User login

Women Fare Better Than Men Following Total Knee, Hip Replacement

LAS VEGAS—While women may have their first total joint replacement (TJR) at an older age, they are less likely to have complications related to their surgery or require revision surgery, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). The findings contradict the theory that TJR is underutilized in female patients because they have worse outcomes than men.

Researchers reviewed patient databases from an Ontario hospital for first-time primary total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) patients between 2002 and 2009. There were 37,881 THR surgeries (53.8% female) and 59,564 TKR surgeries (60.5% female). Women who underwent THR were significantly older than males (70 years vs. 65 years); however, there was no difference in age between male and female patients undergoing TKR (median age 68 years for both). A greater proportion of female patients undergoing TJR were defined as frail (6.6% vs. 3.5% for THR; and, 6.7% vs. 4% for TKR).

Following surgery, men were:

• 15% more likely to return to the emergency department within 30 days of hospital discharge following either THR or TKR.

• 60% and 70% more likely to have an acute myocardial infarction within 3 months following THR and TKR, respectively.

• 50% more likely to require a revision arthroplasty within 2 years of TKR.

• 25% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital and 70% more likely to experience an infection or revision surgery within 2 years of TKR, compared to women.

“Despite the fact that women have a higher prevalence of advanced hip and knee arthritis, prior research indicates that North American women with arthritis are less likely to receive joint replacement than men,” said lead study author Bheeshma Ravi, MD, PhD, an orthopedic surgery resident at the University of Toronto. “One possible explanation is that women are less often offered or accept surgery because their risk of serious complications following surgery is greater than that of men.

“In this study, we found that while overall rates of serious complications were low for both groups, they were lower for women than for men for both hip and knee replacement, particularly the latter” said Dr. Ravi. “Thus, the previously documented sex difference utilization of TJR cannot be explained by differential risks of complications following surgery.”

LAS VEGAS—While women may have their first total joint replacement (TJR) at an older age, they are less likely to have complications related to their surgery or require revision surgery, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). The findings contradict the theory that TJR is underutilized in female patients because they have worse outcomes than men.

Researchers reviewed patient databases from an Ontario hospital for first-time primary total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) patients between 2002 and 2009. There were 37,881 THR surgeries (53.8% female) and 59,564 TKR surgeries (60.5% female). Women who underwent THR were significantly older than males (70 years vs. 65 years); however, there was no difference in age between male and female patients undergoing TKR (median age 68 years for both). A greater proportion of female patients undergoing TJR were defined as frail (6.6% vs. 3.5% for THR; and, 6.7% vs. 4% for TKR).

Following surgery, men were:

• 15% more likely to return to the emergency department within 30 days of hospital discharge following either THR or TKR.

• 60% and 70% more likely to have an acute myocardial infarction within 3 months following THR and TKR, respectively.

• 50% more likely to require a revision arthroplasty within 2 years of TKR.

• 25% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital and 70% more likely to experience an infection or revision surgery within 2 years of TKR, compared to women.

“Despite the fact that women have a higher prevalence of advanced hip and knee arthritis, prior research indicates that North American women with arthritis are less likely to receive joint replacement than men,” said lead study author Bheeshma Ravi, MD, PhD, an orthopedic surgery resident at the University of Toronto. “One possible explanation is that women are less often offered or accept surgery because their risk of serious complications following surgery is greater than that of men.

“In this study, we found that while overall rates of serious complications were low for both groups, they were lower for women than for men for both hip and knee replacement, particularly the latter” said Dr. Ravi. “Thus, the previously documented sex difference utilization of TJR cannot be explained by differential risks of complications following surgery.”

LAS VEGAS—While women may have their first total joint replacement (TJR) at an older age, they are less likely to have complications related to their surgery or require revision surgery, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). The findings contradict the theory that TJR is underutilized in female patients because they have worse outcomes than men.

Researchers reviewed patient databases from an Ontario hospital for first-time primary total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) patients between 2002 and 2009. There were 37,881 THR surgeries (53.8% female) and 59,564 TKR surgeries (60.5% female). Women who underwent THR were significantly older than males (70 years vs. 65 years); however, there was no difference in age between male and female patients undergoing TKR (median age 68 years for both). A greater proportion of female patients undergoing TJR were defined as frail (6.6% vs. 3.5% for THR; and, 6.7% vs. 4% for TKR).

Following surgery, men were:

• 15% more likely to return to the emergency department within 30 days of hospital discharge following either THR or TKR.

• 60% and 70% more likely to have an acute myocardial infarction within 3 months following THR and TKR, respectively.

• 50% more likely to require a revision arthroplasty within 2 years of TKR.

• 25% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital and 70% more likely to experience an infection or revision surgery within 2 years of TKR, compared to women.

“Despite the fact that women have a higher prevalence of advanced hip and knee arthritis, prior research indicates that North American women with arthritis are less likely to receive joint replacement than men,” said lead study author Bheeshma Ravi, MD, PhD, an orthopedic surgery resident at the University of Toronto. “One possible explanation is that women are less often offered or accept surgery because their risk of serious complications following surgery is greater than that of men.

“In this study, we found that while overall rates of serious complications were low for both groups, they were lower for women than for men for both hip and knee replacement, particularly the latter” said Dr. Ravi. “Thus, the previously documented sex difference utilization of TJR cannot be explained by differential risks of complications following surgery.”

Hip Replacements in Middle-Age Nearly Double From 2002-2011, Outpacing Growth in Elderly Population

LAS VEGAS—The number of total hip replacements (THRs) nearly doubled among middle-age patients between 2002 and 2011, primarily due to the expansion of the middle-age population in the United States, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Continued growth in utilization of hip replacement surgery in patients ages 45 to 64 years, an increase in revision surgeries for this population as they age, and a nearly 30% decline in the number of surgeons who perform THR could have significant implications for future health care costs, THR demand, and access, researchers said.

The researchers used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to identify primary THRs performed between 2002 and 2011 in patients ages 45 to 64 years, as well as related hospital charges. Population data and projections were obtained from the US Census Bureau and surgeon workforce estimates from the AAOS.

In 2011, 42.3% of THRs were performed in patients ages 45 to 64 years compared to 33.9% in 2002. Utilization of THR in this age group increased 89.2% from 2002 to 2011, from approximately 68,000 THRs in 2002 to 128,000 THRs in 2011. The overall population increased 21.3%. In addition, the authors found that:

• Growth of THR utilization in the 45- to 64-year-old age group grew 2.4 times faster than it did in the Medicare-aged population (age > 65 years).

• A rise in the prevalence of obesity, a known risk factor for hip osteoarthritis, among middle-age Americans was not significantly associated with increased THR utilization.

• Mean hospital charges in the THR 45- to 64-year-old age group declined 5.7% from 2002 to 2011, and declined 2.5% in the Medicare population (age > 65 years).

• Mean physician reimbursement per THR, in 2011 US dollars, declined 26.2% over the same period.

• Concurrently, the number of physicians reporting that they performed THR surgeries declined 28.2%.

“The purpose of this study was to identify potential drivers of THR utilization in the middle-age patient segment,” said lead study author Alexander S. McLawhorn, MD, MBA, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. “Our multivariable statistical model suggested that the observed growth was best explained by an expansion of the middle-age population in the US. This particular age group is projected to continue expanding, and as such the demand for THR in this active group of patients will likely continue to rise as well. Our results underscore concerns about consumption of premium-priced implants in younger patients and the future revision burden this trend implies in the face of a dwindling number of physicians who specialize in hip arthroplasty surgery.”

LAS VEGAS—The number of total hip replacements (THRs) nearly doubled among middle-age patients between 2002 and 2011, primarily due to the expansion of the middle-age population in the United States, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Continued growth in utilization of hip replacement surgery in patients ages 45 to 64 years, an increase in revision surgeries for this population as they age, and a nearly 30% decline in the number of surgeons who perform THR could have significant implications for future health care costs, THR demand, and access, researchers said.

