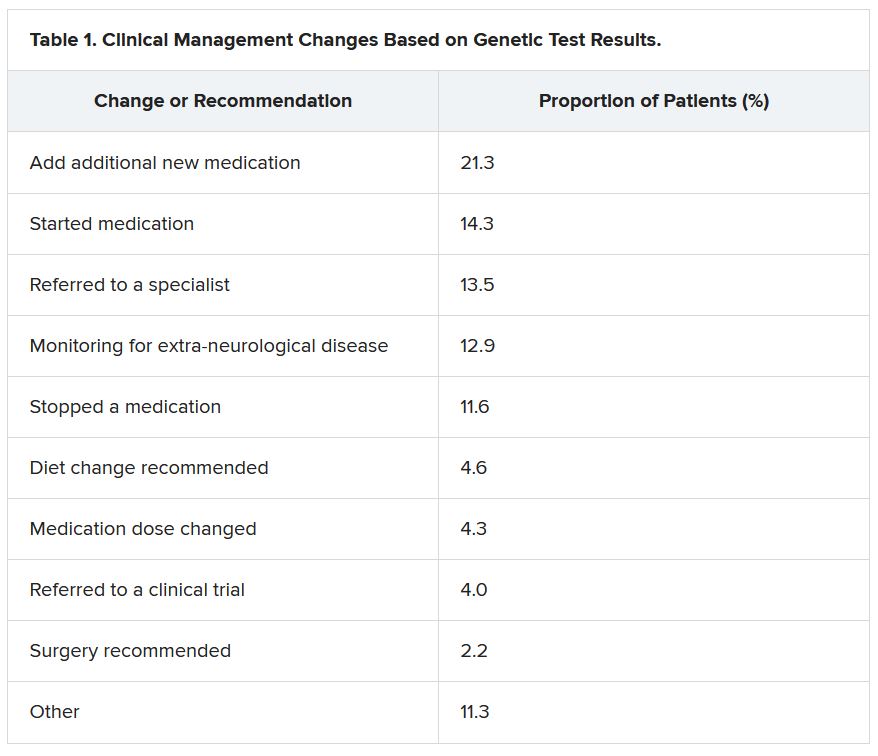

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

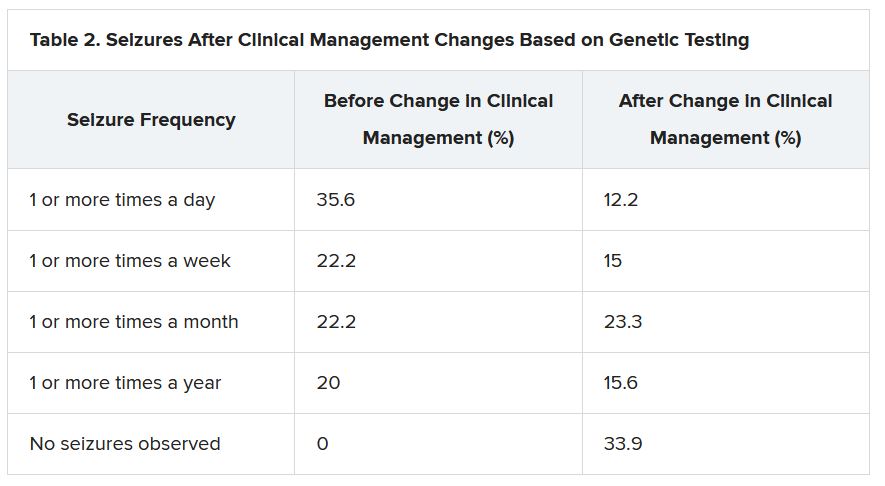

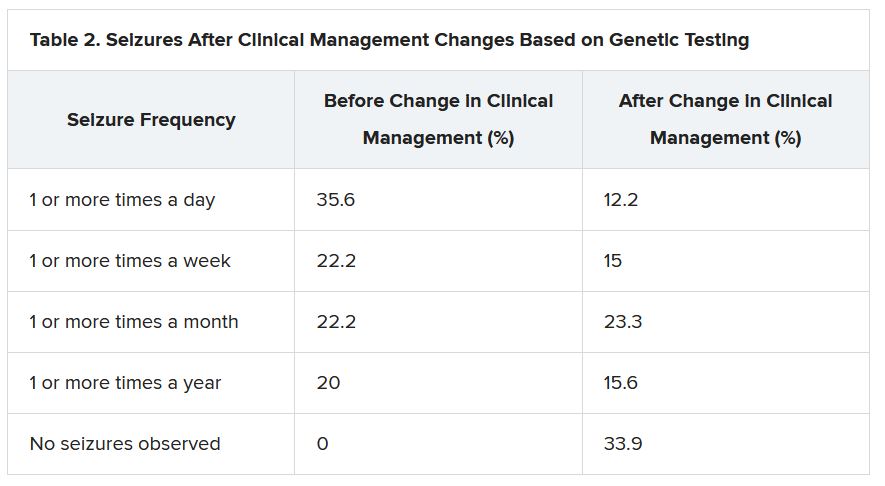

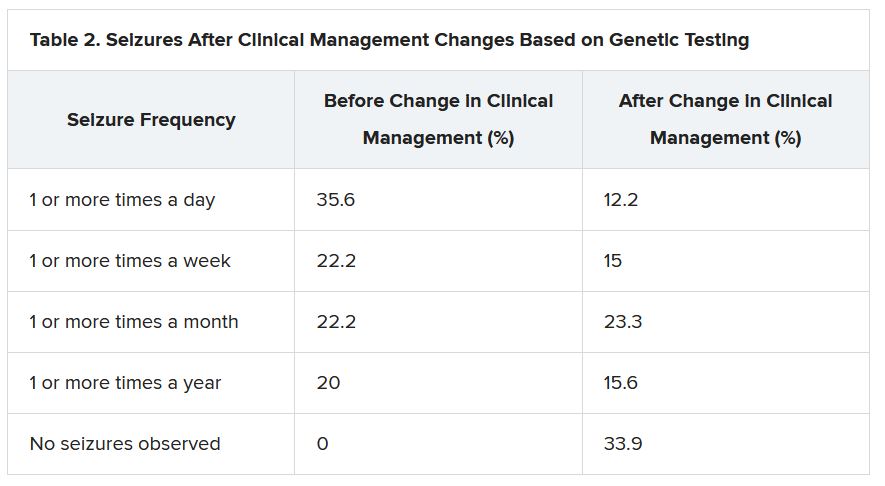

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From WCN 2021

Customized brain stimulation: New hope for severe depression

Personalized deep brain stimulation (DBS) appears to rapidly and effectively improve symptoms of treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

In a proof-of-concept study, investigators identified specific brain activity patterns responsible for a single patient’s severe depression and customized a DBS protocol to modulate the patterns. Results showed rapid and sustained improvement in depression scores.

