User login

Hypertension goes unmedicated in 40% of adults

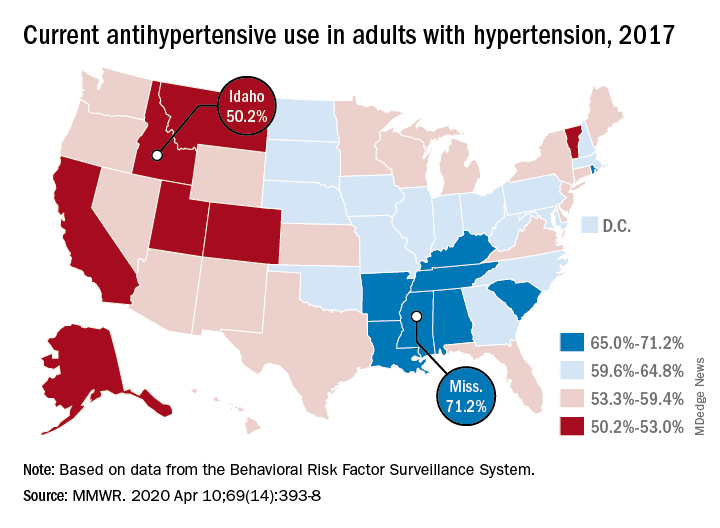

Roughly 30% of adults in the United States had hypertension in 2017, and just under 60% of those adults reported using antihypertensive medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is, however, quite a bit of variation from those age-standardized national figures when state-level data are considered.

In Alabama and West Virginia, the prevalence of hypertension in 2017 was 38.6%, the highest in the country, with Arkansas (38.5%) and Mississippi (38.2%) not far behind. Meanwhile, Minnesota came in with a lowest-in-the-nation rate of 24.3%, which was nearly matched by Colorado at 24.8%, Claudine M. Samanic, PhD, and associates wrote in the MMWR.

There was also a considerable gap between the states in hypertensive adults’ self-reported use of antihypertensive drugs, which was generally higher in the states with a greater prevalence of disease, they noted.

Adults in Mississippi were the most likely (71.2%) to be taking medication, along with those in Alabama (70.5%) and Arkansas (69.3%). Idaho occupied the other end of the scale with a rate of 50.2%, while Montana and Vermont were slightly better at 51.7%, based on survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was higher in older age groups, highest among blacks, and higher among women [64.0%] than men [56.7%]. This overall gender difference has been reported previously, but the reasons are unclear,” wrote Dr. Samanic and associates at the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

The BRFSS data for 2017 are based on based on interviews with 450,016 adults. Respondents were asked, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?” and were considered to have hypertension if they answered yes.

SOURCE: Samanic CM et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 10;69(14):393-8.

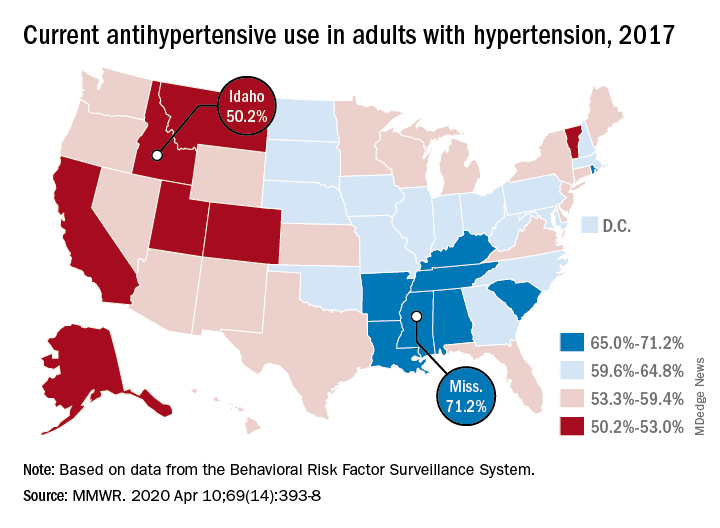

Roughly 30% of adults in the United States had hypertension in 2017, and just under 60% of those adults reported using antihypertensive medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is, however, quite a bit of variation from those age-standardized national figures when state-level data are considered.

In Alabama and West Virginia, the prevalence of hypertension in 2017 was 38.6%, the highest in the country, with Arkansas (38.5%) and Mississippi (38.2%) not far behind. Meanwhile, Minnesota came in with a lowest-in-the-nation rate of 24.3%, which was nearly matched by Colorado at 24.8%, Claudine M. Samanic, PhD, and associates wrote in the MMWR.

There was also a considerable gap between the states in hypertensive adults’ self-reported use of antihypertensive drugs, which was generally higher in the states with a greater prevalence of disease, they noted.

Adults in Mississippi were the most likely (71.2%) to be taking medication, along with those in Alabama (70.5%) and Arkansas (69.3%). Idaho occupied the other end of the scale with a rate of 50.2%, while Montana and Vermont were slightly better at 51.7%, based on survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was higher in older age groups, highest among blacks, and higher among women [64.0%] than men [56.7%]. This overall gender difference has been reported previously, but the reasons are unclear,” wrote Dr. Samanic and associates at the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

The BRFSS data for 2017 are based on based on interviews with 450,016 adults. Respondents were asked, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?” and were considered to have hypertension if they answered yes.

SOURCE: Samanic CM et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 10;69(14):393-8.

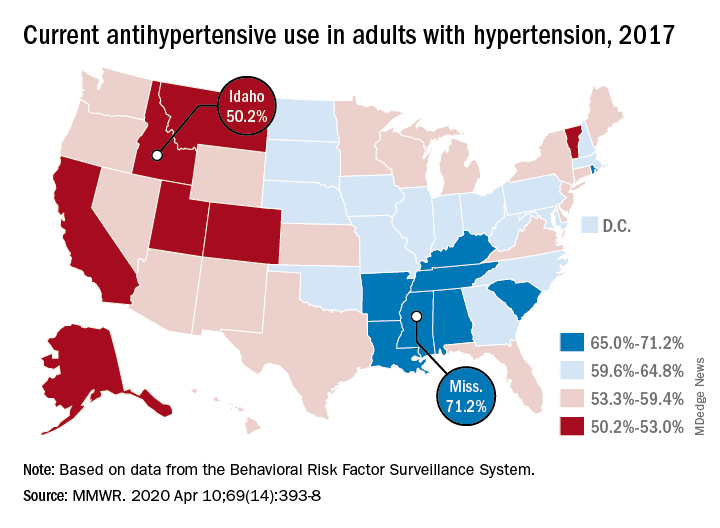

Roughly 30% of adults in the United States had hypertension in 2017, and just under 60% of those adults reported using antihypertensive medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is, however, quite a bit of variation from those age-standardized national figures when state-level data are considered.

In Alabama and West Virginia, the prevalence of hypertension in 2017 was 38.6%, the highest in the country, with Arkansas (38.5%) and Mississippi (38.2%) not far behind. Meanwhile, Minnesota came in with a lowest-in-the-nation rate of 24.3%, which was nearly matched by Colorado at 24.8%, Claudine M. Samanic, PhD, and associates wrote in the MMWR.

There was also a considerable gap between the states in hypertensive adults’ self-reported use of antihypertensive drugs, which was generally higher in the states with a greater prevalence of disease, they noted.

Adults in Mississippi were the most likely (71.2%) to be taking medication, along with those in Alabama (70.5%) and Arkansas (69.3%). Idaho occupied the other end of the scale with a rate of 50.2%, while Montana and Vermont were slightly better at 51.7%, based on survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was higher in older age groups, highest among blacks, and higher among women [64.0%] than men [56.7%]. This overall gender difference has been reported previously, but the reasons are unclear,” wrote Dr. Samanic and associates at the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

The BRFSS data for 2017 are based on based on interviews with 450,016 adults. Respondents were asked, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?” and were considered to have hypertension if they answered yes.

