User login

Highly anticipated HIV vaccine fails in large trial

officials announced Wednesday.

The vaccine had been in development since 2019 and was given to 3,900 study participants through October 2022, but data shows it does not protect against HIV compared with a placebo, according to developer Janssen Pharmaceutical.

Experts estimate the failure means there won’t be another potential vaccine on the horizon for 3 to 5 years, the New York Times reported.

“It’s obviously disappointing,” Anthony Fauci, MD, former head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC, noting that other areas of HIV treatment research are promising. “I don’t think that people should give up on the field of the HIV vaccine.”

No safety issues had been identified with the vaccine during the trial, which studied the experimental treatment in men who have sex with men or with transgender people.

There is no cure for HIV, but disease progression can be managed with existing treatments. HIV attacks the body’s immune system and destroys white blood cells, increasing the risk of other infections. More than 1.5 million people worldwide were infected with HIV in 2021 and 38.4 million people are living with the virus, according to UNAIDS.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

officials announced Wednesday.

The vaccine had been in development since 2019 and was given to 3,900 study participants through October 2022, but data shows it does not protect against HIV compared with a placebo, according to developer Janssen Pharmaceutical.

Experts estimate the failure means there won’t be another potential vaccine on the horizon for 3 to 5 years, the New York Times reported.

“It’s obviously disappointing,” Anthony Fauci, MD, former head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC, noting that other areas of HIV treatment research are promising. “I don’t think that people should give up on the field of the HIV vaccine.”

No safety issues had been identified with the vaccine during the trial, which studied the experimental treatment in men who have sex with men or with transgender people.

There is no cure for HIV, but disease progression can be managed with existing treatments. HIV attacks the body’s immune system and destroys white blood cells, increasing the risk of other infections. More than 1.5 million people worldwide were infected with HIV in 2021 and 38.4 million people are living with the virus, according to UNAIDS.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

officials announced Wednesday.

The vaccine had been in development since 2019 and was given to 3,900 study participants through October 2022, but data shows it does not protect against HIV compared with a placebo, according to developer Janssen Pharmaceutical.

Experts estimate the failure means there won’t be another potential vaccine on the horizon for 3 to 5 years, the New York Times reported.

“It’s obviously disappointing,” Anthony Fauci, MD, former head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC, noting that other areas of HIV treatment research are promising. “I don’t think that people should give up on the field of the HIV vaccine.”

No safety issues had been identified with the vaccine during the trial, which studied the experimental treatment in men who have sex with men or with transgender people.

There is no cure for HIV, but disease progression can be managed with existing treatments. HIV attacks the body’s immune system and destroys white blood cells, increasing the risk of other infections. More than 1.5 million people worldwide were infected with HIV in 2021 and 38.4 million people are living with the virus, according to UNAIDS.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Kaposi’s sarcoma: Antiretroviral-related improvements in survival measured

than their uninfected counterparts, based on the first such analysis of the American College of Surgeons’ National Cancer Database.

