User login

ESC says continue hypertension meds despite COVID-19 concern

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CV health in pregnancy improves outcomes for mother and infant

PHOENIX – according to results from a multinational cohort study.

“Over the past 10 years, cardiovascular health [CVH] has been characterized across most of the life course and is associated with a variety of health outcomes, but CVH as a whole has not been well studied during pregnancy,” Amanda M. Perak, MD, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting.

In an effort to examine the associations of maternal gestational CVH with adverse maternal and newborn outcomes, Dr. Perak of the departments of pediatrics and preventive medicine at Northwestern University and Lurie Children’s Hospital, both in Chicago, and colleagues drew from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study, which examined pregnant women at a target of 28 weeks’ gestation and assessed the associations of glycemia with pregnancy outcomes. The researchers analyzed data from an ancillary study of 2,230 mother-child dyads to characterize clinical gestational CVH with use of five metrics: body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and smoking. The study excluded women with prepregnancy diabetes, preterm births, and cases of fetal death/major malformations.

Each maternal CVH metric was classified as ideal, intermediate, or poor according to modified definitions based on pregnancy guidelines. “For lipids, it’s known that levels change substantially during pregnancy, but there are no pregnancy guidelines,” Dr. Perak said. “We and others have also shown that higher triglycerides in pregnancy are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. We selected thresholds of less than 250 mg/dL for ideal and at least 500 mg/dL for poor, based on triglyceride distribution and clinical relevance.”

Total CVH was scored by assigning 2 points for ideal, 1 for intermediate, and 0 for each poor metric, for a total possible 10 points, with 10 being most favorable. They also created four CVH categories, ranging from all ideal to two or more poor metrics. Maternal adverse pregnancy outcomes included preeclampsia and unplanned primary cesarean section. Newborn adverse pregnancy outcomes included birth weight above the 90th percentile and a cord blood insulin sensitivity index lower than the 10th percentile.

The researchers used logistic and multinomial logistic regression of pregnancy outcomes on maternal gestational CVH in two adjusted models. Secondarily, they examined associations of individual CVH metrics with outcomes, with adjustment for the other metrics.

The cohort comprised mother-child dyads from nine field centers in six countries: the United States (25%), Barbados (23%), United Kingdom (21%), China (18%), Thailand (7%), and Canada (7%). The mothers’ mean age was 30 years, and the mean gestational age was 28 weeks. The mean gestational CVH score was 8.8 out of 10. Nearly half of mothers (42%) had ideal metrics, while 4% had two or more poor metrics. Delivery occurred at a mean of 39.8 weeks, and adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in 4.7%-17.9% of pregnancies.

In the fully adjusted model, which accounted for maternal age, height, alcohol use, gestational age at pregnancy exam, maternal parity, and newborn sex and race/ethnicity, odds ratios per 1-point higher (better) CVH score were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.70) for preeclampsia, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.76-0.95) for unplanned primary cesarean section (among primiparous mothers), 0.83 (95% CI, 0.77-0.91) for large for gestational age infant, and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.72-0.87) for infant insulin sensitivity index below the 10th percentile. CVH categories were also associated with outcomes. For example, odds ratios for preeclampsia were 4.61 (95% CI, 2.13-11.14) for mothers with one or more intermediate metrics, 7.62 (95% CI, 3.60-18.13) for mothers with one poor metric, and 12.02 (95% CI, 4.70-32.50) for mothers with two or more poor metrics, compared with mothers with all metrics ideal.

“Except for smoking, each CVH metric was independently associated with adverse outcomes,” Dr. Perak said. “However, total CVH was associated with a wider range of outcomes than any single metric. This suggests that CVH provides health insights beyond single risk factors.”

Strengths of the study, she continued, included geographic and racial diversity of participants and high-quality research measurements of CVH. Limitations were that the cohort excluded prepregnancy diabetes and preterm births. “Diet and exercise data were not available, and CVH was measured once at 28 weeks,” she said. “Further study is needed across pregnancy and in other settings, but this study provides the first data on the relevance of gestational CVH for pregnancy outcomes.”

In an interview, Stephen S. Rich, PhD, who directs the Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia, said that the data “provide strong epidemiologic support to focus on the full range of cardiovascular health. In my view, the primary limitation of the study is that there may be significant differences in how one achieves ideal CHV across a single country, not to mention across the world, particularly in absence of a highly controlled, research environment. It is not clear that the approach used in this study at nine selected sites in six relatively highly developed countries could be translated into primary care – particularly in the U.S. with different regulatory and reimbursement plans and payers. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests a way to reduce adverse outcomes in pregnancy and the area deserves greater research.”

According to Dr. Perak, gestational diabetes is associated with a twofold higher maternal risk for cardiovascular disease (Diabetologia. 2019;62:905-14), while diabetes is also associated with higher offspring risk for CVD (BMJ. 2019;367:16398). However, a paucity of data exists on gestational CVH. In one report, better gestational CVH was associated with less subclinical CVD for the mother 10 years later (J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Jul 23. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.011394). In a separate analysis, Dr. Perak and her colleagues found that better gestational CVH was associated with better offspring CVH in childhood. “Unfortunately, we also reported that, among pregnant women in the United States, fewer than 1 in 10 had high CVH,” she said (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Feb 17. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.015123). “However, the relevance of gestational CVH for pregnancy outcomes is unknown, but a it’s key question when considering CVH monitoring in prenatal care.”

Dr. Perak reported having received grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, and Northwestern University. The HAPO Study was supported by NHLBI and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

SOURCE: Perak A et al. Epi/Lifestyle 2020, Abstract 33.

PHOENIX – according to results from a multinational cohort study.

“Over the past 10 years, cardiovascular health [CVH] has been characterized across most of the life course and is associated with a variety of health outcomes, but CVH as a whole has not been well studied during pregnancy,” Amanda M. Perak, MD, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting.

In an effort to examine the associations of maternal gestational CVH with adverse maternal and newborn outcomes, Dr. Perak of the departments of pediatrics and preventive medicine at Northwestern University and Lurie Children’s Hospital, both in Chicago, and colleagues drew from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study, which examined pregnant women at a target of 28 weeks’ gestation and assessed the associations of glycemia with pregnancy outcomes. The researchers analyzed data from an ancillary study of 2,230 mother-child dyads to characterize clinical gestational CVH with use of five metrics: body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and smoking. The study excluded women with prepregnancy diabetes, preterm births, and cases of fetal death/major malformations.

Each maternal CVH metric was classified as ideal, intermediate, or poor according to modified definitions based on pregnancy guidelines. “For lipids, it’s known that levels change substantially during pregnancy, but there are no pregnancy guidelines,” Dr. Perak said. “We and others have also shown that higher triglycerides in pregnancy are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. We selected thresholds of less than 250 mg/dL for ideal and at least 500 mg/dL for poor, based on triglyceride distribution and clinical relevance.”