SOURCE: Samanic CM et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 10;69(14):393-8.

FROM THE MMWR

BPA analogs increase blood pressure in animal study

findings in a new study have shown.

Researchers tested exposures to BPA, as well as bisphenol-S (BPS) and bisphenol-F (BPF), which have been introduced in recent years as BPA alternatives and are now increasingly detectable in human and animal tissues. BPS and BPF are often found in products labeled as “BPA free.”

BPS and BPF have similar physiochemical properties to BPA, and there is concern over their effects.

But their physiological impact is not yet clear, according to Puliyur MohanKumar, DVM, PhD, of the University of Georgia Regenerative Bioscience Center, Athens. “We are exposed to BPA and related compounds on a regular basis, and the important thing is that BPA and related compounds easily cross the placental barrier,” Dr. MohanKumar said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study had been slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society's annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues exposed pregnant rats to BPA, BPS, or BPF. When the offspring reached adulthood, the researchers implanted them with radiotelemetry devices to track systolic and diastolic blood pressure, which they measured every 10 minutes over a 24-hour period. This was repeated once a week for 11 weeks.

“The female offspring had elevated systolic as well as diastolic blood pressure, and this was an increase of about 8 mm [Hg] higher than the control animals. That was pretty significant. Keeping these animals at such a prehypertensive state for such a long period of time is going to [lead to] lots of cardiovascular issues later on,” said Dr. MohanKumar.

Robert Sargis, MD, PhD, professor of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Illinois at Chicago, noted that, although animal studies don’t necessarily translate to similar outcomes in humans, the results are cause for concern.

“What’s particularly interesting, is that there is whole area of essential hypertension, where people develop hypertension and we don’t really know why. We just treat it,” he said in an interview. “But thinking about biological origins [of hypertension] is potentially interesting for a couple of reasons. These bisphenol compounds are really common. Most Americans are exposed to bisphenol A, and it’s been associated with other adverse metabolic effects, including alterations to body weight and glucose homeostasis.

“[These findings] feed into a whole series of studies that have begun to look at the BPA replacements and the fact that they may be, at best, as bad as BPA, and at worst, possibly slightly worse, depending on which outcomes you’re looking at,” Dr. Sargis added.

In the study, seven pregnant rats were orally exposed to saline, four pregnant rats to 5 mcg/kg BPA, four to 5 mcg/kg BPS, and five to 1 mcg/kg BPF during days 6-21 of pregnancy. The lower dose of BPF was used because a dose of 5 mcg/kg proved too toxic. When the offspring reached adulthood, the researchers implanted radiotelemetry devices in the offspring’s femoral artery.

Mean daytime systolic BP was highest in the BPA group (133.3 mg Hg; P < .05), followed by BPS (132.5 mm Hg; P < .05) and BPF (129.2 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 125.2 mm Hg in controls. Nighttime systolic BP was again highest in the BPA group (134.2 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPS (133.2 mm Hg; P < .05) and BPF (129.6 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 125.1 mm Hg in controls.

During the day, diastolic BP was highest in the BPS group (91.3 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPA (88.8 mm Hg; nonsignificant) and BPF (88.6 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 84.1 mm Hg in controls. At night, diastolic BP was highest in the BPS group (89.7 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPA (89.6 mm Hg; P < .01) and BPF (88.6 mm Hg; P < .01), compared with 83.3 mm Hg in controls.

During the day, mean arterial pressure was highest in the BPA group (110.5 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPS (108.9 mm Hg; P < .01) and BPF (105.2 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 102.6 mm Hg in controls. At night, mean arterial pressure was highest in BPS (108.6 mm Hg; P < .05), followed by BPA (107.5 mm Hg; nonsignificant) and BPF (105.7 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 101.8 mm Hg in controls.

“These results indicate that prenatal exposure to low levels of BPA analogs has a profound effect on hypertension” in the offspring of pregnant rats exposed to bisphenols, Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues wrote in the abstract.

He noted during his presentation that he and his colleagues plan to repeat the study in male offspring to determine if there are sex differences.

Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Sargis also reported no conflicts of interest.

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

SOURCE: MohanKumar P et al. ENDO 2020, Abstract 719.

This article was updated on 4/17/2020.

findings in a new study have shown.

Researchers tested exposures to BPA, as well as bisphenol-S (BPS) and bisphenol-F (BPF), which have been introduced in recent years as BPA alternatives and are now increasingly detectable in human and animal tissues. BPS and BPF are often found in products labeled as “BPA free.”

BPS and BPF have similar physiochemical properties to BPA, and there is concern over their effects.

But their physiological impact is not yet clear, according to Puliyur MohanKumar, DVM, PhD, of the University of Georgia Regenerative Bioscience Center, Athens. “We are exposed to BPA and related compounds on a regular basis, and the important thing is that BPA and related compounds easily cross the placental barrier,” Dr. MohanKumar said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study had been slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society's annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues exposed pregnant rats to BPA, BPS, or BPF. When the offspring reached adulthood, the researchers implanted them with radiotelemetry devices to track systolic and diastolic blood pressure, which they measured every 10 minutes over a 24-hour period. This was repeated once a week for 11 weeks.

“The female offspring had elevated systolic as well as diastolic blood pressure, and this was an increase of about 8 mm [Hg] higher than the control animals. That was pretty significant. Keeping these animals at such a prehypertensive state for such a long period of time is going to [lead to] lots of cardiovascular issues later on,” said Dr. MohanKumar.

Robert Sargis, MD, PhD, professor of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Illinois at Chicago, noted that, although animal studies don’t necessarily translate to similar outcomes in humans, the results are cause for concern.

“What’s particularly interesting, is that there is whole area of essential hypertension, where people develop hypertension and we don’t really know why. We just treat it,” he said in an interview. “But thinking about biological origins [of hypertension] is potentially interesting for a couple of reasons. These bisphenol compounds are really common. Most Americans are exposed to bisphenol A, and it’s been associated with other adverse metabolic effects, including alterations to body weight and glucose homeostasis.

“[These findings] feed into a whole series of studies that have begun to look at the BPA replacements and the fact that they may be, at best, as bad as BPA, and at worst, possibly slightly worse, depending on which outcomes you’re looking at,” Dr. Sargis added.

In the study, seven pregnant rats were orally exposed to saline, four pregnant rats to 5 mcg/kg BPA, four to 5 mcg/kg BPS, and five to 1 mcg/kg BPF during days 6-21 of pregnancy. The lower dose of BPF was used because a dose of 5 mcg/kg proved too toxic. When the offspring reached adulthood, the researchers implanted radiotelemetry devices in the offspring’s femoral artery.

Mean daytime systolic BP was highest in the BPA group (133.3 mg Hg; P < .05), followed by BPS (132.5 mm Hg; P < .05) and BPF (129.2 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 125.2 mm Hg in controls. Nighttime systolic BP was again highest in the BPA group (134.2 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPS (133.2 mm Hg; P < .05) and BPF (129.6 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 125.1 mm Hg in controls.

During the day, diastolic BP was highest in the BPS group (91.3 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPA (88.8 mm Hg; nonsignificant) and BPF (88.6 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 84.1 mm Hg in controls. At night, diastolic BP was highest in the BPS group (89.7 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPA (89.6 mm Hg; P < .01) and BPF (88.6 mm Hg; P < .01), compared with 83.3 mm Hg in controls.

During the day, mean arterial pressure was highest in the BPA group (110.5 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPS (108.9 mm Hg; P < .01) and BPF (105.2 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 102.6 mm Hg in controls. At night, mean arterial pressure was highest in BPS (108.6 mm Hg; P < .05), followed by BPA (107.5 mm Hg; nonsignificant) and BPF (105.7 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 101.8 mm Hg in controls.

“These results indicate that prenatal exposure to low levels of BPA analogs has a profound effect on hypertension” in the offspring of pregnant rats exposed to bisphenols, Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues wrote in the abstract.