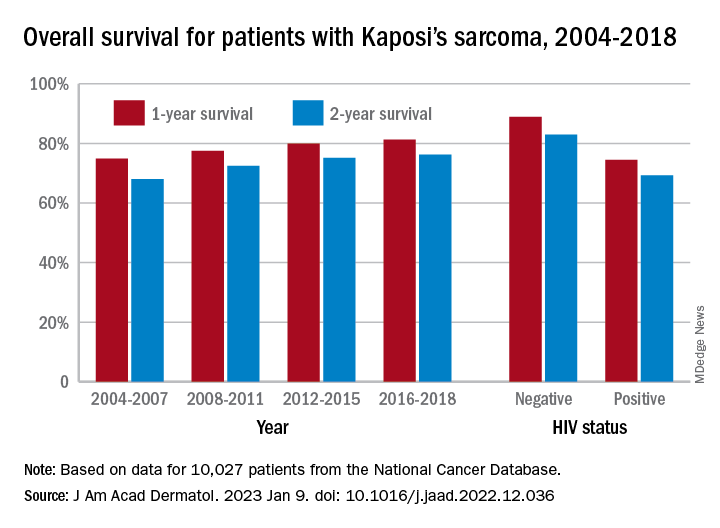

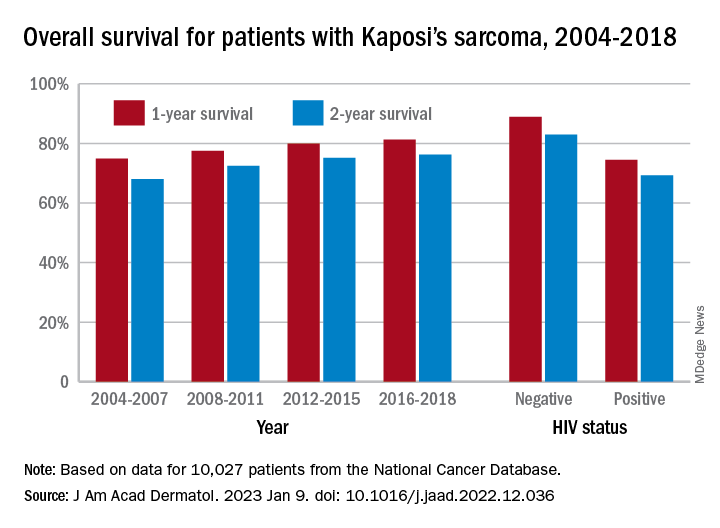

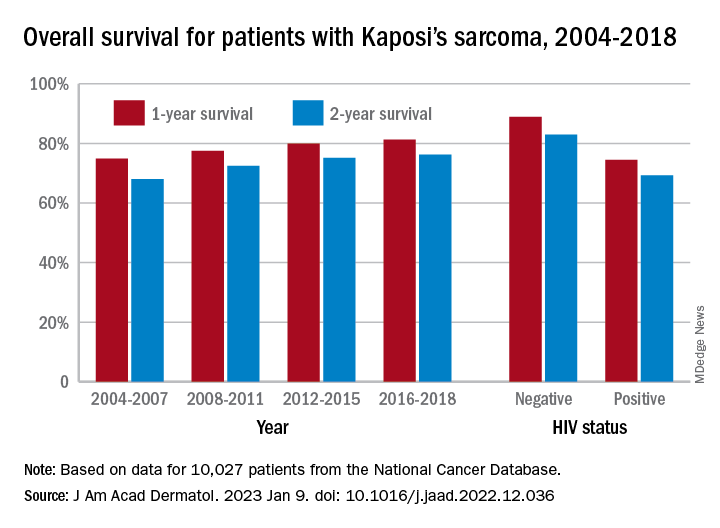

One-year overall survival for all patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), 74.9% in 2004-2007, rose by 6.4 percentage points to 81.3% in 2016-2018, with the use of ART for HIV starting in 2008. Two-year survival was up by an even larger 8.3 percentage points: 68.0% to 76.3%, said Amar D. Desai of New Jersey Medical School, Newark, and Shari R. Lipner, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Since HIV-infected patients represented a much lower 46.7% of the Kaposi’s population in 2016-2018 than in 2004-2007 (70.5%), “better outcomes for all KS patients likely reflects advancements in ART, preventing many HIV+ patients from progressing to AIDS, changes in clinical practice with earlier treatment start, and more off-label treatments,” they wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Overall survival rates for the 10,027 patients with KS with data available in the National Cancer Database were 77.9% at 1 year and 72.4% at 2 years. HIV status had a significant (P < .0074) effect over the entire study period: One-year survival rates were 88.9% for HIV-negative and 74.5% for HIV-positive patients, and 2-year rates were 83.0% (HIV-negative) and 69.3% (HIV-positive), the investigators reported in what they called “the largest analysis since the advent of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in 2008.”

The improvement in overall survival, along with the continued differences in survival between HIV infected and noninfected patients, indicate that “dermatologists, as part of a multidisciplinary team including oncologists and infectious disease physicians, can play significant roles in early KS diagnosis,” Mr. Desai and Dr. Lipner said.

Mr. Desai had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Lipner has served as a consultant for Ortho-Dermatologics, Hoth Therapeutics, and BelleTorus Corporation.

than their uninfected counterparts, based on the first such analysis of the American College of Surgeons’ National Cancer Database.

One-year overall survival for all patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), 74.9% in 2004-2007, rose by 6.4 percentage points to 81.3% in 2016-2018, with the use of ART for HIV starting in 2008. Two-year survival was up by an even larger 8.3 percentage points: 68.0% to 76.3%, said Amar D. Desai of New Jersey Medical School, Newark, and Shari R. Lipner, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Since HIV-infected patients represented a much lower 46.7% of the Kaposi’s population in 2016-2018 than in 2004-2007 (70.5%), “better outcomes for all KS patients likely reflects advancements in ART, preventing many HIV+ patients from progressing to AIDS, changes in clinical practice with earlier treatment start, and more off-label treatments,” they wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Overall survival rates for the 10,027 patients with KS with data available in the National Cancer Database were 77.9% at 1 year and 72.4% at 2 years. HIV status had a significant (P < .0074) effect over the entire study period: One-year survival rates were 88.9% for HIV-negative and 74.5% for HIV-positive patients, and 2-year rates were 83.0% (HIV-negative) and 69.3% (HIV-positive), the investigators reported in what they called “the largest analysis since the advent of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in 2008.”

The improvement in overall survival, along with the continued differences in survival between HIV infected and noninfected patients, indicate that “dermatologists, as part of a multidisciplinary team including oncologists and infectious disease physicians, can play significant roles in early KS diagnosis,” Mr. Desai and Dr. Lipner said.

Mr. Desai had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Lipner has served as a consultant for Ortho-Dermatologics, Hoth Therapeutics, and BelleTorus Corporation.

than their uninfected counterparts, based on the first such analysis of the American College of Surgeons’ National Cancer Database.

One-year overall survival for all patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), 74.9% in 2004-2007, rose by 6.4 percentage points to 81.3% in 2016-2018, with the use of ART for HIV starting in 2008. Two-year survival was up by an even larger 8.3 percentage points: 68.0% to 76.3%, said Amar D. Desai of New Jersey Medical School, Newark, and Shari R. Lipner, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Since HIV-infected patients represented a much lower 46.7% of the Kaposi’s population in 2016-2018 than in 2004-2007 (70.5%), “better outcomes for all KS patients likely reflects advancements in ART, preventing many HIV+ patients from progressing to AIDS, changes in clinical practice with earlier treatment start, and more off-label treatments,” they wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Overall survival rates for the 10,027 patients with KS with data available in the National Cancer Database were 77.9% at 1 year and 72.4% at 2 years. HIV status had a significant (P < .0074) effect over the entire study period: One-year survival rates were 88.9% for HIV-negative and 74.5% for HIV-positive patients, and 2-year rates were 83.0% (HIV-negative) and 69.3% (HIV-positive), the investigators reported in what they called “the largest analysis since the advent of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in 2008.”

The improvement in overall survival, along with the continued differences in survival between HIV infected and noninfected patients, indicate that “dermatologists, as part of a multidisciplinary team including oncologists and infectious disease physicians, can play significant roles in early KS diagnosis,” Mr. Desai and Dr. Lipner said.

Mr. Desai had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Lipner has served as a consultant for Ortho-Dermatologics, Hoth Therapeutics, and BelleTorus Corporation.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

FDA approves first-in-class drug for HIV

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the medication lenacapavir (Sunlenca) for adults living with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. .

“Following today’s decision from the FDA, lenacapavir helps to fill a critical unmet need for people with complex prior treatment histories and offers physicians a long-awaited twice-yearly option for these patients who otherwise have limited therapy choices,” said site principal investigator Sorana Segal-Maurer, MD, a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, in a statement.

HIV drug regimens generally consist of two or three HIV medicines combined in a daily pill. In 2021, the FDA approved the first injectable complete drug regimen for HIV-1, Cabenuva, which can be administered monthly or every other month. Lenacapavir is administered only twice annually, but it is also combined with other antiretrovirals. The injections and oral tablets of lenacapavir are estimated to cost $42,250 in the first year of treatment and then $39,000 annually in the subsequent years, Reuters reported.