Total CVH was scored by assigning 2 points for ideal, 1 for intermediate, and 0 for each poor metric, for a total possible 10 points, with 10 being most favorable. They also created four CVH categories, ranging from all ideal to two or more poor metrics. Maternal adverse pregnancy outcomes included preeclampsia and unplanned primary cesarean section. Newborn adverse pregnancy outcomes included birth weight above the 90th percentile and a cord blood insulin sensitivity index lower than the 10th percentile.

The researchers used logistic and multinomial logistic regression of pregnancy outcomes on maternal gestational CVH in two adjusted models. Secondarily, they examined associations of individual CVH metrics with outcomes, with adjustment for the other metrics.

The cohort comprised mother-child dyads from nine field centers in six countries: the United States (25%), Barbados (23%), United Kingdom (21%), China (18%), Thailand (7%), and Canada (7%). The mothers’ mean age was 30 years, and the mean gestational age was 28 weeks. The mean gestational CVH score was 8.8 out of 10. Nearly half of mothers (42%) had ideal metrics, while 4% had two or more poor metrics. Delivery occurred at a mean of 39.8 weeks, and adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in 4.7%-17.9% of pregnancies.

In the fully adjusted model, which accounted for maternal age, height, alcohol use, gestational age at pregnancy exam, maternal parity, and newborn sex and race/ethnicity, odds ratios per 1-point higher (better) CVH score were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.70) for preeclampsia, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.76-0.95) for unplanned primary cesarean section (among primiparous mothers), 0.83 (95% CI, 0.77-0.91) for large for gestational age infant, and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.72-0.87) for infant insulin sensitivity index below the 10th percentile. CVH categories were also associated with outcomes. For example, odds ratios for preeclampsia were 4.61 (95% CI, 2.13-11.14) for mothers with one or more intermediate metrics, 7.62 (95% CI, 3.60-18.13) for mothers with one poor metric, and 12.02 (95% CI, 4.70-32.50) for mothers with two or more poor metrics, compared with mothers with all metrics ideal.

“Except for smoking, each CVH metric was independently associated with adverse outcomes,” Dr. Perak said. “However, total CVH was associated with a wider range of outcomes than any single metric. This suggests that CVH provides health insights beyond single risk factors.”

Strengths of the study, she continued, included geographic and racial diversity of participants and high-quality research measurements of CVH. Limitations were that the cohort excluded prepregnancy diabetes and preterm births. “Diet and exercise data were not available, and CVH was measured once at 28 weeks,” she said. “Further study is needed across pregnancy and in other settings, but this study provides the first data on the relevance of gestational CVH for pregnancy outcomes.”

In an interview, Stephen S. Rich, PhD, who directs the Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia, said that the data “provide strong epidemiologic support to focus on the full range of cardiovascular health. In my view, the primary limitation of the study is that there may be significant differences in how one achieves ideal CHV across a single country, not to mention across the world, particularly in absence of a highly controlled, research environment. It is not clear that the approach used in this study at nine selected sites in six relatively highly developed countries could be translated into primary care – particularly in the U.S. with different regulatory and reimbursement plans and payers. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests a way to reduce adverse outcomes in pregnancy and the area deserves greater research.”

According to Dr. Perak, gestational diabetes is associated with a twofold higher maternal risk for cardiovascular disease (Diabetologia. 2019;62:905-14), while diabetes is also associated with higher offspring risk for CVD (BMJ. 2019;367:16398). However, a paucity of data exists on gestational CVH. In one report, better gestational CVH was associated with less subclinical CVD for the mother 10 years later (J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Jul 23. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.011394). In a separate analysis, Dr. Perak and her colleagues found that better gestational CVH was associated with better offspring CVH in childhood. “Unfortunately, we also reported that, among pregnant women in the United States, fewer than 1 in 10 had high CVH,” she said (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Feb 17. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.015123). “However, the relevance of gestational CVH for pregnancy outcomes is unknown, but a it’s key question when considering CVH monitoring in prenatal care.”

Dr. Perak reported having received grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, and Northwestern University. The HAPO Study was supported by NHLBI and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

SOURCE: Perak A et al. Epi/Lifestyle 2020, Abstract 33.

PHOENIX – according to results from a multinational cohort study.

“Over the past 10 years, cardiovascular health [CVH] has been characterized across most of the life course and is associated with a variety of health outcomes, but CVH as a whole has not been well studied during pregnancy,” Amanda M. Perak, MD, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting.

In an effort to examine the associations of maternal gestational CVH with adverse maternal and newborn outcomes, Dr. Perak of the departments of pediatrics and preventive medicine at Northwestern University and Lurie Children’s Hospital, both in Chicago, and colleagues drew from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study, which examined pregnant women at a target of 28 weeks’ gestation and assessed the associations of glycemia with pregnancy outcomes. The researchers analyzed data from an ancillary study of 2,230 mother-child dyads to characterize clinical gestational CVH with use of five metrics: body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and smoking. The study excluded women with prepregnancy diabetes, preterm births, and cases of fetal death/major malformations.

Each maternal CVH metric was classified as ideal, intermediate, or poor according to modified definitions based on pregnancy guidelines. “For lipids, it’s known that levels change substantially during pregnancy, but there are no pregnancy guidelines,” Dr. Perak said. “We and others have also shown that higher triglycerides in pregnancy are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. We selected thresholds of less than 250 mg/dL for ideal and at least 500 mg/dL for poor, based on triglyceride distribution and clinical relevance.”

Total CVH was scored by assigning 2 points for ideal, 1 for intermediate, and 0 for each poor metric, for a total possible 10 points, with 10 being most favorable. They also created four CVH categories, ranging from all ideal to two or more poor metrics. Maternal adverse pregnancy outcomes included preeclampsia and unplanned primary cesarean section. Newborn adverse pregnancy outcomes included birth weight above the 90th percentile and a cord blood insulin sensitivity index lower than the 10th percentile.

The researchers used logistic and multinomial logistic regression of pregnancy outcomes on maternal gestational CVH in two adjusted models. Secondarily, they examined associations of individual CVH metrics with outcomes, with adjustment for the other metrics.

The cohort comprised mother-child dyads from nine field centers in six countries: the United States (25%), Barbados (23%), United Kingdom (21%), China (18%), Thailand (7%), and Canada (7%). The mothers’ mean age was 30 years, and the mean gestational age was 28 weeks. The mean gestational CVH score was 8.8 out of 10. Nearly half of mothers (42%) had ideal metrics, while 4% had two or more poor metrics. Delivery occurred at a mean of 39.8 weeks, and adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in 4.7%-17.9% of pregnancies.

