User login

Cochrane Review nixes specific allergen immunotherapy for atopic dermatitis

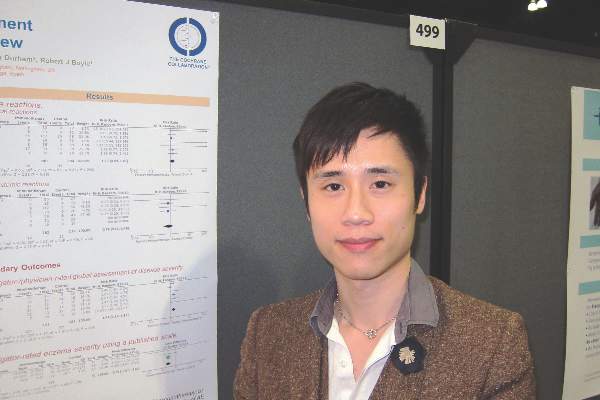

LOS ANGELES – A new Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis has concluded there is no consistent evidence that specific allergen immunotherapy is beneficial in patients with atopic dermatitis, Dr. Herman H. Tam reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“We know that for specific allergen immunotherapy, there have been really good results in allergic rhinitis and venom allergy. For atopic dermatitis, however, dating back almost 40 years, we found there have only been 12 randomized trials using standardized allergen extracts. The quality of evidence was low, and the study findings have been inconsistent,” Dr. Tam, first author of the Cochrane review, said in an interview.

The dozen trials included a total of 733 children and adults in nine countries. Because of insufficient follow-up in most of the studies, coupled with the use of a variety of endpoints, the analysis concluded that “specific allergen immunotherapy cannot be recommended for atopic eczema at present” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 12;2:CD008774).

“We found no consistent evidence that specific allergen immunotherapy provides a treatment benefit for people with allergic eczema, compared with placebo or no treatment. The message of this review is that we need more large randomized trials with better controls, modern high-quality allergen extracts that have proven themselves in other allergic diseases, and patient-centered outcome measures,” according to Dr. Tam, who participated in the Cochrane review while at Imperial College London and is now a pediatric resident at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg.

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

LOS ANGELES – A new Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis has concluded there is no consistent evidence that specific allergen immunotherapy is beneficial in patients with atopic dermatitis, Dr. Herman H. Tam reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“We know that for specific allergen immunotherapy, there have been really good results in allergic rhinitis and venom allergy. For atopic dermatitis, however, dating back almost 40 years, we found there have only been 12 randomized trials using standardized allergen extracts. The quality of evidence was low, and the study findings have been inconsistent,” Dr. Tam, first author of the Cochrane review, said in an interview.

The dozen trials included a total of 733 children and adults in nine countries. Because of insufficient follow-up in most of the studies, coupled with the use of a variety of endpoints, the analysis concluded that “specific allergen immunotherapy cannot be recommended for atopic eczema at present” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 12;2:CD008774).

“We found no consistent evidence that specific allergen immunotherapy provides a treatment benefit for people with allergic eczema, compared with placebo or no treatment. The message of this review is that we need more large randomized trials with better controls, modern high-quality allergen extracts that have proven themselves in other allergic diseases, and patient-centered outcome measures,” according to Dr. Tam, who participated in the Cochrane review while at Imperial College London and is now a pediatric resident at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg.

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

LOS ANGELES – A new Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis has concluded there is no consistent evidence that specific allergen immunotherapy is beneficial in patients with atopic dermatitis, Dr. Herman H. Tam reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“We know that for specific allergen immunotherapy, there have been really good results in allergic rhinitis and venom allergy. For atopic dermatitis, however, dating back almost 40 years, we found there have only been 12 randomized trials using standardized allergen extracts. The quality of evidence was low, and the study findings have been inconsistent,” Dr. Tam, first author of the Cochrane review, said in an interview.

The dozen trials included a total of 733 children and adults in nine countries. Because of insufficient follow-up in most of the studies, coupled with the use of a variety of endpoints, the analysis concluded that “specific allergen immunotherapy cannot be recommended for atopic eczema at present” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 12;2:CD008774).

“We found no consistent evidence that specific allergen immunotherapy provides a treatment benefit for people with allergic eczema, compared with placebo or no treatment. The message of this review is that we need more large randomized trials with better controls, modern high-quality allergen extracts that have proven themselves in other allergic diseases, and patient-centered outcome measures,” according to Dr. Tam, who participated in the Cochrane review while at Imperial College London and is now a pediatric resident at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg.

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The available evidence doesn’t support using specific allergen immunotherapy for atopic dermatitis.

Major finding: A new Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis has found “no consistent evidence” that specific allergen immunotherapy is more effective than placebo in treating atopic dermatitis.

Data source: This was a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials of specific allergen immunotherapy in 733 pediatric and adult atopic dermatitis patients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Most atopic lesions colonized with Staph

Patients with atopic dermatitis are at an increased risk of Staphylococcus aureus colonization of both their lesional and nonlesional skin, as well as their nose, compared with healthy controls, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Dr. J.E.E. Totté of the department of dermatology at the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, and associates conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis to derive pooled estimates of the prevalence and odds of colonization with S. aureus in patients with atopic dermatitis. They focused on original, human experimental, and observational studies including patients of any age with a confirmed diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Mar 19. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14566).

Dr. Totté and colleagues identified a total of 4,909 articles, of which 95 were found to meet the study inclusion criteria. All of the included studies were observational, with 30 comparing atopic dermatitis patients with healthy controls.

Almost three-quarters (70%) of patients had S. aureus colonization of lesional skin, while 39% had colonization of nonlesional skin, based on 81 studies including 5,231 patients and 30 studies including 1,496 patients, respectively. Nasal colonization was found in 62% of patients, based on analysis of 43 studies including 2,476 patients.

S. aureus colonization is an important factor in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and should lead to evaluations of targeted antistaphylococcal therapy for the skin and nose, the investigators advised.

The authors reported that the department of dermatology of the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre Rotterdam received an unrestricted grant from Micreos Human Health. Two coauthors disclosed ties to industry sources.

Patients with atopic dermatitis are at an increased risk of Staphylococcus aureus colonization of both their lesional and nonlesional skin, as well as their nose, compared with healthy controls, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Dr. J.E.E. Totté of the department of dermatology at the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, and associates conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis to derive pooled estimates of the prevalence and odds of colonization with S. aureus in patients with atopic dermatitis. They focused on original, human experimental, and observational studies including patients of any age with a confirmed diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Mar 19. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14566).