The researchers used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to identify primary THRs performed between 2002 and 2011 in patients ages 45 to 64 years, as well as related hospital charges. Population data and projections were obtained from the US Census Bureau and surgeon workforce estimates from the AAOS.

In 2011, 42.3% of THRs were performed in patients ages 45 to 64 years compared to 33.9% in 2002. Utilization of THR in this age group increased 89.2% from 2002 to 2011, from approximately 68,000 THRs in 2002 to 128,000 THRs in 2011. The overall population increased 21.3%. In addition, the authors found that:

• Growth of THR utilization in the 45- to 64-year-old age group grew 2.4 times faster than it did in the Medicare-aged population (age > 65 years).

• A rise in the prevalence of obesity, a known risk factor for hip osteoarthritis, among middle-age Americans was not significantly associated with increased THR utilization.

• Mean hospital charges in the THR 45- to 64-year-old age group declined 5.7% from 2002 to 2011, and declined 2.5% in the Medicare population (age > 65 years).

• Mean physician reimbursement per THR, in 2011 US dollars, declined 26.2% over the same period.

• Concurrently, the number of physicians reporting that they performed THR surgeries declined 28.2%.

“The purpose of this study was to identify potential drivers of THR utilization in the middle-age patient segment,” said lead study author Alexander S. McLawhorn, MD, MBA, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. “Our multivariable statistical model suggested that the observed growth was best explained by an expansion of the middle-age population in the US. This particular age group is projected to continue expanding, and as such the demand for THR in this active group of patients will likely continue to rise as well. Our results underscore concerns about consumption of premium-priced implants in younger patients and the future revision burden this trend implies in the face of a dwindling number of physicians who specialize in hip arthroplasty surgery.”

LAS VEGAS—The number of total hip replacements (THRs) nearly doubled among middle-age patients between 2002 and 2011, primarily due to the expansion of the middle-age population in the United States, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Continued growth in utilization of hip replacement surgery in patients ages 45 to 64 years, an increase in revision surgeries for this population as they age, and a nearly 30% decline in the number of surgeons who perform THR could have significant implications for future health care costs, THR demand, and access, researchers said.

The researchers used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to identify primary THRs performed between 2002 and 2011 in patients ages 45 to 64 years, as well as related hospital charges. Population data and projections were obtained from the US Census Bureau and surgeon workforce estimates from the AAOS.

In 2011, 42.3% of THRs were performed in patients ages 45 to 64 years compared to 33.9% in 2002. Utilization of THR in this age group increased 89.2% from 2002 to 2011, from approximately 68,000 THRs in 2002 to 128,000 THRs in 2011. The overall population increased 21.3%. In addition, the authors found that:

• Growth of THR utilization in the 45- to 64-year-old age group grew 2.4 times faster than it did in the Medicare-aged population (age > 65 years).

• A rise in the prevalence of obesity, a known risk factor for hip osteoarthritis, among middle-age Americans was not significantly associated with increased THR utilization.

• Mean hospital charges in the THR 45- to 64-year-old age group declined 5.7% from 2002 to 2011, and declined 2.5% in the Medicare population (age > 65 years).

• Mean physician reimbursement per THR, in 2011 US dollars, declined 26.2% over the same period.

• Concurrently, the number of physicians reporting that they performed THR surgeries declined 28.2%.

“The purpose of this study was to identify potential drivers of THR utilization in the middle-age patient segment,” said lead study author Alexander S. McLawhorn, MD, MBA, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. “Our multivariable statistical model suggested that the observed growth was best explained by an expansion of the middle-age population in the US. This particular age group is projected to continue expanding, and as such the demand for THR in this active group of patients will likely continue to rise as well. Our results underscore concerns about consumption of premium-priced implants in younger patients and the future revision burden this trend implies in the face of a dwindling number of physicians who specialize in hip arthroplasty surgery.”

Routine Bisphosphonate Treatment for Women Older Than 65 Years Who Sustain a Wrist Fracture Could Prevent Nearly 95,000 Hip Fractures, But at a Significant Cost

LAS VEGAS—Routine bisphosphonate treatment of women older than 65 years who sustain a distal radius fracture could significantly reduce the risk for additional fractures, primarily hip fractures, but at an estimated cost of more than $2 billion annually, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

More than 50% of men and women older than 80 years meet diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis, placing them at increased risk for bone fractures, including hip fractures, which cause an estimated 300,000 unplanned hospital admissions in the United States each year. The lifetime cost of a hip fracture is estimated at $81,300, of which approximately 44% of the costs are associated with nursing facility expenses. Bisphosphonates, a drug known to increase bone mass and prevent fractures, have been associated with atypical femur fractures in a small, but significant number of patients.

Researchers reviewed existing literature and Medicare data to determine distal radius fracture incidence and age-specific hip fracture rates after distal radius fracture with and without bisphosphonate treatment. A model was then created to determine future fracture rates with and without treatment and related costs.

The model predicted 357,656 lifetime hip fractures following distal radius fracture in all females age 65 years and older in the US. If these patients received regular bisphosphonate treatment following a distal radius fracture, the number of hip fractures would drop to 262,767 over the lifetime of these patients; however, an estimated 19,464 patients would suffer an atypical femur fracture as a result of the treatment.

The cost of routine bisphosphonate treatment, including the cost for treating associated atypical femur fractures, comes to a lifetime total of $19.5 billion, or approximately $205,534 per avoided hip fracture.

“Our study suggests that routine universal utilization of bisphosphonates in elderly women after distal radius fracture would not be economically advantageous despite the cost savings associated with reduction of the hip fracture burden in that population,” said lead study author, Suneel B. Bhat, MD, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Rothman Institute in Philadelphia.

The study authors also hypothesize that the cost of bisphosphonates would need to drop to $70 per patient each year, from the current average annual wholesale cost of $1,485 per patient, to make the treatment affordable to every patient age 65 years and older following a wrist fracture. In addition, selecting patients at lower risk for atypical femur fractures for treatment may reduce the number of bisphosphonate-related fractures. Confirming patient osteoporosis and fracture risk through a DEXA Scan (dual x-ray absorptiometry) before prescribing bisphosphonates remains the most cost-effective method for treating osteoporosis and avoiding subsequent fractures.

LAS VEGAS—Routine bisphosphonate treatment of women older than 65 years who sustain a distal radius fracture could significantly reduce the risk for additional fractures, primarily hip fractures, but at an estimated cost of more than $2 billion annually, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

More than 50% of men and women older than 80 years meet diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis, placing them at increased risk for bone fractures, including hip fractures, which cause an estimated 300,000 unplanned hospital admissions in the United States each year. The lifetime cost of a hip fracture is estimated at $81,300, of which approximately 44% of the costs are associated with nursing facility expenses. Bisphosphonates, a drug known to increase bone mass and prevent fractures, have been associated with atypical femur fractures in a small, but significant number of patients.

Researchers reviewed existing literature and Medicare data to determine distal radius fracture incidence and age-specific hip fracture rates after distal radius fracture with and without bisphosphonate treatment. A model was then created to determine future fracture rates with and without treatment and related costs.

The model predicted 357,656 lifetime hip fractures following distal radius fracture in all females age 65 years and older in the US. If these patients received regular bisphosphonate treatment following a distal radius fracture, the number of hip fractures would drop to 262,767 over the lifetime of these patients; however, an estimated 19,464 patients would suffer an atypical femur fracture as a result of the treatment.

The cost of routine bisphosphonate treatment, including the cost for treating associated atypical femur fractures, comes to a lifetime total of $19.5 billion, or approximately $205,534 per avoided hip fracture.