Lenacapavir is the first of a new class of drug called capsid inhibitors to be FDA-approved for treating HIV-1. The drug blocks the HIV-1 virus’s protein shell and interferes with essential steps of the virus’s evolution. The approval, announced today, was based on a multicenter clinical trial of 72 patients with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. After a year of the medication, 30 (83%) of the 36 patients randomly assigned to take lenacapavir, in combination with other HIV medications, had undetectable viral loads.

“Today’s approval ushers in a new class of antiretroviral drugs that may help patients with HIV who have run out of treatment options,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the division of antivirals in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “The availability of new classes of antiretroviral medications may possibly help these patients live longer, healthier lives.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the medication lenacapavir (Sunlenca) for adults living with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. .

“Following today’s decision from the FDA, lenacapavir helps to fill a critical unmet need for people with complex prior treatment histories and offers physicians a long-awaited twice-yearly option for these patients who otherwise have limited therapy choices,” said site principal investigator Sorana Segal-Maurer, MD, a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, in a statement.

HIV drug regimens generally consist of two or three HIV medicines combined in a daily pill. In 2021, the FDA approved the first injectable complete drug regimen for HIV-1, Cabenuva, which can be administered monthly or every other month. Lenacapavir is administered only twice annually, but it is also combined with other antiretrovirals. The injections and oral tablets of lenacapavir are estimated to cost $42,250 in the first year of treatment and then $39,000 annually in the subsequent years, Reuters reported.

Lenacapavir is the first of a new class of drug called capsid inhibitors to be FDA-approved for treating HIV-1. The drug blocks the HIV-1 virus’s protein shell and interferes with essential steps of the virus’s evolution. The approval, announced today, was based on a multicenter clinical trial of 72 patients with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. After a year of the medication, 30 (83%) of the 36 patients randomly assigned to take lenacapavir, in combination with other HIV medications, had undetectable viral loads.

“Today’s approval ushers in a new class of antiretroviral drugs that may help patients with HIV who have run out of treatment options,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the division of antivirals in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “The availability of new classes of antiretroviral medications may possibly help these patients live longer, healthier lives.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the medication lenacapavir (Sunlenca) for adults living with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. .

“Following today’s decision from the FDA, lenacapavir helps to fill a critical unmet need for people with complex prior treatment histories and offers physicians a long-awaited twice-yearly option for these patients who otherwise have limited therapy choices,” said site principal investigator Sorana Segal-Maurer, MD, a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, in a statement.

HIV drug regimens generally consist of two or three HIV medicines combined in a daily pill. In 2021, the FDA approved the first injectable complete drug regimen for HIV-1, Cabenuva, which can be administered monthly or every other month. Lenacapavir is administered only twice annually, but it is also combined with other antiretrovirals. The injections and oral tablets of lenacapavir are estimated to cost $42,250 in the first year of treatment and then $39,000 annually in the subsequent years, Reuters reported.

Lenacapavir is the first of a new class of drug called capsid inhibitors to be FDA-approved for treating HIV-1. The drug blocks the HIV-1 virus’s protein shell and interferes with essential steps of the virus’s evolution. The approval, announced today, was based on a multicenter clinical trial of 72 patients with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. After a year of the medication, 30 (83%) of the 36 patients randomly assigned to take lenacapavir, in combination with other HIV medications, had undetectable viral loads.

“Today’s approval ushers in a new class of antiretroviral drugs that may help patients with HIV who have run out of treatment options,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the division of antivirals in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “The availability of new classes of antiretroviral medications may possibly help these patients live longer, healthier lives.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Systematic review supports preferred drugs for HIV in youths

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL AIDS SOCIETY

HIV vaccine trial makes pivotal leap toward making ‘super antibodies’

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE

CAB-LA’s full potential for HIV prevention hits snags

, say authors of a new review article.

CAB-LA “represents the most important breakthrough in HIV prevention in recent years,” write Geoffroy Liegeon, MD, and Jade Ghosn, MD, PhD, with Université Paris Cité, in this month’s HIV Medicine.

It has been found to be safe, and more effective in phase 3 trials than oral PrEP, and is well-accepted in men who have sex with men, and transgender and cisgender women.

Reductions in stigma

Surveys show patients at high risk for HIV – especially those who see PrEP as burdensome – are highly interested in long-acting injectable drugs. Reduced stigma with the injections also appears to steer the choice toward a long-acting agent and may attract more people to HIV prevention programs.

The first two injections are given 4 weeks apart, followed by an injection every 8 weeks.

Models designed to increase uptake, adherence, and persistence when on and after discontinuing CAB-LA will be important for wider rollout, as will better patient education and demonstrated efficacy and safety in populations not included in clinical trials, Dr. Liegeon and Dr. Ghosn note.

Still, they point out that its broader integration into clinical routine is held back by factors including breakthrough infections despite timely injections, complexity of follow-up, logistical considerations, and its cost-effectiveness compared with oral PrEP.

A hefty price tag

“[T]he cost effectiveness compared with TDF-FTC [tenofovir/emtricitabine] generics may not support its use at the current price in many settings,” the authors write.

For low- and middle-income countries, the TDF/FTC price is about $55, according to the World Health Organization’s Global Price Reporting, while the current price of CAB-LA in the United States is about $22,000, according to Dr. Ghosn. He said in an interview that because the cost of generics can reach $400-$500 per year in the United States, depending on the pharmaceutical companies, the price for CAB-LA is almost 60 times higher than TDF/FTC in the Untied States.

The biggest hope for the price reduction, at least in lower-income countries, he said, is a new licensing agreement.

ViiV Healthcare signed a new voluntary licensing agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool in July to help access in low-income, lower-middle-income, and sub-Saharan African countries, he explained.

The authors summarize: “[E]stablishing the effectiveness of CAB-LA does not guarantee its uptake into clinical routine.”