Dr. Totté and colleagues identified a total of 4,909 articles, of which 95 were found to meet the study inclusion criteria. All of the included studies were observational, with 30 comparing atopic dermatitis patients with healthy controls.

Almost three-quarters (70%) of patients had S. aureus colonization of lesional skin, while 39% had colonization of nonlesional skin, based on 81 studies including 5,231 patients and 30 studies including 1,496 patients, respectively. Nasal colonization was found in 62% of patients, based on analysis of 43 studies including 2,476 patients.

S. aureus colonization is an important factor in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and should lead to evaluations of targeted antistaphylococcal therapy for the skin and nose, the investigators advised.

The authors reported that the department of dermatology of the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre Rotterdam received an unrestricted grant from Micreos Human Health. Two coauthors disclosed ties to industry sources.

Patients with atopic dermatitis are at an increased risk of Staphylococcus aureus colonization of both their lesional and nonlesional skin, as well as their nose, compared with healthy controls, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Dr. J.E.E. Totté of the department of dermatology at the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, and associates conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis to derive pooled estimates of the prevalence and odds of colonization with S. aureus in patients with atopic dermatitis. They focused on original, human experimental, and observational studies including patients of any age with a confirmed diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Mar 19. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14566).

Dr. Totté and colleagues identified a total of 4,909 articles, of which 95 were found to meet the study inclusion criteria. All of the included studies were observational, with 30 comparing atopic dermatitis patients with healthy controls.

Almost three-quarters (70%) of patients had S. aureus colonization of lesional skin, while 39% had colonization of nonlesional skin, based on 81 studies including 5,231 patients and 30 studies including 1,496 patients, respectively. Nasal colonization was found in 62% of patients, based on analysis of 43 studies including 2,476 patients.

S. aureus colonization is an important factor in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and should lead to evaluations of targeted antistaphylococcal therapy for the skin and nose, the investigators advised.

The authors reported that the department of dermatology of the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre Rotterdam received an unrestricted grant from Micreos Human Health. Two coauthors disclosed ties to industry sources.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Consider addressing S. aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis patients.

Major finding: Most patients (70%) were colonized with S. aureus on lesional skin, while 39% were colonized on nonlesional skin.

Data source: Literature review and meta-analysis involving 95 studies, 30 with healthy controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by an unrestricted grant from Micreos Human Health to Erasmus MC University Medical Centre. Two coauthors disclosed ties to industry sources.

Asthma treatment adherence better in children with more severe symptoms

Children with better adherence to asthma treatments tended to have more severe asthma symptoms, according to Dr. Marjolein Engelkes of Erasmus University, Rotterdam (The Netherlands) and her associates.

Of the 14,303 children with asthma included in the study, short-acting beta2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids were the most commonly prescribed treatments at 38 users/100 person-years and 31 users/100 person-years, respectively. Inhaled corticosteroid prescriptions were most common during the winter and in September, and decreased as children increased in age.

The median medication possession ratio (MPR) for inhaled corticosteroids was 56%. Children with an MPR over 87% were significantly more likely to be younger at the start of inhaled corticosteroid treatment, visit specialists more often, and to have more exacerbations than children with an MPR less than 37%.

“These findings indicate that there is room for improvement of adherence to treatment, especially in children with milder forms of asthma,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology (2016 Mar. doi: 10.1111/pai.12507).

Children with better adherence to asthma treatments tended to have more severe asthma symptoms, according to Dr. Marjolein Engelkes of Erasmus University, Rotterdam (The Netherlands) and her associates.

Of the 14,303 children with asthma included in the study, short-acting beta2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids were the most commonly prescribed treatments at 38 users/100 person-years and 31 users/100 person-years, respectively. Inhaled corticosteroid prescriptions were most common during the winter and in September, and decreased as children increased in age.

The median medication possession ratio (MPR) for inhaled corticosteroids was 56%. Children with an MPR over 87% were significantly more likely to be younger at the start of inhaled corticosteroid treatment, visit specialists more often, and to have more exacerbations than children with an MPR less than 37%.

“These findings indicate that there is room for improvement of adherence to treatment, especially in children with milder forms of asthma,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology (2016 Mar. doi: 10.1111/pai.12507).

Children with better adherence to asthma treatments tended to have more severe asthma symptoms, according to Dr. Marjolein Engelkes of Erasmus University, Rotterdam (The Netherlands) and her associates.

Of the 14,303 children with asthma included in the study, short-acting beta2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids were the most commonly prescribed treatments at 38 users/100 person-years and 31 users/100 person-years, respectively. Inhaled corticosteroid prescriptions were most common during the winter and in September, and decreased as children increased in age.

The median medication possession ratio (MPR) for inhaled corticosteroids was 56%. Children with an MPR over 87% were significantly more likely to be younger at the start of inhaled corticosteroid treatment, visit specialists more often, and to have more exacerbations than children with an MPR less than 37%.

“These findings indicate that there is room for improvement of adherence to treatment, especially in children with milder forms of asthma,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology (2016 Mar. doi: 10.1111/pai.12507).

FROM PEDIATRIC ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY

Asthma, Eczema in Children Unrelated to Allergic Sensitization

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Asthma, eczema in children unrelated to allergic sensitization

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Stick with wheat flour for baked egg and milk challenges

LOS ANGELES – Children who pass oral food challenges to baked egg and milk with wheat flour are at risk for reacting to baked goods made with nonwheat flours, according to a review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The children were already known to be sensitive to egg and milk, and some were being challenged to see if exposure therapy was helping. Unbeknown to the pediatric food allergy team, a kitchen worker at National Jewish had started making muffins with rice flour, thinking it would be safer.

During the month of muffins with rice flour, the failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14) (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.579).

Adjusting for age, gender, and atopic dermatitis, children were more than five times more likely to fail baked eggs without wheat (odds ratio, 5.4; P = .002), and more than four times more likely to fail baked milk (OR, 4.06; P = .05).

Given that the phenomenon hasn’t been reported before, “This was very surprising to us,” said study investigator Dr. Bruce Lanser, director of the pediatric food allergy program at National Jewish. “You have to warn parents that if children pass a baked challenge with wheat, they have to continue to eat their baked milk and egg with wheat. Gluten-free products are not going to have the same effect.

“If somebody is avoiding wheat because it causes a bit of redness and itchiness, you have to clear that wheat allergy” before moving to baked egg and milk, Dr. Lanser added.