“Our study suggests that routine universal utilization of bisphosphonates in elderly women after distal radius fracture would not be economically advantageous despite the cost savings associated with reduction of the hip fracture burden in that population,” said lead study author, Suneel B. Bhat, MD, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Rothman Institute in Philadelphia.

The study authors also hypothesize that the cost of bisphosphonates would need to drop to $70 per patient each year, from the current average annual wholesale cost of $1,485 per patient, to make the treatment affordable to every patient age 65 years and older following a wrist fracture. In addition, selecting patients at lower risk for atypical femur fractures for treatment may reduce the number of bisphosphonate-related fractures. Confirming patient osteoporosis and fracture risk through a DEXA Scan (dual x-ray absorptiometry) before prescribing bisphosphonates remains the most cost-effective method for treating osteoporosis and avoiding subsequent fractures.

LAS VEGAS—Routine bisphosphonate treatment of women older than 65 years who sustain a distal radius fracture could significantly reduce the risk for additional fractures, primarily hip fractures, but at an estimated cost of more than $2 billion annually, according to a study presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

More than 50% of men and women older than 80 years meet diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis, placing them at increased risk for bone fractures, including hip fractures, which cause an estimated 300,000 unplanned hospital admissions in the United States each year. The lifetime cost of a hip fracture is estimated at $81,300, of which approximately 44% of the costs are associated with nursing facility expenses. Bisphosphonates, a drug known to increase bone mass and prevent fractures, have been associated with atypical femur fractures in a small, but significant number of patients.

Researchers reviewed existing literature and Medicare data to determine distal radius fracture incidence and age-specific hip fracture rates after distal radius fracture with and without bisphosphonate treatment. A model was then created to determine future fracture rates with and without treatment and related costs.

The model predicted 357,656 lifetime hip fractures following distal radius fracture in all females age 65 years and older in the US. If these patients received regular bisphosphonate treatment following a distal radius fracture, the number of hip fractures would drop to 262,767 over the lifetime of these patients; however, an estimated 19,464 patients would suffer an atypical femur fracture as a result of the treatment.

The cost of routine bisphosphonate treatment, including the cost for treating associated atypical femur fractures, comes to a lifetime total of $19.5 billion, or approximately $205,534 per avoided hip fracture.

“Our study suggests that routine universal utilization of bisphosphonates in elderly women after distal radius fracture would not be economically advantageous despite the cost savings associated with reduction of the hip fracture burden in that population,” said lead study author, Suneel B. Bhat, MD, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Rothman Institute in Philadelphia.

The study authors also hypothesize that the cost of bisphosphonates would need to drop to $70 per patient each year, from the current average annual wholesale cost of $1,485 per patient, to make the treatment affordable to every patient age 65 years and older following a wrist fracture. In addition, selecting patients at lower risk for atypical femur fractures for treatment may reduce the number of bisphosphonate-related fractures. Confirming patient osteoporosis and fracture risk through a DEXA Scan (dual x-ray absorptiometry) before prescribing bisphosphonates remains the most cost-effective method for treating osteoporosis and avoiding subsequent fractures.

Nearly Half of Patients Have Delirium Before and After Hip Fracture Surgery, Diminishing Outcomes and Increasing Health Care Costs

LAS VEGAS─Nearly 50% of hip fracture patients, age 65 years and older, had delirium before, during, and after surgery, resulting in significantly longer hospital stays and higher costs for care, according to data presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Delirium was associated with 7.4 additional hospital days and approximately $8,000 more in hospital costs.

Approximately 300,000 Americans are hospitalized with hip fractures each year. The risk is particularly high in post-menopausal women who face an increased risk for osteoporosis. Delirium is common among older hip fracture patients, and multiple studies have found that patients with postoperative delirium are more likely to have complications, including infections, and less likely to return to their pre-injury level of function. Delirium patients also are more frequently placed in nursing homes following surgery and have an increased rate of mortality.

In this study, researchers at the University of Toronto sought to determine the economic implications of perioperative delirium in older orthopedic patients by reviewing hip fracture records between January 2011 and December 2012. A total of 242 hip fracture patients with a mean age of 82 years (ages 65 to 103 years) were studied. Demographic, clinical, surgical, and adverse events data were analyzed. Perioperative delirium was assessed using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).

The study found that 116 patients (48%) experienced delirium during hospital admission. The patients with delirium were significantly older (mean age 85 years), and were more likely to have a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (1 represents a completely healthy fit patient, and 5 represents a patient not expected to live beyond 24 hours without surgery). After controlling for these differences, perioperative delirium was associated with 7.4 additional hospital days and $8,282 ($8,649 in US dollars) in additional hospital costs (1.5 times the cost of patients who did not experience delirium).

There were no differences in mean time between triage or admission and surgery, length of surgery, or anesthesia type between groups. A significantly greater proportion of patients who experienced perioperative delirium required long-term and/or skilled care facility admission following their hospital stay than did those who did not experience delirium (8% versus 0%).

“Older patients are at high risk of developing delirium during hospitalization for a hip fracture, which is associated with worse outcomes,” said orthopedic surgeon and lead study author Michael G. Zywiel, MD. “Our work demonstrates that delirium also markedly increases the cost of elderly patient care while in the hospital. Given the high number of patients hospitalized every year with a hip fracture, there is a real need to develop and fund improved interventions to prevent in-hospital delirium in these patients.

“Our research suggests that reducing the rate of delirium would simultaneously increase the quality of care while decreasing costs, presenting hospitals, surgeons, and other stakeholders with promising opportunities to improve the value of hip fracture care,” said Dr. Zywiel.

The AAOS’s new clinical practice guideline, “Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly,” makes a series of recommendations to reduce delirium in older hip fracture patients. They include:

• Preoperative regional analgesia to reduce pain.

• Hip fracture surgery within 48 hours of hospital admission.

• Intensive physical therapy following hospital discharge to improve functional outcomes.

• An osteoporosis evaluation, as well as vitamin D and calcium supplements, for patients following a hip fracture.

LAS VEGAS─Nearly 50% of hip fracture patients, age 65 years and older, had delirium before, during, and after surgery, resulting in significantly longer hospital stays and higher costs for care, according to data presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Delirium was associated with 7.4 additional hospital days and approximately $8,000 more in hospital costs.

Approximately 300,000 Americans are hospitalized with hip fractures each year. The risk is particularly high in post-menopausal women who face an increased risk for osteoporosis. Delirium is common among older hip fracture patients, and multiple studies have found that patients with postoperative delirium are more likely to have complications, including infections, and less likely to return to their pre-injury level of function. Delirium patients also are more frequently placed in nursing homes following surgery and have an increased rate of mortality.

In this study, researchers at the University of Toronto sought to determine the economic implications of perioperative delirium in older orthopedic patients by reviewing hip fracture records between January 2011 and December 2012. A total of 242 hip fracture patients with a mean age of 82 years (ages 65 to 103 years) were studied. Demographic, clinical, surgical, and adverse events data were analyzed. Perioperative delirium was assessed using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).

The study found that 116 patients (48%) experienced delirium during hospital admission. The patients with delirium were significantly older (mean age 85 years), and were more likely to have a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (1 represents a completely healthy fit patient, and 5 represents a patient not expected to live beyond 24 hours without surgery). After controlling for these differences, perioperative delirium was associated with 7.4 additional hospital days and $8,282 ($8,649 in US dollars) in additional hospital costs (1.5 times the cost of patients who did not experience delirium).

There were no differences in mean time between triage or admission and surgery, length of surgery, or anesthesia type between groups. A significantly greater proportion of patients who experienced perioperative delirium required long-term and/or skilled care facility admission following their hospital stay than did those who did not experience delirium (8% versus 0%).