He noted during his presentation that he and his colleagues plan to repeat the study in male offspring to determine if there are sex differences.

Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Sargis also reported no conflicts of interest.

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

SOURCE: MohanKumar P et al. ENDO 2020, Abstract 719.

This article was updated on 4/17/2020.

findings in a new study have shown.

Researchers tested exposures to BPA, as well as bisphenol-S (BPS) and bisphenol-F (BPF), which have been introduced in recent years as BPA alternatives and are now increasingly detectable in human and animal tissues. BPS and BPF are often found in products labeled as “BPA free.”

BPS and BPF have similar physiochemical properties to BPA, and there is concern over their effects.

But their physiological impact is not yet clear, according to Puliyur MohanKumar, DVM, PhD, of the University of Georgia Regenerative Bioscience Center, Athens. “We are exposed to BPA and related compounds on a regular basis, and the important thing is that BPA and related compounds easily cross the placental barrier,” Dr. MohanKumar said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study had been slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society's annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues exposed pregnant rats to BPA, BPS, or BPF. When the offspring reached adulthood, the researchers implanted them with radiotelemetry devices to track systolic and diastolic blood pressure, which they measured every 10 minutes over a 24-hour period. This was repeated once a week for 11 weeks.

“The female offspring had elevated systolic as well as diastolic blood pressure, and this was an increase of about 8 mm [Hg] higher than the control animals. That was pretty significant. Keeping these animals at such a prehypertensive state for such a long period of time is going to [lead to] lots of cardiovascular issues later on,” said Dr. MohanKumar.

Robert Sargis, MD, PhD, professor of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Illinois at Chicago, noted that, although animal studies don’t necessarily translate to similar outcomes in humans, the results are cause for concern.

“What’s particularly interesting, is that there is whole area of essential hypertension, where people develop hypertension and we don’t really know why. We just treat it,” he said in an interview. “But thinking about biological origins [of hypertension] is potentially interesting for a couple of reasons. These bisphenol compounds are really common. Most Americans are exposed to bisphenol A, and it’s been associated with other adverse metabolic effects, including alterations to body weight and glucose homeostasis.

“[These findings] feed into a whole series of studies that have begun to look at the BPA replacements and the fact that they may be, at best, as bad as BPA, and at worst, possibly slightly worse, depending on which outcomes you’re looking at,” Dr. Sargis added.

In the study, seven pregnant rats were orally exposed to saline, four pregnant rats to 5 mcg/kg BPA, four to 5 mcg/kg BPS, and five to 1 mcg/kg BPF during days 6-21 of pregnancy. The lower dose of BPF was used because a dose of 5 mcg/kg proved too toxic. When the offspring reached adulthood, the researchers implanted radiotelemetry devices in the offspring’s femoral artery.

Mean daytime systolic BP was highest in the BPA group (133.3 mg Hg; P < .05), followed by BPS (132.5 mm Hg; P < .05) and BPF (129.2 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 125.2 mm Hg in controls. Nighttime systolic BP was again highest in the BPA group (134.2 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPS (133.2 mm Hg; P < .05) and BPF (129.6 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 125.1 mm Hg in controls.

During the day, diastolic BP was highest in the BPS group (91.3 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPA (88.8 mm Hg; nonsignificant) and BPF (88.6 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 84.1 mm Hg in controls. At night, diastolic BP was highest in the BPS group (89.7 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPA (89.6 mm Hg; P < .01) and BPF (88.6 mm Hg; P < .01), compared with 83.3 mm Hg in controls.

During the day, mean arterial pressure was highest in the BPA group (110.5 mm Hg; P < .01), followed by BPS (108.9 mm Hg; P < .01) and BPF (105.2 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 102.6 mm Hg in controls. At night, mean arterial pressure was highest in BPS (108.6 mm Hg; P < .05), followed by BPA (107.5 mm Hg; nonsignificant) and BPF (105.7 mm Hg; nonsignificant), compared with 101.8 mm Hg in controls.

“These results indicate that prenatal exposure to low levels of BPA analogs has a profound effect on hypertension” in the offspring of pregnant rats exposed to bisphenols, Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues wrote in the abstract.

He noted during his presentation that he and his colleagues plan to repeat the study in male offspring to determine if there are sex differences.

Dr. MohanKumar and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Sargis also reported no conflicts of interest.

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

SOURCE: MohanKumar P et al. ENDO 2020, Abstract 719.

This article was updated on 4/17/2020.

FROM ENDO 2020

Renal denervation shown safe and effective in pivotal trial

Catheter-based renal denervation took a step closer to attaining legitimacy as a nonpharmacologic treatment for hypertension with presentation of the primary results of the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED pivotal trial at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We saw clinically meaningful blood pressure reductions at 3 months,” reported Michael Boehm, MD, chief of cardiology at Saarland University Hospital in Homburg, Germany.

That’s encouraging news, as renal denervation (RDN) was nearly abandoned as a potential treatment for hypertension in the wake of the unexpectedly negative results of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393-401). However, post hoc analysis of the trial revealed significant shortcomings in design and execution, and a more rigorous development program for the percutaneous device-based therapy is well underway.

The SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED pivotal trial was designed under Food and Drug Administration guidance to show whether RDN reduces blood pressure in patients with untreated hypertension. The prospective study included 331 off-medication patients in nine countries who were randomized to RDN or a sham procedure, then followed in double-blind fashion for 3 months.

The primary outcome was change in 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure from baseline to 3 months. From a mean baseline 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure of 151.4/98 mm Hg, patients in the RDN group averaged a 4.7 mm Hg decrease in 24-hour SBP, which was 4 mm Hg more than in sham-treated controls. Statistically, this translated to a greater than 99.9% probability that RDN was superior to sham therapy. The RDN group also experienced a mean 3.7–mm Hg reduction in 24-hour DBP, compared with a 0.8–mm Hg decrease in controls.

Office SBP – the secondary endpoint – decreased by a mean of 9.2 mm Hg with RDN, compared with 2.5 mm Hg in controls.

These results probably understate the true antihypertensive effect of RDN for two reasons, Dr. Boehm noted. For one, previous studies have shown that the magnitude of blood pressure lowering continues to increase for up to 1-2 years following the procedure, whereas the off-medication assessment in SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED ended at 3 months for ethical and safety reasons. Also, 17% of patients in the control arm were withdrawn from the study and placed on antihypertensive medication because their office SBP reached 180 mm Hg or more, as compared to 9.6% of the RDN group.

A key finding was that RDN lowered blood pressure around the clock, including nighttime and early morning, the hours of greatest cardiovascular risk and a time when some antihypertensive medications are less effective at blood pressure control, the cardiologist observed.

The RDN safety picture was reassuring, with no strokes, myocardial infarctions, major bleeding, or acute deterioration in kidney function.

A surprising finding was that, even though participants underwent blood and urine testing for the presence of antihypertensive drugs at baseline to ensure they were off medication, and were told they would be retested at 3 months, 5%-9% nonetheless tested positive at the second test.

That elicited a comment from session chair Richard A. Chazal, MD, of Fort Myers, Fla.: “I must say, as a clinician who sometimes has trouble getting his patients to take antihypertensives, it’s fascinating that some of the people that you asked not to take the medications were taking them.”

While the primary outcome in SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED was the 3-month reduction in blood pressure while off of antihypertensive medication, the ongoing second phase of the trial may have greater clinical relevance. At 3 months, participants are being placed on antihypertensive medication and uptitrated to target, with unblinding at 6 months. The purpose is to see how many RDN recipients don’t need antihypertensive drugs, as well as whether those that do require less medication than the patients who didn’t undergo RDN.

Dr. Boehm characterized RDN as a work in progress. Two major limitations that are the focus of intense research are the lack of a predictor as to which patients are most likely to respond to what is after all an invasive procedure, and the current inability intraprocedurally to tell if sufficient RDN has been achieved.

