User login

Many advanced countries missing targets for HCV elimination

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat FIB-4 blood tests help predict cirrhosis

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal transplant shows promise in reducing alcohol craving

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

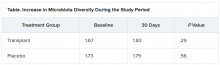

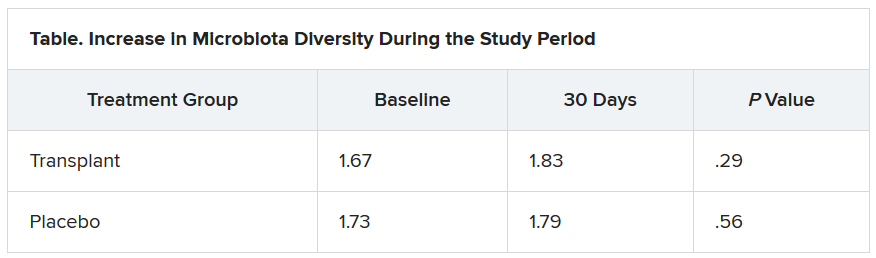

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NAFLD may predict arrhythmia recurrence post-AFib ablation

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Anti-CD8a, anti-IL-17A antibodies improved immune disruption in mice with history of NASH

Changes in a variety of T cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue play a key role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, according to the results of a murine study.

Mikhaïl A. Van Herck, of the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and associates fed 8-week old mice a high-fat, high-fructose diet for 20 weeks, and then switched the mice to standard mouse chow for 12 weeks. The high-fat, high-fructose diet induced the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), accompanied by shifts in T cells. Interleukin-17–producing (Th17 cells increased in the liver, visceral adipose tissue, and blood, while regulatory T cells decreased in visceral adipose tissue, and cytotoxic T (Tc) cells rose in visceral adipose tissue while dropping in the blood and spleen.

These are “important immune disruptions,” the researchers wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “In particular, visceral adipose tissue Tc cells are critically involved in NASH pathogenesis, linking adipose tissue inflammation to liver disease.”

After the mice were switched from the high-fat, high-fructose diet to standard mouse chow, their body weight, body fat, and plasma cholesterol significantly decreased and their glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity improved to resemble the metrics of mice fed standard mouse chow throughout the study. Mice who underwent diet reversal also had significantly decreased liver weight and levels of plasma ALT, compared with mice that remained on the high-fat, high-fructose diet. Diet reversal also improved liver histology (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores), compared with the high-fat, high-fructose diet, the researchers wrote. “Importantly, the NASH was not significantly different between diet-reversal mice and mice fed the control diet for 32 weeks.”

Genetic tests supported these findings. On multiplex RNA analysis, hepatic expression of Acta2, Col1a1, and Col1a3 reverted to normal with diet reversal, indicating a normalization of hepatic collagen. Hepatic expression of the metabolic genes Ppara, Pparg, and Fgf21 also returned to normal, while visceral adipose tissue showed a decrease in Lep and Fgf21 expression and resolution of adipocyte hypertrophy.

However, diet reversal did not reverse inflammatory changes in T-cell subsets. Administering anti-CD8a antibodies after diet reversal decreased Tc cells in all tissue types that were tested, signifying “a biochemical and histologic attenuation of the high-fat, high-fructose diet-induced NASH,” the investigators wrote. Treating the mice with antibodies targeting IL-17A did not attenuate NASH but did reduce hepatic inflammation.

The fact that “the most pronounced effect” on NASH resulted from correcting immune disruption in visceral adipose tissue underscored “the immense importance of adipose tissue inflammation in [NASH] pathogenesis,” the researchers wrote. The finding that diet reversal alone did not reverse inflammation in hepatic or visceral adipose tissue “challeng[es] our current understanding of the reversibility of NASH and other obesity-related conditions.” They called for studies of underlying mechanisms as part of “the search for a medical treatment for NASH.”

Funders included the University Research Fund, University of Antwerp, and Research Foundation Flanders. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is the chief science officer at Biocellvia, which performed some histologic analyses.

SOURCE: Van Herck MA et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.010.