“Older patients are at high risk of developing delirium during hospitalization for a hip fracture, which is associated with worse outcomes,” said orthopedic surgeon and lead study author Michael G. Zywiel, MD. “Our work demonstrates that delirium also markedly increases the cost of elderly patient care while in the hospital. Given the high number of patients hospitalized every year with a hip fracture, there is a real need to develop and fund improved interventions to prevent in-hospital delirium in these patients.

“Our research suggests that reducing the rate of delirium would simultaneously increase the quality of care while decreasing costs, presenting hospitals, surgeons, and other stakeholders with promising opportunities to improve the value of hip fracture care,” said Dr. Zywiel.

The AAOS’s new clinical practice guideline, “Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly,” makes a series of recommendations to reduce delirium in older hip fracture patients. They include:

• Preoperative regional analgesia to reduce pain.

• Hip fracture surgery within 48 hours of hospital admission.

• Intensive physical therapy following hospital discharge to improve functional outcomes.

• An osteoporosis evaluation, as well as vitamin D and calcium supplements, for patients following a hip fracture.

LAS VEGAS─Nearly 50% of hip fracture patients, age 65 years and older, had delirium before, during, and after surgery, resulting in significantly longer hospital stays and higher costs for care, according to data presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Delirium was associated with 7.4 additional hospital days and approximately $8,000 more in hospital costs.

Approximately 300,000 Americans are hospitalized with hip fractures each year. The risk is particularly high in post-menopausal women who face an increased risk for osteoporosis. Delirium is common among older hip fracture patients, and multiple studies have found that patients with postoperative delirium are more likely to have complications, including infections, and less likely to return to their pre-injury level of function. Delirium patients also are more frequently placed in nursing homes following surgery and have an increased rate of mortality.

In this study, researchers at the University of Toronto sought to determine the economic implications of perioperative delirium in older orthopedic patients by reviewing hip fracture records between January 2011 and December 2012. A total of 242 hip fracture patients with a mean age of 82 years (ages 65 to 103 years) were studied. Demographic, clinical, surgical, and adverse events data were analyzed. Perioperative delirium was assessed using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).

The study found that 116 patients (48%) experienced delirium during hospital admission. The patients with delirium were significantly older (mean age 85 years), and were more likely to have a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (1 represents a completely healthy fit patient, and 5 represents a patient not expected to live beyond 24 hours without surgery). After controlling for these differences, perioperative delirium was associated with 7.4 additional hospital days and $8,282 ($8,649 in US dollars) in additional hospital costs (1.5 times the cost of patients who did not experience delirium).

There were no differences in mean time between triage or admission and surgery, length of surgery, or anesthesia type between groups. A significantly greater proportion of patients who experienced perioperative delirium required long-term and/or skilled care facility admission following their hospital stay than did those who did not experience delirium (8% versus 0%).

“Older patients are at high risk of developing delirium during hospitalization for a hip fracture, which is associated with worse outcomes,” said orthopedic surgeon and lead study author Michael G. Zywiel, MD. “Our work demonstrates that delirium also markedly increases the cost of elderly patient care while in the hospital. Given the high number of patients hospitalized every year with a hip fracture, there is a real need to develop and fund improved interventions to prevent in-hospital delirium in these patients.

“Our research suggests that reducing the rate of delirium would simultaneously increase the quality of care while decreasing costs, presenting hospitals, surgeons, and other stakeholders with promising opportunities to improve the value of hip fracture care,” said Dr. Zywiel.

The AAOS’s new clinical practice guideline, “Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly,” makes a series of recommendations to reduce delirium in older hip fracture patients. They include:

• Preoperative regional analgesia to reduce pain.

• Hip fracture surgery within 48 hours of hospital admission.

• Intensive physical therapy following hospital discharge to improve functional outcomes.

• An osteoporosis evaluation, as well as vitamin D and calcium supplements, for patients following a hip fracture.

Hip Replacement Patients May Safely Drive as Early As Two Weeks Following Surgery

LAS VEGAS—Improved surgical, pain management, and rehabilitation procedures can allow patients who undergo a total hip replacement (THR) to safely drive as early as 2 weeks following surgery, according to new research presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

Each year, more than 322,000 patients undergo hip replacement surgery in the United States. Previous studies, conducted more than a decade ago, recommended between 6 and 8 weeks of recovery before driving; however, recent advances in surgical treatment and care may have shortened this time frame. A shorter driving ban would allow patients to more quickly resume daily activities and return to work.

In this study, which appeared online November 2014 in the Journal of Arthroplasty, researchers evaluated 38 patients who underwent right THR between 2013 and 2014. Driving performance was evaluated using the Brake Reaction Test (BRT), which measures brake time reaction after a stimulus. All patients underwent preoperative assessment to establish a baseline reaction time, and then agreed to be retested at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after surgery. Patients were allowed to drive when their postoperative reaction time was equal to or less than their preoperative baseline reaction time. At each testing session patients were asked if they felt ready to drive again.

Of the 38 patients, 33 (87%) reached their baseline time within 2 weeks. The remaining patients (13%) reached their baseline at 4 weeks. Among the other findings of the study:

• There were no differences with respect to age, gender, or the use of assistance devices in terms of driving readiness.

• Of the 33 patients who tested ready to drive at 2 weeks, 24 (73%) stated that they felt ready to drive while 5 (15%) were not sure. Four patients (12%) reported that they did not feel ready to drive.

• Of the 5 patients who returned to driving at 4 weeks, 3 agreed that they were not able to drive at the 2-week mark, and the other 2 thought they were able to drive by 2 weeks.

“We found that brake reaction time returned to baseline or better in the vast majority of patients undergoing contemporary THR by 2 weeks following surgery, and all patients achieved a safe brake reaction time according to nationally recognized guidelines,” said lead study author and orthopedic surgeon Victor Hugo Hernandez, MD.

Dr. Hernandez said the “findings have allowed us to encourage patients to re-evaluate their driving ability as soon as 2 weeks after THR,” but warned that the study results “are based on our particular population, and caution should be taken in translating these results to the regular population.” In addition, patients should never drive if they are still taking narcotic pain medication.

LAS VEGAS—Improved surgical, pain management, and rehabilitation procedures can allow patients who undergo a total hip replacement (THR) to safely drive as early as 2 weeks following surgery, according to new research presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

Each year, more than 322,000 patients undergo hip replacement surgery in the United States. Previous studies, conducted more than a decade ago, recommended between 6 and 8 weeks of recovery before driving; however, recent advances in surgical treatment and care may have shortened this time frame. A shorter driving ban would allow patients to more quickly resume daily activities and return to work.

In this study, which appeared online November 2014 in the Journal of Arthroplasty, researchers evaluated 38 patients who underwent right THR between 2013 and 2014. Driving performance was evaluated using the Brake Reaction Test (BRT), which measures brake time reaction after a stimulus. All patients underwent preoperative assessment to establish a baseline reaction time, and then agreed to be retested at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after surgery. Patients were allowed to drive when their postoperative reaction time was equal to or less than their preoperative baseline reaction time. At each testing session patients were asked if they felt ready to drive again.

Of the 38 patients, 33 (87%) reached their baseline time within 2 weeks. The remaining patients (13%) reached their baseline at 4 weeks. Among the other findings of the study:

• There were no differences with respect to age, gender, or the use of assistance devices in terms of driving readiness.

• Of the 33 patients who tested ready to drive at 2 weeks, 24 (73%) stated that they felt ready to drive while 5 (15%) were not sure. Four patients (12%) reported that they did not feel ready to drive.

• Of the 5 patients who returned to driving at 4 weeks, 3 agreed that they were not able to drive at the 2-week mark, and the other 2 thought they were able to drive by 2 weeks.