“This study points the way to a new paradigm that is desperately needed in psychiatry,” Andrew Krystal, PhD, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, said in a news release.

“ by identifying and modulating the circuit in her brain that’s uniquely associated with her symptoms,” Dr. Krystal added.

The findings were published online Oct. 4 in Nature Medicine.

Closed-loop, on-demand stimulation

The patient was a 36-year-old woman with longstanding, severe, and treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. She was unresponsive to multiple antidepressant combinations and electroconvulsive therapy.

The researchers used intracranial electrophysiology and focal electrical stimulation to identify the specific pattern of electrical brain activity that correlated with her depressed mood.

They identified the right ventral striatum – which is involved in emotion, motivation, and reward – as the stimulation site that led to consistent, sustained, and dose-dependent improvement of symptoms and served as the neural biomarker.

In addition, the investigators identified a neural activity pattern in the amygdala that predicted both the mood symptoms, symptom severity, and stimulation efficacy.

The patient was implanted with the Food and Drug Administration–approved NeuroPace RNS System. The device was placed in the right hemisphere. A single sensing lead was positioned in the amygdala and the second stimulation lead was placed in the ventral striatum.

When the sensing lead detected the activity pattern associated with depression, the other lead delivered a tiny dose (1 milliampere/1 mA) of electricity for 6 seconds, which altered the neural activity and relieved mood symptoms.

Remission achieved

Once this personalized, closed-loop therapy was fully operational, the patient’s depression score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) dropped from 33 before turning treatment ON to 14 at the first ON-treatment assessment carried out after 12 days of stimulation. The score dropped below 10, representing remission, several months later.

The treatment also rapidly improved symptom severity, as measured daily with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-6) and visual analog scales.

“Success was predicated on a clinical mapping stage before chronic device placement, a strategy that has been utilized in epilepsy to map seizure foci in a personalized manner but has not previously been performed in other neuropsychiatric conditions,” the investigators wrote.

This patient represents “one of the first examples of precision psychiatry – a treatment tailored to an individual,” the study’s lead author, Katherine Scangos, MD, also with UCSF Weill Institute, said in an interview.

She added that the treatment “was personally tailored both spatially,” meaning at the brain location, and temporally – the time it was delivered.

“This is the first time a neural biomarker has been used to automatically trigger therapeutic stimulation in depression as a successful long-term treatment,” said Dr. Scangos. However, “we have a lot of work left to do,” she added.

“This study provides proof-of-principle that we can utilize a multimodal brain mapping approach to identify a personalized depression circuit and target that circuit with successful treatment. We will need to test the approach in more patients before we can determine its efficacy,” Dr. Scangos said.

First reliable biomarker in psychiatry

In a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre, Vladimir Litvak, PhD, with the Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, said that the study is interesting, noting that it is from “one of the leading groups in the field.”

The fact that depression symptoms can be treated in some patients by electrical stimulation of the ventral striatum is not new, Dr. Litvak said. However, what is “exciting” is that the authors identified a particular neural activity pattern in the amygdala as a reliable predictor of both symptom severity and stimulation effectiveness, he noted.

“Patterns of brain activity correlated with disease symptoms when testing over a large group of patients are commonly discovered. But there are just a handful of examples of patterns that are reliable enough to be predictive on a short time scale in a single patient,” said Dr. Litvak, who was not associated with the research.

“Furthermore, to my knowledge, this is the first example of such a reliable biomarker for psychiatric symptoms. The other examples were all for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and epilepsy,” he added.

He cautioned that this is a single case, but “if reproduced in additional patients, it will bring at least some psychiatric conditions into the domain of brain diseases that can be characterized and diagnosed objectively rather than based on symptoms alone.”

Dr. Litvak pointed out two other critical aspects of the study: the use of exploratory recordings and stimulation to determine the most effective treatment strategy, and the use of a closed-loop device that stimulates only when detecting the amygdala biomarker.

“It is hard to say based on this single case how important these will be in the future. There is no comparison to constant stimulation that might have worked as well because the implanted device used in the study is not suitable for that,” Dr. Litvak said.

It should also be noted that implanting multiple depth electrodes at different brain sites is a “traumatic invasive procedure only reserved to date for severe cases of drug-resistant epilepsy,” he said. “Furthermore, it only allows [researchers] to test a small number of candidate sites, so it relies heavily on prior knowledge.

“Once clinicians know better what to look for, it might be possible to avoid this procedure altogether by using noninvasive methods,” such as functional MRI or EEG, to match the right treatment option to a patient, Dr. Litvak concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund through the department of psychiatry at UCSF. Dr. Scangos has reported no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available in the original article. Dr. Litvak is participating in a research funding application to search for electrophysiological biomarkers of depression symptoms using invasive recordings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Personalized deep brain stimulation (DBS) appears to rapidly and effectively improve symptoms of treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

In a proof-of-concept study, investigators identified specific brain activity patterns responsible for a single patient’s severe depression and customized a DBS protocol to modulate the patterns. Results showed rapid and sustained improvement in depression scores.

“This study points the way to a new paradigm that is desperately needed in psychiatry,” Andrew Krystal, PhD, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, said in a news release.

“ by identifying and modulating the circuit in her brain that’s uniquely associated with her symptoms,” Dr. Krystal added.

The findings were published online Oct. 4 in Nature Medicine.

Closed-loop, on-demand stimulation

The patient was a 36-year-old woman with longstanding, severe, and treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. She was unresponsive to multiple antidepressant combinations and electroconvulsive therapy.

The researchers used intracranial electrophysiology and focal electrical stimulation to identify the specific pattern of electrical brain activity that correlated with her depressed mood.

They identified the right ventral striatum – which is involved in emotion, motivation, and reward – as the stimulation site that led to consistent, sustained, and dose-dependent improvement of symptoms and served as the neural biomarker.