The trajectory of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a public health watershed moment in gastroenterology and hepatology causing unparalleled morbidity, mortality, and societal costs. This study by Van Herck et al. advances our understanding of just how important a two-pronged environmental and biologic approach is to turn the NASH tide. The authors demonstrate that both dietary environmental exposure and biologic tissue-specific T-cell responses are involved in NASH pathogenesis, and that targeting one part of the equation is insufficient to fully mitigate disease. They observed that mice with more severe diet-induced NASH had more Th17 cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue and more cytotoxic T cells in VAT. Conversely, there were fewer VAT T-regulatory cells in mice with more liver inflammation. The major novelty of this study is that simply changing the diet to a metabolically healthier and weight-reducing diet failed to correct T-cell dysregulation. Only T cell–directed therapies improved this abnormality.

Rotonya M. Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She is a hepatologist, director of the liver metabolism and fatty liver program, and codirector of the human metabolic tissue resource. Dr. Carr receives research and salary support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

The trajectory of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a public health watershed moment in gastroenterology and hepatology causing unparalleled morbidity, mortality, and societal costs. This study by Van Herck et al. advances our understanding of just how important a two-pronged environmental and biologic approach is to turn the NASH tide. The authors demonstrate that both dietary environmental exposure and biologic tissue-specific T-cell responses are involved in NASH pathogenesis, and that targeting one part of the equation is insufficient to fully mitigate disease. They observed that mice with more severe diet-induced NASH had more Th17 cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue and more cytotoxic T cells in VAT. Conversely, there were fewer VAT T-regulatory cells in mice with more liver inflammation. The major novelty of this study is that simply changing the diet to a metabolically healthier and weight-reducing diet failed to correct T-cell dysregulation. Only T cell–directed therapies improved this abnormality.

Rotonya M. Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She is a hepatologist, director of the liver metabolism and fatty liver program, and codirector of the human metabolic tissue resource. Dr. Carr receives research and salary support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

The trajectory of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a public health watershed moment in gastroenterology and hepatology causing unparalleled morbidity, mortality, and societal costs. This study by Van Herck et al. advances our understanding of just how important a two-pronged environmental and biologic approach is to turn the NASH tide. The authors demonstrate that both dietary environmental exposure and biologic tissue-specific T-cell responses are involved in NASH pathogenesis, and that targeting one part of the equation is insufficient to fully mitigate disease. They observed that mice with more severe diet-induced NASH had more Th17 cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue and more cytotoxic T cells in VAT. Conversely, there were fewer VAT T-regulatory cells in mice with more liver inflammation. The major novelty of this study is that simply changing the diet to a metabolically healthier and weight-reducing diet failed to correct T-cell dysregulation. Only T cell–directed therapies improved this abnormality.

Rotonya M. Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She is a hepatologist, director of the liver metabolism and fatty liver program, and codirector of the human metabolic tissue resource. Dr. Carr receives research and salary support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

Changes in a variety of T cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue play a key role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, according to the results of a murine study.

Mikhaïl A. Van Herck, of the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and associates fed 8-week old mice a high-fat, high-fructose diet for 20 weeks, and then switched the mice to standard mouse chow for 12 weeks. The high-fat, high-fructose diet induced the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), accompanied by shifts in T cells. Interleukin-17–producing (Th17 cells increased in the liver, visceral adipose tissue, and blood, while regulatory T cells decreased in visceral adipose tissue, and cytotoxic T (Tc) cells rose in visceral adipose tissue while dropping in the blood and spleen.

These are “important immune disruptions,” the researchers wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “In particular, visceral adipose tissue Tc cells are critically involved in NASH pathogenesis, linking adipose tissue inflammation to liver disease.”

After the mice were switched from the high-fat, high-fructose diet to standard mouse chow, their body weight, body fat, and plasma cholesterol significantly decreased and their glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity improved to resemble the metrics of mice fed standard mouse chow throughout the study. Mice who underwent diet reversal also had significantly decreased liver weight and levels of plasma ALT, compared with mice that remained on the high-fat, high-fructose diet. Diet reversal also improved liver histology (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores), compared with the high-fat, high-fructose diet, the researchers wrote. “Importantly, the NASH was not significantly different between diet-reversal mice and mice fed the control diet for 32 weeks.”