In the fully adjusted model, which accounted for maternal age, height, alcohol use, gestational age at pregnancy exam, maternal parity, and newborn sex and race/ethnicity, odds ratios per 1-point higher (better) CVH score were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.70) for preeclampsia, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.76-0.95) for unplanned primary cesarean section (among primiparous mothers), 0.83 (95% CI, 0.77-0.91) for large for gestational age infant, and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.72-0.87) for infant insulin sensitivity index below the 10th percentile. CVH categories were also associated with outcomes. For example, odds ratios for preeclampsia were 4.61 (95% CI, 2.13-11.14) for mothers with one or more intermediate metrics, 7.62 (95% CI, 3.60-18.13) for mothers with one poor metric, and 12.02 (95% CI, 4.70-32.50) for mothers with two or more poor metrics, compared with mothers with all metrics ideal.

“Except for smoking, each CVH metric was independently associated with adverse outcomes,” Dr. Perak said. “However, total CVH was associated with a wider range of outcomes than any single metric. This suggests that CVH provides health insights beyond single risk factors.”

Strengths of the study, she continued, included geographic and racial diversity of participants and high-quality research measurements of CVH. Limitations were that the cohort excluded prepregnancy diabetes and preterm births. “Diet and exercise data were not available, and CVH was measured once at 28 weeks,” she said. “Further study is needed across pregnancy and in other settings, but this study provides the first data on the relevance of gestational CVH for pregnancy outcomes.”

In an interview, Stephen S. Rich, PhD, who directs the Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia, said that the data “provide strong epidemiologic support to focus on the full range of cardiovascular health. In my view, the primary limitation of the study is that there may be significant differences in how one achieves ideal CHV across a single country, not to mention across the world, particularly in absence of a highly controlled, research environment. It is not clear that the approach used in this study at nine selected sites in six relatively highly developed countries could be translated into primary care – particularly in the U.S. with different regulatory and reimbursement plans and payers. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests a way to reduce adverse outcomes in pregnancy and the area deserves greater research.”

According to Dr. Perak, gestational diabetes is associated with a twofold higher maternal risk for cardiovascular disease (Diabetologia. 2019;62:905-14), while diabetes is also associated with higher offspring risk for CVD (BMJ. 2019;367:16398). However, a paucity of data exists on gestational CVH. In one report, better gestational CVH was associated with less subclinical CVD for the mother 10 years later (J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Jul 23. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.011394). In a separate analysis, Dr. Perak and her colleagues found that better gestational CVH was associated with better offspring CVH in childhood. “Unfortunately, we also reported that, among pregnant women in the United States, fewer than 1 in 10 had high CVH,” she said (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Feb 17. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.015123). “However, the relevance of gestational CVH for pregnancy outcomes is unknown, but a it’s key question when considering CVH monitoring in prenatal care.”

Dr. Perak reported having received grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, and Northwestern University. The HAPO Study was supported by NHLBI and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

SOURCE: Perak A et al. Epi/Lifestyle 2020, Abstract 33.

REPORTING FROM EPI/LIFESTYLE 2020

Risk factors for death from COVID-19 identified in Wuhan patients

Patients who did not survive hospitalization for COVID-19 in Wuhan were more likely to be older, have comorbidities, and elevated D-dimer, according to the first study to examine risk factors associated with death among adults hospitalized with COVID-19. “Older age, showing signs of sepsis on admission, underlying diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes, and the prolonged use of noninvasive ventilation were important factors in the deaths of these patients,” coauthor Zhibo Liu said in a news release. Abnormal blood clotting was part of the clinical picture too.

Fei Zhou, MD, from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and colleagues conducted a retrospective, observational, multicenter cohort study of 191 patients, 137 of whom were discharged and 54 of whom died in the hospital.

The study, published online today in The Lancet, included all adult inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from Jinyintan Hospital and Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital who had been discharged or died by January 31 of this year. Severely ill patients in the province were transferred to these hospitals until February 1.

The researchers compared demographic, clinical, treatment, and laboratory data from electronic medical records between survivors and those who succumbed to the disease. The analysis also tested serial samples for viral RNA. Overall, 91 (48%) of the 191 patients had comorbidity. Most common was hypertension (30%), followed by diabetes (19%) and coronary heart disease (8%).

The odds of dying in the hospital increased with age (odds ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.17; per year increase in age), higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (5.65, 2.61-12.23; P < .0001), and D-dimer level exceeding 1 mcg/L on admission. The SOFA was previously called the “sepsis-related organ failure assessment score” and assesses rate of organ failure in intensive care units. Elevated D-dimer indicates increased risk of abnormal blood clotting, such as deep vein thrombosis.

Nonsurvivors compared with survivors had higher frequencies of respiratory failure (98% vs 36%), sepsis (100%, vs 42%), and secondary infections (50% vs 1%).

The average age of survivors was 52 years compared to 69 for those who died. Liu cited weakening of the immune system and increased inflammation, which damages organs and also promotes viral replication, as explanations for the age effect.

From the time of initial symptoms, median time to discharge from the hospital was 22 days. Average time to death was 18.5 days.

Fever persisted for a median of 12 days among all patients, and cough persisted for a median 19 days; 45% of the survivors were still coughing on discharge. In survivors, shortness of breath improved after 13 days, but persisted until death in the others.

Viral shedding persisted for a median duration of 20 days in survivors, ranging from 8 to 37. The virus (SARS-CoV-2) was detectable in nonsurvivors until death. Antiviral treatment did not curtail viral shedding.

But the viral shedding data come with a caveat. “The extended viral shedding noted in our study has important implications for guiding decisions around isolation precautions and antiviral treatment in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. However, we need to be clear that viral shedding time should not be confused with other self-isolation guidance for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19 but do not have symptoms, as this guidance is based on the incubation time of the virus,” explained colead author Bin Cao.

“Older age, elevated D-dimer levels, and high SOFA score could help clinicians to identify at an early stage those patients with COVID-19 who have poor prognosis. Prolonged viral shedding provides the rationale for a strategy of isolation of infected patients and optimal antiviral interventions in the future,” the researchers conclude.

A limitation in interpreting the findings of the study is that hospitalized patients do not represent the entire infected population. The researchers caution that “the number of deaths does not reflect the true mortality of COVID-19.” They also note that they did not have enough genetic material to accurately assess duration of viral shedding.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who did not survive hospitalization for COVID-19 in Wuhan were more likely to be older, have comorbidities, and elevated D-dimer, according to the first study to examine risk factors associated with death among adults hospitalized with COVID-19. “Older age, showing signs of sepsis on admission, underlying diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes, and the prolonged use of noninvasive ventilation were important factors in the deaths of these patients,” coauthor Zhibo Liu said in a news release. Abnormal blood clotting was part of the clinical picture too.

Fei Zhou, MD, from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and colleagues conducted a retrospective, observational, multicenter cohort study of 191 patients, 137 of whom were discharged and 54 of whom died in the hospital.

The study, published online today in The Lancet, included all adult inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from Jinyintan Hospital and Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital who had been discharged or died by January 31 of this year. Severely ill patients in the province were transferred to these hospitals until February 1.