In addition, the investigators identified a neural activity pattern in the amygdala that predicted both the mood symptoms, symptom severity, and stimulation efficacy.

The patient was implanted with the Food and Drug Administration–approved NeuroPace RNS System. The device was placed in the right hemisphere. A single sensing lead was positioned in the amygdala and the second stimulation lead was placed in the ventral striatum.

When the sensing lead detected the activity pattern associated with depression, the other lead delivered a tiny dose (1 milliampere/1 mA) of electricity for 6 seconds, which altered the neural activity and relieved mood symptoms.

Remission achieved

Once this personalized, closed-loop therapy was fully operational, the patient’s depression score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) dropped from 33 before turning treatment ON to 14 at the first ON-treatment assessment carried out after 12 days of stimulation. The score dropped below 10, representing remission, several months later.

The treatment also rapidly improved symptom severity, as measured daily with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-6) and visual analog scales.

“Success was predicated on a clinical mapping stage before chronic device placement, a strategy that has been utilized in epilepsy to map seizure foci in a personalized manner but has not previously been performed in other neuropsychiatric conditions,” the investigators wrote.

This patient represents “one of the first examples of precision psychiatry – a treatment tailored to an individual,” the study’s lead author, Katherine Scangos, MD, also with UCSF Weill Institute, said in an interview.

She added that the treatment “was personally tailored both spatially,” meaning at the brain location, and temporally – the time it was delivered.

“This is the first time a neural biomarker has been used to automatically trigger therapeutic stimulation in depression as a successful long-term treatment,” said Dr. Scangos. However, “we have a lot of work left to do,” she added.

“This study provides proof-of-principle that we can utilize a multimodal brain mapping approach to identify a personalized depression circuit and target that circuit with successful treatment. We will need to test the approach in more patients before we can determine its efficacy,” Dr. Scangos said.

First reliable biomarker in psychiatry

In a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre, Vladimir Litvak, PhD, with the Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, said that the study is interesting, noting that it is from “one of the leading groups in the field.”

The fact that depression symptoms can be treated in some patients by electrical stimulation of the ventral striatum is not new, Dr. Litvak said. However, what is “exciting” is that the authors identified a particular neural activity pattern in the amygdala as a reliable predictor of both symptom severity and stimulation effectiveness, he noted.

“Patterns of brain activity correlated with disease symptoms when testing over a large group of patients are commonly discovered. But there are just a handful of examples of patterns that are reliable enough to be predictive on a short time scale in a single patient,” said Dr. Litvak, who was not associated with the research.

“Furthermore, to my knowledge, this is the first example of such a reliable biomarker for psychiatric symptoms. The other examples were all for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and epilepsy,” he added.

He cautioned that this is a single case, but “if reproduced in additional patients, it will bring at least some psychiatric conditions into the domain of brain diseases that can be characterized and diagnosed objectively rather than based on symptoms alone.”

Dr. Litvak pointed out two other critical aspects of the study: the use of exploratory recordings and stimulation to determine the most effective treatment strategy, and the use of a closed-loop device that stimulates only when detecting the amygdala biomarker.

“It is hard to say based on this single case how important these will be in the future. There is no comparison to constant stimulation that might have worked as well because the implanted device used in the study is not suitable for that,” Dr. Litvak said.

It should also be noted that implanting multiple depth electrodes at different brain sites is a “traumatic invasive procedure only reserved to date for severe cases of drug-resistant epilepsy,” he said. “Furthermore, it only allows [researchers] to test a small number of candidate sites, so it relies heavily on prior knowledge.

“Once clinicians know better what to look for, it might be possible to avoid this procedure altogether by using noninvasive methods,” such as functional MRI or EEG, to match the right treatment option to a patient, Dr. Litvak concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund through the department of psychiatry at UCSF. Dr. Scangos has reported no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available in the original article. Dr. Litvak is participating in a research funding application to search for electrophysiological biomarkers of depression symptoms using invasive recordings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Personalized deep brain stimulation (DBS) appears to rapidly and effectively improve symptoms of treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

In a proof-of-concept study, investigators identified specific brain activity patterns responsible for a single patient’s severe depression and customized a DBS protocol to modulate the patterns. Results showed rapid and sustained improvement in depression scores.

“This study points the way to a new paradigm that is desperately needed in psychiatry,” Andrew Krystal, PhD, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, said in a news release.

“ by identifying and modulating the circuit in her brain that’s uniquely associated with her symptoms,” Dr. Krystal added.

The findings were published online Oct. 4 in Nature Medicine.

Closed-loop, on-demand stimulation

The patient was a 36-year-old woman with longstanding, severe, and treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. She was unresponsive to multiple antidepressant combinations and electroconvulsive therapy.

The researchers used intracranial electrophysiology and focal electrical stimulation to identify the specific pattern of electrical brain activity that correlated with her depressed mood.

They identified the right ventral striatum – which is involved in emotion, motivation, and reward – as the stimulation site that led to consistent, sustained, and dose-dependent improvement of symptoms and served as the neural biomarker.

In addition, the investigators identified a neural activity pattern in the amygdala that predicted both the mood symptoms, symptom severity, and stimulation efficacy.

The patient was implanted with the Food and Drug Administration–approved NeuroPace RNS System. The device was placed in the right hemisphere. A single sensing lead was positioned in the amygdala and the second stimulation lead was placed in the ventral striatum.

When the sensing lead detected the activity pattern associated with depression, the other lead delivered a tiny dose (1 milliampere/1 mA) of electricity for 6 seconds, which altered the neural activity and relieved mood symptoms.

Remission achieved

Once this personalized, closed-loop therapy was fully operational, the patient’s depression score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) dropped from 33 before turning treatment ON to 14 at the first ON-treatment assessment carried out after 12 days of stimulation. The score dropped below 10, representing remission, several months later.

The treatment also rapidly improved symptom severity, as measured daily with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-6) and visual analog scales.

“Success was predicated on a clinical mapping stage before chronic device placement, a strategy that has been utilized in epilepsy to map seizure foci in a personalized manner but has not previously been performed in other neuropsychiatric conditions,” the investigators wrote.

This patient represents “one of the first examples of precision psychiatry – a treatment tailored to an individual,” the study’s lead author, Katherine Scangos, MD, also with UCSF Weill Institute, said in an interview.

She added that the treatment “was personally tailored both spatially,” meaning at the brain location, and temporally – the time it was delivered.