There’s also concern that “kids will go home after passing a wheat muffin challenge, eat something that’s gluten-free, and have a reaction,” he noted. Wheat-free baked goods might also not build tolerance as well, although that’s not clear from the study, Dr. Lanser said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Wheat seems to have something unique that alters the allergic properties of egg and milk proteins to help children outgrow their sensitivities. “Rice doesn’t have the same effect,” he observed, and it’s not known if any other grains do. Dr. Lanser said he is interested in looking into rye, barley, oats, and other alternatives.

The mean age of the children in the study was 6 years, and most children had multiple food allergies. Sensitization was confirmed by skin tests and specific IgE.

Meanwhile, there’s a new rule in the National Jewish kitchen: Unless a child has true celiac disease, “always make [challenge] muffins with wheat,” Dr. Lanser said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Children who pass oral food challenges to baked egg and milk with wheat flour are at risk for reacting to baked goods made with nonwheat flours, according to a review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The children were already known to be sensitive to egg and milk, and some were being challenged to see if exposure therapy was helping. Unbeknown to the pediatric food allergy team, a kitchen worker at National Jewish had started making muffins with rice flour, thinking it would be safer.

During the month of muffins with rice flour, the failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14) (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.579).

Adjusting for age, gender, and atopic dermatitis, children were more than five times more likely to fail baked eggs without wheat (odds ratio, 5.4; P = .002), and more than four times more likely to fail baked milk (OR, 4.06; P = .05).

Given that the phenomenon hasn’t been reported before, “This was very surprising to us,” said study investigator Dr. Bruce Lanser, director of the pediatric food allergy program at National Jewish. “You have to warn parents that if children pass a baked challenge with wheat, they have to continue to eat their baked milk and egg with wheat. Gluten-free products are not going to have the same effect.

“If somebody is avoiding wheat because it causes a bit of redness and itchiness, you have to clear that wheat allergy” before moving to baked egg and milk, Dr. Lanser added.

There’s also concern that “kids will go home after passing a wheat muffin challenge, eat something that’s gluten-free, and have a reaction,” he noted. Wheat-free baked goods might also not build tolerance as well, although that’s not clear from the study, Dr. Lanser said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Wheat seems to have something unique that alters the allergic properties of egg and milk proteins to help children outgrow their sensitivities. “Rice doesn’t have the same effect,” he observed, and it’s not known if any other grains do. Dr. Lanser said he is interested in looking into rye, barley, oats, and other alternatives.

The mean age of the children in the study was 6 years, and most children had multiple food allergies. Sensitization was confirmed by skin tests and specific IgE.

Meanwhile, there’s a new rule in the National Jewish kitchen: Unless a child has true celiac disease, “always make [challenge] muffins with wheat,” Dr. Lanser said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Children who pass oral food challenges to baked egg and milk with wheat flour are at risk for reacting to baked goods made with nonwheat flours, according to a review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The children were already known to be sensitive to egg and milk, and some were being challenged to see if exposure therapy was helping. Unbeknown to the pediatric food allergy team, a kitchen worker at National Jewish had started making muffins with rice flour, thinking it would be safer.

During the month of muffins with rice flour, the failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14) (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.579).

Adjusting for age, gender, and atopic dermatitis, children were more than five times more likely to fail baked eggs without wheat (odds ratio, 5.4; P = .002), and more than four times more likely to fail baked milk (OR, 4.06; P = .05).

Given that the phenomenon hasn’t been reported before, “This was very surprising to us,” said study investigator Dr. Bruce Lanser, director of the pediatric food allergy program at National Jewish. “You have to warn parents that if children pass a baked challenge with wheat, they have to continue to eat their baked milk and egg with wheat. Gluten-free products are not going to have the same effect.

“If somebody is avoiding wheat because it causes a bit of redness and itchiness, you have to clear that wheat allergy” before moving to baked egg and milk, Dr. Lanser added.

There’s also concern that “kids will go home after passing a wheat muffin challenge, eat something that’s gluten-free, and have a reaction,” he noted. Wheat-free baked goods might also not build tolerance as well, although that’s not clear from the study, Dr. Lanser said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Wheat seems to have something unique that alters the allergic properties of egg and milk proteins to help children outgrow their sensitivities. “Rice doesn’t have the same effect,” he observed, and it’s not known if any other grains do. Dr. Lanser said he is interested in looking into rye, barley, oats, and other alternatives.

The mean age of the children in the study was 6 years, and most children had multiple food allergies. Sensitization was confirmed by skin tests and specific IgE.

Meanwhile, there’s a new rule in the National Jewish kitchen: Unless a child has true celiac disease, “always make [challenge] muffins with wheat,” Dr. Lanser said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Children are more likely to react to nonwheat challenge muffins, and wheat substitutes might not work as well for oral immunotherapy.

Major finding: The failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14).

Data source: Single-center review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

Postvaccination anaphylaxis still possible with certain vaccines

New findings confirm that although it is rare, postvaccination anaphylaxis can still occur with certain vaccines.

Dr. Michael M. McNeil of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and his associates identified 17,606,500 vaccination visits from Jan. 1, 2009, through Dec. 31, 2011, at which 25,173,965 vaccine doses were administered. The researchers identified 76 cases of chart-confirmed anaphylaxis; 33 anaphylaxis cases were associated with vaccination, and 43 were attributed to other causes.

Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) was the major contributor to vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases in the population, although the rate (1.35 cases per 1 million vaccine doses of TIV given alone) was similar to the rate for all vaccines. The postvaccination anaphylaxis case rate not involving TIV was 1.32 per million vaccine doses.

The study factored in race, age, gender, symptoms, and history of the patients. There were no deaths, and only 1 patient (3%) was hospitalized. A total of 28 of the 33 vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases involved patients with a history of atopy.

“Although anaphylaxis after immunization is rare, its immediate onset (usually within minutes) and life-threatening nature require that all personnel and facilities providing vaccinations have procedures in place for anaphylaxis management,” the investigators noted. “Additional provider education concerning current recommendations for treatment and follow-up appears to be warranted.”

Find the full story in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Mar;137[3]:868-78).

New findings confirm that although it is rare, postvaccination anaphylaxis can still occur with certain vaccines.

Dr. Michael M. McNeil of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and his associates identified 17,606,500 vaccination visits from Jan. 1, 2009, through Dec. 31, 2011, at which 25,173,965 vaccine doses were administered. The researchers identified 76 cases of chart-confirmed anaphylaxis; 33 anaphylaxis cases were associated with vaccination, and 43 were attributed to other causes.

Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) was the major contributor to vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases in the population, although the rate (1.35 cases per 1 million vaccine doses of TIV given alone) was similar to the rate for all vaccines. The postvaccination anaphylaxis case rate not involving TIV was 1.32 per million vaccine doses.

The study factored in race, age, gender, symptoms, and history of the patients. There were no deaths, and only 1 patient (3%) was hospitalized. A total of 28 of the 33 vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases involved patients with a history of atopy.

“Although anaphylaxis after immunization is rare, its immediate onset (usually within minutes) and life-threatening nature require that all personnel and facilities providing vaccinations have procedures in place for anaphylaxis management,” the investigators noted. “Additional provider education concerning current recommendations for treatment and follow-up appears to be warranted.”

Find the full story in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Mar;137[3]:868-78).

New findings confirm that although it is rare, postvaccination anaphylaxis can still occur with certain vaccines.

Dr. Michael M. McNeil of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and his associates identified 17,606,500 vaccination visits from Jan. 1, 2009, through Dec. 31, 2011, at which 25,173,965 vaccine doses were administered. The researchers identified 76 cases of chart-confirmed anaphylaxis; 33 anaphylaxis cases were associated with vaccination, and 43 were attributed to other causes.

Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) was the major contributor to vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases in the population, although the rate (1.35 cases per 1 million vaccine doses of TIV given alone) was similar to the rate for all vaccines. The postvaccination anaphylaxis case rate not involving TIV was 1.32 per million vaccine doses.

The study factored in race, age, gender, symptoms, and history of the patients. There were no deaths, and only 1 patient (3%) was hospitalized. A total of 28 of the 33 vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases involved patients with a history of atopy.

“Although anaphylaxis after immunization is rare, its immediate onset (usually within minutes) and life-threatening nature require that all personnel and facilities providing vaccinations have procedures in place for anaphylaxis management,” the investigators noted. “Additional provider education concerning current recommendations for treatment and follow-up appears to be warranted.”

Find the full story in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Mar;137[3]:868-78).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Obeticholic acid gains recommendation for accelerated approval in primary biliary cholangitis

SILVER SPRING, MD. – A Food and Drug Administration advisory panel unanimously voted in favor of accelerated approval for a novel drug to treat primary biliary cholangitis on April 7, 2016. The accelerated drug approval process allows for the use of alkaline phosphatase levels as a surrogate endpoint of efficacy.*

At the meeting of the FDA Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee, panelists wrestled with additional questions from the FDA regarding the use of obeticholic acid (OCA) for primary biliary cholangitis. Presented as discussion items, these included how to select appropriate populations for the novel drug, the proper dosing schema, and how to go forward in postmarketing confirmatory trials of OCA.

The exact indication for which the applicant, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, is seeking obeticholic acid approval is “treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, or as monotherapy in patients unable to tolerate UDCA.”

In discussion after the unanimous vote for accelerated approval, Dr. Maria Sjogren, a hepatologist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md. said, “I welcome this drug in the clinic. It will be a great addition for many patients.” Dr. Marina Silveira, of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, agreed: “There is an unmet need, and there are no significant safety or tolerability concerns. But I do think there is more study that’s going to be needed.”

The pivotal phase III clinical trial, POISE [PBC OCA International Study of Efficacy], showed that at the final 1-year assessment, 46% of patients treated with an initial 5 mg daily dose of OCA, and 47% of those treated with 10 mg daily, achieved the primary efficacy endpoint of an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level less than 1.67 times the upper limit of normal, and/or had bilirubin levels less than the upper limit of normal and a 15% or greater reduction in ALP.

The drug was generally well tolerated at the doses used in the POISE trial. Pruritus was common but well-managed in both OCA treatment arms. No concerning hepatic safety signals were seen in the 5-mg titration arm or the 10-mg arm.

PBC (formerly known as primary biliary cirrhosis) is a progressive autoimmune disease of unknown etiology that causes cholestasis, resulting in destruction of the biliary system over time.

Currently, the only approved treatment for PBC is UDCA. Obeticholic acid (to be marketed as Ocaliva by Intercept Pharmaceuticals) is an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a nuclear receptor that controls bile acid homeostasis. The direct FXR agonist activity differs from the mechanism of action of UDCA, which has no nuclear receptor action. Dosing for OCA can thus be much lower, making it attractive for PBC patients who face a considerable pill burden with weight-based dosing of UDCA.

Though committee members acknowledged unmet needs for more and better therapies for PBC patients who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate UDCA, they repeatedly asked for high-quality longitudinal data collection and analysis. Clinical trial data show a signal for early low-density lipoprotein elevation with OCA, as well as long-term lowering of high-density lipoprotein levels.

Regarding the proposed dosing of OCA, FDA analysts agreed with the applicant that a starting dose of 5 mg daily is appropriate, since a dose-dependent increase in pruritus-related discontinuations was seen in phase III clinical trials. Also, a better tolerability profile is seen over time with a lower starting dose, with fewer discontinuations, fewer days of severe pruritus, and delayed time to the first episode of pruritus with the 5-mg starting dose.

Additionally, efficacy was preserved with dose titration, with similar efficacy seen at 1 year for the titration arm, compared with the 10-mg fixed-dose arm in the POISE trial that compared titration from 5 to 10 mg and fixed 10-mg dosing with placebo.

However, the FDA took issue with Intercept’s proposal not to adjust dosing in moderate or severe hepatic impairment, instead proposing a starting dose of 5 mg once weekly, and titrating up to 5 mg twice weekly and finally to a maximum of 10 mg twice weekly, depending on response and tolerability. The FDA’s rationale for this was the lack of clear benefit of high exposures to OCA in moderate or severe hepatic impairment. Another factor was the increased incidence of hepatic adverse events and the higher rate of discontinuation at higher exposures that were seen in earlier clinical trials that used higher doses of OCA.

Panelists, in their critique of the FDA’s proposed hepatic impairment dose adjustments, felt there was insufficient data to support this adjusted regimen and called for more study.

An especially thorny issue for panelists and the FDA was the design of the phase IV trial, which is a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center international trial comparing OCA with placebo for PBC. This trial has already begun to enroll patients and will continue to recruit for a total of 2 years; follow-up will continue for 6 years with quarterly visits. Historical control data from a global PBC database are also available for analysis.

Panelist Dr. Timothy Lipman, emeritus chief of the GI-hepatology-nutrition center at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, said, “As a clinician who is very interested in clinical study methodology, I am concerned about possible bias. And the use of historical control data is a nonstarter,” since the study quality would suffer. “Changes in protocol as a study goes on are always problematic,” so the FDA’s request for feedback on how to tinker with study design was a concern.