“Frankly speaking, there is no technology during the procedure to see how efficacious the procedure was,” he explained.

Discussant Dhanunaja Lakkireddy, MD, deemed the mean 4.7–mm Hg reduction in 24-hour SBP “reasonably impressive – that’s actually a pretty good number for an antihypertensive clinical trial.” He was also favorably impressed by RDN’s safety in a 44-site study.

“The drops in blood pressure are not enough to really make a case for renal denervation to be a standalone therapy. But adding it as an adjunct to standard medications may be a very reasonable strategy to adopt. This is a fantastic signal for something that can be brought along as a long-term add-on to antihypertensive medications,” commented Dr. Lakkireddy, chair of the ACC Electrophysiology Council and medical director of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute.

Simultaneous with Dr. Boehm’s presentation, the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal Trial details were published online (Lancet 2020 Mar 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30554-7).

The study was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Boehm reported serving as a consultant to that company and Abbott, Amgen, Astra, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Novartis, ReCor, Servier, and Vifor.

SOURCE: Boehm M. ACC 2020, Abstract 406-15.

Catheter-based renal denervation took a step closer to attaining legitimacy as a nonpharmacologic treatment for hypertension with presentation of the primary results of the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED pivotal trial at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We saw clinically meaningful blood pressure reductions at 3 months,” reported Michael Boehm, MD, chief of cardiology at Saarland University Hospital in Homburg, Germany.

That’s encouraging news, as renal denervation (RDN) was nearly abandoned as a potential treatment for hypertension in the wake of the unexpectedly negative results of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393-401). However, post hoc analysis of the trial revealed significant shortcomings in design and execution, and a more rigorous development program for the percutaneous device-based therapy is well underway.

The SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED pivotal trial was designed under Food and Drug Administration guidance to show whether RDN reduces blood pressure in patients with untreated hypertension. The prospective study included 331 off-medication patients in nine countries who were randomized to RDN or a sham procedure, then followed in double-blind fashion for 3 months.

The primary outcome was change in 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure from baseline to 3 months. From a mean baseline 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure of 151.4/98 mm Hg, patients in the RDN group averaged a 4.7 mm Hg decrease in 24-hour SBP, which was 4 mm Hg more than in sham-treated controls. Statistically, this translated to a greater than 99.9% probability that RDN was superior to sham therapy. The RDN group also experienced a mean 3.7–mm Hg reduction in 24-hour DBP, compared with a 0.8–mm Hg decrease in controls.

Office SBP – the secondary endpoint – decreased by a mean of 9.2 mm Hg with RDN, compared with 2.5 mm Hg in controls.

These results probably understate the true antihypertensive effect of RDN for two reasons, Dr. Boehm noted. For one, previous studies have shown that the magnitude of blood pressure lowering continues to increase for up to 1-2 years following the procedure, whereas the off-medication assessment in SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED ended at 3 months for ethical and safety reasons. Also, 17% of patients in the control arm were withdrawn from the study and placed on antihypertensive medication because their office SBP reached 180 mm Hg or more, as compared to 9.6% of the RDN group.

A key finding was that RDN lowered blood pressure around the clock, including nighttime and early morning, the hours of greatest cardiovascular risk and a time when some antihypertensive medications are less effective at blood pressure control, the cardiologist observed.

The RDN safety picture was reassuring, with no strokes, myocardial infarctions, major bleeding, or acute deterioration in kidney function.

A surprising finding was that, even though participants underwent blood and urine testing for the presence of antihypertensive drugs at baseline to ensure they were off medication, and were told they would be retested at 3 months, 5%-9% nonetheless tested positive at the second test.

That elicited a comment from session chair Richard A. Chazal, MD, of Fort Myers, Fla.: “I must say, as a clinician who sometimes has trouble getting his patients to take antihypertensives, it’s fascinating that some of the people that you asked not to take the medications were taking them.”

While the primary outcome in SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED was the 3-month reduction in blood pressure while off of antihypertensive medication, the ongoing second phase of the trial may have greater clinical relevance. At 3 months, participants are being placed on antihypertensive medication and uptitrated to target, with unblinding at 6 months. The purpose is to see how many RDN recipients don’t need antihypertensive drugs, as well as whether those that do require less medication than the patients who didn’t undergo RDN.

Dr. Boehm characterized RDN as a work in progress. Two major limitations that are the focus of intense research are the lack of a predictor as to which patients are most likely to respond to what is after all an invasive procedure, and the current inability intraprocedurally to tell if sufficient RDN has been achieved.

“Frankly speaking, there is no technology during the procedure to see how efficacious the procedure was,” he explained.

Discussant Dhanunaja Lakkireddy, MD, deemed the mean 4.7–mm Hg reduction in 24-hour SBP “reasonably impressive – that’s actually a pretty good number for an antihypertensive clinical trial.” He was also favorably impressed by RDN’s safety in a 44-site study.

“The drops in blood pressure are not enough to really make a case for renal denervation to be a standalone therapy. But adding it as an adjunct to standard medications may be a very reasonable strategy to adopt. This is a fantastic signal for something that can be brought along as a long-term add-on to antihypertensive medications,” commented Dr. Lakkireddy, chair of the ACC Electrophysiology Council and medical director of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute.

Simultaneous with Dr. Boehm’s presentation, the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal Trial details were published online (Lancet 2020 Mar 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30554-7).

The study was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Boehm reported serving as a consultant to that company and Abbott, Amgen, Astra, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Novartis, ReCor, Servier, and Vifor.

SOURCE: Boehm M. ACC 2020, Abstract 406-15.

Catheter-based renal denervation took a step closer to attaining legitimacy as a nonpharmacologic treatment for hypertension with presentation of the primary results of the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED pivotal trial at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We saw clinically meaningful blood pressure reductions at 3 months,” reported Michael Boehm, MD, chief of cardiology at Saarland University Hospital in Homburg, Germany.

That’s encouraging news, as renal denervation (RDN) was nearly abandoned as a potential treatment for hypertension in the wake of the unexpectedly negative results of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393-401). However, post hoc analysis of the trial revealed significant shortcomings in design and execution, and a more rigorous development program for the percutaneous device-based therapy is well underway.

The SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED pivotal trial was designed under Food and Drug Administration guidance to show whether RDN reduces blood pressure in patients with untreated hypertension. The prospective study included 331 off-medication patients in nine countries who were randomized to RDN or a sham procedure, then followed in double-blind fashion for 3 months.

The primary outcome was change in 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure from baseline to 3 months. From a mean baseline 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure of 151.4/98 mm Hg, patients in the RDN group averaged a 4.7 mm Hg decrease in 24-hour SBP, which was 4 mm Hg more than in sham-treated controls. Statistically, this translated to a greater than 99.9% probability that RDN was superior to sham therapy. The RDN group also experienced a mean 3.7–mm Hg reduction in 24-hour DBP, compared with a 0.8–mm Hg decrease in controls.

Office SBP – the secondary endpoint – decreased by a mean of 9.2 mm Hg with RDN, compared with 2.5 mm Hg in controls.

These results probably understate the true antihypertensive effect of RDN for two reasons, Dr. Boehm noted. For one, previous studies have shown that the magnitude of blood pressure lowering continues to increase for up to 1-2 years following the procedure, whereas the off-medication assessment in SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED ended at 3 months for ethical and safety reasons. Also, 17% of patients in the control arm were withdrawn from the study and placed on antihypertensive medication because their office SBP reached 180 mm Hg or more, as compared to 9.6% of the RDN group.

A key finding was that RDN lowered blood pressure around the clock, including nighttime and early morning, the hours of greatest cardiovascular risk and a time when some antihypertensive medications are less effective at blood pressure control, the cardiologist observed.

The RDN safety picture was reassuring, with no strokes, myocardial infarctions, major bleeding, or acute deterioration in kidney function.