“This is the first time a neural biomarker has been used to automatically trigger therapeutic stimulation in depression as a successful long-term treatment,” said Dr. Scangos. However, “we have a lot of work left to do,” she added.

“This study provides proof-of-principle that we can utilize a multimodal brain mapping approach to identify a personalized depression circuit and target that circuit with successful treatment. We will need to test the approach in more patients before we can determine its efficacy,” Dr. Scangos said.

First reliable biomarker in psychiatry

In a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre, Vladimir Litvak, PhD, with the Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, said that the study is interesting, noting that it is from “one of the leading groups in the field.”

The fact that depression symptoms can be treated in some patients by electrical stimulation of the ventral striatum is not new, Dr. Litvak said. However, what is “exciting” is that the authors identified a particular neural activity pattern in the amygdala as a reliable predictor of both symptom severity and stimulation effectiveness, he noted.

“Patterns of brain activity correlated with disease symptoms when testing over a large group of patients are commonly discovered. But there are just a handful of examples of patterns that are reliable enough to be predictive on a short time scale in a single patient,” said Dr. Litvak, who was not associated with the research.

“Furthermore, to my knowledge, this is the first example of such a reliable biomarker for psychiatric symptoms. The other examples were all for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and epilepsy,” he added.

He cautioned that this is a single case, but “if reproduced in additional patients, it will bring at least some psychiatric conditions into the domain of brain diseases that can be characterized and diagnosed objectively rather than based on symptoms alone.”

Dr. Litvak pointed out two other critical aspects of the study: the use of exploratory recordings and stimulation to determine the most effective treatment strategy, and the use of a closed-loop device that stimulates only when detecting the amygdala biomarker.

“It is hard to say based on this single case how important these will be in the future. There is no comparison to constant stimulation that might have worked as well because the implanted device used in the study is not suitable for that,” Dr. Litvak said.

It should also be noted that implanting multiple depth electrodes at different brain sites is a “traumatic invasive procedure only reserved to date for severe cases of drug-resistant epilepsy,” he said. “Furthermore, it only allows [researchers] to test a small number of candidate sites, so it relies heavily on prior knowledge.

“Once clinicians know better what to look for, it might be possible to avoid this procedure altogether by using noninvasive methods,” such as functional MRI or EEG, to match the right treatment option to a patient, Dr. Litvak concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund through the department of psychiatry at UCSF. Dr. Scangos has reported no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available in the original article. Dr. Litvak is participating in a research funding application to search for electrophysiological biomarkers of depression symptoms using invasive recordings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Data supporting cannabis for childhood epilepsy remain scarce

, according to two leading experts.

In a recent invited review article, Martin Kirkpatrick, MD, of the University of Dundee (Scotland), and Finbar O’Callaghan, MD, PhD, of University College London suggested that childhood epilepsy may be easy terrain for commercial interests to break ground, and from there, build their presence.

“Children with epilepsy are at risk of being used as the ‘Trojan horse’ for the cannabis industry,” Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan wrote in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology.

They noted that some of the first publicized success stories involving cannabis oil for epilepsy coincided with the rise of the medicinal and recreational cannabis markets, which will constitute an estimated 55-billion-dollar industry by 2027.

“Pediatric neurologists, imbued with the need to practice evidence-based medicine and wary of prescribing unlicensed medicines that had inadequate safety data, suddenly found themselves at odds with an array of vested interests and, most unfortunately, with the families of patients who were keen to try anything that would alleviate the effects of their child’s seizures,” the investigators wrote.

According to the review, fundamental questions about cannabis remain unanswered, including concerns about safety with long-term use, and the medicinal value of various plant components, such as myrcene, a terpene that gives cannabis its characteristic smell.

“A widely discussed issue is whether the terpenes add any therapeutic benefit, contributing to the so-called entourage effect of ‘whole-plant’ medicines,” the investigators wrote. “The concept is that all the constituents of the plant together create ‘the sum of all the parts that leads to the magic or power of cannabis.’ Although commonly referred to, there is little or no robust evidence to support the entourage effect as a credible clinical concept.”

Clinical evidence for treatment of pediatric epilepsy is also lacking, according to Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan.

“Unfortunately, apart from the studies of pure cannabidiol (CBD) in Lennox–Gastaut and Dravet syndromes and tuberous sclerosis complex, level I evidence in the field of CBMPs and refractory epilepsy is lacking,” they wrote.

While other experts have pointed out that lower-level evidence – such as patient-reported outcomes and observational data – have previously been sufficient for drug licensing, Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan noted that such exceptions “almost always” involve conditions without any effective treatments, or drugs that are undeniably effective.

“This is not the scenario with CBMPs,” they wrote, referring to current clinical data as “low-level” evidence “suggesting … possible efficacy.”

They highlighted concerns about placebo effect with open-label epilepsy studies, citing a randomized controlled trial for Dravet syndrome, in which 27% of patients given placebo had a 50% reduction in seizure frequency.

“We need carefully designed, good-quality CBMP studies that produce results on which we can rely,” Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan concluded. “We can then work with families to choose the best treatments for children and young people with epilepsy. We owe this to them.”

A therapy of last resort

Jerzy P. Szaflarski, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, agreed that data are lacking for the use of CBMPs with patients who have epilepsy and other neurologic conditions; however, he also suggested that Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan did not provide adequate real-world clinical context.

“Medical cannabis is not used as a first-, second-, or third-line therapy,” Dr. Szaflarski said. “It’s mostly used as a last resort in the sense that patients have already failed multiple other therapies.” In that respect, patients and parents are desperate to try anything that might work. “We have medical cannabis, and our patients want to try it, and at the point when multiple therapies have failed, it’s a reasonable option.”

While Dr. Szaflarski agreed that more high-quality clinical trials are needed, he also noted the practical challenges involved in such trials, largely because of variations in cannabis plants.

“The content of the cannabis plant changes depending on the day that it’s collected and the exposure to sun and how much water it has and what’s in the soil and many other things,” Dr. Szaflarski said. “It’s hard to get a very good, standardized product, and that’s why there needs to be a good-quality product delivered by the industry, which I have not seen thus far.”

For this reason, Dr. Szaflarski steers parents and patients away from over-the-counter CBMPs and toward Epidiolex, the only FDA-approved form of CBD.

“There is evidence that Epidiolex works,” he said. “I don’t know whether the products that are sold in a local cannabis store have the same high purity as Epidiolex. I tell [parents] that we should try Epidiolex first because it’s the one that is approved. But if it doesn’t work, we can go in that [other] direction.”