Because of the combined issues, the WHO recommended CAB-LA as an additional prevention choice for PrEP in its recent guidelines, pending further studies.

Barriers frustrate providers

Lauren Fontana, DO, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and infectious disease physician at M Health Fairview, said in an interview that “as a health care provider, cost and insurance barriers can be frustrating, especially when CAB-LA is identified as the best option for a patient.”

Lack of nonphysician-led initiatives, such as nurse- or pharmacy-led services for CAB-LA, may limit availability to marginalized and at-risk populations, she said.

“If a clinic can acquire CAB-LA, clinic protocols need to be developed and considerations of missed visits and doses must be thought about when implementing a program,” Dr. Fontana said.

Clinics need resources to engage with patients to promote retention in the program with case management and pharmacy support, she added.

“Simplification processes need to be developed to make CAB-LA an option for more clinics and patients,” she continued. “We are still learning about the incidence of breakthrough HIV infections, patterns of HIV seroconversion, and how to optimize testing so that HIV infections are detected early.”

Dr. Liegeon, Dr. Ghosn, and Dr. Fontana report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, say authors of a new review article.

CAB-LA “represents the most important breakthrough in HIV prevention in recent years,” write Geoffroy Liegeon, MD, and Jade Ghosn, MD, PhD, with Université Paris Cité, in this month’s HIV Medicine.

It has been found to be safe, and more effective in phase 3 trials than oral PrEP, and is well-accepted in men who have sex with men, and transgender and cisgender women.

Reductions in stigma

Surveys show patients at high risk for HIV – especially those who see PrEP as burdensome – are highly interested in long-acting injectable drugs. Reduced stigma with the injections also appears to steer the choice toward a long-acting agent and may attract more people to HIV prevention programs.

The first two injections are given 4 weeks apart, followed by an injection every 8 weeks.

Models designed to increase uptake, adherence, and persistence when on and after discontinuing CAB-LA will be important for wider rollout, as will better patient education and demonstrated efficacy and safety in populations not included in clinical trials, Dr. Liegeon and Dr. Ghosn note.

Still, they point out that its broader integration into clinical routine is held back by factors including breakthrough infections despite timely injections, complexity of follow-up, logistical considerations, and its cost-effectiveness compared with oral PrEP.

A hefty price tag

“[T]he cost effectiveness compared with TDF-FTC [tenofovir/emtricitabine] generics may not support its use at the current price in many settings,” the authors write.

For low- and middle-income countries, the TDF/FTC price is about $55, according to the World Health Organization’s Global Price Reporting, while the current price of CAB-LA in the United States is about $22,000, according to Dr. Ghosn. He said in an interview that because the cost of generics can reach $400-$500 per year in the United States, depending on the pharmaceutical companies, the price for CAB-LA is almost 60 times higher than TDF/FTC in the Untied States.

The biggest hope for the price reduction, at least in lower-income countries, he said, is a new licensing agreement.

ViiV Healthcare signed a new voluntary licensing agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool in July to help access in low-income, lower-middle-income, and sub-Saharan African countries, he explained.

The authors summarize: “[E]stablishing the effectiveness of CAB-LA does not guarantee its uptake into clinical routine.”

Because of the combined issues, the WHO recommended CAB-LA as an additional prevention choice for PrEP in its recent guidelines, pending further studies.

Barriers frustrate providers

Lauren Fontana, DO, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and infectious disease physician at M Health Fairview, said in an interview that “as a health care provider, cost and insurance barriers can be frustrating, especially when CAB-LA is identified as the best option for a patient.”

Lack of nonphysician-led initiatives, such as nurse- or pharmacy-led services for CAB-LA, may limit availability to marginalized and at-risk populations, she said.

“If a clinic can acquire CAB-LA, clinic protocols need to be developed and considerations of missed visits and doses must be thought about when implementing a program,” Dr. Fontana said.

Clinics need resources to engage with patients to promote retention in the program with case management and pharmacy support, she added.

“Simplification processes need to be developed to make CAB-LA an option for more clinics and patients,” she continued. “We are still learning about the incidence of breakthrough HIV infections, patterns of HIV seroconversion, and how to optimize testing so that HIV infections are detected early.”

Dr. Liegeon, Dr. Ghosn, and Dr. Fontana report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, say authors of a new review article.

CAB-LA “represents the most important breakthrough in HIV prevention in recent years,” write Geoffroy Liegeon, MD, and Jade Ghosn, MD, PhD, with Université Paris Cité, in this month’s HIV Medicine.

It has been found to be safe, and more effective in phase 3 trials than oral PrEP, and is well-accepted in men who have sex with men, and transgender and cisgender women.

Reductions in stigma

Surveys show patients at high risk for HIV – especially those who see PrEP as burdensome – are highly interested in long-acting injectable drugs. Reduced stigma with the injections also appears to steer the choice toward a long-acting agent and may attract more people to HIV prevention programs.

The first two injections are given 4 weeks apart, followed by an injection every 8 weeks.

Models designed to increase uptake, adherence, and persistence when on and after discontinuing CAB-LA will be important for wider rollout, as will better patient education and demonstrated efficacy and safety in populations not included in clinical trials, Dr. Liegeon and Dr. Ghosn note.

Still, they point out that its broader integration into clinical routine is held back by factors including breakthrough infections despite timely injections, complexity of follow-up, logistical considerations, and its cost-effectiveness compared with oral PrEP.

A hefty price tag

“[T]he cost effectiveness compared with TDF-FTC [tenofovir/emtricitabine] generics may not support its use at the current price in many settings,” the authors write.

For low- and middle-income countries, the TDF/FTC price is about $55, according to the World Health Organization’s Global Price Reporting, while the current price of CAB-LA in the United States is about $22,000, according to Dr. Ghosn. He said in an interview that because the cost of generics can reach $400-$500 per year in the United States, depending on the pharmaceutical companies, the price for CAB-LA is almost 60 times higher than TDF/FTC in the Untied States.

The biggest hope for the price reduction, at least in lower-income countries, he said, is a new licensing agreement.