Genetic tests supported these findings. On multiplex RNA analysis, hepatic expression of Acta2, Col1a1, and Col1a3 reverted to normal with diet reversal, indicating a normalization of hepatic collagen. Hepatic expression of the metabolic genes Ppara, Pparg, and Fgf21 also returned to normal, while visceral adipose tissue showed a decrease in Lep and Fgf21 expression and resolution of adipocyte hypertrophy.

However, diet reversal did not reverse inflammatory changes in T-cell subsets. Administering anti-CD8a antibodies after diet reversal decreased Tc cells in all tissue types that were tested, signifying “a biochemical and histologic attenuation of the high-fat, high-fructose diet-induced NASH,” the investigators wrote. Treating the mice with antibodies targeting IL-17A did not attenuate NASH but did reduce hepatic inflammation.

The fact that “the most pronounced effect” on NASH resulted from correcting immune disruption in visceral adipose tissue underscored “the immense importance of adipose tissue inflammation in [NASH] pathogenesis,” the researchers wrote. The finding that diet reversal alone did not reverse inflammation in hepatic or visceral adipose tissue “challeng[es] our current understanding of the reversibility of NASH and other obesity-related conditions.” They called for studies of underlying mechanisms as part of “the search for a medical treatment for NASH.”

Funders included the University Research Fund, University of Antwerp, and Research Foundation Flanders. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is the chief science officer at Biocellvia, which performed some histologic analyses.

SOURCE: Van Herck MA et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.010.

Changes in a variety of T cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue play a key role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, according to the results of a murine study.

Mikhaïl A. Van Herck, of the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and associates fed 8-week old mice a high-fat, high-fructose diet for 20 weeks, and then switched the mice to standard mouse chow for 12 weeks. The high-fat, high-fructose diet induced the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), accompanied by shifts in T cells. Interleukin-17–producing (Th17 cells increased in the liver, visceral adipose tissue, and blood, while regulatory T cells decreased in visceral adipose tissue, and cytotoxic T (Tc) cells rose in visceral adipose tissue while dropping in the blood and spleen.

These are “important immune disruptions,” the researchers wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “In particular, visceral adipose tissue Tc cells are critically involved in NASH pathogenesis, linking adipose tissue inflammation to liver disease.”

After the mice were switched from the high-fat, high-fructose diet to standard mouse chow, their body weight, body fat, and plasma cholesterol significantly decreased and their glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity improved to resemble the metrics of mice fed standard mouse chow throughout the study. Mice who underwent diet reversal also had significantly decreased liver weight and levels of plasma ALT, compared with mice that remained on the high-fat, high-fructose diet. Diet reversal also improved liver histology (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores), compared with the high-fat, high-fructose diet, the researchers wrote. “Importantly, the NASH was not significantly different between diet-reversal mice and mice fed the control diet for 32 weeks.”

Genetic tests supported these findings. On multiplex RNA analysis, hepatic expression of Acta2, Col1a1, and Col1a3 reverted to normal with diet reversal, indicating a normalization of hepatic collagen. Hepatic expression of the metabolic genes Ppara, Pparg, and Fgf21 also returned to normal, while visceral adipose tissue showed a decrease in Lep and Fgf21 expression and resolution of adipocyte hypertrophy.

However, diet reversal did not reverse inflammatory changes in T-cell subsets. Administering anti-CD8a antibodies after diet reversal decreased Tc cells in all tissue types that were tested, signifying “a biochemical and histologic attenuation of the high-fat, high-fructose diet-induced NASH,” the investigators wrote. Treating the mice with antibodies targeting IL-17A did not attenuate NASH but did reduce hepatic inflammation.

The fact that “the most pronounced effect” on NASH resulted from correcting immune disruption in visceral adipose tissue underscored “the immense importance of adipose tissue inflammation in [NASH] pathogenesis,” the researchers wrote. The finding that diet reversal alone did not reverse inflammation in hepatic or visceral adipose tissue “challeng[es] our current understanding of the reversibility of NASH and other obesity-related conditions.” They called for studies of underlying mechanisms as part of “the search for a medical treatment for NASH.”