A surprising finding was that, even though participants underwent blood and urine testing for the presence of antihypertensive drugs at baseline to ensure they were off medication, and were told they would be retested at 3 months, 5%-9% nonetheless tested positive at the second test.

That elicited a comment from session chair Richard A. Chazal, MD, of Fort Myers, Fla.: “I must say, as a clinician who sometimes has trouble getting his patients to take antihypertensives, it’s fascinating that some of the people that you asked not to take the medications were taking them.”

While the primary outcome in SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED was the 3-month reduction in blood pressure while off of antihypertensive medication, the ongoing second phase of the trial may have greater clinical relevance. At 3 months, participants are being placed on antihypertensive medication and uptitrated to target, with unblinding at 6 months. The purpose is to see how many RDN recipients don’t need antihypertensive drugs, as well as whether those that do require less medication than the patients who didn’t undergo RDN.

Dr. Boehm characterized RDN as a work in progress. Two major limitations that are the focus of intense research are the lack of a predictor as to which patients are most likely to respond to what is after all an invasive procedure, and the current inability intraprocedurally to tell if sufficient RDN has been achieved.

“Frankly speaking, there is no technology during the procedure to see how efficacious the procedure was,” he explained.

Discussant Dhanunaja Lakkireddy, MD, deemed the mean 4.7–mm Hg reduction in 24-hour SBP “reasonably impressive – that’s actually a pretty good number for an antihypertensive clinical trial.” He was also favorably impressed by RDN’s safety in a 44-site study.

“The drops in blood pressure are not enough to really make a case for renal denervation to be a standalone therapy. But adding it as an adjunct to standard medications may be a very reasonable strategy to adopt. This is a fantastic signal for something that can be brought along as a long-term add-on to antihypertensive medications,” commented Dr. Lakkireddy, chair of the ACC Electrophysiology Council and medical director of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute.

Simultaneous with Dr. Boehm’s presentation, the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal Trial details were published online (Lancet 2020 Mar 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30554-7).

The study was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Boehm reported serving as a consultant to that company and Abbott, Amgen, Astra, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Novartis, ReCor, Servier, and Vifor.

SOURCE: Boehm M. ACC 2020, Abstract 406-15.

REPORTING FROM ACC 20

Primordial cardiovascular prevention draws closer

A powerful genetic predisposition to cardiovascular disease was overcome by low lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure in a naturalistic study conducted in nearly half a million people, Brian A. Ference, MD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This novel finding potentially opens the door to primordial cardiovascular prevention, the earliest possible form of primary prevention, in which cardiovascular risk factors are curtailed before they can become established.

“It’s important to note that the trajectories of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease predicted by a PGS [polygenic risk score] are not fixed. At the same level of a PGS for coronary artery disease, participants with lower lifetime exposure to LDL and systolic blood pressure had a lower trajectory of risk for cardiovascular disease. This finding implies that the trajectory of cardiovascular risk predicted by a PGS can be reduced by lowering LDL and blood pressure,” observed Dr. Ference, professor of translational therapeutics and executive director of the Center for Naturally Randomised Trials at the University of Cambridge (England).

Together with an international team of coinvestigators, he analyzed lifetime cardiovascular risk as predicted by a PGS derived by genomic testing in relation to lifetime LDL and systolic blood pressure levels in 445,566 participants in the UK Biobank. Subjects had a mean age of 57.2 years at enrollment and 65.2 years at last follow-up. The primary study outcome, a first major coronary event (MCE) as defined by a fatal or nonfatal MI or coronary revascularization, occurred in 23,032 subjects.

The investigators found a stepwise increase in MCE risk across increasing quintiles of genetic risk as reflected in the PGS, such that participants in the top PGS quintile were at 2.8-fold greater risk of an MCE than those in the first quintile. The risk was essentially the same in men and women.

A key finding was that, at any level of lifetime MCE risk as defined by PGS, the actual event rate varied 10-fold depending upon lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure (SBP). For example, men in the top PGS quintile with high lifetime SBP and LDL cholesterol had a 93% lifetime MCE risk, but that MCE risk plummeted to 8% in those in the top quintile but with low lifetime SBP and LDL cholesterol.

Small differences in those two cardiovascular risk factors over the course of many decades had a big impact. For example, it took only a 10-mg/dL lower lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and a 2–mm Hg lower SBP to blunt the trajectory of lifetime risk for MCE in individuals in the middle quintile of PGS to the more favorable trajectory of those in the lowest PGS quintile. Conversely, with a 10-mg/dL increase in LDL cholesterol and 2–mm Hg greater SBP over the course of a lifetime, the trajectory of risk for people in the middle quintile of PGS became essentially superimposable upon the trajectory associated with the highest PGS quintile, the cardiologist explained.

“Participants with low lifetime exposure to LDL and blood pressure had a low lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease at all levels of PGS for coronary disease. This implies that LDL and blood pressure, which are modifiable, may be more powerful determinants of lifetime risk than polygenic predisposition,” Dr. Ference declared.

Discussant Vera Bittner, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said that for her this study carried a heartening take-home message: “The polygenic risk score can stratify the population into different risk groups and, at the same time, lifetime exposure to LDL and blood pressure significantly modifies the risk, suggesting that genetics is not destiny, and we may be able to intervene.”

“To be able to know what your cardiovascular risk is from an early age and to plan therapies to prevent cardiovascular disease would be incredible,” agreed session chair B. Hadley Wilson, MD, of the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

Sekar Kathiresan, MD, said the study introduces the PGS as a new risk factor for coronary artery disease. Focusing efforts to achieve lifelong low exposure to LDL cholesterol and blood pressure in those individuals in the top 10%-20% in PGS should provide a great absolute reduction in MCE risk.

“It potentially can give you a 30- or 40-year head start in understanding who’s at risk because the factor can be measured as early as birth,” observed Dr. Kathiresan, a cardiologist who is director of the Center for Genomic Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“It’s also very inexpensive: You get the information once, bank it, and use it throughout life,” noted Paul M. Ridker, MD, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“A genome-wide scan will give us information not just on cardiovascular risk, but on cancer risk, on risk of kidney disease, and on the risk of a host of other issues. It’s a very different way of thinking about risk presentation across a whole variety of endpoints,” Dr. Ridker added.

Dr. Ference reported receiving fees and/or research grants from Merck, Amgen, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novartis, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, NovoNordisk, The Medicines Company, Mylan, Daiichi Sankyo, Silence Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, dalCOR, CiVi Pharma, KrKa Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, and Celera.

A powerful genetic predisposition to cardiovascular disease was overcome by low lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure in a naturalistic study conducted in nearly half a million people, Brian A. Ference, MD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This novel finding potentially opens the door to primordial cardiovascular prevention, the earliest possible form of primary prevention, in which cardiovascular risk factors are curtailed before they can become established.

“It’s important to note that the trajectories of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease predicted by a PGS [polygenic risk score] are not fixed. At the same level of a PGS for coronary artery disease, participants with lower lifetime exposure to LDL and systolic blood pressure had a lower trajectory of risk for cardiovascular disease. This finding implies that the trajectory of cardiovascular risk predicted by a PGS can be reduced by lowering LDL and blood pressure,” observed Dr. Ference, professor of translational therapeutics and executive director of the Center for Naturally Randomised Trials at the University of Cambridge (England).

Together with an international team of coinvestigators, he analyzed lifetime cardiovascular risk as predicted by a PGS derived by genomic testing in relation to lifetime LDL and systolic blood pressure levels in 445,566 participants in the UK Biobank. Subjects had a mean age of 57.2 years at enrollment and 65.2 years at last follow-up. The primary study outcome, a first major coronary event (MCE) as defined by a fatal or nonfatal MI or coronary revascularization, occurred in 23,032 subjects.

The investigators found a stepwise increase in MCE risk across increasing quintiles of genetic risk as reflected in the PGS, such that participants in the top PGS quintile were at 2.8-fold greater risk of an MCE than those in the first quintile. The risk was essentially the same in men and women.