ViiV Healthcare signed a new voluntary licensing agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool in July to help access in low-income, lower-middle-income, and sub-Saharan African countries, he explained.

The authors summarize: “[E]stablishing the effectiveness of CAB-LA does not guarantee its uptake into clinical routine.”

Because of the combined issues, the WHO recommended CAB-LA as an additional prevention choice for PrEP in its recent guidelines, pending further studies.

Barriers frustrate providers

Lauren Fontana, DO, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and infectious disease physician at M Health Fairview, said in an interview that “as a health care provider, cost and insurance barriers can be frustrating, especially when CAB-LA is identified as the best option for a patient.”

Lack of nonphysician-led initiatives, such as nurse- or pharmacy-led services for CAB-LA, may limit availability to marginalized and at-risk populations, she said.

“If a clinic can acquire CAB-LA, clinic protocols need to be developed and considerations of missed visits and doses must be thought about when implementing a program,” Dr. Fontana said.

Clinics need resources to engage with patients to promote retention in the program with case management and pharmacy support, she added.

“Simplification processes need to be developed to make CAB-LA an option for more clinics and patients,” she continued. “We are still learning about the incidence of breakthrough HIV infections, patterns of HIV seroconversion, and how to optimize testing so that HIV infections are detected early.”

Dr. Liegeon, Dr. Ghosn, and Dr. Fontana report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HIV MEDICINE

Pregnancy outcomes on long-acting antiretroviral

In a cautiously optimistic report,

Among 10 live births, there was one birth defect (congenital ptosis, or droopy eyelid), which was not attributed to the trial drugs. There were no instances of perinatal HIV transmission at delivery or during the 1-year follow-up.

“Long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine is the first and only complete injectable regimen potentially available for pregnant women,” first author Parul Patel, PharmD, global medical affairs director for cabotegravir at ViiV Healthcare, said in an interview. The regimen was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in January 2021 for injections every 4 weeks and in February 2022 for injections every 8 weeks.

“Importantly, it can be dosed monthly or every 2 months,” Patel said. “This could be advantageous for women who are experiencing constant change during pregnancy. This could be a consideration for women who might have problems tolerating oral pills during pregnancy or might have problems with emesis.”

The study was published in HIV Medicine.

“We are really pursuing the development of the long-acting version of cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine,” Dr. Patel said. “It’s an industry standard during initial development that you start very conservatively and not allow a woman who is pregnant to continue dosing of a drug while still evaluating its overall safety profile. We really want to understand the use of this agent in nonpregnant adults before exposing pregnant women to active treatment.”

Pregnancies in trials excluding pregnant women

In the paper, Dr. Patel and her coauthors noted the limited data on pregnant women exposed to CAB + RPV. They analyzed pregnancies in four phase 2b/3/3b clinical trials sponsored by ViiV Healthcare and a compassionate use program. All clinical trial participants first received oral CAB + RPV daily for 4 weeks to assess individual tolerance before the experimental long-acting injection of CAB + RPV every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks.

Women participants were required to use highly effective contraception during the trials and for at least 52 weeks after the last injection. Urine pregnancy tests were given at baseline, before each injection, and when pregnancy was suspected. If a pregnancy was detected, CAB + RPV (oral or long-acting injections) was discontinued and the woman switched to an alternative oral antiretroviral, unless she and her physician decided to continue with injections in the compassionate use program.

Pregnancy outcomes

Among 25 reported pregnancies in 22 women during the trial, there were 10 live births. Nine of the mothers who delivered their babies at term had switched to an alternative antiretroviral regimen and maintained virologic suppression throughout pregnancy and post partum, or the last available viral load assessment.

The 10th participant remained on long-acting CAB + RPV during her pregnancy and had a live birth with congenital ptosis that was resolving without treatment at the 4-month ophthalmology consult, the authors wrote. The mother experienced persistent low-level viremia before and throughout her pregnancy.

Two of the pregnancies occurred after the last monthly injection, during the washout period. Other studies have reported that each long-acting drug, CAB and RPV, can be detected more than 1 year after the last injection. In the new report, plasma CAB and RPV washout concentrations during pregnancy were within the range of those in nonpregnant women, the authors wrote.

Among the 14 participants with non–live birth outcomes, 13 switched to an alternative antiretroviral regimen during pregnancy and maintained virologic suppression through pregnancy and post partum, or until their last viral assessment. The remaining participant received long-acting CAB + RPV and continued this treatment for the duration of their pregnancy.

“It’s a very limited data set, so we’re not in a position to be able to make definitive conclusions around long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine in pregnancy,” Dr. Patel acknowledged. “But the data that we presented among the 25 women who were exposed to cabotegravir-rilpivirine looks reassuring.”

Planned studies during pregnancy

Vani Vannappagari, MBBS, MPH, PhD, global head of epidemiology and real-world evidence at ViiV Healthcare and study coauthor, said in an interview that the initial results are spurring promising new research.

“We are working with an external IMPAACT [International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network] group on a clinical trial ... to try to determine the appropriate dose of long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine during pregnancy,” Dr. Vannappagari said. “The clinical trial will give us the immediate safety, dose information, and viral suppression rates for both the mother and the infant. But long-term safety, especially birth defects and any adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, will come from our antiretroviral pregnancy registry and other noninterventional studies.

“In the very small cohort studied, [in] pregnancies that were continued after exposure to long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine in the first trimester, there were no significant adverse fetal outcomes identified,” he said. “That’s reassuring, as is the fact that at the time these patients were switched in early pregnancy, their viral loads were all undetectable at the time that their pregnancies were diagnosed.”

Neil Silverman, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Infections in Pregnancy Program at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, who was not associated with the study, provided a comment to this news organization.

“The larger question still remains why pregnant women were so actively excluded from the original study design when this trial was evaluating a newer long-acting preparation of two anti-HIV medications that otherwise would be perfectly fine to use during pregnancy?”

Dr. Silverman continued, “In this case, it’s particularly frustrating since the present study was simply evaluating established medications currently being used to manage HIV infection, but in a newer longer-acting mode of administration by an injection every 2 months. If a patient had already been successfully managed on an oral antiviral regimen containing an integrase inhibitor and a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, like the two drugs studied here, it would not be considered reasonable to switch that regimen simply because she was found to be pregnant.”