The researchers compared demographic, clinical, treatment, and laboratory data from electronic medical records between survivors and those who succumbed to the disease. The analysis also tested serial samples for viral RNA. Overall, 91 (48%) of the 191 patients had comorbidity. Most common was hypertension (30%), followed by diabetes (19%) and coronary heart disease (8%).

The odds of dying in the hospital increased with age (odds ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.17; per year increase in age), higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (5.65, 2.61-12.23; P < .0001), and D-dimer level exceeding 1 mcg/L on admission. The SOFA was previously called the “sepsis-related organ failure assessment score” and assesses rate of organ failure in intensive care units. Elevated D-dimer indicates increased risk of abnormal blood clotting, such as deep vein thrombosis.

Nonsurvivors compared with survivors had higher frequencies of respiratory failure (98% vs 36%), sepsis (100%, vs 42%), and secondary infections (50% vs 1%).

The average age of survivors was 52 years compared to 69 for those who died. Liu cited weakening of the immune system and increased inflammation, which damages organs and also promotes viral replication, as explanations for the age effect.

From the time of initial symptoms, median time to discharge from the hospital was 22 days. Average time to death was 18.5 days.

Fever persisted for a median of 12 days among all patients, and cough persisted for a median 19 days; 45% of the survivors were still coughing on discharge. In survivors, shortness of breath improved after 13 days, but persisted until death in the others.

Viral shedding persisted for a median duration of 20 days in survivors, ranging from 8 to 37. The virus (SARS-CoV-2) was detectable in nonsurvivors until death. Antiviral treatment did not curtail viral shedding.

But the viral shedding data come with a caveat. “The extended viral shedding noted in our study has important implications for guiding decisions around isolation precautions and antiviral treatment in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. However, we need to be clear that viral shedding time should not be confused with other self-isolation guidance for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19 but do not have symptoms, as this guidance is based on the incubation time of the virus,” explained colead author Bin Cao.

“Older age, elevated D-dimer levels, and high SOFA score could help clinicians to identify at an early stage those patients with COVID-19 who have poor prognosis. Prolonged viral shedding provides the rationale for a strategy of isolation of infected patients and optimal antiviral interventions in the future,” the researchers conclude.

A limitation in interpreting the findings of the study is that hospitalized patients do not represent the entire infected population. The researchers caution that “the number of deaths does not reflect the true mortality of COVID-19.” They also note that they did not have enough genetic material to accurately assess duration of viral shedding.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who did not survive hospitalization for COVID-19 in Wuhan were more likely to be older, have comorbidities, and elevated D-dimer, according to the first study to examine risk factors associated with death among adults hospitalized with COVID-19. “Older age, showing signs of sepsis on admission, underlying diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes, and the prolonged use of noninvasive ventilation were important factors in the deaths of these patients,” coauthor Zhibo Liu said in a news release. Abnormal blood clotting was part of the clinical picture too.

Fei Zhou, MD, from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and colleagues conducted a retrospective, observational, multicenter cohort study of 191 patients, 137 of whom were discharged and 54 of whom died in the hospital.

The study, published online today in The Lancet, included all adult inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from Jinyintan Hospital and Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital who had been discharged or died by January 31 of this year. Severely ill patients in the province were transferred to these hospitals until February 1.

The researchers compared demographic, clinical, treatment, and laboratory data from electronic medical records between survivors and those who succumbed to the disease. The analysis also tested serial samples for viral RNA. Overall, 91 (48%) of the 191 patients had comorbidity. Most common was hypertension (30%), followed by diabetes (19%) and coronary heart disease (8%).

The odds of dying in the hospital increased with age (odds ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.17; per year increase in age), higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (5.65, 2.61-12.23; P < .0001), and D-dimer level exceeding 1 mcg/L on admission. The SOFA was previously called the “sepsis-related organ failure assessment score” and assesses rate of organ failure in intensive care units. Elevated D-dimer indicates increased risk of abnormal blood clotting, such as deep vein thrombosis.

Nonsurvivors compared with survivors had higher frequencies of respiratory failure (98% vs 36%), sepsis (100%, vs 42%), and secondary infections (50% vs 1%).

The average age of survivors was 52 years compared to 69 for those who died. Liu cited weakening of the immune system and increased inflammation, which damages organs and also promotes viral replication, as explanations for the age effect.

From the time of initial symptoms, median time to discharge from the hospital was 22 days. Average time to death was 18.5 days.

Fever persisted for a median of 12 days among all patients, and cough persisted for a median 19 days; 45% of the survivors were still coughing on discharge. In survivors, shortness of breath improved after 13 days, but persisted until death in the others.

Viral shedding persisted for a median duration of 20 days in survivors, ranging from 8 to 37. The virus (SARS-CoV-2) was detectable in nonsurvivors until death. Antiviral treatment did not curtail viral shedding.

But the viral shedding data come with a caveat. “The extended viral shedding noted in our study has important implications for guiding decisions around isolation precautions and antiviral treatment in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. However, we need to be clear that viral shedding time should not be confused with other self-isolation guidance for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19 but do not have symptoms, as this guidance is based on the incubation time of the virus,” explained colead author Bin Cao.

“Older age, elevated D-dimer levels, and high SOFA score could help clinicians to identify at an early stage those patients with COVID-19 who have poor prognosis. Prolonged viral shedding provides the rationale for a strategy of isolation of infected patients and optimal antiviral interventions in the future,” the researchers conclude.

A limitation in interpreting the findings of the study is that hospitalized patients do not represent the entire infected population. The researchers caution that “the number of deaths does not reflect the true mortality of COVID-19.” They also note that they did not have enough genetic material to accurately assess duration of viral shedding.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Know the 15% rule in scleroderma

MAUI, HAWAII – The 15% rule in scleroderma is a handy tool that raises awareness of the disease’s associated prevalence of various severe organ complications so clinicians can screen appropriately, Janet Pope, MD, said at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Dr. Pope and colleagues in the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group developed the 15% rule because they recognized that scleroderma is rare enough that most physicians practicing outside of a few specialized centers don’t see many affected patients. The systemic autoimmune disease is marked by numerous possible expressions of vascular inflammation and malfunction, fibrosis, and autoimmunity in different organ systems.

“A lot of clinicians do not know how common this stuff is,” according to Dr. Pope, professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario and head of the division of rheumatology at St. Joseph’s Health Center in London, Ont.

Basically, the 15% rule holds that, at any given time, a patient with scleroderma has roughly a 15% chance – or one in six – of having any of an extensive array of severe organ complications. That means a 15% chance of having prevalent clinically significant pulmonary hypertension as defined by a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 45 mm Hg or more on Doppler echocardiography, a 15% likelihood of interstitial lung disease or clinically significant pulmonary fibrosis as suggested by a forced vital capacity less than 70% of predicted, a 15% prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome, a 15% likelihood of having pulmonary artery hypertension upon right heart catheterization, a 15% chance of inflammatory arthritis, and a one-in-six chance of having a myopathy or myositis. Also, diastolic dysfunction, 15%. Ditto symptomatic arrhythmias.