A key finding was that, at any level of lifetime MCE risk as defined by PGS, the actual event rate varied 10-fold depending upon lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure (SBP). For example, men in the top PGS quintile with high lifetime SBP and LDL cholesterol had a 93% lifetime MCE risk, but that MCE risk plummeted to 8% in those in the top quintile but with low lifetime SBP and LDL cholesterol.

Small differences in those two cardiovascular risk factors over the course of many decades had a big impact. For example, it took only a 10-mg/dL lower lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and a 2–mm Hg lower SBP to blunt the trajectory of lifetime risk for MCE in individuals in the middle quintile of PGS to the more favorable trajectory of those in the lowest PGS quintile. Conversely, with a 10-mg/dL increase in LDL cholesterol and 2–mm Hg greater SBP over the course of a lifetime, the trajectory of risk for people in the middle quintile of PGS became essentially superimposable upon the trajectory associated with the highest PGS quintile, the cardiologist explained.

“Participants with low lifetime exposure to LDL and blood pressure had a low lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease at all levels of PGS for coronary disease. This implies that LDL and blood pressure, which are modifiable, may be more powerful determinants of lifetime risk than polygenic predisposition,” Dr. Ference declared.

Discussant Vera Bittner, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said that for her this study carried a heartening take-home message: “The polygenic risk score can stratify the population into different risk groups and, at the same time, lifetime exposure to LDL and blood pressure significantly modifies the risk, suggesting that genetics is not destiny, and we may be able to intervene.”

“To be able to know what your cardiovascular risk is from an early age and to plan therapies to prevent cardiovascular disease would be incredible,” agreed session chair B. Hadley Wilson, MD, of the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

Sekar Kathiresan, MD, said the study introduces the PGS as a new risk factor for coronary artery disease. Focusing efforts to achieve lifelong low exposure to LDL cholesterol and blood pressure in those individuals in the top 10%-20% in PGS should provide a great absolute reduction in MCE risk.

“It potentially can give you a 30- or 40-year head start in understanding who’s at risk because the factor can be measured as early as birth,” observed Dr. Kathiresan, a cardiologist who is director of the Center for Genomic Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“It’s also very inexpensive: You get the information once, bank it, and use it throughout life,” noted Paul M. Ridker, MD, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“A genome-wide scan will give us information not just on cardiovascular risk, but on cancer risk, on risk of kidney disease, and on the risk of a host of other issues. It’s a very different way of thinking about risk presentation across a whole variety of endpoints,” Dr. Ridker added.

Dr. Ference reported receiving fees and/or research grants from Merck, Amgen, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novartis, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, NovoNordisk, The Medicines Company, Mylan, Daiichi Sankyo, Silence Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, dalCOR, CiVi Pharma, KrKa Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, and Celera.

A powerful genetic predisposition to cardiovascular disease was overcome by low lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure in a naturalistic study conducted in nearly half a million people, Brian A. Ference, MD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This novel finding potentially opens the door to primordial cardiovascular prevention, the earliest possible form of primary prevention, in which cardiovascular risk factors are curtailed before they can become established.

“It’s important to note that the trajectories of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease predicted by a PGS [polygenic risk score] are not fixed. At the same level of a PGS for coronary artery disease, participants with lower lifetime exposure to LDL and systolic blood pressure had a lower trajectory of risk for cardiovascular disease. This finding implies that the trajectory of cardiovascular risk predicted by a PGS can be reduced by lowering LDL and blood pressure,” observed Dr. Ference, professor of translational therapeutics and executive director of the Center for Naturally Randomised Trials at the University of Cambridge (England).

Together with an international team of coinvestigators, he analyzed lifetime cardiovascular risk as predicted by a PGS derived by genomic testing in relation to lifetime LDL and systolic blood pressure levels in 445,566 participants in the UK Biobank. Subjects had a mean age of 57.2 years at enrollment and 65.2 years at last follow-up. The primary study outcome, a first major coronary event (MCE) as defined by a fatal or nonfatal MI or coronary revascularization, occurred in 23,032 subjects.

The investigators found a stepwise increase in MCE risk across increasing quintiles of genetic risk as reflected in the PGS, such that participants in the top PGS quintile were at 2.8-fold greater risk of an MCE than those in the first quintile. The risk was essentially the same in men and women.

A key finding was that, at any level of lifetime MCE risk as defined by PGS, the actual event rate varied 10-fold depending upon lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure (SBP). For example, men in the top PGS quintile with high lifetime SBP and LDL cholesterol had a 93% lifetime MCE risk, but that MCE risk plummeted to 8% in those in the top quintile but with low lifetime SBP and LDL cholesterol.

Small differences in those two cardiovascular risk factors over the course of many decades had a big impact. For example, it took only a 10-mg/dL lower lifetime exposure to LDL cholesterol and a 2–mm Hg lower SBP to blunt the trajectory of lifetime risk for MCE in individuals in the middle quintile of PGS to the more favorable trajectory of those in the lowest PGS quintile. Conversely, with a 10-mg/dL increase in LDL cholesterol and 2–mm Hg greater SBP over the course of a lifetime, the trajectory of risk for people in the middle quintile of PGS became essentially superimposable upon the trajectory associated with the highest PGS quintile, the cardiologist explained.

“Participants with low lifetime exposure to LDL and blood pressure had a low lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease at all levels of PGS for coronary disease. This implies that LDL and blood pressure, which are modifiable, may be more powerful determinants of lifetime risk than polygenic predisposition,” Dr. Ference declared.

Discussant Vera Bittner, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said that for her this study carried a heartening take-home message: “The polygenic risk score can stratify the population into different risk groups and, at the same time, lifetime exposure to LDL and blood pressure significantly modifies the risk, suggesting that genetics is not destiny, and we may be able to intervene.”

“To be able to know what your cardiovascular risk is from an early age and to plan therapies to prevent cardiovascular disease would be incredible,” agreed session chair B. Hadley Wilson, MD, of the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

Sekar Kathiresan, MD, said the study introduces the PGS as a new risk factor for coronary artery disease. Focusing efforts to achieve lifelong low exposure to LDL cholesterol and blood pressure in those individuals in the top 10%-20% in PGS should provide a great absolute reduction in MCE risk.

“It potentially can give you a 30- or 40-year head start in understanding who’s at risk because the factor can be measured as early as birth,” observed Dr. Kathiresan, a cardiologist who is director of the Center for Genomic Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“It’s also very inexpensive: You get the information once, bank it, and use it throughout life,” noted Paul M. Ridker, MD, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“A genome-wide scan will give us information not just on cardiovascular risk, but on cancer risk, on risk of kidney disease, and on the risk of a host of other issues. It’s a very different way of thinking about risk presentation across a whole variety of endpoints,” Dr. Ridker added.

Dr. Ference reported receiving fees and/or research grants from Merck, Amgen, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novartis, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, NovoNordisk, The Medicines Company, Mylan, Daiichi Sankyo, Silence Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, dalCOR, CiVi Pharma, KrKa Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, and Celera.

REPORTING FROM ACC 20

Dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States

There has been a dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States between 2007 and 2017, a new study shows. The authors, led by Lakshmi Nambiar, MD, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which collates information from every death certificate in the country, amounting to more than 10 million deaths.

They found that age-adjusted hypertension-related deaths had increased from 18.3 per 100,000 in 2007 to 23.0 per 100,000 in 2017 (P < .001 for decade-long temporal trend).

Nambiar reported results of the study at an American College of Cardiology 2020/World Congress of Cardiology press conference on March 19. It was also published online on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

She noted that death rates due to cardiovascular disease have been falling over the past 20 years largely attributable to statins to treat high cholesterol and stents to treat coronary artery disease. But since 2011, the rate of decline in cardiovascular deaths has slowed. One contributing factor is an increase in heart failure-related deaths but there hasn’t been any data in recent years on hypertension-related deaths.