But the biggest concern voiced by Dr. Lipman and others on the committee, including FDA representatives, was the huge barrier to enrollment that’s presented by a placebo-controlled study for a drug that has already been approved. “This is always a major issue for the FDA in approving drugs under accelerated approval,” acknowledged Dr. Amy Egan, deputy director of the FDA’s office of drug evaluation III, office of new drugs. The anticipation of difficulty in enrolling is one reason the historical control arm is held in reserve, she said. Intercept’s vice president for clinical development Dr. Leigh MacConell concurred, saying of the discussions with the FDA about study design, “It was a very difficult conversation, because we agree with your assessment regarding the feasibility” of the study.

The FDA noted remaining issues requiring ongoing study of OCA for PBC. Among these is the need to confirm the clinical benefit of OCA across the full spectrum of severity of PBC, from early stage to advanced disease. “FDA would also like to evaluate additional data on use of OCA as monotherapy,” said Dr. Lara Dimick-Santos, cross-discipline team leader at the FDA.

The course of PBC is variable; it affects women approximately 10 times more frequently than men. Occurring in approximately 1 in 1,000 women over the age of 40, its prevalence is thought to be increasing. PBC is usually asymptomatic for some time; when symptoms occur, fatigue and pruritis are the most common. Concomitant autoimmune diseases are common and an earlier age at diagnosis is often associated with a worse disease course. A significant number of those affected by PBC will progress to death or liver transplantation.

Intercept Pharmaceuticals is also studying OCA for use in other liver conditions, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

All committee members submitted information to the FDA regarding conflicts of interest. The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels.

*Changes were made to this story on April 8, 2016.

On Twitter @karioakes

SILVER SPRING, MD. – A Food and Drug Administration advisory panel unanimously voted in favor of accelerated approval for a novel drug to treat primary biliary cholangitis on April 7, 2016. The accelerated drug approval process allows for the use of alkaline phosphatase levels as a surrogate endpoint of efficacy.*

At the meeting of the FDA Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee, panelists wrestled with additional questions from the FDA regarding the use of obeticholic acid (OCA) for primary biliary cholangitis. Presented as discussion items, these included how to select appropriate populations for the novel drug, the proper dosing schema, and how to go forward in postmarketing confirmatory trials of OCA.

The exact indication for which the applicant, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, is seeking obeticholic acid approval is “treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, or as monotherapy in patients unable to tolerate UDCA.”

In discussion after the unanimous vote for accelerated approval, Dr. Maria Sjogren, a hepatologist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md. said, “I welcome this drug in the clinic. It will be a great addition for many patients.” Dr. Marina Silveira, of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, agreed: “There is an unmet need, and there are no significant safety or tolerability concerns. But I do think there is more study that’s going to be needed.”

The pivotal phase III clinical trial, POISE [PBC OCA International Study of Efficacy], showed that at the final 1-year assessment, 46% of patients treated with an initial 5 mg daily dose of OCA, and 47% of those treated with 10 mg daily, achieved the primary efficacy endpoint of an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level less than 1.67 times the upper limit of normal, and/or had bilirubin levels less than the upper limit of normal and a 15% or greater reduction in ALP.

The drug was generally well tolerated at the doses used in the POISE trial. Pruritus was common but well-managed in both OCA treatment arms. No concerning hepatic safety signals were seen in the 5-mg titration arm or the 10-mg arm.

PBC (formerly known as primary biliary cirrhosis) is a progressive autoimmune disease of unknown etiology that causes cholestasis, resulting in destruction of the biliary system over time.

Currently, the only approved treatment for PBC is UDCA. Obeticholic acid (to be marketed as Ocaliva by Intercept Pharmaceuticals) is an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a nuclear receptor that controls bile acid homeostasis. The direct FXR agonist activity differs from the mechanism of action of UDCA, which has no nuclear receptor action. Dosing for OCA can thus be much lower, making it attractive for PBC patients who face a considerable pill burden with weight-based dosing of UDCA.

Though committee members acknowledged unmet needs for more and better therapies for PBC patients who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate UDCA, they repeatedly asked for high-quality longitudinal data collection and analysis. Clinical trial data show a signal for early low-density lipoprotein elevation with OCA, as well as long-term lowering of high-density lipoprotein levels.

Regarding the proposed dosing of OCA, FDA analysts agreed with the applicant that a starting dose of 5 mg daily is appropriate, since a dose-dependent increase in pruritus-related discontinuations was seen in phase III clinical trials. Also, a better tolerability profile is seen over time with a lower starting dose, with fewer discontinuations, fewer days of severe pruritus, and delayed time to the first episode of pruritus with the 5-mg starting dose.

Additionally, efficacy was preserved with dose titration, with similar efficacy seen at 1 year for the titration arm, compared with the 10-mg fixed-dose arm in the POISE trial that compared titration from 5 to 10 mg and fixed 10-mg dosing with placebo.

However, the FDA took issue with Intercept’s proposal not to adjust dosing in moderate or severe hepatic impairment, instead proposing a starting dose of 5 mg once weekly, and titrating up to 5 mg twice weekly and finally to a maximum of 10 mg twice weekly, depending on response and tolerability. The FDA’s rationale for this was the lack of clear benefit of high exposures to OCA in moderate or severe hepatic impairment. Another factor was the increased incidence of hepatic adverse events and the higher rate of discontinuation at higher exposures that were seen in earlier clinical trials that used higher doses of OCA.

Panelists, in their critique of the FDA’s proposed hepatic impairment dose adjustments, felt there was insufficient data to support this adjusted regimen and called for more study.

An especially thorny issue for panelists and the FDA was the design of the phase IV trial, which is a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center international trial comparing OCA with placebo for PBC. This trial has already begun to enroll patients and will continue to recruit for a total of 2 years; follow-up will continue for 6 years with quarterly visits. Historical control data from a global PBC database are also available for analysis.

Panelist Dr. Timothy Lipman, emeritus chief of the GI-hepatology-nutrition center at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, said, “As a clinician who is very interested in clinical study methodology, I am concerned about possible bias. And the use of historical control data is a nonstarter,” since the study quality would suffer. “Changes in protocol as a study goes on are always problematic,” so the FDA’s request for feedback on how to tinker with study design was a concern.