Funders included the University Research Fund, University of Antwerp, and Research Foundation Flanders. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is the chief science officer at Biocellvia, which performed some histologic analyses.

SOURCE: Van Herck MA et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.010.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Studies eyes risks for poor outcomes in primary sclerosing cholangitis

In individuals with inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis, younger age at diagnosis, male sex, and Afro-Caribbean heritage were significant risk factors for liver transplantation and disease-related death, based on a 10-year prospective population-based study.

These factors should be incorporated into the design of clinical trials, models for predicting disease, and studies of prognostic biomarkers for primary sclerosing cholangitis, Palak T. Trivedi, MBBS, MRCP, of the Universty of Birmingham (England) wrote with his associates in Gastroenterology.

The researchers identified newly diagnosed cases from a national health care registry in England between 2006 and 2016 (data on outcomes were collected through mid-2019). In all, 284,560 individuals had a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, among whom 2,588 also had primary sclerosing cholangitis. The investigators tracked deaths, liver transplantation, colonic resection, cholecystectomy, and diagnoses of colorectal cancer, cholangiosarcoma, and cancers of the pancreas, gallbladder, and liver. They evaluated rates of these outcomes among individuals with both primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease (PSC-IBD) and those with IBD only.

After controlling for sex, race, socioeconomic level, comorbidities, and older age, the researchers found that both men and women with PSC-IBD had a significantly greater risk for all-cause mortality, compared with individuals with IBD alone (hazard ratio, 3.20; 95% confidence interval, 3.01-3.40; P less than .001). Strikingly, individuals who were diagnosed with PSC when they were younger than 40 years had a more than sevenfold higher rate of all-cause mortality, compared with individuals with IBD only. In contrast, the incidence rate ratio for individuals diagnosed with PSC when they were older than 60 years was less than 1.5, compared with IBD-only individuals.

Having PSC and ulcerative colitis, being younger when diagnosed with PSC, and being of Afro-Carribean heritage all correlated with higher incidence of liver transplantation or death related to PSC. Individuals with PSC-IBD who were of Afro-Caribbean heritage had an approximately twofold greater risk for liver transplantation or PSC-related death compared with Whites (adjusted HR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.14-3.70; P = .016). In contrast, women with PSC-IBD were at significantly lower risk for liver transplantation or disease-related death than were men (adjusted HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.97; P = .026).

“The onset of PSC confers heightened risks of all hepatobiliary malignancies, although annual imaging surveillance may associate with a reduced risk of cancer-related death,” the investigators found. Among patients with hepatobiliary cancer, annual imaging was associated with a twofold decrease in risk for cancer-related death (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.23-0.80; P = .037).

Colorectal cancer tended to occur at a younger age among individuals with PSC-IBD, compared with those with IBD alone (median ages at diagnosis, 59 vs. 69 years; P less than .001). Notably, individuals with PSC diagnosed under age 50 years had about a fivefold higher incidence of colorectal cancer than did those with IBD alone, while those diagnosed at older ages had only about a twofold increase. With regard to colectomy, men diagnosed with PSC at younger ages were at the greatest risk, compared with women or individuals diagnosed after age 50 years. Individuals with ulcerative colitis and PSC had a 40% greater risk for colectomy risk than did IBD-only individuals (time-dependent adjusted HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.45-1.85; P less than .001).

“Whilst all-cause mortality rates increase with age, younger patients [with PSC] show a disproportionately increased incidence of liver transplantation, PSC-related death, and colorectal cancer,” the researchers concluded. “Consideration of age at diagnosis should therefore be applied in the stratification of patients for future clinical trials, disease prediction models, and prognostic biomarker discovery.”

Dr. Trivedi disclosed support from the National Institute for Health Research Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Trivedi PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 May 19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.049.

In individuals with inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis, younger age at diagnosis, male sex, and Afro-Caribbean heritage were significant risk factors for liver transplantation and disease-related death, based on a 10-year prospective population-based study.