For those going the commercial route, Dr. Szaflarski advised close attention to product ingredients, to ensure that CBMPs are “devoid of any impurities, pesticides, fungicides, and other products that could be potentially dangerous.”

Parents considering CBMPs for their children also need to weigh concerns about long-term neurological safety, he added, noting that, on one hand, commercial products lack data, while on the other, epilepsy itself may cause harm.

“They need to consider the potential effects [of CBMPs] on their child’s brain and development versus … the effects of seizures on the brain,” Dr. Szaflarski said.

Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan disclosed an application for a National Institute for Health Research–funded randomized controlled trial on CBMPs and joint authorship of British Paediatric Neurology Association Guidance on the use of CBMPs in children and young people with epilepsy. Dr. Szaflarski disclosed a relationship with Greenwich Biosciences and several other cannabis companies.

, according to two leading experts.

In a recent invited review article, Martin Kirkpatrick, MD, of the University of Dundee (Scotland), and Finbar O’Callaghan, MD, PhD, of University College London suggested that childhood epilepsy may be easy terrain for commercial interests to break ground, and from there, build their presence.

“Children with epilepsy are at risk of being used as the ‘Trojan horse’ for the cannabis industry,” Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan wrote in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology.

They noted that some of the first publicized success stories involving cannabis oil for epilepsy coincided with the rise of the medicinal and recreational cannabis markets, which will constitute an estimated 55-billion-dollar industry by 2027.

“Pediatric neurologists, imbued with the need to practice evidence-based medicine and wary of prescribing unlicensed medicines that had inadequate safety data, suddenly found themselves at odds with an array of vested interests and, most unfortunately, with the families of patients who were keen to try anything that would alleviate the effects of their child’s seizures,” the investigators wrote.

According to the review, fundamental questions about cannabis remain unanswered, including concerns about safety with long-term use, and the medicinal value of various plant components, such as myrcene, a terpene that gives cannabis its characteristic smell.

“A widely discussed issue is whether the terpenes add any therapeutic benefit, contributing to the so-called entourage effect of ‘whole-plant’ medicines,” the investigators wrote. “The concept is that all the constituents of the plant together create ‘the sum of all the parts that leads to the magic or power of cannabis.’ Although commonly referred to, there is little or no robust evidence to support the entourage effect as a credible clinical concept.”

Clinical evidence for treatment of pediatric epilepsy is also lacking, according to Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan.

“Unfortunately, apart from the studies of pure cannabidiol (CBD) in Lennox–Gastaut and Dravet syndromes and tuberous sclerosis complex, level I evidence in the field of CBMPs and refractory epilepsy is lacking,” they wrote.

While other experts have pointed out that lower-level evidence – such as patient-reported outcomes and observational data – have previously been sufficient for drug licensing, Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan noted that such exceptions “almost always” involve conditions without any effective treatments, or drugs that are undeniably effective.

“This is not the scenario with CBMPs,” they wrote, referring to current clinical data as “low-level” evidence “suggesting … possible efficacy.”

They highlighted concerns about placebo effect with open-label epilepsy studies, citing a randomized controlled trial for Dravet syndrome, in which 27% of patients given placebo had a 50% reduction in seizure frequency.

“We need carefully designed, good-quality CBMP studies that produce results on which we can rely,” Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan concluded. “We can then work with families to choose the best treatments for children and young people with epilepsy. We owe this to them.”

A therapy of last resort

Jerzy P. Szaflarski, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, agreed that data are lacking for the use of CBMPs with patients who have epilepsy and other neurologic conditions; however, he also suggested that Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan did not provide adequate real-world clinical context.

“Medical cannabis is not used as a first-, second-, or third-line therapy,” Dr. Szaflarski said. “It’s mostly used as a last resort in the sense that patients have already failed multiple other therapies.” In that respect, patients and parents are desperate to try anything that might work. “We have medical cannabis, and our patients want to try it, and at the point when multiple therapies have failed, it’s a reasonable option.”

While Dr. Szaflarski agreed that more high-quality clinical trials are needed, he also noted the practical challenges involved in such trials, largely because of variations in cannabis plants.

“The content of the cannabis plant changes depending on the day that it’s collected and the exposure to sun and how much water it has and what’s in the soil and many other things,” Dr. Szaflarski said. “It’s hard to get a very good, standardized product, and that’s why there needs to be a good-quality product delivered by the industry, which I have not seen thus far.”

For this reason, Dr. Szaflarski steers parents and patients away from over-the-counter CBMPs and toward Epidiolex, the only FDA-approved form of CBD.

“There is evidence that Epidiolex works,” he said. “I don’t know whether the products that are sold in a local cannabis store have the same high purity as Epidiolex. I tell [parents] that we should try Epidiolex first because it’s the one that is approved. But if it doesn’t work, we can go in that [other] direction.”

For those going the commercial route, Dr. Szaflarski advised close attention to product ingredients, to ensure that CBMPs are “devoid of any impurities, pesticides, fungicides, and other products that could be potentially dangerous.”

Parents considering CBMPs for their children also need to weigh concerns about long-term neurological safety, he added, noting that, on one hand, commercial products lack data, while on the other, epilepsy itself may cause harm.

“They need to consider the potential effects [of CBMPs] on their child’s brain and development versus … the effects of seizures on the brain,” Dr. Szaflarski said.

Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan disclosed an application for a National Institute for Health Research–funded randomized controlled trial on CBMPs and joint authorship of British Paediatric Neurology Association Guidance on the use of CBMPs in children and young people with epilepsy. Dr. Szaflarski disclosed a relationship with Greenwich Biosciences and several other cannabis companies.

, according to two leading experts.

In a recent invited review article, Martin Kirkpatrick, MD, of the University of Dundee (Scotland), and Finbar O’Callaghan, MD, PhD, of University College London suggested that childhood epilepsy may be easy terrain for commercial interests to break ground, and from there, build their presence.

“Children with epilepsy are at risk of being used as the ‘Trojan horse’ for the cannabis industry,” Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan wrote in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology.

They noted that some of the first publicized success stories involving cannabis oil for epilepsy coincided with the rise of the medicinal and recreational cannabis markets, which will constitute an estimated 55-billion-dollar industry by 2027.