“It’s a good little rule of thumb,” Dr. Pope commented.

The odds of having a current digital ulcer on any given day? Again, about 15%. In addition, scleroderma patients have a 15% lifetime risk of developing a complicated digital ulcer requiring hospitalization and/or amputation, she continued.

And while the prevalence of scleroderma renal crisis in the overall population with scleroderma is low, at 3%, in the subgroup with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, it climbs to 12%-15%.

Every rule has its exceptions. The 15% rule doesn’t apply to Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is present in nearly all patients with scleroderma, nor to gastroesophageal reflux disease or dysphagia, present in roughly 80% of patients.

Dr. Pope and coinvestigators developed the 15% rule pertaining to the prevalence of serious organ complications in scleroderma by conducting a systematic review of 69 published studies, each including a minimum of 50 scleroderma patients. The detailed results of the systematic review have been published.

Dr. Pope reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The 15% rule in scleroderma is a handy tool that raises awareness of the disease’s associated prevalence of various severe organ complications so clinicians can screen appropriately, Janet Pope, MD, said at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Dr. Pope and colleagues in the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group developed the 15% rule because they recognized that scleroderma is rare enough that most physicians practicing outside of a few specialized centers don’t see many affected patients. The systemic autoimmune disease is marked by numerous possible expressions of vascular inflammation and malfunction, fibrosis, and autoimmunity in different organ systems.

“A lot of clinicians do not know how common this stuff is,” according to Dr. Pope, professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario and head of the division of rheumatology at St. Joseph’s Health Center in London, Ont.

Basically, the 15% rule holds that, at any given time, a patient with scleroderma has roughly a 15% chance – or one in six – of having any of an extensive array of severe organ complications. That means a 15% chance of having prevalent clinically significant pulmonary hypertension as defined by a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 45 mm Hg or more on Doppler echocardiography, a 15% likelihood of interstitial lung disease or clinically significant pulmonary fibrosis as suggested by a forced vital capacity less than 70% of predicted, a 15% prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome, a 15% likelihood of having pulmonary artery hypertension upon right heart catheterization, a 15% chance of inflammatory arthritis, and a one-in-six chance of having a myopathy or myositis. Also, diastolic dysfunction, 15%. Ditto symptomatic arrhythmias.

“It’s a good little rule of thumb,” Dr. Pope commented.

The odds of having a current digital ulcer on any given day? Again, about 15%. In addition, scleroderma patients have a 15% lifetime risk of developing a complicated digital ulcer requiring hospitalization and/or amputation, she continued.

And while the prevalence of scleroderma renal crisis in the overall population with scleroderma is low, at 3%, in the subgroup with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, it climbs to 12%-15%.

Every rule has its exceptions. The 15% rule doesn’t apply to Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is present in nearly all patients with scleroderma, nor to gastroesophageal reflux disease or dysphagia, present in roughly 80% of patients.

Dr. Pope and coinvestigators developed the 15% rule pertaining to the prevalence of serious organ complications in scleroderma by conducting a systematic review of 69 published studies, each including a minimum of 50 scleroderma patients. The detailed results of the systematic review have been published.

Dr. Pope reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The 15% rule in scleroderma is a handy tool that raises awareness of the disease’s associated prevalence of various severe organ complications so clinicians can screen appropriately, Janet Pope, MD, said at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Dr. Pope and colleagues in the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group developed the 15% rule because they recognized that scleroderma is rare enough that most physicians practicing outside of a few specialized centers don’t see many affected patients. The systemic autoimmune disease is marked by numerous possible expressions of vascular inflammation and malfunction, fibrosis, and autoimmunity in different organ systems.

“A lot of clinicians do not know how common this stuff is,” according to Dr. Pope, professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario and head of the division of rheumatology at St. Joseph’s Health Center in London, Ont.

Basically, the 15% rule holds that, at any given time, a patient with scleroderma has roughly a 15% chance – or one in six – of having any of an extensive array of severe organ complications. That means a 15% chance of having prevalent clinically significant pulmonary hypertension as defined by a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 45 mm Hg or more on Doppler echocardiography, a 15% likelihood of interstitial lung disease or clinically significant pulmonary fibrosis as suggested by a forced vital capacity less than 70% of predicted, a 15% prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome, a 15% likelihood of having pulmonary artery hypertension upon right heart catheterization, a 15% chance of inflammatory arthritis, and a one-in-six chance of having a myopathy or myositis. Also, diastolic dysfunction, 15%. Ditto symptomatic arrhythmias.

“It’s a good little rule of thumb,” Dr. Pope commented.

The odds of having a current digital ulcer on any given day? Again, about 15%. In addition, scleroderma patients have a 15% lifetime risk of developing a complicated digital ulcer requiring hospitalization and/or amputation, she continued.

And while the prevalence of scleroderma renal crisis in the overall population with scleroderma is low, at 3%, in the subgroup with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, it climbs to 12%-15%.

Every rule has its exceptions. The 15% rule doesn’t apply to Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is present in nearly all patients with scleroderma, nor to gastroesophageal reflux disease or dysphagia, present in roughly 80% of patients.

Dr. Pope and coinvestigators developed the 15% rule pertaining to the prevalence of serious organ complications in scleroderma by conducting a systematic review of 69 published studies, each including a minimum of 50 scleroderma patients. The detailed results of the systematic review have been published.