“We found that brake reaction time returned to baseline or better in the vast majority of patients undergoing contemporary THR by 2 weeks following surgery, and all patients achieved a safe brake reaction time according to nationally recognized guidelines,” said lead study author and orthopedic surgeon Victor Hugo Hernandez, MD.

Dr. Hernandez said the “findings have allowed us to encourage patients to re-evaluate their driving ability as soon as 2 weeks after THR,” but warned that the study results “are based on our particular population, and caution should be taken in translating these results to the regular population.” In addition, patients should never drive if they are still taking narcotic pain medication.

LAS VEGAS—Improved surgical, pain management, and rehabilitation procedures can allow patients who undergo a total hip replacement (THR) to safely drive as early as 2 weeks following surgery, according to new research presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

Each year, more than 322,000 patients undergo hip replacement surgery in the United States. Previous studies, conducted more than a decade ago, recommended between 6 and 8 weeks of recovery before driving; however, recent advances in surgical treatment and care may have shortened this time frame. A shorter driving ban would allow patients to more quickly resume daily activities and return to work.

In this study, which appeared online November 2014 in the Journal of Arthroplasty, researchers evaluated 38 patients who underwent right THR between 2013 and 2014. Driving performance was evaluated using the Brake Reaction Test (BRT), which measures brake time reaction after a stimulus. All patients underwent preoperative assessment to establish a baseline reaction time, and then agreed to be retested at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after surgery. Patients were allowed to drive when their postoperative reaction time was equal to or less than their preoperative baseline reaction time. At each testing session patients were asked if they felt ready to drive again.

Of the 38 patients, 33 (87%) reached their baseline time within 2 weeks. The remaining patients (13%) reached their baseline at 4 weeks. Among the other findings of the study:

• There were no differences with respect to age, gender, or the use of assistance devices in terms of driving readiness.

• Of the 33 patients who tested ready to drive at 2 weeks, 24 (73%) stated that they felt ready to drive while 5 (15%) were not sure. Four patients (12%) reported that they did not feel ready to drive.

• Of the 5 patients who returned to driving at 4 weeks, 3 agreed that they were not able to drive at the 2-week mark, and the other 2 thought they were able to drive by 2 weeks.

“We found that brake reaction time returned to baseline or better in the vast majority of patients undergoing contemporary THR by 2 weeks following surgery, and all patients achieved a safe brake reaction time according to nationally recognized guidelines,” said lead study author and orthopedic surgeon Victor Hugo Hernandez, MD.

Dr. Hernandez said the “findings have allowed us to encourage patients to re-evaluate their driving ability as soon as 2 weeks after THR,” but warned that the study results “are based on our particular population, and caution should be taken in translating these results to the regular population.” In addition, patients should never drive if they are still taking narcotic pain medication.

Harrington Rod Revision After Failed Total Hip Arthroplasty Due to Missed Acetabular Metastasis

We report the case of a patient who was treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA) for osteoarthritis but was found to have a large acetabular defect caused by pulmonary metastasis. She was promptly referred to our orthopedic oncology clinic for revision because she had experienced no improvement in her symptoms. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was referred to us for evaluation of a large right supra-acetabular lesion after undergoing a right THA at another hospital 3 weeks earlier. Preoperative radiographs showed severe osteoarthritis of the right hip but there was no diagnosis of an acetabular lesion in her medical history. During the operation, the surgeon noted poor acetabulum bone quality and sent acetabular reamings for histopathologic analysis, which revealed adenocarcinoma. The arthroplasty was completed in a normal fashion, and the patient was discharged. Postoperatively, her pain did not resolve, and her functional status deteriorated from ambulating with a walker to very limited activity and weight-bearing.

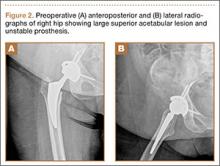

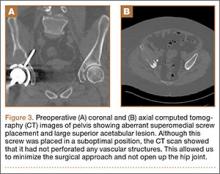

When the patient came to our clinic, we learned she underwent a lobectomy in 2011 for lung cancer resulting from her 40-pack-year history of smoking and had a strong family history of breast cancer. She also had a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, morbid obesity, and depression. We obtained plain films and a computed tomography (CT) scan that showed a 6.5×7.1×6.5-cm lytic lesion arising from the right acetabulum with cortical penetration and an extraosseous soft-tissue component. Two smaller 10-mm to 12-mm lesions were also found superior and medial to the large lesion. These radiographs and CT images are shown in Figures 1-3.

We discussed nonoperative and operative options for treatment with the patient and her family, and she elected to undergo palliative surgical curettage and fixation. Significant bone erosion of the acetabulum and a resultant lack of mechanical support for the acetabular cup were found intraoperatively. An unusual surgical approach was selected in order to minimize morbidity and avoid performing a revision acetabular component if the cup was found to be stable from the standpoint of osseointegration. We approached from the superior side of the ilium, removing the abductors in the superperiosteal fashion extending down from the supra-acetabular ilium, sparing the hip capsule. When the acetabular component was exposed and stressed under fluoroscopy, there was no evidence of loosening. We decided to reconstruct the mechanical defect without revision of the acetabular component and to leave the screw in place. After partial excision of the right supra-acetabular ilium, specimens were sent to pathology. We placed five 4.8-mm and four 4.0-mm threaded Steinmann pins intraosseously through the iliac wing to abut the acetabular cup. In this way, the Steinmann pins provided a stable roof to the cup for weight-bearing and scaffolding for methylmethacrylate cement impregnated with tobramycin. A postoperative radiograph of the patient’s pelvis is shown in Figure 4.

Immediately after her surgery, the patient was bearing weight as tolerated and participating in physical therapy 3 times a day. Two months postoperatively, she was able to walk 1 block with use of a walker, and her pain was controlled with oral pain medication. At her 1-year visit, she was walking without pain for prolonged distances. She had a mild limp but did not need ambulatory aids. She had full range of motion, was able to perform all of her desired activities, and was quite pleased with her result. One-year postoperative radiographs (Figure 5) show stable placement of her acetabular cup with her pins and cement in an unchanged position without recurrence of her destructive lesion. There was no evidence of progression of her cancer, although she had some heterotopic bone in her lateral soft tissues.

Discussion

Many cases have been reported in the literature of metastases to the pelvis and acetabulum; almost 10% of bone metastases are in the pelvis.1 Although many are seen on radiographs, pelvic metastases, especially if they involve the acetabulum, can present with hip pain, decreased joint range of motion, and reduced ambulatory function, all symptoms that are similar to osteoarthritis. While the presence of metastases indicates late-stage disease, many patients still live for years with hip symptoms before succumbing to cancer.1 Palliative treatment initially consists of protected weight-bearing, analgesics, antineoplastic medications ,and radiation. When these first-line therapies fail, palliative operative treatment can be considered, with goals to maintain stability and to preserve mobility, independence, and comfort.2 Patients should be offered this only if there is a reasonable chance that structural stability can be achieved via reconstruction and if the patient will live long enough to realize the functional improvement.3 Harrington4 described patterns of acetabular metastases and surgical treatments in his classic series of 58 patients. For class II and III lesions, he concluded it was necessary to provide additional structural support to the acetabular component of a THA, either in the form of a protrusion shell or with Steinmann pins and bone cement.4 Antiprotrusion cages combined with arthroplasty have been used with modest success for cases where implant bone integration is unlikely.5-6 Several studies since Harrington have shown that constructs with cement reinforced with Steinmann pins can provide reduced pain and improved mobility with a low failure rate for the remainder of the patient’s life.7-9