“Pediatric neurologists, imbued with the need to practice evidence-based medicine and wary of prescribing unlicensed medicines that had inadequate safety data, suddenly found themselves at odds with an array of vested interests and, most unfortunately, with the families of patients who were keen to try anything that would alleviate the effects of their child’s seizures,” the investigators wrote.

According to the review, fundamental questions about cannabis remain unanswered, including concerns about safety with long-term use, and the medicinal value of various plant components, such as myrcene, a terpene that gives cannabis its characteristic smell.

“A widely discussed issue is whether the terpenes add any therapeutic benefit, contributing to the so-called entourage effect of ‘whole-plant’ medicines,” the investigators wrote. “The concept is that all the constituents of the plant together create ‘the sum of all the parts that leads to the magic or power of cannabis.’ Although commonly referred to, there is little or no robust evidence to support the entourage effect as a credible clinical concept.”

Clinical evidence for treatment of pediatric epilepsy is also lacking, according to Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan.

“Unfortunately, apart from the studies of pure cannabidiol (CBD) in Lennox–Gastaut and Dravet syndromes and tuberous sclerosis complex, level I evidence in the field of CBMPs and refractory epilepsy is lacking,” they wrote.

While other experts have pointed out that lower-level evidence – such as patient-reported outcomes and observational data – have previously been sufficient for drug licensing, Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan noted that such exceptions “almost always” involve conditions without any effective treatments, or drugs that are undeniably effective.

“This is not the scenario with CBMPs,” they wrote, referring to current clinical data as “low-level” evidence “suggesting … possible efficacy.”

They highlighted concerns about placebo effect with open-label epilepsy studies, citing a randomized controlled trial for Dravet syndrome, in which 27% of patients given placebo had a 50% reduction in seizure frequency.

“We need carefully designed, good-quality CBMP studies that produce results on which we can rely,” Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan concluded. “We can then work with families to choose the best treatments for children and young people with epilepsy. We owe this to them.”

A therapy of last resort

Jerzy P. Szaflarski, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, agreed that data are lacking for the use of CBMPs with patients who have epilepsy and other neurologic conditions; however, he also suggested that Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan did not provide adequate real-world clinical context.

“Medical cannabis is not used as a first-, second-, or third-line therapy,” Dr. Szaflarski said. “It’s mostly used as a last resort in the sense that patients have already failed multiple other therapies.” In that respect, patients and parents are desperate to try anything that might work. “We have medical cannabis, and our patients want to try it, and at the point when multiple therapies have failed, it’s a reasonable option.”

While Dr. Szaflarski agreed that more high-quality clinical trials are needed, he also noted the practical challenges involved in such trials, largely because of variations in cannabis plants.

“The content of the cannabis plant changes depending on the day that it’s collected and the exposure to sun and how much water it has and what’s in the soil and many other things,” Dr. Szaflarski said. “It’s hard to get a very good, standardized product, and that’s why there needs to be a good-quality product delivered by the industry, which I have not seen thus far.”

For this reason, Dr. Szaflarski steers parents and patients away from over-the-counter CBMPs and toward Epidiolex, the only FDA-approved form of CBD.

“There is evidence that Epidiolex works,” he said. “I don’t know whether the products that are sold in a local cannabis store have the same high purity as Epidiolex. I tell [parents] that we should try Epidiolex first because it’s the one that is approved. But if it doesn’t work, we can go in that [other] direction.”

For those going the commercial route, Dr. Szaflarski advised close attention to product ingredients, to ensure that CBMPs are “devoid of any impurities, pesticides, fungicides, and other products that could be potentially dangerous.”

Parents considering CBMPs for their children also need to weigh concerns about long-term neurological safety, he added, noting that, on one hand, commercial products lack data, while on the other, epilepsy itself may cause harm.

“They need to consider the potential effects [of CBMPs] on their child’s brain and development versus … the effects of seizures on the brain,” Dr. Szaflarski said.

Dr. Kirkpatrick and Dr. O’Callaghan disclosed an application for a National Institute for Health Research–funded randomized controlled trial on CBMPs and joint authorship of British Paediatric Neurology Association Guidance on the use of CBMPs in children and young people with epilepsy. Dr. Szaflarski disclosed a relationship with Greenwich Biosciences and several other cannabis companies.

FROM DEVELOPMENTAL MEDICINE & CHILD NEUROLOGY

FDA OKs IV Briviact for seizures in kids as young as 1 month

All three brivaracetam formulations (tablets, oral solution, and IV) may now be used. The approval marks the first time that the IV formulation will be available for children, the company said in a news release.

The medication is already approved in the United States as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in adults with epilepsy.

In an open-label follow-up pediatric study, an estimated 71.4% of patients aged 1 month to 17 years with partial-onset seizures remained on brivaracetam therapy at 1 year, and 64.3% did so at 2 years, the company reported.

“We often see children with seizures hospitalized, so it’s important to have a therapy like Briviact IV that can offer rapid administration in an effective dose when needed and does not require titration,” Raman Sankar, MD, PhD, distinguished professor and chief of pediatric neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, said in the release.

“The availability of the oral dose forms also allows continuity of treatment when these young patients are transitioning from hospital to home,” he added.

Safety profile

Dr. Sankar noted that with approval now of both the IV and oral formulations for partial-onset seizures in such young children, “we have a new option that helps meet a critical need in pediatric epilepsy.”

The most common adverse reactions with brivaracetam include somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. In the pediatric clinical trials, the safety profile for pediatric patients was similar to adults.

In the adult trials, psychiatric adverse reactions, including nonpsychotic and psychotic symptoms, were reported in approximately 13% of adults taking at least 50 mg/day of brivaracetam compared with 8% taking placebo.

Psychiatric adverse reactions were also observed in open-label pediatric trials and were generally similar to those observed in adults.

Patients should be advised to report these symptoms immediately to a health care professional, the company noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All three brivaracetam formulations (tablets, oral solution, and IV) may now be used. The approval marks the first time that the IV formulation will be available for children, the company said in a news release.

The medication is already approved in the United States as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in adults with epilepsy.

In an open-label follow-up pediatric study, an estimated 71.4% of patients aged 1 month to 17 years with partial-onset seizures remained on brivaracetam therapy at 1 year, and 64.3% did so at 2 years, the company reported.

“We often see children with seizures hospitalized, so it’s important to have a therapy like Briviact IV that can offer rapid administration in an effective dose when needed and does not require titration,” Raman Sankar, MD, PhD, distinguished professor and chief of pediatric neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, said in the release.