But the biggest concern voiced by Dr. Lipman and others on the committee, including FDA representatives, was the huge barrier to enrollment that’s presented by a placebo-controlled study for a drug that has already been approved. “This is always a major issue for the FDA in approving drugs under accelerated approval,” acknowledged Dr. Amy Egan, deputy director of the FDA’s office of drug evaluation III, office of new drugs. The anticipation of difficulty in enrolling is one reason the historical control arm is held in reserve, she said. Intercept’s vice president for clinical development Dr. Leigh MacConell concurred, saying of the discussions with the FDA about study design, “It was a very difficult conversation, because we agree with your assessment regarding the feasibility” of the study.

The FDA noted remaining issues requiring ongoing study of OCA for PBC. Among these is the need to confirm the clinical benefit of OCA across the full spectrum of severity of PBC, from early stage to advanced disease. “FDA would also like to evaluate additional data on use of OCA as monotherapy,” said Dr. Lara Dimick-Santos, cross-discipline team leader at the FDA.

The course of PBC is variable; it affects women approximately 10 times more frequently than men. Occurring in approximately 1 in 1,000 women over the age of 40, its prevalence is thought to be increasing. PBC is usually asymptomatic for some time; when symptoms occur, fatigue and pruritis are the most common. Concomitant autoimmune diseases are common and an earlier age at diagnosis is often associated with a worse disease course. A significant number of those affected by PBC will progress to death or liver transplantation.

Intercept Pharmaceuticals is also studying OCA for use in other liver conditions, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

All committee members submitted information to the FDA regarding conflicts of interest. The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels.

*Changes were made to this story on April 8, 2016.

On Twitter @karioakes

SILVER SPRING, MD. – A Food and Drug Administration advisory panel unanimously voted in favor of accelerated approval for a novel drug to treat primary biliary cholangitis on April 7, 2016. The accelerated drug approval process allows for the use of alkaline phosphatase levels as a surrogate endpoint of efficacy.*

At the meeting of the FDA Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee, panelists wrestled with additional questions from the FDA regarding the use of obeticholic acid (OCA) for primary biliary cholangitis. Presented as discussion items, these included how to select appropriate populations for the novel drug, the proper dosing schema, and how to go forward in postmarketing confirmatory trials of OCA.

The exact indication for which the applicant, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, is seeking obeticholic acid approval is “treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, or as monotherapy in patients unable to tolerate UDCA.”

In discussion after the unanimous vote for accelerated approval, Dr. Maria Sjogren, a hepatologist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md. said, “I welcome this drug in the clinic. It will be a great addition for many patients.” Dr. Marina Silveira, of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, agreed: “There is an unmet need, and there are no significant safety or tolerability concerns. But I do think there is more study that’s going to be needed.”

The pivotal phase III clinical trial, POISE [PBC OCA International Study of Efficacy], showed that at the final 1-year assessment, 46% of patients treated with an initial 5 mg daily dose of OCA, and 47% of those treated with 10 mg daily, achieved the primary efficacy endpoint of an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level less than 1.67 times the upper limit of normal, and/or had bilirubin levels less than the upper limit of normal and a 15% or greater reduction in ALP.

The drug was generally well tolerated at the doses used in the POISE trial. Pruritus was common but well-managed in both OCA treatment arms. No concerning hepatic safety signals were seen in the 5-mg titration arm or the 10-mg arm.

PBC (formerly known as primary biliary cirrhosis) is a progressive autoimmune disease of unknown etiology that causes cholestasis, resulting in destruction of the biliary system over time.

Currently, the only approved treatment for PBC is UDCA. Obeticholic acid (to be marketed as Ocaliva by Intercept Pharmaceuticals) is an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a nuclear receptor that controls bile acid homeostasis. The direct FXR agonist activity differs from the mechanism of action of UDCA, which has no nuclear receptor action. Dosing for OCA can thus be much lower, making it attractive for PBC patients who face a considerable pill burden with weight-based dosing of UDCA.

Though committee members acknowledged unmet needs for more and better therapies for PBC patients who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate UDCA, they repeatedly asked for high-quality longitudinal data collection and analysis. Clinical trial data show a signal for early low-density lipoprotein elevation with OCA, as well as long-term lowering of high-density lipoprotein levels.

Regarding the proposed dosing of OCA, FDA analysts agreed with the applicant that a starting dose of 5 mg daily is appropriate, since a dose-dependent increase in pruritus-related discontinuations was seen in phase III clinical trials. Also, a better tolerability profile is seen over time with a lower starting dose, with fewer discontinuations, fewer days of severe pruritus, and delayed time to the first episode of pruritus with the 5-mg starting dose.

Additionally, efficacy was preserved with dose titration, with similar efficacy seen at 1 year for the titration arm, compared with the 10-mg fixed-dose arm in the POISE trial that compared titration from 5 to 10 mg and fixed 10-mg dosing with placebo.

However, the FDA took issue with Intercept’s proposal not to adjust dosing in moderate or severe hepatic impairment, instead proposing a starting dose of 5 mg once weekly, and titrating up to 5 mg twice weekly and finally to a maximum of 10 mg twice weekly, depending on response and tolerability. The FDA’s rationale for this was the lack of clear benefit of high exposures to OCA in moderate or severe hepatic impairment. Another factor was the increased incidence of hepatic adverse events and the higher rate of discontinuation at higher exposures that were seen in earlier clinical trials that used higher doses of OCA.

Panelists, in their critique of the FDA’s proposed hepatic impairment dose adjustments, felt there was insufficient data to support this adjusted regimen and called for more study.

An especially thorny issue for panelists and the FDA was the design of the phase IV trial, which is a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center international trial comparing OCA with placebo for PBC. This trial has already begun to enroll patients and will continue to recruit for a total of 2 years; follow-up will continue for 6 years with quarterly visits. Historical control data from a global PBC database are also available for analysis.

Panelist Dr. Timothy Lipman, emeritus chief of the GI-hepatology-nutrition center at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, said, “As a clinician who is very interested in clinical study methodology, I am concerned about possible bias. And the use of historical control data is a nonstarter,” since the study quality would suffer. “Changes in protocol as a study goes on are always problematic,” so the FDA’s request for feedback on how to tinker with study design was a concern.

But the biggest concern voiced by Dr. Lipman and others on the committee, including FDA representatives, was the huge barrier to enrollment that’s presented by a placebo-controlled study for a drug that has already been approved. “This is always a major issue for the FDA in approving drugs under accelerated approval,” acknowledged Dr. Amy Egan, deputy director of the FDA’s office of drug evaluation III, office of new drugs. The anticipation of difficulty in enrolling is one reason the historical control arm is held in reserve, she said. Intercept’s vice president for clinical development Dr. Leigh MacConell concurred, saying of the discussions with the FDA about study design, “It was a very difficult conversation, because we agree with your assessment regarding the feasibility” of the study.