“Our data show an increase in hypertension-related deaths in all age groups, in all regions of the United States, and in both sexes. These findings are alarming and warrant further investigation, as well as preventative efforts,” Nambiar said. “This is a public health emergency that has not been fully recognized,” she added.

“We were surprised to see how dramatically these deaths were increasing, and we think this is related to the rise in diabetes, obesity, and the aging of the population. We need targeted public health measures to address some of those factors,” Nambiar told Medscape Medical News.

“We are winning the battle against coronary artery disease with statins and stents but we are not winning the battle against hypertension,” she added.

Worst Figures in Rural South

Results showed that hypertension-related deaths increased in both rural and urban regions, but the increase was much steeper in rural areas — a 72% increase over the decade compared with a 20% increase in urban areas.

The highest death risk was identified in the rural South, which demonstrated an age-adjusted 2.5-fold higher death rate compared with other regions (P < .001).

The urban South also demonstrated increasing hypertension-related cardiovascular death rates over time: age-adjusted death rates in the urban South increased by 27% compared with all other urban regions (P < .001).

But the absolute mortality rates and slope of the curves demonstrate the highest risk in patients in the rural South, the researchers report. Age-adjusted hypertension-related death rates increased in the rural South from 23.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2007 to 39.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

Nambiar said the trends in the rural South could be related to social factors and lack of access to healthcare in the area, which has been exacerbated by failure to adopt Medicaid expansion in many of the states in this region.

“When it comes to the management of hypertension you need to be seen regularly by a primary care doctor to get the best treatment and regular assessments,” she stressed.

Chair of the ACC press conference at which the data were presented, Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix, said: “In this day and time, there is less smoking, which should translate into lower rates of hypertension, but these trends reported here are very different from what we would expect and are probably associated with the rise in other risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, especially in the rural South.”

Nambiar praised the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines that recommend a lower diagnostic threshold, “so more people now fit the criteria for raised blood pressure and need treatment.”

“It is important for all primary care physicians and cardiologists to recognize the new threshold and treat people accordingly,” she said. “High blood pressure is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease. If we can control it better, we may be able to control some of this increased mortality we are seeing.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States between 2007 and 2017, a new study shows. The authors, led by Lakshmi Nambiar, MD, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which collates information from every death certificate in the country, amounting to more than 10 million deaths.

They found that age-adjusted hypertension-related deaths had increased from 18.3 per 100,000 in 2007 to 23.0 per 100,000 in 2017 (P < .001 for decade-long temporal trend).

Nambiar reported results of the study at an American College of Cardiology 2020/World Congress of Cardiology press conference on March 19. It was also published online on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

She noted that death rates due to cardiovascular disease have been falling over the past 20 years largely attributable to statins to treat high cholesterol and stents to treat coronary artery disease. But since 2011, the rate of decline in cardiovascular deaths has slowed. One contributing factor is an increase in heart failure-related deaths but there hasn’t been any data in recent years on hypertension-related deaths.

“Our data show an increase in hypertension-related deaths in all age groups, in all regions of the United States, and in both sexes. These findings are alarming and warrant further investigation, as well as preventative efforts,” Nambiar said. “This is a public health emergency that has not been fully recognized,” she added.

“We were surprised to see how dramatically these deaths were increasing, and we think this is related to the rise in diabetes, obesity, and the aging of the population. We need targeted public health measures to address some of those factors,” Nambiar told Medscape Medical News.

“We are winning the battle against coronary artery disease with statins and stents but we are not winning the battle against hypertension,” she added.

Worst Figures in Rural South

Results showed that hypertension-related deaths increased in both rural and urban regions, but the increase was much steeper in rural areas — a 72% increase over the decade compared with a 20% increase in urban areas.

The highest death risk was identified in the rural South, which demonstrated an age-adjusted 2.5-fold higher death rate compared with other regions (P < .001).

The urban South also demonstrated increasing hypertension-related cardiovascular death rates over time: age-adjusted death rates in the urban South increased by 27% compared with all other urban regions (P < .001).

But the absolute mortality rates and slope of the curves demonstrate the highest risk in patients in the rural South, the researchers report. Age-adjusted hypertension-related death rates increased in the rural South from 23.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2007 to 39.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

Nambiar said the trends in the rural South could be related to social factors and lack of access to healthcare in the area, which has been exacerbated by failure to adopt Medicaid expansion in many of the states in this region.

“When it comes to the management of hypertension you need to be seen regularly by a primary care doctor to get the best treatment and regular assessments,” she stressed.

Chair of the ACC press conference at which the data were presented, Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix, said: “In this day and time, there is less smoking, which should translate into lower rates of hypertension, but these trends reported here are very different from what we would expect and are probably associated with the rise in other risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, especially in the rural South.”

Nambiar praised the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines that recommend a lower diagnostic threshold, “so more people now fit the criteria for raised blood pressure and need treatment.”

“It is important for all primary care physicians and cardiologists to recognize the new threshold and treat people accordingly,” she said. “High blood pressure is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease. If we can control it better, we may be able to control some of this increased mortality we are seeing.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States between 2007 and 2017, a new study shows. The authors, led by Lakshmi Nambiar, MD, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which collates information from every death certificate in the country, amounting to more than 10 million deaths.

They found that age-adjusted hypertension-related deaths had increased from 18.3 per 100,000 in 2007 to 23.0 per 100,000 in 2017 (P < .001 for decade-long temporal trend).

Nambiar reported results of the study at an American College of Cardiology 2020/World Congress of Cardiology press conference on March 19. It was also published online on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

She noted that death rates due to cardiovascular disease have been falling over the past 20 years largely attributable to statins to treat high cholesterol and stents to treat coronary artery disease. But since 2011, the rate of decline in cardiovascular deaths has slowed. One contributing factor is an increase in heart failure-related deaths but there hasn’t been any data in recent years on hypertension-related deaths.

“Our data show an increase in hypertension-related deaths in all age groups, in all regions of the United States, and in both sexes. These findings are alarming and warrant further investigation, as well as preventative efforts,” Nambiar said. “This is a public health emergency that has not been fully recognized,” she added.

“We were surprised to see how dramatically these deaths were increasing, and we think this is related to the rise in diabetes, obesity, and the aging of the population. We need targeted public health measures to address some of those factors,” Nambiar told Medscape Medical News.

“We are winning the battle against coronary artery disease with statins and stents but we are not winning the battle against hypertension,” she added.

Worst Figures in Rural South

Results showed that hypertension-related deaths increased in both rural and urban regions, but the increase was much steeper in rural areas — a 72% increase over the decade compared with a 20% increase in urban areas.

The highest death risk was identified in the rural South, which demonstrated an age-adjusted 2.5-fold higher death rate compared with other regions (P < .001).

The urban South also demonstrated increasing hypertension-related cardiovascular death rates over time: age-adjusted death rates in the urban South increased by 27% compared with all other urban regions (P < .001).

But the absolute mortality rates and slope of the curves demonstrate the highest risk in patients in the rural South, the researchers report. Age-adjusted hypertension-related death rates increased in the rural South from 23.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2007 to 39.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

Nambiar said the trends in the rural South could be related to social factors and lack of access to healthcare in the area, which has been exacerbated by failure to adopt Medicaid expansion in many of the states in this region.

“When it comes to the management of hypertension you need to be seen regularly by a primary care doctor to get the best treatment and regular assessments,” she stressed.

Chair of the ACC press conference at which the data were presented, Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix, said: “In this day and time, there is less smoking, which should translate into lower rates of hypertension, but these trends reported here are very different from what we would expect and are probably associated with the rise in other risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, especially in the rural South.”

Nambiar praised the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines that recommend a lower diagnostic threshold, “so more people now fit the criteria for raised blood pressure and need treatment.”