In addition, a few cases have been reported of metastases to endoprostheses, which were implanted long before the diagnosis of cancer.10 To an unsuspecting surgeon, the lytic periprosthetic metastases may look like osteolysis or pseudotumor. Fabbri and colleagues11 presented 4 cases showing how sarcoma around a joint endoprosthesis can easily be mistaken for pseudotumor. A patient considering primary or revision THA for bone loss caused by osteolysis would be given different options than if the bone loss were secondary to metastases. Revision techniques in the setting of acetabular osteolysis include acetabular liner exchanges, cementless hemispherical components and jumbo cups, structural allografts, metal augments, impaction grafting, and acetabular cages and cup-cage constructs. Rarely are “Harrington” reconstructions performed for this reason.12

This case is unusual because the diagnosis of metastatic disease was missed and THA was performed under the presumptive diagnosis of osteoarthritis. While a malignant process was recognized intraoperatively, the joint replacement was completed nonetheless, with revision surgery inevitably occurring within a few weeks. Our patient’s history of lung cancer reinforces the importance of preoperative history taking, and the missed diagnosis highlights the need for clinicians to maintain a broad differential, even in seemingly simple arthritis cases. Proper preoperative imaging, biopsies, and cultures are also paramount. Lesions that are painful, involve the whole cortex, appear soon after implementation, and are rapidly progressing should raise concern for malignancy.10 If there is concern for osteolysis, quantitative CT with 3-dimensional reconstructions can help visualize the lesions and help in planning surgery.13 Had a timely diagnosis been made, the proper reconstruction could have been planned before the index procedure, and our patient could have been spared the pain, risk, and morbidity of a second operation.

The second lesson of this case is that, as long as the cup was stable, the etiology of the hip pain was lack of mechanical support. Once corrected, the total hip functioned as planned. A minimally invasive approach that allowed for observation of the cup without exposing the entire hip saved a patient a significant amount of morbidity and led to an acceptable outcome.

1. Ho L, Ahlmann ER, Menendez LR. Modified Harrington reconstruction for advanced periacetabular metastatic disease. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(2):170-174.

2. Papagelopoulos PJ, Mavrogenis AF, Soucacos PN. Evaluation and treatment of pelvic metastases. Injury. 2007;38(4):509-520.

3. Allan DG, Bell RS, Davis A, Langer F. Complex acetabular reconstruction for metastatic tumor. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(3):301-306.

4. Harrington KD. The management of acetabular insufficiency secondary to metastatic malignant disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(4):653-64.

5. Hoell S, Dedy N, Gosheger G, Dieckmann R, Daniilidis K, Hardes J. The Burch-Schneider cage for reconstruction after metastatic destruction of the acetabulum: outcome and complications. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(3):405-410.

6. Clayer M. The survivorship of protrusio cages for metastatic disease involving the acetabulum. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(11):2980-2984.

7. Marco RA, Sheth DS, Boland PJ, Wunder JS, Siegel JA, Healey JH. Functional and oncological outcome of acetabular reconstruction for the treatment of metastatic disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(5):642-651.

8. Tillman RM, Myers GJ, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Grimer RJ. The three-pin modified ‘Harrington’ procedure for advanced metastatic destruction of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(1):84-87.

9. Walker RH. Pelvic reconstruction/total hip arthroplasty for metastatic acetabular insufficiency. Clin Orthop. 1993;294:170-175.

10. Dramis A, Desai AS, Board TN, Hekal WE, Panezai JR. Periprosthetic osteolysis due to metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):297.

11. Fabbri N, Rustemi E, Masetti C, et al. Severe osteolysis and soft tissue mass around total hip arthroplasty: description of four cases and review of the literature with respect to clinico-radiographic and pathologic differential diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(1):43-50.

12. Deirmengian GK, Zmistowski B, O’Neil JT, Hozack WJ. Management of acetabular bone loss in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(19):1842-1852.

13. Kitamura N, Leung SB, Engh CA Sr. Characteristics of pelvic osteolysis on computed tomography after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2005;441:291-297.

We report the case of a patient who was treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA) for osteoarthritis but was found to have a large acetabular defect caused by pulmonary metastasis. She was promptly referred to our orthopedic oncology clinic for revision because she had experienced no improvement in her symptoms. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was referred to us for evaluation of a large right supra-acetabular lesion after undergoing a right THA at another hospital 3 weeks earlier. Preoperative radiographs showed severe osteoarthritis of the right hip but there was no diagnosis of an acetabular lesion in her medical history. During the operation, the surgeon noted poor acetabulum bone quality and sent acetabular reamings for histopathologic analysis, which revealed adenocarcinoma. The arthroplasty was completed in a normal fashion, and the patient was discharged. Postoperatively, her pain did not resolve, and her functional status deteriorated from ambulating with a walker to very limited activity and weight-bearing.

When the patient came to our clinic, we learned she underwent a lobectomy in 2011 for lung cancer resulting from her 40-pack-year history of smoking and had a strong family history of breast cancer. She also had a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, morbid obesity, and depression. We obtained plain films and a computed tomography (CT) scan that showed a 6.5×7.1×6.5-cm lytic lesion arising from the right acetabulum with cortical penetration and an extraosseous soft-tissue component. Two smaller 10-mm to 12-mm lesions were also found superior and medial to the large lesion. These radiographs and CT images are shown in Figures 1-3.

We discussed nonoperative and operative options for treatment with the patient and her family, and she elected to undergo palliative surgical curettage and fixation. Significant bone erosion of the acetabulum and a resultant lack of mechanical support for the acetabular cup were found intraoperatively. An unusual surgical approach was selected in order to minimize morbidity and avoid performing a revision acetabular component if the cup was found to be stable from the standpoint of osseointegration. We approached from the superior side of the ilium, removing the abductors in the superperiosteal fashion extending down from the supra-acetabular ilium, sparing the hip capsule. When the acetabular component was exposed and stressed under fluoroscopy, there was no evidence of loosening. We decided to reconstruct the mechanical defect without revision of the acetabular component and to leave the screw in place. After partial excision of the right supra-acetabular ilium, specimens were sent to pathology. We placed five 4.8-mm and four 4.0-mm threaded Steinmann pins intraosseously through the iliac wing to abut the acetabular cup. In this way, the Steinmann pins provided a stable roof to the cup for weight-bearing and scaffolding for methylmethacrylate cement impregnated with tobramycin. A postoperative radiograph of the patient’s pelvis is shown in Figure 4.

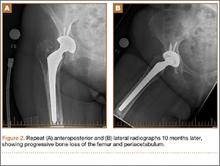

Immediately after her surgery, the patient was bearing weight as tolerated and participating in physical therapy 3 times a day. Two months postoperatively, she was able to walk 1 block with use of a walker, and her pain was controlled with oral pain medication. At her 1-year visit, she was walking without pain for prolonged distances. She had a mild limp but did not need ambulatory aids. She had full range of motion, was able to perform all of her desired activities, and was quite pleased with her result. One-year postoperative radiographs (Figure 5) show stable placement of her acetabular cup with her pins and cement in an unchanged position without recurrence of her destructive lesion. There was no evidence of progression of her cancer, although she had some heterotopic bone in her lateral soft tissues.