The FDA noted remaining issues requiring ongoing study of OCA for PBC. Among these is the need to confirm the clinical benefit of OCA across the full spectrum of severity of PBC, from early stage to advanced disease. “FDA would also like to evaluate additional data on use of OCA as monotherapy,” said Dr. Lara Dimick-Santos, cross-discipline team leader at the FDA.

The course of PBC is variable; it affects women approximately 10 times more frequently than men. Occurring in approximately 1 in 1,000 women over the age of 40, its prevalence is thought to be increasing. PBC is usually asymptomatic for some time; when symptoms occur, fatigue and pruritis are the most common. Concomitant autoimmune diseases are common and an earlier age at diagnosis is often associated with a worse disease course. A significant number of those affected by PBC will progress to death or liver transplantation.

Intercept Pharmaceuticals is also studying OCA for use in other liver conditions, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

All committee members submitted information to the FDA regarding conflicts of interest. The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels.

*Changes were made to this story on April 8, 2016.

On Twitter @karioakes

Recently identified eczema comorbidities include anemia, obesity

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The list of nonatopic comorbid conditions associated with atopic dermatitis is rapidly expanding.

Just in the past year, published studies have linked pediatric atopic dermatitis to increased risks of obesity, high blood pressure, headaches, anemia, and speech disorders. Meanwhile, adult atopic dermatitis was reported to be associated with increased rates of fracture and cardiovascular disease. And in the dermatologic arena, a link between atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata was identified, Dr. Lawrence F. Eichenfield noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Actually, these reported associations published in 2015-2016 might best be termed “emerging comorbidities,” as they are first reports and thus need confirmation, said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego.

Much of this work on emerging comorbidities has been done by dermatologist Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg of Northwestern University, Chicago, and various coinvestigators. They have been prolific.

For example, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis of 207,007 children and adolescents included in the cross-sectional 1997-2013 U.S. National Health Interview Survey, Dr. Silverberg and coinvestigators found that eczema was independently associated with a 1.83-fold increased odds of anemia. They bolstered this observation with an analysis of more than 30,000 children and adolescents in the 1992-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in which they found that current eczema was associated with a 1.93-fold increased odds of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia. The underlying mechanism is unknown; however, the investigators noted that chronic inflammation and systemic immunosuppressant drugs have been shown to be associated with anemia (JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170[1]:29-34).

Dr. Silverberg also found in a multivariate logistic regression analysis of data on more than 400,000 pediatric participants in the National Survey of Children’s Health and the National Health Interview Survey that mild and severe eczema were independently associated with 1.79-fold and 2.72-fold, respectively, increased odds of headaches (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb;137[2]:492-9).

Using these same two data sources, with multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the investigators found that eczema was associated with a 1.81-fold increased risk of speech disorder (J Pediatr. 2016 Jan;168:185-92).

In a case-control study involving 132 children and adolescents with current moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and 143 healthy controls, Dr. Silverberg and coinvestigators found in a logistic regression analysis that atopic dermatitis was independently associated with a doubled risk of having a systolic blood pressure in the 90th percentile or higher – as well as 3.92-fold increased odds of central obesity, as defined by a waist circumference in the 85th percentile or higher (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Feb;151[2]:144-52).

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 published vitiligo studies and 17 published studies of alopecia areata, Dr. Silverberg and medical student Girish C. Mohan found that patients with vitiligo or alopecia areata were respectively 7.8 and 2.6 times more likely to have atopic dermatitis than controls without those disorders (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 May;151[5]:522-8).

In a logistic regression analysis of data on 34,500 adults with a history of eczema within the prior year who participated in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, Drs. Nitin Garg and Dr. Silverberg concluded that the results suggested that adult atopic dermatitis is a previously unrecognized risk factor for fracture and other bone or joint injuries causing limitation. Adults with atopic dermatitis were at a 1.67-fold increased risk for such injuries in an analysis controlling for sociodemographics, other forms of atopic disease, and psychiatric and behavioral disorders (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Jan;151[1]:33-41).

In another large cross-sectional study, Dr. Silverberg found that adults with atopic dermatitis had significantly higher odds of a history of acute MI, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke (Allergy. 2015 Oct;70[10]:1300-8).

Dr. Eichenfield said that while he would like to see these hot-off-the-presses 2015-2016 findings on nonatopic comorbidities backed up by confirmatory studies in other populations, the evidence is stronger for an association between pediatric atopic dermatitis and several mental health disorders. The initial reports came mainly from Europe, but were then supported by a large study by Dr. Eric L. Simpson and coinvestigators at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

In their analysis of data on nearly 93,000 noninstitutionalized children and adolescents included in the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health, the investigators found after controlling for potential confounders that atopic dermatitis was associated with a 1.87-fold increased risk of having attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, a 3-fold increased risk of diagnosed autism, an adjusted 1.81-fold increase in depression, and 1.87-fold increased odds of conduct disorder. The Oregon group found a clear dose-dependent relationship between the reported severity of the skin disease and the likelihood of those mental health disorders (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Feb;131[2]:428-33).

The hope is that emerging strategies to prevent atopic dermatitis or aggressively treat it early on will reduce the risk of many of these comorbid conditions, Dr. Eichenfield said.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The list of nonatopic comorbid conditions associated with atopic dermatitis is rapidly expanding.

Just in the past year, published studies have linked pediatric atopic dermatitis to increased risks of obesity, high blood pressure, headaches, anemia, and speech disorders. Meanwhile, adult atopic dermatitis was reported to be associated with increased rates of fracture and cardiovascular disease. And in the dermatologic arena, a link between atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata was identified, Dr. Lawrence F. Eichenfield noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Actually, these reported associations published in 2015-2016 might best be termed “emerging comorbidities,” as they are first reports and thus need confirmation, said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego.

Much of this work on emerging comorbidities has been done by dermatologist Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg of Northwestern University, Chicago, and various coinvestigators. They have been prolific.

For example, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis of 207,007 children and adolescents included in the cross-sectional 1997-2013 U.S. National Health Interview Survey, Dr. Silverberg and coinvestigators found that eczema was independently associated with a 1.83-fold increased odds of anemia. They bolstered this observation with an analysis of more than 30,000 children and adolescents in the 1992-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in which they found that current eczema was associated with a 1.93-fold increased odds of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia. The underlying mechanism is unknown; however, the investigators noted that chronic inflammation and systemic immunosuppressant drugs have been shown to be associated with anemia (JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170[1]:29-34).