“The availability of the oral dose forms also allows continuity of treatment when these young patients are transitioning from hospital to home,” he added.

Safety profile

Dr. Sankar noted that with approval now of both the IV and oral formulations for partial-onset seizures in such young children, “we have a new option that helps meet a critical need in pediatric epilepsy.”

The most common adverse reactions with brivaracetam include somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. In the pediatric clinical trials, the safety profile for pediatric patients was similar to adults.

In the adult trials, psychiatric adverse reactions, including nonpsychotic and psychotic symptoms, were reported in approximately 13% of adults taking at least 50 mg/day of brivaracetam compared with 8% taking placebo.

Psychiatric adverse reactions were also observed in open-label pediatric trials and were generally similar to those observed in adults.

Patients should be advised to report these symptoms immediately to a health care professional, the company noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All three brivaracetam formulations (tablets, oral solution, and IV) may now be used. The approval marks the first time that the IV formulation will be available for children, the company said in a news release.

The medication is already approved in the United States as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in adults with epilepsy.

In an open-label follow-up pediatric study, an estimated 71.4% of patients aged 1 month to 17 years with partial-onset seizures remained on brivaracetam therapy at 1 year, and 64.3% did so at 2 years, the company reported.

“We often see children with seizures hospitalized, so it’s important to have a therapy like Briviact IV that can offer rapid administration in an effective dose when needed and does not require titration,” Raman Sankar, MD, PhD, distinguished professor and chief of pediatric neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, said in the release.

“The availability of the oral dose forms also allows continuity of treatment when these young patients are transitioning from hospital to home,” he added.

Safety profile

Dr. Sankar noted that with approval now of both the IV and oral formulations for partial-onset seizures in such young children, “we have a new option that helps meet a critical need in pediatric epilepsy.”

The most common adverse reactions with brivaracetam include somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. In the pediatric clinical trials, the safety profile for pediatric patients was similar to adults.

In the adult trials, psychiatric adverse reactions, including nonpsychotic and psychotic symptoms, were reported in approximately 13% of adults taking at least 50 mg/day of brivaracetam compared with 8% taking placebo.

Psychiatric adverse reactions were also observed in open-label pediatric trials and were generally similar to those observed in adults.

Patients should be advised to report these symptoms immediately to a health care professional, the company noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘No justification’ for suicide warning on all antiseizure meds

, new research shows. “There appears to be no justification for the FDA to label every new antiseizure medication with a warning that it may increase risk of suicidality,” said study investigator Michael R. Sperling, MD, professor of neurology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

“How many patients are afraid of their medication and do not take it because of the warning – and are consequently at risk because of that? We do not know, but have anecdotal experience that this is certainly an issue,” Dr. Sperling, who is director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, added.

The study was published online August 2 in JAMA Neurology.

Blanket warning

In 2008, the FDA issued an alert stating that antiseizure medications increase suicidality. The alert was based on pooled data from placebo-controlled clinical trials that included 11 antiseizure medications – carbamazepine, felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin, tiagabine, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide.

The meta-analytic review showed that, compared with placebo, antiseizure medications nearly doubled suicide risk among patients treated for epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and other diseases. As a result of the FDA study, all antiseizure medications that have been approved since 2008 carry a warning for suicidality.

However, subsequent analyses did not show the same results, Dr. Sperling and colleagues noted.

“Pivotal” antiseizure medication epilepsy trials since 2008 have evaluated suicidality prospectively. Since 2011, trials have included the validated Columbia Suicidality Severity Rating Scale, they noted.

Meta analysis showed no increased risk

Dr. Sperling and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 17 randomized placebo-controlled epilepsy trials of five antiseizure medications approved since 2008. These antiseizure medications were eslicarbazepine, perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, and cenobamate. The trials involved 5,996 patients, including 4,000 who were treated with antiseizure medications and 1,996 who were treated with placebo.

Confining the analysis to epilepsy trials avoids potential confounders, such as possible differences in suicidality risks between different diseases, the researchers noted.

They found no evidence of increased risk for suicidal ideation (overall risk ratio, antiseizure medications vs. placebo: 0.75; 95% confidence interval: 0.35-1.60) or suicide attempt (risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI: 0.30-1.87) overall or for any individual antiseizure medication.

Suicidal ideation occurred in 12 of 4,000 patients treated with antiseizure medications (0.30%), versus 7 of 1,996 patients treated with placebo (0.35%) (P = .74). Three patients who were treated with antiseizure medications attempted suicide; no patients who were treated with placebo attempted suicide (P = .22). There were no completed suicides.

“There is no current evidence that the five antiseizure medications evaluated in this study increase suicidality in epilepsy and merit a suicidality class warning,” the investigators wrote. When prescribed for epilepsy, “evidence does not support the FDA’s labeling practice of a blanket assumption of increased suicidality,” said Dr. Sperling.

“Our findings indicate the nonspecific suicide warning for all epilepsy drugs is simply not justifiable,” he said. “The results are not surprising. Different drugs affect cells in different ways. So there’s no reason to expect that every drug would increase suicide risk for every patient,” Dr. Sperling said in a statement.

“It’s important to recognize that epilepsy has many causes – perinatal injury, stroke, tumor, head trauma, developmental malformations, genetic causes, and others – and these underlying etiologies may well contribute to the presence of depression and suicidality in this population,” he said in an interview. “Psychodynamic influences also may occur as a consequence of having seizures. This is a complicated area, and drugs are simply one piece of the puzzle,” he added.

Dr. Sperling said the FDA has accomplished “one useful thing with its warning – it highlighted that physicians and other health care providers must pay attention to their patients’ psychological state, ask questions, and treat accordingly.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Sperling has received grants from Eisai, Medtronic, Neurelis, SK Life Science, Sunovion, Takeda, Xenon, Cerevel Therapeutics, UCB Pharma, and Engage Pharma; personal fees from Neurelis, Medscape, Neurology Live, International Medical Press, UCB Pharma, Eisai, Oxford University Press, and Projects in Knowledge. He has also consulted for Medtronic outside the submitted work; payments went to Thomas Jefferson University. A complete list of authors’ disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. “There appears to be no justification for the FDA to label every new antiseizure medication with a warning that it may increase risk of suicidality,” said study investigator Michael R. Sperling, MD, professor of neurology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

“How many patients are afraid of their medication and do not take it because of the warning – and are consequently at risk because of that? We do not know, but have anecdotal experience that this is certainly an issue,” Dr. Sperling, who is director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, added.