Dr. Pope reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2020

Prescription cascade more likely after CCBs than other hypertension meds

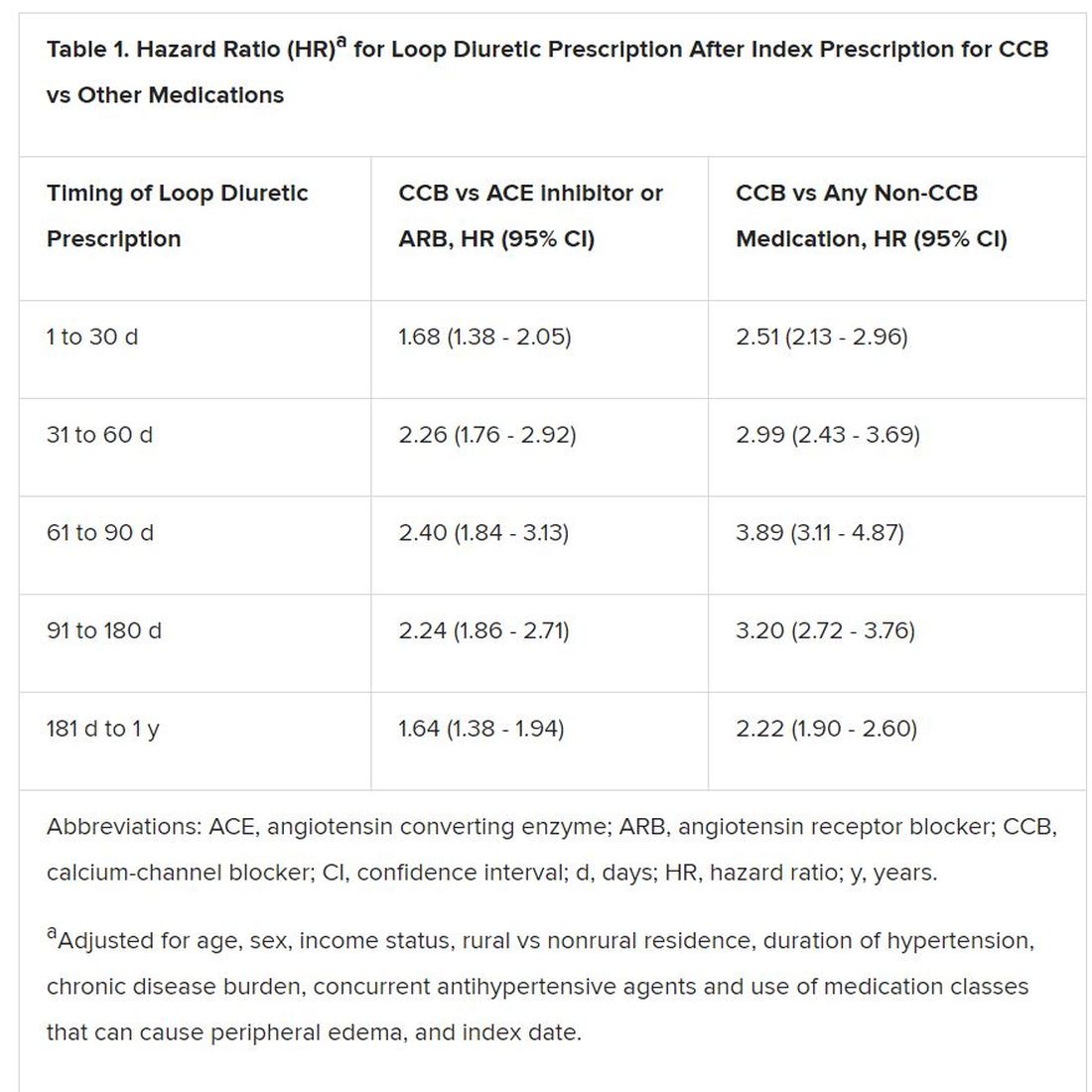

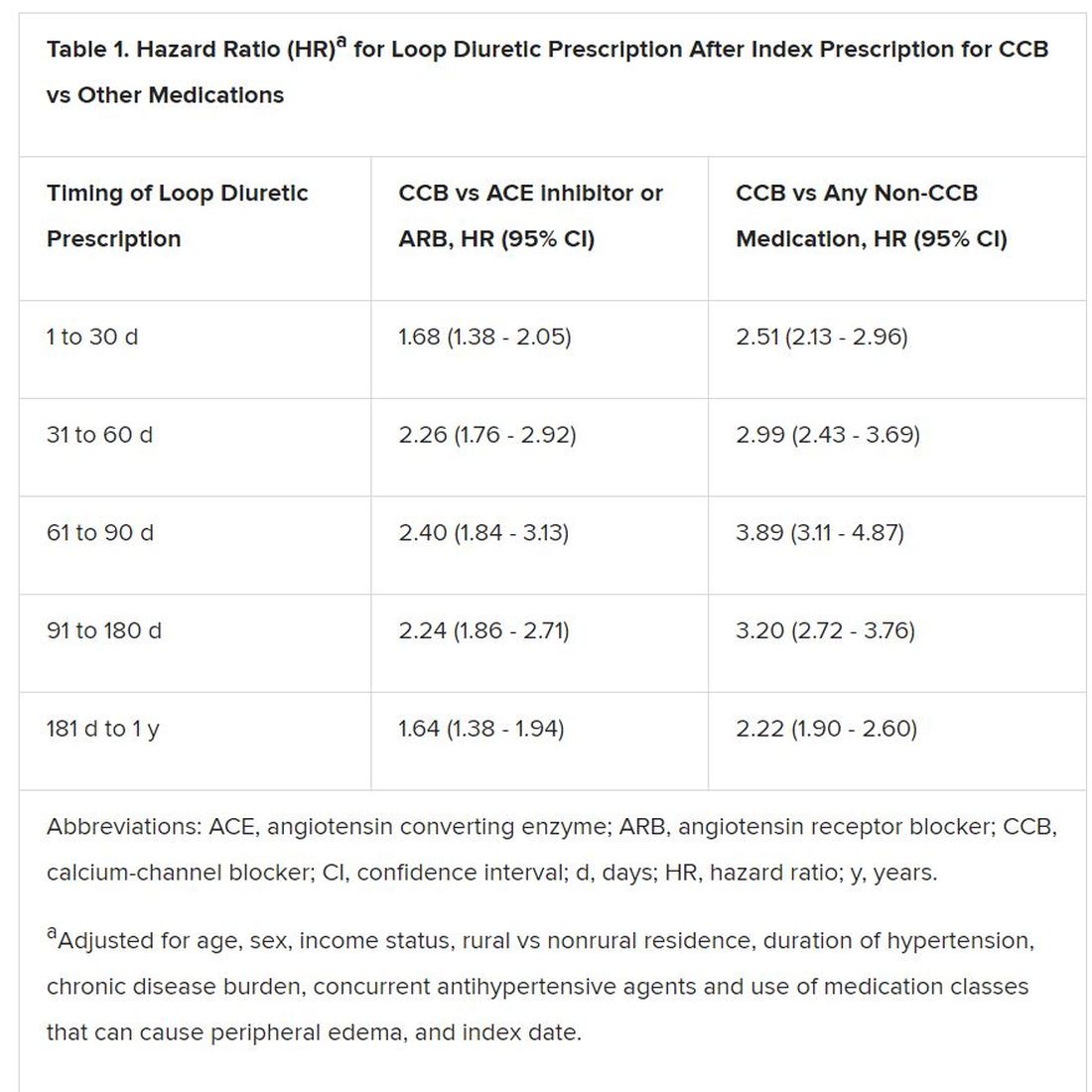

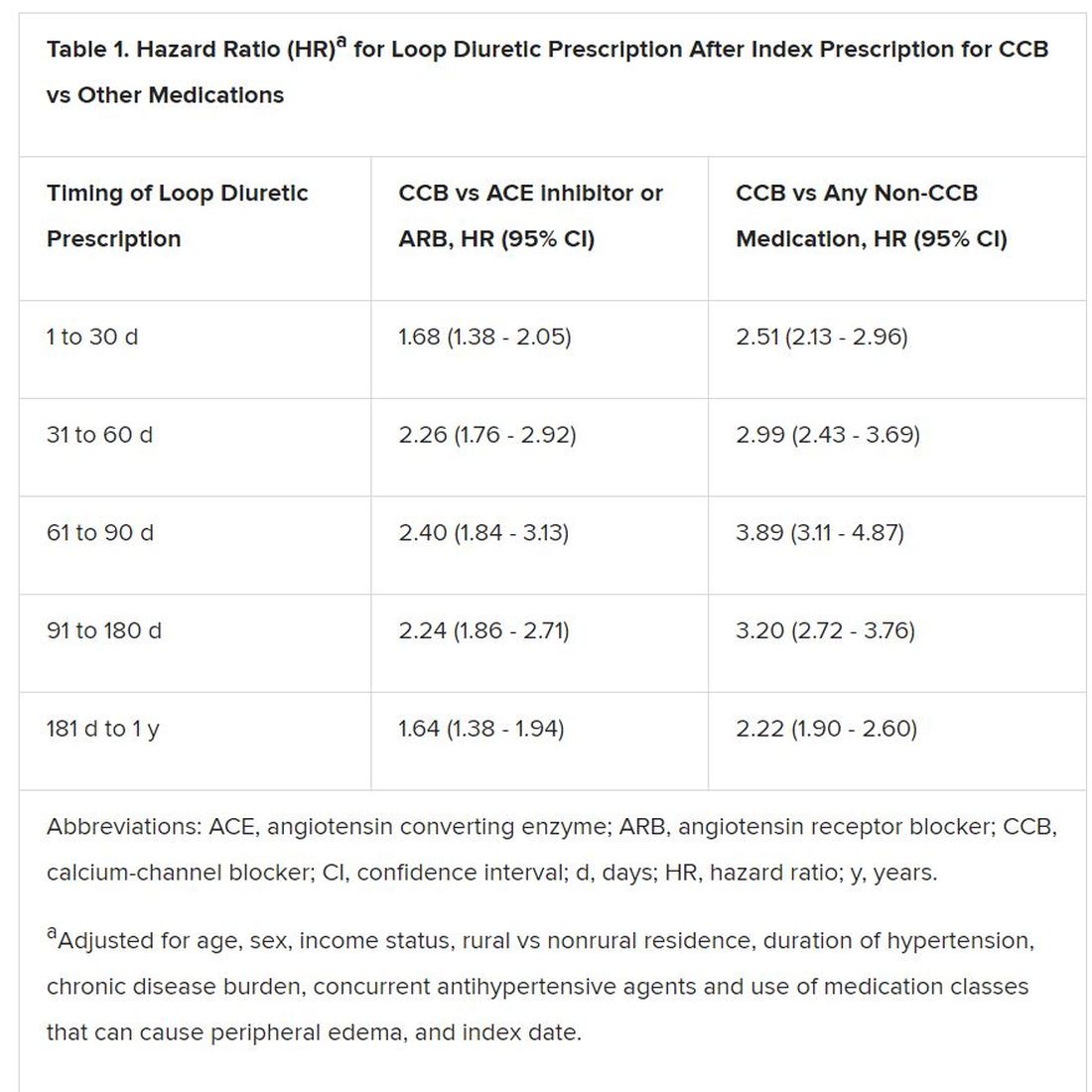

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.

That was unexpected, McCarthy observed, because “peripheral edema occurs more commonly in people taking dihydropyridine CCBs, like amlodipine, compared to non–dihydropyridine CCBs, such as verapamil and diltiazem.”

Savage, McCarthy, their coauthors, and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.

That was unexpected, McCarthy observed, because “peripheral edema occurs more commonly in people taking dihydropyridine CCBs, like amlodipine, compared to non–dihydropyridine CCBs, such as verapamil and diltiazem.”

Savage, McCarthy, their coauthors, and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.

That was unexpected, McCarthy observed, because “peripheral edema occurs more commonly in people taking dihydropyridine CCBs, like amlodipine, compared to non–dihydropyridine CCBs, such as verapamil and diltiazem.”

Savage, McCarthy, their coauthors, and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA promises rigorous review of new renal denervation trials

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Just a month before results from the first of several new pivotal trials with a renal denervation device are to be presented, a Food and Drug Administration medical officer speaking at CRT 2020 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute explained which data will most attract the scrutiny of regulators.

“The FDA is very interested in these devices. We recognize that there is a clinical need, but a reasonable benefit-to-risk relationship has to be established,” said Meir Shinnar, MD, PhD, who works in the division of cardiac devices in the FDA’s Office of Device Evaluation.

The field of renal denervation is expected to heat up again if the results of the SPYRAL HTN OFF MED pivotal trial, planned as a late-breaking presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology in March 2020, are positive. However, long-term safety will remain a concern, and positive results will not diminish the rigor with which the relative safety and efficacy of other devices in late stages of clinical testing are evaluated.