“It is important for all primary care physicians and cardiologists to recognize the new threshold and treat people accordingly,” she said. “High blood pressure is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease. If we can control it better, we may be able to control some of this increased mortality we are seeing.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular risk varies between black ethnic subgroups

PHOENIX, ARIZ. – Cardiovascular disease risk factors differ significantly between three black ethnic subgroups in the United States, compared with whites, results from a large, long-term cross-sectional study show.

“Race alone does not account for health disparities in CVD risk factors,” lead author Diana Baptiste, DNP, RN, CNE, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting. “We must consider the environmental, psychosocial, and social factors that may play a larger role in CVD risk among these populations.”

Dr. Baptiste, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing Center for Cardiovascular and Chronic Care in Baltimore, noted that blacks bear a disproportionately greater burden of CVD than that of any other racial group. “Blacks living in the U.S. are not monolithic and include different ethnic subgroups: African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, defined as black persons who are born in the Caribbean islands, and African immigrants, defined as black persons who are born in Africa,” she said. “It is unclear how Afro-Caribbeans and African immigrants compare to African Americans and whites with regard to CVD risk factors.”

To examine trends in CVD risk factors among the three black ethnic subgroups compared with whites, she and her colleagues performed a cross-sectional analysis of 452,997 adults who participated in the 2010-2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Of these, 82% were white and 18% were black. Among blacks, 89% were African Americans, 6% were Afro-Caribbeans, and 5% were African immigrants. Outcomes of interest were four self-reported CVD risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, overweight/obesity, and smoking. The researchers used generalized linear models with Poisson distribution to calculate predictive probabilities of CVD risk factors, adjusted for age and sex.

Dr. Baptiste reported that African immigrants represented the youngest subgroup, with an average age of 41 years, compared with an average age of 50 among whites. They were also less likely to have health insurance (76%), compared with Afro-Caribbeans (81%), African Americans (83%), and whites (91%; P < .001). Disparities were observed in the proportion of individuals living below the poverty level. This was led by African Americans (24%), followed by African immigrants (22%), Afro-Caribbeans (18%), and whites (9%).

African immigrants were most likely to be college educated (36%), compared with whites (32%), Afro-Caribbeans (23%), and African Americans (17%; P =.001). In addition, only 33% of African Americans were married, compared with more than 50% of participants in the other ethnic groups.

African Americans had the highest prevalence of hypertension over the time period (from 44% in 2010 to 42% in 2018), while African immigrants had the lowest (from 19% to 17%). African Americans also had the highest prevalence of diabetes over the time period (from 14% to 15%), while African immigrants had the lowest (from 9% to 7%). The prevalence of overweight and obesity was highest among African Americans (from 74% to 76%), while African immigrants had the lowest (63% to 60%). Finally, smoking prevalence was highest in whites and African Americans compared with African immigrants and Afro-Caribbeans, but the prevalence decreased significantly between 2010 and 2018 (P for trend < .001).

In an interview, one of the meeting session’s moderators, Sherry-Ann Brown, MD, PhD, said that the study’s findings underscore the importance of heterogeneity when counseling patients about CVD risk factors. “Everybody comes from a different cultural background,” said Dr. Brown, a cardiologist and physician scientist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “Cultural backgrounds have an impact on when people eat, how they eat, who they eat with, when they exercise, and whether obesity is valued or not. It’s important to recognize that those cultural underpinnings can contribute to heterogeneity. Other factors – whether they are psychosocial or socioeconomic or environmental – also contribute.”

Strengths of the study, Dr. Baptiste said, included the use of a large, nationally representative dataset. Limitations included its cross-sectional design and the National Health Interview Survey’s reliance on self-reported data. “There were also small sample sizes for African immigrants and Afro-Caribbeans,” she said.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing Center for Cardiovascular and Chronic Care. Dr. Baptiste reported having no financial disclosures.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

SOURCE: Baptiste D et al. EPI/Lifestyle 2020, Session 4, Abstract 8.

PHOENIX, ARIZ. – Cardiovascular disease risk factors differ significantly between three black ethnic subgroups in the United States, compared with whites, results from a large, long-term cross-sectional study show.

“Race alone does not account for health disparities in CVD risk factors,” lead author Diana Baptiste, DNP, RN, CNE, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting. “We must consider the environmental, psychosocial, and social factors that may play a larger role in CVD risk among these populations.”

Dr. Baptiste, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing Center for Cardiovascular and Chronic Care in Baltimore, noted that blacks bear a disproportionately greater burden of CVD than that of any other racial group. “Blacks living in the U.S. are not monolithic and include different ethnic subgroups: African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, defined as black persons who are born in the Caribbean islands, and African immigrants, defined as black persons who are born in Africa,” she said. “It is unclear how Afro-Caribbeans and African immigrants compare to African Americans and whites with regard to CVD risk factors.”

To examine trends in CVD risk factors among the three black ethnic subgroups compared with whites, she and her colleagues performed a cross-sectional analysis of 452,997 adults who participated in the 2010-2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Of these, 82% were white and 18% were black. Among blacks, 89% were African Americans, 6% were Afro-Caribbeans, and 5% were African immigrants. Outcomes of interest were four self-reported CVD risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, overweight/obesity, and smoking. The researchers used generalized linear models with Poisson distribution to calculate predictive probabilities of CVD risk factors, adjusted for age and sex.

Dr. Baptiste reported that African immigrants represented the youngest subgroup, with an average age of 41 years, compared with an average age of 50 among whites. They were also less likely to have health insurance (76%), compared with Afro-Caribbeans (81%), African Americans (83%), and whites (91%; P < .001). Disparities were observed in the proportion of individuals living below the poverty level. This was led by African Americans (24%), followed by African immigrants (22%), Afro-Caribbeans (18%), and whites (9%).

African immigrants were most likely to be college educated (36%), compared with whites (32%), Afro-Caribbeans (23%), and African Americans (17%; P =.001). In addition, only 33% of African Americans were married, compared with more than 50% of participants in the other ethnic groups.

African Americans had the highest prevalence of hypertension over the time period (from 44% in 2010 to 42% in 2018), while African immigrants had the lowest (from 19% to 17%). African Americans also had the highest prevalence of diabetes over the time period (from 14% to 15%), while African immigrants had the lowest (from 9% to 7%). The prevalence of overweight and obesity was highest among African Americans (from 74% to 76%), while African immigrants had the lowest (63% to 60%). Finally, smoking prevalence was highest in whites and African Americans compared with African immigrants and Afro-Caribbeans, but the prevalence decreased significantly between 2010 and 2018 (P for trend < .001).

In an interview, one of the meeting session’s moderators, Sherry-Ann Brown, MD, PhD, said that the study’s findings underscore the importance of heterogeneity when counseling patients about CVD risk factors. “Everybody comes from a different cultural background,” said Dr. Brown, a cardiologist and physician scientist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “Cultural backgrounds have an impact on when people eat, how they eat, who they eat with, when they exercise, and whether obesity is valued or not. It’s important to recognize that those cultural underpinnings can contribute to heterogeneity. Other factors – whether they are psychosocial or socioeconomic or environmental – also contribute.”

Strengths of the study, Dr. Baptiste said, included the use of a large, nationally representative dataset. Limitations included its cross-sectional design and the National Health Interview Survey’s reliance on self-reported data. “There were also small sample sizes for African immigrants and Afro-Caribbeans,” she said.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing Center for Cardiovascular and Chronic Care. Dr. Baptiste reported having no financial disclosures.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

SOURCE: Baptiste D et al. EPI/Lifestyle 2020, Session 4, Abstract 8.

PHOENIX, ARIZ. – Cardiovascular disease risk factors differ significantly between three black ethnic subgroups in the United States, compared with whites, results from a large, long-term cross-sectional study show.

“Race alone does not account for health disparities in CVD risk factors,” lead author Diana Baptiste, DNP, RN, CNE, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting. “We must consider the environmental, psychosocial, and social factors that may play a larger role in CVD risk among these populations.”