The study was published online August 2 in JAMA Neurology.

Blanket warning

In 2008, the FDA issued an alert stating that antiseizure medications increase suicidality. The alert was based on pooled data from placebo-controlled clinical trials that included 11 antiseizure medications – carbamazepine, felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin, tiagabine, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide.

The meta-analytic review showed that, compared with placebo, antiseizure medications nearly doubled suicide risk among patients treated for epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and other diseases. As a result of the FDA study, all antiseizure medications that have been approved since 2008 carry a warning for suicidality.

However, subsequent analyses did not show the same results, Dr. Sperling and colleagues noted.

“Pivotal” antiseizure medication epilepsy trials since 2008 have evaluated suicidality prospectively. Since 2011, trials have included the validated Columbia Suicidality Severity Rating Scale, they noted.

Meta analysis showed no increased risk

Dr. Sperling and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 17 randomized placebo-controlled epilepsy trials of five antiseizure medications approved since 2008. These antiseizure medications were eslicarbazepine, perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, and cenobamate. The trials involved 5,996 patients, including 4,000 who were treated with antiseizure medications and 1,996 who were treated with placebo.

Confining the analysis to epilepsy trials avoids potential confounders, such as possible differences in suicidality risks between different diseases, the researchers noted.

They found no evidence of increased risk for suicidal ideation (overall risk ratio, antiseizure medications vs. placebo: 0.75; 95% confidence interval: 0.35-1.60) or suicide attempt (risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI: 0.30-1.87) overall or for any individual antiseizure medication.

Suicidal ideation occurred in 12 of 4,000 patients treated with antiseizure medications (0.30%), versus 7 of 1,996 patients treated with placebo (0.35%) (P = .74). Three patients who were treated with antiseizure medications attempted suicide; no patients who were treated with placebo attempted suicide (P = .22). There were no completed suicides.

“There is no current evidence that the five antiseizure medications evaluated in this study increase suicidality in epilepsy and merit a suicidality class warning,” the investigators wrote. When prescribed for epilepsy, “evidence does not support the FDA’s labeling practice of a blanket assumption of increased suicidality,” said Dr. Sperling.

“Our findings indicate the nonspecific suicide warning for all epilepsy drugs is simply not justifiable,” he said. “The results are not surprising. Different drugs affect cells in different ways. So there’s no reason to expect that every drug would increase suicide risk for every patient,” Dr. Sperling said in a statement.

“It’s important to recognize that epilepsy has many causes – perinatal injury, stroke, tumor, head trauma, developmental malformations, genetic causes, and others – and these underlying etiologies may well contribute to the presence of depression and suicidality in this population,” he said in an interview. “Psychodynamic influences also may occur as a consequence of having seizures. This is a complicated area, and drugs are simply one piece of the puzzle,” he added.

Dr. Sperling said the FDA has accomplished “one useful thing with its warning – it highlighted that physicians and other health care providers must pay attention to their patients’ psychological state, ask questions, and treat accordingly.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Sperling has received grants from Eisai, Medtronic, Neurelis, SK Life Science, Sunovion, Takeda, Xenon, Cerevel Therapeutics, UCB Pharma, and Engage Pharma; personal fees from Neurelis, Medscape, Neurology Live, International Medical Press, UCB Pharma, Eisai, Oxford University Press, and Projects in Knowledge. He has also consulted for Medtronic outside the submitted work; payments went to Thomas Jefferson University. A complete list of authors’ disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. “There appears to be no justification for the FDA to label every new antiseizure medication with a warning that it may increase risk of suicidality,” said study investigator Michael R. Sperling, MD, professor of neurology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

“How many patients are afraid of their medication and do not take it because of the warning – and are consequently at risk because of that? We do not know, but have anecdotal experience that this is certainly an issue,” Dr. Sperling, who is director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, added.

The study was published online August 2 in JAMA Neurology.

Blanket warning

In 2008, the FDA issued an alert stating that antiseizure medications increase suicidality. The alert was based on pooled data from placebo-controlled clinical trials that included 11 antiseizure medications – carbamazepine, felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin, tiagabine, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide.

The meta-analytic review showed that, compared with placebo, antiseizure medications nearly doubled suicide risk among patients treated for epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and other diseases. As a result of the FDA study, all antiseizure medications that have been approved since 2008 carry a warning for suicidality.

However, subsequent analyses did not show the same results, Dr. Sperling and colleagues noted.

“Pivotal” antiseizure medication epilepsy trials since 2008 have evaluated suicidality prospectively. Since 2011, trials have included the validated Columbia Suicidality Severity Rating Scale, they noted.

Meta analysis showed no increased risk

Dr. Sperling and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 17 randomized placebo-controlled epilepsy trials of five antiseizure medications approved since 2008. These antiseizure medications were eslicarbazepine, perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, and cenobamate. The trials involved 5,996 patients, including 4,000 who were treated with antiseizure medications and 1,996 who were treated with placebo.

Confining the analysis to epilepsy trials avoids potential confounders, such as possible differences in suicidality risks between different diseases, the researchers noted.

They found no evidence of increased risk for suicidal ideation (overall risk ratio, antiseizure medications vs. placebo: 0.75; 95% confidence interval: 0.35-1.60) or suicide attempt (risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI: 0.30-1.87) overall or for any individual antiseizure medication.

Suicidal ideation occurred in 12 of 4,000 patients treated with antiseizure medications (0.30%), versus 7 of 1,996 patients treated with placebo (0.35%) (P = .74). Three patients who were treated with antiseizure medications attempted suicide; no patients who were treated with placebo attempted suicide (P = .22). There were no completed suicides.

“There is no current evidence that the five antiseizure medications evaluated in this study increase suicidality in epilepsy and merit a suicidality class warning,” the investigators wrote. When prescribed for epilepsy, “evidence does not support the FDA’s labeling practice of a blanket assumption of increased suicidality,” said Dr. Sperling.

“Our findings indicate the nonspecific suicide warning for all epilepsy drugs is simply not justifiable,” he said. “The results are not surprising. Different drugs affect cells in different ways. So there’s no reason to expect that every drug would increase suicide risk for every patient,” Dr. Sperling said in a statement.