Dr. Patel and Dr. Vannappagari are employees of ViiV Healthcare and stockholders of GlaxoSmithKline.

This analysis was funded by ViiV Healthcare, and all studies were cofunded by ViiV Healthcare and Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Silverman reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a cautiously optimistic report,

Among 10 live births, there was one birth defect (congenital ptosis, or droopy eyelid), which was not attributed to the trial drugs. There were no instances of perinatal HIV transmission at delivery or during the 1-year follow-up.

“Long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine is the first and only complete injectable regimen potentially available for pregnant women,” first author Parul Patel, PharmD, global medical affairs director for cabotegravir at ViiV Healthcare, said in an interview. The regimen was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in January 2021 for injections every 4 weeks and in February 2022 for injections every 8 weeks.

“Importantly, it can be dosed monthly or every 2 months,” Patel said. “This could be advantageous for women who are experiencing constant change during pregnancy. This could be a consideration for women who might have problems tolerating oral pills during pregnancy or might have problems with emesis.”

The study was published in HIV Medicine.

“We are really pursuing the development of the long-acting version of cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine,” Dr. Patel said. “It’s an industry standard during initial development that you start very conservatively and not allow a woman who is pregnant to continue dosing of a drug while still evaluating its overall safety profile. We really want to understand the use of this agent in nonpregnant adults before exposing pregnant women to active treatment.”

Pregnancies in trials excluding pregnant women

In the paper, Dr. Patel and her coauthors noted the limited data on pregnant women exposed to CAB + RPV. They analyzed pregnancies in four phase 2b/3/3b clinical trials sponsored by ViiV Healthcare and a compassionate use program. All clinical trial participants first received oral CAB + RPV daily for 4 weeks to assess individual tolerance before the experimental long-acting injection of CAB + RPV every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks.

Women participants were required to use highly effective contraception during the trials and for at least 52 weeks after the last injection. Urine pregnancy tests were given at baseline, before each injection, and when pregnancy was suspected. If a pregnancy was detected, CAB + RPV (oral or long-acting injections) was discontinued and the woman switched to an alternative oral antiretroviral, unless she and her physician decided to continue with injections in the compassionate use program.

Pregnancy outcomes

Among 25 reported pregnancies in 22 women during the trial, there were 10 live births. Nine of the mothers who delivered their babies at term had switched to an alternative antiretroviral regimen and maintained virologic suppression throughout pregnancy and post partum, or the last available viral load assessment.

The 10th participant remained on long-acting CAB + RPV during her pregnancy and had a live birth with congenital ptosis that was resolving without treatment at the 4-month ophthalmology consult, the authors wrote. The mother experienced persistent low-level viremia before and throughout her pregnancy.

Two of the pregnancies occurred after the last monthly injection, during the washout period. Other studies have reported that each long-acting drug, CAB and RPV, can be detected more than 1 year after the last injection. In the new report, plasma CAB and RPV washout concentrations during pregnancy were within the range of those in nonpregnant women, the authors wrote.

Among the 14 participants with non–live birth outcomes, 13 switched to an alternative antiretroviral regimen during pregnancy and maintained virologic suppression through pregnancy and post partum, or until their last viral assessment. The remaining participant received long-acting CAB + RPV and continued this treatment for the duration of their pregnancy.

“It’s a very limited data set, so we’re not in a position to be able to make definitive conclusions around long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine in pregnancy,” Dr. Patel acknowledged. “But the data that we presented among the 25 women who were exposed to cabotegravir-rilpivirine looks reassuring.”

Planned studies during pregnancy

Vani Vannappagari, MBBS, MPH, PhD, global head of epidemiology and real-world evidence at ViiV Healthcare and study coauthor, said in an interview that the initial results are spurring promising new research.

“We are working with an external IMPAACT [International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network] group on a clinical trial ... to try to determine the appropriate dose of long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine during pregnancy,” Dr. Vannappagari said. “The clinical trial will give us the immediate safety, dose information, and viral suppression rates for both the mother and the infant. But long-term safety, especially birth defects and any adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, will come from our antiretroviral pregnancy registry and other noninterventional studies.

“In the very small cohort studied, [in] pregnancies that were continued after exposure to long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine in the first trimester, there were no significant adverse fetal outcomes identified,” he said. “That’s reassuring, as is the fact that at the time these patients were switched in early pregnancy, their viral loads were all undetectable at the time that their pregnancies were diagnosed.”

Neil Silverman, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Infections in Pregnancy Program at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, who was not associated with the study, provided a comment to this news organization.

“The larger question still remains why pregnant women were so actively excluded from the original study design when this trial was evaluating a newer long-acting preparation of two anti-HIV medications that otherwise would be perfectly fine to use during pregnancy?”

Dr. Silverman continued, “In this case, it’s particularly frustrating since the present study was simply evaluating established medications currently being used to manage HIV infection, but in a newer longer-acting mode of administration by an injection every 2 months. If a patient had already been successfully managed on an oral antiviral regimen containing an integrase inhibitor and a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, like the two drugs studied here, it would not be considered reasonable to switch that regimen simply because she was found to be pregnant.”

Dr. Patel and Dr. Vannappagari are employees of ViiV Healthcare and stockholders of GlaxoSmithKline.

This analysis was funded by ViiV Healthcare, and all studies were cofunded by ViiV Healthcare and Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Silverman reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a cautiously optimistic report,

Among 10 live births, there was one birth defect (congenital ptosis, or droopy eyelid), which was not attributed to the trial drugs. There were no instances of perinatal HIV transmission at delivery or during the 1-year follow-up.

“Long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine is the first and only complete injectable regimen potentially available for pregnant women,” first author Parul Patel, PharmD, global medical affairs director for cabotegravir at ViiV Healthcare, said in an interview. The regimen was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in January 2021 for injections every 4 weeks and in February 2022 for injections every 8 weeks.