“The safety profile is unique to the device design and the procedural technique,” Dr. Shinnar said. For example, vascular injury from the energy employed for denervation, whether radiofrequency or another modality, is an important theoretical risk. A minor initial injury might have no immediate consequences but pose major risks if it leads to altered kidney function over time.

“Most of the follow-up data we have now [with renal denervation devices] is about 1-3 years, but I think long-term safety requires a minimum of 5 years of safety data,” Dr. Shinnar said. “We do not expect all that data to be available at the time of approval, but postmarketing studies will be needed.”

Almost 6 years after the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial failed to show a significant reduction in blood pressure among patients with resistant hypertension treated with renal denervation rather than a sham procedure (N Engl J Med 2014;370:1393-401), this treatment is again considered promising. The surprising SYMPLICITY HTN-3 result led to several revisions in technique based on the suspicion that denervation was inadequate.

However, the basic principles remain unchanged. For renal denervation, SPYRAL HTN OFF MED, like the SYMPLICITY HTN 3 study, is employing the Symplicity (Medtronic) device, which has been approved in 50 countries but not in the United States, Canada, or Japan.

SPYRAL HTN OFF MED is designed to provide a very straightforward test of efficacy. Unlike SYMPLICITY HTN-3, which permitted patients to remain on their antihypertensive medications, patients in SPYRAL HTN OFF MED will be tested in the absence of drug therapy (a trial with adjunctive antihypertensive drugs, SPYRAL HTN ON MED, is ongoing). This is a design feature that is relevant to regulatory evaluation.

Although not speaking about the SPYRAL HTN OFF MED trial specifically, Dr. Shinnar noted that “the bar is considered to be higher for a first-line indication than when a device is used as an adjunctive to drug therapy.”

Whether used with or without medications, devices are not likely to receive approval without showing a durable benefit. Dr. Shinnar, citing the surgical studies in which blood pressure control was lost 1-2 years after denervation, said 12 months is now considered a “preferred” length of follow-up to confirm efficacy.

If renal denervation moves forward as a result of the new wave of phase 3 trials, there will still be many unanswered questions, according to Dr. Shinnar, who noted that the FDA convened an advisory committee in December 2018 to gather expert opinion about meaningful safety as well as efficacy endpoints for this modality. One will be determining which populations, defined by age, gender, or phenotype, most benefit.