Discussion

Many cases have been reported in the literature of metastases to the pelvis and acetabulum; almost 10% of bone metastases are in the pelvis.1 Although many are seen on radiographs, pelvic metastases, especially if they involve the acetabulum, can present with hip pain, decreased joint range of motion, and reduced ambulatory function, all symptoms that are similar to osteoarthritis. While the presence of metastases indicates late-stage disease, many patients still live for years with hip symptoms before succumbing to cancer.1 Palliative treatment initially consists of protected weight-bearing, analgesics, antineoplastic medications ,and radiation. When these first-line therapies fail, palliative operative treatment can be considered, with goals to maintain stability and to preserve mobility, independence, and comfort.2 Patients should be offered this only if there is a reasonable chance that structural stability can be achieved via reconstruction and if the patient will live long enough to realize the functional improvement.3 Harrington4 described patterns of acetabular metastases and surgical treatments in his classic series of 58 patients. For class II and III lesions, he concluded it was necessary to provide additional structural support to the acetabular component of a THA, either in the form of a protrusion shell or with Steinmann pins and bone cement.4 Antiprotrusion cages combined with arthroplasty have been used with modest success for cases where implant bone integration is unlikely.5-6 Several studies since Harrington have shown that constructs with cement reinforced with Steinmann pins can provide reduced pain and improved mobility with a low failure rate for the remainder of the patient’s life.7-9

In addition, a few cases have been reported of metastases to endoprostheses, which were implanted long before the diagnosis of cancer.10 To an unsuspecting surgeon, the lytic periprosthetic metastases may look like osteolysis or pseudotumor. Fabbri and colleagues11 presented 4 cases showing how sarcoma around a joint endoprosthesis can easily be mistaken for pseudotumor. A patient considering primary or revision THA for bone loss caused by osteolysis would be given different options than if the bone loss were secondary to metastases. Revision techniques in the setting of acetabular osteolysis include acetabular liner exchanges, cementless hemispherical components and jumbo cups, structural allografts, metal augments, impaction grafting, and acetabular cages and cup-cage constructs. Rarely are “Harrington” reconstructions performed for this reason.12

This case is unusual because the diagnosis of metastatic disease was missed and THA was performed under the presumptive diagnosis of osteoarthritis. While a malignant process was recognized intraoperatively, the joint replacement was completed nonetheless, with revision surgery inevitably occurring within a few weeks. Our patient’s history of lung cancer reinforces the importance of preoperative history taking, and the missed diagnosis highlights the need for clinicians to maintain a broad differential, even in seemingly simple arthritis cases. Proper preoperative imaging, biopsies, and cultures are also paramount. Lesions that are painful, involve the whole cortex, appear soon after implementation, and are rapidly progressing should raise concern for malignancy.10 If there is concern for osteolysis, quantitative CT with 3-dimensional reconstructions can help visualize the lesions and help in planning surgery.13 Had a timely diagnosis been made, the proper reconstruction could have been planned before the index procedure, and our patient could have been spared the pain, risk, and morbidity of a second operation.

The second lesson of this case is that, as long as the cup was stable, the etiology of the hip pain was lack of mechanical support. Once corrected, the total hip functioned as planned. A minimally invasive approach that allowed for observation of the cup without exposing the entire hip saved a patient a significant amount of morbidity and led to an acceptable outcome.

We report the case of a patient who was treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA) for osteoarthritis but was found to have a large acetabular defect caused by pulmonary metastasis. She was promptly referred to our orthopedic oncology clinic for revision because she had experienced no improvement in her symptoms. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was referred to us for evaluation of a large right supra-acetabular lesion after undergoing a right THA at another hospital 3 weeks earlier. Preoperative radiographs showed severe osteoarthritis of the right hip but there was no diagnosis of an acetabular lesion in her medical history. During the operation, the surgeon noted poor acetabulum bone quality and sent acetabular reamings for histopathologic analysis, which revealed adenocarcinoma. The arthroplasty was completed in a normal fashion, and the patient was discharged. Postoperatively, her pain did not resolve, and her functional status deteriorated from ambulating with a walker to very limited activity and weight-bearing.

When the patient came to our clinic, we learned she underwent a lobectomy in 2011 for lung cancer resulting from her 40-pack-year history of smoking and had a strong family history of breast cancer. She also had a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, morbid obesity, and depression. We obtained plain films and a computed tomography (CT) scan that showed a 6.5×7.1×6.5-cm lytic lesion arising from the right acetabulum with cortical penetration and an extraosseous soft-tissue component. Two smaller 10-mm to 12-mm lesions were also found superior and medial to the large lesion. These radiographs and CT images are shown in Figures 1-3.

We discussed nonoperative and operative options for treatment with the patient and her family, and she elected to undergo palliative surgical curettage and fixation. Significant bone erosion of the acetabulum and a resultant lack of mechanical support for the acetabular cup were found intraoperatively. An unusual surgical approach was selected in order to minimize morbidity and avoid performing a revision acetabular component if the cup was found to be stable from the standpoint of osseointegration. We approached from the superior side of the ilium, removing the abductors in the superperiosteal fashion extending down from the supra-acetabular ilium, sparing the hip capsule. When the acetabular component was exposed and stressed under fluoroscopy, there was no evidence of loosening. We decided to reconstruct the mechanical defect without revision of the acetabular component and to leave the screw in place. After partial excision of the right supra-acetabular ilium, specimens were sent to pathology. We placed five 4.8-mm and four 4.0-mm threaded Steinmann pins intraosseously through the iliac wing to abut the acetabular cup. In this way, the Steinmann pins provided a stable roof to the cup for weight-bearing and scaffolding for methylmethacrylate cement impregnated with tobramycin. A postoperative radiograph of the patient’s pelvis is shown in Figure 4.

Immediately after her surgery, the patient was bearing weight as tolerated and participating in physical therapy 3 times a day. Two months postoperatively, she was able to walk 1 block with use of a walker, and her pain was controlled with oral pain medication. At her 1-year visit, she was walking without pain for prolonged distances. She had a mild limp but did not need ambulatory aids. She had full range of motion, was able to perform all of her desired activities, and was quite pleased with her result. One-year postoperative radiographs (Figure 5) show stable placement of her acetabular cup with her pins and cement in an unchanged position without recurrence of her destructive lesion. There was no evidence of progression of her cancer, although she had some heterotopic bone in her lateral soft tissues.

Discussion

Many cases have been reported in the literature of metastases to the pelvis and acetabulum; almost 10% of bone metastases are in the pelvis.1 Although many are seen on radiographs, pelvic metastases, especially if they involve the acetabulum, can present with hip pain, decreased joint range of motion, and reduced ambulatory function, all symptoms that are similar to osteoarthritis. While the presence of metastases indicates late-stage disease, many patients still live for years with hip symptoms before succumbing to cancer.1 Palliative treatment initially consists of protected weight-bearing, analgesics, antineoplastic medications ,and radiation. When these first-line therapies fail, palliative operative treatment can be considered, with goals to maintain stability and to preserve mobility, independence, and comfort.2 Patients should be offered this only if there is a reasonable chance that structural stability can be achieved via reconstruction and if the patient will live long enough to realize the functional improvement.3 Harrington4 described patterns of acetabular metastases and surgical treatments in his classic series of 58 patients. For class II and III lesions, he concluded it was necessary to provide additional structural support to the acetabular component of a THA, either in the form of a protrusion shell or with Steinmann pins and bone cement.4 Antiprotrusion cages combined with arthroplasty have been used with modest success for cases where implant bone integration is unlikely.5-6 Several studies since Harrington have shown that constructs with cement reinforced with Steinmann pins can provide reduced pain and improved mobility with a low failure rate for the remainder of the patient’s life.7-9

In addition, a few cases have been reported of metastases to endoprostheses, which were implanted long before the diagnosis of cancer.10 To an unsuspecting surgeon, the lytic periprosthetic metastases may look like osteolysis or pseudotumor. Fabbri and colleagues11 presented 4 cases showing how sarcoma around a joint endoprosthesis can easily be mistaken for pseudotumor. A patient considering primary or revision THA for bone loss caused by osteolysis would be given different options than if the bone loss were secondary to metastases. Revision techniques in the setting of acetabular osteolysis include acetabular liner exchanges, cementless hemispherical components and jumbo cups, structural allografts, metal augments, impaction grafting, and acetabular cages and cup-cage constructs. Rarely are “Harrington” reconstructions performed for this reason.12

This case is unusual because the diagnosis of metastatic disease was missed and THA was performed under the presumptive diagnosis of osteoarthritis. While a malignant process was recognized intraoperatively, the joint replacement was completed nonetheless, with revision surgery inevitably occurring within a few weeks. Our patient’s history of lung cancer reinforces the importance of preoperative history taking, and the missed diagnosis highlights the need for clinicians to maintain a broad differential, even in seemingly simple arthritis cases. Proper preoperative imaging, biopsies, and cultures are also paramount. Lesions that are painful, involve the whole cortex, appear soon after implementation, and are rapidly progressing should raise concern for malignancy.10 If there is concern for osteolysis, quantitative CT with 3-dimensional reconstructions can help visualize the lesions and help in planning surgery.13 Had a timely diagnosis been made, the proper reconstruction could have been planned before the index procedure, and our patient could have been spared the pain, risk, and morbidity of a second operation.