“Importantly, it can be dosed monthly or every 2 months,” Patel said. “This could be advantageous for women who are experiencing constant change during pregnancy. This could be a consideration for women who might have problems tolerating oral pills during pregnancy or might have problems with emesis.”

The study was published in HIV Medicine.

“We are really pursuing the development of the long-acting version of cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine,” Dr. Patel said. “It’s an industry standard during initial development that you start very conservatively and not allow a woman who is pregnant to continue dosing of a drug while still evaluating its overall safety profile. We really want to understand the use of this agent in nonpregnant adults before exposing pregnant women to active treatment.”

Pregnancies in trials excluding pregnant women

In the paper, Dr. Patel and her coauthors noted the limited data on pregnant women exposed to CAB + RPV. They analyzed pregnancies in four phase 2b/3/3b clinical trials sponsored by ViiV Healthcare and a compassionate use program. All clinical trial participants first received oral CAB + RPV daily for 4 weeks to assess individual tolerance before the experimental long-acting injection of CAB + RPV every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks.

Women participants were required to use highly effective contraception during the trials and for at least 52 weeks after the last injection. Urine pregnancy tests were given at baseline, before each injection, and when pregnancy was suspected. If a pregnancy was detected, CAB + RPV (oral or long-acting injections) was discontinued and the woman switched to an alternative oral antiretroviral, unless she and her physician decided to continue with injections in the compassionate use program.

Pregnancy outcomes

Among 25 reported pregnancies in 22 women during the trial, there were 10 live births. Nine of the mothers who delivered their babies at term had switched to an alternative antiretroviral regimen and maintained virologic suppression throughout pregnancy and post partum, or the last available viral load assessment.

The 10th participant remained on long-acting CAB + RPV during her pregnancy and had a live birth with congenital ptosis that was resolving without treatment at the 4-month ophthalmology consult, the authors wrote. The mother experienced persistent low-level viremia before and throughout her pregnancy.

Two of the pregnancies occurred after the last monthly injection, during the washout period. Other studies have reported that each long-acting drug, CAB and RPV, can be detected more than 1 year after the last injection. In the new report, plasma CAB and RPV washout concentrations during pregnancy were within the range of those in nonpregnant women, the authors wrote.

Among the 14 participants with non–live birth outcomes, 13 switched to an alternative antiretroviral regimen during pregnancy and maintained virologic suppression through pregnancy and post partum, or until their last viral assessment. The remaining participant received long-acting CAB + RPV and continued this treatment for the duration of their pregnancy.

“It’s a very limited data set, so we’re not in a position to be able to make definitive conclusions around long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine in pregnancy,” Dr. Patel acknowledged. “But the data that we presented among the 25 women who were exposed to cabotegravir-rilpivirine looks reassuring.”

Planned studies during pregnancy

Vani Vannappagari, MBBS, MPH, PhD, global head of epidemiology and real-world evidence at ViiV Healthcare and study coauthor, said in an interview that the initial results are spurring promising new research.

“We are working with an external IMPAACT [International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network] group on a clinical trial ... to try to determine the appropriate dose of long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine during pregnancy,” Dr. Vannappagari said. “The clinical trial will give us the immediate safety, dose information, and viral suppression rates for both the mother and the infant. But long-term safety, especially birth defects and any adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, will come from our antiretroviral pregnancy registry and other noninterventional studies.

“In the very small cohort studied, [in] pregnancies that were continued after exposure to long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine in the first trimester, there were no significant adverse fetal outcomes identified,” he said. “That’s reassuring, as is the fact that at the time these patients were switched in early pregnancy, their viral loads were all undetectable at the time that their pregnancies were diagnosed.”

Neil Silverman, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Infections in Pregnancy Program at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, who was not associated with the study, provided a comment to this news organization.

“The larger question still remains why pregnant women were so actively excluded from the original study design when this trial was evaluating a newer long-acting preparation of two anti-HIV medications that otherwise would be perfectly fine to use during pregnancy?”

Dr. Silverman continued, “In this case, it’s particularly frustrating since the present study was simply evaluating established medications currently being used to manage HIV infection, but in a newer longer-acting mode of administration by an injection every 2 months. If a patient had already been successfully managed on an oral antiviral regimen containing an integrase inhibitor and a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, like the two drugs studied here, it would not be considered reasonable to switch that regimen simply because she was found to be pregnant.”

Dr. Patel and Dr. Vannappagari are employees of ViiV Healthcare and stockholders of GlaxoSmithKline.

This analysis was funded by ViiV Healthcare, and all studies were cofunded by ViiV Healthcare and Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Silverman reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HIV MEDICINE

Future HIV PrEP innovations aim to address adherence, women’s health, and combination treatments

TAMPA – Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has shown to be effective in many clinical and real-world studies, but concerns remain, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care (ANAC).

Only about 20% of people who could benefit from PrEP use the preventative medication, for example. Another concern is adherence, as regular use generally drops off over time, rarely lasting more than a few months for most people.

Furthermore, most studies to date evaluated safety and effectiveness of PrEP options among men who have sex with men. Now the focus is increasing on other populations, including women at risk of HIV exposure.

Researchers working on new forms and formulations of PrEP are looking for ways to address those challenges.

said Craig W. Hendrix, MD, professor and director of the Division of Clinical Pharmacology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

“What I hear a lot of folks say [is] there are two or three options for PrEP, so why do we need more? We need choices that fit into a broader range of lifestyles,” Dr. Hendrix said.

For example, a medically fortified douche containing PrEP might be more likely to be used by people who use a douche before or after sex on a regular basis. This is called a “behaviorally congruent” strategy, Dr. Hendrix said.

In addition to a medical douche, formulations designed to continuously deliver PrEP, such as a subdermal implant, are in the works as well.

Another option for women, the dapivirine vaginal ring, is available internationally but not in the United States. “It was withdrawn from [Food and Drug Administration] consideration by the sponsor. I think it’s a huge loss not to have that,” Dr. Hendrix said.