It also remains unclear whether the first approval will create a standard to which subsequent devices should be compared, according to Dr. Shinnar. Although the FDA recognizes blood pressure reductions as an acceptable endpoint, he believes that documentation of the impact on clinical events will be sought in postmarketing analyses.

“All of the denervation modalities involve class 3 devices that require significant data,” Dr. Shinnar cautioned.

Even if the SPYRAL HTN OFF MED trial is positive on the basis of efficacy, it does not guarantee regulatory approval. Dr. Shinnar described a multifaceted approach to defining an acceptable risk-to-benefit ratio from approved devices, and warned that several points regarding the evaluation of renal denervation devices by the FDA are still being debated internally.

Dr. Shinnar reported no potential financial conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Just a month before results from the first of several new pivotal trials with a renal denervation device are to be presented, a Food and Drug Administration medical officer speaking at CRT 2020 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute explained which data will most attract the scrutiny of regulators.

“The FDA is very interested in these devices. We recognize that there is a clinical need, but a reasonable benefit-to-risk relationship has to be established,” said Meir Shinnar, MD, PhD, who works in the division of cardiac devices in the FDA’s Office of Device Evaluation.

The field of renal denervation is expected to heat up again if the results of the SPYRAL HTN OFF MED pivotal trial, planned as a late-breaking presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology in March 2020, are positive. However, long-term safety will remain a concern, and positive results will not diminish the rigor with which the relative safety and efficacy of other devices in late stages of clinical testing are evaluated.

“The safety profile is unique to the device design and the procedural technique,” Dr. Shinnar said. For example, vascular injury from the energy employed for denervation, whether radiofrequency or another modality, is an important theoretical risk. A minor initial injury might have no immediate consequences but pose major risks if it leads to altered kidney function over time.

“Most of the follow-up data we have now [with renal denervation devices] is about 1-3 years, but I think long-term safety requires a minimum of 5 years of safety data,” Dr. Shinnar said. “We do not expect all that data to be available at the time of approval, but postmarketing studies will be needed.”

Almost 6 years after the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial failed to show a significant reduction in blood pressure among patients with resistant hypertension treated with renal denervation rather than a sham procedure (N Engl J Med 2014;370:1393-401), this treatment is again considered promising. The surprising SYMPLICITY HTN-3 result led to several revisions in technique based on the suspicion that denervation was inadequate.

However, the basic principles remain unchanged. For renal denervation, SPYRAL HTN OFF MED, like the SYMPLICITY HTN 3 study, is employing the Symplicity (Medtronic) device, which has been approved in 50 countries but not in the United States, Canada, or Japan.

SPYRAL HTN OFF MED is designed to provide a very straightforward test of efficacy. Unlike SYMPLICITY HTN-3, which permitted patients to remain on their antihypertensive medications, patients in SPYRAL HTN OFF MED will be tested in the absence of drug therapy (a trial with adjunctive antihypertensive drugs, SPYRAL HTN ON MED, is ongoing). This is a design feature that is relevant to regulatory evaluation.

Although not speaking about the SPYRAL HTN OFF MED trial specifically, Dr. Shinnar noted that “the bar is considered to be higher for a first-line indication than when a device is used as an adjunctive to drug therapy.”

Whether used with or without medications, devices are not likely to receive approval without showing a durable benefit. Dr. Shinnar, citing the surgical studies in which blood pressure control was lost 1-2 years after denervation, said 12 months is now considered a “preferred” length of follow-up to confirm efficacy.

If renal denervation moves forward as a result of the new wave of phase 3 trials, there will still be many unanswered questions, according to Dr. Shinnar, who noted that the FDA convened an advisory committee in December 2018 to gather expert opinion about meaningful safety as well as efficacy endpoints for this modality. One will be determining which populations, defined by age, gender, or phenotype, most benefit.

It also remains unclear whether the first approval will create a standard to which subsequent devices should be compared, according to Dr. Shinnar. Although the FDA recognizes blood pressure reductions as an acceptable endpoint, he believes that documentation of the impact on clinical events will be sought in postmarketing analyses.

“All of the denervation modalities involve class 3 devices that require significant data,” Dr. Shinnar cautioned.

Even if the SPYRAL HTN OFF MED trial is positive on the basis of efficacy, it does not guarantee regulatory approval. Dr. Shinnar described a multifaceted approach to defining an acceptable risk-to-benefit ratio from approved devices, and warned that several points regarding the evaluation of renal denervation devices by the FDA are still being debated internally.

Dr. Shinnar reported no potential financial conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Just a month before results from the first of several new pivotal trials with a renal denervation device are to be presented, a Food and Drug Administration medical officer speaking at CRT 2020 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute explained which data will most attract the scrutiny of regulators.

“The FDA is very interested in these devices. We recognize that there is a clinical need, but a reasonable benefit-to-risk relationship has to be established,” said Meir Shinnar, MD, PhD, who works in the division of cardiac devices in the FDA’s Office of Device Evaluation.

The field of renal denervation is expected to heat up again if the results of the SPYRAL HTN OFF MED pivotal trial, planned as a late-breaking presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology in March 2020, are positive. However, long-term safety will remain a concern, and positive results will not diminish the rigor with which the relative safety and efficacy of other devices in late stages of clinical testing are evaluated.

“The safety profile is unique to the device design and the procedural technique,” Dr. Shinnar said. For example, vascular injury from the energy employed for denervation, whether radiofrequency or another modality, is an important theoretical risk. A minor initial injury might have no immediate consequences but pose major risks if it leads to altered kidney function over time.

“Most of the follow-up data we have now [with renal denervation devices] is about 1-3 years, but I think long-term safety requires a minimum of 5 years of safety data,” Dr. Shinnar said. “We do not expect all that data to be available at the time of approval, but postmarketing studies will be needed.”

Almost 6 years after the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial failed to show a significant reduction in blood pressure among patients with resistant hypertension treated with renal denervation rather than a sham procedure (N Engl J Med 2014;370:1393-401), this treatment is again considered promising. The surprising SYMPLICITY HTN-3 result led to several revisions in technique based on the suspicion that denervation was inadequate.

However, the basic principles remain unchanged. For renal denervation, SPYRAL HTN OFF MED, like the SYMPLICITY HTN 3 study, is employing the Symplicity (Medtronic) device, which has been approved in 50 countries but not in the United States, Canada, or Japan.

SPYRAL HTN OFF MED is designed to provide a very straightforward test of efficacy. Unlike SYMPLICITY HTN-3, which permitted patients to remain on their antihypertensive medications, patients in SPYRAL HTN OFF MED will be tested in the absence of drug therapy (a trial with adjunctive antihypertensive drugs, SPYRAL HTN ON MED, is ongoing). This is a design feature that is relevant to regulatory evaluation.