The second lesson of this case is that, as long as the cup was stable, the etiology of the hip pain was lack of mechanical support. Once corrected, the total hip functioned as planned. A minimally invasive approach that allowed for observation of the cup without exposing the entire hip saved a patient a significant amount of morbidity and led to an acceptable outcome.

1. Ho L, Ahlmann ER, Menendez LR. Modified Harrington reconstruction for advanced periacetabular metastatic disease. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(2):170-174.

2. Papagelopoulos PJ, Mavrogenis AF, Soucacos PN. Evaluation and treatment of pelvic metastases. Injury. 2007;38(4):509-520.

3. Allan DG, Bell RS, Davis A, Langer F. Complex acetabular reconstruction for metastatic tumor. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(3):301-306.

4. Harrington KD. The management of acetabular insufficiency secondary to metastatic malignant disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(4):653-64.

5. Hoell S, Dedy N, Gosheger G, Dieckmann R, Daniilidis K, Hardes J. The Burch-Schneider cage for reconstruction after metastatic destruction of the acetabulum: outcome and complications. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(3):405-410.

6. Clayer M. The survivorship of protrusio cages for metastatic disease involving the acetabulum. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(11):2980-2984.

7. Marco RA, Sheth DS, Boland PJ, Wunder JS, Siegel JA, Healey JH. Functional and oncological outcome of acetabular reconstruction for the treatment of metastatic disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(5):642-651.

8. Tillman RM, Myers GJ, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Grimer RJ. The three-pin modified ‘Harrington’ procedure for advanced metastatic destruction of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(1):84-87.

9. Walker RH. Pelvic reconstruction/total hip arthroplasty for metastatic acetabular insufficiency. Clin Orthop. 1993;294:170-175.

10. Dramis A, Desai AS, Board TN, Hekal WE, Panezai JR. Periprosthetic osteolysis due to metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):297.

11. Fabbri N, Rustemi E, Masetti C, et al. Severe osteolysis and soft tissue mass around total hip arthroplasty: description of four cases and review of the literature with respect to clinico-radiographic and pathologic differential diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(1):43-50.

12. Deirmengian GK, Zmistowski B, O’Neil JT, Hozack WJ. Management of acetabular bone loss in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(19):1842-1852.

13. Kitamura N, Leung SB, Engh CA Sr. Characteristics of pelvic osteolysis on computed tomography after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2005;441:291-297.

1. Ho L, Ahlmann ER, Menendez LR. Modified Harrington reconstruction for advanced periacetabular metastatic disease. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(2):170-174.

2. Papagelopoulos PJ, Mavrogenis AF, Soucacos PN. Evaluation and treatment of pelvic metastases. Injury. 2007;38(4):509-520.

3. Allan DG, Bell RS, Davis A, Langer F. Complex acetabular reconstruction for metastatic tumor. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(3):301-306.

4. Harrington KD. The management of acetabular insufficiency secondary to metastatic malignant disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(4):653-64.

5. Hoell S, Dedy N, Gosheger G, Dieckmann R, Daniilidis K, Hardes J. The Burch-Schneider cage for reconstruction after metastatic destruction of the acetabulum: outcome and complications. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(3):405-410.

6. Clayer M. The survivorship of protrusio cages for metastatic disease involving the acetabulum. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(11):2980-2984.

7. Marco RA, Sheth DS, Boland PJ, Wunder JS, Siegel JA, Healey JH. Functional and oncological outcome of acetabular reconstruction for the treatment of metastatic disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(5):642-651.

8. Tillman RM, Myers GJ, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Grimer RJ. The three-pin modified ‘Harrington’ procedure for advanced metastatic destruction of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(1):84-87.

9. Walker RH. Pelvic reconstruction/total hip arthroplasty for metastatic acetabular insufficiency. Clin Orthop. 1993;294:170-175.

10. Dramis A, Desai AS, Board TN, Hekal WE, Panezai JR. Periprosthetic osteolysis due to metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):297.

11. Fabbri N, Rustemi E, Masetti C, et al. Severe osteolysis and soft tissue mass around total hip arthroplasty: description of four cases and review of the literature with respect to clinico-radiographic and pathologic differential diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(1):43-50.

12. Deirmengian GK, Zmistowski B, O’Neil JT, Hozack WJ. Management of acetabular bone loss in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(19):1842-1852.

13. Kitamura N, Leung SB, Engh CA Sr. Characteristics of pelvic osteolysis on computed tomography after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2005;441:291-297.

Failure of Total Hip Arthroplasty Secondary to Infection Caused by Brucella abortus and the Risk of Transmission to Operative Staff

Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease transmitted to humans through contact with animal hosts or animal products. Infection of total knee or hip arthroplasty by Brucella species is a rare complication with only 18 cases reported in the English literature.1-12 We describe a case of an infected total hip replacement, its treatment, and 2-year follow-up and review the available literature. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 67-year-old Spanish-speaking woman, a native of Mexico, presented with a painful right total hip arthroplasty (THA) 2 years after implantation in Chihuahua, Mexico. The patient reported 1 year of increasing thigh pain with recent onset of start-up pain, and also mild groin pain. The patient reported an uneventful postoperative course without wound drainage and denied any history of fevers, chills, or night sweats after the procedure. Preoperative notes and radiographs were unavailable for review. Radiographic evaluation showed a hybrid construct with a well-fixed–appearing, uncemented acetabular component but a failed cemented femoral stem (Figures 1A, 1B). Although we discussed revision surgery, the patient elected not to proceed with surgery or to undergo evaluation to rule out infection. Nine months later, she returned with worsening pain and requested revision surgery; radiographs showed progressive bone loss around the cement mantle (Figures 2A, 2B).

Hematologic evaluation showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 54 mm/h (normal, 0-27 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 0.24 mg/L (normal, <0.8). An aspiration of the hip with fluoroscopic guidance produced a small sample (0.2 mL) of yellow synovial fluid. There was not enough fluid for cell count, but fluid culture was negative.

The patient was taken to the operating room for revision THA. Because of concern about progressive bone loss and elevated infectious indices, the administration of antibiotics was delayed until we obtained sufficient deep-tissue specimens. Before opening the capsule, we introduced a syringe into the joint and aspirated 10 mL of cloudy yellow synovial fluid that was sent for cell count. Additional findings at surgery included a grossly loose stem with a fragmented cement mantle surrounded by poor bone stock with anterior cortical bone loss and a loose acetabular component with pockets of cavitary bone loss. Frozen section showed up to 5 nucleated cells per high power field, and the cell count showed 1480 nucleated cells/µL (50% polymorphonuclear cells). The equivocal intraoperative findings (cell count and frozen section) and the loose femoral and acetabular components with significant bone loss were sufficiently concerning that we removed the components and placed a cement spacer rather than proceed with revision arthroplasty (Figures 3A, 3B). The surgeon, first assistant, and scrub technician wore body exhaust suits. We performed irrigation of the wound bed with pulse lavage.