Dr. Silverberg also found in a multivariate logistic regression analysis of data on more than 400,000 pediatric participants in the National Survey of Children’s Health and the National Health Interview Survey that mild and severe eczema were independently associated with 1.79-fold and 2.72-fold, respectively, increased odds of headaches (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb;137[2]:492-9).

Using these same two data sources, with multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the investigators found that eczema was associated with a 1.81-fold increased risk of speech disorder (J Pediatr. 2016 Jan;168:185-92).

In a case-control study involving 132 children and adolescents with current moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and 143 healthy controls, Dr. Silverberg and coinvestigators found in a logistic regression analysis that atopic dermatitis was independently associated with a doubled risk of having a systolic blood pressure in the 90th percentile or higher – as well as 3.92-fold increased odds of central obesity, as defined by a waist circumference in the 85th percentile or higher (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Feb;151[2]:144-52).

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 published vitiligo studies and 17 published studies of alopecia areata, Dr. Silverberg and medical student Girish C. Mohan found that patients with vitiligo or alopecia areata were respectively 7.8 and 2.6 times more likely to have atopic dermatitis than controls without those disorders (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 May;151[5]:522-8).

In a logistic regression analysis of data on 34,500 adults with a history of eczema within the prior year who participated in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, Drs. Nitin Garg and Dr. Silverberg concluded that the results suggested that adult atopic dermatitis is a previously unrecognized risk factor for fracture and other bone or joint injuries causing limitation. Adults with atopic dermatitis were at a 1.67-fold increased risk for such injuries in an analysis controlling for sociodemographics, other forms of atopic disease, and psychiatric and behavioral disorders (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Jan;151[1]:33-41).

In another large cross-sectional study, Dr. Silverberg found that adults with atopic dermatitis had significantly higher odds of a history of acute MI, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke (Allergy. 2015 Oct;70[10]:1300-8).

Dr. Eichenfield said that while he would like to see these hot-off-the-presses 2015-2016 findings on nonatopic comorbidities backed up by confirmatory studies in other populations, the evidence is stronger for an association between pediatric atopic dermatitis and several mental health disorders. The initial reports came mainly from Europe, but were then supported by a large study by Dr. Eric L. Simpson and coinvestigators at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

In their analysis of data on nearly 93,000 noninstitutionalized children and adolescents included in the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health, the investigators found after controlling for potential confounders that atopic dermatitis was associated with a 1.87-fold increased risk of having attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, a 3-fold increased risk of diagnosed autism, an adjusted 1.81-fold increase in depression, and 1.87-fold increased odds of conduct disorder. The Oregon group found a clear dose-dependent relationship between the reported severity of the skin disease and the likelihood of those mental health disorders (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Feb;131[2]:428-33).

The hope is that emerging strategies to prevent atopic dermatitis or aggressively treat it early on will reduce the risk of many of these comorbid conditions, Dr. Eichenfield said.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The list of nonatopic comorbid conditions associated with atopic dermatitis is rapidly expanding.

Just in the past year, published studies have linked pediatric atopic dermatitis to increased risks of obesity, high blood pressure, headaches, anemia, and speech disorders. Meanwhile, adult atopic dermatitis was reported to be associated with increased rates of fracture and cardiovascular disease. And in the dermatologic arena, a link between atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata was identified, Dr. Lawrence F. Eichenfield noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Actually, these reported associations published in 2015-2016 might best be termed “emerging comorbidities,” as they are first reports and thus need confirmation, said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego.

Much of this work on emerging comorbidities has been done by dermatologist Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg of Northwestern University, Chicago, and various coinvestigators. They have been prolific.

For example, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis of 207,007 children and adolescents included in the cross-sectional 1997-2013 U.S. National Health Interview Survey, Dr. Silverberg and coinvestigators found that eczema was independently associated with a 1.83-fold increased odds of anemia. They bolstered this observation with an analysis of more than 30,000 children and adolescents in the 1992-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in which they found that current eczema was associated with a 1.93-fold increased odds of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia. The underlying mechanism is unknown; however, the investigators noted that chronic inflammation and systemic immunosuppressant drugs have been shown to be associated with anemia (JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170[1]:29-34).

Dr. Silverberg also found in a multivariate logistic regression analysis of data on more than 400,000 pediatric participants in the National Survey of Children’s Health and the National Health Interview Survey that mild and severe eczema were independently associated with 1.79-fold and 2.72-fold, respectively, increased odds of headaches (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb;137[2]:492-9).

Using these same two data sources, with multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the investigators found that eczema was associated with a 1.81-fold increased risk of speech disorder (J Pediatr. 2016 Jan;168:185-92).

In a case-control study involving 132 children and adolescents with current moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and 143 healthy controls, Dr. Silverberg and coinvestigators found in a logistic regression analysis that atopic dermatitis was independently associated with a doubled risk of having a systolic blood pressure in the 90th percentile or higher – as well as 3.92-fold increased odds of central obesity, as defined by a waist circumference in the 85th percentile or higher (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Feb;151[2]:144-52).

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 published vitiligo studies and 17 published studies of alopecia areata, Dr. Silverberg and medical student Girish C. Mohan found that patients with vitiligo or alopecia areata were respectively 7.8 and 2.6 times more likely to have atopic dermatitis than controls without those disorders (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 May;151[5]:522-8).

In a logistic regression analysis of data on 34,500 adults with a history of eczema within the prior year who participated in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, Drs. Nitin Garg and Dr. Silverberg concluded that the results suggested that adult atopic dermatitis is a previously unrecognized risk factor for fracture and other bone or joint injuries causing limitation. Adults with atopic dermatitis were at a 1.67-fold increased risk for such injuries in an analysis controlling for sociodemographics, other forms of atopic disease, and psychiatric and behavioral disorders (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Jan;151[1]:33-41).

In another large cross-sectional study, Dr. Silverberg found that adults with atopic dermatitis had significantly higher odds of a history of acute MI, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke (Allergy. 2015 Oct;70[10]:1300-8).

Dr. Eichenfield said that while he would like to see these hot-off-the-presses 2015-2016 findings on nonatopic comorbidities backed up by confirmatory studies in other populations, the evidence is stronger for an association between pediatric atopic dermatitis and several mental health disorders. The initial reports came mainly from Europe, but were then supported by a large study by Dr. Eric L. Simpson and coinvestigators at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.