During development, “frequent expulsions forced reformulation to a less stiff ring,” Dr. Hendrix said. “I don’t imagine that’s terrific, but it shows how important it is to have something that fits the anatomy and the lifestyle.”

“Currently, we have in the U.S. three licensed, really terrific options for PrEP, and they’re all for men that have sex with men and transgender women,” Dr. Hendrix said.

Three current options

The three current PrEP regimens in the United States often go by their abbreviations: F/TDF, F/TAF, and CAB-IM.

- F/TDF is emtricitabine (F) 200 mg in combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg (Truvada, Gilead or generics)

- F/TAF is emtricitabine (F) 200 mg in combination with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) 25 mg (Descovy, Gilead)

- CAB-IM is cabotegravir (CAB) 600 mg injection (Apretude, GlaxoSmithKline)

There is an important distinction: Daily oral PrEP with F/TDF is recommended to prevent HIV infection among all people at risk through sex or injection drug use. Daily oral PrEP with F/TAF is recommended to prevent HIV infection among people at risk through sex, excluding people at risk through receptive vaginal sex, the CDC notes.

The cost-effectiveness of the injection remains a potential issue, Dr. Hendrix said. On the other hand, “cost-effectiveness goes out the window if there is no adherence.”

An active pipeline

There are 24 new PrEP products in development, as well as 24 other multipurpose prevention technologies (MPTs), which are combination products containing PrEP and one or two other medications.

These 48 products include 28 unique antiviral and contraceptive drugs and 12 delivery methods or formulations. “Why so many?” Dr. Hendrix asked. “Many will not make it through development.”

Pills that include HIV PrEP and contraception or PrEP and sexually transmitted infection (STI) treatment are being evaluated, for example. “HIV risk, pregnancy risk, and other viral STIs overlap. Ideally, you can have one target for all three. That would increase efficiency of dosing and adherence,” Dr. Hendrix said.

Dual prevention pills (DPPs) hypothetically provide HIV PrEP and contraception better than either product alone, Dr. Hendrix said. Plans are to market them as family planning or women’s health products to avoid any stigma or distrust associated with HIV PrEP. An initial rollout is planned in 2024 in sub-Saharan Africa where the unmet need is highest, he added.

“Imagine how effective this could be in women in the United States,” Dr. Hendrix said. “My hope is fourth-quarter 2024” availability in the United States.

A way to prevent STIs and HIV in an all-in-one product “would be terrific,” Dr. Hendrix said.

“I think we’re going to see a lot more innovation going in that direction. The pill is close. The other things are going to be further off because the regulatory pathway is a little more complicated.”

Longer lasting protection?

All of the innovations have gone one of two directions, Dr. Hendrix said. One direction is to make PrEP even longer acting, “so that you have even less to worry [about] in terms of adherence.”

Going forward, “most of the focus has all been on continuously acting or long-active PrEP. It’s getting longer and longer: We’ve got 2 months, and they’re looking at a 6-month subcutaneous injection,” Dr. Hendrix said. The investigational agent lenacapavir is in development as PrEP, as well as for HIV treatment.

“This could get us from 2 to 6 months,” Dr. Hendrix said.

Some of the subcutaneous implants look as if they could provide PrEP for up to 12 months, he added. “An implant could also avoid peaks and troughs with bi-monthly injections.”

On-demand PrEP

The other direction is on-demand. “This is for the folks that don’t want drug in their body all the time. They only want it when they need it. And a twist on that ... is actually using products that are already used with sex now but medicating them.”

On-demand rectal options include a medicated douche and a fast-dissolving insert or suppository.

Fast-dissolving vaginal inserts are also in development. “These inserts are small, easy to store, inexpensive, and possibly inapparent to a partner,” Dr. Hendrix said.

Phase 2 studies will need to determine if these products “fit into folks’ active sex lives,” he said. “There’s still a need for human-friendly, human-designed products.”

A rectal microbicide that got as far as Phase 2 research provides a cautionary tale. The concentrations and the biology worked fine, Dr. Hendrix said. “It was a gel with an applicator, and it just was not liked by the folks in the study.” He added, “Your adherence is going to be in the tank if you’ve got a product that people don’t like to use.”

‘Extremely excited’

Asked for her perspective on Dr. Hendrix’s presentation, session moderator Rasheeta D. Chandler, PhD, RN, an associate professor at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University, Atlanta, said: “I am extremely excited, because I work with cisgender women, particularly with underserved women and women of color, and there’s a tendency to focus on men who have sex with men.”

“I understand, because they are the population that is most affected, but Black women are also extremely affected by this disease,” Dr. Chandler told this news organization.

Dr. Chandler applauded Dr. Hendrix for addressing women’s health needs as well and not treating PrEP in women “as an afterthought.”

“Finally, our voices are being heard that [PrEP] should be equitable across all different types of individuals who identify differently in a sexual context,” Dr. Chandler said.

More work is warranted to evaluate PrEP in other populations, including transgender men and individuals who inject drugs, Dr. Hendrix said.

For more information and updates on HIV PrEP and MPTs, visit the website of the nonprofit AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition.

Dr. Hendrix has disclosed receiving research grants from Gilead and Merck. Dr. Chandler has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TAMPA – Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has shown to be effective in many clinical and real-world studies, but concerns remain, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care (ANAC).

Only about 20% of people who could benefit from PrEP use the preventative medication, for example. Another concern is adherence, as regular use generally drops off over time, rarely lasting more than a few months for most people.

Furthermore, most studies to date evaluated safety and effectiveness of PrEP options among men who have sex with men. Now the focus is increasing on other populations, including women at risk of HIV exposure.

Researchers working on new forms and formulations of PrEP are looking for ways to address those challenges.

said Craig W. Hendrix, MD, professor and director of the Division of Clinical Pharmacology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

“What I hear a lot of folks say [is] there are two or three options for PrEP, so why do we need more? We need choices that fit into a broader range of lifestyles,” Dr. Hendrix said.

For example, a medically fortified douche containing PrEP might be more likely to be used by people who use a douche before or after sex on a regular basis. This is called a “behaviorally congruent” strategy, Dr. Hendrix said.